نيكولاس مادورو

- هذا اسم إسباني; لا يتضمن اسم العائلة.

نيكولاس مادورو | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

مادورو عام 2023. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| رئيس ڤنزويلا | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| في المنصب 5 مارس 2013 – 3 يناير 2026 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| نائب الرئيس | انظر القائمة

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| سبقه | هوگو تشاڤيز | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| خلـَفه | محتجز لدى الحكومة الأمريكية حالياً | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| رئيس الحزب الاشتراكي المتحد | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| تولى المنصب 5 مارس 2013 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| نائب الرئيس | ديوسدادو كابيلو | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| سبقه | هوگو تشاڤيز | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| نائب رئيس ڤنزويلا | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| في المنصب 13 أكتوبر 2012 – 19 أبريل 2013 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| الرئيس |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| سبقه | إلياس خاوا | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| خلـَفه | خورخى أريازا | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| تفاصيل شخصية | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| وُلِد | نيكولاس مادورو موروس 23 نوفمبر 1962 كراكاس، [أ] ڤنزويلا | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| الحزب | الحزب الاشتراكي المتحد (منذ 2007) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ارتباطات سياسية أخرى | حركة الجمهورية الخامسة (حتى 2007) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| الزوج |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| الأنجال | نيكولاس مادورو گويرا | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| الإقامة | قصر ميرافلورس | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| الوظيفة |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| التوقيع |  | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

نيكولاس مادورو موروس ([ب]، إنگليزية: Nicolás Maduro Moros، و. 23 نوفمبر 1962)، هو سياسي وزعيم نقابي ڤنزويلي سابق، ورئيس ڤنزويلا منذ 2023 حتى اعتقاله والإطاحة به عام 2026.[1][2][3][4] كان مادورو نائباً للرئيس هوگو تشاڤيز عام 2012 حتى 2013، ووزيراً للخارجية من عام 2006 حتى 2012.

بدأ مادورو مسيرته كسائق حافلة، ثم ارتقى ليصبح زعيماً نقابياً قبل انتخابه لعضوية الجمعية الوطنية الڤنزويلية عام 2000. وبصفته عضواً في الحزب الاشتراكي المتحد، فقد عُيّن في عدد من المناصب في عهد تشاڤيز،[5] حيث شغل منصب رئيس الجمعية الوطنية، وزير الخارجية، ونائب الرئيس. تولى مادورو الرئاسة بعد وفاة تشاڤيز وفاز في الانتخابات الرئاسية 2013. يحكم مودورو ڤنزويلا بمرسوم منذ عام 2015 بموجب الصلاحيات الممنوحة له من قبل المجلس التشريعي للحزب الحاكم.[6][7]

أدى النقص في السلع وانخفاض مستويات المعيشة إلى اندلاع الاحتجاجات عام 2014 والتي تصاعدت إلى مسيرات يومية على مستوى البلاد وقمع المعارضة وتراجع شعبية مادورو.[8][9][10] عام 2015 انتُخب أعضاء الجمعية الوطنية بقيادة المعارضة، وبدأت حركة لعزل مادورو عام 2016، والتي ألغتها حكومة مادورو في نهاية المطاف؛ وحافظ مادورو على السلطة من خلال المحكمة العليا، والمجلس الانتخابي الوطني، والجيش.[8][9][11] جردت المحكمة العليا الجمعية الوطنية المنتخبة من صلاحياتها وسلطاتها، مما أدى إلى أزمة دستورية وموجة احتجاجات أخرى في نفس العام. واستجابةً لهذه الاحتجاجات، دعا مادورو إلى إعادة كتابة الدستور، وانتُخبت الجمعية الدستورية الڤنزويلية في ظل ظروف انتخابية اعتبرها الكثيرون غير نظامية.[12][13][14]

عام 2018، أُعيد انتخاب مادورو وأدى اليمين الدستورية وسط إدانة واسعة النطاق. وأعلنت المعارضة رئيس الجمعية الوطنية، خوان گوايدو، رئيساً مؤقتاً، مما أدى إلى اندلاع أزمة رئاسية والتي استمرت قرابة أربع سنوات وأثارت انقساماً في المجتمع الدولي.[15][16][17][18][19] عام 2024، ترشح مادورو لفترة رئاسية ثالثة في انتخابات، والتي زعمت اللجنة الوطنية للانتخابات الموالية لمادورو أنه فاز بها - دون تقديم أي دليل - مما أدى إلى اندلاع أزمة سياسية أخرى.[20] أظهرت نتائج فرز الأصوات التي جمعتها المعارضة أن مرشحهم، [[إدموندو گونزاليس، قد فاز بأكبر عدد من الأصوات.[21] عام 2025، صنفت الولايات المتحدة مادورو كعضو في منظمة إرهابية أجنبية.[22]

كان يُنظر إلى مادورو على نطاق واسع على أنه يقود حكومة سلطوية تتسم بالتزوير الانتخابي، وانتهاكات حقوق الإنسان، والفساد، والأزمات الاقتصادية الحادة. بين عامي 2013 و2023، تراجعت ڤنزويلا 42 مركزاً في مؤشر حرية الصحافة.[23] بحسب تقديرات الأمم المتحدة وهيومان رايتس واتش، فقد تعرض أكثر من 20.000 شخص للقتل خارج نطاق القضاء في عهد مادورو، وأُجبر سبعة مليون ڤنزويلي على الفرار من البلاد.[24][25][26]

خلصت بعثة الأمم المتحدة لتقصي الحقائق بشأن ڤنزويلا إلى أن استقلال النظام القضائي في البلاد قد تراجع؛ كما حددت البعثة انتهاكات متكررة للإجراءات القانونية الواجبة، بما في ذلك التدخل السياسي الخارجي، وزُعم الحصول على الأدلة عن طريق التعذيب.[27][28][29] تخضع معظم القنوات التلفزيونية الڤنزويلية لسيطرة الدولة، ولا يتم تغطية المعلومات غير المواتية للحكومة بشكل كامل.[30] عام 2018، زعم مجلس معين من قبل منظمة الدول الأمريكية أن جرائم ضد الإنسانية قد ارتكبت في ڤنزويلا خلال فترة رئاسة مادورو.[31] عام 2021، أعلن مكتب مدعي عام المحكمة الجنائية الدولية عن فتح تحقيق بشأن الوضع في البلاد.[32] ينفي مادورو جميع مزاعم سوء السلوك ويزعم أن الولايات المتحدة تآمرت ضد ڤنزويلا لتلفيق أزمة كوسيلة لتمكينها من تقديم حججها لتغيير النظام.[33][34]

النشأة والسنوات المبكرة

وُلد نيكولاس مادورو موروس في 23 نوفمبر 1962 في العاصمة الڤنزويلية كراكاس[أ]، لعائلة من الطبقة العاملة.[35][36][37][38] كان والده، نيكولاس مادورو گارسيا، زعيماً نقابياً بارزاً و"حالماً متشدداً الحركة الانتخابية الشعبية (MEP)"[39][40] وتوفي في حادث سيارة في 22 أبريل 1989. أما والدته، تريسا دي خيسوس موروس، فوُلدت في مدينة كوكوتا الكولومبية التي تقع على الحدود مع ڤنزويلا.[41] نشأ مادورو في الشارع رقم 14، وهو شارع في لوس خاردينيس، إل ڤالى، وهو حي للطبقة العاملة يقع على الأطراف الغربية لكراكاس.[41] كان الذكر الوحيد بين أربعة أشقاء، ولديه ثلاث شقيقات هن ماريا تريسا، وخوسفينا، وأنيتا.[39]

نشأ مادورو كاثوليكياً. وفي عام 2012، أفادت نيويورك تايمز أنه كان من أتباع المعلم الروحي الهندوسي ساتيا ساي بابا، وأنه زار المعلم الروحي في الهند عام 2005.[42] في مقابلة أجريت عام 2013، صرح مادورو بأن أجداده كانوا موريين (عرب من شمال أفريقيا) يهود، من أصول سفاردية، واعتنقوا الكاثوليكية في ڤنزويلا.[43]

تزوج مادورو مرتين. الأولى من أدريانا گويرا أنگولو، التي أنجب منها ابنه الوحيد، نيكولاس مادورو گويرا، المعروف أيضاً باسم "نيكولاسيتو"،[44][45] الذي عُين في العديد من المناصب الحكومية الرفيعة، منها رئيس هيئة المفتشين الخاصة التابعة لرئاسة الجمهورية، رئيس المدرسة الوطنية للسينما، وهو نائب في الجمعية الوطنية الڤنزويلية.[46]

في يوليو 2013، تزوج من سيليا فلورس، وهي محامية وسياسية خلفت مادورو كرئيسة للجمعية الوطنية الڤنزويلية في أغسطس 2006، عندما استقال ليصبح وزيراً للخارجية، لتصبح بذلك أول امرأة تشغل منصب رئيس الجمعية الوطنية.[47] كان الاثنان على علاقة عاطفية منذ التسعينيات عندما كانت فلورس محامية هوگو تشاڤيز في أعقاب محاولات انقلاب عام 1992[48] وتزوجا بعد أشهر من تولي مادورو الرئاسة.[49] على الرغم من عدم وجود أطفال مشتركين بينهما، إلا أن مادورو لديه ثلاثة أبناء بالتبني من زواج زوجته الأول من والتر رامون گاڤيديا؛ وهم والتر جاكوب، ويوسويل، ويوسر.[50]

مادورو معجب بموسيقى جون لينون ونشاطه السياسي من أجل السلام ومناهضة الحرب. وقد صرّح مادورو بأنه استلهم من موسيقى وثقافة الستينيات والسبعينيات المضادة، وذكر أيضاً روبرت پلانت وفرقة ليد زپلين.[51]

مسيرته المهنية المبكرة

التعليم والعمل النقابي

التحق مادورو بمدرسة ليسيو خوسيه أڤالوس الثانوية الحكومية في إل ڤالى.[36][52] كانت بدايته في عالم السياسة عندما أصبح عضواً في اتحاد طلبة مدرسته الثانوية.[35] بحسب سجلات المدرسة، لم يتخرج مادورو من المدرسة الثانوية.[38]

عمل مادورو سائق حافلة لعدة سنوات في شركة مترو كراكاس. أسس نقابة عمالية غير رسمية في الشركة، التي كانت تحظر النقابات آنذاك. كما عمل حارساً شخصياً لخوسيه ڤيسنتى رانگل أثناء حملته الرئاسية غير الناجحة 1983.[38][53]

في الرابعة والعشرين من عمره، كان مادورو يعيش في هاڤانا بعد أن أرسلته الرابطة الاشتراكية لحضور دورة لمدة عام واحد في "مدرسة خوليو أنطونيو ميلا الوطنية للكوادر"، وهو مركز تدريب سياسي يديره اتحاد الشباب الشيوعي.[41] بحسب كارلوس پنالوزا زامبرانو، خلال فترة وجود مادورو في كوبا، تلقى تعليمات من پدرو ميرت پرييتو، وهو عضو بارز في المكتب السياسي للحزب الشيوعي الكوبي وكان مقرباً من فيدل كاسترو.[54]

الحركة البوليڤارية الثورية-200

بحسب كارلوس پنالوزا زامبرانو، يُزعم أن حكومة كاسترو كلفت مادورو بالعمل "كخُلد" لدى مديرية المخابرات الكوبية للتقرب من هوگو تشاڤيز، الذي كان يعيش حياة عسكرية مزدهرة.[55]

في أوائل التسعينيات، انضم إلى الحركة البوليڤارية الثورية-200 وقاد حملةً للمطالبة بالإفراج عن تشاڤيز عندما سُجن لدوره في محاولات انقلاب 1992.[38] في أواخر التسعينيات، كان لمادورو دور محوري في تأسيس حركة الجمهورية الخامسة، التي دعمت تشاڤيز في ترشحه للرئاسة عام 1998.[52]

الجمعية الوطنية

انتُخب مادورو لعضوية مجلس النواب الڤنزويلي عن حزب حركة الجمهورية عام 1998، ثم لعضوية الجمعية التأسيسية الوطنية عام 199، وأخيراً لعضوية الجمعية الوطنية عام 2000، نائباً في جميع تلك الفترات عن مقاطعة العاصمة. وانتُخب رئيساً للجمعية الوطنية، وهو المنصب الذي شغله من عام 2005 حتى 2006.[بحاجة لمصدر]

وزير خارجية ڤنزويلا

عُيّن مادورو وزيراً للخارجية عام 2006، واستمر في منصبه في عهد تشاڤيز حتى عُيّن نائباً لرئيس ڤنزويلا في أكتوبر 2012، بعد الانتخابات الرئاسية 2012. بحسب بي بي سي موندو، خلال فترة تولي مادورو منصب وزير الخارجية، "كان يُعتبر لاعباً رئيسياً في دفع السياسة الخارجية لبلاده إلى ما وراء حدود أمريكا اللاتينية، والتقرب من أي حكومة تُنافس الولايات المتحدة".[56]

تضمنت مواقف السياسة الخارجية لڤنزويلا خلال فترة ولايته إنهاء العلاقات مع تايوان لصالح العلاقات مع جمهورية الصين الشعبية،[57][58] دعم ليبيا في عهد معمر القذافي، وقطع العلاقات الدبلوماسية مع إسرائيل أثناء حرب غزة 2008-2009،[59] الاعتراف بدولة فلسطين وإقامة علاقات دبلوماسية معها،[60] التحول في العلاقات مع كولومبيا عام 2008 ومرة أخرى عام 2010،[61] الاعتراف بأبخازيا وأوستيا الجنوبية كدولتين مستقلتين،[62] ودعم بشار الأسد أثناء الحرب الأهلية السورية.[63]

قال تيمير پوراس، الأستاذ الزائر في معهد الدراسات السياسية في پاريس عام 2019 والذي كان كبير موظفي مادورو خلال فترة توليه منصب وزير الخارجية، أنه في الأيام الأولى من حكم تشاڤيز، كان يُنظر إلى مادورو باعتباره "پراغماتياً" و"سياسياً ماهراً للغاية" و"جيد في التفاوض والمساومة".[64] بحسب روري كارول، لم يكن مادورو يتحدث أي لغات أجنبية أثناء توليه منصب وزير الخارجية.[65]

الاحتجاز في نيويورك 2006

في مدينة نيويورك في سبتمبر 2006، وأثناء محاولته العودة إلى ڤنزويلا عبر ميامي، فلوريدا، احتُجز مادورو لفترة وجيزة من قبل ضباط وزارة الأمن الداخلي الأمريكية في مطار جون كندي الدولي لمدة تسعين دقيقة تقريباً، بعد أن دفع ثمن ثلاث تذاكر طيران نقداً. وكان كل من مادورو والرئيس هوگو تشاڤيز في مدينة نيويورك لحضور الدورة الحادية والستين للجمعية العامة للأمم المتحدة، حيث وصف الرئيس تشاڤيز الرئيس الأمريكي جورج بوش الابن "بالشيطان" خلال خطابه أمام الأمم المتحدة عام 2006.[66]

بدأ الحادث عندما حاول مادورو استلام غرض تم فحصه عند نقطة تفتيش أمنية في المطار، فأبلغه رجال الأمن أنه ممنوع من ذلك. عرّف مادورو نفسه لاحقاً بأنه دبلوماسي من الحكومة الڤنزويلية، لكن المسؤولين اصطحبوه مع ذلك إلى غرفة لإجراء تفتيش إضافي.[67] في مرحلة ما، أمرت السلطات مادورو ومسؤولين ڤنزويليين آخرين بتفتيشهم، لكنهم رفضوا بشدة. أُحتجز جواز سفره الدبلوماسي وتذكرته لفترة، ثم أعيدا إليه في النهاية.[68]

في كلمة ألقاها أمام البعثة الڤنزويلية لدى الأمم المتحدة عقب إطلاق سراحه، صرّح مادورو بأن احتجازه من قبل السلطات الأمريكية غير قانوني، وأنه قدّم شكوى لدى الأمم المتحدة. ووصف مسؤولون أمريكيون وأمميون الحادث بأنه "مؤسف"، لكنهم قالوا إن مادورو خضع "لفحص إضافي". وادّعى المتحدث باسم وزارة الأمن الداخلي، روس نوك، أن مادورو لم يتعرض لسوء المعاملة، قائلاً إنه لا يوجد دليل على وجود مخالفات خلال عملية الفحص. وقال مادورو إن الحادث منعه من السفر إلى بلاده في اليوم نفسه.[68]

عندما تم إبلاغه بالحادثة، قال الرئيس تشاڤيز إن اعتقال مادورو كان انتقاماً لخطابه أمام الجمعية العامة للأمم المتحدة، وذكر أن السلطات اعتقلته بسبب صلاته بمحاولة الانقلاب الڤنزويلية الفاشلة 1992، وهو اتهام نفاه الرئيس تشاڤيز.[68]

نائب رئيس ڤنزويلا

قبل تعيينه نائباً للرئيس، اختار تشاڤيز مادورو عام 2011 ليخلفه في الرئاسة في حال وفاته بمرض السرطان. وقد اتُخذ هذا الاختيار نظراً لولائه لتشاڤيز وعلاقاته الجيدة مع شخصيات أخرى من الحركة التشاڤيزية، مثل إلياس خاوا، والوزير السابق خسي تشاكون، وخورخى رودريگيز. وتوقع مسؤولون بوليڤاريون[من؟] أن يواجه مادورو صعوبات سياسية بعد وفاة تشاڤيز، وأن تشهد ڤنزويلا حالة من عدم الاستقرار.[69]

في 13 أكتوبر 2012، عيّن تشاڤيز مادورو نائباً للرئيس، بعد فترة وجيزة من فوز تشاڤيز في الانتخابات الرئاسية التي أُجريت في ذلك الشهر. وفي 8 ديسمبر 2012، أعلن تشاڤيز عودة مرض السرطان الذي كان يعاني منه، وأنه سيعود إلى كوبا لإجراء جراحة طارئة وتلقي المزيد من العلاج. وقال تشاڤيز إنه في حال تدهورت حالته الصحية ودُعيت إلى انتخابات رئاسية جديدة لاختيار خليفة له، فعلى الڤنزويليين التصويت لمادورو. وكانت هذه المرة الأولى التي يُسمّي فيها تشاڤيز خليفة محتملاً لحركته، والمرة الأولى التي يُقرّ فيها علناً باحتمالية وفاته.[70][71]

أدى تأييد تشاڤيز لمادورو إلى تهميش ديوسدادو كابلو، نائب الرئيس السابق والمسؤول النافذ في الحزب الاشتراكي المتحد، والذي تربطه علاقات بالقوات المسلحة، والذي كان يُعتبر على نطاق واسع المرشح الأبرز لخلافة تشاڤيز. بعد أن أعلن تشاڤيز تأييده لمادورو، تعهد كابلو على الفور بالولاء للرجلين.[72]

الرئيس بالإنابة

—هوگو تشاڤيز في خطاب تلفزيوني (كادينا ناسيونال) (8 ديسمبر 2012)[61]

بعد وفاة هوگو تشاڤيز في 5 مارس 2013، تولى مادورو صلاحيات ومسؤوليات الرئيس، وعيّن خورخى أريازا نائباً له. ولأن تشاڤيز توفي خلال السنوات الأربع الأولى من ولايته، ينص الدستور الڤنزويلي على إجراء انتخابات رئاسية في غضون 30 يوماً من وفاته.[73][74][75] تم اختيار مادورو بالإجماع كمرشح الحزب الاشتراكي في الانتخابات.[76] عندما تولى مادورو السلطة مؤقتاً، زعم قادة المعارضة أنه انتهك المواد 229 و231 و233 من الدستور الڤنزويلي، بتوليه السلطة بدلاً من رئيس الجمعية الوطنية.[77][78]

رئاسة ڤنزويلا

بحسب كوراليس وپنفولد، يعود وصول مادورو إلى الرئاسة عام 2013 إلى آليات متعددة أرساها سلفه تشاڤيز. ففي البداية، كانت أسعار النفط مرتفعة بما يكفي ليتمكن مادورو من الحفاظ على الإنفاق اللازم لدعم البلاد، لا سيما الجيش. كما استغل مادورو العلاقات الخارجية التي بناها تشاڤيز، مستفيداً من المهارات التي اكتسبها خلال فترة توليه منصب وزير الخارجية. وأخيراً، اصطفت مؤسسات الحزب الاشتراكي المتحد والمؤسسات الحكومية خلف مادورو، و"استخدم النظام مؤسسات القمع والاستبداد، التي أُنشئت أيضاً في عهد تشاڤيز، لتعزيز قمعه للمعارضة".[79]

في أبريل 2013، انتُخب مادورو رئيساً لڤنزويلا، متفوقاً بفارق ضئيل على مرشح المعارضة هنريك كاپريليس، حيث لم يفصل بينهما سوى 1.5% من الأصوات. وطالب كاپريليس بإعادة فرز الأصوات، رافضاً الاعتراف بصحة النتيجة.[80] نُصب مادورو رئيساً في 19 أبريل، بعد أن وعدت لجنة الانتخابات بإجراء تدقيق كامل لنتائج الانتخابات.[81][82] في أكتوبر 2013، أعلن مادورو عن تأسيس وكالة جديدة، هي وكالة وزارة السعادة العليا، لتنسيق البرامج الاجتماعية.[83]

في مايو 2016 قام قادة المعارضة في ڤنزويلا بتسليم عريضة إلى المجلس الانتخابي الوطني تدعو إلى إجراء استفتاء على سحب الثقة، حيث يصوت الشعب على ما إذا كان سيتم عزل مادورو من منصبه.[84] في 5 يوليو 2016، احتجزت المخابرات الڤنزويلية خمسة نشطاء معارضين متورطين في استفتاء سحب الثقة، كما أُعتقل ناشطين آخرين من نفس الحزب، الإرادة الشعبية.[85] بعد تأخيرات في التحقق من التوقيعات، زعم المتظاهرون أن الحكومة تتعمد تأخير العملية. وردت الحكومة بأن المتظاهرين جزء من مؤامرة للإطاحة بمادورو.[86] في 1 أغسطس 2016، أعلنت اللجنة الوطنية للانتخابات أنه تم التحقق من صحة عدد كافي من التوقيعات لاستئناف عملية سحب الثقة. وبينما ضغط قادة المعارضة لإجراء سحب الثقة قبل نهاية عام 2016، لإتاحة الفرصة لإجراء انتخابات رئاسية جديدة، تعهدت الحكومة بعدم إجراء سحب الثقة قبل عام 2017، مما يضمن وصول نائب الرئيس الحالي إلى السلطة.[87]

في مايو 2017، اقترح مادورو إجراء انتخابات الجمعية التأسيسية الڤنزويلية 2017، والتي أجريت لاحقاً في 30 يوليو 2017 على الرغم من الإدانة الدولية الدامغة.[88][89] عقب الانتخابات فرضت الولايات المتحدة عقوبات على مادورو، ووصفته بأنه "ديكتاتور"، ومنعته من دخول الولايات المتحدة.[90] ودول أخرى، مثل الصين،[91] أبدت روسيا،[92] وكوبا [93] دعمهم لمادورو وانتخابات الجمعية التأسيسية. وتم تقديم موعد الانتخابات الرئاسية، التي كان من المقرر إجراؤها في ديسمبر 2018، إلى 22 أبريل، قبل تأجيلها إلى 20 مايو.[94][95][96] وصف المحللون الاستطلاع بأنه انتخابات استعراضية،[97][98] وشهدت الانتخابات أدنى نسبة مشاركة للناخبين في العصر الديمقراطي الذي تشهده البلاد.[99][100]

ابتداءً من ستة أشهر بعد انتخابه، مُنح مادورو سلطة الحكم بمرسوم من قبل المجلس التشريعي الڤنزويلي السابق لعام 2015 (من 19 نوفمبر 2013 إلى 19 نوفمبر 2014، ومن 15 مارس 2015 إلى 31 ديسمبر 2015)[6] وفي وقت لاحق من قبل المحكمة العليا (منذ 15 يناير 2016) لمعالجة الأزمة الاقتصادية المستمرة في ڤنزويلا، مع إدانة شديدة من المعارضة الڤنزويلية التي زعمت أن المحكمة قد اغتصبت سلطة المجلس التشريعي.[101][102] تزامنت رئاسته مع تدهور الوضع الاجتماعي والاقتصادي في ڤنزويلا، حيث ازدادت معدلات الجريمة والتضخم والفقر والجوع؛ وقد عزا المحللون تدهور ڤنزويلا إلى السياسات الاقتصادية لكل من تشاڤيز ومادورو،[103][104] بينما ألقى مادورو باللوم على المضاربة والحرب الاقتصادية التي شنها خصومه السياسيون.[105]

وقد اتهم تقرير صادر عن منظمة العفو الدولية عام 2018 حكومة نيكولاس مادورو "بارتكاب بعض أسوأ انتهاكات حقوق الإنسان في تاريخ ڤنزويلا".[106] وخلص التقرير إلى أن العنف تم تنفيذه بشكل خاص في الأحياء الفقيرة في ڤنزويلا، وشمل "8292 عملية إعدام خارج نطاق القضاء تم تنفيذها بين عامي 2015 و2017".[106] في عام واحد، ارتكبت قوات الأمن 22% من جرائم القتل (4667 جريمة).[106] وقالت إريكا گيڤارا روزاس من منظمة العفو الدولية: "ينبغي على حكومة الرئيس مادورو أن تضمن الحق في الحياة، بدلاً من إزهاق أرواح شباب البلاد".[106]

خلال السنوات الأخيرة من رئاسة مادورو، شنت قوات الشرطة والجيش الموالية للحكومة ما أسمته "عملية تحرير الشعب"، والتي زعمت أنها استهدفت عصابات الشوارع والتشكيلات شبه العسكرية غير الحكومية التي سيطرت على الأحياء الفقيرة. وأسفرت العمليات، بحسب التقارير، عن آلاف الاعتقالات ومقتل ما يقدر بنحو 9.000 شخص، في حين ادعت المعارضة الڤنزويلية أن هذه العمليات ما هي إلا أداة قمع حكومية. وقد أصدرت الأمم المتحدة تقريراً يدين أساليب العنف المستخدمة في العملية. ورغم اعتراف أمين المظالم في الحكومة الڤنزويلية، طارق وليام صعب، بتلقي مكتبه عشرات البلاغات عن "تجاوزات الشرطة"، إلا أنه دافع عن ضرورة العمليات، مؤكداً أن مكتبه سيعمل جنباً إلى جنب مع الشرطة والجيش "لحماية حقوق الإنسان". انتقدت وزارة الخارجية الڤنزويلية تقرير الأمم المتحدة، واصفة إياه بأنه "ليس موضوعياً ولا محايداً"، وسردت ما اعتقدت أنه 60 خطأً في التقرير.[107][108]

في 4 أغسطس 2018، انفجرت مسيرتان على الأقل مزودتان بمتفجرات في المنطقة التي كان مادورو يلقي فيها خطاباً أمام ضباط عسكريين في ڤنزويلا.[109] وتزعم الحكومة الڤنزويلية أن الحادث كان محاولة اغتيال مادورو، على الرغم من أن سبب ونية الانفجارات محل نقاش.[110][111] وقد أشار آخرون[من؟] إلى أن الحادثة كانت عملية راية كاذبة من قبل الحكومة لتبرير قمع المعارضة في ڤنزويلا.[112][113][114]

عام 2019، قال پوراس، الرئيس السابق لديوان مادورو، إن مادورو "لم يقدم شيئاً يُذكر فيما يتعلق بالسياسة العامة، أو فيما يتعلق بالتوجيه" خلال ولايته الأولى، لأنه، في رأي پوراس، "لا يملك رؤية واضحة للبلاد. إنه يركز بشكل كبير على توطيد سلطته بين نظرائه في نظام تشاڤيز، وأقل بكثير على ممارسة أو تنفيذ رؤية استراتيجية للبلاد".[64] في أعقاب زيادة العقوبات الدولية أثناء الأزمة الڤنزويلية 2019، تخلت حكومة مادورو عن السياسات الاشتراكية التي أرساها تشاڤيز، مثل مراقبة الأسعار والعملة، مما أدى إلى انتعاش البلاد من التدهور الاقتصادي.[115] أفادت الإكونومست أن ڤنزويلا حصلت أيضاً على "أموال إضافية من بيع الذهب (سواء من المناجم غير القانونية أو من احتياطياتها) والمخدرات".[115]

في 3 مايو 2020، أحبطت قوات الأمن الڤنزويلية، في محاولة للإطاحة بمادورو قام بها معارضون ڤنزويليون مسلحون. نُظّمت المحاولة من قِبل شركة أمن أمريكية خاصة، سيلڤركورپ يوإسإيه، برئاسة جوردان گودرو، وتلقى عناصرها تدريباً في كولومبيا. زعم گودرو أن العملية شارك فيها 60 جندياً، من بينهم عضوان سابقان في القوات الخاصة الأمريكية.[116][117] زعمت الحكومة الڤنزويلية أن الولايات المتحدة وإدارة مكافحة المخدرات التابعة لها كانتا مسؤولتين عن العملية وأنهما تلقتا دعماً من كولومبيا.[118] نفى خوان گوايدو تورطه في العملية. وادعى گودرو أن گوايدو واثنين من مستشاريه السياسيين وقعوا معه عقداً بقيمة 213 مليون دولار أمريكي في أكتوبر 2019.[117] قُتل ثمانية من المهاجمين، بينما أُلقي القبض على ثلاثة عشر آخرين، بينهم أمريكيان.[119][120]

في أكتوبر 2020، وجهت محكمة فدرالية أمريكية لائحة اتهام إلى مادورو بتهمة الإرهاب المرتبط بالمخدرات والتآمر لاستيراد الكوكايين إلى الولايات المتحدة.[121] في أغسطس 2025، رفعت وزارة العدل الأمريكية المكافأة المرصودة للقبض على مادورو إلى 50 مليون دولار أمريكي.[121] بدأت الولايات المتحدة سلسلة من الإجراءات التصعيدية بما في ذلك في 10 ديسمبر 2025 الاستيلاء على ناقلة النفط سكيپر في المياه الدولية قبالة الساحل الڤنزويلي.

في أكتوبر 2025، أفادت التقارير أن الولايات المتحدة حاولت، على ما يبدو، القبض على مادورو عبر عملية مموة تضمنت محاولة تجنيد طياره الشخصي، الجنرال بيتنر ڤيليگاس. وبحسب أسوشيتد پرس، التقى عميل الأمن الداخلي الأمريكي إدوين لوپيز بڤيليگاس في جمهورية الدومنيكان وعرض عليه ثروة مقابل تحويل مسار طائرة مادورو إلى موقع يُمكّن السلطات الأمريكية من إضفاء الشرعية على اعتقاله، الذي كان يواجه تهماً تتعلق بالإرهاب المرتبط بالمخدرات. وعلى مدار الستة عشر شهراً التالية، حافظ لوپيز على اتصال مشفر مع الطيار، لكن الخطة فشلت عندما رفض ڤيليگاس التعاون. وكانت المؤامرة قد بدأت بناءً على معلومة وردت في أبريل 2024 حول طائرات مادورو، والتي صودرت لاحقاً في سانتو دومنگو لانتهاكها العقوبات. عام 2025، وبعد فشل محاولات لوپيز الأخيرة لإقناع ڤيليگاس، نشر حلفاء المعارضة الڤنزويلية اتصال العميل بالطيار، مما أثار لفترة وجيزة تكهنات حول مصير ڤيليگاس قبل أن يظهر علناً مؤكداً ولاءه لمادورو.[122][123]

في 24 نوفمبر 2025، صنّفت إدارة ترمپ رسمياً هو وحلفاءه الحكوميين كأعضاء في جماعة إرهابية أجنبية.[22]

في 3 يناير 2026، أثناء الضربات الأمريكية على ڤنزويلا أعلن دونالد ترمپ إن الولايات المتحدة ألقت القبض على مادورو وزوجته.[1][2]

العلاقات الدولية

في 6 مارس 2014، بمناسبة الذكرى السنوية الأولى لوفاة هوگو تشاڤيز، أعلن مادورو على الهواء مباشرة على التلفزيون الرسمي أنه سيقطع العلاقات الدبلوماسية والتجارية مع پنما بعد أن أعرب رئيس البلاد ريكاردو مارتينلي عن دعمه للمتظاهرين أثناء الاحتجاجات التي بدأت في 12 فبراير 2014 ودعا منظمة الدول الأمريكية إلى التحقيق.[124] تم استعادة العلاقات لاحقاً في يوليو 2014، بعد أن حضر نائب الرئيس خورخى أريازا حفل تنصيب الرئيس خوان كارلوس ڤاريلا.[125][126]

في 11 أغسطس 2017، قال الرئيس الأمريكي دونالد ترمپ أنه "لن يستبعد الخيار العسكري" لمواجهة حكومة مادورو.[127] في 23 يناير 2019، أعلن مادورو أن ڤنزويلا ستقطع علاقاتها مع الولايات المتحدة بعد إعلان الرئيس ترمپ الاعتراف بخوان گوايدو، زعيم المعارضة الڤنزويلية، رئيساً مؤقتاً لڤنزويلا.[128]

عام 2018 وقعت أزمة دبلوماسية أخرى مع پنما، بعد أن فرضت الحكومة الپنمية عقوبات على مادورو وعدد من كبار مسؤولي الحكومة البوليڤارية. وردت ڤنزويلا بفرض عقوبات مماثلة على شركات پنمية ومسؤولين پنميين بارزين، بمن فيهم الرئيس خوان كارلوس ڤاريلا.[129] انتهت الأزمة الدبلوماسية في 26 أبريل 2018 عندما أعلن الرئيس مادورو أنه اتصل بالرئيس ڤاريلا واتفقا على عودة السفراء واستئناف الاتصالات الجوية بين البلدين.[130]

في 14 يناير 2019، وبعد أيام من اعتراف البرازيل بزعيم المعارضة الڤنزويلية خوان گوايدو رئيساً مؤقتاً للبلاد، وصف مادورو الرئيس البرازيلي جائير بولسونارو بأنه "هتلر العصر الحديث".[131]

تربط مادورو شراكة استراتيجية مع الرئيس الروسي ڤلاديمير پوتن. بعد الغزو الروسي لأوكرانيا في فبراير 2022، ناقش مادورو تعزيز التعاون مع روسيا.[132][133] نتيجة لارتفاع أسعار النفط الناجم عن النزاع، بدأت محادثات دبلوماسية بين مادورو ومسؤولين أمريكيين، مما يشير إلى إمكانية تخفيف العقوبات الأمريكية المفروضة على ڤنزويلا وتحسين العلاقات بين البلدين.[134][135][136] في أواخر عهد إدارة بايدن، رفع مكتب مراقبة الأصول الأجنبية التابع لوزارة الخزانة الأمريكية العقوبات في أكتوبر 2023 لمدة ستة أشهر للسماح باستئناف التجارة المحدودة مع الولايات المتحدة.[137][معلومات قديمة]

خلال مؤتمر الأمم المتحدة لتغير المناخ في نوفمبر 2022، تفاعل العديد من قادة العالم مع مادورو، بمن فيهم الرئيس الفرنسي إيمانوِيل ماكرون، ورئيس الوزراء الپرتغالي أنطونيو كوستا، والأمريكي جون كيري، حيث خاطب ماكرون مادورو بصفة "الرئيس" وقال: "سأكون سعيداً إذا تمكنا من التحدث مع بعضنا البعض لفترة أطول للمشاركة في عمل ثنائي مفيد للمنطقة".[133][138] وبعد أيام، في 27 نوفمبر، خففت الولايات المتحدة العقوبات المفروضة على ڤنزويلا وسمحت لشركة شڤرون بالعمل مؤقتاً مع الحكومة الڤنزويلية.[139]

قام مادورو بزيارة دولة رسمية إلى السعودية في يونيو 2023.[140] كما زار الصين في سبتمبر 2023، طالباً دعم الصين لانضمام ڤنزويلا إلى مجموعة البريكس الاقتصادية، ومؤكداً رغبته في زيادة الاستثمارات الصينية في أمريكا اللاتينية ومنطقة الكاريبي. وقد أيّد الرئيس البرازيلي لولا دا سيلڤا طلب مادورو بالانضمام إلى البريكس.[141] خلال الزيارة، وقّع مادورو أيضاً اتفاقية تضمنت تدريب رواد فضاء ڤنزويليين، معرباً عن رغبته في إرسال ڤنزويليين إلى القمر.[142]

في الصراع الإسرائيلي الفلسطيني، دعم مادورو القضية الفلسطينية مراراً وتكراراً في المحافل الدولية، مصرحاً بأن "يسوع المسيح كان شاباً فلسطينياً صُلب ظلماً على يد الإمبراطورية الإسپانية".[143] في 7 نوفمبر 2023، أدان أعمال إسرائيل الوحشية في قطاع غزة أثناء حرب غزة، واتهم إسرائيل بارتكاب إبادة جماعية ضد الفلسطينيين في غزة.[144]

روّج مادورو لاستفتاء استشاري في ڤنزويلا عام 2023 لدعم مطالبة ڤنزويلا بمنطقة إيسيكويبو، المتنازع عليها مع گويانا المجاورة والتي تسيطر عليها الأخيرة. جرى الاستفتاء في 3 ديسمبر 2023، وصوّتت أغلبية ساحقة (ما يقارب 100%) لصالح مطالب ڤنزويلا، على الرغم من انخفاض نسبة المشاركة.[145][146] كان الاستفتاء أحد العوامل المساهمة في الأزمة بين گويانا وڤنزويلا.[147]

في يونيو 2025، أدان مادورو الهجمات الإسرائيلية على إيران، واصفاً إياها بأنها "اعتداء إجرامي" ينتهك القانون الدولي وميثاق الأمم المتحدة، واتهم فرنسا وألمانيا وبريطانيا والولايات المتحدة بدعم "هتلر القرن الحادي والعشرين" ضد "الشعب الإيراني النبيل والمسالم".[148]

محاولات اغتياله

خلال فترة رئاسته تعرض مادورو العديد من محاولات الاغتيال. في أغسطس/ 2018، وأثناء إلقاء خطاب بمناسبة الذكرى الحادية والثمانين لتأسيس الحرس الوطني البوليڤاري، وتوجهه إلى الجنود أمام برجي مركز سيمون بوليڤار وقصر العدل في كراكاس، انفجرت مسيرتان بالقرب من شارع بوليڤار. وتزعم الحكومة الڤنزويلية أن الحادث كان محاولة اغتيال مُستهدفة لمادورو، إلا أن سبب الانفجارات ودوافعها لا تزال محل جدل.[149][150] وقد أشار آخرون إلى أن الحادث كان عملية مدبرة من قبل الحكومة لتبرير قمع المعارضة في ڤنزويلا.[151][152][153]

في سبتمبر 2024، ألقت الشرطة الڤنزويلية القبض على ثلاثة أمريكيين وإسپانيين اثنين ومواطن تشيكي كانوا يحملون بنادق قنص وذخائر أخرى بزعم اغتيال مادورو.[154] في بيانٍ عام، حمّل وزير الداخلية والعدل والسلام، ديوسدادو كابلو، وكالة المخابرات المركزية الأمريكية والمخابرات الإسپانية مسؤولية محاولة الانقلاب، واصفًا إياها بأنها "غير مفاجئة". وأعلن الوزير عن اعتقال جندي أمريكي آخر في الخدمة الفعلية، ويلبر جوسف كاستانيدا، استناداً إلى أدلة من هاتفه المحمول تربطه بهجمات إرهابية خلال الانتخابات الرئاسية الڤنزويلية 2024.[155]

جدل

الرئاسة المتنازع عليها

وسط إدانة واسعة النطاق،[15][16][17] أدى الرئيس مادورو اليمين الدستورية في 10 يناير 2019. وبعد دقائق من أدائه اليمين، أقرت منظمة الدول الأمريكية قراراً يعلن عدم شرعية رئاسته ويدعو إلى إجراء انتخابات جديدة.[156] أعلنت الجمعية الوطنية حالة الطوارئ،[157] وقامت بعض الدول بسحب سفاراتها من ڤنزويلا،[158][159] وقامت كولومبيا،[160] والولايات المتحدة[161] إن مادورو يحول ڤنزويلا إلى دكتاتورية بحكم الأمر الواقع. وقد أُعلن رئيس الجمعية الوطنية، خوان گوايدو، رئيساً مؤقتاً في 23 يناير 2019؛[162] أيدت الولايات المتحدة وكندا والبرازيل والعديد من بلدان أمريكا اللاتينية گوايدو كرئيس مؤقت في اليوم نفسه؛ بينما أيدت روسيا والصين وكوبا مادورو.[18][19] اعتباراً من مارس 2019، فإن أكثر من 50 بلد، ومنظمة الدول الأمريكية، ومجموعة ليما لا تعترف بمادورو كرئيس شرعي لڤنزويلا.[163][164][165] رفضت المحكمة العليا قرارات الجمعية الوطنية،[18] بينما رحبت المحكمة العليا الڤنزويلية في المنفى بگوايدو كرئيس مؤقت.[166] أصدرت وزارة الخارجية الأمريكية بياناً يفيد بأن مادورو قد استخدم وسائل غير دستورية و"نظاماً انتخابياً صورياً" للحفاظ على رئاسة غير شرعية لا تعترف بها معظم دول الجوار الڤنزويلية.[167]

رفض مادورو مزاعم گوايدو وقطع العلاقات الدبلوماسية مع العديد من الدول التي اعترفت بمزاعم گوايدو.[168] وتزعم حكومة مادورو أن الأزمة عبارة عن "انقلاب" تقوده الولايات المتحدة للإطاحة به والسيطرة على احتياطيات النفط في البلاد.[169][170]

الاتهامات بالديكتاتورية

اتُهم مادورو بالقيادة السلطوية منذ توليه منصبه عام 2013.[171] بعد فوز المعارضة في الانتخابات البرلمانية 2015،[172] الجمعية الوطنية المغادرة - التي تتألف من النخبة البوليڤارية المؤيدة لمادورو - ملأت المحكمة العليا بحلفاء مادورو؛[173] أفادت نيويورك تايمز بأن ڤنزويلا "تقترب من الحكم الفردي".[172]

عام 2016، رفضت المحكمة العليا الاعتراف بمحاولات الجمعية الوطنية المنتخبة ديمقراطياً لعزل مادورو، وبدأت كلمتا ديكتاتور وسلطوية بالظهور: ونشرت فورين أفيرز عن "ديكتاتورية كاملة"،[174] وكتب خاڤير كارلوس في أمريكاز كوارلترلي أن ڤنزويلا "تنتقل نحو الدكتاتورية الكاملة"،[175] وقال الأمين العام لمنظمة الدول الأمريكية لويس ألماگرو إن مادورو يتحول إلى ديكتاتور.[176] بعد أن عرقل مسؤولو الانتخابات المقربون من الحكومة محاولة إجراء استفتاء لسحب الثقة من مادورو، حذر محللون سياسيون ڤنزويليون، نقلت عنهم الگارديان، من السلطوية والديكتاتورية.[177]

في مارس استولت المحكمة العليا على الصلاحيات التشريعية للجمعية الوطنية، مما أدى إلى اندلاع الأزمة الدستورية الڤنزويلية 2017؛ وتساءلت مقالة رأي لكوراليس في واشنطن پوست: "ماذا سيحدث بعد ذلك لديكتاتورية الرئيس نيكولاس مادورو؟"[178] مع استعداد الجمعية الوطنية التأسيسية 2017 لإعلان نفسها الهيئة الحاكمة لڤنزويلا،[179] فرضت وزارة الخزانة الأمريكية عقوبات على الرئيس مادورو، ووصفته بالديكتاتور، ومنعته من دخول الولايات المتحدة.[90] كما وصف الرئيس التشيلي سباستيان پنييرا مادورو بالديكتاتور.[180] وصفت هيومان رايتس واتش العملية التي أدت إلى الاستيلاء على الجمعية الوطنية، ووصفت ڤنزويلا بأنها ديكتاتورية، وقالت إن "الحكومة الڤنزويلية تشدد قبضتها على المؤسسات الديمقراطية الأساسية في البلاد بسرعة مرعبة".[181] نشرت فايننشال تايمز مقالاً بعنوان "إرسال رسالة إلى دكتاتورية ڤنزويلا" يناقش "الإدانة الدولية لنيكولاس مادورو، الرئيس الڤنزويلي المتسلط".[182] كتب مجلس تحرير صحيفة شيكاغو تريبيون رأياً مفاده أن "إدارة ترپ لا ينبغي أن تتوهم بشأن مادورو، الذي يبدو مصمماً على تولي منصب الديكتاتور".[183] نشر موقع ڤوكس ميديا مقال رأي بعنوان "كيف تحولت ڤنزويلا من ديمقراطية غنية إلى دكتاتورية على حافة الانهيار".[184]

أفادت وحدة المخابرات الاقتصادية أن الديمقراطية في البلاد تدهورت أكثر خلال فترة رئاسة مادورو، حيث خفض تقرير عام 2017 تصنيف ڤنزويلا من نظام هجين إلى نظام سلطوي، وهي أدنى فئة، بمؤشر 3.87 (ثاني أدنى مؤشر في أمريكا اللاتينية، إلى جانب كوبا)، مما يعكس "انزلاق ڤنزويلا المستمر نحو الديكتاتورية" حيث قامت الحكومة بتهميش الجمعية الوطنية التي تهيمن عليها المعارضة، وسجن أو حرمان كبار السياسيين المعارضين من حقوقهم المدنية، وقمع الاحتجاجات المعارضة بعنف.[185]

أُجريت الانتخابات الرئاسية قبل موعدها في مايو 2018؛ نشرت صحيفة نيويورك تايمز مقالاً إخبارياً عن الانتخابات، بعنوان "المنتقدون يقولون إنه لا يستطيع هزيمة ديكتاتور. هذا الڤنزويلي يعتقد أنه يستطيع".[186] كتب مگيل أنجيل لاتوش، أستاذ العلوم السياسية في جامعة ڤنزويلا المركزية، مقالاً رأياً بعنوان "ڤنزويلا الآن ديكتاتورية"،[187] وأفادت سي إن إن بأن الجمهوريين الأمريكيين كانوا يستخدمون مصطلح الديكتاتور الڤنزويلي لوصف مرشح ديمقراطي.[188] كتب روجر نورييگا في ميامي هرالد أن "نظاماً خارجاً عن القانون" و"ديكتاتورية مخدرات" بقيادة مادورو وطارق العيسمي وديوسدادو كابلو قد دفعوا "ڤنزويلا إلى حافة الانهيار".[189]

أُدينت على نطاق واسع مراسم تنصيب مادورو الثاني في 10 يناير 2019[190][191] وأدى ذلك إلى مزيد من التعليقات التي تفيد بأن مادورو قد عزز سلطته وأصبح ديكتاتوراً، وذلك بحسب آيرس تايمز،[192] التايمز،[193] ومجلس العلاقات الخارجية،[194] صحيفة فرانكفورتر ألگماين زايتونگ الألمانية،[195] والإكونومست.[196]

ووصف رئيس الوزراء الكندي جستن ترودو مادورو بأنه "ديكتاتور غير شرعي" مسؤول عن "القمع الفظيع" والأزمة الإنسانية التي تشهدها ڤنزويلا.[197] وصرحت وزيرة الخارجية الكندية كريستيا فريلاند، قائلة: "بعد أن استولى نظام مادورو على السلطة من خلال انتخابات مزورة وغير ديمقراطية أجريت في 20 مايو 2018، أصبح الآن راسخاً تماماً كنظام ديكتاتوري".[198][199] أدان الرئيسان الأرجنتيني موريسيو ماكري والبرازيلي جائير بولسونارو ما وصفاه بديكتاتورية مادورو.[200]

وصف مذيع قناة يونيڤزيون خورخى راموس اعتقاله عقب مقابلة مباشرة مع مادورو، قائلاً إنه إذا لم ينشر مادورو الڤيديو الذي تم الاستيلاء عليه للمقابلة، "فإنه يتصرف تماماً مثل الديكتاتور".[201] في مقابلة مع تلموندو، صرح عضو مجلس الشيوخ الأمريكي برني ساندرز قائلاً: "بالطبع مادورو ديكتاتور".[202][203] كتب الصحفي كنيث راپوزا مقال رأي لمجلة فوربس بعنوان: "الجميع يعلم الآن أن ڤنزويلا ديكتاتورية".[204]

محل الميلاد والجنسية

Article 227 of the Constitution of Venezuela

Maduro's birthplace and nationality have been questioned several times,[205][206] with some placing doubt that he could hold the office of the presidency, given that Article 227 of the Venezuelan constitution states that "To be elected as president of the Republic it is required to be Venezuelan by birth, to not hold another nationality, to be over thirty years old, to not be a member of the clergy, to not be subject to a court conviction and to meet the other requirements in this Constitution."[207] After his triumph in the 2013 presidential elections, opposition deputies warned that they would investigate the double nationality of Maduro.[بحاجة لمصدر]

By 2014, official declarations by the Venezuela government shared four different birthplaces of Maduro.[208] Tachira state's governor José Vielma Mora assured that Maduro was born in El Palotal sector of San Antonio del Táchira and that he had relatives that live in the towns of Capacho and Rubio.[209] The opposition deputy Abelardo Díaz reviewed the civil registry of El Valle, as well as the civil registry referenced by Vielma Mora, without finding any proof or documentation that could confirm Maduro's birthplace.[210] In June 2013, two months after assuming the presidency, Maduro claimed in a press conference in Rome that he was born in Caracas, in Los Chaguaramos, in San Pedro Parish. During an interview with a Spanish journalist, also in June 2013, Elías Jaua claimed that Maduro was born in El Valle parish, in the Libertador Municipality of Caracas.[207]

In October 2013, Tibisay Lucena, head of the National Electoral Council, assured in the Globovisión TV show Vladimir a la 1 that Maduro was born in La Candelaria Parish in Caracas, showing copies of the registry presentation book of all the newborns the day when allegedly Maduro was born. In April 2016 during a cadena nacional, Maduro changed his birthplace narrative once more, saying that he was born in Los Chaguaramos, specifically in Valle Abajo, adding that he was baptized in the San Pedro church.[207][211]

In 2016, a group of Venezuelans asked the National Assembly to investigate whether Maduro was Colombian in an open letter addressed to the National Assembly president Henry Ramos Allup that justified the request by the "reasonable doubts there are around the true origins of Maduro, because, to date, he has refused to show his birth certificate". The 62 petitioners, including former ambassador Diego Arria, businessman Marcel Granier and opposition former military, assuring that according to the Colombian constitution Maduro is "Colombian by birth" for being "the son of a Colombian mother and for having resided" in the neighboring country "during his childhood".[212] The same year several former members of the Electoral Council sent an open letter to Tibisay Lucena requesting to "exhibit publicly, in a printed media of national circulation the documents that certify the strict compliance with Articles 41 and 227 of the Constitution of the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela, that is to say, the birth certificate and the Certificate of Venezuelan Nationality by Birth of Nicolás Maduro Moros in order to verify if he is Venezuelan by birth and without another nationality". The document mentions that the current president of the CNE incurs in "a serious error, and even an irresponsibility, when she affirms that Maduro's nationality 'is not a motto of the National Electoral Council'" and the signatories also refer to the four different moments in which different politicians have awarded four different places of birth as official.[213] Diario Las Américas claimed to have access to the birth inscriptions of Teresa de Jesús Moros, Maduro's mother, and of José Mario Moros, his uncle, both registered in the parish church of San Antonio of Cúcuta, Colombia.[213]

Opposition deputies have assured that the birth certificate of Maduro must say that he is the son of a Colombian mother, which would represent proof that confirms that the president has double nationality and that he cannot hold any office under Article 41 of the constitution.[207] Deputy Dennis Fernández Solórzano has headed a special commission that investigates the origins of the president and has declared that "Maduro's mother is a Colombian citizen" and that the Venezuelan head of State would also be Colombian.[214] The researcher, historian and former deputy Walter Márquez declared months after the presidential elections that Maduro's mother was born in Colombia and not in Rubio, Táchira. Márquez has also declared that Maduro "was born in Bogotá, according to the verbal testimonies of people who knew him as a child in Colombia and the documentary research we did" and that "there are more than 10 witnesses that corroborate this information, five of them live in Bogotá".[215]

On 28 October 2016, the Supreme Tribunal of Justice issued a ruling stating that according to incontrovertible evidence, it had absolute certainty that Maduro was born in Caracas, in the parish of La Candelaria, known then as the Libertador Department of the Federal District, on 23 November 1962.[207] The ruling does not reproduce Maduro's birth certificate. Instead, it quotes a communique signed on 8 June by the Colombian vice-minister of foreign affairs Patti Londoño Jaramillo: "No related information was found, nor civil registry of birth, nor citizenship card that allows [us] to infer that president Nicolás Maduro Moros is a Colombian national". The Supreme Court warned the deputies and the Venezuelans that "sowing doubts about the origins of the president" may "lead to the corresponding criminal, civil, administrative and, if applicable, disciplinary consequences" for "attack against the State".[214]

On 11 January 2018, the Supreme Tribunal of Justice of Venezuela in exile decreed the nullity of the 2013 presidential elections after lawyer Enrique Aristeguieta Gramcko presented evidence about the presumed non-existence of ineligibility conditions of Maduro to be elected and to hold the office of the presidency. Aristeguieta argued in the appeal that, under Article 96, Section B, of the Political Constitution of Colombia, Nicolás Maduro Moros, even in the unproven case of having been born in Venezuela, is "Colombian by birth" because he is the son of a Colombian mother and by having resided in that territory during his youth. The Constitutional Chamber admitted the demand and requested the presidency and the Electoral Council to send a certified copy of the president's birth certificate, in addition to his resignation from Colombian nationality.[216] In March 2018 former Colombian president Andrés Pastrana made reference to the baptism certificate of Maduro's mother, noting that the disclosed document reiterates the Colombian origin of the mother of the president and that therefore Maduro has Colombian citizenship.[214]

Conspiracy theories

Maduro continued the practice of his predecessor, Hugo Chávez, of denouncing alleged conspiracies against him or his government; in a period of fifteen months following his election, dozens of conspiracies, some supposedly linked to assassination and coup attempts, were reported by Maduro's government.[217] In this same period, the number of attempted coups claimed by the Venezuelan government outnumbered all attempted and executed coups occurring worldwide in the same period.[218] In TV program La Hojilla, Mario Silva, a TV personality of the main state-run channel Venezolana de Televisión, stated in March 2015 that Maduro had received about 13 million psychological attacks.[219]

Observers say that Maduro uses such conspiracy theories as a strategy to distract Venezuelans from the root causes of problems facing his government.[220][217][221][222] According to American news publication Foreign Policy, Maduro's predecessor, Hugo Chávez, "relied on his considerable populist charm, conspiratorial rhetoric, and his prodigious talent for crafting excuses" to avoid backlash from troubles Venezuela was facing, with Foreign Policy further stating that for Maduro, "the appeal of reworking the magic that once saved his mentor is obvious".[218] Andrés Cañizales, a researcher at the Andrés Bello Catholic University, said that as a result of the lack of reliable mainstream news broadcasting, most Venezuelans stay informed via social networking services, and fake news and internet hoaxes have a higher impact in Venezuela than in other countries.[223]

In early 2015, the Maduro government accused the United States of attempting to overthrow him. The Venezuelan government performed elaborate actions[مطلوب توضيح] to respond to such alleged attempts and to convince the public that its claims were true.[218] The reactions included the arrest of Antonio Ledezma in February 2015, placing travel restrictions on American tourists and holding military marches and public exercises "for the first time in Venezuela's democratic history".[218] After the United States ordered sanctions to be placed on seven Venezuelan officials for human rights violations, Maduro used anti-U.S. rhetoric to bump up his approval ratings.[224][225] However, according to Venezuelan political scientist Isabella Picón, only about 15% of Venezuelans believed in the alleged coup attempt accusations at the time.[218]

In 2016, Maduro again claimed that the United States was attempting to assist the opposition with a coup attempt.[بحاجة لمصدر] On 12 January 2016, the Secretary General of the Organization of American States (OAS), Luis Almagro, threatened to invoke the Inter-American Democratic Charter, an instrument used to defend democracy in the Americas when threatened, when opposition National Assembly members were barred from taking their seats by the Maduro-aligned Supreme Court.[226] Human rights organizations such as Human Rights Watch,[227] and the Human Rights Foundation[228] called for the OAS to invoke the Democratic Charter. After more controversies and pursuing a recall on Maduro, on 2 May 2016, opposition members of the National Assembly met with OAS officials to ask for the body to implement the Democratic Charter.[229] Two days later on 4 May, the Maduro government called for a meeting the next day with the OAS, with Venezuelan Foreign Minister Delcy Rodríguez stating that the United States and the OAS were attempting to overthrow Maduro.[230] On 17 May 2016 in a national speech, Maduro called OAS Secretary General Luis Almagro "a traitor" and stated that he worked for the CIA.[231] Almagro sent a letter rebuking Maduro, and refuting the claim.[232]

The Trump administration described Maduro's government as a "dictatorship".[234] When meeting with Latin American leaders during the seventy-second session of the UN General Assembly, US President Donald Trump discussed possible United States military intervention in Venezuela, to which they all denied the offer.[235] Maduro's son, Nicolás Maduro Guerra, stated during the 5th Constituent Assembly of Venezuela session that if the United States were to attack Venezuela, "the rifles would arrive in New York, Mr. Trump, we would arrive and take the White House".[236]

Michael Shifter, president of the Inter-American Dialogue think tank, said "a military action of the United States against Venezuela would be contrary to the movements of the Trump administration to retire troops from Syria or Afghanistan."[237] John Bolton declared that "all options are on the table" but has also said that "our objective is a peaceful transfer of power".[238]

Censorship

During Maduro's first tenure, between 2013 and 2018, 115 media outlets were shut down, including 41 print outlets, 65 radio outlets and 9 television channels.[239] During the first seven months of 2019, the Press and Society Institute of Venezuela found at least 350 cases of violations of freedom of expression .[240]

Since the beginning of the presidential crisis, Venezuela has been exposed to frequent "information blackouts", periods without access to the Internet or other news services during important political events.[30][241] Since January, the National Assembly, and Guaido's speeches are regularly disrupted, television channels and radio programs have been censored, and many journalists were illegally detained.[30] The Venezuelan press workers union reported that in 2019, 40 journalists had been arrested unlawfully as of 12 March.[242] As of June 2019, journalists have been denied access to seven sessions of the National Assembly by the National Guard.[243]

The state controls most Venezuelan television channels, and information unfavorable to the government is not covered completely.[30] Newspapers and magazines are scarce, as most cannot afford paper to print.[30] The underfunded web infrastructure has led to slow Internet connection speeds.[30] The information blackouts have promoted the creation of underground news coverage that is usually broadcast through social media and instant message services like WhatsApp.[30] The dependence of Venezuelans on social media has also promoted the spread of disinformation and pro-Maduro propaganda.[30]

Venezuela's rank on the World Press Freedom Index of Reporters Without Borders has dropped 42 places since 2013.[23][244]

The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) has made a call to the Maduro administration to reestablish TV and radio channels that have been closed, cease the restrictions on Internet access, and protect the rights of journalists.[245][246]

Human rights

—Maduro said on 23 April 2024 in an event held at the Miraflores presidential palace, with Karim Khan (the prosecutor of the International Criminal Court), who is investigating Venezuela for possible human right crimes, standing next to him. In the event Maduro said he agreed to allow the reopening of the office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR). The UN Human Rights Office was expelled from Venezuela in February after it had expressed concern over the detention of Rocío San Miguel.[247][248]

A Board of Independent Experts designated by the Organization of American States (OAS) published a 400-page report in 2018 that alleged that crimes against humanity have been committed in Venezuela during Maduro's presidency.[31] The Board concluded that Maduro could be "responsible for dozens of murders, thousands of extra-judicial executions, more than 12,000 cases of arbitrary detentions, more than 290 cases of torture, attacks against the judiciary and a 'state-sanctioned humanitarian crisis' affecting hundreds of thousands of people".[249]

In February 2018, the International Criminal Court (ICC) announced that it would open preliminary probes into the alleged crimes against humanity performed by Venezuelan authorities.[250] On 27 September 2018, six states parties to the Rome Statute: Argentina, Canada, Colombia, Chile, Paraguay and Peru, referred the situation in Venezuela since 12 February 2014 to the ICC, requesting the Prosecutor Fatou Bensouda to initiate an investigation on crimes against humanity allegedly committed in the territory. The following day, the Presidency assigned the situation to Pre-Trial Chamber I.[251]

In March 2019 The Wall Street Journal reported in an article entitled "Maduro loses grip on Venezuela's poor, a vital source of his power" that barrios are turning against Maduro and that "many blame government brutality for the shift".[252] Foro Penal said that 50 people—mostly in barrios—had been killed by security forces in only the first two months of the year, and 653 had been arrested for protesting or speaking against the government. Cofavic, a victims' rights group, estimated "3,717 extrajudicial killings in the past two years, mostly of suspected criminals in barrios".[252]

In April 2019, the US Department of State alleged that Venezuela, "led by Nicolas Maduro, has consistently violated the human rights and dignity of its citizens" and "driven a once prosperous nation into economic ruin with his authoritarian rule" and that "Maduro's thugs have engaged in extra-judicial killings and torture, taken political prisoners, and severely restricted freedom of speech, all in a brutal effort to retain power."[167] The State Department report highlighted abuse by the nation's security forces, including a number of deaths, the suspicious death of opposition politician Fernando Albán Salazar, the detention of Roberto Marrero, and repression of demonstrators during Venezuelan protests which left at least 40 dead in 2019.[167]

The third and last report of the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights addressed extrajudicial executions, torture, enforced disappearances, and other rights violations allegedly committed by Venezuelan security forces in recent years.[253] The High Commissioner Michelle Bachelet expressed her concerns for the "shockingly high" number of extrajudicial killings and urged for the dissolution of the FAES.[254] According to the report, 1569 cases of executions as consequence as a result of "resistance to authority" were registered by the Venezuelan authorities from 1 January to 19 March.[254] Other 52 deaths that occurred during 2019 protests have been attributed to colectivos.[255] The report also details how the Venezuelan government has "aimed at neutralising, repressing and criminalising political opponents and people critical of the government" since 2016.[254]

A report by the human rights advocacy group Human Rights Watch reported in September 2019 that the poor communities in Venezuela no longer in support of Maduro's government have witnessed arbitrary arrests and extrajudicial executions at the hands of Venezuelan police unit. The Venezuelan government has repeatedly declared that the victims were armed criminals who had died during "confrontations." Still, several witnesses or families of victims have challenged these claims, and in many cases, victims were last seen alive in police custody. Although Venezuelan authorities told the United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) that five FAES agents were convicted on charges including attempted murder for crimes committed in 2018 and that 388 agents were under investigation for crimes committed between 2017 and 2019, the OHCHR also reported that "[i]nstitutions responsible for the protection of human rights, such as the Attorney General's Office, the courts and the Ombudsperson, usually do not conduct prompt, effective, thorough, independent, impartial and transparent investigations into human rights violations and other crimes committed by State actors, bring perpetrators to justice, and protect victims and witnesses."[256] The government made three times more observations than the number of recommendations included in the UN report, and at the same time included false or incomplete claims.[257]

On 14 December 2020, the Office of the Prosecutor released a report on the office's year activities, stating that it believed there was a "reasonable basis" to think that "since at least April 2017, civilian authorities, members of the armed forces and pro-government individuals have committed the crimes against humanity." and that it expected to decide in 2021 whether to open an investigation or not.[258] On 4 November 2021, ICC Prosecutor Karim Khan announced the opening of an investigation regarding the situation in Venezuela.[259]

The Venezuelan human rights organization PROVEA has identified more than 43,000 people whose "right to personal integrity" has been violated since Maduro took office in 2013, including 1,652 people who were tortured, 7,309 people who were subjected to "cruel, inhumane and degrading" treatment or punishment, and at least 28 people who were killed in the country's prisons.[260]

Judicial independence

On 16 September 2021, the Independent International Fact-Finding Mission on Venezuela released its second report on the country's situation, concluding that the independence of the Venezuelan justice system under Maduro has been deeply eroded to the extent of playing an important role in aiding the state repression and perpetuating state impunity for human rights violations. The document identified frequent due process violations, including the use of pre-trial detention as a routine (rather than an exceptional measure) and judges sustaining detentions or charges based on manipulated or fabricated evidence, evidence obtained through illegal means, and evidence obtained through coercion or torture; in some of the reviewed cases, the judges also failed to protect torture victims, returning them to detentions centers were torture was denounced, "despite having heard victims, sometimes bearing visible injuries consistent with torture, make the allegation in court". The report also concluded that prosecutorial and judicial individuals at all levels witnessed or experienced external interference in decision-making and that several reported receiving instructions either from the judicial or prosecutorial hierarchy or from political officials on how to decide cases.[27][28][29]

Alleged drug trafficking and money laundering incidents

Right: Maduro reward poster issued on 26 March 2020, later increased to $50 million by August 2025

Narcosobrinos incident

Two nephews of Maduro's wife, Efraín Antonio Campo Flores and Francisco Flores de Freitas, were found guilty in a US court of conspiracy to import cocaine in November 2016, with some of their funds possibly assisting Maduro's presidential campaign in the 2013 Venezuelan presidential election and potentially for the 2015 Venezuelan parliamentary elections, with the funds mainly used to "help their family stay in power".[261][262][263] One informant stated that the two often flew out of Terminal 4 of Simon Bolivar Airport, a terminal reserved for the president.[261][262]

After Maduro's nephews were apprehended by the US Drug Enforcement Administration for the illegal distribution of cocaine on 10 November 2015, carrying diplomatic passports, Maduro posted a statement on Twitter criticizing "attacks and imperialist ambushes", saying "the Father land will continue on its path".[264] Diosdado Cabello, a senior official in Maduro's government, was quoted as saying the arrests were a "kidnapping" by the United States.[265]

On 18 November 2016, the two nephews were found guilty, with the cash allegedly destined to "help their family stay in power".[266] On 14 December 2017, the two were sentenced to 18 years of imprisonment.[267]

In October 2022, Maduro's nephews were freed in a prisoner swap for seven American directors of the oil refinery corporation CITGO (part of the Citgo Six) who were imprisoned in Venezuela.[268]

Sanctions against Tareck El Aissami and Diosdado Cabello

Ex-Venezuelan vice president Tareck El Aissami, who served Maduro from 2017 to 2018, is under U.S. sanctions for drug trafficking and aiding state terrorism. He is accused by the U.S State Department of aiding sanctioned Iran-backed terrorist organizations, including Hezbollah and Quds Force. He is also accused of having ties with various illicit organizations, including Los Zetas and Cartel of the Suns.[269][270]

On 18 May 2018, the Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) of the United States Department of the Treasury placed sanctions in effect against high-level official Diosdado Cabello. OFAC stated that Cabello and others used their power within the Bolivarian government "to personally profit from extortion, money laundering, and embezzlement", with Cabello allegedly directing drug trafficking activities with Venezuelan Vice President Tareck El Aissami while dividing drug profits with President Maduro.[271][272]

US indictment of Maduro

On 26 March 2020, the United States Department of Justice charged Maduro and other Venezuelan officials and some Colombian former FARC members for what Attorney General William Barr described as "narco-terrorism": the shipping of cocaine to the US to wage a health war on US citizens. According to Barr, Venezuelan leaders and the FARC faction organised an "air bridge" from a Venezuelan air base transporting cocaine to Central America and a sea route to the Caribbean. The US government offered $15 million for any information that would lead to his arrest.[273][274][275][276] Nicolas Maduro has frequently denied any ties to a drug trafficking syndicate. [277]

Reward increases

After Maduro was inaugurated for a third term on 10 January 2025, the US State Department announced that the reward against Maduro was increased from $15 million to $25 million. National Security Council spokesperson John Kirby said that the decision to raise the bounty as part of "a concerted message of solidarity with the Venezuelan people," meant "to further elevate international efforts to maintain pressure on Maduro and his representatives."[278] Secretary of State Antony Blinken said that the US "does not recognize Nicolas Maduro as the president of Venezuela" and a US Treasury Under Secretary, Bradley Smith, added that the US stood with its "likeminded partners" in "solidarity with the people's vote for new leadership and rejects Maduro's fraudulent claim of victory".[279]

The reward was increased again to $50 million on 7 August 2025, with Attorney General Pam Bondi accusing Maduro of collaborating with foreign terrorist organizations, such as Tren de Aragua, the Sinaloa Cartel, and the Cartel of the Suns, to bring deadly violence to the United States. In a video message, Bondi described Maduro as one of the "world's most notorious narco-traffickers" and a "threat to national security," which prompted the reward to be doubled. She concluded, "Under President Trump's leadership, Maduro will not escape justice, and he will be held accountable for his despicable crimes," before providing the public with a hotline number to report tips to the Drug Enforcement Administration.[280]

In a Fox News interview, Bondi stated that the DOJ had seized approximately $700 million in assets linked to Maduro. The assets allegedly included multiple luxury homes in Florida, a mansion in the Dominican Republic, private jets, vehicles, a horse farm, jewelry, and large sums of cash.[281] Bondi described Maduro's government as an "organized crime operation" that continued to function despite the seizures.[282]

This led to mockery of Bondi and the Trump administration on social media, with the phrase "He's in Venezuela" trending on Twitter. Some users claimed it was a deliberate distraction from the controversy surrounding the Jeffrey Epstein client list.[283] Venezuelan Foreign Minister Yván Gil dismissed the announcement as a "crude political propaganda operation," adding that he was not surprised given Bondi's failure to deliver the client list of the convicted sex offender Jeffrey Epstein.[284][285] Venezuelan Vice President Delcy Rodríguez dismissed Bondi's allegations as a "shameless," accusing her of staging a "cardboard cutout" performance to continue a "ridiculous and cheap show" against Maduro. Rodríguez further claimed that Bondi was not in her right mind, suggesting that the Epstein case was keeping her up at night.[286] Maduro, for his part, dared Trump to arrest him during a nationally televised speech and warned American leaders not to even attempt such an action, saying it would provoke a response that could also lead to the end of the American empire.[287][288]

Homophobic statements

As foreign minister, during a tenth anniversary gathering commemorating the 2002 Venezuelan coup d'état attempt going into the 2012 Venezuelan presidential election, Maduro called opposition members "snobs" and "little faggots."[289][290]

During the presidential campaign of 2013, Maduro used anti-gay attacks as a political weapon, calling representatives of the opposition "faggots".[291] Maduro used anti-gay speech toward his opponent Henrique Capriles calling him a "little princess" and saying "I do have a wife, you know? I do like women!"[291][292][293]

In 2017, Maduro expressed his personal support for same-sex marriage.[294][295]

Hunger crisis

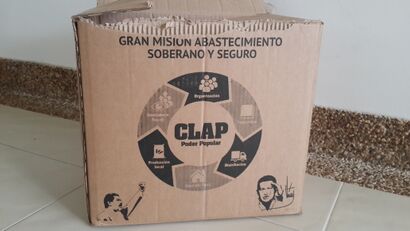

In August 2017, Luisa Ortega Díaz, Chief Prosecutor of Venezuela from 2007 until her sacking in August 2017, accused Maduro of profiting from the shortages in Venezuela. The government-operated Local Committees for Supply and Production (CLAP), which provides food to impoverished Venezuelans, made contracts with Group Grand Limited, a company that Ortega said was "presumably owned by Nicolás Maduro" through front-men Rodolfo Reyes, Álvaro Uguedo Vargas and Alex Saab. The Venezuelan government paid Group Grand Limited, a Mexican entity, for basic foods, which it supplied to CLAP. Maduro accused Ortega of working with the United States to damage his government.[296][297][298]

An April 2019 communication from the United States Department of State highlighted a 2017 National Assembly investigation finding that the government paid US$42 for food that cost under US$13 and that "Maduro's inner circle kept the difference, which totaled more than $200 million dollars in at least one case", adding that food boxes were "distributed in exchange for votes".[167] On 18 October 2018, Mexican prosecutors accused the Venezuelan government and Mexican individuals of buying poor-quality food products for CLAP and exporting them to Venezuela to double their value for sale.[299]

During the Venezuelan presidential crisis, Venezuelan National Assembly president Juan Guaidó said that the Maduro government had plans to steal for humanitarian purposes the products that entered the country, including plans to distribute these products through the government's food-distribution program CLAP.[300]

While Venezuelans were affected by hunger and shortages, Maduro and his government officials publicly shared images of themselves eating luxurious meals, images that were met with displeasure by Venezuelans.[301] Despite the majority of Venezuelans losing weight due to hunger, members of the Maduro's administration appeared to gain weight.[301]

In November 2017, while giving a lengthy, live cadena broadcast, Maduro, unaware he was still being filmed, pulled out an empanada from his desk and began eating it.[302] This occurred amid controversy over Maduro's gaining weight during the nationwide food and medicine shortage; with many on social media criticizing the publicly broadcast incident.[303][304]

In September 2018, Maduro ate at one of Salt Bae's luxury restaurants in Istanbul, where he and his wife were served a meat-heavy meal and offered a personalized shirt and box of cigars with Maduro's name engraved.[301][305] The Wall Street Journal reported that the incident received international criticism and left poor Venezuelans incensed.[252]

In December 2018, videos and pictures were leaked showing a glamorous Christmas party that included an expensive feast, including French wine, taking place in the seat of the pro-Maduro Supreme Tribunal of Justice. The images received considerable backlash from social networks, criticizing the costs of the party during the grave economic crisis in the country and the hypocrisy of Maduro's government.[306]

Corruption

In an investigative interview with Euzenando Prazeres de Azevedo, president of Constructora Odebrecht in Venezuela, the executive revealed how Odebrecht paid $35 million to fund Maduro's 2013 presidential campaign if Odebrecht projects would be prioritized in Venezuela.[307] Americo Mata, Maduro's campaign manager, initially asked for $50 million for Maduro, though the final $35 million was settled.[307][308]

Maduro was sentenced to 18 years and 3 months in prison on 15 August 2018 by the Supreme Tribunal of Justice of Venezuela in exile, with the exiled high court stating "there is enough evidence to establish the guilt ... [of] corruption and legitimation of capital".[309] The Organization of American States Secretary General, Luis Almagro, supported the verdict and asked for the Venezuelan National Assembly to recognize the ruling of the Supreme Tribunal in exile.[310]

The US State Department issued a fact sheet stating that Maduro's most serious corruption involved embezzlement in which "a European bank accepted exorbitant commissions to process approximately $2 billion in transactions related to Venezuelan third–party money launderers, shell companies, and complex financial products to siphon off funds from PdVSA".[167] The State Department also alleges that Maduro expelled authorized foreign companies from the mining sector to allow officials to exploit Venezuela's resources for their own gain, using unregulated miners under the control of Venezuela's armed forces.[167]

Sanctions

Thirteen government officials were sanctioned by the United States Department of Treasury due to their involvement with the 2017 Venezuelan Constituent Assembly election.[311] Two months later, the Canadian government sanctioned members of the Maduro government, including Maduro, preventing Canadian nationals from participating in property and financial deals with him due to the rupture of Venezuela's constitutional order.[312][313]

After the Constituent Assembly election, the United States sanctioned Maduro on 31 July 2017, making him the fourth foreign head of state to be sanctioned by the United States after Bashar al-Assad of Syria, Kim Jong Un of North Korea and Robert Mugabe of Zimbabwe.[314] Secretary of the Treasury Steven Mnuchin stating "Maduro is a dictator who disregards the will of the Venezuelan people".[90] Maduro fired back at the sanctions during his victory speech saying "I don't obey imperial orders. I'm against the Ku Klux Klan that governs the White House, and I'm proud to feel that way."[314]

In March 2018, Maduro was sanctioned by the Panamanian government for his alleged involvement with "money laundering, financing of terrorism and financing the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction".[315]

Maduro is also banned from entering Colombia.[316] The Colombian government maintains a list of people banned from entering Colombia or subject to expulsion; as of January 2019, the list had 200 people with a "close relationship and support for the Nicolás Maduro regime".[317][316]

After the breakdown of the Barbados Agreements, he disqualified the pre-candidate Maria Corina Machado through the Supreme Court, similar to the official government.[مطلوب توضيح] After that, the US sanctions were reapplied under the Biden administration.[318][319][320]

In September 2024, an Argentine federal court issued an arrest warrant against Maduro and several other Venezuelan officials for crimes against humanity.[321]

اعتقاله ونقله للولايات المتحدة

بحسب صحيفة التليگراف البريطانية، في نهاية أكتوبر 2025، اجتمع وفد أمريكي في العاصمة القطرية الدوحة مع وفد من النظام الڤنزويلي الحاكم لبحث مستقبل البلاد. لم يتضمن الوفد الڤنزويلي الرئيس نيكولاس مادورو، لكن كانت نائبته دلسي رودريگيز على رأس الوفد، إلى جانب شقيقها خورخى. وأشارت الصحيفة إلى أن أمير قطري من العائلة المالكة لعب دور الوساطة بين النظام الڤنزويلي والرئيس الأمريكي دونالد ترمپ. وذكرت الصحيفة البريطانية بتقرير سابق لصحيفة ميامي هرالد صادر في أكتوبر 2025، أشارت فيه إلى أن رودريگيز تواصلت مع واشنطن وقدّمت نفسها بوصفها بديلاً "أكثر قبولاً" من مادورو. وقد عزز هذا اللقاء الشكوك حول أن إزاحة مادورو لم تكن سوى "عملية من الداخل"، خُطط لها للإبقاء على رئيس في السلطة قادر على إدارة مرحلة انتقالية من دون تفكيك الدولة بالكامل، وتجنب الفوضى وأعمال الشغب. عرضت رودريگيز ما سمته "بنظام مادوري بلا مادورو"، أي "نسخة مخففة من النظام القائم".[322] وكان فرانسيسكو سانتوس كالديرون، نائب الرئيس الكولومبي السابق، قد قال: "أنا على يقين مطلق بأن دلسي رودريگيز هي من سلمته. عندما تجمع كل المعلومات المتوافرة لدينا، يتضح أن ما جرى كان عملية تسليم متعمّدة". واعتبرت التليگراف أن رودريگيز، مرشحة مثالية للتعاون مع إدارة ترمپ. تربط رودريگيز "علاقة وثيقة" بعدد من أفراد العائلة الحاكمة في قطر، كما أنها تخفي جزءاً من أصولها المالية في البلاد، "ما جعل الدوحة خياراً طبيعياً للقيام بدور الوسيط بينها وبين واشنطن".

في تمام الساعة 5:21 صباحاً بالتوقيت المحلي الڤنزويلي، نشر الرئيس الأمريكي دونالد ترمپ على موقع منصة تروث سوشيال أن الرئيس الڤنزويلي نيكولاس مادورو وزوجته سيليا فلورس قد أُعتقلا ونُقلا جواً خارج البلاد.[323][324] بحسب وزير الخارجية ماركو روبيو، فقد أُعتقل مادورو وسيواجه اتهامات جنائية في الولايات المتحدة.[214] أكدت نائبة الرئيس الڤنزويلي دلسي رودريگيز أن مادورو وزوجته مفقودان وطالبت "بإثبات أنهما على قيد الحياة".[213][325][213]

بحسب سي بي إس نيوز، فإن العملية التي استهدفت مادورو نفذتها القوة دلتا.[326]

أفادت مصادر المعارضة الڤنزويلية في ڤنزويلا لسكاي نيوز أنهم يعتقدون أن القبض على مادورو كان بمثابة "خروج تفاوضي" مع الولايات المتحدة.[327] وبعد ساعات، أعلنت المدعية العامة الأمريكية پام بوندي أن محكمة منطقة جنوب نيويورك وجهت لمادورو وفلورس تهم تتعلق بالإرهاب المرتبط بالمخدرات.[328]

مُنحت نائبت الرئيس دلسي رودريگيز صلاحيات رئاسية بموجب المادة 233 من الدستور الڤنزويلي، والتي تنص على أن نائب الرئيس يتولى مهام الرئاسة في حالة شغور المنصب الرئاسي.[329] طالبت رودريگيز في البداية بإثبات أن مادورو لا يزال على قيد الحياة.[93]

في خضم الفوضى والارتباك المفاجئين اللذين أعقبا اختطاف الرئيس نيكولاس مادورو من قبل الولايات المتحدة، نشأ فراغ قصير في السلطة في ڤنزويلا. لكن بعد وقت قصير من قيام الجيش الأمريكي بشن غارات جوية على كراكاس ومناطق أخرى، أشار الرئيس الأمريكي دونالد ترمپ - في تجاهل مفاجئ لزعيمة المعارضة الڤنزويلية ماريا كورينا ماتشادو، التي حازت جائزة نوبل للسلام 2025 - إلى أن نائبة الرئيس دلسي رودريگيز، قد أدت اليمين الدستورية كرئيسة بالإنابة. ووصف الرئيس الأمريكي ماتشادو اليمينية - التي تقربت من ترمپ، خاصة بعد فوزها بجائزة نوبل في أكتوبر، وهو ما كان هو نفسه يتوق إليه وأهدته إياه - بأنها لا تحظى بالدعم الكافي أو "الاحترام" لتكون زعيمة ڤنزويلا.[330]

قال ترمپ إن رودريگيز تحدثت مع وزير الخارجية الأمريكي ماركو روبيو وكانت "مستعدة بشكل أساسي للقيام بما نعتقد أنه ضروري لجعل ڤنزويلا عظيمة مرة أخرى". وأضاف ترمپ : "أعتقد أنها كانت كريمة للغاية. لا يمكننا المخاطرة بتولي شخص آخر زمام الأمور في ڤنزويلا لا يضع مصلحة الشعب الڤنزويلي في اعتباره".

وبعد ثلاثة أيام فقط من اعتقال مادورو، دعت رودريگيز الحكومة الأمريكية إلى "العمل معا لوضع أجندة للتعاون"، وذلك في بيان نشرته على وسائل التواصل الاجتماعي اتسم بنبرة تصالحية. وقالت إن ڤنزويلا "تطمح إلى العيش دون تهديدات خارجية"، وإنها ترغب في إعطاء الأولوية لبناء علاقات متوازنة وقائمة على الاحترام مع الولايات المتحدة.

Public opinion

In October 2013, Maduro's approval rating stood between 45% and 50% with Reuters stating that it was possibly due to Hugo Chávez's endorsement.[332] One year later in October 2014, Maduro's approval rating was at 24.5% according to pollster Datanálisis.[333] In November 2014, Datanálisis polls indicated that more than 66% of Venezuelans believed that Maduro should not finish his six-year term, with government supporters representing more than 25% of those believing that Maduro should resign.[334] In March and April 2015, Maduro saw a small increase in approval after initiating a campaign of anti-US rhetoric following the sanctioning of seven officials accused by the United States of participating in human rights violations.[224][225]

During a recall movement gathered from late-October through November 2016, a poll by Venebarómetro found that "88% of 'likely' voters in a recall would choose to oust Maduro."[335] Among similar polls, Hercon concluded that up to 81.3% of voters responded being willing to recall Maduro,[336] Meganálisis that up to 78.3% of respondents disagreed that Maduro continued governing,[337] and Datanálisis that 75% of Venezuelans considered that Maduro should be recalled.[338]

In September 2018, Meganálisis polls found that 84.6% of Venezuelans surveyed wanted Maduro and his government to be removed from power.[339] Following the suspension of the recall movement, a Venebarómetro poll found that 61.4% found that Maduro had become a dictator,[340] while in a poll taken by Keller and Associates 63% of those questioned thought that Maduro was a dictator.[341]

Before the 2018 presidential elections, a Datanálisis poll indicated that 16.7% of voters would vote for Maduro as candidate, compared to 27.6% and 17.1% of voters that would choose rival candidates Henri Falcón and Javier Bertucci, respectively.[342]

During the presidential crisis, The Wall Street Journal reported that barrios were turning against Maduro in "a shift born of economic misery and police violence".[252] Surveys between 30 January and 1 February 2019 by Meganálisis recorded that 4.1% of Venezuelans recognized Maduro as president, 11.2% were undecided, and 84.6% of respondents recognized Guaidó as interim president. The study of 1,030 Venezuelans was conducted in 16 states and 32 cities.[343]

A separate pollster, Hinterlaces, ran a poll from 21 January to 2 February 2019 that found that 57% of Venezuelans recognized Maduro as the legitimate president of Venezuela, 32% recognized Guaidó, and 11% were unsure.[344] By 4 March 2019, a Datanálisis poll found Guaidó's approval at 61%, and Maduro's at all-time low of 14%, with Guaidó win 77% in a theoretical election with Maduro, who received 23% of support.[331] Datanálisis found that, among the poorest 20% of Venezuelans, Maduro's support had fallen to 18% in February 2019 from 40% two years earlier.[252]

In a May 2019 analysis, José Briceño-Ruiz, based on the Meganalisis poll and other trends, said that Maduro was "extremely unpopular".[345]

In February 2023, a year before the 2024 presidential elections, a Datincorp poll concluded that 15.69% of voters would vote for Maduro as a candidate, in contrast to 16.86% that would vote for opposition candidate María Corina Machado.[346]

In popular culture

- Maduro was parodied in the animated web series Isla Presidencial, along with most of the other Latin American leaders, portrayed as a man of limited intelligence, twisted speech, and capable of talking with birds, the latter being a reference to a comment made by Maduro during the 2013 presidential elections, when he said that the late Chávez had reincarnated in a little bird and talked to him to bless his candidacy.[347]

- The 2020 revival of the Animaniacs series has featured Maduro, mocking him and the hyperinflation in Venezuela.[348][349]

- Several documentaries that discuss the Bolivarian Revolution and the Crisis in Venezuela, including In the Shadow of the Revolution,[350] Chavismo: The Plague of the 21st Century,[351] El pueblo soy yo,[352] and A La Calle,[353] depict Maduro as well.

Awards and honours

Revoked and returned awards and honours.

| Awards and orders | Country | Date | Place | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Order of the Liberator | 19 April 2013 | Caracas, Venezuela | Highest decoration of Venezuela, given to every president.[354] | ||

| Order of the Liberator General San Martín (Revoked) | 8 May 2013 | Buenos Aires, Argentina | Highest decoration of Argentina awarded by political ally President Cristina Fernández de Kirchner. Revoked on 11 August 2017 by President Mauricio Macri for human rights violations.[355][356] | ||

| Order of the Condor of the Andes | 26 May 2013 | La Paz, Bolivia | Highest decoration of Bolivia.[357] | ||

| Bicentenary Order of the Admirable Campaign | 15 June 2013 | Trujillo, Venezuela | Venezuelan order.[358] | ||

| Star of Palestine | 16 May 2014 | Caracas, Venezuela | Highest decoration of Palestine.[359] | ||

| Order of Augusto César Sandino | 17 March 2015 | Managua, Nicaragua | Highest decoration of Nicaragua.[360] | ||

| Order of José Martí | 18 March 2016 | La Habana, Cuba | Cuban order.[361] | ||

| Order of Francisco Morazán | 28 January 2024 | Tegucigalpa, Honduras | Highest decoration of Honduras.[362] | ||

Others

- In 2014, Maduro was named as one of TIME magazine's 100 Most Influential People. In the article, it explained that whether or not Venezuela collapses "now depends on Maduro", saying it also depends on whether Maduro "can step out of the shadow of his pugnacious predecessor and compromise with his opponents".[363]

- In 2016, the Reporters Without Borders (RSF) Top 35 Predators of Press Freedom list placed Maduro as a "predator" to press freedom in Venezuela, with RSF noting his method of "carefully orchestrated censorship and economic asphyxiation" toward media organizations.[364][365]

- In 2016, the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP), an international non-governmental organization that investigates crime and corruption, gave President Maduro the Person of the Year Award that "recognizes the individual who has done the most in the world to advance organized criminal activity and corruption". The OCCRP stated that they "chose Maduro for the global award on the strength of his corrupt and oppressive reign, so rife with mismanagement that citizens of his oil-rich nation are literally starving and begging for medicines" and that Maduro and his family steal millions of dollars from government coffers to fund patronage that maintains President Maduro's power in Venezuela. The group also explains how Maduro had overruled the legislative branch filled with opposition politicians, repressed citizen protests and had relatives involved in drug trafficking.[366]

Elections

2013 presidential campaign

Maduro won the second presidential election after the death of Hugo Chávez, with 50.61% of the votes against the opposition's candidate Henrique Capriles Radonski who had 49.12% of the votes.[367] The Democratic Unity Roundtable contested his election as fraud and as a violation of the constitution. However, the Supreme Court of Venezuela ruled that under Venezuela's Constitution, Maduro is the legitimate president and was invested as such by the Venezuelan National Assembly (Asamblea Nacional).[368]

2018 presidential campaign

Maduro was declared as the winner of the 2018 election with 67.8% of the vote. The result was denounced as fraudulent by most neighboring countries, including Argentina, Peña Nieto's Mexico, Chile, Colombia, Brazil, Canada and the United States,[369][370] as well as organizations such as the European Union,[371][372] and the Organization of American States, but recognized as legitimate by other neighboring countries such as López Obrador's Mexico,[373] Bolivia,[374] Cuba,[375] Suriname,[376] Nicaragua[377] and some other ALBA countries,[378][379] along with South Africa,[380] China,[381] Russia,[382] North Korea,[383] and Turkey.[384]

حملة الانتخابات الرئاسية 2024

Maduro ran for a third consecutive term, while González represented the Unitary Platform (إسپانية: Plataforma Unitaria Democrática; PUD), the main opposition political alliance. In June 2023, the Venezuelan government had barred leading candidate María Corina Machado from participating.[385][386] This move was regarded by the opposition as a violation of political human rights and was condemned by international bodies such as the Organization of American States (OAS),[387] the European Union,[388] and Human Rights Watch,[389] as well as numerous countries.[390]