تيودور روزڤلت

| تيودور روزڤلت، الابن Theodore Roosevelt, Jr. | |

|---|---|

| |

| رئيس الولايات المتحدة رقم 26 | |

| في المنصب 14 سبتمبر، 1901 – 4 مارس، 1909 | |

| نائب الرئيس | لا أحد (1901–1905)،[1] تشارلز فيربانكس (1905–1909) |

| سبقه | وليام مكينلي |

| خلفه | وليام هوارد تافت |

| نائب رئيس الولايات المتحدة رقم 25 | |

| في المنصب 4 مارس، 1901 – 14 سبتمبر، 1901 | |

| الرئيس | وليام مكينلي |

| سبقه | گارت هوبارت (حتى 1899) |

| خلفه | تشارلز فيربانكس (من 1905) |

| حاكم نيويورك رقم 36 | |

| في المنصب 1 يناير، 1899 – 31 ديسمبر، 1900 | |

| Lieutenant | تيموثي ل. وودروف |

| سبقه | فرانك بلاك |

| خلفه | بنجامين أودل، الأصغر |

| تفاصيل شخصية | |

| وُلِد | أكتوبر 27, 1858 مدينة نيويورك |

| توفي | يناير 6, 1919 (aged 60) اويستر باي، نيويورك |

| الحزب | جمهوري |

| الجامعة الأم | كلية حقوق كلومبيا - تركها؛ كلية هارڤارد |

| المهنة | متعدد المواهب، مؤلف، مؤرخ، ناشط الحفاظ على الطبيعة، موظف عمومي |

| الدين | الكنيسة المصلحة الهولندية |

| التوقيع | |

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

حاكم نيويورك رقم 33

نائب رئيس الولايات المتحدة رقم 25

رئيس الولايات المتحدة رقم 26

العهدة الأولى

العهدة الثانية

بعد الرئاسة

|

||

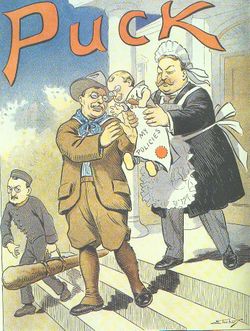

ثيودور روزفلت، الابن (Theodore "T.R." Roosevelt, Jr.؛ /ˈroʊzəvɛlt/ ROH-zə-velt)[2] (27 أكتوبر 1858 - 6 يناير 1919)، كان مؤلف، عالم طبيعة، مستكشف، مؤرخ، وسياسي أمريكي شغل منصب رئيس الولايات المتحدة رقم26. كان زعيم الحزب الجمهوري ومؤسس الحزب التقدمي. اشتهر بشخصيته المندفعة، مدى اهتماماته وانجازاته، وزعامته للحركة التقدمية، بالإضافة لتميزه بشخصية "رعاة البقر" والذكورية القوية.[3] وُلد لعائلة ثرية في مدينة نيويورك، وكان روزڤلت طفلاً مريضاً يعاني من الربو. ليتغلب على ضعفه البدني، أقبل على الحياة الشاقة. تلقى تعليمه في المنزل وأصبح طالب متحمس لدراسة الطبيعة. إلتحق بجامعة هارڤرد حيث درس علم الأحياء، وتطور اهتمامه بالموضوعات البحرية. دخل السياسة في المجلس التشريعي لولاية نيويورك، وصمم على أن يصبح عضو في الطبقة الحاكمة. عام 1881، السنة التي ترك فيها هارڤرد، كان قد انتخب في جمعية ولاية نيويورك، حيث أصبح زعيم الفصيل الإصلاحي بالحزب الجمهوري. كتابه الحرب البحرية 1812 (1882) جعل منه كاتب ومؤرخ مطلع.

عندما توفت زوجته الأولى أليس بعد يومين من ولادتها في فبراير 1884، كان حزيناً ويائساً؛ ترك السياسة مؤقتاً وأصبح مربي ماشية في داكوتا. عندما هلكت مواشيه بسبب العواصف الثلجية عاد إلى الحياة السياسية بمدينة نيويورك، وخاض وخسر في السباق الانتخابي على منصب العمدة. في تسعينيات القرن التاسع عشر تولى منصب مفوض في شرطة المدينة. بحلول 1897 كان روزڤلت يعمل في وزارة البحرية. دعا للحرب ضد إسپانيا وعندما نشبت الحرب الإسپانية الأمريكية عام 1898 تلقى مساعدة من فوج الفرسان المتطوعين الشهير، مزيج من الشرقيين الأثرياء ورعاة البقر الغربيين. حصل على شهرة وطنية لشجاعته في معركة كوبا، بعدها عاد لينتخب كحاكم لنيويورك. كان مرشح الحزب الجمهوري لمنصب نائب الرئيس مع وليام مكنلي، حيث قام بحملة انتخابية ناجحة ضد الراديكالية ومن أجل الازدهار، الشرف الوطني، الامپريالية (فيما يخص الفلپين)، التعريفات الجمركية المرتفعة ومعيار الذهب. أصبح روزڤلت رئيساً بعدم اغتيال مكينلي. حاول نقل الحزب الجمهوري إلى التقدمية، وشملت محاولاته خرق الثقة والتنظيم المتزايد للأعمال. في نوفمبر 1904 اعيد انتخابه بعد فوزه على منافسه الديمقراطي المحافظ ألتون بروكس پاركر. أطلق روزڤلت على سياساته الداخلية "الصفقة العادلة Square Deal"، واعداً بصفقة عادلة مع المواطن المتوسط بينما سيعمل على تفكيك الشركات الاحتكارية، الضغط من أجل تخفيض أسعار السكك الحديدية، وضمان الطعام الجيد والأدوية. كان أول رئيس يتحدث عن الحفاظ، وقام بتوسعات كبيرة في نظام المنتزهات والغابات الوطنية. بحلول عام 1907 كان قد طرح المزيد من الاصلاحات الراديكالية، والتي قوبلت بالرفض من قبل الجمهوريين المحافظين في الكونگرس. سياسته الخارجية ركزت على الكاريبي، حيث قام ببناء قناة پنما وحما نهجها. لم يكن هناك حروب، لكن شعاره، "تحدث بنعومة واحمل عصا غليظة" تم التأكيد عليه بإرسال الأسطول الأبيض الكبير في جولة عالمية. تفاوض على انهاء الحرب الروسية اليابانية، ومن أجلها حاز جائزة نوبل للسلام.

في نهاية مدته الرئاسية الثانية، دعم روزڤلت صديقه المقرب وليام هاورد تافت للحصول على ترشيح الحزب الجمهوري في 1908. بعد تركه المنصب، قام بجولة في أفريقيا وأوروپا، وفي أثناء عودته عام 1910 اختلف مع الرئيس تافت حول قضايا التقدمية وأخرى شخصية. في انتخابات 1912 حاول روزڤلت لكنه فشل في منع اعادة ترشيح تافت. بعد ذلك أسس الحزب التقدمي ("Bull Moose") الذي نادى بالاصلاحات التقدمية، تقسيم التصويت الجمهوري. سمح هذا للديمقراطي وودرو ويلسون بالفوز بالبيت الأبيض والكونگرس، بينما فاز محافظي تافت بالسيطرة على الحزب الجمهوري لعقود. بعدها قاد روزڤلت بعثة كبرى لغابات الأمازون وأصيب بالعديد من الأمراض. من 1914 حتى 1917 روج من أجل دخول الولايات المتحدة الحرب العالمية الأولى، وتصالح مع زعامة الحزب الجمهوري. كان يعتبر المرشح الأوفر حظاً للحزب الجمهوري في انتخابات 1920، لكن صحته تدهورت وتوفى عام 1919. دأب العلماء على وضع روزڤلت على أنه واحداً من أعظم رؤساء الولايات المتحدة.[4] نحت وجهه في جبل رشموند موضوع بجانب جورج واشنطن، توماس جفرسون وابراهام لينكولن.[5]

طفولته، تعليمه، وحياته الخاصة

وُلد روزڤلت في مدينة نيويورك. بدأ حياته ضابطاً بشرطة مدينة نيويورك. وفي عام 1897، عيَّنه الرئيس وليام مكينلي مساعدًا لوزير البحرية، حيث عمل روزڤلت على تقوية البحرية. وفي عام 1898، شارك روزڤلت في الحرب الكوبية، مما أكسبه شهرة واسعة ساعدته على الفوز بانتخابات عام 1898 حاكمًا لولاية نيويورك. وأثناء توليه منصب حاكم ولاية نيويورك بدأ روزڤلت ما عُرف بدبلوماسية العصا الغليظة التي استمرت فيما بعد خلال مدة رئاسته.

تأثر شباب روزڤلت إلى حد كبير بحالته الصحية السيئة والربو المنهك. وقد تعرض مرارًا وتكرارًا لنوبات ربو ليلية مفاجئة تسببت في تجربته للتعرض للاختناق حتى الموت، الأمر الذي أرعب ثيودور ووالديه. ولم يكن لدى الأطباء علاج.[6] ومع ذلك، كان نشيطًا وفضوليًا بشكل مؤذ.[7]

بدأ اهتمامه الدائم بعلم الحيوان في سن السابعة عندما رأى خلداً ميتاً في السوق المحلي؛ بعد الحصول على رأس الخلد، شكل روزڤلت واثنين من أبناء عمومته ما أطلقوا عليه اسم "متحف روزڤلت للتاريخ الطبيعي". بعد أن تعلم أساسيات التحنيط، ملأ متحفه المؤقت بالحيوانات التي قتلها أو اصطادها؛ ثم قام بدراسة الحيوانات وأعدها للعرض. وفي سن التاسعة، سجل ملاحظته للحشرات في ورقة بحثية بعنوان "التاريخ الطبيعي للحشرات".[8]

تأثر روزڤلت بوالده بشكل كبير. كان والده قائدا بارزا في الشؤون الثقافية في نيويورك. ساعد في تأسيس متحف متروپوليتان للفنون، وكان نشطًا بشكل خاص في حشد الدعم للاتحاد أثناء الحرب الأهلية الأمريكية، على الرغم من أن أصهاره كان من بينهم قادة الكونفدرالية. قال روزڤلت: "كان والدي، ثيودور روزڤلت، أفضل رجل عرفته على الإطلاق. لقد جمع بين القوة والشجاعة واللطف والحنان وعدم الأنانية الكبيرة. ولم يكن ليتسامح معنا الأطفال في سلوك الأنانية أو القسوة أو الكسل أو الجبن أو الكذب".

شكلت الرحلات العائلية إلى الخارج، بما في ذلك جولات أوروپا عامي 1869 و1870، ومصر عام 1872، منظوره العالمي.[9] أثناء التنزه مع عائلته في الألپ عام 1869، وجد روزڤلت أنه يستطيع مواكبة والده. لقد اكتشف الفوائد الكبيرة للمجهود البدني لتقليل إصابته بالربو وتعزيز معنوياته.[10] بدأ روزڤلت نظاماً مكثفاً من التمارين الرياضية. بعد أن تعرض لمضايقات من قبل صبيين أكبر منه في رحلة تخييم، وجد مدربًا للملاكمة ليعلمه القتال وتقوية جسده.[11][12]

وهو في السادسة من عمره، شهد روزڤ موكب جنازة ابراهام لنكن من قصر جده كورنليوس في ميدان الاتحاد، مدينة نيويورك، حيث كان يصور الموكب من النافذة مع شقيقه إليوت، كما أكدت زوجته الثانية إديث، التي كانت حاضرة أيضًا.[13]

التعليم

تلقى روزڤلت تعليمه في المنزل، في الغالب بواسطة والديه ومدرسين خاصين.[14] يزعم كاتب السيرة الذاتية و. براندز بأن "العيب الأكثر وضوحًا في تعليمه بالمنزل هو التغطية غير المتكافئة لمختلف مجالات المعرفة الإنسانية".[15]

كان روزڤلت قوياً في الجغرافيا، لامعاً في التاريخ، وعلم الأحياء، والفرنسية، والألمانية. لكنه عانى في الرياضيات واللغات الكلاسيكية. وعندما دخل كلية هارڤرد في 27 سبتمبر 1876، نصحه والده: "اعتني بأخلاقك أولاً، ثم بصحتك، وأخيراً بدراستك".[16] أدت وفاة والده المفاجئة في 9 فبراير 1878 إلى تدمير روزڤلت، لكنه تعافى في النهاية وضاعف أنشطته.[17]

كان والده، وهو من مشيخي المتدين، يقود الأسرة بانتظام في الصلاة. أثناء وجوده في هارڤرد، قام ثيودور الشاب بتقليده من خلال التدريس لأكثر من ثلاث سنوات في مدرسة الأحد بكنيسة المسيح في كمبردج. عندما أصر قس كنيسة المسيح، التي كانت كنيسة أسقفية، في النهاية على أن يصبح أسقفيًا لمواصلة التدريس في مدرسة الأحد، رفض روزڤلت، وبدأ بدلاً من ذلك تدريس فصل تبشيري في أحد أحياء كمبردج الفقيرة.[18]

كان أداؤه جيدًا في دروس العلوم والفلسفة والبلاغة، لكنه استمر في النضال في اللاتينية واليونانية. درس روزڤلت علم الأحياء باهتمام وكان بالفعل عالم طبيعة بارعاً وعالم طيور ناشراً. كان يقرأ بشكل مذهل بذاكرة شبه فوتوغرافية.[19] عندما كان في هارڤرد، شارك روزڤلت في رياضة التجديف والملاكمة؛ ووصل إلى المركز الثاني في بطولة الملاكمة الجماعية.[20] كان روزڤلت عضواً في جمعية فاي بيتا كاپا الثقافية (نادي فلاي لاحقاً)، أخوية دلتا كاپا إپسيلون، ونادي پروسليان المرموق؛ كما كان رئيس تحرير مجلة محامي هارڤرد. عام 1800، تخرج روزڤلت من هارڤد حاصلاً على بكالريوس الآداب بامتياز مع مرتبة الشرف. ويقول كاتب السيرة الذاتية هنري پرينگل:

كان روزڤلت، وهو يحاول تحليل مسيرته الجامعية وتقييم الفوائد التي حصل عليها، يشعر أنه لم يحصل على الكثير من هارڤرد. لقد كان مكتئبًا بسبب المعالجة الشكلية للعديد من الموضوعات، بسبب الجمود، والاهتمام بالتفاصيل الدقيقة التي كانت مهمة في حد ذاتها، لكنها بطريقة ما لم تكن مرتبطة أبدًا بالكل.[21]

بعد وفاة والده، ورث روزڤلت 65.000 دولار (equivalent to $1٬565٬379 in 2022)، الثروة التي تضمن له معيشة لائقة بقية حياته.[22] تخلى روزڤلت عن خطته السابقة لدراسة العلوم الطبيعية وقرر بدلاً من ذلك الالتحاق بكلية حقوق كلومبيا، وعاد إلى منزل عائلته في مدينة نيويورك. على الرغم من أن روزڤلت كان طالبًا متمكنًا في القانون، إلا أنه غالبًا ما وجد القانون غير عقلاني. أمضى معظم وقته في تأليف كتاب عن حرب 1812.[23]

عازمًا على دخول الحياة السياسية، بدأ روزڤلت في حضور الاجتماعات في مورتون هول، المقر الرئيسي شارع 59 في المنطقة الجمعية الجمهورية رقم 21 بمدينة نيويورك. على الرغم من أن والد روزڤلت كان عضوًا بارزًا في الحزب الجمهوري، إلا أن روزڤلت الابن قام باختيار مهني غير تقليدي لشخص من طبقته، حيث امتنع معظم أقران روزڤلت عن أن يشاركوا بشكل وثيق في السياسة. وجد روزڤلت حلفاء في الحزب الجمهوري المحلي وهزم عضو مجلس النواب الجمهوري الحالي المرتبط بالآلة السياسية السنتور روسكو كونكلنگ. بعد فوزه في الانتخابات، قرر روزڤلت ترك كلية الحقوق، وقال لاحقًا: "كنت أنوي أن أكون واحدًا من الطبقة الحاكمة".[24]

التاريخ والاستراتيجية البحرية

أثناء وجوده في هارڤرد، بدأ روزڤلت دراسة ممنهجة للدور الذي لعبته البحرية الأمريكية في حرب 1812.[25][26] وبمساعدة اثنين من أعمامه، قام بتدقيق المواد الأصلية والسجلات الرسمية للبحرية الأمريكية، وفي نهاية المطاف نشر عام 1882 كتاب الحرب البحرية 1812. احتوى الكتاب على رسومات لمناورات السفن الفردية والمشتركة، ورسوم بيانية توضح الاختلافات في رمي الأوزان الحديدية للمدفع بين القوات المتنافسة، وتحليل الاختلافات والتشابهات بين القيادة البريطانية والأمريكية وصولاً إلى مستوى السفينة إلى السفينة. عند نشره، أشيد بالكتاب لمنهجم العلمي وأسلوبه، وظل دراسة قياسية للحرب.[27]

مع نشر كتاب تأثير القوة البحرية على التاريخ عام 1890، على الفور تم الترحيب بالكابتن البحري ألفرد ثاير ماهان باعتباره المنظر البحري المتميز في العالم من قبل زعماء أوروپا. أولى روزڤلت اهتمامًا وثيقًا للغاية بتأكيد ماهان على أن الدولة التي تمتلك أقوى أسطول في العالم هي وحدها القادرة على السيطرة على محيطات العالم، وممارسة دبلوماسيتها على أكمل وجه، والدفاع عن حدودها.[28][29] قام روزڤلت بدمج أفكار ماهان في آرائه حول الإستراتيجية البحرية لما تبقى من حياته المهنية.[30][31]

زواجه الأول

عام 1880، تزوج روزڤلت من نجمة المجتمع أليس هاثاواي لي.[32][33] وُلدت ابنتهما أليس في 12 فبراير 1884. بعد يومين توفيت الأم جراء القصور الكلوي الذي لم يتم تشخيصه بسبب الحمل. في مذكراته، كتب روزڤلت علامة "X" كبيرة على الصفحة ثم "لقد انطفأ النور من حياتي". توفيت والدته، مارثا، بسبب حمى التيفوئيد قبل إحدى عشرة ساعة في الساعة 3:00 صباحًا، في نفس المنزل الواقع في شارع 57 بمانهاتن. في ذهول، ترك روزڤلت الطفلة أليس في رعاية أخته بامي وهو حزين؛ تولى حضانة أليس عندما بلغت الثالثة من عمرها.[34]

بعد وفاة زوجته ووالدته، ركز روزڤلت على عمله، وتحديدًا من خلال إعادة تنشيط التحقيق التشريعي في فساد حكومة مدينة نيويورك، والذي نشأ من مشروع قانون متزامن يقترح أن تكون السلطة مركزية في يد مكتب العمدة.[35] طوال حياته، نادراً ما تحدث عن زوجته أليس ولم يكتب عنها في سيرته الذاتية.[36]

سيرته السياسية المبكرة

النائب الولائي

كان روزڤلت عضواً في مجلس نواب ولاية نيويورك في أعوام 1882، 1883، و1884.[37] على الفور بدأ روزڤلت في ترك بصمته في التعامل مع قضايا فساد الشركات على وجه التحديد.[37] لقد منع جهدًا فاسدًا للممول جاي گولد لخفض ضرائبه. كشف روزڤلت أيضًا عن التواطؤ المشتبه به بين گولد والقاضي ثيودوريك وستبروك ودافع عن إجراء تحقيق وحصل على الموافقة عليه، بهدف عزل القاضي. على الرغم من أن لجنة التحقيق رفضت الاتهام المقترح، إلا أن روزڤلت كشف الفساد المحتمل في ألباني وحاز سمعة سياسية رفيعة وإيجابية في العديد من منشورات نيويورك.[38]

ساعدت جهود روزڤلت في مكافحة الفساد على الفوز بإعادة انتخابه عام 1882 بهامش أكبر من اثنين إلى واحد، وهو إنجاز أصبح أكثر إثارة للإعجاب بعد فوز المرشح الديمقراطي لمنصب حاكم الولاية گروڤر كليڤلاند في دائرة روزڤلت.[39]

مع وجود ستالوارت الجمهوري بزعامة كونكلنگ في حالة من الفوضى بعد اغتيال الرئيس جيمس گارفيلد، فاز روزڤلت في انتخابات مجلس ولاية نيويورك كزعيم للحزب الجمهوري. تحالف مع الحاكم كليڤلاند لإنجاح إقرار مشروع قانون إصلاحات الخدمة المدنية.[40] فاز روزڤلت بإعادة انتخابه للمرة الثانية وسعى لمنصب رئيس مجلس ولاية نيويورك، لكن تيتوس شيرد فاز بالمنصب بأغلبية 41 صوتًا مقابل 29 صوتًا لتجمع الحزب الجمهوري.[41][42] في ولايته الأخيرة، شغل روزڤلت منصب رئيس لجنة شؤون المدن، حيث كتب خلالها مشروعات قوانين أكثر من أي مشرع آخر.[43]

الانتخابات الرئاسية 1884

مع وجود العديد من المرشحين الرئاسيين الذين يمكن الاختيار منهم، دعم روزڤلت السيناتور جورج إدموندز من ڤرمونت، وهو مصلح حيادي. فضل الحزب الجمهوري بالولاية الرئيس الحالي، رئيس مدينة نيويورك تشستر آرثر، المعروف بتمريره قانون پندلتون لإصلاح الخدمة المدنية. ناضل روزڤلت بنجاح من أجل التأثير على مندوبي منهاتن في مؤتمر الولاية في يوتيكا. ثم سيطر على مؤتمر الولاية، وتفاوض طوال الليل وتغلب على أنصار آرثر وجيمس بلين؛ وبالتالي اكتسب سمعة وطنية باعتباره سياسيًا رئيسيًا في ولايته.[44]

حضر روزڤلت المؤتمر الوطني للحزب الجمهوري 1884 في شيكاغو وألقى خطابًا أقنع فيه المندوبين بترشيح الأمريكي-الأفريقي جون لينش، أحد مؤيدي إدموندز، كرئيساً مؤقتاً للمؤتمر. حارب روزڤلت إلى جانب إصلاحيي موگوومپ ضد بلين. ومع ذلك، حصل بلين على دعم من مندوبي آرثر وإدموندز، وفاز بالترشيح في الاقتراع الرابع. في لحظة حاسمة من حياته السياسية الناشئة، قاوم روزڤلت طلب زملائه الموگوومپ بالانسحاب من تأييد بلين. لقد تفاخر بنجاحه الصغير: "لقد حققنا انتصارًا في الحصول على مجموعة للتغلب على ترشح بلين لمنصب الرئيس المؤقت... للقيام بذلك يتطلب مزيجًا من المهارة والجرأة والطاقة... لجعل الفصائل المختلفة تنتصر. هيا بنا... نهزم العدو المشترك".[45] وقد تأثر أيضًا بالدعوة للتحدث أمام جمهور يبلغ عدده عشرة آلاف شخص، وهو أكبر حشد خاطبه حتى ذلك التاريخ. بعد أن تذوق السياسة الوطنية، شعر روزڤلت بطموح أقل للدعوة على مستوى الولاية؛ ثم تقاعد في "مزرعة تشيمني بوت" الجديدة الواقعة على نهر لتيل مزوري.[46] رفض روزڤلت الانضمام إلى الموگوومپ الآخرين في دعم گروڤر كليڤلاند، حاكم نيويورك والمرشح الديمقراطي في الانتخابات العامة. ناقش إيجابيات وسلبيات البقاء مخلصًا لصديقه السياسي هنري كابوت لودج. بعد فوز بلين بالترشيح، قال روزڤلت بلا مبالاة إنه سيقدم "دعمًا قويًا لأي ديمقراطي محترم". ونأى بنفسه عن الوعد قائلاً أن هذا التصريح ليس "للنشر".[47] عندما سأله أحد المراسلين عما إذا كان سيدعم بلين، أجاب روزڤلت: "هذا السؤال أرفض الإجابة عليه. هو موضوع لا يهمني التحدث عنه".[48] وفي النهاية، أدرك أنه يتعين عليه دعم بلين للحفاظ على دوره في الحزب الجمهوري، وقد فعل ذلك في بيان صحفي صدر في 19 يوليو.[49] بعد أن فقد دعم العديد من الإصلاحيين، قرر روزڤلت اعتزال الحياة السياسية والانتقال إلى داكوتا الشمالية.[50]

مربي مواشي في داكوتا

عام 1883 زار روزفلت إقليم داكوتا لأول مرة لاصطياد البايسون.[51]

مبتهجًا بنمط الحياة الغربي ومع ازدهار تجارة الماشية في المنطقة، استثمر روزڤلت 14000 دولار ($349٬200 في 2022) على أمل أن يصبح مربي ماشية ثري. وعلى مدى السنوات العديدة التالية، كان يتنقل بين منزله في نيويورك ومزرعته في داكوتا.[52]

في أعقاب الانتخابات الرئاسية الأمريكية 1884، بنى روزڤلت مزرعة إلكورن، والتي كانت على بعد 56 كم شمال بلدة ميدورا، داكوتا الشمالية المزدهرة. تعلم روزڤلت ركوب الخيل على الطريقة الغربية، واستخدام الحبل، والصيد على ضفاف نهر ليتل مزوري. على الرغم من أنه حصل على احترام رعاة البقر الأصليين، إلا أنهم لم يكونوا منبهرين بشكل مفرط. [53] ومع ذلك، فقد تماهى مع راعي التاريخ، وهو رجل قال أنه يمتلك " قليل من أخلاق الحليب والماء الضعيفة التي أعجب بها المحسنون الزائفون، لكنه يمتلك، إلى درجة عالية جدًا، الصفات الرجولية الصارمة التي لا تقدر بثمن بالنسبة للأمة.[54][55] أعاد توجيهه وبدأ الكتابة عن الحياة الحدودية للمجلات الوطنية. كما نشر ثلاثة كتب: رحلات صيد رجل المزرعة، حياة المزرعة ومسار الصيد، وصياد البرية.[56]

نجح روزڤلت في قيادة الجهود الرامية إلى تنظيم أصحاب المزارع هناك لمعالجة مشاكل الرعي الجائر وغيرها من الاهتمامات المشتركة، مما أدى إلى تشكيل جمعية ليتل مزوري ستوكمان. لقد شعر بأنه مضطر إلى تعزيز الحفاظ على البيئة وتمكن من تشكيل نادي بون أند كروكيت، الذي كان هدفه الأساسي الحفاظ على الطرائد الكبيرة وموائلها.[57] عام 1886، شغل روزڤلت منصب نائب الشريف في مقاطعة بلنگز، داكوتا الشمالية. في ذلك الوقت، قام هو واثنان من العاملين في المزرعة بمطاردة ثلاثة لصوص قوارب.[58]

قضت الولايات المتحدة شتاء 1886-1887 القاسي الذي قضى على قطيع الماشية الخاص برزوڤلت ومنافسيه وأكثر من نصف استثماره البالغ 80.000 دولار ($2.07 million في 2022). [59][60] أنهى مشروعاته في تربية الماشية وعاد إلى نيويورك، حيث نجا من التصنيف الضار للمثقف غير الفعال.[61]

الزواج الثاني

في 2 ديسمبر 1886، تزوج روزڤلت من صديقة طفولته إديث كرمت كارو.[62] شعر روزڤلت بالانزعاج الشديد لأن زواجه الثاني تم بسرعة كبيرة بعد وفاة زوجته الأولى، كما واجه مقاومة من أخواته.[63] ومع ذلك، تزوج الزوجان في سانت جورج، هانوڤر سكوير، لندن، إنگلترة.[64] أنجب الزوجان خمسة أنجال: ثيودور "تد" الثالث عام 1887، كرمت عام 1889، إثيل عام 1891، أرشيبالد عام 1894، وكوينتين عام 1897. كما ربيا أليس ابنة روزڤلت من زوجاه الأول، التي كانت دائماً ما تتشاجر مع زوجة أبيها.[65]

المؤرخ

العودة للحياة العامة

لدى عودة روزڤلت إلى نيويورك عام 1886، سارع القادة الجمهوريون إلى التواصل معه بشأن الترشح لمنصب عمدة مدينة نيويورك في انتخابات 1886.[66] قبل روزڤلت الترشح على الرغم من ضعف أمله في الفوز بالسباق ضد مرشح حزب العمال المتحد هنري جورج والمرشح الديمقراطي أبرام هيويت. قام روزڤلت بحملة شاقة للحصول على هذا المنصب، لكن هيويت فاز بنسبة 41% (90.552 صوتًا)، ليحصل على أصوات العديد من الجمهوريين الذين كانوا يخشون سياسات جورج المتطرفة.[67][68] حصل جورج على 31% (68110 أصوات)، وجاء روزڤلت في المركز الثالث بنسبة 27% (60435 صوتًا). خوفًا من أن لا تتعافى حياته السياسية أبدًا، حول روزڤلت انتباهه إلى كتابة فوز الغرب، وهو عمل تاريخي يتتبع حركة الأمريكيين غربًا. حقق الكتاب نجاحًا كبيرًا لروزڤلت، حيث حصل على تقييمات إيجابية وبيع العديد من [مطلوب توضيح] النسخ.[69]

مفوضية الخدمة المدنية

في الانتخابات الرئاسية 1888، قام روزڤلت بحملة انتخابية ناجحة، وخاصة في وسط الغرب، لصالح بنجامين هاريسون. الرئيس هاريسون عين روزڤلت في مفوضية الخدمة المدنية الأمريكية، حيث عمل حتى 1895، حارب بقوةspoilsmen وطالب إنفاذ قوانين الخدمة المدنية.[70] فيما بعد وصفتهنيويورك صن على أنه "محارب حماسي، لا يمكن إيقافه"[71] بالرغم من دعم روزڤلت لاعادة انتخاب هاريسون في الانتخابات الرئاسية 1892، إلا أن الفائز في النهاية، كان گروڤور كلڤلاند (ديمقراطي البوربون)، والذي أعاد تعيينه في نفس المنصب.[72] صديق روزڤلت المقرب وكاتب السيرة، جوسف بكلين بيشوپ، وصف هجومه على spoils system:

إن سياسة قلعة الغنائم نفسها، تلك القلعة المنيعة حتى الآن والتي كانت موجودة دون أن تهتز منذ تشييدها على الأساس الذي وضعها أندرو جاكسون، كانت تترنح نحو السقوط تحت هجمات هذا الشاب الجريء الذي لا يمكن كبته. كانت مشاعر الرئيس (هاريسون) (زميله في الحزب الجمهوري) - وليس هناك شك في أنه لم يكن لديه أي فكرة عندما عين روزڤت أنه سيثبت أنه ثور حقيقي في متجر صيني - رفض عزله وووقف إلى جانبه بقوة حتى نهاية فترة ولايته.[71]

رئيس شرطة مدينة نيويورك

عام 1894 أقنعت مجموعة من الجمهوريين الاصلاحيين روزڤلت بخوض انتخابات عمدة مدينة نيويورك مرة أخرى؛ كان رفضه يرجع في معظمه لمقاومة زوجته أن تخرج من المجموعة الاجتماعية بواشطن. لم يكد يرفض حتى أدرج أنها الفرصة الضائعة لتنشيط الحياة السياسية الخامدة. تراجع إلى داكوتا لفترة؛ وعبرت زوجته إديث عن أسفها لدورها في هذا القرار وتعهدت أن هذا لن يتكرر.[73]

في 1894، إلتقى روزڤلت جاكوب ريس، الصحفي المكراكر في جريدة إڤنينگ صن الذي كان أعين أغنياء نيويورك على الأوضاع المزرية لملايين المهاجرين الفقراء بكتب مثل كيف يعيش النصف الآخر. في السيرة الذاتية التي كتبها ريس، وصف تأثير كتابه على المفوض السياسي الجديد:

عندما قرأ روزڤلت كتابي، جاء... ولم يساعده أحد على الإطلاق كما فعل. لمدة عامين كنا أخوة في شارع مولبيري (المليئ بالجرائم مدينة نيويورك). عندما غادر كنت قد رأيت عصره الذهبي.. هناك القليل من السهولة التي يقودها ثيودور روزڤلت، كما اكتشفنا جميعًا. لقد اكتشف أن ذلك مخالف القانون الذي تنبأ بازدراء بأنه "سوف ينخرط في السياسة كما فعلوا جميعًا"، وعاش ليحترمه، على الرغم من أنه أقسم عليه، باعتباره أكثرهم قوة لمقاومة الجذب... وهذا ما جعل العصر ذهبياً، ولأول مرة ظهر هدف أخلاقي في الشارع. وفي ضوء ذلك تحول كل شيء.[74]

ابتكر روزڤلت عادة مشي الضباط في أخر الليل وفي الصباح الباكر للتأكد من أنهم على أهبة الاستعداد.[75] بذل جهداً منسقاً لإنفاذ قانون إغلاق الأحد بنيويورك؛ والذي وقف خلاله ضد رئيسه توم پلات وتامي هول - حيث قدم ملاحظة عن أن مفوضية الشرطة تم تشريعها للخروج من الوجود. اختار روزڤلت التأجيل بدلاً من الانفصال عن حزبه.[76] كحاكم لولاية نيويورك قبل أن يصبح نائباً للرئيس في مارس 1901، وقع روزڤلت لاحقاً قانون لاستبدال مفوضي الشرطة بمفوض شرطة واحد.[77]

بزوغه كشخصية وطنية

مساعد وزير البحرية

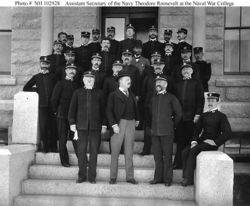

أثبت روزڤلت، من خلال أبحاثه وكتاباته، السحر مع التاريخ البحري؛ الرئيس وليام مكنلي، يزعم صديق روزڤلت المقرب عضو الكونگرس هنري كابوت لودج، عين روزڤلت كمساعد لوزير البحرية عام 1897.[78] كان وزير البحرية جون د. لونگ يهتم بالشكليات أكثر من المهام، وكان يعاني من مشكلات صحية، وترك القرارات الرئيسية لروزڤلت. انتهز روزڤلت الفرصة وبدأ في الضغط على الرئيس لفرض آرائه حول الأمن القومي فيما يخص الهادي والكاريبي. كان روزڤلت يصر بشكل خاص على أنه يمكن إخراج إسپانيا من كوبا، لتعزيز استقلال الأخيرة ولإظهار عزم الولايات المتحدة على إعادة تطبيق مبدا مونروا.[79] بعد عشرة أيام من انفجار السفينة الحربية مين في ميناء هاڤانا، كوبا، ترك الوزير المنصب وأصبح روزڤلت نائباً للوزير لأربع ساعات. أبرق روزڤلت للقوات البحرية في أنحاء العالم للاستعداد للحرب، أمر بتجهيز الذخيرة والإمدادات، جلب الخبراء وذهب للكونگرس يطلب منحه صلاحية تجنيد ما يريد من البحارة.[80] كان لروزڤلت دور فعال في إعداد البحرية للحرب الإسپانية الأمريكية.

في الانتخابات الرئاسية 1896، ساند روزڤلت الناطق بإسم مجلس النواب توماس براكت ريد للترشيح الجمهوري، إلا أن وليام مكنلي فاز بالترشيح وهزم وليام جننگز براين في الانتخابات العامة.[81] وقد عارض روزڤلت بقوة منصة براين المنادية بالفضة المجانية، ورأى أتباع براين كمتعصبين خطرين. وقد ألقى عدداً كبيراً من خطب الحملة الانتخابية لمكنلي.[82] بناءً على طلب من السناتور هنري كابوت لودج، قام الرئيس مكنلي عام 1897 بتعيين روزڤلت مساعداً لوزير الحربية.[83] كان وزير البحرية جون لونگ مهتمًا بالشكليات أكثر من الوظائف، وكان في حالة صحية سيئة، وترك العديد من القرارات الرئيسية لروزڤلت. متأثرًا بألفرد ثاير ماهان، دعا روزڤلت إلى تعزيز القوة البحرية للبلاد، ولا سيما بناء البوارج.[84] بدأ روزڤلت أيضًا الضغط على مكنلي بآرائه المتعلقة بالأمن القومي فيما يتعلق بالمحيط الهادئ ومنطقة البحر الكاريبي وكان مصراً بشكل خاص على طرد إسپانيا من كوبا.[85] كان لروزڤلت عقلاً تحليلياً، حتى وهو يتحرق شوقاً للحرب. وقد أوضح أولوياته لأحد مخططي البحرية في وقت لاحق عام 1897:

أرى الحرب مع إسپانيا من وجهتي نظر: الأولى، أنها الصواب من الناحية الإنسانية ومن ناحية المصلحة الشخصية بالتدخل نيابة عن الكوبيين، والتقدم بخطوة تجاه إنهاء تحرير أمريكا من الهيمنة الأوروپية، الثانية، المكسب الذي يعم على شعبنا بمنحم شيئاً يفكرون فيه وهو ليس مكسباً مادياً، وخاصة أن المكسب كان لصالح قواتنا العسكرية بمحاولة القوات البحرية والجيش القيام بتدريب عملي.[86]

في 15 فبراير 1898، انفجر الطراد المدرع مين في ميناء هاڤانا، كنبا، مما أسفر عن مقتل المئات من أفراد الطاقم. وبينما ألقى روزڤلت والعديد من الأمريكيين الآخرين باللوم على إسڤانيا في الانفجار، سعى مكنلي إلى حل دبلوماسي.[87] بدون موافقة لونگ أو مكنلي، أرسل روزڤلت أوامر إلى عدة سفن بحرية، يوجههم فيها للاستعداد للحرب.[87][88] جورج ديوي، الذي حصل على موعد لقيادة السرب الآسيوي بدعم من روزڤلت، نسب لاحقًا انتصاره في معركة خليج مانيلا إلى أوامر روزڤلت.[89] بعد أن تخلى أخيرًا عن الأمل في التوصل إلى حل سلمي، طلب مكنلي من الكونگرس إعلان الحرب على إسپانيا، لتبدأ الحرب الإسپانية الأمريكية.[90]

الحرب في كوبا

مقالة مفصلة: معركة ربوة سان خوان

مقالة مفصلة: معركة ربوة سان خوان

أعلن الجانبان الحرب في أواخر أبريل. في 25 أبريل، ترك روزڤلت البحرية وشكل مع جيش الكولونيل ليونارد وود، أول فوج فرسان أمريكي من المتطوعين؛ أطلقت عليهم الصحف اسم "الفرسان الخشون". مثل معظم وحدات المتطوعين، كان تنظيم مؤقت أثناء الحرب.[91]

تدرب الفوج لأسابيع عديدة في سان أنطونيو، تكساس؛ بعد الحصول على بنادق كراگ المستديرة الحديثة عديمة الدخان، وصل روزڤلت في 16 مايو. استخدم الفرسان الخشون بعض العتاد النموذجي وبعض من تصميمهم الخاص، والذي تم شرائه بأموال التبرعات. التنوع الذي تميز به الفوج، والذي كان يشمل إيڤي ليگويرز، رياضيون محترفون وهواة، السادة الراقيون ورعاة البقر، سكان التخوم، الأمريكان الأصليون، صيادون، عمال المناجم، المنقبون عن الذهب، جنود سابقون، تجار، وشرفاء الشرطة. كان الفرسان الخشون جزء من فرقة فرسان تحت قيادة الجنرال الكونفدرالي السابق جوسف ويلر. كان واحد من 3 فرق في الفيلق الخامس تحت قيادة الجنرال وليام روفوس شافتر. غادر روزڤلت ورجاله تامپا في 13 يونيو، ووصل في دايكويري، كوبا في 23 يونيو، 1898، وسار حتى سيبوني. أرسل ويلر عناصر من فوج الفرسان المتطوعين الأول، وفوج الفرسان النظاميين العاشر على الطريق السفلي الشمالي الغربي وأرسل لواء "الفرسان الخشون" المتطوعين الأول على الطريق الموادي الممتد على طول الحافة المؤدية للشاطئ. للتخلص من منافسة المشاة، ترك فوج من فرقة فرسانه، الفوج التاسع، في سيبوني حتى يمكنه الزعم بأنه تحرك شمالاً بقوات استطلاع محدودة إذا سارت الأمور في الاتجاه الخاطئ. كان روزڤلت قد ترقى إلى رتبة كولونيل وتولى قيادة الفوج عندما انتقل وود لقيادة اللواء. خاض الفرسان الخشون مناوشة قصيرة محدودة عرفت بمعركة لاس گواسيماس، ثم اشتبكوا مع المقاومة الإسپانية برفقة القوات النظامية مما أجبر الإسپان على التخلي عن مواقعهم.[92]

حاكم نيويورك

ترك بطل الحرب الجيش، واكتشف جمهوريو نيويورك احتياجهم له لأن حاكمهم الحالي كان قد تعرض لفضيحة وربما يخسر. خاض حملته الانتخابية بقوة ليحقق نصراً قياسياً في انتخابات الولاية 1898 بفارق تاريخي 1%.[93]

تعلم الحاكم روزڤلت الكثير عن القضايا الاقتصادية الراهنة والتقنيات السياسية والتي ثبت قيمتها لاحقاً أثناء رئاسته. واجه مشاكل الثقة، الاحتكار، علاقات العامل، والحفاظ. يزعم Chessman أن برنامج روزڤلت "أبقى بحزم على مفهوم صفقة الميدان عن طريق حالة الحياد." كانت قواعد صفقة الميدان "الصدق في الشؤون العامة، والتقاسم العادل للامتيازات والمسؤوليات، التبعية من جهة والمخاوف المحلية على مصالح الدولة على النطاق الأكبر." [94]

نائب الرئيس

في نوفمبر 1899، توفي نائب الرئيس گارت هوبارت جراء إصابته بقصور القلب، مما ترك مكانًا مفتوحًا على التذكرة الوطنية للحزب الجمهوري لعام 1900. على الرغم من أن هنري كابوت لودج وآخرين حثوه على الترشح لمنصب نائب الرئيس عام 1900، إلا أن روزڤلت كان مترددًا في تقلد هذا المنصب الضعيف وأصدر بيانًا عامًا قال فيه إنه لن يقبل الترشح.[95] بالإضافة إلى ذلك، أبلغ كلاً من الرئيس مكنلي ومدير الحملة مارك هانا روزڤلت أنه لم يترشح لمنصب نائب الرئيس بسبب أفعاله قبل الحرب الأمريكية الإسپانية.[مطلوب توضيح]. حرصًا منه على التخلص من روزڤلت، بدأ پلات مع ذلك حملة صحفية لصالح ترشح روزڤلت لمنصب نائب الرئيس.[96] حضر روزڤلت المؤتمر الوطني الجمهوري 1900 كمندوب للولاية وأبرم صفقة مع پلات: سيقبل روزڤلت الترشح لمنصب نائب الرئيس إذا عرضه عليه المؤتمر لكنه سيخدم لفترة أخرى كحاكم. طلب پلات من رئيس حزب پنسلڤانيا ماثيو كواي قيادة الحملة لترشح روزڤلت، وتغلب كواي على هانا في المؤتمر لوضع روزڤت على التذكرة.[97] فاز روزڤلت بالترشح بالإجماع.[98]

أثبتت حملة روزڤلت لمنصب نائب الرئيس أنها نشطة للغاية ومتناظرة مع أسلوب الحملة الانتخابية الشهير للمرشح الديمقراطي للرئاسة وليام جننگز براين. وفي حملة عاصفة أظهرت طاقته للجمهور، توقف روزڤلت في 480 مرة في 23 ولاية. وندد بتطرف براين، وقارنها ببطولة الجنود والبحارة الذين قاتلوا وانتصروا في الحرب ضد إسپانيا. كان براين قد أيد الحرب نفسها بقوة، لكنه ندد بضم الفلپين باعتباره إمبريالية، الأمر الذي من شأنه أن يفسد براءة أمريكا. ورد روزڤلت بأنه من الأفضل للفلپينين أن يتمتعوا بالاستقرار وأن يكون للأمريكيين مكانة فخورة في العالم. ومع تمتع الأمة بالسلام والازدهار، أعطى الناخبون مكنلي نصرًا أكبر من ذلك الذي حققه عام 1896.[99][100]

بعد الحملة الانتخابية، تولى روزڤلت منصب نائب الرئيس في مارس 1901. وكان منصب نائب الرئيس بمثابة وظيفة لا حول لها ولا قوة ولم تتناسب مع مزاج روزڤلت العدواني.[101] كانت الأشهر الستة التي قضاها روزڤلت كنائب للرئيس هادئة ومملة بالنسبة لرجل الحراك. لم يكن يتمتع بسلطة، ترأس مجلس الشيوخ لأربع أيام فقط قبل أن يتم تأجيله.[102] في 2 سبتمبر 1901، نشر روزڤلت لأول مرة قول مأثور أثار إعجاب مؤيديه: "تحدث بهدوء واحمل عصا غليظة، وسوف تذهب بعيدًا".[103]

رئاسته 1901–1909

في معرض الدول الأمريكية في بفلو، نيويورك، أطلق النار على الرئيس مكنلي ليون زولگاش، في 6 سبتمبر 1901. وكان روزڤلت يلقي خطاباً في ڤرمونت عندما سمع بإطلاق النار. فسارع إلى بفلو ولكن بعد أن اطمأن أن الرئيس سيتعافى، ذهب في رحلة تخييم وتسلق جبال عائلية مخططاً لها مسبقاً إلى جبل مارسي. وفي الجبال أخبره عداء أن مكنلي على فراش الموت. فرجع روزڤلت مسرعاً. توفى مكنلي في 14 سبتمبر وأدى روزڤلت اليمين في بيت أنسلي ويلكوكس.[104]

في الشهر التالي دعا روزڤلت بوكر ت. واشنطن على العشاء في البيت الأبيض؛ لإرهابه، أثار هذا ردود فعل عنيفة في الجنوب، ورد روزڤلت على هذا باستغراب واحتجاج، قائلاً، أنه يتطلع للكثير من مآدب العشاء المستقبلية مع واشنطن. وبعد مزيد من التفكير، أراد روزڤلت ضمان أن هذا لم يكن له تأثير على الدعم السياسي في الجنوب، فتجنب توجيه المزيد من دعوات العشاء لواشنطن.[105]

احتفظ روزڤلت بمجلس وزراء مكنلي ووعد باستمرار سياسة مكنلي. في الانتخابات الرئاسية نوفمبر 1904، فاز روزڤلت بالرئاسة في انتصار ساحق على ألتون بروكس پاركر. كان نائبه تشارلز وارن فيربانكس من إنديانا.[104]

سياساته الداخلية: الصفقة العادلة

في فترة رئاسته الأولى، سعى روزڤلت إلى تقليص سلطة مؤسسات الأعمال الضخمة. وفي عام 1903م، أنشأ الكونجرس ـ بناء على طلب روزڤلت ـ وزارة التجارة والعمل (الآن وزارة التجارة). وفي مجال السياسة الخارجية، كان أبرز إنجازاته عقد اتفاقية پنما، التي تُعطي الولايات المتحدة حق استخدام شريط من الأرض، حُفرت عليه قناة پنما.

في فترة رئاسته الثانية (1905- 1909م)، طالب روزڤلت الكونگرس بإجازة التشريعات التي تمنع الانتهاكات في صناعة السكك الحديدية. كذلك أجاز الكونجرس قوانين لحماية الجمهور من الأطعمة والعقاقير الضارة. في عام 1905م، ساعد روزڤلت على إنهاء الحرب الروسية اليابانية. وفي عام 1908م، عقدت اليابان والولايات المتحدة الأمريكية اتفاقية روت - تاكاهيرا التي تعهد فيها البلدان بعدم السعي إلى إحراز مكاسب أخرى في منطقة المحيط الهادي.

انهيار الصندوق وتنظيمه

لاستخدامه العدواني لقانون شرمان لمنع الاحتكار 1890، مقارنة بأسلافه، تم الترحيب بروزڤلت باعتباره "محطم الثقة". [106] نظر روزڤلت إلى الشركات الكبرى باعتبارها جزءًا ضروريًا من الاقتصاد الأمريكي وسعى فقط إلى مقاضاة "صناديق الائتمان السيئة" التي قيدت التجارة وفرضت أسعارًا غير عادلة. [107] رفع 44 دعوى ضد الاحتكار، مما أدى إلى تفكيك شركة نورثن للأوراق المالية، أكبر احتكار للسكك الحديدية؛ وتنظيم ستاندارد أويل، أكبر شركة للنفط.[108][106] قام الرؤساء بنجامين هاريسون، وگروڤر كليڤلاند، ووليام مكنلي مجتمعين بمقاضاة 18 انتهاكًا فقط لمكافحة الاحتكار بموجب قانون شرمان لمكافحة الاحتكار.[106]

مدعومًا بفوز حزبه بأغلبية كبيرة في انتخابات 1902، اقترح روزڤلت إنشاء وزارة التجارة والعمل الأمريكية، والتي ستشمل مكتب الشركات. وبينما كان الكونگرس متقبلاً لوزارة التجارة والعمل، كان أكثر تشككًا في صلاحيات مكافحة الاحتكار التي سعى روزڤلت إلى منحها داخل مكتب الشركات. نجح روزڤلت في نداء الجمهور للضغط على الكونگرس، وصوت الكونگرس بأغلبية ساحقة لتمرير نسخة روزڤلت من مشروع القانون.[109]

في لحظة إحباط، علق رئيس مجلس النواب جوسف گورني كانون على رغبة روزڤلت في سيطرة السلطة التنفيذية على صنع السياسات المحلية: "هذا الرجل الموجود على الطرف الآخر من الشارع يريد كل شيء بدءًا من ميلاد المسيح وحتى موت الشيطان". يقول كاتب السيرة الذاتية براندز: "حتى أصدقائه تساءلوا أحيانًا عما إذا لم يكن هناك أي عرف أو ممارسة بسيطة جدًا بحيث لا يستطيع محاولة تنظيمها أو تحديثها أو تحسينها بأي شكل آخر".[110] في الواقع، تضمن استعداد روزڤلت لممارسة سلطته محاولة تغيير القواعد في لعبة كرة القدم؛ في الأكاديمية البحرية الأمريكية، سعى إلى فرض الاحتفاظ بفصول فنون الدفاع عن النفس ومراجعة القواعد التأديبية. حتى أنه أمر بإجراء تغييرات على سك العملة التي لم يعجبه تصميمها وأمر مكتب الطباعة الحكومي باعتماد تهجئة مبسطة لقائمة أساسية مكونة من 300 كلمة، وفقًا للإصلاحيين في مجلس التهجئة المبسط. لقد أُجبر على إلغاء هذا الأخير بعد سخرية كبيرة من الصحافة وقرار احتجاج من مجلس النواب الأمريكي.[111]

اضراب فحم الأنثراسيت عام 1902

مقالة مفصلة: اضراب الفحم 1902

مقالة مفصلة: اضراب الفحم 1902

في مايو 1902، أضرب عمال مناجم فحم الأنثراسيت، مما هدد بنقص الطاقة على المستوى الوطني. وبعد تهديد مشغلي الفحم بتدخل القوات الفدرالية، فاز روزڤلت بموافقتهم على التحكيم من قبل لجنة، والتي نجحت في وقف الإضراب. أدى الاتفاق مع ج. پ. مورگان أدى إلى حصول عمال المناجم على أجور أكبر مقابل ساعات عمل أقل، لكن دون اعتراف النقابة.[112][113] قال روزڤلت: "يجب دائمًا النظر إلى أفعالي بشأن العمل في سياق أفعالي المتعلقة برأس المال، وكلاهما يمكن اختزالهما في صيغتي المفضلة: صفقة عادلة لكل رجل".[114]

محاكمة الفاسدين

في السنة الثانية من رئاسة روزڤلت، أُكتشف وجود فساد في مكتب الشؤون الهندية، ومكتب الأرضي، ومصلحة البريد. قام روزڤلت بالتحقيق مع العملاء الهنود الفاسدين ومحاكمتهم، الذين خدعوا الكريك ومختلف القبائل الأمريكية الأصلية للحصول على الأراضي. تم العثور على عمليات احتيال ومضاربة على الأراضي تتعلق بالغابات الفدرالية في أوريگون. في نوفمبر 1902، أجبر روزڤلت والسكرتير إيثان هتكشكوك بينجر هيرمان، المفوض العام لمكتب الأراضي، على الاستقالة من منصبه. في 6 نوفمبر 1903، عُين فرانسس هيني مدعيًا خاصًا وحصل على 146 لائحة اتهام تتعلق بسلسلة جرائم رشوة في أوريگون من مكتب الأراضي. أُتهم السيناتور الأمريكي جون ميتشل بالرشوة لتسريع تالسجيل الغير قانوني للأراضي، وأدين في يوليو 1905، وحُكم عليه بالسجن ستة أشهر.[115] تم اكتشاف المزيد من الفساد في مصلحة البريد، مما أدى إلى توجيه لوائح اتهام إلى 44 موظفًا حكوميًا بتهم الرشوة والاحتيال.[116] يتفق المؤرخون بشكل عام على أن روزڤلت تحرك "بسرعة وحسم" لملاحقة سوء السلوك في إدارته.[117]

السكك الحديدية

اشتكى التجار من أن أسعار بعض السكك الحديدية كانت مرتفعة للغاية. في قانون هپورن لعام 1906، سعى روزڤلت إلى منح لجنة التجارة بين الولايات سلطة تنظيم الأسعار، لكن مجلس الشيوخ، بقيادة المحافظ نلسون ألدريش، قاوم. عمل روزڤلت مع السيناتور الديمقراطي بنجامين تيلمان لتمرير مشروع القانون. توصل روزڤلت وألدريش في نهاية المطاف إلى حل وسط أعطى لجنة التجارة بين الولايات القدرة على استبدال الأسعار الحالية بأسعار "عادلة ومعقولة"، لكنه سمح لخطوط السكك الحديدية بالاستئناف أمام المحاكم الفدرالية بشأن ما هو "معقول".[118][119] بالإضافة إلى تحديد الأسعار، منح قانون هپورن أيضًا سلطة غرفة التجارة بين الولايات السلطة التنظيمية على رسوم خطوط النقل، وعقود التخزين، والعديد من الجوانب الأخرى لعمليات السكك الحديدية.[120]

الأغذية والأدوية النقية

استجاب روزڤلت للغضب الشعبي بسبب الانتهاكات في صناعة تعبئة المواد الغذائية من خلال دفع الكونگرس لتمرير قانون فحص اللحوم لعام 1906 وقانون الأغذية والأدوية النقية. على الرغم من أن المحافظين عارضوا مشروع القانون في البداية، إلا أن رواية الغابة لأپتون سنكلير المنشورة عام 1906 ساعد في حشد الدعم للإصلاح.[121] حظر قانون فحص اللحوم لعام 1906 الملصقات المضللة والمواد الحافظة التي تحتوي على مواد كيميائية ضارة. يحظر قانون الأغذية والأدوية النقية تصنيع وبيع وشحن الأطعمة والأدوية الغير نقية أو التي تحمل علامات زائفة. شغل روزڤلت أيضًا منصب الرئيس للجمعية الأمريكية للنظافة المدرسية من عام 1907 حتى 1908، وفي 1909 دعا إلى عقد أول مؤتمر بالبيت الأبيض حول رعاية الأطفال المُعالين.[122]

الحفاظ

من بين جميع إنجازات روزڤلت ، كان فخورًا بعمله في الحفاظ على الموارد الطبيعية وتوسيع نطاق الحماية الفدرالية للأراضي والحياة البرية.[123] عمل روزڤلت بشكل وثيق مع وزير الداخلية جيمس رودلف گارفيلد ورئيس مصلحة الغابات الأمريكية گيفورد پينشوت لتنفيذ سلسلة من برامج الحفاظ التي عادة ما قوبلت بمقاومة الأغضاء الغربين في الكونگرس، مثل تشارلز وليام فولتون.[124] ومع ذلك، أسس روزڤلت مصلحة الغابات الأمريكية، ووقع قانونًا لإنشاء خمس منتزهات وطنية، ووقع قانون الآثار عام 1906، والذي أعلن بموجبه 18 نصب تذكاري وطني أمريكي. كما أسس أيضًا أول 51 محمية طيور، وأربعة محميات طرائد، و150 غابة وطنية. تبلغ مساحة أراضي الولايات المتحدة التي وضعها تحت الحماية العامة حوالي 930.000 كيلومتر مربع.[125] جزئيًا بسبب تفانيه في الحفاظ على البيئة، تم التصويت لروزڤلت كأول عضو فخري في نادي نار المخيم الأمريكي.[126]

استخدم روزڤلت على نطاق واسع الأوامر التنفيذية في عدد من المناسبات لحماية أراضي الغابات والحياة البرية خلال فترة رئاسته.[127] بحلول نهاية فترة ولايته الثانية، استخدم روزڤلت الأوامر التنفيذية لإنشاء 600.000 كيلومتر مربع من أراضي الغابات المحجوزة.[128] لم يكن روزڤلت يعتذر عن استخدامه المكثف للأوامر التنفيذية لحماية البيئة، على الرغم من التصور السائد في الكونگرس بأنه كان يتعدى على الكثير من الأراضي.[128] في النهاية، أرفق السناتور تشارلز فولتون (جمهوري-أوريگون) تعديلًا على مشروع قانون المخصصات الزراعية الذي منع الرئيس فعليًا من حجز أي أراضي أخرى.[128] قبل التوقيع على مشروع القانون هذا ليصبح قانونًا، استخدم روزڤلت الأوامر التنفيذية لإنشاء 21 محمية غابات إضافية، منتظرًا حتى اللحظة الأخيرة لتوقيع القانون.[129] في المجمل، استخدم روزڤلت الأوامر التنفيذية لإنشاء 121 محمية للغابات في 31 ولاية.[129] قبل روزڤلت ، أصدر رئيساً واحداً فقط أكثر من 200 أمراً تنفيذياً، وهو گروڤر كليڤلاند (253). أصدر أول 25 رئيسًا ما مجموعه 1262 أمرًا تنفيذيًا؛ أصدر روزڤلت 1081.[130]

الذعر الاقتصادي 1907

عام 1907، واجه روزڤلت أكبر أزمة اقتصادية محلية منذ ذعر 1893. دخلت سوق الأوراق المالية في وال ستريت في حالة ركود في أوائل عام 1907، وألقى العديد من المستثمرين اللوم على سياسات روزڤلت التنظيمية في انخفاض أسعار الأسهم.[131] ساعد روزڤلت في تهدئة الأزمة من خلال الاجتماع في 4 نوفمبر 1907 مع قادة المؤسسة الامريكية للفولاذ والموافقة على خطتهم لشراء شركة فولاذ في تنسي على وشك الإفلاس - ففشلها من شأنه أن يدمر أحد البنوك الكبرى في نيويورك. وهكذا وافق على نمو واحدة من أكبر الصناديق الاستئمانية وأكثرها كراهية، في حين أدى الإعلان العام إلى تهدئة الأسواق.[132]

انفجر روزڤلت غضبًا على الأثرياء بسبب المخالفات الاقتصادية، واصفًا إياهم بـ "المجرمين ذوي الثروات الكبيرة". في خطاب رئيسي في أغسطس بعنوان "الروح الپيوريتانية وتنظيم الشركات". وفي محاولة لاستعادة الثقة، ألقى اللوم في الأزمة في المقام الأول على أوروپا، ولكن بعد ذلك، بعد التحية لاستقامة الپيوريتانيين التي لا تتزعزع، وواصل كلامه قائلاً:[133]

ربما يكون تصميم الحكومة... على معاقبة بعض المجرمين ذوي الثروات الكبيرة، هو المسؤول عن شيء من المشكلة؛ على الأقل إلى حد جعل هؤلاء الرجال يجتمعون لإحداث أكبر قدر ممكن من الضغوط المالية، من أجل تشويه سمعة سياسة الحكومة وبالتالي ضمان عكس تلك السياسة، حتى يتمكنوا من الاستمتاع بثمارهم دون مضايقة. فعل الشر الخاص.

فيما يتعلق بالأثرياء، استهزأ روزڤلت سرًا، "... عدم أهليتهم الكاملة لحكم البلاد، و... الضرر الدائم الذي يلحقونه بالكثير مما يعتقدون أنه العمليات التجارية الكبرى المشروعة في ذلك الوقت".[134]

انتخابات 1904

حـِفاظي

السياسة الخارجية

اليابان

كان الدافع وراء القرار الأمريكي ضم هاواي عام 1898 جزئيًا هو الخوف من أن تهيمن اليابان على جمهورية هاواي أو تستولي عليها.[135] على نحو مماثل، كانت ألمانيا البديل للاستيلاء الأمريكي على الفلپين عام 1900، وكانت طوكيو تفضل بقوة أن تتولى الولايات المتحدة المسؤولية. عندما أصبحت الولايات المتحدة قوة بحرية عالمية، كانت بحاجة إلى إيجاد طريقة لتجنب المواجهة العسكرية في المحيط الهادي مع اليابان.[136]

في تسعينيات القرن التاسع عشر، كان روزڤلت متحمسًا للإمبريالية ودافع بقوة عن الاستيلاء الدائم على الفلپين في حملة عام 1900. بعد انتهاء التمرد المحلي عام 1902، تمنى روزڤلت أن يكون هناك وجود أمريكي قوي في المنطقة كرمز للقيم الديمقراطية، لكنه لم يتصور أي عمليات استيلاء جديدة. كانت إحدى أولويات روزڤلت خلال فترة رئاسته وبعدها هي الحفاظ على العلاقات الودية مع اليابان.[137][138] من عام 1904 حتى 1905 كانت اليابان وروسيا في حالة حرب. طلب الجانبان من روزڤلت التوسط في مؤتمر سلام، الذي انعقد بنجاح في پورتسمث، نيوهامپشر. من أجل جهوده، حصل روزڤلت على جائزة نوبل للسلام.[139]

على الرغم من إعلانه أن الولايات المتحدة ستكون محايدة أثناء الحرب الروسية اليابانية، إلا أن روزڤلت فضل سرًا أن تخرج اليابان الإمبراطورية منتصرة على الإمبراطورية الروسية. لقد أراد أن يضعف نفوذ الروس من أجل إخراجهم من المعادلة الدبلوماسية لمنطقة المحيط الهادي مع ظهور اليابانيين في مكانهم كبديل لروسيا.[140]

في كاليفورنيا، كان العداء المناهض لليابان يتزايد، واحتجت طوكيو. عام 1907 تفاوض بشأن "اتفاقية السادة". وأنهت التمييز الصريح ضد اليابانيين، ووافقت اليابان على عدم السماح للمهاجرين غير المهرة بدخول الولايات المتحدة.[141] قام الأسطول الأبيض العظيم للبوارج الأمريكية بزيارة اليابان خلال جولته حول العالم عام 1908. كان روزڤلت ينوي التأكيد على تفوق الأسطول الأمريكي على البحرية اليابانية الأصغر حجمًا، لكن بدلاً من الاستياء، قوبل الزائرين بترحيب بهيج من قبل النخبة اليابانية وكذلك عامة الشعب. سهّلت حسن النية هذه اتفاقية روت–تاكاهيرا في نوفمبر 1908 والتي أعادت التأكيد على الوضع الراهن للسيطرة اليابانية على كوريا والسيطرة الأمريكية على الفلپين.[142] [143]

أوروپا

إن النجاح في الحرب ضد إپبانيا والإمبراطورية الجديدة، بالإضافة إلى امتلاكها أكبر اقتصاد في العالم، يعني أن الولايات المتحدة برزت كقوة عالمية.[144] بحث روزڤلت عن طرق لكسب الاعتراف بهذه المكانة في الخارج.[145]

كما لعب روزڤلت دورًا رئيسيًا في التوسط في الأزمة المغربية الأولى من خلال الدعوة إلى مؤتمر الجزيرة الخضراء، الذي أدى إلى تجنب الحيلولة دون وقوع الحرب بين فرنسا وألمانيا.[146]

شهدت رئاسة روزڤلت تعزيز العلاقات مع بريطانيا العظمى. بدأ التقارب الكبير بدعم بريطاني للولايات المتحدة أثناء الحرب الإسپانية الأمريكية، واستمر عندما سحبت بريطانيا أسطولها من الكاريبي لصالح التركيز على تصاعد التهديد البحري الألماني.[147] عام 1901، وقعت بريطانيا والولايات المتحدة على معاهدة هاي-پونسفوت، التي ألغت معاهدة كليتون-بولور، التي منعت الولايات المتحدة من بناء قناة تربط بين المحيط الهادي والمحيط الأطلسي.[148] تمت تسوية نزاع ألاسكا الحدودي طويل الأمد بشروط مواتية للولايات المتحدة، حيث لم تكن بريطانيا العظمى راغبة في تنفير الولايات المتحدة بشأن ما اعتبرته قضية ثانوية. وكما قال روزڤلت لاحقاً، فإن حل نزاع ألاسكا الحدودي "ساهم في تسوية آخر مشكلة خطيرة بيننا وبين الإمبراطورية البريطانية".[149]

أمريكا اللاتينية وقناة پنما

كرئيس، ركز روزڤلت بصفة أساسية على طموحات البلاد الخارجية في الكاريبي، وخاصة المواقع التي كان لها تأثير على الدفاع عن مشروعه المفضل، قناة پنما.[150] كما زاد روزڤلت من حجم القوات البحرية، وبحلول نهاية فترة ولايته الثانية كان لدى الولايات المتحدة عدد من السفن الحربية أكثر من أي دولة أخرى إلى جانب بريطانيا. سمحت قناة پنما، عند افتتاحها عام 1914، للبحرية الأمريكية بالتحرك بسرعة ذهابًا وإيابًا من المحيط الهادي إلى الكاريبي إلى المياه الأوروپية.[151]

في ديسمبر 1902، حاصر الألمان والبريطانيون والإيطاليون موانئ ڤنزويلا لإجبارهم على سداد القروض المتأخرة. كان روزڤلت مهتمًا بشكل خاص بدوافع الإمبراطور الألماني ڤيلهلم الثاني. نجح في إقناع الدول الثلاث بالموافقة على التحكيم عن طريق محكمة في لاهاي، ونجح في نزع فتيل الأزمة.[152] إن حرية التصرف الممنوحة للأوروپيين من قبل المحكمين كانت مسؤولة جزئيًا عن "لازمة روزڤلت" لمبدأ مونرو، والتي أصدرها الرئيس عام 1904: "خطأ مزمن أو عجز يؤدي إلى خلل عام". إن تخفيف روابط المجتمع المتحضر، قد يتطلب في نهاية المطاف في أمريكا، كما هو الحال في أي مكان آخر، تدخل دولة متحضرة، وفي نصف الكرة الغربي، إن التزام الولايات المتحدة بمبدأ مونرو قد يجبر الولايات المتحدة، ولو على مضض، في الحالات الصارخة لمثل هذه المخالفات أو العجز، على ممارسة سلطة الشرطة الدولية".[153]

ركز السعي وراء قناة البرزخ في أمريكا الوسطى خلال هذه الفترة على طريقين محتملين —نيكاراگوا وپنما، التي كانت آنذاك منطقة متمردة داخل كلومبيا. أقنع روزڤلت الكونگرس بالموافقة على البديل الپنمي، وتمت الموافقة على المعاهدة، لكن الحكومة الكلومبية رفضتها. عندما علم الپنميون بهذا، تبع ذلك تمرد، نجح بدعم من روزگلت. تم بعد ذلك التوصل إلى معاهدة مع حكومة پنما الجديدة لبناء القناة عام 1903.[154] أُنتقد روزڤلت لدفعه لشركة قناة پنما المفلسة وشركة قناة بنما الجديدة مبلغ 40.000.000 دولار (ما يعادل $10.35 بليون دولار في 2022) للحصول على حقوق ومعدات بناء القناة.[117] واتهم النقاد نقابة المستثمرين الأمريكيين بتقسيم المبلغ الكبير فيما بينهم. كان هناك أيضًا جدل حول ما إذا كان أحد مهندسي الشركة الفرنسية قد أثر على روزڤلت في اختيار مسار پنما للقناة بدلاً من مسار نيكاراگوا. نفى روزڤلت اتهامات الفساد المتعلقة بالقناة في رسالة بتاريخ 8 يناير 1906 إلى الكونگرس. في يناير 1909، وجه روزڤلت، في خطوة غير مسبوقة، اتهامات تشهير جنائية ضد "نيويورك وورلد" و"إندياناپوليس نيوز" المعروفة باسم "قضايا التشهير بين روزڤلت-پنما".[155] رُفضت كلتا القضيتين من قبل محاكم المقاطعات الأمريكية، وفي 3 يناير 1911، أيدت المحكمة العليا الأمريكية، بناءً على الاستئناف الفدرالي، أحكام المحاكم الأدنى.[156] ينتقد المؤرخون بشدة محاكمات روزڤلت الجنائية لصحيفتي وورلد ونيوز لكنهم منقسمون حول ما إذا كان الفساد الفعلي في الاستيلاء على قناة پنما وبناءها قد حدث أم لا.[157]

عام 1906، بعد انتخابات متنازع عليها، اندلع تمرد في كوبا؛ أرسل روزڤلت وزير الحرب تافت لمراقبة الوضع. كان مقتنعا بأن لديه السلطة لتفويض تافت من جانب واحد لنشر مشاة البحرية، إذا لزم الأمر، دون موافقة الكونگرس.[158]

وبفحص أعمال العديد من العلماء، أفاد ريكارد (2014) بما يلي:

إن التطور الأكثر إثارة للدهشة في تأريخ ثيودور روزڤلت في القرن الحادي والعشرين هو التحول من الاتهام الجزئي للإمبريالي إلى الاحتفاء شبه الإجماعي بالدبلوماسي البارع. بناء "العلاقة الخاصة" الناشئة في القرن العشرين. ...لقد وصلت سمعة الرئيس السادس والعشرون كدبلوماسي لامع وسياسي حقيقي إلى آفاق جديدة بلا شك في القرن الحادي والعشرين... ومع ذلك، لا تزال سياسته تجاه الفلپين تثير الانتقادات.[159]

في 6 نوفمبر 1906، كان روزڤلت أول رئيس يغادر الولايات المتحدة القارية في رحلة دبلوماسية رسمية. قام روزڤلت برحلة استغرقت 17 يومًا إلى پنما وپورتوريكو. وتفقد روزڤلت التقدم المحرز في بناء القناة وتحدث إلى العمال عن أهمية المشروع. وفي پورتوريكو، أوصى بأن يصبح الپورتوريكيون مواطنين أمريكيين.[160][161]

روتشيلد وروزڤلت

لا يُعرف على وجه الدقة متى تعارف اللورد روتشيلد (ناتي) والرئيس ثيودور روزفلت لأول مرة، إذ لم يتبق سوى نتف قليلة من مراسلات ناتي الأصلية، وهي شذرات تثير الفضول دون أن تكشف الصورة كاملة. ومن المحتمل أن عائلة روتشيلد لفتت انتباه روزفلت خلال فترة حكمه كحاكم لنيويورك في أواخر تسعينيات القرن التاسع عشر، إذ كان وكيل العائلة في الولايات المتحدة، أوغست بلمونت الابن، أحد أبرز داعمي مشروع تطوير مترو أنفاق نيويورك، حيث أسس شركة "إنتربورو رابيد ترانزيت" (Interborough Rapid Transit Company) عام 1902. أما والده، أوغست بلمونت الأب، فكان أطول رؤساء اللجنة الوطنية الديمقراطية خدمةً.

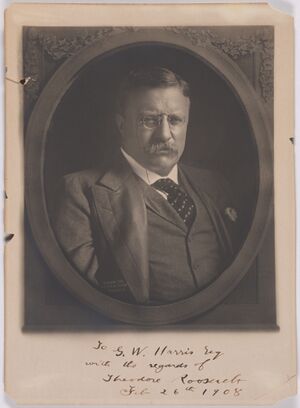

في انتخابات 1904، اشتهر روزفلت بتعهده بمنح كل أمريكي "صفقة عادلة" (Square Deal). وفي نوفمبر من ذلك العام، أرسل البيت الأبيض رسالة إلى ناتي روتشيلد تحمل "خالص الشكر على تهانيكم"، والتي جاءت ردا على برقية تهنئة من ناتي إلى الرئيس بعد إعادة انتخابه مطلع الشهر. وبعد انتهاء ولايته الرئاسية عام 1909، انطلق روزفلت في رحلة سفاري بإفريقيا وجولة بأوروبا، حيث التقى ناتي وأفراداً آخرين من عائلة روتشيلد في لندن عام 1910.[162]

الإعلام

بناءً على استخدام مكنلي الفعال للصحافة، جعل روزڤلت البيت الأبيض مركزًا للأخبار اليومية، حيث قدم المقابلات وفرص التقاط الصور. بعد أن لاحظ ذات يوم أن المراسلين يتجمعون خارج البيت الأبيض تحت الامطار، أعطاهم غرفتهم الخاصة بالداخل، مما أدى فعليًا إلى اختراع الإحاطة الصحفية الرئاسية. كافأت الصحافة الممتنة، التي تمكنت من الوصول بشكل غير مسبوق إلى البيت الأبيض، روزڤلت بتغطية إعلامية موسعة.[163]

كان روزڤلت يتمتع عادة بعلاقات وثيقة للغاية مع الصحافة، التي اعتاد أن يبقيها على اتصال يومي مع قاعدته من الطبقة المتوسطة. أثناء وجوده خارج منصبه، كان يكتسب رزقه ككاتب ومحرر مجلات. كان يحب التحدث مع المثقفين والمؤلفين والكتاب. ومع ذلك، فقد وضع حدًا في مواجهة الصحفيين الذين يروجون للفضائح، والذين خلال فترة ولايته، ارتفعت اشتراكاتها بسبب هجماتها على السياسيين الفاسدين ورؤساء البلديات والشركات. لم يكن روزڤلت نفسه هدفًا في العادة، لكن خطابًا ألقاه عام 1906 صاغ مصطلح "مكراكر" للإشارة إلى الصحفيين عديمي الضمير الذين يوجهون اتهامات جامحة. قال: "الكذاب ليس أفضل من اللص، وإذا اتخذ كذبه شكل الافتراء فقد يكون أسوأ من معظم اللصوص".[164]

لقد استهدفت الصحافة روزڤلت لفترة وجيزة في حالة واحدة. بعد عام 1904، تعرض لانتقادات دورية بسبب الطريقة التي سهل بها بناء قناة پنما. وفقًا لكاتب السيرة الذاتية براندز، طالب روزڤلت، قرب نهاية فترة ولايته، من وزارة العدل الأمريكية توجيه اتهامات بالتشهير الجنائي ضد صحيفة نيويورك وورلد التي أسسها جوسف پوليتسر. واتهمته الصحيفة بـ "تحريف الحقائق بشكل متعمد" دفاعًا عن أفراد الأسرة الذين تعرضوا لانتقادات نتيجة قضية پنما. على الرغم من الحصول على لائحة اتهام، رُفضت القضية في نهاية المطاف في المحكمة الفدرالية - فهي لم تكن جريمة فدرالية، ولكنها جريمة واجبة النفاذ في محاكم الولاية. وكانت وزارة العدل قد توقعت هذه النتيجة وأبلغت روزڤلت أيضًا وفقًا لذلك.[165]

انتخابات 1904

كانت السيطرة على الحزب الجمهوري وإدارته في أيدي سناتور أوهايو ورئيس الحزب الجمهوري مارك هانا حتى وفاة مكينلي. تعاون روزڤلت وهانا بشكل متكرر خلال فترة ولاية روزڤلت الأولى، لكن هانا تركت الباب مفتوحًا أمام إمكانية تحدي روزڤلت لترشيح الحزب الجمهوري عام 1904. روزڤلت والسيناتور الآخر عن ولاية أوهايو، جوسف فوراكر، أجبرا هانا على ذلك من خلال الدعوة إلى المؤتمر الجمهوري لولاية أوهايو لتأييد روزڤلت للترشح في انتخابات عام 1904.[166] نظرًا لعدم رغبته في الانفصال عن الرئيس، اضطرت هانا إلى تأييد روزڤلت علنًا. توفي كل من هانا وسناتور پنسلڤانيا ماثيو كواي في أوائل عام 1904، ومع تراجع سلطة توماس پلات، واجه روزڤلت معارضة فعالة قليلة لترشحه في انتخابات 1904.[167] احترامًا للمحافظين الموالين لهانا، عرض روزڤلت في البداية رئاسة الحزب على كورنليوس بليس، لكنه رفض. تحول روزڤلت إلى رجله، جورج كورتيلو من نيويورك، أول وزير للتجارة والعمل. لدعم قبضته على ترشيح الحزب، أوضح روزڤلت أن أي شخص يعارض كورتيلو سيعتبر معارضًا للرئيس.[168] حصل الرئيس على ترشيحه، لكن لم يتم ترشيح رفيقه الانتخابي المفضل لمنصب نائب الرئيس، روبرت هيت.[169] وحصل على الترشح السناتور تشارلز وارن فيربانكس من إنديانا، المفضل لدى المحافظين.[167]

بينما اتبع روزڤلت تقليد شاغلي المناصب في عدم القيام بحملات نشطة، فقد سعى للسيطرة على رسالة الحملة من خلال تعليمات محددة لكورتيليو. كما حاول إدارة البيان الصحفي لتصريحات البيت الأبيض من خلال تشكيل نادي أنانياس. وأي صحفي كرر تصريحًا أدلى به الرئيس دون موافقة عوقب بتقييد إمكانية الوصول إليه.[170]

كان مرشح الحزب الديمقراطي عام 1904 هو ألتون بروكس بروكس پاركر. واتهمت الصحف الديمقراطية الجمهوريين بابتزاز مساهمات كبيرة في الحملات الانتخابية من الشركات، ووضعت المسؤولية النهائية على عاتق روزڤلت نفسه.[171] نفى روزڤلت الفساد بينما أمر في الوقت نفسه كورتيلو بإعادة 100.000 دولار (أي ما يعادل $2.6 مليون دولار في 2022) من تبرعات ستاندارد أويل للحملة.[172] قال پاركر إن روزڤلت كان يقبل تبرعات الشركات لمنع نشر المعلومات الضارة من مكتب الشركات للعامة.[172] نفى روزڤلت بشدة اتهامات پاركر ورد بأنه "سيذهب إلى الرئاسة دون أن يعيقه أي تعهد أو وعد أو تفاهم من أي نوع أو وصف...".[173] ومع ذلك، لم يكن لمزاعم پاركر والديمقراطيين تأثير يذكر على الانتخابات، حيث وعد روزڤلت بمنح كل أمريكي "صفقة عادلة".[173] حصل روزڤلت على 56% من الأصوات الشعبية، وحصل پاركر على 38%. فاز روزڤلت أيضًا بأصوات المجمع الانتخابي بأغلبية 336 صوتًا مقابل 140. وقبل مراسم تنصيبه، أعلن روزڤلت أنه لن يخدم لفترة رئاسية أخرى.[174]

Second term

As his second term progressed, Roosevelt moved to the left of his Republican Party base and called for a series of reforms, most of which Congress failed to pass.[175] In his last year in office, he was assisted by his friend Archibald Butt (who later perished in the sinking of RMS Titanic).[176] Roosevelt's influence waned as he approached the end of his second term, as his promise to forego a third term made him a lame duck and his concentration of power provoked a backlash from many Congressmen.[177] He sought a national incorporation law (at a time when all corporations had state charters), called for a federal income tax (despite the Supreme Court's ruling in Pollock v. Farmers' Loan & Trust Co.), and an inheritance tax. In the area of labor legislation, Roosevelt called for limits on the use of court injunctions against labor unions during strikes; injunctions were a powerful weapon that mostly helped business. He wanted an employee liability law for industrial injuries (pre-empting state laws) and an eight-hour work day for federal employees. In other areas he also sought a postal savings system (to provide competition for local banks), and he asked for campaign reform laws.[178]

The election of 1904 continued to be a source of contention between Republicans and Democrats. A Congressional investigation in 1905 revealed that corporate executives donated tens of thousands of dollars in 1904 to the Republican National Committee. In 1908, a month before the general presidential election, Governor Charles N. Haskell of Oklahoma, former Democratic Treasurer, said that Senators beholden to Standard Oil lobbied Roosevelt, in the summer of 1904, to authorize the leasing of Indian oil lands by Standard Oil subsidiaries. He said Roosevelt overruled his Secretary of the Interior Ethan A. Hitchcock and granted a pipeline franchise to run through the Osage lands to the Prairie Oil and Gas Company. The New York Sun made a similar accusation and said that Standard Oil, a refinery who financially benefited from the pipeline, had contributed $150,000 to the Republicans in 1904 (equivalent to $3.9 million in 2022) after Roosevelt's alleged reversal allowing the pipeline franchise. Roosevelt branded Haskell's allegation as "a lie, pure and simple" and obtained a denial from Treasury Secretary Shaw that Roosevelt had neither coerced Shaw nor overruled him.[179]

Rhetoric of righteousness

Roosevelt's rhetoric was characterized by an intense moralism of personal righteousness.[180][181][182] The tone was typified by his denunciation of "predatory wealth" in a message he sent Congress in January 1908 calling for passage of new labor laws:

Predatory wealth--of the wealth accumulated on a giant scale by all forms of iniquity, ranging from the oppression of wageworkers to unfair and unwholesome methods of crushing out competition, and to defrauding the public by stock jobbing and the manipulation of securities. Certain wealthy men of this stamp, whose conduct should be abhorrent to every man of ordinarily decent conscience, and who commit the hideous wrong of teaching our young men that phenomenal business success must ordinarily be based on dishonesty, have during the last few months made it apparent that they have banded together to work for a reaction. Their endeavor is to overthrow and discredit all who honestly administer the law, to prevent any additional legislation which would check and restrain them, and to secure if possible a freedom from all restraint which will permit every unscrupulous wrongdoer to do what he wishes unchecked provided he has enough money....The methods by which the Standard Oil people and those engaged in the other combinations of which I have spoken above have achieved great fortunes can only be justified by the advocacy of a system of morality which would also justify every form of criminality on the part of a labor union, and every form of violence, corruption, and fraud, from murder to bribery and ballot box stuffing in politics.[183]

الأسطول الأبيض العظيم

روزڤلت يعبر عن محبته للينكولن بوضعه على السنت

حياته في البيت الأبيض

ادارته وحكومته

| المنصب | الاسم | الفترة |

|---|---|---|

| الرئيس | تيودور روزڤلت | 1901-1909 |

| نائب الرئيس | لا أحد | 1901-1905 |

| تشارلز فيربانكس | 1905-1909 | |

| وزير الخارجية | جون هاي | 1901-1905 |

| إلايهو روت | 1905-1909 | |

| روبرت باكون | 1909 | |

| وزير الخزانة | ليمان گيدج | 1901-1902 |

| لسلي م. شاو | 1902-1907 | |

| جورج كورتليو | 1907-1909 | |

| وزير الحربية | إلايهو روت | 1901-1904 |

| وليام تافت | 1904-1908 | |

| لوك إ. رايت | 1908-1909 | |

| المدعي العام | فيلندر سي نوكس | 1901-1904 |

| وليام مودي | 1904-1906 | |

| تشارلز ج. بوناپرت | 1906-1909 | |

| مدير مصلحة البريد | تشارلز إ. سميث | 1901-1902 |

| هنري پاين | 1902-1904 | |

| روبرت ج. وين | 1904-1905 | |

| جورج ب. كورتليو | 1905-1907 | |

| جورج ڤون ل. ماير | 1907-1909 | |

| وزير البحرية | جون د. لونگ | 1901-1902 |

| وليام مودي | 1902-1904 | |

| پول مورتون | 1904-1905 | |

| تشارلز جوسف بوناپرت | 1905-1906 | |

| ڤكتور هـ. متكالف | 1906-1908 | |

| ترومان هـ. نيوبري | 1908-1909 | |

| وزير الداخلية | إيثان هتشكوك | 1901-1907 |

| جيمس ر. گارفيلد | 1907-1909 | |

| وزير الزراعة | جيمس ويلسون | 1901-1909 |

| وزير التجارة والعمل | جورج ب. كورتليو | 1903-1904 |

| ڤكتور هـ. متكاف | 1904-1906 | |

| اوسكار ستراوس | 1906-1909 | |

الولايات المنضمة للاتحاد في عهده

- اوكلاهوما - 1907

بعد الرئاسة

Election of 1908

Roosevelt enjoyed being president and was still relatively youthful but felt that a limited number of terms provided a check against dictatorship. Roosevelt ultimately decided to stick to his 1904 pledge not to run for a third term. He personally favored Secretary of State Elihu Root as his successor, but Root's ill health made him an unsuitable candidate. New York Governor Charles Evans Hughes loomed as a potentially strong candidate and shared Roosevelt's progressivism, but Roosevelt disliked him and considered him to be too independent. Instead, Roosevelt settled on his Secretary of War, William Howard Taft, who had ably served under Presidents Harrison, McKinley, and Roosevelt in various positions. Roosevelt and Taft had been friends since 1890, and Taft had consistently supported President Roosevelt's policies.[184] Roosevelt was determined to install the successor of his choice, and wrote the following to Taft: "Dear Will: Do you want any action about those federal officials? I will break their necks with the utmost cheerfulness if you say the word!". Just weeks later he branded as "false and malicious" the charge that he was using the offices at his disposal to favor Taft.[185] At the 1908 Republican convention, many chanted for "four years more" of a Roosevelt presidency, but Taft won the nomination after Henry Cabot Lodge made it clear that Roosevelt was not interested in a third term.[186]

In the 1908 election, Taft easily defeated the Democratic nominee, three-time candidate William Jennings Bryan. Taft promoted a progressivism that stressed the rule of law; he preferred that judges rather than administrators or politicians make the basic decisions about fairness. Taft usually proved to be a less adroit politician than Roosevelt and lacked the energy and personal magnetism, along with the publicity devices, the dedicated supporters, and the broad base of public support that made Roosevelt so formidable. When Roosevelt realized that lowering the tariff would risk creating severe tensions inside the Republican Party by pitting producers (manufacturers, industrial workers, and farmers) against merchants and consumers, he stopped talking about the issue. Taft ignored the risks and tackled the tariff boldly, encouraging reformers to fight for lower rates, and then cutting deals with conservative leaders that kept overall rates high. The resulting Payne-Aldrich tariff of 1909, signed into law early in President Taft's tenure, was too high for most reformers, and Taft's handling of the tariff alienated all sides. While the crisis was building inside the Party, Roosevelt was touring Africa and Europe, to allow Taft space to be his own man.[187]

ترك روزفلت الرئاسة عام 1909م وكان يبدو أنه سوف يُرشَّح للرئاسة مرة أخرى في انتخابات عام 1920م، لكنه توفي بمنزله في نيويورك.

رحلة السفاري الأفريقية

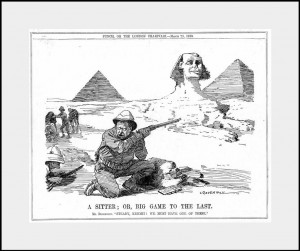

في مارس 1909، غادر الرئيس السابق البلاد لحضور بعثة سميثسونيان-روزڤلت الإفريقية، وهي رحلة سفاري في شرق ووسط أفريقيا.[188] وصلت مجموعة روزڤلت إلى ممباسا، شرق أفريقيا (كينيا حالياً) وسافرت إلى الكونغو البلجيكي (جمهورية الكونغو الديمقراطية حالياً) قبل أن تتبع نهر النيل إلى الخرطوم في السودان الحديثة. بتمويل جيد من أندرو كارنيگي ومن خلال كتاباته الخاصة، قامت مجموعة روزڤلت الكبيرة بالبحث عن عينات لمؤسسة سميثسونيان والمتحف الأمريكي للتاريخ الطبيعي في نيويورك.[189]

المجموعة بقيادة الصياد المتعقب ر. كاننگام، كانت تضم علماء من مؤسسة سميثسونيان، وكان ينضم إليها من وقت لآخر فردريك سلوس، صياد الطرائد الكبيرة والمستكشف الشهير. وكان من بين المشاركين في البعثة كرمت روزڤلت، إدگار ألكسندر ميرنز، إدموند هيلر، وجون ألدن لورنگ.[190]

قام الفريق بقتل أو اصطياد 11.400 حيوان،[189] من الحشرات والخلد إلى أفراس النهر والفيلة. تضمنت الحيوانات الكبيرة البالغ عددها 1000 حيوانًا، 512 من الطرائد الكبيرة، بما في ذلك ستة من حيوانات وحيد القرن الأبيض النادرة. شُحنت أطنان من الجثث والجلود المملحة إلى واشنطن. استغرق الأمر سنوات لتجميعها جميعًا، وشاركت مؤسسة سميثسونيان عينات مكررة مع متاحف أخرى. وفيما يتعلق بالعدد الكبير من الحيوانات التي الحصول عليها، قال روزڤلت: "لا يمكن إدانتي إلا إذا كان وجود المتحف الوطني، والمتحف الأمريكي للتاريخ الطبيعي، وجميع مؤسسات الحيوانات المماثلة يجب إدانته".[191] كتب روزڤلت وصفًا تفصيليًا لرحلة السفاري في كتاب مسارات الطرائد الأفريقية، يروي فيه المطاردات المثيرة، والأشخاص الذين التقى بهم، والنباتات والحيوانات التي جمعها باسم العلم.[192]

بعد رحلة السفاري، سافر روزڤلت شمالًا لبدء جولة في أوروپا. توقف أولاً في مصر، وعلق بشكل إيجابي على الحكم البريطاني للمنطقة، معبرًا عن رأيه بأن مصر لم تكن مستعدة بعد للاستقلال.[193] رفض لقاء مع الپاپا بسبب خلاف حول مجموعة من الميثوديين الناشطين في روما. التقى فرانز يوزف امبراطور النمسا-المجر، والقيصر ڤلهلم الثاني ملك ألمانيا، وجورج الخامس ملك بريطانيا العظمى، وغيرهم من القادة الأوروپيين. في أوسلو بالنرويج، ألقى روزڤلت خطابًا دعا فيه إلى فرض قيود على التسلح البحري، وتعزيز المحكمة الدائمة للتحكيم، وتأسيس "عصبة السلام" بين القوى العالمية.[194]

كما ألقى محاضرة رومانز في أكسفورد، والتي ندد فيها بأولئك الذين سعوا إلى إيجاد أوجه تشابه بين تطور الحياة الحيوانية وتطور المجتمع. [195] على الرغم من أن روزڤلت حاول تجنب السياسة الداخلية، التقى بهدوء مع جيفورد پينشوت، الذي تحدث عن خيبة أمله من إدارة تافت.[196] أُجبر پينشوت على الاستقالة من منصب رئيس هيئة الغابات بعد خلافه مع وزير داخلية تافت، رتشارد بالينگر، الذي أعطى الأولوية للتنمية على الحفاظ على البيئة. عاد روزڤلت إلى الولايات المتحدة في يونيو 1910[197] حيث تم تكريمه بعد ذلك بوقت قصير بمأدبة غداء على سطح فندق والدورف-أستوريا في مدينة نيويورك استضافها نادي كامپ-فاير أوف أمريكا، الذي كان عضوًا فيه.[198]

في أكتوبر 1910، أصبح روزڤلت أول رئيس أمريكي يسافر على متن طائرة، وبقي محلقاً لأربع دقائق في طائرة من تصميم الأخوة رايت بالقرب من سانت لويس، مزوري.[199]

زيارته الثانية لمصر 1910

انقسام الحزب الجمهوري

Roosevelt had attempted to refashion Taft into a copy of himself, but he recoiled as Taft began to display his individuality. He was offended on election night when Taft indicated that his success had been possible not just through the efforts of Roosevelt, but also Taft's half-brother Charles P. Taft. Roosevelt was further alienated when Taft, intent on becoming his own man, did not consult him about cabinet appointments.[200] Roosevelt and other progressives were ideologically dissatisfied over Taft's conservation policies and his handling of the tariff when he concentrated more power in the hands of conservative party leaders in Congress.[201] Stanley Solvick argues that as President Taft abided by the goals and procedures of the "Square Deal" promoted by Roosevelt in his first term. The problem was that Roosevelt and the more radical progressives had moved on to more aggressive goals, such as curbing the judiciary, which Taft rejected.[202] Regarding radicalism and liberalism, Roosevelt wrote a British friend in 1911:

- Fundamentally it is the radical liberal with whom I sympathize. He is at least working toward the end for which I think we should all of us strive; and when he adds sanity in moderation to courage and enthusiasm for high ideals he develops into the kind of statesman whom alone I can wholeheartedly support.[203]

Roosevelt urged progressives to take control of the Republican Party at the state and local level and to avoid splitting the party in a way that would hand the presidency to the Democrats in 1912. To that end Roosevelt publicly expressed optimism about the Taft Administration after meeting with the president in June 1910.[204]

In August 1910, Roosevelt escalated the rivalry with a speech at Osawatomie, Kansas, which was the most radical of his career. It marked his public break with Taft and the conservative Republicans. Advocating a program he called the "New Nationalism", Roosevelt emphasized the priority of labor over capital interests, and the need to control corporate creation and combination. He called for a ban on corporate political contributions.[205] Returning to New York, Roosevelt began a battle to take control of the state Republican party from William Barnes Jr., Tom Platt's successor as the state party boss. Taft had pledged his support to Roosevelt in this endeavor, and Roosevelt was outraged when Taft's support failed to materialize at the 1910 state convention.[206] Roosevelt campaigned for the Republicans in the 1910 elections, in which the Democrats gained control of the House for the first time since 1892. Among the newly elected Democrats was New York state senator Franklin Delano Roosevelt, who argued that he represented his distant cousin's policies better than his Republican opponent.[207]

The Republican progressives interpreted the 1910 defeats as a compelling argument for the complete reorganization of the party in 1911.[208] Senator Robert M. La Follette of Wisconsin joined with Pinchot, William White, and California Governor Hiram Johnson to create the National Progressive Republican League; their objectives were to defeat the power of political bossism at the state level and to replace Taft at the national level.[209] Despite his skepticism of La Follette's new league, Roosevelt expressed general support for progressive principles. Between January and April 1911, Roosevelt wrote a series of articles for The Outlook, defending what he called "the great movement of our day, the progressive nationalist movement against special privilege, and in favor of an honest and efficient political and industrial democracy".[210] With Roosevelt apparently uninterested in running in 1912, La Follette declared his own candidacy in June 1911.[209] Roosevelt continually criticized Taft after the 1910 elections, and the break between the two men became final after the Justice Department filed an antitrust lawsuit against US Steel in September 1911; Roosevelt was humiliated by this suit because he had personally approved of an acquisition that the Justice Department was now challenging. However, Roosevelt was still unwilling to run against Taft in 1912; he instead hoped to run in 1916 against whichever Democrat beat Taft in 1912.[211]

Battling Taft over arbitration treaties

Taft was world leader for arbitration as a guarantee of world peace. In 1911 he and his Secretary of State Philander C. Knox negotiated major treaties with Great Britain and France providing that differences be arbitrated. Disputes had to be submitted to the Hague Court or another tribunal. These were signed in August 1911 but had to be ratified by a two-thirds vote of the Senate. Neither Taft nor Knox consulted with leaders of the Senate during the negotiating process. By then many Republicans were opposed to Taft, and the president felt that lobbying too hard for the treaties might cause their defeat. He made some speeches supporting the treaties in October, but the Senate added amendments Taft could not accept, killing the agreements.[212]

The arbitration issue revealed a deep philosophical dispute among American progressives. One faction, led by Taft looked to legal arbitration as the best alternative to warfare. Taft was a constitutional lawyer with a deep understanding of the legal issues.[213] Taft's political base was the conservative business community that largely supported peace movements before 1914. However, he failed to mobilize that base. The businessmen believed that economic rivalries were the cause of war, and that extensive trade led to an interdependent world that would make war a very expensive and useless anachronism.[214]

However, an opposing faction of progressives, led by Roosevelt, ridiculed arbitration as foolhardy idealism, and insisted on the realism of warfare as the only solution to serious international disputes. Roosevelt worked with his close friend Senator Henry Cabot Lodge to impose those amendments that ruined the goals of the treaties. Lodge's motivation was that he complained the treaties impinged too much on senatorial prerogatives.[215] Roosevelt, however, was acting to sabotage Taft's campaign promises.[216] At a deeper level, Roosevelt truly believed that arbitration was a naïve solution and the great issues had to be decided by warfare. The Rooseveltian approach incorporated a near-mystical faith of the ennobling nature of war. It endorsed jingoistic nationalism as opposed to the businessmen's calculation of profit and national interest.[217][218]

انتخابات 1912

Republican primaries and convention

In November 1911, a group of Ohio Republicans endorsed Roosevelt for the party's nomination for president; the endorsers included James R. Garfield and Dan Hanna. This endorsement was made by leaders of President Taft's home state. Roosevelt conspicuously declined to make a statement—requested by Garfield—that he would flatly refuse a nomination. Soon thereafter, Roosevelt said, "I am really sorry for Taft... I am sure he means well, but he means well feebly, and he does not know how! He is utterly unfit for leadership and this is a time when we need leadership." In January 1912, Roosevelt declared "if the people make a draft on me I shall not decline to serve".[219] Later that year, Roosevelt spoke before the Constitutional Convention in Ohio, openly identifying as a progressive and endorsing progressive reforms—even endorsing popular review of state judicial decisions.[220] In reaction to Roosevelt's proposals for popular overrule of court decisions, Taft said, "Such extremists are not progressives—they are political emotionalists or neurotics".[221]

Roosevelt began to envision himself as the savior of the Republican Party from defeat in the upcoming presidential election. In February 1912, Roosevelt announced in Boston, "I will accept the nomination for president if it is tendered to me. I hope that so far as possible the people may be given the chance through direct primaries to express who shall be the nominee.[222][223] Elihu Root and Henry Cabot Lodge thought that division of the party would lead to its defeat in the next election, while Taft believed that he would be defeated either in the Republican primary or in the general election.[224]

The 1912 primaries represented the first extensive use of the presidential primary, a reform achievement of the progressive movement.[225] The Republican primaries in the South, where party regulars dominated, went for Taft, as did results in New York, Indiana, Michigan, Kentucky, and Massachusetts. Meanwhile, Roosevelt won in Illinois, Minnesota, Nebraska, South Dakota, California, Maryland, and Pennsylvania. The greatest primary fight came in Ohio, Taft's base. Both the Taft and Roosevelt campaigns worked furiously, and La Follette joined in. Each team sent in big name speakers. Roosevelt's train went 1,800 miles back and forth in the one state, where he made 75 speeches. Taft's train went 3,000 miles criss-crossing Ohio and he made over 100 speeches.Roosevelt swept the state, convincing Roosevelt that he should intensify his campaigning, and letting Taft know he should work from the White House not the stump.[226] Only a third of the states held primaries; elsewhere the state organization chose the delegations to the national convention, and they favored Taft. The final credentials of the state delegates at the national convention were determined by the national committee, which was controlled by Taft men.[227][228]

Prior to the 1912 Republican National Convention in Chicago, Roosevelt expressed doubt about his prospects for victory, noting that Taft had more delegates and control of the credentials committee. His only hope was to convince party leaders that the nomination of Taft would hand the election to the Democrats, but party leaders were determined not to cede their leadership to Roosevelt.[229] The credentials committee awarded 235 contested delegates to Taft and 19 to Roosevelt. Taft won the nomination on the first ballot with 561 votes against 107 for Roosevelt and 41 for La Follette. Of the Roosevelt delegates, 344 refused to vote so they would not be committed to the Republican ticket.[230][231] Black delegates from the South played a key role: they voted heavily for Taft and put him over the top.[232] La Follette hoped that a deadlocked convention would result in his own nomination and refused to release his delegates to support Roosevelt.[230]

Roosevelt denounces the election

According to Lewis L. Gould, in 1912

Roosevelt saw Taft as the agent of "the forces of reaction and of political crookedness".... Roosevelt had become the most dangerous man in American history, said Taft, "because of his hold upon the less intelligent voters and the discontented." The Republican National Committee, dominated by the Taft forces, awarded 235 delegates to the president and 19 to Roosevelt, thereby ensuring Taft's renomination. Roosevelt believed himself entitled to 72 delegates from Arizona, California, Texas and Washington that had been given to Taft. Firm in his conviction that the nomination was being stolen from him, Roosevelt ....told cheering supporters that there was "a great moral issue" at stake and he should have "sixty to eighty lawfully elected delegates" added to his total....Roosevelt ended his speech declaring: "Fearless of the future; unheeding of our individual fates; with unflinching hearts and undimmed eyes; we stand at Armageddon, and we battle for the Lord!"[233]

تشكيل حزب ذَكـَر الأيل

Once his defeat at the Republican convention appeared probable, Roosevelt announced that he would "accept the progressive nomination on a progressive platform and I shall fight to the end, win or lose". At the same time, Roosevelt prophetically said, "My feeling is that the Democrats will probably win if they nominate a progressive".[234]

Roosevelt left the Republican Party and created the Progressive Party, structuring it as a permanent organization that would field complete tickets at the presidential and state level. The new party included many reformers, including Jane Addams. Although many Republican politicians had announced for Roosevelt before Taft won the nomination, he was stunned to discover that very few incumbent politicians followed him into the new party. The main exception was California, where the Progressive faction took control of the Republican Party. Loyalty to the old party was a powerful factor for incumbents; only five senators now supported Roosevelt.[235][236] Roosevelt's daughter Alice had a White House marriage to Congressman Nicholas Longworth, who represented Taft's base in Cincinnati. Roosevelt reassured him in 1912 that of course he had to endorse Taft. However, Alice was her father's biggest cheerleader—the public conflict between spouses ruined the marriage.[237]

The leadership of the new party included a wide range of reformers. Jane Addams campaigned vigorously for the new party as a breakthrough in social reform.[238] Gifford Pinchot represented the environmentalists and anti-trust crusaders. Publisher Frank Munsey provided much of the cash.[239] George W. Perkins, a leading Wall Street financier and senior partner of J.P. Morgan bank came from the efficiency movement. He handled the new party's finances efficiently but was deeply distrusted by many reformers.[240]

The new party was popularly known as the "Bull Moose Party" after Roosevelt told reporters, "I'm as fit as a bull moose".[241] At the 1912 Progressive National Convention, Roosevelt cried out, "We stand at Armageddon and we battle for the Lord." Governor Hiram Johnson controlled the California party, forcing out the Taft supporters. He was nominated as Roosevelt's running mate.[242]

Roosevelt's platform echoed his radical 1907–1908 proposals, calling for vigorous government intervention to protect the people from selfish interests:

To destroy this invisible Government, to dissolve the unholy alliance between corrupt business and corrupt politics is the first task of the statesmanship of the day.[243][244] This country belongs to the people. Its resources, its business, its laws, its institutions, should be utilized, maintained, or altered in whatever manner will best promote the general interest. This assertion is explicit... Mr. Wilson must know that every monopoly in the United States opposes the Progressive party... I challenge him... to name the monopoly that did support the Progressive party, whether... the Sugar Trust, the US Steel Trust, the Harvester Trust, the Standard Oil Trust, the Tobacco Trust, or any other... Ours was the only program to which they objected, and they supported either Mr. Wilson or Mr. Taft.[245]

Though many Progressive party activists in the North opposed the steady loss of civil rights for blacks, Roosevelt ran a "lily-white" campaign in the South. Rival all-white and all-black delegations from four southern states arrived at the Progressive national convention, and Roosevelt decided to seat the all-white delegations.[246][247][248] Nevertheless, he won few votes outside a few traditional Republican strongholds. Out of 1,100 counties in the South, Roosevelt won two counties in Alabama, one in Arkansas, seven in North Carolina, three in Georgia, 17 in Tennessee, two in Texas, one in Virginia, and none in Florida, Louisiana, Mississippi, or South Carolina.[249]

محاولة اغتياله

On October 14, 1912, while arriving at a campaign event in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, Roosevelt was shot from seven feet away in front of the Gilpatrick Hotel by a delusional saloonkeeper named John Flammang Schrank, who believed that the ghost of assassinated president William McKinley had directed him to kill Roosevelt.[250][251] The bullet lodged in his chest after penetrating his steel eyeglass case and passing through a 50-page-thick single-folded copy of the speech titled "Progressive Cause Greater Than Any Individual", which he was carrying in his jacket.[252] Schrank was immediately disarmed (by Czech immigrant Frank Bukovsky), captured, and might have been lynched had Roosevelt not shouted for Schrank to remain unharmed.[253][254] Roosevelt assured the crowd he was all right, then ordered police to take charge of Schrank and to make sure no violence was done to him.[255]

As an experienced hunter and anatomist, Roosevelt correctly concluded that since he was not coughing blood, the bullet had not reached his lung. He declined suggestions to go to the hospital immediately and instead delivered a 90-minute speech with blood seeping into his shirt.[256] His opening comments to the gathered crowd were, "Ladies and gentlemen, I don't know whether you fully understand that I have just been shot, but it takes more than that to kill a Bull Moose."[257] Only after finishing his address did he accept medical attention.

Subsequent probes and an x-ray showed that the bullet had lodged in Roosevelt's chest muscle but did not penetrate the pleura. Doctors concluded that it would be less dangerous to leave it in place than to attempt to remove it, and Roosevelt carried the bullet with him for the rest of his life.[258][259] Both Taft and Democratic nominee Woodrow Wilson suspended their own campaigning until Roosevelt recovered and resumed his. When asked if the shooting would affect his election campaign, he said to the reporter "I'm fit as a bull moose." The bull moose became a symbol of both Roosevelt and the Progressive Party, and it often was referred to as simply the Bull Moose Party. He spent two weeks recuperating before returning to the campaign trail. He later wrote a friend about the bullet inside him, "I do not mind it any more than if it were in my waistcoat pocket."[260]

Democratic victory

After the Democrats nominated Governor Woodrow Wilson of New Jersey, Roosevelt did not expect to win the general election, as Wilson had compiled a record attractive to many progressive Democrats who might have otherwise considered voting for Roosevelt.[261] Roosevelt still campaigned vigorously, and the election developed into a two-person contest despite Taft's quiet presence in the race. Roosevelt respected Wilson, but the two differed on various issues; Wilson opposed any federal intervention regarding women's suffrage or child labor (he viewed these as state issues) and attacked Roosevelt's tolerance of large businesses.[262]