مصر القديمة

مصر القديمة | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ح. 3150 ق.م.–332/30 ق.م. [أ] | |||||||||

خريطة مصر القديمة، توضح المدن والمواقع الرئيسية في فترة الأسرات (ح. 3150 ق.م. حتى 30 ق.م.). | |||||||||

| Capital | انظر قائمة العواصم التاريخية لمصر | ||||||||

| الحقبة التاريخية | التاريخ القديم | ||||||||

• Established | ح. 3150 ق.م. | ||||||||

| ح. 3150 ق.م. – 2686 ق.م. | |||||||||

| 2686 ق.م. – 2181 ق.م. | |||||||||

| 2134 ق.م. – 1690 ق.م. | |||||||||

| 1549 ق.م. – 1078/77 ق.م. [ب] | |||||||||

| 664 ق.م. – 332 ق.م. | |||||||||

| 332 ق.م. – 30 ق.م. | |||||||||

• Disestablished | 332/30 ق.م. [أ] | ||||||||

| |||||||||

مصر القديمة هي حضارة قديمة في شمال شرق أفريقيا. كانت متمركزة على امتداد الروافد السفلية لنهر النيل، الواقعة ضمن أراضي مصر الحديثة. تلت الحضارة المصرية القديمة فترة مصر قبل الأسرات واندمجت حوالي عام 3100 ق.م. (وفقاً للتسلسل الزمني المصري التقليدي) مع توحيد مصر العليا والسفلى تحت حكم الملك مينا (غالباً ما يخلط بينه وبين نارمر).[1] تكشّف تاريخ مصر القديمة على هيئة سلسلة من الدول المستقرة التي تخلّلتها فترات من عدم الاستقرار النسبي تُعرف باسم "الفترات الوسيطة". وتنقسم الدول المختلفة إلى ثلاث فئات: الدولة القديمة في العصر البرونزي المبكر، الدولة لاوسطى في العصر البرونزي الأوسط، و الدولة الحديثة في العصر البرونزي المتأخر.

بلغت مصر القديمة ذروة قوتها في عهد الدولة الحديثة، حيث حكمت جزءاً كبيراً من النوبة وجزءاً كبيراً من الشام. وبعد هذه الفترة، دخلت مصر القديمة عصراً من الانحدار البطيء. وخلال تاريخها، تعرضت مصر القديمة للغزو أو الاجتياح من قبل عدد من القوى الأجنبية، بما في ذلك الهكسوس، النوبيون، الآشوريون، الفرس الأخمينيون، والمقدونيون تحت حكم الإسكندر الأكبر. وحكمت المملكة الپطلمية اليونانية، التي تشكلت في أعقاب وفاة الإسكندر، حتى عام 30 ق.م، عندما سقطت تحت حكم كليوپاترا في يد الامبراطورية الرومانية وأصبحت مصر مقاطعة رومانية.[2] ظلت مصر تحت الحكم الرومانية حتى عام 642 م، عندما فتحتها الخلفاء الراشدون.

كان نجاح الحضارة المصرية القديمة يرجع جزئياً إلى قدرتها على التكيف مع ظروف وادي نهر النيل للزراعة. فقد أدى الفيضان المتوقع لنهر النيل والري المتحكم فيه للوادي الخصيب إلى إنتاج محاصيل فائضة، وهو ما دعم كثافة سكانية أكبر، وتطوراً اجتماعياً وثقافياً. وبفضل الموارد الفائضة، رعت الإدارة استغلال المعادن في الوادي والمناطق الصحراوية المحيطة، والتطوير المبكر لنظام كتابة مستقل، وتنظيم البناء الجماعي والمشاريع الزراعية، والتجارة مع المناطق المحيطة، وجيش كان يهدف إلى تأكيد الهيمنة المصرية. كان تحفيز وتنظيم هذه الأنشطة يتم من خلال بيروقراطية النخبة من الكتبة والزعماء الدينيين والإداريين تحت سيطرة الفرعون، الذين عملوا على ضمان تعاون ووحدة الشعب المصري في سياق نظام متقن من المعتقدات الدينية.[3]

تشمل الإنجازات العديدة التي حققها قدماء المصريين التعدين، المسح، وتقنيات البناء التي دعمت بناء الأهرامات الضخمة، المعابد، المسلات؛ نظام الرياضيات، نظام الطب العملي والفعال، أنظمة الري، وتقنيات الإنتاج الزراعي، وأولى القوارب الخشبية المعروفة،[4] تقنية الفخار وتقنية تشكيل الزجاج، وأشكال جديدة من الأدب، وأقدم معاهدة سلام معروفة، أبرمت مع الحيثيين.[5] لقد تركت مصر القديمة إرثاً دائماً. فقد نُسخ فنها وعمارتها على نطاق واسع، ونُقلت آثارها للدراسة والعرض أو الرغبة في اقتنائها في أقاصي العالم. ولقد ألهمت أطلالها الضخمة خيال الرحالة والكتاب لآلاف السنين. وقد أدى الاحترام الجديد للآثار والحفريات في العصر الحديث المبكر من قبل الأوروپيين والمصريين إلى إجراء تحقيق علمي في الحضارة المصرية وتقدير أكبر لإرثها الثقافي.[6]

التاريخ

لقد كان نهر النيل شريان الحياة لواديه طوال معظم فترتات تاريخ البشرية.[7] أعطت سهول النيل الخصبة للبشر الفرصة لتطوير اقتصاد زراعي مستقر ومجتمع أكثر تطوراً ومركزية أصبح حجر الزاوية في تاريخ الحضارة الإنسانية.[8] بدأ البشر الرحل الذين يعتمدون على الصيد وجمع الثمار العيش في وادي النيل حتى نهاية العصر الپلایستوسيني الأوسط منذ حوالي 120.000 سنة. وبحلول أواخر العصر الحجري القديم، أصبح مناخ شمال أفريقيا القاحل حاراً وجافاً بشكل متزايد، مما أجبر سكان المنطقة على التركيز على امتداد منطقة النهر.

فترة قبل الأسرات

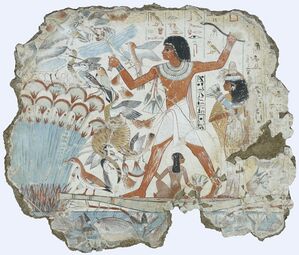

في عصر قبل الأسرات وعصر الأسرات المبكرة، كان مناخ مصر أقل جفافاً بكثير مما هو عليه اليوم. كانت مناطق كبيرة من مصر مغطاة بالساڤانا المشجرة وترعى فيها قطعان الحافريات العاشبة. كانت أوراق الشجر والحيوانات أكثر غزارة في جميع المناطق المحيطة، وكانت منطقة النيل تدعم أعداداً كبيرة من الطيور المائية. كان الصيد شائعاً بين المصريين، وهذه أيضاً هي الفترة التي تم فيها تدجين العديد من الحيوانات لأول مرة.[9]

بحلول عام 5500 ق.م. تقريباً، تطورت القبائل الصغيرة التي تعيش في وادي النيل إلى سلسلة من الثقافات التي أظهرت سيطرة قوية على الزراعة وتربية الحيوانات، ويمكن التعرف عليها من خلال الفخار والأغراض الشخصية، مثل الأمشاط والأساور والخرز. كانت أكبر هذه الثقافات المبكرة في مصر العليا (الجنوبية) هي ثقافة البداري، والتي نشأت على الأرجح في الصحراء الغربية؛ كانت معروفة بخزفها عالي الجودة، وأدواتها الحجرية، واستخدامها للنحاس.[10]

تبعت البداري ثقافة نقادة: نقادة الأولى (العمراتية)، ونقادة الثانية (جرزة)، ونقادة الثالثة (السماعين).[11] جلبت هذه الثقافات عدداً من التحسينات التكنولوجية. في وقت مبكر من فترة نقادة الأولى، استورد المصريون في عصر قبل الأسرات حجر السبج من إثيوپيا، وكان يستخدم لتشكيل الشفرات وأشياء أخرى من الرقائق.[12][13] تأسست التجارة المتبادلة مع الشام خلال فترة نقادة الثانية (3600-3350 ق.م. تقريباً)؛ وكانت هذه الفترة أيضاً بداية التجاربة مع بلاد الرافدين، والتي استمرت حتى فترة الأسرات المبكرة وما بعدها.[14] على مدى فترة تبلغ حوالي 1000 عام، تطورت ثقافة نقادة من عدد قليل من المجتمعات الزراعية الصغيرة إلى حضارة قوية كان قادتها يسيطرون بشكل كامل على شعب وموارد وادي النيل.[15] من خلال إنشاء مركز قوة في نخن (باليونانية، هيراكونپوليس)، ولاحقاً في أبيدوس، وسع زعماء نقادة الثالث سيطرتهم على مصر شمالاً على امتداد النيل.[16] كما قاموا بالتجارة مع النوبة جنوباً، وواحات الصحراء الغربية غرباً، وثقافات شرق المتوسط والشرق الأدنى شرقاً.[17][when?]

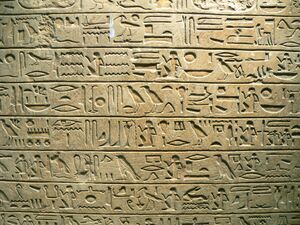

صنعت ثقافة نقادة مجموعة متنوعة من السلع المادية، والتي تعكس القوة والثروة المتزايدة للنخبة، فضلاً عن العناصر ذات الاستخدام الشخصي المجتمعي، والتي تضمنت الأمشاط والتماثيل الصغيرة والفخار المطلي والمزهريات الحجرية المزخرفة عالية الجودة ولوحات التجميل والمجوهرات المصنوعة من الذهب واللازورد والعاج. كما طوروا أيضاً طلاء خزفي يُعرف بالفايانس المصري، والذي استُخدم جيدًا في العصر الروماني لتزيين الكؤوس والتمائم والتماثيل الصغيرة.[18][19] خلال مرحلة قبل الأسرات المتأخرة، بدأت ثقافة نقادة في استخدام الرموز المكتوبة التي تطورت في نهاية المطاف إلى نظام كامل من الهيروغليفية لكتابة اللغة المصرية القديمة.[20]

عصر الأسرات المبكرة (ح. 3150–2686 ق.م.)

كانت عصر الأسرات المبكرة معاصراً تقريباً للحضارة السومرية-الأكادية المبكرة في بلاد الرافدين وعيلام القديمة. وقد قام الكاهن المصري مانيتو في القرن الثالث ق.م. بتقسيم السلسلة الطويلة من الملوك من مينا إلى عصره خلال 30 أسرة، وهو النظام الذي لا يزال مستخدماً حتى اليوم. وقد بدأ تأريخه الرسمي بالملك المسمى مينا، والذي يُعتقد أنه وحد مملكتي مصر العليا والسفلى.[21]

لقد حدث الانتقال إلى الدولة الموحدة بشكل تدريجي أكثر مما صوره الكتاب المصريون القدماء، ولا يوجد سجل معاصر لمينا. ومع ذلك، يعتقد بعض العلماء الآن أن مينا الأسطوري ربما كان الملك نارمر، الذي صورته لوحة نارمر الاحتفالية مرتدياً الزي الملكي، في عمل رمزي للتوحيد.[23] في عصر الأسرات المبكرة، الذي بدأ حوالي 3000 ق.م، عزز أول ملوك الأسرات سيطرتهم على مصر السفلى من خلال تأسيس عاصمة في منف، والتي تمكنوا بواسطتها من السيطرة على القوى العاملة والزراعة في منطقة الدلتا الخصبة، بالإضافة إلى طرق التجارة المربحة والحيوية إلى الشام. انعكست القوة والثروة المتزايدة للملوك خلال عصر الأسرات المبكرة في مقابرهم المزخرفة بالمصاطب ومباني العبادة الجنائزية في أبيدوس، والتي كانت تستخدم للاحتفال بالملك المؤله بعد وفاته.[24] وعملت المؤسسة الملكية القوية التي طورها الملوك على إضفاء الشرعية على سيطرة الدولة على الأرض والعمالة والموارد التي كانت ضرورية لبقاء ونمو الحضارة المصرية القديمة.[25]

الدولة القديمة (2686–2181 ق.م.)

شهدت الدولة القديمة تقدم كبير في الهندسة المعمارية والفن والتكنولوجيا، مدفوعاً بزيادة الإنتاج الزراعي والنمو السكاني الناتج عنها، والذي أصبح ممكناً بفضل الإدارة المركزية المتطورة.[26] تم تشييد بعض من أهم إنجازات مصر القديمة، مثل أهرامات الجيزة وأبو الهول العظيم، خلال عصر الدولة القديمة. وتحت إشراف الوزير، قام المسؤولون الحكوميون بجمع الضرائب، وتنسيق مشاريع الري لتحسين عائدات المحاصيل، وتجنيد الفلاحين للعمل في مشاريع البناء، وتأسيس نظام عدالة جنائية للحفاظ على السلام والنظام.[27]

مع تزايد أهمية الإدارة المركزية في مصر، نشأت طبقة جديدة من الكتبة والمسؤولين المتعلمين الذين منحهم الملك عقارات مقابل خدماتهم. كما قدم الملوك منحاً للأراضي لطقوسهم الجنائزية والمعابد المحلية، لضمان حصول هذه المؤسسات على الموارد اللازمة لعبادة الملك بعد وفاته. يعتقد العلماء أن خمسة قرون من هذه الممارسات أدت ببطء إلى تآكل الحيوية الاقتصادية لمصر، وأن الاقتصاد لم يعد قادراً على تحمل تكاليف إدارة مركزية كبيرة.[28] مع تضاؤل سلطة الملوك، بدأ حكام المناطق الذين يطلق عليهم نومارخ في تحدي سيادة منصب الملك. هذا، إلى جانب الجفاف الشديد بين عامي 2200 و2150 ق.م،[29] ويُعتقد أن هذا كان سبباً في دخول البلاد فترة المجاعة والصراع التي استمرت 140 عاماً والمعروفة باسم الفترة الانتقالية الأولى.[30]

الفترة الانتقالية الأولى (2181–2055 ق.م.)

بعد انهيار الحكومة المركزية المصرية في نهاية عصر الدولة القديمة، لم يعد بوسع الإدارة دعم أو استقرار اقتصاد البلاد. ولم يعد بوسع حكام الأقاليم الاعتماد على الملك للمساعدة في أوقات الأزمات، وتصاعدت أزمة نقص الغذاء والنزاعات السياسية التي أعقبت ذلك إلى مجاعات وحروب أهلية محدودة. لكن على الرغم من المشاكل الصعبة، استخدم الزعماء المحليون، الذين لم يكونوا مدينين للملك بأي جزية، استقلالهم الجديد لتأسيس ثقافة مزدهرة في الأقاليم. وبمجرد السيطرة على مواردها الخاصة، أصبحت الأقاليم أكثر ثراءً اقتصادياً - وهو ما تجلى في عمليات دفن أكبر وأفضل بين جميع الطبقات الاجتماعية.[31] وفي نوبات من الإبداع، تبنى الحرفيون الإقليميون الزخارف الثقافية التي كانت مقتصرة في السابق على أفراد العائلة المالكة في الدولة القديمة، وطور الكتبة أساليب أدبية تعبر عن تفاؤل وأصالة تلك الفترة.[32]

وبعد أن تحرروا من ولائهم للملك، بدأ الحكام المحليون في التنافس مع بعضهم البعض من أجل السيطرة الإقليمية والسلطة السياسية. وبحلول عام 2160 ق.م، سيطر حكام هركليوپوليس على مصر السفلى في الشمال، بينما سيطرت عشيرة منافسة مقرها في طيبة، وهي عائلة إنتف، على صعيد مصر في الجنوب. ومع نمو قوة عائلة إنتف وتوسيع سيطرتها شمالاً، أصبح الصدام بين العائلتين المتنافستين أمراً لا مفر منه. وفي حوالي عام 2055 ق.م، هزمت قوات طيبة الشمالية بقيادة نبحپترع منتوحوتپ الثاني حكام هركليوپوليس، وأعادوا توحيد الأرضين. وقد دشنوا فترة من النهضة الاقتصادية والثقافية المعروفة بالدولة الوسطى.[33]

الدولة الوسطى (2134–1690 BC)

أعاد ملوك الدولة الوسطى الاستقرار والازدهار للبلاد، مما أدى إلى تحفيز انتعاش الفن والأدب ومشاريع البناء الضخمة.[36] حكم منتوحوتپ وخلفاؤه من الأسرة الحادية عشرة من طيبة، لكن الوزير أمنمحات الأول، عند توليه الحكم في بداية االأسرة الثانية عشرة حوالي عام 1985 ق.م، نقل العاصمة الملكية إلى إتج تاوي الواقعة في الفيوم.[37] ومن إتج تاوي، شرع ملوك الأسرة الثانية عشرة في تنفيذ خطة بعيدة النظر لاستصلاح الأراضي والري لزيادة الإنتاج الزراعي في المنطقة. علاوة على ذلك، استعاد الجيش الأراضي في النوبة التي كانت غنية بالمحاجر ومناجم الذهب، بينما بنى العمال حصناً دفاعياً في شرق الدلتا، أطلقوا عليه اسم "أسوار الحاكم"، للدفاع ضد الهجوم الأجنبي.[38]

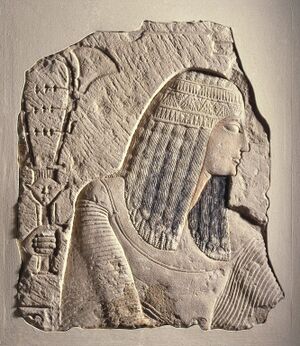

ومع تأمين الملوك للبلاد عسكرياً وسياسياً ومع وجود ثروات زراعية ومعدنية هائلة تحت تصرفهم، ازدهرت أعداد السكان وازدهرت الفنون والدين في البلاد. وعلى النقيض من مواقف الدولة القديمة النخبوية تجاه الآلهة، أظهرت الدولة الوسطى زيادة في التعبير عن التقوى الشخصية.[39] تميز أدب الدولة الوسطى بموضوعات وشخصيات متطورة مكتوبة بأسلوب واثق وبليغ.[32] لقد نجحت النقوش البارزة والپورتريهية في تلك الفترة في التقاط تفاصيل دقيقة وفردية وصلت إلى مستويات جديدة من التطور التقني.[40]

سمح آخر حكام الدولة الوسطى، أمنمحات الثالث، للمستوطنين الكنعانيين الناطقين بالسامية من الشرق الأدنى بالدخول إلى منطقة الدلتا لتوفير قوة عاملة كافية لحملاته النشطة بشكل خاص في التعدين والبناء. ومع ذلك، فإن أنشطة البناء والتعدين الطموحة هذه، جنباً إلى جنب مع فيضانات النيل الشديدة في وقت لاحق من حكمه، أدت إلى إجهاد الاقتصاد وتسريع الانحدار البطيء في الفترة الانتقالية الثانية خلال عهد الأسرتين الثالثة عشرة والرابعة عشرة. خلال هذا الأفول، بدأ المستوطنون الكنعانيون في تولي سيطرة أكبر على منطقة الدلتا، ووصلوا في النهاية إلى السلطة باسم الهكسوس.[41]

الفترة الانتقالية الثانية (1674–1549 ق.م.) والهكسوس

حوالي عام 1785 ق.م، ومع ضعف قوة ملوك الدولة الوسطى، استولى شعب من غرب آسيا يُدعى الهكسوس، والذي كان قد استقر بالفعل في الدلتا، على مصر وأنشأ عاصمته في أڤاريس، مما أجبر الحكومة المركزية السابقة على التراجع إلى طيبة. كان الملك يُعامل كتابع وكان من المتوقع أن يدفع الجزية.[42] احتفظ الهكسوس ('الحكام الأجانب') بنماذج الحكم المصرية وعرفوا أنفسهم كملوك، وبالتالي دمجوا العناصر المصرية في ثقافتهم. لقد أدخلوا هم وغيرهم من الغزاة أدوات حربية جديدة إلى مصر، أبرزها القوس المركب والعجلة الحربية التي تجرها الخيول.[43]

بعد الانسحاب جنوباً، وجد ملوك طيبة الأصليون أنفسهم محاصرين بين الهكسوس الكنعانيين الذين يحكمون الشمال وحلفاء الهكسوس من النوبيين، مملكة كوش، جنوباً. وبعد سنوات من التبعية، جمعت طيبة ما يكفي من القوة لتحدي الهكسوس في صراع استمر لأكثر من 30 عاماً، حتى 1555 ق.م.[42] في النهاية، تمكن الملكان سقنن رع تاو الثاني وكاموس من هزيمة النوبيين في جنوب مصر، لكنهما فشلا في هزيمة الهكسوس. ووقعت هذه المهمة على عاتق أحمس الأول، خليفة كاموس، الذي شن بنجاح سلسلة من الحملات التي قضت على وجود الهكسوس في مصر بشكل دائم. وأسس أسرة حاكمة جديدة، وفي الدولة الحديثة التي تلت ذلك، أصبحت المؤسسة العسكرية أولوية أساسية للملوك، الذين سعوا إلى توسيع حدود مصر وحاولوا السيطرة على الشرق الأدنى.[44]

الدولة الحديثة (1549–1069 ق.م.)

أسس ملوك الدولة الحديثة فترة من الرخاء غير المسبوق من خلال تأمين حدودهم وتعزيز العلاقات الدبلوماسية مع جيرانهم، بما في ذلك مملكة ميتاني، آشور، وكنعان. وقد أدت الحملات العسكرية التي شنها تحتمس الأول وحفيده تحتمس الثالث إلى توسيع نفوذ الفراعنة إلى أكبر إمبراطورية شهدتها مصر على الإطلاق.

بين عهديهما، أطلقت حتشپسوت، التي أعلنت نفسها فرعوناً، العديد من مشاريع البناء، بما في ذلك ترميم المعابد التي دمرها الهكسوس، وأرسلت بعثات تجارية إلى بلاد البنط وسيناء.[45] عندما توفي تحتمس الثالث عام 1425 ق.م، كانت النفوذ المصري يمتد من نيا في شمال غرب سوريا حتى شلال النيل الرابع في النوبة، مما عزز الولاءات ومكن من الوصول إلى الواردات الهامة مثل البرونز والخشب.[46]

بدأ ملوك الدولة الحديثة حملة بناء واسعة النطاق للترويج للإله آمون، الذي كانت عبادته المتنامية مقرها الكرنك. كما بنوا المعالم لتمجيد إنجازاتهم الخاصة، سواء كانت حقيقية أو خيالية. ويعد معبد الكرنك أكبر معبد مصري بُني على الإطلاق.[47]

حوالي عام 1350 ق.م، هُدِّد استقرار الدولة الحديثة عندما اعتلى أمنحوتپ الرابع العرش وبدأ سلسلة من الإصلاحات الجذرية والفوضوية. فبعد أن غيَّر اسمه إلى أخناتون، أعلن عن إله الشمس الغامض آتون باعتباره الإله الأعلى، وقمع عبادة معظم الآلهة الأخرى، ونقل العاصمة إلى مدينة أخيتاتون الجديدة (العمارنة المعاصرة).[48] كان مخلصاً لدينه الجديد وأسلوبه الفني. بعد وفاته، سرعان ما تم التخلي عن عبادة آتون واستعادة النظام الديني التقليدي. عمل الملوك اللاحقون، توت عنخ آمون وأي وحورمحب، على محو كل ذكر لبدعة أخناتون، المعروفة حالياً بحقبة العمارنة.[49]

حوالي عام 1279 ق.م، اعتلى رمسيس الثاني، المعروف أيضاً برمسيس الأكبر، العرش، واستمر في بناء المزيد من المعابد، وإقامة المزيد من التماثيل والمسلات، وإنجاب المزيد من الأطفال أكثر من أي فرعون آخر في التاريخ.[ت] كان رمسيس الثاني قائداً عسكرياً جريئاً، حيث قاد جيشه ضد الحثيين في معركة قادش (في سوريا المعاصرة)، وبعد القتال حتى الوصول إلى طريق مسدود، وافق أخيراً على أول معاهدة سلام مسجلة، حوالي عام 1258 ق.م.[50]

ومع ذلك، فإن ثروة مصر جعلتها هدفاً مغرياً للغزو، وخاصة من قبل الأمازيغ الليبيين غرباً، وشعوب البحر، وهو اتحاد مفترض من البحارة من بحر إيجه.[ث] في البداية، كان الجيش قادراً على صد هذه الغزوات، لكن مصر فقدت السيطرة في النهاية على أراضيها المتبقية في جنوب كنعان، وسقط الكثير منها في أيدي الآشوريين. تفاقمت آثار التهديدات الخارجية بسبب المشاكل الداخلية مثل الفساد وسرقة المقابر والاضطرابات المدنية. بعد استعادة سلطتهم، جمع كبار كهنة معبد آمون في طيبة مساحات شاسعة من الأراضي والثروات، وتسببت سلطتهم الموسعة في تقسيم البلاد أثناء الفترة الانتقالية الثالثة.[51]

الفترة الانتقالية الثالثة (1069–653 ق.م.)

بعد وفاة رمسيس الحادي عشر عام 1078 ق.م، تولى سمندس السلطة على الجزء الشمالي من مصر، وحكم من مدينة تانيس. أما الجنوب فقد كان تحت سيطرة كبار كهنة آمون الذين لم يعترفوا بسمندس إلا اسمياً.[52] خلال هذه الفترة، كان الليبيون يستقرون في غرب الدلتا، وبدأ زعماء هؤلاء المستوطنين في زيادة استقلاليتهم. سيطر الأمراء الليبيون على الدلتا تحت حكم شيشنق الأول عام 945 ق.م، وأسسوا ما يسمى بالأسرة الليبية أو البوباستية التي حكمت قرابة 200 سنة. كما سيطر شيشنق على جنوب مصر من خلال وضع أفراد عائلته في مناصب كهنوتية هامة. بدأت السيطرة الليبية في التراجع مع ظهور أسرة منافسة في ليونتوپوليس بمنطقة الدلتا، وهدد الكوش من الجنوب.

حوالي عام 727 ق.م، غزا الملك الكوشي پييى الشمال، واستولى على السيطرة طيبة وفي النهاية الدلتا، مما أدى إلى تأسيس الأسرة الخامسة والعشرين.[54] في عهد الأسرة الخامسة والعشرين، أنشأ الفرعون طهارقا إمبراطورية تكاد تكون بحجم الدولة الحديثة. قام فراعنة الأسرة الخامسة والعشرين ببناء أو ترميم المعابد والآثار في جميع أنحاء وادي النيل، بما في ذلك منف والكرنك وكاوة وجبل البركل.[55] خلال هذه الفترة، شهد وادي النيل أول بناء موسع للأهرامات النوبية (العديد منها في السودان الحديث) منذ عصر الدولة الوسطى.[56][57][58]

تراجعت هيبة مصر بشكل كبير نحو نهاية الفترة الانتقالية الثالثة. فقد وقع حلفاؤها الأجانب تحت دائرة النفوذ الآشوري، وبحلول عام 700 ق.م. أصبحت الحرب بين الدولتين حتمية. وفي الفترة بين عامي 671 و667 ق.م. بدأ الآشوريون في غزو مصر. وكانت فترة حكم كل من طهارقا وخليفته تنتامون مليئة بالصراع المستمر مع الآشوريين، الذين حققت مصر ضدهم عدة انتصارات. وفي النهاية، تمكن الآشوريون من دفع الكوش إلى النوبة، واحتلوا منف، ونهبوا معابد طيبة.[59]

العصر المتأخر (653–332 ق.م.)

ترك الآشوريون السيطرة على مصر لسلسلة من التابعين الذين أصبحوا معروفين باسم ملوك سايت من الأسرة السادسة والعشرين. بحلول عام 653 ق.م، تمكن الملك السايتي پسامتيك الأول من الإطاحة بالآشوريين بمساعدة المرتزقة اليونانيين، الذين تم تجنيدهم لتشكيل أول قوات بحرية مصرية. توسع النفوذ اليوناني بشكل كبير حيث أصبحت الدولة-المدينة نقراطيس موطناً لليونانيين في دلتا النيل. شهد ملوك سايت المتمركزون في العاصمة الجديدة سايس انتعاشاً قصير الأجل لكنه قوي في الاقتصاد والثقافة، لكن في عام 525 ق.م، بدأت الإمبراطورية الفارسية بقيادة قمبيز الثاني غزوها لمصر، وهزمت في النهاية الفرعون پسامتيك الثالث في معركة پلوزيوم. ثم تولى قمبيز الثاني اللقب الرسمي للفرعون، لكنه حكم مصر من فارس، تاركاً مصر تحت سيطرة الساتراپ. تميز القرن الخامس ق.م. ببضع ثورات ضد الفرس، لكن مصر لم تتمكن أبداً من الإطاحة بالفرس حتى نهاية القرن.[60]

بعد ضمها من قبل الفرس، انضمت مصر إلى قبرص وفينيقيا في الساتراپية السادسة التابعة للإمبراطورية الفارسية الأخمينية. انتهت هذه الفترة الأولى من الحكم الفارسي لمصر، والمعروفة أيضاً بالأسرة السابعة والعشرين، عام 402 ق.م، عندما استعادت مصر استقلالها تحت سلسلة من الأسرات المحلية. أثبتت آخر هذه الأسرات، الأسرة الثلاثون، أنها آخر أسرة ملكية محلية في مصر القديمة، وانتهت بحكم نخت أنبو الثاني. بدأت عملية استعادة قصيرة للحكم الفارسي، والمعروفة أحياناً بالأسرة الحادية والثلاثين، عام 343 ق.م، لكن بعد فترة وجيزة، عام 332 ق.م، سلم الحاكم الفارسي مازاسيز مصر إلى الإسكندر الأكبر دون قتال.[61]

الفترة الپطلمية (332–30 ق.م.)

عام 332 ق.م، غزا الإسكندر الأكبر مصر دون مقاومة تذكر من الفرس، ورحب به المصريون باعتباره منقذاً لهم. كانت الإدارة التي أسسها خلفاء الإسكندر، المملكة الپطلمية المقدونية، مبنية على نموذج مصري ومقرها في العاصمة الجديدة الإسكندرية. أظهرت المدينة قوة وهيبة الحكم الهليني، وأصبحت مركزاً للتعلم والثقافة، بما في ذلك مكتبة الإسكندرية الشهيرة كجزء من المتحف القديم.[62] أضاء فنار الإسكندرية الطريق للعديد من السفن التي حافظت على تدفق التجارة عبر المدينة، حيث جعل الپطالمة التجارة والمشاريع المدرة للدخل، مثل تصنيع ورق البردي، من أولوياتهم القصوى.[63]

لم تحل الثقافة الهيلينية محل الثقافة المصرية الأصلية، حيث دعم الپطالمة التقاليد العريقة في محاولة لتأمين ولاء عامة الشعب. لقد بنوا معابد جديدة على الطراز المصري، ودعموا الطوائف التقليدية، وصوروا أنفسهم كفراعنة. اندمجت بعض التقاليد، حيث دُمجت الآلهة اليونانية والمصرية في آلهة متآلفة، مثل سراپيس، وتأثرت الأشكال اليونانية الكلاسيكية للنحت بالزخارف المصرية التقليدية. وعلى الرغم من جهودهم لاسترضاء المصريين، فقد واجه الپطالمة تحدياً من التمرد المحلي، والتنافسات العائلية المريرة، والغوغاء الأقوياء في الإسكندرية الذين تشكلوا بعد وفاة پطليموس الرابع.[64] بالإضافة إلى ذلك، نظراً لاعتماد روما بشكل أكبر على واردات الحبوب من مصر، فقد اهتم الرومان كثيراً بالوضع السياسي في البلاد. أدت الثورات المصرية المستمرة، والسياسيون الطموحون، والمعارضون الأقوياء من الشرق الأدنى إلى عدم استقرار هذا الوضع، مما دفع روما إلى إرسال قوات لتأمين البلاد كمقاطعة تابعة لإمبراطوريتها.[65]

الفترة الرومانية (30 ق.م. – م641)

عام 30 ق.م. أصبحت مصر مقاطعة تابعة للإمبراطورية الرومانية، بعد هزيمة ماركوس أنطونيوس والپطلمية|الملكة الپطلمية كليوپاترا السابعة على يد أوكتاڤيوس (الإمبراطور الروماني أغسطس قيصر لاحقاً) في معركة أكتيوم. اعتمد الرومان بشكل كبير على شحنات الحبوب المصرية، وقام الجيش الروماني، تحت سيطرة حاكم معين من قبل الإمبراطور، بقمع التمردات، وفرض بصرامة تحصيل الضرائب الباهظة، ومنع هجمات قطاع الطرق، والتي أصبحت مشكلة سيئة السمعة خلال تلك الفترة.[66] أصبحت الإسكندرية مركزاً متزايد الأهمية على طريق التجارة مع الشرق، حيث كان الطلب على الكماليات الغريبة مرتفعاً في روما.[67]

على الرغم من أن الرومان كان لديهم موقف أكثر عدائية من الإغريق تجاه المصريين، إلا أن بعض التقاليد مثل التحنيط وعبادة الآلهة التقليدية استمرت.[68] ازدهر فن رسم المومياوات، وصوَّر بعض الأباطرة الرومان أنفسهم كفراعنة، وإن لم يكن ذلك بالقدر الذي فعله الپطالمة. عاش الأباطرة الرومان خارج مصر ولم يؤدوا الوظائف الاحتفالية للملكية المصرية. أصبحت الإدارة المحلية على الطراز الروماني ومغلقة أمام المصريين الأصليين.[68]

منذ منتصف القرن الأول الميلادي، ترسخت المسيحية في مصر، وكان يُنظر إليها في الأصل على أنها طائفة أخرى يمكن قبولها. ومع ذلك، كانت ديانة متشددة تسعى إلى كسب معتنقيها من الديانات المصرية واليونانية-الرومانية الوثنية، وهددت التقاليد الدينية الشعبية. أدى هذا إلى اضطهاد معتنقي المسيحية، وبلغت ذروتها في عمليات التطهير الكبرى التي قام بها ديوكلتيانوس بدءاً من عام 303، لكن المسيحية انتصرت في النهاية.[69] عام 391، أصدر الإمبراطور المسيحي ثيودوسيوس تشريعاً يحظر الطقوس الوثنية ويغلق المعابد.[70] أصبحت الإسكندرية مسرحاً لأعمال شغب كبيرة ضد الوثنيين مع تدمير التصوير الديني العام والخاص.[71] نتيجة لذلك، كانت الثقافة الدينية الأصلية في مصر في انحدار مستمر. وبينما استمر السكان الأصليون في التحدثبلغتهم، اختفت القدرة على قراءة الكتابة الهيروغليفية ببطء مع تضاؤل دور كهنة المعابد المصرية. وفي بعض الأحيان تم تحويل المعابد نفسها إلى كنائس أو تُركت مهملة في الصحراء.[72]

في القرن الرابع، ومع انقسام [الإمبراطورية الرومانية، وجدت مصر نفسها ضمن الإمبراطورية الشرقية وعاصمتها القسطنطينية. وفي السنوات الأخيرة من الإمبراطورية، سقطت مصر في يد الجيش الساساني الفارسي أثناء الغزو الساساني لمصر (618-628). ثم استعادها الإمبراطور البيزنطي هرقليوس (629-639)، وفتحها في النهاية جيش الخلفاء الراشدين عام 639-641، مما يمثل نهاية الحكم البيزنطي والفترة التي تعتبر عادةً مصر القديمة.[citation needed]

الحكومة والاقتصاد

الإدارة والحكم

كان الفرعون هو الملك المطلق للبلاد، وكان يتمتع، نظرياً على الأقل، بالسيطرة الكاملة على الأرض ومواردها. وكان الملك هو القائد الأعلى للجيش ورئيس الحكومة، وكان يعتمد على بيروقراطية من المسؤولين لإدارة شؤونه. وكان المسؤول عن الإدارة هو نائبه في القيادة، الوزير، الذي كان يعمل ممثلاً للملك وينسق عمليات مسح الأراضي، والخزانة، ومشاريع البناء، والنظام القانوني، والأرشيف.[73] على المستوى الإقليمي، كانت البلاد مقصمة إلى ما يصل إلى 42 منطقة إدارية تسمى نوم (إقليم) كل منها تحت حكم النومارخ، وكان مسؤولاً أمام الوزير عن ولايته القضائية. شكلت المعابد العمود الفقري للاقتصاد. لم تكن دور عبادة فحسب، بل كانت مسؤولة أيضاً عن جمع وتخزين ثروة البلاد في نظام من المخازن والخزائن التي يديرها المشرفون، الذين يعيدو توزيع الحبوب والسلع.[74]

كان جزء كبير من الاقتصاد منظماً مركزياً وخاضعاً لسيطرة صارمة. وعلى الرغم من أن المصريين القدماء لم يستخدموا العملات حتى أواخر العصر المتأخر،[75] لكنهم استخدموا نوعاً من أنظمة المقايضة،[76] حيث أكياس الحبوب القياسية و"الديبن"، وهو وزن يبلغ حوالي 91 جراماً من النحاس أو الفضة، مما يشكل قاسماً مشتركاً للوزن.[77] كان العمال يتقاضون أجورهم على شكل حبوب؛ فقد يتقاضى العامل البسيط 51⁄2 كيس (200 كجم) من الحبوب شهرياً، بينما قد يتقاضى المشرف 71⁄2 كيس (250 كجم). كانت الأسعار ثابتة في جميع أنحاء البلاد ومسجلة في قوائم لتسهيل التجارة؛ على سبيل المثال، كان سعر القميص خمسة ديبن نحاسية، بينما كان سعر البقرة 140 ديبن.[77] يمكن مقايضة الحبوب بسلع أخرى، وفقاً لقائمة الأسعار الثابتة.[77] خلال القرن الخامس ق.م، طُرح استخدام النقود المسكوكة إلى مصر من الخارج. في البداية، كانت العملات المعدنية تُستخدم كقطع موحدة من الفلزات النفيسة بدلاً من كونها نقوداً حقيقية، لكن في القرون التالية، اعتمد التجار الدوليون على العملات المعدنية.[78]

الحالة الاجتماعية

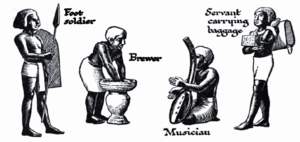

كان المجتمع المصري يتميز بتقسيم طبقي شديد التمايز، وكانت الحالة الاجتماعية واضحة للغاية. كان المزارعون يشكلون الجزء الأكبر من السكان، لكن المنتجات الزراعية كانت مملوكة بشكل مباشر للدولة أو المعبد أو النبلاء الذين يمتلكون الأرض.[79] كان المزارعون أيضاً خاضعين لضريبة العمل وكانوا مطالبين بالعمل في مشاريع الري أو البناء بنظام السخرة.[80] كان الفنانون والحرفيون يتمتعون بمكانة أعلى من المزارعين، لكنهم كانوا أيضاً تحت سيطرة الدولة، حيث كانوا يعملون في المتاجر الملحقة بالمعابد ويتقاضون أجورهم مباشرة من خزانة الدولة. كان الكتبة والمسؤولون يشكلون الطبقة العليا في مصر القديمة، والمعروفة باسم "طبقة التنورة البيضاء" في إشارة إلى الملابس الكتانية المبيضة التي كانت بمثابة علامة على رتبتهم.[81] أظهرت الطبقة العليا مكانتها الاجتماعية بشكل بارز في الفن والأدب. وتحت طبقة النبلاء كان الكهنة والأطباء والمهندسون الذين تلقوا تدريباً متخصصاً في مجالاتهم. ومن غير الواضح ما إذا كانت العبودية كما تُفهم اليوم موجودة في مصر القديمة؛ فهناك اختلاف في الآراء بين المؤلفين.[82]

كان المصريون القدماء ينظرون إلى الرجال والنساء، بما في ذلك الأشخاص من جميع الطبقات الاجتماعية، على أنهم متساوون بشكل أساسي بموجب القانون، وحتى أدنى فلاح كان يحق له تقديم التماس إلى الوزير وبلاطه للإنصاف.[83] على الرغم من أن العبيد كانوا يُستخدمون في الغالب كخدم متعاقدين، إلا أنهم كانوا قادرين على شراء وبيع عبوديتهم، وشق طريقهم إلى الحرية أو النبلاء، وكان يتم علاجهم عادةً من قبل الأطباء في مكان العمل.[84] كان للرجال والنساء الحق في امتلاك وبيع الممتلكات، وإبرام العقود، والزواج والطلاق، والحصول على الميراث، ومتابعة النزاعات القانونية في المحكمة. وكان بوسع الزوجين امتلاك الممتلكات بشكل مشترك وحماية أنفسهما من الطلاق من خلال الموافقة على عقود الزواج، التي تنص على الالتزامات المالية للزوج تجاه زوجته وأطفاله في حالة انتهاء الزواج. وبالمقارنة بنظيراتهن في اليونان القديمة وروما، وحتى الأماكن الأكثر حداثة في جميع أنحاء العالم، كان لدى النساء المصريات القديمات مجموعة أكبر من الخيارات الشخصية والحقوق القانونية وفرص الإنجاز. حتى أن نساء مثل حتشپسوت وكليوپاترا السابعة أصبحن فراعنة، بينما مارست أخريات السلطة كزوجات إلهيات لآمون. وعلى الرغم من هذه الحريات، لم تشارك النساء المصريات القديمات في كثير من الأحيان في الأدوار الرسمية في الإدارة، باستثناء رئيسات الكهنة الملكيات، ويبدو أنهن كن يؤدين أدواراً ثانوية فقط في المعابد (لا توجد بيانات كثيرة عن العديد من الأسرات)، ومن المحتمل أنهن لم يكن متعلمات مثل الرجال.[83]

النظام القانوني

كان رأس النظام القانوني رسمياً هو الفرعون، الذي كان مسؤولاً عن سن القوانين، وتحقيق العدالة، والحفاظ على القانون والنظام، وهو المفهوم الذي أشار إليه المصريون القدماء باسم ماعت.[73] على الرغم من عدم وجود أي مدونات قانونية من مصر القديمة، إلا أن وثائق البلاط تظهر أن القانون المصري كان يعتمد على وجهة نظر سليمة حول الصواب والخطأ والتي أكدت على التوصل إلى اتفاقيات وحل النزاعات بدلاً من الالتزام الصارم بمجموعة معقدة من القوانين.[83] كانت مجالس الشيوخ المحلية، المعروفة باسم كنبت في الدولة الحديثة، مسؤولة عن الفصل في قضايا المحكمة التي تنطوي على مطالبات صغيرة ونزاعات بسيطة.[73] كانت القضايا الأكثر خطورة التي تنطوي على القتل، والمعاملات العقارية الكبرى، وسرقة المقابر تُحال إلى الكنبت الأعظم، الذي كان يرأسه الوزير أو الفرعون. وكان من المتوقع أن يمثل المدعون والمدعى عليهم أنفسهم وكانوا مطالبين بأداء يمين بأنهم قالوا الحقيقة. وفي بعض الحالات، تولت الدولة دور المدعي العام والقاضي، وكان بإمكانها تعذيب المتهم بالضرب للحصول على اعتراف وأسماء أي متآمرين. وسواء كانت التهم تافهة أو خطيرة، كان كاتبو المحكمة يوثقون الشكوى والشهادة والحكم في القضية للرجوع إليها في المستقبل.[85]

كانت العقوبة على الجرائم البسيطة تشمل إما فرض غرامات أو الضرب أو تشويه الوجه أو النفي، وذلك حسب خطورة الجريمة. أما الجرائم الخطيرة مثل القتل وسرقة المقابر فكانت تُعاقَب بالإعدام، أو بقطع الرأس أو الغرق أو الخزوقة، كما كان من الممكن أن تمتد العقوبة إلى أسرة المجرم.[73] بدءاً من الدولة الحديثة، لعبت هياكل الوحي دوراً رئيسياً في النظام القانوني، حيث كانت توزع العدالة في القضايا المدنية والجنائية. وكان الإجراء يتلخص في طرح سؤال "نعم" أو "لا" على الإله فيما يتعلق بصحة أو خطأ قضية ما. وكان الإله، الذي يحمله عدد من الكهنة، يصدر الحكم باختيار أحد الخيارين، أو التحرك إلى الأمام أو الخلف، أو الإشارة إلى إحدى الإجابات المكتوبة على قطعة من ورق البردي أو شقفة مرسومة.[86]

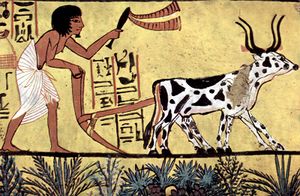

الزراعة

ساهمت مجموعة من السمات الجغرافية المواتية في نجاح الثقافة المصرية القديمة، وكان أهمها التربة الخصبة الغنية الناتجة عن الفيضانات السنوية لنهر النيل. وبالتالي تمكن المصريون القدماء من إنتاج وفرة من الغذاء، مما سمح للسكان بتخصيص المزيد من الوقت والموارد للمساعي الثقافية والتكنولوجية والفنية. كانت ادارة الأراضي أمراً بالغ الأهمية في مصر القديمة لأن الضرائب كانت تُفرض على أساس كمية الأراضي التي يمتلكها الشخص.[87]

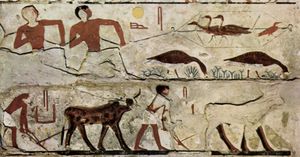

كانت الزراعة في مصر تعتمد على دورة نهر النيل. وكان المصريون يعرفون ثلاثة فصول: آخت (الفيضان)، پرت (الزراعة)، وشمو (الحصاد). كان موسم الفيضان يستمر من يونيو إلى سبتمبر، حيث تترسب على ضفاف النهر طبقة من الطمي الغني بالمعادن المثالية لزراعة المحاصيل. وبعد انحسار مياه الفيضان، استمر يموسم الزراعة من أكتوبر إلى فبراير. كان المزارعون يحرثون الحقول ويزرعون البذور فيها، التي كانت تُروى عن طريق الخنادق والقنوات. كانت مصر تتلقى القليل من الأمطار، لذا اعتمد المزارعون على نهر النيل لري محاصيلهم.[88] من مارس إلى مايو، كان المزارعون يستخدمون المنجال لحصاد محاصيلهم، والتي كانت تُدرس بعد ذلك باستخدام المخباط لفصل القش عن الحبوب. كانت الغربلة تزيل الحثالة من الحبوب، ثم تُطحن الحبوب إلى دقيق، وتُخمر لصنع البيرة، أو تُخزن للاستخدام لاحقاً.[89]

كان المصريون القدماء يزرعون القمح النشوي والشعير، والعديد من الحبوب الأخرى، والتي كانت تستخدم جميعها لصنع الغذاء الرئيسيين الخبز والبيرة.[90] كانت نباتات الكتان، التي تُقتلع قبل أن تبدأ في الإزهار، تُزرع من أجل ألياف سيقانها. كانت هذه الألياف تُشق على طولها وتُغزل في خيوط، كانت تستخدم لنسج صفائح أقمشة الكتان وصناعة الملابس. كان ورق البردي الذي ينمو على ضفاف نهر النيل يستخدم لصنع الورق. كانت الخضروات والفواكه تُزرع في الحدائق، بالقرب من المساكن وعلى أرض مرتفعة، وكان لابد من سقيها يدوياً. كانت الخضروات تشمل الكراث والثوم والبطيخ والقرع والبقول والخس ومحاصيل أخرى، بالإضافة إلى العنب الذي كان يُصنع منه النبيذ.[91]

الحيوانات

كان المصريون يعتقدون أن العلاقة المتوازنة بين البشر والحيوانات هي عنصر أساسي في النظام الكوني؛ وبالتالي كان يُعتقد أن البشر والحيوانات والنباتات أعضاء في كيان واحد.[92] كانت الحيوانات، سواء المستأنسة أو البرية، مصدراً هاماً للروحانية والرفقة والغذاء بالنسبة للمصريين القدماء. كانت الأبقار هي أهم أنواع الماشية في مصر القديمة؛ حيث كانت الإدارة الضرائب تجمع على الماشية في تعدادات منتظمة، وكان حجم القطيع يعكس هيبة وأهمية العزبة أو المعبد الذي يمتلكها. بالإضافة إلى الماشية، كان المصريون القدماء يربون الأغنام والماعز والخنازير. كان يتم اصطياد الدواجن، مثل البط والأوز والحمام، في الشباك وتربيتها في المزارع، حيث تُطعم قسراً بالعجين لتسمينها.[93] كان نهر النيل مصدراً وفيراً للأسماك. كما تم تدجين النحل منذ عصر الدولة القديمة على الأقل، وكان يوفر العسل والشمع.[94]

استخدم المصريون القدماء الحمير والثيران كحيوانات عاملة، وكانوا مسؤولين عن حرث الحقول ودوس البذور في التربة. وكان ذبح الثور المسمن أيضاً جزءاً أساسياً من طقوس تقديم القرابين. أدخل الهكسوس الخيول في الفترة الانتقالية الثانية. لم تُستخدم الجمال، على الرغم من أنها معروفة منذ عصر الدولة الحديثة، كحيوانات حمل حتى الفترة المتأخرة. هناك أيضاً أدلة تشير إلى أن الفيلة كانت تُستخدم لفترة وجيزة في الفترة المتأخرة ولكنها هُجرت إلى حد كبير بسبب نقص أراضي الرعي. [93] كانت القطط والكلاب والقرود حيوانات أليفة شائعة، بينما كانت تُستورد الحيوانات الأليفة الأكثر غرابة من أفريقيا جنوب الصحراء، مثل الأسود،[95] كانت الحيوانات الأليفة مخصصة للعائلة المالكة. لاحظ هيرودوت أن المصريين كانوا الشعب الوحيد الذي يحتفظ بحيواناته معه في المنزل.[92] خلال الفترة المتأخرة، كانت عبادة الآلهة في شكلها الحيواني شائعة للغاية، مثل الإلهة القطة باستت والإله أبو منجل تحوت، وكان يُحتفظ بهذه الحيوانات بأعداد كبيرة لغرض التضحية الطقسية.[96]

الموارد الطبيعية

Egypt is rich in building and decorative stone, copper and lead ores, gold, and semiprecious stones. These natural resources allowed the ancient Egyptians to build monuments, sculpt statues, make tools, and fashion jewelry.[97] Embalmers used salts from the Wadi Natrun for mummification, which also provided the gypsum needed to make plaster.[98] Ore-bearing rock formations were found in distant, inhospitable wadis in the Eastern Desert and the Sinai, requiring large, state-controlled expeditions to obtain natural resources found there. There were extensive gold mines in Nubia, and one of the first maps known is of a gold mine in this region. The Wadi Hammamat was a notable source of granite, greywacke, and gold. Flint was the first mineral collected and used to make tools, and flint handaxes are the earliest pieces of evidence of habitation in the Nile valley. Nodules of the mineral were carefully flaked to make blades and arrowheads of moderate hardness and durability even after copper was adopted for this purpose.[99] Ancient Egyptians were among the first to use minerals such as sulfur as cosmetic substances.[100]

The Egyptians worked deposits of the lead ore galena at Gebel Rosas to make net sinkers, plumb bobs, and small figurines. Copper was the most important metal for toolmaking in ancient Egypt and was smelted in furnaces from malachite ore mined in the Sinai.[101] Workers collected gold by washing the nuggets out of sediment in alluvial deposits, or by the more labor-intensive process of grinding and washing gold-bearing quartzite. Iron deposits found in upper Egypt were used in the Late Period.[102] High-quality building stones were abundant in Egypt; the ancient Egyptians quarried limestone all along the Nile valley, granite from Aswan, and basalt and sandstone from the wadis of the Eastern Desert. Deposits of decorative stones such as porphyry, greywacke, alabaster, and carnelian dotted the Eastern Desert and were collected even before the First Dynasty. In the Ptolemaic and Roman Periods, miners worked deposits of emeralds in Wadi Sikait and amethyst in Wadi el-Hudi.[103]

التجارة

The ancient Egyptians engaged in trade with their foreign neighbors to obtain rare, exotic goods not found in Egypt. In the Predynastic Period, they established trade with Nubia to obtain gold and incense. They also established trade with Palestine, as evidenced by Palestinian-style oil jugs found in the burials of the First Dynasty pharaohs.[104] An Egyptian colony stationed in southern Canaan dates to slightly before the First Dynasty.[105] Tell es-Sakan in present-day Gaza was established as an Egyptian settlement in the late 4th millennium BC, and is theorised to have been the main Egyptian colonial site in the region.[106] Narmer had Egyptian pottery produced in Canaan and exported back to Egypt.[107][108]

By the Second Dynasty at latest, ancient Egyptian trade with Byblos yielded a critical source of quality timber not found in Egypt. By the Fifth Dynasty, trade with Punt provided gold, aromatic resins, ebony, ivory, and wild animals such as monkeys and baboons.[109] Egypt relied on trade with Anatolia for essential quantities of tin as well as supplementary supplies of copper, both metals being necessary for the manufacture of bronze. The ancient Egyptians prized the blue stone lapis lazuli, which had to be imported from far-away Afghanistan. Egypt's Mediterranean trade partners also included Greece and Crete, which provided, among other goods, supplies of olive oil.[110]

اللغة

التطور التاريخي

| ||||||

| r n kmt 'Egyptian language' بالهيروغليفية |

|---|

The Egyptian language is a northern Afro-Asiatic language closely related to the Berber and Semitic languages.[111] It has the longest known history of any language having been written from ح. 3200 BC to the Middle Ages and remaining as a spoken language for longer. The phases of ancient Egyptian are Old Egyptian, Middle Egyptian (Classical Egyptian), Late Egyptian, Demotic and Coptic.[112] Egyptian writings do not show dialect differences before Coptic, but it was probably spoken in regional dialects around Memphis and later Thebes.[113]

Ancient Egyptian was a synthetic language, but it became more analytic later on. Late Egyptian developed prefixal definite and indefinite articles, which replaced the older inflectional suffixes. There was a change from the older verb–subject–object word order to subject–verb–object.[114] The Egyptian hieroglyphic, hieratic, and demotic scripts were eventually replaced by the more phonetic Coptic alphabet. Coptic is still used in the liturgy of the Egyptian Orthodox Church, and traces of it are found in modern Egyptian Arabic.[115]

النُطق والقواعد

Ancient Egyptian has 25 consonants similar to those of other Afro-Asiatic languages. These include pharyngeal and emphatic consonants, voiced and voiceless stops, voiceless fricatives and voiced and voiceless affricates. It has three long and three short vowels, which expanded in Late Egyptian to about nine.[116] The basic word in Egyptian, similar to Semitic and Berber, is a triliteral or biliteral root of consonants and semiconsonants. Suffixes are added to form words. The verb conjugation corresponds to the person. For example, the triconsonantal skeleton S-Ḏ-M is the semantic core of the word 'hear'; its basic conjugation is sḏm, 'he hears'. If the subject is a noun, suffixes are not added to the verb:[117] sḏm ḥmt, 'the woman hears'.

Adjectives are derived from nouns through a process that Egyptologists call nisbation because of its similarity with Arabic.[118] The word order is predicate–subject in verbal and adjectival sentences, and subject–predicate in nominal and adverbial sentences.[119] The subject can be moved to the beginning of sentences if it is long and is followed by a resumptive pronoun.[120] Verbs and nouns are negated by the particle n, but nn is used for adverbial and adjectival sentences. Stress falls on the ultimate or penultimate syllable, which can be open (CV) or closed (CVC).[121]

الكتابة

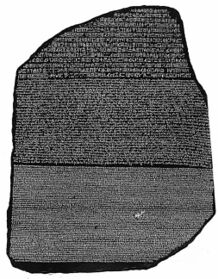

Hieroglyphic writing dates from ح. 3000 BC, and is composed of hundreds of symbols. A hieroglyph can represent a word, a sound, or a silent determinative; and the same symbol can serve different purposes in different contexts. Hieroglyphs were a formal script, used on stone monuments and in tombs, that could be as detailed as individual works of art. In day-to-day writing, scribes used a cursive form of writing, called hieratic, which was quicker and easier. While formal hieroglyphs may be read in rows or columns in either direction (though typically written from right to left), hieratic was always written from right to left, usually in horizontal rows. A new form of writing, Demotic, became the prevalent writing style, and it is this form of writing—along with formal hieroglyphs—that accompany the Greek text on the Rosetta Stone.[123]

Around the first century AD, the Coptic alphabet started to be used alongside the Demotic script. Coptic is a modified Greek alphabet with the addition of some Demotic signs.[124] Although formal hieroglyphs were used in a ceremonial role until the fourth century, towards the end only a small handful of priests could still read them. As the traditional religious establishments were disbanded, knowledge of hieroglyphic writing was mostly lost. Attempts to decipher them date to the Byzantine[125] and Islamic periods in Egypt,[126] but only in the 1820s, after the discovery of the Rosetta Stone and years of research by Thomas Young and Jean-François Champollion, were hieroglyphs substantially deciphered.[127]

الأدب

Writing first appeared in association with kingship on labels and tags for items found in royal tombs. It was primarily an occupation of the scribes, who worked out of the Per Ankh institution or the House of Life. The latter comprised offices, libraries (called House of Books), laboratories and observatories.[128] Some of the best-known pieces of ancient Egyptian literature, such as the Pyramid and Coffin Texts, were written in Classical Egyptian, which continued to be the language of writing until about 1300 BC. Late Egyptian was spoken from the New Kingdom onward and is represented in Ramesside administrative documents, love poetry and tales, as well as in Demotic and Coptic texts. During this period, the tradition of writing had evolved into the tomb autobiography, such as those of Harkhuf and Weni. The genre known as Sebayt ('instructions') was developed to communicate teachings and guidance from famous nobles; the Ipuwer papyrus, a poem of lamentations describing natural disasters and social upheaval, is a famous example.

The Story of Sinuhe, written in Middle Egyptian, might be the classic of Egyptian literature.[129] Also written at this time was the Westcar Papyrus, a set of stories told to Khufu by his sons relating the marvels performed by priests.[130] The Instruction of Amenemope is considered a masterpiece of Near Eastern literature.[131] Towards the end of the New Kingdom, the vernacular language was more often employed to write popular pieces such as the Story of Wenamun and the Instruction of Any. The former tells the story of a noble who is robbed on his way to buy cedar from Lebanon and of his struggle to return to Egypt. From about 700 BC, narrative stories and instructions, such as the popular Instructions of Onchsheshonqy, as well as personal and business documents were written in the demotic script and phase of Egyptian. Many stories written in demotic during the Greco-Roman period were set in previous historical eras, when Egypt was an independent nation ruled by great pharaohs such as Ramesses II.[132]

الثقافة

الحياة اليومية

Most ancient Egyptians were farmers tied to the land. Their dwellings were restricted to immediate family members, and were constructed of mudbrick designed to remain cool in the heat of the day. Each home had a kitchen with an open roof, which contained a grindstone for milling grain and a small oven for baking the bread.[133] Ceramics served as household wares for the storage, preparation, transport, and consumption of food, drink, and raw materials. Walls were painted white and could be covered with dyed linen wall hangings. Floors were covered with reed mats, while wooden stools, beds raised from the floor and individual tables comprised the furniture.[134]

The ancient Egyptians placed a great value on hygiene and appearance. Most bathed in the Nile and used a pasty soap made from animal fat and chalk. Men shaved their entire bodies for cleanliness; perfumes and aromatic ointments covered bad odors and soothed skin.[135] Clothing was made from simple linen sheets that were bleached white, and both men and women of the upper classes wore wigs, jewelry, and cosmetics. Children went without clothing until maturity, at about age 12, and at this age males were circumcised and had their heads shaved. Mothers were responsible for taking care of the children, while the father provided the family's income.[136]

Music and dance were popular entertainments for those who could afford them. Early instruments included flutes and harps, while instruments similar to trumpets, oboes, and pipes developed later and became popular. In the New Kingdom, the Egyptians played on bells, cymbals, tambourines, drums, and imported lutes and lyres from Asia.[137] The sistrum was a rattle-like musical instrument that was especially important in religious ceremonies.

The ancient Egyptians enjoyed a variety of leisure activities, including games and music. Senet, a board game where pieces moved according to random chance, was particularly popular from the earliest times; another similar game was mehen, which had a circular gaming board. "Hounds and Jackals" also known as 58 holes is another example of board games played in ancient Egypt. The first complete set of this game was discovered from a Theban tomb of the Egyptian pharaoh Amenemhat IV that dates to the 13th Dynasty.[138] Juggling and ball games were popular with children, and wrestling is also documented in a tomb at Beni Hasan.[139] The wealthy members of ancient Egyptian society enjoyed hunting, fishing, and boating as well.

The excavation of the workers' village of Deir el-Medina has resulted in one of the most thoroughly documented accounts of community life in the ancient world, which spans almost four hundred years. There is no comparable site in which the organization, social interactions, and working and living conditions of a community have been studied in such detail.[140]

المطبخ

Egyptian cuisine remained remarkably stable over time; indeed, the cuisine of modern Egypt retains some striking similarities to the cuisine of the ancients. The staple diet consisted of bread and beer, supplemented with vegetables such as onions and garlic, and fruit such as dates and figs. Wine and meat were enjoyed by all on feast days while the upper classes indulged on a more regular basis. Fish, meat, and fowl could be salted or dried, and could be cooked in stews or roasted on a grill.[141]

العمارة

The architecture of ancient Egypt includes some of the most famous structures in the world: the Great Pyramids of Giza and the temples at Thebes. Building projects were organized and funded by the state for religious and commemorative purposes, but also to reinforce the wide-ranging power of the pharaoh. The ancient Egyptians were skilled builders; using only simple but effective tools and sighting instruments, architects could build large stone structures with great accuracy and precision that is still envied today.[142]

The domestic dwellings of elite and ordinary Egyptians alike were constructed from perishable materials such as mudbricks and wood, and have not survived. Peasants lived in simple homes, while the palaces of the elite and the pharaoh were more elaborate structures. A few surviving New Kingdom palaces, such as those in Malkata and Amarna, show richly decorated walls and floors with scenes of people, birds, water pools, deities and geometric designs.[143] Important structures such as temples and tombs that were intended to last forever were constructed of stone instead of mudbricks. The architectural elements used in the world's first large-scale stone building, Djoser's mortuary complex, include post and lintel supports in the papyrus and lotus motif.[citation needed]

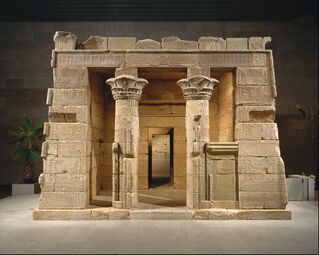

The earliest preserved ancient Egyptian temples, such as those at Giza, consist of single, enclosed halls with roof slabs supported by columns. In the New Kingdom, architects added the pylon, the open courtyard, and the enclosed hypostyle hall to the front of the temple's sanctuary, a style that was standard until the Greco-Roman period.[144] The earliest and most popular tomb architecture in the Old Kingdom was the mastaba, a flat-roofed rectangular structure of mudbrick or stone built over an underground burial chamber. The step pyramid of Djoser is a series of stone mastabas stacked on top of each other. Pyramids were built during the Old and Middle Kingdoms, but most later rulers abandoned them in favor of less conspicuous rock-cut tombs.[145] The use of the pyramid form continued in private tomb chapels of the New Kingdom and in the royal pyramids of Nubia.[146]

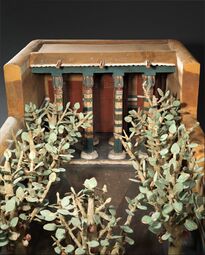

Model of a household porch and garden, ح. 1981–1975 BC

The Temple of Dendur, completed by 10 BC, Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

The well preserved Temple of Isis from Philae is an example of Egyptian architecture and architectural sculpture.

Illustration of various types of capitals, by Karl Richard Lepsius

الفنون

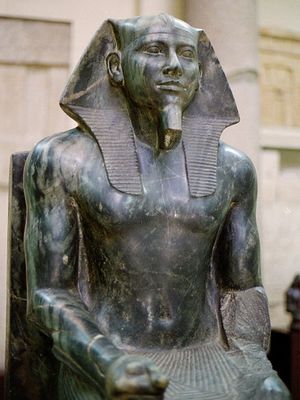

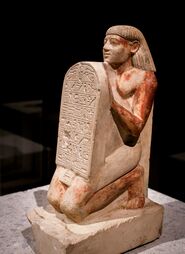

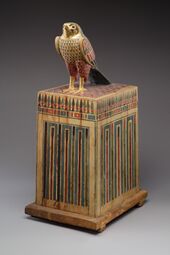

The ancient Egyptians produced art to serve functional purposes. For over 3500 years, artists adhered to artistic forms and iconography that were developed during the Old Kingdom, following a strict set of principles that resisted foreign influence and internal change.[147] These artistic standards—simple lines, shapes, and flat areas of color combined with the characteristic flat projection of figures with no indication of spatial depth—created a sense of order and balance within a composition. Images and text were intimately interwoven on tomb and temple walls, coffins, stelae, and even statues. The Narmer Palette, for example, displays figures that can also be read as hieroglyphs.[148] Because of the rigid rules that governed its highly stylized and symbolic appearance, ancient Egyptian art served its political and religious purposes with precision and clarity.[149]

Ancient Egyptian artisans used stone as a medium for carving statues and fine reliefs, but used wood as a cheap and easily carved substitute. Paints were obtained from minerals such as iron ores (red and yellow ochres), copper ores (blue and green), soot or charcoal (black), and limestone (white). Paints could be mixed with gum arabic as a binder and pressed into cakes, which could be moistened with water when needed.[150]

Pharaohs used reliefs to record victories in battle, royal decrees, and religious scenes. Common citizens had access to pieces of funerary art, such as shabti statues and books of the dead, which they believed would protect them in the afterlife.[151] During the Middle Kingdom, wooden or clay models depicting scenes from everyday life became popular additions to the tomb. In an attempt to duplicate the activities of the living in the afterlife, these models show laborers, houses, boats, and even military formations that are scale representations of the ideal ancient Egyptian afterlife.[152]

Despite the homogeneity of ancient Egyptian art, the styles of particular times and places sometimes reflected changing cultural or political attitudes. After the invasion of the Hyksos in the Second Intermediate Period, Minoan-style frescoes were found in Avaris.[153] The most striking example of a politically driven change in artistic forms comes from the Amarna Period, where figures were radically altered to conform to Akhenaten's revolutionary religious ideas.[154] This style, known as Amarna art, was quickly abandoned after Akhenaten's death and replaced by the traditional forms.[155]

Stelophorous statue of Amenemhat; ح. 1500 BC

Portrait head of pharaoh Hatshepsut or Thutmose III; 1480–1425 BC

الاعتقادات الدينية

Beliefs in the divine and in the afterlife were ingrained in ancient Egyptian civilization from its inception; pharaonic rule was based on the divine right of kings. The Egyptian pantheon was populated by gods who had supernatural powers and were called on for help or protection. However, the gods were not always viewed as benevolent, and Egyptians believed they had to be appeased with offerings and prayers. The structure of this pantheon changed continually as new deities were promoted in the hierarchy, but priests made no effort to organize the diverse and sometimes conflicting myths and stories into a coherent system.[156] These various conceptions of divinity were not considered contradictory but rather layers in the multiple facets of reality.[157]

Gods were worshiped in cult temples administered by priests acting on the king's behalf. At the center of the temple was the cult statue in a shrine. Temples were not places of public worship or congregation, and only on select feast days and celebrations was a shrine carrying the statue of the god brought out for public worship. Normally, the god's domain was sealed off from the outside world and was only accessible to temple officials. Common citizens could worship private statues in their homes, and amulets offered protection against the forces of chaos.[158] After the New Kingdom, the pharaoh's role as a spiritual intermediary was de-emphasized as religious customs shifted to direct worship of the gods. As a result, priests developed a system of oracles to communicate the will of the gods directly to the people.[159]

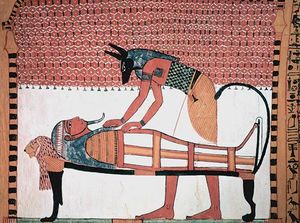

The Egyptians believed that every human being was composed of physical and spiritual parts or aspects. In addition to the body, each person had a šwt (shadow), a ba (personality or soul), a ka (life-force), and a name.[160] The heart, rather than the brain, was considered the seat of thoughts and emotions. After death, the spiritual aspects were released from the body and could move at will, but they required the physical remains (or a substitute, such as a statue) as a permanent home. The ultimate goal of the deceased was to rejoin his ka and ba and become one of the "blessed dead", living on as an akh, or "effective one". For this to happen, the deceased had to be judged worthy in a trial, in which the heart was weighed against a "feather of truth". If deemed worthy, the deceased could continue their existence on earth in spiritual form.[161] If they were not deemed worthy, their heart was eaten by Ammit the Devourer and they were erased from the Universe.[citation needed]

عادات الدفن

The ancient Egyptians maintained an elaborate set of burial customs that they believed were necessary to ensure immortality after death. These customs involved preserving the body by mummification, performing burial ceremonies, and interring with the body goods the deceased would use in the afterlife.[151] Before the Old Kingdom, bodies buried in desert pits were naturally preserved by desiccation. The arid, desert conditions were a boon throughout the history of ancient Egypt for burials of the poor, who could not afford the elaborate burial preparations available to the elite. Wealthier Egyptians began to bury their dead in stone tombs and use artificial mummification, which involved removing the internal organs, wrapping the body in linen, and burying it in a rectangular stone sarcophagus or wooden coffin. Beginning in the Fourth Dynasty, some parts were preserved separately in canopic jars.[162]

By the New Kingdom, the ancient Egyptians had perfected the art of mummification; the best technique took 70 days and involved removing the internal organs, removing the brain through the nose, and desiccating the body in a mixture of salts called natron. The body was then wrapped in linen with protective amulets inserted between layers and placed in a decorated anthropoid coffin. Mummies of the Late Period were also placed in painted cartonnage mummy cases. Actual preservation practices declined during the Ptolemaic and Roman eras, while greater emphasis was placed on the outer appearance of the mummy, which was decorated.[163]

Wealthy Egyptians were buried with larger quantities of luxury items, but all burials, regardless of social status, included goods for the deceased. Funerary texts were often included in the grave, and, beginning in the New Kingdom, so were shabti statues that were believed to perform manual labor for them in the afterlife.[164] Rituals in which the deceased was magically re-animated accompanied burials. After burial, living relatives were expected to occasionally bring food to the tomb and recite prayers on behalf of the deceased.[165]

العسكرية

The ancient Egyptian military was responsible for defending Egypt against foreign invasion, and for maintaining Egypt's domination in the ancient Near East. The military protected mining expeditions to the Sinai during the Old Kingdom and fought civil wars during the First and Second Intermediate Periods. The military was responsible for maintaining fortifications along important trade routes, such as those found at the city of Buhen on the way to Nubia. Forts also were constructed to serve as military bases, such as the fortress at Sile, which was a base of operations for expeditions to the Levant. In the New Kingdom, a series of pharaohs used the standing Egyptian army to attack and conquer Kush and parts of the Levant.[166]

Typical military equipment included bows and arrows, spears, and round-topped shields made by stretching animal skin over a wooden frame. In the New Kingdom, the military began using chariots that had earlier been introduced by the Hyksos invaders. Weapons and armor continued to improve after the adoption of bronze: shields were now made from solid wood with a bronze buckle, spears were tipped with a bronze point, and the khopesh was adopted from Asiatic soldiers.[167] The pharaoh was usually depicted in art and literature riding at the head of the army; it has been suggested that at least a few pharaohs, such as Seqenenre Tao II and his sons, did do so.[168] However, it has also been argued that "kings of this period did not personally act as frontline war leaders, fighting alongside their troops".[169] Soldiers were recruited from the general population, but during, and especially after, the New Kingdom, mercenaries from Nubia, Kush, and Libya were hired to fight for Egypt.[170]

التكنولوجيا والطب والرياضيات

التكنولوجيا

In technology, medicine, and mathematics, ancient Egypt achieved a relatively high standard of productivity and sophistication. Traditional empiricism, as evidenced by the Edwin Smith and Ebers papyri (ح. 1600 BC), is first credited to Egypt. The Egyptians created their own alphabet and decimal system.

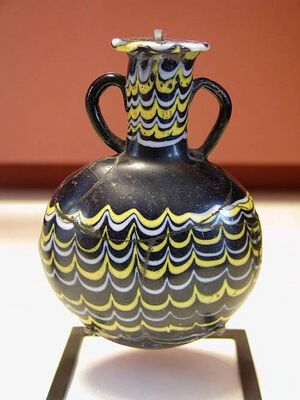

الفايانس والزجاج

Even before the Old Kingdom, the ancient Egyptians had developed a glassy material known as faience, which they treated as a type of artificial semi-precious stone. Faience is a non-clay ceramic made of silica, small amounts of lime and soda, and a colorant, typically copper.[171] The material was used to make beads, tiles, figurines, and small wares. Several methods can be used to create faience, but typically production involved application of the powdered materials in the form of a paste over a clay core, which was then fired. By a related technique, the ancient Egyptians produced a pigment known as Egyptian blue, also called blue frit, which is produced by fusing (or sintering) silica, copper, lime, and an alkali such as natron. The product can be ground up and used as a pigment.[172]

The ancient Egyptians could fabricate a wide variety of objects from glass with great skill, but it is not clear whether they developed the process independently.[173] It is also unclear whether they made their own raw glass or merely imported pre-made ingots, which they melted and finished. However, they did have technical expertise in making objects, as well as adding trace elements to control the color of the finished glass. A range of colors could be produced, including yellow, red, green, blue, purple, and white, and the glass could be made either transparent or opaque.[174]

الطب

The medical problems of the ancient Egyptians stemmed directly from their environment. Living and working close to the Nile brought hazards from malaria and debilitating schistosomiasis parasites, which caused liver and intestinal damage. Dangerous wildlife such as crocodiles and hippos were also a common threat. The lifelong labors of farming and building put stress on the spine and joints, and traumatic injuries from construction and warfare all took a significant toll on the body. The grit and sand from stone-ground flour abraded teeth, leaving them susceptible to abscesses (though caries were rare).[175]

The diets of the wealthy were rich in sugars, which promoted periodontal disease.[176] Despite the flattering physiques portrayed on tomb walls, the overweight mummies of many of the upper class show the effects of a life of overindulgence.[177] Adult life expectancy was about 35 for men and 30 for women, but reaching adulthood was difficult as about one-third of the population died in infancy.[ج]

Ancient Egyptian physicians were renowned in the ancient Near East for their healing skills, and some, such as Imhotep, remained famous long after their deaths.[178] Herodotus remarked that there was a high degree of specialization among Egyptian physicians, with some treating only the head or the stomach, while others were eye-doctors and dentists.[179] Training of physicians took place at the Per Ankh or "House of Life" institution, most notably those headquartered in Per-Bastet during the New Kingdom and at Abydos and Saïs in the Late period. Medical papyri show empirical knowledge of anatomy, injuries, and practical treatments.[180]

Wounds were treated by bandaging with raw meat, white linen, sutures, nets, pads, and swabs soaked with honey to prevent infection,[181] while opium, thyme, and belladona were used to relieve pain. The earliest records of burn treatment describe burn dressings that use the milk from mothers of male babies. Prayers were made to the goddess Isis. Moldy bread, honey, and copper salts were also used to prevent infection from dirt in burns.[182] Garlic and onions were used regularly to promote good health and were thought to relieve asthma symptoms. Ancient Egyptian surgeons stitched wounds, set broken bones, and amputated diseased limbs, but they recognized that some injuries were so serious that they could only make the patient comfortable until death occurred.[183]

التكنولوجيا البحرية

Early Egyptians knew how to assemble planks of wood into a ship hull and had mastered advanced forms of shipbuilding as early as 3000 BC. The Archaeological Institute of America reports that the oldest planked ships known are the Abydos boats.[4] A group of 14 discovered ships in Abydos were constructed of wooden planks "sewn" together. Discovered by Egyptologist David O'Connor of New York University,[184] woven straps were found to have been used to lash the planks together,[4] and reeds or grass stuffed between the planks helped to seal the seams.[4] Because the ships are all buried together and near a mortuary belonging to Pharaoh Khasekhemwy, originally they were all thought to have belonged to him, but one of the 14 ships dates to 3000 BC, and the associated pottery jars buried with the vessels also suggest earlier dating. The ship dating to 3000 BC was 75 أقدام (23 m) long and is now thought to perhaps have belonged to an earlier pharaoh, perhaps one as early as Hor-Aha.[184]

Early Egyptians also knew how to assemble planks of wood with treenails to fasten them together, using pitch for caulking the seams. The "Khufu ship", a 43.6-متر (143 ft) vessel sealed into a pit in the Giza pyramid complex at the foot of the Great Pyramid of Giza in the Fourth Dynasty around 2500 BC, is a full-size surviving example that may have filled the symbolic function of a solar barque. Early Egyptians also knew how to fasten the planks of this ship together with mortise and tenon joints.[4]

Large seagoing ships are known to have been heavily used by the Egyptians in their trade with the city states of the eastern Mediterranean, especially Byblos (on the coast of modern-day Lebanon), and in several expeditions down the Red Sea to the Land of Punt. In fact one of the earliest Egyptian words for a seagoing ship is a "Byblos Ship", which originally defined a class of Egyptian seagoing ships used on the Byblos run; however, by the end of the Old Kingdom, the term had come to include large seagoing ships, whatever their destination.[185]

In 1977, an ancient north–south canal was discovered extending from Lake Timsah to the Ballah Lakes.[186] It was dated to the Middle Kingdom of Egypt by extrapolating dates of ancient sites constructed along its course.[186][ح]

In 2011, archaeologists from Italy, the United States, and Egypt, excavating a dried-up lagoon known as Mersa Gawasis, unearthed traces of an ancient harbor that once launched early voyages, such as Hatshepsut's Punt, expedition onto the open ocean. Some of the site's most evocative evidence for the ancient Egyptians' seafaring prowess include large ship timbers and hundreds of feet of ropes, made from papyrus, coiled in huge bundles.[187] In 2013, a team of Franco-Egyptian archaeologists discovered what is believed to be the world's oldest port, dating back about 4500 years, from the time of King Khufu, on the Red Sea coast, near Wadi el-Jarf (about 110 miles south of Suez).[188]

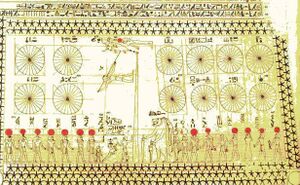

الرياضيات

The earliest attested examples of mathematical calculations date to the predynastic Naqada period, and show a fully developed numeral system.[خ] The importance of mathematics to an educated Egyptian is suggested by a New Kingdom fictional letter in which the writer proposes a scholarly competition between himself and another scribe regarding everyday calculation tasks such as accounting of land, labor, and grain.[190] Texts such as the Rhind Mathematical Papyrus and the Moscow Mathematical Papyrus show that the ancient Egyptians could perform the four basic mathematical operations—addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division—use fractions, calculate the areas of rectangles, triangles, and circles and compute the volumes of boxes, columns and pyramids. They understood basic concepts of algebra and geometry, and could solve systems of equations.[191]

| ||

| 2⁄3 بالهيروغليفية |

|---|

Mathematical notation was decimal, and based on hieroglyphic signs for each power of ten up to one million. Each of these could be written as many times as necessary to add up to the desired number; so to write the number eighty or eight hundred, the symbol for ten or one hundred was written eight times respectively.[192] Because their methods of calculation could not handle most fractions with a numerator greater than one, they had to write fractions as the sum of several fractions. For example, they resolved the fraction two-fifths into the sum of one-third + one-fifteenth. Standard tables of values facilitated this.[193] Some common fractions, however, were written with a special glyph—the equivalent of the modern two-thirds is shown on the right.[194]

Ancient Egyptian mathematicians knew the Pythagorean theorem as an empirical formula. They were aware, for example, that a triangle had a right angle opposite the hypotenuse when its sides were in a 3–4–5 ratio.[195] They were able to estimate the area of a circle by subtracting one-ninth from its diameter and squaring the result:

- Area ≈ [(8⁄9)D]2 = (256⁄81)r2 ≈ 3.16r2,

a reasonable approximation of the formula πr2.[196]

السكان

Estimates of the size of the population range from 1–1.5 million in the 3rd millennium BC to possibly 2–3 million by the 1st millennium BC, before growing significantly towards the end of that millennium.[197]

علم الوراثة الأثري

According to historian William Stiebling and archaeologist Susan N. Helft, conflicting DNA analysis on recent genetic samples such as the Amarna royal mummies has led to a lack of consensus on the genetic makeup of the ancient Egyptians and their geographic origins.[198]

The genetic history of Ancient Egypt remains a developing field, and is relevant for the understanding of population demographic events connecting Africa and Eurasia. To date, the amount of genome-wide aDNA analyses on ancient specimens from Egypt and Sudan remain scarce, although studies on uniparental haplogroups in ancient individuals have been carried out several times, pointing broadly to affinities with other African and Eurasian groups.[199][200]

The currently most advanced full genome analyses was made on three ancient specimens recovered from the Nile River Valley, Abusir el-Meleq, Egypt. Two of the individuals were dated to the Pre-Ptolemaic Period (New Kingdom to Late Period), and one individual to the Ptolemaic Period, spanning around 1300 years of Egyptian history. These results point to a genetic continuity of Ancient Egyptians with modern Egyptians. The results further point to a close genetic affinity between ancient Egyptians and Middle Eastern populations, especially ancient groups from the Levant.[199][200]

Ancient Egyptians also displayed affinities to Nubians to the south of Egypt, in modern-day Sudan. Archaeological and historical evidence support interactions between Egyptian and Nubian populations more than 5000 years ago, with socio-political dynamics between Egyptians and Nubians ranging from peaceful coexistence to variably successful attempts of conquest. A study on sixty-six ancient Nubian individuals revealed significant contact with ancient Egyptians, characterized by the presence of ح. 57% Neolithic/Bronze Age Levantine ancestry in these individuals. Such geneflow of Levantine-like ancestry corresponds with archaeological and botanic evidence, pointing to a Neolithic movement around 7,000 years ago.[199][200]

Modern Egyptians, like modern Nubians, also underwent subsequent admixture events, contributing both "Sub-Saharan" African-like and West Asian-like ancestries, since the Roman period, with significance on the African Slave Trade and the Spread of Islam.[199][200]

Some scholars, such as Christopher Ehret, caution that a wider sampling area is needed and argue that the current data is inconclusive on the origin of ancient Egyptians. They also point out issues with the previously used methodology such as the sampling size, comparative approach and a "biased interpretation" of the genetic data. They argue in favor for a link between Ancient Egypt and the northern Horn of Africa. This latter view has been attributed to the corresponding archaeological, genetic, linguistic and biological anthropological sources of evidence which broadly indicate that the earliest Egyptians and Nubians were the descendants of populations in northeast Africa.[201][202][203][198]

الذكرى

لقد تركت ثقافة وآثار مصر القديمة إرثاً دائماً للعالم. لقد أثرت الحضارة المصرية بشكل كبير على مملكة كوش ومروي من خلال تبني المعايير الدينية والمعمارية المصرية (بُنيت مئات الأهرامات (ارتفاعها 6-30 متراً) في مصر/السودان)، بالإضافة إلى استخدام الكتابة المصرية كأساس للكتابة المروية.[204] المروية هي أقدم لغة مكتوبة في أفريقيا، بعد اللغة المصرية، وقد استخدمت من القرن الثاني ق.م. حتى أوائل القرن الخامس الميلادي.[205] على سبيل المثال، أصبحت عبادة الإلهة إيزيس شائعة في الامبراطورية الرومانية، حيث نُقلت مسلات وآثار أخرى إلى روما.[206] كما استورد الرومان مواد البناء من مصر لبناء منشآت على الطراز المصري. وقد درس المؤرخون الأوائل مثل هيرودوت وسترابون وديودورس الصقلي وكتبوا عن هذه الأرض، التي اعتبرها الرومان مكاناً غامضاً.[207]

خلال العصور الوسطى وعصر النهضة، كانت الثقافة الوثنية المصرية في حالة تراجع بعد ظهور المسيحية والإسلام في وقت لاحق، لكن الاهتمام بالآثار المصرية استمر في كتابات علماء العصور الوسطى مثل ذو النون المصري والمقريزي.[208] في القرنين السابع عشر والثامن عشر، كان المسافرون والسياح الأوروپيون يجلبون معهم الآثار ويكتبون قصصاً عن رحلاتهم، مما أدى إلى موجة من الهوس بالمصريات في جميع أنحاء أوروپا، كما يتضح في الرمزية مثل عين العناية الإلهية وختم الولايات المتحدة العظيم. أدى هذا الاهتمام المتجدد إلى إرسال جامعي الآثار إلى مصر، الذين أخذوا أو اشتروا أو حصلوا على العديد من الآثار الهامة.[209] قام ناپليون بتنظيم الدراسات الأولى في علم المصريات عندما أحضر نحو 150 عالماً وفناناً لدراسة وتوثيق التاريخ الطبيعي لمصر، والذي نُشر في كتاب وصف مصر.[210]

في القرن العشرين، أدركت الحكومة المصرية وعلماء الآثار على حد سواء أهمية الاحترام الثقافي والنزاهة في أعمال التنقيب. ومنذ ع. 2010، أشرفت وزارة السياحة والآثار على أعمال التنقيب واستعادة القطع الأثرية.[211]

مسجد أبو الحجاج مدمج في معبد الأقصر منذ القرن الرابع عشر ق.م، مما جعله أقدم معبد مستخدم بشكل مستمر.

السياح في مجمع أهرامات خفرع بالقرب من أبي الهول في الجيزة.

انظر أيضاً

| الأسر الفرعونية بمصر القديمة |

| مصر قبل الأسرات |

| عصر نشأة الأسرات |

| عصر الأسر المبكرة |

| 1 - 2 |

| الدولة القديمة |

| 3 - 4 - 5 - 6 |

| الفترة الانتقالية الأولى |

| 7 - 8 - 9 - 10 - |

| 11 (طيبة فقط) |

| الدولة الوسطى |

| 11 (كل مصر) |

| 12 - 13 - 14 |

| الفترة الانتقالية الثانية |

| 15 - 16 - 17 |

| الدولة الحديثة |

| 18 - 19 - 20 |

| الفترة الانتقالية الثالثة |

| 21 - 22 - 23 - 24 - 25 |

| العصر المتأخر |

| 26 - 27 - 28 |

| 29 - 30 - 31 |

| العصر الإغريقي والروماني |

| بطالمة - الإمبراطورية الرومانية |

- علم المصريات

- معجم القطع الأثرية المصرية القديمة

- قائمة مقالات متعلقة بمصر القديمة

- موضوعات مصر القديمة

- قائمة المصريين القدماء

- قائمة الاختراعات والاكتشافات المصرية القديمة

- علم الآثار في مصر القديمة

- خريطة مصر الأثرية

- مدرسة الانتشار البريطانية

الهوامش

- ^ Depending on the definition, 332 BC with the end of the Late Period, 30 BC with the end of the Ptolemaic Kingdom

- ^ With the death of Ramesses XI

- ^ With his two principal wives and large harem, Ramesses II sired more than 100 children. (Clayton (1994), p. 146)

- ^ From Killebrew & Lehmann (2013), p. 2: "First coined in 1881 by the French Egyptologist G. Maspero (1896), the somewhat misleading term "Sea Peoples" encompasses the ethnonyms Lukka, Sherden, Shekelesh, Teresh, Eqwesh, Denyen, Sikil / Tjekker, Weshesh, and Peleset (Philistines). Footnote: The modern term "Sea Peoples" refers to peoples that appear in several New Kingdom Egyptian texts as originating from "islands"... The use of quotation marks in association with the term "Sea Peoples" in our title is intended to draw attention to the problematic nature of this commonly used term. It is noteworthy that the designation "of the sea" appears only in relation to the Sherden, Shekelesh, and Eqwesh. Subsequently, this term was applied somewhat indiscriminately to several additional ethnonyms, including the Philistines, who are portrayed in their earliest appearance as invaders from the north during the reigns of Merenptah and Ramesses III."

- From Drews (1993), pp. 48–61: "The thesis that a great "migration of the Sea Peoples" occurred ca. 1200 B.C. is supposedly based on Egyptian inscriptions, one from the reign of Merneptah and another from the reign of Ramesses III. Yet in the inscriptions themselves such a migration nowhere appears. After reviewing what the Egyptian texts have to say about 'the sea peoples', one Egyptologist (Wolfgang Helck) recently remarked that although some things are unclear, "eins ist aber sicher: Nach den agyptischen Texten haben wir es nicht mit einer 'Volkerwanderung' zu tun." Thus the migration hypothesis is based not on the inscriptions themselves but on their interpretation."

- ^ Figures are given for adult life expectancy and do not reflect life expectancy at birth. (Filer (1995), p. 25)

- ^ See Suez Canal.

- ^ Understanding of Egyptian mathematics is incomplete due to paucity of available material and lack of exhaustive study of the texts that have been uncovered (Imhausen (2007), p. 13).

الحواشي

- ^ Dodson & Hilton (2004), p. 46.

- ^ Clayton (1994), p. 217.

- ^ James (2005), p. 8; Manuelian (1998), pp. 6–7.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج Ward (2001).

- ^ Clayton (1994), p. 153.

- ^ James (2005), p. 84.

- ^ Shaw (2003), pp. 17, 67–69.

- ^ Shaw (2003), p. 17.

- ^ Ikram (1992), p. 5.

- ^ Hayes (1964), p. 220.

- ^ Kemp (1989), p. 14.

- ^ Aston, Harrell & Shaw (2000), pp. 46–47.

- ^ Aston (1994), pp. 23–26.

- ^ Ataç (2014), pp. 424–425.

- ^ Chronology of the Naqada Period (2001).

- ^ Shaw (2003), p. 61.

- ^ Shaw (2003), p. 61; Ataç (2014), pp. 424–425.

- ^ Nicholson & Peltenburg (2000), pp. 178–179.

- ^ Faience in different Periods (2000).

- ^ Allen (2000), p. 1.

- ^ Clayton (1994), p. 6.

- ^ Robins (2008), p. 32.

- ^ Clayton (1994), pp. 12–13.

- ^ Shaw (2003), p. 70.

- ^ Early Dynastic Egypt (2001).

- ^ James (2005), p. 40.

- ^ Shaw (2003), p. 102.

- ^ Shaw (2003), pp. 116–117.

- ^ Hassan (2011).

- ^ Clayton (1994), p. 69.

- ^ Shaw (2003), p. 120.

- ^ أ ب Shaw (2003), p. 146.

- ^ Clayton (1994), p. 29.

- ^ Guardian Figure 14.3.17 (2022).

- ^ Grajetzki 2007, pp. 41–54.

- ^ Shaw (2003), p. 148.

- ^ Clayton (1994), p. 79.

- ^ Shaw (2003), p. 158.

- ^ Shaw (2003), pp. 179–182.

- ^ Robins (2008), p. 90.

- ^ Shaw (2003), p. 188.

- ^ أ ب Ryholt (1997), p. 310.

- ^ Shaw (2003), p. 189.

- ^ Shaw (2003), p. 224.

- ^ Clayton (1994), pp. 104–107.

- ^ James (2005), p. 48.

- ^ Bleiberg (2005), p. 49–50.

- ^ Aldred (1988), p. 259.

- ^ O'Connor & Cline (2001), p. 273.

- ^ Tyldesley (2001), pp. 76–77.

- ^ James (2005), p. 54.

- ^ Cerny (1975), p. 645.

- ^ Bonnet (2006), p. 128.

- ^ Shaw (2003), p. 345.

- ^ Bonnet (2006), pp. 142–154.

- ^ Mokhtar (1990), pp. 161–163.

- ^ Emberling (2011), pp. 9–11.

- ^ Silverman (1997), pp. 36–37.

- ^ Shaw (2003), p. 358.

- ^ Shaw (2003), p. 383.

- ^ Shaw (2003), p. 385.

- ^ Shaw (2003), p. 405.

- ^ Shaw (2003), p. 411.

- ^ Shaw (2003), p. 418.

- ^ James (2005), p. 62.

- ^ James (2005), p. 63.

- ^ Shaw (2003), p. 426.

- ^ أ ب Shaw (2003), p. 422.

- ^ Shaw (2003), p. 431.

- ^ Chadwick (2001), p. 373.

- ^ MacMullen (1984), p. 63.

- ^ Shaw (2003), p. 445.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Manuelian (1998), p. 358.

- ^ Manuelian (1998), p. 363.

- ^ Egypt: Coins of the Ptolemies (2002).

- ^ Meskell (2004), p. 23.

- ^ أ ب ت Manuelian (1998), p. 372.

- ^ Turner (1984), p. 125.

- ^ Manuelian (1998), p. 383.

- ^ James (2005), p. 136.

- ^ Billard (1978), p. 109.

- ^ Social classes in ancient Egypt (2003).

- ^ أ ب ت Johnson (2002).

- ^ Slavery (2012).

- ^ Oakes & Gahlin (2003), p. 472.

- ^ McDowell (1999), p. 168.

- ^ Manuelian (1998), p. 361.

- ^ Nicholson & Shaw (2000), p. 514.

- ^ Nicholson & Shaw (2000), p. 506.

- ^ Nicholson & Shaw (2000), p. 510.

- ^ Nicholson & Shaw (2000), pp. 577, 630.

- ^ أ ب Strouhal (1989), p. 117.

- ^ أ ب Manuelian (1998), p. 381.

- ^ Nicholson & Shaw (2000), p. 409.

- ^ Heptner & Sludskii (1992), pp. 83–95.

- ^ Oakes & Gahlin (2003), p. 229.

- ^ Greaves & Little (1930), p. 123.

- ^ Lucas (1962), p. 413.

- ^ Nicholson & Shaw (2000), p. 28.

- ^ Hogan (2011), "Sulphur".

- ^ Scheel (1989), p. 14.

- ^ Nicholson & Shaw (2000), p. 166.

- ^ Nicholson & Shaw (2000), p. 51.

- ^ Shaw (2003), p. 72.

- ^ Porat (1992), pp. 433–440.

- ^ de Miroschedji & Sadeq (2008).

- ^ Porat (1986), pp. 109–129.

- ^ Egyptian pottery of the beginning of the First Dynasty, found in South Palestine (2000).

- ^ Shaw (2003), p. 322.

- ^ Manuelian (1998), p. 145.

- ^ Loprieno (1995b), p. 2137.

- ^ Loprieno (2004), p. 161.

- ^ Loprieno (2004), p. 162.

- ^ Loprieno (1995b), pp. 2137–2138.

- ^ Vittman (1991), pp. 197–227.

- ^ Loprieno (1995a), p. 46.

- ^ Loprieno (1995a), p. 74.

- ^ Loprieno (2004), p. 175.

- ^ Allen (2000), pp. 67, 70, 109.

- ^ Loprieno (1995b), p. 2147.

- ^ Loprieno (2004), p. 173.

- ^ Allen (2000), p. 13.

- ^ Loprieno (1995a), pp. 10–26.

- ^ Allen (2000), p. 7.

- ^ Loprieno (2004), p. 166.

- ^ El-Daly (2005), p. 164.

- ^ Allen (2000), p. 8.

- ^ Strouhal (1989), p. 235.

- ^ Lichtheim (1975), p. 11.

- ^ Lichtheim (1975), p. 215.

- ^ Day, Gordon & Williamson (1995), p. 23.

- ^ Lichtheim (1980), p. 159.

- ^ Manuelian (1998), p. 401.

- ^ Manuelian (1998), p. 403.

- ^ Manuelian (1998), p. 405.

- ^ Manuelian (1998), pp. 406–407.

- ^ Music in Ancient Egypt (2003).

- ^ Metcalfe (2018); Seaburn (2018).

- ^ Manuelian (1998), p. 126.

- ^ Hayes (1973), p. 380.

- ^ Manuelian (1998), pp. 399–400.

- ^ Clarke & Engelbach (1990), pp. 94–97.

- ^ Badawy (1968), p. 50.

- ^ Types of temples in ancient Egypt (2003).

- ^ Dodson (1991), p. 23.

- ^ Dodson & Ikram (2008), pp. 218, 275–276.

- ^ Robins (2008), p. 29.

- ^ Robins (2008), p. 21.