بونگ بونگ ماركوس

فرديناند ر. ماركوس الابن | |

|---|---|

الپورتريه الرسمي، 2022 | |

| رئيس الفلپين، رقم 17 | |

| تولى المنصب 30 يونيو 2022 | |

| نائب الرئيس | سارة دوترتي |

| سبقه | رودريگو دوترتي |

| وزير الزراعة | |

| في المنصب 30 يونيو 2022 – 3 نوفمبر 2023 | |

| الرئيس | نفسه |

| سبقه | وليام دار |

| خلـَفه | فرنسسكو تيو لورل الأصغر |

| عضو مجلس الشيوخ | |

| في المنصب 30 يونيو 2010 – 30 يونيو 2016 | |

| عضو مجلس النواب عن الدائرة الثانية، إلوكوس نورتى | |

| في المنصب 30 يونيو 2007 – 30 يونيو 2010 | |

| سبقه | إيمي ماركوس |

| خلـَفه | إملدا ماركوس |

| في المنصب 30 يونيو 1992 – 30 يونيو 1995 | |

| سبقه | ماريانو نالوپتا الأصغر |

| خلـَفه | سيميون ڤالديز |

| حاكم إلوكوس نورتى | |

| في المنصب 30 يونيو 1998 – 30 يونيو 2007 | |

| سبقه | رودولفو فاريناس |

| خلـَفه | مايكل ماركوس كيون |

| في المنصب 23 مارس 1983 – 25 فبراير 1986 | |

| سبقه | إليزابث كيون |

| خلـَفه | كاستور راڤال (OIC) |

| نائب حاكم إلوكوس نورتى | |

| في المنصب 30 يونيو 1980 – 23 مارس 1983 | |

| الحاكم | إليزابث كيون |

| سبقه | أنطونيو لازو |

| زعيم الحزب الفدرالي الفلپيني | |

| تولى المنصب 5 أكتوبر 2021 | |

| الرئيس | رينالدو تامايو الأصغر |

| سبقه | أبو بكر منگلن |

| تفاصيل شخصية | |

| وُلِد | فرديناند روموالديز ماركوس الأصغر 13 سبتمبر 1957 سانتا مـِسا، مانيلا، الفلپيين |

| الحزب | الحزب الفدرالي الفلپيني (2021–الحاضر) |

| ارتباطات سياسية أخرى | الحزب الوطني (2009–2021) حركة المجتمع الجديد (1978–2009) |

| الزوج | |

| الأنجال | 3، من بينهم ساندرو |

| الأم | إميلدا ماركوس |

| الأب | فرديناند ماركوس |

| الأقارب | عائلة ماركوس |

| الإقامة | |

| التعليم | مدرسة وورث (الثانوية) |

| المدرسة الأم |

|

| التوقيع |  |

| الموقع الإلكتروني | pbbm |

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

الحالي الحملات السياسية

Policies

مسيرته السياسية المبكرة

متعلقة |

||

فرديناند "بونگ بونگ" روموالديز ماركوس الأصغر[1][2] (UK: /ˈmɑːrkɒs/، US: /-koʊs, -kɔːs/،[3][4] تگالوگ: [ˈmaɾkɔs]؛ وشهرته بونگ بونگ ماركوس (Bongbong Marcos؛ و. 13 سبتمبر 1957)، يعُرف بالحروف الأولى PBBM أو BBM، هو سياسي فلپيني ورئيس الفلپين السابع عشر والحالي.[5][6][7] كان ماركوس عضواً في مجلس الشيوخ من 2010 حتى 2016. وهو ثاني أنجال والابن الوحيد للرئيس العاشر، الكلپتوقراطي والدكتاتور فرديناند ماركوس والسيدة الأولى السابقة إميلدا ماركوس.[1][8]

عام 1980، أصبح ماركوس نائب حاكم إلوكوس نورتى، وترشح بدون منافس عن حزب حركة المجتمع الجديد الذي أسسه والده، الذي كان يحكم الفلپين في ظل الأحكام العرفية في ذلك الوقت.[9] ثم أصبح حاكم إلوكوس نورتى عام 1983، وظل يشغل هذا المنصب حتى أطاحت ثورة شعبية بعائلته من السلطة، وفر إلى المنفى في هاواي في فبراير 1986.[10] بعد وفاة والده عام 1989، سمحت الرئيسة كورازن أكينو لعائلته في النهاية بالعودة إلى الفلپين لمواجهة اتهامات مختلفة.[11] كان ماركوس ووالدته إيميلدا يواجهان الاعتقال في الولايات المتحدة لتحديهما أمر المحكمة بدفع 353 مليون دولار (17.385.250.000 پـِسو) تعويضًا لضحايا انتهاكات حقوق الإنسان في عهد والده الدكتاتوري.[12]

انتُخب ماركوس عضواً في مجلس النواب عن دائرة إلوكوس نورتى الثانية من عام 1992 حتى 1995. وانتُخب حاكمًا لإلوكوس نورتى مرة أخرى عام 1998. وبعد تسع سنوات، عاد إلى منصبه السابق كعضو مجلس النواب من عام 2007 حتى 2010، ثم أصبح عضواً في مجلس الشيوخ عن الحزب الوطني من عام 2010 حتى 2016.[13] خاض ماركوس انتخابات 2016 لمنصب نائب الرئيس، حيث خسر أمام لني روبردو عضوة مجلس النواب عن دائرة كامارينس سور، بفارق 263.473 صوت؛[14] ردًا على ذلك، قدم ماركوس احتجاجًا انتخابيًا لدى المحكمة الانتخابية الرئاسية، لكن التماسه رُفض بالإجماع بعد أن أسفرت إعادة فرز الأصوات التجريبية عن تقدم روبردو بـ 15.093 صوتًا إضافيًا.[15][16]

ترشح ماركوس لمنصب رئيس الفلپين في انتخابات 2022 عن الحزب الفدرالي،[17] حيث فاز بأغلبية ساحقة[5] بنسبة 59% من الأصوات.[18][19] كان فوزه هو الأكبر منذ |1981، عندما فاز والده بنسبة 88% من الأصوات بسبب مقاطعة المعارضة التي احتجت على الانتخابات السابقة.[20][21][22]

وتلقت حملة ماركوس الانتخابية انتقادات من مدققي الحقائق ومتخصصي التضليل، الذين وجدوا أن حملته مدفوعة بالإنكار التاريخي بهدف إحياء إسم ماركوس وتشويه سمعة منافسيه.[23] كما اتُهمت حملته التدليس على انتهاكات حقوق الإنسان والنهب، والتي تقدر بنحو 5 إلى 13 بليون دولار، والتي حدثت أثناء رئاسة والده.[23] أشارت واشنطن پوست إلى أن التشويه التاريخي لعائلة ماركوس كان جارياً منذ ع. 2000، في حين استشهدت نيويورك تايمز بإداناته بالتهرب الضريبي، بما في ذلك رفضه دفع ضرائب التركات لعائلته، وادعاءه الدراسة في جامعة أكسفورد.[24][25][26][27] عام 2024، أدرجته مجلة تايم على قائمتها لأكثر 100 شخص نفوذاً في العالم.[28][29]

السنوات المبكرة والتعليم

Bongbong Marcos was born as Ferdinand Romualdez Marcos Jr. on September 13, 1957, at Our Lady of Lourdes Hospital in Santa Mesa, Manila, Philippines, to Ferdinand Marcos and Imelda Marcos. At the time of his birth, his father Ferdinand was the representative for the second district of Ilocos Norte, eventually becoming a senator just two years later. His godfathers included prominent personalities and future Marcos cronies Eduardo "Danding" Cojuangco Jr.[30] and pharmaceuticals magnate Jose Yao Campos.[31]

التعليم

Marcos first studied at the Institución Teresiana in Quezon City and La Salle Green Hills in Mandaluyong, where he obtained his kindergarten and elementary education, respectively.[32][33]

In 1970, Marcos was sent to England where he lived and studied at Worth School, an all-boys Benedictine institution in West Sussex.[1][34] He was studying there when his father declared martial law throughout the Philippines in 1972.[1][34]

Marcos attended the Center for Research and Communication, where he took a special diploma course in economics, but did not finish.[35][36] He then enrolled at St Edmund Hall, Oxford to study philosophy, politics and economics (PPE). However, despite his false claims that he graduated with a bachelor of arts in PPE,[37] he did not obtain such a degree.[38][39][40] Marcos had passed philosophy, but failed economics, and failed politics twice, thus making him ineligible for a degree.[41][42] Instead, he received a special diploma in social studies,[40] which was awarded mainly to non-graduates and is currently no longer offered by the university.[38][43] Marcos still falsely claims that he obtained a degree from the University of Oxford despite Oxford confirming in 2015 that Marcos did not finish his degree.[44]

Marcos enrolled in the Masters in Business Administration program at the Wharton School of Business, University of Pennsylvania, in Philadelphia, United States, which he failed to complete. Marcos asserts that he withdrew from the program for his election as Vice Governor of Ilocos Norte in 1980.[45] The Presidential Commission on Good Government later reported that his tuition, his US$10٬000 (₱قالب:From USD in 2026) monthly allowance, and the estate he lived in while studying at Wharton, were paid using funds that could be traced partly to the intelligence funds of the Office of the President, and partly to some of the fifteen bank accounts that the Marcoses had secretly opened in the US under assumed names.[46]

المناصب العامة المبكرة

Marcos was thrust into the national limelight as early as when he was three years old, and the scrutiny became even more intense when his father first ran for President of the Philippines in 1965,[47] when he was eight years old.[1][34][30]

During his father's 1965 campaign, Marcos played himself in the Sampaguita Pictures film Iginuhit ng Tadhana: The Ferdinand E. Marcos Story, a biopic based on the novel For Every Tear a Victory.[48][47] The young Marcos was portrayed giving a speech towards the end of the film, in which he says that he would like to be a politician when he grows up.[49] The public relations value of the film is credited for having helped the elder Marcos win the 1965 Philippine elections.[50]

A young Bongbong Marcos and his sister Imee played a small role in the controversial "Manila incident" of the Beatles in July 1966, just six months after their father assumed the presidency.[51][52] Bongbong and Imee were among 400 children whom their mother Imelda brought to Malacañang Palace for a reception in which they expected the Beatles to show up.[51] The four band members claimed not to know about the event, and refused to attend. As the event went on without them, the Marcos children were interviewed. Bongbong, referring to the group's long hair, was quoted saying "I'd like to pounce on the Beatles and cut off their hair! Don't anybody dare me to do anything, because I'll do it, just to see how game the Beatles are."[51] Imee, meantime, was quoted saying "There is only one song I like from the Beatles, and it's Run for Your Life."[51]—a quote which media later associated with the way the Beatles scrambled out of Manila, receiving rough treatment at the Manila International Airport.[51]

Beatles lead guitarist George Harrison later accused the Marcoses of inciting Filipinos to mob the band as they tried to leave the country for not showing up at the reception, saying in a 1986 interview at NBC's Today Show that the Marcoses "tried to kill [them]."[53][54] Harrison further said that their plane was not allowed to leave Manila until their manager, Brian Epstein, refunded the concert ticket money.[53][54]

The Manila Bulletin reported in 2015 that Marcos had once invited Beatles drummer Ringo Starr to return to the Philippines "to bring closure" to the incident.[55]

The incident was brought up in the media again after a 2021 interview between Marcos and Toni Gonzaga, when he was asked about which musicians he idolized, and he casually mentioned that he was friends with Mick Jagger of the Rolling Stones and members of the Beatles.[53]

Marcos was still a minor on the exact year that martial law was declared. Marcos turned 18 in 1975[56][57]—a year after he graduated from Worth School.[58]

مناصب في نظام ماركوس

نائب حاكم وحاكم إلوكوس نورتى

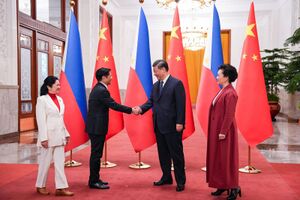

Marcos's first formal role in a political office came with his election as Vice Governor of Ilocos Norte (1980–1983) at the age of 22. On March 23, 1983, he was installed as the Governor of Ilocos Norte, replacing his aunt Elizabeth Marcos-Keon, who had resigned from the post for health reasons.[59] In 1983, he led a group of young Filipino leaders on a 10-day diplomatic mission to China to mark the tenth anniversary of Philippine-Chinese relations.[60] He stayed in office until the People Power Revolution in 1986.

During Marcos's term, at least two extrajudicial killings took place in Ilocos Norte, as documented by the Martial Law Victims Association of Ilocos Norte (MLVAIN).[61][62]

رئاسة مجلس إدارة فيلوكومسات

Marcos was appointed by his father to be chairman of the board of the Philippine Communications Satellite Corporation (PHILCOMSAT) in early 1985.[63] In a prominent example of what Finance Minister Jaime Ongpin later branded "crony capitalism", the Marcos administration had sold its majority shares to Marcos cronies such as Roberto S. Benedicto,[64] Manuel H. Nieto,[64] Jose Yao Campos,[65] and Rolando Gapud[65] in 1982, despite being very profitable because of its role as the sole agent for the Philippines' link to global satellite network Intelsat.[64] President Marcos acquired a 39.9% share in the company through front companies under Campos and Gapud.[65] This allowed President Marcos to appoint his son as the chairman of the Philcomsat board in early 1985, allowing the young Marcos to draw a monthly salary "ranging from US$9٬700 to US$97٬000"[63][64] (₱قالب:From USD to ₱قالب:From USD in 2026) despite rarely visiting the office and having no duties there.[64][63] PHILCOMSAT was one of five telecommunications firms sequestered by the Philippine government in 1986.[64]

ثروة العائلة الغير مشروعة

After the Marcos family went into exile in 1986, the Presidential Commission on Good Government found that the three Marcos children benefited significantly[46][63][66] from what the Supreme Court of the Philippines defined as "ill-gotten wealth" of the Marcos family.[67][68][69]

Aside from the tuition, US$10,000.00 (₱قالب:From USD in 2026) monthly allowance, and the estates used by Marcos Jr. and Imee Marcos during their respective studies at Wharton and Princeton,[46] each of the Marcos children was assigned a mansion in the Metro Manila area, as well as in Baguio, the Philippines' designated summer capital.[46] Properties specifically said to have been given to Marcos Jr. included the Wigwam House compound on Outlook Drive in Baguio[46] and the Seaside Mansion Compound in Parañaque.[46]

In addition, by the time their father was ousted from power in 1986, both Marcos Jr. and Imee held key posts in the Marcos administration.[63] Imee was already thirty when she was appointed as the national head of the Kabataang Barangay in the late 1970s,[63] and Marcos Jr. was in his twenties when he took up the vice-gubernatorial post for the province of Ilocos Norte in 1980, and then became governor of that province from 1983 until the Marcos family was ousted from Malacañang in 1986.[63]

الثورة الشعبية والمنفى (1986–1991)

During the last days of the 1986 People Power Revolution, Bongbong Marcos, in combat fatigues to project his warlike stance,[70] pushed his father Ferdinand Marcos to give the order to his remaining troops to attack and blow up Camp Crame despite the presence of hundreds of thousands of civilians there. The elder Marcos did not follow his son's urgings.[71]

Fearful of a scenario in which Marcos's presence in the Philippines would lead to a civil war,[72] the Reagan administration withdrew its support for the Marcos government, and flew Marcos and a party of about 80 individuals[10] – the extended Marcos family and a number of close associates[73] – from the Philippines to Hawaii despite Ferdinand Marcos's objections.[72] Bongbong Marcos and his family were on the flight with his parents.[74][75]

Soon after arriving in Hawaii, the younger Marcos participated in an attempt to withdraw US$200 million (₱قالب:From USD in 2026) from a secret family bank account with Credit Suisse in Switzerland,[76] an act which eventually led to the Swiss government freezing the Marcoses' bank accounts in late March that year.[77]

The Marcoses initially stayed at Hickam Air Force Base at the expense of the U.S. government. A month after arriving in Honolulu, they moved into a pair of residences in Makiki Heights, Honolulu, which were registered to Marcos cronies Antonio Floirendo and Bienvenido and Gliceria Tantoco.[10]

Ferdinand Marcos eventually died in exile three years later, in 1989,[78] with Marcos Jr. being the only family member present at his father's deathbed.[79]

العودة للفلپين والأنشطة اللاحقة (1991–الحاضر)

After his father's death in 1989, President Corazon Aquino permitted the return of the remaining members of the Marcos family to the Philippines to face various charges.[11] Bongbong Marcos was among the first to return to the Philippines. He arrived in the country in 1991 and soon sought political office, beginning in the family's traditional fiefdom in Ilocos Norte.[80]

مجلس النواب، الفترة الأولى

After Marcos returned to the Philippines in 1991, Marcos ran for and was elected representative of the second district of Ilocos Norte to the Philippine House of Representatives (1992–1995).[81] When his mother, Imelda Marcos, ran for president in the same election, he decided against supporting her candidacy, and instead expressed support for his godfather Danding Cojuangco.[82] During his term, Marcos was the author of 29 House bills and co-author of 90 more, which includes those that paved the way for the creation of the Department of Energy and the National Youth Commission.[83] He also allocated most of his Countryside Development Fund (CDF) to organizing the cooperatives of teachers and farmers in his home province.[84][85][مطلوب مصدر أفضل] In October 1992, he led a group of ten representatives in attending the first sports summit in the Philippines, held in Baguio.[86] In late 1994, he was made president of the Kilusang Bagong Lipunan party, which is known for its support for the Marcos regime.[87]

In 1995, Marcos ran for the Senate under the NPC-led coalition but lost, placing only 16th.[88]

محاولة التوصل لصفقة تسوية

In 1995, Bongbong Marcos pushed a deal to allow the Marcos family to keep a quarter of the estimated US$2 billion to US$10 billion (₱قالب:From USD to ₱قالب:From USD in 2026) that the Philippine government had still not recovered from them, on the condition that all civil cases be dropped – a deal that was eventually struck down by the Philippines' Supreme Court.[76]

حاكم ألوكوس نورت، الفترة الثانية

Having previously served as Ilocos Norte governor from 1983 to 1986, Marcos was again elected as governor of Ilocos Norte in 1998, running against his father's closest friend and ally, Roque Ablan Jr. He served for three consecutive terms ending in 2007.[89]

مجلس النواب، الفترة الثانية

In 2007, Marcos ran unopposed for the congressional seat previously held by his older sister Imee.[90] He was then appointed as deputy minority leader of the House of Representatives. During this term, Marcos supported the passage of the Philippine Archipelagic Baselines Law, or Republic Act No. 9522.[91] He also wrote his own version of the law, but the bill only remained in the House Committee on Foreign Affairs.[83][92] He also promoted the Republic Act No. 9502 (Universally Accessible Cheaper and Quality Medicines Act) which was enacted on 2009.[93]

مجلس الشيوخ

Marcos made a second attempt for the Senate in 2010. On November 20, 2009, the KBL forged an alliance with the Nacionalista Party (NP) between Marcos and NP chair Senator Manny Villar at the Laurel House in Mandaluyong. Marcos became a guest senatorial candidate of the NP through this alliance.[94] Marcos was later removed as a member by the KBL National Executive Committee on November 23, 2009.[95] As such, the NP broke its alliance with the KBL due to internal conflicts within the party, however Marcos remained part of the NP senatorial lineup.[94] He was proclaimed as one of the winning senatorial candidates of the 2010 senate elections. He took office on June 30, 2010.

In the 15th Congress (2010–2013), Marcos authored 34 Senate bills. He also co-authored 17 bills of which seven were enacted into law[83] – most notably the Anti-Drunk and Drugged Driving Act whose principal author was Senator Vicente Sotto III; the Cybercrime Prevention Act whose principal author was Senator Edgardo Angara; and the Expanded Anti-Trafficking in Persons and the National Health Insurance Acts, both of which were principally authored by Senator Loren Legarda.

In the 16th Congress (2013–2016), Marcos filed 52 bills, of which 28 were refiled from the 15th Congress. One of them was enacted into law: Senate Bill No. 1186, which sought the postponement of the 2013 Sangguniang Kabataan (SK) elections, was enacted as Republic Act No. 10632 on October 3, 2013.[83]

Marcos also co-authored 4 Senate bills in the 16th Congress. One of them, Senate Bill No. 712 which was principally authored by Ralph Recto, was enacted as Republic Act No. 10645, the Expanded Senior Citizens Act of 2010.[83][96]

He was the chair of the Senate committees on urban planning, housing and resettlement, local government, and public works.[97] He also chaired the oversight committee on the Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (ARMM) Organic Act, the congressional oversight panel on the Special Purpose Vehicle Act, and a select oversight committee on barangay affairs.[32][98][مطلوب مصدر أفضل][dead link]

احتيال 2014

In 2014, Bongbong Marcos was implicated by Janet Lim Napoles[99] and Benhur Luy[100] in the Priority Development Assistance Fund (PDAF) Pork Barrel scam through agent Catherine Mae "Maya" Santos.[101] He allegedly channeled ₱100 million through 4 fake NGOs linked with Napoles.[102] Marcos claimed that the large amounts of money was released by the budget department without his knowledge and that his signatures were forged.[103] In connection to the PDAF scam, Marcos was also sued for plunder by iBalik ang Bilyones ng Mamamayan [ك] (iBBM [ك]), an alliance of youth organizations. The group cited Luy's digital files, which showed bogus NGOs with shady or non-existent offices.[104]

دعوى لجنة التدقيق 2016

In 2016, Marcos was also sued for plunder for funneling ₱205 million of his PDAF via 9 special allotment release orders (SARO) to the following bogus foundations from October 2011 to January 2013, according to Luy's digital files:[104]

- Social Development Program for Farmers Foundation (SDPFFI) – ₱15 million

- Countrywide Agri and Rural Economic Development Foundation (CARED) – ₱35 million

- People's Organization for Progress and Development Foundation (POPDFI) – ₱40 million

- Health Education Assistance Resettlement Training Services (HEARTS) – ₱10 million

- Kaupdanan Para Sa Mangunguma Foundation (KMFI) – ₱20 million

- National Livelihood Development Corporation (NLDC) – ₱100 million

These NGOs were found by the Commission on Audit (COA) as bogus with shady or non-existent offices.[104]

حملة انتخابات 2016 لمنصب نائب الرئيس

On October 5, 2015, Marcos announced via his website that he would run for Vice President of the Philippines in the 2016 general election, stating "I have decided to run for vice president in the May 2016 elections."[14][105] Marcos ran as an independent candidate.[106] Prior to his announcement, he had declined an invitation by presidential candidate, Vice President Jejomar Binay, to become his running mate.[107] On October 15, 2015, presidential candidate Miriam Defensor Santiago confirmed that Marcos would serve as her running mate.[108]

Marcos placed second in the tightly contested vice presidential race losing to Camarines Sur 3rd district Representative Leni Robredo, who won by a margin of 263,473 votes,[109][110] one of the closest since Fernando Lopez's victory in the 1965 vice presidential election.

الاحتجاجات على نتائج الانتخابات

Marcos challenged the results of the election, lodging an electoral protest against Leni Robredo on June 29, 2016, the day before Robredo's oathtaking.[111][112] President Rodrigo Duterte has stated several times that he would resign if Marcos would be his successor instead of Vice President Leni Robredo.[113]

A recount began in April 2018, covering polling precincts in Iloilo and Camarines Sur, which were areas handpicked by Marcos's camp. In October 2019, the tribunal found that Robredo's lead grew by around 15,000 votes – a total of 278,566 votes from Robredo's original lead of 263,473 votes – after a recount of ballots from the 5,415 clustered precincts in Marcos's identified pilot provinces.[114] On February 16, 2021, the Presidential Electoral Tribunal (PET) unanimously dismissed Bongbong Marcos's electoral protest against Leni Robredo.[15][16][115][116]

الانتخابات الرئاسية 2022

Marcos officially launched his campaign for president of the Philippines on October 5, 2021, through a video post on Facebook and YouTube.[117][118] An interview with his wife Liza Marcos revealed that he decided to run for president while watching the film Ant-Man,[119][120] though Marcos admitted that he could not recall this moment.[121] He ran under the banner of the Partido Federal ng Pilipinas party, assuming chairmanship of the party on the same day,[122] while also being endorsed by his former party, the Kilusang Bagong Lipunan.[123] Marcos filed his certificate of candidacy before the Commission on Elections the following day.[124] On November 16, Marcos announced his running mate to be Davao City mayor Sara Duterte, daughter of President Rodrigo Duterte.[125] Under the campaign theme of unity, Marcos and Duterte's alliance was given the name "UniTeam".[125]

Seven petitions were filed against Marcos's presidential bid.[126][127] Three petitions aimed to cancel Marcos's certificate of candidacy (COC), one petition aimed to declare Marcos a nuisance candidate, and three petitions aim to disqualify him. Most petitions are based on Marcos's 1995 conviction for failing to file tax returns. Three disqualification petitions were consolidated and raffled to the commission's first division, while three other petitions were handed to the second division.[126][128] The final petition was also handed to the first division. Marcos dismissed the petitions as nuisance petitions with no legal basis and propaganda against him.[129]

Marcos regularly maintained a wide lead in presidential surveys throughout the months leading up to the May 2022 election;[131][132] he was the first presidential candidate in the country to attain poll ratings of over 50% from surveys conducted by Pulse Asia since it began polling in 1999.[133] His refrainment from attending all but one of the presidential debates during the campaign season was widely criticized.[134][135][136][137]

In a joint session of the 18th Congress of the Philippines, overseen by Senate President Tito Sotto and House Speaker Lord Allan Velasco and stated by Senate Majority Leader Migz Zubiri and Majority Floor Leader Martin Romualdez, Marcos was proclaimed the president-elect of the Philippines on May 25, 2022, alongside his running-mate, Vice-President-elect Sara Duterte. Marcos received 31,629,783 votes, or 58.77% of the total votes cast, about 16.5 million votes ahead of his closest rival, Vice President Leni Robredo, who received over 15 million votes.[138] He became the first presidential candidate to be elected by a majority since the establishment of the Fifth Republic in 1986.[18][19][139] According to analysts, Marcos, together with Sara Duterte, "inherited" Rodrigo Duterte's popularity when they both won landslides in the election.[140] Historians noted the significance of his victory as a "full circle" of the Philippines from the People Power Revolution, which deposed his father from the presidency, thus marking the Marcos family's return to national power after 36 years.[5][141][142] His majority was the largest since 1981 (surpassing his father's 18,309,360 votes); as the opposition boycotted that election, it is the largest majority since 1969 for a competitive election, and his 31-percentage point margin over his nearest opponent was the greatest since Ramon Magsaysay scored a 38-point margin over incumbent President Elpidio Quirino in 1953. His vote count was not only the largest ever recorded in a presidential election, but close to the sum total of the two previous records combined.

On June 20, 2022, Marcos announced that he will serve as the Secretary of Agriculture in concurrent capacity.[143]

الرئاسة (2022–الحاضر)

| Presidental styles of بونج بونج ماركوس | |

| |

| Reference style | President Marcos Jr., His Excellency |

|---|---|

| لقب التحدث | Your Excellency |

| لقب بديل | Mr. President |

القرارات المبكرة

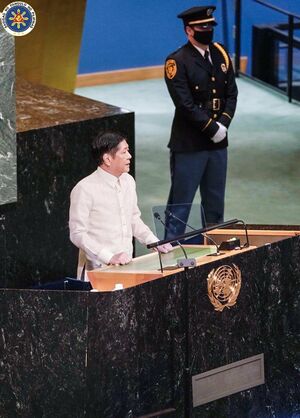

On June 30, 2022, at 12:00 noon PST, Marcos Jr. took the oath of office as the 17th President of the Philippines at the National Museum of the Philippines and was administered the oath by Chief Justice Alexander Gesmundo.[144][145] At concurrent capacity, Marcos appointed himself as Secretary of Agriculture, in order to address inflation and personally monitor the food and agricultural sectors, while enacting efforts to boost farm outputs through various loan programs, affordable pricing measures, and machinery assistance.[146] Marcos's first executive order as president were abolishing two offices: the Presidential Anti Corruption Commission and the Office of the Cabinet Secretary.[147]

The next day after his inauguration, Marcos signed a memorandum seeking to provide free train rides to students, and extends the free rides of the EDSA Carousel until the end of December 2022.[148] Twelve days later, on July 13, 2022, Marcos announced that the free train rides will only be limited to students using the LRT Line 2, due to the line's access points to the University Belt.[149]

Two days after his inauguration, on July 2, 2022, Marcos vetoed a bill sponsored by his sister Senator Imee Marcos that aimed to create a free economic zone within New Manila International Airport. Bongbong Marcos said that the bill would cite "substantial fiscal risks", lacked coherences with existing laws, and the proposed economic zone's location near the existing Clark Freeport and Special Economic Zone; Marcos also called for further studies in establishing the planned economic zone.[150] On the same day, Marcos also ordered that the list of Pantawid Pamilyang Pilipino Program beneficiaries to be cleansed after receiving reports of unqualified beneficiaries receiving cash assistance grants and downturned calls to surrender their accounts.

On July 5, 2022, five days after his inauguration, Marcos held his first cabinet meeting, which was delayed during his inauguration, and laid out his first agenda, which primarily focuses on reviving the economy in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic. During the meeting, Marcos led the discussions with his economic managers, Finance Secretary Benjamin Diokno, National Economic and Development Authority Secretary Arsenio Balisacan, and Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas Governor Felipe Medalla, to give a briefing about the country's economic status, and to lay out plans to further revive the country's economy, while combating inflation.[151][152][153] Marcos also tackled issues regarding food security, transportation issues, and the reopening of face-to-face classes within the year.[151] On July 23, 2022, Marcos has vetoed a bill which seeks to strengthen the Office of the Government Corporate Counsel (OGCC), as he cited that several provisions of the bill are "inequitable".[154][155]

On July 25, 2022, the same day of his first State of the Nation Address, Marcos allowed Republic Act No. 11900, known as the Vaporized Nicotine and Non-Nicotine Products Regulation Act to lapse into law. The law became controversial, due to the hounding health risks regarding the usage of electronic cigarettes and heated tobacco products.[156] In an effort to boost the country's booster shot campaign, Marcos launched the "PinasLakas" campaign to continue administering COVID-19 booster doses within the public, by targeting a total of at least 39 million Filipinos to get their booster shots.[157]

Two days after his first State of the Nation Address, following a meeting with Solicitor General Menardo Guevarra, Presidential Legal Adviser Juan Ponce Enrile, Executive Secretary Vic Rodriguez, Foreign Affairs Secretary Enrique Manalo, Justice Secretary Jesus Crispin Remulla, and former presidential spokesman and lawyer Harry Roque on July 27, 2022, Marcos expressed that the Philippines has no intention of rejoining the International Criminal Court, as the death cases linked to the country's drug war of his predecessor's administration are already being investigated by the government, and stated that the government is taking the necessary steps regarding the deaths.[158] On July 30, 2022, Marcos vetoed a bill which grants tax exemption on poll workers' honoraria and the creation of a transport safety board, stating that the honoraria "counters the objective of the government's Comprehensive Tax Reform Program", while mentioning that the proposed creation of a transport safety board "undertakes the functions by the different agencies" within the transport sector.[159][160]

السياسة الداخلية

الزراعة والإصلاح الزراعي

Subsequently serving as the Secretary of Agriculture, Marcos launched initiatives which aims to improve domestic agricultural output and production, while expanding measures to further establish a farm-to-market approach in providing agricultural products to local markets and far flung areas.[161][162] In August 2022, as high sugar prices impacted the country due to the effects of Typhoon Odette in December 2021, the Sugar Regulatory Administration (SRA) in August 2022 released an order to import 300،000 metric ton (660،000،000 lb) of sugar, which is aimed to reduce costs and increase the sugar stockpiles. A few days later, Marcos rejected the proposed importation, [163] and Malacañang deemed the move as illegal, as the move was made without Marcos's approval, nor signed by him.[164] SRA Undersecretary Leocadio Sebastian later apologized for the move and later resigned his post on Marcos; behalf,[165] prompting SRA Administrator Hermenegildo Serafica and SRA board member Roland Beltran to follow suit a few days later.[166] The move also caused Malacañang to instigate reforms within the SRA organization, [167] and launched a campaign into alleged efforts of using the sugar order as a "cover measure" for hoarding by sugar traders.[168]

In November 2022, Marcos expanded the Kadiwa Project launched by the Duterte administration, which aims to offer fresh local produces to local markets and other key areas in lower prices, and creates a direct farm-to-market approach of goods and services.[169][170] The programs is located in various areas throughout the country and temporarily occupies various facilities owned by local governments. The move is also aimed to be expanded permanently to accommodate more consumers affected by inflation.[171]

In January 2023, amid rising prices of onions in the country, Marcos approved the importation of 21،060 metric ton (46،430،000 lb) of onions to cater the gap caused by low local outputs,[172] and stated that the government was "left without a choice" despite approving the smuggled onions to be supplied in local markets.[173]

Marcos signed his fourth executive order on September 14, 2022, which establishes a one-year moratorium on the amortization and interest payments of agrarian reform beneficiaries. The move is seen to assist farmers from debt payments and allows a flexible approach in financial assistance.[174]

In July 2023, Marcos signed the New Agrarian Emancipation Act, freeing at least 600,000 agrarian reform beneficiaries of decades-old debts worth ₱57-billion under the Comprehensive Agrarian Reform Program.[175]

After serving as Secretary of Agriculture for over a year that was marked by a rise in food prices, Marcos relinquished his position and appointed Francisco Tiu Laurel Jr., president of a deep-sea fishing company and a donor to Marcos' 2022 presidential election campaign.[176]

الدفاع

In August 2022, the Marcos administration said it was considering ordering helicopters from the United States military, such as the Boeing CH-47 Chinook, to replace the 16 Russian Mil Mi-17 military helicopters purchased by the Duterte administration, but cancelled the program a few days before the end of Duterte's term out of concerns about existing United States sanctions such as the Countering America's Adversaries Through Sanctions Act (CAATSA) and possible future sanctions in response to the ongoing 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine. Negotiations are also ongoing to procure limited units which was paid by the government to Rosoboronexport.[177][178]

Marcos expressed support for the AFP Modernization Program,[179] which aims to boost the country's defense capabilities. Stating that the country's external security situation is becoming "more complex and unpredictable", Marcos ordered the Armed Forces of the Philippines to shift its focus on its defense operations against external threats, due to the lower risks in the country's insurgencies, the Russian invasion of Ukraine, and the potential Chinese invasion of Taiwan.[180][181]

During the 125th-anniversary celebration of the Philippine Navy, Marcos announced plans to acquire the Philippines' first submarine. The French-based Naval Group, along with other contenders, has offered its Scorpène-class submarines to strengthen the Navy.[182]

With an aim to enhance the country's defense capabilities, Marcos has approved the "Re-Horizon 3" of the AFP Modernization Program, which is also known as the RAFMP. The $35 billion plan revised modernization program will be spread out over 10 years and aims to modernize the Armed Forces of the Philippines based on the Comprehensive Archipelagic Defense Concept (CADC), a defense concept aimed at strengthening the country's external defense deterrence by projecting power within the Philippine's 200 nautical mile exclusive economic zone, Benham Rise, the Luzon Strait, and the Sulu Sea through inter-island defenses doctrines, multi-layered domain strategies, and long-range strike capabilities.[183] The concept also aims to strengthen the country's aerial and maritime domain awareness, connectivity, and intelligence capabilities.[184][185][186]

التعليم

In August 2022, despite the low COVID-19 vaccination rate among Filipino students with a total vaccination rate of only 19%, Marcos, along with Vice President and Education Secretary Sara Duterte, reopened onsite classes throughout the country, with 46% or 24,000 schools throughout the country reopening their classes on August 22. Meanwhile, 29,721 schools were allowed to continue implementing blended learning from August to October 2022,[187] while the full implementation of onsite classes began within November 2022, with 97.5% of public schools returning to onsite classes, while the remaining 2.36% of classes were temporarily held online due to the effects of Severe Tropical Storm Paeng.[188]

Marcos also reviewed the implementation of the K–12 program as part of his push to modernize the country's education system, and laid out measures such as system reforms to address the lack of jobs and potential job mismatches, reviewing the usage of English as a medium of instruction in schools, and improving the country's education technology systems.[189][190] Marcos also expressed his support to modernize the country's schools by improving science-related subjects and courses, theoretical aptitude, and vocational skills.[191][192]

الاقتصاد

Marcos prioritized the revival of the country's economy in the aftermath of the lockdowns and restrictions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic in the country, and laid out his eight-point economic agenda aimed to address the country's economic problems in the medium term, which included food security, supply chain management, decreasing energy costs and preserving energy security, reducing economic vulnerability from the pandemic by addressing health care issues and strengthening social protection, infrastructure development, creating a green economy, strengthening market competition, and promoting entrepreneurship.[193]

During his first State of the Nation Address, Marcos laid out his administration's economic vision and targets throughout his term, such as a 6.5 to 7.5% real gross domestic product (GDP) growth rate, with a 6.5 to 8% annual real GDP growth rate, a 9% or single-digit poverty rate by 2028, a 3% national government deficit-to-GDP ratio by 2028, lowering the country's debt-to-GDP ratio to less than 60% by 2025, and securing an upper middle-income status by 2024 with a US$4,256 income per capita, which is part of his 2023–2028 fiscal strategy. Marcos also supports the creation of additional economic zones in various areas of the country to attract investments in manufacturing, healthcare, and technology, and laid out plans to impose digital taxes and improve the country's tax compliance procedures which should improve revenue collections and cut the country's debts, while maintaining the country's disbursements at above 20 percent of its GDP.[194][195]

التمرد

الاتصالات

السياسة الخارجية

Early in his presidency, Marcos promised to continue his predecessor Rodrigo Duterte's foreign policy of being "friends to all, enemies to none".[196] Marcos initially sought closer ties with China,[197] but has since been increasingly seen as more pro-American than Duterte in an attempt to create a centrist-style balancing act between the two superpowers.[198][199][200][201][202] During his first State of the Nation Address, Marcos promised to "not preside over any process that will abandon even one-square inch of territory of the Republic of the Philippines to any foreign power".[203]

Under his presidency, Marcos intensified the Philippines' cooperation on both economic and defense arrangements to Western countries, such as the United States, Japan, Australia, and the European Union, while strengthening its defense posture within the region.[204][205] Marcos approved the designation of four additional bases to be used by the United States military under the Enhanced Defense Cooperation Agreement.[206] In May 2024, the Philippines and the United States held its largest Balikatan military exercises, fueling concerns from local civilians who fear they would be affected in any future war between the US and China.[207] The deployment of the United States' Typhon Weapons System in an undisclosed location in northern Luzon also caught the attention of Russian president Vladimir Putin, who said that Russia should resume producing nuclear-capable missiles and consider where to deploy them.[208]

Marcos called on all involved parties on the South China Sea to abide by the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea in order to diffuse potential conflicts in the future.[209] Due to Marcos' "transparency thrust" in dealing with the aggressive actions of the Chinese Coast Guard and the Chinese Maritime Militia, China–Philippines relations have significantly deteriorated during Marcos's tenure, with increasing tensions over territorial disputes in the South China Sea[210][211] and the Philippines withdrawing from the Belt and Road initiative.[212]

دعاوى قضائية

إدانات في قضايا ضريبة الدخل والعقارات

On June 27, 1990, a special tax audit team of the Bureau of Internal Revenue (BIR) investigated the tax liabilities and obligations of the late Ferdinand Marcos Sr., who died on September 29, 1989. The investigation disclosed in a 1991 memorandum that the Marcos family had failed to file estate tax returns and several income tax returns covering the years of 1982 to 1986 in violation of the National Internal Revenue Code.[213]

The BIR also issued a deficiency estate tax assessment against the estate of the late Ferdinand Marcos Sr. in 1991 for unpaid estate taxes from 1982 to 1985, and 1985 to 1986, totaling ₱23٬293٬607٬638 (₱97٬792٬696٬739 in 2022). Formal assessment notices were served to Bongbong Marcos at his office at the Batasang Pambansa Complex on October 20, 1992, who was then the representative of the 2nd District of Ilocos Norte. Several notices of levy were also issued by the BIR February 22, 1993, to May 26, 1993, to satisfy the deficiency of estate tax returns, to no avail.[213]

On March 12, 1993, lawyer Loreto Ata, representing Bongbong Marcos, called the attention of the BIR to notify them of any action taken by the BIR against his client. Bongbong Marcos then filed an instant petition on June 25, 1993, for certiorari and prohibition to contest the estate tax deficiency assessment.[213]

On July 27, 1995, Quezon City Regional Trial Court Judge Benedicto Ulep convicted Marcos to seven years in jail and a fine of US$2,812 (₱قالب:From USD in 2026) plus back taxes for tax evasion in his failure to file an income tax return from the period of 1982 to 1985 while sitting as the vice governor of Ilocos Norte (1980–1983) and as governor of Ilocos Norte (1983–1986).[214] Marcos subsequently appealed the decision to the Court of Appeals over his conviction. However, in 1994, the Court of Appeals ruled that the estate tax deficiency assessment had become "final and unappealable", allowing it to be enforced.[215]

On October 31, 1997, the Court of Appeals affirmed its earlier decision with Marcos being convicted for the failure of the filing of an income tax return under Section 45 of the National Internal Revenue Code of 1977 while being acquitted of tax evasion under the charge of violating Section 50 of the same statute. In spite of the removal of the penalty of imprisonment, Marcos was ordered the payment of back income taxes to the Bureau of Internal Revenue (BIR) with interest and the issuance of corresponding fines of ₱2٬000 per count of non-filing of income tax returns from 1982 to 1984 and ₱30٬000 for 1985, plus the accrued interest.[216] Marcos later filed a petition for certiorari to the Supreme Court of the Philippines over the modified conviction imposed by the Court of Appeals but subsequently withdrew his petition on August 8, 2001, thereby declaring the ruling as final and executory.[217]

In 2021, the Quezon City Regional Trial Court certified that there were no records on file of Marcos settling the corresponding tax dues and fines.[218][219] However, according to Marcos's campaign team, documents issued by the Supreme Court, the BIR, and a receipt issued by the Land Bank of the Philippines state that the tax dues were paid,[220][221] while elections commissioner Rowena Guanzon noted that the documents Marcos submitted to the Commission on Elections were not receipts of taxes paid to the BIR but rather receipts from the Land Bank for lease rentals.[222][223] Nevertheless, the Commission on Elections ruled against the consolidated disqualification cases against Marcos and stated that "Further, to prove the absence of any ill-intention and bad faith on his part," Marcos submitted a Bureau of Internal Revenue certification and an official receipt from the Landbank, showing his compliance with the CA decision directing him to pay deficiency income taxes amounting to a little over ₱67٬000, including fines and surcharges.[224]

The estate tax deficiency assessment issued by the BIR has remained uncollected since the Supreme Court ruling on October 12, 1991. Since the ruling of the Supreme Court in 1997 which had junked the petition of Marcos to contest the estate tax deficiency assessment, under the Ramos, Arroyo, Aquino, and Duterte administrations, the BIR has issued renewed written demands on the Marcos family to pay the estate tax liabilities, which has remained unpaid. As a result, the estate tax deficiency assessment, with penalties, is estimated to have ballooned to ₱203٬819٬066٬829 (₱203٫819 billion) as of 2021.[225]

The unpaid estate tax return was used as grounds in one petition to cancel Marcos's certificate of candidacy for president in the 2022 elections. On March 1, 2022, presidential candidate and Manila mayor Isko Moreno said that he would implement the Supreme Court ruling ordering the Marcos family to pay their estate tax debts if elected, vowing to use the proceeds as relief aid (ayuda) for victims of the COVID-19 pandemic.[215] On March 28, 2022, Senator Aquilino Pimentel III filed Senate Resolution No. 998, stating an urgent and pressing need for the Senate to look into why the estate tax has remained uncollected for almost 25 years, which the amount has already been ruled to be due and demandable against the heirs of his father.[226]

2007 Payanig sa Pasig property case motion

On June 19, 2007,[227] Marcos Jr. filed a motion to intervene in, OCLP v. PCGG, Civil Case Number 0093 at the Sandiganbayan, the Philippines' anti-graft court.[227] The case had been filed by Ortigas & Company, Ltd. Partnership (OCLP) against the Presidential Commission on Good Government (PCGG) over the 18-هكتار (44-acre) former Payanig sa Pasig property bordering Ortigas Avenue, Julia Vargas Avenue, and Meralco Avenue in Ortigas Center, Pasig, which had been the site of the 'Payanig sa Pasig' theme park, but is now the location of various businesses, most notably the Metrowalk shopping and recreation complex.[228]

The PCGG considers the property the "crown jewel" among the properties sequestered from the Marcoses' ill-gotten wealth, estimating its minimum value to be about ₱16٫5 billion in March 2015.[229] The property had been surrendered to the PCGG in 1986, as part of the settlement deal of Marcos crony Jose Yao Campos, who was holding the property under various companies on Marcos Sr.'s behalf.[230] Ortigas & Company countered that Marcos Sr. had coerced them to sell the property to him in 1968.[228] Marcos Jr.'s motion claimed that his father had bought the property legally, but the Sandiganbayan dismissed his motion on October 18, 2008, saying it had already dismissed a similar motion filed years earlier by his mother Imelda.[231]

حكم ازدراء المحكمة في هاواي 2011

In 2011, the Hawaii District Court ruled Bongbong Marcos and his mother Imelda Marcos to be in contempt,[232] fining them US$353٫6 million (₱قالب:From USD in 2026) fine for not respecting an injunction from a 1992 judgement in a human rights victims case, which commanded them not to dissipate the assets of Ferdinand Marcos's estate.[233][234] The ruling was upheld by the US Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals on October 24, 2012, and is believed to be "the largest contempt award ever affirmed by an appellate court."[234] While the 1992 case was against Ferdinand Marcos, the 2011 judgment was against Imelda and Bongbong personally.[235] The judgement also effectively barred Imelda and Bongbong from entering any US territory.[232] However, on June 9, 2022, United States Deputy Secretary of State Wendy Sherman[236] clarified in a roundtable discussion with local reporters during a state visit, that as a head of state, Marcos enjoys diplomatic immunity in all circumstances, stating that he is welcome to visit the United States under his official role.[237]

آراؤه السياسية

Marcos has described his political views as "conservative" and "Machiavellian".[238] Before taking office, Marcos has been described in media reports as a populist.[239][240] On social issues, he is in favor of legalizing abortion for rape and incest victims[241][242] as well as divorce and same-sex unions.[243][244] Marcos is also opposed to reinstating the death penalty for convicted heinous criminals[245] and lowering the minimum age of criminal responsibility to 12.[246]

خلاف ماركوس-دوترتي

Amid the feud of the Marcos and Duterte clans in late April 2023, House Speaker and Marcos' cousin Martin Romualdez said the House of Representatives will probe into an agreement former president Rodrigo Duterte made during his presidency with Chinese president Xi Jinping. Under the agreement, Duterte agreed to maintain the "status quo" in the South China Sea to avoid escalating a war. Political analyst Ronald Llamas said the probe was engineered by Marcos as a "political payback" to Duterte's verbal attacks and to reduce Duterte's political influence ahead of the 2025 midterm elections.[247]

In 2024, Duterte criticized the Marcos administration's curtailment of the freedom of speech in violation of the 1987 Bill of Rights. Duterte's nationwide "Hakbang ng Maisug (brave) prayer-rallies, which Duterte said the Marcos administration deliberately aimed to thwart, suffered setbacks and cancellations.[248][249] Duterte, however, said he prayed for Marcos to survive until the end of his term since Duterte does not want himself or his daughter Sara to become president.[250]

الصورة العامة

الإنكار التاريخي

As with other Marcos family members who have stayed in the public eye since their return to the Philippines,[251][252][253] Marcos has received significant criticism for instances of historical denialism, and his trivialization of the human rights violations and economic plunder that took place during the Marcos administration, and of the role he played in the administration.[254][255][256] Specific criticisms have been leveled at Marcos for being unapologetic for human rights violations[254] and ill-gotten wealth[255] during his father's administration.[257][258][259][256] Of the human rights victims, Marcos Jr. said of them in 1999: "They don't want an apology, they want money."[260] He then proceeded to state that his family would apologize only if they had done something wrong.

When victims of human rights abuses during his father's administration commemorated the 40th year of the proclamation of martial law in 2012, Marcos Jr. dismissed their calls for an apology for the atrocities as "self-serving statements by politicians, self-aggrandizement narratives, pompous declarations, and political posturing and propaganda."[261][262] In the Sydney Morning Herald later that year, Bongbong cited the various court decisions against the Marcos family as a reason not to apologize for Martial Law abuses, saying "we have a judgment against us in the billions. What more would people want?"[1]

During his 2016 vice presidential campaign, Marcos responded to then-president Noynoy Aquino's criticism of the Marcos regime and call to oppose his election run. He dismissed the events, saying Filipinos should "leave history to the professors."[263][264][265] This prompted over 500 faculty, staff and history professors from the Ateneo de Manila University to immediately issue a statement condemning his dismissive retort as part of "an ongoing willful distortion of our history," and a "shameless refusal to acknowledge the crimes of the Martial Law regime."[266][267][268][269][270] More than 1,400 Catholic schools, through the Catholic Educational Association of the Philippines (CEAP), later joined the call of the Ateneo faculty "against the attempt of [Marcos] to canonize the harrowing horrors of martial rule."[271][272] This was also followed by the University of the Philippines Diliman's Department of History, which released a statement of its own, decrying what they called a "dangerous" effort for Marcos to create "myth and deception."[273][274][275]

On September 20, 2018, Marcos Jr. released a YouTube video showing a tête-à-tête between him and former senate president Juan Ponce Enrile, who had been his father's defense minister before playing a key role in his ouster during the 1986 EDSA revolution.[276] The video made a number of claims, which were quickly refuted and denounced by martial law victims, including former senate president Aquilino Pimentel Jr., former DSWD secretary Judy Taguiwalo, former Commission on Human Rights chair Etta Rosales, and writer Boni Ilagan, among others. Enrile later backpedaled from some of his claims, attributing them to "unlucid intervals."[277]

الحضور أونلاين

According to research by Vera Files, Marcos benefited the most from fake news from the Philippines in 2017, along with President Rodrigo Duterte.[278] Most viral news were driven by shares on networks of Facebook pages.[278] Also, most Philippine audience Facebook pages and groups spreading online disinformation bore "Duterte", "Marcos" or "News" in their names and are pro-Duterte.[279]

In July 2020, Brittany Kaiser alleged in an interview that Marcos had approached the controversial firm Cambridge Analytica in order to "rebrand" the Marcos family image on social media.[280] Marcos's spokesperson Vic Rodriguez denied these allegations and stated that Marcos is considering filing libel charges against Rappler, which published Kaiser's interview.[281]

أسطورة المحتال الحضري

Between the late 70s and early 80s, an urban legend became popular claiming that Marcos Jr. was stabbed and died during a scuffle while studying abroad. The Marcos family allegedly looked for Bongbong's look-alike to replace him. This was later debunked by Marcos in one of his vlogs. The origins of this urban legend remain unknown.[282]

أسطورة ذهب تالانو

In 1990, during a coverage of Imelda Marcos's trial in New York, Inquirer journalist Kristina Luz interviewed then-33-year-old exiled Bongbong Marcos and asked where the Marcos wealth came from. Marcos responded "only I know where the gold is and how to get it". This was corroborated in a 1992 report by the Associated Press that quoted Imelda Marcos saying that her husband's wealth came "from the Japanese and other gold he found after World War II, and not from the Philippine coffers." In 2007, Marcos informed the anti-graft court Sandiganbayan that his father's wealth came from trading "precious metals more specifically gold from the years 1946 to 1954" when he tried to win back the Ortigas Payanig property in Pasig from the national government.[283]

The myth surrounding the gold allegedly owned by the Marcos family has been the subject of various misinformation, as in 2011, a Facebook post claimed that a certain "Tallano clan" had paid Ferdinand Marcos Sr. in gold for his legal services. Several years later, supporters of the Marcos family in a Facebook page called "Marcos Cyber Warriors" also claimed that Marcos Sr.'s wealth came from his former law client, the "Maharlikan Tallano family".[284]

This has resulted in a long-running belief that should Bongbong Marcos win as president, he will give Filipinos a share of this gold. However during his Philippine presidential election campaign in the 2022 elections, when asked over One News to verify the mythical "Tallano gold" or the long-believed tale that they got a share of the Japanese Yamashita gold, Marcos denied knowledge of it, even joking that "people should let him know if they see any of that gold". The urban myth had allegedly been suggested or carried by various social media pages being run by Marcos supporters in order to engage more people to support his presidential bid.[284]

حياته الشخصية

Marcos is married to lawyer Louise "Liza" Cacho Araneta, a member of the prominent Araneta family. Marcos and Araneta were married in Fiesole, Italy, on April 17, 1993. They have three sons: Ferdinand Alexander III "Sandro" (born 1994), Joseph Simon (born 1995) and William Vincent "Vinny" (born 1997).[285][286][287] Although he is Ilocano by ethnic ancestry, he was brought up in a Manileño household and does not speak the Ilocano language.[288][289] The Marcos family maintains a residence in Forbes Park, Makati.[290]

Aside from his common nickname "Bongbong", Marcos is known by his peers as "Bonggets".[49] Marcos is an avid listener of rock and roll, rhythm and blues, and jazz music. He once held a record collection in Malacañang Palace that he described as "the best record collection in the Philippines" but left it when his family was exiled from the country in 1986. He is a fan of the Beatles, citing Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band as his favorite album of theirs, and often collects the band's memorabilia. Marcos can also play the saxophone.[291]

Marcos exercises regularly and claims to abstain from consuming confections and soft drinks.[49] Marcos is also an avid reader, a cinephile, and a gun enthusiast, where he holds a competition under his name.[49][55][292] He follows Formula One racing as a supporter of Scuderia Ferrari; during his presidency, he attended the 2022 and 2023 Singapore Grand Prix with Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong and other foreign dignitaries.[293]

On March 31, 2020, Marcos's spokesperson confirmed that Marcos had tested positive for COVID-19.[294] Prior to getting tested, Marcos was reportedly experiencing chest pains after coming home from a trip to Spain. He has since recovered from the disease after testing negative on a RT-PCR test on May 5, 2020, a month after testing positive for COVID-19.[295] On July 8, 2022, Marcos's press secretary confirmed that Marcos had tested positive again for COVID-19 after experiencing slight fever.[296]

مزاعم تعاطيه الكوكاكيين

On November 18, 2021, President Rodrigo Duterte claimed in a televised speech that a certain candidate for the 2022 Philippine presidential election is allegedly using cocaine, hinting at the candidate using male pronouns on several instances. Furthermore, Duterte alleged that the candidate eluded law enforcement authorities by doing drugs on a private yacht and a plane.[297] Although he did not name the candidate, it was alluded that Duterte was referring to Marcos after he continued on his speech that the male candidate is a "weak leader" and has been "capitalizing on his father's accomplishments".[298] Prior to that, Duterte previously named Marcos a "weak leader who had done nothing" and a "spoiled child for being an only son".[299]

Days after Duterte's allegation, Marcos took a cocaine drug test through a urine sample at St. Luke's Medical Center – Global City and submitted the negative result to law enforcement authorities with a follow-up online memo by the medical institution confirming the legitimacy of the test.[300]

Marcos responded that he did not feel that he was the one alluded to by President Duterte. According to health care provider American Addiction Centers, after the last use, cocaine or its metabolites can show up on a blood or saliva test for up to two days, a urine test for up to three days, and a hair test for months to years.[301] In an interview with CNN Philippines in April 2022, Marcos responded to Duterte's remarks on him being a "spoiled" and "weak leader", saying that the president was "playing politics" and was "always making sure everybody's thinking hard about what they're doing".[302]

In an interview with ANC in May 2022, former senator Nikki Coseteng, who claimed to personally know Marcos, alleged that Marcos was a "lazy individual" who frequented discos and got high on illegal substances along with his socialite friends during his youth.[303] Marcos has neither denied nor confirmed Coseteng's allegations.[304]

In late January 2024, Marcos's alleged cocaine use was brought anew by Duterte, during a prayer rally against Charter change in Davao City.[305] Duterte alleged that Marcos had once been included in the Philippine Drug Enforcement Agency's (PDEA) drug watchlist (which the agency denied) and had been spotted using cocaine with his cohorts at a giant banana firm's plantation in Davao del Norte when Duterte was Mayor. Duterte said that these companions of Marcos were already working for his administration, and cited this as the reason why he did not vote for him in the 2022 general election. When asked by Marcos to prove the allegations, Duterte retorted that it is incumbent upon him to prove the allegations by taking a drug test, since he is the one holding public office.[305] Marcos maintained he had never used illegal narcotics, let alone cocaine, and blamed Duterte's use of fentanyl as a response. In Duterte's defense, he had used fentanyl because it was prescribed to him by a "Dr. Javier", his alleged physician at St. Luke's Medical Center, to alleviate pain from injuries sustained in a motorbike accident a few years ago.[305]

تسريبات PDEA

In April 2023, leaked documents from the Philippine Drug Enforcement Agency (PDEA) circulated online, linking Marcos and actress Maricel Soriano to illegal drugs. The Senate Committee on Public Order and Dangerous Drugs, headed by Senator Ronald dela Rosa, later conducted a hearing on the matter and invited vlogger Maharlika to explain her involvement in the online circulation of the documents. Former PDEA investigation agent Jonathan Morales declared that the documents were authentic; PDEA Director General Moro Virgilio Lazo, on the other hand, claimed the documents were fake.[306]

On May 20, 2024, the Philippine Senate Committee on Public Order and Dangerous Drugs panel cited PDEA agent Jonathan Morales in contempt for ‘"continuously lying". Upon Jinggoy Estrada's motion and seconded by Ronald dela Rosa, Morales was ordered detained for flipped-flopped replies on PDS, inter alia. Earlier, a former National Police Commission officer, Eric "Pikoy" Santiago was also held in contempt of the Senate for being a "liar".[307][308] On May 23, 2024, Morales and Santiago were released from custody according to Senate Sergeant-at-Arms Roberto Ancan.[309]

المصادر

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح "A dynasty on steroids". The Sydney Morning Herald (in الإنجليزية). November 24, 2012. Archived from the original on May 6, 2022. Retrieved February 5, 2022.

- ^ "Senator Ferdinand "Bongbong" R. Marcos Jr". Senate of the Philippines. Archived from the original on November 29, 2010. Retrieved October 15, 2015.

- ^ Jones, Daniel (2011), Marcos (18 ed.), Cambridge University Press, p. 305, ISBN 978-0-521-15255-6

- ^ The New Webster's Dictionary of the English Language. Lexicon Publications, Inc. 1994. p. 609. ISBN 0-7172-4690-6.

- ^ أ ب ت "The son of late dictator Marcos has won the Philippines' presidential election". Associated Press. Manila. NPR. May 10, 2022. Archived from the original on May 12, 2022. Retrieved May 12, 2022.

- ^ Cabato, Regine; Westfall, Sammy (May 10, 2022). "Marcos family once ousted by uprising wins Philippines vote in landslide". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on May 10, 2022. Retrieved May 12, 2022.

- ^ Lalu, Gabriel Pabico (June 30, 2022). "It's official: Bongbong Marcos sworn in as PH's 17th President". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Archived from the original on June 30, 2022. Retrieved June 30, 2022.

- ^ "Dictator's son Ferdinand Marcos Jr. takes oath as Philippine president". NPR (in الإنجليزية). Associated Press. June 30, 2022. Archived from the original on June 30, 2022. Retrieved July 1, 2022.

- ^ Ellison, Katherine W. (2005). Imelda, steel butterfly of the Philippines. Lincoln, Nebraska.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ أ ب ت Holley, David (February 28, 1986). "Speculation Grows: Marcos May Stay at Luxurious Hawaii Estate". Los Angeles Times. ISSN 0458-3035. Archived from the original on September 21, 2015. Retrieved August 16, 2018.

- ^ أ ب Mydans, Seth (November 4, 1991). "Imelda Marcos Returns to Philippines". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 12, 2009. Retrieved August 16, 2018.

- ^ Robles, Alan (May 2, 2022). "Philippine election: Who is Bongbong Marcos, what's his platform and China views, and why can't he visit the US?". South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on May 12, 2022. Retrieved May 2, 2022.

- ^ "List of Committees". Senate of the Philippines. February 5, 2014. Archived from the original on February 7, 2007. Retrieved March 14, 2014.

- ^ أ ب "Bongbong Marcos running for vice president in 2016". CNN. October 5, 2015. Archived from the original on October 8, 2015. Retrieved October 5, 2015.

- ^ أ ب "Marcos heir loses bid to overturn Philippine VP election loss". The South China Morning Post (in الإنجليزية). Agence France-Presse. February 16, 2021. Archived from the original on February 16, 2021. Retrieved February 16, 2021.

- ^ أ ب "Supreme Court unanimously junks Marcos' VP poll protest vs Robredo". CNN Philippines (in الإنجليزية). February 16, 2021. Archived from the original on February 16, 2021. Retrieved February 16, 2021.

- ^ "Dictator's son Bongbong Marcos files candidacy for president". Rappler (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). October 6, 2021. Archived from the original on October 6, 2021. Retrieved January 13, 2022.

- ^ أ ب Verizon, Cliff (May 25, 2022). "Marcos officially declared Philippines' next president". Nikkei Asia. Archived from the original on June 20, 2022. Retrieved May 26, 2022.

- ^ أ ب Morales, Neil Jerome (May 25, 2022). "hilippines Congress proclaims Marcos as next president". Reuters. Archived from the original on June 20, 2022. Retrieved May 26, 2022.

- ^ "Martial Law Museum". Martial Law Museum (in الإنجليزية). Archived from the original on May 23, 2022. Retrieved June 5, 2022.

- ^ Kamm, Henry (February 6, 1981). "PHILIPPINE OPPOSITION TO BOYCOTT PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION". The New York Times (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on May 24, 2015. Retrieved June 5, 2022.

- ^ Kamm, Henry (June 17, 1981). "MARCOS IS VICTOR BY A HUGE MAJORITY". The New York Times (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on June 5, 2022. Retrieved June 5, 2022.

- ^ أ ب "Filipinos fall for fake history". The Standard (Hong Kong). Agence France-Presse. March 30, 2022. Archived from the original on May 15, 2022. Retrieved April 11, 2022.

- ^ Cabato, Regine; Mahtani, Shibani (April 12, 2022). "How the Philippines' brutal history is being whitewashed for voters". The Washington Post (in الإنجليزية). Archived from the original on April 12, 2022. Retrieved April 23, 2022.

- ^ Wee, Sui-Lee (May 1, 2022). "'We Want Change': In the Philippines, Young People Aim to Upend an Election". The New York Times (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on May 2, 2022. Retrieved May 2, 2022.

- ^ "Protestas en Filipinas en rechazo a la victoria no oficial de Ferdinand Marcos Jr". France 24. May 11, 2022. Archived from the original on May 17, 2022. Retrieved May 17, 2022.

- ^ "Filipino Community Protests Philippine Presidential Election Results". South Seattle Emerald (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). May 13, 2022. Archived from the original on May 18, 2022. Retrieved May 17, 2022.

- ^ Mangaluz, Jean (April 18, 2024). "Bongbong Marcos is in Time's 100 Most Influential People for 2024". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Archived from the original on April 18, 2024. Retrieved April 18, 2024.

- ^ "Ferdinand "Bongbong" Marcos: The 100 Most Influential People of 2024". TIME (in الإنجليزية). April 17, 2024. Retrieved April 18, 2024.

- ^ أ ب Seagrave, Sterling (1988). The Marcos dynasty. New York ...[etc.]: Harper & Row. ISBN 0060161477. OCLC 1039684909.

- ^ Wilson Lee Flores (May 8, 2006). "Who will be the next taipans?". The Philippine Star. Archived from the original on March 26, 2022. Retrieved September 2, 2018.

- ^ أ ب "Resume of Senator Ferdinand "Bongbong" R. Marcos, Jr". Senate of the Philippines. Archived from the original on October 25, 2020. Retrieved March 26, 2022.

- ^ "Vote PH 2016; Bongbong Marcos". Philippine Daily Inquirer (in الإنجليزية). Archived from the original on February 16, 2016. Retrieved March 26, 2022.

- ^ أ ب ت Legaspi, Amita O. (September 21, 2014). "Where was Bongbong Marcos when martial law was declared in 1972?". GMA News Online. Archived from the original on July 14, 2018. Retrieved September 2, 2018.

- ^ Galvez, Daphne (March 13, 2023). "Marcos admits not finishing 'special diploma' course in UA&P". Philippine Daily Inquirer (in الإنجليزية).

- ^ Flores, Helen (March 14, 2023). "Marcos admits not finishing UA&P certificate program". The Philippine Star.

- ^ "Marcos: Special diploma from Oxford is same as bachelor's degree". January 21, 2016. Archived from the original on January 31, 2022. Retrieved August 2, 2017.

- ^ أ ب "Oxford: Bongbong Marcos' special diploma 'not a full graduate diploma'". Rappler (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). October 26, 2021. Archived from the original on January 8, 2022. Retrieved January 8, 2022.

- ^ "Resume of Senator Ferdinand "Bongbong" R. Marcos Jr". Senate of the Philippines. Archived from the original on November 18, 2015. Retrieved November 12, 2015.

- ^ أ ب "Oxford group: Marcos received special diploma, no college degree". cnn (in الإنجليزية). Archived from the original on January 8, 2022. Retrieved January 8, 2022.

- ^ "Marcos Pa Rin! The Legacy and the Curse of the Marcos Regime". Kasarinlan: Philippine Journal of Third World Studies. 28: 456. 2012. Archived from the original on November 6, 2021. Retrieved November 6, 2021.

- ^ Collas-Monsod, Solita (November 6, 2021). "Yes, I tutored Bongbong in Economics". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Archived from the original on November 18, 2021. Retrieved November 6, 2021.

- ^ Ariate, Joel F.; Reyes, Miguel Paolo P.; Del Mundo, Larah Vinda (November 1, 2021). "The documents on Bongbong Marcos' university education (Part 1- Oxford University)". Vera Files. Archived from the original on February 3, 2022. Retrieved November 6, 2021.

- ^ Gonzales, Catherine (February 5, 2022). "Bongbong Marcos maintains he's a graduate of Oxford". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Archived from the original on May 3, 2022. Retrieved March 24, 2022.

- ^ "Bongbong Marcos: Oxford, Wharton educational record 'accurate'". Rappler. Archived from the original on November 18, 2015. Retrieved November 12, 2015.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح Manapat, Ricardo (2020). Some are smarter than others : the history of Marcos' crony capitalism (Annotated ed.). Quezon City, Philippines: Ateneo University Press. ISBN 978-971-550-926-8. OCLC 1226800054. Archived from the original on July 12, 2022. Retrieved February 4, 2022.

- ^ أ ب "Bongbong Marcos: Iginuhit ng showbiz". The Philippine Star. Archived from the original on April 30, 2020. Retrieved April 27, 2018.

- ^ Gomez, Buddy (August 26, 2015). "A romance that began with deception". ABS-CBN News (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). Archived from the original on April 28, 2018. Retrieved April 27, 2018.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Geronimo, Gee Y. (October 12, 2015). "9 things to know about Bongbong Marcos". Rappler (in الإنجليزية). Archived from the original on January 20, 2018. Retrieved April 27, 2018.

- ^ Garcia, Myles (March 31, 2016). Thirty Years Later . . . Catching Up with the Marcos-Era Crimes (in الإنجليزية). eBookIt.com. ISBN 9781456626501. Archived from the original on March 22, 2023. Retrieved October 27, 2020.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج Reyes, Oliver X.A. (May 24, 2017). "The Beatles' Worst Nightmare in Manila". Esquire Magazine Philippines. Archived from the original on April 28, 2018. Retrieved April 27, 2018.

- ^ Seagrave, Sterling (1988). The Marcos dynasty. New York ...[etc.]: Harper & Row. ISBN 0060161477. OCLC 1039684909.

- ^ أ ب ت Salva, Romio Armisol (October 18, 2021). "Bongbong Marcos Claimed He Was 'Friends' with The Beatles. Was He Really?". Esquire. Archived from the original on October 18, 2021. Retrieved October 18, 2021.

- ^ أ ب "Ex-Beatle Recalls Marcos As 'Twit' Who Took Back Money for Concert". AP News. Associated Press. April 12, 1986. Archived from the original on May 18, 2022. Retrieved May 18, 2022.

- ^ أ ب Amio, Armin; Distor, Tessa (September 14, 2015). "25 things you probably didn't know about Bongbong Marcos". Manila Bulletin. Archived from the original on July 21, 2022. Retrieved July 21, 2022 – via PressReader.

- ^ "Is Bongbong Marcos Accountable?". The Martial Law Chronicles Project (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). March 7, 2018. Archived from the original on August 8, 2020. Retrieved October 12, 2021.

- ^ Sauler, Erika (February 5, 2016). "'Carmma' to hound Bongbong campaign". Archived from the original on August 5, 2020. Retrieved April 27, 2018.

- ^ "Elections 2016". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Archived from the original on February 16, 2016. Retrieved April 27, 2018.

- ^ Angkatan Bersenjata Republik Indonesia (April 1983). "Marcos Lantik Puteranya Jadi Gubernur" [Marcos Installs His Son as Governor]. Mimbar Kekaryaan. No. 148. p. 70. Archived from the original on March 22, 2023. Retrieved April 14, 2022.

Presiden Filipina Ferdinand Marcos tgl 23 Maret melantik puteranya yang berusia 24 tahun Ferdinand R Marcos Jr sebagai Gubernur propinsi Ilocos Norie [sic] di Filipina bagian utara. Marcos muda itu menggantikan bibinya Ny. Elizabeth M. Rocka yang karena kesehatannya mengundurkan diri sebagai Gubernur. Marcos muda terpilih sebagai wakil gubernur dalam pemilihan umum 1980. Dalam pemilu itu pula bibinya memenangkan jabatan gubernur.

- ^ "The Profile Engine". The Profile Engine. Archived from the original on April 28, 2018. Retrieved November 12, 2015.

- ^ "Why is it difficult for Bongbong Marcos to apologize?". Rappler (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). April 14, 2016. Archived from the original on June 5, 2022. Retrieved June 13, 2022.

- ^ Salvador, Lenville (February 26, 2016). "Ilocos Martial Law victims say no to Bongbong Marcos". Northern Dispatch Weekly (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). Archived from the original on June 28, 2017. Retrieved April 27, 2018.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ Punzalan, Jamaine (November 25, 2016). "No 'Martial Law' babies: Imee, Bongbong held key posts under dad's rule". ABS-CBN News. Archived from the original on January 18, 2022. Retrieved April 27, 2018.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح Scott, Ann (March 17, 1986). "U.S. auditors to examine documents related to Philippines' alleged diverted funds" (in الإنجليزية). UPI. Archived from the original on December 14, 2017. Retrieved April 27, 2018.

- ^ أ ب ت Butterfield, Fox (March 30, 1986). "Marcos's Fortune: Inquiry in Manila Offers Picture of How it Was Acquired". The New York Times (in الإنجليزية). Archived from the original on May 29, 2018. Retrieved May 29, 2018.

- ^ Garcia, Myles (2016). Thirty Years Later... Catching Up with the Marcos-Era Crimes. eBookIt.com. ISBN 9781456626501.

- ^ قالب:Cite PH act

- ^ Tiongson-Mayrina, Karen and GMA News Research (September 21, 2017). "The Supreme Court's rulings on the Marcoses' ill-gotten wealth". Archived from the original on September 11, 2021. Retrieved February 4, 2022.

- ^ Jovito, Salonga (2000). Presidential plunder: the quest for the Marcos ill-gotten wealth. [Quezon City]: U.P. Center for Leadership, Citizenship and Democracy. ISBN 9718567283. OCLC 44927743.

- ^ del Mundo, Fernando (February 25, 2013). "US set 5 conditions to save Marcos". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Archived from the original on February 20, 2018. Retrieved February 19, 2018.

- ^ Lustre, Philip Jr. (February 25, 2016). "Ferdinand Marcos: His last day at the Palace". CNN Philippines. Archived from the original on March 18, 2016.

- ^ أ ب Duet for EDSA: Chronology of a Revolution. Manila, Philippines: Foundation for Worldwide People Power. 1995. ISBN 9719167009. OCLC 45376088.

- ^ "The Marcos Party in Honolulu". The New York Times (in الإنجليزية). Associated Press. March 11, 1986. Archived from the original on May 24, 2015. Retrieved August 16, 2018.

- ^ Holley, David (February 27, 1986). "Marcos Party Reaches Hawaii in Somber Mood". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on October 22, 2015. Retrieved August 16, 2018.

- ^ "The End of an Era – Handholding Ferdinand Marcos in Exile". Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training. Archived from the original on November 17, 2015. Retrieved November 12, 2015.

- ^ أ ب "Marcos' son still eyes share of loot". South China Morning Post. September 24, 2011. Archived from the original on March 25, 2017.

- ^ Parry, John (March 26, 1986). "Swiss Freeze Marcos' Bank Accounts, Citing Withdrawal Attempt Monday". Washington Post (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). ISSN 0190-8286. Archived from the original on May 20, 2022. Retrieved February 3, 2022.

- ^ Richburg, Keith B.; Branigin, William (September 29, 1989). "Ferdinand Marcos Dies in Hawaii at 72". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on August 16, 2018. Retrieved August 16, 2018.

- ^ Aruiza, Arturo C. (1991). Ferdinand E. Marcos : Malacañang to Makiki. Quezon City, Philippines: ACA Enterprises. ISBN 9718820000. OCLC 27428517.

- ^ Dizon, David (January 21, 2016). "If Marcos wins, PH will be laughingstock of the world: Osmena". ABS-CBN News (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). Archived from the original on May 11, 2018. Retrieved May 11, 2018.