ألباما

ألباما | |

|---|---|

| ولاية الباما | |

| الكنية: ولاية Yellowhammer، قلب Dixie، وولاية القطن | |

| الشعار: | |

| النشيد: "Alabama" | |

خريطة الولايات المتحدة، موضح فيها ألباما | |

| البلد | الولايات المتحدة |

| قبل الولائية | Alabama Territory |

| انضمت للاتحاد | December 14, 1819 (22nd) |

| العاصمة | مونتگمري |

| أكبر مدينة | برمنگهام |

| أكبر منطقة عمرانية | برمنگهام الكبرى |

| الحكومة | |

| • الحاكم | Kay Ivey (R) |

| • نائب الحاكم | Will Ainsworth (R) |

| المجلس التشريعي | Alabama Legislature |

| • المجلس العلوي | Senate |

| • المجلس السفلى | House of Representatives |

| القضاء | Supreme Court of Alabama |

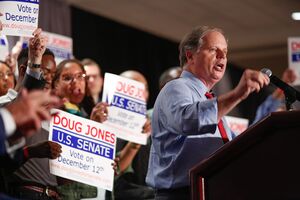

| سناتورات الولايات المتحدة | Richard Shelby (R) Tommy Tuberville (R) |

| وفد مجلس النواب | 6 Republicans 1 Democrat (القائمة) |

| المساحة | |

| • الإجمالي | 52٫419 ميل² (135٫765 كم²) |

| • البر | 50٫744 ميل² (131٫426 كم²) |

| • الماء | 1٫675 ميل² (4٫338 كم²) 3.2% |

| ترتيب المساحة | رقم 30 |

| الأبعاد | |

| • الطول | 330 mi (531 km) |

| • العرض | 190 mi (305 km) |

| المنسوب | 500 ft (150 m) |

| أعلى منسوب | 2٫413 ft (735٫5 m) |

| أوطى منسوب | 0 ft (0 m) |

| التعداد (2019) | |

| • الإجمالي | 4٬903٬185 |

| • الترتيب | 24th |

| • ترتيب الكثافة | 27th |

| • الدخل الأوسط للأسرة | $48٬123[4] |

| • ترتيب الدخل | 46th |

| صفة المواطن | Alabamian,[5] Alabaman[6] |

| اللغة | |

| • اللغة الرسمية | الإنگليزية |

| • اللغة المحكية | اعتبارا من 2010[تحديث][7]

|

| منطقة التوقيت | UTC−06:00 (Central) |

| • الصيف (التوقيت الصيفي) | UTC−05:00 (CDT) |

| اختصار البريد | AL |

| ISO 3166 code | US-AL |

| الاختصار التقليدي | Ala. |

| خط العرض | 30°11' N to 35° N |

| خط الطول | 84°53' W to 88°28' W |

| الموقع الإلكتروني | alabama |

| رموز ولاية Alabama | |

|---|---|

The علم Alabama | |

The ختم Alabama | |

| |

| الشارات الحية | |

| البرمائي | Red Hills salamander |

| الطائر | Yellowhammer, wild turkey |

| الفراشة | Eastern tiger swallowtail |

| السمكة | Largemouth bass, fighting tarpon Bluegill |

| الزهرة | Camellia, oak-leaf hydrangea |

| سلالة الخيول | Racking horse |

| الحشرة | Monarch butterfly |

| الثديي | American black bear |

| الزاحف | Alabama red-bellied turtle |

| الشجرة | Longleaf pine |

| الشارات الجامدة | |

| المشروب | Conecuh Ridge Whiskey |

| الألوان | Red, white |

| الرقصة | Square dance |

| الطعام | Pecan, blackberry, peach |

| الأحفورة | Basilosaurus |

| الحجر الكريم | Star blue quartz |

| المعدن | Hematite |

| الصخرة | Marble |

| الصدَفة | Johnstone's junonia |

| الشعار | Share The Wonder, Alabama the beautiful, Where America finds its voice, Sweet Home Alabama |

| التربة | Bama |

| State route marker | |

| |

| State quarter | |

Released in 2003 | |

| قوائم رموز الولايات الأمريكية | |

ألباما (إنگليزية: Alabama، /ˌæləˈbæmə/)، هي ولاية تقع في جنوب شرق الولايات المتحدة، تحدها تنسي من الشمال؛ جورجيا من الشرق؛ فلوريدا وخليج المكسيك من الجنوب]]؛ ومسيسيپي من الغرب. ألباما تعد الولاية 30 من حيث المساحة و24 من حيث عدد السكان من بين الولايات المتحدة. مع إجمالي 1500 ميل (2400 كيلو متر) من الممر المائي الداخلي ، حيث تملك ألباما الأطول بين الولايات .[8]

يُطلق على ولاية ألباما اسم ولاية الدرسة الصفراء ، على اسم طائر الولاية. تُعرف ولاية ألباما أيضاً باسم "قلب دكسي" و "ولايةالقطن". شجرة الولاية هي الصنوبر طويل الأوراق، وزهرة الولاية هي الكاميليا. عاصمة ألباما هي مونتگومري. وأكبر مدينة من حيث عدد السكان هي برمنگهام،[9] التي لطالما كانت أكثر المدن الصناعية؛ أكبر مدينة من حيث مساحة الأرض هي هنتسفيل. أقدم مدينة هي موبيل ، أسسها الفرنسيون المستعمرون عام 1702 كعاصمة لويزيانا الفرنسية .[10]برمنگهام الكبرى هي أكبر اقتصاد حضري في ولاية ألباما ، وأكثر مناطقها الحضرية اكتظاظاً بالسكان ، ومركزها الاقتصادي. [11]

تتنوع جغرافية الولاية، حيث يسود الشمال وادي تنسي والجنوب خليج موبيل، وهو ميناء مهم تاريخياً. سياسياً، كجزء من الجنوب العميق، أصبحت ألباما الآن ولاية محافظة في الغالب، وهي معروفة بـ الثقافة الجنوبية. اليوم، تعد كرة القدم الأمريكية، ولا سيما على المستوى الجامعي في مدارس مثل جامعة ألباما، جزءًا رئيسياً من ثقافة الولاية.

كانت ألباما الحالية ، التي كانت في الأصل موطناً للعديد من القبائل الأصلية ، إقليماً إسبانياً بدءًا من القرن السادس عشر حتى استحوذ عليها الفرنسيون في أوائل القرن الثامن عشر ، حيث أسسوا موبايل في عام 1702. وفاز البريطانيون بالمنطقة في عام 1763 حتى خسروها في حرب الثورة الأمريكية. احتفظت إسبانيا بموبيل كجزء من فلوريدا الغربية الإسبانية حتى عام 1813 ؛ تنازلت إسبانيا عن ولاية فلوريدا الغربية للولايات المتحدة في عام 1819. وفي ديسمبر 1819 ، تم الاعتراف بألباما كدولة. خلال فترة ما قبل الحرب ، كانت ألباما منتجاً رئيسياً للقطن واستخدمت على نطاق واسع العبيد الأمريكيين من أصل أفريقي في مزارعها. في عام 1861 ، انفصلت الدولة عن الولايات المتحدة لتصبح جزءًا من الولايات الكونفدرالية الأمريكية ، وكانت عاصمتها مونتگومري الأولى ، وعادت إلى الاتحاد في عام 1868.

منذ الحرب الأهلية الأمريكية حتى الحرب العالمية الثانية ، عانت ألباما ، مثل العديد من الولايات في جنوب الولايات المتحدة ، من صعوبات اقتصادية ، ويرجع ذلك جزئياً إلى اعتمادها المستمر على الزراعة. على غرار دول العبيد السابقة الأخرى ، استخدم المشرعون في ألباما قوانين جيم كرو لحرمان الأمريكيين الأفارقة من حق التصويت والتمييز ضدهم من نهاية فترة إعادة البناء حتى السبعينيات على الأقل. على الرغم من نمو الصناعات الرئيسية والمراكز الحضرية ، سيطرت المصالح الريفية للبيض على المجلس التشريعي للولاية من عام 1901 إلى الستينيات. خلال هذا الوقت ، كانت المصالح الحضرية والأميركيون الأفارقة ممثلة تمثيلا ناقصا بشكل ملحوظ. الأحداث البارزة مثل مسيرة سلمى إلى مونتگومري جعلت الدولة نقطة محورية رئيسية لـ حركة الحقوق المدنية في الخمسينيات والستينيات. بعد الحرب العالمية الثانية ، نمت ولاية ألباما حيث تغير اقتصاد الولاية من اقتصاد قائم على الزراعة إلى اقتصاد له اهتمامات متنوعة. يعتمد اقتصاد الولاية في القرن الحادي والعشرين على الإدارة والسيارات والتمويل والتصنيع والفضاء واستخراج المعادن والرعاية الصحية والتعليم والبيع بالتجزئة والتكنولوجيا. [12]

التسمية

تم اشتقاق التسمية الأوروبية الأمريكية ل نهر ألباما والولاية من شعب ألباما، وهي قبيلة تتحدث لغة موسكوجين يعيش أفرادها أسفل مقرن نهري كوزا و تالابوزا على الروافد العليا للنهر. [13] في لغة ألباما ، يطلق على شخص من سلالة ألباما هي ألبامو (أو بشكل مختلف Albaama أو Albàamo في لهجات مختلفة ؛ صيغة الجمع هي Albaamah . [14] اقتراح أن "ألباما" مستعار من لغة الشوكتو غير مرجح .[15][16] يختلف تهجئة الكلمة بشكل كبير بين المصادر التاريخية .[16] الاستخدام الأول في ثلاثة روايات عن رحلة هيرناندو دي سوتو عام 1540, واستخدم غارسيلاسو دي لا فيغا اليبامو ، في حين كتب فارس إلفاس ورودريغو رانجيل اليبامو وليمامو ، على التوالي ، في النسخ الحرفي. [16] في وقت مبكر من عام 1702 ، أطلق الفرنسيون على القبيلة اسم Alibamon ، مع خرائط فرنسية تحدد النهر باسم ريفيير دياليبامونز .[13] تضمنت التهجئات الأخرى للاسم Alibamu, Alabamo, Albama, Alebamon, Alibama, Alibamou, Alabamu, Allibamou.[16][17][18][19]

تختلف المصادر حول معنى الكلمة. يقترح بعض العلماء أن الكلمة تأتي من الشوكتو ألبا (بمعنى "نباتات" أو "أعشاب") و آمو (تعني "تقطع" أو "تقليم" أو "تجمع") .[16][20][21] قد يكون المعنى هو "منظف الغابة"[20] or "herb gatherers",[21][22] في إشارة إلى تنظيف الأرض للزراعة [17] أو جمع النباتات الطبية.[22] الولاية لديها العديد من أسماء الأماكن من أصل أمريكي أصلي .[23][24] ومع ذلك ، لا توجد كلمات مماثلة في نفس الوقت في لغة ألباما.

اقترح مقال عام 1842 في صحيفة جمهوري جاكسونڤل أنه يعني "هنا نرتاح".[16] انتشر هذا المفهوم في خمسينيات القرن التاسع عشر من خلال كتابات االكسندر بوفورت ميك .[16] لكن لم يجد الخبراء في لغات المسكوكية أي دليل يدعم مثل هذه الترجمة. [13][16]

التاريخ

ما قبل الاستيطان الأوروپي

عاشت الشعوب الأصلية من ثقافات مختلفة في المنطقة لآلاف السنين قبل ظهور الاستعمار الأوروبي. بدأت التجارة مع القبائل الشمالية الشرقية عن طريق نهر أوهايو خلال فترة تلال الدفن (1000 قبل الميلاد – 700 م) واستمرت حتى الاتصال الأوروبي. [25]

غطت الثقافة المسيسپية الزراعية معظم الولاية من 1000 إلى 1600 م ، مع أحد مراكزها الرئيسية التي بنيت في ما يعرف الآن بـ موقع موندفيل الأثري في موندفيل ، ألباما .[26][27] هذا هو ثاني أكبر مجمع من العصر المسيسيبي الأوسط الكلاسيكي، بعد كاهوكيا في الوقت الحاضر في إلينوي ، والتي كانت مركزاً للثقافة. كان تحليل القطع الأثرية من الحفريات الأثرية في موندفيل أساس صياغة العلماء لخصائص المجمع الاحتفالي الجنوبي الشرقي (إس.إي.سي.سي) .[28] خلافاً للاعتقاد الشائع ، يبدو أن (إس.إي.سي.سي) ليس لها روابط مباشرة بثقافة وسط أمريكا، ولكنها تطورت بشكل مستقل. يمثل المجمع الاحتفالي مكوناً رئيسياً لديانة شعوب المسيسيبي؛ إنها إحدى الوسائل الأساسية التي يُفهم بها دينهم[29]

من بين القبائل التاريخية للشعب الأمريكي الأصلي الذي كان يعيش في ولاية ألباما الحالية في وقت الاتصال الأوروبي ، كان شيروكي ، وهم شعب اللغات الأيروكوية ؛ و شعب الموسكوجي - يتحدثون لغة ألباما أليبامو و تشيكاساو و تشوكتو و كريك و كواساتي. [30] . في حين أن قبائل موسكوجي جزء من نفس العائلة اللغوية الكبيرة، فقد طورت ثقافات ولغات متميزة.

الاستيطان الأوروپي

كان الإسبان أول أوروبيين وصلوا إلى ألباما أثناء استكشافهم لأمريكا الشمالية في القرن السادس عشر. مرت الحملة الاستكشافية لـإرناندو دي سوتو عبر مابيلا وأجزاء أخرى من الولاية في عام 1540. بعد أكثر من 160 عاماً ، أسس الفرنسيون أول مستوطنة أوروبية في المنطقة في أولد موبيل في عام 1702 .[31] تم نقل المدينة إلى موقع موبيل الحالي في عام 1711. وقد طالب الفرنسيون بهذه المنطقة من 1702 إلى 1763 كجزء من لويزيانا الفرنسية .[32]

بعد خسارة الفرنسيين أمام البريطانيين في حرب السنوات السبع ، أصبحت جزءًا من فلوريدا الغربية البريطانية من عام 1763 إلى عام 1783. بعد انتصار الولايات المتحدة في الحرب الثورية الأمريكية ، تم تقسيم الأراضي بين الولايات المتحدة وإسبانيا. احتفظت الأخيرة بالسيطرة على هذه المنطقة الغربية من عام 1783 حتى استسلام الحامية الإسبانية في موبيل للقوات الأمريكية في 13 أبريل 1813. [32][33]

كان توماس باسيت ، الموالي للنظام الملكي البريطاني خلال الحقبة الثورية، من أوائل المستوطنين البيض في الولاية خارج موبيل. استقر في منطقة تومبيگبي خلال أوائل سبعينيات القرن الثامن عشر. [34] كانت حدود المقاطعة مقتصرة تقريباً على المنطقة الواقعة على بعد أميال قليلة من نهر تومبيگبي وتضمنت أجزاء مما يعرف اليوم مقاطعة كلارك الجنوبية، وأقصى شمال مقاطعة موبيل ، ومعظم مقاطعة واشنطن .[35][36]

ما هي الآن مقاطعات بالدوين و موبيل أصبحت جزءًا من فلوريدا الغربية الإسبانية في عام 1783 ، وهي جزء من جمهورية غرب فلوريدا في عام 1810 ، وأضيفت أخيرًا إلى إقليم المسيسيپي في عام 1812. معظم ما يُعرف الآن بالثلثين الشماليين من ألباما كان يُعرف باسم أراضي يازو بدءًا من فترة الاستعمار البريطاني. تمت المطالبة بها من قبل ولاية جورجيا من عام 1767 فصاعداً. بعد الحرب الثورية ، بقيت جزءًا من جورجيا ، على الرغم من النزاع الشديد عليها. [37][38]

باستثناء المنطقة المحيطة بـ موبيل وأراضي يازو، أصبح ما يُعرف الآن بالثلث الأدنى من ولاية ألباما جزءًا من إقليم المسيسيبي عندما تم تنظيمه في عام 1798. وأضيفت أراضي يازو إلى الإقليم في عام 1804 ، بعد فضيحة أرض يازو. [38][39] احتفظت إسبانيا بالمطالبة بأراضيها الإسبانية الغربية فيما سيصبح المقاطعات الساحلية حتى تنازلت عنها بموجب معاهدة آدمز ـ اونيس رسميًا للولايات المتحدة في عام 1819. [33]

أوائل القرن 19

قبل الاعتراف بولاية مسيسپي في 10 ديسمبر 1817 ، تم فصل النصف الشرقي الأقل استيطاناً من الإقليم وتسمى إقليم ألباما. أنشأ كونگرس الولايات المتحدة إقليم ألباما في 3 مارس 1817. كانت سانت ستيفنس ، التي تم التخلي عنها الآن ، بمثابة العاصمة الإقليمية من 1817 إلى 1819.[40]

تم قبول ولاية ألباما باعتبارها الولاية الثانية والعشرين في 14 ديسمبر 1819، مع اختيار الكونگرس هانتسفيل كموقع للمؤتمر الدستوري الأول. من 5 تموز (يوليو) إلى 2 آب (أغسطس) 1819 ، اجتمع المندوبون لإعداد دستور الولاية الجديد. خدم هنتسفيل كعاصمة مؤقتة من 1819 إلى 1820، عندما انتقل مقر الحكومة إلى كاهابا في مقاطعة دالاس.[41]

كانت كاهابا، التي أصبحت الآن مدينة أشباح ، أول عاصمة دائمة للولاية من 1820 إلى 1825.[42] كان التدفق خلال حمى ألباما على الأرض كبيراً عندما تم قبول الدولة في الاتحاد ، مع تدفق المستوطنين والمضاربين على الأراضي إلى الولاية للاستفادة من الأراضي الخصبة الصالحة لزراعة القطن.[43][44] جزء من الحدود في عشرينيات وثلاثينيات القرن التاسع عشر ، نص دستورها على حق الاقتراع العام للرجال البيض.[45]

جلب المزارعون الجنوبيون والتجار من الجنوب الأعلى العبيد معهم مع توسع المزارع في ألباما الخاصة بالقطن. تم بناء اقتصاد الحزام الأسود المركزي والذي (سمي كذلك بسبب التربة المظلمة والمنتجة) حول مزارع القطن الكبيرة التي نمّت ثروة مالكيها بشكل أساسي من العمل بالسخرة.[45] اجتذبت المنطقة أيضًا العديد من الفقراء والمحرومين الذين أصبحوا مزارعي الكفاف. كان عدد سكان ألباما أقل من 10000 شخص في عام 1810 ، لكنه زاد إلى أكثر من 300000 شخص بحلول عام 1830.[43] معظم القبائل الأمريكية الأصلية تمت إزالتها تماماً من الولاية في غضون بضع سنوات من إقرار الكونگرس قانون إزالة الهنود في عام 1830.[46]

من 1826 إلى 1846 ، كانت تسكالوسا عاصمة ألباما. في 30 يناير 1846 ، أعلن المجلس التشريعي في ولاية ألباما أنه صوّت لنقل العاصمة من توسكالوسا إلى مونتگمري. انعقدت الجلسة التشريعية الأولى في العاصمة الجديدة في ديسمبر 1847.[47] تم تشييد مبنى الكابيتول الجديد تحت إشراف ستيفن ديكاتور باتون من فيلادلفيا. احترق الهيكل الأول في عام 1849 ، ولكن أعيد بناؤه في نفس الموقع عام 1851. ولا يزال مبنى الكابيتول الثاني هذا في مونتگومري حتى يومنا هذا. تم تصميمه من قبل باراشياس هولت من إيكستر، مين.[48][49]

الحرب الأهلية وإعادة الإعمار

بحلول عام 1860 ، ارتفع عدد السكان إلى 964201 شخصاً ، كان نصفهم تقريباً ، 435.080 ، من الأمريكيين الأفارقة المستعبدين ، و 2690 من الأشخاص الملونين الأحرار.[50] في 11 يناير 1861 ، أعلنت ولاية ألباما انفصالها عن الاتحاد. بعد أن ظلت جمهورية مستقلة لبضعة أيام، انضمت إلى الولايات الكونفدرالية الأمريكية. كانت عاصمة الكونفدرالية في البداية في مونتگومري. كانت ولاية ألباما متورطة في الحرب الأهلية الأمريكية بشدة. على الرغم من قلة المعارك نسبياً في الولاية ، ساهمت ألاباما بحوالي 120.000 جندي في المجهود الحربي.

انضمت سرية من جنود سلاح الفرسان من هنتسفيل، ألباما، إلى كتيبة ناثان بيدفورد فورست في هوبكينزفيل، كنتاكي. ارتدت السرية زيا جديدا مع تقليم أصفر على الأكمام والياقة ونهاية المعطف. أدى ذلك إلى ترحيب ولاية "الدرسة الصفراء" بهم ، وتم تطبيق الاسم لاحقًا على جميع قوات ألباما في الجيش الكونفدرالي.[51]

تم تحرير عبيد ألباما بموجب التعديل الثالث عشر في عام 1865.[52] كانت ألباما تحت الحكم العسكري منذ نهاية الحرب في مايو 1865 حتى إعادتها رسمياً إلى الاتحاد في عام 1868. من عام 1867 إلى 1874 ، ومع منع معظم المواطنين البيض مؤقتاً من التصويت ومنح المحررين حق التصويت ، ظهر العديد من الأمريكيين الأفارقة كقادة سياسيين في الولاية. وتم تمثيل ألباما في الكونجرس خلال هذه الفترة من قبل ثلاثة أعضاء كونغرس أمريكيين من أصل أفريقي: جيريمياه هارالسون، بنجامين إس. تورنر، و جيمس تي رابير .[53]

بعد الحرب ، ظلت الدولة زراعية بشكل رئيسي ، مع اقتصاد مرتبط بالقطن. خلال فترة إعادة البناء ، صدق المشرّعون في الولاية على دستور الولاية الجديد في عام 1868 الذي أنشأ أول نظام مدرسي عام في الولاية ووسّع حقوق المرأة. قام المشرعون بتمويل العديد من مشاريع الطرق العامة والسكك الحديدية، على الرغم من أنها عانت من مزاعم الاحتيال و الاختلاس.[53] حاولت مجموعات المقاومة المنظمة المتمردة قمع المحررين والجمهوريين. إلى جانب النسخة الأصلية وقصيرة العمر من مجموعة كو كلوكس كلان، تضمنت المجموعات الوجوه الشاحبة ، فرسان الكاميليا البيضاء ، القمصان الحمراء ، والرابطة البيضاء.[53]

انتهت إعادة الإعمار في ألباما في عام 1874 ، عندما استعاد الديمقراطيون السيطرة على الهيئة التشريعية ومكتب الحاكم من خلال انتخابات سيطر عليها الاحتيال والعنف. وكتبوا دستوراً آخر في عام 1875،[53] وأقر المجلس التشريعي تعديل بلاين ، الذي يحظر استخدام الأموال العامة في تمويل المدارس المرتبطة بالدين.[54] في العام نفسه، تمت الموافقة على تشريع دعا إلى الفصل العنصري schools.[55] وتم فصل عربات ركاب السكك الحديدية في عام 1891.[55] After حرم المجلس التشريعي في ولاية ألباما حق التصويت لمعظم الأمريكيين الأفارقة والعديد من البيض الفقراء في دستور عام 1901 ، وأصدر المزيد من قوانين جيم كرو في بداية القرن العشرين لفرض الفصل العنصري في الحياة اليومية.

القرن 20

تضمن دستور ألباما الجديد في عام 1901 أحكاماً بشأن تسجيل الناخبين مما جعل أعداد كبيرة من السكان محرومون من حق التصويت، بما في ذلك جميع الأمريكيين الأفارقة والأمريكيين الأصليين، وعشرات الآلاف من البيض الفقراء، من خلال جعل عملية تسجيل الناخبين صعبة، تتطلب ضريبة الاقتراع و اختبار معرفة القراءة والكتابة.[56] دستور عام 1901 تطلب الفصل العنصري في المدارس العامة. بحلول عام 1903، تم تسجيل 2980 أمريكيا من أصل أفريقي فقط في ألباما، على الرغم من أن ما لا يقل عن 74000 منهم كانوا يعرفون القراءة والكتابة. هذا بالمقارنة مع أكثر من 181 ألف أمريكي من أصل أفريقي مؤهلون للتصويت في عام 1900. وانخفضت الأرقام أكثر في العقود اللاحقة.[57] أقر المجلس التشريعي للولاية قوانين إضافية للفصل العنصري تتعلق بالمرافق العامة في الخمسينيات من القرن الماضي: تم فصل السجون في عام 1911؛ المستشفيات في عام 1915؛ دورات المياه والفنادق والمطاعم في عام 1928؛ وغرف الانتظار في مواقف الحافلات عام 1945.[55]

في حين أن طبقة المزارعين قد أقنعت البيض الفقراء بالتصويت لهذا الجهد التشريعي لقمع التصويت الأسود، أدت القيود الجديدة إلى حرمانهم من حق التصويت أيضاً، ويرجع ذلك في الغالب إلى فرض ضريبة الاقتراع التراكمية. [57] بحلول عام 1941 ، شكل البيض أغلبية طفيفة من المحرومين من هذه القوانين: 600.000 من البيض مقابل 520.000 من الأمريكيين الأفارقة.[57] فقد جميع الأمريكيين الأفارقة تقريباً القدرة على التصويت. على الرغم من التحديات القانونية العديدة التي نجحت في إلغاء بعض الأحكام، فإن المجلس التشريعي للولاية خلق أحكاماً جديدة للحفاظ على الحرمان من الحقوق. واستمر استبعاد السود من النظام السياسي حتى بعد تمرير تشريع الحقوق المدنية الفيدرالية في عام 1965 لفرض حقوقهم الدستورية كمواطنين. [58]

كانت الهيئة التشريعية في ولاية ألباما التي يهيمن عليها الريف تعاني باستمرار من نقص في تمويل المدارس والخدمات للأمريكيين الأفارقة المحرومين من حقوقهم ، لكنها لم تعفهم من دفع الضرائب .[45] جزئياً كرد فعل على النقص المزمن في التعليم للأمريكيين الأفارقة في الجنوب ، بدأ صندوق روزينوالد بتمويل بناء ما أصبح يُعرف باسم مدارس روزينوالد. تم تصميم هذه المدارس في ألباما وتم تمويل البناء جزئياً من أموال روزينوالد، الذي دفع ثلث تكاليف البناء. طلب الصندوق من المجتمع المحلي والدولة جمع أموال مماثلة لدفع الباقي. قام السكان السود بفرض ضرائب على أنفسهم مرتين، وذلك عن طريق جمع أموال إضافية لتوفير أموال مماثلة لمثل هذه المدارس ، التي تم بناؤها في العديد من المناطق الريفية. وغالباً ما تبرعوا بالأرض والعمالة أيضاً. [59]

ابتداء من عام 1913 ، تم بناء أول 80 مدرسة من مدارس روزينوالد في ولاية ألباما للأطفال الأمريكيين من أصل أفريقي. تم الانتهاء من 387 مدرسة وسبعة منازل للمعلمين والعديد من المباني المهنية بحلول عام 1937 في الولاية. العديد من المباني المدرسية الباقية في الولاية مدرجة الآن في السجل الوطني للأماكن التاريخية .[59]

أدى استمرار التمييز العنصري و الإعدام خارج نطاق القانون، والكساد الزراعي، وفشل محاصيل القطن بسبب انتشار خنفساء لوزة القطن، إلى قيام عشرات الآلاف من الأمريكيين الأفارقة من ريف ألباما وولايات أخرى بالبحث عن فرص في المدن الشمالية والغربية الوسطى خلال العقود الأولى من القرن العشرين كجزء من الهجرة الكبرى من الجنوب. [60][61] انعكاساً لهذه الهجرة ، انخفض معدل النمو السكاني في ألباما (انظر جدول "السكان التاريخي" أدناه) بمقدار النصف تقريباً من عام 1910 إلى عام 1920. [62]

في الوقت نفسه، هاجر العديد من سكان الريف إلى مدينة برمنگهام للعمل في وظائف صناعية جديدة. شهدت برمنگهام نمواً سريعاً وسميت "المدينة السحرية" .[63] بحلول عام 1920 ، كانت برمنگهام المدينة السادسة والثلاثين الأكبر في الولايات المتحدة. [64] كانت الصناعة الثقيلة والتعدين أساس اقتصادها. كان تمثيل سكانها ناقصاً لعقود في المجلس التشريعي للولاية، والذي رفض إعادة تقسيم الدوائر بعد كل تعداد عشري وفقاً للتغيرات السكانية، كما يقتضي بموجب دستور الولاية. لم يتغير هذا حتى أواخر الستينيات بعد دعوى قضائية وأمر من المحكمة .[65]

ابتداءً من الأربعينيات ، عندما بدأت المحاكم في اتخاذ الخطوات الأولى للاعتراف بحقوق التصويت للناخبين السود ، اتخذ المجلس التشريعي في ولاية ألباما العديد من الخطوات المضادة المصممة لحرمان الناخبين السود. أقر المجلس التشريعي ، وصدق الناخبون [لأن هؤلاء كانوا في الغالب من الناخبين البيض] ، تعديلاً دستورياً للولاية أعطى المسجلين المحليين حرية أكبر في استبعاد المتقدمين لتسجيل الناخبين. نجح المواطنون السود في موبيل في تحدي هذا التعديل باعتباره انتهاكاً لـالتعديل الخامس عشر. كما قام المجلس التشريعي بتغيير حدود توسكيگي إلى شكل من 28 جانباً مصمماً لإبعاد السود عن حدود المدينة. قررت المحكمة العليا بالإجماع أن هذا "التلاعب" العنصري ينتهك الدستور. في عام 1961 ، ...قام المجلس التشريعي في ولاية ألباما أيضاً بتخفيف تأثير تصويت السود عن قصد من خلال وضع متطلبات المكان المرقمة للانتخابات المحلية. [66]

جلبت التنمية الصناعية المتعلقة بمتطلبات الحرب العالمية الثانية مستوى من الازدهار للولاية لم تشهده منذ ما قبل الحرب الأهلية. [45] تدفق العمال الريفيون على أكبر مدن الولاية من أجل وظائف أفضل ومستوى معيشة أعلى. أحد الأمثلة على هذا التدفق الهائل للعمال حدث في موبيل. بين عامي 1940 و 1943 ، انتقل أكثر من 89000 شخص إلى المدينة للعمل في الصناعات المرتبطة بالحرب. [67] تلاشت أهمية القطن وغيره من المحاصيل النقدية مع تطوير الدولة لقاعدة التصنيع والخدمات .

على الرغم من التغيرات السكانية الهائلة في الولاية من 1901 إلى 1961 ، رفض المجلس التشريعي الذي يهيمن عليه الريف إعادة توزيع مقاعد مجلس النواب ومجلس الشيوخ على أساس عدد السكان، كما ينص دستور الولاية لمتابعة نتائج التعدادات العشرية. وتمسكوا بالتمثيل القديم للحفاظ على القوة السياسية والاقتصادية في المناطق الزراعية. كانت إحدى النتائج أن مقاطعة گيفرسون، التي تحتوي على القوة الصناعية والاقتصادية في برمنگهام، ساهمت بأكثر من ثلث إجمالي الإيرادات الضريبية للولاية ، لكنها لم تحصل على مبلغ نسبي من الخدمات. وكانت المصالح الحضرية ممثلة تمثيلا ناقصا باستمرار في الهيئة التشريعية. أشارت دراسة أجريت عام 1960 إلى أنه بسبب الهيمنة الريفية، فإن "أقلية تبلغ حوالي 25٪ من إجمالي سكان الولاية يسيطرون على الأغلبية في المجلس التشريعي في ولاية ألباما. "[68][65]

وفي قضيتي المحكمة العليا للولايات المتحدة بيكر ضد كار (1962) ورينولدز ضد سيمز (1964)، قضت المحكمة بأن مبدأ "رجل واحد، صوت واحد" يجب أن يكون أساس مجلسي الولاية التشريعيين، وأن دوائرهما يجب أن تستند إلى عدد سكاني وليس إلى المقاطعات الجغرافية.[69][70]

في عام 1972 ، ولأول مرة منذ عام 1901، أكمل المجلس التشريعي إعادة تقسيم الدوائر في الكونغرس على أساس التعداد العشري. وقد أفاد هذا المناطق الحضرية التي نشأت ، وكذلك جميع السكان الذين كانوا ممثلين تمثيلا ناقصا لأكثر من ستين عاما. [68] وأجريت تغييرات أخرى لتنفيذ دوائر مجلسي النواب والشيوخ.

واصل الأمريكيون الأفارقة الضغط في الخمسينيات والستينيات من القرن الماضي لإنهاء الحرمان والفصل العنصري في الدولة من خلال حركة الحقوق المدنية ، بما في ذلك التحديات القانونية. في عام 1954 ، قضت المحكمة العليا الأمريكية في قضية براون ضد مجلس التعليم بأنه يجب إلغاء الفصل العنصري في المدارس العامة، لكن ألباما كانت بطيئة في الامتثال. خلال الستينيات ، في عهد الحاكم جورج والاس ، قاومت ألباما الامتثال للمطالب الفيدرالية الخاصة بـ إلغاء الفصل العنصري .[71][72] كان لحركة الحقوق المدنية أحداث بارزة في ألباما ، بما في ذلك مقاطعة حافلة مونتگومري (1955–56) ، رحلات الحرية في عام 1961 ، ومسيرات سلمى إلى مونتگومري في 1965 .[73] ساهم ذلك في إقرار وإصدار قانون الحقوق المدنية لعام 1964 و قانون حقوق التصويت لعام 1965 من قبل الكونغرس الأمريكي .[74][75]

انتهى الفصل القانوني في الولايات في عام 1964، ولكن غالباً ما استمر استخدام تقاليد جيم كرو حتى تم الطعن فيها في المحكمة خصيصاً.[76] وفقاً لـ نيويورك تايمز، بحلول عام 2017، كان العديد من الأميركيين الأفارقة في ولاية ألباما يعيشون في مدن ألباما مثل برمنغهام ومونتغمري. أيضاً، منطقة الحزام الأسود عبر وسط ألباما "وهي موطن للأقاليم الفقيرة إلى حد كبير التي يغلب عليها السكان من الأميركيين الأفارقة. وتشمل هذه المقاطعات دالاس، لاونديز، مارينغو و پيري."[77]

قامت ألباما ببعض التغييرات منذ أواخر القرن العشرين واستخدمت أنواعاً جديدة من التصويت لزيادة التمثيل. في الثمانينيات من القرن الماضي ، طُعنت قضية إعادة تقسيم المنطقة الانتخابية ، ديلارد ضد مقاطعة كرينشو ، في التصويت العمومي على مقاعد تمثيلية لـ 180 ولاية قضائية في ولاية ألباما ، بما في ذلك المقاطعات ومجالس المدارس. أدى التصويت العام إلى إضعاف أصوات أي أقلية في المقاطعة، حيث تميل الأغلبية إلى شغل جميع المقاعد. على الرغم من أن الأمريكيين الأفارقة يشكلون أقلية كبيرة في الولاية، إلا أنهم لم يتمكنوا من انتخاب أي ممثلين في معظم الولايات القضائية العامة.[66]

كجزء من تسوية هذه القضية، اعتمدت خمس مدن ومقاطعات في ألباما ، بما في ذلك مقاطعة شيلتون ، نظام التصويت التراكمي لانتخاب الممثلين في الولايات القضائية متعددة المقاعد. وقد أدى ذلك إلى زيادة التمثيل النسبي للناخبين. في شكل آخر من أشكال التمثيل النسبي، تستخدم 23 ولاية قضائية تصويتاً محدوداً، كما هو الحال في مقاطعة كونيكو. في عام 1982 ، تم اختبار التصويت المحدود لأول مرة في مقاطعة كونيكو. أدى استخدام هذه الأنظمة معاً إلى زيادة عدد الأمريكيين من أصل أفريقي والنساء المنتخبات لمناصب محلية، مما أدى إلى ظهور حكومات أكثر تمثيلاً لمواطنيها.[78]

ابتداءً من الستينيات، تحول اقتصاد الولاية بعيداً عن صناعاته التقليدية كالأخشاب والصلب والنسيج بسبب المنافسة الأجنبية المتزايدة. وظائف الصلب ، على سبيل المثال ، انخفضت من 46314 في عام 1950 إلى 14185 في عام 2011.[79] ومع ذلك، استفادت الولاية وخاصة هانتسفيل، من افتتاح مركز مارشال لبعثات الفضاء في عام 1960 ، وهو منشأة رئيسية في تطوير برنامج صاروخ زحل ومكوك الفضاء. حلت صناعات التكنولوجيا والتصنيع، مثل تجميع السيارات، محل بعض الصناعات القديمة في الولاية في أواخر القرن العشرين، ولكن اقتصاد الولاية ونموها تخلفا عن الولايات الأخرى في المنطقة، مثل جورجيا وفلوريدا.[80]

القرن 21

في عام 2001 ، نصب رئيس المحكمة العليا في ألباما روي مور نصباً لـ الوصايا العشر في مبنى الكابيتول في مونتغمري. في عام 2002، أمرت محكمة الدائرة الأمريكية الحادية عشرة بإزالة التمثال، لكن مور رفض اتباع أمر المحكمة، مما أدى إلى احتجاجات حول مبنى الكابيتول لصالح الاحتفاظ بالنصب التذكاري. تمت إزالة النصب التذكاري في أغسطس 2003.[81]

عصفت الكوارث الطبيعية بالدولة في القرن الحادي والعشرين. ففي عام 2004 ، ضرب إعصار إيڤان الولاية، وهو عاصفة من الفئة الثالثة عند وصول اليابسة، وتسبب في أضرار تزيد عن 18 مليار دولار. وكان من أكثر العواصف تدميراً التي ضربت الدولة في تاريخها الحديث.[82] ضرب إعصار قمعي من 62 إعصاراً الولاية في أبريل 2011 وقتل 238 شخصاً، مما أدى إلى تدمير العديد من المجتمعات.[83]

الجغرافيا

ألباما هي الولاية الثلاثين من حيث الحجم في الولايات المتحدة بمساحة 52،419 ميل مربع (135،760 كم 2). من إجمالي المساحة: 3.2٪ عبارة عن مياه، مما يجعل ألباما في المرتبة 23 من حيث مقدار المياه السطحية، مما يمنحها أيضاً ثاني أكبر نظام ممر مائي داخلي في الولايات المتحدة.[84] حوالي ثلاثة أخماس مساحة الأرض سهل لطيف مع منحدر عام نحو نهر المسيسپي و خليج المكسيك. منطقة شمال ألباما جبلية في الغالب، حيث يقطع نهر تينيسي وادياً كبيراً مخلفاًالعديد من الجداول والأنهار والجبال والبحيرات.[85]

تحد ولاية ألباما من الشمال ولايات تنسي و جورجيا من الشرق وفلوريدا من الجنوب و مسيسپي من الغرب. وتملك ألباما خطاً ساحلياً على خليج المكسيك، في أقصى الطرف الجنوبي من الولاية.[85] يتراوح ارتفاع الولاية عن مستوى سطح البحر[86] في خليج موبيل إلى ما يقرب من نصف ميل في الشمال الشرقي ، وفي جبال تشيها إلى [85] 2،413 ft (735 m).[87]

تتكون أراضي ألباما من 22 مليون أكر (89000 كيلو متر مربع) من الغابات أو 67٪ من إجمالي مساحة الأرض.[88] تقع ضواحي مقاطعة بالدوين، على طول ساحل الخليج ، وهي أكبر مقاطعة في الولاية من حيث مساحة الأرض ومنطقة المياه.[89]

تشمل المناطق في ولاية ألباما التي تديرها مصلحة المنتزهات الوطنية حديقة هورس شو بيند القومية العسكرية بالقرب من ألكسندر سيتي; محمية ليتل ريفر كانيون الوطنية بالقرب من ڤورت پاين; نصب راسل الكهف الوطني في بريدجبورت؛ متحف التاريخ في توسكيجي الوطني في توسكيجي; و المتنزه الوطني في توسكيجي بالقرب من توسكيجي.[90] بالإضافة إلى ذلك ، تمتلك ألباما أربعة غابات وطنية: كونيكو ، تالاديجا ، توسكيجي ، ويليام ب. بانكهد.[91] تحتوي ألاباما أيضاً على ناتشيز تراك باركواي و مسار سيلما إلى مونتجومري التاريخي الوطني و درب الدموع التاريخي الوطني. وتشمل عجائب الطبيعة البارزة: صخرة "ناتشرل بريدگ" ، أطول جسر طبيعي شرق روكي، وتقع إلى الجنوب من هاليڤيل; منتزه كاثيدرال كاڤيرنز في مقاطعة مارشال، سميت كذلك لمظهرها الشبيه بالكاتدرائية، وتتميز بواحد من أكبر مداخل الكهوف والصواعد في العالم; وإيكور روج في فيرهوب، أعلى نقطة ساحلية بين مين والمكسيك؛[92] DeSoto Caverns in Childersburg, the first officially recorded cave in the United States;[93] Noccalula Falls in Gadsden features a 90-foot waterfall; Dismals Canyon near Phil Campbell, home to two waterfalls, six natural bridges and allegedly served as a hideout for legendary outlaw Jesse James;[94] Stephens Gap Cave in Jackson County boasts a 143-foot pit, two waterfalls and is one of the most photographed wild cave scenes in America;[95] Little River Canyon near Fort Payne, one of the nation's longest mountaintop rivers; Rickwood Caverns near Warrior features an underground pool, blind cave fish and 260-million-year-old limestone formations; and the Walls of Jericho canyon on the Alabama-Tennessee state line.

A 5-ميل (8 km)-wide meteorite impact crater is located in Elmore County, just north of Montgomery. This is the Wetumpka crater, the site of "Alabama's greatest natural disaster". A 1،000-قدم (300 m)-wide meteorite hit the area about 80 million years ago.[96] The hills just east of downtown Wetumpka showcase the eroded remains of the impact crater that was blasted into the bedrock, with the area labeled the Wetumpka crater or astrobleme ("star-wound") because of the concentric rings of fractures and zones of shattered rock that can be found beneath the surface.[97] In 2002, Christian Koeberl with the Institute of Geochemistry University of Vienna published evidence and established the site as the 157th recognized impact crater on Earth.[98]

المناخ

| درجات الحرارة الصغرى والكبرى في مختلف مدن ألباما [°ف (°س)] | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| الشهر | يناير | فبراير | مارس | أبريل | مايو | يونيو | يوليو | أغسطس | سبتمبر | أكتوبر | نوفمبر | ديسمبر | السنة | ||

| هنتسڤيل | الكبرى | 48.9 (9.4) |

54.6 (12.6) |

63.4 (17.4) |

72.3 (22.4) |

79.6 (26.4) |

86.5 (30.3) |

89.4 (31.9) |

89.0 (31.7) |

83.0 (28.3) |

72.9 (22.7) |

61.6 (16.4) |

52.4 (11.3) |

71.1 (21.7) | |

| الصغرى | 30.7 (-0.7) |

34.0 (1.1) |

41.2 (5.1) |

48.4 (9.1) |

57.5 (14.2) |

65.4 (18.6) |

69.5 (20.8) |

68.1 (20.1) |

61.7 (16.5) |

49.6 (9.8) |

40.7 (4.8) |

33.8 (1.0) |

50.1 (10.1) | ||

| برمنگهام | الكبرى | 52.8 (11.6) |

58.3 (14.6) |

66.5 (19.2) |

74.1 (23.4) |

81.0 (27.2) |

87.5 (30.8) |

90.6 (32.6) |

90.2 (32.3) |

84.6 (29.2) |

74.9 (23.8) |

64.5 (18.1) |

56.0 (13.3) |

73.4 (23.0) | |

| الصغرى | 32.3 (0.2) |

35.4 (1.9) |

42.4 (5.8) |

48.4 (9.1) |

57.6 (14.2) |

65.4 (18.6) |

69.7 (20.9) |

68.9 (20.5) |

63.0 (17.2) |

50.9 (10.5) |

41.8 (5.4) |

35.2 (1.8) |

50.9 (10.5) | ||

| مونتگمري | الكبرى | 57.6 (14.2) |

62.4 (16.9) |

70.5 (21.4) |

77.5 (25.3) |

84.6 (29.2) |

90.6 (32.6) |

92.7 (33.7) |

92.2 (33.4) |

87.7 (30.9) |

78.7 (25.9) |

68.7 (20.4) |

60.3 (15.7) |

77.0 (25.0) | |

| الصغرى | 35.5 (1.9) |

38.6 (3.7) |

45.4 (7.4) |

52.1 (11.2) |

60.1 (15.6) |

67.3 (19.6) |

70.9 (21.6) |

70.1 (21.2) |

64.9 (18.3) |

52.2 (11.2) |

43.5 (6.4) |

37.6 (3.1) |

53.2 (11.8) | ||

| موبيل | الكبرى | 60.7 (15.9) |

64.5 (18.1) |

71.2 (21.8) |

77.4 (25.2) |

84.2 (29.0) |

89.4 (31.9) |

91.2 (32.9) |

90.8 (32.7) |

86.8 (30.4) |

79.2 (26.2) |

70.1 (21.2) |

62.9 (17.2) |

77.4 (25.2) | |

| الصغرى | 39.5 (4.2) |

42.4 (5.8) |

49.2 (9.6) |

54.8 (12.7) |

62.8 (17.1) |

69.2 (20.7) |

71.8 (22.1) |

71.7 (22.0) |

67.6 (19.8) |

56.3 (13.5) |

47.8 (8.8) |

41.6 (5.3) |

56.2 (13.4) | ||

| Source: NOAA[99][100][101][102] | |||||||||||||||

الحياة النباتية والحيوانية

Alabama is home to a diverse array of flora and fauna in habitats that range from the Tennessee Valley, Appalachian Plateau, and Ridge-and-Valley Appalachians of the north to the Piedmont, Canebrake, and Black Belt of the central region to the Gulf Coastal Plain and beaches along the Gulf of Mexico in the south. The state is usually ranked among the top in nation for its range of overall biodiversity.[103][104]

Alabama is in the subtropical coniferous forest biome and once boasted huge expanses of pine forest, which still form the largest proportion of forests in the state.[103] It currently ranks fifth in the nation for the diversity of its flora. It is home to nearly 4,000 pteridophyte and spermatophyte plant species.[105]

Indigenous animal species in the state include 62 mammal species,[106] 93 reptile species,[107] 73 amphibian species,[108] roughly 307 native freshwater fish species,[103] and 420 bird species that spend at least part of their year within the state.[109] Invertebrates include 97 crayfish species and 383 mollusk species. 113 of these mollusk species have never been collected outside the state.[110][111]

الديموغرافيا

| التعداد | Pop. | ملاحظة | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1800 | 1٬250 | — | |

| 1810 | 9٬046 | 623٫7% | |

| 1820 | 127٬901 | 1٬313٫9% | |

| 1830 | 309٬527 | 142�0% | |

| 1840 | 590٬756 | 90٫9% | |

| 1850 | 771٬623 | 30٫6% | |

| 1860 | 964٬201 | 25�0% | |

| 1870 | 996٬992 | 3٫4% | |

| 1880 | 1٬262٬505 | 26٫6% | |

| 1890 | 1٬513٬401 | 19٫9% | |

| 1900 | 1٬828٬697 | 20٫8% | |

| 1910 | 2٬138٬093 | 16٫9% | |

| 1920 | 2٬348٬174 | 9٫8% | |

| 1930 | 2٬646٬248 | 12٫7% | |

| 1940 | 2٬832٬961 | 7٫1% | |

| 1950 | 3٬061٬743 | 8٫1% | |

| 1960 | 3٬266٬740 | 6٫7% | |

| 1970 | 3٬444٬165 | 5٫4% | |

| 1980 | 3٬893٬888 | 13٫1% | |

| 1990 | 4٬040٬587 | 3٫8% | |

| 2000 | 4٬447٬100 | 10٫1% | |

| 2010 | 4٬779٬745 | 7٫5% | |

| 2019 (تق.) | 4٬903٬185 | 2٫6% | |

| Sources: 1910–2010[62] 2019 estimate[112] | |||

التركيبة العرقية

| Racial composition | 1990[113] | 2000[114] | 2010[115] |

|---|---|---|---|

| White | 73.6% | 71.1% | 68.5% |

| Black | 25.3% | 26% | 26.2% |

| Asian | 0.5% | 0.7% | 1.1% |

| Native | 0.4% | 0.5% | 0.6% |

| Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Islander |

— | — | 0.1% |

| Other race | 0.1% | 0.6% | 2% |

| Two or more races | — | 1% | 1.5% |

المناطق الكبرى والمعينة احصائياً

| Rank | Combined statistical area | Population (2019 estimate) | Population (2010 Census) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Birmingham–Hoover–Talladega | 1,317,702 | 1,302,283 |

| 2 | Chattanooga–Cleveland–Dalton[CSA 1] | 1,004,573 | 923,460 |

| 3 | Huntsville–Decatur–Albertville | 792,714 | 735,550 |

| 4 | Mobile–Daphne–Fairhope | 652,770 | 595,257 |

| 5 | Columbus–Auburn–Opelika[CSA 2] | 485,590 | 448,035 |

| 6 | Dothan–Enterprise–Ozark | 250,872 | 245,838 |

| Rank | Metropolitan area | Population (2019 estimate) | Population (2010 Census) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Birmingham–Hoover | 1,090,435 | 1,061,024 |

| 2 | Huntsville | 471,824 | 417,593 |

| 3 | Mobile | 429,536 | 430,573 |

| 4 | Montgomery | 373,290 | 374,536 |

| 5 | Tuscaloosa | 252,047 | 239,207 |

| 6 | Daphne–Fairhope–Foley | 218,022 | 182,265 |

| 7 | Auburn–Opelika | 164,542 | 140,247 |

| 8 | Decatur | 152,603 | 153,829 |

| 9 | Dothan | 149,358 | 145,639 |

| 10 | Florence–Muscle Shoals | 147,970 | 147,137 |

| 11 | Anniston–Oxford–Jacksonville | 113,605 | 118,572 |

| 12 | Gadsden | 102,268 | 104,430 |

المدن

| Rank | City | Population (2019 census estimates) |

County(ies) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Birmingham | 209٬403 | Jefferson, Shelby |

| 2 | Huntsville | 200٬574 | Madison, Limestone, Morgan |

| 3 | Montgomery | 198٬525 | Montgomery |

| 4 | Mobile | 188٬720 | Mobile |

| 5 | Tuscaloosa | 101٬129 | Tuscaloosa |

| 6 | Hoover | 85٬768 | Jefferson, Shelby |

| 7 | Dothan | 68٬941 | Houston, Dale, Henry |

| 8 | Auburn | 66٬259 | Lee |

| 9 | Decatur | 54٬445 | Morgan, Limestone |

| 10 | Madison | 51٬593 | Madison, Limestone |

| 11 | Florence | 40٬797 | Lauderdale |

| 12 | Phenix City | 36٬487 | Russell |

| 13 | Prattville | 35٬957 | Autauga, Elmore |

| 14 | Gadsden | 35٬000 | Etowah |

| 15 | Vestavia Hills | 34٬413 | Jefferson, Shelby |

اللغات

| Language | Percentage of population (اعتبارا من 2010[تحديث])[118] |

|---|---|

| Spanish | 2.2% |

| German | 0.4% |

| French (incl. Patois, Cajun) | 0.3% |

| Chinese, Vietnamese, Korean, Arabic, African languages, Japanese, and Italian (tied) | 0.1% |

الديانات

| Affiliation | % of population | |

|---|---|---|

| Christian | 86 | |

| Protestant | 78 | |

| Evangelical Protestant | 49 | |

| Mainline Protestant | 13 | |

| Black church | 16 | |

| Catholic | 7 | |

| Mormon | 1 | |

| Jehovah's Witnesses | 0.1 | |

| Eastern Orthodox | 0.1 | |

| Other Christian | 0.1 | |

| Unaffiliated | 12 | |

| Nothing in particular | 9 | |

| Agnostic | 1 | |

| Atheist | 1 | |

| Non-Christian faiths | 1 | |

| Jewish | 0.2 | |

| Muslim | 0.2 | |

| Buddhist | 0.2 | |

| Hindu | 0.2 | |

| Other Non-Christian faiths | 0.2 | |

| Don't know/refused answer | 1 | |

| Total | 100 | |

الصحة

A Centers for Disease Control and Prevention study in 2008 showed that obesity in Alabama is a problem, with most counties having more than 29% of adults obese, except for ten which had a rate between 26% and 29%.[120] Residents of the state, along with those in five other states, were least likely in the nation to be physically active during leisure time.[121] Alabama, and the southeastern U.S. in general, has one of the highest incidences of adult onset diabetes in the country, exceeding 10% of adults.[122][123]

On May 14, 2019, Alabama passed the Human Life Protection Act, banning abortion at any stage of pregnancy unless there is a "serious health risk", with no exceptions for rape and incest. The law, if enacted, would punish doctors who perform abortions with 10 to 99 years imprisonment and be the most restrictive abortion law in the country.[124] However, on October 29, 2019, U.S. District Judge Myron Thompson blocked the law from taking effect.[125]

الاقتصاد

The state has invested in aerospace, education, health care, banking, and various heavy industries, including automobile manufacturing, mineral extraction, steel production and fabrication. By 2006, crop and animal production in Alabama was valued at $1.5 billion. In contrast to the primarily agricultural economy of the previous century, this was only about one percent of the state's gross domestic product. The number of private farms has declined at a steady rate since the 1960s, as land has been sold to developers, timber companies, and large farming conglomerates.[126]

Non-agricultural employment in 2008 was 121,800 in management occupations; 71,750 in business and financial operations; 36,790 in computer-related and mathematical occupation; 44,200 in architecture and engineering; 12,410 in life, physical, and social sciences; 32,260 in community and social services; 12,770 in legal occupations; 116,250 in education, training, and library services; 27,840 in art, design and media occupations; 121,110 in healthcare; 44,750 in fire fighting, law enforcement, and security; 154,040 in food preparation and serving; 76,650 in building and grounds cleaning and maintenance; 53,230 in personal care and services; 244,510 in sales; 338,760 in office and administration support; 20,510 in farming, fishing, and forestry; 120,155 in construction and mining, gas, and oil extraction; 106,280 in installation, maintenance, and repair; 224,110 in production; and 167,160 in transportation and material moving.[12]

According to the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, the 2008 total gross state product was $170 billion, or $29,411 per capita. Alabama's 2012 GDP increased 1.2% from the previous year. The single largest increase came in the area of information.[127] In 2010, per capita income for the state was $22,984.[128]

The state's seasonally adjusted unemployment rate was 5.8% in April 2015.[129] This compared to a nationwide seasonally adjusted rate of 5.4%.[130]

Alabama has no minimum wage and in February 2016 passed legislation preventing municipalities from setting one. (A Birmingham city ordinance would have raised theirs to $10.10.)[131]

اعتبارا من 2018[تحديث], Alabama has the sixth highest poverty rate among states in the U.S.[132] In 2017, United Nations Special Rapporteur Philip Alston toured parts of rural Alabama and observed environmental conditions he said were poorer than anywhere he had seen in the developed world.[133]

أكبر أرباب الأعمال

| Employer | Employees |

|---|---|

| Redstone Arsenal | 25,373 |

| University of Alabama at Birmingham (includes UAB Hospital) | 18,750 |

| Maxwell Air Force Base | 12,280 |

| State of Alabama | 9,500 |

| Mobile County Public School System | 8,100 |

The next twenty largest employers, اعتبارا من 2011[تحديث], included:[134]

| Employer | Location |

|---|---|

| Anniston Army Depot | Anniston |

| AT&T | Multiple |

| Auburn University | Auburn |

| Baptist Medical Center South | Montgomery |

| Birmingham City Schools | Birmingham |

| City of Birmingham | Birmingham |

| DCH Health System | Tuscaloosa |

| Huntsville City Schools | Huntsville |

| Huntsville Hospital System | Huntsville |

| Hyundai Motor Manufacturing Alabama | Montgomery |

| Infirmary Health System | Mobile |

| Jefferson County Board of Education | Birmingham |

| Marshall Space Flight Center | Huntsville |

| Mercedes-Benz U.S. International | Vance |

| Montgomery Public Schools | Montgomery |

| Regions Financial Corporation | Multiple |

| Boeing | Multiple |

| University of Alabama | Tuscaloosa |

| University of South Alabama | Mobile |

| Walmart | Multiple |

الزراعة

Alabama's agricultural outputs include poultry and eggs, cattle, fish, plant nursery items, peanuts, cotton, grains such as corn and sorghum, vegetables, milk, soybeans, and peaches. Although known as "The Cotton State", Alabama ranks between eighth and tenth in national cotton production, according to various reports,[135][136] with Texas, Georgia and Mississippi comprising the top three.

الصناعة

Alabama's industrial outputs include iron and steel products (including cast-iron and steel pipe); paper, lumber, and wood products; mining (mostly coal); plastic products; cars and trucks; and apparel. In addition, Alabama produces aerospace and electronic products, mostly in the Huntsville area, the location of NASA's George C. Marshall Space Flight Center and the U.S. Army Materiel Command, headquartered at Redstone Arsenal.

A great deal of Alabama's economic growth since the 1990s has been due to the state's expanding automotive manufacturing industry. Located in the state are Honda Manufacturing of Alabama, Hyundai Motor Manufacturing Alabama, Mercedes-Benz U.S. International, and Toyota Motor Manufacturing Alabama, as well as their various suppliers. Since 1993, the automobile industry has generated more than 67,800 new jobs in the state. Alabama currently ranks 4th in the nation for vehicle exports.[137]

Automakers accounted for approximately a third of the industrial expansion in the state in 2012.[138] The eight models produced at the state's auto factories totaled combined sales of 74,335 vehicles for 2012. The strongest model sales during this period were the Hyundai Elantra compact car, the Mercedes-Benz GL-Class sport utility vehicle and the Honda Ridgeline sport utility truck.[139]

Steel producers Outokumpu, Nucor, SSAB, ThyssenKrupp, and U.S. Steel have facilities in Alabama and employ more than 10,000 people. In May 2007, German steelmaker ThyssenKrupp selected Calvert in Mobile County for a 4.65 billion combined stainless and carbon steel processing facility.[140] ThyssenKrupp's stainless steel division, Inoxum, including the stainless portion of the Calvert plant, was sold to Finnish stainless steel company Outokumpu in 2012.[141] The remaining portion of the ThyssenKrupp plant had final bids submitted by ArcelorMittal and Nippon Steel for $1.6 billion in March 2013. Companhia Siderúrgica Nacional submitted a combined bid for the mill at Calvert, plus a majority stake in the ThyssenKrupp mill in Brazil, for $3.8 billion.[142] In July 2013, the plant was sold to ArcelorMittal and Nippon Steel.[143]

The Hunt Refining Company, a subsidiary of Hunt Consolidated, Inc., is based in Tuscaloosa and operates a refinery there. The company also operates terminals in Mobile, Melvin, and Moundville.[144] JVC America, Inc. operates an optical disc replication and packaging plant in Tuscaloosa.[145]

The Goodyear Tire and Rubber Company operates a large plant in Gadsden which employs about 1,400 people. It has been in operation since 1929.

Construction of an Airbus A320 family aircraft assembly plant in Mobile was formally announced by Airbus CEO Fabrice Brégier from the Mobile Convention Center on July 2, 2012. The plans include a $600 million factory at the Brookley Aeroplex for the assembly of the A319, A320 and A321 aircraft. Construction began in 2013, with plans for it to become operable by 2015[needs update] and produce up to 50 aircraft per year by 2017.[146][147] The assembly plant is the company's first factory to be built within the United States.[148] It was announced on February 1, 2013, that Airbus had hired Alabama-based Hoar Construction to oversee construction of the facility.[149]

السياحة والترفيه

According to Business Insider, Alabama ranked 14th in most popular states to visit in 2014.[150] An estimated 26 million tourists visited the state in 2018,[151] more than 100,000 of them from other countries including Canada, the United Kingdom, Germany and Japan.[citation needed] In 2006, 22.3 million travellers spent $8.3 billion providing an estimated 162,000 jobs in the state.[152][153][المصدر لا يؤكد ذلك]

The state is home to various attractions, natural features, parks and events that attract visitors from around the globe, notably the annual Hangout Music Festival, held on the public beaches of Gulf Shores; the Alabama Shakespeare Festival, one of the ten largest Shakespeare festivals in the world;[154] the Robert Trent Jones Golf Trail, a collection of championship caliber golf courses distributed across the state; casinos such as Victoryland; amusement parks such as Alabama Splash Adventure; the Riverchase Galleria, one of the largest shopping centers in the southeast; Guntersville Lake, voted the best lake in Alabama by Southern Living Magazine readers;[155] and the Alabama Museum of Natural History, the oldest museum in the state.[156]

Mobile is known for having the oldest organized Mardi Gras celebration in the United States, beginning in 1703.[157] It was also host to the first formally organized Mardi Gras parade in the United States in 1830, a tradition that continues to this day.[157] Mardi Gras is an official state holiday in Mobile and Baldwin counties.[158]

In 2018, Mobile's Mardi Gras parade was the state's top event, producing the most tourists with an attendance of 892,811. The top attraction was the U.S. Space & Rocket Center in Huntsville with an attendance of 849,981, followed by the Birmingham Zoo with 543,090. Of the parks and natural destinations, Alabama's Gulf Coast topped the list with 6,700,000 visitors.[159]

Alabama has historically been a popular region for film shoots due to its diverse landscapes and contrast of environments.[160] Movies filmed in Alabama include: Close Encounters of the Third Kind, Get Out, 42, Selma, Big Fish, The Final Destination, Due Date, Need For Speed and many more.[161]

الرعاية الصحية

UAB Hospital, USA Health University Hospital, Huntsville Hospital, and Children's Hospital of Alabama are the only Level I trauma centers in Alabama.[162] UAB is the largest state government employer in Alabama, with a workforce of about 18,000.[163] A 2017 study found that Alabama had the least competitive health insurance market in the country, with Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Alabama having a market share of 84% followed by UnitedHealth Group at 7%.[164]

الصرافة

Regions Financial Corporation and BBVA USA Bank are the largest banks headquartered in Alabama. Birmingham-based Compass Bancshares was acquired by Spanish-based BBVA in September 2007 with the headquarters of BBVA USA remaining in Birmingham. In November 2006, Regions Financial acquired AmSouth Bancorporation, which was also headquartered in Birmingham. SouthTrust Corporation, another large bank headquartered in Birmingham, was acquired by Wachovia in 2004.

Wells Fargo has a regional headquarters, an operations center campus, and a $400 million data center in Birmingham. Many smaller banks are also headquartered in the Birmingham area, including ServisFirst and New South Federal Savings Bank. Birmingham also serves as the headquarters for several large investment management companies, including Harbert Management Corporation.

الإلكترونيات والاتصالات

Telecommunications provider AT&T, formerly BellSouth, has a major presence in Alabama with several large offices in Birmingham.

Many commercial technology companies are headquartered in Huntsville, such as network access company ADTRAN, computer graphics company Intergraph, and IT infrastructure company Avocent.

الإنشاءات

Rust International has grown to include Brasfield & Gorrie, BE&K, Hoar Construction, and B.L. Harbert International, which all routinely are included in the Engineering News-Record lists of top design, international construction, and engineering firms. (Rust International was acquired in 2000 by Washington Group International, which was in turn acquired by San-Francisco based URS Corporation in 2007.)

القانون والحكومة

حكومة الولاية

The foundational document for Alabama's government is the Alabama Constitution, which was ratified in 1901. At almost 800 amendments and 310,000 words, it is by some accounts the world's longest constitution and is roughly forty times the length of the United States Constitution.[165][166][167][168]

Alabama's government is divided into three coequal branches. The legislative branch is the Alabama Legislature, a bicameral assembly composed of the Alabama House of Representatives, with 105 members, and the Alabama Senate, with 35 members. The Legislature is responsible for writing, debating, passing, or defeating state legislation. The Republican Party currently holds a majority in both houses of the Legislature. The Legislature has the power to override a gubernatorial veto by a simple majority (most state Legislatures require a two-thirds majority to override a veto).

Until 1964, the state elected state senators on a geographic basis by county, with one per county. It had not redistricted congressional districts since passage of its constitution in 1901; as a result, urbanized areas were grossly underrepresented. It had not changed legislative districts to reflect the decennial censuses, either. In Reynolds v. Sims (1964), the U.S. Supreme Court implemented the principle of "one man, one vote", ruling that congressional districts had to be reapportioned based on censuses (as the state already included in its constitution but had not implemented.) Further, the court ruled that both houses of bicameral state legislatures had to be apportioned by population, as there was no constitutional basis for states to have geographically based systems.

At that time, Alabama and many other states had to change their legislative districting, as many across the country had systems that underrepresented urban areas and districts. This had caused decades of underinvestment in such areas. For instance, Birmingham and Jefferson County taxes had supplied one-third of the state budget, but Jefferson County received only 1/67th of state services in funding. Through the legislative delegations, the Alabama legislature kept control of county governments.

The executive branch is responsible for the execution and oversight of laws. It is headed by the governor of Alabama. Other members of the executive branch include the cabinet, the lieutenant governor of Alabama, the Attorney General of Alabama, the Alabama Secretary of State, the Alabama State Treasurer, and the State Auditor of Alabama. The current governor is Republican Kay Ivey.

The members of the Legislature take office immediately after the November elections. Statewide officials, such as the governor, lieutenant governor, attorney general, and other constitutional officers, take office the following January.[169]

The judicial branch is responsible for interpreting the state's Constitution and applying the law in state criminal and civil cases. The state's highest court is the Supreme Court of Alabama. Alabama uses partisan elections to select judges. Since the 1980s judicial campaigns have become increasingly politicized.[170] The current chief justice of the Alabama Supreme Court is Republican Tom Parker. All sitting justices on the Alabama Supreme Court are members of the Republican Party. There are two intermediate appellate courts, the Court of Civil Appeals and the Court of Criminal Appeals, and four trial courts: the circuit court (trial court of general jurisdiction), and the district, probate, and municipal courts.[170]

Some critics believe the election of judges has contributed to an exceedingly high rate of executions.[171] Alabama has the highest per capita death penalty rate in the country. In some years, it imposes more death sentences than does Texas, a state which has a population five times larger.[172] However, executions per capita are significantly higher in Texas.[173] Some of its cases have been highly controversial; the Supreme Court has overturned[174] 24 convictions in death penalty cases.[citation needed] It was the only state to allow judges to override jury decisions in whether or not to use a death sentence; in 10 cases judges overturned sentences of life imprisonment without parole (LWOP) that were voted unanimously by juries.[172] This judicial authority was removed in April 2017.[175]

الضرائب

Taxes are collected by the Alabama Department of Revenue.[176] Alabama levies a 2, 4, or 5 percent personal income tax, depending on the amount earned and filing status. Taxpayers are allowed to deduct their federal income tax from their Alabama state tax, even if taking the standard deduction; those who itemize can also deduct FICA (the Social Security and Medicare tax).

The state's general sales tax rate is 4%.[177] Sales tax rates for cities and counties are also added to purchases.[178] For example, the total sales tax rate in Mobile is 10% and there is an additional restaurant tax of 1%, which means a diner in Mobile would pay an 11% tax on a meal. اعتبارا من 1999[تحديث], sales and excise taxes in Alabama account for 51% of all state and local revenue, compared with an average of about 36% nationwide.[179] Alabama is one of seven states that levy a tax on food at the same rate as other goods, and one of two states (the other being neighboring Mississippi) which fully taxes groceries without any offsetting relief for low-income families. (Most states exempt groceries from sales tax or apply a lower tax rate.)[180]

Alabama's income tax on poor working families is among the highest in the U.S.[179] Alabama is the only state that levies income tax on a family of four with income as low as $4,600, which is barely one-quarter the federal poverty line.[179] Alabama's threshold is the lowest among the 41 states and the District of Columbia with income taxes.[179]

The corporate income tax rate is currently 6.5%. The overall federal, state, and local tax burden in Alabama ranks the state as the second least tax-burdened state in the country.[181] Property taxes are the lowest in the U.S. The current state constitution requires a voter referendum to raise property taxes.

Since Alabama's tax structure largely depends on consumer spending, it is subject to high variable budget structure. For example, in 2003, Alabama had an annual budget deficit as high as $670 million.

حكومات المقاطعات والحكومات المحلية

| Rank | County | Population (2019 Estimate) |

Population (2010 Census) |

Seat | Largest city |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Jefferson | 658,573 | 658,466 | Birmingham | Birmingham |

| 2 | Mobile | 413,210 | 412,992 | Mobile | Mobile |

| 3 | Madison | 372,909 | 334,811 | Huntsville | Huntsville |

| 4 | Montgomery | 226,486 | 229,363 | Montgomery | Montgomery |

| 5 | Shelby | 217,702 | 195,085 | Columbiana | Hoover (part) Alabaster |

| 6 | Baldwin | 223,234 | 182,265 | Bay Minette | Daphne |

| 7 | Tuscaloosa | 209,355 | 194,656 | Tuscaloosa | Tuscaloosa |

| 8 | Lee | 164,542 | 140,247 | Opelika | Auburn |

| 9 | Morgan | 119,679 | 119,490 | Decatur | Decatur |

| 10 | Calhoun | 113,605 | 118,572 | Anniston | Anniston |

| 11 | Houston | 105,882 | 101,547 | Dothan | Dothan |

| 12 | Etowah | 102,268 | 104,303 | Gadsden | Gadsden |

| 13 | Limestone | 98,915 | 82,782 | Athens | Athens |

| 14 | Marshall | 96,774 | 93,019 | Guntersville | Albertville |

| 15 | Lauderdale | 92,729 | 92,709 | Florence | Florence |

السياسة

During Reconstruction following the American Civil War, Alabama was occupied by federal troops of the Third Military District under General John Pope. In 1874, the political coalition of white Democrats known as the Redeemers took control of the state government from the Republicans, in part by suppressing the black vote through violence, fraud and intimidation.

After 1890, a coalition of White Democratic politicians passed laws to segregate and disenfranchise African American residents, a process completed in provisions of the 1901 constitution. Provisions which disenfranchised blacks resulted in excluding many poor Whites. By 1941 more Whites than Blacks had been disenfranchised: 600,000 to 520,000. The total effects were greater on the black community, as almost all its citizens were disfranchised and relegated to separate and unequal treatment under the law.

From 1901 through the 1960s, the state did not redraw election districts as population grew and shifted within the state during urbanization and industrialization of certain areas. As counties were the basis of election districts, the result was a rural minority that dominated state politics through nearly three-quarters of the century, until a series of federal court cases required redistricting in 1972 to meet equal representation.

Alabama state politics gained nationwide and international attention in the 1950s and 1960s during the civil rights movement, when whites bureaucratically, and at times violently, resisted protests for electoral and social reform. Governor George Wallace, the state's only four-term governor, was a controversial figure who vowed to maintain segregation. Only after passage of the federal Civil Rights Act of 1964[74] and Voting Rights Act of 1965 did African Americans regain the ability to exercise suffrage, among other civil rights. In many jurisdictions, they continued to be excluded from representation by at-large electoral systems, which allowed the majority of the population to dominate elections. Some changes at the county level have occurred following court challenges to establish single-member districts that enable a more diverse representation among county boards.

In 2007, the Alabama Legislature passed, and Republican governor Bob Riley signed a resolution expressing "profound regret" over slavery and its lingering impact. In a symbolic ceremony, the bill was signed in the Alabama State Capitol, which housed Congress of the Confederate States of America.[182]

In 2010, Republicans won control of both houses of the legislature for the first time in 136 years.[183]

اعتبارا من ديسمبر 2017[تحديث], there are a total of 3,326,812 registered voters, with 2,979,576 active, and the others inactive in the state.[184]

الانتخابات

انتخابات الولاية

With the disfranchisement of Blacks in 1901, the state became part of the "Solid South", a system in which the Democratic Party operated as effectively the only viable political party in every Southern state. For nearly a hundred years local and state elections in Alabama were decided in the Democratic Party primary, with generally only token Republican challengers running in the General Election. Since the mid- to late 20th century, however, white conservatives started shifting to the Republican Party. In Alabama, majority-white districts are now expected to regularly elect Republican candidates to federal, state and local office.

Members of the nine seats on the Supreme Court of Alabama[185] and all ten seats on the state appellate courts are elected to office. Until 1994, no Republicans held any of the court seats. In that general election, the then-incumbent chief justice, Ernest C. Hornsby, refused to leave office after losing the election by approximately 3,000 votes to Republican Perry O. Hooper Sr.[citation needed] Hornsby sued Alabama and defiantly remained in office for nearly a year before finally giving up the seat after losing in court.[citation needed] The Democrats lost the last of the nineteen court seats in August 2011 with the resignation of the last Democrat on the bench.

In the early 21st century, Republicans hold all seven of the statewide elected executive branch offices. Republicans hold six of the eight elected seats on the Alabama State Board of Education. In 2010, Republicans took large majorities of both chambers of the state legislature, giving them control of that body for the first time in 136 years. The last remaining statewide Democrat, who served on the Alabama Public Service Commission was defeated in 2012.[186][187][188]

Only three Republican lieutenant governors have been elected since the end of Reconstruction, when Republicans generally represented Reconstruction government, including the newly emancipated freedmen who had gained the franchise. The three GOP lieutenant governors are Steve Windom (1999–2003), Kay Ivey (2011–2017), and Will Ainsworth (2019–present).

الانتخابات المحلية

Many local offices (county commissioners, boards of education, tax assessors, tax collectors, etc.) in the state are still held by Democrats. Many rural counties have voters who are majority Democrats, resulting in local elections being decided in the Democratic primary. Similarly many metropolitan and suburban counties are majority-Republican and elections are effectively decided in the Republican Primary, although there are exceptions.[189][190]

Alabama's 67 county sheriffs are elected in partisan, at-large races, and Democrats still retain the narrow majority of those posts. The current split is 35 Democrats, 31 Republicans, and one Independent Fayette.[191] However, most of the Democratic sheriffs preside over rural and less populated counties. The majority of Republican sheriffs have been elected in the more urban/suburban and heavily populated counties. اعتبارا من 2015[تحديث], the state of Alabama has one female sheriff, in Morgan County, Alabama, and ten African-American sheriffs.[191]

الانتخابات الفدرالية

The state's two U.S. senators are Republican Richard C. Shelby and Republican Tommy Tuberville. Shelby was originally elected to the Senate as a Democrat in 1986 and re-elected in 1992, but switched parties immediately following the November 1994 general election.

In the U.S. House of Representatives, the state is represented by seven members, six of whom are Republicans: (Bradley Byrne, Mike D. Rogers, Robert Aderholt, Morris J. Brooks, Martha Roby, and Gary Palmer) and one Democrat: Terri Sewell who represents the Black Belt as well as most of the predominantly black portions of Birmingham, Tuscaloosa and Montgomery.

التعليم

التعليم الابتدائي والثانوي

Public primary and secondary education in Alabama is under the purview of the Alabama State Board of Education as well as local oversight by 67 county school boards and 60 city boards of education. Together, 1,496 individual schools provide education for 744,637 elementary and secondary students.[192]

Public school funding is appropriated through the Alabama Legislature through the Education Trust Fund. In FY 2006–2007, Alabama appropriated $3,775,163,578 for primary and secondary education. That represented an increase of $444,736,387 over the previous fiscal year. In 2007, more than 82 percent of schools made adequate yearly progress (AYP) toward student proficiency under the National No Child Left Behind law, using measures determined by the state of Alabama.

While Alabama's public education system has improved in recent decades, it lags behind in achievement compared to other states. According to U.S. Census data (2000), Alabama's high school graduation rate (75%) is the fourth lowest in the U.S. (after Kentucky, Louisiana and Mississippi).[193] The largest educational gains were among people with some college education but without degrees.[194]

Generally prohibited in the West at large, school corporal punishment is not unusual in Alabama, with 27,260 public school students paddled at least one time, according to government data for the 2011–2012 school year.[195][196] The rate of school corporal punishment in Alabama is surpassed by only Mississippi and Arkansas.[196]

الجامعات والكليات

Alabama's programs of higher education include 14 four-year public universities, two-year community colleges, and 17 private, undergraduate and graduate universities. In the state are four medical schools (as of fall 2015) (University of Alabama School of Medicine, University of South Alabama and Alabama College of Osteopathic Medicine and The Edward Via College of Osteopathic Medicine—Auburn Campus), two veterinary colleges (Auburn University and Tuskegee University), a dental school (University of Alabama School of Dentistry), an optometry college (University of Alabama at Birmingham), two pharmacy schools (Auburn University and Samford University), and five law schools (University of Alabama School of Law, Birmingham School of Law, Cumberland School of Law, Miles Law School, and the Thomas Goode Jones School of Law). Public, post-secondary education in Alabama is overseen by the Alabama Commission on Higher Education and the Alabama Department of Postsecondary Education. Colleges and universities in Alabama offer degree programs from two-year associate degrees to a multitude of doctoral level programs.[197]

The largest single campus is the University of Alabama, located in Tuscaloosa, with 37,665 enrolled for fall 2016.[198] Troy University was the largest institution in the state in 2010, with an enrollment of 29,689 students across four Alabama campuses (Troy, Dothan, Montgomery, and Phenix City), as well as sixty learning sites in seventeen other states and eleven other countries. The oldest institutions are the public University of North Alabama in Florence and the Catholic Church-affiliated Spring Hill College in Mobile, both founded in 1830.[199][200]

Accreditation of academic programs is through the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools (SACS) as well as other subject-focused national and international accreditation agencies such as the Association for Biblical Higher Education (ABHE),[201] the Council on Occupational Education (COE),[202] and the Accrediting Council for Independent Colleges and Schools (ACICS).[203]

According to the 2011 U.S. News & World Report, Alabama had three universities ranked in the top 100 Public Schools in America (University of Alabama at 31, Auburn University at 36, and University of Alabama at Birmingham at 73).[204]

According to the 2012 U.S. News & World Report, Alabama had four tier one universities (University of Alabama, Auburn University, University of Alabama at Birmingham and University of Alabama in Huntsville).[205]

الإعلام

Major television network affiliates in Alabama include:

- ABC

- WGWW 40.2 ABC, Anniston

- WBMA 58/WABM 68.2 ABC, Birmingham

- WDHN 18 ABC, Dothan

- WAAY 31 ABC, Huntsville

- WEAR 3 ABC Pensacola, FL/Mobile

- WNCF 32 ABC, Montgomery

- WDBB 17.2 ABC, Tuscaloosa

- CBS

- Fox

- NBC

- PBS/Alabama Public Television

- WBIQ 10 PBS, Birmingham

- WIIQ 41 PBS, Demopolis

- WDIQ 2 PBS, Dozier

- WFIQ 36 PBS, Florence

- WHIQ 25 PBS, Huntsville

- WGIQ 43 PBS, Louisville[206]

- WEIQ 42 PBS, Mobile

- WAIQ 26 PBS, Montgomery

- WCIQ 7 PBS, Mount Cheaha

- The CW

الثقافة

الأدب

الرياضة

Alabama has several professional and semi-professional sports teams, including three minor league baseball teams.

| Club | City | Sport | League | Venue |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AFC Mobile | Mobile | Soccer | Gulf Coast Premier League | Archbishop Lipscomb Athletic Complex |

| Birmingham Bulls | Pelham | Ice Hockey | Southern Professional Hockey League | Pelham Civic Center |

| Birmingham Legion FC | Birmingham | Soccer | USL Championship | BBVA Compass Field |

| Birmingham Barons | Birmingham | Baseball | Southern League | Regions Field |

| Huntsville Havoc | Huntsville | Ice Hockey | Southern Professional Hockey League | Von Braun Center |

| Montgomery Biscuits | Montgomery | Baseball | Southern League | Montgomery Riverwalk Stadium |

| Rocket City Trash Pandas | Madison | Baseball | Southern League | Toyota Field |

| Tennessee Valley Tigers | Huntsville | Football | Independent Women's Football League | Milton Frank Stadium |

- Notes

النقل

الطيران

Major airports with sustained operations in Alabama include Birmingham-Shuttlesworth International Airport (BHM), Huntsville International Airport (HSV), Dothan Regional Airport (DHN), Mobile Regional Airport (MOB), Montgomery Regional Airport (MGM), Northwest Alabama Regional Airport (MSL) and Northeast Alabama Regional Airport (GAD).

السكك الحديدية

For rail transport, Amtrak schedules the Crescent, a daily passenger train, running from New York to New Orleans with station stops at Anniston, Birmingham, and Tuscaloosa.

الطرق

Alabama has six major interstate routes: Interstate 65 (I-65) travels north–south roughly through the middle of the state; I-20/I-59 travel from the central west Mississippi state line to Birmingham, where I-59 continues to the north-east corner of the state and I-20 continues east towards Atlanta; I-85 originates in Montgomery and travels east-northeast to the Georgia state line, providing a main thoroughfare to Atlanta; and I-10 traverses the southernmost portion of the state, traveling from west to east through Mobile. I-22 enters the state from Mississippi and connects Birmingham with Memphis, Tennessee. In addition, there are currently five auxiliary interstate routes in the state: I-165 in Mobile, I-359 in Tuscaloosa, I-459 around Birmingham, I-565 in Decatur and Huntsville, and I-759 in Gadsden. A sixth route, I-685, will be formed when I-85 is rerouted along a new southern bypass of Montgomery. A proposed northern bypass of Birmingham will be designated as I-422. Since a direct connection from I-22 to I-422 will not be possible, I-222 has been proposed, as well.

Several U.S. Highways also pass through the state, such as U.S. Route 11 (US-11), US-29, US-31, US-43, US-45, US-72, US-78, US-80, US-82, US-84, US-90, US-98, US-231, US-278, US-280, US-331, US-411, and US-431.

There are four toll roads in the state: Montgomery Expressway in Montgomery; Northport/Tuscaloosa Western Bypass in Tuscaloosa and Northport; Emerald Mountain Expressway in Wetumpka; and Beach Express in Orange Beach.

الموانيء

Water ports of Alabama, listed from north to south:

| Port name | Location | Connected to |

|---|---|---|

| Port of Florence | Florence/Muscle Shoals, on Pickwick Lake | Tennessee River |

| Port of Decatur | Decatur, on Wheeler Lake | Tennessee River |

| Port of Guntersville | Guntersville, on Lake Guntersville | Tennessee River |

| Port of Birmingham | Birmingham, on Black Warrior River | Tenn-Tom Waterway |

| Port of Tuscaloosa | Tuscaloosa, on Black Warrior River | Tenn-Tom Waterway |

| Port of Montgomery | Montgomery, on Woodruff Lake | Alabama River |

| Port of Mobile | Mobile, on Mobile Bay | Gulf of Mexico |

انظر أيضاً

المصادر

- ^ "Cheehahaw". NGS data sheet. U.S. National Geodetic Survey. Retrieved October 20, 2011.

- ^ أ ب "Elevations and Distances in the United States". United States Geological Survey. 2001. Archived from the original on October 15, 2011. Retrieved October 21, 2011.

- ^ Elevation adjusted to North American Vertical Datum of 1988.

- ^ "Median Annual Household Income". The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. Retrieved December 9, 2016.

- ^ "State of Alabama". The Battle of Gettysburg. Retrieved July 21, 2014.

- ^ "Oxford English Dictionary". www-oed-com. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 30 September 2020.

- ^ Stephens, Challen (October 19, 2015). "A look at the languages spoken in Alabama and the drop in the Spanish speaking population". AL.com. Retrieved September 21, 2016.

- ^ "Alabama Transportation Overview" (PDF). Economic Development Partnership of Alabama. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 13, 2018. Retrieved January 21, 2017.

- ^ "Alabama". QuickFacts. United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on September 10, 2012. Retrieved September 22, 2012.

- ^ Thomason, Michael (2001). Mobile: The New History of Alabama's First City. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press. pp. 2–21. ISBN 978-0-8173-1065-3.

- ^ "Alabama's largest county looks to continue economic development momentum". August 31, 2018.

- ^ أ ب "Alabama Occupational Projections 2008–2018" (PDF). Alabama Department of Industrial Relations. State of Alabama. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 17, 2013. Retrieved September 22, 2012.

- ^ أ ب ت Read, William A. (1984). Indian Place Names in Alabama. University of Alabama Press. ISBN 978-0-8173-0231-3. OCLC 10724679.

- ^ Sylestine, Cora; Hardy, Heather; Montler, Timothy (1993). Dictionary of the Alabama Language. Austin: University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-292-73077-9. OCLC 26590560. Archived from the original on October 24, 2008.

- ^ "Alabama, n. and adj.". OED Online, March 2016. Oxford University Press. (accessed April 22, 2016)

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د "Alabama: The State Name". All About Alabama. Alabama Department of Archives and History. Archived from the original on June 28, 2007. Retrieved August 2, 2007.

- ^ أ ب Wills, Charles A. (1995). A Historical Album of Alabama. The Millbrook Press. ISBN 978-1-56294-591-6. OCLC 32242468.

- ^ Griffith, Lucille (1972). Alabama: A Documentary History to 1900. University of Alabama Press. ISBN 978-0-8173-0371-6. OCLC 17530914.

- ^ and possibly Alabahmu.[citation needed] The use of state names derived from Native American languages is common in the U.S.; an estimated 27 states have names of Native American origin. Weiss, Sonia (1999). The Complete Idiot's Guide to Baby Names. Macmillan USA. ISBN 978-0-02-863367-1. OCLC 222611214.

- ^ أ ب Rogers, William W.; Robert D. Ward; Leah R. Atkins; Wayne Flynt (1994). Alabama: the History of a Deep South State. University of Alabama Press. ISBN 978-0-8173-0712-7. OCLC 28634588.

- ^ أ ب Swanton, John R. (1953). "The Indian Tribes of North America". Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin. 145: 153–174. hdl:2027/mdp.39015005395804. Archived from the original on August 4, 2007. Retrieved August 2, 2007.

- ^ أ ب Swanton, John R. (1937). "Review of Read, Indian Place Names of Alabama". American Speech. 12 (3): 212–215. doi:10.2307/452431. JSTOR 452431.

- ^ William A. Read (1994). "Southeastern Indian Place Names in what is now Alabama" (PDF). Indian Place Names in Alabama. Alabama Department of Archives and History. Retrieved October 3, 2011.

- ^ Bright, William (2004). Native American placenames of the United States. University of Oklahoma Press. pp. 29–559. ISBN 978-0-8061-3576-2.

- ^ "Alabama". The New York Times Almanac 2004. August 11, 2006. Archived from the original on October 16, 2013. Retrieved September 23, 2006.

- ^ Welch, Paul D. (1991). Moundville's Economy. University of Alabama Press. ISBN 978-0-8173-0512-3. OCLC 21330955.

- ^ Walthall, John A. (1990). Prehistoric Indians of the Southeast-Archaeology of Alabama and the Middle South. University of Alabama Press. ISBN 978-0-8173-0552-9. OCLC 26656858.

- ^ Townsend, Richard F. (2004). Hero, Hawk, and Open Hand. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-10601-5. OCLC 56633574.

- ^ F. Kent Reilly; James Garber, eds. (2004). Ancient Objects and Sacred Realms. Foreword by Vincas P. Steponaitis. University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-292-71347-5. OCLC 70335213.

- ^ "Alabama Indian Tribes". Indian Tribal Records. AccessGenealogy.com. 2006. Archived from the original on October 12, 2006. Retrieved September 23, 2006.

- ^ "Alabama State History". theUS50.com. Archived from the original on August 25, 2006. Retrieved September 23, 2006.

- ^ أ ب "Alabama History Timeline". Alabama Department of Archives and History. Retrieved July 27, 2013.

- ^ أ ب Thomason, Michael (2001). Mobile: The New History of Alabama's First City. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press. p. 61. ISBN 978-0-8173-1065-3.

- ^ "Alabama Historical Association Marker Program: Washington County". Archives.state.al.us. Archived from the original on August 22, 2011. Retrieved June 1, 2011.

- ^ Clark, Thomas D.; John D. W. Guice (1989). The Old Southwest 1795–1830: Frontiers in Conflict. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. pp. 44–65, 210–257. ISBN 978-0-8061-2836-8.

- ^ Hamilton, Peter Joseph (1910). Colonial Mobile: An Historical Study of the Alabama-Tombigbee Basin and the Old South West from the Discovery of the Spiritu Sancto in 1519 until the Demolition of Fort Charlotte in 1821. Boston: Hougthon Mifflin. pp. 241–244. OCLC 49073155.

- ^ Cadle, Farris W (1991). Georgia Land Surveying History and Law. Athens, Ga.: University of Georgia Press.

- ^ أ ب Pickett, Albert James (1851). History of Alabama and incidentally of Georgia and Mississippi, from the earliest period. Charleston: Walker and James. pp. 408–428.

- ^ "The Pine Barrens Speculation and Yazoo Land Fraud". About North Georgia. Retrieved July 27, 2013.

- ^ "Old St. Stephens". Encyclopedia of Alabama. Auburn University. Archived from the original on July 26, 2011. Retrieved June 21, 2011.

- ^ "Huntsville". The Encyclopedia of Alabama. Alabama Humanities Foundation. Archived from the original on January 22, 2013. Retrieved January 22, 2013.

- ^ "Old Cahawba, Alabama's first state capital, 1820 to 1826". Old Cahawba: A Cahawba Advisory Committee Project. Retrieved September 22, 2012.

- ^ أ ب LeeAnna Keith (October 13, 2011). "Alabama Fever". Encyclopedia of Alabama. Auburn University. Archived from the original on January 17, 2013. Retrieved September 22, 2012.