مصفوفة

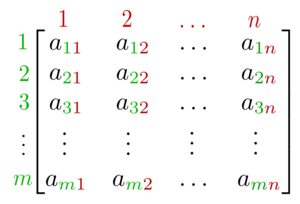

المصفوفة Matrix هي دالة رياضية خطية تحول مجموعة بداية أي إنطلاق (مجال) إلى مجموعة وصول أو نهاية (مدى). مجموعة الإنطلاق و الوصول يمكن أن تكون متكونة من أعداد صحيحة أو عقدية أو أشعة من الأعداد كما يمكن أن تكون هاتين المجموعتان متكونة بدورها من دالات رياضية أو أشعة دالات رياضية. ويمكن أن نرمز للمصفوفة بمعقفين يكتب بينهما عناصر المصفوفة كما هو مبين أسفله:

حيث يمكن أن تكون أعدادا صحيحة أو مركبة كما يمكن أن تكون دالات رياضية.

نظرية المصفوفات هي فرع الرياضيات الذي يركز على دراسة المصفوفات. فعليا يعتبر أحد فروع الجبر الخطي, ثم نمى ليغطي موضوعات ذات علاقة بنظرية المخططات والجبر, والتوافقيات والإحصاء.

مثال على تحويل من مجموعة إنطلاق إلى مجموعة وصول

لنعتبر مثلا الشعاع التالي:

و المصفوفة التالية:

عملية تحويل الشعاع تتم على النحو التالي:

وهكذا نكون قد حولنا شعاعا V ينتمي إلى إلى شعاع X ينتمي إلى ال . أما عامة إذا كانت المصفوفة تحتوي على عدد m من الأسطر و n من الأعمدة فإنها تحول مجموعة الإنطلاق المكونة من أشعة تنتمي إلى ال إلى مجموعة الوصول المتكونة من أشعة تنتمي إلى ال .

كما يمكن إعتبار المصفوفات نوعا خاصا من التنسورات ألا وهي التنسورات من الدرجة الثانية

العمليات الأساسية

There are a number of basic operations that can be applied to modify matrices, called matrix addition, scalar multiplication, transposition, matrix multiplication, row operations, and submatrix.[2]

Addition, scalar multiplication, and transposition

| Operation | Definition | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Addition | The sum A+B of two m-by-n matrices A and B is calculated entrywise:

|

|

| Scalar multiplication | The product cA of a number c (also called a scalar in the parlance of abstract algebra) and a matrix A is computed by multiplying every entry of A by c:

This operation is called scalar multiplication, but its result is not named "scalar product" to avoid confusion, since "scalar product" is sometimes used as a synonym for "inner product". |

|

| Transposition | The transpose of an m-by-n matrix A is the n-by-m matrix AT (also denoted Atr or tA) formed by turning rows into columns and vice versa:

|

Familiar properties of numbers extend to these operations of matrices: for example, addition is commutative, that is, the matrix sum does not depend on the order of the summands: A + B = B + A.[3] The transpose is compatible with addition and scalar multiplication, as expressed by (cA)T = c(AT) and (A + B)T = AT + BT. Finally, (AT)T = A.

ضرب المصفوفات

يتم ضرب مصفوفة في أخرى ولكن بتواجد الشرط الآتي : أن يكون عدد الأعمدة بالمصفوفة الأولى يساوي عدد الصفوف بالمصفوفة الثانية. يتم ضرب المصفوفات كالتالي : الصف الأول بالعمود الأول ثم الصف الثاني بالعمود الثاني .......إلخ،وينتج من ضرب الصف الأول بالعمود الأول العدد الأول بالمصفوفة الناتجة. ونضرب العدد الأول بالصف بالعدد الأول بالعمود.

Multiplication of two matrices is defined if and only if the number of columns of the left matrix is the same as the number of rows of the right matrix. If A is an m-by-n matrix and B is an n-by-p matrix, then their matrix product AB is the m-by-p matrix whose entries are given by dot product of the corresponding row of A and the corresponding column of B:

where 1 ≤ i ≤ m and 1 ≤ j ≤ p.[4] For example, the underlined entry 2340 in the product is calculated as (2 × 1000) + (3 × 100) + (4 × 10) = 2340:

Matrix multiplication satisfies the rules (AB)C = A(BC) (associativity), and (A + B)C = AC + BC as well as C(A + B) = CA + CB (left and right distributivity), whenever the size of the matrices is such that the various products are defined.[5] The product AB may be defined without BA being defined, namely if A and B are m-by-n and n-by-k matrices, respectively, and m ≠ k. Even if both products are defined, they need not be equal, that is, generally

- AB ≠ BA,

that is, matrix multiplication is not commutative, in marked contrast to (rational, real, or complex) numbers whose product is independent of the order of the factors. An example of two matrices not commuting with each other is:

whereas

Besides the ordinary matrix multiplication just described, there exist other less frequently used operations on matrices that can be considered forms of multiplication, such as the Hadamard product and the Kronecker product.[6] They arise in solving matrix equations such as the Sylvester equation.

Row operations

There are three types of row operations:

- row addition, that is adding a row to another.

- row multiplication, that is multiplying all entries of a row by a non-zero constant;

- row switching, that is interchanging two rows of a matrix;

These operations are used in a number of ways, including solving linear equations and finding matrix inverses.

Submatrix

A submatrix of a matrix is obtained by deleting any collection of rows and/or columns.[7][8][9] For example, from the following 3-by-4 matrix, we can construct a 2-by-3 submatrix by removing row 3 and column 2:

The minors and cofactors of a matrix are found by computing the determinant of certain submatrices.[9][10]

A principal submatrix is a square submatrix obtained by removing certain rows and columns. The definition varies from author to author. According to some authors, a principal submatrix is a submatrix in which the set of row indices that remain is the same as the set of column indices that remain.[11][12] Other authors define a principal submatrix as one in which the first k rows and columns, for some number k, are the ones that remain;[13] this type of submatrix has also been called a leading principal submatrix.[14]

المعادلات الخطية

Matrices can be used to compactly write and work with multiple linear equations, that is, systems of linear equations. For example, if A is an m-by-n matrix, x designates a column vector (that is, n×1-matrix) of n variables x1, x2, ..., xn, and b is an m×1-column vector, then the matrix equation

is equivalent to the system of linear equations[15]

Using matrices, this can be solved more compactly than would be possible by writing out all the equations separately. If n = m and the equations are independent, this can be done by writing

where A−1 is the inverse matrix of A. If A has no inverse, solutions if any can be found using its generalized inverse.

التحولات الخطية

Matrices and matrix multiplication reveal their essential features when related to linear transformations, also known as linear maps. A real m-by-n matrix A gives rise to a linear transformation Rn → Rm mapping each vector x in Rn to the (matrix) product Ax, which is a vector in Rm. Conversely, each linear transformation f: Rn → Rm arises from a unique m-by-n matrix A: explicitly, the (i, j)-entry of A is the ith coordinate of f(ej), where ej = (0,...,0,1,0,...,0) is the unit vector with 1 in the jth position and 0 elsewhere. The matrix A is said to represent the linear map f, and A is called the transformation matrix of f.

For example, the 2×2 matrix

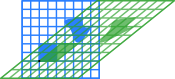

can be viewed as the transform of the unit square into a parallelogram with vertices at (0, 0), (a, b), (a + c, b + d), and (c, d). The parallelogram pictured at the right is obtained by multiplying A with each of the column vectors , and in turn. These vectors define the vertices of the unit square.

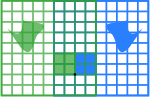

The following table shows a number of 2-by-2 matrices with the associated linear maps of R2. The blue original is mapped to the green grid and shapes. The origin (0,0) is marked with a black point.

| Horizontal shear with m = 1.25. | Reflection through the vertical axis | Squeeze mapping with r = 3/2 | Scaling by a factor of 3/2 | Rotation by π/6 = 30° |

|

|

|

|

|

Under the 1-to-1 correspondence between matrices and linear maps, matrix multiplication corresponds to composition of maps:[16] if a k-by-m matrix B represents another linear map g: Rm → Rk, then the composition g ∘ f is represented by BA since

- (g ∘ f)(x) = g(f(x)) = g(Ax) = B(Ax) = (BA)x.

The last equality follows from the above-mentioned associativity of matrix multiplication.

The rank of a matrix A is the maximum number of linearly independent row vectors of the matrix, which is the same as the maximum number of linearly independent column vectors.[17] Equivalently it is the dimension of the image of the linear map represented by A.[18] The rank–nullity theorem states that the dimension of the kernel of a matrix plus the rank equals the number of columns of the matrix.[19]

المصفوفة المربعة

A square matrix is a matrix with the same number of rows and columns. An n-by-n matrix is known as a square matrix of order n. Any two square matrices of the same order can be added and multiplied. The entries aii form the main diagonal of a square matrix. They lie on the imaginary line that runs from the top left corner to the bottom right corner of the matrix.

الأنواع الرئيسية

الاسم أمثلة فيها n = 3 Diagonal matrix Lower triangular matrix Upper triangular matrix

المصفوفة القطرية والمثلثة

If all entries of A below the main diagonal are zero, A is called an upper triangular matrix. Similarly if all entries of A above the main diagonal are zero, A is called a lower triangular matrix. If all entries outside the main diagonal are zero, A is called a diagonal matrix.

Identity matrix

The identity matrix In of size n is the n-by-n matrix in which all the elements on the main diagonal are equal to 1 and all other elements are equal to 0, for example,

It is a square matrix of order n, and also a special kind of diagonal matrix. It is called an identity matrix because multiplication with it leaves a matrix unchanged:

- AIn = ImA = A for any m-by-n matrix A.

A nonzero scalar multiple of an identity matrix is called a scalar matrix. If the matrix entries come from a field, the scalar matrices form a group, under matrix multiplication, that is isomorphic to the multiplicative group of nonzero elements of the field.

Symmetric or skew-symmetric matrix

A square matrix A that is equal to its transpose, that is, A = AT, is a symmetric matrix. If instead, A is equal to the negative of its transpose, that is, A = −AT, then A is a skew-symmetric matrix. In complex matrices, symmetry is often replaced by the concept of Hermitian matrices, which satisfy A∗ = A, where the star or asterisk denotes the conjugate transpose of the matrix, that is, the transpose of the complex conjugate of A.

By the spectral theorem, real symmetric matrices and complex Hermitian matrices have an eigenbasis; that is, every vector is expressible as a linear combination of eigenvectors. In both cases, all eigenvalues are real.[20] This theorem can be generalized to infinite-dimensional situations related to matrices with infinitely many rows and columns, see below.

Invertible matrix and its inverse

A square matrix A is called invertible or non-singular if there exists a matrix B such that

where In is the n×n identity matrix with 1s on the main diagonal and 0s elsewhere. If B exists, it is unique and is called the inverse matrix of A, denoted A−1.

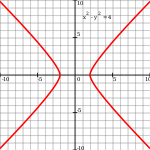

Definite matrix

| Positive definite matrix | Indefinite matrix |

|---|---|

| Q(x, y) = 1/4 x2 + y2 | Q(x, y) = 1/4 x2 − 1/4 y2 |

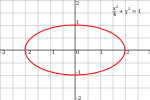

Points such that Q(x,y)=1 (Ellipse). |

Points such that Q(x,y)=1 (Hyperbola). |

A symmetric real matrix A is called positive-definite if the associated quadratic form

A symmetric matrix is positive-definite if and only if all its eigenvalues are positive, that is, the matrix is positive-semidefinite and it is invertible.[25] The table at the right shows two possibilities for 2-by-2 matrices. The eigenvalues of a diagonal matrix are simply the entries along the diagonal,[26] and so in these examples, the eigenvalues can be read directly from the matrices themselves. The first matrix has two eigenvalues that are both positive, while the second has one that is positive and another that is negative.

Allowing as input two different vectors instead yields the bilinear form associated to A:[27]

In the case of complex matrices, the same terminology and results apply, with symmetric matrix, quadratic form, bilinear form, and transpose xT replaced respectively by Hermitian matrix, Hermitian form, sesquilinear form, and conjugate transpose xH.[28]

المصفوفة العمودية Orthogonal

An orthogonal matrix is a square matrix with real entries whose columns and rows are orthogonal unit vectors (that is, orthonormal vectors). Equivalently, a matrix A is orthogonal if its transpose is equal to its inverse:

which entails

where In is the identity matrix of size n.

An orthogonal matrix A is necessarily invertible (with inverse A−1 = AT), unitary (A−1 = A*), and normal (A*A = AA*). The determinant of any orthogonal matrix is either +1 or −1. A special orthogonal matrix is an orthogonal matrix with determinant +1. As a linear transformation, every orthogonal matrix with determinant +1 is a pure rotation without reflection, i.e., the transformation preserves the orientation of the transformed structure, while every orthogonal matrix with determinant -1 reverses the orientation, i.e., is a composition of a pure reflection and a (possibly null) rotation. The identity matrices have determinant 1, and are pure rotations by an angle zero.

The complex analogue of an orthogonal matrix is a unitary matrix.

العمليات الرئيسية

Trace

The trace, tr(A) of a square matrix A is the sum of its diagonal entries. While matrix multiplication is not commutative as mentioned above, the trace of the product of two matrices is independent of the order of the factors:

- tr(AB) = tr(BA).

This is immediate from the definition of matrix multiplication:

It follows that the trace of the product of more than two matrices is independent of cyclic permutations of the matrices, however this does not in general apply for arbitrary permutations (for example, tr(ABC) ≠ tr(BAC), in general). Also, the trace of a matrix is equal to that of its transpose, that is,

- tr(A) = tr(AT).

المحددة

The determinant det(A) or |A| of a square matrix A is a number encoding certain properties of the matrix. A matrix is invertible if and only if its determinant is nonzero. Its absolute value equals the area (in R2) or volume (in R3) of the image of the unit square (or cube), while its sign corresponds to the orientation of the corresponding linear map: the determinant is positive if and only if the orientation is preserved.

The determinant of 2-by-2 matrices is given by

The determinant of 3-by-3 matrices involves 6 terms (rule of Sarrus). The more lengthy Leibniz formula generalises these two formulae to all dimensions.[29]

The determinant of a product of square matrices equals the product of their determinants:

- det(AB) = det(A) · det(B).[30]

Adding a multiple of any row to another row, or a multiple of any column to another column, does not change the determinant. Interchanging two rows or two columns affects the determinant by multiplying it by −1.[31] Using these operations, any matrix can be transformed to a lower (or upper) triangular matrix, and for such matrices the determinant equals the product of the entries on the main diagonal; this provides a method to calculate the determinant of any matrix. Finally, the Laplace expansion expresses the determinant in terms of minors, that is, determinants of smaller matrices.[32] This expansion can be used for a recursive definition of determinants (taking as starting case the determinant of a 1-by-1 matrix, which is its unique entry, or even the determinant of a 0-by-0 matrix, which is 1), that can be seen to be equivalent to the Leibniz formula. Determinants can be used to solve linear systems using Cramer's rule, where the division of the determinants of two related square matrices equates to the value of each of the system's variables.[33]

Eigenvalues and eigenvectors

A number λ and a non-zero vector v satisfying

- Av = λv

are called an eigenvalue and an eigenvector of A, respectively.[34][35] The number λ is an eigenvalue of an n×n-matrix A if and only if A−λIn is not invertible, which is equivalent to

The polynomial pA in an indeterminate X given by evaluation the determinant det(XIn−A) is called the characteristic polynomial of A. It is a monic polynomial of degree n. Therefore the polynomial equation pA(λ) = 0 has at most n different solutions, that is, eigenvalues of the matrix.[37] They may be complex even if the entries of A are real. According to the Cayley–Hamilton theorem, pA(A) = 0, that is, the result of substituting the matrix itself into its own characteristic polynomial yields the zero matrix.

نواحي حاسوبية

Matrix calculations can be often performed with different techniques. Many problems can be solved by both direct algorithms and iterative approaches. For example, the eigenvectors of a square matrix can be obtained by finding a sequence of vectors xn converging to an eigenvector when n tends to infinity.[38]

To choose the most appropriate algorithm for each specific problem, it is important to determine both the effectiveness and precision of all the available algorithms. The domain studying these matters is called numerical linear algebra.[39] As with other numerical situations, two main aspects are the complexity of algorithms and their numerical stability.

Determining the complexity of an algorithm means finding upper bounds or estimates of how many elementary operations such as additions and multiplications of scalars are necessary to perform some algorithm, for example, multiplication of matrices. Calculating the matrix product of two n-by-n matrices using the definition given above needs n3 multiplications, since for any of the n2 entries of the product, n multiplications are necessary. The Strassen algorithm outperforms this "naive" algorithm; it needs only n2.807 multiplications.[40] Theoretically faster but impractical matrix multiplication algorithms have been developed,[41] as have speedups to this problem using parallel algorithms or distributed computation systems such as MapReduce.[42]

In many practical situations, additional information about the matrices involved is known. An important case concerns sparse matrices, that is, matrices whose entries are mostly zero. There are specifically adapted algorithms for, say, solving linear systems Ax = b for sparse matrices A, such as the conjugate gradient method.[43]

An algorithm is, roughly speaking, numerically stable if little deviations in the input values do not lead to big deviations in the result. For example, one can calculate the inverse of a matrix by computing its adjugate matrix:

التفكيك

There are several methods to render matrices into a more easily accessible form. They are generally referred to as matrix decomposition or matrix factorization techniques. These techniques are of interest because they can make computations easier.

The LU decomposition factors matrices as a product of lower (L) and an upper triangular matrices (U).[45] Once this decomposition is calculated, linear systems can be solved more efficiently by a simple technique called forward and back substitution. Likewise, inverses of triangular matrices are algorithmically easier to calculate. The Gaussian elimination is a similar algorithm; it transforms any matrix to row echelon form.[46] Both methods proceed by multiplying the matrix by suitable elementary matrices, which correspond to permuting rows or columns and adding multiples of one row to another row. Singular value decomposition (SVD) expresses any matrix A as a product UDV∗, where U and V are unitary matrices and D is a diagonal matrix.[47]

The eigendecomposition or diagonalization expresses A as a product VDV−1, where D is a diagonal matrix and V is a suitable invertible matrix.[48] If A can be written in this form, it is called diagonalizable. More generally, and applicable to all matrices, the Jordan decomposition transforms a matrix into Jordan normal form, that is to say matrices whose only nonzero entries are the eigenvalues λ1 to λn of A, placed on the main diagonal and possibly entries equal to one directly above the main diagonal, as shown at the right.[49] Given the eigendecomposition, the nth power of A (that is, n-fold iterated matrix multiplication) can be calculated via

Abstract algebraic aspects and generalizations

Matrices can be generalized in different ways. Abstract algebra uses matrices with entries in more general fields or even rings, while linear algebra codifies properties of matrices in the notion of linear maps. It is possible to consider matrices with infinitely many columns and rows. Another extension is tensors, which can be seen as higher-dimensional arrays of numbers, as opposed to vectors, which can often be realized as sequences of numbers, while matrices are rectangular or two-dimensional arrays of numbers.[52] Matrices, subject to certain requirements tend to form groups known as matrix groups.[53] Similarly under certain conditions matrices form rings known as matrix rings.[54] Though the product of matrices is not in general commutative, certain matrices form fields sometimes called matrix fields.[55] (However the term "matrix field" is ambiguous, also referring to certain forms of physical fields that continuously map points of some space to matrices.[56]) In general, matrices over any ring and their multiplication can be represented as the arrows and composition of arrows in a category, the category of matrices over that ring. The objects of this category are natural numbers, representing the dimensions of the matrices.[57]

Matrices with entries in a field or ring

This article focuses on matrices whose entries are real or complex numbers. However, matrices can be considered with much more general types of entries than real or complex numbers. As a first step of generalization, any field, that is, a set where addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division operations are defined and well-behaved, may be used instead of or , for example rational numbers or finite fields. For example, coding theory makes use of matrices over finite fields.[58] Wherever eigenvalues are considered, as these are roots of a polynomial, they may exist only in a larger field than that of the entries of the matrix. For instance, they may be complex in the case of a matrix with real entries. The possibility to reinterpret the entries of a matrix as elements of a larger field (for example, to view a real matrix as a complex matrix whose entries happen to be all real) then allows considering each square matrix to possess a full set of eigenvalues.[59] Alternatively one can consider only matrices with entries in an algebraically closed field, such as from the outset.[60]

Matrices whose entries are polynomials,[61] and more generally, matrices with entries in a ring R are widely used in mathematics.[62] Rings are a more general notion than fields in that a division operation need not exist. The very same addition and multiplication operations of matrices extend to this setting, too. The set M(n, R) (also denoted Mn(R)[63]) of all square n-by-n matrices over R is a ring called matrix ring, isomorphic to the endomorphism ring of the left R-module Rn.[64] If the ring R is commutative, that is, its multiplication is commutative, then the ring M(n, R) is also an associative algebra over R. The determinant of square matrices over a commutative ring R can still be defined using the Leibniz formula; such a matrix is invertible if and only if its determinant is invertible in R, generalizing the situation over a field F, where every nonzero element is invertible.[65] Matrices over superrings are called supermatrices.[66]

Matrices do not always have all their entries in the same ring – or even in any ring at all. One special but common case is block matrices, which may be considered as matrices whose entries themselves are matrices. The entries need not be square matrices, and thus need not be members of any ring; but in order to multiply them, their sizes must fulfill certain conditions: each pair of submatrices that are multiplied in forming the overall product must have compatible sizes.[67]

Relationship to linear maps

Linear maps are equivalent to m-by-n matrices, as described above. More generally, any linear map f : V → W between finite-dimensional vector spaces can be described by a matrix A = (aij), after choosing bases v1, ..., vn of V, and w1, ..., wm of W (so n is the dimension of V and m is the dimension of W), which is such that

These properties can be restated more naturally: the category of matrices with entries in a field with multiplication as composition is equivalent to the category of finite-dimensional vector spaces and linear maps over this field.[70]

More generally, the set of قالب:Times matrices can be used to represent the R-linear maps between the free modules Rm and Rn for an arbitrary ring R with unity. When n = m composition of these maps is possible, and this gives rise to the matrix ring of قالب:Times matrices representing the endomorphism ring of Rn.[71]

Matrix groups

A group is a mathematical structure consisting of a set of objects together with a binary operation, that is, an operation combining any two objects to a third, subject to certain requirements.[72] A group in which the objects are invertible matrices and the group operation is matrix multiplication is called a matrix group of degree .[73] Every such matrix group is a subgroup of (that is, a smaller group contained within) the group of all invertible matrices, the general linear group of degree .[74]

Any property of square matrices that is preserved under matrix products and inverses can be used to define a matrix group. For example, the set of all matrices whose determinant is 1 form a group called the special linear group of degree .[75] The set of orthogonal matrices, determined by the condition

Every finite group is isomorphic to a matrix group, as one can see by considering the regular representation of the symmetric group.[78] General groups can be studied using matrix groups, which are comparatively well understood, using representation theory.[79]

المصفوفات اللامحدودة

It is also possible to consider matrices with infinitely many rows and columns.[80] The basic operations introduced above are defined the same way in this case. Matrix multiplication, however, and all operations stemming therefrom are only meaningful when restricted to certain matrices, since the sum featuring in the above definition of the matrix product will contain an infinity of summands.[81] An easy way to circumvent this issue is to restrict to finitary matrices all of whose rows (or columns) contain only finitely many nonzero terms.[82] As in the finite case (see above), where matrices describe linear maps, infinite matrices can be used to describe operators on Hilbert spaces, where convergence and continuity questions arise. However, the explicit point of view of matrices tends to obfuscate the matter,[83] and the abstract and more powerful tools of functional analysis are used instead, by relating matrices to linear maps (as in the finite case above), but imposing additional convergence and continuity constraints.

المصفوفة الفارغة

An empty matrix is a matrix in which the number of rows or columns (or both) is zero.[84][85] Empty matrices can be a useful base case for certain recursive constructions,[86] and can help to deal with maps involving the zero vector space.[87] For example, if A is a قالب:Times matrix and B is a قالب:Times matrix, then AB is the قالب:Times zero matrix corresponding to the null map from a 3-dimensional space V to itself, while BA is a قالب:Times matrix. There is no common notation for empty matrices, but most computer algebra systems allow creating and computing with them.[88] The determinant of the قالب:Times matrix is conventionally defined to be 1, consistent with the empty product occurring in the Leibniz formula for the determinant.[89] This value is also needed for consistency with the قالب:Times case of the Desnanot–Jacobi identity relating determinants to the determinants of smaller matrices.[90]

Matrices with entries in a semiring

A semiring is similar to a ring, but elements need not have additive inverses, therefore one cannot do subtraction freely there. The definition of addition and multiplication of matrices with entries in a ring applies to matrices with entries in a semiring without modification. Matrices of fixed size with entries in a semiring form a commutative monoid under addition.[91] Square matrices of fixed size with entries in a semiring form a semiring under addition and multiplication.[91]

The determinant of an قالب:Times square matrix with entries in a commutative semiring cannot be defined in general because the definition would involve additive inverses of semiring elements. What plays its role instead is the pair of positive and negative determinants

where the sums are taken over even permutations and odd permutations, respectively.[92][93]

Matrices with entries in a category

Matrices and their multiplication can be defined with entries objects of a category equipped with a "tensor product" similar to multiplication in a ring, having coproducts similar to addition in a ring, in that the former is distributive over the latter.[94] However, the multiplication thus defined may be only associative in a sense weaker than usual. These are part of a bigger structure called the bicategory of matrices. The complete description of the above summary for interested readers follows.

Let be a monoidal category satisfying the following two conditions:

- All (small) coproducts exist; in particular, let be an initial object.

- The functor is distributive over coproducts; i.e., for all object and a family of objects in , the canonical -morphisms are isomorphisms. In particular, the canonical morphisms and are isomorphisms.

Then, the bicategory of -matrices is as follows:[94]

- The objects are the sets.

- A 1-morphism is a map ; this is just a matrix over .

- The composition of 1-morphisms and , which can be understood as matrix multiplication, is

- The identity 1-morphism on is

- The composition of 1-morphisms and , which can be understood as matrix multiplication, is

- A 2-morphism between 1-morphisms is a family of -morphisms . The definition of vertical and horizontal composition of 2-morphisms is natural: the vertical composition is componentwise composition of -morphisms; the horizontal composition is that derived from the functoriality of and the universal property of coproducts.

In general, the bicategory of matrices need not be a strict 2-category. For example, the composition of 1-morphisms may not be associative in the usual strict sense, but only up to coherent isomorphism.

التطبيقات

There are numerous applications of matrices, both in mathematics and other sciences. Some of them merely take advantage of the compact representation of a set of numbers in a matrix. For example, Text mining and automated thesaurus compilation makes use of document-term matrices such as tf-idf to track frequencies of certain words in several documents.[95]

Complex numbers can be represented by particular real 2-by-2 matrices via

In game theory and economics, the payoff matrix encodes the payoff for two players, depending on which out of a given (finite) set of strategies the players choose.[98] The expected outcome of the game, when both players play mixed strategies, is obtained by multiplying this matrix on both sides by vectors representing the strategies.[99] The minimax theorem central to game theory is closely related to the duality theory of linear programs, which are often formulated in terms of matrix-vector products.[100]

Early encryption techniques such as the Hill cipher also used matrices. However, due to the linear nature of matrices, these codes are comparatively easy to break.[101] Computer graphics uses matrices to represent objects; to calculate transformations of objects using affine rotation matrices to accomplish tasks such as projecting a three-dimensional object onto a two-dimensional screen, corresponding to a theoretical camera observation; and to apply image convolutions such as sharpening, blurring, edge detection, and more.[102] Matrices over a polynomial ring are important in the study of control theory.[103]

Chemistry makes use of matrices in various ways, particularly since the use of quantum theory to discuss molecular bonding and spectroscopy. Examples are the overlap matrix and the Fock matrix used in solving the Roothaan equations to obtain the molecular orbitals of the Hartree–Fock method.[104]

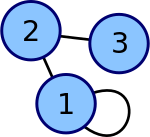

نظرية المخططات

The adjacency matrix of a finite graph is a basic notion of graph theory.[105] It records which vertices of the graph are connected by an edge. Matrices containing just two different values (1 and 0 meaning for example "yes" and "no", respectively) are called logical matrices. The distance (or cost) matrix contains information about the distances of the edges.[106] These concepts can be applied to websites connected by hyperlinks,[107] or cities connected by roads etc., in which case (unless the connection network is extremely dense) the matrices tend to be sparse, that is, contain few nonzero entries. Therefore, specifically tailored matrix algorithms can be used in network theory.[108]

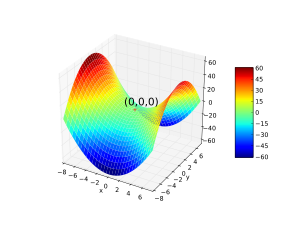

التحليل والهندسة

The Hessian matrix of a differentiable function consists of the second derivatives of ƒ concerning the several coordinate directions, that is,[109]

It encodes information about the local growth behavior of the function: given a critical point x = (x1, ..., xn), that is, a point where the first partial derivatives of f vanish, the function has a local minimum if the Hessian matrix is positive definite. Quadratic programming can be used to find global minima or maxima of quadratic functions closely related to the ones attached to matrices (see above).[110]

Another matrix frequently used in geometrical situations is the Jacobi matrix of a differentiable map . If f1, ..., fm denote the components of f, then the Jacobi matrix is defined as[111]

Partial differential equations can be classified by considering the matrix of coefficients of the highest-order differential operators of the equation. For elliptic partial differential equations this matrix is positive definite, which has a decisive influence on the set of possible solutions of the equation in question.[113]

The finite element method is an important numerical method to solve partial differential equations, widely applied in simulating complex physical systems. It attempts to approximate the solution to some equation by piecewise linear functions, where the pieces are chosen concerning a sufficiently fine grid, which in turn can be recast as a matrix equation.[114]

نظرية الاحتمالات والإحصاء

Stochastic matrices are square matrices whose rows are probability vectors, that is, whose entries are non-negative and sum up to one. Stochastic matrices are used to define Markov chains with finitely many states.[115] A row of the stochastic matrix gives the probability distribution for the next position of some particle currently in the state that corresponds to the row. Properties of the Markov chain—like absorbing states, that is, states that any particle attains eventually—can be read off the eigenvectors of the transition matrices.[116]

Statistics also makes use of matrices in many different forms.[117] Descriptive statistics is concerned with describing data sets, which can often be represented as data matrices, which may then be subjected to dimensionality reduction techniques. The covariance matrix encodes the mutual variance of several random variables.[118] Another technique using matrices are linear least squares, a method that approximates a finite set of pairs (x1, y1), (x2, y2), ..., (xN, yN), by a linear function

Random matrices are matrices whose entries are random numbers, subject to suitable probability distributions, such as matrix normal distribution. Beyond probability theory, they are applied in domains ranging from number theory to physics.[120][121]

ميكانيكا الكم وفيزياء الجسيمات

The first model of quantum mechanics (Heisenberg, 1925) used infinite-dimensional matrices to define the operators that took over the role of variables like position, momentum and energy from classical physics.[122] (This is sometimes referred to as matrix mechanics.[123]) Matrices, both finite and infinite-dimensional, have since been employed for many purposes in quantum mechanics. One particular example is the density matrix, a tool used in calculating the probabilities of the outcomes of measurements performed on physical systems.[124][125]

Linear transformations and the associated symmetries play a key role in modern physics. For example, elementary particles in quantum field theory are classified as representations of the Lorentz group of special relativity and, more specifically, by their behavior under the spin group. Concrete representations involving the Pauli matrices and more general gamma matrices are an integral part of the physical description of fermions, which behave as spinors.[126] For the three lightest quarks, there is a group-theoretical representation involving the special unitary group SU(3); for their calculations, physicists use a convenient matrix representation known as the Gell-Mann matrices, which are also used for the SU(3) gauge group that forms the basis of the modern description of strong nuclear interactions, quantum chromodynamics. The Cabibbo–Kobayashi–Maskawa matrix, in turn, expresses the fact that the basic quark states that are important for weak interactions are not the same as, but linearly related to the basic quark states that define particles with specific and distinct masses.[127]

Another matrix serves as a key tool for describing the scattering experiments that form the cornerstone of experimental particle physics: Collision reactions such as occur in particle accelerators, where non-interacting particles head towards each other and collide in a small interaction zone, with a new set of non-interacting particles as the result, can be described as the scalar product of outgoing particle states and a linear combination of ingoing particle states. The linear combination is given by a matrix known as the S-matrix, which encodes all information about the possible interactions between particles.[128]

Normal modes

A general application of matrices in physics is the description of linearly coupled harmonic systems. The equations of motion of such systems can be described in matrix form, with a mass matrix multiplying a generalized velocity to give the kinetic term, and a force matrix multiplying a displacement vector to characterize the interactions. The best way to obtain solutions is to determine the system's eigenvectors, its normal modes, by diagonalizing the matrix equation. Techniques like this are crucial when it comes to the internal dynamics of molecules: the internal vibrations of systems consisting of mutually bound component atoms.[129] They are also needed for describing mechanical vibrations, and oscillations in electrical circuits.[130]

البصريات الهندسية

Geometrical optics provides further matrix applications. In this approximative theory, the wave nature of light is neglected. The result is a model in which light rays are indeed geometrical rays. If the deflection of light rays by optical elements is small, the action of a lens or reflective element on a given light ray can be expressed as multiplication of a two-component vector with a two-by-two matrix called ray transfer matrix analysis: the vector's components are the light ray's slope and its distance from the optical axis, while the matrix encodes the properties of the optical element. There are two kinds of matrices, viz. a refraction matrix describing the refraction at a lens surface, and a translation matrix, describing the translation of the plane of reference to the next refracting surface, where another refraction matrix applies. The optical system, consisting of a combination of lenses and reflective elements, is simply described by the matrix resulting from the product of the components' matrices.[131]

The Jones calculus models the polarization of a light source as a vector, and the effects of optical filters on this polarization vector as a matrix.[132]

الإلكترونيات

Electronic circuits that are composed of linear components (such as resistors, inductors and capacitors) obey Kirchhoff's circuit laws, which leads to a system of linear equations, which can be described with a matrix equation that relates the source currents and voltages to the resultant currents and voltages at each point in the circuit, and where the matrix entries are determined by the circuit.[133]

التاريخ

Matrices have a long history of application in solving linear equations but they were known as arrays until the 1800s. The Chinese text The Nine Chapters on the Mathematical Art written in the 10th–2nd century BCE is the first example of the use of array methods to solve simultaneous equations,[134] including the concept of determinants. In 1545 Italian mathematician Gerolamo Cardano introduced the method to Europe when he published Ars Magna.[135] The Japanese mathematician Seki used the same array methods to solve simultaneous equations in 1683.[136] The Dutch mathematician Jan de Witt represented transformations using arrays in his 1659 book Elements of Curves (1659).[137] Between 1700 and 1710 Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz publicized the use of arrays for recording information or solutions and experimented with over 50 different systems of arrays.[135] Cramer presented his rule in 1750.[138][139]

This use of the term matrix in mathematics (an English word for "womb" in the 19th century, from Latin, as well as a jargon word in printing, in biology and in geology[140]) was coined by James Joseph Sylvester in 1850,[141] who understood a matrix as an object giving rise to several determinants today called minors, that is to say, determinants of smaller matrices that derive from the original one by removing columns and rows. In an 1851 paper, Sylvester explains:[142]

I have in previous papers defined a "Matrix" as a rectangular array of terms, out of which different systems of determinants may be engendered from the womb of a common parent.

Arthur Cayley published a treatise on geometric transformations using matrices that were not rotated versions of the coefficients being investigated as had previously been done. Instead, he defined operations such as addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division as transformations of those matrices and showed the associative and distributive properties held. Cayley investigated and demonstrated the non-commutative property of matrix multiplication as well as the commutative property of matrix addition.[135] Early matrix theory had limited the use of arrays almost exclusively to determinants and Cayley's abstract matrix operations were revolutionary. He was instrumental in proposing a matrix concept independent of equation systems. In 1858, Cayley published his A memoir on the theory of matrices[143][144] in which he proposed and demonstrated the Cayley–Hamilton theorem.[135]

The English mathematician Cuthbert Edmund Cullis was the first to use modern bracket notation for matrices in 1913 and he simultaneously demonstrated the first significant use of the notation A = [ai,j] to represent a matrix where ai,j refers to the ith row and the jth column.[135]

The modern study of determinants sprang from several sources.[145] Number-theoretical problems led Gauss to relate coefficients of quadratic forms, that is, expressions such as x2 + xy − 2y2, and linear maps in three dimensions to matrices. Eisenstein further developed these notions, including the remark that, in modern parlance, matrix products are non-commutative. Cauchy was the first to prove general statements about determinants, using as the definition of the determinant of a matrix A = [ai,j] the following: replace the powers ajk by aj,k in the polynomial

Many theorems were first established for small matrices only, for example, the Cayley–Hamilton theorem was proved for قالب:Times matrices by Cayley in the aforementioned memoir, and by Hamilton for قالب:Times matrices. Frobenius, working on bilinear forms, generalized the theorem to all dimensions (1898). Also at the end of the 19th century, the Gauss–Jordan elimination (generalizing a special case now known as Gauss elimination) was established by Wilhelm Jordan. In the early 20th century, matrices attained a central role in linear algebra,[150] partially due to their use in the classification of the hypercomplex number systems of the previous century.[151]

The inception of matrix mechanics by Heisenberg, Born and Jordan led to studying matrices with infinitely many rows and columns.[152] Later, von Neumann carried out the mathematical formulation of quantum mechanics, by further developing functional analytic notions such as linear operators on Hilbert spaces, which, very roughly speaking, correspond to Euclidean space, but with an infinity of independent directions.[153]

استخدامات تاريخية أخرى لكلمة "مصفوفة matrix" في الرياضيات

The word has been used in unusual ways by at least two authors of historical importance.

Bertrand Russell and Alfred North Whitehead in their Principia Mathematica (1910–1913) use the word "matrix" in the context of their axiom of reducibility. They proposed this axiom as a means to reduce any function to one of lower type, successively, so that at the "bottom" (0 order) the function is identical to its extension:[154]

Let us give the name of matrix to any function, of however many variables, that does not involve any apparent variables. Then, any possible function other than a matrix derives from a matrix using generalization, that is, by considering the proposition that the function in question is true with all possible values or with some value of one of the arguments, the other argument or arguments remaining undetermined.

For example, a function Φ(x, y) of two variables x and y can be reduced to a collection of functions of a single variable, such as y, by "considering" the function for all possible values of "individuals" ai substituted in place of a variable x. And then the resulting collection of functions of the single variable y, that is, ∀ai: Φ(ai, y), can be reduced to a "matrix" of values by "considering" the function for all possible values of "individuals" bi substituted in place of variable y:

Alfred Tarski in his 1941 Introduction to Logic used the word "matrix" synonymously with the notion of truth table as used in mathematical logic.[155]

انظر أيضاً

الهامش

- ^ "How to organize, add and multiply matrices - Bill Shillito". TED ED. Retrieved April 6, 2013.

- ^ Brown 1991, Definition I.2.1 (addition), Definition I.2.4 (scalar multiplication), and Definition I.2.33 (transpose)

- ^ Brown 1991, Theorem I.2.6

- ^ Brown 1991, Definition I.2.20

- ^ Brown 1991, Theorem I.2.24

- ^ Horn & Johnson 1985, Ch. 4 and 5

- ^ Bronson (1970, p. 16)

- ^ Kreyszig (1972, p. 220)

- ^ أ ب Protter & Morrey (1970, p. 869)

- ^ Kreyszig (1972, pp. 241,244)

- ^ Schneider, Hans; Barker, George Phillip (2012), Matrices and Linear Algebra, Dover Books on Mathematics, Courier Dover Corporation, p. 251, ISBN 9780486139302, https://books.google.com/books?id=9vjBAgAAQBAJ&pg=PA251.

- ^ Perlis, Sam (1991), Theory of Matrices, Dover books on advanced mathematics, Courier Dover Corporation, p. 103, ISBN 9780486668109, https://books.google.com/books?id=5_sxtcnvLhoC&pg=PA103.

- ^ Anton, Howard (2010), Elementary Linear Algebra (10th ed.), John Wiley & Sons, p. 414, ISBN 9780470458211, https://books.google.com/books?id=YmcQJoFyZ5gC&pg=PA414.

- ^ Horn, Roger A.; Johnson, Charles R. (2012), Matrix Analysis (2nd ed.), Cambridge University Press, p. 17, ISBN 9780521839402, https://books.google.com/books?id=5I5AYeeh0JUC&pg=PA17.

- ^ Brown 1991, I.2.21 and 22

- ^ Greub 1975, Section III.2

- ^ Brown 1991, Definition II.3.3

- ^ Greub 1975, Section III.1

- ^ Brown 1991, Theorem II.3.22

- ^ Horn & Johnson 1985, Theorem 2.5.6

- ^ Brown 1991, Definition I.2.28

- ^ Brown 1991, Definition I.5.13

- ^ Horn & Johnson (1985), Chapter 7.

- ^ Anton (2010), Thm. 7.3.2.

- ^ Horn & Johnson (1985), Theorem 7.2.1.

- ^ Boas (2005), p. 150.

- ^ Horn & Johnson (1985), p. 169, Example 4.0.6.

- ^ Lang (1986), Appendix. Complex numbers.

- ^ Brown 1991, Definition III.2.1

- ^ Brown 1991, Theorem III.2.12

- ^ Brown 1991, Corollary III.2.16

- ^ Mirsky 1990, Theorem 1.4.1

- ^ Brown 1991, Theorem III.3.18

- ^ Eigen means "own" in German and in Dutch.

- ^ Brown 1991, Definition III.4.1

- ^ Brown 1991, Definition III.4.9

- ^ Brown 1991, Corollary III.4.10

- ^ Householder (1975), Ch. 7.

- ^ Bau III & Trefethen (1997).

- ^ Golub & Van Loan (1996), Algorithm 1.3.1.

- ^ Vassilevska Williams et al. (2024).

- ^ Misra, Bhattacharya & Ghosh (2022).

- ^ Golub & Van Loan (1996), Chapters 9 and 10, esp. section 10.2.

- ^ Golub & Van Loan (1996), Chapter 2.3.

- ^ Press et al. (1992).

- ^ Stoer & Bulirsch (2002), Section 4.1.

- ^ Gbur (2011), pp. 146–153.

- ^ Horn & Johnson (1985), Theorem 2.5.4.

- ^ Horn & Johnson (1985), Ch. 3.1, 3.2.

- ^ Arnold (1992), Sections 14.5, 7, 8.

- ^ Bronson (1989), Ch. 15.

- ^ Coburn (1955), Ch. V.

- ^ Tapp (2016).

- ^ Lam (1999), pp. 461–470, Chapter 7, §17 Matrix Rings, §17A Characterization and Examples.

- ^ Hachenberger & Jungnickel (2020), p. 302, Definition 7.2.1.

- ^ Ydri (2016).

- ^ Riehl (2016), pp. 4-6.

- ^ Roth (2006), p. 27.

- ^ Chahal (2018), pp. 115–116.

- ^ Meckes & Meckes (2018), pp. 360–361.

- ^ Edwards (2004), p. 80.

- ^ Lang (2002), Chapter XIII.

- ^ Pop & Furdui (2017).

- ^ Lang (2002), p. 643, XVII.1.

- ^ Lang (2002), Proposition XIII.4.16.

- ^ Reichl (2004), Section L.2.

- ^ Jeffrey (2010), pp. 54ff, 3.7 Partitioning of matrices.

- ^ Greub (1975), Section III.3.

- ^ Greub (1975), Section III.3.13.

- ^ Perrone (2024), pp. 99–100.

- ^ Hungerford (1980), pp. 328–335, VII.1: Matrices and maps.

- ^ Horn & Johnson (1985), p. 69.

- ^ Baker (2003), Def. 1.30.

- ^ Cameron (2014).

- ^ Baker (2003), Theorem 1.2.

- ^ Artin (1991), Chapter 4.5.

- ^ Serre (2007), p. 20.

- ^ Rowen (2008), p. 198, Example 19.2.

- ^ See any reference in representation theory or group representation.

- ^ See the item "Matrix" in Itô 1987.

- ^ Boos (2000), pp. 34–39, 2.2 Dealing with infinite matrices.

- ^ Grillet (2007), p. 334.

- ^ "Not much of matrix theory carries over to infinite-dimensional spaces, and what does is not so useful, but it sometimes helps." Halmos 1982, p. 23, Chapter 5.

- ^ "Empty Matrix: A matrix is empty if either its row or column dimension is zero", Glossary Archived 2009-04-29 at the Wayback Machine, O-Matrix v6 User Guide

- ^ "A matrix having at least one dimension equal to zero is called an empty matrix", MATLAB Data Structures Archived 2009-12-28 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Coleman & Van Loan (1988), p. 213.

- ^ Hazewinkel & Gubareni (2017), p. 151.

- ^ The notation of empty matrix is used differently from some sources like Bernstein (2009), p. 90 use , resembling the zero matrix; Hazewinkel & Gubareni (2017), p. 151 use .

- ^ West (2020), p. 750.

- ^ أ ب Farid, Khan & Wang (2013), 2087.

- ^ Reutenauer & Straubing (1984), 351.

- ^ Ghosh (1996), 222.

- ^ أ ب Carboni, Kasangian & Walters (1987), 137.

- ^ Manning & Schütze (1999), Section 15.3.4.

- ^ Ward (1997), Ch. 2.8.

- ^ Abłamowicz (2000), p. 436.

- ^ Fudenberg & Tirole (1983), Section 1.1.1.

- ^ McHugh (2025), p. 390, 11.2.3 The expected payoff as a vector–matrix–vector product.

- ^ Matoušek & Gärtner (2007), pp. 136–137.

- ^ Stinson (2005), Ch. 1.1.5 and 1.2.4.

- ^ ISRD Group (2005), Ch. 7.

- ^ Bhaya & Kaszkurewicz (2006), p. 230.

- ^ Jensen (1999), p. 65–69.

- ^ Godsil & Royle (2004), Ch. 8.1.

- ^ Punnen & Gutin (2002).

- ^ Zhang, Yu & Hou (2006), p. 7.

- ^ Scott & Tůma (2023).

- ^ Lang (1987), Ch. XVI.6.

- ^ Nocedal & Wright (2006), Ch. 16.

- ^ Lang (1987), Ch. XVI.1.

- ^ Lang 1987, Ch. XVI.5. For a more advanced, and more general statement see Lang 1969, Ch. VI.2.

- ^ Gilbarg & Trudinger (2001).

- ^ Šolin 2005, Ch. 2.5. See also stiffness method.

- ^ Latouche & Ramaswami (1999).

- ^ Mehata & Srinivasan (1978), Ch. 2.8.

- ^ Healy, Michael (1986), Matrices for Statistics, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-850702-4

- ^ Krzanowski (1988), p. 60, Ch. 2.2.

- ^ Krzanowski (1988), Ch. 4.1.

- ^ Conrey 2007

- ^ Zabrodin, Brézin & Kazakov et al. 2006

- ^ Schiff (1968), Ch. 6.

- ^ Peres (1993), p. 20.

- ^ Bohm (2001), sections I.8, II.4, and II.8.

- ^ Peres (1993), p. 73.

- ^ Itzykson & Zuber (1980), Ch. 2.

- ^ Burgess & Moore (2007), section 1.6.3. (SU(3)), section 2.4.3.2. (Kobayashi–Maskawa matrix).

- ^ Weinberg (1995), Ch. 3.

- ^ Wherrett (1987), part II.

- ^ Riley, Hobson & Bence (1997), 7.17.

- ^ Guenther (1990), Ch. 5.

- ^ Han, Kim & Noz (1997).

- ^ Suresh Kumar (2009), pp. 747–749.

- ^ Shen, Crossley & Lun 1999 cited by Bretscher 2005, p. 1

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج Dossey (2002), pp. 564–565.

- ^ Needham, Joseph; Wang Ling (1959). Science and Civilisation in China. Vol. III. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 117. ISBN 978-0-521-05801-8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ignored ISBN errors (link) - ^ Dossey (2002), p. 564.

- ^ Cramer (1750).

- ^ Kosinski (2001).

- ^ Murray, James; Bradley, Henry, eds. (1908), Matrix, 6, pt. 2 (M–N), Oxford: Clarendon Press, p. 238, https://archive.org/details/oed6barch/page/238/mode/1up

- ^ The earliest published example is J. J. Sylvester (1850) "Additions to the articles in the September number of this journal, 'On a new class of theorems,' and on Pascal's theorem," The London, Edinburgh, and Dublin Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science, 37: 363-370. From page 369: "For this purpose, we must commence, not with a square, but with an oblong arrangement of terms consisting, suppose, of m lines and n columns. This does not in itself represent a determinant, but is, as it were, a Matrix out of which we may form various systems of determinants ... "

- ^ Sylvester (1904), p. 247, Paper 37.

- ^ Cayley (1858).

- ^ Dieudonné (1978), Vol. 1, Ch. III, p. 96.

- ^ أ ب Knobloch (1994).

- ^ Hawkins (1975).

- ^ Kronecker 1897

- ^ Weierstrass 1915, pp. 271–286

- ^ & Miller (1930).

- ^ Bôcher (2004).

- ^ Hawkins (1972).

- ^ van der Waerden (2007), pp. 28–40.

- ^ Peres (1993), pp. 79, 106–107.

- ^ Whitehead, Alfred North; and Russell, Bertrand (1913) Principia Mathematica to *56, Cambridge at the University Press, Cambridge UK (republished 1962) cf page 162ff.

- ^ Tarski (1941), p. 40.

المراجع

- Anton, Howard (1987), Elementary Linear Algebra (5th ed.), New York: Wiley, ISBN 0-471-84819-0

- Arnold, Vladimir I.; Cooke, Roger (1992), Ordinary differential equations, Berlin, DE; New York, NY: Springer-Verlag, ISBN 978-3-540-54813-3

- Artin, Michael (1991), Algebra, Prentice Hall, ISBN 978-0-89871-510-1

- Association for Computing Machinery (1979), Computer Graphics, Tata McGraw–Hill, ISBN 978-0-07-059376-3

- Baker, Andrew J. (2003), Matrix Groups: An Introduction to Lie Group Theory, Berlin, DE; New York, NY: Springer-Verlag, ISBN 978-1-85233-470-3

- Bau III, David; Trefethen, Lloyd N. (1997), Numerical linear algebra, Philadelphia, PA: Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics, ISBN 978-0-89871-361-9

- Beauregard, Raymond A.; Fraleigh, John B. (1973), A First Course In Linear Algebra: with Optional Introduction to Groups, Rings, and Fields, Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., ISBN 0-395-14017-X

- Bretscher, Otto (2005), Linear Algebra with Applications (3rd ed.), Prentice Hall

- Bronson, Richard (1970), Matrix Methods: An Introduction, New York: Academic Press

- Bronson, Richard (1989), Schaum's outline of theory and problems of matrix operations, New York: McGraw–Hill, ISBN 978-0-07-007978-6

- Brown, William C. (1991), Matrices and vector spaces, New York, NY: Marcel Dekker, ISBN 978-0-8247-8419-5

- Coburn, Nathaniel (1955), Vector and tensor analysis, New York, NY: Macmillan, OCLC 1029828

- Conrey, J. Brian (2007), Ranks of elliptic curves and random matrix theory, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-69964-8

- Fraleigh, John B. (1976), A First Course In Abstract Algebra (2nd ed.), Reading: Addison-Wesley, ISBN 0-201-01984-1

- Fudenberg, Drew; Tirole, Jean (1983), Game Theory, MIT Press

- Gilbarg, David; Trudinger, Neil S. (2001), Elliptic partial differential equations of second order (2nd ed.), Berlin, DE; New York, NY: Springer-Verlag, ISBN 978-3-540-41160-4

- Godsil, Chris; Royle, Gordon (2004), Algebraic Graph Theory, Graduate Texts in Mathematics, 207, Berlin, DE; New York, NY: Springer-Verlag, ISBN 978-0-387-95220-8

- Golub, Gene H.; Van Loan, Charles F. (1996), Matrix Computations (3rd ed.), Johns Hopkins, ISBN 978-0-8018-5414-9

- Greub, Werner Hildbert (1975), Linear algebra, Graduate Texts in Mathematics, Berlin, DE; New York, NY: Springer-Verlag, ISBN 978-0-387-90110-7

- Halmos, Paul Richard (1982), A Hilbert space problem book, Graduate Texts in Mathematics, 19 (2nd ed.), Berlin, DE; New York, NY: Springer-Verlag, ISBN 978-0-387-90685-0

- Horn, Roger A.; Johnson, Charles R. (1985), Matrix Analysis, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-38632-6

- Householder, Alston S. (1975), The theory of matrices in numerical analysis, New York, NY: Dover Publications

- Kreyszig, Erwin (1972), Advanced Engineering Mathematics (3rd ed.), New York: Wiley, ISBN 0-471-50728-8, https://archive.org/details/advancedengineer00krey.

- Krzanowski, Wojtek J. (1988), Principles of multivariate analysis, Oxford Statistical Science Series, 3, The Clarendon Press Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-852211-9

- Itô, Kiyosi, ed. (1987), Encyclopedic dictionary of mathematics. Vol. I-IV (2nd ed.), MIT Press, ISBN 978-0-262-09026-1

- Lang, Serge (1969), Analysis II, Addison-Wesley

- Lang, Serge (1987a), Calculus of several variables (3rd ed.), Berlin, DE; New York, NY: Springer-Verlag, ISBN 978-0-387-96405-8, https://archive.org/details/calculusofsevera0000lang

- Lang, Serge (1987b), Linear algebra, Berlin, DE; New York, NY: Springer-Verlag, ISBN 978-0-387-96412-6

- قالب:Lang Algebra

- Latouche, Guy; Ramaswami, Vaidyanathan (1999), Introduction to matrix analytic methods in stochastic modeling (1st ed.), Philadelphia, PA: Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics, ISBN 978-0-89871-425-8

- Manning, Christopher D.; Schütze, Hinrich (1999), Foundations of statistical natural language processing, MIT Press, ISBN 978-0-262-13360-9

- Mehata, K. M.; Srinivasan, S. K. (1978), Stochastic processes, New York, NY: McGraw–Hill, ISBN 978-0-07-096612-3

- Mirsky, Leonid (1990), An Introduction to Linear Algebra, Courier Dover Publications, ISBN 978-0-486-66434-7, https://books.google.com/?id=ULMmheb26ZcC&pg=PA1&dq=linear+algebra+determinant

- Nering, Evar D. (1970), Linear Algebra and Matrix Theory (2nd ed.), New York: Wiley

- Nocedal, Jorge; Wright, Stephen J. (2006), Numerical Optimization (2nd ed.), Berlin, DE; New York, NY: Springer-Verlag, p. 449, ISBN 978-0-387-30303-1

- Oualline, Steve (2003), Practical C++ programming, O'Reilly, ISBN 978-0-596-00419-4

- Press, William H.; Flannery, Brian P.; Teukolsky, Saul A.; Vetterling, William T. (1992), "LU Decomposition and Its Applications", Numerical Recipes in FORTRAN: The Art of Scientific Computing (2nd ed.), Cambridge University Press, pp. 34–42, Archived from the original on 2009-09-06, https://web.archive.org/web/20090906113144/http://www.mpi-hd.mpg.de/astrophysik/HEA/internal/Numerical_Recipes/f2-3.pdf

- Protter, Murray H.; Morrey, Jr., Charles B. (1970), College Calculus with Analytic Geometry (2nd ed.), Reading: Addison-Wesley

- Punnen, Abraham P.; Gutin, Gregory (2002), The traveling salesman problem and its variations, Boston, MA: Kluwer Academic Publishers, ISBN 978-1-4020-0664-7

- Reichl, Linda E. (2004), The transition to chaos: conservative classical systems and quantum manifestations, Berlin, DE; New York, NY: Springer-Verlag, ISBN 978-0-387-98788-0

- Rowen, Louis Halle (2008), Graduate Algebra: noncommutative view, Providence, RI: American Mathematical Society, ISBN 978-0-8218-4153-2

- Šolin, Pavel (2005), Partial Differential Equations and the Finite Element Method, Wiley-Interscience, ISBN 978-0-471-76409-0

- Stinson, Douglas R. (2005), Cryptography, Discrete Mathematics and its Applications, Chapman & Hall/CRC, ISBN 978-1-58488-508-5

- Stoer, Josef; Bulirsch, Roland (2002), Introduction to Numerical Analysis (3rd ed.), Berlin, DE; New York, NY: Springer-Verlag, ISBN 978-0-387-95452-3

- Ward, J. P. (1997), Quaternions and Cayley numbers, Mathematics and its Applications, 403, Dordrecht, NL: Kluwer Academic Publishers Group, doi:, ISBN 978-0-7923-4513-8

- Wolfram, Stephen (2003), The Mathematica Book (5th ed.), Champaign, IL: Wolfram Media, ISBN 978-1-57955-022-6

مراجع فيزياء

- Bohm, Arno (2001), Quantum Mechanics: Foundations and Applications, Springer, ISBN 0-387-95330-2

- Burgess, Cliff; Moore, Guy (2007), The Standard Model. A Primer, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-86036-9

- Guenther, Robert D. (1990), Modern Optics, John Wiley, ISBN 0-471-60538-7

- Itzykson, Claude; Zuber, Jean-Bernard (1980), Quantum Field Theory, McGraw–Hill, ISBN 0-07-032071-3

- Riley, Kenneth F.; Hobson, Michael P.; Bence, Stephen J. (1997), Mathematical methods for physics and engineering, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-55506-X

- Schiff, Leonard I. (1968), Quantum Mechanics (3rd ed.), McGraw–Hill

- Weinberg, Steven (1995), The Quantum Theory of Fields. Volume I: Foundations, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-55001-7, https://archive.org/details/quantumtheoryoff00stev

- Wherrett, Brian S. (1987), Group Theory for Atoms, Molecules and Solids, Prentice–Hall International, ISBN 0-13-365461-3

- Zabrodin, Anton; Brezin, Édouard; Kazakov, Vladimir; Serban, Didina; Wiegmann, Paul (2006), Applications of Random Matrices in Physics (NATO Science Series II: Mathematics, Physics and Chemistry), Berlin, DE; New York, NY: Springer-Verlag, ISBN 978-1-4020-4530-1

مراجع تاريخية

- A. Cayley A memoir on the theory of matrices. Phil. Trans. 148 1858 17-37; Math. Papers II 475-496

- Bôcher, Maxime (2004), Introduction to higher algebra, New York, NY: Dover Publications, ISBN 978-0-486-49570-5, reprint of the 1907 original edition

- Cayley, Arthur (1889), The collected mathematical papers of Arthur Cayley, I (1841–1853), Cambridge University Press, pp. 123–126, https://quod.lib.umich.edu/cgi/t/text/pageviewer-idx?c=umhistmath;cc=umhistmath;rgn=full%20text;idno=ABS3153.0001.001;didno=ABS3153.0001.001;view=image;seq=00000140

- Dieudonné, Jean, ed. (1978), Abrégé d'histoire des mathématiques 1700-1900, Paris, FR: Hermann

- Hawkins, Thomas (1975), "Cauchy and the spectral theory of matrices", Historia Mathematica 2: 1–29, doi:, ISSN 0315-0860

- Knobloch, Eberhard (1994), "From Gauss to Weierstrass: determinant theory and its historical evaluations", The intersection of history and mathematics, Science Networks Historical Studies, 15, Basel, Boston, Berlin: Birkhäuser, pp. 51–66

- Kronecker, Leopold (1897), Hensel, Kurt, ed., Leopold Kronecker's Werke, Teubner, https://quod.lib.umich.edu/cgi/t/text/text-idx?c=umhistmath;idno=AAS8260.0002.001

- Mehra, Jagdish; Rechenberg, Helmut (1987), The Historical Development of Quantum Theory (1st ed.), Berlin, DE; New York, NY: Springer-Verlag, ISBN 978-0-387-96284-9

- Shen, Kangshen; Crossley, John N.; Lun, Anthony Wah-Cheung (1999), Nine Chapters of the Mathematical Art, Companion and Commentary (2nd ed.), Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-853936-0

- Weierstrass, Karl (1915), Collected works, 3, https://quod.lib.umich.edu/cgi/t/text/text-idx?c=umhistmath;idno=AAN8481.0003.001

وصلات خارجية

- Encyclopedic articles

- History

- MacTutor: Matrices and determinants

- Matrices and Linear Algebra on the Earliest Uses Pages

- Earliest Uses of Symbols for Matrices and Vectors

- Online books

- Kaw, Autar K., Introduction to Matrix Algebra, ISBN 978-0-615-25126-4, http://autarkaw.com/books/matrixalgebra/index.html

- (PDF)The Matrix Cookbook, http://www.math.uwaterloo.ca/~hwolkowi//matrixcookbook.pdf, retrieved on 24 March 2014

- Brookes, Mike (2005), The Matrix Reference Manual, London: Imperial College, http://www.ee.ic.ac.uk/hp/staff/dmb/matrix/intro.html, retrieved on 10 Dec 2008

- Online matrix calculators

- matrixcalc (Matrix Calculator), https://matrixcalc.org/en/

- SimplyMath (Matrix Calculator), https://simplemath.online/linear-algebra/matrix-and-vector.html

- Free C++ Library, https://github.com/nom-de-guerre/Matrices

- Matrix Calculator (DotNumerics), http://www.dotnumerics.com/MatrixCalculator/

- Xiao, Gang, Matrix calculator, http://wims.unice.fr/wims/wims.cgi?module=tool/linear/matrix.en, retrieved on 10 Dec 2008

- Online matrix calculator, http://www.bluebit.gr/matrix-calculator/, retrieved on 10 Dec 2008

- Online matrix calculator (ZK framework), Archived from the original on 2013-05-12, https://web.archive.org/web/20130512101418/http://matrixcalc.info/MatrixZK/, retrieved on 26 Nov 2009

- Oehlert, Gary W.; Bingham, Christopher, MacAnova, University of Minnesota, School of Statistics, http://www.stat.umn.edu/macanova/macanova.home.html, retrieved on 10 Dec 2008, a freeware package for matrix algebra and statistics

- Online matrix calculator, https://www.idomaths.com/matrix.php, retrieved on 14 Dec 2009

- Operation with matrices in R (determinant, track, inverse, adjoint, transpose)

- Matrix operations widget in Wolfram|Alpha

![{\displaystyle [\mathbf {AB} ]_{i,j}=a_{i,1}b_{1,j}+a_{i,2}b_{2,j}+\cdots +a_{i,n}b_{n,j}=\sum _{r=1}^{n}a_{i,r}b_{r,j},}](https://www.marefa.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/c903c2c14d249005ce9ebaa47a8d6c6710c1c29e)

![{\displaystyle H(f)=\left[{\frac {\partial ^{2}f}{\partial x_{i}\,\partial x_{j}}}\right].}](https://www.marefa.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/9cf91a060a82dd7a47c305e9a4c2865378fcf35f)

![{\displaystyle J(f)=\left[{\frac {\partial f_{i}}{\partial x_{j}}}\right]_{1\leq i\leq m,1\leq j\leq n}.}](https://www.marefa.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/bdbd42114b895c82930ea1e229b566f71fd6b07d)

![{\displaystyle \left[{\begin{smallmatrix}0.7&0\\0.3&1\end{smallmatrix}}\right]}](https://www.marefa.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/ed9fb2da165c906a24f1d1c3d672b29e70dcfe17)

![{\displaystyle \left[{\begin{smallmatrix}0.7&0.2\\0.3&0.8\end{smallmatrix}}\right]}](https://www.marefa.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/5ac0656499afbf0abed73c2f804c408089444f57)