اعتقال الأمريكان اليابانيين

| |

| التاريخ | 19 فبراير 1942 – 20 مارس 1946[1][2][3] |

|---|---|

| الموقع | |

| السجناء | بين 110,000 و 120,000 أمريكي ياباني يعيشون في الساحل الغربي 1,200 إلى 1,800 يعيشون في هاوائي |

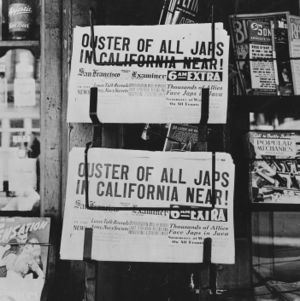

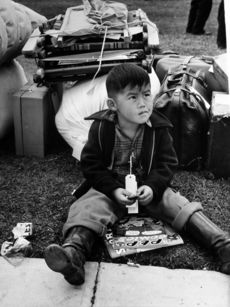

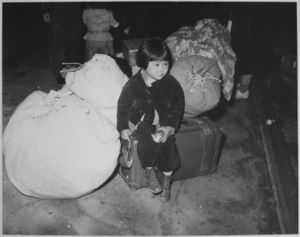

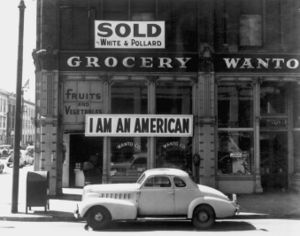

اعتقال الأمريكان اليابانيين في الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية أثناء الحرب العالمية الثانية كان تهجير وحجز قسري في معسكرات اعتقال الولايات المتحدة الغربية التي يبلغ عدد سكانها حوالي 120.000 [5] شعب من أصول يابانية ، يعيش معظمهم على ساحل المحيط الهادئ. اثنان وستون بالمائة من المعتقلين كانوا من مواطني الولايات المتحدة. [6][7] وقد أمر الرئيس فرانكلن روزڤلت بهذه الإجراءات بعد وقت قصير من هجوم امبراطورية اليابان على پيرل هاربور.[8]

من بين 127 ألف أمريكي ياباني كانوا يعيشون في الولايات المتحدة القارية وقت هجوم بيرل هاربور ، كان هناك 112 ألفًا يقيمون في الساحل الغربي.[9] كان هناك حوالي 80 ألفًا من "نيسي" (الترجمة الحرفية: "الجيل الثاني" ؛ ياباني المولد أمريكي ويحمل الجنسية الأمريكية) و "سانسي" ("الجيل الثالث" ؛ أبناء نيسي) . وكان الباقون من المهاجرين "عيسى" ("الجيل الأول") المولودين في اليابان والذين لم يكونوا مؤهلين للحصول على الجنسية الأمريكية بموجب قانون الولايات المتحدة.[10]

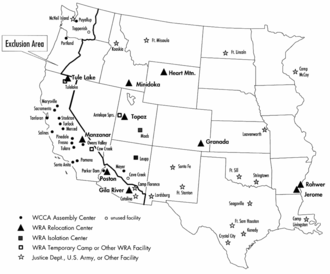

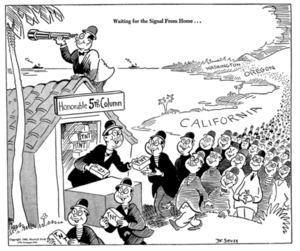

تم سجن الأمريكيين اليابانيين على أساس التركيزات السكانية المحلية والسياسات الإقليمية. تم إجبار أكثر من 112000 أمريكي ياباني يعيشون على الساحل الغربي على العيش في معسكرات داخلية. ومع ذلك ، في هاواي ، حيث يشكل أكثر من 150.000 أمريكي ياباني أكثر من ثلث السكان ، تم أيضًا اعتقال 1200 إلى 1800 فقط.[11] يعتبر الاعتقال نتاجًا للعنصرية أكثر من أي خطر أمني يمثله الأمريكيون اليابانيون. [12][13] حددت ولاية كاليفورنيا أي شخص لديه سلالة يابانية 1/16 أو أكثر بأنه كافٍ ليتم اعتقاله.[14] ذهب العقيد كارل بينديتسين ، المهندس المعماري وراء البرنامج ، إلى حد القول إن أي شخص لديه "قطرة دم يابانية واحدة" مؤهل.[15]

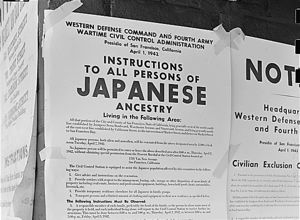

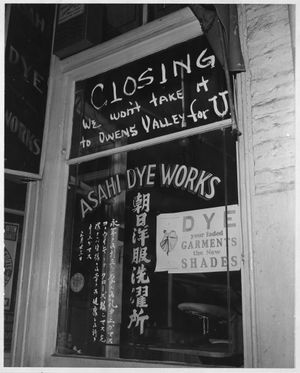

أذن روزفلت بالأمر التنفيذي رقم 9066 ، الصادر في 19 فبراير 1942 ، والذي سمح للقادة العسكريين الإقليميين بتحديد "المناطق العسكرية" التي "يمكن استبعاد أي شخص أو جميع الأشخاص منها".[16] على الرغم من أن الأمر التنفيذي لم يذكر الأمريكيين اليابانيين ، فقد تم استخدام هذه السلطة للإعلان عن مطالبة جميع الأشخاص من أصل ياباني بمغادرة ألاسكا[17] ومناطق الحظر العسكري من كل من كاليفورنيا وأجزاء من أوريگون وواشنطن وأريزونا ، باستثناء تلك الموجودة في المعسكرات الحكومية. [18] تم نقل ما يقرب من 5000 أمريكي ياباني خارج منطقة الاستبعاد قبل مارس 1942 ،[19] في حين تم اعتقال حوالي 5،500 من قادة المجتمع مباشرة بعد هجوم بيرل هاربور وبالتالي كانوا بالفعل في الحجز.[20]

ساعد مكتب تعداد الولايات المتحدة جهود الاعتقال من خلال التجسس وتوفير معلومات سرية حول الجوار عن الأمريكيين اليابانيين. نفى المكتب دوره لعقود على الرغم من الأدلة العلمية على عكس ذلك ،[21] وأصبح دورها معترفًا به على نطاق واسع بحلول عام 2007.[22][23] في عام 1944 ، الولايات المتحدة أيدت المحكمة العليا دستورية الإزالة بالحكم ضد فريد كوريماتسو الاستئناف لانتهاكه أمر الاستبعاد.[24] قصرت المحكمة قرارها على صلاحية أوامر الاستبعاد ، متجنبة مسألة حبس المواطنين الأمريكيين دون اتباع الإجراءات القانونية الواجبة.[25]

في عام 1980 ، وتحت ضغط متزايد من رابطة المواطنين الأمريكيين اليابانيين ومنظمات الإنصاف ،[26] فتح الرئيس جيمي كارتر تحقيقًا لتحديد ما إذا كان قرار وضع الأمريكيين اليابانيين في معسكرات الاعتقال مبررًا من قبل الحكومة. عين لجنة إعادة توطين المدنيين وقت الحرب واعتقالهم (CWRIC) للتحقيق في المخيمات. وجد تقرير اللجنة ، بعنوان "إنكار العدالة الشخصية" ، وجد القليل من الأدلة على عدم ولاء اليابانيين في ذلك الوقت وخلص إلى أن السجن كان نتاجًا للعنصرية. وأوصت بأن تدفع الحكومة التعويضات للمعتقلين. في عام 1988 ، وقع الرئيس رونالد ريغان علي قانون الحريات المدنية لعام 1988 الذي اعتذر عن الاعتقال نيابة عن حكومة الولايات المتحدة وأذنت بدفع مبلغ 20000 دولار (equivalent to $39٬000 in 2022) لكل ناجٍ من المعسكر. واعترف التشريع بأن تصرفات الحكومة تستند إلى "التحيز العرقي وهستيريا الحرب وفشل القيادة السياسية".[27] دفعت الحكومة الأمريكية في النهاية أكثر من 1.6 مليار دولار كتعويضات إلى 82،219 يابانيًا أمريكيًا تم اعتقالهم وورثتهم.[26][28]

خلفية

الأمريكان اليابانيون قبل الحرب العالمية الثانية

بعد پيرل هاربر

التطورات

الأمر التنفيذي 9066 والخطوات المتعلقة

المدافعون والمعارضون لمعسكرات الاعتقال الأمريكية

دعاة غير عسكريين للإقصاء والعزل والاحتجاز

بيان الضرورة العسكرية كمبرر للاعتقال

حادث نيهاو

التشفير

آراء محكمة الولايات المتحدة المحلية

تقرير رينگل

المنشآت

مراكز نقل WRA

| Name | State | Opened | Max. Pop'n |

|---|---|---|---|

| Manzanar | California | March 1942 | 10,046 |

| Tule Lake | California | May 1942 | 18,789 |

| Poston | Arizona | May 1942 | 17,814 |

| Gila River | Arizona | July 1942 | 13,348 |

| Granada | Colorado | August 1942 | 7,318 |

| Heart Mountain | Wyoming | August 1942 | 10,767 |

| Minidoka | Idaho | August 1942 | 9,397 |

| Topaz | Utah | September 1942 | 8,130 |

| Rohwer | Arkansas | September 1942 | 8,475 |

| Jerome | Arkansas | October 1942 | 8,497 |

قائمة المخيمات

مراكز التجمعات المدنية

مراكز النقل

معسكرات الاعتقال بوزارة العدل

مراكز عزل المواطنين

المكتب الفدرالي للسجون

الولايات المتحدة منشآت الجيش

مرافق خدمة الهجرة والجنسية

الاستبعاد والعزل والاحتجاز

أوضاع المخيمات

الرعاية الطبية

التعليم

أعقاب

المشقة والخسارة المادية

المقارنات

اعتقال أفراد بارزين

الإرث

الإرث الثقافي

المعارض والمجموعات

أنظر أيضاً

- American propaganda during World War II

- Arizona during World War II

- California during World War II

- Day of Remembrance (Japanese Americans)

- Empty Chair Memorial

- Japanese American service in World War II

- Japanese Evacuation and Resettlement Study

- List of World War II prisoner-of-war camps in the United States

- Mochizuki v. United States

- Population transfer

- Trump administration family separation policy

المصادر

- ^ Burton, J.; Farrell, M.; Lord, F.; Lord, R. "Confinement and Ethnicity (Chapter 3)". www.nps.gov. National Park Service. Retrieved November 30, 2016.

- ^ "Japanese American Internment » Tule Lake". njahs.org. National Japanese American Historical Society. Retrieved November 30, 2016.

- ^ Weik, Taylor (March 16, 2016). "Behind Barbed Wire: Remembering America's Largest Internment Camp". NBC News. Retrieved November 30, 2016.

- ^ National Park Service (2012). Wyatt, Barbara (ed.). "Japanese Americans in World War II: National historic landmarks theme study" (PDF). Washington, DC: U.S. Department of the Interior. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 13, 2015. Retrieved February 22, 2017.

- ^ The official WRA record from 1946 state it was 120,000 people. See War Relocation Authority (1946). The Evacuated People: A Quantitative Study. p. 8.. This number does not include people held in other camps such as run by the DoJ or Army. Other sources may give numbers slightly more or less than 120,000.

- ^ Semiannual Report of the War Relocation Authority, for the period January 1 to June 30, 1946, not dated. Papers of Dillon S. Myer. Scanned image at trumanlibrary.org. Retrieved September 18, 2006.

- ^ "The War Relocation Authority and The Incarceration of Japanese Americans During World War II: 1948 Chronology," Web page at www.trumanlibrary.org. Retrieved September 11, 2006.

- ^ "Manzanar National Historic Site". National Park Service.

- ^ Okihiro, Gary Y. The Columbia Guide to Asian American History. 2005, p. 104

- ^ Nash, Gary B., Julie Roy Jeffrey, John R. Howe, Peter J. Frederick, Allen F. Davis, Allan M. Winkler, Charlene Mires, and Carla Gardina Pestana. The American People, Concise Edition Creating a Nation and a Society, Combined Volume (6th Edition). New York: Longman, 2007

- ^ Ogawa, Dennis M. and Fox, Jr., Evarts C. Japanese Americans, from Relocation to Redress. 1991, p. 135.

- ^ Commission on Wartime Relocation of Civilians (1997). Personal Justice Denied. Washington, D.C.: Civil Liberties Public Education Fund. p. 459.

- ^ "WWII Propaganda: The Influence of Racism – Artifacts Journal – University of Missouri". artifactsjournal.missouri.edu.

- ^ Catherine Collins (2018). Representing Wars from 1860 to the Present: Fields of Action, Fields of Vision. Brill. p. 105. Retrieved September 29, 2019.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةSmithsonianAMPU - ^ Executive Order 9066 dated February 19, 1942, in which President Franklin D. Roosevelt Authorizes the Secretary of War to Prescribe Military Areas. File Unit: Executive Orders 9041 – 9070, 1/26/1942 – 2/24/1942. National Archives and Records Administration. February 19, 1942. Retrieved December 15, 2015.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - ^ Brian Garfield (February 1, 1995). The Thousand-mile War: World War II in Alaska and the Aleutians. University of Alaska Press. p. 48.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|nopp=ignored (|no-pp=suggested) (help) - ^ Korematsu v. United States, 323 U.S. 214, Dissenting opinion by Justice Owen Roberts (Supreme Court of the United States خطأ: لا توجد وحدة بهذا الاسم "auto date formatter".).

- ^ Niiya, Brian. "Voluntary Evacuation". Densho. Retrieved March 12, 2014.

- ^ "About the Incarceration". Densho. Retrieved July 13, 2019.

- ^ Roger Daniels (1982). "The Bureau of the Census and the Relocation of Japanese Americans: A Note and Document". Amerasia Journal. 9 (1): 101–105.

- ^ JR Minkel (March 30, 2007). "Confirmed: The U.S. Census Bureau Gave Up Names of Japanese-Americans in WW II". Scientific American.

- ^ Haya El Nasser (March 30, 2007). "Papers show Census role in WWII camps". USA Today.

- ^ Korematsu v. United States, 323 U.S. 214, Majority opinion by Hugo Black (Supreme Court of the United States خطأ: لا توجد وحدة بهذا الاسم "auto date formatter".).

- ^ Hakim, Joy (1995). A History of Us: War, Peace and All That Jazz. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 100–04. ISBN 0-19-509514-6.

- ^ أ ب Yamato, Sharon. "Civil Liberties Act of 1988". Densho Encyclopedia. Retrieved March 11, 2014.

- ^ 100th Congress, S. 1009, reproduced at, internmentarchives.com. Retrieved September 19, 2006.

- ^ "Wwii Reparations: Japanese-American Internees". Democracy Now!. Retrieved January 24, 2010.

- ^ Confinement and Ethnicity: An Overview of World War II Japanese American Relocation Sites, Jeffery F. Burton, Mary M. Farrell, Florence B. Lord, and Richard W. Lord, Chapter 3, NPS. Retrieved August 31, 2006.

قراءات أضافية

- Connell, Thomas (2002). America's Japanese Hostages: The US Plan For A Japanese Free Hemisphere. Westport: Praeger-Greenwood. ISBN 978-0275975357.

- Conn, Stetson (2000) [1960]. "5. The Decision to Evacuate the Japanese from the Pacific Coast". In Kent Roberts Greenfield (ed.). Command Decisions. United States Army Center of Military History. CMH Pub 70-7.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - Conn, Stetson; Engelman, Rose C.; Fairchild, Byron (2000) [1964]. Guarding the United States and its Outposts. United States Army in World War II. Washington, D.C.: Center of Military History, United States Army. pp. 115–49.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|chapterurl=(help) - Nevers, Nacy Clark de (2004). The Colonel and the Pacifist: Karl Bendetsen, Perry Saito, and the Incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II. Salty Lake City: University of Utah Press. ISBN 978-0-87480-789-9.

- Drinnon, Richard. Keeper of Concentration Camps: Dillon S. Meyer and American Racism. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1989.

- Elleman, Bruce (2006). Japanese-American civilian prisoner exchanges and detention camps, 1941–45. Routledge. p. 179. ISBN 978-0-415-33188-3. Retrieved September 14, 2009.

- Gardiner, Clinton Harvey (1981). Pawns in a Triangle of Hate: The Peruvian Japanese and the United States. Seattle: University of Washington Press. ISBN 978-0-295-95855-2.

- Gordon, Linda and Gary Y. Okihiro, ed. (2006). Impounded: Dorothea Lange and the Censored Images of Japanese American Internment. New York: W. W. Norton.

- Harth, Erica. (2001). Last Witnesses: Reflections on the Wartime Internment of Japanese Americans. Palgrave, New York. ISBN 0-312-22199-1.

- Havey, Lily Yuriko Nakai (2014). Gasa Gasa Girl Goes to Camp: A Nisei Youth behind a World War II Fence. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press. ISBN 978-1-60781-343-9.

- Higashide, Seiichi (2000). Adios to Tears: The Memoirs of a Japanese-Peruvian Internee in U.S. Concentration Camps. Seattle: University of Washington Press. ISBN 978-0-295-97914-4.

- Hirabayashi, Lane Ryo (1999). The Politics of Fieldwork: Research in an American Concentration Camp. Tucson: The University of Arizona Press.

- Inouye, Karen M. (2016). The Long Afterlife of Nikkei Wartime Incarceration. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Lyon, Chertin M. (2012). Prisons and Patriots: Japanese American Wartime Citizenship, Civil Disobedience, and Historical Memory. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

- Mike Mackey, ed. (1998). Remembering Heart Mountain: Essays on Japanese American Internment in Wyoming. Wyoming: Western History Publications.

- Robinson, Greg (2001). By Order of the President: FDR and the Internment of Japanese Americans. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Robinson, Greg (2009). A Tragedy of Democracy: Japanese Confinement in North America. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-12922-0.

- Sato, Kiyo (2009). Kiyo's Story, A Japanese-American Family's Quest for the American Dream. Soho Press. ISBN 9781569478660.

- Weglyn, Michi. (1996) [1976]. Years Of Infamy: The Untold Story Of America's Concentration Camps. University of Washington Press. ISBN 0-295-97484-2.

- Civil Liberties Public Education Fund. (1997). Personal Justice Denied: Report of the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians. Civil Liberties Public Education Fund and University of Washington Press. ISBN 0-295-97558-X.

وصلات خارجية

| مراجع مكتبية عن اعتقال الأمريكان اليابانيين |

مصادر أرشيفية للوثائق والصور والمواد الأخرى

- Japanese American Internment: Fear Itself – Lesson plans and photographs at U.S. Library of Congress.

- Society and Culture Collection – at the University of Washington Library consisting of historical images from Washington State

- Japanese American Internment Records available at the National Archives and Records Administration

- Densho: The Japanese American Legacy Project, Free digital archive containing hundreds of video oral histories and 10,000 historical photographs and documents

- "Japanese Americans In World War II", National Park Service, stories, photographs and documents.

- "Japanese American Relocation Digital Archives", University of California, contains personal & official photographs, letters, diaries, transcribed oral histories, etc.

- Large number of documents – Official documents, including official court opinions on the Yasui, Hirabayashi, and Korematsu Supreme Court cases

- Ansel Adams, "Photographs of Japanese American Internment at Manzanar", American Memory Collection, Library of Congress

- "Letters from the Japanese American Internment", Correspondence between librarian Clara Breed and young internees, Smithsonian Institution

- "Alien Enemy Detention Facility, Crystal City, Texas", film produced by the INS about Crystal City Alien Enemy Detention Facility, c. 1943

- JapaneseRelocation.org – World War II Japanese Relocation Camp Internee Records index

- Evacuation War Relocation Authority Photographs of Japanese-American Evacuation and Resettlement, 1942–1945, Japanese American Relocation Collection, and Inventory of the Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement Records, 1930–1974 (bulk 1942–1946) at The Bancroft Library

- University of Oregon Office of the Dean of Personnel Administration. National Japanese American Student Relocation Council records. Housed at the University of Oregon Libraries, the collection includes correspondence, newsletters, speeches, minutes of meetings, and ephemera.

- National Japanese Student Relocation Council Records housed at the Hoover Institution Library and Archives at Stanford University.

مصادر أخري

- Amy Kasai pictorial works depicting life in Japanese American internment camps [graphic], The Bancroft Library

- Letters by two Japanese-American schoolgirls from internment centers during World War II, 1942–1943, The Bancroft Library

- Japanese American relocation center views [graphic], The Bancroft Library

- Pamphlet boxes of materials on the Japanese in the United States during and after World War II. 1930–1946, The Bancroft Library

- Japanese American family photograph album from the World War Two era, The Bancroft Library

- Tom Hirashima letter : Summerland, Calif., to Burr E. Yarick, Tuolomne, Calif., 1942 April 6, The Bancroft Library

- World War II Internment Camps from the Handbook of Texas Online

- "Campaign For Justice: Redress Now For Japanese American Internees!". A website with information about the lesser known internment of Japanese Latin Americans

- A More Perfect Union: Japanese Americans and the U.S. Constitution Online exhibition from the National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution[dead link]

- California Office of the Attorney General collection of material on the pre-evacuation location of Japanese Americans in California, 1942, The Bancroft Library

- Japanese-American youth photograph album, The Bancroft Library

- National Park Service; Confinement and Ethnicity: An Overview of World War II Japanese American Relocation Sites.

- Kenji Sayama letters, The Bancroft Library

- Yamada family papers, The Bancroft Library

- Friends of Minidoka

- Ikeda family papers, The Bancroft Library

- Gerda Isenberg papers on Japanese American Internment, 1931–1990, The Bancroft Library

- Sharp Park Enemy Alien Detention Center views, Pacifica, Calif, The Bancroft Library

- 60 years after his landmark Supreme Court battle, Fred Korematsu is fighting racial profiling of Arabs

- Tule Lake Relocation Center by I. Fujimoto and D. Sunada

- Photographs of Japanese Americans in Los Angeles during the Second World War, The Bancroft Library

- Files from the National Japanese American Student Relocation Council, 1942–1943, The Bancroft Library

- International House records concerning Japanese Americans evacuation and relocation, 1942–1947, The Bancroft Library

- الفيلم القصير "Japanese Relocation with Milton Eisenhower" متاح للتنزيل المجاني على أرشيف الإنترنت [more]

- الفيلم القصير "Challenge to Democracy (Japanese Internment) (1942)" متاح للتنزيل المجاني على أرشيف الإنترنت [more]

- الفيلم القصير "Barriers And Passes, ca. 1939 – ca. 1945" متاح للتنزيل المجاني على أرشيف الإنترنت [more]

- CSPAN program "Japanese Americans During World War II" with George Takei, moderated by Kermit Roosevelt.

- Jerome T. Light papers, 1942–1948, The Bancroft Library

- Mark Sweeting, "A Lesson on the Japanese American Internment", 4-page lesson plan for high school students, 2004, Zinn Education Project/Rethinking Schools

- The National Constitution Center presents "Civil Liberties in Times of Crisis: Japanese American Internment and America Today" with Karen Korematsu and Kermit Roosevelt, moderated by Jess Bravin.

- Zoe Wyllie letters, 1942–1947, The Bancroft Library

- Prejudice, War, and the Constitution, by Jacobus tenBroek, Edward N. Barnhart, and Floyd W. Matsen; 1954; University of California Press. A must read for anyone seeking insight to the treatment of those who should have been, but were not, protected by our Constitution.

- Files relating to the evacuation of Japanese and Japanese Americans : Berkeley, Calif., 1942–1975, The Bancroft Library

قالب:Internment of Japanese Americans

![]() This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the National Archives and Records Administration.

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the National Archives and Records Administration.

- CS1 errors: periodical ignored

- CS1 errors: unsupported parameter

- Pages using cite court with unknown parameters

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Pages using infobox event with blank parameters

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Pages with empty portal template

- Articles with dead external links from November 2014

- Wikipedia articles incorporating text from the National Archives and Records Administration

- Internment of Japanese Americans

- Anti-Japanese sentiment in the United States

- Internments in the United States

- Japanese-American history

- Presidency of Franklin D. Roosevelt

- Racism in the United States

- United States home front during World War II

- World War II sites in the United States

- مقالات تحتوي مقاطع ڤيديو

- Persecution of Buddhists