المفاوضات المؤدية للاتفاقية الشاملة حول البرنامج النووي الإيراني

| جزء من سلسلة عن |

| البرنامج النووي الإيراني |

|---|

|

| خط زمني |

| المرافق |

| منظمات |

| اتفاقيات دولية |

| القوانين المحلية |

| أشخاص |

| متعلقة |

This article discusses the negotiations between the P5+1 and Iran that led to the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action.

The Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (فارسية: برنامه جامع اقدام مشترک), is an agreement signed in Vienna on 14 July 2015 between Iran and the P5+1 (the five permanent members of the United Nations Security Council – China, France, Russia, United Kingdom, United States, – plus Germany and the European Union). The agreement is a comprehensive agreement on the nuclear program of Iran.[1]

The agreement is based on the 24 November 2013 Geneva interim framework agreement, officially titled the Joint Plan of Action (JPA). The Geneva agreement was an interim deal,[2] in which Iran agreed to roll back parts of its nuclear program in exchange for relief from some sanctions and that went into effect on 20 January 2014.[3] The parties agreed to extend their talks with a first extension deadline on 24 November 2014[4] and a second extension deadline set to 1 July 2015.[5]

Based on the March/April 2015 negotiations on Iran nuclear deal framework, completed on 2 April 2015, Iran agreed tentatively to accept significant restrictions on its nuclear program, all of which would last for at least a decade and some longer, and to submit to an increased intensity of international inspections under a framework deal. These details were to be negotiated by the end of June 2015. On 30 June the negotiations on a Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action were extended under the Joint Plan of Action until 7 July 2015.[6] The agreement was signed in Vienna on 14 July 2015.

قائمة المرافق النووية الإيرانية المُعلنة

The following is a partial list of nuclear facilities in Iran (IAEA, NTI and other sources):[7][8]

- مفاعل طهران البحثي (TRR) — small 5MWt research reactor

- اصفهان, Uranium Conversion Facility (UCF)

- نطنز, Fuel Enrichment Plant (FEP) — plant for production of low enriched uranium (LEU), 16,428 installed centrifuges

- Natanz, Pilot Fuel Enrichment Plant (PFEP) — LEU production, and research and development facility, 702 installed centrifuges

- Fordow Fuel Enrichment Plant (FFEP) — plant for production of قالب:Uraniumقالب:Fluorine enriched up to 20% U-235, 2,710 installed centrifuges

- Arak, Iran Nuclear Research Reactor (IR-40 Reactor) — 40MWt heavy water reactor (under construction, no electrical output)

- Bushehr Nuclear Power Plant (BNPP)

خلفية

المفاوضات

الاتفاق بين مجموعة 5 + 1 + الاتحاد الأوروبي وإيران بشأن خطة العمل الشاملة المشتركة (JCPOA) هو تتويج لمدة 20 شهراً من المفاوضات "الشاقة".[9][10]

جاء الاتفاق عقب خطة العمل المشتركة (JPA)، وهو اتفاق مؤقت بين قوى 5 + 1 وإيران تم الاتفاق عليه في 24 نوفمبر 2013 في جنيڤ. كانت اتفاقية جنيڤ صفقة مؤقتة،[11] وافقت فيها إيران على التراجع عن أجزاء من برنامجها النووي مقابل إعفاء من بعض العقوبات. دخل الاتفاق حيز التنفيذ في 20 يناير 2014.[12] اتفق الطرفان على تمديد محادثاتهما مع تمديد الموعد النهائي لأول مرة في 24 نوفمبر 2014[4] والموعد النهائي للتمديد الثاني المحدد إلى 1 يوليو 2015.[5]

تم التوصل إلى إطار عمل الاتفاق النووي الإيراني في 2 أبريل 2015. بموجب هذا الإطار، وافقت إيران مبدئياً على قبول القيود المفروضة على برنامجها النووي، والتي ستستمر جميعها لمدة عشر سنوات على الأقل وبعضها لفترة أطول، والخضوع إلى زيادة كثافة عمليات التفتيش الدولية بموجب اتفاق إطاري. كان من المقرر التفاوض على هذه التفاصيل بحلول نهاية يونيو 2015. وتم تمديد المفاوضات نحو خطة عمل شاملة مشتركة عدة مرات حتى يتم التوصل إلى الاتفاق النهائي، وهي خطة العمل الشاملة المشتركة، أخيراً في 14 يوليو 2015.[13][14] تستند خطة العمل المشتركة الشاملة (JCPOA) إلى الاتفاقية الهيكلية التي تم وضعها قبل ثلاثة أشهر.

بعد ذلك استمرت المفاوضات بين إيران ومجموعة 5 + 1. في أبريل 2015، تم التوصل إلى اتفاق إطار العمل في لوزان. ثم استمرت المفاوضات الماراثونية المكثفة، حيث استمرت الجلسة الأخيرة في ڤيينا في پالاس كوبورگ لمدة سبعة عشر يوماً.[15] في عدة نقاط، بدا أن المفاوضات معرضة لخطر الانهيار، لكن المفاوضين تمكنوا من التوصل إلى اتفاق.[15] مع اقتراب المفاوضين من التوصل إلى اتفاق، طلب وزير الخارجية الأمريكية جون كري مباشرة من وزير الخارجية الإيراني محمد جواد ظريف تأكيد أنه "مخول حقاً بعقد صفقة، وليس فقط من قبل الرئيس [الإيراني] ولكن أيضاً من قبل المرشد الأعلى؟ "[15] وأكد ظريف أنه كان كذلك.[15]

في النهاية، في 14 يوليو 2015، وافقت جميع الأطراف على اتفاقية نووية شاملة تاريخية.[16]في وقت الإعلان، قبل الساعة 11:00 بتوقيت جرينتش بقليل، تم نشر الاتفاقية للجمهور.[17]

يُظهر تعقيد الاتفاقية النهائية التأثير على رسالة عامة كتبتها مجموعة من 19 دبلوماسياً وخبيراً أميركيين وآخرين من الحزبين في يونيو 2015، والتي كُتبت عندما كانت المفاوضات لا تزال جارية.[18][19] حددت الرسالة المخاوف بشأن العديد من البنود في الاتفاقية التي لم تنته بعد، ودعت إلى عدد من التحسينات لتعزيز الاتفاقية المحتملة وكسب دعمهم لها.[18] بعد التوصل إلى الاتفاق النهائي، قال أحد المفاوضين الأوائل، روبرت ج. آينهورن، وهو مسؤول سابق في وزارة الخارجية الأمريكية يعمل الآن في مؤسسة بروكنگز، عن الاتفاقية: "سوف يفاجأ المحللون بسرور. وكلما زاد الاتفاق على الأشياء، قلّت الفرص المتاحة لصعوبات التنفيذ في وقت لاحق".[18]

ويستند الاتفاق النهائي (ويدعم) "نظام عدم الانتشار القائم على القواعد الذي أنشأته معاهدة عدم انتشار الأسلحة النووية (NPT) بما في ذلك بشكل خاص نظام ضمانات الوكالة الدولية للطاقة الذرية".[20]

الجولات

الجولة الأولى: 18–20 فبراير

انعقدت جولة من المفاوضات بين إيران وبلدان ق5+1، برئاسة الممثل السامي للاتحاد الاوروپي كاثرين آشتون،[21] في مدينة ألماتي بقزخستان في 26–27 فبراير 2013. إلتقى الجانبات مرة أخرة في المدينة في 5-6 أبريل لاستئناف المحادثات بعد عقد محادثات على مستوى الخبراء بمدينة إسطنبول التركية في 17–18 مارس.[22]

الجولة الثانية: 17–20 مارس

دبلوماسيون من الدول الستة، وبمشاركة آشتون وظريفة، التقوا مرة أخرى في ڤيينا في 17 مارس 2014. على أن تعقد سلسلة من المفاوضات قبل الموعد النهائي في يوليو 2014.[23]

الجولة الرابعة: 13–16 مايو

انتهت الجولة الرابعة من مفاوضات ڤيينا في 16 مايو 2014. عُقد اجتماع ثنائي إيراني أمريكي بين الوفد الإيراني برئاسة وزير الخارجية محمد جواد طريف وترأس الوفد الأمريكي مساعد وزير الدولة للشؤون السياسية وندي شرمان. هدف كلا الجانبين إلى صياغة اتفاقية نهائية، لكن لم يسفر الاجتماع إلا عن تقدم محدود.

الجولة الخامسة: 16–20 يونيو

الجولة الخامسة من المحادثات انتهت في 20 يونيو 2014، "مع بقاء اختلافات جوهرية". ستلتقي الأطراف المتفاوضة مرة أخرى في ڤيينا في 2 يوليو. في أعقاب المحادثات صرح وكيل الوزير شرمان أنه "لا يزال غير واضح" ما إذا كانت إيران تعمل "من أجل أن تضمن للعالم أن برنامجها النووي strictly meant للأغراض السلمية."[24] قال وزير الخارجية ظريف أن الولايات المتحدة تطالب إيران بمطالب غير معقولة، قائلاً "على الولايات المتحدة أن تتخذ أصعب القرارات."[25]

الجولة السادسة (الأخيرة): 2–20 يوليو

الجولة السادسة من المفاوضات النووية بين إيران ومجموعة ق5+1 بدأت في ڤيينا في 2 يوليو 2014. كانت الأطراف برئاسة وزير الخارجية الإيراني محمد جواد ظريف والممثل السامي للاتحاد الاوروپي كاثرين آشتون.[26]

الجولة السابعة (التمديد الأول): نيويورك

استؤنفت المفاوضات بين ق5+1 وإيران حول البرناج النووي الإيراني في 19 سبتمبر 2014. بدأوا على sidelines الجمعية العامة للأمم المتحدة ومُنح وزير الخارجية جون كري ونظرائه فرصة للإنضمام للمحادثات.[27][28] كان من المخطط أن تستمر المحادثات حتى 26 سبتمبر.[29][30]

الجولة الثامنة: ڤيينا

في اجتماع آخر عقدته بلدان ق5+1 في ڤيينا في أكتوبر 2013، أعلنت إيران أنها قد تسمح بزيارات غير معلنة لمواقعها النووية "كخطوة أخيرة" في مقترح لحل الاختلافات مع الغرب. كذلك سيكون اليورانيوم المخصب بمستويات منخفضة جزءاً من الاتفاق النهائي، حسب مسئولون إيرانيون.[31]

الجولة التاسعة: مسقط

عُقدت الجولة التاسعة من المحادثات في 11 نوفمبر في العاصمة العُمانية مسقط واستمرة ساعة واحدة. في اللقاء، تبادل وكلاء وزراء الخارجية الإيراني عباس أرقچي وماجد تخت راڤانچي وجهات النظر مع نظرائهما من ق5+1.[32] كانت الجولة تحت رئاسة الممثل السامي للاتحاد الاوروپي كاثرين آشتون، وعُقدت لإيجاز محادثات ق5+1 حول محادثات كري وظريف.[33] أفادت وكالات الأنباء المحلية عن بقاء بعض ممثلي الأطراف في مسقط للاستمرار في المحادثات.[34]

الجولة العاشرة: ڤيينا

استؤنفت المحادثات النووية بين إيران وق5+1 في ڤيينا في 18 نوفمبر 2014 بمشاركة وزير الخارجية الإيراني محمد ظريف، الممثل السامي للاتحاد الأوروپي كاثرين آشتون، ومسئولوا وزارة الخارجية. كان من المفتر أن تستمر المحادثات حتى 24 نوفمبر.[35][36]

في مؤتمر صحفي بعد محادثات ڤيينا صرح وزير الخارجية الإيراني محمد جواد ظريف: " البرنامج النووي الإيراني اليوم منظم دولياً ولا يتحدث أحد عن حقوقنا في التخصيب..."[37] ورداً على سؤال عن "الثغرات الأساسية حول مدى قدرة التخصيب التي سيسمح لإيران بامتلاكها"، أجاب وزير الخارجية الأمريكي جون كري في مؤتمر صحفي: "لن أؤكد ما إذا كان هناك ثغرة أم لا أو أين هي الثغرات. بلا شك توجد ثغرات. لقد قلنا هذا."[38]

الجولة الحادية عشر: ڤيينا

استؤنفت المفاوضات بين إيران وق5+1 في جنيڤ، 17 ديسمبر 2014 واستمرت يوماً واحداً. بعد المحادثات المغلقة، لم تصدر أي بيانات من قبل فريق المفاوضات الأمريكي أو المتحدث الرسمي باسم الاتحاد الأوروپي. صرح نائب وزير الخارجية أرقچي أنه تم الاتفاق على استمرار المحادثات "الشهر القادم" في مكان سيتم تقريره. صرح نائب وزير الخارجية الروسية ريابكوڤ أن مفاعل آراك للمياه الثقيلة والعقوبات ضد إيران كانتا القضيتين الرئيسيتين العالقتين في المحادثات النووية.[39][40]

الجولة الثانية عشر: ڤيينا

عقدت الجولة الثانية عشر، على مستوى المدراء السياسيون لإيران وق5+1، في 18 يناير 2015 في أعقاب محادثات ثنائية استمرت أربعة أيام بين الولايات المتحدة وإيران.[41] ترأست الاجتماعات المديرة السياسية الأوروپي هلگا شميد. بعد المحادثات صرح المفاوض الفرنسي نيكولا ده لا ريڤييه: "كانت الأجواء طيبة للغاية، لكني لا أعتقد أننا حققنا الكثير من المتقدم."[42] "لو كان هناك تقدم فإنه بطيء للغاية وليس هناك أي ضمانات بأن هذا التقدم سينتقل إلى تحول حاسم، ليتقدم نحو وسط،" صرح المفاوض الروسي سرگي ريابكوڤ للصحفيين، مضيفاً أن "الاختلافات الأساسية ظلت حول غالبية القضايا محل النزاع."[43]

الجولة الثالثة عشر: ڤيينا

التقى ممثلو إيران وق5+1 في 22 فبراير في المفوضية الأوروپية في جنيڤ. بعد اللقاء صرح نيكولا ده لا ريڤييه: "كان اللقاء بنيوي، سنعرف النتائج لاحقاً."[44][45]

وقد أعلن الرئيس الإيراني حسن روحاني: إيران ستلتزم بوعودها فقط إذا نفذت محموعة P5+1 التزاماتها.[47]

المحادثات الثنائية

المحادثات الأمريكية الإيرانية

المحادثات الأمريكية-الأوروپية=الإيرانية

النقاط الرئيسية محل الخلاف في المفاوضات

مخزون اليورانيوم وتخصيبه

Iran's nuclear enrichment capacity was the biggest stumbling block in the negotiations on a comprehensive agreement.[48][49][50][51][52][53] Iran has the right to enrich uranium under article IV of the Nuclear Non-proliferation Treaty.[54][55] The Security Council in its resolution 1929 has required Iran to suspend its uranium enrichment program.[56][57] For many years the United States held that no enrichment program should be permitted in Iran. In signing the Geneva interim agreement the United States and its P5+1 partners shifted away from zero enrichment to a limited enrichment objective.[58][59] Additionally, they have determined that the comprehensive solution will "have a specified long-term duration to be agreed upon" and once it has expired, Iran's nuclear program will not be under special restrictions.[60]

Limited enrichment would mean limits on the numbers and types of centrifuges. Shortly before the comprehensive negotiations began, Iran was estimated to have 19,000 centrifuges installed, mostly first generation IR-1 machines, with about 10,000 of them operating to increase the concentration of uranium-235. The Iranians strive to expand their enrichment capacity by a factor of ten or more while the six powers aim to cut the number of centrifuges to no more than a few thousand.[59]

Michael Singh argued in October 2013, that there were two distinct paths to deal with Iran's nuclear program: complete dismantling or allowing limited activities while preventing Iran from a nuclear "breakout capability",[61] also echoed by Colin H. Kahl, as published by the Center for a New American Security.[62] The measures that would lengthen breakout timelines include "limits on the number, quality and/or output of centrifuges".[62] Former Under Secretary of State for Arms Control and International Security Affairs Robert Joseph argued in the August 2014 National Review, published by the Arms Control Association, that attempts to overcome the impasse over centrifuges by using a malleable separative work unit metric "as a substitute for limiting the number of centrifuges is nothing more than sleight of hand." He has also quoted former U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton saying "any enrichment will trigger an arms race in the Middle East."[63]

Colin Kahl, former Deputy Assistant U.S. Secretary of Defense for the Middle East, estimated in May 2014 that Iran's stockpile was large enough to build 6 nuclear weapons and it had to be reduced. Constraints on Iran's uranium enrichment would reduce the chance that its nuclear program could be used to make nuclear warheads. The number and quality of centrifuges, research and development of advanced centrifuges, and the size of low-enriched uranium stockpiles, would be relevant. The constraints were interrelated with each other, that the more centrifuges Iran had, the smaller the stockpile the United States and P5+1 should accept, and vice versa.[64] Lengthening breakout timelines required a substantial reduction in enrichment capacity, and many experts[من؟] talk about an acceptable range of about 2000-6000 first-generation centrifuges. Iran stated[when?] that it wanted to extend its capability substantially.[بحاجة لمصدر] In May 2014 Robert J. Einhorn, former Special Advisor on Non-Proliferation and Arms Control at the U.S. Department of State, claimed that if Iran was to continue to insist on what he considered to be a huge number of centrifuges, then there would be no agreement, since this enrichment capacity would bring the breakout time down to weeks or days.[65]

Plutonium production and separation

Under Secretary of State Wendy Sherman, testifying before the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations, said that a good deal will be one that cuts off Iran's uranium, plutonium and covert pathways to obtain nuclear weapons.[66] Secretary of State John Kerry has testified before the United States House Committee on Foreign Affairs and expressed great concerns about the Arak nuclear reactor facility. "Now, we have strong feelings about what will happen in a final comprehensive agreement. From our point of view, Arak is unacceptable. You can't have a heavy-water reactor," he said.[67] President Barack Obama, while addressing the House of Representatives and Senate, emphasized that "these negotiations do not rely on trust; any long-term deal we agree to must be based on verifiable action that convinces us and the international community that Iran is not building a nuclear bomb."[68]

Fred Fleitz, a former CIA analyst and Chief of Staff to the United States Undersecretary of State for Arms, felt that compromises made by the Obama administration to achieve an agreement with Iran would be dangerous. Fleitz believed that such concessions were being proposed, and that the "... most dangerous is that we are considering letting Iran keep the Arak heavy water reactor which will be a source of plutonium. Plutonium is the most desired nuclear fuel for a bomb, it has a lower critical mass, you need less of it which is important in building a missile warhead."[69]

The head of Atomic Energy Organization of Iran Ali Akbar Salehi said that the heavy water reactor of Arak was designed as a research reactor and not for plutonium production. It will produce about 9 kg of plutonium but not weapons-grade plutonium. Dr. Salehi explained that "if you want to use the plutonium of this reactor you need a reprocessing plant". "We do not have a reprocessing plant, we do not intend, although it is our right, we will not forgo our right, but we do not intend to build a reprocessing plant." Salehi felt that the Western claims of concern about Iran developing nuclear weapons were not genuine, and that they were an excuse for applying political pressure on Iran.[70]

According to information provided by the Federation of American Scientists, a sizable research program involving the production of heavy water might raise concerns about a plutonium-based weapon program, especially if such program was not easily justifiable on other accounts.[71] Gregory S. Jones, a senior researcher and a defense policy analyst, claimed that if the heavy-water-production plant at Arak were not dismantled, Iran would be granted a "plutonium option" for acquiring nuclear weapons in addition to the centrifuge enrichment program.[72]

Agreement's duration

According to a November 2013 editorial in The Washington Post, the most troubling part of the Geneva interim agreement has been the "long-term duration" clause. This provision means that when the duration expires, "the Iranian nuclear program will be treated in the same manner as that of any non-nuclear weapon state party" to the NPT. Thus, once the comprehensive agreement expires, Iran will be able to "install an unlimited number of centrifuges and produce plutonium without violating any international accord."[73] The Nonproliferation Policy Education Center stated in May 2014 "clearly [the agreement] will only be a long-term interim agreement".[74]

The Brookings Institution suggested in March 2014 that if a single 20-year duration for all provisions of the agreement is too constraining, it would be possible to agree on different durations for different provisions. Some provisions could have short duration, and others could be longer. A few constraints, like enhanced monitoring at specific facilities, could be permanent.[60]

Al Jazeera reported in October 2014, that Iran wanted any agreement to last for at most 5 years while the United States prefers 20 years.[75] The twenty years is viewed as a minimum amount of time to develop confidence that Iran can be treated as other non-nuclear weapon states and allow the IAEA enough time to verify that Iran is fully compliant with all its non-proliferation obligations.[76]

Possible covert paths to fissile material

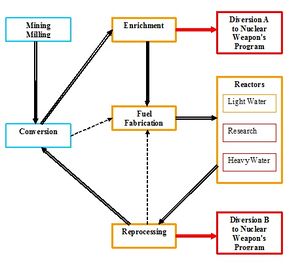

The Iranian uranium enrichment facilities at Natanz (FEP and PFEP) and Fordow (FFEP) were constructed covertly and designed to operate in a similar manner. In September 2009, Iran notified the International Atomic Energy Agency about constructing the Fordow facility only after it and Natanz were revealed by other sources.[77][78] The Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs quoted in 2014 a 2007 U.S. National Intelligence Estimate on Iran's nuclear capabilities and intentions stated: "We assess with high confidence that until fall 2003, Iranian military entities were working under government direction to develop nuclear weapons." Additionally the Estimate stated that after 2003 Iran had halted the covert enrichment for at least several years.[79][80] The Estimate also stated: "We assess with moderate confidence that Iran probably would use covert facilities—rather than its declared nuclear sites—for the production of highly enriched uranium for a weapon."[80] Some analysts have argued that negotiations between Iran and the P5+1, as well as most public discussions, were focused on Iran's overt nuclear facilities while alternative paths to obtain fissile material existed. Graham Allison, former United States Assistant Secretary of Defense, and Oren Setter, a research fellow at Belfer Center, compared this approach with Maginot's fixation on a single threat "that led to fatal neglect of alternatives". They pointed out at least three additional paths to obtain such material: Covert make, covert buy and hybrid pathway (a combination of overt and covert paths).[81][82]

The Belfer Center also quotes William Tobey, former Deputy Administrator for Defense Nuclear Nonproliferation at the National Nuclear Security Administration, as outlining the possible ways to nuclear weapons as follows: Break out of the Nonproliferation Treaty, using declared facilities, sneak out of the treaty, using covert facilities and buy a weapon from another nation or rogue faction.[79]

The Belfer Center published recommendations for agreement provisions relating to monitoring and verification in order to prevent covert activities and to provide tools to react if needed.[83][84][85][79] One of the sources warned the P5+1 that "if the monitoring elements that we recommend are not pursued now to diminish the risks of deception, it is difficult to envision that Iran would be compliant in the future, post-sanctions environment."[86] According to the recommendations the agreement with Iran should include a requirement to cooperate with the IAEA inspectors in compliance with the UN Security Council resolutions, transparency for centrifuges, mines and mills for uranium ore and yellowcake, monitoring of nuclear-related procurement, an obligation to ratify and implement the Additional Protocol[87] and to provide the IAEA enhanced powers beyond the Protocol, adhering to the modified Code 3.1,[88][89] monitoring of nuclear research and development (R&D), defining certain activities as breaches of the agreement that could provide basis for timely intervention.

تفتيش الوكالة الدولية للطاقة الذرية

The International Atomic Energy Agency inspected Iran's nuclear facilities several times annually since 2007, publishing from one to four reports each year. According to multiple resolutions of the United Nations Security Council (resolutions 1737, 1747, 1803, and 1929), enacted under Chapter VII of the United Nations Charter, Iran is obligated to cooperate fully with the IAEA on "all outstanding issues, particularly those which give rise to concerns about the possible military dimensions of the Iranian nuclear programme, including by providing access without delay to all sites, equipment, persons and documents requested by the IAEA. ..." On 11 November 2013 the IAEA and Iran signed a Joint Statement on a Framework for Cooperation committing both parties to cooperate and resolve all present and past issues in a step by step manner. As a first step, the Framework identified six practical measures to be completed within three months.[90] The IAEA reported that Iran had implemented those six measures in time.[91] In February and May 2014[92][93] the parties agreed to additional sets of measures related to the Framework.[94] In September the IAEA continued to report that Iran was not implementing its Additional Protocol, which is a prerequisite for the IAEA "to provide assurance about both declared and possible undeclared activities." Under those circumstances, the Agency reported it will not be able to provide "credible assurance about the absence of undeclared nuclear material and activities in Iran".[95][87]

The implementation of interim Geneva Accord has involved transparency measures and enhanced monitoring to ensure the peaceful nature of Iran's nuclear program. It was agreed that the IAEA will be "solely responsible for verifying and confirming all nuclear-related measures, consistent with its ongoing inspection role in Iran". IAEA inspection has included daily access to Natanz and Fordow and managed access to centrifuge production facilities, uranium mines and mills, and the Arak heavy water reactor.[96][97][98] To implement these and other verification steps, Iran committed to "provide increased and unprecedented transparency into its nuclear program, including through more frequent and intrusive inspections as well as expanded provision of information to the IAEA."[99]

Thus, there have been two ongoing diplomatic tracks—one by the P5+1 to curb Iran's nuclear program and a second by the IAEA to resolve questions about the peaceful nature of Iran's past nuclear activities. Although the IAEA inquiry has been formally separate from JPA negotiations, Washington said a successful IAEA investigation should be part of any final deal and that may be unlikely by the deadline of 24 November 2014.[100]

One expert on Iran's nuclear program, David Albright, has explained that "It's very hard if you are an IAEA inspector or analyst to say we can give you confidence that there's not a weapons program today if you don't know about the past. Because you don't know what was done. You don't know what they accomplished." Albright argued that this history is important since the "infrastructure that was created could pop back into existence at any point in secret and move forward on nuclear weapons."[101]

Iranian and IAEA officials met in Tehran on 16 and 17 August 2014 and discussed the five practical measures in the third step of the Framework for Cooperation agreed in May 2014.[102] Yukiya Amano, Director General of the IAEA, made a one-day visit to Tehran on 17 August and held talks with President of Iran Hassan Rouhani and other senior officials.[103] After the visit Iranian media criticized the IAEA while reporting that President Rouhani and the head of Atomic Energy Organization of Iran Salehi both tried "to make the IAEA chief Mr. Amano understand that there is an endpoint to Iran's flexibility."[بحاجة لمصدر] The same week Iranian Defense Minister Hossein Dehghan said that Iran will not give IAEA inspectors access to Parchin military base. Yukiya Amano has noted previously that access to the Parchin base was essential for the Agency to be in position to certify Iran's nuclear programme as peaceful.[104] Tehran was supposed to provide the IAEA with information related to the initiation of high explosives and to neutron transport calculations until 25 August, but it failed to address these issues.[105] The two issues are associated with compressed materials that are required to produce a warhead small enough to fit on top of a missile.[106] During its 7–8 October meetings with the IAEA in Tehran, Iran failed to propose any new practical measures to resolve the disputable issues.[107]

On 19 February 2015 IAEA has released its quarterly safeguards report on Iran.[108] While testifying before the United States House Foreign Affairs Subcommittee on the Middle East and North Africa, the ISIS's President David Albright commented on Iran's reaction to this report: "the Iranian government continues to dissemble and stonewall the inspectors and remains committed to severely weakening IAEA safeguards and verification in general."[109]

القضايا المتعلقة بالطاقة النووية خارج نطاق المفاوضات

There are many steps toward nuclear weapons.[110] However, an effective nuclear weapons capability has only three major elements:[111]

- Fissile or nuclear material in sufficient quantity and quality

- Effective means for delivery, such as a ballistic missile

- Design, weaponization, miniaturization, and survivability of the warhead

Evidence presented by the IAEA has shown that Iran has pursued all three of these elements: it has been enriching uranium for more than ten years and is constructing a heavy water reactor to produce plutonium, it has a well-developed ballistic missile program, and it has tested high explosives and compressed materials that can be used for nuclear warheads.[112]

Some analysts[من؟] believe that the elements that they believe would together constitute an Iranian nuclear weapons program should be negotiated together — the negotiations would include not only Iranian fissile material discussions but also Iranian ballistic missile development and Iranian weaponization issues.[113][114]

الأولويات في المراقبة والمنع

Henry Kissinger, former U.S. Secretary of State, stated in his 2014 book: "The best—perhaps the only—way to prevent the emergence of a nuclear weapons capability is to inhibit the development of a uranium-enrichment process ..."

Joint Plan of Action[115] has not explicitly addressed the future status of Iran's ballistic missile program. According to the Atlantic Council, as the Joint Plan of Action was an interim agreement, it could not take into account all the issues that should be resolved as part of a comprehensive agreement. If a comprehensive agreement with Iran "does not tackle the issue of ballistic missiles, it will fall short of and may undermine ... UN Security Council Resolutions." Moreover, shifting "monitoring and prevention aims onto warheads without addressing Iran's ballistic missile capacity also ignores U.S. legislation that forms the foundation of the sanctions regime against Iran".[116]

The Atlantic Council also stated that "monitoring warhead production is far more difficult than taking stock" of ballistic missiles and the US government is far less good at detecting advanced centrifuges or covert facilities for manufacturing nuclear warheads.[116]

Anthony Cordesman, a former Pentagon official and a holder of the Arleigh A. Burke Chair in Strategy at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), highlighted the view that the United States and other members of the P5+1, along with their attempts to limit Iran's breakout capability and to prevent it from getting even one nuclear device, should mainly focus "on reaching a full agreement that clearly denies Iran any ability to covertly create an effective nuclear force."[117]

برنامج الصواريخ البالستية

Iran's ballistic missiles have been claimed as evidence that Iran's nuclear program is weapons-related rather than civilian. Security Council Resolution 1929 "decides that Iran shall not undertake any activity related to ballistic missiles capable of delivering nuclear weapons."[118] In May–June 2014 a United Nations panel of experts submitted a report pointing to Iran's engagement in ballistic missile activities. The Panel reported that over the last year Iran has conducted a number of ballistic missile test launches, which were a violation of paragraph 9 of the resolution.[119]

Director of U.S. National Intelligence James Clapper testified on 12 March 2013, that Iran's ballistic missiles were capable of delivering WMD.[57] According to some analysts, the liquid-fueled Shahab-3 missile and the solid-fueled Sejjil missile have the ability to carry a nuclear warhead.[120] Iran's ballistic missile program is controlled by IRGC Air Force (AFAGIR), while Iran's combat aircraft is under the command of the regular Iranian Air Force (IRIAF).[57]

The United States and its allies view Iran's ballistic missiles as a subject for the talks on a comprehensive agreement since they regard it as a part of Iran's potential nuclear threat. Members of Iran's negotiating team in Vienna insisted the talks will not focus on this issue.[121]

A few days before 15 May, date when the next round of the negotiations was scheduled,[122] Iran's Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei responded to Western expectations on limits to Iran's missile program by saying that "[t]hey expect us to limit our missile program while they constantly threaten Iran with military action. So this is a stupid, idiotic expectation." He then called on the country's Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) to continue mass-producing missiles.[123]

In his testimony before the United States House Committee on Armed Services, Managing Director of the Washington Institute for Near East Policy Michael Singh argued "that Iran should be required to cease elements of its ballistic-missile and space-launch programs as part of a nuclear accord." This question was off the table since Iran's Supreme Leader has insisted that Iran's missile program is off-limits in the negotiations and P5+1 officials have been ambiguous.[113]

According to Debka.com, the United States in its direct dialogue with Iran outside the P5+1 framework demanded to restrict Iran's intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs), whose 4,000 kilometers range places Europe and the United States at risk. This demand did not apply to ballistic missiles, whose range of 2,100 km covers any point in the Middle East. These medium-range missiles may also be nuclear and are capable of striking Israel, Saudi Arabia and the Persian Gulf.[124]

In a Senate committee hearing former U.S. Secretary of State George Shultz has expressed belief that Iran's missile program and its ICBM capability, as well as what he described as Iran's support of the terrorism, should also be on the table.[125]

الأبعاد العسكرية المحتملة

Since 2002, the IAEA has become concerned and noted in its reports that some elements of Iran's nuclear program could be used for military purposes. More detailed information about suspected weaponization aspects of Iran's nuclear program—the possible military dimensions (PMD)—has been provided in the IAEA reports issued in May 2008 and November 2011. The file of Iran's PMD issues included development of detonators, high explosives initiation systems, neutron initiators, nuclear payloads for missiles and other kinds of developments, calculations and tests. The Security Council Resolution 1929 reaffirmed "that Iran shall cooperate fully with the IAEA on all outstanding issues, particularly those which give rise to concerns about the possible military dimensions of the Iranian nuclear program, including by providing access without delay to all sites, equipment, persons and documents requested by the IAEA."[77][126][127]

In November 2013 Iran and the IAEA have signed a Joint Statement on a Framework for Cooperation committing both parties to resolve all present and past issues.[90] In the same month the P5+1 and Iran have signed the Joint Plan of Action, which aimed to develop a long-term comprehensive solution for Iran's nuclear program. The IAEA continued to investigate PMD issues as a part of the Framework for Cooperation. The P5+1 and Iran have committed to establish a Joint Commission to work with the IAEA to monitor implementation of the Joint Plan and "to facilitate resolution of past and present issues of concern" with respect to Iran's nuclear program, including PMD of the program and Iran's activities at Parchin.[115][128] Some analysts asked what happens if Iran balks and IAEA fails to resolve significant PDM issues. According to the U.S. Department of State, any compliance issues wouldn't be discussed by the Joint Commission but would first be dealt with "at the expert level, and then come up to the political directors and up to foreign ministers if needed." Thus, an unresolved issue might be declared sufficiently addressed as a result of a political decision.[129]

Prior to the signing of an interim nuclear agreement, it was commonly understood in Washington that Iran must "come clean about the possible military dimensions of its nuclear program," as Undersecretary Wendy Sherman testified before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee in 2011. The Iranians have refused to acknowledge having a weaponization program. Meanwhile, analysts close to the Obama administration begin to boost the so-called limited disclosure option.[130] Nevertheless, 354 members of U.S. Congress were "deeply concerned with Iran's refusal to fully cooperate with the International Atomic Energy Agency." On 1 October 2014, they sent a letter to Secretary of State John Kerry stating that "Iran's willingness to fully reveal all aspects of its nuclear program is a fundamental test of Iran's intention to uphold a comprehensive agreement."[131]

Some organizations have published lists of suspected nuclear-weaponization facilities in Iran.[132][133] Below is a partial list of such facilities:

- Institute of Applied Physics (IAP)

- Kimia Maadan Company (KM)

- Parchin Military Complex

- Physics Research Center (PHRC)

- Tehran Nuclear Research Center (TNRC)

In September 2014 the IAEA reported about ongoing reconstructions at Parchin military base. The Agency has anticipated that these activities will further undermine its ability to conduct effective verification if and when this location would be open for inspection.[134] A month later, The New York Times reported that according to a statement by Yukiya Amano, the IAEA Director General, Iran had stopped answering the Agency's questions about suspected past weaponization issues. Iran has argued that what has been described as evidence is fabricated.[135] In his speech at Brookings Institution Yukiya Amano said that progress has been limited and two important practical measures, which should have been implemented by Iran two months ago, have still not been implemented. Mr. Amano stressed his commitment to work with Iran "to restore international confidence in the peaceful nature of its nuclear programme". But he also warned: "this is not a never-ending process. It is very important that Iran fully implements the Framework for Cooperation - sooner rather than later."[136]

On 16 June 2015 U.S. Secretary John Kerry told reporters that the possible military dimensions problem was a little distorted, since the U.S. was "not fixated on Iran specifically accounting for what they did" and the U.S. had "absolute knowledge" with respect to this issue.[137] CNN reminded that according to the framework deal Iran "will implement an agreed set of measures to address the IAEA's concerns" about the PMD. It also reported that about two months ago Secretary Kerry told PBS that Iran had to disclose its past military-related nuclear activities and this "will be part of a final agreement".[138]

الجدل حول إصدار خامنئي أصدر فتوى ضد إنتاج الأسلحة النووية

At an August 2005 meeting of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) in Vienna, the Iranian Government asserted that Ali Khamenei has issued a fatwa declaring that the production, stockpiling and use of nuclear weapons is forbidden under Islam.[139] In a 2015 interview with Thomas Friedman of The New York Times, President Obama cited Khamenei's purported Fatwa "that they will not have a nuclear weapon."[140]

Doubts have been cast by some experts from U.S. or Israeli-affiliated think tanks on either the existence of the fatwa, its authenticity or impact.[141] The Iranian official website for information regarding its nuclear program documents numerous instances of public statements by Khamenei wherein he voices his opposition to pursuit and development of nuclear weapons in moral, religious and Islamic juridical terms.[142] Khamenei's official website specifically cites a 2010 statement, in which Khamenei says "We consider the use of [nuclear] weapons as haraam[forbidden]"[143] of these statements in the fatwa section of the website in Farsi as a fatwa on "Prohibition of Weapons of Mass Destruction."[144] Ayatollah Ali Khamenei also declared that the United States created the myth nuclear weapons in order to show Iran as a threat.[145]

Fact checker Glenn Kessler of The Washington Post took a look at the Fatwa question. He notes that in Shiite tradition, oral and written opinions carry equal weight, so the lack of a written Fatwa is not necessarily dispositive. He also notes that while Khamenei said in 2005 that "production of an atomic bomb is not on our agenda," more recently he has said the use of nuclear weapons is forbidden, while saying nothing about their development. Kessler sums up by saying that even if one believes the Fatwa does exist, it appears to have changed over time, and refused to give a verdict on the truth of the matter.[146]

The negotiations on the Comprehensive agreement on the Iranian nuclear program have been accompanied by an extensive debate over whether or not such an agreement is a good idea. Prominent supporters include President Barack Obama. Prominent opponents include Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, former Secretaries of State Henry Kissinger and George P. Shultz, and Democratic Senator Bob Menendez.[147][148][149][150]

جدل حول ما تعنيه الصفقة بالنسبة لخطر الحرب

Obama has argued that failure of the negotiations would increase the chance of a military confrontation between the United States and Iran.[151] In an interview with Thomas Friedman, Obama argued that an agreement would be the best chance to ease tensions between the US and Iran.[147]

Opponents have countered that the proposed deal would concede to Iran a vast nuclear infrastructure, giving it the status of a threshold nuclear state. They argue that rivals such as Saudi Arabia would likely counter by becoming threshold nuclear states themselves, leading to an inherently unstable situation with multiple rival near-nuclear powers. They argue that such a situation would heighten the risk of war and even the risk of nuclear war.[149][152][153]

الجدل حول ما إذا كانت الاتفاقية ستعزز التعاون

Iran's foreign minister Mohammad Javad Zarif argued in The New York Times that the framework agreed on in April, 2015 would end any doubt that Iran's nuclear program is peaceful. Zarif also argued that a deal would open the way to regional cooperation based on respect for sovereignty and noninterference in the affairs of other states.[154][155]

Opponents such as Schultz, Kissinger, and Netanyahu are skeptical of promises of cooperation. Netanyahu argued that Iran's "tentacles of terror" were threatening Israel, and an Iranian nuclear bomb would "threaten the survival of my country." He pointed to tweets from Ali Khamenei calling for the destruction of Israel. He said that any agreement with Iran should include an end of Iranian aggression against its neighbors and recognition of Israel.[148][156] For their part, Schultz and Kissinger note a lack of evidence of Iranian cooperation to date.[149]

الجدل حول البدائل

Supporters of a deal with Iran have said that opponents do not offer a viable alternative, or that the only alternative is war.[147] Netanyahu argued that the alternative to the deal currently being negotiated is a better deal, because, he said, Iran needs a deal more than the West does. Other opponents have argued that a war is in fact the best option for the West, as, they say, sanctions have historically failed to stop nuclear programs.[148][157]

البلدان المتفاوضة

الصين

ووانگ يي، وزير الخارجية

فرنسا

لوران فابيوس، وزير الخارجية

'ألمانيا

فرانك-ڤالتر شتاينماير، وزير الخارجية

إيران

محمد جواد ظريف ، وزير الخارجية

روسيا

سرگي لاڤروڤ، وزير الخارجية

المملكة المتحدة

فلپ هاموند، وزير الخارجية

الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية

جون كري، وزير الخارجية

مواقف البلدان الغير متفاوضة

Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia fears that a deal with Iran could come at expense of Sunni Arabs. U.S. President Barack Obama paid a visit to Riyadh in March 2014 and assured King Abdullah that he is determined to stop Iran from getting a nuclear weapon and that the United States would not accept a bad deal. However, an editorial in Al Riyadh newspaper claimed that the president did not know Iran as the Saudis did, and could not convince them that Iran will be peaceful.[159]

In 2015, a report in the Sunday Times quoted unnamed senior U.S. officials asserting that Saudi Arabia had made the decision to buy a nuclear weapon from Pakistan, due to anger among Sunni Arab states at the Iran deal, which they feared would allow Iran to get a nuclear weapon.[160]

إسرائيل

إسرائيل

بعد التوصل إلى الاتفاق، هاتف رئيس الوزراء بنيامين نتانياهو الرئيس الأمريكي باراك أوباما لبحث الاتفاق، مصدرًا بيانًا بعد المكالمة جاء فيه "اتفاقية تقوم على اتفاق إطاري كهذا تهدد وجود إسرائيل..البديل هو الوقوف بحزم وزيادة الضغوط على إيران حتى يجري التوصل لاتفاق أفضل."[161]

| Israel's requests on the Lausanne agreement[162] |

|---|

| Unspecified reduction in the number of centrifuges. |

| End to all alleged nuclear military development activity. |

| Reduce Iran's stockpile of enriched uranium to nil (or ship all the stockpile abroad). |

| No enrichment to be allowed at Fordow. |

| Obtain overall picture of all past nuclear research activities within Iran. |

| Unrestricted inspection of all suspected facilities by the IAEA. |

| Iranian recognition of Israel's right to exist[163][164] |

ردود الفعل على وسائل التواصل الاجتماعي

لا تهدد إيران أبداً

انظر أيضاً

- Negotiations on Iran nuclear deal framework

- Iran and weapons of mass destruction

- Aerospace Force of the Army of the Guardians of the Islamic Revolution

- Timeline of the nuclear program of Iran

- Views on the nuclear program of Iran

- Sanctions against Iran

المصادر

- ^ Haidar, J. I., 2015. "Sanctions and Exports Deflection: Evidence from Iran" Archived 30 يوليو 2017 at the Wayback Machine, Paris School of Economics, University of Paris 1 Pantheon Sorbonne, Mimeo

- ^ "Iran, world powers reach historic nuclear deal" Archived 7 يناير 2018 at the Wayback Machine, The Washington Post

- ^ "IAEA Head Reports Status of Iran's Nuclear Programme". International Atomic Energy Agency. 20 January 2014. Archived from the original on 26 February 2014. Retrieved 23 February 2014.

- ^ أ ب Louis Charbonneau & Parisa Hafezi (18 July 2014). "Iran, powers extend talks after missing nuclear deal deadline". Reuters. Archived from the original on 19 July 2014. Retrieved 19 July 2014. خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صالح؛ الاسم "reuters18072014" معرف أكثر من مرة بمحتويات مختلفة. - ^ أ ب Lee, Matthew; Jahn, George (24 نوفمبر 2014). "Iran nuclear talks to be extended until July". Associated Press. Archived from the original on 29 نوفمبر 2014. Retrieved 24 نوفمبر 2014.

- ^ Pamela Dockins (30 June 2015). "Iran Nuclear Talks Extended Until July 7". Voice of America. Archived from the original on 1 July 2015. Retrieved 30 June 2015.

- ^ Implementation of the NPT Safeguards Agreement in Iran - 23 May 2014, p. 15.

- ^ Iran, Country Profiles, Nuclear - NTI.

- ^ Jethro Mullen & Nic Robertson, "Landmark deal reached on Iran nuclear program", CNN (14 July 2015).

- ^ Michael R. Gordon & David E. Sanger, "Deal Reached on Iran Nuclear Program; Limits on Fuel Would Lessen With Time", The New York Times (14 July 2015).

- ^ "Iran, world powers reach historic nuclear deal", The Washington Post

- ^ "IAEA Head Reports Status of Iran's Nuclear Programme". International Atomic Energy Agency. 20 January 2014. Retrieved 23 February 2014.

- ^ Dockins, Pamela (30 June 2015). "Iran Nuclear Talks Extended Until July 7". Voice of America. Retrieved 30 June 2015.

- ^ Richter, Paul (7 July 2015). "Iran nuclear talks extended again; Friday new deadline". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 8 July 2015.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Karen DeYoung & Carol Morello, "The path to a final Iran nuclear deal: Long days and short tempers", The Washington Post (15 July 2015).

- ^ Jethro Mullen and Nic Robertson, CNN (14 July 2015). "Landmark deal reached on Iran nuclear program". CNN.

{{cite news}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ "European Union – EEAS (European External Action Service) – Joint statement by EU High Representative Federica Mogherini and Iranian Foreign Minister Javad Zarif Vienna, 14 July 2015". Europa (web portal).

- ^ أ ب ت خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةBroadLetter - ^ "Public Statement on U.S. Policy Toward the Iran Nuclear Negotiations Endorsed by a Bipartisan Group of American Diplomats, Legislators, Policymakers, and Experts", Washington Institute for Near East Policy (24 June 2015).

- ^ Perkovich, George; Hibbs, Mark; Acton, James M.; Dalton, Toby (8 August 2015). "Parsing the Iran Deal". Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

- ^ Laurence Norman and Jay Solomon (9 November 2013). "Iran Nuclear Talks End Without Deal". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 10 November 2013.

- ^ "Positive Iran-P5+1 talks in Almaty, Israel's total defeat: Report". Presstv.ir. 11 March 2013. Retrieved 24 November 2013.

- ^ World powers and Iran make 'good start' towards nuclear accord Reuters

- ^ Ravid, Barak (20 June 2014). "Iran: World powers 'unrealistic' in demands over nuclear program, big gaps remain". Haaretz. Retrieved 21 June 2014.

- ^ Rozen, Laura (June 20, 2014). "Iran, US say 'difficult decisions' ahead to advance nuclear talks". Al-Monitor. Retrieved 21 June 2014.

- ^ "Final round of Iran nuclear talks starts in Vienna". BBC Online. 3 July 2014. Retrieved 4 July 2014.

- ^ "New Round of Iran Nuclear Talks Faces Old Hurdles". ABC News. Associated Press. 19 September 2014. Retrieved 25 September 2014.

- ^ "Iran, P5+1 begins new round of nuclear talks in New York". Press TV. 20 September 2014. Retrieved 25 September 2014.

- ^ "Iran, six major powers start new round of nuclear talks". China Internet Information Center. 20 September 2014. Retrieved 25 September 2014.

- ^ "Nuclear Calendar 2014". Friends Committee on National Legislation. 25 September 2014. Retrieved 25 September 2014.

- ^ James Reynolds (16 October 2013). "BBC News - Iran nuclear checks most detailed ever - Ashton". Bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 24 November 2013.

- ^ "FM Cautions West against Miscalculations about Iran's N. Program". Fars News Agency. 12 November 2014. Retrieved 13 November 2014.

- ^ "Iran, world powers fight to save nuclear deal". Agence France-Presse. 11 November 2014. Retrieved 13 November 2014.

- ^ "Nuclear negotiations end in Muscat". Radio Zamaneh. 12 November 2014. Retrieved 13 November 2014.

- ^ "Nuclear Talks Resume With Iran in Vienna". NASDAQ. 18 November 2014. Retrieved 20 November 2014.

- ^ "German FM optimistic about N-talks progress". Mehr News Agency. 19 November 2014. Retrieved 20 November 2014.

- ^ "Zarif: Objective, reaching agreement in shortest possible time". IRNA. 25 November 2014. Retrieved 25 November 2014.

- ^ John Kerry (24 November 2014). "Solo Press Availability in Vienna, Austria". United States Department of State. Retrieved 25 November 2014.

- ^ Marina Depetris (17 December 2014). "Iran calls nuclear talks 'very useful'; next meeting in Jan". Reuters. Retrieved 19 December 2014.

- ^ "'Good Steps' taken at Nuclear talks". Iran Daily. 17 December 2014. Retrieved 19 December 2014.

- ^ Umid Niayesh (19 January 2015). "Iran, P5+1 to hold next round of nuclear talks in February". Trend News Agency. Retrieved 20 January 2015.

- ^ Stephanie Nebehay and Marina Depetris (18 January 2015). "Iran, powers make 'limited' progress at nuclear talks, to meet in February". Reuters. Retrieved 20 January 2015.

- ^ "Russian Deputy FM Says Major Disagreements Remain in Iran Nuclear Talks". Sputnik News. 19 January 2015. Retrieved 20 January 2015.

- ^ "No Iran, P5+1 Talks on Tehran's Nuclear Program Expected Monday - Source". Sputnik News. 23 February 2015. Retrieved 2 March 2015.

- ^ "Iran, P5+1 Talks on Tehran Nuclear Program Constructive - French Envoy". Sputnik News. 23 February 2015. Retrieved 2 March 2015.

- ^ THOMAS ERDBRINK (2015-04-03). "Iran's Leaders Begin Tricky Task of Selling Nuclear Deal at Home". النيويورك تايمز.

- ^ "Iran to abide by its promises if P5+1 group fulfills its obligations: Rouhani". Press TV. 2015-04-03.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةalmonitor05162014 - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةafp08102014 - ^ "Zarif specifies sticking points in Iran nuclear talks". Tehran Times. 22 July 2014. Archived from the original on 22 August 2014. Retrieved 25 August 2014.

- ^ David E. Sanger (13 July 2014). "Americans and Iranians See Constraints at Home in Nuclear Negotiations". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 18 July 2014. Retrieved 25 August 2014.

- ^ "Iran needs 190,000 nuclear centrifuges". Channel NewsAsia. 8 July 2014. Archived from the original on 21 August 2014. Retrieved 25 August 2014.

- ^ John Irish (10 June 2014). "France says Iran must budge on centrifuges for talks to succeed". Reuters. Archived from the original on 10 June 2014. Retrieved 10 June 2014.

- ^ Scott Ritter (2 April 2015). "A Good Deal, a Long Time Coming". The Huffington Post. Archived from the original on 12 July 2015. Retrieved 15 July 2015.

- ^ William O. Beeman (31 October 2013). "Does Iran Have the Right to Enrich Uranium? The Answer Is Yes". The Huffington Post. Archived from the original on 12 July 2015. Retrieved 15 July 2015.

- ^ Paul K. Kerr (28 April 2014). "Iran's Nuclear Program: Tehran's Compliance with International Obligations" (PDF). Congressional Research Service. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 April 2015. Retrieved 16 August 2014.

- ^ أ ب ت Katzman, Kenneth (30 June 2014). "Iran: U.S. Concerns and Policy Responses" (PDF). Congressional Research Service. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 August 2014. Retrieved 2 August 2014.

- ^ A Justified Extension for Iran Nuclear Talks, chpt. Iran's Negotiating Positions Have Undergone "Rights Creep".

- ^ أ ب Michael Singh (March 2014). "The Case for Zero Enrichment in Iran". Arms Control Association. Archived from the original on 22 August 2014. Retrieved 21 August 2014.

- ^ أ ب Robert J. Einhorn (March 2014). "Preventing a nuclear-armed Iran: Requirements for a Comprehensive Nuclear Agreement" (PDF). Brookings Institution. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 January 2015. Retrieved 14 October 2014.

- ^ Michael Singh (18 October 2013). "The straight path to a nuclear deal with Iran". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 21 August 2014. Retrieved 19 August 2014.

- ^ أ ب Colin H. Kahl (13 November 2013). "Examining Nuclear Negotiations: Iran After Rouhani's First 100 Days" (PDF). Center for a New American Security. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 September 2014. Retrieved 19 August 2014.

- ^ Robert Joseph (7 August 2014). "The Path Ahead for a Nuclear Iran". Arms Control Association. Archived from the original on 21 August 2014. Retrieved 21 August 2014.

- ^ Colin H. Kahl (13 May 2014), panel discussion "The Rubik's Cube™ of a Final Agreement" at YouTube, Retrieved 25 August 2014.

- ^ Robert J. Einhorn (13 May 2014), panel discussion "The Rubik's Cube™ of a Final Agreement" at YouTube, Retrieved 25 August 2014.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةinstituteofpeace07292014 - ^ John Kerry (10 December 2013). "The P5+1's First Step Agreement With Iran on its Nuclear Program". United States Department of State. Archived from the original on 21 January 2017. Retrieved 1 September 2014.

- ^ Rebecca Shimoni Stoil (29 January 2014). "Obama: I will veto any new Iran sanctions bill". The Times of Israel. Archived from the original on 8 June 2014. Retrieved 1 September 2014.

- ^ Fred Fleitz (30 May 2014), "The IAEA and Iran's Continuing Nuclear Deception" at YouTube, Retrieved 1 September 2014.

- ^ Ali Akbar Salehi (7 February 2014), "Press TV's Exclusive With Iran's Nuclear Chief (P.2)" at YouTube, Retrieved 1 September 2014.

- ^ "Plutonium Production". Federation of American Scientists. Archived from the original on 3 فبراير 2009. Retrieved 1 سبتمبر 2014.

- ^ Iran's Arak Reactor and the Plutonium Bomb.

- ^ "The Post's View: Final Iran deal needs to balance out the concessions". The Washington Post. 28 November 2013. Archived from the original on 24 October 2014. Retrieved 14 October 2014.

- ^ Gregory S. Jones (5 May 2014). "Preventing Iranian Nuclear Weapons—Beyond the "Comprehensive Solution"". Nonproliferation Policy Education Center. Archived from the original on 21 August 2014. Retrieved 21 August 2014.

- ^ Barbara Slavin (31 March 2014). "Obama administration confidant lays out possible Iran nuclear deal". Al Jazeera America. Archived from the original on 18 October 2014. Retrieved 14 October 2014.

- ^ Defining Iranian Nuclear Programs in a Comprehensive Solution, p. 7.

- ^ أ ب "Implementation of the NPT Safeguards Agreement and relevant provisions of Security Council resolutions in the Islamic Republic of Iran" (PDF). International Atomic Energy Agency. 8 November 2011. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 October 2014. Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- ^ Evaluating a Nuclear Deal with Iran, p. 18–19.

- ^ أ ب ت William H. Tobey (19 June 2014). "Testimony before the House Armed Service Committee on the Iran Nuclear Negotiations". Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs. Archived from the original on 2 October 2014. Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- ^ أ ب "Iran: Nuclear Intentions and Capabilities" (PDF). U.S. National Intelligence Council. November 2007. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 November 2014. Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- ^ Blocking All Paths to an Iranian Bomb, p. 1–6, 13.

- ^ Evaluating a Nuclear Deal with Iran, p. 30.

- ^ Verification Requirements for a Nuclear Agreement with Iran, p. 5, 9–11, 15–18.

- ^ Blocking All Paths to an Iranian Bomb, p. 3–4, 13.

- ^ Evaluating a Nuclear Deal with Iran, p. 29-31.

- ^ Verification Requirements for a Nuclear Agreement with Iran, p. 4.

- ^ أ ب "Glossary - Additional Protocol". Nuclear Threat Initiative. Archived from the original on 14 September 2014. Retrieved 13 September 2014.

- ^ Nuclear Iran: A Glossary of Terms, p. 4.

- ^ Tehran's Compliance with International Obligations, p. 3, 6.

- ^ أ ب "IAEA, Iran Sign Joint Statement on Framework for Cooperation". International Atomic Energy Agency. 11 November 2013. Archived from the original on 14 September 2014. Retrieved 13 September 2014.

- ^ "Implementation of the NPT Safeguards Agreement and relevant provisions of Security Council resolutions in the Islamic Republic of Iran" (PDF). International Atomic Energy Agency. 20 February 2014. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 25 November 2014.

- ^ "IAEA and Iran Conclude Talks in Connection with Implementation of Framework for Cooperation". International Atomic Energy Agency. 9 February 2014. Archived from the original on 15 August 2014. Retrieved 13 September 2014.

- ^ "Joint Statement by Iran and IAEA". International Atomic Energy Agency. 21 May 2014. Archived from the original on 14 September 2014. Retrieved 13 September 2014.

- ^ Iran, Country Profiles, Nuclear - NTI, chpt. The Joint Plan of Action and Framework for Cooperation.

- ^ Implementation of the NPT Safeguards Agreement in Iran - 5 September 2014, chpt. J. Additional Protocol.

- ^ Solving the Iranian Nuclear Puzzle, chpt. Text of the Joint Plan of Action.

- ^ "Summary of Technical Understandings Related to the Implementation of the Joint Plan of Action on the Islamic Republic of Iran's Nuclear Program". whitehouse.gov. 16 January 2014. Archived from the original on 22 January 2017. Retrieved 13 September 2014 – via National Archives.

- ^ Evaluating a Nuclear Deal with Iran, p. 10.

- ^ The P5+1 and Iranian Joint Plan of Action, chpt. Verification Mechanisms and Transparency and Monitoring.

- ^ George Jahn (3 September 2014). "APNewsBreak: UN's Iran nuclear probe stalls again". Associated Press. Archived from the original on 14 September 2014. Retrieved 13 September 2014.

- ^ David Albright (9 February 2014). "Expert on Iran's nuclear program David Albright in an interview with PBS". PBS. Archived from the original on 14 September 2014. Retrieved 13 September 2014.

- ^ Implementation of the NPT Safeguards Agreement in Iran - 5 September 2014, chpt. B. Clarification of Unresolved Issues.

- ^ "Iran won't accept nuclear restraints 'beyond IAEA rules'". Agence France-Presse. 17 أغسطس 2014. Archived from the original on 14 سبتمبر 2014. Retrieved 13 سبتمبر 2014.

- ^ "Iran refuses UN nuclear watchdog access to Parchin base". Agence France-Presse. 23 أغسطس 2014. Archived from the original on 14 سبتمبر 2014. Retrieved 13 سبتمبر 2014.

- ^ Fredrik Dahl (3 September 2014). "IAEA report expected to show little headway in Iran nuclear investigation". Reuters. Archived from the original on 14 September 2014. Retrieved 13 September 2014.

- ^ Barbara Slavin (September 2014). "IAEA report on past Iranian nuke research may hamstring deal". Al-Monitor. Archived from the original on 14 September 2014. Retrieved 13 September 2014.

- ^ "Iran, IAEA fail to agree on two issues of Tehran's nuclear program". ITAR-TASS. 9 October 2014. Archived from the original on 10 October 2014. Retrieved 9 October 2014.

- ^ "Implementation of the NPT Safeguards Agreement and relevant provisions of Security Council resolutions in the Islamic Republic of Iran" (PDF). International Atomic Energy Agency. 19 February 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 March 2015. Retrieved 24 March 2015.

- ^ David Albright (24 March 2015). "Testimony of David Albright before U.S. House Subcommittee on the Middle East and North Africa" (PDF). Institute for Science and International Security. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 24 March 2015.

- ^ Solving the Iranian Nuclear Puzzle, p. 9.

- ^ Steven A. Hildreth (6 December 2012). "Iran's Ballistic Missile and Space Launch Programs" (PDF). Congressional Research Service. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 February 2017. Retrieved 18 October 2014.

- ^ Evaluating a Nuclear Deal with Iran, p. 12, 23–24.

- ^ أ ب Michael Singh (19 June 2014). "P5+1 Nuclear Negotiations with Iran and Their Implications for United States Defense" (PDF). Washington Institute for Near East Policy. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 December 2014. Retrieved 5 November 2014.

- ^ Yaakov Lappin (25 October 2014). "No indication at all of Iranian reversal on nuclear ambitions, expert tells 'Post'". The Jerusalem Post. Archived from the original on 3 November 2014. Retrieved 5 November 2014.

- ^ أ ب Joint Plan of Action.

- ^ أ ب Including Ballistic Missiles in Negotiations.

- ^ The Gulf Military Balance. Volume II, p. 116-117.

- ^ "Iran Makes the Rules". The Wall Street Journal. 29 September 2014. Archived from the original on 30 September 2014. Retrieved 30 September 2014.

- ^ "TEXT-Executive Summary of U.N. Panel of Experts report on Iran sanctions". Reuters. 12 May 2014. Archived from the original on 12 July 2015. Retrieved 21 October 2014.

- ^ Behnam Ben Taleblu (25 August 2014). "Don't Forget Iran's Ballistic Missiles". War On The Rocks. Archived from the original on 22 October 2014. Retrieved 21 October 2014.

- ^ Jay, Solomon (18 February 2014). "Iran Nuclear Talks Turn to Missiles". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 11 June 2014. Retrieved 12 May 2014.

- ^ Fredrik Dahl (11 May 2014). "U.N. nuclear watchdog, Iran to meet before 15 May deadline for progress". Reuters. Archived from the original on 12 May 2014. Retrieved 12 May 2014.

- ^ "Khamenei: Iran's Revolutionary Guards should mass produce missiles". The Jerusalem Post. 11 May 2014. Archived from the original on 12 May 2014. Retrieved 12 May 2014.

- ^ "US accepts Shahab-3s in Iran's missile arsenal, but not long-range ICBMs. Deep resentment in Jerusalem". Debkafile. 18 May 2014. Retrieved 19 May 2014.[dead link]

- ^ Senate Committee on Armed Services 30 January 2015.

- ^ Nima Gerami (13 June 2014). "Background on the 'Possible Military Dimensions' of Iran's Nuclear Program". Washington Institute for Near East Policy. Archived from the original on 19 October 2014. Retrieved 3 November 2014.

- ^ The Gulf Military Balance. Volume II, p. 86-87, 91-101.

- ^ The Gulf Military Balance. Volume II, p. 110.

- ^ Mark Hibbs (19 فبراير 2014). "Deconstructing Sherman on PMD". Arms Control Wonk. Archived from the original on 3 نوفمبر 2014. Retrieved 3 نوفمبر 2014.

- ^ Gary C. Gambill (يونيو 2014). "A Limited Disclosure Nuclear Agreement with Iran: Promise or Peril?". Foreign Policy Research Institute. Archived from the original on 9 نوفمبر 2014. Retrieved 3 نوفمبر 2014.

- ^ "354 House Members Express Concern about Iran's Refusal to Cooperate with International Nuclear Inspectors". United States House Committee on Foreign Affairs, Chairman Ed Royce. 2 October 2014. Archived from the original on 3 November 2014. Retrieved 3 November 2014.

- ^ "Weaponization-Related R&D". Institute for Science and International Security. June 2013. Archived from the original on 3 November 2014. Retrieved 3 November 2014.

- ^ The Gulf Military Balance. Volume II, p. 131.

- ^ Implementation of the NPT Safeguards Agreement in Iran - 5 September 2014, chpt. H. Possible Military Dimensions.

- ^ David E. Sanger (31 October 2014). "U.N. Says Iran Is Silent on Efforts for a Bomb". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 3 November 2014. Retrieved 3 November 2014.

- ^ Yukiya Amano (31 October 2014). "Challenges in Nuclear Verification: The IAEA's Role on the Iranian Nuclear Issue". International Atomic Energy Agency. Archived from the original on 3 November 2014. Retrieved 3 November 2014.

- ^ John Kerry (16 June 2015). "Secretary Kerry's Press Availability". United States Department of State. Archived from the original on 21 January 2017. Retrieved 17 June 2015.

- ^ Elise Labott (16 June 2015). "Iran likely to score concession from West on nuclear deal". CNN. Archived from the original on 16 June 2015. Retrieved 17 June 2015.

- ^ "Iran, holder of peaceful nuclear fuel cycle technology". Mathaba.net, IRNA. 25 أغسطس 2005. Archived from the original on 10 أغسطس 2013. Retrieved 13 أغسطس 2013.

- ^ Thomas Friedman. "Iran and the Obama doctrine". Video at 20:50. Archived from the original on 1 March 2017. Retrieved 3 March 2017.

- ^ "Iran says nuclear fatwa exists; others don't buy it". USA Today. 4 October 2013. Archived from the original on 5 September 2014. Retrieved 31 January 2015.

- ^ "Legal Aspects–Fatwa against Nuclear Weapons". nuclearenergy.ir. Archived from the original on 16 February 2015.

- ^ "Supreme Leader's Message to International Conference on Nuclear Disarmament". The center for preserving and publishing the works of Grand Ayatollah Sayyed Ali Khamenei. 17 أبريل 2010. Archived from the original on 12 نوفمبر 2013.

- ^ "حرمت سلاح کشتار جمعی". Official Website of Ayatollah Khamenei–Fatwas Section. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 15 July 2015.

- ^ "Ayatollah Ali Khamenei accuses US of creating Iran nuclear weapons 'myth'". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 26 June 2015. Retrieved 15 July 2015.

- ^ Glenn Kessler. "Did Iran's supreme leader issue a Fatwa against the development of nuclear weapons?". Archived from the original on 27 May 2016. Retrieved 7 January 2020.

- ^ أ ب ت Thomas L. Friedman. "Iran and the Obama Doctrine". Archived from the original on 25 February 2017. Retrieved 3 March 2017.

- ^ أ ب ت "The complete transcript of Netanyahu's address to Congress". Archived from the original on 21 July 2015. Retrieved 7 January 2020.

- ^ أ ب ت Henry Kissinger & George P. Schultz. "The Iran Deal and Its Consequences". Archived from the original on 5 March 2017. Retrieved 10 March 2017.

- ^ "Dem Sen. Menendez: Obama Statements on Iran "Sound Like Talking Points Straight Out Of Tehran"". Archived from the original on 2 June 2015. Retrieved 16 July 2015.

- ^ "War threat on Iran 'heightened' if nuclear talks fail, Obama warns". Archived from the original on 16 July 2015. Retrieved 16 July 2015.

- ^ "Saudi Arabia considers Nuclear Weapons to offset Iran". Archived from the original on 28 February 2017. Retrieved 10 March 2017.

- ^ Gabriel Scheinmann. "Obama's Nuclear Deal Could Mean War". Archived from the original on 9 July 2015. Retrieved 16 July 2015.

- ^ Mohammed Zarif. "A Message from Iran". Archived from the original on 1 March 2017. Retrieved 3 March 2017.

- ^ "Iran's Zarif: It's time for US to choose between cooperation and confrontation". Archived from the original on 16 July 2015. Retrieved 16 July 2015.

- ^ Peter Baker. "In Congress, Netanyahu Faults 'Bad Deal' on Iran Nuclear Program". Archived from the original on 25 February 2017. Retrieved 3 March 2017.

- ^ "War with Iran is probably our best option". Archived from the original on 24 December 2019. Retrieved 7 January 2020.

- ^ "تير مچگيري كوچك زاده از ظريف به سنگ خورد" (in الفارسية). Etemaad. 3 September 2015. p. 3.

- ^ Jeff Mason & Steve Holland (28 March 2014). "Obama seeks to reassure Saudi Arabia over Iran, Syria". Reuters. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 20 July 2014.

- ^ Tobi Harnden & Christina Lamb. "Saudis to get nuclear weapons". Archived from the original on 22 May 2015. Retrieved 15 July 2015.

- ^ .

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةWSJ - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةedition.cnn.com - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةhaaretz.com - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةbbc

قراءات إضافية ووصلات خارجية

كتب

- Henry Kissinger (2014). World Order. Penguin Group. ISBN 978-0-698-16572-4. Archived from the original on 2014-10-21.

- Anthony H. Cordesman and Bryan Gold (2014). The Gulf Military Balance. Volume II: The Missile and Nuclear Dimensions. CSIS, Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1-4422-2793-4.

- CS1 errors: generic name

- Articles with dead external links from April 2019

- CS1 الفارسية-language sources (fa)

- Articles containing فارسية-language text

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- جميع المقالات الحاوية على عبارات مبهمة

- جميع المقالات الحاوية على عبارات مبهمة from April 2015

- Vague or ambiguous time from April 2015

- Articles with unsourced statements from April 2015

- مقالات ذات عبارات بحاجة لمصادر

- 2015 في العلاقات الدولية

- 2015 في إيران

- مؤتمرات دبلوماسية في سويسرا

- العلاقات الخارجية لإيران

- العلاقات الأمريكية الإيرانية

- البرنامج النووي الإيراني

- الطاقة النووية في إيران

- سياسة إيران

- السياسة الخارجية لإدارة باراك أوباما

- مؤتمرات دبلوماسية في النمسا