العقوبات الدولية أثناء الحرب الأوكرانية الروسية

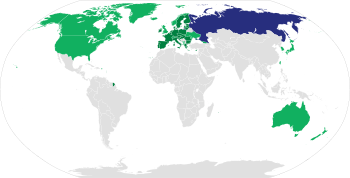

فُرضت العقوبات الدولية أثناء الحرب الروسية الأوكرانية من قبل عدد كبير من الدول ضد روسيا والقرم في أعقاب الغزو الروسي لأوكرانيا، الذي بدأ في أواخر فبراير 2014، حيث فرض العقوبات من قبل الولايات المتحدة والاتحاد الأوروپي ودول أخرى والمنظمات الدولية ضد الأفراد والشركات والمسؤولين من روسيا وأوكرانيا.[1] ردت روسيا بفرض عقوبات على عدد من البلدان، بما في ذلك الحظر التام على الواردات الغذائية من أستراليا وكندا والنرويج واليابان والولايات المتحدة والاتحاد الأوروپي.

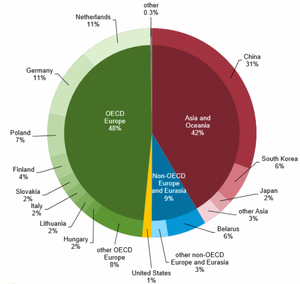

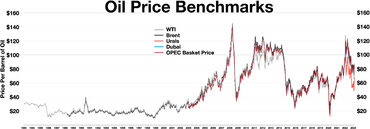

ساهمت العقوبات في انهيار الروبل الروسي والأزمة المالية الروسية.[2] كما تسببت في أضرار اقتصادية لعدد من دول الاتحاد الأوروپي، حيث قدرت الخسائر بإجمالي 100 مليار يورو (اعتبارًا من عام 2015).[3] اعتبارًا من عام 2014، أعلن وزير المالية الروسي أن العقوبات كلفت روسيا 40 مليار دولار، مع خسارة 100 مليار دولار أخرى في 2014 نظراً لانخفاض سعر النفط في العام نفسه بسبب وفرة النفط التي شهدها عقد 2010.[4] في أعقاب العقوبات الأخيرة التي فُرضت في أغسطس 2018، بلغت الخسائر الاقتصادية التي تكبدتها روسيا حوالي 0.5-1.5% من نمو الناتج المحلي الإجمالي. اتهم الرئيس الروسي ڤلاديمير پوتن الولايات المتحدة بالتآمر مع السعودية لتعمد إضعاف الاقتصاد الروسي من خلال خفض سعر النفط.[5] بحلول منتصف 2016، خسرت روسيا ما يقدر بنحو 170 مليار دولار بسبب العقوبات المالية، بالإضافة إلى 400 مليار دولار أخرى من العائدات المفقودة من النفط والغاز.[6] وفقًا لمسؤولين أوكرانيين، [أ]}} فرضت العقوبات على روسيا لتغيير نهجها تجاه أوكرانيا وتقويض التقدم العسكري الروسي في المنطقة.[7][8] يقول ممثلو هذه الدول إنهم لن يرفعوا العقوبات عن روسيا إلا بعد تنفيذ موسكو لاتفاقات مينسك 2.[9][10][11]

تستمر عقوبات الاتحاد الأوروپي والولايات المتحدة سارية المفعول اعتبارًا من فبراير 2022.[12][13] في يناير 2022، أعلن الاتحاد الأوروپي عن آخر تمديد للعقوبات حتى 31 يوليو 2022.[14]

في أعقاب الغزو الروسي لأوكرانيا في أواخر فبراير 2022، فرضت الولايات المتحدة والاتحاد الأوروپي ودول أخرى عقوبات، أو وسعتها بشكل كبير، لتشمل ڤلاديمير پوتن وأعضاء آخرين في الحكومة الروسية؛ وعزل البلاد عن نظام سويفت، مما أدى إلى الأزمة المالية الروسية 2022.[15][16][17][18][19]

خلفية

رداً على ضم روسيا الاتحادية للقرم، فرضت بعض الحكومات والمنظمات الدولية، بقيادة الولايات المتحدة والاتحاد الأوروپي، عقوبات على أفراد وشركات روسية. مع توسع الاضطرابات في مناطق أخرى من أوكرانيا الشرقية، وتصاعدت لاحقًا إلى الحرب في منطقة دونباس، زاد نطاق العقوبات. بشكل عام، فُرضت ثلاثة أنواع من العقوبات: حظر توفير التكنولوجيا للتنقيب عن النفط والغاز، وحظر تقديم ائتمانات لشركات النفط الروسية وبنوك الدولة، وقيود السفر على المواطنين الروس المؤثرين المقربين من الرئيس پوتن والمتورطين في ضم القرم.[20] ردت الحكومة الروسية بالمثل، بفرض عقوبات على بعض الأفراد الكنديين والأمريكيين، وفي أغسطس 2014 فرضت حظرًا تامًا على الواردات الغذائية من الاتحاد الأوروپي والولايات المتحدة والنرويج وكندا وأستراليا.[21]

عقوبات على أفراد وشركات ومسئولين روس وأوكران

الجولة الأولى: مارس/أبريل 2014

في 6 مارس 2014، مستشهداً "من بين أمور أخرى"، "بقانون الصلاحيات الاقتصادية الطارئة الدولية" و"قانون الطوارئ الوطنية"، وقع الرئيس الأمريكي]] باراك أوباما على أمر تنفيذي بإعلان حالة طوارئ وطنية وإصدار أوامر بفرض عقوبات، بما في ذلك حظر السفر وتجميد الأصول الأمريكية، ضد أفراد لم يتم تحديدهم بعد والذين "أكدوا سلطة حكومية في منطقة القرم الاذتية دون تفويض من حكومة أوكرانيا "والتي اعتبرت أفعالهم "تقويض للعمليات والمؤسسات الديمقراطية في أوكرانيا".[22][23]

في 17 مارس 2014، فرضت الولايات المتحدة والاتحاد الأوروپي وكندا عقوبات مستهدفة،[24][25][26] في اليوم التالي لاستفتاء شبه جزيرة القرم وقبل ساعات قليلة من توقيع الرئيس الروسي ڤلاديمير پوتن مرسومًا يعترف بشبه جزيرة القرم كدولة مستقلة، مما يضع الأساس لضم روسيا لشبه جزيرة القرم. هدفت عقوبة الاتحاد الأوروپي الرئيسية إلى "منع الدخول إلى أراضيها.. الأشخاص الطبيعيون المسؤولون عن أعمال تقوض ... وحدة أراضي ... لأوكرانيا، والأشخاص الطبيعيين المرتبطين بهم، على النحو الوارد في الملحق".[24] وفرض الاتحاد الأوروپي عقوباته "في غياب خطوات تهدئة من جانب روسيا الاتحادية" من أجل إنهاء العنف في أوكرانيا الشرقية. وأوضح الاتحاد الأوروپي في الوقت نفسه أنه "يظل مستعدًا لعكس قراراته وإعادة الانخراط مع روسيا عندما يبدأ في المساهمة بنشاط ودون غموض في إيجاد حل للأزمة الأوكرانية".[27] كانت عقوبات 17 مارس هذه هي أكثر العقوبات المستخدمة ضد روسيا نطاقًا منذ انهيار الاتحاد السوڤيتي عام 1991.[28] كما أعلنت اليابان عقوبات ضد روسيا، والتي تضمنت تعليق المحادثات المتعلقة بالمسائل العسكرية، والفضاء، والاستثمار، ومتطلبات التأشيرة.[29] بعد بضعة أيام، وسعت الحكومة الأمريكية العقوبات.[30]

في 19 مارس، فرضت أستراليا عقوبات على روسيا بعد ضمها لشبه جزيرة القرم. استهدفت هذه العقوبات التعاملات المالية وحظر السفر على أولئك الذين لعبوا دورًا أساسيًا في التهديد الروسي لسيادة أوكرانيا.[31] وسعت أستراليا عقوباتها في 21 مايو.[32]

في أوائل أبريل، فرضت ألبانيا وآيسلندا والجبل الأسود، وكذلك أوكرانيا نفس القيود وحظر السفر التي فرضها الاتحاد الأوروپي في 17 مارس.[33] صرح وزير خارجية الجبل الأسود إيگور لوكشيتش أن على الرغم من العلاقات الجيدة مع روسيا منذ قرون، فإن الانضمام إلى الاتحاد الأوروپي في فرض العقوبات "كان دائمًا الخيار المعقول الوحيد".[34] في وقت سابق من شهر مارس، فرضت مولدوڤا نفس العقوبات على رئيس أوكرانيا السابق ڤيكتور يانوكوڤيتش وعدد من المسؤولين الأوكرانيين السابقين، كما أعلن الاتحاد الأوروپي في 5 مارس.[35] ردًا على العقوبات التي فرضتها الولايات المتحدة والاتحاد الأوروپي، أصدر مجلس الدوما بالإجماع قرارًا يطالب بإدراج جميع أعضاء مجلس الدوما في قائمة العقوبات. [بحاجة لمصدر] تم توسيع العقوبات لتشمل رجال وسيدات أعمال روس بارزين بعد أيام قليلة.[36]

الجولة الثانية: أبريل 2014

في 10 أبريل، علق مجلس أوروپا حقوق التصويت للوفد الروسي.[37]

في 28 أبريل، فرضت الولايات المتحدة حظرًا على المعاملات التجارية داخل أراضيها على سبعة مسؤولين روس، من بينهم إيگور ستشين، الرئيس التنفيذي لشركة النفط الحكومية الروسية روس نفط، و17 شركة روسية.[38] في نفس اليوم، أصدر الاتحاد الأوروپي حظر سفر على 15 شخصًا آخرين.[39] وذكر الاتحاد الأوروپي أيضًا أن أهداف عقوبات الاتحاد الأوروپي هي:

العقوبات ليست عقابية، ولكنها مصممة لإحداث تغيير في السياسة أو النشاط من قبل البلد المستهدف أو الكيانات أو الأفراد. لذلك، تستهدف التدابير دائمًا مثل هذه السياسات أو الأنشطة، ووسائل إجرائها والمسؤولين عنها. في الوقت نفسه، يبذل الاتحاد الأوروپي قصارى جهده لتقليل العواقب الوخيمة على السكان المدنيين أو الأنشطة المشروعة.[40]

الجولة الثالثة: 2014–2021

2014

ردًا على الحرب في دونباس المتصاعدة، في 17 يوليو 2014 مددت الولايات المتحدة حظر صفقاتها ليشمل اثنتين من كبرى شركات الطاقة الروسية، روس نفط ونوڤاتيك، وإلى بنكين، گازپرومبنك وڤنشىإكينومبنك.[41] كما حثت الولايات المتحدة زعماء الاتحاد الأوروپي على الانضمام إلى الموجة الثالثة من العقوبات[42] ودفع الاتحاد الأوروپي للبدء في صياغة عقوبات أوروپية في اليوم السابق. [43][44] في 25 يوليو، وسع الاتحاد الأوروپي رسميًا عقوباته لتشمل 15 فردًا إضافيًا و18 كيانًا،[45] تلاه ثمانية أفراد وثلاثة كيانات أخرى في 30 يوليو.[46] في 31 يوليو 2014، قدم الاتحاد الأوروپي الجولة الثالثة من العقوبات التي تضمنت حظرًا على الأسلحة والمواد ذات الصلة، وحظرًا على السلع والتكنولوجيا ذات الاستخدام المزدوج المخصصة للاستخدام العسكري أو المستخدم النهائي العسكري، وحظرًا على واردات الأسلحة والمواد ذات الصلة، وضوابط تصدير المعدات لصناعة النفط، وفرض قيود على إصدار وتداول بعض السندات، حقوق الملكية أو الأدوات المالية المماثلة بتاريخ استحقاق أكبر من 90 يومًا (في سبتمبر 2014 تم تخفيضها إلى 30 يومًا)[47]

في 24 يوليو 2014، استهدفت كندا الأسلحة الروسية والكيانات المالية والطاقة.[48] في 5 أغسطس 2014، جمدت اليابان أصول "الأفراد والجماعات الداعمة لفصل شبه جزيرة القرم عن أوكرانيا" وقيدت الواردات من شبه جزيرة القرم. قامت اليابان أيضًا بتجميد الأموال المخصصة لمشاريع جديدة في روسيا تماشيًا مع سياسة البنك الأوروپي للإنشاء والتعمير.[49] في 8 أغسطس 2014، أعلن رئيس الوزراء الأسترالي توني أبوت أن أستراليا "تعمل من أجل" تشديد العقوبات ضد روسيا، والتي ينبغي تنفيذها في الأسابيع المقبلة.[50][51] في 12 أغسطس 2014، تبنت النرويج عقوبات أكثر صرامة ضد روسيا والتي فرضها الاتحاد الأوروپي والولايات المتحدة في 12 أغسطس 2014. على الرغم من أن النرويج ليست جزءًا من الاتحاد الأوروپي، إلا أن وزير الخارجية النرويجي [[بورگ بريندى] ] قالت إنها ستفرض قيودًا مماثلة لعقوبات الاتحاد الأوروپي في 1 أغسطس. سيتم حظر البنوك المملوكة للدولة الروسية من الحصول على قروض طويلة ومتوسطة الأجل، وسيتم حظر صادرات الأسلحة، وسيتم حظر إمدادات المعدات والتكنولوجيا والمساعدة لقطاع النفط الروسي.[52] في 14 أغسطس 2014، وسعت سويسرا العقوبات المفروضة على روسيا بسبب تهديدها لسيادة أوكرانيا. أضافت الحكومة السويسرية 26 روسيًا وأوكرانيًا مواليًا لروسيا إلى قائمة المواطنين الروس الخاضعين للعقوبات والتي تم الإعلان عنها لأول مرة بعد ضم روسيا لشبه جزيرة القرم.[53] في 27 أغسطس 2014، وسعت سويسرا عقوباتها ضد روسيا. قالت الحكومة السويسرية إنها توسع الإجراءات لمنع الالتفاف على العقوبات المتعلقة بالوضع في أوكرانيا لتشمل الجولة الثالثة من العقوبات التي فرضها الاتحاد الأوروپي في يوليو. صرحت الحكومة السويسرية أيضًا أن 5 بنوك روسية (سبربنك، VTB، Vnesheconombank (VEB)، گازپرومبنك و[روسيلكوز بنك|روسيلكوز]]) سيتطلب إذنًا لإصدار أدوات مالية طويلة الأجل في سويسرا.[54] في 28 أغسطس 2014، عدلت سويسرا عقوباتها لتشمل العقوبات التي فرضها الاتحاد الأوروپي في يوليو.[54]

في 14 أغسطس 2014، أصدرت أوكرانيا قانونًا يفرض عقوبات أوكرانية على روسيا.[55][56] يشمل القانون 172 فردًا و65 كيانًا في روسيا ودول أخرى لدعم وتمويل "الإرهاب" في أوكرانيا، على الرغم من أن العقوبات الفعلية ستحتاج إلى موافقة من مجلس الأمن القومي والدفاع الأوكراني.

On 11 September 2014, US President Obama said that the United States would join the EU in imposing tougher sanctions on Russia's financial, energy and defence sectors.[57] On 12 September 2014, the United States imposed sanctions on Russia's largest bank (Sberbank), a major arms maker and arctic (Rostec), deepwater and shale exploration by its biggest oil companies (Gazprom, Gazprom Neft, Lukoil, Surgutneftegas and Rosneft). Sberbank and Rostec will have limited ability to access the US debt markets. The sanction on the oil companies seek to ban co-operation with Russian oil firms on energy technology and services by companies including Exxon Mobil Corp. and BP Plc.[58]

On 24 September 2014, Japan banned the issue of securities by 5 Russian banks (Sberbank, VTB, Gazprombank, Rosselkhozbank and development bank VEB) and also tightened restrictions on defence exports to Russia.[59]

On 3 October 2014, US Vice President Joe Biden said that "It was America's leadership and the president of the United States insisting, oft times almost having to embarrass Europe to stand up and take economic hits to impose costs" and added that "And the results have been massive capital flight from Russia, a virtual freeze on foreign direct investment, a ruble at an all-time low against the dollar, and the Russian economy teetering on the brink of recession. We don't want Russia to collapse. We want Russia to succeed. But Putin has to make a choice. These asymmetrical advances on another country cannot be tolerated. The international system will collapse if they are."[60]

On 18 December 2014, the EU banned some investments in Crimea, halting support for Russian Black Sea oil and gas exploration and stopping European companies from purchasing real estate or companies in Crimea, or offering tourism services.[61] On 19 December 2014, US President Obama imposed sanctions on Russian-occupied Crimea by executive order prohibiting exports of US goods and services to the region.[62]

2015

On 16 February 2015, the EU increased its sanction list to cover 151 individuals and 37 entities.[63] Australia indicated that it would follow the EU in a new round of sanctions. If the EU sanctioned new Russian and Ukrainian entities then Australia would keep their sanctions in line with the EU.[بحاجة لمصدر]

On 18 February 2015, Canada added 37 Russian citizens and 17 Russian entities to its sanction list. Rosneft and the deputy minister of defence, Anatoly Antonov, were both sanctioned.[64][65] In June 2015 Canada added three individuals and 14 entities, including Gazprom.[66] Media suggested the sanctions were delayed because Gazprom was a main sponsor of the 2015 FIFA Women's World Cup then concluding in Canada.[67]

In September 2015, Ukraine sanctioned more than 388 individuals, over 105 companies and other entities. In accordance with the August 2015 proposals promulgated by the Security Service of Ukraine and the Order of the Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine No. 808-p dated 12 August 2015, Ukraine, on 2 September 2015, declared Russia an enemy of Ukraine. Also on 16 September 2015, Ukraine President Petro Poroshenko issued a decree that named nearly 400 individuals, more than 90 companies and other entities to be sanctioned for the Russia's "criminal activities and aggression against Ukraine."[68][69][70][71]

الجولة الرابعة: 2022

After Russia invaded Ukraine on 24 February 2022, two countries that had not previously taken part in sanctions, namely South Korea[72] and Taiwan[73], engaged in sanctions against Russia. On 28 February 2022, Singapore announced that it will impose banking sanctions against Russia for Ukraine invasion, thus making them the first country in Southeast Asia to impose sanctions to Russia;[74] the move was described by the South China Morning Post as being "almost unprecedented".[75]

العقوبات ضد القرم

The United States, Canada, the European Union and other European countries (including Ukraine) imposed economic sanctions specifically targeting Crimea. Sanctions prohibit the sale, supply, transfer, or export of goods and technology in several sectors, including services directly related to tourism and infrastructure. They list seven ports where cruise ships cannot dock.[76][77][78][79] Sanctions against Crimean individuals include travel bans and asset freezes. Visa and MasterCard have stopped service in Crimea between December 2014 and April 2015.[بحاجة لمصدر]

In September 2016 Pursuant to Executive Order 13685, OFAC designated Russian shipping company Sovfracht-Sovmortrans Group and its subsidiary, Sovfracht for operating in Crimea.[80]

العقوبات على احتجاز أوكران في روسيا

في أبريل 2016، عاقبت لتوانيا 46 فردًا كانوا متورطين في احتجاز وإصدار أحكام بحق المواطنين الأوكرانيين ناديا ساڤشينكو وأوليه سنتسوڤ وأولكساندر كولتشنكو. قال وزير الخارجية اللتواني ليناس لينكڤيوس إن بلاده تريد "تركيز الانتباه على الانتهاكات غير المقبولة والساخرة للقانون الدولي وحقوق الإنسان في روسيا. [...] سيكون الأمر أكثر فاعلية إذا أصبحت القائمة السوداء على مستوى أوروپا نأمل أن نبدأ مثل هذا النقاش".[81]

الجولة الحادية عشر: يونيو 2023

Since April 2014, the European Union has applied eleven rounds of sanctions against the Russian Federation. The most recent 11th round of sanctions in June 2023 focused on dual-use items, including computer chips, and as well as an attempt to limit ship-to-ship transactions of sanctioned goods. More suspensions of Russian broadcasting licenses in Europe were also announced.[82] The U.S. government has urged American companies to halt shipments to over 600 foreign entities amid concerns of diversion to Russia for use in its Ukraine invasion, part of ongoing efforts to restrict Russian access to Western technology. Assistant Secretary Matthew Axelrod emphasized outreach to more than 20 companies and collaboration with senior officials to prevent American-made goods from ending up in Russia.[83]

The most recent measures included transport measures, including a full ban on Russian trucks and semi-trailers, limitations on ship-to-ship transfer taking place in the Exclusive Economic Zone of a member state or within 12 nautical miles from the baseline of that member state's coast, a total ban on Russian pipeline oil transfers through the northern branch of the Druzhba pipeline to Germany and Poland, new export and export restrictions on Russia's defense materials as well as goods and technology suited for use in the aerospace industry and jet fuel and fuel additives. Sanctions were also imposed on Russian intellectual property rights and their transfer as well as new criteria on sanctions in the Russian IT-sector with a license issued by the Russian Federal Security Service (FSB) and the Russian Ministry of Industry and Trade.[84]

النفط

في 1 مارس 2022 قدم السيناتور روجر مارشال مشروع قانون يحظر استيراد الولايات المتحدة من النفط الروسي، ودعم المشروع زعيم الأقلية في الحزب الجمهوري بلجنة مجلس الشيوخ للطاقة والموارد الطبيعية وسبعة جمهوريين آخرين. قبلها بيوم فرضت كندا حظراً على النفط الروسي. وقال رئيس الوزراء الكندي جاستن ترودو حينها أن الحظر "يبعث برسالة قوية".[86][87]

في 8 مارس، أمر الرئيس جو بايدن بفرض حظر على واردات النفط والغاز والفحم من روسيا إلى الولايات المتحدة.[88]

في 2 سبتمبر 2022، وافقت مجموعة الدول السبع على تحديد سعر النفط الروسي من أجل تقليل قدرة روسيا على تمويل حربها مع أوكرانيا دون زيادة التضخم.[89]وانضم إليها الاتحاد الأوروبي وأستراليا، ودخلت العقوبات حيز التنفيذ في 5 ديسمبر 2022.[90] واعتباراً من 5 فبراير 2023، دخل قرار تحديد سقف لأسعار المنتجات النفطية الروسية حيز التنفيذ.

فيما حظر الاتحاد الأوروبي جميع واردات المنتجات النفطية المكررة من روسيا في فبراير 2023، وحظرت المملكة المتحدة واردات النفط الروسية اعتباراً من ديسمبر 2022.[91]وانخفضت واردات الاتحاد الأوروبي من النفط عن طريق السفن من 1.2 مليون برميل يوميا إلى أقل من 0.1 مليون برميل.[92]

وبلغت إيرادات النفط والغاز الروسية للربع الأول من عام 2023 1.6 تريليون روبل (19.61 مليار دولار)، وهو أقل بكثير من ميزانية عام 2023 البالغة 8.9 تريليون روبل (35 مليار دولار) لكل ربع وإيرادات 2022 التي بلغ متوسطها 42 مليار دولار لكل ربع.[93][94]

ناقلات النفط

في 16 نوفمبر 2023، فرضت وزارة الخزانة الأمريكية عقوبات على الشركات والسفن البحرية لتزويدها بالنفط الروسي المباع بأكثر من الحد الأقصى لسعر مجموعة السبع. واستهدفت العقوبات ثلاث شركات تابعة لشركات مقرها الإمارات، بما في ذلك Kazan Shipping Incorporated وProgress Shipping Company Limited وGalion Navigation Incorporated، والتي يُزعم أنها تصدر النفط الخام الروسي بأكثر من 60 دولاراً للبرميل. وبحسب ما ورد كانت السفن الإماراتية تستخدم أفراداً أمريكيين لنقل النفط الخام الروسي.[95] وبعد هذه الحزمة من العقوبات توقفت كل مصافي التكرير الهندية عن شراء النفط الروسي المنقول على متن ناقلات شركة الشحن الروسية "سوفكومفلوت" (Sovcomflot)، خشية الوقوع تحت طائلة العقوبات.

كما أعلنت شركة "ريلاينس إندستريس" الهندية (Reliance Industries)، المالكة لأكبر مجمع تكرير في العالم، أنها لن تشتري النفط القادم من روسيا عبر شركة سوفكومفلوت. وبحسب بيانات رصدتها منصة الطاقة المتخصصة، انخفض حجم الصادرات الروسية عبر أسطول الشركة التي تديرها الحكومة حتى قبل الخطوة الهندية، وكانت الشركة قد نقلت خلال 2023، نحو خُمس صادرات النفط الروسي.[96]

Banking

In a 22 February speech,[97] US president Joe Biden announced restrictions against four Russian banks, including V.E.B., as well as on corrupt billionaires close to Putin.[98][99] UK prime minister Boris Johnson announced that all major Russian banks would have their assets frozen and be excluded from the UK financial system, and that some export licences to Russia would be suspended.[100] He also introduced a deposit limit for Russian citizens in UK bank accounts, and froze the assets of over 100 additional individuals and entities.[101]

The foreign ministers of the Baltic states called for Russia to be cut off from SWIFT, the global messaging network for international payments. Concern was expressed in Europe because European lenders held most of the nearly $30 billion in foreign banks' exposure to Russia and because China had developed an alternative to SWIFT called CIPS; a weaponisation of SWIFT would provide greater impetus to the development of CIPS which, in turn, could weaken SWIFT.[102][103] Other leaders calling for Russia to be stopped from accessing SWIFT include Czech president Miloš Zeman,[104] and UK prime minister Boris Johnson.[105] On 26 February, the German foreign minister Annalena Baerbock and economy minister Robert Habeck made a joint statement backing targeted restrictions of Russia from SWIFT.[106][107] Shortly thereafter, it was announced that major Russian banks would be removed from SWIFT, although there would still be limited accessibility to ensure the continued ability to pay for gas shipments.[108]

It was also announced that the West would place sanctions on the Russian Central Bank, which holds $630bn in foreign reserves, to prevent it from liquidating assets to offset the impact of sanctions.[110]

On 26 February, two Chinese state banks—the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China, which is the largest bank in the world, and the Bank of China, which is the country's biggest currency trader—were limiting financing to purchase Russian raw materials, which was limiting Russian access to foreign currency.[111] On 28 February, Switzerland and Monaco froze a number of Russian assets and joined EU sanctions. According to Ignazio Cassis, the president of the Swiss Confederation, the decision was unprecedented but consistent with Swiss neutrality.[112][113]

Singapore became the first Southeast Asian country to impose sanctions on Russia by restricting banks and transactions linked to Russia;[115] the move was described by the South China Morning Post as being "almost unprecedented".[116]

On 28 February, Japan announced that its central bank would join sanctions by limiting transactions with Russia's central bank.[117] The Central Bank of Russia was blocked from accessing more than $400 billion in foreign-exchange reserves held abroad.[118][119] Sergei Aleksashenko, the former Russian deputy finance minister, said: "This is a kind of financial nuclear bomb that is falling on Russia."[120] EU foreign affairs chief Josep Borrell said that Western governments "cannot block the reserves of the Russian central bank in Moscow or in China".[121]

On 1 March, the French finance minister Bruno Le Maire said that Russian assets being frozen by sanctions amounted to $1 trillion.[122] South Korea announced it would stop all transactions with 7 main Russian banks and their affiliates, restrict the purchase of Russian treasury bonds, and agreed to "immediately implement" and join any further economics sanctions imposed against Russia by the European Union.[123][124]

Following sanctions and criticisms of their relations with Russian business, many companies chose to exit Russian or Belarusian markets voluntarily or in order to avoid potential future sanctions.[125] Visa, Mastercard, and American Express independently blocked Russian banks as of 2 March.[126] Following Swiss sanctions on Russia, Credit Suisse issued orders to destroy documents linking Russian oligarchs to yacht loans, a move which led to considerable criticism.[127]

In July 2023 Russia attempted to get the SWIFT ban partially lifted by making it a condition to extending the Black Sea Grain Initiative.[128]

The ruble

In 2013 there were around 35 rubles to the US dollar. Following the seizure of Crimea and sanctions starting, the ruble fell. In 2015–2019 it traded in the 60–70 range. In 2020–2021 it moved to the 70-80 range and since the 2022 invasion of Ukraine and a large increase in sanctions, it has slowly declined to reach 100 in August 2023.[129]

Dual-use ban

The US instituted export controls, a novel sanction focused on restricting Russian access to high-tech components, both hardware and software, made with any parts or intellectual property from the US. The sanction required that any person or company that wanted to sell technology, semiconductors, encryption software, lasers, or sensors to Russia request a licence, which by default was denied. The enforcement mechanism involved sanctions against the person or company, with the sanctions focused on the shipbuilding, aerospace, and defence industries.[130][131]

معارضة العقوبات

Italy, Hungary, Greece, France, Cyprus and Slovakia are among the EU states most skeptical about the sanctions and have called for review of sanctions.[132] The Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán stated that Europe "shot itself in the foot" by introducing economic sanctions.[133] Bulgarian Prime Minister Boyko Borisov stated, "I don't know how Russia is affected by the sanctions, but Bulgaria is affected severely";[134] Czech President Miloš Zeman[135][بحاجة لمصدر أفضل] and Slovakian Prime Minister Robert Fico[136] also said that the sanctions should be lifted. In October 2017, the Hungarian Minister of Foreign Affairs and Trade Péter Szijjártó added that the sanctions "were totally unsuccessful because Russia is not on its knees economically, but also because there have been many harms to our own economies and, politically speaking, we have had no real forward progress regarding the Minsk agreement".[137]

In 2015, the Greek Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras repeatedly said that Greece would seek to mend ties between Russia and EU through European institutions. Tsipras also said that Greece was not in favour of Western sanctions imposed on Russia, adding that it risked the start of another Cold War.[138]

A number of business figures in France and Germany have opposed the sanctions.[139][140][141] The German Economy Minister Sigmar Gabriel said that the Ukrainian crisis should be resolved by dialogue rather than economic confrontation,[142] later adding that the reinforcement of anti-Russian sanctions will "provoke an even more dangerous situation… in Europe".[143]

Paolo Gentiloni, Italian Minister of Foreign Affairs, said that the sanctions "are not the solution to the conflict".[144] In January 2017, Swiss Economics Minister and former President of Switzerland Johann Schneider-Ammann stated his concern about the sanctions' harm to the Swiss economy, and expressed hope that they will soon come to an end.[145] Some companies, most notably Siemens Gas Turbine Technologies LLC and Lufthansa Service Holding were reported to attempt bypassing the sanctions and exporting power generation turbines to the annexed Crimea.[146]

In August 2015, the British think tank Bow Group released a report on sanctions, calling for the removal of them. According to the report, the sanctions have had "adverse consequences for European and American businesses, and if they are prolonged... they can have even more deleterious effects in the future"; the potential cost of sanctions for the Western countries has been estimated as over $700 billion.[147]

In June 2017, Germany and Austria criticized the U.S. Senate over new sanctions against Russia that target the planned Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline from Russia to Germany,[148][149] stating that the United States was threatening Europe's energy supplies (see also Russia in the European energy sector).[150] In a joint statement Austria's Chancellor Christian Kern and Germany's Foreign Minister Sigmar Gabriel said that "Europe's energy supply is a matter for Europe, and not for the United States of America."[151] They also said: "To threaten companies from Germany, Austria and other European states with penalties on the U.S. market if they participate in natural gas projects such as Nord Stream 2 with Russia or finance them introduces a completely new and very negative quality into European-American relations."[152]

In May 2018, the vice chairman of Free Democratic Party of Germany and the Vice President of the Bundestag Wolfgang Kubicki said that Germany should "take a first step towards Russia with the easing of the economic sanctions" because "this can be decided by Germany alone" and "does not need the consent of others".[153]

In February 2019, advisor to Municipal Councilor of Municipality of Verona, member of House of Representatives Vito Comencini said that the anti-Russian sanctions have caused significant damage to the Italian economy, with the result that the country suffers losses every day in the amount of millions of euros.[154]

الجولة الخامسة 2024

في 23 فبراير 2024 أعلن الرئيس الأميركي جو بايدن حزمة عقوبات جديدة على روسيا وصفت بأنها الأكبر منذ بدء الحرب في أوكرانيا، وتضمنت إجراءات بحق أكثر من 500 شخص وكيان في دول عديدة.

وقال بايدن في بيان صدر عشية الذكرى الثانية لبدء الحرب إنه "إذا لم يدفع الرئيس الروسي فلاديمير بوتين ثمن الموت والدمار اللذين يتسبب فيهما فسيواصل أفعاله".

وأوضح أن العقوبات الجديدة تستهدف "قطاع روسيا المالي والبنية التحتية لصناعاتها الدفاعية وشبكات الإمداد وجهات الالتفاف على العقوبات عبر قارات عدة".

وأشار بايدن أيضا إلى استهداف أشخاص على صلة بوفاة المعارض الروسي أليكسي نافالني وأوضحت الخارجية الأميركية لاحقاً أن المستهدفين 3 مسؤولين روس.

وفي المجمل، استهدفت وزارتا الخزانة والخارجية بهذه الحزمة أكثر من 500 فرد وكيان قامت بتجميد أصولهم في الولايات المتحدة وتقييد حصولهم على تأشيرات الدخول، وبشكل منفصل أضافت وزارة التجارة 93 شركة إلى قائمة عقوباتها.

وتشمل القائمة الطويلة شركات تكنولوجيا في قطاعات أشباه الموصلات والمسيّرات وأنظمة المعلومات ومعهدين للرياضيات التطبيقية.

كما تشمل العقوبات نظام الدفع الروسي "مير" الذي تقول وزارة الخزانة الأميركية إنه مكّن موسكو من "بناء بنية تحتية مالية سمحت لها بالالتفاف على العقوبات وإعادة الصلات المقطوعة مع النظام المالي الدولي".

وببهذه الحزة من العقوبات، يرتفع عدد الجهات المستهدفة بالعقوبات الأميركية منذ بداية الحرب إلى أكثر من 4 آلاف.

وفي أول تعليق على الخطوة الأميركية، قال السفير الروسي في واشنطن أناتولي أنتونوف لوكالات الأنباء الرسمية إن "القيود الجديدة غير القانونية هي محاولة خبيثة أخرى للتدخل في الشؤون الداخلية للاتحاد الروسي".

وفي وقت متزامن اتفقت دول الاتحاد الأوروبي على الحزمة الـ13 من العقوبات على روسيا، كما اتخذت بريطانيا تدابير بحق أكثر من 50 شخصا وشركة.[155]

في 5 مارس 2024، أعلنت محطة نفط دورتيول التركية، وهي إحدى محطات النفط متوسطة الحجم في تركيا، وقف تداول الواردات الروسية، بعد تلقيها كميات قياسية عام 2023، وذلك وسط تصاعد ضغوط العقوبات الأمريكية.[156]

وقالت شركة گلوبال ترمينال سيرڤسيز (GTS) التي تدير المحطة الواقعة في محافظة هاتاي جنوب شرقي تركيا، أنها أبلغت عملاءها بأنها لن تقبل أي منتجات من روسيا. وصرحت الشركة لرويترز: "قررت شركة جي تي إس قطع جميع العلاقات المحتملة مع النفط الروسي، وأعلنت لعملائها وفقاً لذلك في أواخر فبراير (شباط) 2024، أنه حتى لو لم يكن هناك خرق لأي قوانين أو لوائح أو عقوبات، فإنها لن تقبل أي منتج من أصل روسي، أو أي منتجات يتم تحميلها من الموانئ الروسية كإجراء إضافي لقواعد العقوبات المعمول بها".

وأشارت إلى أن جميع العمليات السابقة كانت متوافقة تماماً مع العقوبات، بما في ذلك سقف أسعار مجموعة الدول السبع. وأضافت: "إن النهج الجديد الذي تتخذه الشركة هو إجراء إضافي للقضاء على آثار الأنشطة التي تخرج عن نطاقها وسيطرتها، على الرغم من الجهود المبذولة للالتزام بجميع العقوبات المطبقة".

منذ عام 2022 أصبحت تركيا واحدة من أكبر مستوردي الخام والوقود الروسي، بعد أن فرض الغرب عقوبات على موسكو بسبب غزوها لأوكرانيا. وردت روسيا بإعادة توجيه النفط بعيداً عن أوروپا والولايات المتحدة إلى آسيا وتركيا وأفريقيا. وأدى التهديد الأمريكي بفرض عقوبات على الشركات المالية التي تتعامل مع روسيا بالفعل، إلى تجميد التجارة التركية الروسية، مما أدى إلى تعطيل أو إبطاء بعض المدفوعات مقابل كل من النفط المستورد والصادرات التركية.

واستقبل ميناء دورتيول - الذي يستورد ويصدر ويخزن الوقود والنفط الخام - 11.74 مليون برميل من النفط الخام والوقود الروسي العام الماضي، وفقاً لبيانات شركة تحليلات الشن «كبلر». وأصبحت سابع أكبر محطة استيراد في تركيا من حيث الحجم، حيث ارتفعت من المركز العاشر عام 2021. وكانت واردات النفط والوقود الروسية في عام 2023 أعلى بنحو 7 مرات من إجمالي حجم البضائع التي تلقتها من جميع المصادر في 2021، وهو آخر عام كامل قبل غزو روسيا لأوكرانيا.

وارتفعت الصادرات من المحطة أيضاً عام 2023، حيث ارتفعت بأكثر من 5 مرات عن عام 2021، لتصل إلى نحو24.7 مليون برميل، وفقاً لـ«كبلر». وأظهرت بيانات كبلر أن آخر ناقلة قامت بالتفريغ في دورتيول وصلت في 19 فبراير، وشحنت حمولة ديزل تبلغ 511.000 برميل من ميناء بريمورسك الروسي، الواقع على بحر البلطيق.

وقالت جي تي إس إنها ستظل تقبل الشحنات الروسية التي تم ترشيحها قبل تنفيذ الحظر في أواخر فبراير. وشملت الوجهات الشائعة للنفط المصدر من دورتيول، موانئ كورنث وإيليوسيس وسالونيك اليونانية، ومراكز تداول وتكرير وتخزين النفط في شمال غربي أوروپا؛ وهي روتردام وأنتوِرپ. تجدر الإشارة إلى أن أنقرة تعارض العقوبات الغربية على موسكو، على الرغم من انتقادها غزو روسيا لأوكرانيا قبل عامين. وتمكنت من الحفاظ على علاقات وثيقة مع كل من موسكو وكييڤ.

جهود لرفع العقوبات

France announced in January 2016 that it wanted to lift the sanctions in mid-2016. Earlier, U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry mentioned a possible lifting of sanctions.[157]

In June 2016, the French Senate voted to urge its government to "gradually and partially" lift the EU sanctions on Russia, although the vote was non-binding.[158]

However, in September 2016, the EU extended its sanctions, for another six months, against Russian officials and pro-Moscow separatists in Ukraine.[159] An EU asset freeze on ex-Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovych was upheld by the bloc's courts.[159] On 13 March 2017, the EU extended the asset freeze and travel bans on 150 people until September 2017.[160] The sanctions include Yanukovych and senior members of his administration.[160]

As Trump's National Security Advisor, Michael T. Flynn was an important link in the connections between Putin and Trump in the "Ukraine peace plan", an unofficial plan "organized outside regular diplomatic channels....at the behest of top aides to President Putin". This plan, aimed at easing the sanctions imposed on Russia, progressed from Putin and his advisors to Ukrainian politician Andrey Artemenko, Felix Sater, Michael Cohen, and Flynn, where he would have then presented it to Trump. The New York Times reported that Sater delivered the plan "in a sealed envelope" to Cohen, who then passed it on to Flynn in February 2017, just before his resignation.[161]

On 19 June 2017, the EU again extended sanctions for another year that prohibit EU businesses from investing in Crimea, and which target tourism and imports of products from Crimea.[162]

In November 2017, the Secretary General of the Council of Europe Thorbjørn Jagland said that the Council of Europe considered lifting the sanctions on Russia due to concerns that Russia may leave the organization, which would be "a big step back for Europe".[163] Jagland was also criticized of "caving in to blackmail" by other Council members for his conciliatory approach to Russia.[163]

On 9 October 2018, the council's parliamentary assembly voted to postpone the decision on whether Russia's voting rights should be restored.[164]

On 8 March 2019, the Italian Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte stated that Italy is working on lifting the sanctions, which "the ruling parties in Rome say are ineffective and hurt the Italian economy".[165]

عقوبات أخرى على روسيا

الولايات المتحدة

In December 2012, the US enacted the Magnitsky Act, intended to punish Russian officials responsible for the death of Russian tax accountant Sergei Magnitsky in a Moscow prison in 2009 by prohibiting their entry to the US and use of its banking system.[166] 18 individuals were originally affected by the Act. In December 2016, Congress enacted the Global Magnitsky Act to allow the US Government to sanction foreign government officials implicated in human rights abuses anywhere in the world.[167] On 21 December 2017, 13 additional names were added to the list of sanctioned individuals, not just Russians. Other countries passed similar laws to ban foreigners deemed guilty of human rights abuses from entering their countries.

On 29 December 2016, the US President Barack Obama signed an Executive Order that expelled 35 Russian diplomats, locked down two Russian diplomatic compounds, and expanded sanctions against Russia for its interference in the 2016 United States elections.[168][169][170][171]

In August 2017, the US Congress enacted the Countering America's Adversaries Through Sanctions Act that imposed new sanctions on Russia for interference in the 2016 elections and its involvement in Ukraine and Syria. The Act converted the punitive measures previously imposed by Executive Orders into law to prevent the President easing, suspending or ending of sanctions without the approval of Congress.[172][173]

On 15 March 2018, Trump imposed financial sanctions under the Act on the 13 Russian government hackers and front organizations that had been indicted by Mueller's investigation into Russian interference in the 2016 United States elections.[174] On 6 April 2018, the United States imposed economic sanctions on seven Russian oligarchs and 12 companies they control, accusing them of "malign activity around the globe", along with 17 top Russian officials, the state-owned weapons-trading company Rosoboronexport and Russian Financial Corporation Bank (RFC Bank). High-profile names on the list include Oleg Deripaska and Kiril Shamalov, Putin's ex-son-in-law, who married Putin's daughter Katerina Tikhonova in February 2013. The press release stated: "Deripaska has been investigated for money laundering, and has been accused of threatening the lives of business rivals, illegally wiretapping a government official, and taking part in extortion and racketeering. There are also allegations that Deripaska bribed a government official, ordered the murder of a businessman, and had links to a Russian organized crime group."[175] Other names on the list include: Oil tycoon Vladimir Bogdanov, Suleiman Kerimov, who faces money-laundering charges in France for allegedly bringing hundreds of millions of euros into the country without reporting the money to tax authorities, Igor Rotenberg, principal owner of Russian oil and gas drilling company Gazprom Burenie, Andrei Skoch, a deputy in the State Duma. U.S. officials said he has longstanding ties to Russian organized criminal groups, Viktor Vekselberg, founder and chairman of the Renova Group, asset management company,[175][176] and Aleksandr Torshin.[177]

In August 2018 following the poisoning of Sergey Skripal,the U.S. Department of Commerce imposed further sanctions on dual-use exports to Russia which were deemed to be sensitive on national security grounds, including gas turbine engines, integrated circuits, and calibration equipment used in avionics. Until that moment, such exports were considered on a case-by-case basis. Following the introduction of these sanctions, the default position is of denial.[178] Also, on September that year a list of companies in the space and defense industry came under sanctions, including: AeroComposit, Divetechnoservices, Scientific-Research Institute "Vektor", Nilco Group, Obinsk Research and Production Enterprise, Aviadvigatel, Information Technology and Communication Systems (Infoteks), Scientific and Production Corporation of Precision Instruments Engineering and Voronezh Scientific Research Institute "Vega“, whom are forbidden from doing business with.[179]

In March 2019, the United States imposed sanctions on persons and companies involved in the Russian shipbuilding industry in response to the Kerch Strait incident: Yaroslavsky Shipbuilding Plant, Zelenodolsk Shipyard Plant, AO Kontsern Okeanpribor, PAO Zvezda (Zvezda), AO Zavod Fiolent (Fiolent), GUP RK KTB Sudokompozit (Sudokompozit), LLC SK Consol-Stroi LTD and LLC Novye Proekty. Also, the U.S. targeted persons involved in the 2018 Donbass general elections.[180]

On 2 August 2019, the U.S State Department announced additional sanctions together with an executive order signed by President Trump which gives the Department of Treasury and the Department of Commerce the authority to implement the sanctions. The sanctions forbid granting Russia loans or other assistance from international financial institutions, prohibition on U.S banks buy non-ruble denominated bonds issued by the Russia after 26 August and lending non-ruble denominated funds to Russia and licensing restrictions for exports of items for chemical and biological weapons proliferation reasons.[181]

In September 2019 pursuant to Executive Order 13685 Maritime Assistance LLC was placed under sanctions due to its export of fuel to Syria as well as for providing support to Sovfracht, another company sanctioned for operating in Crimea.[80][182] Later in the same month, the United States sanctioned two Russian citizens as well as three companies, Autolex Transport, Beratex Group and Linburg Industries in connection with the Russian interference in the 2016 United States election.[183]

المنظمات الدولية

في يناير 2018، فرض الاتحاد الأوروبي عقوبات على الكيانات التي شاركت في بناء جسر القرم: معهد گيپرسترويموست، الشركة التي صممت الجسر؛ موستوتريست، التي لديها عقد لصيانة الجسر؛ حوض زاليڤ لبناء السفن، الذي شيدت خط سكة حديد على الجسر؛ شركة سترويگازمونتاژ، شركة البناء الرئيسية التي بنت الجسر؛ شركة تابعة لشركة سترويگازمونتاژ تسمى سترويگازمونتاژ-موست -Most وVAD، والتي بنت الطريق فوق الجسر، بالإضافة إلى طرق الوصول.[184]

في مارس 2018، طردت 29 دولة غربية وحلف شمال الأطلسي ما لا يقل عن 149 دبلوماسيًا روسيًا، بما في ذلك 60 من قبل الولايات المتحدة، ردًا على تسميم سكريپال وابنته في 4 مارس بالمملكة المتحدة، والذي اتهمت به روسيا.[185] Other measures were also taken.

في 5 ديسمبر 2022، وفقًا للتقارير، أعاقت تركيا شحنات نفط من روسيا وقزخستان للسفن التي فشلت في تقديم دليل على التأمين على حمولتها بسبب الحد الأقصى الأخير لأسعار النفط الروسي لمجموعة السبع.[186]

اعتبارًا من 2 ديسمبر 2022، يتطلب من أي ناقلة تمر عبر مضيق البوسفور خطابًا من شركة التأمين الخاصة بها قبل الانتقال عبر المياه التي تسيطر عليها تركيا، وفقًا لبلومبرج نيوز.

تم تنفيذ هذا المطلب الجديد بعد أن قررت الدول الأعضاء في مجموعة السبع حداً أقصى لسعر برميل النفط الروسي يبلغ 60 دولاراً. التأمين هو دليل على الشراء يساوي أو أقل من 60 دولار للبرميل، حيث لا تستطيع تركيا استخدام نظام التحقق التقليدي لضمان تغطية البضائع بالتأمين.

تشمل اللائحة أي ناقلة تحمل النفط من البحر الأسود وليس فقط من روسيا. تنقل قزخستان حوالي 1.5 مليون برميل يوميًا عبر خط أنابيب بحر قزوين وتعتمد بشدة على مضيق البوسفور في عائداتها النفطية.

في 4 ديسمبر 2022، أعلنت الدول الأعضاء في أوبك+ أنها ستلتزم بأهداف الإنتاج الخاصة بها، مما يقلل الإمدادات بمقدار 2 مليون برميل يوميًا. استند قرار أوبك إلى عوامل اقتصادية مختلفة وإعلان دول مجموعة السبع مؤخرًا عن فرض حد أقصى لسعر النفط الروسي.

في غضون ذلك، قالت موسكو إنها لن تسلم النفط إلى أوروبا بعد الآن كرد على الحد الأقصى للسعر، بينما يزعم العديد من وزراء أوبك أن مثل هذه السياسة لن يكون لها أي تأثير، حيث تبيع روسيا معظم نفطها للأسواق الآسيوية.

أعلن الممثل الدائم لروسيا لدى المنظمات الدولية في فيينا ميخائيل أوليانوڤ على تويتر: "اعتبارًا من هذا العام، ستعيش أوروبا بدون النفط الروسي. لقد أوضحت موسكو بالفعل أنها لن تزود النفط لتلك الدول التي تدعم الحد الأقصى للسعر المناهض للسوق".

ذكرت رويترز أيضًا أن الخطوة التي اتخذها أعضاء مجموعة السبع أثارت قلق العديد من الدول الأعضاء في أوبك +، حيث إن الإجراءات "يمكن أن يستخدمها الغرب في النهاية ضد أي منتج".

العواقب والتقديرات

الأهمية السياسية

The economic sanctions imposed on Russia, serve as a tool of nonrecognition policy, by underscoring that the countries which impose these sanctions do not recognize Russian annexation of Crimea. Having these sanctions in place prevents the situation from being treated as a fait accompli.[187]

التأثير على روسيا

يُعتقد عمومًا أن العقوبات الاقتصادية ساعدت على إضعاف الاقتصاد الروسي بشكل طفيف وتكثيف التحديات التي كانت تواجهها روسيا.

اقترح تحليل بيانات عام 2015 دخول روسيا في حالة ركود، مع نمو سلبي للناتج المحلي الإجمالي بنسبة 2.2٪ للربع الأول من عام 2015، مقارنة بالربع الأول من 2014. علاوة على ذلك، فإن التأثير المشترك للعقوبات والانخفاض السريع في أسعار النفط عام 2014 تسبب في ضغط هبوطي كبير على قيمة الروبل وهروب رأس المال من روسيا. في الوقت نفسه، أجبرت العقوبات المفروضة على الوصول إلى التمويل روسيا على استخدام جزء من احتياطياتها من النقد الأجنبي لدعم الاقتصاد. أجبرت هذه الأحداث البنك المركزي الروسي على التوقف عن دعم قيمة الروبل وزيادة أسعار الفائدة.

يعتقد البعض أن الحظر الروسي على الواردات الغربية كان له تأثير إضافي على هذه الأحداث الصعبة حيث أدى الحظر إلى ارتفاع أسعار المواد الغذائية ومزيد من التضخم بالإضافة إلى آثار انخفاض قيمة الروبل الذي أدى بالفعل إلى ارتفاع أسعار السلع المستوردة.[188]

عام 2016، تجاوزت الزراعة صناعة الأسلحة كثاني أكبر قطاع تصدير في روسيا بعد النفط والغاز.[189]

التأثير على الولايات المتحدة وبلدان الاتحاد الأوروپي

اعتبارًا من عام 2015 ، قدرت خسائر الاتحاد الأوروبي بما لا يقل عن 100 مليار يورو.[3] أفاد قطاع الأعمال الألماني، الذي يضم حوالي 30 ألف مكان عمل يعتمد على التجارة مع الاتحاد الروسي، أنه قد تأثر بشكل كبير بالعقوبات.[190] أثرت العقوبات على العديد من قطاعات السوق الأوروبية، بما في ذلك الطاقة والزراعة،[191] والطيران وقطاعات أخرى.[192] في مارس 2016، صرح اتحاد المزارعين الفنلنديين MTK أن العقوبات الروسية وانخفاض الأسعار قد وضعت المزارعين تحت ضغط هائل. قدر معهد الموارد الطبيعية الفنلندي LUKE أن المزارعين شهدوا في العام الماضي انخفاضًا في دخولهم بنسبة 40 في المائة على الأقل مقارنة بالعام السابق.[193]

في فبراير 2015 ، أفادت إكسون موبيل بخسارة نحو مليار دولار بسبب العقوبات الروسية.[194]

عام 2017، نشر المقرر الخاص للأمم المتحدة إدريس الجزائري تقريرًا عن تأثير العقوبات، قال فيه إن دول الاتحاد الأوروبي تخسر نحو 3.2 مليار دولار شهريًا بسبب هذه العقوبات. كما أشار إلى أن العقوبات كانت "تهدف إلى أن تكون بمثابة رادع لروسيا ولكنها تخاطر بأن تكون مجرد رادع لمجتمع الأعمال الدولي، بينما تؤثر سلبًا فقط على الفئات الضعيفة التي لا علاقة لها بالأزمة" (خاصة الأشخاص في شبه جزيرة القرم، "لا ينبغي إجبارهم على الدفع بشكل جماعي مقابل أزمة سياسية معقدة لا سيطرة لهم عليها").[195][196][197]

العقوبات الروسية المضادة

بعد ثلاثة أيام من العقوبات الأولى ضد روسيا، في 20 مارس 2014، نشرت وزارة الخارجية الروسية قائمة بالعقوبات المتبادلة ضد بعض المواطنين الأمريكيين، والتي تتكون من عشرة أسماء، بما في ذلك رئيس مجلس النواب جون بوينر، السيناتور جون مكين، واثنان من مستشاري باراك أوباما. وقالت الوزارة في البيان، "معاملة بلادنا بهذه الطريقة، كما يمكن أن تكون واشنطن قد تأكدت بالفعل، غير مناسبة وتأتي بنتائج عكسية"، وأكدت أن العقوبات ضد روسيا سيكون لها تأثير بومرانگ.[بحاجة لمصدر] في 24 مارس، منعت روسيا ثلاثة عشر مسؤولاً كنديًا، بمن فيهم أعضاء في البرلمان الكندي، من دخول البلاد.[198]

في 6 أغسطس 2014، وقع پوتن مرسوماً "بشأن استخدام تدابير اقتصادية محددة"، يقضي بفرض حظر فعال لمدة عام على واردات معظم المنتجات الزراعية التي بلد المنشأ "اعتمدها قرار فرض عقوبات اقتصادية فيما يتعلق بالكيانات القانونية و(أو) المادية الروسية، أو الانضمام إليها".[199][200] في اليوم التالي، اعتمد ونشر مرسوم الحكومة الروسية بأثر فوري،[201] الذي حدد المواد المحظورة وكذلك دول المصدر: الولايات المتحدة والاتحاد الأوروبي والنرويج وكندا وأستراليا، بما في ذلك حظر استيراد الفواكه والخضروات واللحوم والأسماك والحليب ومنتجات الألبان. قبل الحظر، بلغت قيمة الصادرات الغذائية من الاتحاد الأوروبي إلى روسيا حوالي 11.8 مليار يورو، أو 10٪ من إجمالي صادرات الاتحاد الأوروبي إلى روسيا. بلغت قيمة الصادرات الغذائية من الولايات المتحدة إلى روسيا حوالي 972 مليون يورو. بلغت قيمة الصادرات الغذائية من كندا حوالي 385 مليون يورو. بلغت قيمة الصادرات الغذائية من أستراليا، وخاصة اللحوم والماشية الحية، حوالي 170 مليون يورو سنويًا.[202][203]

كانت روسيا قد اتخذت في السابق موقفًا بأنها لن تشارك في عقوبات "انتقامية ، ولكن عند إعلان الحظر، قال رئيس الوزراء الروسي دميتري مدڤييدڤ: "لا يوجد شيء جيد في العقوبات ولم تكن قرار سهل اتخاذه، لكن كان علينا القيام بذلك". وأشار إلى أنه يجري النظر أيضا في العقوبات المتعلقة بقطاع تصنيع النقل. قال المتحدث باسم وزارة الخزانة الأمريكية ديڤد كوهن إن العقوبات التي تؤثر على الوصول إلى الغذاء "ليست شيئًا تفعله الولايات المتحدة وحلفاؤها على الإطلاق".[204]

في اليوم نفسه، أعلنت روسيا حظر استخدام مجالها الجوي على الطائرات الأوكرانية.[202]

في يناير 2015، أصبح من الواضح أن السلطات الروسية لن تسمح عضو البرلمان الأوروبي، عضو البرلمان الأوروبي الليتواني گابريليوس لاندسبرگيس، بزيارة موسكو لأسباب سياسية.[205]

في مارس 2015، مُنعت عضوة البرلمان الأوروبي اللاتڤي ساندرا كالنيت ورئيس مجلس الشيوخ الپولندي وگدان بوروسڤيتز من دخول روسيا بموجب نظام العقوبات الحالي، وبالتالي لم يتمكنا من حضور جنازة السياسي المعارض المقتول وريس نيمتسوڤ.[206]

بعد منع عضو في البرلمان الألماني من دخول روسيا في مايو 2015، أصدرت روسيا قائمة سوداء لحكومات الاتحاد الأوروبي تضم 89 سياسيًا ومسؤولًا من الاتحاد الأوروبي غير مسموح لهم بالدخول إلى روسيا بموجب نظام العقوبات الحالي. طلبت روسيا عدم نشر القائمة السوداء علناً.[207] ويقال إن القائمة تضم ثمانية سويديين، بالإضافة إلى نائبين من هولندا.[208] نشرت هيئة الإذاعة الوطنية الفنلندية "Yle" نسخة ألمانية مسربة من القائمة.[209][210]

ردًا على هذا المنشور، علق السياسي البريطاني مالكولم ريفكيند (الذي كان اسمه مدرجًا في القائمة الروسية) قائلاً: "إنه يظهر أننا نحدث تأثيرًا لأنهم لم يكن لرد فعلهم إلا إذا شعروا بألم شديد مما حدث. بمجرد تمديد العقوبات، كان لها تأثير كبير على الاقتصاد الروسي. حدث هذا في وقت انهارت فيه أسعار النفط، وبالتالي اختفى المصدر الرئيسي لإيرادات السيد پتن. هذا مهم جدًا عندما يتعلق الأمر محاولاته لبناء قوته العسكرية وإجبار جيرانه على فعل ما قيل لهم". وأضاف: "إذا كان يجب أن يكون هناك مثل هذا الحظر، فأنا فخور جدًا بأن أكون عليه - سأكون منزعجًا إذا لم أفعل ذلك."[211] لاحظ شخص آخر على القائمة، وهو عضو البرلمان الأوروبي السويدي گونار هوكمارك، أنه فخور بكونه على القائمة وقال "النظام الذي يفعل ذلك يفعل ذلك لأنه خائف، وهو ضعيف القلب".[212]

فيما يتعلق بحظر دخول روسيا على السياسيين الأوروبيين، قال متحدث باسم الاتحاد الأوروبي: "القائمة التي تضم 89 اسمًا تمت مشاركتها الآن من قبل السلطات الروسية. وليس لدينا أي معلومات أخرى بشأن الأساس القانوني والمعايير وعملية هذا القرار. ونعتبر هذا الاجراء تعسفيا تماماً وغير مبرر خاصة في ظل غياب اي توضيح وشفافية".[213]

في 29 يونيو 2016، وقع الرئيس الروسي ڤلاديمير پوتن مرسوماً يمدد الحظر المفروض على البلدان التي تم فرض عقوبات عليها بالفعل حتى 31 ديسمبر 2017.[214]

وفقًا لدراسة أجريت عام 2020، لم تخدم العقوبات الروسية المضادة أهداف السياسة الخارجية لروسيا فحسب، بل سهّلت أيضًا السياسة الحمائية الروسية.[215] نتيجة للعقوبات المضادة، جنبًا إلى جنب مع الدعم الحكومي للإنتاج الزراعي المحلي، ازداد إنتاج الحبوب والدجاج ولحم الخنزير والجبن وغيرها من المنتجات الزراعية. انخفضت واردات روسيا من المواد الغذائية من 35٪ عام 2013 إلى 20٪ فقط عام 2018. كما ارتفعت أسعار هذه المنتجات بشكل كبير. في موسكو، من سبتمبر 2014 إلى سبتمبر 2018، ارتفع متوسط سعر الجبن بنسبة 23٪، والحليب بنسبة 35.7٪، والزيت النباتي بنسبة 65٪.[216]

تهريب النفط

في 24 يوليو 2022، تم تسليم شحنة تبلغ حوالي 700000 برميل من النفط الروسي إلى ميناء الحمرا البترولي في مصر على ساحل البحر الأبيض المتوسط في وقت وبعد بضع ساعات، جمعت سفينة أخرى شحنة من الميناء - والتي ربما تضمنت بعضًا أو كل البراميل الروسية - وفقًا لبيانات تتبع السفن التي رصدتها بلومبرگ.

هذه الخطوة غير العادية تجعل من الصعب تعقب الوجهة النهائية للشحنات، مما يزيد من التعتيم على اتجاه شحنات النفط الروسية بشكل متزايد منذ أن بدأ المشترون الأوروبيون في تجنبها بعد الغزو الروسي لأوكرانيا.

تمتلك شركة الحمرا، التي تديرها شركة بترول الصحراء الغربية المصرية، ستة صهاريج تخزين قادرة على استيعاب 1.5 مليون برميل من النفط الخام، ومنشأة واحدة لرسو العوامة للتحميل والتفريغ. تم بناء المحطة للتعامل مع الخام المنتج في الصحراء الغربية لمصر، مما يخلق احتمالات لمزج البراميل الروسية مع البراميل المحلية.

ولم يرد صاحب معبر الحمرا على عدة محاولات للاتصال به عبر الهاتف.

بعد ساعات قليلة من مغادرة الناقلة الأولى - كريستد - الحمرا، وصلت ناقلة أخرى، كريس. تظهر بيانات التتبع أنه كان موجودًا بالفعل في المحطة لعدة أيام، لكنه خرج من المرسى للسماح لـكريستد بالرسو.

تظهر بيانات التتبع عندما غادرت ناقلة كريس ميناء الحمرا أخيرًا في 28 يوليو، كانت خزانات البضائع الخاصة بها ممتلئة تقريبًا. ترسو الآن في ميناء رأس شقير النفطي على ساحل البحر الأحمر في مصر. توفر هذه المحطة أيضًا إمكانيات لمزج الخام الروسي مع البراميل المصرية.

تستخدم روسيا مصر بالفعل كطريق عبور لزيت الوقود. ليس من الواضح ما إذا كان ميناء حمرا تم استخدامه لمرة واحدة أم أنها ستصبح ميناءًا أكثر استخدامًا لتدفقات النفط الروسي.

في السابق، أجرت الناقلات التي تحمل الخام الروسي عمليات نقل البضائع من سفينة إلى سفينة قبالة مدينة سبتة الإسبانية في شمال إفريقيا، ومؤخراً في وسط المحيط الأطلسي. هذا موقع غير معتاد لمثل هذه العملية الصعبة التي يتم تنفيذها عادةً في مواقع محمية بالقرب من الشاطئ.

يبدو أن نقل شحن خام آخر قد حدث في جوهور، بالقرب من سنغافورة، في يونيو. أصبحت المنطقة بالفعل المركز الرئيسي لنقل شحنات إيران إلى الصين.

تأكد من توفر خدمات الشحن والتطبيقات الأخرى..[217]

قائمة الأفراد المعاقبين

يشمل الأفراد الخاضعون للعقوبات موظفين ورجال أعمال بارزين وعاليين في الحكومة المركزية من جميع الأطراف. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، تم أيضًا معاقبة الشركات المقترحة لمشاركتها المحتملة في القضايا المثيرة للجدل.

انظر أيضاً

- مواجهة أعداء أمريكا عبر قانون العقوبات

- العقوبات الدولية أثناء الأزمة الڤنزويلية

- العقوبات الدولية أثناء الفصل العنصري

- قائمة الشركات الخاضعة للعقوبات أثناء الحرب الأوكرانية الروسية

- قانون ماگنيتسكي

- الأزمة المالية الروسية (2014–2016)

الهوامش

- ^ Liubov Nepop, the Head of the Ukrainian Mission to the EU, and Petro Poroshenko, the president of Ukraine

المصادر

- ^ Overland, Indra; Fjaertoft, Daniel (2015). "Financial Sanctions Impact Russian Oil, Equipment Export Ban's Effects Limited". Oil and Gas Journal. 113 (8): 66–72. Archived from the original on 22 February 2018. Retrieved 21 February 2018.

- ^ "Russia’s rouble crisis poses threat to nine countries relying on remittances Archived 9 ديسمبر 2016 at the Wayback Machine ". The Guardian. 18 January 2015.

- ^ أ ب Sharkov, Damien (19 June 2015). "Russian sanctions to 'cost Europe €100bn'". Newsweek.com. Archived from the original on 2 June 2017. Retrieved 1 November 2017.

- ^ Smith, Geoffrey. "Finance Minister: oil slump, sanctions cost Russia $140 billion a year." Archived 19 ديسمبر 2020 at the Wayback Machine 24 November 2014.

- ^ "Владимир Путин: мы сильнее, потому что правы". Archived from the original on 4 October 2020. Retrieved 14 April 2019.

- ^ Pettersen, Trude. "Russia loses $600 billion on sanctions and low oil prices." Archived 11 نوفمبر 2020 at the Wayback Machine The Barents Observer. May 2016.

- ^ "عندما بدا أن نظام العقوبات لا يكلف أي شيء تقريبًا بالنسبة لحجم التجارة في الاتحاد الأوروپي... أجبر روسيا، جنبًا إلى جنب مع المقاومة الأوكرانية، على تغيير نهجها تجاه أوكرانيا ... حتى الآن، comprised of [ك] أثبتت وحدة الاتحاد الأوروپي والتضامن القوي مع أوكرانيا، فضلاً عن المقاومة وتنفيذ الإصلاحات، أنها الطريقة الأكثر فعالية لوقف التقدم العسكري الروسي." – ليوبوڤ نيپوپ، رئيس المبعثة الأوكرانية لدى الاتحاد الأوروپي (source Archived 1 أكتوبر 2015 at the Wayback Machine)

- ^ "... إن العقوبات وبطولة محاربينا هي العناصر الأساسية لردع العدوان الروسي" --الرئيس الأوكراني ڤولوديمير زلنسكي (source Archived 13 يناير 2016 at the Wayback Machine )

- ^ "Obama calls on NATO, EU to boost support for Ukraine". Unian.info. 8 July 2016. Archived from the original on 9 July 2016. Retrieved 8 July 2016.

- ^ "Austrian foreign minister calls for improving relationship with Moscow". Reuters. 19 June 2016. Archived from the original on 17 April 2017. Retrieved 1 July 2017.

- ^ "Sanctions to be lifted from Russia after implementation of Minsk Agreements – Nuland". Interfax-Ukraine. 18 May 2016. Archived from the original on 19 May 2016. Retrieved 8 July 2016.

- ^ "EU Sanctions Map". www.sanctionsmap.eu. Archived from the original on 19 August 2020. Retrieved 2022-02-19.

- ^ "Ukraine-/Russia-related Sanctions". U.S. Department of the Treasury (in الإنجليزية). Archived from the original on 23 February 2022. Retrieved 2022-02-19.

- ^ "Russia: EU renews economic sanctions over the situation in Ukraine for further six months". www.consilium.europa.eu (in الإنجليزية). Archived from the original on 19 February 2022. Retrieved 2022-02-19.

- ^ Melander, Ingrid; Gabriela, Baczynska (24 February 2022). "EU targets Russian economy after 'deluded autocrat' Putin invades Ukraine". Reuters. Archived from the original on 26 February 2022. Retrieved 26 February 2022.

- ^ "China State Banks Restrict Financing for Russian Commodities". Bloomberg News. 25 February 2022. Archived from the original on 25 February 2022. Retrieved 26 February 2022.

- ^ "Western Countries Agree To Add Putin, Lavrov To Sanctions List". 25 February 2022. Archived from the original on 26 February 2022. Retrieved 26 February 2022.

- ^ Holland, Steve; Chalmers, John; Psaledakis, Daphne (26 February 2022). "U.S., allies target 'fortress Russia' with new sanctions, including SWIFT ban". Reuters. Archived from the original on 26 February 2022. Retrieved 26 February 2022.

- ^ Collins, Kaitlan; Mattingly, Phil; Liptak, Kevin; Judd, Donald (26 February 2022). "White House and EU nations announce expulsion of 'selected Russian banks' from SWIFT". CNN. Archived from the original on 26 February 2022. Retrieved 26 February 2022.

- ^ Overland, Indra; Kubayeva, Gulaikhan (1 January 2018). Did China Bankroll Russia's Annexation of Crimea? The Role of Sino-Russian Energy Relations. pp. 95–118. ISBN 9783319697895. Archived from the original on 14 February 2018. Retrieved 26 March 2018.

- ^ "Russia hits West with food import ban in sanctions row". BBC Online. 7 August 2014. Archived from the original on 7 January 2022. Retrieved 27 February 2022.

- ^ Executive Order – Blocking Property of Certain Persons Contributing to the Situation in Ukraine Archived 23 يناير 2017 at the Wayback Machine The White House, 6 March 2014.

- ^ Holland, Steve (6 مارس 2014). "UPDATE 4-Obama warns on Crimea, orders sanctions over Russian moves in Ukraine". Reuters. Archived from the original on 18 يناير 2015. Retrieved 21 يناير 2015.

- ^ أ ب "COUNCIL DECISION 2014/145/CFSP of 17 March 2014 concerning restrictive measures in respect of actions undermining or threatening the territorial integrity, sovereignty and independence of Ukraine" (PDF). Official Journal of the European Union. 17 مارس 2014. Archived from the original on 20 مارس 2014. Retrieved 21 يناير 2015.

- ^ "U.S. and Europe Step Up Sanctions on Russian Officials". New York Times. 17 مارس 2014. Archived from the original on 24 نوفمبر 2014. Retrieved 18 يناير 2015.

- ^ "Sanctions List". Prime Minister of Canada Stephen Harper. 17 March 2014. Archived from the original on 18 January 2015. Retrieved 21 January 2015.

- ^ "EU sanctions against Russia over Ukraine crisis". European External Action Service. Archived from the original on 11 June 2015. Retrieved 1 June 2015.

- ^ Katakey, Rakteem (25 مارس 2014). "Russian Oil Seen Heading East Not West in Crimea Spat". Bloomberg L.P. Archived from the original on 25 مارس 2014. Retrieved 25 مارس 2014.

- ^ "Japan imposes sanctions against Russia over Crimea independence". Fox News. Associated Press. 18 March 2014. Archived from the original on 1 December 2014. Retrieved 21 January 2015.

- ^ "US imposes second wave of sanctions on Russia". jnmjournal.com. 20 March 2014. Archived from the original on 8 November 2014. Retrieved 21 January 2015.

- ^ "Australia imposes sanctions on Russians after annexation of Crimea from Ukraine". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 19 March 2014. Archived from the original on 22 June 2021. Retrieved 21 January 2015.

- ^ Minister for Foreign Affairs (Australia) (21 May 2014). "Further sanctions to support Ukraine". Archived from the original on 27 February 2019. Retrieved 27 January 2015.

- ^ "Declaration by the High Representative on behalf of the European Union on the alignment of certain third countries with the Council Decision 2014/145/CFSPconcerning restrictive measures in respect of actions undermining or threatening the territorial integrity, sovereignty and independence of Ukraine" (PDF). Council of the European Union. 11 أبريل 2014. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 يونيو 2014. Retrieved 23 أغسطس 2014.

- ^ Rettman, Andrew (17 ديسمبر 2014). "Montenegro-EU talks advance in Russia's shadow". EUobserver. Archived from the original on 17 يوليو 2015. Retrieved 1 يونيو 2015.

- ^ "Moldova joined EU sanctions against former Ukrainian officials". Teleradio Moldova. 20 March 2014. Archived from the original on 27 February 2019. Retrieved 27 January 2015.

- ^ Harding, Luke (10 April 2014). "Russia delegation suspended from Council of Europe over Crimea". the Guardian (in الإنجليزية). Archived from the original on 13 December 2018. Retrieved 12 October 2018.

- ^ "U.S. levels new sanctions against Russian officials, companies". Haaretz. 28 April 2014. Archived from the original on 29 August 2014. Retrieved 7 August 2014.

- ^ "EU strengthens sanctions against actions undermining Ukraine's territorial integrity". International Trade Compliance. 28 April 2014. Archived from the original on 4 May 2015. Retrieved 7 August 2014.

- ^ "EU restrictive measures" (PDF). Council of the European Union. 29 أبريل 2014. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 يوليو 2014. Retrieved 23 أغسطس 2014.

- ^ "Third Wave of Sanctions Slams Russian Stocks". The Moscow Times. 17 July 2014. Archived from the original on 18 March 2015. Retrieved 21 January 2015.

- ^ Marchak, Daria (15 July 2014). "EU Readies Russia Sanctions Amid U.S. Pressure on Ukraine". Bloomberg L.P. Archived from the original on 19 October 2017. Retrieved 7 March 2017.

- ^ "EU summit: Leaked draft of new Russia sanctions". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 10 June 2016. Retrieved 28 May 2016.

- ^ "EU Draft Urges Deeper Sanctions Against Russia". International Business Times UK. 16 July 2014. Archived from the original on 9 June 2016. Retrieved 28 May 2016.

- ^ قالب:Cite EU law

- ^ قالب:Cite EU law

- ^ "COUNCIL REGULATION (EU) No 833/2014". Archived from the original on 3 August 2017.

- ^ "Ukraine crisis: U.S., EU, Canada announce new sanctions against Russia". cbc.ca. CBC. Thomson Reuters. 29 July 2014. Archived from the original on 8 July 2021. Retrieved 21 January 2015.

- ^ "Japan Formally OKs Additional Russia Sanctions". ABC News. 5 August 2014. Archived from the original on 6 August 2014.

- ^ Lewis, Rosie (8 August 2014). "Australia 'working towards' tougher sanctions against Russia: Abbott". The Australian. Archived from the original on 5 December 2014. Retrieved 21 January 2015.

- ^ "Prime Minister Tony Abbott arrives in Netherlands, flags tougher sanctions against Russia over MH17". ABC News. 11 August 2014. Archived from the original on 12 November 2020. Retrieved 21 January 2015.

- ^ Mohsin, Saleha (12 August 2014). "Norway 'Ready to Act' as Putin Sanctions Spark Fallout Probe". Bloomberg L.P. Archived from the original on 29 October 2014. Retrieved 21 January 2015.

- ^ Switzerland Expands Sanctions Against Russia Over Ukraine Crisis RFERL: Switzerland Expands Sanctions Against Russia Over Ukraine Crisis

- ^ أ ب "Situation in Ukraine: Federal Council decides on further measures to prevent the circumvention of international sanctions". Bern, Switzerland: news.admin.ch. 27 August 2014. Archived from the original on 8 September 2014.

- ^ RFE/RL (14 August 2014). "Ukraine Passes Law on Russia Sanctions, Gas Pipelines". RadioFreeEurope/RadioLiberty. Archived from the original on 29 October 2014. Retrieved 21 January 2015.

- ^ "Ukraine approves law on sanctions against Russia". Reuters. 14 August 2014. Archived from the original on 29 October 2014. Retrieved 21 January 2015.

- ^ Lamarque, Kevin (11 September 2014). "Obama says U.S. to outline new Russia sanctions on Friday". Reuters. Archived from the original on 11 September 2014. Retrieved 12 September 2014.

- ^ Arshad, Mohammed (12 September 2014). "U.S. steps up sanctions on Russia over Ukraine". Reuters. Archived from the original on 12 September 2014. Retrieved 12 September 2014.

- ^ Takahashi, Maiko (25 September 2014). "U.S. Japan Steps Up Russia Sanctions, Protests Island Visit". Bloomberg News. Archived from the original on 8 January 2015. Retrieved 7 March 2017.

- ^ Biden, Joe (3 أكتوبر 2014). "Remarks by the Vice President at the John F. Kennedy Forum". whitehouse.gov. Archived from the original on 16 فبراير 2017. Retrieved 27 يناير 2015 – via National Archives.

- ^ Croft, Adrian; Emmott, Robin (18 December 2014). "EU bans investment in Crimea, targets oil sector, cruises". Reuters. Archived from the original on 20 December 2014. Retrieved 21 January 2015.

- ^ "US slaps trade ban on Crimea over Russia 'occupation'". Channel NewsAsia. AFP/fl. 20 December 2014. Archived from the original on 20 December 2014. Retrieved 21 January 2015.

- ^ "New EU Sanctions Hit 2 Russian Deputy DMs". Defense News. 16 February 2015. Archived from the original on 19 February 2015. Retrieved 28 May 2016.

- ^ "Expanded Sanctions List". Ottawa, Ontario: pm.gc.ca. 17 February 2015. Archived from the original on 19 February 2015.

- ^ "Ukraine conflict: Russia rebuffs new Canadian sanctions as 'awkward'". CBC News. 18 February 2015. Archived from the original on 6 October 2021. Retrieved 19 February 2015.

- ^ "Expanded Sanctions List". pm.gc.ca. 29 June 2015. Archived from the original on 20 August 2015.

- ^ Berthiaume, Lee (8 July 2015). "Russian sponsor of FIFA world cup sanctioned as tournament ended". Ottawa Citizen. Archived from the original on 8 July 2015. Retrieved 8 July 2015.

- ^ "Президент увів у дію санкції проти Росії: Підписавши указ, Порошенко затвердив рішення РНБО від 2 вересня" [The President imposed sanctions against Russia: By signing the decree, Poroshenko approved the decision of the National Security and Defense Council of September 2]. The Ukrainian Week (Тиждень) (in الأوكرانية). 16 سبتمبر 2015. Archived from the original on 19 أكتوبر 2017. Retrieved 26 يوليو 2017.

- ^ "З'явилися списки фізичних та юридичних осіб РФ, проти яких Україна ввела санкції: Зокрема, у списку фізичних осіб названі 388 прізвищ, у списку юридичних осіб вказані 105 компаній та інших організацій" [Lists of individuals and legal entities of the Russian Federation against which Ukraine has imposed sanctions have appeared: In particular, 388 surnames are listed in the list of individuals, 105 companies and other organizations are listed in the list of legal entities]. The Ukrainian Week (Тиждень) (in الأوكرانية). 16 سبتمبر 2015. Archived from the original on 26 يونيو 2016. Retrieved 26 يوليو 2017.

- ^ "Додаток 1 до рішення Ради національної безпеки і оборони України від 2 вересня 2015 року: спеціальних економічних та інших обмежувальних заходів (санкцій)" [Appendix 1 to decision for the sake of national security and defense of Ukraine from 2 September 2015: Special economic and other restrictive measures (Sanctions)] (PDF). Presidential decree (in الأوكرانية). 2 سبتمبر 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 أغسطس 2017. Retrieved 26 يوليو 2017.

- ^ "Додаток 2 до рішення Ради національної безпеки і оборони України від 2 вересня 2015 року: спеціальних економічних та інших обмежувальних заходів (санкцій)" [Annex 2 to decision for the sake of national security and defense of Ukraine from 2 September 2015: Special economic and other restrictive measures (Sanctions)] (PDF). Presidential decree (in الأوكرانية). 2 سبتمبر 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 يوليو 2017. Retrieved 26 يوليو 2017.

- ^ "Russia-Ukraine crisis: South Korea to support sanctions on Russia". Wap.business-standard.com. Archived from the original on 24 February 2022. Retrieved 2022-02-25.

- ^ "Taiwan says it will join 'democratic countries' to sanction Russia". Financial Post. 25 February 2022.

- ^ "Singapore to impose banking, trade restrictions on Russia". Nikkei Asia. 28 February 2022. Archived from the original on 28 February 2022. Retrieved 28 February 2022.

- ^ Bhavan Jaipragas (28 February 2022). "Singapore to slap unilateral sanctions on Russia in 'almost unprecedented' move". South China Morning Post (in الإنجليزية). Archived from the original on 28 February 2022. Retrieved 28 February 2022.

- ^ "EU sanctions add to Putin's Crimea headache". EUobserver.com. EUobserver. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 28 March 2015.

- ^ "Special Economic Measures (Ukraine) Regulations". Canadian Justice Laws Website. 17 March 2014. Archived from the original on 2 July 2021. Retrieved 30 March 2015.

- ^ "Australia and sanctions – Consolidated List – Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade". Dfat.gov.au. 25 March 2015. Archived from the original on 29 February 2020. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- ^ "Declaration by the High Representative on behalf of the European Union on the alignment of certain third countries with the Council Decision 2014/145/CFSPconcerning restrictive measures in respect of actions undermining or threatening the territorial integrity, sovereignty and independence of Ukraine" (PDF). European Union. 11 April 2014. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- ^ أ ب "Treasury Targets Sanctions Evasion Scheme Facilitating Jet Fuel Shipments to Russian Military Forces in Syria". Archived from the original on 15 November 2021. Retrieved 26 September 2019.

- ^ Sytas, Andrius (12 April 2016). "Lithuania blacklists 46 for their role in Savchenko trial". Reuters. Archived from the original on 19 October 2017. Retrieved 1 July 2017.

- ^ "European Union countries agree on a new package of sanctions against Russia over the war in Ukraine" (June 21, 2023). AP. Accessed 25 June 2023.

- ^ Freifeld, Karen (2024-03-29). "US takes another step to stem the flow of technology to Russia for weapons". Reuters (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2024-03-31.

- ^ "EU adopts 11th sanctions package against Russia" dentons.com. Accessed 25 July 2023.

- ^ "International - Russia". U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA). Archived from the original on 17 February 2021. Retrieved 2022-03-24.

- ^ McFall, Caitlin (1 March 2022). "Sen. Marshall introduces bill banning US imports of Russian oil". Archived from the original on 8 March 2022. Retrieved 8 March 2022.

- ^ Aitken, Peter (4 March 2022). "Blinken says 'no strategic interest' in Russia energy sanctions, resists calls for oil import ban". Archived from the original on 8 March 2022. Retrieved 8 March 2022.

- ^ Miller, Zeke; Balsamo, Mike; Boak, Josh (9 March 2022). "US strikes harder at Putin, banning all Russian oil imports". Associated Press. Archived from the original on 10 March 2022. Retrieved 11 March 2022.

- ^ "G7 countries agree to cap the price of Russian oil". 2 September 2022.

- ^ "OFAC Guidance on Implementation of the Price Cap Policy for Crude Oil of Russian Federation Origin" (PDF). Retrieved 25 November 2022.

- ^ "What are the sanctions on Russia and are they hurting its economy?". BBC News. 27 January 2022. Retrieved 25 November 2022.

- ^ "Russia Loses 90% of Its Key European Oil Market Before Sanctions". Bloomberg News. 21 November 2022. Retrieved 25 November 2022.

- ^ "Oil and gas budget revenues reach $19.61 bln in Q1 2023 — Finance Ministry". 7 April 2023.

- ^ "Insight: Weighed down oil prices support lowering the price cap on Russian oil". 7 March 2023.

- ^ Psaledakis, Daphne; Sanicola, Laura (2023-11-16). "US sanctions maritime companies, vessels for shipping oil above Russian price cap". Reuters (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2023-11-19.

- ^ "ناقلات النفط الروسي داخل قفص العقوبات.. "سوفكومفلوت" آخر الضحايا". الطاقة.

- ^ "Remarks by President Biden Announcing Response to Russian Actions in Ukraine". The White House. 22 February 2022. Archived from the original on 23 February 2022. Retrieved 24 February 2022.

- ^ Holland, Steve; Mason, Jeff; Psaledakis, Daphne; Alper, Alexandra (23 February 2022). "Biden puts sanctions on Russian banks and elites as he says Ukraine invasion has begun". Reuters. Archived from the original on 24 February 2022. Retrieved 2 March 2022.

- ^ "Biden unveils new Russia sanctions over Ukraine invasion". Al Jazeera. Archived from the original on 2 March 2022. Retrieved 2 March 2022.

- ^ "Ukraine-Russia invasion: Russia launches attack on Ukraine from several fronts". BBC News. Archived from the original on 21 February 2022. Retrieved 24 February 2022.

- ^ "Ukraine conflict: UK sanctions target Russia banks and oligarchs". BBC News. 24 February 2022. Archived from the original on 26 February 2022. Retrieved 24 February 2022.

- ^ "The hidden costs of cutting Russia off from SWIFT". The Economist. Archived from the original on 24 February 2022. Retrieved 24 February 2022.

- ^ "EU unlikely to cut Russia off SWIFT for now, sources say". Reuters. 24 February 2022. Archived from the original on 24 February 2022. Retrieved 24 February 2022.

- ^ "Czech president: Russia should be cut off from SWIFT". Reuters. 24 February 2022. Archived from the original on 24 February 2022. Retrieved 24 February 2022.

- ^ "UK politics live: Boris Johnson making statement on sanctions; PM 'trying to persuade G7 to remove Russia from Swift payments system'". The Guardian. 24 February 2022. Archived from the original on 24 February 2022. Retrieved 24 February 2022.

- ^ Pop, Valentina (25 February 2022). "EU leaders agree more Russia sanctions, but save some for later". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 25 February 2022. Retrieved 25 February 2022.

- ^ "Germany Backs 'Targeted' Russian SWIFT Removal: Ukraine Update". Yahoo. Yahoo News. Archived from the original on 26 February 2022. Retrieved 26 February 2022.

- ^ "Western allies will remove Russian banks from Swift". BBC News. Archived from the original on 25 February 2022. Retrieved 26 February 2022.

- ^ أ ب Golubkova, Katya; Baczynska, Gabriela (10 ديسمبر 2014). "Rouble fall, sanctions hurt Russia's economy: Medvedev". Reuters. Archived from the original on 29 يونيو 2015. Retrieved 1 يونيو 2015. خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صالح؛ الاسم "reutersinterviewmedvedev" معرف أكثر من مرة بمحتويات مختلفة. - ^ Fleming, Sam; Solomon, Erika; Borrelli, Silvia Sciorilli (26 February 2022). "Italy move adds to EU momentum for cutting Russian banks from Swift". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 3 March 2022. Retrieved 5 March 2022.

- ^ "Chinese banks limit financing for Russian purchases: Bloomberg". Agence France-Presse. 26 February 2022. Archived from the original on 28 February 2022. Retrieved 28 February 2022.

- ^ Cumming-Bruce, Nick (28 February 2022). "Switzerland says it will freeze Russian assets, setting aside a tradition of neutrality". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 1 March 2022. Retrieved 1 March 2022.

- ^ "Monaco clamps down on Russian assets after Ukraine invasion". Reuters. 28 February 2022. Archived from the original on 5 March 2022. Retrieved 1 March 2022.

- ^ "French finance minister: We will bring about collapse of the Russian economy". The Local France. 1 March 2022. Archived from the original on 1 March 2022. Retrieved 3 March 2022.

- ^ "Singapore to impose banking, trade restrictions on Russia". Nikkei Asia. 28 February 2022. Archived from the original on 28 February 2022. Retrieved 28 February 2022.

- ^ Jaipragas, Bhavan (28 February 2022). "Singapore to slap unilateral sanctions on Russia in 'almost unprecedented' move". South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on 28 February 2022. Retrieved 28 February 2022.

- ^ Kajimoto, Tetsushi; Komiya, Kantaro (28 February 2022). "Japan joins sanctions on Russian central bank, says 'Japan is with Ukraine'". Reuters. Archived from the original on 1 March 2022. Retrieved 1 March 2022.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماة:1 - ^ "The West's Plan to Isolate Putin: Undermine the Ruble". The New York Times. 28 February 2022. Archived from the original on 2 March 2022. Retrieved 2 March 2022.

- ^ "The West declares economic war on Russia". Politico. 28 February 2022. Archived from the original on 2 March 2022. Retrieved 2 March 2022.

- ^ "Sanctions on Russia Puts Focus on China's Central Bank". Bloomberg. 28 February 2022. Archived from the original on 1 March 2022. Retrieved 5 March 2022.

- ^ "The West's $1 trillion bid to collapse Russia's economy". CNN. 1 March 2022. Archived from the original on 1 March 2022. Retrieved 2 March 2022.

- ^ Kim, Hyun-cheol (1 March 2022). "정부, 러시아 주요 7개 은행 거래 중지...국고채 거래도 중단" [Government suspends trading with 7 major Russian banks... also suspends KTB trading]. fnnews.com (in الكورية). Archived from the original on 2 March 2022. Retrieved 7 March 2022.

- ^ "한·미 재무 당국, '우크라 침공' 대러 제재 협의…美 "韓정부 발표 환영"" [South Korea and US financial authorities discuss sanctions against Russia for 'invasion of Ukraine'... US "welcomes South Korean government announcement"]. newsis.com (in الكورية). 2 March 2022. Archived from the original on 7 March 2022.

- ^ "Sanctions on Russia: asset managers are making a disorderly retreat". Financial Times. 1 March 2022. Archived from the original on 3 March 2022. Retrieved 2 March 2022.

- ^ "Visa, Mastercard, Amex block Russian banks after sanctions". France 24. 2 March 2022. Archived from the original on 2 March 2022. Retrieved 2 March 2022.

- ^ Smith, Robert (2 March 2022). "Credit Suisse asks investors to destroy oligarch loans documents". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 2 March 2022. Retrieved 2 March 2022.

- ^ "EU weighs concession to Russian bank over Black Sea grain deal". Alarabiya (in الإنجليزية). 2023-07-03. Retrieved 2023-07-04.

- ^ "How the collapse of the ruble could impact the war in Ukraine". The Week. 16 August 2023.

- ^ "Executive Order 14065 of February 21, 2022 — Blocking Property of Certain Persons and Prohibiting Certain Transactions With Respect to Continued Russian Efforts To Undermine the Sovereignty and Territorial Integrity of Ukraine". Archived from the original on 9 March 2022. Retrieved 6 March 2022.

- ^ "America has targeted Russia's technological fabric". The Economist. 25 February 2022. Archived from the original on 25 February 2022. Retrieved 25 February 2022.

- ^ "Italy, Hungary say no automatic renewal of Russia sanctions". Reuters. 14 March 2016. Archived from the original on 2 June 2016. Retrieved 1 June 2016.

- ^ Gergely Szakacs (15 August 2014). "Europe 'shot itself in foot' with Russia sanctions: Hungary PM". Reuters. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 28 May 2016.

- ^ "Bulgaria says it is suffering from EU sanctions on Russia". Voice of America. 4 December 2014. Archived from the original on 20 April 2021. Retrieved 12 November 2019.

- ^ "Zeman appears on Russian TV to blast sanctions". praguepost.com. 17 November 2014. Archived from the original on 11 April 2017. Retrieved 12 April 2017.

- ^ "Slovak PM slams sanctions on Russia, threatens to veto new ones Archived 23 يوليو 2015 at the Wayback Machine ". Reuters. 31 August 2014.

- ^ David Reid, Geoff Cutmore (4 October 2017). "Sanctions on Russia don't work, says Hungary's foreign minister". CNBC. Archived from the original on 5 October 2017. Retrieved 10 December 2017.

- ^ "Greece's Tsipras meets Putin in Moscow – as it happened". The Guardian. 8 April 2015. Archived from the original on 17 August 2015. Retrieved 15 August 2015.

- ^ Pancevski, Bojan (9 November 2014). "Industry urges Merkel to back down on Moscow sanctions – The Sunday Times". The Sunday Times. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 28 May 2016.

- ^ WSJ Staff (21 October 2014). "Total CEO Christophe de Margerie's Speech About Russian Sanctions". WSJ. Archived from the original on 6 September 2015. Retrieved 28 May 2016.

- ^

Reuters Editorial (26 September 2014). "UniCredit says sanctions hurting Europe more than Russia: Czech media". Reuters. Archived from the original on 10 October 2015. Retrieved 28 May 2016.

{{cite web}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ Kirschbaum, Erik (16 November 2016). "German economy minister rejects tougher sanctions on Russia". Reuters. Archived from the original on 12 April 2017. Retrieved 12 April 2017.

- ^ Tanquintic-Misa, Esther (5 January 2015). "More Anti-Russian Sanctions Will Ultimately Cripple Europe – German Vice-Chancellor". ibtimes.com.au. Archived from the original on 20 February 2015. Retrieved 12 April 2017.