فيليكي نوفغورود

{{ safesubst:#invoke:Unsubst||date=__DATE__|$B=

ڤليكي نوڤگورود

Великий Новгород | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

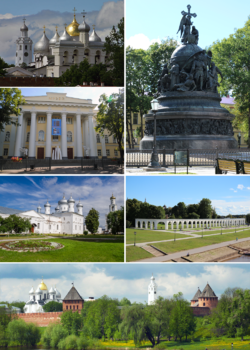

Counter-Clockwise: the Millennium of Russia, cathedral of St. Sophia, the fine arts museum, St. George's Monastery, the Kremlin, Yaroslav's Court | |||||||||||||||

| النشيد: لا يوجد[1] | |||||||||||||||

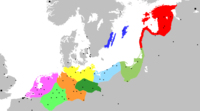

Location of ڤليكي نوڤگورود خطأ: الوظيفة "main" غير موجودة. | |||||||||||||||

| الإحداثيات: 58°33′N 31°16′E / 58.550°N 31.267°E | |||||||||||||||

| البلد | روسيا | ||||||||||||||

| الكيان الاتحادي | Novgorod Oblast[2] | ||||||||||||||

| First mentioned | 859[3] or 862[4] | ||||||||||||||

| الحكومة | |||||||||||||||

| • الكيان | دوما مدينة نوڤگورود | ||||||||||||||

| • Mayor | Yuri Bobryshev | ||||||||||||||

| المساحة | |||||||||||||||

| • الإجمالي | 90 كم² (30 ميل²) | ||||||||||||||

| المنسوب | 25 m (82 ft) | ||||||||||||||

| التعداد | |||||||||||||||

| • الإجمالي | 218٬717 | ||||||||||||||

| • Estimate (2018) | 222٬868 (+1٫9%) | ||||||||||||||

| • الترتيب | 85th in 2010 | ||||||||||||||

| • الكثافة | 2٬400/km2 (6٬300/sq mi) | ||||||||||||||

| • Subordinated to | city of oblast significance of Veliky Novgorod[2] | ||||||||||||||

| • Capital of | اوبلاست نوڤگورود[2], city of oblast significance of Veliky Novgorod[2] | ||||||||||||||

| منطقة التوقيت | UTC+ ([7]) | ||||||||||||||

| Postal code(s)[8] | 173000–173005, 173007–173009, 173011–173016, 173018, 173020–173025, 173700, 173899, 173920, 173955, 173990, 173999 | ||||||||||||||

| Dialing code(s) | +7 8162 | ||||||||||||||

| OKTMO ID | 49701000001 | ||||||||||||||

| الموقع الإلكتروني | www | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| Historic Monuments of Novgorod and Surroundings | |

|---|---|

| |

| أسس الاختيار | Cultural: ii, iv, vi |

| المراجع | 604 |

| Inscription | 1992 (16th Session) |

ڤيليكي نوڤگورود (روسية: Великий Новгород; النطق الروسي: [vʲɪˈlʲikʲɪj ˈnovɡərət]؛ وتعني حرفياً نوڤگورود الكبرى) هي إحدى مدن روسيا في الكيان الفدرالي الروسي اوبلاست نوفگورود. يبلغ عدد سكانها حوالي 215625 نسمة.

في العصور الوسطى أطلق عليها تسمية " السيد نوڤگورود الكبير " ويبدأ التاريخ السياسي بتحديد دور ومهام الأمير منذ عام 1136. وحتى انتصار إيڤان الثالث، أمير موسكو على أهالي نوڤگورود عام 1478 كانت تسمى " جمهورية نوڤگورود".

وتقع المدينة على نهر ڤولخوڤ، وعلى مقربة من بحيرة إيلمن الجميلة على بعد 500 كم إلى الشمال الغربي من موسكو.

التاريخ

التطورات المبكرة

وفي الفترة من القرن 9 إلى القرن 12 كانت نوڤگورود عاصمة، بعدها أصبحت بالمرتبة الثانية، حسب الاهمية بعد كييف مركز دولة روس القديمة. حتى نهاية القرن 15 بقيت عاصمة لمنطقة نوڤگورود (امارة روسية مستقلة). ليس هناك تاريخ رسمي موثق لتاسيس المدينة، لذلك اعتبر أول ذكر للمدينة في السجلات التاريخية سنة 859 هو تاريخ تأسيسها.

The Sofia First Chronicle makes initial mention of it in 859, while the Novgorod First Chronicle first mentions it in 862, when it was purportedly already a major Baltic-to-Byzantium station on the trade route from the Varangians to the Greeks.[4] The Charter of Veliky Novgorod recognizes 859 as the year when the city was first mentioned.[3] Novgorod is traditionally considered to be a cradle of Russian statehood.[9]

The oldest archaeological excavations in the middle to late 20th century, however, have found cultural layers dating back to the late 10th century, the time of the Christianization of Rus' and a century after it was allegedly founded.[10] Archaeological dating is fairly easy and accurate to within 15–25 years, as the streets were paved with wood, and most of the houses made of wood, allowing tree ring dating.[citation needed]

The Varangian name of the city Holmgård or Holmgard (Holmgarðr or Holmgarðir) is mentioned in Norse Sagas as existing at a yet earlier stage, but the correlation of this reference with the actual city is uncertain.[11] Originally, Holmgård referred to the stronghold, now only 2 km (1.2 ميل) to the south of the center of the present-day city, Rurikovo Gorodische (named in comparatively modern times after the Varangian chieftain Rurik, who supposedly made it his "capital" around 860). Archaeological data suggests that the Gorodishche, the residence of the Knyaz (prince), dates from the mid-9th century,[12] whereas the town itself dates only from the end of the 10th century; hence the name Novgorod, "new city", from Old East Slavic Новъ and Городъ (Nov and Gorod); the Old Norse term Nýgarðr is a calque of an Old Russian word. First mention of this Norse etymology to the name of the city of Novgorod (and that of other cities within the territory of the then Kievan Rus') occurs in the 10th-century policy manual De Administrando Imperio by Byzantine emperor Constantine VII.[citation needed]

Princely state within Kievan Rus'

In 882, Rurik's successor, Oleg of Novgorod, conquered Kiev and founded the state of Kievan Rus'. Novgorod's size as well as its political, economic, and cultural influence made it the second most important city in Kievan Rus'. According to a custom, the elder son and heir of the ruling Kievan monarch was sent to rule Novgorod even as a minor. When the ruling monarch had no such son, Novgorod was governed by posadniks, such as the legendary Gostomysl, Dobrynya, Konstantin, and Ostromir.[citation needed]

Yaroslav the Wise was Prince of Novgorod from 1010 to 1019, while his father, Vladimir the Great, was a prince in Kiev. Yaroslav promulgated the first written code of laws (later incorporated into Russkaya Pravda) among the Eastern Slavs and is said to have granted the city a number of freedoms or privileges, which they often referred to in later centuries as precedents in their relations with other princes. His son, Vladimir of Novgorod, sponsored construction of the great St. Sophia Cathedral, more accurately translated as the Cathedral of Holy Wisdom, which stands to this day.[citation needed]

Early foreign ties

In Norse sagas the city is mentioned as the capital of Gardariki.[13][14][15] Many Viking kings and yarls came to Novgorod seeking refuge or employment, including Olaf I of Norway, Olaf II of Norway, Magnus I of Norway, and Harald Hardrada.[16] No more than a few decades after the 1030 death and subsequent canonization of Olaf II of Norway, the city's community had erected in his memory Saint Olaf's Church in Novgorod.[17]

The Gotland town of Visby functioned as the leading trading center in the Baltic before the Hansa League. At Novgorod in 1080, Visby merchants established a trading post which they named Gutagard (also known as Gotenhof).[18] Later, in the first half of the 13th century, merchants from northern Germany also established their own trading station in Novgorod, known as the Peterhof.[19] At about the same time, in 1229, German merchants at Novgorod were granted certain privileges, which made their position more secure.[20]

Novgorod Republic

In 1136, the Novgorodians dismissed their prince Vsevolod Mstislavich. The year is seen as the traditional beginning of the Novgorod Republic. The city was able to invite and dismiss a number of princes over the next two centuries, but the princely office was never abolished and powerful princes, such as Alexander Nevsky, could assert their will in the city regardless of what Novgorodians said.[21] The city state controlled most of Europe's northeast, from lands east of today's Estonia to the Ural Mountains, making it one of the largest states in medieval Europe, although much of the territory north and east of Lakes Ladoga and Onega was sparsely populated and never organized politically.[citation needed]

One of the most important local figures in Novgorod was the posadnik, or mayor, an official elected by the public assembly (called the Veche) from among the city's boyars, or aristocracy. The tysyatsky, or "thousandman", originally the head of the town militia but later a commercial and judicial official, was also elected by the Veche. Another important local official was the Archbishop of Novgorod who shared power with the boyars.[22] Archbishops were elected by the Veche or by the drawing of lots, and after their election, were sent to the metropolitan for consecration.[23]

While a basic outline of the various officials and the Veche can be drawn up, the city-state's exact political constitution remains unknown. The boyars and the archbishop ruled the city together, although where one official's power ended and another's began is uncertain. The prince, although his power was reduced from around the middle of the 12th century, was represented by his namestnik, or lieutenant, and still played important roles as a military commander, legislator and jurist. The exact composition of the Veche, too, is uncertain, with some historians, such as Vasily Klyuchevsky, claiming it was democratic in nature, while later scholars, such as Marxists Valentin Ianin and Aleksandr Khoroshev, see it as a "sham democracy" controlled by the ruling elite.[citation needed]

In the 13th century, Novgorod, while not a member of the Hanseatic League, was the easternmost kontor, or entrepôt, of the league, being the source of enormous quantities of luxury (sable, ermine, fox, marmot) and non-luxury furs (squirrel pelts).[24]

Throughout the Middle Ages, the city thrived culturally. A large number of birch bark letters have been unearthed in excavations, perhaps suggesting widespread literacy. It was in Novgorod that the Novgorod Codex, the oldest Slavic book written north of Bulgaria, and the oldest inscription in a Finnic language (Birch bark letter no. 292) were unearthed. Some of the most ancient Russian chronicles (Novgorod First Chronicle) were written in the scriptorium of the archbishops who also promoted iconography and patronized church construction. The Novgorod merchant Sadko became a popular hero of Russian folklore.[citation needed]

Novgorod was never conquered by the Mongols during the Mongol invasion of Rus. The Mongol army turned back about 200 كيلومتر (120 mi) from the city, not because of the city's strength, but probably because the Mongol commanders did not want to get bogged down in the marshlands surrounding the city. However, the grand princes of Moscow, who acted as tax collectors for the khans of the Golden Horde, did collect tribute in Novgorod, most notably Yury Danilovich and his brother, Ivan Kalita.[citation needed]

In 1259, Mongol tax-collectors and census-takers arrived in the city, leading to political disturbances and forcing Alexander Nevsky to punish a number of town officials (he cut off their noses) for defying him as Grand Prince of Vladimir (soon to be the khan's tax-collector in Russia) and his Mongol overlords. In the 14th century, raids by Novgorod pirates, or ushkuiniki,[25] sowed fear as far as Kazan and Astrakhan, assisting Novgorod in wars with the Grand Duchy of Moscow.[citation needed]

During the era of Old Rus' State, Novgorod was a major trade hub at the northern end of both the Volga trade route and the "route from the Varangians to the Greeks" along the Dnieper river system. A vast array of goods were transported along these routes and exchanged with local Novgorod merchants and other traders. The farmers of Gotland retained the Saint Olof trading house well into the 12th century. Later German merchantmen also established tradinghouses in Novgorod. Scandinavian royalty would intermarry with Russian princes and princesses.[citation needed]

After the great schism, Novgorod struggled from the beginning of the 13th century against Swedish, Danish, and German crusaders. During the Swedish-Novgorodian Wars, the Swedes invaded lands where some of the population had earlier paid tribute to Novgorod. The Germans had been trying to conquer the Baltic region since the late 12th century. Novgorod went to war 26 times with Sweden and 11 times with the Livonian Brothers of the Sword. The German knights, along with Danish and Swedish feudal lords, launched a series of uncoordinated attacks in 1240–1242. Novgorodian sources mention that a Swedish army was defeated in the Battle of the Neva in 1240. The Baltic German campaigns ended in failure after the Battle on the Ice in 1242. After the foundation of the castle of Viborg in 1293 the Swedes gained a foothold in Karelia. On August 12, 1323, Sweden and Novgorod signed the Treaty of Nöteborg, regulating their border for the first time.[citation needed]

The city's downfall occurred partially as a result of its inability to feed its large population,[citation needed] making it dependent on the Vladimir-Suzdal region for grain. The main cities in the area, Moscow and Tver, used this dependence to gain control over Novgorod. Eventually Ivan III forcibly annexed the city to the Grand Duchy of Moscow in 1478. The Veche was dissolved and a significant part of Novgorod's aristocracy, merchants and smaller landholding families was deported to central Russia. The Hanseatic League kontor was closed in 1494 and the goods stored there were seized by Muscovite forces.[26][27]

معركة البحيرة المتجمدة

وتدل الصفحات التاريخية على عظمتها وفواجعها، ففي عام 1240 تمكن اهالي المدينة بقيادة الامير الكسندر الذي لقب فيما بعد بـ"نيڤسكي" بدحر الصليبيين السويديين في معركة نهر نيڤا، وفي عام 1242 انتصروا على فرسان الصليبيين من أخوية ليفون في معركة بحيرة پيپوس المتجمدة وأجبر هذا لانتصارالرائع الصليبيين إلى عقد اتفاقية صلح (أريخوفي مير) مع الروس وهو أول اتفاق للسلام بين امارة روسية مع دولة مجاورة، كما ان هذا الانتصار ساعد على حماية روس القديمة الضعيفة نتيجة الغزو التتاري المغولي، من الغزو الكاثوليكي. ومنذ عام 1478 الحقت نوڤگورود وضواحيها بإمارة موسكو. وفي الفترة من 1569 – 1570 ظن إيڤان الرهيب أن أهالي نوڤگورود خونة، لذلك نهبت المدينة وقتل الآلاف من أهلها.

موطن نظام الدولة الروسية

يمر بجانب بحيرة ايلمن منذ امد بعيد طريق التجارة الدولي بالطيا – فولجسكي الذي ساعد عند منابع نهر فولخوف في تكوين مركز التبادل السياسي بين قبائل فينـّو-اوگورسك المحلية والقبائل السلافينية الاتية في الفترة بين القرنين 6 و8.

روريك: نصب الذكرى الالفية لروسياوفي عام 862 استدعى زعماء القبائل في نوڤگورود الامير الاسكندينافي روريك مع مقاتلين للقيام بتنفيذ مهام المحاكم والامن، وكانت هذه بداية للسلالة التي حكمت جميع الاراضي الروسية لمدة تزيد على 7.5 قرن).

في بداية القرن 10 سمحت حملات الامير ايغور وقائد جيشه اوليگ من نوڤگورود الجنوبية بفتح طريق تجاري من " ڤارياگ إلى الاغريق " مما أسرع بتوحيد السلاڤ الشرقيين في دولة موحدة، عرفت روسء الكييڤية.

ولعبت نوڤگورود دورا كبيرا في نشر المسيحية في المنطقة الشمالية – الغربية والشمالية. ونظرا للدور الكبير الذي لعبه كهنة نوڤگورود في الدفاع عن المذهب الأرثوذكسي وتطويره، تمت ترقيتهم إلى مرتبة رؤساء اساقفة.

في القرن 15 حصلت سلطة اساقفة نوڤگورود على مسحة جديدة، حيث أصبحت تشمل كل جوانب الحياة وتترأس فعليا جمهورية النبلاء الصغيرة. ويذكر نوڤگورود خلال هذه الفترة الفاتيكان، حيث السلطة العلمانية تتبع بالكامل السلطة الروحية، الا انها تمتاز عن الفاتيكان كونها تحكم مساحة واسعة تعادل مجموع مساحة فرنسا الحالية وبلجيكا وهولندا، أو مساحة ولاية تكساس الأمريكية.

وسبب انتصار موسكو وانضمام نوڤگورود إلى الدولة المركزية نهاية هذه الجمهورية الذاتية (الأصيلة).

نوڤگورود – موطن الديمقراطية الروسية

في عهد يارسلاف الحكيم منح زعماء القبائل القاطنة نوڤگورود حقوق خاصة وتسهيلات ضرائبية. وفي نهاية القرن 11 انبعثت الإدارة الذاتية ومجلس الشعب، وانتخاب رئيس من نبلاء المدينة شكلت بداية للتقاليد الجمهورية.

Tsardom of Russia

At the time of annexation, Novgorod became the third largest city under Muscovy and then the Tsardom of Russia (with 5,300 homesteads and 25–30 thousand inhabitants in the 1550s[28]) and remained so until the famine of the 1560s and the Massacre of Novgorod in 1570. In the Massacre, Ivan the Terrible sacked the city, slaughtered thousands of its inhabitants, and deported the city's merchant elite and nobility to Moscow, Yaroslavl and elsewhere. The last decade of the 16th century was a comparatively favourable period for the city as Boris Godunov restored trade privileges and raised the status of Novgorod bishop. The German trading post was reestablished in 1603.[29] Even after the incorporation into the Russian state Novgorod land retained its distinct identity and institutions, including the customs policy and administrative division. Certain elective offices were quickly restored after having been abolished by Ivan III.[30]

During the Time of Troubles, Novgorodians submitted to Swedish troops led by Jacob De la Gardie in the summer of 1611. The city was restituted to Muscovy six years later by the Treaty of Stolbovo. The conflict led to further depopulation: the number of homesteads in the city decreased from 1158 in 1607 to only 493 in 1617, with the Sofia side described as 'deserted'.[31][32] Novgorod only regained a measure of its former prosperity towards the end of the century, when such ambitious buildings as the Cathedral of the Sign and the Vyazhischi Monastery were constructed. The most famous of Muscovite patriarchs, Nikon, was active in Novgorod between 1648 and 1652. The Novgorod Land became one of the Old Believers' strongholds after the Schism.[29] The city remained an important trade centre even though it was now eclipsed by Archangelsk, Novgorodian merchants were trading in the Baltic cities and Stockholm while Swedish merchants came to Novgorod where they had their own trading post since 1627.[33] Novgorod continued to be a major centre of crafts which employed the majority of its population. There were more than 200 distinct professions in 16th century. Bells, cannons and other arms were produced in Novgorod; its silversmiths were famous for the skan' technique used for religious items and jewellery. Novgorod chests were in widespread use all across Russia, including the Tsar's household and the northern monasteries.[34]

Russian Empire

In 1727, Novgorod was made the administrative center of Novgorod Governorate of the Russian Empire, which was detached from Saint Petersburg Governorate (see Administrative divisions of Russia in 1727–1728). This administrative division existed until 1927. Between 1927 and 1944, the city was a part of Leningrad Oblast, and then became the administrative center of the newly formed Novgorod Oblast.[citation needed]

Modern era

On August 15, 1941, during World War II, the city was occupied by the German Army. Its historic monuments were systematically obliterated. The Red Army liberated the city on January 19, 1944. Out of 2,536 stone buildings, fewer than forty remained standing. After the war, thanks to plans laid down by Alexey Shchusev, the central part was gradually restored. In 1992, the chief monuments of the city and the surrounding area were inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage Site list as the Historic Monuments of Novgorod and Surroundings. As of 2020, regular archeological rescue work continues across the site.[35] In 1999, the city was officially renamed Veliky Novgorod (literally, Great Novgorod),[36] thus partly reverting to its medieval title "Lord Novgorod the Great". This reduced the temptation to confuse Veliky Novgorod with Nizhny Novgorod, a larger city the other side of Moscow which, between 1932 and 1990, had been renamed Gorky, in honour of Maxim Gorky.[citation needed]

مركز للتجارة الدولية في العصور الوسطى

ساعد تثبيت الطريق التجارية " من فارياغ إلى الاغريق " على تطور مدينة نوڤگورود، كنقطة ترانزيت تجارية. وتشهد على ذلك النقود المعدنية لدول أوروبا الغربية ودول شرقية التي عثر عليها، وكذلك المعادن الملونة (غير الحديدية) واقمشة ثمينة واواني للخمور وزيت الزيتون من أوروبا الغربية والبيزنطية. وكانت أوروبا ومن ضمنها إنجلترا تعرف الفراء والعسل والشمع والكتان المنتجة في نوڤگورود.

نوڤگورود – مركز للمعارف

إن أساس المعارف هو الكتابة. اكتشفت عام 1951 في احدى طبقات الحفريات التي اجريت في المدينة أول 10 وثائق مكتوبة على لحاء شجرة البتولا، ويبلغ عددها اليوم حوالي 1000 وثيقة. وهذه القطع من القشرة تشهد على كون الاهالي يعرفون القراءة والكتابة.

واول من بدأ بنشر القراءة والكتابة في نوڤگورود كان الامير يارسلاف الحكيم، الذي انشأ مدرسة في مقر الاسقفية. وكانت كاتدرائية القديسة صوفيا والاديرة الكبيرة يوريف وانتونيف وخوتينسكي مركزا لتسجيل الاحداث والمكتبات.

وكانت احدى أكبر المكتبات في القرون الوسطى بروسيا تحتوي على أكثر من 1500 كتاب مستنسخ يدويا. وكانت المكتبة في كاتدرائية صوفيا. وفي عهد القيصر بطرس الأول حيث بدأت بالانتشار التعاليم العلمانية، بقيت نوڤگورود تنظر إلى المعارف من خلال موشور الأرثوذكسية. في عام 1706 اسس الاخوان اليونانيان المشهوران ليهود (ليخود) في مقر الاسقفية أول مدرسة دائمة، وفي عام 1740 تحولت إلى مدرسة لاهوتية وأصبح مقرها في دير انتونيف.

مركز ثقافي بارز في القرون الوسطى

تعتبر المدينة واحدة من المدن التي يمكن فيها مشاهدة اعمال فترة بيزنطينة وكييف: كاتدرائيات صوفيا ونيقولا – دفورشينسكي وگيورگڤسكي ونقوش فيوفان غريك، إلى جانب اثار الطراز الرومانسي والغوطي : بوابة ماغديبورغ الرائعة (القرن 12) ومنذ القرن 15 زينت المدخل الجنوبي لمعبد المدينة الرئيسي، اما مقر الاسقف فله قاعة استقبال ذات اقواس مضلعة صممها معماريون المان.

ونظرا لعدم تعرض المدينة للنهب خلال الاجتياح المغولي- التتري فأنه حافظ على القيم الروحية والفنية العالية التي افادت الثقافة الروسية في فترة نهوضها في القرنين 14 و 15. وهنا في نوڤگورود كانت بداية فن الايقونات – ايقونات الرسل بطرس وبولس (القرن 11) و" المخلص متربع على العرش " (القرن 11) و" القديس جيورجي – المحارب " (القرن 11) والكؤوس الفضية المستخدمة في الطقوس الدينية من كاتدرائية صوفيا ونماذج من النقوش الذهبية.

وازدهرت الثقافة في مدينة نوڤگورود التي تشكلت فيها جمعيات للبناء ورسم الايقونات والتطريز بالذهب والصياغة في القرنين 14 و15.

الحرب العالمية الثانية

يكفي النظر إلى لوحة الرسامين السوفيت " كوكرينكسوف " (هروب الفاشست من نوڤگورود) لكي نفهم ماعانته المدينة فترة الاحتلال من اغسطس/اب عام 1941 إلى يناير/كانون ثاني عام 1944 كونها واقعة على خط الجبهة – الخرائب وبقايا المباني واثار الحرائق. كان هذا يعني امكانية الاقرار بنهاية تاريخ المدينة القديمة ومغادرتها والبدء ببناء مدينة جديدة في محل اخر. ولكن الذي حصل هو البدء باعادة البناء وعودة الناس ببطء إلى حياتهم الطبيعية، واضيفت المدينة إلى قائمة المدن التاريخية المهمة في روسيا. واعتمادا على توصيات اللجنة الحكومية المتكونة من علماء ومعماريين مشهورين شكلت ورشات ترميم خاصة.

وفي 7 نوفمبر 1944 والحرب مازالت قائمة افتتح في الكرملين نصب " الف سنة على تاسيس روسيا " الذي فككه الفاشست.

نوڤگورود العصرية

يمتزج في المدينة بنجاح القديم والحديث فبعد الحرب العالمية الثانية اعيد بناء الجزء التاريخي للمدينة بحيث ان معابد العصور الوسطى لم تختفي خلف المباني العصرية العالية. ولكون المدينة واقعة على طريق موسكو – بطرس بورغ فانها ترتبط بعلاقات اقتصادية وثقافية مع العاصمتين وكارليا ودول البلطيق. وتجذب المستثمرين الاجانب.

ونوڤگورود عبارة عن مدينة جامعية، فجامعة يارسلاف الحكيم هي احدى المراكز العلمية الكبيرة في شمال غرب روسيا.

كاتدرائية القديسة صوفيافي عام 1992 وبقرار من منظمة اليونسكو ادرجت المدينة ضمن التراث العالمي.

العلاقات الدولية

المدن الشقيقة

Veliky Novgorod is twinned with:

التكريم

A minor planet, 3799 Novgorod, discovered by Soviet astronomer Nikolai Stepanovich Chernykh in 1979, is named after the city.[37]

انظر أيضاً

الهامش

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qUgzqkCW6A4

ببليوجرافيا

- William Craft Brumfield. A History of Russian Architecture (Seattle: Univ. of Washington Press, 2004) ISBN 9780295983943

الهامش

- ^ According to Article 9 of the Charter of Veliky Novgorod, the symbols of Veliky Novgorod include a flag and a coat of arms but not an anthem.

- ^ أ ب ت ث خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةRef534 - ^ أ ب Charter of Veliky Novgorod, Article 1.

- ^ أ ب Тихомиров, М.Н. (1956). Древнерусские города (in الروسية). Государственное издательство Политической литературы. Retrieved June 13, 2012.

- ^ Official website of Veliky Novgorod. Geographic Location (بالروسية)

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماة2010Census - ^ "Об исчислении времени". Официальный интернет-портал правовой информации (in Russian). 3 June 2011. Retrieved 19 January 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ Почта России. Информационно-вычислительный центр ОАСУ РПО. (Russian Post). Поиск объектов почтовой связи (Postal Objects Search) (in روسية)

- ^ Ketola, Kari; Vihavainen, Timo (2014). Changing Russia? : history, culture and business (1st ed.). Helsinki: Finemor. p. 1. ISBN 978-952712401-7.

- ^ Valentin Lavrentyevich Ianin and Mark Khaimovich Aleshkovsky. "Proskhozhdeniye Novgoroda: (k postanovke problemy)," Istoriya SSSR 2 (1971): 32-61.

- ^ The name Holmgard is a Norse toponym meaning Islet town or Islet grad, and there are various explanations for why they gave this name. According to Rydzevskaya, the Norse name is derived from the Slavic Holmgrad which means "town on a hill" and may allude to the "old town" preceding the "new town", or Novgorod.

- ^ "Vnovgorod.info" Городище (in الروسية). Великий Новгород. Retrieved March 27, 2013.

- ^ Jackson, Tatjana (2015). "Garðaríki and Its Capital: Novgorod on the Mental Map of Medieval Scandinavians". Slověne (in الروسية). Moscow. 4 (1): 170–179. doi:10.31168/2305-6754.2015.4.1.9. Retrieved 2022-06-24. p. 175: "в сознании авторов и их слушателей Хольмгард на всем протяжении сложения и записи саг оставался столицей лежащей за Балтийским морем страны Гарды/Гардарики" [throughout the composition and recording of the sagas, in the minds of the authors and their listeners, Hólmgarðr remained the capital of the country Garðar/Garðaríki across the Baltic Sea]

- ^ Mägi, Marika (2018). In Austrvegr: The Role of the Eastern Baltic in Viking Age Communication across the Baltic Sea. Brill. pp. 160–161. ISBN 9789004363816.

- ^ Rafn, Carl Christian, ed. (1830). "Gaungu-Hrólf Saga". Fornaldar sögur Nordrlanda eptir gömlum handritum (in الأيسلندية). Kaupmannahöfn: Popp. p. 362:

í Hólmgarðaborg er mest atsetr Garðakonúngs, þat er nú kallat Nógarðar

[The main residence of the king of Garðar is in Hólmgarðaborg, which is now called Nógarðar] - ^ Franklin, Simon; Shepard, Jonathan (2014). The Emergence of Russia 750-1200. Routledge. p. 201. ISBN 9781317872245.

- ^ Jackson, Tatjana (2010). "The Cult of St Olaf and Early Novgorod". In Antonsson, Haki; Garipzanov, Ildar H. (eds.). Saints and their Lives on the Periphery: Veneration of Saints in Scandinavia and Eastern Europe (c.1000-1200). Cursor Mundi. Vol. 9. Brepols. pp. 147–167. ISBN 978-2-503-53033-8.

- ^ "The Cronicle of the Hanseatic League". european-heritage.org. Archived from the original on March 7, 2012. Retrieved September 10, 2015.

- ^ Justyna Wubs-Mrozewicz, Traders, ties and tensions: the interactions of Lübeckers, Overijsslers and Hollanders in Late Medieval Bergen, Uitgeverij Verloren, 2008 p. 111

- ^ Translation of the grant of privileges to merchants in 1229: "Medieval Sourcebook: Privileges Granted to German Merchants at Novgorod, 1229". Fordham.edu. Retrieved July 20, 2009.

- ^ Michael C. Paul, "The Iaroslavichi and the Novgorodian Veche 1230–1270: A Case Study on Princely Relations with the Veche", Russian History/ Histoire Russe 31, No. 1-2 (Spring-Summer 2004): 39-59.

- ^ Michael C. Paul, "Secular Power and the Archbishops of Novgorod Before the Muscovite Conquest". Kritika: Explorations in Russian and Eurasian History 8, no. 2 (Spring 2007): 231-270.

- ^ Michael C. Paul, "Episcopal Election in Novgorod, Russia 1156–1478". Church History: Studies in Christianity and Culture 72, No. 2 (June 2003): 251-275.

- ^ Janet Martin, Treasure of the Land of Darkness: the Fur Trade and its Significance for Medieval Russia. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985).

- ^ Janet Martin, “Les Uškujniki de Novgorod: Marchands ou Pirates.” Cahiers du Monde Russe et Sovietique 16 (1975): 5-18.

- ^ Kollmann, Nancy Shields (2017). The Russian Empire 1450-1801. Oxford University Press. p. 50.

- ^ Kazakova, N. A. (1984). "Еще раз о закрытии Ганзейского двора в Новгороде в 1494 г.". Новгородский исторический сборник. 2 (12): 177.

- ^ Boris Zemtsov, Откуда есть пошла... российская цивилизация, Общественные науки и современность. 1994. № 4. С. 51-62. p. 9 (in روسية)

- ^ أ ب Kovalenko, Guennadi (2010). Великий Новгород. Взгляд из Европы XV-XIX centuries (in الروسية). Европейский Дом. pp. 48, 72, 73. ISBN 9785801502373.

- ^ Варенцов, В. А.; Коваленко, Г. М. (1999). В составе Московского государства: очерки истории Великого Новгорода конца XV-начала XVIII в (in الروسية). Русско-Балтийский информационный центр БЛИЦ. ISBN 9785867891008.

- ^ J.T., Russia's Foreign Trade and Economic Expansion in the Seventeenth Century: Windows on the World (2005). Kotilaine. Brill. p. 30. ISBN 9789004138964.

- ^ Варенцов, В. А.; Коваленко, Г. М. (1999). В составе Московского государства: очерки истории Великого Новгорода конца XV-начала XVIII в (in الروسية). Русско-Балтийский информационный центр БЛИЦ. pp. 44, 45. ISBN 9785867891008.

- ^ Варенцов, В. А.; Коваленко, Г. М. (1999). В составе Московского государства: очерки истории Великого Новгорода конца XV-начала XVIII в (in الروسية). Русско-Балтийский информационный центр БЛИЦ. p. 71. ISBN 9785867891008.

- ^ Варенцов, В. А.; Коваленко, Г. М. (1999). В составе Московского государства: очерки истории Великого Новгорода конца XV-начала XVIII в (in الروسية). Русско-Балтийский информационный центр БЛИЦ. pp. 52–60. ISBN 9785867891008.

- ^ Vdovichenko, Marina (2020-02-28). "Medieval Churches in Novgorod: Aspects of archaeological investigations and museum presentation". Internet Archaeology (in الإنجليزية) (54). doi:10.11141/ia.54.10. ISSN 1363-5387. S2CID 213325311.

- ^ "Федеральный закон от 11.06.1999 г. № 111-ФЗ". kremlin.ru.

- ^ Schmadel, Lutz D. (2003). Dictionary of Minor Planet Names (5th ed.). New York: Springer Verlag. p. 321. ISBN 3540002383.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help)

وصلات خارجية

- Novgorod the Great site

- Veliky Novgorod for tourists

- The Faceted Palace of the Kremlin in Novgorod the Great site

- Novgorod - monuments of ancient architecture

- Novgorod the Great for the businessman

- Photos tagged with

novgorodon Flickr, photos likely of Novgorod the Great

بالروسية

- Pages using gadget WikiMiniAtlas

- CS1 uses الروسية-language script (ru)

- CS1 الروسية-language sources (ru)

- Articles with روسية-language sources (ru)

- Articles containing دنماركية-language text

- Articles with text in Slavic languages

- CS1 الأيسلندية-language sources (is)

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Coordinates on Wikidata

- Pages using infobox settlement with image map1 but not image map

- Russian inhabited locality articles with obsolete place names

- Pages using infobox UNESCO World Heritage Site with unknown parameters

- Articles containing روسية-language text

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Articles with unsourced statements from January 2023

- Articles containing نورسية القديمة-language text

- Articles containing Old East Slavic-language text

- Articles containing Church Slavonic-language text

- Articles containing لاتينية-language text

- Articles with unsourced statements from January 2015

- ڤليكي نوڤگورود

- مواقع أثرية في روسيا

- عواصم أمم سابقة

- مدن وبلدات في أبلاست نوڤگورود

- مواقع التراث العالمي في روسيا

- محطات تجارية للعصبة الهانزية

- مستوطنات الروس

- مدن ذات مجد عسكري

- محافظة نوڤگورود

- Rus' settlements

- Novgorodsky Uyezd

- قانون لوبك