العشرينات الهادرة

| جزء من the interwar period | |

Josephine Baker performing the Charleston | |

| التاريخ | 1920s |

|---|---|

| الموقع | Mainly the United States (Equivalents and effects in the greater Western world) |

| ويُعرف أيضاً بـ | Années folles in France Golden Twenties in Germany |

| المشاركون | Social movements First-wave feminism Harlem Renaissance Jazz Age Progressive Era |

| النتائج | Ending events Wall Street Crash of 1929 Repeal of Prohibition in the United States |

| هذا المقال هو جزء من سلسلة عن |

| تاريخ الولايات المتحدة |

|---|

|

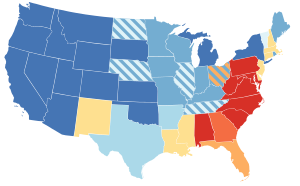

تشير العشرينيات الهادرة (التي يطلق عيها في بعض الأحيان Roarin' 20s) إلى عقد عشرينات القرن الماضي في المجتمع الغربي و الثقافة الغربية . كانت فترة ازدهار اقتصادي مع ميزة ثقافية مميزة في الولايات المتحدة وأوروبا ، لا سيما في المدن الكبرى مثل برلين ،[1] شيكاغو،[2] لندن،[3] لوس أنجلس، كاليفورنيا،[4] نيويورك،[5] باريس,[6] وسيدني.[7] في فرنسا ، عُرف هذا العقد باسم "années folles" أي ('سنوات مجنونة') ،[8]مما يؤكد على الديناميكية الاجتماعية والفنية والثقافية للعصر. ازدهرت موسيقى الجاز ، أعادت المتحررات تعريف المظهر الحديث للمرأة البريطانية والأمريكية،[9][10] وبلغ الفن الزخرفي ذروته.[11] في أعقاب التعبئة العسكرية خلال الحرب العالمية الأولى ، الرئيس وارن هاردنگ " أعاد الأمور إلى طبيعتها" في سياسة الولايات المتحدة. شهدت هذه الفترة تطوراً واسعاً واستخداماً للسيارات والهواتف والأفلام والراديو والأجهزة الكهربائية في حياة الملايين في العالم الغربي. سرعان ما أصبح الطيران عملاً تجارياً. شهدت الأمم نمواً صناعياً واقتصادياً سريعاً ، وتسارع طلب المستهلكين ، وأُدخلت اتجاهات جديدة مهمة في نمط الحياة والثقافة. ركزت وسائل الإعلام ، التي تم تمويلها من قبل الصناعة الجديدة للإعلانات الجماهيرية التي تدفع طلب المستهلكين ، على المشاهير ، وخاصة الأبطال الرياضيين ونجوم السينما ، حيث كانت المدن متأصلة لفرقهم المحلية وملأت دور السينما الفخمة الجديدة والملاعب الرياضية العملاقة. في العديد من الدول الديمقراطية الكبرى ، فازت المرأة بحق التصويت. بدأت السمات الاجتماعية والثقافية المعروفة باسم العشرينات الهادرة في المراكز الحضرية الرئيسية وانتشرت على نطاق واسع في تبعات الحرب العالمية الأولى. اكتسبت الولايات المتحدة الهيمنة في التمويل العالمي. وهكذا ، عندما لم تعد ألمانيا قادرة على تحمل دفع تعويضات الحرب العالمية الأولى إلى المملكة المتحدة وفرنسا وقوى الحلفاء الأخرى ، توصلت الولايات المتحدة إلى خطة دوز ، والتي سميت على اسم مصرفي وبعدها نائب الرئيس الثلاثين تشارلز گيتس دوز . استثمرت وول ستريت بكثافة في ألمانيا ، التي دفعت تعويضاتها إلى البلدان التي بدورها استخدمت الدولارات لسداد ديونها الحربية لواشنطن. بحلول منتصف العقد ، انتشر الازدهار على نطاق واسع ، حيث عُرف النصف الثاني من العقد ، خاصة في ألمانيا ، باسم "العشرينيات الذهبية".[12]

تميزت روح العشرينيات بشعور عام بالتجديد المرتبط بـ الحداثة والابتعاد عن التقاليد. بدا كل شيء ممكناً من خلال التكنولوجيا الحديثة مثل السيارات ، الصور المتحركة ، و الراديو ، التي جلبت "الحداثة" إلى جزء كبير من السكان. تم استخدام الرتوش الزخرفية الرسمية لصالح التطبيق العملي في كل من الحياة اليومية والهندسة المعمارية. في الوقت نفسه ، ارتفعت شعبية موسيقي الجاز والرقص ، على عكس الحالة المزاجية السائدة خلال الحرب العالمية الأولى. على هذا النحو ، غالباً ما يشار إلى الفترة باسم عصر الجاز. أنهى انهيار وال ستريت 1929 العصر ، حيث جلب الكساد الكبير سنوات من المشقة في جميع أنحاء العالم.[13]

الاقتصاد

كانت العشرينات الهادرة عقداً من النمو الاقتصادي والازدهار على نطاق واسع ، مدفوعاً بالتعافي من دمار الحرب والإنفاق المؤجل ، والازدهار في البناء ، والنمو السريع لـ السلع الاستهلاكية مثل السيارات والكهرباء في أمريكا الشمالية وأوروبا وعدد قليل من البلدان المتقدمة الأخرى مثل أستراليا.[15]ازدهر اقتصاد الولايات المتحدة ، الذي انتقل بنجاح من اقتصاد زمن الحرب إلى اقتصاد زمن السلم ، وقدم قروضاً للازدهار الأوروبي أيضاً. بعض القطاعات ركدت ، خاصة الزراعة وتعدين الفحم. أصبحت الولايات المتحدة أغنى دولة بالنسبة لدخل الفرد في العالم ومنذ أواخر القرن التاسع عشر كانت أكبر دولة في إجمالي الناتج المحلي. كانت صناعتها تقوم على انتاج بالجملة ، وثقافة مجتمعها استهلاكية. على النقيض من ذلك ، شهدت الاقتصادات الأوروپية عملية إعادة تكيف أكثر صعوبة بعد الحرب ولم تبدأ في الازدهار حتى عام 1924 قريباً.[16]

في البداية ، تسببت نهاية الإنتاج في زمن الحرب في ركود قصير ولكن عميق ، ركود ما بعد الحرب العالمية الأولى من 1919-1920. ومع ذلك ، سرعان ما انتعشت اقتصادات الولايات المتحدة وكندا مع عودة الجنود العائدين إلى القوى العاملة وإعادة تجهيز مصانع الذخيرة لإنتاج السلع الاستهلاكية.

منتجات وتقنيات جديدة

الانتاج بالجملة جعل التكنولوجيا في متناول الطبقة المتوسطة.[16] انطلقت صناعة السيارات وصناعة الأفلام وصناعة الراديو والصناعات الكيماوية خلال عشرينيات القرن الماضي.

السيارات

قبل الحرب العالمية الأولى ، كانت السيارات سلعة فاخرة. في عشرينيات القرن الماضي ، أصبحت السيارات ذات الإنتاج الضخم شائعة في الولايات المتحدة وكندا. بحلول عام 1927 ، أوقفت شركة فورد للسيارات فورد موديل تي بعد بيع 15 مليون وحدة من هذا الطراز. حيث كانت في إنتاج مستمر من أكتوبر 1908 إلى مايو 1927.[17][18] خططت الشركة لاستبدال الطراز القديم بأحدث ، فورد موديل أي .[19] كان القرار رد فعل على المنافسة. نظراً للنجاح التجاري للطراز تي ، سيطرت شركة فورد على سوق السيارات من منتصف العقد الأول من القرن العشرين إلى أوائل العشرينات من القرن الماضي. إلا أنه في منتصف العشرينات من القرن الماضي ، تآكلت هيمنة فورد حيث لحق منافسوها بنظام الإنتاج الضخم من فورد. وبدأوا في التفوق على فورد في بعض المجالات ، حيث قدموا نماذج ذات محركات أكثر قوة ، وميزات راحة وتصميم جديد .[20][21][22]

تم تسجيل حوالي 300000 سيارة فقط في عام 1918 في جميع أنحاء كندا ، ولكن بحلول عام 1929 ، كان هناك 1.9 مليون. بحلول عام 1929 ، كان لدى الولايات المتحدة أقل بقليل من 27.000.000[23] سيارة مسجلة. تم تصنيع قطع غيار السيارات في أونتاريو ، بالقرب من ديترويت ، ميشيغان. كان تأثير صناعة السيارات على القطاعات الأخرى من الاقتصاد واسع الانتشار ، حيث بدأت الصناعات مثل إنتاج الصلب ، وبناء الطرق السريعة ، والموتيلات ، ومحطات الخدمة ، وتجار السيارات ، والمساكن الجديدة خارج قلب المدينة. افتتحت فورد مصانع حول العالم وأثبتت أنها منافس قوي في معظم الأسواق لمركباتها منخفضة التكلفة وسهلة الصيانة. وتبعتها جنرال موتورز ، بدرجة أقل. تجنب المنافسون الأوروبيون السوق منخفضة السعر وركزوا على السيارات الأكثر تكلفة للمستهلكين الراقيين.[24]

الإذاعة

أصبحت الإذاعة أول وسيلة بث جماهيري. كانت أجهزة الراديو باهظة الثمن ، لكن أسلوبها في الترفيه أثبت أنه ثوري. أصبح الإعلان الإذاعي منصة لـ التسويق الشامل. أدت أهميتها الاقتصادية إلى الثقافة الجماهيرية التي هيمنت على المجتمع منذ هذه الفترة. خلال "العصر الذهبي للراديو" ، كانت البرامج الإذاعية متنوعة مثل البرامج التلفزيونية في القرن الحادي والعشرين. قدم إنشاء لجنة الراديو الفيدرالية في عام 1927 حقبة جديدة من التنظيم. في عام 1925 ، أصبح التسجيل الكهربائي ، وهو أحد أكبر التطورات في التسجيل الصوتي ، متاحاً مع تسجيلات الجراموفون الصادرة تجارياً.

السينما

ازدهرت السينما ، وأنتجت شكلاً جديداً من الترفيه أنهى تقريباً النوع المسرحي القديم ڤودڤيل. كانت مشاهدة الفيلم رخيصة ومتاحة؛ حيث اندفعت الحشود إلى قصور الأفلام وسط المدينة والمسارح المجاورة. منذ أوائل العقد الأول من القرن العشرين ، نجحت السينما منخفضة السعر في التنافس مع الڤودڤيل. تم تجنيد العديد من فناني الڤودڤيل وغيرهم من الشخصيات المسرحية من قبل صناعة السينما ، حيث أغرتهم رواتب أعلى وظروف عمل أقل صعوبة. أدى تقديم السينما الناطقة ، المعروفة أيضاً باسم "the talkies" التي لم ترتفع حتى نهاية عقد العشرينيات من القرن الماضي ، إلى القضاء على الميزة الرئيسية الأخيرة لڤودڤيل وجعلها في حالة تدهور مالي حاد. استحوذ استوديو أفلام جديد على دائرة أورفيوم المرموقة ، وهي سلسلة من مسارح الڤودڤيل ودور السينما .[25]

السينما الناطقة

في عام 1923 أصدر المخترع لي دي فورست في فونوفيلم عدداً من الأفلام القصيرة مع الصوت. في غضون ذلك ، طور المخترع ثيودور كيس نظام صوت موڤيتون وباع حقوق الاستوديو لـويليام فوكس. في عام 1926 ، تم تقديم نظام الصوت ڤيتافون. كان الفيلم الروائي دون جوان (1926) أول فيلم روائي طويل يستخدم نظام الصوت ڤيتافون مع نغمة موسيقية وتأثيرات صوتية متزامنة ، على الرغم من عدم وجود حوار منطوق.[26] تم إصدار الفيلم من قبل استوديو الأفلام وارنر برذرز في أكتوبر 1927 ، وتحول الفيلم الصوتي مغني الجاز (1927) إلى نجاح ساحق في شباك التذاكر، فقد كان مبتكراً لاستخدامه الصوت. تم إنتاجه بنظام ڤيتافون ، ومعظم الفيلم لا يحتوي على تسجيل صوتي مباشر ، بل يعتمد على النتيجة والتأثيرات. عندما يغني نجم الفيلم آل جولسون ، يتحول الفيلم إلى الصوت المسجل في المجموعة ، بما في ذلك عروضه الموسيقية ومشهدين يحملان خطاباً - أحد شخصيات جولسون ، جاكي رابينوفيتز (جاك روبن) ، يخاطب جمهور الملهى ؛ المشهد الآخر بينه وبين والدته. وكانت الأصوات "الطبيعية" للإعدادات مسموعة أيضاً.[27] أصبحت أرباح الفيلم دليلاً كافياً لصناعة السينما على أن التكنولوجيا تستحق الاستثمار فيها.[28]

في عام 1928 ، وقّعت استديوهات الأفلام فيموس پلايرز- لاسكي (عُرفت لاحقاً باسم پاراماونت پيكتشرز) ، فرست ناشيونال ، مترو-گولدوين-ماير ، و استوديوهات يونيڤرسال اتفاقية مع شركة منتجات البحوث الكهربائية (ERPI) لتحويل مرافق الإنتاج والمسارح للأفلام الصوتية. في البداية ، تم جعل جميع مسارح ERPI السلكية متوافقة مع ڤيتافون؛ وتم تجهيز معظمهم لعرض بكرات موفيتون أيضاً.[29] أيضاً في عام 1928 ، قامت شركة راديو أمريكا (RCA) بتسويق نظام صوتي جديد ، وهو نظام RCA فوتوفون. عرضت RCA حقوق نظامها على الشركة الفرعية آر كي أو پيكتشرز. واصلت شركة وارنر برذرز إطلاق بعض الأفلام من خلال الحوار المباشر ، وإن كان ذلك في بعض المشاهد فقط. أصدرت أخيراً أضواء نيويورك (1928) ، وهو أول فيلم طويل كامل كامل الحديث. كان فيلم الرسوم المتحركة القصير وقت العشاء (1928) من إنتاج استوديوهات ڤان بورين من بين أولى أفلام الرسوم المتحركة الصوتية. تبع ذلك بعد بضعة أشهر فيلم الرسوم المتحركة القصير ستيمبوت ويلي (1928) ، وهو أول فيلم صوتي من إنتاج استوديوهات والت ديزني للرسوم المتحركة. كان أول فيلم رسوم متحركة قصير ناجح تجارياً وقدم شخصية ميكي ماوس. [30]كان فيلم ستيمبوت ويلي أول كارتون يعرض مقطعاً صوتياً تم إنتاجه بالكامل ، الأمر الذي ميزه عن الرسوم الكاريكاتورية الصوتية السابقة. أصبحت الرسوم الكاريكاتورية الأكثر شعبية في ذلك الوقت. [31]

لمعظم عام 1928 ، وارنر برذرز كان الاستوديو الوحيد الذي أصدر ميزات التحدّث. واستفادت الشركة من أفلامها المبتكرة في شباك التذاكر. وسرّعت الاستوديوهات الأخرى من وتيرة تحولها إلى التكنولوجيا الجديدة وبدأت في إنتاج أفلامها الصوتية وأفلامها الناطقة. في فبراير 1929 ، بعد ستة عشر شهراً من مغني الجاز، أصبح كولومبيا پيكتشرز ثامن وآخر استوديو كبير يطلق ميزة التحدّث. في مايو 1929 ، أصدر وارنر برذرز مع العرض! (1929) ، أول فيلم روائي طويل شامل كل الألوان.[32] سرعان ما توقف إنتاج الفيلم الصامت. آخر فيلم صامت تماماً تم إنتاجه في الولايات المتحدة للتوزيع العام كان المليونير الفقير ، الذي أصدره شركة بيلتيمور بيكتشرز في أبريل 1930. كما تم إطلاق أربع أفلام صامتة أخرى ، جميعها أفلام ويسترن منخفضة الميزانية في أوائل عام 1930. [33]

الطيران

شهدت العشرينيات من القرن الماضي معالم بارزة في مجال الطيران استحوذت على اهتمام العالم. في عام 1927 ، اشتهر تشارلز لندبرگ بأول رحلة عبر المحيط الأطلسي فردية وغير متوقفة. أقلع من روزڤلت فيلد في نيويورك وهبط في مطار پاريس-لو بورجيه. استغرق لندبرگ 33.5 ساعة لعبور المحيط الأطلسي. [34]كانت طائرته ، سپيريت أوف سانت لويس ، طائرة أحادية السطح مصنوعة خصيصاً، ذات محرك واحد ، بمقعد واحد . وقد صممت بواسطة مهندس طيران دونالد آي هال. في بريطانيا ، تعد إيمي جونسون (1903-1941) أول امرأة تسافر بمفردها من بريطانيا إلى أستراليا. كانت تحلق بمفردها أو مع زوجها ، جيم موليسون ، وقد سجلت العديد من الأرقام القياسية للمسافات الطويلة خلال الثلاثينيات.[35]

التلفاز

شهدت العشرينات من القرن الماضي تقدم العديد من المخترعين في العمل على التلفزيون ، لكن البرامج لم تصل إلى الجمهور حتى عشية الحرب العالمية الثانية ، وقليل من الناس شاهدوا أي تلفزيون قبل أواخر الأربعينيات.

في يوليو 1928 ، عرض جون لوجي بيرد أول إرسال للون في العالم ، باستخدام أقراص مسح عند طرفي الإرسال والاستقبال بثلاث فتحات لولبية ، كل لولب مع مرشح من لون أساسي مختلف ؛ وثلاثة مصادر للضوء في الطرف المستقبل ، مع مبادل لتبديل الإضاءة.[36] في نفس العام ، عرض أيضاً مجسماً للتلفزيون. [37]

في عام 1927 ، أرسل بيرد إشارة تليفزيونية بعيدة المدى عبر 438 ميل (705 km) من خط الهاتف بين لندن وجلاسكو ؛ نقل بيرد أول صور تلفزيونية بعيدة المدى في العالم إلى فندق سنترال في محطة غلاسكو المركزية. [38]ثم أنشأ بيرد شركة تطوير تلفزيون بيرد المحدودة ، التي قامت في عام 1928 بأول بث تلفزيوني عبر المحيط الأطلسي ، من لندن إلى هارتسديل ، نيويورك وقدمت أول برنامج تلفزيوني لهيئة الإذاعة البريطانية. [39]

الطب

لعقود من الزمان ، عمل علماء الأحياء على الدواء الذي أصبح الپنسلين. في عام 1928 ، اكتشف عالم الأحياء الاسكتلندي ألكسندر فلمنگ مادة قتلت عددًا من الجراثيم المسببة للأمراض . في عام 1929 ، أطلق على المادة الجديدة پنسلين. تم تجاهل اكتشافه إلى حد كبير في البداية ، لكنه أصبح مضاداً حيوياً مهماً في الثلاثينيات. في عام 1930 ، استخدم سيسيل جورج باين ، أخصائي علم الأمراض في مستشفى شيفيلد الملكي ، الپنسلين لعلاج داء باربي ، وهو الانفجارات في بصيلات اللحية ، لكنه لم ينجح. بالانتقال إلى الرمد الوليدي ، وهو عدوى بالمكورات البنية عند الرضع ، تحقق أول علاج مسجل بالبنسلين ، في 25 نوفمبر 1930. ثم عالج أربعة مرضى إضافيين (شخص بالغ وثلاثة أطفال رضع) من التهابات العين ، لكنه فشل في علاج الخامس.[40][41][42]

بنية تحتية جديدة

أدت هيمنة السيارة إلى علم نفس جديد يحتفي بالتنقل. [43] احتاجت السيارات والشاحنات إلى بناء طرق وجسور جديدة وصيانة منتظمة للطرق السريعة ، ممولة بشكل كبير من قبل الحكومة المحلية وحكومة الولاية من خلال الضرائب على البنزين. كان المزارعون من أوائل المتبنين لأنهم استخدموا سياراتهم الصغيرة لنقل الأشخاص والإمدادات والحيوانات. نشأت صناعات جديدة - لتصنيع الإطارات والزجاج وصقل الوقود ، وخدمة وإصلاح السيارات والشاحنات بالملايين. تم منح الامتياز لتجار السيارات الجديدة من قبل صانعي السيارات وأصبحوا المحركين الرئيسيين في مجتمع الأعمال المحلي. اكتسبت السياحة دفعة هائلة ، مع انتشار الفنادق والمطاعم ومحلات التحف. [44][45]

تقدمت الكهرباء ، بعد أن تباطأت أثناء الحرب ، بشكل كبير مع إضافة المزيد من الولايات المتحدة وكندا إلى الشبكة الكهربائية. تحولت الصناعات من الفحم إلى الكهرباء. في نفس الوقت ، تم بناء محطات كهرباء جديدة لتوليد الطاقة. في أمريكا ، وتضاعف إنتاج الكهرباء أربع مرات تقريبًا. [46]

كما تم مد خطوط الهاتف عبر القارة. وتم تركيب السباكة الداخلية لأول مرة في العديد من المنازل ، وذلك بفضل أنظمة الصرف الصحي الحديث. بلغ التحضر علامة فارقة في تعداد عام 1920 ، وأظهرت نتائج ذلك أن عدد الأمريكيين الذين يعيشون في المناطق الحضرية والبلدات والمدن ، التي يسكنها 2500 شخص أو أكثر ، يزيد قليلاً عن البلدات الصغيرة أو المناطق الريفية. ومع ذلك ، كانت الأمة مفتونة بمراكزها الحضرية الكبرى التي تضم حوالي 15 ٪ من السكان. تنافست مدينتا نيويورك وشيكاغو في بناء ناطحات سحاب ، وتقدمت نيويورك في مبنى إمپاير ستيت. تم تحديد النمط الأساسي لوظيفة ذوي الياقات البيضاء في أواخر القرن التاسع عشر ، لكنه أصبح الآن هو المعيار للحياة في المدن الكبيرة والمتوسطة الحجم. جلبت الآلات الكاتبة وخزائن الملفات والهواتف العديد من النساء غير المتزوجات إلى وظائف مكتبية. في كندا ، بحلول نهاية العقد ، كان واحد من كل خمسة عمال من النساء. أصبح الاهتمام بالعثور على وظائف ، في قطاع التصنيع المتنامي الآن في المدن الأمريكية ، واسع الانتشار بين الأمريكيين الريفيين.[47]

المجتمع

حق الاقتراع

مع بعض الاستثناءات ، [48] قامت العديد من البلدان بتوسيع حقوق المرأة في الاقتراع في الديمقراطيات التمثيلية والمباشرة عبر العالم مثل الولايات المتحدة وكندا وبريطانيا العظمى ومعظم الدول الأوروبية الكبرى في 1917-1921 ، وكذلك الهند. وقد أثر ذلك على العديد من الحكومات والانتخابات من خلال زيادة عدد الناخبين. ورد السياسيون بالتركيز أكثر على القضايا التي تهم المرأة ، لا سيما السلام والصحة العامة والتعليم ووضع الأطفال. بشكل عام ، صوتت النساء مثل الرجال ، إلا أنهن كن أكثر اهتمامًا بالسلام. [49][50][51][52]

الجيل الضائع

تألف الجيل الضائع من الشباب الذين خرجوا من الحرب العالمية الأولى بخيبة أمل وسخرية من العالم. يشير المصطلح عادة إلى وجهاء الأدب الأمريكيين الذين عاشوا في باريس في ذلك الوقت. من بين الأعضاء المشهورين إرنست همنگواي ، فرانسس سكت فتسجرالد و گيرترود ستاين. وكتب هؤلاء المؤلفون ومنهم مغتربون روايات وقصص قصيرة تعبر عن استيائهم من المادية والفردية التي انتشرت في هذه الحقبة. في المملكة المتحدة ، كان الشباب الساطع من الأرستقراطيين والاشتراكيين الذين أقاموا حفلات تنكرية ، وذهبوا في عمليات البحث عن الكنوز ، وشوهدوا في جميع الأماكن العصرية ، وتناولتهم أعمدة الشائعات بكثرة في صحف لندن. [53]

النقد الاجتماعي

عندما أصبح المواطن الأمريكي العادي في عشرينيات القرن الماضي أكثر حبًا للثروة والكماليات اليومية ، بدأ البعض في التهكم من النفاق والجشع الذي لاحظوه. من بين هؤلاء النقاد الاجتماعيين ، كان سنكلير لويس الأكثر شعبية. روايته الشهيرة عام 1920 الشارع الرئيسي سخرت من الحياة الباهتة والجاهلة لسكان بلدة في الغرب الأوسط. تبعها برواية بابيت ، عن رجل أعمال متوسط العمر يتمرد على حياته وعائلته البائسة ، فقط ليدرك أن جيل الشباب منافق مثل جيله. سخر لويس من الدين مع إلمر گانتري ، التي يتتبع خلالها رجل محتال يتعاون مع مبشر لبيع الدين لمدينة صغيرة.

من بين النقاد الاجتماعيين الآخرين شيروود أندرسون و إديث وارتون و هنري لويس منكن. نشر أندرسون مجموعة من القصص القصيرة بعنوان واينزبيرگ ، أوهايو ، والتي درست ديناميكيات بلدة صغيرة. سخرت وارتن من بدع العصر الجديد من خلال رواياتها مثل نوم الشفق (1927). انتقد منكن الأذواق والثقافة الأمريكية الضيقة في المقالات والأعمدة الصحفية.

الفن الزخرفي

كان الفن الزخرفي (آرت ديكو) هو أسلوب التصميم والعمارة الذي ميز تلك الحقبة. نشأ في أوروبا ، وانتشر إلى بقية أوروبا الغربية وأمريكا الشمالية في منتصف عشرينيات القرن الماضي.

في الولايات المتحدة ، تم تشييد أحد المباني الرائعة التي تتميز بهذا الطراز كـ أطول مبنى في ذلك الوقت: مبنى كرايسلر. كانت أشكال الفن الزخرفي نقية وهندسية ، على الرغم من أن الفنانين غالبًا ما استلهموا من الطبيعة. في البداية ، كانت الخطوط منحنية ، ومع ذلك أصبحت التصميمات المستقيمة فيما بعد أكثر شيوعًا.

التعبيرية والسوريالية

تطور الرسم في أمريكا الشمالية خلال عشرينيات القرن الماضي في اتجاه مختلف عن اتجاه أوروبا. في أوروبا ، كانت العشرينيات عصر التعبيرية ولاحقًا السوريالية. كما ذكر مان راي في عام 1920 بعد نشر عدد فريد من نيويورك دادا: "دادا لا يمكن أن تعيش في نيويورك".

Cinema

At the beginning of the decade, films were silent and colorless. In 1922, the first all-color feature, The Toll of the Sea, was released. In 1926, Warner Bros. released Don Juan, the first feature with sound effects and music. In 1927, Warner released The Jazz Singer, the first sound feature to include limited talking sequences.

The public went wild for sound films, and movie studios converted to sound almost overnight.[54] In 1928, Warner released Lights of New York, the first all-talking feature film. In the same year, the first sound cartoon, Dinner Time, was released. Warner ended the decade by unveiling On with the Show in 1929, the first all-color, all-talking feature film.

Cartoon shorts were popular in movie theaters during this time. In the late 1920s, Walt Disney emerged. Mickey Mouse made his debut in Steamboat Willie on November 18, 1928, at the Colony Theater in New York City. Mickey was featured in more than 120 cartoon shorts, the Mickey Mouse Club, and other specials. This started Disney and led to creation of other characters going into the 1930s.[55] Oswald the Lucky Rabbit, a character created by Disney, before Mickey, in 1927, was contracted by Universal for distribution purposes, and starred in a series of shorts between 1927 and 1928. Disney lost the rights to the character, but in 2006, regained the rights to Oswald. He was the first Disney character to be merchandised.[56]

The period had the emergence of box-office draws such as Mae Murray, Ramón Novarro, Rudolph Valentino, Charlie Chaplin, Buster Keaton, Harold Lloyd, Warner Baxter, Clara Bow, Louise Brooks, Baby Peggy, Bebe Daniels, Billie Dove, Dorothy Mackaill, Mary Astor, Nancy Carroll, Janet Gaynor, Charles Farrell, William Haines, Conrad Nagel, John Gilbert, Greta Garbo, Dolores del Río, Norma Talmadge, Colleen Moore, Nita Naldi, Leatrice Joy, John Barrymore, Norma Shearer, Joan Crawford, Mary Pickford, Douglas Fairbanks, Anna May Wong, and Al Jolson.[57]

Harlem

African-American literary and artistic culture developed rapidly during the 1920s under the banner of the "Harlem Renaissance". In 1921, the Black Swan Corporation was founded. At its height, it issued 10 recordings per month. All-African American musicals also started in 1921. In 1923, the Harlem Renaissance Basketball Club was founded by Bob Douglas. During the late-1920s, and especially in the 1930s, the basketball team became known as the best in the world.

The first issue of Opportunity was published. The African American playwright Willis Richardson debuted his play The Chip Woman's Fortune at the Frazee Theatre (also known as the Wallacks theatre).[1] Notable African American authors such as Langston Hughes and Zora Neale Hurston began to achieve a level of national public recognition during the 1920s.

Jazz Age

The 1920s brought new styles of music into the mainstream of culture in avant-garde cities. Jazz became the most popular form of music for youth.[58] Historian Kathy J. Ogren wrote that, by the 1920s, jazz had become the "dominant influence on America's popular music generally" [59] Scott DeVeaux argues that a standard history of jazz has emerged such that: "After an obligatory nod to African origins and ragtime antecedents, the music is shown to move through a succession of styles or periods: New Orleans jazz up through the 1920s, swing in the 1930s, bebop in the 1940s, cool jazz and hard bop in the 1950s, free jazz and fusion in the 1960s.... There is substantial agreement on the defining features of each style, the pantheon of great innovators, and the canon of recorded masterpieces."[60]

The pantheon of performers and singers from the 1920s include Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, Sidney Bechet, Jelly Roll Morton, Joe "King" Oliver, James P. Johnson, Fletcher Henderson, Frankie Trumbauer, Paul Whiteman, Roger Wolfe Kahn, Bix Beiderbecke, Adelaide Hall and Bing Crosby. The development of urban and city blues also began in the 1920s with performers such as Bessie Smith and Ma Rainey. In the latter part of the decade, early forms of country music were pioneered by Jimmie Rodgers, The Carter Family, Uncle Dave Macon, Vernon Dalhart, and Charlie Poole.[61]

Dance

Dance clubs became enormously popular in the 1920s. Their popularity peaked in the late 1920s and reached into the early 1930s. Dance music came to dominate all forms of popular music by the late 1920s. Classical pieces, operettas, folk music, etc., were all transformed into popular dancing melodies to satiate the public craze for dancing. For example, many of the songs from the 1929 Technicolor musical operetta "The Rogue Song" (starring the Metropolitan Opera star Lawrence Tibbett) were rearranged and released as dancing music and became popular dance club hits in 1929.

Dance clubs across the U.S.-sponsored dancing contests, where dancers invented, tried and competed with new moves. Professionals began to hone their skills in tap dance and other dances of the era throughout the stage circuit across the United States. With the advent of talking pictures (sound film), musicals became all the rage and film studios flooded the box office with extravagant and lavish musical films. The representative was the musical Gold Diggers of Broadway, which became the highest-grossing film of the decade. Harlem played a key role in the development of dance styles. Several entertainment venues attracted people of all races. The Cotton Club featured black performers and catered to a white clientele, while the Savoy Ballroom catered to a mostly black clientele. Some religious moralists preached against "Satan in the dance hall" but had little impact.[62]

The most popular dances throughout the decade were the foxtrot, waltz, and American tango. From the early 1920s, however, a variety of eccentric novelty dances were developed. The first of these were the Breakaway and Charleston. Both were based on African American musical styles and beats, including the widely popular blues. The Charleston's popularity exploded after its feature in two 1922 Broadway shows. A brief Black Bottom craze, originating from the Apollo Theater, swept dance halls from 1926 to 1927, replacing the Charleston in popularity.[63] By 1927, the Lindy Hop, a dance based on Breakaway and Charleston and integrating elements of tap, became the dominant social dance. Developed in the Savoy Ballroom, it was set to stride piano ragtime jazz. The Lindy Hop later evolved into other Swing dances.[64] These dances, nonetheless, never became mainstream, and the overwhelming majority of people in Western Europe and the U.S. continued to dance the foxtrot, waltz, and tango throughout the decade.[65]

The dance craze had a large influence on popular music. Large numbers of recordings labeled as foxtrot, tango, and waltz were produced and gave rise to a generation of performers who became famous as recording artists or radio artists. Top vocalists included Nick Lucas, Adelaide Hall, Scrappy Lambert, Frank Munn, Lewis James, Chester Gaylord, Gene Austin, James Melton, Franklyn Baur, Johnny Marvin, Annette Hanshaw, Helen Kane, Vaughn De Leath, and Ruth Etting. Leading dance orchestra leaders included Bob Haring, Harry Horlick, Louis Katzman, Leo Reisman, Victor Arden, Phil Ohman, George Olsen, Ted Lewis, Abe Lyman, Ben Selvin, Nat Shilkret, Fred Waring, and Paul Whiteman.[66]

الموضة

الملابس

حددت باريس اتجاهات الموضة لأوروبا وأمريكا الشمالية. [67] كانت أزياء النساء فضفاضة. ارتدت النساء الفساتين طوال اليوم وكل يوم. كانت الفساتين النهارية ذات خصر متدلي ، وهي عبارة عن وشاح أو حزام حول الخصر المنخفض أو الورك وتنورة تتدلى بين الركبة والكاحل ، وليس فوقها أبدًا. ملابس النهار لها أكمام (طويلة إلى منتصف الذراع) وتنورة مستقيمة أو مطوية أو ذات حاشية متدلية أو مبتذلة. وكانت المجوهرات أقل وضوحا. [68] كان الشعر معقوص في كثير من الأحيان ، مما يعطي شكلا صبيانيا.[69]

بالنسبة للرجال في وظائف عمال الياقات البيضاء ، كانت البدلات التجارية هي الملابس اليومية. كانت البدلات المخططة أو المنقوشة أو المزخرفة تأتي باللون الرمادي الداكن والأزرق والبني في الشتاء والعاج والأبيض والتان والباستيل في الصيف. وكانت القمصان بيضاء وربطات العنق ضرورية. [70]

خلّدت أزياء الشابات في العشرينيات من القرن الماضي في الأفلام وأغلفة المجلات ، حيث حددت اتجاهًا وتصريحا اجتماعيًا ، وانفصالًا عن أسلوب الحياة الڤيكتوري الجامد . تخلصت هؤلاء النساء الشابات المتمردين من الطبقة الوسطى ، اللواتي وصفتهن الأجيال الأكبر سناً بـ 'المتحررات' ، من الكورسيه وارتدين فساتين بطول الركبة ، والتي كشفت عن أرجلهم وأذرعهم. كانت تصفيفة الشعر في ذلك العقد عبارة عن شعر قصير بطول الذقن ، والذي كان له العديد من الاختلافات الشائعة. أصبحت مستحضرات التجميل ، التي لم يتم قبولها عادة في المجتمع الأمريكي حتى عشرينيات القرن الماضي بسبب ارتباطها بـ الدعارة ، شائعة للغاية. [71]

في العشرينيات من القرن الماضي ، جذبت المجلات الجديدة الشابات الألمانيات بصور حسية وإعلانات عن الملابس والإكسسوارات المناسبة التي يرغبن في شرائها. عرضت صفحات مجلات Die Dame و Das Blatt der Hausfrau اللامعة "Neue Frauen" ، "الفتاة الجديدة" - التي أطلق عليها الأمريكيون اسم المتحررات. كانت شابة وعصرية ومستقلة مالياً ومستهلكة شغوفة لأحدث صيحات الموضة. أبقتها المجلات على اطلاع دائم على الأنماط والملابس والمصممين والفنون والرياضة والتكنولوجيا الحديثة مثل السيارات والهواتف.[72]

Sexuality of women during the 1920s

The 1920s was a period of social revolution, coming out of World War I, society changed as inhibitions faded and youth demanded new experiences and more freedom from old controls. Chaperones faded in importance as "anything goes" became a slogan for youth taking control of their subculture.[73] A new woman was born—a "flapper" who danced, drank, smoked and voted. This new woman cut her hair, wore make-up, and partied. She was known for being giddy and taking risks.[74] Women gained the right to vote in most countries. New careers opened for single women in offices and schools, with salaries that helped them to be more independent.[75] With their desire for freedom and independence came change in fashion.[76] One of the more dramatic post-war changes in fashion was the woman's silhouette; the dress length went from floor length to ankle and knee length, becoming more bold and seductive. The new dress code emphasized youth: Corsets were left behind and clothing was looser, with more natural lines. The hourglass figure was not popular anymore, and a slimmer, boyish body type was considered appealing. The flappers were known for this and for their high spirits, flirtation, and recklessness when it came to the search for fun and thrills.[77]

Coco Chanel was one of the more enigmatic fashion figures of the 1920s. She was recognized for her avant-garde designs; her clothing was a mixture of wearable, comfortable, and elegant. She was the one to introduce a different aesthetic into fashion, especially a different sense for what was feminine, and based her design on new ethics; she designed for an active woman, one that could feel at ease in her dress.[78] Chanel's primary goal was to empower freedom. She was the pioneer for women wearing pants and for the little black dress, which were signs of a more independent lifestyle.

The changing role of women

Most British historians depict the 1920s as an era of domesticity for women with little feminist progress, apart from full suffrage which came in 1928.[79] On the contrary, argues Alison Light, literary sources reveal that many British women enjoyed:

... the buoyant sense of excitement and release which animates so many of the more broadly cultural activities which different groups of women enjoyed in this period. What new kinds of social and personal opportunity, for example, were offered by the changing cultures of sport and entertainment ... by new patterns of domestic life ... new forms of a household appliance, new attitudes to housework?[80]

With the passage of the 19th Amendment in 1920, that gave women the right to vote, American feminists attained the political equality they had been waiting for. A generational gap began to form between the "new" women of the 1920s and the previous generation. Prior to the 19th Amendment, feminists commonly thought women could not pursue both a career and a family successfully, believing one would inherently inhibit the development of the other. This mentality began to change in the 1920s, as more women began to desire not only successful careers of their own, but also families.[81] The "new" woman was less invested in social service than the Progressive generations, and in tune with the consumerist spirit of the era, she was eager to compete and to find personal fulfillment.[82] Higher education was rapidly expanding for women. Linda Eisenmann claims, "New collegiate opportunities for women profoundly redefined womanhood by challenging the Victorian belief that men's and women's social roles were rooted in biology."[83]

Advertising agencies exploited the new status of women, for example in publishing automobile ads in women's magazines, at a time when the vast majority of purchasers and drivers were men. The new ads promoted new freedoms for affluent women while also suggesting the outer limits of the new freedoms. Automobiles were more than practical devices. They were also highly visible symbols of affluence, mobility, and modernity. The ads, wrote Einav Rabinovitch-Fox, "offered women a visual vocabulary to imagine their new social and political roles as citizens and to play an active role in shaping their identity as modern women".[84]

Significant changes in the lives of working women occurred in the 1920s. World War I had temporarily allowed women to enter into industries such as chemical, automobile, and iron and steel manufacturing, which were once deemed inappropriate work for women.[85] Black women, who had been historically closed out of factory jobs, began to find a place in industry during World War I by accepting lower wages and replacing the lost immigrant labor and in heavy work. Yet, like other women during World War I, their success was only temporary; most black women were also pushed out of their factory jobs after the war. In 1920, 75% of the black female labor force consisted of agricultural laborers, domestic servants, and laundry workers.[86]

Legislation passed at the beginning of the 20th century mandated a minimum wage and forced many factories to shorten their workdays. This shifted the focus in the 1920s to job performance to meet demand. Factories encouraged workers to produce more quickly and efficiently with speedups and bonus systems, increasing the pressure on factory workers. Despite the strain on women in the factories, the booming economy of the 1920s meant more opportunities even for the lower classes. Many young girls from working-class backgrounds did not need to help support their families as prior generations did and were often encouraged to seek work or receive vocational training which would result in social mobility.[87]

The achievement of suffrage led to feminists refocusing their efforts towards other goals. Groups such as the National Women's Party continued the political fight, proposing the Equal Rights Amendment in 1923 and working to remove laws that used sex to discriminate against women,[88] but many women shifted their focus from politics to challenge traditional definitions of womanhood.

Young women, especially, began staking claim to their own bodies and took part in a sexual liberation of their generation. Many of the ideas that fueled this change in sexual thought were already floating around New York intellectual circles prior to World War I, with the writings of Sigmund Freud, Havelock Ellis and Ellen Key. There, thinkers claimed that sex was not only central to the human experience, but also that women were sexual beings with human impulses and desires, and restraining these impulses was self-destructive. By the 1920s, these ideas had permeated the mainstream.[89]

In the 1920s, the co-ed emerged, as women began attending large state colleges and universities. Women entered into the mainstream middle class experience but took on a gendered role within society. Women typically took classes such as home economics, "Husband and Wife", "Motherhood" and "The Family as an Economic Unit". In an increasingly conservative postwar era, a young woman commonly would attend college with the intention of finding a suitable husband. Fueled by ideas of sexual liberation, dating underwent major changes on college campuses. With the advent of the automobile, courtship occurred in a much more private setting. "Petting", sexual relations without intercourse, became the social norm for a portion of college students.[90]

Despite women's increased knowledge of pleasure and sex, the decade of unfettered capitalism that was the 1920s gave birth to the "feminine mystique". With this formulation, all women wanted to marry, all good women stayed at home with their children, cooking and cleaning, and the best women did the aforementioned and in addition, exercised their purchasing power freely and as frequently as possible to better their families and their homes.[91]

Liberalism in Europe

The Allied victory in the First World War seems to mark the triumph of liberalism, not just in the Allied countries themselves, but also in Germany and in the new states of Eastern Europe, as well as Japan. Authoritarian militarism as typified by Germany had been defeated and discredited. Historian Martin Blinkhorn argues that the liberal themes were ascendant in terms of "cultural pluralism, religious and ethnic toleration, national self-determination, free-market economics, representative and responsible government, free trade, unionism, and the peaceful settlement of international disputes through a new body, the League of Nations".[92] However, as early as 1917, the emerging liberal order was being challenged by the new communist movement taking inspiration from the Russian Revolution. Communist revolts were beaten back everywhere else, but they did succeed in Russia.[93]

Homosexuality

Homosexuality became much more visible and somewhat more acceptable. London, New York, Paris, Rome,[94] and Berlin were important centers of the new ethic.[95] Historian Jason Crouthamel argues that in Germany, the First World War promoted homosexual emancipation because it provided an ideal of comradeship which redefined homosexuality and masculinity. The many gay rights groups in Weimar Germany favored a militarised rhetoric with a vision of a spiritually and politically emancipated hypermasculine gay man who fought to legitimize "friendship" and secure civil rights.[96] Ramsey explores several variations. On the left, the Wissenschaftlich-humanitäres Komitee (Scientific-Humanitarian Committee; WhK) reasserted the traditional view that homosexuals were an effeminate "third sex" whose sexual ambiguity and nonconformity was biologically determined. The radical nationalist Gemeinschaft der Eigenen (Community of the Self-Owned) proudly proclaimed homosexuality as heir to the manly German and classical Greek traditions of homoerotic male bonding, which enhanced the arts and glorified relationships with young men. The politically centrist Bund für Menschenrecht (League for Human Rights) engaged in a struggle for human rights, advising gays to live in accordance with the mores of middle-class German respectability.[97]

Humor was used to assist in acceptability. One popular American song, "Masculine Women, Feminine Men",[98] was released in 1926 and recorded by numerous artists of the day; it included these lyrics:[99]

Masculine women, Feminine men

Which is the rooster, which is the hen?

It's hard to tell 'em apart today! And, say!

Sister is busy learning to shave,

Brother just loves his permanent wave,

It's hard to tell 'em apart today! Hey, hey!

Girls were girls and boys were boys when I was a tot,

Now we don't know who is who, or even what's what!

Knickers and trousers, baggy and wide,

Nobody knows who's walking inside,

Those masculine women and feminine men![100]

The relative liberalism of the decade is demonstrated by the fact that the actor William Haines, regularly named in newspapers and magazines as the #1 male box-office draw, openly lived in a gay relationship with his partner, Jimmie Shields. Other popular gay actors/actresses of the decade included Alla Nazimova and Ramón Novarro.[101] In 1927, Mae West wrote a play about homosexuality called The Drag,[102] and alluded to the work of Karl Heinrich Ulrichs. It was a box-office success. West regarded talking about sex as a basic human rights issue, and was also an early advocate of gay rights.[103]

Profound hostility did not abate in more remote areas such as western Canada.[104] With the return of a conservative mood in the 1930s, the public grew intolerant of homosexuality, and gay actors were forced to choose between retiring or agreeing to hide their sexuality even in Hollywood.[105]

Psychoanalysis

Vienna psychiatrist Sigmund Freud (1856–1939) played a major role in Psychoanalysis, which impacted avant-garde thinking, especially in the humanities and artistic fields. Historian Roy Porter wrote:

- He advanced challenging theoretical concepts such as unconscious mental states and their repression, infantile sexuality and the symbolic meaning of dreams and hysterical symptoms, and he prized the investigative techniques of free association and dream interpretation, to methods for overcoming resistance and uncovering hidden unconscious wishes.[106]

Other influential proponents of psychoanalysis included Alfred Adler (1870–1937), Karen Horney (1885–1952), and Helene Deutsch (1884–1982). Adler argued that a neurotic individual would overcompensate by manifesting aggression. Porter notes that Adler's views became part of "an American commitment to social stability based on individual adjustment and adaptation to healthy, social forms".[106]

Culture

Immigration restrictions

The United States became more anti-immigration in policy. The Immigration Act of 1924 limited immigration to a fraction proportionate to that ethnic group in the United States in 1890. The goal was to freeze the pattern of European ethnic composition, and to exclude almost all Asians. Hispanics were not restricted.[107]

Australia, New Zealand and Canada also sharply restricted or ended Asian immigration. In Canada, the Chinese Immigration Act of 1923 prevented almost all immigration from Asia. Other laws curbed immigration from Southern and Eastern Europe.[108][109][110][111]

Prohibition

During the late 19th and early 20th centuries the Progressive movement gradually caused local communities in many parts of Western Europe and North America to tighten restrictions of vice activities, particularly gambling, alcohol, and narcotics (though splinters of this same movement were also involved in racial segregation in the U.S.). This movement gained its strongest traction in the U.S. and its crowning achievement was the passage of the Eighteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution and the associated Volstead Act which made illegal the manufacture, import and sale of beer, wine and hard liquor (though drinking was technically not illegal). The laws were specifically promoted by evangelical Protestant churches and the Anti-Saloon League to reduce drunkenness, petty crime, wife abuse, corrupt saloon-politics, and (in 1918), Germanic influences. The KKK was an active supporter in rural areas, but cities generally left enforcement to a small number of federal officials. The various restrictions on alcohol and gambling were widely unpopular leading to rampant and flagrant violations of the law, and consequently to a rapid rise of organized crime around the nation (as typified by Chicago's Al Capone).[112] In Canada, prohibition ended much earlier than in the U.S., and barely took effect at all in the province of Quebec, which led to Montreal's becoming a tourist destination for legal alcohol consumption. The continuation of legal alcohol production in Canada soon led to a new industry in smuggling liquor into the U.S.[113]

Rise of the speakeasy

Speakeasies were illegal bars selling beer and liquor after paying off local police and government officials. They became popular in major cities and helped fund large-scale gangsters operations such as those of Lucky Luciano, Al Capone, Meyer Lansky, Bugs Moran, Moe Dalitz, Joseph Ardizzone, and Sam Maceo. They operated with connections to organized crime and liquor smuggling. While the U.S. Federal Government agents raided such establishments and arrested many of the small figures and smugglers, they rarely managed to get the big bosses; the business of running speakeasies was so lucrative that such establishments continued to flourish throughout the nation. In major cities, speakeasies could often be elaborate, offering food, live bands, and floor shows. Police were notoriously bribed by speakeasy operators to either leave them alone or at least give them advance notice of any planned raid.[114]

Literature

The Roaring Twenties was a period of literary creativity, and works of several notable authors appeared during the period. D. H. Lawrence's novel Lady Chatterley's Lover was a scandal at the time because of its explicit descriptions of sex. Books that take the 1920s as their subject include:

- The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald, set in 1922 in the vicinity of New York City, is often described as the symbolic meditation on the "Jazz Age" in American literature.

- All Quiet on the Western Front by Erich Maria Remarque recounts the horrors of World War I and also the deep detachment from German civilian life felt by many men returning from the front.

- This Side of Paradise by F. Scott Fitzgerald, primarily set up in post-World War I Princeton University, portrays the lives and morality of youth.

- The Sun Also Rises by Ernest Hemingway is about a group of expatriate Americans in Europe during the 1920s.

The 1920s also saw the widespread popularity of the pulp magazine. Printed on cheap pulp paper, these magazines provided affordable entertainment to the masses and quickly became one of the most popular forms of media during the decade. Many prominent writers of the 20th century would get their start writing for pulps, including F. Scott Fitzgerald, Dashiell Hammett and H. P. Lovecraft. Pulp fiction magazines would last in popularity until the 1950s.[115]

Solo flight across the Atlantic

Charles Lindbergh gained sudden great international fame as the first pilot to fly solo and non-stop across the Atlantic Ocean, flying from Roosevelt Airfield (Nassau County, Long Island), New York to Paris on May 20–21, 1927. He had a single-engine airplane, the "Spirit of St. Louis", which had been designed by Donald A. Hall and custom built by Ryan Airlines of San Diego, California. His flight took 33.5 hours. The president of France bestowed on him the French Legion of Honor and, on his arrival back in the United States, a fleet of warships and aircraft escorted him to Washington, D.C., where President Calvin Coolidge awarded him the Distinguished Flying Cross.

Sports

The Roaring Twenties was the breakout decade for sports across the modern world. Citizens from all parts of the country flocked to see the top athletes of the day compete in arenas and stadia. Their exploits were loudly and highly praised in the new "gee whiz" style of sports journalism that was emerging; champions of this style of writing included the legendary writers Grantland Rice and Damon Runyon in the U.S. Sports literature presented a new form of heroism departing from the traditional models of masculinity.[116]

High school and junior high school students were offered to play sports that they hadn't been able to play in the past. Several sports, such as golf, that had previously been unavailable to the middle-class finally became available.

In 1929, driver Henry Segrave reached a record land speed of 231.44 mph in his car, the Golden Arrow.[citation needed]

Olympics

Following the 1922 Latin American Games in Rio de Janeiro, IOC officials toured the region, helping countries establish national Olympic committees and prepare for future competition. In some countries, such as Brazil, sporting and political rivalries hindered progress as opposing factions battled for control of the international sport. The 1924 Olympic Games in Paris and the 1928 games in Amsterdam saw greatly increased participation from Latin American athletes.[117]

Sports journalism, modernity, and nationalism excited Egypt. Egyptians of all classes were captivated by news of the Egyptian national soccer team's performance in international competitions. Success or failure in the Olympics of 1924 and 1928 was more than a betting opportunity but became an index of Egyptian independence and a desire to be seen as modern by Europe. Egyptians also saw these competitions as a way to distinguish themselves from the traditionalism of the rest of Africa.[118]

Balkans

The Greek government of Eleftherios Venizelos initiated a number of programs involving physical education in the public schools and raised the profile of sports competition. Other Balkan nations also became more involved in sports and participated in several precursors of the Balkan Games, competing sometimes with Western European teams. The Balkan Games, first held in Athens in 1929 as an experiment, proved a sporting and a diplomatic success. From the beginning, the games, held in Greece through 1933, sought to improve relations among Greece, Turkey, Bulgaria, Yugoslavia, Romania, and Albania. As a political and diplomatic event, the games worked in conjunction with an annual Balkan Conference, which resolved issues between these often-feuding nations. The results were quite successful; officials from all countries routinely praised the games' athletes and organizers. During a period of persistent and systematic efforts to create rapprochement and unity in the region, this series of athletic meetings played a key role.[119]

United States

The most popular American athlete of the 1920s was baseball player Babe Ruth. His characteristic home-run hitting heralded a new epoch in the history of the sport (the "Live-ball era"), and his high style of living fascinated the nation and made him one of the highest-profile figures of the decade. Fans were enthralled in 1927 when Ruth hit 60 home runs, setting a new single-season home run record that was not broken until 1961. Together with another up-and-coming star named Lou Gehrig, Ruth laid the foundation of future New York Yankees dynasties.

A former bar room brawler named Jack Dempsey, also known as The Manassa Mauler, won the world heavyweight boxing title and became the most celebrated pugilist of his time. Enrique Chaffardet the Venezuelan Featherweight World Champion was the most sought-after boxer in 1920s Brooklyn, New York City. College football captivated fans, with notables such as Red Grange, running back of the University of Illinois, and Knute Rockne who coached Notre Dame's football program to great success on the field and nationwide notoriety. Grange also played a role in the development of professional football in the mid-1920s by signing on with the NFL's Chicago Bears. Bill Tilden thoroughly dominated his competition in tennis, cementing his reputation as one of the greatest tennis players of all time. And Bobby Jones popularized golf with his spectacular successes on the links. Ruth, Dempsey, Grange, Tilden, and Jones are collectively referred to as the "Big Five" sporting icons of the Roaring Twenties.

Organized crime

During the 19th century vices such as gambling, alcohol, and narcotics had been popular throughout the United States in spite of not always being technically legal. Enforcement against these vices had always been spotty. Indeed, most major cities established red-light districts to regulate gambling and prostitution despite the fact that these vices were typically illegal. However, with the rise of the Progressive Movement in the early 20th century, laws gradually became tighter with most gambling, alcohol, and narcotics outlawed by the 1920s. Because of widespread public opposition to these prohibitions, especially alcohol, a great economic opportunity was created for criminal enterprises. Organized crime blossomed during this era, particularly the American Mafia.[120] So lucrative were these vices that some entire cities in the U.S. became illegal gaming centers with vice actually supported by the local governments. Notable examples include Miami, Florida, and Galveston, Texas.

Many of these criminal enterprises would long outlast the roaring twenties and ultimately were instrumental in establishing Las Vegas as a gambling center.

Culture of Weimar Germany

Weimar culture was the flourishing of the arts and sciences in Germany during the Weimar Republic, from 1918 until Adolf Hitler's rise to power in 1933.[121] 1920s Berlin was at the hectic center of the Weimar culture. Although not part of Germany, German-speaking Austria, and particularly Vienna, is often included as part of Weimar culture.[122] Bauhaus was a German art school operational from 1919 to 1933 that combined crafts and the fine arts. Its goal of unifying art, craft, and technology became influential worldwide, especially in architecture.[123]

Germany, and Berlin in particular, was fertile ground for intellectuals, artists, and innovators from many fields. The social environment was chaotic, and politics were passionate. German university faculties became universally open to Jewish scholars in 1918. Leading Jewish intellectuals on university faculties included physicist Albert Einstein; sociologists Karl Mannheim, Erich Fromm, Theodor Adorno, Max Horkheimer, and Herbert Marcuse; philosophers Ernst Cassirer and Edmund Husserl; sexologist Magnus Hirschfeld; political theorists Arthur Rosenberg and Gustav Meyer; and many others. Nine German citizens were awarded Nobel prizes during the Weimar Republic, five of whom were Jewish scientists, including two in medicine.[124]

Sport took on a new importance as the human body became a focus that pointed away from the heated rhetoric of standard politics. The new emphasis reflected the search for freedom by young Germans alienated from rationalized work routines.[125]

American politics

The 1920s saw dramatic innovations in American political campaign techniques, based especially on new advertising methods that had worked so well selling war bonds during the First World War. Governor James M. Cox of Ohio, the Democratic Party candidate, made a whirlwind campaign that took him to rallies, train station speeches, and formal addresses, reaching audiences totaling perhaps 2,000,000 people. It resembled the William Jennings Bryan campaign of 1896. By contrast, the Republican Party candidate Senator Warren G. Harding of Ohio relied upon a "Front Porch Campaign". It brought 600,000 voters to Marion, Ohio, where Harding spoke from his home. Republican campaign manager Will Hays spent some $8,100,000; nearly four times the money Cox's campaign spent. Hays used national advertising in a major way (with advice from adman Albert Lasker). The theme was Harding's own slogan "America First". Thus the Republican advertisement in Collier's Magazine for October 30, 1920, demanded, "Let's be done with wiggle and wobble." The image presented in the ads was nationalistic, using catchphrases like "absolute control of the United States by the United States," "Independence means independence, now as in 1776," "This country will remain American. Its next President will remain in our own country," and "We decided long ago that we objected to a foreign government of our people."[126]

1920 was the first presidential campaign to be heavily covered by the press and to receive widespread newsreel coverage, and it was also the first modern campaign to use the power of Hollywood and Broadway stars who traveled to Marion for photo opportunities with Harding and his wife. Al Jolson, Lillian Russell, Douglas Fairbanks and Mary Pickford, were among the celebrities to make the pilgrimage. Business icons Thomas Edison, Henry Ford and Harvey Firestone also lent their cachet to the Front Porch Campaign.[127] On election night, November 2, 1920, commercial radio broadcast coverage of election returns for the first time. Announcers at KDKA-AM in Pittsburgh, PA read telegraph ticker results over the air as they came in. This single station could be heard over most of the Eastern United States by the small percentage of the population that had radio receivers.

Calvin Coolidge was inaugurated as president after the sudden death of President Warren G. Harding in 1923; he was re-elected in 1924 in a landslide against a divided opposition. Coolidge made use of the new medium of radio and made radio history several times while president: his inauguration was the first presidential inauguration broadcast on radio; on 12 February 1924, he became the first American president to deliver a political speech on radio. Herbert Hoover was elected president in 1928.

Decline of labor unions

Unions grew very rapidly during the war but after a series of failed major strikes in steel, meatpacking and other industries, a long decade of decline weakened most unions and membership fell even as employment grew rapidly. Radical unionism virtually collapsed, in large part because of Federal repression during World War I by means of the Espionage Act of 1917 and the Sedition Act of 1918.

The 1920s marked a period of sharp decline for the labor movement. Union membership and activities fell sharply in the face of economic prosperity, a lack of leadership within the movement, and anti-union sentiments from both employers and the government. The unions were much less able to organize strikes. In 1919, more than 4,000,000 workers (or 21% of the labor force) participated in about 3,600 strikes. In contrast, 1929 witnessed about 289,000 workers (or 1.2% of the workforce) stage only 900 strikes. Unemployment rarely dipped below 5% in the 1920s and few workers faced real wage losses.[128]

Progressivism in 1920s

The Progressive Era in the United States was a period of social activism and political reform that flourished from the 1890s to the 1920s. The politics of the 1920s was unfriendly toward the labor unions and liberal crusaders against business, so many if not all historians who emphasize those themes write off the decade. Urban cosmopolitan scholars recoiled at the moralism of prohibition and the intolerance of the nativists of the Ku Klux Klan (KKK), and denounced the era. Historian Richard Hofstadter, for example, in 1955 wrote that prohibition, "was a pseudo-reform, a pinched, parochial substitute for reform" that "was carried about America by the rural-evangelical virus".[129] However, as Arthur S. Link emphasized, the progressives did not simply roll over and play dead.[130] Link's argument for continuity through the 1920s stimulated a historiography that found Progressivism to be a potent force. Palmer, pointing to people like George Norris, say, "It is worth noting that progressivism, whilst temporarily losing the political initiative, remained popular in many western states and made its presence felt in Washington during both the Harding and Coolidge presidencies."[131] Gerster and Cords argue that "Since progressivism was a 'spirit' or an 'enthusiasm' rather than an easily definable force with common goals, it seems more accurate to argue that it produced a climate for reform which lasted well into the 1920s, if not beyond."[132] Even the Klan has been seen in a new light as numerous social historians reported that Klansmen were "ordinary white Protestants" primarily interested in purification of the system, which had long been a core progressive goal.[133]

Business progressivism

What historians have identified as "business progressivism", with its emphasis on efficiency and typified by Henry Ford and Herbert Hoover[134] reached an apogee in the 1920s. Reynold M. Wik, for example, argues that Ford's "views on technology and the mechanization of rural America were generally enlightened, progressive, and often far ahead of his times."[135]

Tindall stresses the continuing importance of the Progressive movement in the South in the 1920s involving increased democracy, efficient government, corporate regulation, social justice, and governmental public service.[136][137] William Link finds political progressivism dominant in most of the South in the 1920s.[138] Likewise it was influential in Midwest.[139]

Historians of women and of youth emphasize the strength of the progressive impulse in the 1920s.[140] Women consolidated their gains after the success of the suffrage movement, and moved into causes such as world peace,[141] good government, maternal care (the Sheppard–Towner Act of 1921),[142] and local support for education and public health.[143] The work was not nearly as dramatic as the suffrage crusade, but women voted[144] and operated quietly and effectively. Paul Fass, speaking of youth, wrote "Progressivism as an angle of vision, as an optimistic approach to social problems, was very much alive."[145] The international influences which had sparked a great many reform ideas likewise continued into the 1920s, as American ideas of modernity began to influence Europe.[146]

There is general agreement that the Progressive era was over by 1932, especially since a majority of the remaining progressives opposed the New Deal.[147]

Canadian politics

Canadian politics were dominated federally by the Liberal Party of Canada under William Lyon Mackenzie King. The federal government spent most of the decade disengaged from the economy and focused on paying off the large debts amassed during the war and during the era of railway over expansion. After the booming wheat economy of the early part of the century, the prairie provinces were troubled by low wheat prices. This played an important role in the development of Canada's first highly successful third political party, the Progressive Party of Canada that won the second most seats in the 1921 national election. As well with the creation of the Balfour Declaration of 1926, Canada achieved with other British former colonies autonomy, forming the British Commonwealth.

End of the Roaring Twenties

Black Tuesday

The Dow Jones Industrial Stock Index had continued its upward move for weeks, and coupled with heightened speculative activities, it gave an illusion that the bull market of 1928 to 1929 would last forever. On October 29, 1929, also known as Black Tuesday, stock prices on Wall Street collapsed. The events in the United States added to a worldwide depression, later called the Great Depression, that put millions of people out of work around the world throughout the 1930s.

Repeal of Prohibition

The 21st Amendment, which repealed the 18th Amendment, was proposed on February 20, 1933. The choice to legalize alcohol was left up to the states, and many states quickly took this opportunity to allow alcohol. Prohibition was officially ended with the ratification of the Amendment on December 5, 1933.

انظر أيضاً

- Depression of 1920–21

- France in the 1920s

- Golden Twenties, the equivalent period in Germany

- Interwar Britain

- Interwar period, worldwide

- Jazz Age

- Los Angeles in the 1920s

الهامش

- ^ Anton Gill, A Dance Between Flames: Berlin Between the Wars (1994).

- ^ Marc Moscato, Brains, Brilliancy, Bohemia: Art & Politics in Jazz-Age Chicago (2009)

- ^ Hall, Lesley A. (1996). "Impotent ghosts from no man's land, flappers' boyfriends, or crypto‐patriarchs? Men, sex and social change in 1920s Britain". Social History. 21 (1): 54–70. doi:10.1080/03071029608567956.

- ^ David Robinson, Hollywood in the Twenties (1968)

- ^ David Wallace, Capital of the World: A Portrait of New York City in the Roaring Twenties (2011)

- ^ Jody Blake, Le Tumulte Noir: modernist art and popular entertainment in jazz-age Paris, 1900–1930 (1999)

- ^ Jack Lindsay, The roaring twenties: literary life in Sydney, New South Wales in the years 1921-6 (1960)

- ^ Andrew Lamb (2000). 150 Years of Popular Musical Theatre. Yale University Press. p. 195. ISBN 978-0-300-07538-0.

- ^ Pamela Horn, Flappers: The Real Lives of British Women in the Era of the Great Gatsby (2013)

- ^ Angela J. Latham, Posing a Threat: Flappers, Chorus Girls, and Other Brazen Performers of the American 1920s (2000)

- ^ Madeleine Ginsburg, Paris fashions: the art deco style of the 1920s (1989)

- ^ Bärbel Schrader, and Jürgen Schebera. The" golden" twenties: art and literature in the Weimar Republic (1988)

- ^ Paul N. Hehn (2005). A Low Dishonest Decade: The Great Powers, Eastern Europe, and the Economic Origins of World War II, 1930–1941. Continuum. p. 12. ISBN 978-0-8264-1761-9.

- ^ Based on data in Susan Carter, ed. Historical Statistics of the US: Millennial Edition (2006) series Ca9

- ^ "Roaring Twenties". U-S-History.com. Online Highways. Retrieved 2019-11-14.

- ^ أ ب George H. Soule, Prosperity Decade: From War to Depression: 1917–1929 (1947)

- ^ "Model T Facts" (Press release). US: Ford. Retrieved 2013-04-23.

- ^ John Steele Gordon (2007-03-01). "10 Moments That Made American Business". American Heritage. Retrieved 2012-12-24.

- ^ "Michigan History". Detroit News. Archived from the original on July 10, 2012.

- ^ Sorensen 1956, pp. 217–219.

- ^ Hounshell 1984, pp. 263–264

- ^ Sloan 1964, pp. 162–163

- ^ https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/ohim/summary95/mv200.pdf

- ^ Foreman-Peck, James (1982). "The American Challenge of the Twenties: Multinationals and the European Motor Industry". The Journal of Economic History. 42 (4): 865–881. doi:10.1017/S0022050700028370.

- ^ Kenrick, John. "History of Musical Film, 1927–30: Part II". Musicals101.com, 2004, accessed May 17, 2010

- ^ Stephens, E. J.; Wanamaker, Marc (2010). Early Warner Bros. Studios. Arcadia Publishing. p. 25. ISBN 978-0-738-58091-3.

- ^ Allen, Bob (Autumn 1997). "Why The Jazz Singer?". AMPS Newsletter. Association of Motion Picture Sound. Archived from the original on 1999-10-22. Retrieved December 12, 2009.

- ^ Geduld (1975), p. 166.

- ^ Crafton (1997), p. 148.

- ^ Crafton (1997), p. 390.

- ^ Steamboat Willie (1929) Archived 2011-11-21 at the Wayback Machine at Screen Savour

- ^ Robertson (2001), p. 63.

- ^ Robertson (2001), p. 173.

- ^ Jackson 2012, pp. 512–516.

- ^ Spencer Dunmore, Undaunted: Long-Distance Flyers in the Golden Age of Aviation (2004)

- ^ "Patent US1925554 – Television apparatus and the like".

- ^ R. F. Tiltman, How "Stereoscopic" Television is Shown, Radio News, November 1928

- ^ Interview with Paul Lyons Archived 2009-02-02 at the Wayback Machine, Historian and Control and Information Officer at Glasgow Central Station

- ^ "Historic Figures: John Logie Baird (1888–1946)". BBC. Retrieved 28 April 2015.

- ^ Wainwright M, Swan HT; Swan (January 1986). "C.G. Paine and the earliest surviving clinical records of penicillin therapy". Medical History. 30 (1): 42–56. doi:10.1017/S0025727300045026. PMC 1139580. PMID 3511336.

- ^ Howie, J (1986). "Penicillin: 1929–40". British Medical Journal (Clinical Research Ed.). 293 (6540): 158–159. doi:10.1136/bmj.293.6540.158. PMC 1340901. PMID 3089435.

- ^ Wainwright, M (1987). "The history of the therapeutic use of crude penicillin". Medical History. 31 (1): 41–50. doi:10.1017/s0025727300046305. PMC 1139683. PMID 3543562.

- ^ Flink, James J. (1972). "Three Stages of American Automobile Consciousness". American Quarterly. 24 (4): 451–473. doi:10.2307/2711684. JSTOR 2711684.

- ^ John A. Jakle, and Keith A. Sculle, Fast food: Roadside restaurants in the automobile age (2002).

- ^ Christopher W. Wells, Car Country: Automobiles, Roads and the Shaping of the Modern American Landscape, 1890–1929 (2004).

- ^ David E. Nye, Electrifying America: Social meanings of a new technology, 1880–1940 (1992)

- ^ Dan Bryan. "The Great (Farm) Depression of the 1920s". American History USA. Retrieved November 10, 2013.

- ^ The vote came years later in France, Italy, Quebec, Spain and Switzerland.

- ^ June Hannam, Mitzi Auchterlonie, and Katherine Holden, eds. International encyclopedia of women's suffrage (Abc-Clio Inc, 2000).

- ^ Rosemary Skinner Keller; Rosemary Radford Ruether; Marie Cantlon (2006). Encyclopedia of Women and Religion in North America. Indiana UP. p. 1033. ISBN 0-253-34688-6.

- ^ Josephine Donovan (2012). Feminist Theory, Fourth Edition: The Intellectual Traditions. A&C Black. p. 60. ISBN 978-1-4411-6830-6.

- ^ Julie V. Gottlieb (2016). 'Guilty Women', Foreign Policy, and Appeasement in Inter-War Britain. Springer. p. 4. ISBN 978-1-137-31660-8.

- ^ D. J. Taylor (2010). Bright Young People: The Lost Generation of London's Jazz Age. Macmillan. p. 303. ISBN 978-1-4299-5895-0.

- ^ Geduld, Harry M. (1975). The Birth of the Talkies: From Edison to Jolson. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-10743-1

- ^ emmickey_UNCG http://disney.go.com/vault/archives/characterstandard/mickey/mickey.html

- ^ emmickey_UNCG http://disney.go.com/vault/archives/characters/oswald/oswald.html

- ^ J. G. Ellrod, The Stars of Hollywood Remembered: Career Biographies of 81 Actors and Actesses of the Golden Era, 1920s–1950s (1997).

- ^ Arnold Shaw, The Jazz Age: Popular Music in the 1920s (Oxford UP, 1989).

- ^ Kathy J. Ogren, The Jazz Revolution: Twenties America and the Meaning of Jazz (1989) p. 11.

- ^ DeVeaux, Scott (1991). "Constructing the Jazz Tradition: Jazz Historiography" (PDF). Black American Literature Forum. 25 (3): 525–60. doi:10.2307/3041812. JSTOR 3041812.

- ^ Ted Gioia, The History of Jazz (Oxford UP, 2011).

- ^ Ralph G. Giordano, Satan in the dance hall: Rev. John Roach Straton, social dancing, and morality in 1920s New York City (2008).

- ^ Robinson, Danielle (2006). "'Oh, You Black Bottom!' Appropriation, Authenticity, and Opportunity in the Jazz Dance Teaching of 1920s New York". Dance Research Journal. 38 (1–2): 19–42. doi:10.1017/S0149767700007312.

- ^ Spring, Howard (1997). "Swing and the Lindy Hop: Dance, Venue, Media, and Tradition". American Music. 15 (2): 183–207. doi:10.2307/3052731. JSTOR 3052731.

- ^ Frances Rust (1969). Dance in Society: An Analysis of the Relationship Between the Social Dance and Society in England from the Middle Ages to the Present Day. Routledge. p. 189. ISBN 978-1-134-55407-2.

- ^ Jim Cox, Music radio: the great performers and programs of the 1920s through early 1960s (McFarland, 2005).

- ^ Roberts, Mary Louise (1993). "Samson and Delilah Revisited: The Politics of Women's Fashion in 1920s France". The American Historical Review. 98 (3): 657–684. doi:10.1086/ahr/98.3.657.

- ^ Bliss, Simon (2016). "'L'intelligence de la parure': Notes on Jewelry Wearing in the 1920s". Fashion Theory. 20 (1): 5–26. doi:10.1080/1362704X.2015.1077652.

- ^ Zdatny, Steven (1997). "The Boyish Look and the Liberated Woman: The Politics and Aesthetics of Women's Hairstyles". Fashion Theory. 1 (4): 367–397. doi:10.2752/136270497779613639.

- ^ Angel Kwolek-Folland, Engendering Business: Men and Women in the Corporate Office, 1870-1930 (Johns Hopkins UP, 1994).

- ^ Carolyn Kitch, The Girl on the Magazine Cover (University of North Carolina Press, 2001). pp. 122–23.

- ^ Sylvester, Nina (2007). "Before Cosmopolitan: The Girl in German women's magazines in the 1920s". Journalism Studies. 8 (4): 550–554. doi:10.1080/14616700701411953.

- ^ Lucy Moore, Anything Goes: A Biography of the Roaring Twenties (Atlantic Books, 2015).

- ^ Bingham, Jane (2012). Popular Culture: 1920–1938. Chicago Illinois: Heinemann Library.

- ^ Paula S. Fass, The Damned and the Beautiful: American Youth in the 1920s (Oxford UP, 1977)

- ^ Litchfield Historical Society (2015). The House of Worth: Fashion Sketches, 1916–1918. Courier Dover. p. 28. ISBN 978-0-486-79924-7.

- ^ Lurie, Alison (1981). The Language of Clothes. New York: New York: Random House.

- ^ Brand, Jan (2007). Fashion & Accessories. Arnhem :Terra.

- ^ Bingham, Adrian (2004). "'An Era of Domesticity'? Histories of Women and Gender in Interwar Britain". Cultural and Social History. 1 (2): 225–233. doi:10.1191/1478003804cs0014ra.

- ^ Alison Light, Forever England: Femininity, Literature and Conservatism between the Wars (1991) p. 9.

- ^ Brown, Dorothy M. Setting a Course: American Women in the 1920s (Twayne Publishers, 1987) p. 33.

- ^ Nancy Woloch, Women and the American Experience: A Concise History (2002). p. 256.

- ^ Linda Eisenmann, Historical Dictionary of Women's Education in the United States (1998) p. 440.

- ^ Rabinovitch-Fox, Einav (2016). "Baby, You Can Drive My Car: Advertising Women's Freedom in 1920s America". American Journalism. 33 (4): 372–400. doi:10.1080/08821127.2016.1241641.

- ^ Alice Kessler-Harris, Out to Work: A History of Wage-Earning Women in the United States (Oxford University Press, 2003) p. 219.

- ^ Kessler-Harris, Alice. Out to Work: A History of Wage-Earning Women in the United States p. 237.

- ^ Kessler-Harris, Out to Work: A History of Wage-Earning Women in the United States pp 237, 288.

- ^ Nancy Woloch, Women and the American Experience: A Concise History (McGraw–Hill, 2002) p. 246.

- ^ Woloch, Women and the American Experience: A Concise History p. 274.

- ^ Woloch, Women and the American Experience: A Concise History, pp. 28–3.

- ^ Ruth Schwartz Cowan, Two Washes in the Morning and a Bridge Party at Night: The American Housewife between the Wars (1976) p. 184.

- ^ Nicholas Atkin; Michael Biddiss (2008). Themes in Modern European History, 1890–1945. Routledge. pp. 243–44. ISBN 978-1-134-22257-5.

- ^ Gregory M. Luebbert, Liberalism, fascism, or social democracy: Social classes and the political origins of regimes in interwar Europe (Oxford UP, 1991).

- ^ Julian Jackson (2009). Living in Arcadia: Homosexuality, Politics, and Morality in France from the Liberation to AIDS. University of Chicago Press. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-226-38928-8.

- ^ Florence Tamagne (2006). A History of Homosexuality in Europe: Berlin, London, Paris, 1919–1939. Algora Publishing. p. 309. ISBN 978-0-87586-357-3.

- ^ Crouthamel, Jason (2011). "'Comradeship' and 'Friendship': Masculinity and Militarisation in Germany's Homosexual Emancipation Movement after the First World War: Masculinity and Militarisation in Germany's Homosexual Emancipation Movement". Gender & History. 23 (1): 111–129. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0424.2010.01626.x.

- ^ Ramsey, Glenn (2007). "The Rites of Artgenossen: Contesting Homosexual Political Culture in Weimar Germany". Journal of the History of Sexuality. 17 (1): 85–109. doi:10.1353/sex.2008.0009.

- ^ The song was written by Edgar Leslie (words) and James V. Monaco (music) and featured in Hugh J. Ward's Musical Comedy "Lady Be Good."

- ^ Artists who recorded this song include: 1. Frank Harris (Irving Kaufman), (Columbia 569D,1/29/26) 2. Bill Meyerl & Gwen Farrar (the UK, 1926) 3. Joy Boys (the UK, 1926) 4. Harry Reser's Six Jumping Jacks (the UK, 2/13/26) 5. Hotel Savoy Opheans (HMV 5027, UK, 1927, aka Savoy Havana Band) 6. Merrit Brunies & His Friar's Inn Orchestra on Okeh 40593, 3/2/26

- ^ A full reproduction of the original sheet music with the complete lyrics (including the amusing cover sheet) can be found at: http://nla.gov.au/nla.mus-an6301650

- ^ Mann, William J., Wisecracker: the life and times of William Haines, Hollywood's first openly gay star (Viking, 1998) pp 2–6, 12–13, 80–83.

- ^ See Three Plays by Mae West: Sex, The Drag and Pleasure Man

- ^ Jill Watts (2003). Mae West: An Icon in Black and White. Oxford University Press. p. 300. ISBN 978-0-19-534767-8.

- ^ TChapman, Terry L. (1983). "'An Oscar Wilde Type': 'The Abominable Crime of Buggery' in Western Canada, 1890–1920". Criminal Justice History. 4: 97–118.

- ^ Hurewitz, Daniel (2006). "Goody-Goodies, Sissies, and Long-Hairs: The Dangerous Figures in 1930s Los Angeles Political Culture". Journal of Urban History. 33 (1): 26–50. doi:10.1177/0096144206291106.

- ^ أ ب Roy Porter (1999). The Greatest Benefit to Mankind: A Medical History of Humanity. W. W. Norton. pp. 516–517. ISBN 978-0-393-24244-7.

- ^ John Higham, Strangers in the Land: Patterns of American Nativism, 1860–1925 (1955) pp 312–30

- ^ Bashford, Alison (2014). "Immigration restriction: rethinking period and place from settler colonies to postcolonial nations". Journal of Global History. 9 (1): 26–48. doi:10.1017/S174002281300048X.

- ^ W. Peter Ward, White Canada forever: popular attitudes and public policy towards Orientals in British Columbia (McGill-Queens UP, 1990).

- ^ O'Connor, P. (1968). "Keeping New Zealand white, 1908–1920". New Zealand Journal of History. 2 (1): 41–65.

- ^ Sean Brawley, The white peril: foreign relations and Asian immigration to Australia and North America, 1919–1978 (U of New South Wales Press, 1995).

- ^ Daniel Okrent (2010). Last Call: The Rise and Fall of Prohibition. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 9781439171691.

- ^ Gerald Hallowell, "Prohibition in Canada". The Canadian Encyclopedia (1988)

- ^ Michael A. Lerner, Dry Manhattan: Prohibition in New York City (2007).

- ^ https://www.nrm.org/2013/04/pulp-magazines-and-their-influence-on-entertainment-today-by-mai-ly-degnan/

- ^ Imhoof, D. (2009). "The Game of Political Change: Sports in Göttingen during the Weimar and Nazi Eras". German History. 27 (3): 374–394. doi:10.1093/gerhis/ghp032.

- ^ Torres, Cesar R. (2006). "The Latin American 'Olympic explosion' of the 1920s: Causes and consequences". The International Journal of the History of Sport. 23 (7): 1088–1111. doi:10.1080/09523360600832320.

- ^ Lopez, Shaun (2009). "Football as National Allegory: Al-Ahram and the Olympics in 1920s Egypt". History Compass. 7 (1): 282–305. doi:10.1111/j.1478-0542.2008.00576.x.

- ^ Kissoudi, P. (2008). "Sport, Politics and International Relations in the Balkans: the Balkan Games from 1929 to 1932". The International Journal of the History of Sport. 25 (13): 1771–1813. doi:10.1080/09523360802367349.

- ^ "Mafia in the United States". History.com.

- ^ Peter Gay, Weimar Culture: The Outsider as Insider (2001)

- ^ Lee Congdon, Exile and Social Thought: Hungarian Intellectuals in Germany and Austria, 1919–1933 (1991).

- ^ Kathleen James-Chakraborty, Bauhaus Culture: From Weimar to the Cold War (2006).

- ^ Niewyk, Donald L. (2001). The Jews in Weimar Germany. Transaction Publishers. pp. 39–40. ISBN 978-0-7658-0692-5.

- ^ Rippey, Theodore F. (2005). "Athletics, Aesthetics, and Politics in the Weimar Press". German Studies Review. 28 (1): 85–106. JSTOR 30038070.

- ^ Andrew Sinclair, The Available Man: The Life behind the Masks of Warren Gamaliel Harding (1965) p. 162

- ^ John Morello, Selling the President, 1920: Albert D. Lasker, Advertising, and the Election of Warren G. Harding (2001).

- ^ Robert Zieger, American Workers, American Unions (1994) pp. 5–6

- ^ Richard Hofstadter, The Age of Reform (1955) p. 287

- ^ Link, Arthur S. (1959). "What Happened to the Progressive Movement in the 1920's?". The American Historical Review. 64 (4): 833–851. doi:10.2307/1905118. JSTOR 1905118.

- ^ Niall A. Palmer, The twenties in America: politics and history (2006) p 176

- ^ Patrick Gerster and Nicholas Cords, Myth in American history (1977) p 203

- ^ Coben, S. (1994). "Ordinary White Protestants: The KKK of the 1920s". Journal of Social History. 28 (1): 155–165. doi:10.1353/jsh/28.1.155.

- ^ Morris, Stuart (1970). "The Wisconsin Idea and Business Progressivism". Journal of American Studies. 4 (1): 39–60. doi:10.1017/S0021875800000050.

- ^ Wik, Reynold Millard (1962). "Henry Ford's Science and Technology for Rural America". Technology and Culture. 3 (3): 247–258. doi:10.2307/3100818.

- ^ Tindall, George B. (1963). "Business Progressivism: Southern Politics in the Twenties". South Atlantic Quarterly. 62: 92–106.

- ^ George B. Tindall, The Emergence of the New South, 1913–1945 (1970)

- ^ William A. Link, The Paradox of Southern Progressivism, 1880–1930 (1997) p 294

- ^ Judith Sealander, Grand Plans: Business Progressivism and Social Change in Ohio's Miami Valley, 1890–1929 (1991)

- ^ Maureen A. Flanagan, America Reformed: Progressives and Progressivisms, 1890s–1920s (2006)

- ^ Zeiger, Susan (1990). "Finding a Cure for War: Women's Politics and the Peace Movement in the 1920s". Journal of Social History. 24 (1): 69–86. doi:10.1353/jsh/24.1.69. JSTOR 3787631.

- ^ Lemons, J. Stanley (1969). "The Sheppard-Towner Act: Progressivism in the 1920s". The Journal of American History. 55 (4): 776–786. doi:10.2307/1900152. JSTOR 1900152.

- ^ Morris-Crowther, Jayne (2004). "Municipal Housekeeping: The Political Activities of the Detroit Federation of Women's Clubs in the 1920s". Michigan Historical Review. 30 (1): 31–57. doi:10.2307/20174059.

- ^ Kristi Andersen, After suffrage: women in partisan and electoral politics before the New Deal (1996)

- ^ Paula S. Fass, The damned and the beautiful: American youth in the 1920s (1977) p 30

- ^ Daniel T. Rodgers, Atlantic Crossings: Social Politics in a Progressive Age (2000) ch 9

- ^ Otis L. Graham, An Encore for Reform: The Old Progressives and the New Deal (1968)

للاستزادة

- Blom, Philipp. Fracture: Life and Culture in the West, 1918–1938 (Basic Books, 2015).