بشراني (جنس)

| بشراني | |

|---|---|

| |

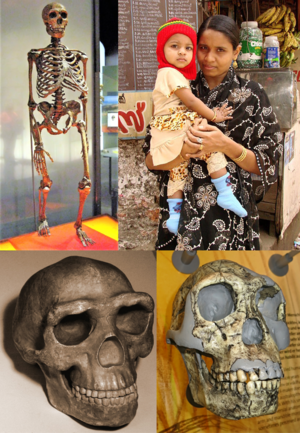

| أبرز أعضاء الجنس البشراني. تجاه عقارب الساعة من أعلى اليسار: اعادة بناء تقريبي لجنس النياندرتال (Homo neanderthalensis) الهيكل العظمي لأم وطفلها من جنس البشر المعاصرون (Homo sapiens) الهند، جمجمة معاد بنائها من جنس الإنسان الماهر، ونسخة طبق الأصل من جمجمة رجل بكين (تحت نوع الإنسان المنتصب). | |

| التصنيف العلمي | |

| أصنوفة غير معروفة (أصلحها): | الحياة |

| مملكة: | الحيوانية |

| Phylum: | حبليات |

| Class: | الثدييات |

| تحت رتبة: | جافة الأنف |

| فوق رتبة: | القرديات |

| الفرع الحيوي: | أشباه البشر |

| الجنس: | هومو لينايوس، 1758 |

| Type species | |

| الإنسان العاقل لينايوس، 1758

| |

| تحت الأنواع | |

لأنواع وتحت أنواع أخرى مقترحة، انظر أدناه. | |

| Synonyms | |

|

المرادفات

| |

البشراني أو الهومو (إنگليزية: Homo؛ من Latin homō، وتعني "human")، هو جنس نشأ في جنس أوسترالوپثيكس ويضم النوع المتواجد حالياً الإنسان العاقل (الإنسان الحديث)، إلى جانب العديد من الأنواع المنقرضة المصنفة على أنها أسلاف أو مرتبطة ارتباطًا وثيقًا بالإنسان الحديث، بما في ذلك "الإنسان المنتصب" و"النياندرتال". أقدم عضو في جنس "الهومو" هو "الإنسان الماهر" بسجلات تزيد قليلاً عن مليوني سنة مضت.[أ] من المحتمل أن يكون "الهومو"، جنبًا إلى جنب مع "پارانثروپوس"، يشكل أختًا "للأسترالوپيثكس الأفريقي"، والتي كانت نفسها قد انفصلت سابقًا عن سلالة الشمبانزي.[ب][4][5]

ظهر الإنسان المنتصب منذ حوالي 2 مليون سنة مضت، في عدد من الهجرات المبكرة، منتشراً في أرجاء أفريقيا (حيث يسمى "الإنسان العامل") وأوراسيا. من المحتمل أن النوع البشري الأول عاش في مجتمع صياد وجامع ثمار وكان قادرًا على التحكم في النار. استمرت الأنواع المتكيفة والناجحة، من الإنسان المنتصب لأكثر من مليون سنة وتباعدت تدريجيًا إلى أنواع جديدة منذ حوالي 500.000 سنة.[ت][6]

ظهر الإنسان الحديث تشريحياً ("الإنسان العاقل") منذ ما يقرب من 300.000 إلى 200.000 سنة مضت،[7] في أفريقيا، وظهر إنسان نياندرتال في نفس الوقت تقريبا في أوروپا وغرب آسيا. انتشر الإنسان العاقل من أفريقيا في عدة موجات، منذ حوالي 250.000 سنة مضت، وبالتأكيد قبل 130.000 سنة مضت، بدأ ما يسمى الانتشار الجنوبي منذ حوالي 70.000-50.000 سنة مضت[8][9][10] مما أدى إلى الاستيطان الدائم في أوراسيا وأوقيانوسيا منذ 50.000 سنة مضت. في كلاً من أفريقيا وأوراسيا، التقى الإنسان العاقل وتهاجن مع الأنواع البشرية العتيقة.[11][12] يُعتقد أن أنواع البشر القدماء المنفصلة قد نجت حتى حوالي 40.000 سنة مضت (انقراض النياندرتال).

الأسماء والتصنيف

باللاتينية، اسم homō (الجمع hominis) يعني "البشر" أو "الرجل" بالمعنى العام "الإنسان، البشرية".[ث] التسمية الثنائية "الإنسان العاقل" (Homo sapiens) صاغها كارلوس لينايوس (1758). (1758).[ج][15]

طُرحت أسنواع الأنواع الأخرى من الجنس بدءاً من النصف الثاني من القرن التاسع عشر (إنسان نيندرتال 1864، الإنسان المنتصب 1892).

حتى اليوم ، لم يتم تعريف الجنس "البشراني" بدقة.[16][17][18]

منذ أن بدأ سجل الأحفورات البشرية المبكرة في الظهور ببطء من تحت الأرض، وُضعت حدود وتعريفات الجنس "البشراني" بشكل سيء وفي حالة تغير مستمر باستمرار. لأنه لم يكن هناك سبب للاعتقاد بأنه سيحتوي على أي أعضاء إضافيين، لم يزعج كارلوس لينايوس حتى عناء تعريف الجنس "البشراني" عندما طرحه لأول مرة في القرن الثامن عشر. جلب اكتشاف النياندرتال الإضافة الأولى.

أُطلق على الجنس "البشراني" اسمه التصنيفي للإشارة إلى أن الأنوع المتضمنة هذا الجنس يمكن تصنيفها كبشر. وعلى مدار عقود القرن 20، أنتجت الاكتشافات الأحفورية للأنواع البشرية السابقة من أواخر العصر الميوسين وأوائل الپليوسيني مزيجًا غنيًا لمناقشة التصنيفات. هناك جدل مستمر حول تحديد الجنس "البشراني" من "الأسترالوپيثكس" - أو، في الواقع، تحديد الجنس "البشراني" من "Pan". ومع ذلك، فإن تصنيف الأحفورات "البشرانية" يتطابق مع دليل: (1) المشي البشري المتخصص على قدمين في "الإنسان الماهر" الموروث من "الأسترالوپيثكس" السابق لأكثر من أربعة ملايين سنة، كما يتضح من آثار أقدام لاتولي؛ و(2) على & nbsp ؛ ثقافة الأدوات البشرية بالتي دأت قبل 2.5 مليون سنة.[citation needed]

من أواخر القرن التاسع عشر حتى منتصف القرن العشرين، اقترح عدد من الأسماء التصنيفية الجديدة بما في ذلك أسماء عامة جديدة للأحفورات البشرية المبكرة. ومنذ ذلك الحين دُمج معظمها مع "الإنسان المنتصب" في الاعتراف بأن "الإنسان المنتصب" كان نوعًا واحدًا بانتشار جغرافي كبير للهجرات المبكرة. العديد من هذه الأسماء يطلق عليها الآن اسم "مرادفات" مع الجنس "البشراني"، بما في ذلك "الپيثكانثروپوس"،[19] "الپروتانثروپوس"،[20] "السينانثروپوس"،[21] "السيفانثروپوس"،[22] "الأفريكانثروپوس"،[23] "التلانثروپوس"،[24] "الأتلانثروپوس"،[25] و"التتشادانثروپوس".[26][27]

يخضع تصنيف الجنس "البشراني" إلى أنواع وتحت أنواع لمعلومات غير كاملة ويظل ضعيفًا. وقد أدى ذلك إلى استخدام الأسماء الشائعة ("إنسان نياندرتال" و"دينيسوڤان")، حتى في الأبحاث العلمية، لتجنب الأسماء الثلاثية أو غموض تصنيف المجموعات على أنها "أصنوفة غير محددة" (موضع غير مؤكد) - على سبيل المثال أو "إنسان نياندرتال" مقابل "إنسان نياندرتال العاقل" أو "إنسان جورجيا" مقابل "إنسان جورجيا المنتصب".[28]

اكتشفت بعض الأنواع المنقرضة مؤخرًا في الجنس "البشراني" وليس لها حتى الآن أسماء ثنائية متفق عليها (انظر إنسان دينيسوڤان).[29] منذ بداية العصر الهولوسيني، من المرجح أن "الإنسان العاقل" (الإنسان الحديث تشريحياً) هو النوع الوحيد الباقي من الجنس "البشراني".

كان جون إدوارد گراي (1825) من أوائل المدافعين عن تصنيف الأصنوفات عن طريق تعيين الأفرع الحيوية والفصائل.[30] أما وود وريتشموند (2000) فقد اقترحا أن يتم تعيين البشراناوية كفرع حيوي يتألف من جميع أنواع البشر المبكرة وسلالة البشر البدائيين حتى البشر الذي يعود تاريخهم لبعد الشمبانزي-البشر السلف المشترك الأخير أو بشراناوية ليتضمن فقط الجنس البشراني- والذي لا يتضمن البشرانوية السائرة على قدمين من العصر الپليوسيني مثل الأسترالوپيثكس، أوروين توگنسيس، الأرضيپيثكس، أو إنسان الساحل التشادي.[31] توجد تسميات بديلة لفرع البشراناوية الحيوي القائم، أو تم اقتراحها: "Australopithecina" (گريگوري وهلمان 1939) و"Preanthropinae" (سيلا-كوند وألتابا 2002)؛[32][33][34] ولاحقاً اقترح سيلا-كوند وأيالا (2003) أن الأجناس الأربعة Australopithecus، أرضيپيثكس، Praeanthropus، وإنسان الساحل التشادي يجب جمعها مع الجنس البشراني ضمن الفرع الحيوي أشباه البشر.[33]

التطور

الأسترالوپيثكس وظهور الهومو

العديد من الأنواع، من بينها أسترالوپيثكس گارهي، أسترالوپيثكس سديبا، أسترالوپيثكس أفريكانوس، وأسترالوپثيكس عفرنسس، اقترحت كسلف أو شقيقة للسلالة البشرانية.[35][36] لهذه الأنواع سمات مورفولوجية تتماشى مع الجنس "البشراني"، لكن لا يوجد إجماع على أيهما أدى إلى ظهور "البشراني". منذ عام 2010 على وجه الخصوص، أصبح تحديد الجنس "البشراني" ضمن "الأسترالوپيثكس" أكثر إثارة للجدل. تقليدياً، افترض ظهور "البشراني" بالتزامن مع الاستخدام الأول للأدوات الحجرية (صناعة أولدوانية)، وبالتالي من خلال التعريف مع بداية العصر الحجري القديم السفلي. لكن عام 2010، اقترح دليل يبدو أنه ينسب استخدام الأدوات الحجرية إلى "أسترالوپثيكس عفرنسس" منذ حوالي 3.3 مليون سنة، قبل حوالي مليون سنة من أول ظهور للبشراني.[37] LD 350-1، جزء أحفوري للفك السفلي يرجع تاريخه إلى 2.8 مليون سنة مضت، اكتشف في [[منطقة العفر|العفر، إثيوپيا عام 2013، وصفت بأنها تجمع بين "السمات البدائية التي شوهدت في وقت مبكر من "الأسترالوپثيكس" مع التشكل المشتق الذي لوحظ في "البشراني" لاحقاً.[38] يدفع بعض الباحثين بتطور البشراني إلى حوالي 3 مليون سنة مضت أو حتى ما بعدها.[ح] وجد هذا دعمًا في دراسة حديثة عن علم الوراثة في أشباه البشر والتي، باستخدام المعلومات المورفولوجية والجزيئية والإشعاعية، تؤرخ ظهور الجنس البشراني منذ 3.3 مليون سنة (4.30-2.56 مليون سنة). [39] أعرب آخرون عن شكوكهم فيما إذا كان يجب تضمين "الإنسان الماهر" ضمن الجنس "البشراني"، واقترحوا أصل "البشراني" مع "الإنسان المنتصب" منذ 1.9 مليون سنة مضت تقريبًا.[40]

إن التطور الفسيولوجي الأكثر بروزًا بين الأنواع السابقة من الأسترالوپثيكس و"البشراني" هو الزيادة في الحجم الداخلي للجمجمة (حجم المخ)، من حوالي 460 سم³ في "أ. أگارهي" إلى 660 سم³ في "الإنسان العاقل" وما بعده، إلى 1250 سم³ في "إنسان هايدلبرگ"، وما يصل إلى 1760 سم³ في "إنسان نياندرتال". ومع ذلك، فقط لوحظ بالفعل ارتفاع مطرد في حجم الجمجمة في "الأسترالوپثيكس" ولا ينتهي بعد ظهور الجنس "البشراني"، بحيث لا يعمل كمعيار موضوعي لتحديد ظهور الجنس.[41]

الإنسان الماهر

ظهر الإنسان الماهر منذ ما يقرب من 2.1 مليون سنة. قبل 2010، كان هناك بالفعل اقتراحات بأنه لا ينبغي وضع الإنسان الماهر ضمن الجنس "البشراني" لكن يجب تضمينه ضمن جنس "أسترالوپثيكس".[42][43] السبب الرئيسي لتضمين الإنسان الماهر ضمن الجنس البشراني، استخدامه للأدوات بمهارة مع اكتشاف إحدى أدوات جنس "أسترالوپثيكس"، التي استخدمت قبل مليون سنة على الأقل مستخدمة من قبل الإنسان الماهر.[37] علاوة على ذلك، اعتقد لفترة طويلة أن الإنسان العامل هو سلف للإنسان العامل الأكثر رشاقة (الإنسان المنتصب). عام 2007، اكتشف أن الإنسان العامل والإنسان المنتصب تواجدا معاً لفترة من الوقت، مما يقترح أن الإنسان المنتصب لم يتطور مباشرة من الإنسان الماهر، لكنه بدلاً من ذلك كان سلفاً مشترك.

[44] مع منشور جمجمة دمانيسي 5 عام 2013، أصبح من غير المؤكد أن الإنسان المنتصب الآسيوي هو من سلالة الإنسان العامل الأفريقي الذي كان بدوره سلفاً للإنسان الماهر. بدلاً من ذلك، يبدو أن الإنسان العامل والإنسان المنتصب هما متغيران من نفس النوع، والذي ربما قد نشءا في أفريقيا أو آسيا[45] وانتشرا على نطاق واسع في أرجاء أوراسيا (بما في ذلك أوروپا، إندونيسيا، والصين) منذ 0.5 مليون سنة مضت.[46]

الإنسان المنتصب

غالبًا ما يُفترض أن "الإنسان المنتصب" قد تطور انتقائياً من الإنسان الماهر منذ حوالي مليوني سنة. تعزز هذا السيناريو باكتشاف إنسان جورجيا المنتصب، عينات مبكرة من الإنسان المنتصب عثر عليها في القوقاز، والذي يبدو أنه يظهر سمات انتقالية من الإنسان الماهر. نظرًا لأن أول دليل على الإنسان المنتصب عثر عليه خارج أفريقيا، فقد كان من المعقول أن الإنسان المنتصب كان في أوراسيا ثم هاجر مرة أخرى إلى أفريقيا. استناداً لحفريات من تكوين كوبي فورا شرق بحيرة توركانا بكينيا، جدال سپور وزملائه (2007) بأن الإنسان الماهر ربما نجا بعد ظهور الإنسان المنتصب، لذا فإن الإنسان المنتصب لم يتطور انتقائياً، ولابد أن الإنسان المنتصب كان موجوداً بجانب الإنسان الماهر منذ حوالي نصف مليون سنة (1.9-1.4 مليون سنة مضت)، في أوائل المرحلة الكلابرية.[44]

عام 2010، افترض أن هناك نوعاً جنوب أفريقياً منفصلاً، إنسان گوتن، كان معاصراً للإنسان المنتصب.[47]

الشجرة الوراثية العرقية

−10 — – −9 — – −8 — – −7 — – −6 — – −5 — – −4 — – −3 — – −2 — – −1 — – 0 — |

| |||||||||||||||||||

يُقيم تصنيف الجنس البشراني ضمن القردة العليا على النحو التالي، مع ظهور الپارانثروپوس والبشراني ضمن جنس الأسترالوپيثكس (موضح هنا cladistically granting "الپارانثروپوس"، "الكينانثروپوس"، و"البشراني).[أ][ب][6][48][4][5][49][50][51][52][53][54][55][استشهاد مفرط] لا تزال الشجرة الوراثية العرقية الخاصة بجنس الأسترالوپيثكس تثير الكثير من الجدل. تظهر التواريخ الإشعاعية التقريبية للفروع الحيوية الوليدة بالمليون سنة مضت.[56][52] إنسان اليونان، إنسان الساحل التشادي، الأورورين الأشقاء محتملين للأسترالوپيثكس، غير مدرجين هنا. أحيانًا ما تكون تسمية المجموعات مشوشة حيث يفترض في كثير من الأحيان مجموعات معينة قبل إجراء أي تحليل تكويني.[50]

| القردة |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| (20.4 م.س.م.) |

| Australopithecines |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| (7.3 Mya) |

يبدو أن العديد من سلالات "البشراني" لديها ذرية على قيد الحياة من خلال التقديم إلى سلالات أخرى. تشير الدلائل الجينية إلى وجود سلالة قديمة تنفصل عن السلالات البشرية الأخرى منذ 1.5 مليون سنة، ربما الإنسان المنتصب، ربما تزاوج في دنيسوڤان منذ حوالي 55.000 سنة مضت.[57][49][58] تظهر الأدلة الأحفورية أن الإنسان المنتصب نجا على الأقل حتى 117.000 سنة مضت، وحتى أكثر من ذلك، فقد نجا إنسان فلورنسا قاعدياً حتى 50.000 سنة مضت. ويبدو أن هناك سلالة تشبه الإنسان المنتصب، والتي عاشت منذ 1.5 مليون سنة، قد شقت طريقها إلى الإنسان الحديث من خلال إنسان دنيسوڤان، وتحديداً سكان پاپوا والسكان الأصليين الأستراليين.[49] تُظهِر جينومات البشر الأفارقة من غير جنوب الصحراء ما يبدو أنه العديد من أحداث التطفل المستقلة التي تشمل إنسان نياندرتال وفي بعض الحالات أيضًا إنسان دنيسوڤان منذ حوالي 45.000 سنة.[59][58]

يبدو أن التركيب الجيني لبعض المجموعات الأفريقية الواقعة جنوب الصحراء يشير إلى الانحدار من سكان غرب أوراسيا منذ حوالي 3000 سنة مضت.[53][60]

تقترح بعض الأدلة أن أسترالوپيثكس سديبا ربما قد انتقل إلى الجنس البشراني، أو وُضع في جنس خاص به، بسبب موقعه بالنسبة للإنسان المنتصب وإنسان فلورنسا.[51][61]

الانتشار

منذ حوالي 1.8 مليون سنة مضت، كان الإنسان المنتصب متواجداً في شرق أفريقيا ("الإنسان العامل") وغرب آسيا ("إنسان جورجيا"). قد يكون أسلاف "إنسان فلوريس" الإندونيسي قد غادروا إفريقيا حتى قبل ذلك.[خ][51]

الإنسان المنتصب والأنواع ذات الصلة أو المنحدرة من الإنسان القديم على مدى 1.5 مليون سنة القادمة منتشرة في جميع أنحاء أفريقيا وأوراسيا[62][63] (انظر: الأصول الأفريقية الحديثة للإنسان المعاصر). وصل إنسان هايدلبرگ أوروپا منذ حوالي 0.5 مليون سنة مضت.

أما إنسان نياندرتال والإنسان العاقل فقد تطورا منذ حوالي 300 ألف سنة مضت. كان إنسان نالدي متواجداً في جنوب القارة الأفريقية منذ 300 ألف سنة مضت.

بعد فترة وجيزة من ظهوره الأول في أفريقيا، انتشر الإنسان العاقل في جميع أرجاء القارة، وانتقل إلى غرب آسيا في [[ H. sapiens بعد فترة وجيزة من ظهوره الأول انتشر في جميع أنحاء إفريقيا ، وإلى غرب آسيا في عدة موجات، ربما في وقت مبكر قبل 250 ألف سنة مضت، وبالتأكيد بحلول 130 ألف سنة مضت. في يوليو 2019، أفاد علماء الأنثروبولوجيا عن اكتشاف بقايا تعود إلى 210.000 سنة من الإنسان العاقل وأخرى عمرها 170.000 لإنسان نياندرتال في كهف أپيديما، پلوپونيز، اليونان، أقدم أكثر من 150.000 سنة من اكتشافات الإنسان العاقل الأخرى السابقة في أوروپا.[64][65][66]

أبرزها الانتشار الجنوبي للإنسان العاقل منذ حوالي حوالي 60 ألف سنة مضت، مما أدى إلى استمرار انتشار سكان أوقيانوسيا وأوراسيا بواسطة الإنسان الحديث تشريحياً.[11] حدث تزاوج بين الإنسان العاقل والبشر القدماء في أفريقيا وأوراسيا، وأبرزها مع النياندرتال ودنيسوڤان في أوراسيا.[67][68]

بين السكان الموجودين من الإنسان العاقل، تم العثور على أعمق تقسيم زمني لشعب السان من جنوب أفريقيا، يقدر بنحو 130.000 سنة،[69] أو ربما أكثر من 300.000 سنة مضت.[70]

التقسيم الزمني بين غير الأفارقة في حدود 60.000 سنة في حالة الأستراليين-الميكرونيزيين. تقسيم الأوروپيين والشرق آسيويين يبلغ حوالي 50.000 سنة، مع أحداث مختلطة متكررة وهامة في جميع أنحاء أوراسيا خلال الهولوسين.

ربما بقيت الأنواع البشرية القديمة على قيد الحياة حتى بداية الهولوسين، على الرغم من أنها انقرضت في الغالب أو اندمجت ضمن مجموعات الإنسان العاقل المتزايدة منذ 40 ألف سنة مضت تقريباً (انقراض إنسان نياندرتال).

المميزات

هناك عدة مميزات لجنس الهومو لا توجد في باقي الرئيسيات، وبعض هذه الصفات متواجدة لدى بعض الرئيسيات ولكن بصورة أقل بكثير مثل:

- حجم جمجمة كبير ويشمل حيزا كبيرا للمخ إذ يعتقد أنه نما بسبب ضعف وضيق عضلة اللثة

- المشي على اثنين وهي صفة يشترك في الإنسان مع الإنسان الحديث

- قدرة استيعاب واسعة وفهم للروابط والعلاقات بين الأشياء والتأثيرات المميزة للحركات والتغيرات المختلفة

- بناء أدوات معقدة واستخدام الادوات لصنع أدوات

- قدرة على الاتصال ولغة معقدة وميل طبيعي لتطوير لغة مشتركة مع بني جنسه وإن كانوا لا يشتركون في نفس اللغة.

تم حتى الآن اكتشاف عدد من الأنواع وإدراجها في تصنيف الإنسان كجنس وهي:

الإنسان الماهر، إنسان بحيرة رودولف، إنسان جورجيا، الإنسان العامل، الإنسان المنتصب إنسان سيبرانو، الإنسان السالف، إنسان هايدلبرگ، إنسان نياندرتال، إنسان روديسيا، إنسان فلوريس، الإنسان العاقل القديم، الإنسان الحديث تشريحياً: (الإنسان العاقل الأول، الإنسان العاقل العاقل).

قائمة السلالات

الوضع النوعي لإنسان بحيرة رودولف، الإنسان العامل إنسان جورجيا، سلف البشراني، إنسان القحف، إنسان روديسيا، إنسان نياندرتال، إنسان دنيسوڤا، وإنسان فلوريس لا زال قيد النقاش. يرتبط إنسان هايدلبيرگ وإنسان نياندرتال ارتباطًا وثيقًا ببعضها البعض واعتبرا تحت أنواع من من الإنسان العاقل.

تاريخياً، كان هناك توجه لافتراض أنواع بشرية جديدة تعتمد على القليل من الأحفورة الفردية. نهج "الحد الأدنى" للتصنيف البشري يعترف بثلاثة أنواع على الأكثر، "الإنسان الماهر (2.1-1.5 م.س.م، العضوية في الجنس البشراني مشكوك فيها) ، الإنسان المنتصب (1.8–0.1 م.س.م، بما في ذلك غالبية عمر الجنس، ومعظم الأنواع القديمة مثل تحت الأنواع،[71][72][73] بما في ذلك إنسان هايدلبيرگ كنوع متآخر أو فرعي[74][75][76]) والإنسان العاقل (300 م.س.م. حتى الوقت الحاضر، بما في ذلك إنسان نياندرتال وتنويعات أخرى باعتبارها تحت أنواع). لا تعني "الأنواع" في هذا السياق بالضرورة أن التهجين والإنجبال الداخلي كانا مستحيلاً في ذلك الوقت. ومع ذلك، غالبًا ما استخدم كمصطلح مناسب، لكن يجب اعتباره على أنه سلالة عامة في أحسن الأحوال، ومجموعات في أسوأ الأحوال. في التعاريف والمنهجية العامة لمعايير تحديد "الأنواع" غير متفق عليها بشكل عام في الأنثروبولوجيا أو علم الحفريات. في الواقع، يمكن للثدييات أن تنجبل داخلياً عادة لمدة 2 إلى 3 مليون سنة[77] أو أكثر،[78] لذلك من المحتمل أن تكون جميع "الأنواع" المعاصرة في الجنس "البشراني" قادرة على التزاوج داخلياً في ذلك الوقت، ولا يمكن استبعاد التطفل من خارج الجنس "البشراني".[79] اقترح أن إنسان ناليدي قد يكون هجيناً مع شبيه البشر الأسترالي الباقي على قيد لوقت متأخر (يعتبر أنه ما وراء "البشراني"،[48] على الرغم من حقيقة أن هذه السلالات تعتبر بشكل عام منقرضة منذ فترة طويلة. كما نوقش أعلاه، حدثت العديد من التقاربات بين الأنساب، مع وجود دليل على التقديم بعد انفصال 1.5 مليون سنة.

| السلالات | النطاق الزمني (kya) |

الموئل | ارتفاع البالغ | حجم البالغ | حجم المخ (سم3) |

السجل الأحفوري | الاكتشاف/ نشر الاسم |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| الإنسان الماهر العضوية في الهومو غير مؤكدة |

2.100–1.500[د][ذ] | تنزانيا | 110–140 سم | 33-55 كج | 510–660 | الكثير | 1960 1964 |

| إنسان بحيرة رودولف العضوية في الهومو غير مؤكدة |

1,900 | كينيا | 700 | 2 موقع | 1972 1986 | ||

| إنسان گوتن يُصنف أيضاً كإنسان عامل |

1.900–600 | جنوب أفريقيا | 100 سم | 3 أفراد[82][ر] | 2010 2010 | ||

| الإنسان المنتصب | 1.900–140[83][ز][84][س] | أفريقيا، أوراسيا | 180 سم | 60 كج | 850 (المبكر) – 1.100 (المتأخر) | الكثير [ش][ص] | 1891 1892 |

| الإنسان العامل الإنسان المنتصب الأفريقي |

1.800–1.300[86] | شرق وجنوب القارة الأفريقية | 700–850 | الكثير | 1949 1975 | ||

| سلف البشراني | 1.200–800 | غرب أوروبا | 175 سم | 90 كج | 1.000 | 2 موقع | 1994 1997 |

| إنسان هايدلبرگ إنسان نياندرتال المبكر |

600–300[ض] | أوروبا وأفريقيا | 180 سم | 90 كج | 1.100–1.400 | الكثير | 1907 1908 |

| إنسان القحف أحفورة مفردة، ربما إنسان هايدلبرگ |

c. 450[87] | إيطاليا | 1.000 | 1 غطاء الجمجمة | 1994 2003 | ||

| إنسان لونگي | 309–138[88] | شمال شرق الصين | 1.420[89] | 1 فرد | 1933 2021 | ||

| إنسان روديسيا الإنسان العاقل المبكر |

ح. 300 | زامبيا | 1.300 | واحدة أن عدد قليل | 1921 1921 | ||

| إنسان ناليدي | ح. 300[90] | جنوب أفريقيا | 150 سم | 45 كج | 450 | 15 فرد | 2013 2015 |

| الإنسان العاقل (الإنسان الحديث تشريحياً) |

c. 300–present[ط] | أنحاء العالم | 150–190 سم | 50-100 كج | 950–1.800 | (موجود) | —— 1758 |

| إنسان نياندرتال |

240–40[93][ظ] | أوروبا وغرب آسيا | 170 سم | 55-70 كج (ضخم البنية) |

1.200–1.900 | الكثير | 1829 1864 |

| إنسان فلورنسا التصنيف غير مؤكد |

190–50 | إندونيسيا | 100 سم | 25 كج | 400 | 7 فرد | 2003 2004 |

| إنسان نشر الرملة التصنيف غير مؤكد |

140–120 | إسرائيل | عدة أفراد | 2021 | |||

| إنسان پنگو ربما إنسان منتصب أو دنيسوڤا |

c. 100[ع] | تايوان | 1 فرد | 2008(?) 2015 | |||

| إنسان كالاو |

c. 67[96][97] | الفلپين | 3 أفراد | 2007 2019 | |||

| إنسان دنيسوڤا | 40 | سيبريا | 2 موقع | 2000 2010[غ] |

انظر أيضاً

- قائمة حفريات تطور الإنسان (بالصور)

- الأصول متعددة الأقاليم للإنسان الحديث

- تطور الإنسان

- خط زمني لتطور الإنسان

الهوامش

- ^ أ ب The conventional estimate on the age of H. habilis is at roughly 2.1 to 2.3 million years.[1][2] عام 2015، كان هناك اقتراحات لتأجيل العمر إلى 2.8 مليون سنة مضت بناءً على اكتشاف إحدى عظام الفك.[3]

- ^ أ ب The line to the earliest members of Homo were derived from Australopithecus, a genus which had separated from the Chimpanzee–human last common ancestor by late Miocene or early Pliocene times.[4]

- ^ Homo erectus in the narrow sense (the Asian species) was extinct by 140,000 years ago; H. erectus soloensis, found in Java, is considered the latest known survival of H. erectus. Formerly dated to as late as 50,000 to 40,000 years ago, a 2011 study pushed back the date of its extinction of H. e. soloensis to 143,000 years ago at the latest, more likely before 550,000 years ago.[6]

- ^ The word "human" itself is from Latin humanus, an adjective formed on the root of homo, thought to derive from a Proto-Indo-European word for "earth" reconstructed as *dhǵhem-.[13]

- ^ In 1959, Carl Linnaeus was designated as the lectotype for Homo sapiens[14] which means that following the nomenclatural rules, Homo sapiens was validly defined as the animal species to which Linnaeus belonged.

- ^ Cela-Conde & Ayala (2003) recognize five genera within Hominina: Ardipithecus, Australopithecus (including Paranthropus), Homo (including Kenyanthropus), Praeanthropus (including Orrorin), and Sahelanthropus.[33]

- ^ In a 2015 phylogenetic study, H. floresiensis was placed with Australopithecus sediba, H. habilis and Dmanisi Man, raising the possibility that the ancestors of H. floresiensis left Africa before the appearance of H. erectus, possibly even becoming the first hominins to do so and evolved further in Asia.[51]

- ^ Confirmed H. habilis fossils are dated to between 2.1 and 1.5 million years ago. This date range overlaps with the emergence of Homo erectus.[80][81]

- ^ Hominins with "proto-Homo" traits may have lived as early as 2.8 million years ago, as suggested by a fossil jawbone classified as transitional between Australopithecus and Homo discovered in 2015.

- ^ A species proposed in 2010 based on the fossil remains of three individuals dated between 1.9 and 0.6 million years ago. The same fossils were also classified as H. habilis, H. ergaster or Australopithecus by other anthropologists.

- ^ H. erectus may have appeared some 2 million years ago. Fossils dated to as much as 1.8 million years ago have been found both in Africa and in Southeast Asia, and the oldest fossils by a narrow margin (1.85 to 1.77 million years ago) were found in the Caucasus, so that it is unclear whether H. erectus emerged in Africa and migrated to Eurasia, or if, conversely, it evolved in Eurasia and migrated back to Africa.

- ^ Homo erectus soloensis, found in Java, is considered the latest known survival of H. erectus. Formerly dated to as late as 50,000 to 40,000 years ago, a 2011 study pushed back the date of its extinction of H. e. soloensis to 143,000 years ago at the latest, more likely before 550,000 years ago. [85]

- ^ Now also included in H. erectus are Peking Man (formerly Sinanthropus pekinensis) and Java Man (formerly Pithecanthropus erectus).

- ^ H. erectus is now grouped into various subspecies, including Homo erectus erectus, Homo erectus yuanmouensis, Homo erectus lantianensis, Homo erectus nankinensis, Homo erectus pekinensis, Homo erectus palaeojavanicus, Homo erectus soloensis, Homo erectus tautavelensis, Homo erectus georgicus. The distinction from descendant species such as Homo ergaster, Homo floresiensis, Homo antecessor, Homo heidelbergensis and indeed Homo sapiens is not entirely clear.

- ^ The type fossil is Mauer 1, dated to ca. 0.6 million years ago. The transition from H. heidelbergensis to H. neanderthalensis between 300 and 243 thousand years ago is conventional, and makes use of the fact that there is no known fossil in this period. Examples of H. heidelbergensis are fossils found at Bilzingsleben (also classified as Homo erectus bilzingslebensis).

- ^ The age of H. sapiens has long been assumed to be close to 200,000 years, but since 2017 there have been a number of suggestions extending this time to as high as 300,000 years. In 2017, fossils found in Jebel Irhoud (Morocco) suggest that Homo sapiens may have speciated by as early as 315,000 years ago.[91] Genetic evidence has been adduced for an age of roughly 270,000 years.[92]

- ^ The first humans with "proto-Neanderthal traits" lived in Eurasia as early as 0.6 to 0.35 million years ago (classified as H. heidelbergensis, also called a chronospecies because it represents a chronological grouping rather than being based on clear morphological distinctions from either H. erectus or H. neanderthalensis). There is a fossil gap in Europe between 300 and 243 kya, and by convention, fossils younger than 243 kya are called "Neanderthal".[94]

- ^ younger than 450 kya, either between 190–130 or between 70–10 kya[95]

- ^ provisional names Homo sp. Altai or Homo sapiens ssp. Denisova.

المصادر

- ^ Stringer, C.B. (1994). "Evolution of early humans". In Jones, S.; Martin, R.; Pilbeam, D. (eds.). The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Human Evolution. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 242.

- ^ Schrenk, F.; Kullmer, O.; Bromage, T. (2007). "Chapter 9: The Earliest Putative Homo Fossils". In Henke, W.; Tattersall, I. (eds.). Handbook of Paleoanthropology. pp. 1611–1631. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-33761-4_52.

- ^ Spoor, F.; Gunz, P.; Neubauer, S.; Stelzer, S.; Scott, N.; Kwekason, A.; Dean, M.C. (March 2015). "Reconstructed Homo habilis type OH 7 suggests deep-rooted species diversity in early Homo". Nature. 519 (7541): 83–86. Bibcode:2015Natur.519...83S. doi:10.1038/nature14224. PMID 25739632. S2CID 4470282.

- ^ أ ب ت Schuster AM (1997). "Earliest Remains of Genus Homo". Archaeology. 50 (1). Retrieved 5 March 2015.

- ^ أ ب Haile-Selassie Y, Gibert L, Melillo SM, Ryan TM, Alene M, Deino A, et al. (May 2015). "New species from Ethiopia further expands Middle Pliocene hominin diversity". Nature. 521 (7553): 483–8. Bibcode:2015Natur.521..483H. doi:10.1038/nature14448. PMID 26017448. S2CID 4455029.

- ^ أ ب ت Indriati E, Swisher CC, Lepre C, Quinn RL, Suriyanto RA, Hascaryo AT, et al. (2011). "The age of the 20 meter Solo River terrace, Java, Indonesia and the survival of Homo erectus in Asia". PLOS ONE. 6 (6): e21562. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...621562I. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0021562. PMC 3126814. PMID 21738710..

- ^ Callaway, E. (7 June 2017). "Oldest Homo sapiens fossil claim rewrites our species' history". Nature. doi:10.1038/nature.2017.22114. Retrieved 11 June 2017.

- ^ Posth C, Renaud G, Mittnik A, Drucker DG, Rougier H, Cupillard C, et al. (March 2016). "Pleistocene Mitochondrial Genomes Suggest a Single Major Dispersal of Non-Africans and a Late Glacial Population Turnover in Europe". Current Biology. 26 (6): 827–33. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2016.01.037. hdl:2440/114930. PMID 26853362. S2CID 140098861.

- ^ See:

- Karmin M, Saag L, Vicente M, Wilson Sayres MA, Järve M, Talas UG, et al. (April 2015). "A recent bottleneck of Y chromosome diversity coincides with a global change in culture". Genome Research. 25 (4): 459–66. doi:10.1101/gr.186684.114. PMC 4381518. PMID 25770088.

- Pagani L, Lawson DJ, Jagoda E, Mörseburg A, Eriksson A, Mitt M, et al. (October 2016). "Genomic analyses inform on migration events during the peopling of Eurasia". Nature. 538 (7624): 238–242. Bibcode:2016Natur.538..238P. doi:10.1038/nature19792. PMC 5164938. PMID 27654910.

- ^ Haber M, Jones AL, Connell BA, Arciero E, Yang H, Thomas MG, et al. (August 2019). "A Rare Deep-Rooting D0 African Y-Chromosomal Haplogroup and Its Implications for the Expansion of Modern Humans Out of Africa". Genetics. 212 (4): 1421–1428. doi:10.1534/genetics.119.302368. PMC 6707464. PMID 31196864.

- ^ أ ب Green RE, Krause J, Briggs AW, Maricic T, Stenzel U, Kircher M, et al. (May 2010). "A draft sequence of the Neandertal genome". Science. 328 (5979): 710–722. Bibcode:2010Sci...328..710G. doi:10.1126/science.1188021. PMC 5100745. PMID 20448178.

- ^ Lowery RK, Uribe G, Jimenez EB, Weiss MA, Herrera KJ, Regueiro M, Herrera RJ (November 2013). "Neanderthal and Denisova genetic affinities with contemporary humans: introgression versus common ancestral polymorphisms". Gene. 530 (1): 83–94. doi:10.1016/j.gene.2013.06.005. PMID 23872234. This study raises the possibility of observed genetic affinities between archaic and modern human populations being mostly due to common ancestral polymorphisms.

- ^ "The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language: Fourth Edition". 2000.

- ^ Stearn, W.T. (1959). "The background of Linnaeus's contributions to the nomenclature and methods of systematic biology". Systematic Zoology. 8 (1): 4–22. doi:10.2307/2411603. JSTOR 2411603.

- ^ von Linné, C. (1758). Systema naturæ. Regnum animale (10 ed.). Sumptibus Guilielmi Engelmann. pp. 18, 20. Retrieved 19 November 2012.

- ^ Schwartz, J.H.; Tattersall, I. (August 2015). "ANTHROPOLOGY. Defining the genus Homo". Science. 349 (6251): 931–932. Bibcode:2015Sci...349..931S. doi:10.1126/science.aac6182. PMID 26315422. S2CID 206639783.

- ^ Lents, N. (4 أكتوبر 2014). "Homo naledi and the problems with the Homo genus". The Wildernist. Archived from the original on 18 نوفمبر 2015. Retrieved 2 نوفمبر 2015.

- ^ Wood, B.; Collard, M. (April 1999). "The human genus". Science. 284 (5411): 65–71. Bibcode:1999Sci...284...65.. doi:10.1126/science.284.5411.65. PMID 10102822. S2CID 7018418.

- ^ "ape-man", from Pithecanthropus erectus (Java Man), Eugène Dubois, Pithecanthropus erectus: eine menschenähnliche Übergangsform aus Java (1894), identified with the Pithecanthropus alalus (i.e. "non-speaking ape-man") hypothesized earlier by Ernst Haeckel

- ^ Haeckel, Ernst (1895). "Protanthropus primigenius". Systematische Phylogenie. 3: p. 625.

early man

- ^ "Sinic man", from Sinanthropus pekinensis (Peking Man), Davidson Black (1927).

- ^ "crooked man", from Cyphanthropus rhodesiensis (Rhodesian Man) William Plane Pycraft (1928).

- ^ "African man", used by T.F. Dreyer (1935) for the Florisbad Skull he found in 1932 (also Homo florisbadensis or Homo helmei). Also the genus suggested for a number of archaic human skulls found at Lake Eyasi by Weinert (1938). Leaky, Journal of the East Africa Natural History Society' (1942), p. 43.

- ^ "remote man"; from Telanthropus capensis (Broom and Robinson 1949), see (1961), p. 487.

- ^ from Atlanthropus mauritanicus, name given to the species of fossils (three lower jaw bones and a parietal bone of a skull) discovered in 1954 to 1955 by Camille Arambourg in Tighennif, Algeria. Arambourg, C. (1955). "A recent discovery in human paleontology: Atlanthropus of ternifine (Algeria)". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 13 (2): 191–201. doi:10.1002/ajpa.1330130203.

- ^ Coppens, Y. (1965). "L'Hominien du Tchad". Actes V Congr. PPEC. I: 329f.

- ^ Coppens, Y. (1966). "Le Tchadanthropus". Anthropologia. 70: 5–16.

- ^ Vivelo, Alexandra (25 أغسطس 2013). Characterization of Unique Features of the Denisovan Exome (Masters thesis). California State University. hdl:10211.3/47490. Archived from the original on 29 أكتوبر 2013.

- ^ Barras, C. (14 مارس 2012). "Chinese human fossils unlike any known species". New Scientist. Retrieved 15 مارس 2012.

- ^ Gray, J.E. (1825). "An outline of an attempt at the disposition of Mammalia into Tribes and Families, with a list of genera apparently appertaining to each Tribe". Annals of Philosophy. new series: 337–344.

- ^ Wood & Richmond (2000), pp. 19–60

- ^ Brunet, M.; Guy, F.; Pilbeam, D.; Mackaye, H.T.; Likius, A.; Ahounta, D.; et al. (July 2002). "A new hominid from the Upper Miocene of Chad, Central Africa" (PDF). Nature. 418 (6894): 145–51. Bibcode:2002Natur.418..145B. doi:10.1038/nature00879. PMID 12110880. S2CID 1316969.

- ^ أ ب ت Cela-Conde, C.J.; Ayala, F.J. (June 2003). "Genera of the human lineage". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 100 (13): 7684–7689. Bibcode:2003PNAS..100.7684C. doi:10.1073/pnas.0832372100. PMC 164648. PMID 12794185.

- ^ Wood, B.; Lonergan, N. (April 2008). "The hominin fossil record: taxa, grades and clades" (PDF). Journal of Anatomy. 212 (4): 354–76. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7580.2008.00871.x. PMC 2409102. PMID 18380861.

- ^ Pickering, R.; Dirks, P.H.; Jinnah, Z.; de Ruiter, D.J.; Churchill, S.E.; Herries, A.I.; et al. (September 2011). "Australopithecus sediba at 1.977 Ma and implications for the origins of the genus Homo". Science. 333 (6048): 1421–1423. Bibcode:2011Sci...333.1421P. doi:10.1126/science.1203697. PMID 21903808. S2CID 22633702.

- ^ Asfaw, B.; White, T.; Lovejoy, O.; Latimer, B.; Simpson, S.; Suwa, G. (April 1999). "Australopithecus garhi: a new species of early hominid from Ethiopia". Science. 284 (5414): 629–635. Bibcode:1999Sci...284..629A. doi:10.1126/science.284.5414.629. PMID 10213683.

- ^ أ ب McPherron, S.P.; Alemseged, Z.; Marean, C.W.; Wynn, J.G.; Reed, D.; Geraads, D.; et al. (August 2010). "Evidence for stone-tool-assisted consumption of animal tissues before 3.39 million years ago at Dikika, Ethiopia". Nature. 466 (7308): 857–860. Bibcode:2010Natur.466..857M. doi:10.1038/nature09248. PMID 20703305. S2CID 4356816.

The oldest direct evidence of stone tool manufacture comes from Gona (Ethiopia) and dates to between 2.6 and 2.5 million years (Myr) ago. [...] Here we report stone-tool-inflicted marks on bones found during recent survey work in Dikika, Ethiopia [... showing] unambiguous stone-tool cut marks for flesh removal [..., dated] to between 3.42 and 3.24 Myr ago [...] Our discovery extends by approximately 800,000 years the antiquity of stone tools and of stone-tool-assisted consumption of ungulates by hominins; furthermore, this behaviour can now be attributed to Australopithecus afarensis.

- ^ See:

- Villmoare, B.; Kimbel, W.H.; Seyoum, C.; Campisano, C.J.; DiMaggio, E.N.; Rowan, J.; et al. (March 2015). "Paleoanthropology. Early Homo at 2.8 Ma from Ledi-Geraru, Afar, Ethiopia". Science. 347 (6228): 1352–1355. Bibcode:2015Sci...347.1352V. doi:10.1126/science.aaa1343. PMID 25739410..

- DiMaggio EN, Campisano CJ, Rowan J, Dupont-Nivet G, Deino AL, Bibi F, et al. (March 2015). "Paleoanthropology. Late Pliocene fossiliferous sedimentary record and the environmental context of early Homo from Afar, Ethiopia". Science. 347 (6228): 1355–1359. Bibcode:2015Sci...347.1355D. doi:10.1126/science.aaa1415. PMID 25739409.

- ^ Püschel, Hans P.; Bertrand, Ornella C.; O’Reilly, Joseph E.; Bobe, René; Püschel, Thomas A. (June 2021). "Divergence-time estimates for hominins provide insight into encephalization and body mass trends in human evolution". Nature Ecology & Evolution. 5 (6): 808–819. doi:10.1038/s41559-021-01431-1. PMID 33795855. S2CID 232764044.

- ^ Wood, Bernard (28 June 2011). "Did early Homo migrate "out of" or "in to" Africa?". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 108 (26): 10375–10376. Bibcode:2011PNAS..10810375W. doi:10.1073/pnas.1107724108. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 3127876. PMID 21677194.

the adaptive coherence of Homo would be compromised if H. habilis is included in Homo. Thus, if these arguments are accepted the origins of the genus Homo are coincident in time and place with the emergence of H. erectus, not H. habilis.

- ^ Kimbel, W.H.; Villmoare, B. (July 2016). "From Australopithecus to Homo: the transition that wasn't". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences. 371 (1698): 20150248. doi:10.1098/rstb.2015.0248. PMC 4920303. PMID 27298460.

A fresh look at brain size, hand morphology and earliest technology suggests that a number of key Homo attributes may already be present in generalized species of Australopithecus, and that adaptive distinctions in Homo are simply amplifications or extensions of ancient hominin trends. [...] the adaptive shift represented by the ECV of Australopithecus is at least as significant as the one represented by the ECV of early Homo, and that a major 'grade-level' leap in brain size with the advent of H. erectus is probably illusory.

- ^ Wood & Richmond (2000), p. 41: "A recent reassessment of cladistic and functional evidence concluded that there are few, if any, grounds for retaining H. habilis in Homo, and recommended that the material be transferred (or, for some, returned) to Australopithecus (Wood & Collard, 1999)."

- ^ Miller, J.M. (May 2000). "Craniofacial variation in Homo habilis: an analysis of the evidence for multiple species". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 112 (1): 103–128. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1096-8644(200005)112:1<103::AID-AJPA10>3.0.CO;2-6. PMID 10766947.

- ^ أ ب

Spoor, F.; Leakey, M.G.; Gathogo, P.N.; Brown, F.H.; Antón, S.C.; McDougall, I.; et al. (August 2007). "Implications of new early Homo fossils from Ileret, east of Lake Turkana, Kenya". Nature. 448 (7154): 688–691. Bibcode:2007Natur.448..688S. doi:10.1038/nature05986. PMID 17687323. S2CID 35845.

A partial maxilla assigned to H. habilis reliably demonstrates that this species survived until later than previously recognized, making an anagenetic relationship with H. erectus unlikely. The discovery of a particularly small calvaria of H. erectus indicates that this taxon overlapped in size with H. habilis, and may have shown marked sexual dimorphism. The new fossils confirm the distinctiveness of H. habilis and H. erectus, independently of overall cranial size, and suggest that these two early taxa were living broadly sympatrically in the same lake basin for almost half a million years.

- ^ Agustí J, Lordkipanidze D (June 2011). "How "African" was the early human dispersal out of Africa?". Quaternary Science Reviews. 30 (11–12): 1338–1342. Bibcode:2011QSRv...30.1338A. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2010.04.012.

- ^ Prins, H.E.; Walrath, D.; McBride, B. (2007). Evolution and prehistory: the human challenge. Wadsworth Publishing. p. 162. ISBN 978-0-495-38190-7..

- ^ Curnoe, D. (June 2010). "A review of early Homo in southern Africa focusing on cranial, mandibular and dental remains, with the description of a new species (Homo gautengensis sp. nov.)". HOMO. 61 (3): 151–77. doi:10.1016/j.jchb.2010.04.002. PMID 20466364.

- ^ أ ب Berger, L.R.; Hawks, J.; Dirks, P.H.; Elliott, M.; Roberts, E.M. (May 2017). Perry, G.H. (ed.). "Homo naledi and Pleistocene hominin evolution in subequatorial Africa". eLife. 6: e24234. doi:10.7554/eLife.24234. PMC 5423770. PMID 28483041.

- ^ أ ب ت Mondal, M.; Bertranpetit, J.; Lao, O. (January 2019). "Approximate Bayesian computation with deep learning supports a third archaic introgression in Asia and Oceania". Nature Communications. 10 (1): 246. Bibcode:2019NatCo..10..246M. doi:10.1038/s41467-018-08089-7. PMC 6335398. PMID 30651539.

- ^ أ ب Zeitoun, V. (September 2003). "High occurrence of a basicranial feature in Homo erectus: anatomical description of the preglenoid tubercle". The Anatomical Record Part B: The New Anatomist. 274 (1): 148–156. doi:10.1002/ar.b.10028. PMID 12964205.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Dembo M, Matzke NJ, Mooers AØ, Collard M (August 2015). "Bayesian analysis of a morphological supermatrix sheds light on controversial fossil hominin relationships". Proceedings. Biological Sciences. 282 (1812): 20150943. doi:10.1098/rspb.2015.0943. PMC 4528516. PMID 26202999.

- ^ أ ب Dembo M, Radovčić D, Garvin HM, Laird MF, Schroeder L, Scott JE, et al. (August 2016). "The evolutionary relationships and age of Homo naledi: An assessment using dated Bayesian phylogenetic methods". Journal of Human Evolution. 97: 17–26. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2016.04.008. hdl:2164/8796. PMID 27457542.

- ^ أ ب Ko, K.H. (December 2016). "Hominin interbreeding and the evolution of human variation". Journal of Biological Research. 23 (1): 17. doi:10.1186/s40709-016-0054-7. PMC 4947341. PMID 27429943.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Harrison, N. (1 May 2019). The Origins of Europeans and Their Pre-Historic Innovations from 6 Million to 10,000 BCE: From 6 Million to 10,000 BCE. Algora Publishing. ISBN 9781628943795.

- ^ See:

- Strait D, Grine F, Fleagle J (2015). Analyzing Hominin Hominin Phylogeny: Cladistic Approach. pp. 1989–2014 (cladogram p. 2006). ISBN 978-3-642-39978-7..

- Mounier, A.; Caparros, M. (2015). "The phylogenetic status of Homo heidelbergensis – a cladistic study of Middle Pleistocene hominins". BMSAP (in الفرنسية). 27 (3–4): 110–134. doi:10.1007/s13219-015-0127-4. ISSN 0037-8984. S2CID 17449909.

- Rogers AR, Harris NS, Achenbach AA (February 2020). "Neanderthal-Denisovan ancestors interbred with a distantly related hominin". Science Advances. 6 (8): eaay5483. Bibcode:2020SciA....6.5483R. doi:10.1126/sciadv.aay5483. PMC 7032934. PMID 32128408.

- ^ Püschel, Hans P.; Bertrand, Ornella C.; O’Reilly, Joseph E.; Bobe, René; Püschel, Thomas A. (June 2021). "Divergence-time estimates for hominins provide insight into encephalization and body mass trends in human evolution". Nature Ecology & Evolution. 5 (6): 808–819. doi:10.1038/s41559-021-01431-1. PMID 33795855. S2CID 232764044.

- ^ See:

- Dediu, D.; Levinson, S.C. (1 June 2018). "Neanderthal language revisited: not only us". Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences. The Evolution of Language. 21: 49–55. doi:10.1016/j.cobeha.2018.01.001. hdl:21.11116/0000-0000-1667-4. ISSN 2352-1546. S2CID 54391128.

- Hubisz, M.J.; Williams, A.L.; Siepel, A. (August 2020). "Mapping gene flow between ancient hominins through demography-aware inference of the ancestral recombination graph". PLOS Genetics. 16 (8): e1008895. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1008895. PMC 7410169. PMID 32760067.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - Kuhlwilm M, Gronau I, Hubisz MJ, de Filippo C, Prado-Martinez J, Kircher M, et al. (February 2016). "Ancient gene flow from early modern humans into Eastern Neanderthals". Nature. 530 (7591): 429–33. Bibcode:2016Natur.530..429K. doi:10.1038/nature16544. PMC 4933530. PMID 26886800.

- Prüfer K, Racimo F, Patterson N, Jay F, Sankararaman S, Sawyer S, et al. (January 2014). "The complete genome sequence of a Neanderthal from the Altai Mountains". Nature. 505 (7481): 43–9. Bibcode:2014Natur.505...43P. doi:10.1038/nature12886. PMC 4031459. PMID 24352235.

- ^ أ ب Callaway, E. (2016). "Evidence mounts for interbreeding bonanza in ancient human species". Nature News. doi:10.1038/nature.2016.19394. S2CID 87029139.

- ^ Varki, A. (April 2016). "Why are there no persisting hybrids of humans with Denisovans, Neanderthals, or anyone else?". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 113 (17): E2354. Bibcode:2016PNAS..113E2354V. doi:10.1073/pnas.1602270113. PMC 4855598. PMID 27044111.

- ^ Pickrell JK, Patterson N, Loh PR, Lipson M, Berger B, Stoneking M, et al. (February 2014). "Ancient west Eurasian ancestry in southern and eastern Africa". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 111 (7): 2632–2637. arXiv:1307.8014. Bibcode:2014PNAS..111.2632P. doi:10.1073/pnas.1313787111. PMC 3932865. PMID 24550290.

- ^ Groves C (2017). "Progress in human systematics. A review". Paradigmi (2): 59–74. doi:10.3280/PARA2017-002005. ISSN 1120-3404.

- ^ Beyin, A. (2011). "Upper Pleistocene Human Dispersals out of Africa: A Review of the Current State of the Debate". International Journal of Evolutionary Biology. 2011 (615094): 615094. doi:10.4061/2011/615094. PMC 3119552. PMID 21716744.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Callaway, E. (March 2016). "Oldest ancient-human DNA details dawn of Neanderthals". Nature. 531 (7594): 286. Bibcode:2016Natur.531..296C. doi:10.1038/531286a. PMID 26983523. S2CID 4459329.

- ^ Zimmer, C. (10 July 2019). "A Skull Bone Discovered in Greece May Alter the Story of Human Prehistory - The bone, found in a cave, is the oldest modern human fossil ever discovered in Europe. It hints that humans began leaving Africa far earlier than once thought". The New York Times. Retrieved 11 July 2019.

- ^ Staff (10 July 2019). "'Oldest remains' outside Africa reset human migration clock". Phys.org. Retrieved 10 July 2019.

- ^ Harvati, K.; Röding, C.; Bosman, A.M.; Karakostis, F.A.; Grün, R.; Stringer, C.; et al. (July 2019). "Apidima Cave fossils provide earliest evidence of Homo sapiens in Eurasia". Nature. 571 (7766): 500–504. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1376-z. PMID 31292546. S2CID 195873640.

- ^ Reich D, Green RE, Kircher M, Krause J, Patterson N, Durand EY, et al. (December 2010). "Genetic history of an archaic hominin group from Denisova Cave in Siberia" (PDF). Nature. 468 (7327): 1053–1060. Bibcode:2010Natur.468.1053R. doi:10.1038/nature09710. hdl:10230/25596. PMC 4306417. PMID 21179161.

- ^ Reich D, Patterson N, Kircher M, Delfin F, Nandineni MR, Pugach I, et al. (October 2011). "Denisova admixture and the first modern human dispersals into Southeast Asia and Oceania". American Journal of Human Genetics. 89 (4): 516–528. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.09.005. PMC 3188841. PMID 21944045.

- ^ Henn BM, Gignoux CR, Jobin M, Granka JM, Macpherson JM, Kidd JM, et al. (March 2011). "Hunter-gatherer genomic diversity suggests a southern African origin for modern humans". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 108 (13): 5154–5162. Bibcode:2011PNAS..108.5154H. doi:10.1073/pnas.1017511108. PMC 3069156. PMID 21383195.

- ^ Schlebusch CM, Malmström H, Günther T, Sjödin P, Coutinho A, Edlund H, et al. (November 2017). "Southern African ancient genomes estimate modern human divergence to 350,000 to 260,000 years ago". Science. 358 (6363): 652–655. Bibcode:2017Sci...358..652S. doi:10.1126/science.aao6266. PMID 28971970.

- ^ Perkins, Sid (17 October 2013). "Skull suggests three early human species were one". Nature News & Comment.

- ^ Switek, B. (17 October 2013). "Beautiful Skull Spurs Debate on Human History". National Geographic. Retrieved 22 September 2014.

- ^ Lordkipanidze D, Ponce de León MS, Margvelashvili A, Rak Y, Rightmire GP, Vekua A, Zollikofer CP (October 2013). "A complete skull from Dmanisi, Georgia, and the evolutionary biology of early Homo". Science. 342 (6156): 326–31. Bibcode:2013Sci...342..326L. doi:10.1126/science.1238484. PMID 24136960. S2CID 20435482.

- ^ "Homo heidelbergensis - The evolutionary dividing line between Homo erectus and modern humans was not sharp". Dennis O'Neil. Archived from the original on 9 March 2016. Retrieved November 29, 2015.

- ^ Mounier, A.; Marchal, F.; Condemi, S. (March 2009). "Is Homo heidelbergensis a distinct species? New insight on the Mauer mandible". Journal of Human Evolution. 56 (3): 219–246. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2008.12.006. PMID 19249816.

- ^ Lieberman, D.E.; McBratney, B.M.; Krovitz, G. (February 2002). "The evolution and development of cranial form in Homosapiens". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 99 (3): 1134–1139. Bibcode:2002PNAS...99.1134L. doi:10.1073/pnas.022440799. PMC 122156. PMID 11805284.

- ^ Wilson, A.C.; Maxson, L.R.; Sarich, V.M. (July 1974). "Two types of molecular evolution. Evidence from studies of interspecific hybridization". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 71 (7): 2843–2847. Bibcode:1974PNAS...71.2843W. doi:10.1073/pnas.71.7.2843. PMC 388568. PMID 4212492.

- ^ Popadin, K.; Gunbin, K.; Peshkin, L.; Annis, S.; Kraytsberg, Y.; Markuzon, N.; et al. (19 October 2017). "Mitochondrial pseudogenes suggest repeated inter-species hybridization among direct human ancestors". bioRxiv. 134502. doi:10.1101/134502.

- ^ Ackermann, R.R.; Arnold, M.L.; Baiz, M.D.; Cahill, J.A.; Cortés-Ortiz, L.; Evans, B.J.; et al. (July 2019). "Hybridization in human evolution: Insights from other organisms". Evolutionary Anthropology. 28 (4): 189–209. doi:10.1002/evan.21787. hdl:2027.42/151330. PMC 6980311. PMID 31222847.

- ^ Schrenk F, Kullmer O, Bromage T (2007). "The Earliest Putative Homo Fossils". In Henke W, Tattersall I (eds.). Handbook of Paleoanthropology. Vol. 1. In collaboration with Thorolf Hardt. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer. pp. 1611–1631. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-33761-4_52. ISBN 978-3-540-32474-4.

- ^ DiMaggio, E.N.; Campisano, C.J.; Rowan, J.; Dupont-Nivet, G.; Deino, A.L.; Bibi, F.; et al. (March 2015). "Paleoanthropology. Late Pliocene fossiliferous sedimentary record and the environmental context of early Homo from Afar, Ethiopia". Science. 347 (6228): 1355–9. Bibcode:2015Sci...347.1355D. doi:10.1126/science.aaa1415. PMID 25739409. S2CID 43455561.

- ^ Curnoe, D. (June 2010). "A review of early Homo in southern Africa focusing on cranial, mandibular and dental remains, with the description of a new species (Homo gautengensis sp. nov.)". HOMO. 61 (3): 151–177. doi:10.1016/j.jchb.2010.04.002. PMID 20466364.

- ^ Haviland WA, Walrath D, Prins HE, McBride B (2007). Evolution and Prehistory: The Human Challenge (8th ed.). Belmont, CA: Thomson Wadsworth. p. 162. ISBN 978-0-495-38190-7.

- ^ Ferring R, Oms O, Agustí J, Berna F, Nioradze M, Shelia T, et al. (June 2011). "Earliest human occupations at Dmanisi (Georgian Caucasus) dated to 1.85-1.78 Ma". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 108 (26): 10432–6. Bibcode:2011PNAS..10810432F. doi:10.1073/pnas.1106638108. PMC 3127884. PMID 21646521.

- ^ Indriati, E.; Swisher, C.C.; Lepre, C.; Quinn, R.L.; Suriyanto, R.A.; Hascaryo, A.T.; et al. (2011). "The age of the 20 meter Solo River terrace, Java, Indonesia and the survival of Homo erectus in Asia". PLOS ONE. 6 (6): e21562. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...621562I. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0021562. PMC 3126814. PMID 21738710.

- ^ Hazarika M (2007). "Homo erectus/ergaster and Out of Africa: Recent Developments in Paleoanthropology and Prehistoric Archaeology" (PDF). EAA Summer School eBook. Vol. 1. European Anthropological Association. pp. 35–41.

Intensive Course in Biological Anthrpology, 1st Summer School of the European Anthropological Association, 16–30 June 2007, Prague, Czech Republic

- ^ Muttoni G, Scardia G, Kent DV, Swisher CC, Manzi G (2009). "Pleistocene magnetochronology of early hominin sites at Ceprano and Fontana Ranuccio, Italy". Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 286 (1–2): 255–268. Bibcode:2009E&PSL.286..255M. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2009.06.032.

- ^ Ji, Q.; Wu, W.; Ji, Y.; Li, Q.; Ni, X. (25 June 2021). "Late Middle Pleistocene Harbin cranium represents a new Homo species". The Innovation. 2 (3): 100132. Bibcode:2021Innov...200132J. doi:10.1016/j.xinn.2021.100132. PMC 8454552. PMID 34557772.

- ^ Ni X, Ji Q, Wu W, Shao Q, Ji Y, Zhang C, Liang L, Ge J, Guo Z, Li J, Li Q, Grün R, Stringer C (25 June 2021). "Massive cranium from Harbin in northeastern China establishes a new Middle Pleistocene human lineage". The Innovation. 2 (3): 100130. Bibcode:2021Innov...200130N. doi:10.1016/j.xinn.2021.100130. PMC 8454562. PMID 34557770.

- ^ Dirks, P.H.; Roberts, E.M.; Hilbert-Wolf, H.; Kramers, J.D.; Hawks, J.; Dosseto A.; et al. (May 2017). "Homo naledi and associated sediments in the Rising Star Cave, South Africa". eLife. 6: e24231. doi:10.7554/eLife.24231. PMC 5423772. PMID 28483040.

- ^ Callaway, Ewan (7 June 2017). "Oldest Homo sapiens fossil claim rewrites our species' history". Nature. doi:10.1038/nature.2017.22114. Retrieved 11 June 2017.

- ^ Posth, C.; Wißing, C.; Kitagawa, K.; Pagani, L.; van Holstein, L.; Racimo, F.; et al. (July 2017). "Deeply divergent archaic mitochondrial genome provides lower time boundary for African gene flow into Neanderthals". Nature Communications. 8: 16046. Bibcode:2017NatCo...816046P. doi:10.1038/ncomms16046. PMC 5500885. PMID 28675384.

- ^ Bischoff JL, Shamp DD, Aramburu A, et al. (March 2003). "The Sima de los Huesos Hominids Date to Beyond U/Th Equilibrium (>350 kyr) and Perhaps to 400–500 kyr: New Radiometric Dates". Journal of Archaeological Science. 30 (3): 275–280. Bibcode:2003JArSc..30..275B. doi:10.1006/jasc.2002.0834. ISSN 0305-4403.

- ^ Dean, D.; Hublin, J.J.; Holloway, R.; Ziegler, R. (May 1998). "On the phylogenetic position of the pre-Neandertal specimen from Reilingen, Germany". Journal of Human Evolution. 34 (5): 485–508. doi:10.1006/jhev.1998.0214. PMID 9614635.

- ^ Chang, C.H.; Kaifu, Y.; Takai, M.; Kono, R.T.; Grün, R.; Matsu'ura, S.; et al. (January 2015). "The first archaic Homo from Taiwan". Nature Communications. 6: 6037. Bibcode:2015NatCo...6.6037C. doi:10.1038/ncomms7037. PMC 4316746. PMID 25625212.

- ^ Détroit, F.; Mijares, A.S.; Corny, J.; Daver, G.; Zanolli, C.; Dizon, E.; et al. (April 2019). "A new species of Homo from the Late Pleistocene of the Philippines" (PDF). Nature. 568 (7751): 181–186. Bibcode:2019Natur.568..181D. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1067-9. PMID 30971845. S2CID 106411053.

- ^ Zimmer C (10 أبريل 2019). "A new human species once lived in this Philippine cave – Archaeologists in Luzon Island have turned up the bones of a distantly related species, Homo luzonensis, further expanding the human family tree". The New York Times. Retrieved 10 أبريل 2019.

المراجع

- Wood, Bernard; Richmond, Brian G. (July 2000). "Human evolution: taxonomy and paleobiology". Journal of Anatomy. 197 (1): 19–60. doi:10.1046/j.1469-7580.2000.19710019.x. PMC 1468107. PMID 10999270.

وصلات خارجية

- Exploring the Hominid Fossil Record (Center for the Advanced Study of Hominid Paleobiology at George Washington University)

- Hominid species

- Prominent Hominid Fossils

- Mikko's Phylogeny archive

فشل عرض الخاصية P830: لم يتم العثور على الخاصية P830.

"بشراني" at the Encyclopedia of Life- Human Timeline (Interactive) – Smithsonian, National Museum of Natural History (August 2016).

- CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI

- CS1 الفرنسية-language sources (fr)

- الصفحات بخصائص غير محلولة

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Automatic taxobox cleanup

- Articles containing إنگليزية-language text

- Pages using Lang-xx templates

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Articles with unsourced statements from September 2021

- Citation overkill

- Articles tagged with the inline citation overkill template from December 2021

- تطور بشري

- رئيسيات

- أنواع البشراني المبكرة

- بشر

- بشراناوية

- أجناس الرئيسيات

- أصنوفات سماها كارل لينايوس

- أجناس ثدييات بنوع واحد على قيد الحياة