الإدمان

| الإدمان | |

|---|---|

| الأسماء الأخرى | اضطراب استعمال المواد الشديد[1][2] |

| |

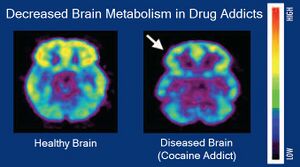

| صور التصوير المقطعي بالإصدار البوزيتروني للدماغ التي تقارن التمثيل الغذائي للدماغ في فرد سليم وفرد مصاب بإدمان الكوكايين | |

| التخصص | الطب النفسي ، علم النفس السريري ، علم السموم ، طب الإدمان |

| مسرد الإدمان والإعتياد [3][4][5][2] | |

|---|---|

| |

الإدمان (إنگليزية: Addiction)، بالاتينية (PROCLIVITAS) هو اضطراب نفسي اجتماعي يتميز بالاشتراك القهري في مكافأة المنبهات على الرغم من العواقب السلبية.[3][5][2][6][7][8]مجموعة متنوعة من العوامل العصبية الحيوية المعقدة[3]والنفسية الاجتماعية[9] مشتركة في تطور الإدمان، مع النموذج السائد بين الباحثين في الولايات المتحدة هو نموذج أمراض الدماغ، على الرغم من وجود جدل داخل المجال حول المساهمة النسبية لأي عامل معين.[10][11][12][13][14][15] تشمل السمات المميزة للإدمان ضعف التحكم في المواد (المخدرات) أو السلوك، والانشغال بالمواد أو السلوك، والاستمرار في الاستخدام على الرغم من العواقب.[9][16] عادة ما تتميز العادات والأنماط المرتبطة بالإدمان بالإشباع الفوري (مكافأة قصيرة الأجل)، إلى جانب الآثار الضارة المتأخرة (التكاليف طويلة الأجل)).[9][17]

تشمل الأمثلة على المخدرات والإدمان السلوكي إدمان الكحول وإدمان الماريجوانا وإدمان الأمفيتامين وإدمان الكوكايين وإدمان النيكوتين وإدمان المواد الأفيونية وإدمان الطعام وإدمان الشوكولاتة وإدمان ألعاب الڤيديو وإدمان القمار والإدمان الجنسي. الإدمان السلوكي الوحيد المعترف به بواسطة DSM-5 (الدليل التشخيصي والإحصائي للاضطرابات النفسية (الطبعة الخامسة)و ICD-10 (المراجعة العاشرة للتصنيف الدولي للأمراض)هو إدمان القمار. مع إدخال ICD-11، تم إلحاق إدمان الألعاب.[18] كثيرًا ما يُساء استخدام مصطلح "الإدمان" عند الإشارة إلى سلوكيات أو اضطرابات قهرية أخرى، لا سيما الاعتماد، في وسائل الإعلام.[19] من الاختلافات المهمة بين إدمان المخدرات والاعتماد عليها أن الاعتماد عليها هو اضطراب يؤدي فيه التوقف عن تعاطي المخدرات إلى حالة غير محببة من الانسحاب، مما قد يؤدي إلى مزيد من تعاطي المخدرات.[20]الإدمان هو الاستخدام القهري لمادة أو أداء سلوك مستقل عن الانسحاب. يمكن أن يحدث الإدمان في غياب الاعتماد، ويمكن أن يحدث الاعتماد في حالة عدم وجود إدمان، على الرغم من أن الاثنين يحدثان معًا في كثير من الأحيان.

التاريخ والتسمية

غالبًا ما يُساء فهم أصل كلمة مصطلح الإدمان عبر التاريخ واتخذ معاني مختلفة مرتبطة بالكلمة. مثال على ذلك هو استخدام الكلمة خلال الفترة الحديثة المبكرة. "الإدمان" في ذلك الوقت كان يعني "الارتباط" بشيء ما، مما يمنحه دلالات إيجابية وسلبية. يمكن وصف موضوع هذا المرفق بأنه "جيد أو سيئ".[21] ومع ذلك، ارتبط معنى الإدمان خلال هذه الفترة بالإيجابية والخير. خلال العصر الديني للغاية، كان يُنظر إليه على أنه طريقة "لتكريس الذات للآخر".[21]

أدت الأبحاث الحديثة حول الإدمان إلى فهم أفضل للمرض من خلال الدراسات البحثية حول هذا الموضوع التي يعود تاريخها إلى عام 1875، وتحديداً حول إدمان المورفين.[22] عزز هذا من فهم الإدمان كونه حالة طبية. لم يُنظر إلى الإدمان حتى القرن التاسع عشر ويُعترف به في العالم الغربي على أنه مرض، كونه حالة جسدية ومرض عقلي.[23]يُفهم الإدمان اليوم على أنه اضطراب بيولوجي نفسي اجتماعي يؤثر سلبًا على من يتأثرون به، ويرتبط في الغالب بتعاطي المخدرات والكحول.[9] لقد تغير فهم الإدمان عبر التاريخ، مما أثر ولا يزال يؤثر على طرق علاجه وتشخيصه طبيًا.

الآثار

يتسبب الإدمان في "خسائر مالية وبشرية باهظة بشكل مذهل" على الأفراد والمجتمع ككل.[24][25][26] في الولايات المتحدة، التكلفة الاقتصادية الإجمالية التي يتحملها المجتمع أكبر من جميع أنواع مرض السكري وجميع أنواع السرطان مجتمعة.[26] تنشأ هذه التكاليف من الآثار السلبية المباشرة للأدوية وتكاليف الرعاية الصحية المرتبطة بها (على سبيل المثال، الخدمات الطبية الطارئة ورعاية المرضى الخارجيين والداخليين)، والمضاعفات طويلة الأجل (على سبيل المثال، سرطان الرئة الناتج عن تدخين منتجات التبغ وتليف الكبد والخرف من استهلاك الكحول المزمن، وفم الميث الناتج عن استخدام الميثامفيتامين)، وفقدان الإنتاجية وتكاليف الرعاية المرتبطة بها، والحوادث المميتة وغير المميتة (على سبيل المثال، الاصطدامات المرورية)، والانتحار، والقتل، والحبس، من بين أمور أخرى.[24][25][26][27] في الولايات المتحدة، وجدت دراسة أجراها المعهد الوطني لتعاطي المخدرات أن الوفيات الناجمة عن الجرعات الزائدة في الولايات المتحدة قد تضاعفت ثلاث مرات تقريبًا بين الذكور والإناث من عام 2002 إلى عام 2017، حيث تم الإبلاغ عن 72306 حالة وفاة بسبب الجرعة الزائدة في عام 2017 في الولايات المتحدة.[28]تميز العام 2020 بأكبر عدد من الوفيات بسبب الجرعات الزائدة على مدى 12 شهرًا، مع 81000 حالة وفاة بسبب الجرعة الزائدة، متجاوزة الأرقام القياسية المسجلة في عام 2017.[29]

علم النفس العصبي

يمثل التحكم المعرفي والتضبيط بالمحفز، المرتبط بالإشراط الاستثابي والكلاسيكي، عمليات معاكسة (على سبيل المثال، داخلية مقابل خارجية أو بيئية، على التوالي) تتنافس على التحكم في سلوكيات الفرد المستنبطة.[30] التحكم المعرفي، وخاصة السيطرة المثبطة على السلوك، ضعيفة في كل من الإدمان وقصور الإنتباه وفرط الحركة.[31][32] تميل الاستجابات السلوكية التي يحركها الحافز (أي التحكم في المنبهات) المرتبطة بمحفز مكافاءة معين إلى السيطرة على سلوك الفرد في حالة الإدمان.[32]

التحكم التحفيزي في السلوك

التحكم المعرفي في السلوك

الإدمان السلوكي

يشير مصطلح "الإدمان السلوكي" إلى القهر على الانخراط في مكافأة طبيعية - وهو سلوك يعود بطبيعته إلى المكافأة (على سبيل المثال، مرغوب فيها أو جذابة) - على الرغم من العواقب السلبية.[7][33][34] أثبتت الأدلة قبل السريرية أن الزيادات الملحوظة في التعبير عن ΔFosB من خلال التعرض المتكرر والمفرط لمكافأة طبيعية تؤدي إلى نفس التأثيرات السلوكية واللدونة العصبية كما يحدث في إدمان المخدرات.[33][35][36][37]

حددت مراجعات كل من الأبحاث السريرية في البشر والدراسات قبل السريرية التي تتضمن ΔFosB النشاط الجنسي القهري - على وجه التحديد، أي شكل من أشكال الجماع الجنسي - كإدمان (أي الإدمان الجنسي ).[33][35] علاوة على ذلك، فقد ثبت أن المكافئة التحسسية المتبادلة بين الأمفيتامين والنشاط الجنسي، مما يعني أن التعرض لأحدهما يزيد من الرغبة في كليهما، يحدث قبل الإكلينيكي والسريري كمتلازمة خلل تنظيم الدوبامين;[33][35][36][37] تعبير ΔFosB مطلوب لتأثير التحسس المتبادل هذا، والذي يتكثف مع مستوى التعبير FosB.[33][36][37]

تشير مراجعات الدراسات قبل السريرية إلى أن الاستهلاك المتكرر والمفرط على المدى الطويل للأطعمة التي تحتوي على نسبة عالية من الدهون أو السكر يمكن أن يؤدي إلى الإدمان ( إدمان الطعام ).[33][34] يمكن أن يشمل ذلك الشيوكلاتة. من المعروف أن النكهة الحلوة للشوكولاتة والمكونات الدوائية تخلق رغبة قوية أو تشعر "بالإدمان" من قبل المستهلك.[38] قد يشير الشخص الذي يحب الشيوكلاتة إلى نفسه على أنه مدمن للشيوكلاتة. لم يتم التعرف على الشوكولاتة رسميًا من قبل DSM-5 كإدمان قابل للتشخيص.[39]

تقدم المقامرة مكافأة طبيعية مرتبطة بالسلوك القهري والتي حددت لها أدلة التشخيص السريري، أي DSM-5، معايير تشخيص "الإدمان".[33] من أجل أن يلبي سلوك المقامرة لدى الشخص معايير الإدمان، فإنه يظهر خصائص معينة، مثل تعديل الحالة المزاجية والقسر والانسحاب. هناك دليل من التصوير العصبي الوظيفي على أن المقامرة تنشط نظام المكافأة والمسار الوسطي الطرفي على وجه الخصوص.[33][40] وبالمثل، يرتبط التسوق ولعب ألعاب الفيديو بالسلوكيات القهرية لدى البشر، وقد ثبت أيضًا أنهما ينشطان المسار الوسطي الطرفي وأجزاء أخرى من نظام المكافآت.[33] بناءً على هذا الدليل، يتم تصنيف إدمان القمار وإدمان ألعاب الڤيديو وإدمان التسوق وفقًا لذلك.[33][40]

عوامل الخطر

هناك عدد من عوامل الخطر الجينية والبيئية لتطوير الإدمان، والتي تختلف باختلاف السكان.[3][41] عوامل الخطر الجينية والبيئية تمثل كل منها ما يقرب من نصف خطر إصابة الفرد بالإدمان;[3][41] مساهمة عوامل الخطر اللاجينية في إجمالي المخاطر غير معروفة، حتى في الأفراد الذين لديهم مخاطر وراثية منخفضة نسبيًا، فإن التعرض لجرعات عالية بما فيه الكفاية من عقار مسبب للإدمان لفترة طويلة من الزمن (على سبيل المثال، أسابيع - أشهر) يمكن أن يؤدي إلى الإدمان.[3]

العوامل الوراثية

تم تحديد العوامل الوراثية، إلى جانب العوامل البيئية (مثل العوامل النفسية والاجتماعية)، كمساهمين مهمين في قابلية الإدمان.[3][41] تقدر الدراسات الوبائية أن العوامل الوراثية مسؤولة عن 40-60٪ من عوامل الخطر للإدمان على الكحول.[42] أشارت دراسات أخرى إلى معدلات وراثية مماثلة لأنواع أخرى من إدمان المخدرات، وتحديداً في الجينات التي تشفر مستقبلات ألفا 5 نيكوتينيك أسيتيل كولين.[43] افترض Knestler في عام 1964 أن الجين أو مجموعة الجينات قد تساهم في التأهب للإدمان بعدة طرق. على سبيل المثال، قد تغير المستويات المتغيرة من البروتين الطبيعي بسبب العوامل البيئية بنية أو عمل الخلايا العصبية في الدماغ أثناء التطور. يمكن أن تؤثر هذه الخلايا العصبية المتغيرة في الدماغ على قابلية الفرد لتجربة تعاطي المخدرات الأولية. لدعم هذه الفرضية، أظهرت الدراسات على الحيوانات أن العوامل البيئية مثل الإجهاد يمكن أن تؤثر على التعبير الجيني للحيوان.[43]

في البشر، قدمت دراسات التوائم حول الإدمان بعضًا من أعلى الأدلة جودة على هذا الارتباط، ووجدت النتائج أنه إذا تأثر أحد التوأمين بالإدمان، من المحتمل أن يكون التوأم الآخر كذلك، وغالبًا ما يكون لنفس المادة.[44] دليل آخر على المكون الجيني هو نتائج البحث من دراسات الأسرة التي تشير إلى أنه إذا كان أحد أفراد الأسرة لديه تاريخ من الإدمان، فإن فرص أحد الأقارب أو الأسرة المقربة في تطوير نفس العادات تكون أعلى بكثير من الشخص الذي لم يتم تعرضه للإدمان في في سن مبكر.[45]

ومع ذلك، فإن البيانات التي تضمن جينات معينة في تطوير إدمان المخدرات مختلطة بالنسبة لمعظم الجينات. تركز العديد من دراسات الإدمان التي تهدف إلى تحديد جينات معينة على المتغيرات الشائعة التي يزيد تكرار الأليل فيها عن 5٪ في عموم السكان ؛ ومع ذلك، عند ارتباطها بالمرض، فإنها تمنح فقط قدرًا صغيرًا من المخاطر الإضافية مع نسبة أرجحية تبلغ 1.1 - 1.3٪ ؛ وقد أدى ذلك إلى تطوير فرضية المتغير النادر، والتي تنص على أن الجينات ذات الترددات المنخفضة في السكان (أقل من 1٪) تمنح مخاطر إضافية أكبر بكثير في تطور المرض.[46]

تُستخدم دراسات الارتباط الجينومي الكامل (GWAS) لفحص الارتباطات الجينية مع الاعتماد والإدمان وتعاطي المخدرات ؛ ومع ذلك، نادرًا ما تحدد هذه الدراسات الجينات من البروتينات الموصوفة سابقًا عبر نماذج الضربة القاضية الحيوانية وتحليل الجينات المرشحة. بدلاً من ذلك، يتم تحديد نسب كبيرة من الجينات المشاركة في عمليات مثل التصاق الخلية بشكل شائع. لا يمكن عادةً التقاط التأثيرات المهمة للأنماط الداخلية للظهور بهذه الطرق. قد تشارك الجينات التي تم تحديدها في GWAS لإدمان المخدرات إما في تعديل سلوك الدماغ قبل تجارب المخدرات، أو بعد ذلك، أو كليهما.[47]

العوامل البيئية

عوامل الخطر البيئية للإدمان هي تجارب الفرد خلال حياته التي تتفاعل مع التركيب الجيني للفرد لزيادة أو تقليل تعرضه للإدمان.[3] على سبيل المثال، بعد اندلاع COVID-19 على الصعيد الوطني، أقلع المزيد من الناس عن التدخين (مقابل بدأوا) ؛ كما أن المدخنين، في المتوسط، قللوا من كمية السجائر التي يستهلكونها.[48] بشكل عام، تضمنت عدد من العوامل البيئية المختلفة كعوامل خطر للإدمان، بما في ذلك الضغوطات النفسية والاجتماعية المختلفة. يشير المعهد الوطني لتعاطي المخدرات (NIDA) إلى الافتقار إلى الإشراف الأبوي، وانتشار تعاطي المخدرات من قبل الأقران، وتوافر المخدرات، والفقر كعوامل خطر لتعاطي المخدرات بين الأطفال والمراهقين.[49] يفترض نموذج أمراض الدماغ المتعلقة بالإدمان أن تعرض الفرد لعقار يسبب الإدمان هو أهم عامل خطر بيئي للإدمان.[50] ومع ذلك، يشير العديد من الباحثين، بما في ذلك علماء الأعصاب، إلى أن نموذج أمراض الدماغ يقدم تفسيرًا مضللًا وغير مكتمل وربما يكون ضارًا للإدمان.[51]

تجارب الطفولة الضارة (ACEs) هي أشكال مختلفة من سوء المعاملة والخلل الوظيفي المنزلي الذي يعاني منه الطفولة. أظهرت دراسة تجارب الطفولة الضارة التي أجرتها مراكز السيطرة على الأمراض والوقاية منها وجود علاقة قوية بين الجرعات والاستجابة بين تجارب الطفولة الضارة والعديد من المشكلات الصحية والاجتماعية والسلوكية طوال عمر الشخص، بما في ذلك تعاطي المخدرات.[52] يمكن أن يتعطل النمو العصبي للأطفال بشكل دائم عندما يتعرضون بشكل مزمن لأحداث مرهقة مثل الاعتداء الجسدي أو العاطفي أو الجنسي، أو الإهمال الجسدي أو العاطفي، أو مشاهدة العنف في المنزل، أو سجن أحد الوالدين أو معاناته من مرض عقلي. نتيجة لذلك، قد تتأثر الوظائف المعرفية للطفل أو قدرته على التعامل مع المشاعر السلبية أو المضطربة. بمرور الوقت، قد يتبنى الطفل تعاطي المخدرات كآلية للتكيف، خاصة خلال فترة المراهقة.[52]وجدت دراسة أجريت على 900 قضية قضائية تتعلق بأطفال تعرضوا للإيذاء أن عددًا كبيرًا منهم يعانون من شكل من أشكال الإدمان في فترة المراهقة أو البالغين.[53] يمكن تجنب هذا المسار نحو الإدمان الذي يتم فتحه من خلال التجارب المجهدة أثناء الطفولة من خلال تغيير العوامل البيئية طوال حياة الفرد وفرص المساعدة المهنية.[53] إذا كان لدى المرء أصدقاء أو أقران يتعاطون المخدرات بشكل إيجابي، تزداد فرص إدمانهم. الصراع الأسري وإدارة المنزل هو أيضًا سبب للانخراط في تعاطي الكحول أو تعاطي المخدرات الأخرى.[54]

العمر

تمثل المراهقة فترة قابلية فريدة لتطوير الإدمان.[55] في مرحلة المراهقة، تنضج أنظمة المكافآت التحفيزية في الدماغ جيدًا قبل مركز التحكم المعرفي. وهذا بالتالي يمنح أنظمة المكافآت التحفيزية قدرًا غير متناسب من القوة في عملية صنع القرار السلوكي. لذلك، من المرجح بشكل متزايد أن يتصرف المراهقون بناءً على دوافعهم والانخراط في سلوك محفوف بالمخاطر، يحتمل أن يؤدي إلى الإدمان قبل التفكير في العواقب.[56] ليس المراهقون فقط أكثر عرضة لبدء استخدام المخدرات والحفاظ عليه، ولكن بمجرد إدمانهم يصبحون أكثر مقاومة للعلاج وأكثر عرضة للانتكاس.[57][58]

أظهرت الإحصاءات أن أولئك الذين بدأوا في شرب الكحول في سن أصغر هم أكثر عرضة للاعتماد عليه فيما بعد. حوالي 33٪ من السكان[أين؟] أظهرت الإحصاءات أن أولئك الذين بدأوا في شرب الكحول في سن أصغر هم أكثر عرضة للاعتماد عليه فيما بعد. حوالي 33٪ من السكان تذوقوا أول مشروب كحولي لهم بين سن 15 و 17 سنة، بينما 18٪ جربوه قبل ذلك. أما بالنسبة لتعاطي الكحوليات أو الاعتماد عليها، فإن الأعداد تبدأ مرتفعة مع من شربوا قبل بلوغهم سن الثانية عشرة ثم ينخفضون بعد ذلك. على سبيل المثال، بدأ 16٪ من مدمني الكحول الشرب قبل بلوغ سن 12 عامًا، بينما 9٪ فقط شربوا الكحول لأول مرة بين 15 و 17 عامًا. هذه النسبة أقل من ذلك، حيث تصل إلى 2.6٪، لأولئك الذين بدأوا هذه العادة لأول مرة بعد سن 21 عامًا[59]

يتعرض معظم الأفراد للعقاقير المسببة للإدمان ويستخدمونها لأول مرة خلال سنوات المراهقة.[60] في الولايات المتحدة، كان هناك ما يزيد قليلاً عن 2.8 مليون متعاط جديد للعقاقير الغير مشروعة في عام 2013 (حوالي 7800 مستخدم جديد يوميًا) [60]من بينهم 54.1٪ كانوا تحت سن 18 سنة.[60] في عام 2011، كان هناك ما يقرب من 20.6 مليون شخص في الولايات المتحدة فوق سن 12 يعانون من الإدمان.[61] أكثر من 90٪ من المدمنين بدأوا في الشرب أو التدخين أو تعاطي العقاقير الغير مشروعة قبل سن 18 عامًا.[61]

الاضطرابات المرضية

الأفراد الذين يعانون من اضطرابات الصحة العقلية المرضية (أي التي تحدث بشكل متزامن) مثل الاكتئاب والقلق واضطراب قصور الانتباه مع فرط الحركة (ADHD) أو اضطراب ما بعد الصدمة هم أكثر عرضة للإصابة باضطرابات تعاطي المخدرات.[62][63][64] تستشهد NIDA بالسلوك العدواني المبكر كعامل خطر لتعاطي المخدرات.[49] وجدت دراسة أجراها المكتب الوطني للبحوث الاقتصادية أن هناك "علاقة مؤكدة بين المرض العقلي واستخدام المواد المسببة للإدمان" وأن غالبية مرضى الصحة العقلية يشاركون في استخدام هذه المواد: 38٪ كحول، 44٪ كوكايين، و 40٪ سجائر.[65]

علم التخلق

الوراثة التخلقية الجينية عبر الأجيال

تعد الجينات التخلقية ومنتجاتها (مثل البروتينات) هي المكونات الرئيسية التي يمكن للتأثيرات البيئية من خلالها أن تؤثر على جينات الفرد;[41] كما أنها تعمل كآلية مسؤولة عن الوراثة المتعلقة بالتخلق عبر الأجيال، وهي ظاهرة يمكن أن تؤثر فيها التأثيرات البيئية على جينات أحد الوالدين على السمات المرتبطة والأنماط الظاهرية السلوكية لنسلهم (على سبيل المثال، الاستجابات السلوكية للمنبهات البيئية).[41] في الإدمان، تلعب الآليات التخلقية دورًا مركزيًا في الفيزيولوجيا المرضية للمرض;[3] في الإدمان، تلعب الآليات التخلقية دورًا مركزيًا في الفيزيولوجيا المرضية للمرض ؛ لقد لوحظ أن بعض التغييرات التي تطرأ على مافوق الجينوم والتي تنشأ من خلال التعرض المزمن لمحفزات إدمانية أثناء الإدمان يمكن أن تنتقل عبر الأجيال، مما يؤثر بدوره على سلوك الأطفال (على سبيل المثال، استجابات الطفل السلوكية للعقاقير المسببة للإدمان والمكافآت الطبيعية )).[41][66]

تشمل الفئات العامة للتغييرات التخلقية التي تورطت في الوراثة المتعلقة بالتخلقية عبر الأجيال مثيلة الحمض النووي، وتعديلات هيستون، والتنظيم بالنقصان أو بالزيادة لرنا الميكروي.[41]فيما يتعلق بالإدمان، هناك حاجة إلى مزيد من البحث لتحديد التغييرات الوراثية المتعلقة بالتخلقية المحددة التي تنشأ من أشكال مختلفة من الإدمان لدى البشر والأنماط الظاهرية السلوكية المقابلة من هذه التعديلات التخلقية التي تحدث في سلالة الإنسان.[41][66] استنادًا إلى الأدلة قبل السريرية من الأبحاث على الحيوانات، يمكن أن تنتقل بعض التغيرات التخلقية التي يسببها الإدمان في الفئران من الوالدين إلى النسل وتنتج أنماطًا سلوكية تقلل من مخاطر النسل في تطوير الإدمان.[note 1][41] بشكل عام، قد تعمل الأنماط الظاهرية السلوكية الموروثة المشتقة من التغيرات التخلقية التي يسببها الإدمان والتي تنتقل من الأب إلى الأبناء إما على زيادة أو تقليل مخاطر إصابة النسل بالإدمان.[41][66]

الميول لسوء الاستخدام

الميول لإساءة الاستخدام، والتي تُعرف أيضًا باسم قابلية الإدمان، هي الميل إلى تعاطي المخدرات في حالة غير طبية. هذا عادة بسبب النشوة أو تغير المزاج أو التخدير.[67] يتم استخدام الميول لإساءة الاستخدام عندما يريد الشخص الذي يستخدم المخدرات شيئًا لا يمكنه الحصول عليه بخلاف ذلك. الطريقة الوحيدة للحصول على ذلك هي من خلال استخدام العقاقير. عند النظر في الميول لإساءة الاستخدام، هناك عدد من العوامل المحددة فيما إذا كان قد تم إساءة استخدام الدواء. هذه العوامل هي: التركيب الكيميائي للدواء، وتأثيراته على الدماغ، والعمر، وسرعة التأثر، والصحة (العقلية والبدنية) للسكان محل الدراسة.[67] هناك عدد قليل من الأدوية ذات التركيبة الكيميائية المحددة التي تؤدي إلى ميول كبير لإساءة الاستخدام. هذه هي: الكوكايين، الهيروين، المستنشقات، الماريجوانا، MDMA (الإكستاسي)، الميثامفيتامين، الفينول الخماسي الكلور، القنب الصناعي، الكاثينونات الاصطناعية (أملاح الاستحمام)، التبغ، والكحول.[68]

الآليات

نموذج مرض الدماغ

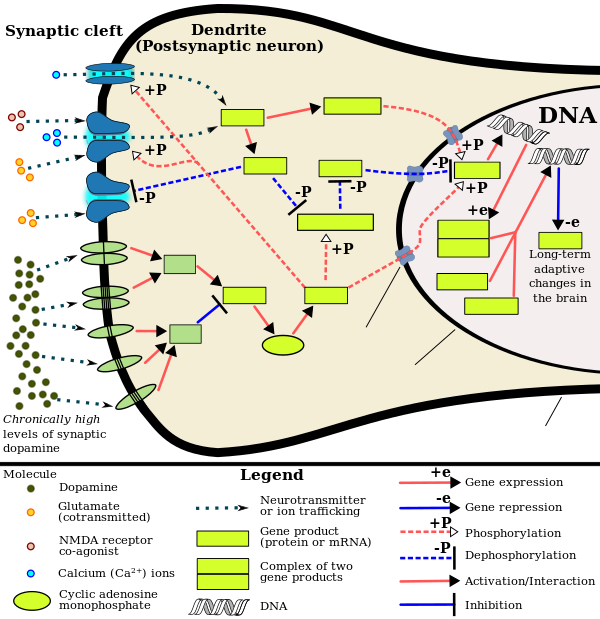

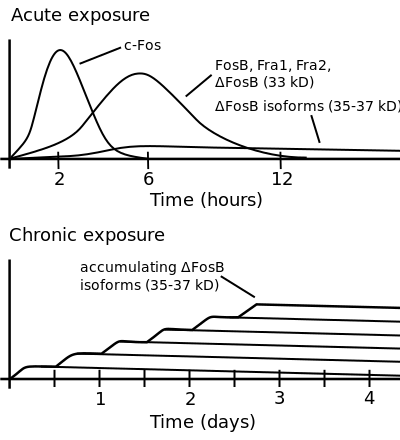

يصور نموذج مرض الدماغ الإدمان على أنه اضطراب في نظام المكافأة في الدماغ يتطور من خلال آليات النسخ و التخلق كنتيجة لمستويات عالية بشكل مزمن من التعرض لمحفز الإدمان (على سبيل المثال، تناول الطعام، واستخدام الكوكايين، والمشاركة في النشاط الجنسي، والمشاركة في الأنشطة الثقافية عالية التشويق مثل المقامرة وما إلى ذلك) على مدى فترة زمنية طويلة.[3][69][33] دلتاΔFosB) FosB،) عامل نسخ الجينات، هو عنصر حاسم وعامل مشترك في تطوير جميع أشكال الإدمان السلوكي والمخدرات.[69][33][70][34] أظهر عقدين من البحث في دور ΔFosB في الإدمان أن الإدمان ينشأ، ويكثف السلوك القهري المرتبط به أو يخفف، جنبًا إلى جنب مع الإفراط في التعبير عن ΔFosB في الخلايا العصبية الشوكية المتوسطة من النوع D1 للنواة المتكئة.[3][69][33][70] نظرًا للعلاقة السببية بين تعبير ΔFosB والإدمان، يتم استخدامه قبل السريري كعلامة حيوية للإدمان.[3][69][70] ينظم تعبير ΔFosB في هذه الخلايا العصبية بشكل مباشر وإيجابي الإعطاء الذاتي للعقار وتحسس المكافاْة من خلال التعزيز الإيجابي، مع تقليل الحساسية للنفور.[note 2][3][69]

| معجم عوامل النسخ |

|---|

| • النسخ – نسخ الدنا الذي يقوم به پوليمريز الرنا إلى مرسال الرنا |

| • عامل – مادة، مثل الپروتين، تساهم في سبب تفاعل كيميائي حيوي معين أو عملية جسدية |

| • تنظيم النسخ – التحكمفي معدل نسخ الجينات على سبيل المثال من خلال مساعدة أو إعاقة ربط پوليمريز الرنا بالدنا |

| • تحسين التنظيم، التنشيط، أو التعزيز – يزيد معدل نسخ الجين |

| • تقليل التنظيم، القمع، أو التثبيط – يقلل معدل نسخ الجين |

| • المنشط المرافق – بروتين يعمل مع عوامل النسخ لزيادة معدل نسخ الجين |

| • تميم الكاظمة – بروتين يعمل مع عوامل النسخ لتخفيض معدل نسخ الجينات |

| عدِّل |

يتسبب تعاطي المخدرات المسببة للإدمان المزمن في حدوث تغييرات في التعبير الجيني في إسقاط القشرة الحوفية المتوسطة.[34][78][79] أهم عوامل النسخ التي تنتج هذه التعديلات هي ΔFosB، وبروتين ربط عنصر استجابة أحادي فوسفات الأدينوسين الحلقي (CREB )،والعامل النووي كابا ب(NF-κB).[34]تعتبر ΔFosB هي الآلية الجزيئية الحيوية الأكثر أهمية في الإدمان لأن الإفراط في التعبير عن ΔFosB في الخلايا العصبية الشوكية المتوسطة من النوع D1 في النواة المتكئة ضروري وكافي للعديد من التكيفات العصبية والتأثيرات السلوكية (على سبيل المثال، تزداد التعبيرات المعتمدة في الاعطاء الذاتي للعقار و تحسس المكافأة) يُلاحظ في إدمان المخدرات.[34] تعبير ΔFosB في النواة المتكئة للخلايا العصبية المتوسطة من النوع D1 ينظم بشكل مباشر وإيجابي الإعطاء الذاتي للعقار وتحسس المكافأة من خلال التعزيز الإيجابي مع تقليل الحساسية للنفور.[note 2][3][69] ΔFosB مشترك في التوسط في الإدمان للعديد من العقاقير وأصناف العقاقير المختلفة، بما في ذلك الكحول والأمفيتامين والأمفيتامينات البديلة الأخرى، القنب، الكوكايين، الميثيل فينيدات، النيكوتين، المواد الأفيونية، فينيلسيكلدين، والبروبوفول، من بين أمور أخرى.[69][34][78][80][81] ΔJunD، عامل النسخ، و G9a، هيستون ميثيل ترانسفيراز، كلاهما يعارضان وظيفة ΔFosB ويمنعان الزيادات في تعبيره.[3][34][82] الزيادات في تعبير Δ JunD في النواة المتكئة (عن طريق نقل الجينات بوساطة ناقلات فيروسية ) أو تعبير G9a (عبر الوسائل الدوائية) يقلل، أو مع زيادة كبيرة يمكن حتى أن يمنع، العديد من التغيرات العصبية والسلوكية التي تنتج عن الاستخدام المزمن للجرعات العالية العقاقير المسببة للإدمان (أي التغييرات بوساطة ΔFosB).[70][34]

يلعب ΔFosB أيضًا دورًا مهمًا في تنظيم الاستجابات السلوكية للمكافآت الطبيعية، مثل الطعام اللذيذ والجنس والتمارين الرياضية.[34][83] تحفز المكافآت الطبيعية، مثل تعاطي المخدرات، التعبير الجيني عن ΔFosB في النواة المتكئة، ويمكن أن يؤدي الاستحواذ المزمن لهذه المكافآت إلى حالة إدمان مرضية مماثلة من خلال التعبير المفرط عن ΔFosB.[33][34][83] وبالتالي، فإن ΔFosB هو عامل النسخ الرئيسي المتضمن في الإدمان على المكافآت الطبيعية (أي الإدمان السلوكي) أيضًا;[34][33][83] علي وجه الخصوص، ΔFosB في النواة المتكئة أمر بالغ الأهمية لتعزيز تأثيرات المكافأة الجنسية.[83] تشير الأبحاث حول التفاعل بين المكافآت الطبيعية والمكافآت الدوائية إلى أن المنشطات النفسية الدوبامينية (مثل الأمفيتامين ) والسلوك الجنسي تعمل على آليات جزيئية حيوية مماثلة لتحفيز ΔFosB في النواة المتكئة وتمتلك تأثيرات تحسس ثنائية الاتجاه يتم التوسط فيها من خلال ΔFosB.[33][36][37] هذه الظاهرة جديرة بالملاحظة، حيث لوحظ في البشر متلازمة خلل تنظيم الدوبامين، والتي تتميز بالمشاركة القهرية التي يسببها الدواء في المكافآت الطبيعية (على وجه التحديد، النشاط الجنسي والتسوق والقمار)، وقد لوحظ أيضًا في بعض الأفراد الذين يتناولون أدوية الدوبامين.[33]

قد تكون مثبطاتΔFOSB (الأدوية أو العلاجات التي تعارض عملها) علاجًا فعالًا للإدمان واضطرابات الإدمان.[84]

يلعب إطلاق الدوپامين في النواة المتكئة دورًا في تعزيز الصفات للعديد من أشكال المنبهات، بما في ذلك المنبهات المعززة بشكل طبيعي مثل الطعام اللذيذ والجنس.[85][86] كثيرا ما لوحظ تغير انتقال الدوبامين العصبي بعد تطور حالة إدمان.[33] في البشر وحيوانات المختبر التي أظهرت إدمانًا، تظهر التغيرات في الدوبامين أو النقل العصبي الأفيوني في النواة المتكئة وأجزاء أخرى من الجسم المخطط.[33] لقد وجدت الدراسات أن استخدام بعض الأدوية (مثل الكوكايين ) يؤثر على الخلايا العصبية الكولينية التي تعصب نظام المكافأة، مما يؤثر بدوره على إشارات الدوبامين في هذه المنطقة.[87]

نظام المكافأة

This section requires expansion. (August 2015) |

المسار الوسطي الطرفي

تراكم ΔFosB من سوء استخدام العقاقير المفرط

أعلى: يوضح هذا التأثيرات الأولية للتعرض بجرعات عالية من عقار مسبب للإدمان على التعبير الجيني في النواة المتكئة لعائلة بروتينات Fos المختلفة (i.e., c-Fos, FosB, ΔFosB, Fra1, و Fra2).

أسفل: يوضح هذا الزيادة التدريجية في تعبير FosB في النواة المتكئة بعد نوبات تعاطي المخدرات المتكررة مرتين يوميًا , حيث تستمر هذة الفسفرة (35–37 كيلو دالتون) ΔFosB اشكال أيسوية في نوع D1-type الخلايا العصبية الشوكية المتوسطة للنواة المتكئة لمدة تصل إلى شهرين.[76][88] |

يعد فهم المسارات التي تعمل بها المخدرات وكيف يمكن للعقاقير أن تغير هذه المسارات أمرًا أساسيًا عند فحص الأساس البيولوجي لإدمان المخدرات. يتميز مسار المكافأة، المعروف باسم المسار الوسطي الطرفي، أو امتداده، مسار القشرة الوسطية الطرفية، بالتفاعل بين عدة مناطق من الدماغ.

- الإسقاطات من المنطقة السقيفية البطنية (VTA) هي شبكة من الخلايا العصبية الدوپامينية مع مستقبلات الگلوتامات بعد المشبكي المشتركة (AMPAR و NMDAR). تستجيب هذه الخلايا عند وجود محفزات من المكافأة موجودة. المنطقة السقيفية البطنية تدعم تطوير التعلم والتحسيس وتطلق الدوپامين في الدماغ الأمامي.[89] تقوم هذه الخلايا العصبية أيضًا بإسقاط وإطلاق الدوپامين في النواة المتكئة،[90] من خلال المسار الوسطي الطرفي. تعمل جميع الأدوية التي تسبب إدمان المخدرات تقريبًا على زيادة إفراز الدوپامين في المسار الوسطي الطرفي،[91]بالإضافة إلى تأثيراتها المحددة.

- النواة المتكئة (NAcc) هي أحد مخرجات اسقاطات المنطقة السقيفية البطنية. تتكون النواة المتكئة نفسها بشكل أساسي من الخلايا العصبية الشوكية المتوسطة الگابايرجيك (MSNs).[92] ترتبط النواة المتكئة باكتساب واستنباط السلوكيات المشروطة، وتشارك في زيادة الحساسية للمخدرات مع تقدم الإدمان.[89] يعتبر الإفراط في التعبير عن ΔFosB في النواة المتكئة عاملاً مشتركًا ضروريًا في جميع أشكال الإدمان المعروفة;[3] ΔFosB هو معدل إيجابي قوي للسلوكيات المعززة بشكل إيجابي.[3]

- قشرة الفص الجبهي، بما في ذلك القشرة الحزامية الأمامية والقشرة الحجاجية الجبهية،[93] هما ناتج المنطقة السقيفية البطنية آخر في مسار القشرة الوسطية الطرفية. هو مهم لتكامل المعلومات التي تساعد على تحديد ما إذا كان سيتم استنباط السلوك.[94] كما أنه ضروري لتكوين روابط بين تجربة المكافأة لتعاطي المخدرات والإلماعات في البيئة. الأهم من ذلك، أن هذه الإلماعات هي وسطاء أقوياء لسلوك البحث عن المخدرات ويمكن أن تؤدي إلى الانتكاس حتى بعد شهور أو سنوات من التوقف.[95]

تشمل هياكل الدماغ الأخرى التي تشارك في الإدمان ما يلي:

- اللوزة الجانبية القاعدية تسقط في النواة المتكئة ويعتقد أنها مهمة أيضًا للتحفيز.[94]

- يتدخل الحصين في إدمان المخدرات، لما له من دور في التعلم والذاكرة. تنبع الكثير من هذه الأدلة من التقصي التي أظهرت أن التلاعب بالخلايا في الحُصين يغير مستويات الدوپامين في النواة المتكئة ومعدلات إطلاق خلايا الدوبامين القشرة الوسطية الطرفية.[90]

دور الدوپامين والگلوتامات

الدوپامين هو الناقل العصبي الأساسي لنظام المكافأة في الدماغ. يلعب دورًا في تنظيم الحركة والعاطفة والإدراك والتحفيز ومشاعر المتعة.[96] تتسبب المكافآت الطبيعية، مثل الأكل، وكذلك تعاطي العقاقير الترويحي في إفراز الدوپامين، وترتبط بالطبيعة المعززة لهذه المنبهات.[96][97] تعمل جميع العقاقير المسببة للإدمان تقريبًا، بشكل مباشر أو غير مباشر، على نظام المكافأة في الدماغ عن طريق زيادة نشاط الدوپامين.[98]

يؤدي الإفراط في تناول العديد من أنواع العقاقير المسببة للإدمان إلى إطلاق متكرر لكميات كبيرة من الدوپامين، والذي بدوره يؤثر على مسار المكافأة مباشرة من خلال تنشيط مستقبلات الدوپامين. يمكن أن تؤدي المستويات الطويلة والمرتفعة بشكل غير طبيعي من الدوپامين في الشق المشبكي إلى تقليل تنظيم المستقبلات في المسار العصبي. يمكن أن يؤدي تقليل تنظيم مستقبلات الدوپامين الوسطية الطرفية إلى انخفاض في الحساسية تجاه المعززات الطبيعية.[96]

سلوك البحث عن العقاقير ناتج عن الإسقاطات الگلوتاماتية من قشرة الفص قبل الجبهي إلى النواة المتكئة. يتم دعم هذه الفكرة ببيانات من التجارب التي تُظهر أنه يمكن منع سلوك البحث عن العقاقير بعد تثبيط مستقبلات الگلوتامات AMPA وإطلاق الگلوتامات في النواة المتكئة.[93]

تحسس المكافأة

| الجين المستهدف | التعبير الجيني المستهدف | التأثير العصبي | التأثير السلوكي |

|---|---|---|---|

| c-Fos | ↓ | التبديل الجزيئي يمكن حث ΔFosB المزمن[note 3] | – |

| دينورفين | ↓ [note 4] |

• تقليل تنظيم حلقة التغذية الراجعة لمستقبلات لمواد الأفيونية | • زيادة مكافأة الدواء |

| NF-κB | ↑ | • التسوع في الزوائد التغصنية للنواة المتكئة • NF-κB الاستجابة الالتهابية في النواة المتكئة • NF-κB الاستجابة الالتهابية في البطامة المذنبة |

• زيادة مكافأة الدواء • زيادة مكافأة الدواء • التحسس الحركي |

| GluR2 | ↑ | • انخفاض تحسس للگلوتامات | • زيادة مكافأة الدواء |

| Cdk5 | ↑ | • فسفرة البروتين التشابك GluR1 • التسوع في الزوائد التغصنية للنواة المتكئة |

انخفاض مكافأة الدواء (التأثير الكلي) |

تحسس المكافأة هي عملية تؤدي إلى زيادة مقدار المكافأة (على وجه التحديد، بروز الحافز[note 5]) التي يخصصها الدماغ لمنبه تكافئي (على سبيل المثال، دواء). بعبارات بسيطة، عندما يحدث تحسس المكافأة لمنبه معين (على سبيل المثال، دواء)، تزداد "رغبة" الفرد أو رغبته في التحفيز نفسه والإلماعات المرتبطة به.[101][100][102] عادةً ما يحدث التحسس بشأن المكافأة بعد مستويات عالية مزمنة من التعرض للمنبهات. لقد ثبت أن تعبير ΔFosB (دلتاFosB) في الخلايا العصبية الشوكية المتوسطة من النوع D1 في النواة المتكئة ينظم بشكل مباشر وإيجابي تحسس المكافأة الذي يشمل الأدوية والمكافآت الطبيعية.[3][69][70]

"الإلماع الناتج عن الانتظار" أو "الإلماع المستحثة بالإشارة"، وهي شكل من أشكال الرغبة التي تحدث في الإدمان، هي المسؤولة عن معظم السلوك القهري الذي يظهره الأشخاص المصابون بالإدمان.[100][102] أثناء تطور الإدمان، يؤدي الارتباط المتكرر للمنبهات المحايدة وغير المكافأة مع استهلاك المخدرات إلى عملية تعلم ترابطية تجعل هذه المحفزات المحايدة سابقًا تعمل كمعززات إيجابية مشروطة لتعاطي المخدرات (أي، تبدأ هذه المحفزات في تعمل كإلمعات للمخدرات).[100][103][102] بصفتها معززات إيجابية مشروطة لتعاطي المخدرات، يتم تعيين هذه المحفزات المحايدة سابقًا كدافع مهم (والذي يتجلى في الرغبة الشديدة) - في بعض الأحيان عند مستويات عالية مرضيًا بسبب حساسية المكافأة - التي يمكن أن تنتقل إلى المعزز الأساسي (على سبيل المثال، استخدام عقار مسبب للإدمان) الذي تم إقرانه به في الأصل.[100][103][102]

تشير الأبحاث حول التفاعل بين المكافآت الطبيعية والمكافآت الدوائية إلى أن المنشطات النفسية للدوپامين (مثل الأمفيتامين ) والسلوك الجنسي يعملوا على آليات جزيئية حيوية مماثلة لتحفيز ΔFosB في النواة المتكئة وتمتلك تأثير تحسس متبادل للمكافأة[note 6] يتم التوسط من خلاله ΔFosB.[33][36][37] على النقيض من تأثير تحسس المكافأة الخاص بـ ΔFosB، فإن نشاط النسخ CREB (بروتين رابط عنصر الاستجابة أدينوزين احادي الفوسفات الحلقي) يقلل من حساسية المستخدم لتأثيرات المكافأة للمادة. يتورط نسخ الروتين CREB في النواة المتكئة في الاعتماد النفسي والأعراض التي تنطوي على قلة المتعة أو الدافع أثناء التوقف عن تعاطي المخدرات.[3][88][99]

إن مجموعة البروتينات المعروفة باسم " منظمات إطلاق اشارات البروتين G " (RGS)، وخاصة RGS4 و RGS9-2، قد شاركت في تعديل بعض أشكال التحسس الأفيوني، بما في ذلك تحسس المكافأة.[104]

| شكل اللدونة العصبية أو اللدونة السلوكية |

نوع المُعزز | المصادر | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| الأفيونيات | المنبهات النفسية | الأغذية الغنية بالدهون أو السكريات | الجماع الجنسي | التمرينات الرياضية (الهوائية) |

التعزيز البيئي | ||

| تعبير ΔFosB في النويات المكتئة D1-type MSNs |

↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | [33] |

| اللدونة السلوكية | |||||||

| زيادة الجرعة | نعم | نعم | نعم | [33] | |||

| الوعي-المتبادل للمنبه النفسي |

نعم | غير قابل للتطبيق | نعم | نعم | ضعيفة | ضعيفة | [33] |

| المنبه النفسي الإدارة الذاتية |

↑ | ↑ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | [33] | |

| المنبه النفسي التفضيل المكاني المشروط |

↑ | ↑ | ↓ | ↑ | ↓ | ↑ | [33] |

| إعادة سلوك البحث عن المخدرات | ↑ | ↑ | ↓ | ↓ | [33] | ||

| اللدونة الكيميائية-العصبية | |||||||

| فسفرة CREB في النوية المتكئة |

↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | [33] | |

| استجابة الدوپامين في النوية المتكئة |

لا | نعم | لا | نعم | [33] | ||

| تاشير الدوپامين في الجسم المخطط | ↓DRD2, ↑DRD3 | ↑DRD1, ↓DRD2, ↑DRD3 | ↑DRD1, ↓DRD2, ↑DRD3 | ↑DRD2 | ↑DRD2 | [33] | |

| التأشير الشبه أفيوني الداخلي المتغير | لا يوجد تغير أو ↑μ-مستقبلات أفيونية |

↑μ ↑κ-مستقبلات أفيونية |

↑μ-مستقبلات أفيونية | ↑μ-مستقبلات أفيونية | لا يوجد تغير | لا يوجد تغير | [33] |

| تغيرات في الپپتيدات الشبه أفيونية في الجسم المخطط | ↑دينورفين لا يوجد تغير: إنكفالين |

↑دينورفين | ↓إنكفالين | ↑دينورفين | ↑دينورفين | [33] | |

| اللدونة التشابكية للمسار الوسطي الطرفي | |||||||

| عددالزوائد الشجرية في النوية المتكئة | ↓ | ↑ | ↑ | [33] | |||

| كثافة الشوكة التغصنية في النوية المتكئة |

↓ | ↑ | ↑ | [33] | |||

آليات التخلق العصبي

يلعب التنظيم التخلقي المتغير للتعبير الجيني داخل نظام المكافأة في الدماغ دورًا مهمًا ومعقدًا في تطوير إدمان المخدرات.[82][105] ترتبط العقاقير المسببة للإدمان بثلاثة أنواع من التعديلات التخلقية داخل الخلايا العصبية.[82] هما (1) تعديلات الهيستون، (2) المثيلة التخلقية للحمض النووي في مواقع ثنائي النوكليوتيد CpG عند (أو مجاورة) لجينات معينة، و (3) نقص التنظيم أو زيادة التنظيم التخلقي للـحمض نووي ريبوزي ميكروي الذي له جينات مستهدفة معينة.[82][34][105] على سبيل المثال، في حين أن مئات الجينات في خلايا النواة المتكئة (NAc) تظهر تعديلات على الهيستون بعد التعرض للعقار - لا سيما حالات الأستلة المتغيرة وحالات المثيلة لبقايا الهيستون[105] – فإن معظم الجينات الأخرى في الخلايا المتكئة لا تظهر مثل هذا التغييرات.[82]

التشخيص

يستخدم الإصدار الخامس من الدليل التشخيصي والإحصائي للاضطرابات النفسية (DSM-5) مصطلح " اضطراب تعاطي المخدرات (العقاقير)" للإشارة إلى مجموعة من الاضطرابات المرتبطة بتعاطي المخدرات. يزيل الدليل التشخيصي والإحصائي للاضطرابات النفسية (DSM-5) مصطلحات " سوء الاستخدام " و "الاعتماد" من فئات التشخيص، بدلاً من استخدام محددات معتدلة ومتوسطة وشديدة للإشارة إلى مدى الاستخدام المضطرب. يتم تحديد هذه المحددات من خلال عدد معايير التشخيص الموجودة في حالة معينة. في الدليل التشخيصي والإحصائي للاضطرابات النفسية DSM-5، يعتبر مصطلح إدمان المخدرات مرادفًا لاضطراب تعاطي المخدرات الشديد.[1][2]

قدمت DSM-5 فئة تشخيصية جديدة للإدمان السلوكي ؛ ومع ذلك، فإن إدمان القمار هي الحالة الوحيدة المتضمنة في هذه الفئة في الإصدار الخامس.[19] تم إدراج اضطراب الألعاب عبر الإنترنت على أنه "حالة تتطلب مزيدًا من الدراسة" في الدليل التشخيصي والإحصائي للاضطرابات النفسية (DSM-5).[106]

استخدمت الإصدارات السابقة الاعتماد الجسدي ومتلازمة الانسحاب المصاحبة لتحديد حالة الإدمان. يحدث الاعتماد الجسدي عندما يتكيف الجسم عن طريق دمج المادة في وظيفتها "الطبيعية" - أي تصل إلى الاستتباب - وبالتالي تحدث أعراض الانسحاب الجسدي عند التوقف عن الاستخدام.[107] التحمل هو العملية التي من خلالها يتكيف الجسم باستمرار مع المادة ويتطلب كميات أكبر بشكل متزايد لتحقيق التأثيرات الأصلية. يشير الانسحاب إلى الأعراض الجسدية والنفسية التي تحدث عند تقليل أو التوقف عن مادة أصبح الجسم يعتمد عليها. تشمل أعراض الانسحاب عمومًا على سبيل المثال لا الحصر آلام الجسم والقلق والتهيجية والرغبة الشديدة في تناول المادة والغثيان والهلوسة والصداع والتعرق البارد والرعشة والاختلاج

انتقد الباحثون الطبيون الذين يدرسون الإدمان بنشاط تصنيف DSM للإدمان لكونه معيبًا ويتضمن معايير تشخيصية تعسفية.[20] في عام 2013، ناقش مدير المعهد الوطني الأمريكي للصحة العقلية والنفسية عدم صلاحية تصنيف DSM-5 للاضطرابات النفسية:[108]

بينما تم وصف الدليل التشخيصي والإحصائي DSM بأنه "كتاب مقدس" للمجال، فإنه في أفضل الأحوال قاموس، يقوم بإنشاء مجموعة من الملصقات وتحديد كل منها. كانت قوة كل إصدار من إصدارات DSM هي "الموثوقية" - فقد ضمنت كل نسخة أن الأطباء يستخدمون المصطلحات نفسها بنفس الطرق. الضعف هو نقص صلاحيتها على عكس تعريفاتنا لأمراض القلب الإقفارية، أو سرطان الغدد الليمفاوية، أو الإيدز، فإن تشخيصات الدليل التشخيصي والإحصائي للاضطرابات النفسية (DSM) تستند إلى إجماع حول مجموعات من الأعراض السريرية، وليس أي إجراء معملي موضوعي. في بقية الطب، سيكون هذا معادلاً لإنشاء أنظمة تشخيص بناءً على طبيعة ألم الصدر أو نوع الحمى.

بالنظر إلى أن الإدمان يتجلى في التغييرات الهيكلية للدماغ، فمن الممكن استخدام فحوصات التصوير العصبي غير الغازية التي تم الحصول عليها عن طريق التصوير بالرنين المغناطيسي للمساعدة في تشخيص الإدمان في المستقبل.[109] كمؤشر بيولوجي تشخيصي، يمكن استخدام تعبير ΔFosB لتشخيص الإدمان لدى البشر، لكن هذا يتطلب خزعة من المخ، وبالتالي لا يتم استخدامه في الممارسة السريرية

العلاج

وفقًا لمراجعة، "من أجل أن تكون فعالة، يجب دمج جميع العلاجات الدوائية أو البيولوجية للإدمان في أشكال أخرى من إعادة التأهيل من الإدمان، مثل العلاج السلوكي المعرفي، والعلاج النفسي الفردي والجماعي، واستراتيجيات تعديل السلوك و برنامج الاثنتي عشرة خطوة والمرافق العلاجية السكنية".[8]

يبرز النهج الاجتماعي الحيوي لعلاج الإدمان المحددات الاجتماعية للمرض والرفاهية ويأخذ في الاعتبار العلاقات الديناميكية والمتبادلة الموجودة لتجربة الفرد والتأثير عليها.[110]

يهدف عمل (AV Schlosser (2018 إلى اعلان التجارب الفردية التي تعيشها النساء اللائي يتلقين العلاج بمساعدة الأدوية (على سبيل المثال، الميثادون، النالتريكسون، البوربرينورفين) في بيئة إعادة التأهيل طويلة الأجل، من خلال تحقيق إثنوغرافي ميداني لمدة عشرين شهرًا. يُظهر هذا البحث الذي يركز على الفرد كيف أن تجارب هؤلاء النساء "تنبثق من أنظمة عدم المساواة المستقرة القائمة على التهميش الجنسي والعرقي والطبقي المتداخل مع عمليات العمل الداخلي".[111]

إن مشاهدة علاج الإدمان من خلال هذه العدسة يسلط الضوء أيضًا على أهمية تأطير المشتركين أجسادهم على أنها "جسد اجتماعي". كما يشير شلوسر (2018)، فإن "اجساد المشتركين" وكذلك "الخبرات المتجسدة للانتماء الذاتي والاجتماعي تظهر في ومن خلال الهياكل والزمان والتوقعات الخاصة بمركز العلاج."[111]

المزيد من التحديات والتوترات المتجسدة لديها القدرة على الظهور كنتيجة للديناميكيات المتأصلة في العلاقة بين المريض ومقدم الخدمة، بالإضافة إلى تجربة "العزلة عن أجسادهم ونفسهم وحياتهم الاجتماعية عند تخديرهم بالأدوية أثناء العلاج"."[111]

تشكل التقنيات الحيوية حاليًا جزءًا كبيرًا من العلاجات المستقبلية للإدمان. على سبيل المثال لا الحصر، تحفيز الدماغ العميق والغرسات الناهضة / المناهضة واللقاحات المقترنة. تتداخل التطعيمات ضد الإدمان على وجه التحديد مع الاعتقاد بأن الذاكرة تلعب دورًا كبيرًا في الآثار الضارة للإدمان والانتكاسات. تم تصميم لقاحات الناشبة المقترنة لمنع المستقبلات الأفيونية في منطقة واحدة، مع السماح للمستقبلات الأخرى بالتصرف بشكل طبيعي. بشكل أساسي، بمجرد عدم إمكانية تحقيق النشوة فيما يتعلق بحدث صادم، يمكن فصل العلاقة بين الأدوية والذاكرة المؤلمة ويمكن أن يلعب العلاج دورًا في العلاج.[112]

العلاج السلوكي

وجدت مراجعة تحليلية تلوية حول فعالية العلاجات السلوكية المختلفة لعلاج الإدمان على المخدرات والسلوك أن العلاج السلوكي المعرفي (على سبيل المثال، منع الانتكاس ومعالجة الطوارئ )، والمقابلات التحفيزية، ونهج التعزيز المجتمعي كانت تدخلات فعالة بأحجام تأثير معتدلة.[113]

تشير الأدلة السريرية وما قبل السريرية إلى أن التمارين الهوائية المتسقة، وخاصة تمارين التحمل (على سبيل المثال، الجري الماراثون )، تمنع بالفعل تطور بعض إدمان المخدرات وهي علاج مساعد فعال لإدمان المخدرات، ولإدمان المنبهات النفسية على وجه الخصوص.[33][114][115][116][117] تمرينات الأيروبيك المتناغمة التي تعتمد على الحجم (أي حسب المدة والشدة) تقلل من خطر إدمان المخدرات، والذي يبدو أنه يحدث من خلال عكس اللدونة العصبية المرتبطة بالإدمان الناجم عن المخدرات.[33][115] وأشارت أحد المراجعات أن التمرينات الرياضية قد تمنع تطور إدمان المخدرات عن طريق تغيير التفاعلية المناعية لكل من ΔFosB أو c-Fos في الجسم المخطط أو أجزاء أخرى من نظام المكافأة.[117] التمارين الرياضية تقلل الاعطاء الذاتي للمخدرات، وتقلل من احتمالات الانتكاس، وتحث علي تأثيرات معاكسة على إشارات مستقبلات الدوبامين D2 في الجسم المخطط (DRD2) (زيادة كثافة DRD2) لتلك التي يسببها الإدمان على العديد من فئات الأدوية (انخفاض كثافة DRD2).[33][115] وبالتالي، قد تؤدي التمارين الهوائية المتناغمة إلى نتائج علاجية أفضل عند استخدامها كعلاج مساعد لإدمان المخدرات.[33][115][116]

أدوية

إدمان الكحول

يمكن للكحول، مثل المواد الأفيونية، أن يسبب حالة شديدة من الاعتماد الجسدي وينتج عنه أعراض انسحاب مثل الهذيان الارتعاشي. لهذا السبب، عادةً ما يتضمن علاج إدمان الكحول نهجًا مشتركًا للتعامل مع الاعتماد والإدمان في وقت واحد. البنزوديازيبينات لديها أكبر وأفضل قاعدة دليل في علاج انسحاب الكحول وتعتبر المعيار الذهبي لإزالة سمية الكحول.[118]

تشمل العلاجات الدوائية لإدمان الكحول عقاقير مثل النالتريكسون (مضادات الأفيون) و ديسلفيرام و أكامبروسيت و توبيراميت.[119][120] بدلاً من استبدال الكحول، تهدف هذه الأدوية إلى التأثير على الرغبة في الشرب، إما عن طريق الحد مباشرة من الرغبة الشديدة كما هو الحال مع أكامبروسيت وتوبيراميت، أو عن طريق إحداث تأثيرات غير سارة عند تناول الكحول، كما هو الحال مع ديسفلفرام. يمكن أن تكون هذه الأدوية فعالة إذا استمر العلاج، ولكن الامتثال يمكن أن يكون مشكلة حيث غالبًا ما ينسى مرضى الكحول تناول أدويتهم أو التوقف عن استخدامها بسبب الآثار الجانبية المفرطة.[121][122] وفقًا لمراجعة مؤسسة كوكرين، فقد ثبت أن مضاد الأفيون النالتريكسون هو علاج فعال لإدمان الكحول، حيث تدوم آثاره من ثلاثة إلى اثني عشر شهرًا بعد نهاية العلاج.[123]

الإدمانات السلوكية

إدمان القنب

اعتبارا من 2010[تحديث]،لا توجد تدخلات دوائية فعالة لإدمان القنب.[124] لاحظت مراجعة 2013 حول إدمان القنب أن تطوير ناهضات مستقبلات CB1 التي قللت من التفاعل مع إشاراتβ-arrestin 2 قد يكون مفيدًا علاجيًا.[125]

إدمان النيكوتين

المجال الآخر الذي تم فيه استخدام العلاج الدوائي على نطاق واسع هو علاج إدمان النيكوتين، والذي يتضمن عادةً استخدام معالجة النيكوتين بالإعاضة، أو مضادات مستقبلات النيكوتين، أو ناهضات جزئية لمستقبل النيكوتين.[126][127] من الأمثلة على الأدوية التي تعمل على مستقبلات النيكوتين والتي تم استخدامها في علاج إدمان النيكوتين مضادات مثل البوبروبيون ومضاد الفارينيكلين الجزئي.[126][127]

إدمان الأفيون

تسبب المواد الأفيونية الاعتماد الجسدي، وعادة ما يعالج العلاج كلا من الاعتماد والإدمان.

يتم علاج الاعتماد الجسدي باستخدام أدوية بديلة مثل سوبوكسون أو سوبوتكس (كلاهما يحتوي على المكونات النشطة البوپرنورفين ) والميثادون.[128][129] على الرغم من أن هذه الأدوية تديم الاعتماد الجسدي، فإن الهدف من استمرار الأفيون هو توفير قدر من السيطرة على كل من الألم والرغبة الشديدة. يزيد استخدام الأدوية البديلة من قدرة الفرد المدمن على العمل بشكل طبيعي ويزيل العواقب السلبية للحصول على المواد الخاضعة للرقابة بشكل غير مشروع. بمجرد استقرار الجرعة الموصوفة، يدخل العلاج في مراحل المداومة أو التناقص التدريجي. في الولايات المتحدة، يتم تنظيم العلاج ببدائل الأفيون بإحكام في عيادات الميثادون وبموجب تشريع DATA 2000. في بعض البلدان، تُستخدم المشتقات الأفيونية الأخرى مثل ثنائي هيدرو كودين،[130] ثنائي هيدرو إيتورفين[131] وحتى الهيروين[132][133] كعقاقير بديلة للمواد الأفيونية غير المشروعة في الشوارع، مع إعطاء وصفات مختلفة اعتمادًا على احتياجات المريض الفردية. أدى استخدام باكلوفين إلى تقليل الرغبة الشديدة في تناول المنشطات والكحول والمواد الأفيونية، كما أنه يخفف أيضًا من متلازمة انسحاب الكحول. صرح العديد من المرضى أنهم "أصبحوا غير مبالين بالكحول" أو "غير مبالين بالكوكايين" بين عشية وضحاها بعد بدء العلاج بالباكلوفين.[134] تظهر بعض الدراسات الترابط بين إزالة سمية العقاقير الأفيونية والوفيات بجرعات زائدة.[135]

إدمان المحفزات النفسية

اعتبارا من May 2014[تحديث]، لا يوجد علاج دوائي فعال لأي شكل من أشكال إدمان المنبهات النفسية.[8][136][137][138] أشارت المراجعات من 2015 و 2016 و 2018 إلى أن الناهضات الانتقائية TAAR1 لها إمكانات علاجية كبيرة كعلاج لإدمان المنبهات النفسية[139][140][141] ومع ذلك، اعتبارا من 2018[تحديث]، فإن المركبات الوحيدة المعروفة بأنها تعمل كمنبهات انتقائية TAAR1 هي عقاقير تجريبية.[139][140][141]

بحث

This section requires expansion. (April 2016) |

تشير الأبحاث إلى أن اللقاحات التي تستخدم الأجسام المضادة وحيدة النسيلة المضادة للأدوية يمكن أن تخفف من التعزيز الإيجابي الذي يسببه الدواء عن طريق منع الدواء من التحرك عبر الحاجز الدموي الدماغي;[142] ومع ذلك، فإن العلاجات الحالية القائمة على اللقاح فعالة فقط في مجموعة فرعية صغيرة نسبيًا من الأفراد.[142][143] اعتبارا من November 2015[تحديث]، يتم اختبار العلاجات القائمة على اللقاحات في التجارب السريرية البشرية كعلاج للإدمان وتدبير وقائي ضد الجرعات الزائدة من المخدرات التي تشمل النيكوتين والكوكايين والميثامفيتامين.[142]

تظهر الدراسة الجديدة أن اللقاح قد ينقذ الأرواح أيضًا أثناء تناول جرعة زائدة من المخدرات. في هذه الحالة، الفكرة هي أن الجسم سيستجيب للقاح عن طريق إنتاج الأجسام المضادة بسرعة لمنع المواد الأفيونية من الوصول إلى الدماغ.[144]

نظرًا لأن الإدمان يتضمن شذوذًا في الگلوتامات والناقل العصبي الجابايرجيك،[145][146] المستقبلات المرتبطة بهذه النواقل العصبية (على سبيل المثال، مستقبلات AMPA، مستقبلات ن-مثيل-د-أسبارتات، و مستقبلات GABA B ) هي أهداف علاجية محتملة للإدمان.[145][146][147][148] أظهر N-أسيتيل سيستئين، الذي يؤثر على مستقبلات الگلوتامات الاستقلابية ومستقبلات NMDA، بعض الفوائد في الدراسات قبل السريرية والسريرية التي تنطوي على إدمان الكوكايين والهيروين والقنب.[145] قد يكون مفيدًا أيضًا كعلاج مساعد للإدمان على المنبهات من نوع الأمفيتامين، ولكن يلزم إجراء المزيد من الأبحاث السريرية.[145]

حددت المراجعات الطبية الحالية للبحوث التي تشمل حيوانات المختبر فئة الأدوية - مثبطات هيستون ديستيلاز من الفئة الأولي[note 7] التي تثبط الوظيفة بشكل غير مباشر وتزيد من التعبير عن ΔFosB المتراكم عن طريق تحفيز تعبير G9a في النواة المتكئة بعد الاستخدام المطول.[70][82][149][105] تشير هذه المراجعات والأدلة الأولية اللاحقة التي استخدمت عن طريق الفم أو الإعطاء داخل الصفاق لملح الصوديوم لحمض الزبد أو مثبطاتHDAC من الفئة 1 أخري لفترة طويلة إلى أن هذه الأدوية لها فعالية في الحد من السلوك الإدماني في حيوانات المختبر[note 8]التي تم تطويرها الإدمان على الإيثانول والمنشطات النفسية (مثل الأمفيتامين والكوكايين) والنيكوتين والمواد الأفيونية;[82][105][150][151] ومع ذلك، فقد تم إجراء عدد قليل من التجارب السريرية على البشر الذين يعانون من الإدمان وأي من مثبطات HDAC من الفئة الأولى لاختبار فعالية العلاج لدى البشر أو تحديد نظام الجرعات الأمثل.[note 9]

العلاج الجيني للإدمان مجال بحث نشط. يتضمن أحد خطوط أبحاث العلاج الجيني استخدام ناقلات فيروسية لزيادة التعبير عن بروتينات مستقبل الدوبامين D2 في الدماغ.[153][154][155][156][157]

علم الأوبئة

بسبب الاختلافات الثقافية، فإن نسبة الأفراد الذين يطورون إدمانًا لعقار أو سلوكي خلال فترة زمنية محددة (أي الانتشار ) يختلف بمرور الوقت، حسب البلد، وعبر الديموغرافية السكانية الوطنية (على سبيل المثال، حسب الفئة العمرية، والوضع الاجتماعي والاقتصادي، إلخ. ).[41]

آسيا

انتشار الإعتماد علي الكحول ليس مرتفعا كما هو ملاحظ في مناطق أخرى. في آسيا، لا تؤثر العوامل الاجتماعية والاقتصادية فحسب، بل العوامل البيولوجية أيضًا على سلوك الشرب.[158]

تبلغ نسبة انتشار ملكية الهواتف الذكية 62٪، وتتراوح من 41٪ في الصين إلى 84٪ في كوريا الجنوبية. علاوة على ذلك، تتراوح المشاركة في الألعاب عبر الإنترنت من 11٪ في الصين إلى 39٪ في اليابان. يوجد في هونغ كونغ أكبر عدد من المراهقين الذين يبلغون عن استخدام الإنترنت يوميًا أو أعلى (68٪). يعد اضطراب إدمان الإنترنت في أعلى مستوياته في الفلبين، وفقًا لكل من IAT (اختبار إدمان الإنترنت) - 5٪ و CIAS-R (مقياس تشن المعدل لإدمان الإنترنت) - 21٪.[159]

أستراليا

تم الإبلاغ عن انتشار اضطراب تعاطي المخدرات بين الأستراليين بنسبة 5.1٪ في عام 2009.[160]

أوروبا

في عام 2015، كان معدل الانتشار المقدر بين السكان البالغين 18.4٪ لتعاطي الكحول بصورة نوباتية بكثرة (في الثلاثين يومًا الماضية) ؛ 15.2٪ تدخين التبغ اليومي ؛ و 3.8 و 0.77 و 0.37 و 0.35 في المائة في عام 2017 القنب والأمفيتامين والمواد الأفيونية وتعاطي الكوكايين. كانت معدلات الوفيات بسبب الكحول والعقاقير غير المشروعة أعلى في أوروبا الشرقية.[161]

الولايات المتحدة

استنادًا إلى عينات تمثيلية لسكان الشباب في الولايات المتحدة في عام 2011، قُدِّر معدل انتشار متوسط الحياة[note 10] بحوالي 8٪ و 2-3٪ على التوالي.[25] بناءً على عينات تمثيلية من السكان البالغين في الولايات المتحدة في عام 2011، تم تقدير معدل انتشار لمدة 12 شهرًا لإدمان الكحول والمخدرات بحوالي 12 ٪ و 2-3 ٪ على التوالي.[25] يبلغ معدل انتشار إدمان العقار الموصوف حاليًا حوالي 4.7٪.[162]

اعتبارا من 2016[تحديث] يحتاج حوالي 22 مليون شخص في الولايات المتحدة إلى علاج من إدمان الكحول أو النيكوتين أو غيره من العقاقير.[26][163] فقط حوالي 10٪، أو ما يزيد قليلاً عن 2 مليون، يتلقون أي شكل من أشكال العلاج، وأولئك الذين لا يتلقون بشكل عام رعاية مبنية على الأدلة.[26][163] ثلث تكاليف المستشفيات الداخلية و 20٪ من جميع الوفيات في الولايات المتحدة كل عام ناتجة عن الإدمان غير المعالج وتعاطي المخدرات المحفوف بالمخاطر.[26][163] على الرغم من التكلفة الاقتصادية الإجمالية الهائلة التي يتحملها المجتمع، والتي تفوق تكلفة مرض السكري وجميع أشكال السرطان مجتمعة، فإن معظم الأطباء في الولايات المتحدة يفتقرون إلى التدريب اللازم للتعامل مع إدمان المخدرات بشكل فعال.[26][163]

أدرجت مراجعة أخرى تقديرات لمعدلات الانتشار مدى الحياة للعديد من الإدمان السلوكي في الولايات المتحدة، بما في ذلك 1-2٪ للمقامرة القهرية، و 5٪ للإدمان الجنسي، و 2.8٪ لإدمان الطعام، و5-6٪ للتسوق الإجباري.[33] أشارت مراجعة منهجية إلى أن معدل الانتشار الثابت للوقت للإدمان الجنسي والسلوك الجنسي القهري ذي الصلة (على سبيل المثال، الاستمناء القهري مع المواد الإباحية أو بدونها، والجنس السيبراني القهري، وما إلى ذلك) داخل الولايات المتحدة يتراوح من 3 إلى 6 ٪ من السكان.[35]

وفقًا لاستطلاع أجراه مركز بيو للأبحاث عام 2017، فإن ما يقرب من نصف البالغين الأمريكيين يعرفون أحد أفراد العائلة أو صديقًا مقربًا يعاني من إدمان المخدرات في مرحلة ما من حياتهم.[164]

في عام 2019، تم الاعتراف بإدمان المواد الأفيونية كأزمة وطنية في الولايات المتحدة.[165] ذكر مقال في صحيفة واشنطن پوست أن "أكبر شركات الأدوية الأمريكية أغرقت البلاد بأقراص الألم من عام 2006 حتى عام 2012، حتى عندما أصبح من الواضح أنها كانت تغذي الإدمان والجرعات الزائدة".

جنوب أمريكا

قد تكون حقائق استخدام المواد الأفيونية المفعول وإساءة استخدامها في أمريكا اللاتينية خادعة إذا اقتصرت الملاحظات على النتائج الوبائية. في تقرير مكتب الأمم المتحدة المعني بالمخدرات والجريمة،[166] على الرغم من أن أمريكا الجنوبية تنتج 3٪ من المورفين والهيروين في العالم و 0.01٪ من الأفيون، إلا أن انتشار الاستخدام غير متكافئ. وفقًا للجنة البلدان الأمريكية لمكافحة تعاطي المخدرات، فإن استهلاك الهيروين منخفض في معظم بلدان أمريكا اللاتينية، على الرغم من أن كولومبيا هي أكبر منتج للأفيون في المنطقة. المكسيك، بسبب حدودها مع الولايات المتحدة، لديها أعلى معدل استخدام.[167]

النظريات الشخصية

نظريات الشخصية للإدمان هي نماذج نفسية تربط سمات الشخصية أو أنماط التفكير (أي الحالات العاطفية ) بميل الفرد لتطوير الإدمان. يوضح تحليل البيانات أن هناك اختلافًا كبيرًا في الملامح النفسية لمتعاطي المخدرات وغير المتعاطين وقد يكون الاستعداد النفسي لاستخدام الأدوية المختلفة مختلفًا.[168] تتضمن نماذج مخاطر الإدمان التي تم اقتراحها في منشورات علم النفس نموذجًا يؤثر على خلل التنظيم للعاطفة للتأثيرات الوجدانية الإيجابية والسلبية، ونموذج نظرية حساسية التعزيز للاندفاع والتثبيط السلوكي، ونموذج الاندفاع لحساسية المكافأة والاندفاع.[169][170][171][172][173]

اللواحق "-holic" و "-holism"

في اللغة الإنجليزية الحديثة المعاصرة "-holic" هي لاحقة يمكن إضافتها إلى موضوع للإشارة إلى إدمان عليه. تم استخراجه من كلمة إدمان الكحول (واحدة من أولى أنواع الإدمان التي تم تحديدها على نطاق واسع من الناحيتين الطبية والاجتماعية) (بشكل صحيح الجذر " wikt: alcohol " بالإضافة إلى اللاحقة "-ism") عن طريق تقسيمها أو إعادة أقواسها إلى "alco" و " - holism ". (هناك خطأ آخر هو تفسير " الهليكوبتر " على أنها "heli-copter" بدلاً من "helico-pter" الصحيح اشتقاقيًا، مما أدى إلى ظهور كلمات مشتقة مثل " heliport.[174]) هناك مصطلحات طبية وقانونية صحيحة لمثل هذه الإدمان: هوس الشراب هو المصطلح الطبي القانوني للكحولية;[175] أمثلة أخرى في هذا الجدول:

| مصطلح عام | مدمن ل | المصطلح القانوني الطبي |

|---|---|---|

| ادمان الرقص | رقص | هوس الرقص |

| مدمن عمل | عمل | مهوس بالعمل |

| مدمن للجنس | جنس | هوس شبقي، شباق، الشهوة |

| مدمن للسكريات | سكر | هوس سكري |

| مدمن للشوكولاتة | شوكولاتة | |

| مدمن للغضب | غيظ / غضب |

مرئيات

| شم الكوكايين حسن فايق. |

انظر ايضاً

الهوامش

- ^ According to a review of experimental animal models that examined the transgenerational epigenetic inheritance of epigenetic marks that occur in addiction, alterations in histone acetylation – specifically, di-acetylation of lysine residues 9 and 14 on histone 3 (i.e., H3K9ac2 and H3K14ac2) in association with BDNF gene promoters – have been shown to occur within the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC), testes, and sperm of cocaine-addicted male rats.[41] These epigenetic alterations in the rat mPFC result in increased BDNF gene expression within the mPFC, which in turn blunts the rewarding properties of cocaine and reduces cocaine self-administration.[41] The male but not female offspring of these cocaine-exposed rats inherited both epigenetic marks (i.e., di-acetylation of lysine residues 9 and 14 on histone 3) within mPFC neurons, the corresponding increase in BDNF expression within mPFC neurons, and the behavioral phenotype associated with these effects (i.e., a reduction in cocaine reward, resulting in reduced cocaine-seeking by these male offspring).[41] Consequently, the transmission of these two cocaine-induced epigenetic alterations (i.e., H3K9ac2 and H3K14ac2) in rats from male fathers to male offspring served to reduce the offspring's risk of developing an addiction to cocaine.[41] اعتبارا من 2018[تحديث] neither the heritability of these epigenetic marks in humans nor the behavioral effects of the marks within human mPFC neurons has been established.[41]

- ^ أ ب A decrease in aversion sensitivity, in simpler terms, means that an individual's behavior is less likely to be influenced by undesirable outcomes.

- ^ In other words, c-Fos repression allows ΔFosB to more rapidly accumulate within the D1-type medium spiny neurons of the nucleus accumbens because it is selectively induced in this state.[3] Prior to c-Fos repression, all Fos family proteins (e.g., c-Fos, Fra1, Fra2, FosB, and ΔFosB) are induced together, with ΔFosB expression increasing to a lesser extent.[3]

- ^ According to two medical reviews, ΔFosB has been implicated in causing both increases and decreases in dynorphin expression in different studies;[69][99] this table entry reflects only a decrease.

- ^ Incentive salience, the "motivational salience" for a reward, is a "desire" or "want" attribute, which includes a motivational component, that the brain assigns to a rewarding stimulus.[100][101] As a consequence, incentive salience acts as a motivational "magnet" for a rewarding stimulus that commands attention, induces approach, and causes the rewarding stimulus to be sought out.[100]

- ^ In simplest terms, this means that when either amphetamine or sex is perceived as more alluring or desirable through reward sensitization, this effect occurs with the other as well.

- ^ Inhibitors of class I histone deacetylase (HDAC) enzymes are drugs that inhibit four specific histone-modifying enzymes: HDAC1, HDAC2, HDAC3, and HDAC8. Most of the animal research with HDAC inhibitors has been conducted with four drugs: butyrate salts (mainly sodium butyrate), trichostatin A, valproic acid, and SAHA;[149][105] butyric acid is a naturally occurring short-chain fatty acid in humans, while the latter two compounds are FDA-approved drugs with medical indications unrelated to addiction.

- ^ Specifically, prolonged administration of a class I HDAC inhibitor appears to reduce an animal's motivation to acquire and use an addictive drug without affecting an animals motivation to attain other rewards (i.e., it does not appear to cause motivational anhedonia) and reduce the amount of the drug that is self-administered when it is readily available.[82][105][150]

- ^ Among the few clinical trials that employed a class I HDAC inhibitor, one utilized valproate for methamphetamine addiction.[152]

- ^ The lifetime prevalence of an addiction is the percentage of individuals in a population that developed an addiction at some point in their life.

- مفتاح الصور

- ^ (Text color) Transcription factors

المصادر

- ^ أ ب "Facing Addiction in America: The Surgeon General's Report on Alcohol, Drugs, and Health" (PDF). Office of the Surgeon General. US Department of Health and Human Services. November 2016. pp. 35–37, 45, 63, 155, 317, 338. Retrieved 28 January 2017.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Volkow ND, Koob GF, McLellan AT (January 2016). "Neurobiologic Advances from the Brain Disease Model of Addiction". N. Engl. J. Med. 374 (4): 363–371. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1511480. PMID 26816013.

Substance-use disorder: A diagnostic term in the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) referring to recurrent use of alcohol or other drugs that causes clinically and functionally significant impairment, such as health problems, disability, and failure to meet major responsibilities at work, school, or home. Depending on the level of severity, this disorder is classified as mild, moderate, or severe.

Addiction: A term used to indicate the most severe, chronic stage of substance-use disorder, in which there is a substantial loss of self-control, as indicated by compulsive drug taking despite the desire to stop taking the drug. In the DSM-5, the term addiction is synonymous with the classification of severe substance-use disorder. - ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د ذ ر ز س ش ص ض ط ظ ع غ ف ق Nestler EJ (December 2013). "Cellular basis of memory for addiction". Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 15 (4): 431–443. PMC 3898681. PMID 24459410.

Despite the importance of numerous psychosocial factors, at its core, drug addiction involves a biological process: the ability of repeated exposure to a drug of abuse to induce changes in a vulnerable brain that drive the compulsive seeking and taking of drugs, and loss of control over drug use, that define a state of addiction. ... A large body of literature has demonstrated that such ΔFosB induction in D1-type [nucleus accumbens] neurons increases an animal's sensitivity to drug as well as natural rewards and promotes drug self-administration, presumably through a process of positive reinforcement ... Another ΔFosB target is cFos: as ΔFosB accumulates with repeated drug exposure it represses c-Fos and contributes to the molecular switch whereby ΔFosB is selectively induced in the chronic drug-treated state.41. ... Moreover, there is increasing evidence that, despite a range of genetic risks for addiction across the population, exposure to sufficiently high doses of a drug for long periods of time can transform someone who has relatively lower genetic loading into an addict.

- ^

{{cite book}}: Empty citation (help) - ^ أ ب "Glossary of Terms". Mount Sinai School of Medicine. Department of Neuroscience. Retrieved 9 February 2015.

- ^ Angres DH, Bettinardi-Angres K (October 2008). "The disease of addiction: origins, treatment, and recovery". Disease-a-Month. 54 (10): 696–721. doi:10.1016/j.disamonth.2008.07.002. PMID 18790142.

- ^ أ ب Malenka RC, Nestler EJ, Hyman SE (2009). "Chapter 15: Reinforcement and Addictive Disorders". In Sydor A, Brown RY (eds.). Molecular Neuropharmacology: A Foundation for Clinical Neuroscience (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. pp. 364–65, 375. ISBN 978-0-07-148127-4.

The defining feature of addiction is compulsive, out-of-control drug use, despite negative consequences. ...

compulsive eating, shopping, gambling, and sex – so-called "natural addictions" – Indeed, addiction to both drugs and behavioral rewards may arise from similar dysregulation of the mesolimbic dopamine system. - ^ أ ب ت Taylor SB, Lewis CR, Olive MF (February 2013). "The neurocircuitry of illicit psychostimulant addiction: acute and chronic effects in humans". Subst. Abuse Rehabil. 4: 29–43. doi:10.2147/SAR.S39684. PMC 3931688. PMID 24648786.

Initial drug use can be attributed to the ability of the drug to act as a reward (ie, a pleasurable emotional state or positive reinforcer), which can lead to repeated drug use and dependence.8,9 A great deal of research has focused on the molecular and neuroanatomical mechanisms of the initial rewarding or reinforcing effect of drugs of abuse. ... At present, no pharmacological therapy has been approved by the FDA to treat psychostimulant addiction. Many drugs have been tested, but none have shown conclusive efficacy with tolerable side effects in humans.172 ... A new emphasis on larger-scale biomarker, genetic, and epigenetic research focused on the molecular targets of mental disorders has been recently advocated.212 In addition, the integration of cognitive and behavioral modification of circuit-wide neuroplasticity (ie, computer-based training to enhance executive function) may prove to be an effective adjunct-treatment approach for addiction, particularly when combined with cognitive enhancers.198,213–216 Furthermore, in order to be effective, all pharmacological or biologically based treatments for addiction need to be integrated into other established forms of addiction rehabilitation, such as cognitive behavioral therapy, individual and group psychotherapy, behavior-modification strategies, twelve-step programs, and residential treatment facilities.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ أ ب ت ث "Drugs, Brains, and Behavior: The Science of Addiction – Drug Misuse and Addiction". www.drugabuse.gov. North Bethesda, Maryland: National Institute on Drug Abuse. 13 July 2020. Retrieved 23 December 2021.

- ^ Hammer R, Dingel M, Ostergren J, Partridge B, McCormick J, Koenig BA (2013-07-01). "Addiction: Current Criticism of the Brain Disease Paradigm". AJOB Neuroscience. 4 (3): 27–32. doi:10.1080/21507740.2013.796328. PMC 3969751. PMID 24693488.

- ^ Heather N, Best D, Kawalek A, Field M, Lewis M, Rotgers F, Wiers RW, Heim D (2018-07-04). "Challenging the brain disease model of addiction: European launch of the addiction theory network". Addiction Research & Theory (in الإنجليزية). 26 (4): 249–255. doi:10.1080/16066359.2017.1399659.

- ^ Heather N (2017-04-01). "Q: Is Addiction a Brain Disease or a Moral Failing? A: Neither". Neuroethics. 10 (1): 115–124. doi:10.1007/s12152-016-9289-0. PMC 5486515. PMID 28725283.

- ^ Satel S, Lilienfeld SO (2014). "Addiction and the brain-disease fallacy". Frontiers in Psychiatry (in الإنجليزية). 4: 141. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2013.00141. PMC 3939769. PMID 24624096.

- ^ Peele S (December 2016). "People Control Their Addictions: No matter how much the "chronic" brain disease model of addiction indicates otherwise, we know that people can quit addictions - with special reference to harm reduction and mindfulness". Addictive Behaviors Reports. 4: 97–101. doi:10.1016/j.abrep.2016.05.003. PMC 5836519. PMID 29511729.

- ^ Henden E (2017). "Addiction, Compulsion, and Weakness of the Will: A Dual-Process Perspective.". In Heather N, Gabriel S (eds.). Addiction and Choice: Rethinking the Relationship. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. pp. 116–132.

- ^ Morse RM, Flavin DK (August 1992). "The definition of alcoholism. The Joint Committee of the National Council on Alcoholism and Drug Dependence and the American Society of Addiction Medicine to Study the Definition and Criteria for the Diagnosis of Alcoholism". JAMA. 268 (8): 1012–14. doi:10.1001/jama.1992.03490080086030. PMID 1501306.

- ^ Marlatt GA, Baer JS, Donovan DM, Kivlahan DR (1988). "Addictive behaviors: etiology and treatment". Annu Rev Psychol. 39: 223–52. doi:10.1146/annurev.ps.39.020188.001255. PMID 3278676.

- ^ ME (2019-09-12). "Gaming Addiction in ICD-11: Issues and Implications". Psychiatric Times (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2020-03-03.

- ^ أ ب American Psychiatric Association (2013). "Substance-Related and Addictive Disorders" (PDF). American Psychiatric Publishing. pp. 1–2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 August 2015. Retrieved 10 July 2015.

Additionally, the diagnosis of dependence caused much confusion. Most people link dependence with "addiction" when in fact dependence can be a normal body response to a substance.

- ^ أ ب Malenka RC, Nestler EJ, Hyman SE, Holtzman DM (2015). "Chapter 16: Reinforcement and Addictive Disorders". Molecular Neuropharmacology: A Foundation for Clinical Neuroscience (3rd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. ISBN 978-0-07-182770-6.

The official diagnosis of drug addiction by the Diagnostic and Statistic Manual of Mental Disorders (2013), which uses the term substance use disorder, is flawed. Criteria used to make the diagnosis of substance use disorders include tolerance and somatic dependence/withdrawal, even though these processes are not integral to addiction as noted. It is ironic and unfortunate that the manual still avoids use of the term addiction as an official diagnosis, even though addiction provides the best description of the clinical syndrome.

- ^ أ ب Rosenthal, Richard; Faris, Suzanne (2019). "The etymology and early history of 'addiction'". Addiction Research & Theory. 27 (5): 437. doi:10.1080/16066359.2018.1543412. S2CID 150418396.

- ^ Institute of Medicine (1996). Pathways of Addiction: Opportunities in Drug Abuse Research. Washington: National Academies Press.

- ^ Bettinardi-Angres, Kathy; Angres, Daniel (2015). "Understanding the Disease of Addiction". Journal of Nursing Regulation. 1 (2): 31–37. doi:10.1016/S2155-8256(15)30348-3.

- ^ أ ب Malenka RC, Nestler EJ, Hyman SE (2009). "Chapter 1: Basic Principles of Neuropharmacology". In Sydor A, Brown RY (eds.). Molecular Neuropharmacology: A Foundation for Clinical Neuroscience (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-07-148127-4.

Drug abuse and addiction exact an astoundingly high financial and human toll on society through direct adverse effects, such as lung cancer and hepatic cirrhosis, and indirect adverse effects –for example, accidents and AIDS – on health and productivity.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Merikangas KR, McClair VL (June 2012). "Epidemiology of Substance Use Disorders". Hum. Genet. 131 (6): 779–89. doi:10.1007/s00439-012-1168-0. PMC 4408274. PMID 22543841.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ "American Board of Medical Specialties recognizes the new subspecialty of addiction medicine" (PDF). American Board of Addiction Medicine. 14 March 2016. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 March 2021. Retrieved 3 April 2016.

Sixteen percent of the non-institutionalized U.S. population age 12 and over – more than 40 million Americans – meets medical criteria for addiction involving nicotine, alcohol or other drugs. This is more than the number of Americans with cancer, diabetes or heart conditions. In 2014, 22.5 million people in the United States needed treatment for addiction involving alcohol or drugs other than nicotine, but only 11.6 percent received any form of inpatient, residential, or outpatient treatment. Of those who do receive treatment, few receive evidence-based care. (There is no information available on how many individuals receive treatment for addiction involving nicotine.)

Risky substance use and untreated addiction account for one-third of inpatient hospital costs and 20 percent of all deaths in the United States each year, and cause or contribute to more than 100 other conditions requiring medical care, as well as vehicular crashes, other fatal and non-fatal injuries, overdose deaths, suicides, homicides, domestic discord, the highest incarceration rate in the world and many other costly social consequences. The economic cost to society is greater than the cost of diabetes and all cancers combined. Despite these startling statistics on the prevalence and costs of addiction, few physicians have been trained to prevent or treat it. - ^ "Economic consequences of drug abuse" (PDF). International Narcotics Control Board Report: 2013 (PDF). United Nations – International Narcotics Control Board. 2013. ISBN 978-92-1-148274-4. Retrieved 28 September 2018.

- ^ "Overdose Death Rates". National Institute on Drug Abuse. 9 August 2018. Retrieved 17 September 2018.

- ^ "Overdose Deaths Accelerating During Covid-19". Centers For Disease Control Prevention. 18 December 2020. Retrieved 10 February 2021.

- ^ Washburn DA (2016). "The Stroop effect at 80: The competition between stimulus control and cognitive control". J Exp Anal Behav. 105 (1): 3–13. doi:10.1002/jeab.194. PMID 26781048.

Today, arguably more than at any time in history, the constructs of attention, executive functioning, and cognitive control seem to be pervasive and preeminent in research and theory. Even within the cognitive framework, however, there has long been an understanding that behavior is multiply determined, and that many responses are relatively automatic, unattended, contention-scheduled, and habitual. Indeed, the cognitive flexibility, response inhibition, and self-regulation that appear to be hallmarks of cognitive control are noteworthy only in contrast to responses that are relatively rigid, associative, and involuntary.

- ^ Diamond A (2013). "Executive functions". Annu Rev Psychol. 64: 135–68. doi:10.1146/annurev-psych-113011-143750. PMC 4084861. PMID 23020641.

Core EFs are inhibition [response inhibition (self-control – resisting temptations and resisting acting impulsively) and interference control (selective attention and cognitive inhibition)], working memory, and cognitive flexibility (including creatively thinking "outside the box," seeing anything from different perspectives, and quickly and flexibly adapting to changed circumstances). ... EFs and prefrontal cortex are the first to suffer, and suffer disproportionately, if something is not right in your life. They suffer first, and most, if you are stressed (Arnsten 1998, Liston et al. 2009, Oaten & Cheng 2005), sad (Hirt et al. 2008, von Hecker & Meiser 2005), lonely (Baumeister et al. 2002, Cacioppo & Patrick 2008, Campbell et al. 2006, Tun et al. 2012), sleep deprived (Barnes et al. 2012, Huang et al. 2007), or not physically fit (Best 2010, Chaddock et al. 2011, Hillman et al. 2008). Any of these can cause you to appear to have a disorder of EFs, such as ADHD, when you do not. You can see the deleterious effects of stress, sadness, loneliness, and lack of physical health or fitness at the physiological and neuroanatomical level in prefrontal cortex and at the behavioral level in worse EFs (poorer reasoning and problem solving, forgetting things, and impaired ability to exercise discipline and self-control). ...

EFs can be improved (Diamond & Lee 2011, Klingberg 2010). ... At any age across the life cycle EFs can be improved, including in the elderly and in infants. There has been much work with excellent results on improving EFs in the elderly by improving physical fitness (Erickson & Kramer 2009, Voss et al. 2011) ... Inhibitory control (one of the core EFs) involves being able to control one's attention, behavior, thoughts, and/or emotions to override a strong internal predisposition or external lure, and instead do what's more appropriate or needed. Without inhibitory control we would be at the mercy of impulses, old habits of thought or action (conditioned responses), and/or stimuli in the environment that pull us this way or that. Thus, inhibitory control makes it possible for us to change and for us to choose how we react and how we behave rather than being unthinking creatures of habit. It doesn't make it easy. Indeed, we usually are creatures of habit and our behavior is under the control of environmental stimuli far more than we usually realize, but having the ability to exercise inhibitory control creates the possibility of change and choice. ... The subthalamic nucleus appears to play a critical role in preventing such impulsive or premature responding (Frank 2006). - ^ أ ب Malenka RC, Nestler EJ, Hyman SE (2009). "Chapter 13: Higher Cognitive Function and Behavioral Control". In Sydor A, Brown RY (eds.). Molecular Neuropharmacology: A Foundation for Clinical Neuroscience (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. pp. 313–21. ISBN 978-0-07-148127-4.

• Executive function, the cognitive control of behavior, depends on the prefrontal cortex, which is highly developed in higher primates and especially humans.

• Working memory is a short-term, capacity-limited cognitive buffer that stores information and permits its manipulation to guide decision-making and behavior. ...

These diverse inputs and back projections to both cortical and subcortical structures put the prefrontal cortex in a position to exert what is often called "top-down" control or cognitive control of behavior. ... The prefrontal cortex receives inputs not only from other cortical regions, including association cortex, but also, via the thalamus, inputs from subcortical structures subserving emotion and motivation, such as the amygdala (Chapter 14) and ventral striatum (or nucleus accumbens; Chapter 15). ...

In conditions in which prepotent responses tend to dominate behavior, such as in drug addiction, where drug cues can elicit drug seeking (Chapter 15), or in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD; described below), significant negative consequences can result. ... ADHD can be conceptualized as a disorder of executive function; specifically, ADHD is characterized by reduced ability to exert and maintain cognitive control of behavior. Compared with healthy individuals, those with ADHD have diminished ability to suppress inappropriate prepotent responses to stimuli (impaired response inhibition) and diminished ability to inhibit responses to irrelevant stimuli (impaired interference suppression). ... Functional neuroimaging in humans demonstrates activation of the prefrontal cortex and caudate nucleus (part of the striatum) in tasks that demand inhibitory control of behavior. Subjects with ADHD exhibit less activation of the medial prefrontal cortex than healthy controls even when they succeed in such tasks and utilize different circuits. ... Early results with structural MRI show thinning of the cerebral cortex in ADHD subjects compared with age-matched controls in prefrontal cortex and posterior parietal cortex, areas involved in working memory and attention. - ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د ذ ر ز س ش ص ض ط ظ ع غ ف ق ك ل م ن هـ و ي أأ أب أت أث أج أح أخ أد أذ أر Olsen CM (December 2011). "Natural rewards, neuroplasticity, and non-drug addictions". Neuropharmacology. 61 (7): 1109–22. doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.03.010. PMC 3139704. PMID 21459101.

Functional neuroimaging studies in humans have shown that gambling (Breiter et al, 2001), shopping (Knutson et al, 2007), orgasm (Komisaruk et al, 2004), playing video games (Koepp et al, 1998; Hoeft et al, 2008) and the sight of appetizing food (Wang et al, 2004a) activate many of the same brain regions (i.e., the mesocorticolimbic system and extended amygdala) as drugs of abuse (Volkow et al, 2004). ... Cross-sensitization is also bidirectional, as a history of amphetamine administration facilitates sexual behavior and enhances the associated increase in NAc DA ... As described for food reward, sexual experience can also lead to activation of plasticity-related signaling cascades. The transcription factor delta FosB is increased in the NAc, PFC, dorsal striatum, and VTA following repeated sexual behavior (Wallace et al., 2008; Pitchers et al., 2010b). This natural increase in delta FosB or viral overexpression of delta FosB within the NAc modulates sexual performance, and NAc blockade of delta FosB attenuates this behavior (Hedges et al, 2009; Pitchers et al., 2010b). Further, viral overexpression of delta FosB enhances the conditioned place preference for an environment paired with sexual experience (Hedges et al., 2009). ... In some people, there is a transition from "normal" to compulsive engagement in natural rewards (such as food or sex), a condition that some have termed behavioral or non-drug addictions (Holden, 2001; Grant et al., 2006a). ... In humans, the role of dopamine signaling in incentive-sensitization processes has recently been highlighted by the observation of a dopamine dysregulation syndrome in some patients taking dopaminergic drugs. This syndrome is characterized by a medication-induced increase in (or compulsive) engagement in non-drug rewards such as gambling, shopping, or sex (Evans et al, 2006; Aiken, 2007; Lader, 2008)."

Table 1: Summary of plasticity observed following exposure to drug or natural reinforcers" - ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د ذ ر ز س ش Robison AJ, Nestler EJ (November 2011). "Transcriptional and epigenetic mechanisms of addiction". Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 12 (11): 623–37. doi:10.1038/nrn3111. PMC 3272277. PMID 21989194.

ΔFosB has been linked directly to several addiction-related behaviors ... Importantly, genetic or viral overexpression of ΔJunD, a dominant negative mutant of JunD which antagonizes ΔFosB- and other AP-1-mediated transcriptional activity, in the NAc or OFC blocks these key effects of drug exposure14,22–24. This indicates that ΔFosB is both necessary and sufficient for many of the changes wrought in the brain by chronic drug exposure. ΔFosB is also induced in D1-type NAc MSNs by chronic consumption of several natural rewards, including sucrose, high fat food, sex, wheel running, where it promotes that consumption14,26–30. This implicates ΔFosB in the regulation of natural rewards under normal conditions and perhaps during pathological addictive-like states.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Karila L, Wéry A, Weinstein A, Cottencin O, Petit A, Reynaud M, Billieux J (2014). "Sexual addiction or hypersexual disorder: different terms for the same problem? A review of the literature". Curr. Pharm. Des. 20 (25): 4012–20. doi:10.2174/13816128113199990619. PMID 24001295.

Sexual addiction, which is also known as hypersexual disorder, has largely been ignored by psychiatrists, even though the condition causes serious psychosocial problems for many people. A lack of empirical evidence on sexual addiction is the result of the disease's complete absence from versions of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. ... Existing prevalence rates of sexual addiction-related disorders range from 3% to 6%. Sexual addiction/hypersexual disorder is used as an umbrella construct to encompass various types of problematic behaviors, including excessive masturbation, cybersex, pornography use, sexual behavior with consenting adults, telephone sex, strip club visitation, and other behaviors. The adverse consequences of sexual addiction are similar to the consequences of other addictive disorders. Addictive, somatic and psychiatric disorders coexist with sexual addiction. In recent years, research on sexual addiction has proliferated, and screening instruments have increasingly been developed to diagnose or quantify sexual addiction disorders. In our systematic review of the existing measures, 22 questionnaires were identified. As with other behavioral addictions, the appropriate treatment of sexual addiction should combine pharmacological and psychological approaches.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج Pitchers KK, Vialou V, Nestler EJ, Laviolette SR, Lehman MN, Coolen LM (February 2013). "Natural and drug rewards act on common neural plasticity mechanisms with ΔFosB as a key mediator". The Journal of Neuroscience. 33 (8): 3434–42. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4881-12.2013. PMC 3865508. PMID 23426671.

Drugs of abuse induce neuroplasticity in the natural reward pathway, specifically the nucleus accumbens (NAc), thereby causing development and expression of addictive behavior. ... Together, these findings demonstrate that drugs of abuse and natural reward behaviors act on common molecular and cellular mechanisms of plasticity that control vulnerability to drug addiction, and that this increased vulnerability is mediated by ΔFosB and its downstream transcriptional targets. ... Sexual behavior is highly rewarding (Tenk et al., 2009), and sexual experience causes sensitized drug-related behaviors, including cross-sensitization to amphetamine (Amph)-induced locomotor activity (Bradley and Meisel, 2001; Pitchers et al., 2010a) and enhanced Amph reward (Pitchers et al., 2010a). Moreover, sexual experience induces neural plasticity in the NAc similar to that induced by psychostimulant exposure, including increased dendritic spine density (Meisel and Mullins, 2006; Pitchers et al., 2010a), altered glutamate receptor trafficking, and decreased synaptic strength in prefrontal cortex-responding NAc shell neurons (Pitchers et al., 2012). Finally, periods of abstinence from sexual experience were found to be critical for enhanced Amph reward, NAc spinogenesis (Pitchers et al., 2010a), and glutamate receptor trafficking (Pitchers et al., 2012). These findings suggest that natural and drug reward experiences share common mechanisms of neural plasticity

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج Beloate LN, Weems PW, Casey GR, Webb IC, Coolen LM (February 2016). "Nucleus accumbens NMDA receptor activation regulates amphetamine cross-sensitization and deltaFosB expression following sexual experience in male rats". Neuropharmacology. 101: 154–64. doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2015.09.023. PMID 26391065. S2CID 25317397.

- ^ Nehlig A (2004). Coffee, tea, chocolate, and the brain. Boca Raton: CRC Press. pp. 203–218. ISBN 9780429211928.

- ^ Meule A, Gearhardt AN (September 2014). "Food addiction in the light of DSM-5". Nutrients. 6 (9): 3653–71. doi:10.3390/nu6093653. PMC 4179181. PMID 25230209.

- ^ أ ب خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةBehavioral addictions - ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د ذ ر ز س ش ص ض ط Vassoler FM, Sadri-Vakili G (2014). "Mechanisms of transgenerational inheritance of addictive-like behaviors". Neuroscience. 264: 198–206. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2013.07.064. PMC 3872494. PMID 23920159.

However, the components that are responsible for the heritability of characteristics that make an individual more susceptible to drug addiction in humans remain largely unknown given that patterns of inheritance cannot be explained by simple genetic mechanisms (Cloninger et al., 1981; Schuckit et al., 1972). The environment also plays a large role in the development of addiction as evidenced by great societal variability in drug use patterns between countries and across time (UNODC, 2012). Therefore, both genetics and the environment contribute to an individual's vulnerability to become addicted following an initial exposure to drugs of abuse. ...

The evidence presented here demonstrates that rapid environmental adaptation occurs following exposure to a number of stimuli. Epigenetic mechanisms represent the key components by which the environment can influence genetics, and they provide the missing link between genetic heritability and environmental influences on the behavioral and physiological phenotypes of the offspring. - ^ Mayfield, R D; Harris, R A; Schuckit, M A (May 2008). "Genetic factors influencing alcohol dependence: Genetic factors and alcohol dependence". British Journal of Pharmacology. 154 (2): 275–287. doi:10.1038/bjp.2008.88. PMC 2442454. PMID 18362899.

- ^ أ ب Kendler KS, Neale MC, Heath AC, Kessler RC, Eaves LJ (May 1994). "A twin-family study of alcoholism in women". Am J Psychiatry. 151 (5): 707–15. doi:10.1176/ajp.151.5.707. PMID 8166312.