خاقانية الأويغور

خاقانية الاويغور (امبراطورية الاويغور) 𐱃𐰆𐰴𐰕:𐰆𐰍𐰕:𐰉𐰆𐰑𐰣 Toquz Oγuz budun | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 744–840 | |||||||||||||||

Territory of the Uyghur Khaganate (745-850), and main contemporary polities in continental Asia.[1] | |||||||||||||||

| الوضع | Khaganate (Nomadic empire) | ||||||||||||||

| العاصمة |

| ||||||||||||||

| اللغات المشتركة | |||||||||||||||

| الدين |

| ||||||||||||||

| الحكومة | Monarchy | ||||||||||||||

| Khagan | |||||||||||||||

• 744–747 | Qutlugh Bilge Köl (first) | ||||||||||||||

• 841–847 | Enian Qaghan (last) | ||||||||||||||

| التاريخ | |||||||||||||||

• تأسست | 744 | ||||||||||||||

• انحلت | 840 | ||||||||||||||

| المساحة | |||||||||||||||

| 800[3][4] | 5،200،000 km2 (2،000،000 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

خاقانية الاويغور أو امبراطورية الاويغور أو بلد تقوز اُغوز Toquz Oghuz (بالاويغورية: ئورخۇن ئۇيغۇر خانلىقى ؛ بالصينية: 回纥 / 回鶻) كانت امبراطورية توركية [5] استمرت نحو قرن من الزمان بين منتصفي القرن الثامن والتاسع الميلاديين. وكانت اتحاداً قبلياً بقيادة نبلاء اويغور اُورخون (回鶻)، الذين يشار إليهم بالصينية بإسم جيو شينگ ("القبائل التسع")، وهي ترجمة للاسم تقوز اُغوز Toquz Oghuz.

التاريخ

بزوغ الأويغور في منغوليا

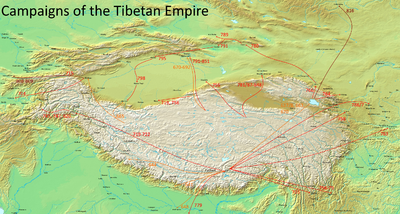

In 657, the Western Turkic Khaganate was defeated by the Tang dynasty, after which the Uyghurs defected to the Tang. Prior to this the Uyghurs had already shown an inclination towards alliances with the Tang when they fought with them against the Tibetan Empire and Turks in 627.[6][7]

ترك تمرد في عام 742 ضد خاقانية گوكتورك، من قبائل الاويغور والكارلوك والباسميل فراغاً هائلاً في منغوليا وآسيا الوسطى.

In 744, the Basmyls captured the Turk capital of Ötüken and killed the reigning Özmiş Khagan. Later that year, a Uyghur-Karluk alliance formed against the Basmyls and defeated them. Their khagan was killed, and the Basmyls ceased to exist as a people. Hostilities between the Uyghurs and Karluks then forced the Karluks to migrate west into Zhetysu and conflict with the Türgesh, whom they defeated and conquered in 766.[8]

The Uyghur khagan's personal name was Qullığ Boyla (الصينية: 骨力裴羅). He took the title Kutlug Bilge Kol Khagan (Glorious, wise, mighty khagan), claiming to be the supreme ruler of all the tribes. He built his capital at Ordu-Baliq. According to Chinese sources, the territory of the Uyghur Empire then reached "on its eastern extremity, the territory of Shiwei, on the west the Altai Mountains, on the south it controlled the Gobi Desert, so it covered the entire territory of the ancient Xiongnu".[9]

In 745, the Uyghurs killed the last khagan of the Göktürks, Báiméikèhán Gǔlǒngfú (白眉可汗 鶻隴匐), and sent his head to the Tang.[10]

التركيبة القبلية

Tang Huiyao, vol. 98, listed nine Toquz Oghuz surname tribes (姓部 xìngbù); another list of tribes (部落 bùluò) was recorded in the Old Book of Tang and the New Book of Tang. According to Japanese scholars Hashimoto, Katayama, and Senga, each name in the lists in the Books of Tang recorded each subtribal surname of each chief, while the other list in Tang Huiyao recorded the names of the Toquz Oghuz tribes proper.[11][12] Walter Bruno Henning (1938)[13] linked nine names recorded in the Saka language "Staël-Holstein Scroll" with those recorded by Han Chinese authors.

| Tribal name in Chinese | Tribal name in Saka | Tribal name in Old Turkic | Surname in Old Turkic | Surname in Saka | Surname in Chinese |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Huihe 迴紇 | Uyğur 𐰺𐰍𐰖𐰆 | 𐰖𐰍𐰞𐰴𐰺 Yağlaqar | Yahīdakari | 藥羅葛 Yaoluoge | |

| Pugu 僕固 | Bākū | *Buqu[t] | *(H)Uturqar | 胡咄葛 Huduoge | |

| Hun 渾 | *Qun | *Kürebir | Kurabīri | 咄羅勿 Guluowu | |

| Bayegu 拔曳固 | Bayarkāta | Bayırku | *Boqsıqıt | Bāsikātti | 貊歌息訖 Mogexiqi |

| Tongluo 同羅 | Ttaugara | Tongra | *Avučağ | 阿勿嘀 A-Wudi | |

| Sijie 思結 | Sīkari | *Sıqar | *Qasar | 葛薩 Gesa | |

| Qibi 契苾 | Kāribari | 斛嗢素 Huwasu | |||

| A-Busi 阿布思 | *Yabutqar | Yabūttikari | 藥勿葛 Yaowuge | ||

| Gulunwugu(si) 骨倫屋骨(思)[أ] | *(Q)Ayabir | Ayabīri | 奚耶勿 Xiyawu |

- ملاحظات

- ^ Tang Huiyao manuscript[14] has 骨崙屋骨恐; Ulrich Theobald (2012) amended 恐 (kong) to 思 (si) & proposed that 屋骨思 transcribed Oğuz[15]

العصر الذهبي

In 747, Qutlugh Bilge Köl Kaghan died, leaving his youngest son, Bayanchur Khan to reign as Khagan El etmish bilge "State settled, wise". After building a number of trading outposts with the Tang, Bayanchur Khan used the profits to construct the capital, Ordu-Baliq, and another city further up the Selenga River, Bai Baliq. The new khagan then embarked on a series of campaigns to bring all the steppe peoples under his banner. During this time the Empire expanded rapidly and brought the Sekiz Oghuz, Kyrgyz, Karluks, Turgesh, Toquz Tatars, Chiks and the remnants of the Basmyls under Uyghur rule.

In 751, the Tang Empire suffered a strategic defeat against the Arabs at the Battle of Talas. After that, the Tang retreated from Central Asia, allowing the Uyghur to emerge as the new dominant power.[16]

In 755 An Lushan instigated a rebellion against the Tang dynasty and Emperor Suzong of Tang turned to Bayanchur Khan for assistance in 756. The khagan agreed and ordered his eldest son to provide military service to the Tang emperor. Approximately 4,000 Uyghur horsemen assisted Tang armies in retaking Chang'an and Luoyang in 757. After the battle at Luoyang the Uyghurs looted the city for three days and only stopped after large quantities of silk were extracted. For their aid, the Tang sent 20,000 rolls of silk and bestowed them with honorary titles. In addition the horse trade was fixed at 40 rolls of silk for every horse and Uyghurs were given "guest" status while staying in Tang China.[17][18] The Tang and Uyghurs conducted an exchange marriage. Bayanchur Khan married Princess Ninguo while a Uyghur princess was married to a Tang prince.[10] The Uyghur Khaganate exchanged princesses in marriage with Tang dynasty China in 756 to seal the alliance against An Lushan. The Uyghur Khagan Bayanchur Khan had his daughter Uyghur Princess Pijia (毗伽公主) married to Tang dynasty Chinese Prince Li Chengcai (李承采), Prince of Dunhuang (敦煌王李承采), son of Li Shouli, Prince of Bin. while the Tang dynasty Chinese princess Ningguo 寧國公主, daughter of Emperor Suzong, married Uyghur Khagan Bayanchur.

In 758, the Uyghurs turned their attention to the northern Yenisei Kyrgyz. Bayanchur Khan destroyed several of their trading outposts before slaughtering a Kyrgyz army and executing their Khan.[18]

On the ren-shen day of the fifth month of the first year of the Qianyuan reign [on March 29, 758 CE], The envoys from Hui-he [Uyghur Khanate], Duo-yi-hai-a-bo and others, totaling eighty people, and an emir from the Black-robed Dashi [Abbasid Caliphate], Nao-wen and others, totaling eight people, come at the same time to pay a visit [to the Tang court]; when they walk to the side entrance of the palace, [both delegations] argue who should be the first [to see the Emperor]. The interpreters and palace secretaries arrange them as left team and right team, and enter through the Eastern Gate and the Western Gate all at once. [After this,] Wen-she-shi and the Black-robed Dashi envoy pay their visit [to the Chinese Emperor].[19]

In 759 the Uyghurs attempted to assist the Tang in stamping out the rebels but failed. Bayanchur Khan died and his son Tengri Bögü succeeded him as Khagan Qutlugh Tarkhan sengün.[18]

في 762، في تحالف مع أسرة تانگ، شن تنگري بوگو حملة ضد التبتيين. وقد استعاد لامبراطور تانگ العاصمة الغربية تشانگآن. وفي احدى حملاته، التقى الخاقان تنگري بوگو بكهنة مانويين من إيران، واعتنق المانوية واتخذها الدين الرسمي للخاقانية الاويغورية.[20]

في 779 خطط تنگري بوگو، بإيعاز من التجار السوگديين المقيمين في اوردو بالق، غزواً للصين منتهزاً فرصة اعتلاء امبراطور جديد. عارض عم تنگري بوگو، تون بغا طرخان تلك الخطة، خوفاً من ذوبان الاويغور في الثقافة الصينية[بحاجة لمصدر]. قاد بغا طرخان تمرداً ناجحاً ضد ابن أخيه الحاكم، وجز رأسه ورؤوس نحو 2,000 من النبلاء. ارتقى تون بغا طرخان العرش متخذاً الاسم الملكي ألپ قتلغ بيلگه ("المنتصر، المجيد، الحكيم") وسن مجموعة قوانين جديدة، صممها لتأمين وحدة الخاقانية. كما حرك جيوشه ضد القيرغيز، مرة أخرى، ليخضعهم أخيراً لسيطرة الخاقانية الاويغورية.

الانحدار

In 779, Tengri Bögü planned to invade the Tang dynasty based on the advice of his Sogdian courtiers. However, Tengri Bögü's uncle, Tun Baga Tarkhan, opposed this plan and killed him and "nearly two thousand people from among the kaghan's family, his clique and the Sogdians."[21] Tun Bagha Tarkhan ascended the throne, with the title Alp Qutlugh Bilge "Victorious, glorious, wise", and enforced a new set of laws, which he designed to secure the unity of the khaganate. During his reign, Manichaeism was suppressed, but his successors restored it as the official religion.[22]

In 780, a group of Uyghurs and Sogdians was killed while leaving Chang'an with tribute. Tun demanded 1,800,000 strings of cash in compensation and the Tang agreed to pay this amount in gold and silk.[23] In 789, Tun Bagha Tarkhan died and his son succeeded him as Külüg Qaghan. The Karluks took this opportunity to encroach on Uyghur territory and annexed Futu Valley.[24] In 790, the Uyghurs and Tang forces were defeated by Tibetan Empire at Tingzhou (Beshbalik).[7] Külüg Qaghan died, and his son, A-ch'o, succeeded him as Qutluq Bilge Qaghan.

In 791, the Tibetans attacked Lingzhou but were driven off by the Uyghurs, who presented captured prisoners and cattle to Emperor Dezong of Tang. The Tibetans and Karluks suffered another defeat against the Uyghurs at Beiting. The captured Tibetan general Zan Rgyal sum was sent to Dezong.[25] In 792, the Uyghurs, led by Baoyi Qaghan, defeated the Tibetans and Karluks, taking Gaochang. Not long after the Tibetans attacked Yushu, a fortified town 560 li east of Kucha. They were besieged by Baoyi there and destroyed.[26] In 795, Qutluq Bilge Qaghan died and the Yaghlakar dynasty came to an end. A general, Qutluq II, declared himself the new qaghan under the title Ay Tängridä ülüg bulmïsh alp qutlugh ulugh bilgä qaghan "Greatly born in moon heaven, victorious, glorious, great and wise qaghan",[17] founding a new dynasty, the Ädiz (الصينية: 阿跌氏).

In 803, the Uyghurs captured Qocho.[27] In 808, Qutluq II died and his son, Baoyi, succeeded him. In the same year, the Uyghurs seized Liang Province from the Tibetans.[28] In 816, a Tibetan raid reached within two days' journey of the Uyghur capital, Ordu-Baliq.[29] In 821, Baoyi Qaghan died, and his son, Chongde, succeeded him. Chongde was considered the last great khagan of the Uyghur Khaganate and bore the title Kün tengride ülüg bulmïsh alp küchlüg bilge "Greatly born in sun heaven, victorious, strong and wise". His achievements included improved trade up with the region of Sogdia, and on the battlefield he repulsed a force of invading Tibetans in 821. After defeating the Tibetan and Karluk force, the Uyghurs entered the Principality of Ushrusana and plundered the region.[30] In 822, the Uyghurs sent troops to help the Tang in quelling rebels. The Tang refused the offer but had to pay them 70,000 pieces of silk to go home.[23] In 823, the Tibetan Empire waged war on the Uyghurs.[31] In 824, Chongde died and was succeeded by a brother, Qasar. In 832, Qasar was murdered. He was succeeded by the son of Chongde, Hu. In the same year, the Tibetan Empire failed to make war on the Uyghurs.[31]

الانهيار

In 839, Hu was forced to commit suicide and a minister named Kürebir seized the throne with the help of 20,000 Shatuo horsemen from Ordos. In the same year, there was a famine and an epidemic, with a particularly severe winter that killed much of the livestock the Uyghur economy was based on.[33]

في الربيع التالي، عام 840، واحد من الوزراء الاويغور التسع، كولوگ بغا، غريم كوربير، فر إلى قبيلة القيرغيز ودعاهم للغزو من الشمال بقوة تقدر بحوالي 80,000 فارس. ونهبوا عاصمة الاويغور اوردو بالق، وسووها بالأرض. وألقى القيرغيز القبض على خاقان الاويغور كوربير Kürebir (خسا) وقطعوا رأسه على الفور. وواصل القيرغيز تدمير باقي مدن الاويغور، حارقين إياهم حتى صاروا هشيماً تذروه الرياح. The Uyghurs fled in two groups. A 30,000-strong group led by the aristocrat Ormïzt sought refuge in Tang territory but Emperor Wuzong of Tang ordered the borders to be closed. The other group, 100,000 strong, led by Öge, son of Baoyi and the new khagan of the defeated Uyghur Khaganate, also fled to Tang territory. However Öge demanded a Tang city for residence as well as the protection of Manichaeans and food. Wuzong found the demands unacceptable and refused. He granted Ormïzt asylum in return for the use of his troops against Öge. Two years later, Wuzong extended the order to Christianity, Zoroastrianism, and especially Buddhism.[34]

The Yenisei Kyrgyz and Tang dynasty launched a successful war between 840 and 848 against the Uyghur Khaganate using their claimed familial ties as justification for an alliance.[35]

In 841, Öge led the Uyghurs in an invasion of today Shaanxi.

In 843, a Tang army led by Shi Xiong attacked the Uyghurs led by Öge and slaughtered 10,000 Uyghurs on February 13, 843 at "Kill the Barbarians" Mountain (Shahu).[36] Öge was wounded.[37][36][38][39] After the defeat of Öge, Wuzong ordered Ormïzt's troops to be broken up and dispersed among different units. Ormïzt refused to obey. His troops were massacred by general Liu Mian. With the defeat of the two major Uyghur groups, Wuzong saw his chance to get rid of the Manichaeans. He ordered Manichaean temples in several cities to be destroyed, the confiscation of their estates, and the execution of the clergy.[40]

In the fourth moon of 843 an Imperial edict was issued [ordering] the Manichaean priests of the empire to be killed. [. . .] The Manichaean priests are highly respected by the Uighurs.[34]

— Ennin

In 846, the penultimate Uyghur khagan, Öge, was killed after having spent his 6-year reign fighting the Kyrgyz, the supporters of his rival Ormïzt, a brother of Kürebir, and Tang dynasty troops in Ordos and today Shaanxi.[20] His brother, Enian Qaghan, was decisively defeated by Tang forces in 847.[40]

بعد الامبراطورية

The Yenisei Kyrgyz who replaced the Uyghur Khaganate were unsophisticated and had little interest in running the empire which they had destroyed. They held the territory from Lake Baikal in the east to the Irtysh River in the west and left Kulug Bagha, the Uyghur who defected to them, in charge of the Orkhon Valley. During the reign of Emperor Yizong of Tang (860–873), there were three recorded contacts between the Tang and Kyrgyz, but the nature of their relationship remains unclear. Tang policy makers argued that there was no point in building any relations with the Kyrgyz since the Uyghurs no longer threatened them. The Khitans seized the Orkhon Valley from the Kyrgyz in 890 and no further opposition from the Kyrgyz is recorded.[41][42]

The Khitan ruler Abaoji did extend his influence onto the Mongolian Plateau in 924, but there is no indication whatsoever of any conflict with the Kyrgyz. The only information we have from Khitan (Liao) sources regarding the Kyrgyz indicates that the two powers maintained diplomatic relations. Scholars who write of a Kyrgyz "empire" from about 840 to about 924 are describing a fantasy. All available evidence suggests that despite some brief extensions of their power onto the Mongolian Plateau, the Kyrgyz did not maintain a significant political or military presence there after their victories in the 840s.[43]

— Michael Drompp

After the fall of the Uyghur Khaganate, the Uyghurs migrated south and established the Ganzhou Uyghur Kingdom in modern Gansu[44] and the Kingdom of Qocho near modern Turpan. The Uyghurs in Qocho converted to Buddhism, and, according to Mahmud al-Kashgari, were "the strongest of the infidels", while the Ganzhou Uyghurs were conquered by the Tangut people in the 1030s.[45] Even so, Kashgari praised contemporary Uyghurs as bilingual Turkophones whose Turkic dialect remained "pure" and "most correct" (just like dialects spoken by monolingual Yagmas, and Tuhsis); meanwhile, Kashgari derided other bilingual Turkophones (Qay, Tatars, Basmyls, Chömüls, Yabakus, etc.), for incorporating foreign loanwords and "slurring" in their speech.[46] In 1134, Qocho became a vassal of Yelü Dashi's nascent Qara Khitai empire. In 1209, the Qocho ruler Idiqut (" Lord of happiness") Barchuk Art Tegin declared his allegiance to Genghis Khan, and the Uyghurs became important civil servants in the later Mongol Empire, which adapted the Old Uyghur alphabet as its official script. According to the New Book of Tang, a third group went to seek refuge among the Karluks.[47]

The Karluks, together with other tribes such as the Chigils and Yagmas, later founded the Kara-Khanid Khanate (940–1212). Some historians associate the Karakhanids with the Uyghurs as the Yaghmas were linked to the Toquz Oghuz. Sultan Satuq Bughra Khan, believed to be a Yagma from Artux, converted to Islam in 932 and seized control of Kashgar in 940, giving rise to the new dynasty, known as Karakhanids.[48]

Relationship with the Sogdians

In order to control trade along the Silk Road, the Uyghurs established a trading relationship with the Sogdian merchants who controlled some oases of Central Asia. As described above, the Uyghur adoption of Manichaeism was one aspect of this relationship—choosing Manichaeism over Buddhism may have been motivated by a desire to show independence from Tang influence.[49] Not all Uyghurs supported conversion—an inscription at Ordu-Baliq states that Manichaens tried to divert people from their ancient shamanistic beliefs.[50] A rather partisan account from a Uyghur-Manichean text of that period demonstrates the unbridled enthusiasm of the khaghan for Manichaeism:

"At that time when the divine Bogu Khan had thus spoken, we the Elects of all the people living within the land rejoiced. It is impossible to describe this ourjoy. The people told the story to one another and rejoiced. At that time, groups of thousands and tens of thousands assembled and with pastimes of all sorts they entertained themselves even unto dawn. And at the break of the day they made a short fast. The divine ruler Bogu Khan and all the elects of his retinue mounted on horses, and all the princes and the princesses led by those of high repute, the big and the small, the whole people, amidst great rejoicing proceeded to the gate of the city. And when the divine ruler had entered the city, he put the crown on his head... and sat upon the golden throne."

— Uyghur-Manichean text.[50]

As conversion was based on political and economic concerns regarding trade with the Sogdians, it was driven by the rulers and often encountered resistance in lower societal strata. Furthermore, as the khaghan's political power depended on his ability to provide economically for his subjects, "alliance with the Sogdians through adopting their religion was an important way of securing this objective."[49] Both the Sogdians and the Uyghurs benefited enormously from this alliance. The Sogdians enabled the Uyghurs to trade in the Western Regions and exchange silk from China for other goods. For the Sogdians it provided their Chinese trading communities with Uyghur protection. The 5th and 6th centuries saw a large emigration of Sogdians to China. The Sogdians were main traders along the Silk Roads, and China was always their biggest market. Among the paper clothing found in the Astana cemetery near Turfan is a list of taxes paid on caravan trade in the Gaochang kingdom in the 620s. The text is incomplete, but out of the 35 commercial operations it lists, 29 involve a Sogdian trader.[51] Ultimately both rulers of nomadic origin and sedentary states recognized the importance of merchants like the Sogdians and made alliances to further their own agendas in controlling the Silk Roads.

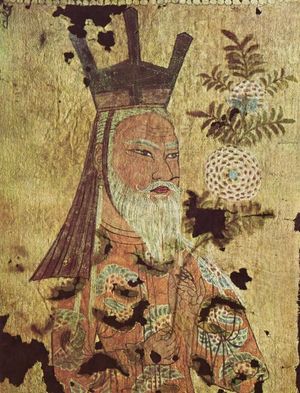

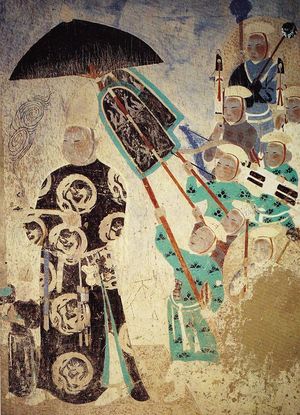

Uyghur Manichaean Elect depicted on a temple banner from Qocho.

Karabalghasun

The Uyghurs created an empire with clear Persian influences, particularly in areas of government.[52] Soon after the empire was founded, they emulated sedentary states by establishing a permanent, settled capital, Karabalghasun (Ordu-Baliq), built on the site of the former Göktürk imperial capital, northeast of the later Mongol capital, Karakorum. The city was a fully fortified commercial center, typical along the Silk Road, with concentric walls and lookout towers, stables, military and commercial stores, and administrative buildings. Certain areas of the town were allotted for trade and handcrafts, while in the center of the town were palaces and temples, including a monastery. The palace had fortified walls and two main gates, as well as moats filled with water and watchtowers.

The khaghan maintained his court there and decided the policies of the empire. With no fixed settlement, the Xiongnu had been limited in their acquisition of Chinese goods to what they could carry. As stated by Thomas Barfield, "the more goods a nomadic society acquired the less mobility it had, hence, at some point, one was more vulnerable trying to protect a rich treasure house by moving it than by fortifying it."[53][صفحة مطلوبة] By building a fixed city, the Uyghurs created a protected storage space for trade goods from China. They could hold a stable, fixed court, receive traders, and effectively cement their central role in Silk Road exchange.[53][صفحة مطلوبة] However, the vulnerability that came with having a fixed city was to be the downfall of the Uyghurs.[49]

قائمة خاقانات الاويغور

القائمة التالية مبنية على بحث دنيس سينور، "The Uighur Empire of Mongolia," Studies in Medieval Inner Asia, Variorum, 1997, V: 1-25. وبسبب الألقاب الاويغورية والصينية المعقدة والمتضاربة، فالاشارات إلى الحكام أصبحت الآن تتضمن نمطياً ترتيبهم في التسلسل، وهو الأمر الذي ازداد تعقيداً باستبعاد ابن عابر للحاكم رقم 4 بين الحاكمين 5 و 6 في عام 790، وكذلك اشتمالها على حكم لحظي بين الحاكمين 7 و 9.

القائمة التالية مبنية على Yihong Pan's "Sui-Tang Foreign Policy: Four case studies".[54]

| Personal Name | Turkic title | Chinese title | Reign |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kutlug Bilge Qaghan Yaoluoge Yibiaobi | Qutlugh Bilge Köl Qaghan | Huairen Khagan (懷仁可汗) | 744-747 |

| Bayanchur Qaghan Yaoluoge Moyanchuo | Tengrida Bolmish El Etmish Bilge Qaghan | Yingwu Weiyuan Pijia Qaghan (英武威遠毗伽闕可汗) | 747-759 |

| Bogu Qaghan Yaoluoge Yidijian | Tengrida Qut Bolmish El Tutmish Alp Külüg Bilge Qaghan | Yingyi Qaghan (英義可汗) | 759-780 |

| Tun Baga Tarkhan Yaoluoge Dunmohe | Alp Qutlugh Bilge Qaghan | Wuyi Chenggong Qaghan (武義成功可汗)

Changshou Tianqin Qaghan (長壽天親可汗) |

780-789 |

| Kulug Bilge Qaghan Yaoluoge Duoluosi | Külüg Bilge Qaghan | Zhongzhen Qaghan (忠貞可汗) | 789-790 |

| Qutluq Bilge Qaghan Yaoluoge Achuo | Qutluq Bilge Qaghan | Fengcheng Qaghan (奉誠可汗) | 790-795 |

| Qutluq II Bilge Qaghan Adie Guduolu, later

Yaoluoge Guduolu |

Ay Tengride Ulugh Bolmish Alp Qutluq Külüg Bilge Qaghan | Huaixin Qaghan (懷信可汗) | 795-808 |

| Baoyi Qaghan | Ay Tengride Qut Bolmish Alp Bilge Qaghan | Baoyi Qaghan (保義可汗) | 808-821 |

| Chongde Qaghan | Kün Tengride Ulugh Bolmish Küçlüg Bilge Qaghan | Chonde Qaghan (崇德可汗) | 821-824 |

| Zhaoli Qaghan | Ay Tengride Qut Bolmish Alp Bilge Qaghan | Zhaoli Qaghan (昭禮可汗) | 824-833 |

| Zhangxin Qaghan Yaoluoge Hu | Ay Tengride Qut Bolmish Alp Külüg Bilge Qaghan | Zhangxin Qaghan (彰信可汗) | 833-839 |

| Qasar Qaghan (Usurper) Jueluowu or

Yaoluoge Hesa |

Qasar Qaghan (㕎馺特勒) | 839-840 | |

| Uge Qaghan Yaoluoge Wuxi | Wujie Qaghan (烏介可汗) | 841-846 | |

| Enian Qaghan Yaoluoge E'nian | Enian Qaghan (遏捻可汗) | 846-848 |

Menglig Qaghan (r. 848-?), (personal name, Mang/Pang Te-qin 厖特勤), sovereign title: Ay Tengride Qut Bolmiş Alp Kutlugh Bilge Qaghan 溫祿登里邏汩沒密施合俱錄毗伽, Chinese title: Huaijian Qaghan 懷建可汗. Moved his political centre to the west.

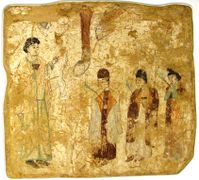

Buddhist and Manichean Uyghur artifacts

Below is a set of images of Buddhist and Manichean Uyghurs, found from the Bezeklik caves and Mogao grottoes.

صور

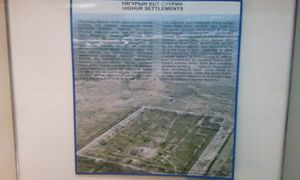

أطلال قصر ملك أويغوري في أستانا قرةخوجة، حوض تورپان، شينجيانگ، الصين (القرون 9-13 م)

رؤوس رماح أويغورية. القرن الثامن الميلادي. في المتحف الوطني المنغولي، اولان باتور، منغوليا.

صورة جوية لحصن أويغوري (من القرن الثامن) حالياً في پور-باجين، جمهورية توڤا، روسيا، على بعد 20 كم من الحدود المنغولية.

مقبرة أستانا قرةخوجة في متحف تحت الأرض على بعد 42 كم جنوب شرق تورپان. وقرةخوجة هو بطل أويغوري كان يحمي شعبه من تنين شرير.

See also

| جزء من سلسلة عن | ||||||||||||||

| تاريخ منغوليا | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||

| الفترة القديمة | ||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

| العصور الوسطى | ||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

| الفترة المعاصرة | ||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

| موضوعات | ||||||||||||||

جزء من سلسلة عن |

||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| تاريخ قزخستان | ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

| قبل التاريخ | ||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

| الخانيات المبكرة | ||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

| العصور الوسطى | ||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

| أوائل العصر الحديث | ||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

| فترة ما بعد البدوية | ||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

| موضوعات | ||||||||||||||

- List of Turkic dynasties and countries

- History of Turkic people

- History of the Uyghur people

- An Lushan Rebellion

- Ethnic groups in Chinese history

- Guo Ziyi

الهامش

- ^ Bosworth, C.E. (1 January 1998). History of Civilizations of Central Asia, Volume 4 (in الإنجليزية). UNESCO. p. 428. ISBN 978-92-3-103467-1.

- ^ "Data" (PDF). www.tekedergisi.com. Retrieved 2020-01-19.

- ^ Turchin, Peter; Adams, Jonathan M.; Hall, Thomas D (December 2006). "East-West Orientation of Historical Empires". Journal of World-Systems Research. 12 (2): 222. ISSN 1076-156X. Retrieved 16 September 2016.

- ^ Rein Taagepera (September 1997). "Expansion and Contraction Patterns of Large Polities: Context for Russia". International Studies Quarterly. 41 (3): 475–504. doi:10.1111/0020-8833.00053. JSTOR 2600793.

- ^ China's last Nomads: the history and culture of China's Kazaks Linda Benson, Ingvar Svanberg Edition illustrated, M.E. Sharpe, 1998, ISBN 1563247828, 9781563247828. p.16-19

- ^ Latourette 1964, p. 144.

- ^ أ ب Haywood 1998, p. 3.2.

- ^ Sinor 1990, p. 349.

- ^ "Chapter 217 part 1". 新唐書 [New Book of Tang].

東極室韋,西金山,南控大漠,盡得古匈奴地。

- ^ أ ب Barfield 1989, p. 151.

- ^ Golden 1992, p. 156–157.

- ^ Senga, T. (1990). "The Toquz Oghuz Problem and the Origins of the Khazars". Journal of Asian History. 24 (1): 57–69. JSTOR 419253799.

- ^ Henning 1938, p. 554–558.

- ^ Tang Huiyao, Vol. 98

- ^ Theobald, U. "Huihe 回紇, Huihu 回鶻, Weiwur 維吾爾, Uyghurs" in ChinaKnowledge.de - An Encyclopaedia on Chinese History, Literature and Art

- ^ Rhie, Marylin Martin (15 July 2019). Early Buddhist Art of China and Central Asia, Volume 2 The Eastern Chin and Sixteen Kingdoms Period in China and Tumshuk, Kucha and Karashahr in Central Asia (2 vols) (in الإنجليزية). BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-39186-4.

After the disastrous defeat of the T'ang armies to the rising power of the Arabs at the Battle of the Talas River in 751, T'ang pulled out of Central Asia and the area around Turfan came under the control of the Uighurs, who emerged as the dominant power of Eastern Central Asia.

- ^ أ ب Sinor 1990, p. 317–342.

- ^ أ ب ت Barfield 1989, p. 152.

- ^ Wan 2017, p. 42.

- ^ أ ب Bosworth 2000, p. 70.

- ^ Asimov 1998, p. 194.

- ^ Barfield 1989, p. 153.

- ^ أ ب Barfield 1989, p. 154.

- ^ "Chapter 195". 舊唐書 [Old Book of Tang].

葛祿乘勝取回紇之浮圖川,回紇震恐,悉遷西北部落羊馬於牙帳之南以避之。 [translation: "The Karluks took the opportunity to win control of Uyghur's Fu-tu valley; the Uyghurs, shaken with fear, moved their north-western tribes, with sheep and horses, to the south of the capital to escape."] (In Xin Tangshu, Fu-tu valley (浮圖川) was referred to as Shen-tu Valley 深圖川)

- ^ Beckwith 1987, p. 155-156.

- ^ Beckwith 1987, p. 156.

- ^ Bregel 2003, p. 20.

- ^ Wang 2013, p. 184.

- ^ https://www.repository.cam.ac.uk/bitstream/handle/1810/227056/JTS_SL_01.pdf?sequence=2[bare URL PDF]

- ^ Beckwith 1987, p. 165.

- ^ أ ب Wang 2013, p. 187.

- ^ SKUPNIEWICZ, Patryk (Siedlce University, Poland) (2017). Crowns, hats, turbans and helmets.The headgear in Iranian history volume I: Pre-Islamic Period. Siedlce-Tehran: K. Maksymiuk & G. Karamian. p. 253.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "chapter 217 part 2". 新唐書 [New Book of Tang].

方歲饑,遂疫,又大雪,羊、馬多死

- ^ أ ب Baumer 2012, p. 310-311.

- ^ Drompp, Michael R. (1999). "Breaking the Orkhon Tradition: Kirghiz Adherence to the Yenisei Region after A. D. 840". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 119 (3): 390–403. doi:10.2307/605932. JSTOR 605932. Retrieved 4 September 2021.

- ^ أ ب Drompp 2005, p. 114.

- ^ John W. Dardess (10 September 2010). Governing China: 150–1850. Hackett Publishing. pp. 32–. ISBN 978-1-60384-447-5.

- ^ Drompp, Michael R. (2018). "THE UIGHUR-CHINESE CONFLICT OF 840-848". In Cosmo, Nicola Di (ed.). Warfare in Inner Asian History (500-1800). Handbook of Oriental Studies. Section 8 Uralic & Central Asian Studies. BRILL. p. 92. ISBN 978-9004391789.

- ^ Drompp, Michael R. (2018). "THE UIGHUR-CHINESE CONFLICT OF 840-848". In Cosmo, Nicola Di (ed.). Warfare in Inner Asian History (500-1800). Handbook of Oriental Studies. Section 8 Uralic & Central Asian Studies. BRILL. p. 99. ISBN 978-9004391789.

- ^ أ ب Baumer 2012, p. 310.

- ^ Barfield 1989, p. 165.

- ^ Golden 1992, p. 181.

- ^ Drompp, Michael (January 2002), "The Yenisei Kyrgyz from Early Times to the Mongol Conquest", The Turks (Ankara: Yeni Türkiye) 1: 480–488, https://www.academia.edu/10197431

- ^ Golden 2011, p. 47.

- ^ Millward 2007, p. 50.

- ^ Maħmūd al-Kašğari. "Dīwān Luğāt al-Turk". Edited & translated by Robert Dankoff in collaboration with James Kelly. In Sources of Oriental Languages and Literature. (1982). Part I. p. 82-84

- ^ 新唐書 [New Book of Tang].

俄而渠長句錄莫賀與黠戛斯合騎十萬攻回鶻城,殺可汗,誅掘羅勿,焚其牙,諸部潰其相馺職與厖特勒十五部奔葛邏祿,殘眾入吐蕃、安西。 [Translation: Soon the great chief Julumohe and the Kirghiz gathered a hundred thousand riders to attack the Uyghur city; they killed the Kaghan, executed Jueluowu, and burnt the royal camp. All the tribes were scattered—its ministers Sazhi and Pang Tele with fifteen clans fled to the Karluks, the remaining multitude went to the Tibetan Empire and Anxi.]

- ^ Sinor 1990, p. 355–357.

- ^ أ ب ت Sinor 1990.

- ^ أ ب Prof. R. Roemer, ed. (1984). "The Uighur Empire of Mongolia (chapter 5)". Guo ji zhongguo bian jiang xue shu hui yi lun wen chu gao. Taipei.

- ^ de la Vaissière, Étienne. "Sogdians in China: a short history and some new discoveries".

- ^ Azad, Shirzad (9 February 2017). Iran and China: A New Approach to Their Bilateral Relations. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 34. ISBN 978-1-4985-4458-0.

- ^ أ ب Barfield 1989.

- ^ Pan, Yihong (1990). Sui-Tang foreign policy: four case studies (Thesis) (in الإنجليزية). University of British Columbia. doi:10.14288/1.0098752.

- ^ Marshall Cavendish Corporation (2006). Peoples of Western Asia. p. 364.

{{cite book}}: External link in|ref= - ^ Bosworth, Clifford Edmund (2007). Historic Cities of the Islamic World. p. 280.

{{cite book}}: External link in|ref= - ^ Borrero, Mauricio (2009). Russia: A Reference Guide from the Renaissance to the Present. p. 162.

{{cite book}}: External link in|ref=

- The Uighur Empire: According to the T'ang Dynastic Histories, A Study in Sino-Uighur Relations, 744-840. Author: Mackerras, Colin. Publisher: Australian National University Press, 1972. 226 pages.

Further reading

- Jiu Tangshu (舊唐書) Old Book of Tang Chapter 195 (in Chinese)

- Xin Tangshu (新唐書) New Book of Tang, chapter 217, part 1 and part 2 (in Chinese). Translation in English here [1] (most of part 1 and beginning of part 2).

- Die chinesische Inschrift auf dem uigurischen Denkmal in Kara Balgassun (1896)

- Articles containing صينية-language text

- CS1 uses الصينية-language script (zh)

- All articles with bare URLs for citations

- Articles with bare URLs for citations from March 2022

- Articles with PDF format bare URLs for citations

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Articles containing traditional Chinese-language text

- Articles with unsourced statements from June 2007

- Articles containing Chinese-language text

- Pages using multiple image with auto scaled images

- مقالات بالمعرفة بحاجة لذكر رقم الصفحة بالمصدر from July 2022

- Portal-inline template with redlinked portals

- Pages with empty portal template

- Uyghur Khaganate

- Turkic peoples of Asia

- بلدان سابقة في التاريخ الصيني

- ملكيات سابقة في آسيا

- 744 establishments

- States and territories established in the 740s

- 847 disestablishments

- Khanates

- States and territories disestablished in the 9th century

- Former empires

- انحلالات 848

- دول ومناطق تأسست في 742

- أويغور

- دول توركية تاريخية

- تاريخ الشعوب التوركية

- بدو اوراسيون

- حضارات وامبراطوريات الرماة الفرسان

- تاريخ منغوليا

- تاريخ آسيا الوسطى