قرةخواجة

مملكة قرةخواجة | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 843–1132 (أصبحت تابعة لـ لياو الغربية) 1209 (أصبحت تابعة لـ المنغول) أواخر القرن 13 إلى منتصف القرن 14 (خاضعة تماماً لـ خانية چقطاي) | |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| الحالة | مملكة | ||||||||||||

| Capital | گاوتشانگ، بشباليق | ||||||||||||

| اللغات المشتركة | الطخارية، الهندو-إيرانية ولاحقاً لغة الأويغور القديمة | ||||||||||||

| الدين | كنيسة المشرق ("النسطورية")، مانوية،[1][2] Buddhism[3] | ||||||||||||

| الحكومة | ملكية | ||||||||||||

| Idiqut | |||||||||||||

| التاريخ | |||||||||||||

• Established | 843 | ||||||||||||

• Disestablished | 1132 (أصبحت تابعة لـ لياو الغربية) 1209 (أصبحت تابعة لـ المنغول) أواخر القرن 13 إلى منتصف القرن 14 (خاضعة تماماً لـ خانية چقطاي) | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

جزء من سلسلة عن |

|---|

| تاريخ شينجيانگ |

|

قرةخواجة (الصينية: 高昌回鶻; پنين: Gāochāng Húihú; lit. 'أويغور قوچو'، بالمنغولية ᠦᠶᠭᠦᠷ Uihur "id.")، ويُعرفون أيضاً بإسم إديقوت،[7][8][9][10] ("الثروة المقدسة"؛ "المجد") كانت مملكة طخارية-أويغورية نشأت في 843.

أسسها اللاجئون الأويغور الفارون من دمار خاقانية الأويغور بعد أن طردهم قيرغير ينيسـِيْ. وقد اتخذوا عاصمتهم الصيفية في قرةخواجة (وتُدعى أيضاً قوچو، وحالياً مديرية گاوتشانگ في طرفان) وعاصمتهم الشتوية في بشباليق (حالياً ناحية جيمسار، وتُعرف أيضاً بإسم محافظة تينگ).[11] ويشار إلى سكانها بإسم "أويغور شيژو" على الاسم القديم من صينية تانگ لـ گاوتشانگ، أو أويغور قوچو نسبةً إلى عاصمتهم، أو أويغور كوچار نسبةً إلى مدينة أخرى (كوچار) سيطروا عليها، أو أويغور أرسلان (الأسد) نسبةً إلى لقب ملكهم.

ويتعقب حكام مملكة قوچو نسبهم إلى قتلغ من أسرة إدسيز في خاقانية الأويغور.

خط زمني

في 843، هاجرت جماعة من الأويغور جنوباً بقيادة پانگتلى واحتلوا قرةشهر و كوچار.

العرق

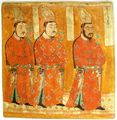

While the Uyghur language is a Turkic language, James A. Millward claimed that the Uyghurs were generally "Mongoloid" (an archaic term meaning "appearing ethnically Eastern or Inner Asian"), giving as an example the images of Uyghur patrons of Buddhism in Bezeklik, temple 9, until they began to mix with the Tarim Basin's original, Indo-European-speaking "Caucasoid" inhabitants,[12] such as the so-called Tocharians. Buddhist Uyghurs created the Bezeklik murals.[13]

Please help improve this section by expanding it. Further information might be found on the talk page or at requests for expansion. (July 2018) |

التاريخ

النزاع مع قرةخانات

The Buddhist Uyghurs came into conflict with their Muslim neighbors, notably the Kara-Khanid Khanate. Its ruler Sultan Satuq Bughra Khan razed Qocho's Buddhist temples.[14]

كتاب محمود القشغري Three Turkic Verse Cycles recorded in order - في وادي إرتيش، a defeat inflicted on "infidel tribes" at the hands of the Karakhanids, secondly, the Buddhist Uyghurs being attacked by the Muslim Turks, and finally, a defeat inflicted upon "a city between Tangut and China.", Qatun Sini, at the hands of the Tangut Khan.[15][16]

أهان محمود القشغري البوذيين الأويغور بأنهم "كلاب الأويغور" وسماهم "تات"، التي تشير إلى "كفار الأويغور" حسب the Tuxsi and Taghma, while other Turks called Persians "tat".[17][18] While al-Kashgari displayed a different attitude towards the Turks diviners beliefs and "national customs", he expressed towards Buddhism a hatred in his Diwan where he wrote the verse cycle on the war against Uighur Buddhists. Buddhist origin words like toyin (a cleric or priest) and Burxān or Furxan[19][20] (meaning Buddha,[21][22][23] acquiring the generic meaning of "idol" in the Turkic language of al-Kashgari) had negative connotations to Muslim Turks.[24][25]

The wars against Buddhist, shamanist, and Manichaean Uyghurs were considered a jihad by the Kara-Khanids.[26][27][28]

Islam was the enemy of the Eastern Christian and Buddhist Turfan Uyghur Kingdom.[29]

The Imams and soldiers who died in the battles against the Uyghur Buddhists and Khotan Buddhist Kingdom during the Tarim Basin's Islamification at the hands of the Karakhanids are revered as saints.[30]

It was possible the Muslims drove some Uyghur Buddhist monks towards taking asylum لدى أسرة شيا الغربية.[31]

حكم المنغول

Alans were recruited into the Mongol forces with one unit called the Asud or "Right Alan Guard", which was combined with "recently surrendered" soldiers, Mongols, and Chinese soldiers stationed in the area of the former kingdom of Qocho وفي بشباليق (حالياً هي Jimsar County), the Mongols established a Chinese military colony led by Chinese general Qi Kongzhi.[32]

الفتح على يد الچقطاي المسلمين

الأويغور البوذيون في مملكة قرةخواجة وطرفان اعتنقوا الإسلام فتحاً أثناء غزوة (دينية) قام بها حاكم خانية چقطاي المسلمة خضر خوجة (حكم 1389-1399). Qocho and Turfan were viewed as part of "Khitay",[33] which was a name for China.[34] The 1390s war by Kizir Khoja's against the Uyghurs (Huihu) of Qoco (Qocho) is also considered a Jihad. As a consequence of the Jihad, the religion of Islam was forced on Qocho and this resulted in the city of Jiaohe being abandoned.[35] مجاهدو خانية چقطاي المسلمة هزموا الأويغور و طـُهـِّرت هامي من الديانة البوذية التي حل محلها الإسلام.[36] The Islamic conversion forced on the Buddhist Hami state was the final event in the Islamization.[26][37][38]

قائمة الملوك (إيديقوت)

There are numerous gaps in our knowledge of the Uyghur rulers of Qocho prior to the thirteenth century. The title of the ruler of Qocho was idiqut or iduq qut. In 1308, Nolen Tekin was granted the title Prince of Gaochang by the Emperor Ayurbarwada. The following list of rulers is drawn mostly from Turghun Almas, Uyghurlar (Almaty, 1992), vol. 1, pp. 180–85.[39]

- 850–866: Pan Tekin

- 866–871: Boko Tekin

... - 940–948: Irdimin Khan

- 948–985: Arslan (Zhihai) Khan

... - 1126–????: Bilge (Biliege) Tekin

... - ????–????: Isen Tomur

... - 1208–1235: Baurchuq (Barchukh) Art Tekin

- 1235–1245: Qusmayin

- 1246–1255: Salun Tekin

- 1255–1265: Oghrunzh Tekin

- 1265–1266: Mamuraq Tekin

- 1266–1276: Qozhighar Tekin

- 1276–1318: Nolen Tekin

- 1318–1327: Tomur Buqa

- 1327–1331: Sunggi Tekin

- 1331–1335: Taypan (Taipingnu)

- 1335–1353: Yuelutiemur

- 1353–????: Sangge

معرض صور

انظر أيضاً

- Kara Del

- Ming–Turpan conflict

- History of the Uyghur people

- History of Xinjiang

- Ganzhou Uyghur Kingdom

الهامش

- ^ Éric Trombert; Étienne de La Vaissière (2005). Les sogdiens en Chine. École française d'Extrême-Orient. p. 299. ISBN 978-2-85539-653-8.

- ^ Hansen, Valerie. "Les Sogdiens en Chine" (PDF).

{{cite web}}:|chapter=ignored (help) - ^ Stephen F. Teiser (1 April 2003). The Scripture on the Ten Kings: And the Making of Purgatory in Medieval Chinese Buddhism. University of Hawaii Press. pp. 55–. ISBN 978-0-8248-2776-2.

- ^ Marshall Cavendish Corporation (2006). Peoples of Western Asia. p. 364.

{{cite book}}: External link in|ref= - ^ Bosworth, Clifford Edmund (2007). Historic Cities of the Islamic World. p. 280.

{{cite book}}: External link in|ref= - ^ Borrero, Mauricio (2009). Russia: A Reference Guide from the Renaissance to the Present. p. 162.

{{cite book}}: External link in|ref= - ^ Joint Centre for Asia Pacific Studies (1996). Cultural contact, history and ethnicity in inner Asia: papers presented at the Central and Inner Asian Seminar, University of Toronto, March 4, 1994 and March 3, 1995. Joint Centre for Asia Pacific Studies. p. 137.

- ^ Sir Charles Eliot (4 January 2016). Hinduism and Buddhism: An Historical Sketch. Sai ePublications & Sai Shop. pp. 1075–. GGKEY:4TQAY7XLN48.

- ^ Baij Nath Puri (1987). Buddhism in Central Asia. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. pp. 77–. ISBN 978-81-208-0372-5.

- ^ Charles Eliot; Sir Charles Eliot (1998). Hinduism and Buddhism: An Historical Sketch. Psychology Press. pp. 205–. ISBN 978-0-7007-0679-2.

- ^ Millward 2007, p. 46.

- ^ Millward 2007, p. 43.

- ^ Modern Chinese Religion I (2 vol.set): Song-Liao-Jin-Yuan (960-1368 AD). BRILL. 8 December 2014. pp. 895–. ISBN 978-90-04-27164-7.

- ^ Dust in the Wind: Retracing Dharma Master Xuanzang's Western Pilgrimage. Rhythms Monthly. 2006. p. 479. ISBN 978-986-81419-8-8.

- ^ Robert Dankoff (2008). From Mahmud Kaşgari to Evliya Çelebi. Isis Press. p. 27. ISBN 978-975-428-366-2.

- ^ Harvard Ukrainian Research Institute (1980). Harvard Ukrainian studies. Harvard Ukrainian Research Institute. p. 151.

- ^ https://web.archive.org/web/20151118063834/http://projects.iq.harvard.edu/huri/files/viii-iv_1979-1980_part1.pdf p. 160.

- ^ Harvard Ukrainian Research Institute (1980). Harvard Ukrainian studies. Harvard Ukrainian Research Institute. p. 160.

- ^ Giovanni Stary (1996). Proceedings of the 38th Permanent International Altaistic Conference (PIAC): Kawasaki, Japan, August 7-12, 1995. Harrassowitz Verlag in Kommission. pp. 17, 27. ISBN 978-3-447-03801-0.

- ^ James Russell Hamilton (1971). Conte bouddhique du bon et du mauvais prince. Éditions du Centre national de la recherche scientifique. p. 114.

- ^ Linguistica Brunensia. Masarykova univerzita. 2009. p. 66.

- ^ Egidius Schmalzriedt; Hans Wilhelm Haussig (2004). Die mythologie der mongolischen volksreligion. Klett-Cotta. p. 956. ISBN 978-3-12-909814-1.

- ^ http://www.asianpa.net/assets/upload/articles/LZnCyNgsTym1unXG.pdf https://www.asianpa.net/assets/upload/articles/LZnCyNgsTym1unXG.pdf https://tr.wikisource.org/wiki/Div%C3%A2n-%C4%B1_L%C3%BCgati%27t-T%C3%BCrk_dizini http://www.hasmendi.net/Genel%20Dosyalar/KASGARLI_MAHMUT_LUGATI.pdf http://www.slideshare.net/ihramcizade/divan-lugatitrk http://www.philology.ru/linguistics4/tenishev-97a.htm http://www.biligbitig.org/divanu-lugat-turk http://docplayer.biz.tr/5169964-Divan-i-luqat-it-turk-dizini.html http://turklukbilgisi.com/sozluk/index.php/list/7/,F.xhtml https://www.ceeol.com/search/article-detail?id=354765 https://www.ceeol.com/content-files/document-355264.pdf http://divanilugatitturk.blogspot.com/2016/01/c-harfi-divanu-lugat-it-turk-sozlugu_1.html https://plus.google.com/108758952067162862352 https://plus.google.com/108758952067162862352/posts/Ww2ce29Qfkz

- ^ Dankoff, Robert (Jan–Mar 1975). "Kāšġarī on the Beliefs and Superstitions of the Turks". Journal of the American Oriental Society. American Oriental Society. 95 (1): 69. doi:10.2307/599159. JSTOR 599159.

- ^ Robert Dankoff (2008). From Mahmud Kaşgari to Evliya Çelebi. Isis Press. p. 79. ISBN 978-975-428-366-2.

- ^ أ ب Jiangping Wang (12 October 2012). 中国伊斯兰教词汇表. Routledge. pp. xvi–. ISBN 978-1-136-10650-7.

- ^ Jiangping Wang (12 October 2012). Glossary of Chinese Islamic Terms. Routledge. pp. xvi. ISBN 978-1-136-10658-3.

- ^ Jianping Wang (2001). 中国伊斯兰教词汇表. Psychology Press. pp. xvi. ISBN 978-0-7007-0620-4.

- ^ Millward (2007), p. 43.

- ^ David Brophy (4 April 2016). Uyghur Nation: Reform and Revolution on the Russia-China Frontier. Harvard University Press. pp. 29–. ISBN 978-0-674-97046-5.

- ^ Ruth W. Dunnell (January 1996). The Great State of White and High: Buddhism and State Formation in Eleventh-Century Xia. University of Hawaii Press. p. 54. ISBN 978-0-8248-1719-0.

- ^ Morris Rossabi (1983). China Among Equals: The Middle Kingdom and Its Neighbors, 10th-14th Centuries. University of California Press. pp. 255–. ISBN 978-0-520-04562-0.

- ^ James A. Millward (2007). Eurasian Crossroads: A History of Xinjiang. Columbia University Press. pp. 69–. ISBN 978-0-231-13924-3.

- ^ Hamilton Alexander Rosskeen Gibb; Bernard Lewis; Johannes Hendrik Kramers; Charles Pellat; Joseph Schacht (1998). The Encyclopaedia of Islam. Brill. p. 677.

- ^ Journal of the Institute of Archaeology, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences. Archaeology Publications. 2002. p. 72.

- ^ Dust in the Wind: Retracing Dharma Master Xuanzang's Western Pilgrimage. Rhythms Monthly. 2006. pp. 480–. ISBN 978-986-81419-8-8.

- ^ Jiangping Wang (12 October 2012). Glossary of Chinese Islamic Terms. Routledge. pp. xvi–. ISBN 978-1-136-10658-3.

- ^ Jianping Wang (2001). 中国伊斯兰教词汇表. Psychology Press. pp. xvi–. ISBN 978-0-7007-0620-4.

- ^ As duplicated and augmented in George Qingzhai Zhao, Marriage as Political Strategy and Cultural Expression: Mongolian Royal Marriages from World Empire to Yuan Dynasty (Peter Lang, 2008), p. 165–66, 174–76.

ببليوگرافيا

- Asimov, M.S. (1998), History of civilizations of Central Asia Volume IV The age of achievement: A.D. 750 to the end of the fifteenth century Part One The historical, social and economic setting, UNESCO Publishing

- Barfield, Thomas (1989), The Perilous Frontier: Nomadic Empires and China, Basil Blackwell

- Benson, Linda (1998), China's last Nomads: the history and culture of China's Kazaks, M.E. Sharpe

- Bregel, Yuri (2003), An Historical Atlas of Central Asia, Brill

- Bosworth, Clifford Edmund (2000), The Age of Achievement: A.D. 750 to the End of the Fifteenth Century - Vol. 4, Part II : The Achievements (History of Civilizations of Central Asia), UNESCO Publishing

- Bughra, Imin (1983), The history of East Turkestan, Istanbul: Istanbul publications

- Drompp, Michael Robert (2005), Tang China And The Collapse Of The Uighur Empire: A Documentary History, Brill

- Golden, Peter B. (2011), Central Asia in World History, Oxford University Press

- Haywood, John (1998), Historical Atlas of the Medieval World, AD 600-1492, Barnes & Noble

- Latourette, Kenneth Scott (1964), The Chinese, their history and culture, Volumes 1-2, Macmillan

- Mackerras, Colin (1990), "Chapter 12 - The Uighurs", in Sinor, Denis, The Cambridge History of Early Inner Asia, Cambridge University Press, pp. 317–342, ISBN 0 521 24304 1

- Mergid, Toqto'a (1344), History of Liao

- Millward, James A. (2007), Eurasian Crossroads: A History of Xinjiang, Columbia University Press

- Mackerras, Colin, The Uighur Empire: According to the T'ang Dynastic Histories, A Study in Sino-Uighur Relations, 744-840. Publisher: Australian National University Press, 1972. 226 pages, ISBN 0-7081-0457-6

- Rong, Xinjiang (2013), Eighteen Lectures on Dunhuang, Brill

- Sinor, Denis (1990), The Cambridge History of Early Inner Asia, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-24304-9

- Soucek, Svat (2000), A History of Inner Asia, Cambridge University Press

- Xiong, Victor (2008), Historical Dictionary of Medieval China, United States of America: Scarecrow Press, Inc., ISBN 0810860538, https://www.amazon.ca/Historical-Dictionary-Medieval-Victor-Cunrui/dp/0810860538/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1438312041&sr=8-1&keywords=historical+dictionary+of+medieval+china

- Xue, Zongzheng (1992), Turkic peoples, 中国社会科学出版社

للاستزادة

- CS1 errors: chapter ignored

- Pages using infobox country with unknown parameters

- Articles containing traditional Chinese-language text

- Articles containing Peripheral Mongolian-language text

- Articles to be expanded since July 2018

- All articles to be expanded

- بلدان سابقة في التاريخ الصيني

- دول توركية تاريخية

- تاريخ شينجيانگ

- تأسيسات 843