پچنگ

خانيات الپچنگ پچنك خانليغي Peçenek Hanlığı | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 860–1091 | |||||||||

خانيات الپچنگ والأراضي المجاورة، ح.1015 | |||||||||

| الحالة | خانية | ||||||||

| اللغات المشتركة | توركية الپچنگ | ||||||||

| التاريخ | |||||||||

• Established | 860 | ||||||||

• Disestablished | 1091 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

پچنگ Pechenegs أو Patzinaks (تركية: Peçenek(ler), رومانية: Pecenegi, روسية: Печенег(и)، أوكرانية: Печеніг(и), مجرية: Besenyő(k), كرواتية: Pečenezi، باليونانية: Πατζινάκοι, Πετσενέγοι, Πατζινακίται, بالجورجية: პაჭანიკი، بالبلغارية: печенеги, pechenegi أو печенези, pechenezi؛ بالصربية: Печенези، لاتينية: Pacinacae, Bisseni) كانوا شعباً توركياً شبه رحال من سهوب آسيا الوسطى يتكلمون لغة الپچنگ التي تنتمي إلى عائلة اللغات التوركية. ثلاثة من العشائر الحاكمة للپچنگ كانوا كنقاني/كنگلي.

اسم العرق

اسم العرق للپچنگ مُشتق من الكلمة التوركية القديمة بمعنى "عديل” (بـَجا، بجا-ناق أو بـَجـِناق bajinaq)، مما يعني ضمناً أنها في البداية كانت تشير إلى "عشيرة أو قبيلة مصاهِرة".[4][5] المصادر المكتوبة بلغات مختلفة استخدمت تسميات مشابهة للاشارة إلى اتحاد لقبائل الپچنگ.[4] They were mentioned under the names Bjnak, Bjanak أو Bajanak في النصوص العربية والفارسية، as Be-ča-nag in Classical Tibetan documents, as Pačanak-i in works written in Georgian, and as Pacinnak in Armenian.[4] آنا كومننه والمؤلفون and other Byzantine authors referred to the Pechenegs as Patzinakoi or Patzinakitai.[4] وفي medieval Latin texts, the Pechenegs were referred to as Pizenaci, Bisseni أو Bessi.[4] الشعوب السلاڤية الشرقية تستخدم المصطلحات Pechenegi أو Pechenezi، بينما الپولنديون يذكرونهم بإسم Pieczyngowie أو Piecinigi.[4] The Hungarian world for Pecheneg is besenyő.[4]

وحسب قسطنطين السابع پورفيروگنيتوس، فإن ثلاثة من "مقاطعات" أو عشائر الپچنگ الثمانية كانوا يُعرفوا جمعاً بإسم كنگر Kangar.[6] وأضاف أنهم حصلوا على اسمهم لأنهم "أكثر شجاعة ونبلاً من الباقين"، "وهذا هو معنى كنگر".[6][7] However, no Turkic word with the meaning suggested by the emperor has been demonstrated.[8] Ármin Vámbéry connected the Kangar denomination to the Kirghiz words kangir ("agile"), kangirmak ("to go out riding") and kani-kara ("black-blooded"), while Carlile Aylmer Macartney associated it with the Chagatai word gang ("chariot").[9] Omeljan Pritsak proposed that the name had initially been a composite term (Kängär As) deriving from the Tocharian word for stone (kank) and the Sarmatian ethnonym As.[10] If the latter assumption is valid, the ethnonym of the three Kangar tribes suggest that Iranian elements contributed to the formation of the Pecheneg people (See also Jassic people).[11]

اللغة

محمود القشغري، a 11th-century man of letters specialized in Turkic dialects argued that the language spoken by the Pechenegs was a variant of the Cuman and Oghuz idioms.[12] He suggested that foreign influences on the Pechenegs gave rise to phonetical differences between their tongue and the idiom spoken by other Turkic peoples.[13] Anna Komnene likewise stated that the Pechenegs and the Cumans shared a common language.[12] Although the Pecheneg language itself died out centuries ago,[14] the names of the Pecheneg "provinces" recorded by Constantine Porphyrogenitus prove that the Pechenegs spoke a Turkic language.[15]

التاريخ

الأصول (حتى ح. 800 أو 850)

ابن خرداذبه، محمود القشغري، محمد الإدريسي and many other Muslim scholars agreed that the Pechenegs belonged to the Turkic peoples.[16] The Russian Primary Chronicle stated that the "Torkmens, Pechenegs, Torks, and Polovcians" descended from "the godless sons of Ishmael, who had been sent as a chastisement to the Christians".[17][18]

Paul Pelliot was the first to propose that a 7th-century Chinese work, the Book of Sui preserved the earliest record on the Pechenegs.[19] It writes of the Pei-ju, a people settled along the En-ch'u and A-lan peoples (identified as the Onogurs and Alans, respectively) east of Fu-lin (the Eastern Roman Empire).[20] In contrast with this view, Victor Spinei argues that the first certain reference to the Pechenegs can be read in a Tibetan translation of an 8th-century Uyghur text.[20] It narrates a war between two peoples, the Be-ča-nag (the Pechenegs) and the Hor (the Ouzes).[20] The Pechenegs inhabited the region along the river Syr Darya at the time when the first records were made of them.[21][20]

الهجرة غرباً (ح. 800 أو 850-ح. 895)

The Pechenegs were forced to leave their Central Asian homeland[5][20] by a coalition of the Oghuz Turks, Karluks and Kimaks.[10] The Pechenegs' westward migration started between the 790s and 850s, but its exact date cannot be determined.[5][20][10] The Pechenegs settled in the steppe corridor[22] بين نهري الأورال والڤولگا.[20]

According to Gardizi and other Muslim scholars who based their works on 9th-century sources, the Pechenegs' new territories were bordered by the Cumans, Khazars, Oghuz Turks and Slavs.[23][22] The same sources also narrate that the Pechenegs regularly waged war against the Khazars and the latter's vassals, the Burtas.[22][24] The Khazars and the Oghuz Turks made an alliance against the Pechenegs and attacked them.[20][25] Outnumbered by the enemy, the Pechenegs started a new migration, invaded the dwelling places of the Hungarians and forced them to leave.[25][22] There is no consensual date for this second migration of the Pechenegs: Pritsak argues that it took place around 830,[22] but Kristó suggests that it could hardly occur before the 850s.[26] The Pechenegs settled along the rivers Donets and Kuban.[22]

It is plausible that the distinction between the "Turkic Pechenegs" and "Khazar Pechenegs" mentioned in the 10th-century Hudud al-'alam had its origin in this period.[22] Spinei proposes that the latter denomination most probably refers to Pecheneg groups accepting Khazar suzerainty.[20] In addition to these two branches, a third group of Pechenegs existed in this period: Constantine Porphyrogenitus and Ibn Fadlan mention that those who decided not to leave their homeland were incorporated into the Oghuz federation of Turkic tribes.[5][22] However, it is uncertain whether this groups' formation is connected to the Pechenegs' first or second migration (as it is proposed by Pritsak and Golden, respectively).[5][22] According to Mahmud al-Kashgari, one of the Üçok clans of the Oghuz Turks[27] was still formed by Pechenegs in the 1060s.[22]

في الأصل، كان للبجناق موئلهم على نهر أتيل, and likewise on the river Geïch, having common frontiers with the Chazars and the so-called Uzes. But fifty years ago the so-called Uzes made common cause with the Chazars and joined battle with the Pechenegs and prevailed over them and expelled them from their country, which the so-called Uzes have occupied till this day. [...] At the time when the Pechenegs were expelled from their country, some of them of their own will and personal decision stayed behind there and united with the so-called Uzes, and even to this day they live among them, and wear such distinguishing marks as separate them off and betray their origin and how it came about that they were split off from their own folk: for their tunics are short, reaching to the knee, and their sleeves are cut off at the shoulder, whereby, you see, they indicate that they have been cut off from their own folk and those of their race.

الأصول والمنطقة

في كتاب محمود القشغري بالقرن 11 الميلادي المسمى ديوان لغات الترك،[29] the name Beçenek is given two meanings. The first is "a Turkish nation living around the country of the Rum", where Rum was the Turkish word for the Eastern Roman Empire (Byzantine Empire). Kashgari's second definition of Beçenek is "a branch of Oghuz Turks"; he subsequently described the Oghuz as being formed of 22 branches, of which the 19th branch was named Beçenek. Max Vasmer derives this name from the Turkic word for "brother-in-law, relative" (تركمانية: bacanak and تركية: bacanak).

By the 9th and 10th centuries, they controlled much of the steppes of southwestern Eurasia and the Crimean Peninsula. Although an important factor in the region at the time, like most nomadic tribes their concept of statecraft failed to go beyond random attacks on neighbours and spells as mercenaries for other powers.

According to Constantine Porphyrogenitus, writing in c. 950, Patzinakia, the Pecheneg realm, stretched west as far as the Siret River (or even the Eastern Carpathian Mountains), and was four days distant from "Tourkias" (i.e. Hungary).

The whole of Patzinakia is divided into eight provinces with the same number of great princes. The provinces are these: the name of the first province is Irtim; of the second, Tzour; of the third, Gyla; of the fourth, Koulpeï; of the fifth, Charaboï; of the sixth, Talmat; of the seventh, Chopon; of the eighth, Tzopon. At the time at which the Pechenegs were expelled from their country, their princes were, in the province of Irtim, Baïtzas; in Tzour, Kouel; in Gyla, Kourkoutai; in Koulpeï, Ipaos; in Charaboï, Kaïdoum; in the province of Talmat, Kostas; in Chopon, Giazis; in the province of Tzopon, Batas.

According to Omeljan Pritsak, the Pechenegs are descendants from the ancient Kangars who originate from Tashkent.

في المصادر الأرمنية

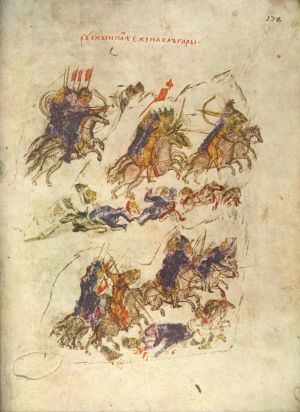

In the Armenian chronicles of Matthew of Edessa Pechenegs are mentioned a couple of times. The first mention is in chapter 75, where it says that in the year 499 (according to the old Armenian calendar — years 1050–51 according to the Gregorian calendar) the Badzinag nation caused great destruction in many provinces of "Rome", i.e. the Byzantine territories. The second is in chapter 103, which is about the Battle of Manzikert. In that chapter it is told that the allies of "Rome", Padzunak and Uz (some branches of the Oghuz Turks) tribes which changed their sides at the peak of the battle and began fighting against the Byzantine forces, side by side with the Seljuq Turks. In the 132nd chapter a war between "Rome" and the Padzinags is described and after the defeat of the Roman (Byzantine) Army, an unsuccessful siege of Constantinople by the Padzinags is mentioned. In that chapter, the Patzinags are described as an "all archer army". In chapter 299, the Armenian prince, Vasil, who was in the Roman Army, sent a platoon of Padzinags (they had settled in the city of Misis, around modern Adana, which is far away from the lands where Pechenegs were then mainly living) to the aid of the Christians.

التحالف مع بيزنطة

In the 9th century, the Byzantines became allied with the Pechenegs, using them to fend off other, more dangerous tribes such as the Rus and the Magyars.

The Uzes, another Turkic steppe people, eventually expelled the Pechenegs from their homeland; in the process, they also seized most of their livestock and other goods. An alliance of Oghuz, Kimeks, and Karluks was also pressing the Pechenegs, but another group, the Samanids, defeated that alliance. Driven further west by the Khazars and Cumans by 889, the Pechenegs in turn drove the Magyars west of the Dnieper River by 892.

Bulgarian Tsar Simeon I employed the Pechenegs to help fend off the Magyars. The Pechenegs were so successful that they drove out the Magyars remaining in Etelköz and the Pontic steppes, forcing them westward towards the Pannonian plain, where they later founded the Hungarian state.

التاريخ المتأخر والانحدار

In the 9th century, the Pechenegs began an uneasy relationship with Kievan Rus'. For more than two centuries they had launched raids into the lands of Rus', which sometimes escalated into full-scale wars (like the 920 war on the Pechenegs by Igor of Kiev, reported in the Primary Chronicle). The Pecheneg wars against Kievan Rus' caused the Slavs from Walachian territories to gradually migrate north of the Dniestr in the 10th and 11th centuries.[32] There were also temporary military alliances, however, like the Byzantine campaign in 943 led by Igor.[33] In 968, the Pechenegs attacked and besieged Kiev; some joined the Prince of Kiev, Sviatoslav I, in his Byzantine campaign of 970-971, though eventually they ambushed and killed the Kievan prince in 972. According to the Primary Chronicle, the Pecheneg Khan Kurya made a chalice from Sviatoslav's skull, a custom of steppe nomads. The fortunes of the Rus'-Pecheneg confrontation swung during the reign of Vladimir I of Kiev (990-995), who founded the town of Pereyaslav upon the site of his victory over the Pechenegs,[34] followed by the defeat of the Pechenegs during the reign of Yaroslav I the Wise in 1036. Shortly thereafter, the weakened Pechenegs were replaced in the Pontic steppe by other nomadic peoples, the Cumans and the Torks. According to Mykhailo Hrushevsky (History of Ukraine-Ruthenia), Pechenegs Horde after its defeat near Kiev moved towards Danube, crossed the river, and disappeared out of the Pontic steppes. The Pechenegs and the Vlachs fought the Magyars in 1068 at Chiraleş, in Transylvania, and lost the battle.[35][36]

After centuries of fighting involving all their neighbours—the Byzantine Empire, Bulgaria, Kievan Rus', Khazaria, and the Magyars—the Pechenegs were annihilated as an independent force in 1091 at the Battle of Levounion by a combined Byzantine and Cuman army under Byzantine Emperor Alexios I Komnenos. Alexios I recruited the defeated Pechenegs whom he settled in the district of Moglena (today in Macedonia) into a tagma « of the Moglena Pechenegs ».[37] Attacked again in 1094 by the Cumans, many Pechenegs were slain or absorbed. They were again defeated by the Byzantines at the Battle of Beroia in 1122, on the territory of modern-day Bulgaria. For some time, significant communities of Pechenegs still remained in the Kingdom of Hungary. With time the Balkan Pechenegs lost their national identity and were fully assimilated, mostly with Magyars and Bulgarians.

In the 12th century, according to Byzantine historian John Kinnamos, the Pechenegs fought as mercenaries for the Byzantine Emperor Manuel I Komnenos in southern Italy against the Norman king of Sicily, William the Bad.[38] A group was present at the battle of Andria in 1155.[39]

In 15th-century Hungary, some people adopted the surname Besenyö, which is Hungarian for Pecheneg; they were most numerous in the county of Tolna. One of the earliest introductions of Islam into Eastern Europe was through the work of an early 11th-century Muslim prisoner who was captured by the Byzantines. The Muslim prisoner was brought into the Besenyö territory of the Pechenegs, where he taught and converted individuals to Islam.[40] In the late 12th century, Abu Hamid al Garnathi referred to Hungarian Pechenegs who were probably Muslims living disguised as Christians. In the southeast of Serbia, there is a village called Pecenjevce founded by Pechenegs. After war with Byzantium, the broken remnants of the tribes found refuge in the area, where they established their settlement.

الزعماء

انظر أيضاً

الهامش

- ^ Marshall Cavendish Corporation (2006). Peoples of Western Asia. p. 364.

{{cite book}}: External link in|ref= - ^ Bosworth, Clifford Edmund (2007). Historic Cities of the Islamic World. p. 280.

{{cite book}}: External link in|ref= - ^ Borrero, Mauricio (2009). Russia: A Reference Guide from the Renaissance to the Present. p. 162.

{{cite book}}: External link in|ref= - ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ Spinei 2003, p. 93.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج Golden 2003, p. I.64.

- ^ أ ب Curta 2006, p. 182.

- ^ Constantine Porphyrogenitus: De Administrando Imperio (ch. 37), p. 171.

- ^ Macartney 1968, p. 104.

- ^ Macartney 1968, pp. 104-105.

- ^ أ ب ت Pritsak 1975, p. 213.

- ^ Spinei 2003, p. 94.

- ^ أ ب Spinei 2003, p. 95.

- ^ Spinei 2009, p. 181.

- ^ Spinei 2009, p. 343.

- ^ Róna-Tas 1999, p. 239.

- ^ Spinei 2009, p. 182.

- ^ Spinei 2009, p. 186.

- ^ Russian Primary Chronicle (year 6604/1096), p. 184)

- ^ Pritsak 1975, p. 211.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د ذ Spinei 2003, p. 113.

- ^ Golden 2003, p. I.63.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د ذ ر Pritsak 1975, p. 214.

- ^ Spinei 2003, p. 114.

- ^ Spinei 2003, pp. 113-114.

- ^ أ ب Kristó 2003, p. 138.

- ^ Kristó 2003, p. 144.

- ^ Atalay 2006, p. I.57.

- ^ Constantine Porphyrogenitus: De Administrando Imperio (ch. 37), pp. 167., 169.

- ^ Maḥmūd, Kāshgarī (1982). Türk Şiveleri Lügatı = Dīvānü Luġāt-It-Türk. Duxbury, Mass: Tekin.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Constantine Porphyrogenitus: De Administrando Imperio (ch. 37), p. 167.

- ^ Tania Velmans Three Notes On Miniatures In The Chronicle of Manasses Macedonian Studies http://ia601200.us.archive.org/27/items/ProblemsOfByzantineHistoriographyThreeNotesOnMiniaturesInThe/bulgaria_manasses.pdf

- ^ V. Klyuchevsky, The course of the Russian history. v.1: "Myslʹ.1987, ISBN 5-244-00072-1

- ^ Ibn Haukal describes the Pechenegs as the long-standing allies of the Rus', whom they invariably accompanied during the 10th century Caspian expeditions.

- ^ The chronicler explains the town's name, derived from the Slavic word for "retake", by the fact that Vladimir "retook" the military glory from the Pechenegs.

- ^ Русскій хронографъ, 2,Хронографъ Западно-Русской редакціи, Complete Collection of Russian Chronicles, XXII,2, Petrograd, 1914, p.211

- ^ V. Spinei, The Romanians and the Turkik nomads North of The Danube Delta from the Tenth to Mid Thirteen Century, Brill, 2009, p.118

- ^ Haldon, John, Warfare, State And Society In The Byzantine World 560-1204, Routledge, 2002, p. 117.

- ^ Kinnamos, IV, 4, p. 143

- ^ Chalandon (1907)

- ^ The preaching of Islam: a history of the propagation of the Muslim faith By Sir Thomas Walker Arnold, pg. 335

المراجع

مصادر رئيسية

- Anna Comnena: The Alexiad (Translated by E. R. A. Sewter) (1969). Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-044958-7.

- Constantine Porphyrogenitus: De Administrando Imperio (Greek text edited by Gyula Moravcsik, English translation b Romillyi J. H. Jenkins) (1967). Dumbarton Oaks Center for Byzantine Studies. ISBN 0-88402-021-5.

مصادر ثانوية

- Atalay, Besim (2006). Divanü Lügati't - Türk. Türk Tarih Kurumu Basımevi. ISBN 975-16-0405-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Curta, Florin (2006). Southeastern Europe in the Middle Ages, 500-1250. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-89452-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Golden, Peter B. (2003). Nomads and their Neighbours in the Russian Steppe: Turks, Khazars and Quipchaqs. Ashgate. ISBN 0-86078-885-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Macartney, C. A. (1968). The Magyars in the Ninth Century. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-08070-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Pritsak, Omeljan (1975). "The Pechenegs: A Case of Social and Economic Transformation". Archivum Eurasiae Medii Aevi. The Peter de Ridder Press. 1: 211–235.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Róna-Tas, András (1999). Hungarians and Europe in the Early Middle Ages: An Introduction to Early Hungarian History (Translated by Nicholas Bodoczky). CEU Press. ISBN 978-963-9116-48-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Spinei, Victor (2003). The Great Migrations in the East and South East of Europe from the Ninth to the Thirteenth Century (Translated by Dana Badulescu). ISBN 973-85894-5-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Spinei, Victor (2009). The Romanians and the Turkic Nomads North of the Danube Delta from the Tenth to the Mid-Thirteenth century. Koninklijke Brill NV. ISBN 978-90-04-17536-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

للاستزادة

- (بالروسية) Golubovsky Peter V. (1884) Pechenegs, Torks and Cumans before the invasion of the Tatars. History of the South Russian steppes 9th-13th centuries (Печенеги, Торки и Половцы до нашествия татар. История южно-русских степей IX—XIII вв.) at Runivers.ru in DjVu format

- Pálóczi-Horváth, A. (1989). Pechenegs, Cumans, Iasians: Steppe peoples in medieval Hungary. Hereditas. Budapest: Kultúra [distributor]. ISBN 963-13-2740-X

- Pritsak, O. (1976). The Pečenegs: a case of social and economic transformation. Lisse, Netherlands: The Peter de Ridder Press.

وصلات خارجية

- CS1 errors: unsupported parameter

- Pages using infobox country with unknown parameters

- Pages using Lang-xx templates

- Articles containing رومانية-language text

- Articles containing روسية-language text

- Articles containing أوكرانية-language text

- Articles containing مجرية-language text

- Articles containing كرواتية-language text

- Articles containing Greek-language text

- Articles containing جورجية-language text

- Articles containing بلغارية-language text

- Articles containing صربية-language text

- Articles containing لاتينية-language text

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Articles containing تركمانية-language text

- دول توركية تاريخية

- أسر توركية

- تاريخ الشعوب التوركية

- شعوب توركية

- قبائل توركية

- روس الكييڤية

- جماعات بدوية في أوراسيا

- پچنگ

- مولدوڤا في العصور الوسطى المبكرة

- رومانيا في العصور الوسطى المبكرة

- قبائل العصر البيزنطي المتأخر في البلقان