الخط البراهمي

| Brāhmī Lipi 𑀩𑁆𑀭𑀸𑀳𑁆𑀫𑀻 𑀮𑀺𑀧𑀺 | |

|---|---|

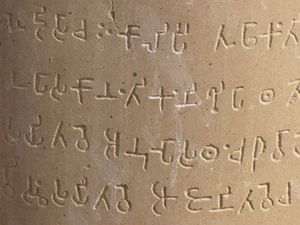

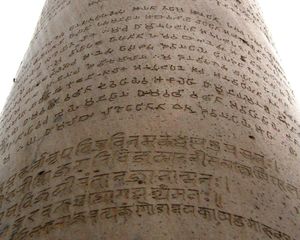

Brahmi script an Ashoka Pillar (circa 250 BCE). | |

| النوع | |

| اللغات | Sanskrit, Prakrit, Tamil, Saka, Tocharian |

| الفترة الزمنية | 4th century BCE[1][a] to 5th century CE[2] |

النظم الوالدة | Proto-Sinaitic script[b]

|

النظم الابنة | Gupta and numerous descendant writing systems |

النظم الشقيقة | Kharoṣṭhī |

| الاتجاه | Left-to-right |

| ISO 15924 | Brah, 300 |

مرادف اليونيكود | Brahmi |

| U+11000–U+1107F | |

[a] Recent claims of earlier fragmentary inscriptions on potsherds are still disputed: see Brahmi script#Date [b] The Semitic origin of the Brahmic scripts is not universally agreed upon. | |

Brahmi (/ˈbrɑːmi/; IAST: Brāhmī), developed in the mid-1st millennium BCE, is the oldest known writing system of Ancient India, with the possible exception of the undeciphered Indus script.[3] Brahmi is an abugida that thrived in the Indian subcontinent and uses a system of diacritical marks to associate vowels with consonant symbols. It evolved into a host of other scripts, called the Brahmic scripts, that continue to be in use today in South and Central Asia.[4][5][6]

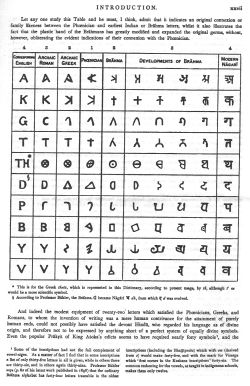

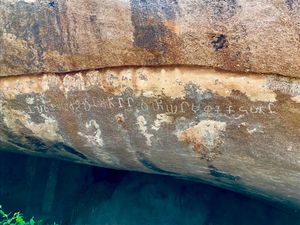

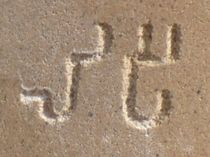

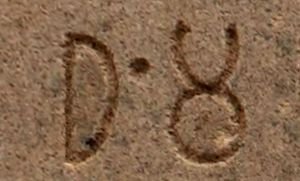

The Brahmi script has been dated to the beginning of the 4th century BCE from sherds inscribed with the script found at Anuradhapura.[2] Some of the earliest and best-known Brahmi inscriptions are the rock-cut edicts of Ashoka in north-central India, dating to 250–232 BCE. The first successful attempts at deciphering Brahmi were made in 1836 by Norwegian scholar Christian Lassen, who used the bilingual Greek-Brahmi coins of Indo-Greek kings Agathocles and Pantaleon to correctly identify several Brahmi letters.[7] The script was fully deciphered in 1837 by James Prinsep, an archaeologist, philologist, and official of the East India Company, with the help of Alexander Cunningham.[8][7][9] The origin of the script is still much debated, with some scholars stating that Brahmi was derived from or at least influenced by one or more contemporary Semitic scripts, while others favor the idea of an indigenous origin or connection to the much older and as-yet undeciphered Indus script of the Indus Valley Civilization.[10][11]

Brahmi was at one time referred to in English as the "pin-man" script,[12] that is "stick figure" script. It was known by a variety of other names[13] until the 1880s when Albert Étienne Jean Baptiste Terrien de Lacouperie, based on an observation by Gabriel Devéria, associated it with the Brahmi script, the first in a list of scripts mentioned in the Lalitavistara Sūtra. Thence the name was adopted in the influential work of Georg Bühler, albeit in the variant form "Brahma".[14] The Gupta script of the fifth century is sometimes called "Late Brahmi".

The Brahmi script diversified into numerous local variants classified together as the Brahmic scripts. Dozens of modern scripts used across South Asia have descended from Brahmi, making it one of the world's most influential writing traditions.[15] One survey found 198 scripts that ultimately derive from it.[16] The script was associated with its own Brahmi numerals, which ultimately provided the graphic forms for the Hindu–Arabic numeral system now used through most of the world.[17]

النصوص

The Brahmi script is mentioned in the ancient Indian texts of Hinduism, Jainism and Buddhism, as well as their Chinese translations.[18][19] For example, the Lipisala samdarshana parivarta lists 64 lipi (scripts), with the Brahmi script starting the list. The Lalitavistara Sūtra states that young Siddhartha, the future Gautama Buddha (~500 BCE), mastered philology, Brahmi and other scripts from the Brahmin Lipikāra and Deva Vidyāiṃha at a school.[20][18]

A shorter list of eighteen ancient scripts is found in the texts of Jainism, such as the Pannavana Sutra (2nd century BCE) and the Samavayanga Sutra (3rd century BCE).[21][22] These Jaina script lists include Brahmi at number 1 and Kharoṣṭhi at number 4 but also Javanaliya (probably Greek) and others not found in the Buddhist lists.[22]

الأصول

While the contemporary Kharoṣṭhī script is widely accepted to be a derivation of the Aramaic alphabet, the genesis of the Brahmi script is less straightforward. Salomon reviewed existing theories in 1998,[4] while Falk provided an overview in 1993.[23]

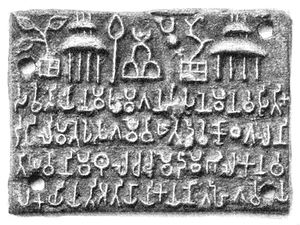

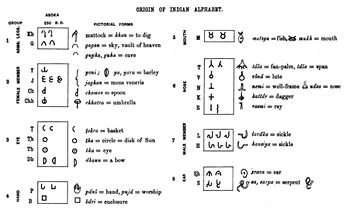

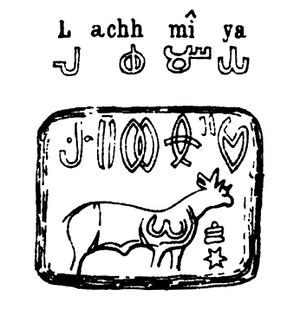

Early theories proposed a pictographic-acrophonic origin for the Brahmi script, on the model of the Egyptian hieroglyphic script. These ideas however have lost credence, as they are "purely imaginative and speculative".[24] Similar ideas have tried to connect the Brahmi script with the Indus script, but they remain unproven, and particularly suffer from the fact that the Indus script is as yet undeciphered.[24]

Semitic model hypothesis

James Prinsep, known for deciphering Brahmi in the early 19th century, was first to propose a connection between Indian scripts and Greek. He suggested that the oldest Greek was a "topsy-turvy" version of an ancient Indian language.[28] K. Ottfried Muller reversed this proposal suggesting that Brahmi was derived from Greek after the arrival of Alexander the Great.[28]

Bühler's theory

According to the Semitic hypothesis as laid out by Bühler in 1898, the oldest Brahmi inscriptions were derived from a Phoenician prototype.[29][note 1] Salomon states Bühler's arguments are "weak historical, geographical, and chronological justifications for a Phoenician prototype". Discoveries made since Bühler's proposal, such as of six Mauryan inscriptions in Aramaic, suggest Bühler's proposal about Phoenician as weak. It is more likely that Aramaic, which was virtually certain the prototype for Kharoṣṭhī, also may have been the basis for Brahmi. However, it is unclear why the ancient Indians would have developed two very different scripts.[31]

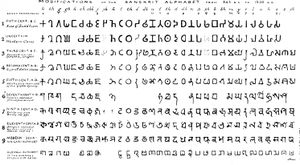

According to Bühler, Brahmi added symbols for certain sounds not found in Semitic languages, and either deleted or repurposed symbols for Aramaic sounds not found in Prakrit. For example, Aramaic lacks the phonetic retroflex feature that appears among Prakrit dental stops, such as ḍ, and in Brahmi the symbols of the retroflex and non-retroflex consonants are graphically very similar, as if both had been derived from a single prototype. (See Tibetan alphabet for a similar later development.) Aramaic did not have Brahmi's aspirated consonants (kh, th, etc.), whereas Brahmi did not have Aramaic's emphatic consonants (q, ṭ, ṣ), and it appears that these unneeded emphatic letters filled in for some of Brahmi's aspirates: Aramaic q for Brahmi kh, Aramaic ṭ (Θ) for Brahmi th (ʘ), etc. And just where Aramaic did not have a corresponding emphatic stop, p, Brahmi seems to have doubled up for the corresponding aspirate: Brahmi p and ph are graphically very similar, as if taken from the same source in Aramaic p. Bühler saw a systematic derivational principle for the other aspirates ch, jh, ph, bh, and dh, which involved adding a curve or upward hook to the right side of the character (which has been speculated to derive from h, ![]() ), while d and ṭ (not to be confused with the Semitic emphatic ṭ) were derived by back formation from dh and ṭh.[32]

), while d and ṭ (not to be confused with the Semitic emphatic ṭ) were derived by back formation from dh and ṭh.[32]

The following table lists the correspondences between Brahmi and North Semitic scripts.[33][34]

| Phoenician | Aramaic | Value | Brahmi | Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| * | a | |||

| b [b] | ba | |||

| g [ɡ] | ga | |||

| d [d] | dha | |||

| h [h], M.L. | ha | |||

| w [w], M.L. | va | |||

| z [z] | ja | |||

| ḥ [ħ] | gha | |||

| ṭ [tˤ] | tha | |||

| y [j], M.L. | ya | |||

| k [k] | ka | |||

| l [l] | la | |||

| m [m] | ma | |||

| n [n] | na | |||

| s [s] | ṣa | |||

| ʿ [ʕ], M.L. | e | |||

| p [p] | pa | |||

| ṣ [sˤ] | ca | |||

| q [q] | kha | |||

| r [r] | ra | |||

| š [ʃ] | śa | |||

| t [t] | ta |

Bühler states that both Phoenician and Brahmi had three voiceless sibilants, but because the alphabetical ordering was lost, the correspondences among them are not clear. Bühler was able to suggest Brahmi derivatives corresponding to all of the 22 North Semitic characters, though clearly, as Bühler himself recognized, some are more confident than others. He tended to place much weight on phonetic congruence as a guideline, for example connecting c ![]() to tsade

to tsade ![]() rather than kaph

rather than kaph ![]() , as preferred by many of his predecessors.

, as preferred by many of his predecessors.

One of the key problems with a Phoenician derivation is the lack of evidence for historical contact with Phoenicians in the relevant period.[31] Bühler explained this by proposing that the initial borrowing of Brahmi characters dates back considerably earlier than the earliest known evidence, as far back as 800 BCE, contemporary with the Phoenician glyph forms that he mainly compared. Bühler cited a near-modern practice of writing Brahmic scripts informally without vowel diacritics as a possible continuation of this earlier abjad-like stage in development.[36]

The weakest forms of the Semitic hypothesis are similar to Gnanadesikan's trans-cultural diffusion view of the development of Brahmi and Kharoṣṭhī, in which the idea of alphabetic sound representation was learned from the Aramaic-speaking Persians, but much of the writing system was a novel development tailored to the phonology of Prakrit.[37]

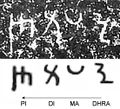

Another evidence cited in favor of Persian influence has been the Hultzsch proposal in 1925 that the Prakrit/Sanskrit word for writing itself, lipi is similar to the Old Persian word dipi, suggesting a probable borrowing.[38][39] A few of the Ashoka edicts from the region nearest the Persian empire use dipi as the Prakrit word for writing, which appears as lipi elsewhere, and this geographic distribution has long been taken, at least back to Bühler's time, as an indication that the standard lipi form is a later alteration that appeared as it diffused away from the Persian sphere of influence. Persian dipi itself is thought to be an Elamite loanword.[40]

Falk's theory

Falk's 1993 book Schrift im Alten Indien is considered a definitive study on writing in ancient India.[41][42] Falk's section on the origins of the Brahmi script[23] features an extensive review of the literature up to that time. Falk also puts forth his own ideas. As have a number of other authors, Falk sees the basic writing system of Brahmi as being derived from the Kharoṣṭhī script, itself a derivative of Aramaic. At the time of his writing, the Ashoka edicts were the oldest confidently dateable examples of Brahmi, and he perceives in them "a clear development in language from a faulty linguistic style to a well honed one"[43] over time, which he takes to indicate that the script had been recently developed.[23][44] Falk deviates from the mainstream of opinion in seeing Greek as also being a significant source for Brahmi. On this point particularly, Salomon disagrees with Falk, and after presenting evidence of very different methodology between Greek and Brahmi notation of vowel quantity, he states "it is doubtful whether Brahmi derived even the basic concept from a Greek prototype".[28] Further, adds Salomon, in a "limited sense Brahmi can be said to be derived from Kharosthi, but in terms of the actual forms of the characters, the differences between the two Indian scripts are much greater than the similarities".[45]

Falk also dated the origin of Kharoṣṭhī to no earlier than 325 BCE, based on a proposed connection to the Greek conquest.[46] Salomon questions Falk's arguments as to the date of Kharoṣṭhī and writes that it is "speculative at best and hardly constitutes firm grounds for a late date for Kharoṣṭhī. The stronger argument for this position is that we have no specimen of the script before the time of Ashoka, nor any direct evidence of intermediate stages in its development; but of course this does not mean that such earlier forms did not exist, only that, if they did exist, they have not survived, presumably because they were not employed for monumental purposes before Ashoka".[44]

Obv Balarama-Samkarshana with Greek legend: ΒΑΣΙΛΕΩΣ ΑΓΑΘΟΚΛΕΟΥΣ.

Rev Vasudeva-Krishna with Brahmi legend:𑀭𑀸𑀚𑀦𑁂 𑀅𑀕𑀣𑀼𑀓𑁆𑀮𑀬𑁂𑀲 Rājane Agathukleyesa "King Agathocles". Circa 180 BCE.

Unlike Bühler, Falk does not provide details of which and how the presumptive prototypes may have been mapped to the individual characters of Brahmi. Further, states Salomon, Falk accepts there are anomalies in phonetic value and diacritics in Brahmi script that are not found in the presumed Kharoṣṭhī script source. Falk attempts to explain these anomalies by reviving the Greek influence hypothesis, a hypothesis that had previously fallen out of favor.[44][50]

Hartmut Scharfe, in his 2002 review of Kharoṣṭī and Brāhmī scripts, concurs with Salomon's questioning of Falk's proposal, and states, "the pattern of the phonemic analysis of the Sanskrit language achieved by the Vedic scholars is much closer to the Brahmi script than the Greek alphabet".[11]

Indigenous origin theory

The idea of an indigenous origin such as a connection to the Indus script is supported by some Western and Indian scholars and writers. The theory that there are similarities to the Indus script was suggested by early European scholars such as the Cambridge University archaeologist John Marshall[51] and the Oxford University professor Stephen Langdon,[52] and it continues to be suggested by scholars and writers such as (among others) the computer scientist Subhash Kak, the German Indologist Georg Feuerstein, the American teacher David Frawley, the British archaeologist Raymond Allchin, and the Cambridge University professor Jack Goody.[53][54][55]

Another form of the indigenous origin theory is that Brahmi was invented ex nihilo, entirely independently from either Semitic models or the Indus script, though Salomon found these theories to be wholly speculative in nature.[56]

Foreign origination

𑀮La+𑀺i; pī=𑀧Pa+𑀻ii). The word would be of Old Persian origin ("Dipi").Pāṇini (6th to 4th century BCE) mentions lipi, the Indian word for writing scripts in his definitive work on Sanskrit grammar, the Ashtadhyayi. According to Scharfe, the words lipi and libi are borrowed from the Old Persian dipi, in turn derived from Sumerian dup.[39][57] To describe his own Edicts, Ashoka used the word Lipī, now generally simply translated as "writing" or "inscription". It is thought the word "lipi", which is also orthographed "dipi" in the two Kharosthi-version of the rock edicts,[note 3] comes from an Old Persian prototype dipî also meaning "inscription", which is used for example by Darius I in his Behistun inscription,[note 4] suggesting borrowing and diffusion.[58][59][60]

Issues with current theories on Brahmi script origins

أصل الاسم

Several divergent accounts of the origin of the name "Brahmi" appear in history and legend. Several Sutras of Jainism such as the Vyakhya Pragyapti Sutra, the Samvayanga Sutra and the Pragyapna Sutra of the Jain Agamas include a list of 18 writing scripts known to teachers before the Mahavira was born, with the Brahmi script (bambhī in the original Prakrit) leading all these lists. The Brahmi script is missing from the 18 script list in the surviving versions of two later Jaina Sutras, namely the Vishesha Avashyaka and the Kalpa Sutra. Jain legend recounts that 18 writing scripts were taught by their first Tirthankara Rishabhanatha to his daughter Brahmi, she emphasized Brahmi as the main script as she taught others, and therefore the name Brahmi for the script comes after her name.[61]

A Chinese Buddhist account of the 6th century CE attributes its creation to the god Brahma, though Monier Monier-Williams, Sylvain Lévi and others thought it was more likely to have been given the name because it was moulded by the Brahmins.[62][63]

The term Brahmi appears in ancient Indian texts in different contexts. According to the rules of the Sanskrit language, it is a feminine word which literally means "of Brahma" or "the female energy of the Brahman".[64] In other texts such as the Mahabharata, it appears in the sense of a goddess, particularly for Saraswati as the goddess of speech and elsewhere as "personified Shakti (energy) of Brahma".[65]

التاريخ

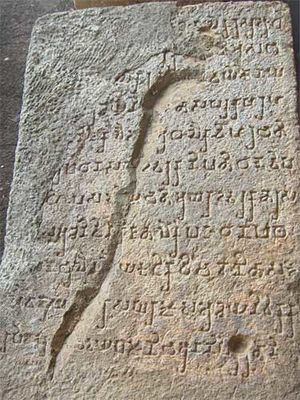

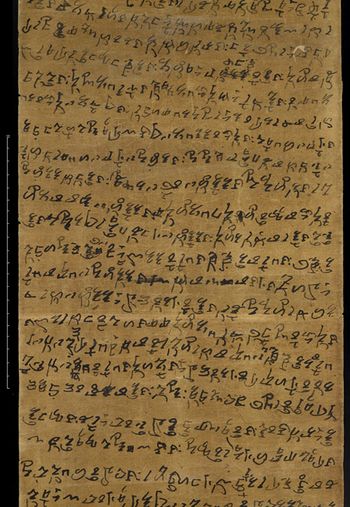

The earliest known full inscriptions of Brahmi are in Prakrit, dated to be from 3rd to 1st-century BCE, particularly the Edicts of Ashoka, c. 250 BCE.[66] Prakrit records predominate the epigraphic records discovered in the Indian subcontinent through about 1st-century CE.[66] The earliest known Brahmi inscriptions in Sanskrit are from the 1st-century BCE, such as the few discovered in Ayodhya, Ghosundi and Hathibada (both near Chittorgarh).[67][note 5] Ancient inscriptions have also been discovered in many North and Central Indian sites, occasionally in South India as well, that are in hybrid Sanskrit-Prakrit language called "Epigraphical Hybrid Sanskrit".[note 6] These are dated by modern techniques to between 1st and 4th-century CE.[70][71] Surviving ancient records of the Brahmi script are found as engravings on pillars, temple walls, metal plates, terra-cotta, coins, crystals and manuscripts.[72][71]

فك الرموز

Besides a few inscriptions in Greek and Aramaic (which were only discovered in the 20th century), the Edicts of Ashoka were written in the Brahmi script and sometimes in the Kharoshthi script in the northwest, which had both become extinct around the 4th century CE, and were yet undeciphered at the time the Edicts were discovered and investigated in the 19th century.[74][7]

البحر الأحمر وجنوب شرق آسيا

The Khuan Luk Pat inscription discovered in تايلند is in Tamil Brahmi script. Its date is uncertain and has been proposed to be from the early centuries of the common era.[75][76] According to Frederick Asher, Tamil Brahmi inscriptions on postherds have been found in Quseir al-Qadim and in Berenike, Egypt which suggest that merchant and trade activity was flourishing in ancient times between India and the Red Sea region.[76] Additional Tamil Brahmi inscription has been found in Khor Rori region of Oman on an archaeological site storage jar.[76]

السمات

Brahmi is usually written from left to right, as in the case of its descendants. However, an early coin found in Eran is inscribed with Brahmi running from right to left, as in Aramaic. Several other instances of variation in the writing direction are known, though directional instability is fairly common in ancient writing systems.[77]

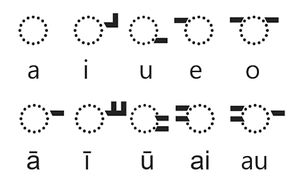

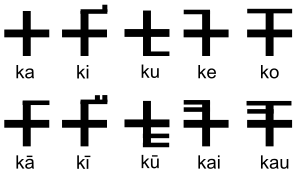

Consonants

Brahmi is an abugida, meaning that each letter represents a consonant, while vowels are written with obligatory diacritics called mātrās in Sanskrit, except when the vowels commence a word. When no vowel is written, the vowel /a/ is understood. This "default short a" is a characteristic shared with Kharosthī, though the treatment of vowels differs in other respects.

Conjunct consonants

Special conjunct consonants are used to write consonant clusters such as /pr/ or /rv/. In modern Devanagari the components of a conjunct are written left to right when possible (when the first consonant has a vertical stem that can be removed at the right), whereas in Brahmi characters are joined vertically downwards.

Vowels

Punctuation

الحروف

Vowels

| Letter | Mātrā (with ka) |

IAST and Sanskrit IPA |

Letter | Mātrā (with ka) |

IAST and Sanskrit IPA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 𑀅 | 𑀓 | a /ə/ | 𑀆 | 𑀓𑀸 | ā /aː/ |

| 𑀇 | 𑀓𑀺 | i /i/ | 𑀈 | 𑀓𑀻 | ī /iː/ |

| 𑀉 | 𑀓𑀼 | u /u/ | 𑀊 | 𑀓𑀽 | ū /uː/ |

| 𑀋 | 𑀓𑀾 | ṛ /r̩/ | 𑀌 | 𑀓𑀿 | ṝ /r̩ː/ |

| 𑀍 | 𑀓𑁀 | l̩ /l̩/ | 𑀎 | 𑀓𑁁 | ḹ /l̩ː/ |

| 𑀏 | 𑀓𑁂 | e /eː/ | 𑀐 | 𑀓𑁃 | ai /əi/ |

| 𑀑 | 𑀓𑁄 | o /oː/ | 𑀒 | 𑀓𑁅 | au /əu/ |

Consonants

| Stop | Nasal | Approximant | Fricative | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Voicing → | Voiceless | Voiced | Voiceless | Voiced | ||||||||||||

| Aspiration → | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | ||||||||||

| Velar | 𑀓 | ka /k/ | 𑀔 | kha /kʰ/ | 𑀕 | ga /g/ | 𑀖 | gha /ɡʱ/ | 𑀗 | ṅa /ŋ/ | 𑀳 | ha /ɦ/ | ||||

| Palatal | 𑀘 | ca /c/ | 𑀙 | cha /cʰ/ | 𑀚 | ja /ɟ/ | 𑀛 | jha /ɟʱ/ | 𑀜 | ña /ɲ/ | 𑀬 | ya /j/ | 𑀰 | śa /ɕ/ | ||

| Retroflex | 𑀝 | ṭa /ʈ/ | 𑀞 | ṭha /ʈʰ/ | 𑀟 | ḍa /ɖ/ | 𑀠 | ḍha /ɖʱ/ | 𑀡 | ṇa /ɳ/ | 𑀭 | ra /r/ | 𑀱 | ṣa /ʂ/ | ||

| Dental | 𑀢 | ta /t̪/ | 𑀣 | tha /t̪ʰ/ | 𑀤 | da /d̪/ | 𑀥 | dha /d̪ʱ/ | 𑀦 | na /n/ | 𑀮 | la /l/ | 𑀲 | sa /s/ | ||

| Labial | 𑀧 | pa /p/ | 𑀨 | pha /pʰ/ | 𑀩 | ba /b/ | 𑀪 | bha /bʱ/ | 𑀫 | ma /m/ | 𑀯 | va /w, ʋ/ | ||||

The final letter does not fit into the table above; it is 𑀴 ḷa.

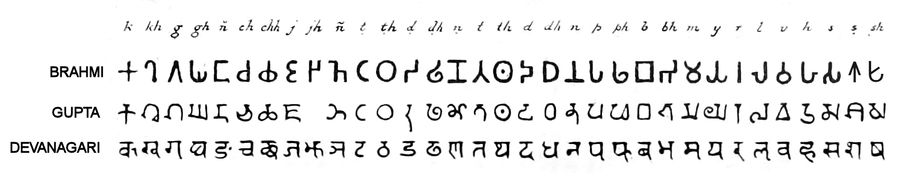

Descendants

Over the course of a millennium, Brahmi developed into numerous regional scripts, commonly classified into a more rounded Southern India group and a more angular Northern India group. Over time, these regional scripts became associated with the local languages. A Northern Brahmi gave rise to the Gupta script during the Gupta Empire, sometimes also called "Late Brahmi" (used during the 5th century), which in turn diversified into a number of cursives during the Middle Ages, including the Siddhaṃ script (6th century), Śāradā script (9th century) and Devanagari (10th century).

Southern Brahmi gave rise to the Grantha alphabet (6th century), the Vatteluttu alphabet (8th century), and due to the contact of Hinduism with Southeast Asia during the early centuries CE, also gave rise to the Baybayin in the Philippines, the Javanese script in Indonesia, the Khmer alphabet in Cambodia, and the Old Mon script in Burma.

Also in the Brahmic family of scripts are several Central Asian scripts such as Tibetan, Tocharian (also called slanting Brahmi), and the one used to write the Saka language.

يونيكود والرقمنة

Brahmi was added to the Unicode Standard in October, 2010 with the release of version 6.0.

The Unicode block for Brahmi is U+11000–U+1107F. It lies within Supplementary Multilingual Plane. As of August 2014 there are two non-commercially available fonts that support Brahmi, namely Noto Sans Brahmi commissioned by Google which covers all the characters,[79] and Adinatha which only covers Tamil Brahmi.[80] Segoe UI Historic, tied in with Windows 10, also features Brahmi glyphs.[81]

The Sanskrit word for Brahmi, ब्राह्मी (IAST Brāhmī) in the Brahmi script should be rendered as follows: 𑀩𑁆𑀭𑀸𑀳𑁆𑀫𑀻.

بعض النقوش الشهيرة بالخط البراهمي

The Brahmi script was the medium for some of the most famous inscriptions of ancient India, starting with the Edicts of Ashoka, circa 250 BCE.

مسقط رأس بوذا التاريخي

في المرسوم ذائع الصيت، مرسوم رومـِّندِيْ في لومبيني، نـِپال، يصف أشوكا زيارته في السنة 21 من عهده، ويصف لومبيني بأنها مسقط رأس البوذا. He also, for the first time in historical records, uses the epithet "Sakyamuni" (Sage of the Shakyas)، لوصف بوذا.[82]

| الترجمة (العربية) |

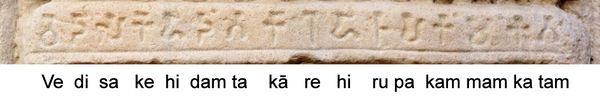

النسخ الحرفي (الخط البراهمي الأصلي) |

النقش (پراكريت بالخط البراهمي) |

|---|---|---|

|

|

مرسوم عمود رومـِّندِيْ في لومبيني. |

نقوش عمود هليودورس

| الترجمة (العربية) |

النسخ اللفظي (الخط البراهمي الأصلي) |

النقش (پراكريت بالخط البراهمي)[85] |

|---|---|---|

|

This Garuda-standard of Vāsudeva, the God of Gods Three immortal precepts (footsteps)... when practiced |

|

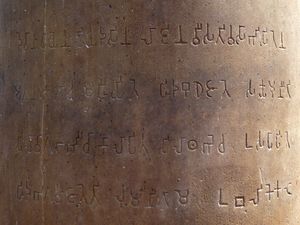

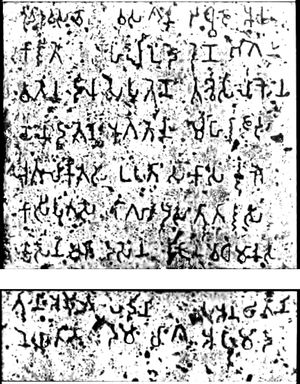

Heliodorus pillar rubbing (inverted colors). The text is in the Brahmi script of the Sunga period.[89] For a recent photograph. |

نقوش أخرى

انظر أيضاً

ملاحظات

- ^ Aramaic is written from right to left, as are several early examples of Brahmi.[30][صفحة مطلوبة] For example, Brahmi and Aramaic g (

and

and  ) and Brahmi and Aramaic t (

) and Brahmi and Aramaic t ( and

and  ) are nearly identical, as are several other pairs. Bühler also perceived a pattern of derivation in which certain characters were turned upside down, as with pe

) are nearly identical, as are several other pairs. Bühler also perceived a pattern of derivation in which certain characters were turned upside down, as with pe  and

and  pa, which he attributed to a stylistic preference against top-heavy characters.

pa, which he attributed to a stylistic preference against top-heavy characters.

- ^ Bühler notes that other authors derive

(cha) from qoph. "M.L." indicates that the letter was used as a mater lectionis in some phase of Phoenician or Aramaic. The matres lectionis functioned as occasional vowel markers to indicate medial and final vowels in the otherwise consonant-only script. Aleph

(cha) from qoph. "M.L." indicates that the letter was used as a mater lectionis in some phase of Phoenician or Aramaic. The matres lectionis functioned as occasional vowel markers to indicate medial and final vowels in the otherwise consonant-only script. Aleph  and particularly ʿayin

and particularly ʿayin  only developed this function in later phases of Phoenician and related scripts, though

only developed this function in later phases of Phoenician and related scripts, though  also sometimes functioned to mark an initial prosthetic (or prothetic) vowel from a very early period.[35]

also sometimes functioned to mark an initial prosthetic (or prothetic) vowel from a very early period.[35]

- ^ For example, according to Hultzsch, the first line of the First Edict at Shahbazgarhi (or at Mansehra) reads: "(Ayam) Dhrama-dipi Devanapriyasa Raño likhapitu" ("This Dharma-Edicts was written by King Devanampriya" Inscriptions of Asoka. New Edition by E. Hultzsch (in Sanskrit). 1925. p. 51.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link)

This appears in the reading of Hultzsch's original rubbing of the Kharoshthi inscription of the first line of the First Edict at Shahbazgarhi (here attached, which reads "Di" rather than "Li"

rather than "Li"  ).

).

- ^ For example Column IV, Line 89

- ^ More numerous inscribed Sanskrit records in Brahmi have been found near Mathura and elsewhere, but these are from the 1st century CE onwards.[68]

- ^ The archeological sites near the northern Indian city of Mathura has been one of the largest source of such ancient inscriptions. Andhau (Gujarat) and Nasik (Maharashtra) are other important sources of Brahmi inscriptions from the 1st-century CE.[69]

المراجع

- ^ Salomon 1998, pp. 11-13.

- ^ أ ب Coningham, R. a. E.; Allchin, F. R.; Batt, C. M.; Lucy, D. (1996). "Passage to India? Anuradhapura and the Early Use of the Brahmi Script". Cambridge Archaeological Journal (in الإنجليزية). 6 (1): 73–97. doi:10.1017/S0959774300001608. ISSN 1474-0540.

- ^ Brahmi, Encyclopedia Britannica (1999), Quote: "Brāhmī, writing system ancestral to all Indian scripts except Kharoṣṭhī. Of Aramaic derivation or inspiration, it can be traced to the 8th or 7th century BC, when it may have been introduced to Indian merchants by people of Semitic origin. (...) a coin of the 4th century BC, discovered in Madhya Pradesh, is inscribed with Brāhmī characters running from right to left."

- ^ أ ب Salomon 1998, pp. 19–30.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةSalomon 1995 - ^ Brahmi, Encyclopedia Britannica (1999), Quote: "Among the many descendants of Brāhmī are Devanāgarī (used for Sanskrit, Hindi, and other Indian languages), the Bengali and Gujarati scripts, and those of the Dravidian languages"

- ^ أ ب ت ث Ray, Himanshu Prabha (2017). Buddhism and Gandhara: An Archaeology of Museum Collections (in الإنجليزية). Taylor & Francis. p. 181. ISBN 9781351252744.

- ^ Asiatic Society of Bengal (1837). Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal (in English). Oxford University.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ More details about Buddhist monuments at Sanchi Archived 2011-07-21 at the Wayback Machine, Archaeological Survey of India, 1989.

- ^ Salomon 1998, p. 20.

- ^ أ ب Scharfe, Hartmut (2002). "Kharosti and Brahmi". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 122 (2): 391–393. doi:10.2307/3087634.

- ^ Keay 2000, p. 129–131.

- ^ including "lath", "Laṭ", "Southern Aśokan", "Indian Pali" or "Mauryan" (Salomon 1998, p. 17) harv error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFSalomon1998 (help)

- ^ Falk 1993, p. 106.

- ^ Rajgor 2007.

- ^ Trautmann 2006, p. 64.

- ^ Salomon 1998, pp. 56–63.

- ^ أ ب Georg Bühler (1898). On the Origin of the Indian Brahma Alphabet. K.J. Trübner. pp. 6, 14–15, 23, 29., Quote: "(...) a passage of the Lalitavistara which describes the first visit of Prince Siddhartha, the future Buddha, to the writing school..." (page 6); "In the account of Prince Siddhartha's first visit to the writing school, extracted by Professor Terrien de la Couperie from the Chinese translation of the Lalitavistara of 308 AD, there occurs besides the mention of the sixty-four alphabets, known also from the printed Sanskrit text, the utterance of the Master Visvamitra[.]"

- ^ Salomon 1998

- ^ Nado, Lopon (1982). "The Development of Language in Bhutan". The Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies. 5 (2): 95.

Under different teachers, such as the Brahmin Lipikara and Deva Vidyasinha, he mastered Indian philology and scripts. According to Lalitavistara, there were as many as sixty-four scripts in India.

- ^ Tsung-i, Jao (1964). "CHINESE SOURCES ON BRĀHMĪ AND KHAROṢṬHĪ". Annals of the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute. 45 (1/4): 39–47. doi:10.2307/41682442. JSTOR 41682442.

- ^ أ ب Salomon 1998, p. 9.

- ^ أ ب ت Falk 1993, pp. 109–167.

- ^ أ ب Salomon 1998, pp. 19–20

- ^ F. R. Allchin; George Erdosy (1995). The Archaeology of Early Historic South Asia: The Emergence of Cities and States. Cambridge University Press. pp. 309–310. ISBN 978-0-521-37695-2.

- ^ L. A. Waddell (1914), Besnagar Pillar Inscription B Re-Interpreted, The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, Cambridge University Press, pages 1031-1037

- ^ Epigraphia Indica Vol.18 p.328 Inscription No10

- ^ أ ب ت Salomon 1998, p. 22.

- ^ Bühler 1898, p. 59,68,71,75.

- ^ Salomon 1996.

- ^ أ ب Salomon 1998, p. 28.

- ^ Bühler 1898, p. 76-77.

- ^ Bühler 1898, p. 82-83.

- ^ أ ب Salomon 1998, p. 25.

- ^ Andersen, F.I.; Freedman, D.N. (1992). "Aleph as a vowel in Old Aramaic". Studies in Hebrew and Aramaic Orthography. Winona Lake, Indiana: Eisenbrauns. pp. 79–90.

- ^ Bühler 1898, p. 84–91.

- ^ Gnanadesikan, Amalia E. (2009), The Writing Revolution: Cuneiform to the Internet, John Wiley and Sons Ltd., pp. 173–174

- ^ Hultzsch, E. (1925). Corpus Inscriptionum Indicarum v. 1: Inscriptions of Asoka. Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. xlii. Retrieved 8 April 2015.

- ^ أ ب Scharfe, Hartmut (2002), Education in Ancient India, Handbook of Oriental Studies, Leiden, Netherlands: Brill Publishers, pp. 10–12

- ^ Tavernier, Jan (2007). "The Case of Elamite Tep-/Tip- and Akkadian Tuppu". Iran. 45: 57–69. Retrieved 8 April 2015.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةbronkhorst2002lar - ^ Falk 1993.

- ^ Annette Wilke & Oliver Moebus 2011, p. 194, footnote 421.

- ^ أ ب ت Salomon, Richard (1995). "Review: On the Origin of the Early Indian Scripts". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 115 (2): 271–278. doi:10.2307/604670.

- ^ Salomon 1998, pp. 23.

- ^ Falk 1993, pp. 104.

- ^ CNG Coins

- ^ Iravatham Mahadevan (2003). Early Tamil Epigraphy. Harvard University Department of Sanskrit and Indian Studies. pp. 91–94. ISBN 978-0-674-01227-1.;

Iravatham Mahadevan (1970). Tamil-Brahmi Inscriptions. State Department of Archaeology, Government of Tamil Nadu. pp. 1–12. - ^ Bertold Spuler (1975). Handbook of Oriental Studies. BRILL Academic. p. 44. ISBN 90-04-04190-7.

- ^ Salomon 1998, pp. 19–24.

- ^ John Marshall (1931). Mohenjo-daro and the Indus civilization: being an official account of archaeological excavations at Mohenjo-Daro carried out by the government of India between the years 1922 and 1927. Asian Educational Services. p. 423. ISBN 978-81-206-1179-5., Quote: "Langdon also suggested that the Brahmi script was derived from the Indus writing, (...)".

- ^ Senarat Paranavitana; Leelananda Prematilleka; Johanna Engelberta van Lohuizen-De Leeuw (1978). Studies in South Asian Culture: Senarat Paranavitana Commemoration Volume. BRILL Academic. p. 119. ISBN 90-04-05455-3.

- ^ Georg Feuerstein; Subhash Kak; David Frawley (2005). The Search of the Cradle of Civilization: New Light on Ancient India. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 136–137. ISBN 978-81-208-2037-1.

- ^ Jack Goody (1987). The Interface Between the Written and the Oral. Cambridge University Press. pp. 301 footnote 4. ISBN 978-0-521-33794-6., Quote: "In recent years, I have been leaning towards the view that the Brahmi script had an independent Indian evolution, probably emerging from the breakdown of the old Harappan script in the first half of the second millennium BC".

- ^ Salomon 1998, p. 21.

- ^ Masica 1993, p. 135.

- ^ Hultzsch, E. (1925). Corpus Inscriptionum Indicarum v. 1: Inscriptions of Asoka. Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. xlii.

- ^ Sharma, R. S. (2006). India's Ancient Past (in الإنجليزية). Oxford University Press. p. 163. ISBN 9780199087860.

- ^ "The word dipi appears in the Old Persian inscription of Darius I at Behistan (Column IV. 39) having the meaning inscription or "written document" in Congress, Indian History (2007). Proceedings - Indian History Congress (in الإنجليزية). p. 90.

- ^ Nagrajji, Acharya Shri (2003), Āgama Aura Tripiṭaka, Eka Anuśilana: Language and literature, New Delhi: Concept Publishing

- ^ Levi, Silvain (1906), "The Kharostra Country and the Kharostri Writing", The Indian Antiquary XXXV, https://books.google.com/books?id=GRwoAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA9

- ^ Monier Monier-Williams (1970). Sanskrit-English dictionary. Motilal Banarsidass (Reprint of Oxford Claredon). p. xxvi with footnotes. ISBN 978-5-458-25035-1.

- ^ Arthur Anthony Macdonell (2004). Sanskrit English Dictionary (Practical Hand Book). Asian Educational Services. p. 200. ISBN 978-81-206-1779-7.

- ^ Monier Monier Willians (1899), Brahmi, Oxford University Press, page 742

- ^ أ ب Salomon 1998, pp. 72-81.

- ^ Salomon 1998, pp. 86-87.

- ^ Salomon 1998, pp. 87-89.

- ^ Salomon 1998, p. 82.

- ^ Salomon 1998, pp. 81-84.

- ^ أ ب Salomon 1996, p. 377.

- ^ Salomon 1998, pp. 122-123, 129-131, 262-307.

- ^ Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal. Calcutta : Printed at the Baptist Mission Press [etc.] 1838.

- ^ Salomon 1998, pp. 204–206.

- ^ P Shanmugam (2009). Hermann Kulke; et al. (eds.). Nagapattinam to Suvarnadwipa: Reflections on the Chola Naval Expeditions to Southeast Asia. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. p. 208. ISBN 978-981-230-937-2.

- ^ أ ب ت Frederick Asher (2018). Matthew Adam Cobb (ed.). The Indian Ocean Trade in Antiquity: Political, Cultural and Economic Impacts. Taylor & Francis Group. p. 158. ISBN 978-1-138-73826-3.

- ^ Salomon 1998, pp. 27–28.

- ^ Chakrabarti, Manika (1981). Mālwa in Post-Maurya Period: A Critical Study with Special Emphasis on Numismatic Evidences (in الإنجليزية). Punthi Pustak. p. 100.

- ^ Google Noto Fonts – Download Noto Sans Brahmi zip file

- ^ Adinatha font announcement

- ^ Script and Font Support in Windows - Windows 10, MSDN Go Global Developer Center.

- ^ Hultzsch, E. /1925). Inscriptions of Asoka. Oxford: Clarendon Press, pp. 164-165

- ^ Hultzsch, E. (1925). Inscriptions of Asoka. Oxford: Clarendon Press, pp. 164-165

- ^ Hultzsch, E. (1925). Inscriptions of Asoka. New Edition by E. Hultzsch (in Sanskrit). p. 164.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ أ ب Greek Culture in Afghanistan and India: Old Evidence and New Discoveries Shane Wallace, 2016, p.222-223

- ^ Archaeological Survey of India, Annual report 1908-1909 p.129

- ^ Rapson, E. J. (1914). Ancient India. p. 157.

- ^ Sukthankar, Vishnu Sitaram, V. S. Sukthankar Memorial Edition, Vol. II: Analecta, Bombay: Karnatak Publishing House 1945 p.266

- ^ أ ب R. Salomon, Indian Epigraphy. A Guide to the Study of Inscriptions in Sanskrit, Prakrit, and the Other Indo-Aryan Languages (Oxford, 1998), 265–7

- ^ International Dunhuang Project. "Or.8212/162". British Library.

ببليوگرافيا

- Annette Wilke; Oliver Moebus (2011). Sound and Communication: An Aesthetic Cultural History of Sanskrit Hinduism. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-024003-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Bühler, Georg (1898). On the Origin of the Indian Brahma Alphabet.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Deraniyagala, Siran (2004). The Prehistory of Sri Lanka: An Ecological Perspective. Department of Archaeological Survey, Government of Sri Lanka. ISBN 978-955-9159-00-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Falk, Harry (1993). Schrift im alten Indien: ein Forschungsbericht mit Anmerkungen (in German). Gunter Narr Verlag.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - Gérard Fussman, Les premiers systèmes d'écriture en Inde, in Annuaire du Collège de France 1988–1989 (in French)

- Oscar von Hinüber, Der Beginn der Schrift und frühe Schriftlichkeit in Indien, Franz Steiner Verlag, 1990 (in German)

- Keay, John (2000). India: A History. Grove Press. ISBN 978-0-8021-3797-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Ledyard, Gari (1994). The Korean Language Reform of 1446: The Origin, Background, and Early History of the Korean Alphabet. University Microfilms.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Masica, Colin (1993). The Indo-Aryan Languages. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-29944-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Norman, Kenneth R. (1992). "The Development of Writing in India and its Effect upon the Pāli Canon". Wiener Zeitschrift für die Kunde Südasiens / Vienna Journal of South Asian Studies. 36 (Proceedings of the VIIIth World Sanskrit Conference Vienna): 239–249.

- Patel, Purushottam G.; Pandey, Pramod; Rajgor, Dilip (2007). The Indic Scripts: Palaeographic and Linguistic Perspectives. D.K. Printworld. ISBN 978-81-246-0406-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Rocher, Ludo (2014). Studies in Hindu Law and Dharmaśāstra. Anthem Press. ISBN 978-1-78308-315-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Salomon, Richard (1996). "Brahmi and Kharoshthi". The World's Writing Systems. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-507993-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|editors=ignored (|editor=suggested) (help) - Salomon, Richard (1998). Indian Epigraphy: A Guide to the Study of Inscriptions in Sanskrit, Prakrit, and the other Indo-Aryan Languages. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-535666-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Salomon, Richard (1995). "On the Origin of the Early Indian Scripts". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 115 (2): 271–279. doi:10.2307/604670. JSTOR 604670.

- Salomon, Richard (1998). Indian Epigraphy: A Guide to the Study of Inscriptions in Sanskrit, Prakrit, and the Other Indo-Aryan Languages. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-509984-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Trautmann, Thomas (2006). Languages and Nations: The Dravidian Proof in Colonial Madras. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-24455-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Timmer, Barbara Catharina Jacoba (1930). Megasthenes en de Indische maatschappij. H.J. Paris.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

وصلات خارجية

- "Brahmi Home". brahmi.sourceforge.net. of the Indian Institute of Science

- "Ancient Scripts: Brahmi". www.ancientscripts.com.

- "Brahmi Texts | Virtual Vinodh". www.virtualvinodh.com.

- Indoskript 2.0, a paleographic database of Brahmi and Kharosthi

- مقالات بالمعرفة بحاجة لذكر رقم الصفحة بالمصدر from March 2017

- Harv and Sfn multiple-target errors

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Missing redirects

- Scripts with ISO 15924 four-letter codes

- Pages with plain IPA

- All pages needing factual verification

- Wikipedia articles needing factual verification from October 2018

- CS1 errors: unsupported parameter

- التاريخ اللغوي للهند

- نظم كتابة لاغية

- خطوط براهمية

- Scripts encoded in Unicode 6.0