الثورة الفلپينية

| Philippine Revolution Himagsikang Pilipino | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||

| المتحاربون | |||||||

|

1896–1897

|

1896–1897 | ||||||

Naval support: |

1898 | ||||||

| القادة والزعماء | |||||||

|

Supremo: |

Queen Regent: Governor-Generals: (1896) (1896–1897) (1897–1898) (1898) (1898) (1898) Other leaders: | ||||||

| القوى | |||||||

| 40,000–60,000 (1896) Filipino Revolutionaries | 12,700–17,700 before the Revolution, around 55,000 (30,000 Spanish; 25,000 Filipino Loyalists) by 1898 | ||||||

| الضحايا والخسائر | |||||||

| Heavy; official casualties are unknown. | Heavy; official casualties are unknown. | ||||||

| جزء من سلسلة عن |

| ثورة |

|---|

|

|

|

The Philippine Revolution (Filipino: Himagsikang Pilipino; Spanish: Revolución Filipina), also called the Tagalog War (Spanish: Guerra Tagala, Filipino: Digmaang Tagalog) by the Spanish,[2] was a revolution and subsequent conflict fought between the people and insurgents of the Philippines and the Kingdom of Spain - including its Spanish Empire and Spanish colonial authorities in the Spanish East Indies.

The Philippine Revolution began in August 1896, when the Spanish authorities discovered the Katipunan, an anti-colonial secret organization. The Katipunan, led by Andrés Bonifacio, was a liberationist movement whose goal was independence from the 333 years of colonial control from Spain through armed revolt. The organization began to influence much of the Philippines. During a mass gathering in Caloocan, the leaders of the Katipunan organized themselves into a revolutionary government, named the newly established government "Haring Bayang Katagalugan", and openly declared a nationwide armed revolution.[3] Bonifacio called for an attack on the capital city of Manila. This attack failed; however, the surrounding provinces began to revolt. In particular, rebels in Cavite led by Mariano Álvarez and Emilio Aguinaldo (who were from two different factions of the Katipunan) won major early victories. A power struggle among the revolutionaries led to Bonifacio's death in 1897, with command shifting to Aguinaldo, who led the newly formed revolutionary government . That year, the revolutionaries and the Spanish signed the Pact of Biak-na-Bato, which temporarily reduced hostilities. Aguinaldo and other Filipino officers exiled themselves in the British colony of Hong Kong in southeast China. However, the hostilities never completely ceased.[4]

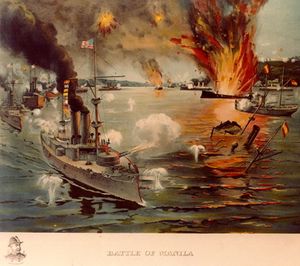

On April 21, 1898, after the sinking of يوإسإس Maine in Havana Harbor and prior to its declaration of war on April 25, the United States launched a naval blockade of the Spanish colony island of Cuba, off its southern coast of the peninsula of Florida. This was the first military action of the Spanish–American War of 1898.[5] On May 1, the U.S. Navy's Asiatic Squadron, under Commodore George Dewey, decisively defeated the Spanish Navy in the Battle of Manila Bay, effectively seizing control of Manila. On May 19, Aguinaldo, unofficially allied with the United States, returned to the Philippines and resumed attacks against the Spaniards. By June, the rebels had gained control of nearly all of the Philippines, with the exception of Manila. On June 12, Aguinaldo issued the Philippine Declaration of Independence.[6] Although this signified the end date of the revolution, neither Spain nor the United States recognized Philippine independence.[7]

The Spanish rule of the Philippines officially ended with the Treaty of Paris of 1898, which also ended the Spanish–American War. In the treaty, Spain ceded control of the Philippines and other territories to the United States.[4] There was an uneasy peace around Manila, with the American forces controlling the city and the weaker Philippines forces surrounding them.

On February 4, 1899, in the Battle of Manila, fighting broke out between the Filipino and American forces, beginning the Philippine–American War. Aguinaldo immediately ordered "[t]hat peace and friendly relations with the Americans be broken and that the latter be treated as enemies".[8] In June 1899, the nascent First Philippine Republic formally declared war against the United States.[9][10]

The Philippines would not become an internationally recognized independent state until 1946.

Opening of Manila to world trade

Before the opening of Manila to foreign trade, the Spanish authorities discouraged foreign merchants from residing in the colony and engaging in business.[11] The royal decree of February 2, 1800, prohibited foreigners from living in the Philippines.[12] as did the royal decrees of 1807 and 1816.[12] In 1823, Governor-General Mariano Ricafort promulgated an edict prohibiting foreign merchants from engaging in retail trade and visiting the provinces for the purpose of trading. It was reissued by Lardizábal in 1840.[13] A royal decree issued in 1844 prohibited foreigners from traveling to the provinces under any pretext whatsoever, and in 1857, several anti-foreigner laws were renewed.[14]

كاتيپونان

قالب:Katipunan Andrés Bonifacio, Deodato Arellano, Ladislao Diwa, Teodoro Plata and Valentín Díaz founded the Katipunan (in full, Kataas-taasang, Kagalang-galangang Katipunan ng mga Anak ng Bayan[15] "Supreme and Venerable Society of the Children of the Nation") in Manila on July 7, 1892. The organization, advocating independence through armed revolt against Spain, was influenced by the rituals and organization of Freemasonry; Bonifacio and other leading members were also Freemasons.

Course of the Revolution

Final Statement and Execution of José Rizal

When the revolution broke out, Rizal was in Cavite, awaiting the monthly mailboat to Spain. He had volunteered, and been accepted, for medical service in the Cuban War of Independence. The mailboat left on September 3 and arrived in Barcelona, which was under martial law, on October 3, 1896. After a brief confinement at Montjuich prison, Rizal was told by Captain-General Eulogio Despujol that he would not be going on to Cuba, but would be sent back to the Philippines instead. Upon his return, he was imprisoned in Fort Santiago.

Revolution in Cavite

By December, there were three major centers of rebellion: Cavite (under Mariano Alvarez, Baldomero Aguinaldo and others), Bulacan (under Mariano Llanera) and Morong (now part of Rizal, under Bonifacio). Bonifacio served as tactician for the rebel guerillas, though his prestige suffered when he lost battles that he personally led.[4]

Spanish–American War

In February, 1898, during an ongoing revolution in Cuba, the explosion and sinking of a U.S. Navy warship in Havana harbor led the United States to issue a declaration of war against Spain in April of that year. On April 25, Commodore George Dewey sailed for Manila with a fleet of seven U.S. ships. Upon arriving on May 1, Dewey encountered a fleet of twelve Spanish ships commanded by Admiral Patricio Montojo. The subsequent Battle of Manila Bay only lasted for a few hours, with all of Montojo's fleet destroyed. Dewey called for armed reinforcements and, while waiting, acted as a blockade for Manila Bay.[16][17]

Aguinaldo returns to the Philippines

On May 7, 1898, يوإسإس McCulloch, an American dispatch boat, arrived in Hong Kong from Manila, bringing reports of Dewey's victory in the Battle of Manila Bay, but with no orders regarding the transportation of Aguinaldo. McCulloch again arrived in Hong Kong on May 15, bearing orders to transport Aguinaldo to Manila. Aguinaldo departed Hong Kong aboard McCulloch on May 17, arriving in Manila Bay on May 19.[18] Several revolutionaries, as well as Filipino soldiers employed by the Spanish army, crossed over to Aguinaldo's command.

On May 28, 1898, with fresh reinforcements, about 12,000 men raided the last remaining stronghold of the Spanish Empire in Cavite in the Battle of Alapan. This battle eventually liberated Cavite from Spanish colonial control and led to the first time the modern flag of the Philippines being unfurled in victory.

Soon after, Imus and Bacoor in Cavite, Parañaque and Las Piñas in Morong, Macabebe, and San Fernando in Pampanga, as well as Laguna, Batangas, Bulacan, Nueva Ecija, Bataan, Tayabas (present-day Quezon), and the Camarines provinces, were liberated by the Filipinos. They were also able to capture the port of Dalahican in Cavite.

Declaration of Independence

By June 1898, the island of Luzon, except for Manila and the port of Cavite, was under Filipino control, after General Monet's retreat to Manila with his remaining force of 600 men and 80 wounded.[19] The revolutionaries were laying siege to Manila and cutting off its food and water supply. With most of the archipelago under his control, Aguinaldo decided it was time to establish a Philippine government. When Aguinaldo arrived from Hong Kong, he had brought with him a copy of a plan drawn by Mariano Ponce, calling for the establishment of a revolutionary government. Upon the advice of Ambrosio Rianzares Bautista, however, an autocratic regime was established on May 24, with Aguinaldo as dictator. It was under this dictatorship that independence was finally proclaimed on June 12, 1898, in Aguinaldo's house in Kawit, Cavite. The first Filipino flag was again unfurled and the national anthem was played for the first time. Apolinario Mabini, Aguinaldo's closest adviser, opposed Aguinaldo's decision to establish an autocracy. He instead urged Aguinaldo to create a revolutionary government. Aguinaldo refused to do so; however, Mabini was eventually able to convince him. Aguinaldo established a revolutionary government on July 23, 1898.

Capture of Manila

The United States Navy continued to wait for reinforcements. Refusing to allow the Filipinos to participate, reinforced U.S. forces captured Manila on August 13, 1898.

First Philippine Republic

Upon the recommendations of the decree that established the revolutionary government, a Congreso Revolucionario was assembled at Barasoain Church in Malolos, Bulacan on September 15.[19] All of the delegates to the congress were from the ilustrado class. Mabini objected to the call for a constitutional assembly; when he did not succeed, he drafted a constitution of his own, which also failed. A draft by an ilustrado lawyer, Felipe Calderón y Roca, was instead presented, and this became the framework upon which the assembly drafted the first constitution, the Malolos Constitution. On November 29, the assembly, now popularly called the Malolos Congress, finished the draft. However, Aguinaldo, who always placed Mabini in high esteem and heeded most of his advice, refused to sign the draft when the latter objected. On January 21, 1899, after some modifications were made to suit Mabini's arguments, the constitution was finally approved by the Congress and signed by Aguinaldo. Two days later, the Philippine Republic (also called the First Republic and Malolos Republic) was established in Malolos with Aguinaldo as president.[19]

Philippine–American War

On February 4, 1899, hostilities between Filipino and American forces began when an American sentry patrolling between Filipino and American lines shot a Filipino soldier. The Filipino forces returned fire, thus igniting a second battle for Manila. Aguinaldo sent a ranking member of his staff to Ellwell Otis, the U.S. military commander, with the message that the firing had been against his orders. According to Aguinaldo, Otis replied, "The fighting, having begun, must go on to the grim end."[20] The Philippines declared war against the United States on June 2, 1899, with Pedro Paterno, President of the Congress of the First Philippine Republic, issuing a Proclamation of War.[10]

As the First Philippine Republic was never recognized as a sovereign state, and the United States never formally declared war, the conflict was not concluded by a treaty. On July 2, 1902, the United States Secretary of War telegraphed that since the insurrection against the United States had ended and provincial civil governments had been established throughout most of the Philippine archipelago, the office of military governor was terminated.[21] On July 4, Theodore Roosevelt, who had succeeded to the U.S. Presidency after the assassination of William McKinley, proclaimed an amnesty to those who had participated in the conflict.[21][22] On April 9, 2002, Philippine President Gloria Macapagal Arroyo proclaimed that the Philippine–American War had ended on April 16, 1902 with the surrender of General Miguel Malvar,[23] and declared the centennial anniversary of that date as a national working holiday and as a special non-working holiday in the Province of Batangas and in the Cities of Batangas, Lipa and Tanauan.[24]

انظر أيضاً

- تاريخ الفلپين

- الجيش الثوري الفلپيني

- إعلان استقلال الفلپين

- كاتيپونان

- List of weapons of the Philippine revolution

- Battle of Pasong Tamo

- Battle of Imus

- Battle of Binakayan-Dalahican

- Battle of Alapan

- Negros Revolution

- جمهورية زامبوانگا

- حصار بالر

- الامبراطورية الاسبانية

- الإمبريالية الأمريكية

- تمرد المورو

Notes

- ^ If one includes the Spanish-American and Philippine-American wars in the period called the "Philippine Revolution", then 1902 would be the end date of that period. To avoid duplication between the Philippine Revolution and the Philippine–American War articles, this article treats the Philippine Revolution as having ended with the naval Mock Battle of Manila in 1898.

- ^ Bielakowski Ph.D., Alexander M. (January 2013). Ethnic and Racial Minorities in the U.S. Military: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-59884-427-6.

- ^ Guererro, Milagros; Encarnacion, Emmanuel; Villegas, Ramon (1996), "Andres Bonifacio and the 1896 Revolution", Sulyap Kultura (National Commission for Culture and the Arts) 1 (2): 3–12, http://www.ncca.gov.ph/about-culture-and-arts/articles-on-c-n-a/article.php?i=5&subcat=1

- ^ أ ب ت Custodio & Dalisay 1998.

- ^ Newton-Matza, Mitchell (March 2014). Disasters and Tragic Events: An Encyclopedia of Catastrophes in American History. ABC-CLIO. p. 165.

- ^ Marshall Cavendish Corporation (2007). World and Its Peoples: Malaysia, Philippines, Singapore, and Brunei. Marshall Cavendish. p. 1181.

- ^ Wesling, Meg (2011). Empire's Proxy: American Literature and U.S. Imperialism in the Philippines. NYU Press. p. 39.

- ^ Halstead 1898, p. 318

- ^ Kalaw 1927, pp. 199–200

- ^ أ ب Pedro Paterno's Proclamation of War, MSC Schools, Philippines, June 2, 1899, http://www.msc.edu.ph/centennial/pa990602.html, retrieved on 2007-10-17

- ^ Zaide 1957, p. 63

- ^ أ ب Montero y Vidal 1887, p. 360

- ^ Blair & Robertson 1903–1909, p. 10296

- ^ Blair & Robertson 1903–1909, p. 51071

- ^ The Project Gutenberg eBook: Kartilyang Makabayan.

- ^ Battle of Manila Bay, 1 May 1898, Department of the Navy — Naval Historical Center. Retrieved on October 10, 2007

- ^ The Battle of Manila Bay by Admiral George Dewey, The War Times Journal. Retrieved on October 10, 2007

- ^ Aguinaldo 1899 Chapter III.

- ^ أ ب ت خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةForeman - ^ Blanchard 1996, p. 130

- ^ أ ب Worcester 1914, p. 293.

- ^ "General amnesty for the Filipinos; proclamation issued by the President" (PDF). The New York Times. New York City. July 4, 1902.

- ^ "Speech of President Arroyo during the Commemoration of the Centennial Celebration of the end of the Philippine-American War April 16, 2002". Official Gazette. Government of the Philippines.

- ^ Macapagal Arroyo, Gloria (أبريل 9, 2002). "Proclamation No. 173. s. 2002". Manila: Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines. Archived from the original on ديسمبر 28, 2016. Retrieved ديسمبر 25, 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)

References

- Agoncillo, Teodoro C. (1990) [1960], History of the Filipino People (8th ed.), Quezon City: Garotech Publishing, ISBN 971-8711-06-6

- Aguinaldo y Famy, Emilio (1899), "Chapter II. The Treaty of Biak-na-bató", True Version of the Philippine Revolution, Authorama: Public Domain Books, http://www.authorama.com/true-version-of-the-philippine-revolution-3.html, retrieved on 2008-02-07

- Aguinaldo y Famy, Emilio (1899), "Chapter III. Negotiations", True Version of the Philippine Revolution, Authorama: Public Domain Books, http://www.authorama.com/true-version-of-the-philippine-revolution-4.html, retrieved on 2007-12-26

- Alvarez, S.V. (1992), Recalling the Revolution, Madison: Center for Southeast Asia Studies, University of Wisconsin-Madison, ISBN 1-881261-05-0

- Alvarez, Santiago V.; Malay, Paula Carolina S. (1992), The katipunan and the revolution: memoirs of a general: with the original Tagalog text, Ateneo de Manila University Press, ISBN 978-971-550-077-7, https://books.google.com/?id=F3q-krDckHwC, Translated by Paula Carolina S. Malay

- Anderson, Benedict (2005), Under Three Flags: Anarchism and the Anti-Colonial Imagination, London: Verso, ISBN 1-84467-037-6

- Batchelor, Bob (2002), The 1900s : American popular culture through history, Greenwood Publishing Group, ISBN 978-0-313-31334-9, https://books.google.com/?id=pepj7wZs-JEC

- Blanchard, William H. (1996), Neocolonialism American Style, 1960–2000 (illustrated ed.), Greenwood Publishing Group, ISBN 978-0-313-30013-4, https://books.google.com/?id=d42R23Jq6SMC

- Blair, Emma; Robertson, James (1903–1909), The Philippine Islands, 1493–1898, 1-55, Cleveland

- Bowring, Sir John (1859), A Visit to the Philippine Islands, London: Smith, Elder and Co.

- Constantino, Renato (1975), The Philippines: A Past Revisited, Self-published, Tala Pub. Services, https://books.google.com/?id=Q1ZxAAAAMAAJ

- de Moya, Francisco Javier (1883) (in Spanish), Las Islas Filipinas en 1882, 1–55, Madrid

- Dav, Chaitanya (2007), Crimes Against Humanity: A Shocking History of U.s. Crimes Since 1776, AuthorHouse, ISBN 978-1-4343-0181-9, https://books.google.com/?id=pS7MUfZ7FKcC

- Díaz Arenas, Rafaél (1838) (in Spanish), Memoria sobre el comercio y navegacion de las islas Filipinas, Cádiz, Spain

- Foreman, J. (1906), The Philippine Islands: A Political, Geographical, Ethnographical, Social, and Commercial History of the Philippine Archipelago, New York: Charles Scribner's Sons

- Gatbonton, Esperanza B., ed. (2000), The Philippines After The Revolution 1898–1945, National Commission for Culture and the Arts, ISBN 971-814-004-2

- Custodio, Teresa Ma; Dalisay, Jose Y. (1998), "Reform and Revolution", Kasaysayan: The History of the Filipino People, 5, Asia Publishing Company Limited, ISBN 962-258-228-1, https://books.google.com/books?as_isbn=9622582281

- Guevara, Sulpico, ed. (2005), The laws of the first Philippine Republic (the laws of Malolos) 1898–1899, Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Library (published 1972), http://quod.lib.umich.edu/cgi/t/text/text-idx?c=philamer;iel=1;view=toc;idno=aab1246.0001.001, retrieved on 2008-03-26 (English translation by Sulpicio Guevara)

- Halili, Maria Christine N. (2004), Philippine History, Manila: Rex Book Store, ISBN 978-971-23-3934-9, https://books.google.com/books?id=gUt5v8ET4QYC&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false

- Halstead, Murat (1898), "XII. The American Army in Manila", The Story of the Philippines and Our New Possessions, Including the Ladrones, Hawaii, Cuba and Porto Rico, http://www.gutenberg.org/catalog/world/readfile?fk_files=58428&pageno=122

- Jagor, Feodor (1873) (in German), Weidmannsche Buchhandlung, Berlin. An English translation under the title Travels in the Philippines was printed in London, 1875, by Chapman and Hall.

- Kalaw, Maximo Manguiat (1927), The Development of Philippine Politics, Oriental commercial, http://quod.lib.umich.edu/cgi/t/text/pageviewer-idx?c=philamer&cc=philamer&idno=afj2233.0001.001&frm=frameset&view=image&seq=17, retrieved on 2008-02-07

- Keat, Gin Ooi (2004), Southeast Asia: A Historical Encyclopedia, from Angkor Wat to East Timor, Volume 1, BC-CLIO, ISBN 978-1-57607-770-2, https://books.google.com/?id=QKgraWbb7yoC

- Mabini, Apolinario (1969), "CHAPTER VIII: First Stage of the Revolution", in Guerrero, Leon Ma., The Philippine Revolution, National Historical Commission, http://www.univie.ac.at/Voelkerkunde/apsis/aufi/history/mabini08.htm, Translated by Leon Ma. Guerrero.

- Lone, Stewart (2007). Daily Lives of Civilians in Wartime Asia: From the Taiping Rebellion to the Vietnam War. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-33684-3.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Montero y Vidal, Jose (1887–1895) (in Spanish), Historia general de Filipinas, 1-3, Madrid: Imprenta de Manuel Tello

- Nelson-Pallmeyer, Jack (2005), Saving Christianity from empire, Continuum International Publishing Group, ISBN 978-0-8264-1627-8, https://books.google.com/?id=klhCyWYvnTwC

- Regidor, Antonio M.; Mason, J. Warren (1905), Commercial Progress in the Philippine Islands, London: Dunn & Chidley

- Rodao, Florentino; García, Florentino Rodao; Rodríguez, Felice Noelle (2001), The Philippine revolution of 1896: ordinary lives in extraordinary times, Ateneo de Manila University Press, ISBN 978-971-550-386-0, https://books.google.com/?id=l533SkJ2VCkC

- Salazar, Zeus (1994), Agosto 29-30, 1896: ang pagsalakay ni Bonifacio sa Maynila, Quezon City: Miranda Bookstore, https://books.google.com/?id=J4RoHQAACAAJ

- Seekins, Donald M. (1991), "Historical Setting—Outbreak of War, 1898", in Seekins, Dolan, Philippines: A Country Study, Washington: Library of Congress, http://lcweb2.loc.gov/cgi-bin/query/r?frd/cstdy:@field(DOCID+ph0023), retrieved on 2007-12-25

- Sagmit, Rosario S.; Sagmit-Mendosa, Lourdes (2007), The Filipino Moving Onward 5, Rex Bookstore, Inc., ISBN 978-971-23-4154-0

- Schumacher, John N. (1991), The Making of a Nation: Essays on Nineteenth-century Filipino Nationalism, Ateneo de Manila University Press, ISBN 978-971-550-019-7, https://books.google.com/books?id=k2R39kbi1FYC

- Titherington, Richard Handfield (1900), A history of the Spanish–American War of 1898, D. Appleton and Company, http://ia311507.us.archive.org//load_djvu_applet.php?file=3/items/spanishamwar00tithrich/spanishamwar00tithrich.djvu

- Worcester, Dean Conant (1914), The Philippines: Past and Present (vol. 1 of 2), Macmillan, pp. 75–89, ISBN 1-4191-7715-X, http://www.gutenberg.org/etext/12077, retrieved on 2008-02-07

- Zaide, Gregorio (1954), The Philippine Revolution, Manila: The Modern Book Company

- Zaide, Gregorio F. (1957), Philippine Political and Cultural History: The Philippines Since the British Invasion, II (1957 Revised ed.), Manila: McCullough Printing Company

External links

- Don Emilio Aguinaldo y Famy. "True Version of the Philippine Revolution". Authorama Public Domain Books. Retrieved 2007-11-16. (page 1 of 20 linked web pages)

- Hisona, Harold T. "Opening of Manila to World Trade". Philippine Almanac.

- Coats, Steven D. (2006). "Gathering at the Golden Gate: Mobilizing for War in the Philippines, 1898". Combat studies Institute Press.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help) Part 1 (Ch. I–IV), Part 2 (Ch. V–VIII). - The Philippine Revolution by Apolinario Mabini

- Centennial Site: The Katipunan

- Leon Kilat covers the Revolution in Cebu (archived from the original on 2009-10-26)

- Another site on the Revolution (archived from the original on 2007-10-13)

- CS1: Julian–Gregorian uncertainty

- CS1 errors: unsupported parameter

- Pages using multiple image with manual scaled images

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- CS1 errors: periodical ignored

- CS1 errors: requires URL

- Rebellions in the Philippines

- 19th-century revolutions

- حروب استقلال

- Philippine Revolution

- Wars involving Spain

- Rebellions against the Spanish Empire

- History of the Philippines (1521–1898)

- Separatism in Spain

- 1890s in the Philippines

- 1896 in the Philippines