أسباب الحرب العالمية الأولى

أسباب الحرب العالمية الأولى، لا تزال محل جدل. بدأت الحرب العالمية الأولى في البلقان في أواخر يوليو 1914 وانتهت بهدنة في نوفمبر 1918، تاركة 17 مليون قتيل و20 مليون مصاب.

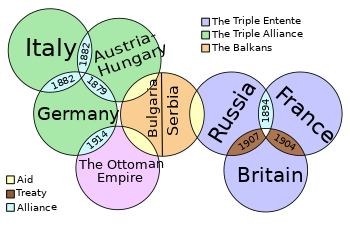

يسعى الباحثون منذ زمن طويل إلى شرح سبب وجود مجموعتين من القوى المتنافسة - ألمانيا والنمسا-المجر من جهة، وروسيا، فرنسا، وبريطانيا العظمى من جهة أخرى- دخلت النزاع بحلول 1914. يبحثون عن العوامل السياسية، النزاعات الاقليمية والاقتصادية، العسكرة، شبكة معقدة من التحالفات، الاستعمارية، تنامي الحركات القومية، وفراغ السلطة الذي نشأ بعد أفول الدولة العثمانية. العوامل طويلة المدى أو البنيوية الهامة الأخرى عادة ما تتضمن دراستها النزاعات الاقليمية الغير محلولة، الانهيار المُدرج لتوزان القوى في أوروپا،[1][2] الحوكمة المعقدة والمهترأة، سباقات التسلح في العقود السابقة، والتخطيط العسكري.[3]

أجرى الباحثون تحليلاً قصير المدى ركز على صيف 1914 لمعرفة ما إذا كان من الممكن إيقاف النزاع، أو ما إذا كان قد أصبح خارج السيطرة. تكمن الأسبابا لمباشرة للحرب في القرارات التي اتخذها رجال الدولة والجنرالات أثناء أزمة يوليو 1914. اشتعلت الأزمة بسبب اغتيال الأرشدوق فرانتس فرديناند من النمسا على يد أحد صربيي البوسنة الذي كان يؤيد إحدى المنظمات القومية في صربيا.[4] تحولت الأزمة إلى نزاع بين النمسا-المجر وصربيا لتشمل روسيا، ألمنيا، فرنسا، وفي النهاية بلجيكا وبريطانيا العظمى. وشملت العوامل الأخرى التي ظهرت أثناء الأزمة الدبلوماسية التي سبقت الحرب سوء فهم النوايا (مثل اعتقاد ألمانيا أن بريطنيا ستظل على الحياد)، القدرية التي جعلت من الحرب أمر لا مفر منه، وتسارع الأزمة، والتي تفاقمت بسبب التأخير وسوء الفهم في الاتصالات الدبلوماسية.

تلت الأزمة سلسلة من الاشتباكات الدبلوماسية بين القوى العظمى (إيطاليا، فرنسا، ألمانيا، بريطانيا، النمسا-المجر وروسيا) على قضايا استعمارية وأوروپية في العقود السابقة لعام 1914 والتي تركت قدراً كبيراً من التوترات. بدورها، يمكن إرجاع هذه الصدامات العامة إلى التغييرات في ميزان القوى في أوروپا منذ عام 1867.[5]

لا يزال الإجماع على أصول الحرب أمراً لا يمكن تعقبه، لأن المؤرخين يختلفون حول العوامل الرئيسية المسبب للحرب، ويضعون تركيزاً مختلفاً على مجموعة متنوعة من العوامل. يصبح هذا الأمر أكثر تعقيداً مع الحجج التاريخية المتغيرة مع مرور الزمن، لا سيما تأخر توافر المحفوظات التاريخية السرية. التمييز الأكثر عمقاً بين المؤرخين هو بين أولئك الذين يركزون على تحركات ألمانيا والنمسا-المجر كعامل رئيسي، وأولئك الذين يركزون على مجموعة أوسع من الفاعلين. أمام الأخطاء الثانوية فتوجد بين أولئك الذين يعتقدون أن ألمانياً قد خططت عمداً لحرب أوروپية، وأولئك الذين يعتقدون أن الحرب لم يكن مخططاً لها في النهاية لكن لا يزال السبب الرئيسي لها يقع على عاتق ألمانيا والنمسا-المجر، وأولئك الذين يعتقدون أنها بسبب جميع أو بعض من العوامل الأخرى، مثل روسيا، فرنسا، صريبيا وبريطانيا العظمى، التي لعبت دوراً أكثر أهمية في قيام الحرب أكثر من العوامل التقليدية المقترحة.

الاستقطاب في أوروپا 1887–1914

لفهم الأصول طويلة المدى لحرب 1914، من الضروري فهم كيفية تشكل القوى إلى مجموعتين متنافستين تتشاركان نفس الأهداف والأعداء. أصبحت هاتين المجموعتين، بحلول أغسطس 1914، ألمانيا والنمسا-المجر من جانب وروسيا، فرنسا، صربيا وبريطانيا العظمى من جانب آخر.

اعادة انحياز ألمانيا للنمسا-المجر واعادة انحياز روسيا لفرنسا، 1887–1892

عام 1887 جرى تأمين الانحياز الألماني الروسي عن طريق معاهدة إعادة التأمين التي وقعها اوتو فون بسمارك. ومع ذلك، عام 1890 زالت المعاهدة من أجل التحالف المزودج (1879) بين ألمانيا والنمسا-المجر. يعود الفضل لهذا التطور إلى الكونت ليون فون كاپريڤي، الجنرال الپروسي الذي خلف بسمارك كمستشاراً. يزعم أن المستشار الجديد قد اعترف بعدم قدرته الشخصية على ادارة النظام الأوروپي كما كان سلفه، ولذلك استعاون بمشورة شخصيات معاصرة مثل فردريش فون هولشتاين لاتباع نهج أكثر منطقية مقابل استراتيجية بسمارك المعقدة بل حتى المخادعة.[6] بالتالي، تم التوصل إلى معاهدة مع النمسا-المجر على الرغم من الاستعداد الروسي لتعديل معاهدة إعادة التأمين والتضحية بالبند المشار إليه على أنه "إضافات بالغة السرية"[6] والمتعلق بالمضائق.[7]

كان قرار فون كاپريڤي يرجع أيضاً إلى الاعتقاد بأن معاهدة إعادة التأمين لم تعد مطلوبة لتأمين الحيادية الروسية في حالة شن فرنسا هجوماً على ألمانيا وأن من شأنها حتى أن تستبعد وقوع هجوماً ضد فرنسا.[8] بسبب افتقاده الغموض الاستراتيجي الذي كان لدى بسمارك، اتبع المستشار الجديد سياسة كانت موجهة نحو "قبول روسيا بوعود برلين بحسن النية وتشجيع سانت پطرسبورگ في إطار تفاهم مباشر مع ڤيينا، بدون اتفاق مكتوب."[8] بحلول 1892، توسع التحالف المزدوج ليشمل إيطاليا.[9] رداً على ذلك، أمنت روسيا في العام نفسه تحالفاً مع فرنسا، علاقة عسكرية قوية استمرت حتى 1917. كانت هذه الخطوة مدفوعة بالحاجة الروسية إلى حليف منذ ذلك الحين، خلال هذه الفترة، كانت روسيا تعاني من مجاعة كبرى وتصاعد في الأنشطة الثورية المناهضة للحكومة.[8] بُني هذا التحالف تدريجياً خلال سنوات بدأت منذ عهد بيسمارك الذي رفض بيع السندات الروسية في برلين، مما دفع روسيا إلى سوق العاصمة باريس.[10] بدا هذا توسعاً في العلاقات المالية الروسية الفرنسية، والذي ساعد في النهاية على النهوض بالوفاق الفرنسي الروسي إلى المجال الدبلوماسي والعسكري.

اتضح أن استراتيجية فون كاپريڤي قد حققت نجاحاً عندما، أثناء اندلاع الأزمة البوسنية 1908، طالب روسيا بالتراجع وسحب قواتها، وقد فعلت.[11] عندما طالبت ألمانيا روسيا بالتراجع مرة أخرى في النزاع اللاحق، رفضت روسيا، مما ساعد في النهاية على تعجيل الحرب.

الارتياب الفرنسي من ألمانيا

يمكن النظر لبعض الأصول البعيدة للحرب العالمية الأولى في نتائج وعواقب الحرب الفرنسية الپروسية عام 1870-1871 وتوحيد ألمانيا المتزامن. حققت ألمانيا نصراً حاسماً وأسست امبراطورية قوية، بينما سقطت فرنسا في حالة من الفوضى والتراجح العسكري لسنوات. تنامى تراث من العداء بين فرنسا وألمانيا في أعقاب ضم ألمانيا لألزاس-لورين. تسبب الضم في استياء واسع النطاق في فرنسا، مما أدى إلى الرغبة في الانتقام، التي عُرفت بنزعة الثأثر revanchism. استندت المشاعر الفرنسية على الرغبة في الانتقام من الخسائر العسكرية والإقليمية وتشريد فرنسا كقوة عسكرية قارية بارزة.[12] كان بسمارك حذراً من الرغبة الفرنسية في الانتقام. حقق السلام بعزل فرنسا وتحقيق التوازن بين طموحات النمسا والمجر وروسيا في البلقان. خلال سنواته اللاحقة، حاول استرضاء الفرنسيين بتشجيع توسعهم في الخارج. ومع ذلك، ظلت المشاعر المعادية للألمان قائمة.[13]

في النهاية تعافت فرنسا من هزيمتها، دفعت تعويض حربها، وأعادت بناء قوتها العسكرية مرة أخرى. لكن الأمة الفرنسية كانت أصغر من ألمانيا من حيث عدد السكان والصناعة، وبالتالي شعر العديد من الفرنسيين بعدم الأمان إلى جوار دولة أكثر قوة. [14] بحلول عقد 1890 لم تكن الرغبة في الثأر لضم ألزاس-لورين عاملاً رئيسياً لقادة فرنسا، لكنها ظلت قوية لدى الرأي العام. جول كامبون، السفير الفرنسي لدى برلين (1907-1914)، عمل جاهداً لتأمين الانفراجة، لكن القادة الفرنسيين قرروا أن برلين كانت تحاول إضعاف الوفاق الثلاثي ولم تكن مخلصة في السعي إلى السلام. كان هناك إجماع فرنسي على أن الحرب حتمية.[15]

تحالف بريطانيا مع فرنسا وروسيا، 1898-1907: الوفاق الثلاثي

بعد إقالة بسمارك عام 1890، نجحت الجهود الفرنسية في عزل ألمانيا. مع تشكيل الوفاق الثلاثي، بدأت ألمانيا تشعر بأنها محاصرة.[16] وزير الخارجية الفرنسية تيوفيل كلكاسيه بذلك جهداً كبيراً للتودد إلى روسيا وبريطانيا العظمى. كانت الدلالات الرئيسية لهذا الجهد هي التحالف الفرنسي الروسي عام 1894، الاتفاق الودي 1904 مع بريطانيا العظمى وأخيراً الوفاق الإنگليزي الروسي عام 1907، الذي أصبح الوفاق الثلاثي. الانحياز الغير رسمي مع بريطانيا والتحالف الرسمي مع روسيا ضد ألمانيا والنمسا أدى في النهاية إلى دخول روسيا وبريطنيا الحرب العالمية الأولى كحلفاء لفرنسا.[17][18]

تخلت بريطانيا عن سياستها في العزلة العظيمة في عقد 1900 بعد أن عُزلت أثناء حرب البوير. عقدت بريطانيا اتفاقيات، اقتصرت على شئونها الاستعمارية، مع منافسيها الاستعماريين الرئيسيين: الاتفاق الودي مع فرنسا عام 1904 والوفاق الإنگليزي الروسي 1907. يرى بعض المؤرخين أن انحياز بريطانيا هو في الأساس رد فعل على السياسة الخارجية الألمانية الحازمة وترسيخ لبحريتها منذ عام 1898 الذي أدى إلى سباق التسلح البحري الإنگليزي الألماني.[19][20] بينما يزعم باحثون آخرون، من أشهرهم نيالي فرگسون، أن بريطانيا اختارت فرنسا ورسيا بدلاً من ألمانيا لأن ألمانيا كانت أضعف من أن تكون حليفاً يوفر قوة توازن مؤثرة على القوى الأخرى ولا يمكنها أن تزود بريطانيا بالأمن الإمبراطوري الذي تحققه اتفاقات الوفاق.[21] حسب كلمات الدبلوماسي البريطاني آرثر نيكلسون، كان "الوضح سيصبح أكثر عجزاً بالنسبة لنا عندما يكون لدينا فرنسا وروسيا الغير وديتين أكثر من ألمانيا غير الودية".[22] يزعم فرگسون أن الحكومة البريطانية رفضت التحالف الألماني "ليس لأن ألمانيا بدأت تشكل تهديداً لبريطانيا، بل على العكس لأنها أدركت أنها لم تعد تشكل تهديداً".[23] ذلك كان تأثير الوفاق الثلاثي ذو شقين، الأول تحسين العلاقات البريطانية مع فرنسا وحليفتها روسيا، والثاني تقليل أهمية العلاقات الجيدة لبريطانيا مع ألمانيا. "لم يكن هذا العداء تجاه ألمانيا سبباً في عزلتها، بل إن النظام الجديد نفسه قام بتوجيه وتكثيف العداوة تجاه الإمبراطورية الألمانية".[24]

الوفاق الثلاثي الذي تضمن بريطانيا، فرنسا وروسيا عادة ما يُقاربن بالتحالف الثلاثي بين ألمانيا، النمسا-المجر وإيطاليا، لكن المؤرخين يحذرون من هذه المقارنة. الوفاق، على عكس التحالف الثلاثي أو التحالف الفرنسي الروسي، لم يكن تحالفاً للدفاع المشترك، وبالتالي شعرت بريطنايا بحريتها في صنع قرارات سياستها الخارجية عام 1914. كما يشير مسئول مكتب الخارجية البريطانية أير كراو: "الحقيقة الأساسية بالطبع هي أن "التفاهم" ليس تحالفاً". ولأغراض حالات الطوارئ القصوى، قد لا تكون هناك أي أهمية على الإطلاق. بالنسبة للوفاق، فهو لا يعدو عن أن يكون إطاراً عقلياً، ووجهة نظر السياسة العامة التي تتقاسمها حكومتا البلدين، ولكن قد تكون، أو تصبح، غامضة لدرجة أن تفقد كل محتواها".[25]

وقعت سلسلة من الحوادث الدبلوماسية بين 1905 و1914 سلطت الضوء على التوترات بين القوى العظمى وعززت التحالفات القائمة، بدءاً من الأزمة المغربية الأولى.

الأزمة المغربية الأولى، 1905-06: تعزيز الوفاق

الأزمة المغربية الأولى (تُعرف أيضاً بأزمة طنجة) كان نزاعاً دولياً وقع بين مارس 1905 ومايو 1906 على وضع المغرب. تسببت الأزمة في تدهور العلاقات بين ألمانيا وكلاً من فرنسا والمملكة المتحدة، وساعدت على ضمان نجاح الوفاق الأنگلو-فرنسي الجديد. حسب كلمات المؤرخ كريستوفر كلارك، "تعزز الوفاق الأنگلو-فرنسي الجديد بدلاً من أن يضعف بتحدي ألمانيا لفرنسا في المغرب".[26]

الأزمة البوسنية، 1908: تدهور علاقات روسيا وصربيا مع النمسا-المجر

عام 1908 أعلنت النمسا-المجر ضمها البوسنة والهرسك، مقاطعين في منطقة البلقان في أوروپا كانتا تحت سيطرة الدولة العثمانية. على الرغم من أن البوسنة والهرسك كانت لا تزال اسمياً تحت سيادة الدولة العثمانية، إلا أن النمسا-المجر كانت تدير المقاطعتين منذ مؤتمر برلين 1878، عندما فازت القوى العظمى الأوروپية بحق احتلال المقاطعتين، مع الإبقاء على اللقب القانوني لتركيا. إعلان النمسا-المجر ضم البوسنة والهرسك في أكتوبر 1908 أخل بتوازن القوى الهش في البلقان، مما أثار غضب صربيا والوطنيين السلاڤيين في جميع أنحاء أوروپا. على الرغم من إضعاف روسيا، إلا أنها اضطرت إلى الخضوع للإذلال، فما زال مكتبها الخارجي ينظر إلى تصرفات النمسا-المجر على أنها عدوانية وتمثل تهديد مفرط. كان رد روسيا هو تشجيع المشاعر المعادية للنمسا في صربيا، ومقاطعات البلقان الأخرى، مما أثار المخاوف النمساوية من التوسعية السلاڤية في المنطقة.[27]

أزمة أغادير، 1911

دفعت المنافسات الاستعمارية فرنسا وألمانيا وبريطانيا للتنافس من أجل السيطرة على المغرب، مما أدى إلى ذعر من حرب قصيرة المدى عام 1911. في النهاية، أسست فرنسا محمية في المغرب التي زادت من حدة التوترات الأوروپية. نتجت أزمة أغادير نشر قوة كبيرة من الجيش الفرنسي في المناطق الداخلية من المغرب في أبريل 1911. ردت ألمانيا بإرسال زورق المدفعية إسإمإس پانثر إلى ميناء أغادير المغربي في 1 يوليو 1911. كانت النتيجة الرئيسية تعميق الشكوك بين لندن وبرلين، وتوثيق العلاقات العسكرية بين لندن وباريس.[28][29]

قرب الخوف والعداء المتزايد بريطانيا من فرنسا بدلاً من ألمانيا. الدعم البريطاني لفرنسا خلال الأزمة عزز الوفاق بين البلدين (ومع روسيا كذلك)، مما زاد من النفور الأنگلو-ألماني، وعمّق الانقسامات التي ستنشب عام 1914.[30] في ما يتعلق بالمناقشات البريطانية الداخلية، كانت الأزمة جزءاً من صراع استمر خمس سنوات داخل الحكومة البريطانية بين الانعزاليين المتطرفين والتدخليين الإمبرياليين في الحزب الليبرالي. سعى التدخليون إلى استخدام الوفاق الثلاثي لاحتواء التوسع الألماني. ومع ذلك، انضم إلى التدخليين اثنين من الراديكاليين الرواد، ديڤد لويد جورج وونستون تشرشل. أغضب خطاب لويد جورج الشهير "خطاب قصر مانسيون" في 21 يوليو 1911 الألمان وشجع الفرنسيين. بحلول 1914 كان التدخليون والراديكاليون قد اتفقا على تشارك مسئولية القرارات التي انتهت إلى إعلان الحرب، ومن ثم كان القرار بالإجماع تقريباً.[31]

وفي يخص أحداث 1914 على وجه التحديد، أدتدفعت الأزمة وزير الخارجية البريطاني إدوارد گريْ وفرنسا إلى تأسيس اتفاقية بحرية سرية والتي بموجبها تقوم البحرية الملكية بحماية الساحل الشمالي الفرنسي من الهجمات الألمانية، بينما تحشد فرنسا أسطولها في غرب المتوسط ووافقت على حماية المصالح البريطانية هناك. بالتالي كانت فرنسا قادرة على حماية اتصالاتها بمستعمرات شمال أفريقيا، وتمكنت بريطانيا من تركيز المزيد من القوات في المياه الداخلية قبالة الأسطول الألماني أعالي البحار. لم يصدق مجلس الوزراء على هذه الاتفاقية حتى أغسطس 1914. في الوقت نفسه، عزز الحدث من سلطة الأميرال ألفرد فون ترپتس، الذي دعا إلى زيادة القوات البحرية وتم ذلك عام 1912.[32]

الحرب الإيطالية التركية: التخلي عن العثمانيين، 1911–12

في الحرب الإيطالية التركية هزمت إيطاليا الدولة العثمانية في شمال أفريقيا عام 1911-12.[33] استولت إيطاليا بسهولة على المدن الساحلية الهامت لكن جيشها فشل في إحراز المزيد من التقدم في الداخل. استولت إيطاليا على إيالة طرابلس العثمانية، التي كان من أشهر سناجقها فزان، برقة وطرابلس. كانت هذه الأراضي تشكل معاً ما أصبح يُعرف بليبيا الإيطالية. كانت الأهمية الرئيسية للحرب العالمية الأولى توضيح أنه لا توجد قوى عظمى تتمنى دعم الدولة العثمانية بعد الآن ومهد هذا الطريق إلى حروب البلقان. أوضح كريستوفر كلارك: أن "إيطاليا شنت حرباً لاجتياح إحدى مقاطعات الدولة العثمانية، مما تسبب في سلسلة من الاعتداءات الانتهازية على الأراضي العثمانية عبر البلقان. وقد جُرفت منظومة التوازنات الجغرافية مما سمح بتضمين النزاعات المحلية." [34]

حروب البلقان، 1912-13: تنامي القوى الصربية والروسية

كانت حروب البلقان نزاعين وقعا في شبه جزيرة البلقان في في جنوب شرق أوروپا عام 1912 و1913. هزمت دول البلقان الأربعة الدولة العثمانية في الحرب الأولى؛ إحدى الدول الأربعة، بلغاريا، هُزمت في الحرب الثانية. خسرت الدولة العثمانية جميع أراضيها في أوروپا تقريباً. النمسا-المجر، على الرغم من أنها لم تكن طرفاً في الحرب، ضعفت مع توسع صربيا بشكل كبير من أجل اتحاد شعوب جنوب السلاڤية.

زادت حروب البلقان 1912-1913 التوتر الدولي بين الامبراطورية الروسية والنمسا-المجر. كما أدت إلى تعزيز صربيا وإضعاف الدولة العثمانية وبلغاريا، الذين ربما كانوا سيبقون صربيا تحت سيطرتهم، وبالتالي يعطلون توازن القوى في أوروپا لصالح روسيا.

في البداية وافقة روسيا على تجنب التغيرات الاقليمية، لكن لاحقاً عام 1912 دعمت مطالب صربيا بميناء ألباني. تمخض مؤتمر لندن 1912-1913 عن تأسيس ألبانيا المستقلة؛ إلا أن كلاً من صربيا والجبل الأسود رفضا الامتثال. بعد الحشد البحري النمساوي، ثم الدولي في أوائل 1912 وانسحاب روسيا من دعمها، تراجعت صربيا. لم يمتثل الجبل الأسود حتى 2 مايو، اجتمع مجلس الوزراء النمساوي وقرر منح الجبل الأسود فرصة أخيرة للموافقة، وإذا لم يحدث، سيتم اللجوء إلى حراك عسكري. ومع ذلك، عند رؤية التحضيرات العسكرية النمساوية، طلب الجبل الأسود تأجيل الموعد النهائي وامتثل له.[35]

الحكومة الصربية، بعد أن فشلت في الحصول على ألبانيا، طالبت بإعادة تخصيص الغنائم الأخرى لحرب البلقان الأولى، وفشلت روسيا في الضغط على صربيا للتراجع. تحالفت صربيا واليونان ضد بلغاريا، التي ردت بضربة استباقية ضد قواتهما، ما يعتبر بداية لحرب البلقان الثانية.[36] سرعان ما سُحق الجيش البلغاري بعد انضمام تركيا ورومانيا للحرب.

وترت حروب البلقان التحالف الألماني/النمساوي-المجري. كان موقف الحكومة الألمانية من طلبات الدعم النمساوية ضد صربيا في البداية منقسماً وغير متسق. بعد اجتماع مجلس الحرب الألماني في 8 ديسمبر 1912، وإعلانه أن ألمانيا غير مستعدة لدعم النمسا-المجر في الحرب ضد صربيا وحلفائها المرجعين.

بالإضافة إلى ذلك، كانت الدبلوماسية الألمانية، قبل وأثناء وبعد حرب البلقان الثانية، تدعم اليونان ورومانيا وتعارض آراء النمسا-المجر المدعمة بشكل متزايد لدعم بلغاريا. كانت النتيجة ضرر هائل بالعلاقات النمساوية الألمانية. قدم وزير الخارجية النمساوي ليوپولد فون برتشتولد ملاحظة إلى السفير الألماني هنريش فون تشيرشكي في يوليو 1913 بأن "Austria-Hungary might as well belong 'to the other grouping' for all the good Berlin had been".[37]

في سبتمبر 1913، كان من المعلوم أن صربيا في طريقها إلى ألبانيا وأن روسيا لا تفعل شيئاً لكبح جماحها، في حين أن الحكومة الصربية لن تضمن احترام سلامة أراضي ألبانيا واقترحوا إجراء بعض التعديلات على الحدود. في أكتوبر 1913، قرر مجلس الوزراء إرسال تحذير لصربيا يليه إنذار نهائي: بأن ألمانيا وإيطاليا لاحظتا بعض الحراك وتطلب الدعم، وأن سيتم إرسال الجواسيس للإبلاغ عما إذا كان هناك انسحاب فعلي. وردت صربيا على التحذير بتحدي وتم إرسال الإنذار في 17 أكتوبر وأُستلم في اليوم التالي. طالب الإنذار صربيا بإجلاء الأراضي الألبانية في غضون ثمانية أيام. امتثلت صربيا، وقام القيصر بزيارة تهنئة لڤيينا في محاولة لإصلاح بعض الأضرار التي حدثت في وقت سابق من العام.[38]

بمرور الوقت، تعافت روسيا بشكل كامل من هزيمتها في الحرب الروسية اليابانية، وكانت حسابات ألمانيا والنمسا مدفوعة بالخوف من أن تصبح روسيا في نهاية المطاف قوية للغاية بحيث لا يمكن تحديها. وكان استنتاجهم أن أي حرب مع روسيا يجب أن تحدث في غضون السنوات القليلة المقبلة من أجل الحصول على أي فرصة للنجاح.[39]

تغيرات التحالف الفرنسي-الروسي: سيناريو بداية البلقان، 1911–1913

تشكل التحالف الفرنسي الروسي الأصلي لحماية فرنسا وروسيا من الهجوم الألماني. في حال حدوث مثل هذا الهجوم، ستقوم كلتا الدولتين بالتعبئة بشكل مترادف، مما يضع ألمانيا تحت تهديد حرب على جبهتين. ومع ذلك، فقد وُضعت حدود للتحالف بحيث تجعله ذو طابع دفاعي.

على مدار عقد 1890 و1900 أوضح الفرنسيون والروس أن حدود التحالف لم تمتد إلى الاستفزازات التي تسببها السياسة الخارجية المغامرة للآخرين. على سبيل المثال، حذرت روسيا فرنسا من أن التحالف لن يكون فعالاً إذا ما اشتبكت فرنسا مع ألمانيا في شمال أفريقيا، وبالمثل، أصرت فرنسا على أنه لا ينبغي على الروس استخدام التحالف لشن حرب مع النمسا-المجر أو ألمانيا في البلقان، وان فرنسا لن تعترف بالبلقان كمصلحة استراتيجية حيوية لفرنسا أو لروسيا.

في الأشهر 18-24 الأخيرة قبل اندلاع الحرب، تغير هذا. عند نهاية 1911 وخاصة أثناء حروب البلقان نفسها عام 1912-13، تغير رأي فرنسا. قبلت فرنسا بأهمية البلقان لروسيا. علاوة على ذلك، أعلنت فرنسا بوضوح أنه، إذا كانت نتيجة الصراع في البلقان، اندلعت الحرب بين النمسا-المجر وصربيا، فإن فرنسا ستقف بجانب روسيا. بالتالي فقد تغيرت طبيعة التحالف الفرنسي الروسي، ونتيجة لذلك أصبحت صربيا خطاً دفاعياً أمنياً بارزاً لروسيا وفرنسا. As they bought into the future scenario of a war of Balkan inception, regardless of who started such a war, the alliance would respond nonetheless. سينظر إلى الصراع باعتباره حالة تحالف casus foederis: أي محفز للتحالف. وصف كرسيوفر كلارك هذا التغير بأنه "تطور بالغ الأهمية في منظومة ما قبل الحرب التي جعلت أحداث 1914 ممكنة".[40]

"قضية" ليمان-فون ساندرز، 1913-14

نشبت هذه الأزمة بسبب تعين أحد الضباط الألمان، ليمان فون ساندرز لقيادة الفيلق الأول التركي الذي يتولى حراسة القسطنطينية، والاعتراضات الروسية اللاحقة.

بدأت "قضية ليمان فون ساندرز" في 10 نوفمبر 1913، عندما أعطى وزير الخارجية الروسي سرگي سازونوڤ تعليمات للسفير الروسي في برلين سرگي سڤربييڤ بأن يخبر الألمان أن مهمة فون ساندرز، يعتبرها الروس "تحركاً عدائياً علنياً". بالإضافة إلى تهديد التجارة الخارجية لروسيا، فإنه يهدد أيضاً نصف هذه التجارة المار عبر المضائق التركية، بعد أن أثارت المهمة احتمالية هجوم تركي بقيادة ألمانية على الموانئ الروسية على البحر الأسود وتهديد الخطط التوسعية الروسية في شرق الأناضول.

أثار تعيين ليمان عاصفة احتجاجات من روسيا، التي شكت في وجود خطط ألمانيا حول العاصمة العثمانية. بعد ذلك تم الاتفاق على تنازلات حيث تم تعيين ليمان في منصب أقل أهمية (وأقل نفوذاً) حيث عُين مفتشاً عاماً في يناير 1914.[41]

نتيجة للأزمة، Russia's weakness in military power prevailed. لم يكن بمقدور الروس الاعتماد على وسائلهم المالية كأدة للسياسة الخارجية.[42]

الانفراجة البريطانية-الألمانية، 1912–14

يحذر المؤرخون من أنه لا ينبغي الإشارة إلى الأزمة السابقة باعتبارها حجة مفادها أن الحرب الأوروپية كانت حتمية في عام 1914. ومن الجدير بالذكر أن السباق البحري البريطاني الألماني قد انتهى بحلول 1912. في أبريل 1913، وقعت بريطانيا وألمانيا اتفاقية تخص الأراضي الأفريقية التابعة للامبراطورية الپرتغالية التي كانت على وشك الانهيار. علاوة على ذلك، كان الروس يهددون المصالح البريطانية في پروسيا والهند حتى أنه في عام 1914 ، كانت هناك دلائل على أن البريطانيين كانوا فاترين في علاقاتهم مع روسيا وأن التفاهم مع ألمانيا قد يكون مفيداً. كان البريطانيون "منزعجون بشدة من فشل سانت پطرسبورگ فيما يخص الالتزام بشروط الاتفاقية التي تم توقيعها عام 1907 وبدأوا في الشعور بأن ترتيب من نوع ما مع ألمانيا قد يكون بمثابة تصحيحاً مفيداً".[22]

كتب الدبلوماسي البريطاني آرثر نيكلسون في مايو 1914، "منذ أن كنت في وزارة الخارجية لم أر مثل هذه المياه الهادئة".[43]

أزمة يوليو: تسلسل الأحداث

- 28 يوليو 1914: وحدوي صربي يغتال أرشدوق فرانتس فرديناند من امبراطورية النمسا-المجر.

- 30 يونيو: وزير الخارجية النمساوي كونت ليوپولد برتشتولد والامبراطور فرانز يوزف يتفقان على "سياسة الصبر" مع صربيا وصلت لنهايتها وأنه ينبغي اتخاذ موقف حاسم.

- 5 يوليو: الدبلوماسي النمساوي ألكسندر، كونت هويوس يزور برلين للتأكد من المواقف الألمانية.

- 6 يوليو: ألمانيا تقدم دعماً غير مشروط للنمسا-المجر- ما اشتهر بـ"شيك على بياض".

- 20-23 يوليو: الرئيس الفرنسي ريمون پوانكاريه، أثناء زيارة رسمية للقيصر في سانت پطرسبورگ، يحث على المعارضة المتعنتة لأي تدبير نمساوي ضد صربيا.

- 23 يوليو: النمسا-المجر، في أعقاب تحقيقا السري، ترسل انذار أخير لصربيا، يحتوي على طلباتها، ويمنح صربيا مهلة 24 ساعة للامتثال.

- 24 يوليو: السير إدوارد گري، موجهاً حديثه للحكومة البريطانية، يطلب أن ألمانيا، فرنسا، إيطاليا وبريطانيا العظمى، "التي ليس لديها مصالح مباشرة في صربيا، ينبغي أن تتحرك معاً من أجل السلام بشكل متزامن".[44]

- 24 يوليو: صربيا تسعى لدعم من روسيا وروسيا توصي صربيا بعدم قبول الإنذار الأخير.[45] ألمانيا تعلن رسمياً دعمها بموقف النمسا.

- 24 يوليو: مجلس الوزراء الروسي يوافق على تعبئة جزئية سرية للجيش والبحرية الروسية.[بحاجة لمصدر]

- 25 يوليو: القيصر يوافق على قرار مجلس الوزراء وروسيا تبدأ تعبئة جزئية لـ1.1 مليون رجل ضد امبراطورية النمسا-المجر.[46]

- 25 يوليو: صربيا ترد على سعي النمسا-المجر بقبول غير كامل وتسعى للتحكيم في محكمة لاهاي. النمسا-المجر تقطع علاقاتها الدبلوماسية بصربيا. صربيا تحشد جيشها.

- 26 يوليو: الاحتياطي الصربي ينتهك عن طريق الخطأ الحدود النمساوية-المجرية عند تمس-كوبين.[47]

- 26 يوليو: تنظيم اجتماع بين سفراء بريطانيا العظمى، ألمانيا، إيطاليا وفرنسا لنقاش الأزمة. ألمانيا ترفض الدعوة.

- 28 يوليو: النمسا-المجر، تفشل في قبول رد صربيا في الخامس والعشرين، تعلن الحرب على صربيا. الحشد النسماوي-المجري يبدأ ضد صربيا.

- 29 يوليو: إدوارد گري يناشد ألمانيا التدخل لحفظ السلام.

- 29 يولوي: السفير البريطاني في برلين، سير إدوارد چوشن، يخبره المستشار الألماني أن ألمانيا تفكر في الحرب مع فرنسا، علاوة على ذلك، ترغب في إرسال جيشها عبر بلجيكا. إنه يحاول تأمين حياد بريطانيا في مثل هذا الحراك.

- 29 يوليو: في الصباح تعبئة عامة روسية ضد النمسا وألمانيا تفعل المثل؛ في المساء[48] القيصر يختار التعبئة الجزئية بعد موجة من البرقيات مع القيصر ڤيلهلم.[49]

- 30 يوليو: اعادة تنظيم التعبئة العامة الروسية بأمر من القيصر بتحريض من سرگي سازونوڤ.

- 31 يوليو: صدور أوامر بالتعبئة العامة النمساوية.

- 31 يوليو: ألمانيا تدخل فترة الإعداد للحرب.

- 31 يوليو: ألمانيا ترسل إنذار نهائي لروسيا، مطالبة إياها بوقف التعبئة العامة في غضون 12 ساعة، لكن روسيا ترفض.

- 31 يوليو: فرنسا وألمانيا تطالبان بريطانيا بإعلان دعمها لحياد بلجيكا الجاري. فرنسا توافق على هذا. ألمانيا لا ترد.

- 31 يوليو: ألمانيا تسأل فرنسا ما إذا كانت ستظل على الحياد في حالة وقوع حرب بين ألمانيا وروسيا.

- 1 أغسطس: صدور أوامر بالتعبئة العامة الألمانية، اختيار خطة الانتشار أوفمارش 2 الغربية.

- 1 أغسطس: صدور أوامر بالتعبئة العامة الفرنسية، اختيار خطة الانتشار 17.

- 1 أغسطس: ألمانيا تعلن الحرب على روسيا.

- 1 أغسطس: القيصر يرد على برقية الملك، معلناً، "من دواعي سروري أنني قبلت مقترحاتكم، لم يقدم السفير الألماني بعد ظهر اليوم مذكرة إلى حكومتي تُعلن فيها الحرب".

- 2 أغسطس: ألمانيا والدولة العثمانية يوقعان معاهدة سرية[50] مرسخة التحالف الألماني العثماني.

- 3 أغسطس: فرنسا ترفض (انظر الهامش[بحاجة لمصدر]) طلب ألمانيا بالبقاء على الحياد.[51]

- 3 أغسطس: ألمانيا تعلن الحرب على فرنسا.

- 3 أغسطس: ألمانيا تعلن لبلجيكا أنها "ستعاملها كعدو" إذا لم تسمح بمرور الجنود الألمان بحرية عبر أراضيها.

- 4 أغسطس: ألمانيا تنفذ عملية هجومية مستوحاة من الخطة شليفن.

- 4 أغسطس (منتصف الليل): بعد أن فشلت في تلقي إشعار من ألمانيا تؤكد حياد بلجيكا، بريطانيا تعلن الحرب على ألمانيا.

- 6 أغسطس: النمسا-المجر تعلن الحرب على روسيا.

- 23 أغسطس: اليابان، تحترم التحالف البريطاني الياباني، وتعلن الحرب على ألمانيا.

- 25 أغسطس: اليابان تعلن الحرب على النمسا-المجر.

اغتيال الأرشدوق فرانتس فرديناند من النمسا على يد وحدوي صربي، 28 يونيو 1914

في 28 يوليو 1914، أرشدوق فرانتس فرديناند من النمسا، وريث عرش النمسا-المجر، وزوجته، صوفي، دوقة هوهنبرگ، يقتلان بالرصاص[52] في سراييڤو، على يد گاڤيرلو پرينسيپ، مجموعة من ستة أشخاص (خمسة صرب وواحد بوشناقي) بتخطيط دانيلو إليتش، صربي بوسنوي وعضو في منظمة اليد السوداء السرية.

حمل الاغتيال أهمية كبيرة حيث كان ينظر إليه من قبل النمسا-المجر كتحدي وجودي لها وقدم في رأيها دافع للحرب مع صربيا. كان الامبراطور النمساوي فرانز يوزف في الرابعة والثمنين من عمره، بالتالي، فإن اغتيال ولي عهده، قبل فترة وجيزة من تنازله المرجح عن العرش، كان بمثابة تحدياً مباشراً للحكم النمساوي. الكثير من وزراء النمسا، خاصة برتشتولد، دعوا إلى وجوب الانتقام من هذا العمل.[53] علاوة على ذلك، فإن الأرشدوق، الذي كان له صوتاً حاسماً تجاه السلام في السنوات السابقة، خرج الىن من دائرة النقاش. أشعل الاغتيال أزمة يوليو، التي تحولت إلى نزاعاً محلياً في أوروپا، ثم إلى حرب عالمية.

النمسا على حافة الحرب مع صربيا

اغتيال الأرشدوق فرانز فرديناند، وريث العرش النمساوي المرتقب، أرسل موجات صادمة عميقة بين النخب النمساوية، وقد وصف القتل بأنه "تأثير 9/11"،، الحدث الإرهابي الذي يحمل مغزى تاريخي، والذي أحدث نقلة في الكيمياء السياسية في ڤيينا". أطلق العنان للعناصر المطالبة بالحرب مع صربي، خاصة في الجيش.[54]

سرعان ما اتضح أن ثلاث أعضاء قياديين من فرقة الاغتيال قد قضوا فترات طويلة في بلگراد، بعد عبورهم مؤخراً الحدود من صربيا، وكانوا يحملون أسلحة وقنابل صناعة صربية. كان تحت الرعاية السرية من قبل اليد السوداء، التي كانت أهدافها تتضمن تحرير جميع السلاڤ البوسنيين من الحكم النمساوي، وكان العقل المدبر هو رئيس المخابرات العسكرية الصربي، أپيس.

بعد يومين من الاغتيال، اتفق وزير الخارجية برتشتولد والامبراطور على أن "سياسة الصبر" مع صربيا قد وصلت لنهايتها. خشيت النمسا من أن ظهورها بمظهر الضعف، سوف تشجع جيرانها من الجنوب والشرق، في حين أن الحرب مع صربيا ستضع حداً للمشاكل التي واجهتها الملكية المزدوجة مع صربيا. رئيس الأركان فرانز كونارد فون هوتزندورف قال موجهاً حديثه لصربيا: ”If you have a poisonous adder at your heel, you stamp on its head, you don’t wait for the bite.” [54]

كما كان هناك شعور بأن التأثيرات الأخلاقية للعمل العسكري من شأنها بث حياة جديدة في الهياكل المنهكة لنظام ملكية هابسبورگ، واستعادتها لقوة وحيوية الماضي، وأنه يجب التعامل مع صربيا قبل أن تصبح أكثر قوة من أن تهزم عسكرياً.[55] تضمنت الأصوات الرئيسية الداعية للسلام في السنوات السابقة فرانز فرديناند نفسه. التخلص منه لم يوفر فقد سبب للحرب لكنه كان بمثابة التخلص من أكثر الأشخاص سلمية من ساحة صنع القرارات السياسية.

حيث أن صربي شاركت روسيا في خطر الحرب، طلبت ڤيينا رأي برلين. قدم الألمان دعمهم الغير مشروط للحرب مع صربيا، فيما عُرف "بشيك على بياض". وبدعم من ألمانيا، بدأ النمساويون في إرسال إنذار نهائي، مما أعطى الصرب 48 ساعة للرد على عشرة طلبات. كان النمساويون يأملون أن يتم رفض الإنذار من أجل تقديم ذريعة للحرب مع جار يعتبرونه مضطرباً.

أشار صمويل ر. وليامسون الأصغر إلى دور النمسا-المجر في بدء الحرب. كانت القومية الصربية المقنعة والطموحات الروسية في البلقان تفكك الإمبراطورية، وكانت النمسا-المجر تأمل في حرب محدودة ضد صربيا، وأن يجبر الدعم الألماني القوي روسيا على الابتعاد عن الحرب وإضعاف هيبتها في البلقان.[56]

في هذه المرحلة من الأزمة لم تكن هناك إمكانية لتحديد الدعم الروسي لصربيا، والمخاطر المرتبطة بها. ظل النمساويون يركزون على صربيا لكنهم لم يذعوا أهدافهم الدقيقة سوى في الحرب.[54]

ومع ذلك، بعد أن قررت النمسا الحرب مع الدعم الألماني، كانت بطيئة في التصرف علناً، ولم تقدم الإنذار حتى 23 يوليو، بعد ثلاثة أسابيع من حادث الإغتيال، في 28 يونيو. وهكذا خسرت النمسا التعاطفات المصاحبة بحادث اغتيال سراييڤو وأعطت الانطباع الأكبر لسلطات الوفاق بأن النمسا كانت تستخدم فقط الاغتيالات كذريعة للعدوان.[57]

"شيك على بياض" - ألمانيا تدعم النمسا-المجر، 6 يوليو

في 6 يوليو قدمت ألمانيا دعمها المشروط لحليفتها النمسا-المجر في صراعها مع صربيا- ما عُرف "بشيك على بياض". رداً على طلبها الدعم، قالت ڤيينا أن موقف القيصر هو: في حالة اعترفت النمسا المجر "بحاجتها لاتخاذ تدابير عسكرية ضد صربيا، فعليه أن يشجب عدم استغلالنا للحظة الحالية، والتي تعتبر مواتية لنا ... نحن في هذه الحالة، كما هو الحال مع الآخرين، نعتمد على الدعم الألماني".[58][59]

كان التفكير كما لو أن النمسا - المجر هي الحليف الوحيد لألمانيا، إذا لم تستعد هيبتها، فقد يصبح موقعها في البلقان متضرراً بشكل لا يمكن إصلاحه، مما يشجع المزيد من المطامع الصربية والرومانية.[60] حرب سريعة ضد صربيا لن تقضي عليها فقط، ولكن ربما تؤدي إلى المزيد من المكاسب الدبلوماسية ضد بلغاريا ورومانيا. وستكون هزيمة الصرب بمثابة هزيمة لروسيا وتقليل نفوذها في البلقان.

كانت الفوائد واضحة ولكن كانت هناك مخاطر، وهي أن روسيا ستتدخل وسيؤدي ذلك إلى حرب قارية. ومع ذلك، فقد كان غير مرجح لأن الروس لم ينتهوا بعد من برنامج إعادة التسلح الممول من فرنسا والذي من المقرر أن يكتمل في عام 1917. علاوة على ذلك، لم يعتقدوا أن روسيا، باعتبارها ملكية مطلقة، ستدعم عمليات إعادة الانتشار، وعلى نطاق أوسع، لأن "المزاج السائد في أوروپا كان معاديًا للصرب لدرجة أن روسيا لن تتدخل".[61]

من جهة أخرى، اعتقد الجيش أنه إذا تدخلت روسيا، فإن سان پطرسبورگ تريد الحرب بوضوح، وسيكون ذلك أفضل وقت للقتال، عندما كانت ألمانيا حليفاً مضموناً للنمسا-المجر، لم تكن روسيا مستعدة، وكانت أوروپا متعاطفة معها. بشكل عام، في هذه المرحلة من الأزمة، توقع الألمان أن دعمهم سيعني أن الحرب ستكون قضية محلية بين النمسا والمجر وصربيا. وقد كان هذا صحيحاً خاصة إذا تحركت النمسا بسرعة، "بينما كانت القوى الأوروپية الأخرى لا تزال تشعر بالاشمئزاز من عمليات الاغتيال، ومن المرجح أن تكون متعاطفة مع أي إجراء تتخذه النمسا-المجر".[62]

فرنسا تعود لروسيا، 20–23 يوليو

French President Raymond Poincaré arrived in St. Petersburg for a long-scheduled state visit on 20 July and departed on 23 July. The French and the Russians agreed their alliance extended to supporting Serbia against Austria, confirming the already established policy behind the Balkan inception scenario. As Christopher Clark notes "Poincare had come to preach the gospel of firmness and his words had fallen on ready ears. Firmness in this context meant an intransigent opposition to any Austrian measure against Serbia. At no point do the sources suggest that Poincare or his Russian interlocutors gave any thought whatsoever to what measures Austria-Hungary might legitimately be entitled to take in the aftermath of the assassinations".[63]

On 21 July, the Russian Foreign Minister warned the German ambassador to Russia that "Russia would not be able to tolerate Austria-Hungary's using threatening language to Serbia or taking military measures." The leaders in Berlin discounted this threat of war. German foreign minister Gottlieb von Jagow noted “there is certain to be some blustering in St. Petersburg.” German Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann-Hollweg told his assistant that Britain and France did not realize that Germany would go to war if Russia mobilized. He thought London saw a German "bluff" and was responding with a "counterbluff."[64] Political scientist James Fearon argues from this episode that the Germans believed Russia were expressing greater verbal support for Serbia than they would actually provide, in order to pressure Germany and Austria-Hungary to accept some Russian demands in negotiation. Meanwhile, Berlin was downplaying its actual strong support for Vienna so as to not appear the aggressor, for that would alienate German socialists.[65]

النمسا-المجر تنذر صربيا انذاراً نهائياً، 23 يوليو

في 23 يوليو، أرسلت النمسا-المجر، في أعقاب تحقيقها الخاص في الاغتيالات، إنذاراً نهائياً إلى صربيا يتضمن مطالبها، ويمنحها 48 ساعة للامتثال.

روسيا تحشد- تصاعد الأزمة، 24-25 يوليو

On 24–25 July the Russian Council of Ministers met, and in response to the crisis and despite the fact that she had no alliance with Serbia, agreed to a secret partial mobilisation of over one million men of the Russian Army and the Baltic and Black Sea Fleets. It is worth stressing, since this is a cause of some confusion in general narratives of the war, that this was done prior to the Serbian rejection of the ultimatum, the Austrian declaration of war on 28 July or any military measures taken by Germany. As a diplomatic move this had limited value since the Russians did not make this mobilisation public until 28 July.

The arguments used to support this move in the Council of Ministers were:

- The crisis was being used as a pretext by the Germans to increase their power

- Acceptance of the ultimatum would mean that Serbia would become a protectorate of Austria

- Russia had backed down in the past – for example in the Liman von Sanders affair and the Bosnian Crisis – and this had encouraged the Germans rather than appeased them

- Russian arms had recovered sufficiently since the disasters of 1904–06

In addition Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Sazonov believed that war was inevitable and refused to acknowledge that Austria-Hungary had a right to counter measures in the face of Serbian irredentism. On the contrary, Sazonov had aligned himself with the irredentism, and expected the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian empire. Crucially, the French had provided their clear support for their Russian allies for a robust response in their recent state visit just days before. Also in the background was Russian anxiety of the future of the Turkish straits – "where Russian control of the Balkans would place Saint Petersburg in a far better position to prevent unwanted intrusions on the Bosphorus” [66]

The policy was intended to be a mobilisation against Austria-Hungary only. However, due to Russian incompetence, the Russians realised by 29 July that partial mobilisation was not militarily possible, and as it would interfere with general mobilisation, only full mobilisation could prevent the entire operation being botched. The Russians therefore moved to full mobilisation on 30 July.

Christopher Clark stated "It would be difficult to overstate the historical importance of the meetings of 24 and 25 July"[67] and "In taking these steps, [Russian Foreign Minister] Sazonov and his colleagues escalated the crisis and greatly increased the likelihood of a general European war. For one thing, Russian pre-mobilization altered the political chemistry in Serbia, making it unthinkable that the Belgrade government, which had originally given serious consideration to accepting the ultimatum, would back down in the face of Austrian pressure. It heightened the domestic pressure on the Russian administration...it sounded alarm bells in Austria-Hungary. Most importantly of all, these measures drastically raised the pressure on Germany, which had so far abstained from military preparations and was still counting on the localisation of the Austro-Serbian conflict."[68]

صربيا ترفض الإنذار النهائي، النمسا تعلن الحرب على صربيا، 25-28 يوليو

نظرت صربيا في النهاية في جميع شروط الإنذار النهائي النمساوي قبل أن تصل أخبار من روسيا مؤكدة وجود تدابير تعبئة مسبقة.[69]

صاغ الصرب ردهم على الانذار بطريقة تعطي الانطباع بتقديم تنازلات مهمة ولكن، كما يقول كريستوفر كلارك "في الحقيقة، كان الرد معطراً في النهاية في معظم نقاطه.[70] رداً على رفض الإنذار الأخير، قطعت النمسا على الفورا علاقاتها الدبلوماسية في 25 يوليو وأعلنت الحرب في 28 يوليو.

روسيا- أمر بالتعبئة العامة، 29–30 يوليو

في 29 يوليو 1914، القيصر يأمر بالتعبئة الكاملة، ثم يتغير رأيه بعد استلامه برقية من القيصر ڤيلهلم. بدلاً من ذلك صدرت أوامر بالتعبئة الجزئية. في اليوم التالي، وزير خارجية القيصر، سرگجي سازونوڤ، يقنع نيقولا بالحاجة للتعبئة العامة، ويصدر الأمر في اليوم التالي، 30 يوليو.

Christopher Clark states: "The Russian general mobilisation was one of the most momentous decisions of the July crisis. This was the first of the general mobilisations. It came at the moment when the German government had not yet even declared the State of Impending War"[71]

Why did Russia do this?

- In response to the Austrian declaration of war on 28 July.

- The previously ordered partial mobilisation was incompatible with a future general mobilisation

- Sazonov’s conviction that Austrian intransigence was Germany’s policy, and therefore given that Germany was driving Austria, there was no longer any point in mobilising against Austria only

- France reiterated her support for Russia, and there was significant cause to think that Britain would also support Russia [72]

التعبئة الألمانية والحرب مع روسيا وفرنسا، 1-3 أغسطس

On 28 July, Germany learned through its spy network that Russia had implemented its "Period Preparatory to War".[بحاجة لمصدر] The Germans assumed that Russia had, after all, decided upon war and that her mobilisation put Germany in danger.[بحاجة لمصدر] This was doubly so because German war plans, the so-called Schlieffen Plan, relied upon Germany to mobilise speedily enough to defeat France first (by attacking largely through neutral Belgium) before turning to defeat the slower-moving Russians.

Christopher Clarke states: "German efforts at mediation – which suggested that Austria should “Halt in Belgrade” and use the occupation of the Serbian capital to ensure its terms were met – were rendered futile by the speed of Russian preparations, which threatened to force the Germans to take counter–measures before mediation could begin to take effect" [73]

Thus, in response to Russian mobilisation,[بحاجة لمصدر] Germany ordered the state of Imminent Danger of War (SIDW) on 31 July, and when the Russian government refused to rescind its mobilisation order, Germany mobilised and declared war on Russia on 1 August. Given the Franco-Russian alliance, countermeasures by France were, correctly, assumed to be inevitable and Germany therefore declared war on France on 3 August 1914.

بريطانيا تعلن الحرب على ألمانيا، 4 أغسطس 1914

Following the German invasion of neutral Belgium, Britain issued an ultimatum to Germany on 2 August that she must withdraw or face war. The Germans did not comply and Britain declared war on Germany on 4 August 1914.

Britain's reasons for declaring war were complex. The ostensible reason given was that Britain was required to safeguard Belgium's neutrality under the Treaty of London 1839. The German invasion of Belgium was, therefore, the casus belli and, importantly, legitimized and galvanized popular support for the war.

Strategic risk posed by German control of the Belgian and ultimately French coast was considered unacceptable. German guarantees of post-war behavior were cast into doubt by her blasé treatment of Belgian neutrality. However, the Treaty of London of 1839 had not committed Britain on her own to safeguard Belgium's neutrality. Moreover, naval war planning demonstrated that Britain herself would have violated Belgian neutrality by blockading her ports (to prevent imported goods passing to Germany) in the event of war with Germany.

Rather Britain's relationship with her Entente partners, both France and Russia, were equally significant factors. Edward Grey argued that the secret naval agreements with France (although they had not been approved by the Cabinet) created a moral obligation vis a vis Britain and France.[74]

What is more, in the event that Britain abandoned its Entente friends, it was feared that if Germany won the war, or the Entente won without British support, then, either way, Britain would be left without any friends. This would have left both Britain and her Empire vulnerable to attack.[74]

British Foreign office mandarin Eyre Crowe stated:

"Should the war come, and England stand aside, one of two things must happen. (a) Either Germany and Austria win, crush France and humiliate Russia. What will be the position of a friendless England? (b) Or France and Russia win. What would be their attitude towards England? What about India and the Mediterranean?" [74]

Domestically, the Liberal Cabinet was split and in the event that war was not declared the Government would fall as Prime Minister Asquith, Edward Grey and Winston Churchill made it clear they would resign. In that event, the existing Liberal Cabinet would lose their jobs. Since it was likely the pro-war Conservatives would be elected to power this would lead to a slightly belated British entry into the war in any event, so wavering Cabinet ministers were also likely motivated by the desire to avoid senselessly splitting their party and sacrificing their jobs.[75]

العوامل السياسية الداخلية

السياسات الداخلية الألمانية

Left-wing parties, especially the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD), made large gains in the 1912 German election. German government at the time was still dominated by the Prussian Junkers who feared the rise of these left-wing parties. Fritz Fischer famously argued that they deliberately sought an external war to distract the population and whip up patriotic support for the government.[76] Indeed, one German military leader Moritz von Lynker, the chief of the military cabinet, favored war in 1909 because it was "desirable in order to escape from difficulties at home and abroad."[77] Conservative Party leader Ernst von Heydebrand und der Lasa suggested that "a war would strengthen patriarchal order".[78]

Other authors argue that German conservatives were ambivalent about a war, worrying that losing a war would have disastrous consequences, and even a successful war might alienate the population if it were lengthy or difficult.[21] Scenes of mass "war euphoria" were often doctored for propaganda purposes, and even those scenes which were genuine would not be reflective of the general population; many German people at the time complained of a need to conform to the euphoria around them, which allowed later Nazi propagandists to "foster an image of national fulfillment later destroyed by wartime betrayal and subversion culminating in the alleged Dolchstoss (stab in the back) of the army by socialists".[79]

المتحكمون في سياسة النمسا-المجر

The argument that Austro-Hungary was a moribund political entity, whose disappearance was only a matter of time, was deployed by hostile contemporaries to suggest that the empire's efforts to defend its integrity during the last years before the war were in some sense illegitimate.[80]

Clark states: "Evaluating the prospects of the Austo-Hungarian empire on the eve of the first world war confronts us in an acute way with the problem of temporal perspective....The collapse of the empire amid war and defeat in 1918 impressed itself upon the retrospective view of the Habsburg lands, overshadowing the scene with auguries of imminent and ineluctable decline."[81]

It is true that in Austro-Hungary, the political scene of the last decades before the war were increasingly dominated by the struggle for national rights among the empire's eleven official nationalities – German, Hungarians, Czechs, Slovaks, Slovenes, Croats, Serbs, Romanians, Ruthenians, Poles and Italians. Yet before 1914, radical nationalists seeking full separation from the empire were still in a small minority and the roots of Austro-Hungary’s political turbulence went less deep than appearances suggested.

In fact, during the pre-war decade the Habsburg lands passed through a phase of strong economic growth with a corresponding rise in general prosperity. Most inhabitants of the empire associated the Habsburg state with the benefits of orderly government, public education, welfare, sanitation, the rule of law, and the maintenance of a sophisticated infrastructure.

Christopher Clark states: "Prosperous and relatively well administered, the empire, like its elderly sovereign, exhibited a curious stability amid turmoil. Crises came and went without appearing to threaten the existence of the system as such. The situation was always, as the Viennese journalist Karl Kraus quipped, ‘desperate but not serious’."[82]

المتحكمون في السياسية الصربية

The principal drivers of Serbian policy were to consolidate the Russian-backed expansion of Serbia during the Balkan wars of 1912-13 and achieve dreams of a Greater Serbia, which included “unification” of lands with large ethnic Serb populations inside the Austro-Hungarian Empire, including Bosnia [83]

Overlaying this was a culture of extreme nationalism, and a cult of assassination, derived from the slaying of the Ottoman Sultan as the heroic epilogue to the otherwise disastrous Battle of Kosovo on 28 June 1389. Clark states: “The Greater Serbian vision was not just a question of government policy, however, or even of propaganda. It was woven deeply into the culture and identity of the Serbs”.[83]

Serbian policy was complicated by the fact that the main actors in 1914 were both the official Serb government led by Nikola Pašić and the “Black Hand” terrorists led by the Head of Serb Military Intelligence, known as Apis. The Black Hand believed that a Greater Serbia would be achieved by provoking a war with Austro-Hungary through an act of terror which, with Russian backing, would be won.

The official government position was to focus on consolidating the gains made during the Balkan war, and avoid any further conflict, since recent wars had somewhat exhausted the Serb state. Nevertheless, the official policy was muted by the political necessity of simultaneously and clandestinely supporting dreams of a Greater Serb state in the long-term.[84] The Serb government found it impossible to put and end to the machinations of the Black Hand for fear it would itself be overthrown. Clark states: “Serbian authorities were partly unwilling and partly unable to suppress the irredentist activity that had given rise to the assassinations in the first place” [85]

Russia, for its part, tended to support Serbian as a fellow Slav state and considered Serbia her “client”. Russia also encouraged Serbia to focus its irredentism against Austro-Hungary because it would discourage conflict between Serbia and Bulgaria (another prospective Russian ally) in Macedonia.

الاستعمارية

أثر التنافس والعدوان الاستعماري في أوروپا 1914

Imperial rivalry, and the consequences of the search for imperial security or for imperial expansion, had important consequences for the origins of the First World War.

Imperial rivalries between France, Great Britain, Russia and Germany played an important part in the creation of the Triple Entente and the relative isolation of Germany. Imperial opportunism, in the form of the Italian attack on Ottoman Libyan provinces, also encouraged the Balkan wars of 1912-13, which changed the balance of power in the Balkans to the detriment of Austro-Hungary.

Some historians, such as Margaret MacMillan, believe that Germany created its own diplomatic isolation in Europe in part through an aggressive and pointless imperial policy, known as Weltpolitik. Others, such as Clark, believe that German isolation was the unintended consequence of a détente between Great Britain, France and Russia. This détente was driven by Britain’s desire for imperial security in relation to France in North Africa and in relation to Russia in Persia and India.

Either way, this isolation is important for the causes of WW1 because it left Germany few options but to ally herself more strongly with Austro-Hungary, leading ultimately to unconditional support for Austria’s punitive war on Serbia during the July crisis of 1914.

عزل ألمانيا: تبعات الڤلتپلتپوليتيك؟

Germany's Chancellor in the 1870s and 1880s Otto von Bismarck disliked the idea of an overseas empire. Rather Bismarck supported French colonization in Africa because it diverted government attention and resources away from continental Europe and revanchism post 1870. Germany's "New Course" in foreign affairs, termed "Weltpolitik" ("world policy”) was adopted in the 1890s after Bismarck's dismissal.

The aim of Weltpolitik was ostensibly to transform Germany into a global power through assertive diplomacy, the acquisition of overseas colonies, and the development of a large navy.

Some historians, notably MacMillan and Hew Strachan, believe that a consequence of the policy of Weltpolitik and the associated assertiveness was to isolate Germany.

Weltpolitik, particularly as expressed in Germany’s objections to France’s growing influence in Morocco in 1904 and 1907, also helped cement the Triple Entente. The Anglo-German Naval race also isolated Germany by reinforcing Britain’s preference for agreements with Germany’s continental rivals, France and Russia.

عزل ألمانيا: تبعات الوفاق الثلاثي؟

Historians, including Ferguson and Clark, believe that Germany’s isolation was the unintended consequences of the need for Britain to defend her Empire against threats from France and Russia. They also downplay the impact of Weltpolitik and the Anglo-German naval race, which ended in 1911.

Britain and France signed a series of agreements in 1904,which became known as the Entente Cordiale. The most important feature of the agreement was that it granted freedom of action to the UK in Egypt and to France in Morocco. Equally, the Anglo-Russian Convention of 1907 is the common name used for the Convention between the United Kingdom and Russia relating to Persia, Afghanistan, and Tibet. The convention brought shaky British–Russian relations to the forefront by solidifying boundaries that identified respective control in Persia, Afghanistan, and Tibet.

The alignment between Great Britain, France and Russia became known as the Triple Entente. Therefore, the Triple Entente was not conceived as a counterweight to the Triple Alliance, but rather as a formula to secure imperial security between these three powers. The impact of the Triple Entente was therefore twofold, to improve British relations with France and her ally Russia and to demote the importance to Britain of good relations with Germany. Clark states it was "not that antagonism toward Germany caused its isolation, but rather that the new system itself channeled and intensified hostility towards the German Empire".

الانتهازية الامبراطورية: إيطاليا- العثمانيون

دارت الحرب الإيطالية التركية 1911-12 بين الدولة العثمانية ومملكة إيطاليا في شمال أفريقيا. كانت الأهمية الرئيسية للحرب العالمية الأولى أنها كانت الحرب التي أعلنت أنه لا يوجد قوى عظمى ترغب في دعم الدولة العثمانية بعد ذلك ومهد هذا الطريق لحروب البلقان.

الانتهازية الاستعمارية: فرنسا- شمال أفريقيا

كان وضع المغرب كان مضموناً عن طريق اتفاقية دولية، وعندما حاولت فرنسا توسيع نفوذها بشكل كبير هناك دون موافقة جميع الموقعين الآخرين، عارضت ألمانيا ذلك مما أشعل الأزمات المغربية، أزمة طنجة 1905 وأزمة أغادير 1911. كان الهدف من السياسة الألمانية هو دق إسفين بين البريطانيين والفرنسيين، ولكن في كلتا الحالتين نتج تأثير معاكس وعُزلت ألمانيا دبلوماسياً، وكان الأثر الأبرز هو فقدان دعم إيطاليا على الرغم من عضوية إيطاليا في التحالف الثلاثي. تأسست محمية فرنسية في المغرب رسمياً عام 1912.

ومع ذلك، عام 1914، كان المشهد الأفريقي مسالماً. كانت القارة مقسمة بالكامل تقريباً بين القوى الاستعمارية (حيث كانت ليبيا وإثيوپيا هما الدولتان المستقلتان الوحيدتان). لم يكن هناك نزاعات كبرى تضع أي قوتين أوروپيتين أمام بعضهما البعض.[86]

التفسير الماركسي

عادة ما يُرجع الماركسيون بداية الحرب للاستعمارية. "الاستعمارية"، كما زعم لنين، "هي مرحلة الاحتكار من الرأسمالية". كان يعتقد أن الرأسماليين الاحتكاريين ذهبوا للحرب للسيطرة على الأسواق والمواد الخام.

الدراونية الاجتماعية

Social Darwinism was a theory of human evolution loosely based on Darwinism that influenced most European intellectuals and strategic thinkers in the 1870-1914 era. These theories emphasized that struggle between nations and "races" was natural and that only the fittest nation deserved to survive.[87] It gave an impetus to German assertiveness as a world economic and military power, aimed at competing with France and Britain for world power. German colonial rule in Africa 1884-1914 was an expression of nationalism and moral superiority that was justified by constructing an image of the natives as "Other". This approach highlighted racist views of mankind. German colonization was characterized by the use of repressive violence in the name of ‘culture’ and ‘civilization’. Germany's cultural-missionary project boasted that its colonial programs were humanitarian and educational endeavors. Furthermore, the wide acceptance among intellectuals of social Darwinism justified Germany's right to acquire colonial territories as a matter of the ‘survival of the fittest’, according to historian Michael Schubert.[88][89]

The model suggested an explanation of why some ethnic groups (called "races" at the time) had been so antagonistic for so long, such as Germans and Slavs. They were natural rivals, destined to clash. Senior German generals such as Helmuth von Moltke talked in apocalyptic terms about the need for Germans to fight for their existence as a people and culture. MacMillan states: "Reflecting the Social Darwinist theories of the era, many Germans saw Slavs, especially Russia, as the natural opponent of the Teutonic races".[90] Social Darwinism extended to Austria, where Conrad, Chief of the Austro-Hungarian General Staff declared: "A people that lays down its weapons seals its fate." [90] In July 1914 the Austrian press described Serbia and the South Slavs in terns which owed much to Social Darwinism.[90]

War was seen as natural and a viable or even useful instrument of policy. "War was compared to a tonic for a sick patient or a life-saving operation to cut out diseased flesh".[90] Since war was natural for some leaders it was simply a question of timing, and it would be therefore better to have a war when the circumstances were most precipitous. “I consider a war inevitable", declared Moltke in 1912, "The sooner the better".[91]

Nationalism made war a competition between peoples, nations or races rather than kings and elites.[92] Social Darwinism carried a sense of inevitability to conflict and downplayed the use of diplomacy or international agreements to end warfare. It tended to glorify warfare, taking the initiative and the warrior male role.[93]

Social Darwinism played an important role across Europe, but J. Leslie has argued that it played a critical and immediate role in the strategic thinking of some important, hawkish members of the Austro-Hungarian government.[94] Social Darwinism therefore normalised war as an instrument of policy and justified its use.

شبكة التحالفات

General narratives of the war tend to emphasis the importance of Alliances in binding the major powers to act in the event of a crisis such as the July crisis. Historians such as Margaret MacMillan warn against the argument that alliances forced the great powers to act as they did during the July crisis. MacMillan states: "What we tend to think of as fixed alliances before the First World War were nothing of the sort. They were much more loose, much more porous, much more capable of change."[95]

The most important alliances in Europe required participants to agree to collective defence if attacked. Some of these represented formal alliances while the Triple Entente represented only a frame of mind. These included:

- German-Austrian treaty (1879) or Dual Alliance

- The Franco-Russian Alliance (1894)

- The addition of Italy to the Germany and Austrian alliance in 1882, forming the "Triple Alliance".

- Treaty of London, 1839, guaranteeing the neutrality of Belgium

There are three notable exceptions which demonstrate that alliances did not in themselves force the great powers to act:

- The "Entente Cordiale" between Britain and France in 1905 included a secret agreement which left the northern coast of France and the Channel to be defended by the British navy only, and the separate "entente" between Britain and Russia (1907) that formed the so-called Triple Entente. However, the Triple Entente between Russia, France and the United Kingdom did not in fact force the United Kingdom to mobilize because it was not a military treaty.

- Moreover, general narratives of the war regularly misstate that Russia was allied to Serbia. Clive Ponting noted: "Russia had no treaty of alliance with Serbia and was under no obligation to support it diplomatically, let alone go to its defence".[96]

- Italy, despite being part of the Triple Alliance did not enter the war in defence of its alliance partners.

سباق التسلح

By the 1870s or 1880s all the major powers were preparing for a large-scale war, although none expected one. Britain focused on building up its Royal Navy, already stronger than the next two navies combined. Germany, France, Austria, Italy and Russia, and some smaller countries, set up conscription systems whereby young men would serve from 1 to three years in the army, then spend the next 20 years or so in the reserves with annual summer training. Men from higher social statuses became officers. Each country devised a mobilisation system whereby the reserves could be called up quickly and sent to key points by rail. Every year the plans were updated and expanded in terms of complexity. Each country stockpiled arms and supplies for an army that ran into the millions. Germany in 1874 had a regular professional army of 420,000 with an additional 1.3 million reserves. By 1897 the regular army was 545,000 strong and the reserves 3.4 million. The French in 1897 had 3.4 million reservists, Austria 2.6 million, and Russia 4.0 million. The various national war plans had been perfected by 1914, albeit with Russia and Austria trailing in effectiveness. Recent wars (since 1865) had typically been short—a matter of months. All the war plans called for a decisive opening and assumed victory would come after a short war; no one planned for or was ready for the food and munitions needs of a long stalemate as actually happened in 1914–18.[97][98]

As David Stevenson has put it, "A self-reinforcing cycle of heightened military preparedness ... was an essential element in the conjuncture that led to disaster ... The armaments race ... was a necessary precondition for the outbreak of hostilities." David Herrmann goes further, arguing that the fear that "windows of opportunity for victorious wars" were closing, "the arms race did precipitate the First World War." If Archduke Franz Ferdinand had been assassinated in 1904 or even in 1911, Herrmann speculates, there might have been no war. It was "... the armaments race ... and the speculation about imminent or preventive wars" that made his death in 1914 the trigger for war.[99]

One of the aims of the First Hague Conference of 1899, held at the suggestion of Tsar Nicholas II, was to discuss disarmament. The Second Hague Conference was held in 1907. All the signatories except for Germany supported disarmament. Germany also did not want to agree to binding arbitration and mediation. The Kaiser was concerned that the United States would propose disarmament measures, which he opposed. All parties tried to revise international law to their own advantage.[100]

سباق التسلح البحري الأنگلو-ألماني

Historians have debated the role of the German naval build-up as the principal cause of deteriorating Anglo-German relations. In any case Germany never came close to catching up with Britain.

Supported by Wilhelm II's enthusiasm for an expanded German navy, Grand Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz championed four Fleet Acts from 1898 to 1912, and, from 1902 to 1910, the Royal Navy embarked on its own massive expansion to keep ahead of the Germans. This competition came to focus on the revolutionary new ships based on the Dreadnought, which was launched in 1906, and which gave Britain a battleship that far outclassed any other in Europe.[101][102]

| القوة البحرية للقوى عام 1914 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| البلدن | الأفراد | السفن البحرية الكبرى (الدريدنوت) |

الحمولة |

| روسيا | 54,000 | 4 | 328,000 |

| فرنسا | 68,000 | 10 | 731,000 |

| بريطانيا | 209,000 | 29 | 2,205,000 |

| الإجمالي | 331,000 | 43 | 3,264,000 |

| ألمانيا | 79,000 | 17 | 1,019,000 |

| النمسا-المجر | 16,000 | 4 | 249,000 |

| الإجمالي | 95,000 | 21 | 1,268,000 |

| (المصدر: [103]) | |||

المصالح الروسية في البلقان والدولة العثمانية

تضمنت الأهداف الروسية الرئيسية تعزيز دور روسيا كحامية لمسيحيي الشرق في البلقان (مثل الصرب).[104] على الرغم من تمتع روسيا باقتصاد مزدهر، عدد سكان متنامي، وقوات مسلحة ضخمة، إلا أن موقفها الاستراتيجي كان مهدداً بتوسعات الجيش التركي المدرب على يد الخبراء الألمان باستخدام التكنولوجيا المتقدمة. جددت بداية الحرب الاهتمام بالأهداف القديمة: طرد التورك من القسنطنيطية، تمديد الهيمنة الروسية في شرق الأناضول وأذربيجان الفارسية، وضم گاليسيا. كانت هذه الفتوحات من شأنها ضمان الغلبة الروسية في البحر الأسود والوصول إلى البحر الأبيض المتوسط.[105]

العوامل التقنية والعسكرية

وهم الحرب القصيرة

Traditional narratives of the war suggested that when the war began both sides believed that the war would end quickly. Rhetorically speaking there was an expectation that the war would be “Over by Christmas” 1914. This is important for the origins of the conflict since it suggests that, given the expectation was that war would be short, the statesmen did not tend to take gravity of military action as seriously as they might have done.

However, modern historiography suggests a more nuanced approach. There is ample evidence to suggest that statesmen and military leaders thought the war would be lengthy, terrible and have profound political consequences.

While it is true all military leaders planned for a swift victory, many military and civilian leaders recognized that the war may be long and highly destructive. The principal German and French military leaders, including Moltke and Ludendorff and his French counterpart Joseph Joffre, expected a long war.[106] The British Secretary of State for War Lord Kitchener expected a long war: "three years" or longer, he told an amazed colleague.

Moltke hoped that a European war, if it broke out, would be resolved swiftly, but he also conceded that it might drag on for years, wreaking immeasurable ruin. Asquith wrote of the approach of ‘Armageddon’ and French and Russian generals spoke of a ‘war of extermination’ and the ‘end of civilization’. Foreign Secretary Grey famously stated just hours before Britain declared war: "The lamps are going out all over Europe, we shall not see them lit again in our life-time”.

Nevertheless, Clark concludes that "In the minds of many statesmen, the hope for a short war and the fear of a long one seemed to have cancelled each other out, holding at bay a fuller appreciation of the risks."[107]

أولوية الهجوم والحرب حسب الجدول الزمني

Military commanders of the time, including Moltke, Joffre and Conrad, held that seizing the offensive was extremely important. This theory encouraged all belligerents to devise war plans to strike first to gain the advantage. These war plans all included complex plans for mobilisation of the armed forces, either as a prelude to war or as a deterrent. In the case of the continental Great Powers the mobilisation plans included arming and transporting millions of men and their equipment, typically by rail and to strict schedules- hence the metaphor "War by Timetable".

These mobilisation plans shortened the window for diplomacy as military planners wanted to begin mobilization as quickly as possible to avoid being caught on the defensive. They also put pressure on policymakers to begin their own mobilisation once it was discovered that other nations had begun to mobilise.

Some historians assert that mobilization schedules were so rigid that once it was begun, they could not be cancelled without massive disruption of the country and military disorganization and so diplomatic overtures conducted after the mobilizations had begun were ignored.[108]

For example, Russia ordered partial mobilisation on 25 July. The policy was intended to be a mobilisation against Austria-Hungary only. However, due to a lack of pre-war planning for this type of partial mobilisation, the Russians realised by 29 July that partial mobilisation was not militarily possible, and as it would interfere with a general mobilisation, only full mobilisation could prevent the entire operation being botched. The Russians were therefore faced with only two options, to cancel mobilisation during a crisis or to move to full mobilisation, which they did on 30 July. This full mobilisation meant mobilising along both the Russian border with Austro-Hungary and the border with Germany.

For their part the German war plans, the so-called Schlieffen plan, assumed a two-front war against France and Russia. They were predicated on massing the bulk of the German army against France, and taking the offensive in the West, while a holding force held East Prussia. The plans were based on the assumption that France would mobilise significantly quicker than Russia. Hence German forces could be deployed in the West to defeat France before turning to face the slow-moving Russians in the East.

On 28 July, Germany learned through its spy network that Russia had implemented partial mobilisation and its "Period Preparatory to War". The Germans assumed that Russia had, after all, decided upon war and that her mobilisation put Germany in danger. This was doubly so because German war plans, the so-called Schlieffen Plan, relied upon Germany to mobilise speedily enough to defeat France first (by attacking largely through neutral Belgium) before turning to defeat the slower-moving Russians.

Christopher Clarke states: "German efforts at mediation – which suggested that Austria should “Halt in Belgrade” and use the occupation of the Serbian capital to ensure its terms were met – were rendered futile by the speed of Russian preparations, which threatened to force the Germans to take counter–measures before mediation could begin to take effect". .[71] Furthermore, Clarke states: "The Germans declared war on Russia before the Russians declared war on Germany. But by the time that happened, the Russian government had been moving troops and equipment to the German front for a week. The Russians were the first great power to issue an order of general mobilisation and the first Russo-German clash took place on German, not on Russian soil, following the Russian invasion of East Prussia. That doesn’t mean that the Russians should be ‘blamed’ for the outbreak of war. Rather it alerts us to the complexity of the events that brought war about and the limitations of any thesis that focuses on the culpability of one actor."[109]

تأريخ

During the period immediately following the end of hostilities, Anglo-American historians argued that Germany was solely responsible for the start of the war. However, academic work in the English-speaking world in the later 1920s and 1930s blamed participants more equally.

Historian Fritz Fischer unleashed an intense worldwide debate in the 1960s on Germany's long-term goals. American historian Paul Schroeder agrees with the critics that Fisher exaggerated and misinterpreted many points. However, Schroeder endorses Fisher's basic conclusion:

- From 1890 on, Germany did pursue world power. This bid arose from deep roots within Germany's economic, political, and social structures. Once the war broke out, world power became Germany's essential goal.[110]

However, Schroeder argues, all that was not the main cause of the war in 1914--Indeed the search for a single main cause is not a helpful approach to history. Instead, there are multiple causes any one or two of which could have launched the war. He argues, "The fact that so many plausible explanations for the outbreak of the war have been advanced over the years indicates on the one hand that it was massively overdetermined, and on the other that no effort to analyze the causal factors involved can ever fully succeed."[111]

Debates over which country "started" the war, and who bears the blame, continues to this day.[112] According to Annika Mombauer a new consensus among scholars had emerged by the 1980s, mainly as a result of Fischer’s intervention:

- Few historians agreed wholly with his [Fischer's] thesis of a premeditated war to achieve aggressive foreign policy aims, but it was generally accepted that Germany’s share of responsibility was larger than that of the other great powers.[113]

Regarding historians inside Germany, she adds, "There was 'a far-reaching consensus about the special responsibility of the German Reich' in the writings of leading historians, though they differed in how they weighted Germany’s role.[114]

انظر أيضاً

- تأريخ أسباب الحرب العالمية الأولى

- التاريخ الدبلوماسي للحرب العالمية الأولى

- تاريخ البلقان

- العلاقات الدولية (1814–1919)

- مؤتمر باريس للسلام 1919

- أسباب الحرب العالمية الثانية

الهوامش

- ^ Van Evera, Stephen (Summer 1984). "The Cult of the Offensive and the Origins of the First World War". International Security. 9 (1): 62. doi:10.2307/2538636. JSTOR 2538636.

- ^ Fischer, Fritz (1975). War of illusions: German policies from 1911 to 1914. Chatto and Windus. p. 69. ISBN 978-0-3930-5480-4.

- ^ Sagan, Scott D. (Fall 1986). "1914 Revisited: Allies, Offense, and Instability". International Security. 11 (2): 151–175. doi:10.2307/2538961. JSTOR 2538961.

- ^ Henig, Ruth (2006). The Origins of the First World War. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-85200-0.

- ^ Lieven, D. C. B. (1983). Russia and the Origins of the First World War. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0-312-69611-5.

- ^ أ ب Jefferies, Matthew (2015). The Ashgate Research Companion to Imperial Germany. Oxon: Ashgate Publishing. p. 355. ISBN 9781409435518.

- ^ MacFie, A. L. (1983). "The Straits Question in the First World War, 1914-18". Middle Eastern Studies. 19 (1): 43–74. JSTOR 4282922.

- ^ أ ب ت Gardner, Hall (2015). The Failure to Prevent World War I: The Unexpected Armageddon. Burlington, VT: Ashgate Publishing. pp. 86–88. ISBN 9781472430564.

- ^ Bideleux, Robert; Jeffries, Ian (1998). A History of Eastern Europe: Crisis and Change. London: Routledge. p. 348. ISBN 978-0415161114.

- ^ Sperber, Jonathan (2014). Europe 1850-1914: Progress, Participation and Apprehension. London: Routledge. p. 211. ISBN 9781405801348.

- ^ Challinger, Michael (2010). ANZACs in Arkhangel. Melbourne: Hardie Grant Publishing. p. 2. ISBN 9781740667517.

- ^ Jean-Marie Mayeur, and Madeleine Rebirioux, The Third Republic from its Origins to the Great War, 1871–1914 (1988)

- ^ G.P. Gooch, Franco-german relations, 1871-1914 (1923).

- ^ Hewitson, Mark (2000). "Germany and France before the First World War: a reassessment of Wilhelmine foreign policy". English Historical Review. 115 (462): 570–606. doi:10.1093/ehr/115.462.570.

- ^ John Keiger, France and the Origins of the First World War (1985) p 81.

- ^ Samuel R. Williamson Jr., "German Perceptions of the Triple Entente after 1911: Their Mounting Apprehensions Reconsidered" Foreign Policy Analysis 7#2 (2011): 205-214.

- ^ Taylor, The Struggle for Mastery in Europe, 1848–1918 (1954) pp 345, 403–26

- ^ G.P. Gooch, Before the war: studies in diplomacy (1936), chapter on Delcassé pp 87-186.

- ^ Strachan, Hew (2005). The First World War. ISBN 9781101153413.

- ^ J.A. Spender, Fifty years of Europe: a study in pre-war documents (1933) pp 212-21.

- ^ أ ب Ferguson (1999).

- ^ أ ب Clark (2013), p. 324. sfnp error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFClark2013 (help)

- ^ Ferguson (1999), p. 53.

- ^ Clark (2013), p. 159. sfnp error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFClark2013 (help)

- ^ Hamilton, K.A. (1977). "Great Britain and France, 1911–1914". In Hinsley, F.H. (ed.). British Foreign Policy Under Sir Edward Grey. Cambridge University Press. p. 324. ISBN 978-0-521-21347-9.

- ^ Clark (2013), p. 157. sfnp error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFClark2013 (help)

- ^ J.A. Spender, Fifty years of Europe: a study in pre-war documents (1933) pp 297-312

- ^ MacMillan, The war that ended peace pp 438-65.

- ^ Falls, Nigel (2007). "The Panther at Agadir". History Today. 57 (1): 33–37.

- ^ Sidney B. Fay, "The Origins of the World War" (2nd ed. 1930): 1:290-93.

- ^ Kaylani, Nabil M. (1975). "Liberal Politics and British-Foreign-Office 1906-1912-Overview". International Review of History and Political Science. 12 (3): 17–48.

- ^ J.A. Spender, Fifty years of Europe: a study in pre-war documents (1933) pp 329-40.

- ^ William C. Askew, Europe and Italy's Acquisition of Libya, 1911–1912 (1942) online

- ^ Clark (2013), p. 242. sfnp error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFClark2013 (help)

- ^ Williamson (1991), pp. 125–140.

- ^ Williamson (1991), pp. 143–145.

- ^ Williamson (1991), pp. 147–149.

- ^ Williamson (1991), pp. 151–154.

- ^ Wohlforth, William C. (April 1987). "The Perception of Power: Russia in the Pre-1914 Balance" (PDF). World Politics. 39 (3): 353–381. doi:10.2307/2010224. JSTOR 2010224.

- ^ Clark, Christopher (17 April 2014). Europe: Then and Now. Center for Strategic and International Studies l. 26-27 minutes in – via YouTube.

- ^ "First World War.com - Who's Who - Otto Liman von Sanders". www.firstworldwar.com.

- ^ Mulligan, William (2017). The Origins of the First World War. United Kingdom: University Printing House. p. 89. ISBN 978-1-316-61235-4.

- ^ Martin, Connor (2017). Bang! Europe At War. United Kingdom. p. 23. ISBN 978-1366291004.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ H E Legge, How War Came About Between Great Britain and Germany[استشهاد ناقص]

- ^ Ponting (2002), p. 124.

- ^ McMeekin, Sean (4 July 2013). "July 1914: Countdown to War". Icon Books Limited – via Google Books.

- ^ Albertini (1952), pp. 461–462, 465, Vol II.

- ^ Joll, James; Martel, Gordon (5 November 2013). "The Origins of the First World War". Routledge – via Google Books.

- ^ "The Willy-Nicky Telegrams - World War I Document Archive". wwi.lib.byu.edu.

- ^ "The Treaty of Alliance Between Germany and Turkey 2 August 1914". Avalon Project. Lillian Goldman Law Library, Yale Law School. 2008.

- ^ Taylor, A.J.P. (1954). The Struggle for Mastery in Europe, 1848-1918. Oxford University Press. p. 524. ISBN 978-0-19-822101-2.

- ^ Martin, Connor (2017). Bang! Europe At War. United Kingdom. p. 20. ISBN 9781389913839.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Martin, Connor (2017). Bang! Europe At War. United Kingdom. p. 23. ISBN 9781389913839.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ أ ب ت Clark, Christopher (25 June 2014). Month of Madness. BBC Radio 4.

- ^ Sked, Alan (1989). The Decline and Fall of the Habsburg Empire: 1815 - 1918. Addison-Wesley Longman. p. 254. ISBN 978-0-582-02530-1.

- ^ Williamson (1991).

- ^ Clark (2013), pp. 402–403. sfnp error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFClark2013 (help)

- ^ Ponting (2002), p. 72.

- ^ Martin, Connor (2017). Bang! Europe At War. United Kingdom. p. 27. ISBN 978-1366291004.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Ponting (2002), p. 70.

- ^ Ponting (2002), p. 73.

- ^ Ponting (2002), p. 74.

- ^ Clark (2013), pp. 449–450. sfnp error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFClark2013 (help)

- ^ Konrad Jarausch, "The Illusion of Limited War: Chancellor Bethmann Hollweg's Calculated Risk," Central European History 2#1 (1969), pp. 48-76 at p. 65.

- ^ James D. Fearon, "Rationalist explanations for war." International organization 49#3 (1995): 379-414 at pp 397-98. online

- ^ Clark (2013), p. 486. sfnp error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFClark2013 (help)

- ^ Clark (2013), p. 475. sfnp error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFClark2013 (help)

- ^ Clark (2013), p. 480. sfnp error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFClark2013 (help)

- ^ Clark (2013), p. 463. sfnp error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFClark2013 (help)

- ^ Clark (2013), p. 466. sfnp error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFClark2013 (help)

- ^ أ ب Clark (2013), p. 509. sfnp error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFClark2013 (help)

- ^ Clark (2013), pp. 510–511. sfnp error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFClark2013 (help)

- ^ Clark (2013), p. 525. sfnp error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFClark2013 (help)

- ^ أ ب ت Clark (2013), p. 544. sfnp error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFClark2013 (help)

- ^ Clark (2013), p. 545. sfnp error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFClark2013 (help)

- ^ Fischer, Fritz (1967). Germany's Aims in the First World War. W. W. Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-09798-6.

- ^ Hull, Isabel V. (2004). The Entourage of Kaiser Wilhelm II, 1888-1918. Cambridge University Press. p. 259. ISBN 978-0-521-53321-8.

- ^ Neiberg, Michael S. (2007). The World War I Reader. NYU Press. p. 309. ISBN 978-0-8147-5833-5.

- ^ Lebow, Richard Ned (2010). Forbidden Fruit: Counterfactuals and International Relations. Princeton University Press. p. 70. ISBN 1400835127. Retrieved 26 September 2018.

- ^ Clark (2013), p. 68. sfnp error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFClark2013 (help)

- ^ Clark (2013), pp. 77–78. sfnp error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFClark2013 (help)

- ^ Clark (2013), p. 77. sfnp error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFClark2013 (help)

- ^ أ ب Clark, Christopher (2013). The Sleepwalkers: How Europe Went to War in 1914. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-219922-5., p.22

- ^ Clark, Christopher (2013). The Sleepwalkers: How Europe Went to War in 1914. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-219922-5., p.26

- ^ Clark, Christopher (2013). The Sleepwalkers: How Europe Went to War in 1914. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-219922-5., p.559

- ^ Mowat, C. L., ed. (1968). The New Cambridge Modern History: Volume 12, The Shifting Balance of World Forces, 1898-1945. Cambridge University Press. pp. 151–152. ISBN 978-0-521-04551-3.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|editorlink=ignored (|editor-link=suggested) (help) - ^ Richard Weikart, "The Origins of Social Darwinism in Germany, 1859-1895." Journal of the History of Ideas 54.3 (1993): 469-488 in JSTOR.

- ^ Schubert, Michael (2011). "The 'German nation' and the 'black Other': social Darwinism and the cultural mission in German colonial discourse". Patterns of Prejudice. 45 (5): 399–416. doi:10.1080/0031322x.2011.624754.

- ^ Felicity Rash, The Discourse Strategies of Imperialist Writing: The German Colonial Idea and Africa, 1848-1945 (Routledge, 2016).

- ^ أ ب ت ث MacMillan, Margaret (2013). The War That Ended Peace: The Road to 1914. Random House. ISBN 978-0-8129-9470-4. p524

- ^ MacMillan, Margaret (2013). The War That Ended Peace: The Road to 1914. Random House. ISBN 978-0-8129-9470-4. p479

- ^ Weikart, Richard (2004). From Darwin to Hitler: Evolutionary Ethics, Eugenics and Racism in Germany. Palgrave Macmillan US. ISBN 978-1-4039-6502-8.[صفحة مطلوبة]

- ^ Hamilton, Richard F.; Herwig, Holger H. (2003). The Origins of World War I. Cambridge University Press. p. 26. ISBN 9780521817356.

- ^ Leslie, John (1993). "The Antecedents of Austria-Hungary's War Aims: Policies and Policymakers in Vienna and Budapest before and during 1914". In Springer, Elibabeth; Kammerhofer, Leopold (eds.). Archiv und Forschung das Haus-, Hof- und Staats-Archiv in Seiner Bedeutung für die Geschichte Österreichs und Europas [Archive and research the Household, Court and State Archives in its importance for the history of Austria and Europe] (in German). Munich, Germany: Verlag für Geschichte und Politik. pp. 307–394.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ Explaining the Outbreak of the First World War - Closing Conference Genève Histoire et Cité 2015; https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uWDJfraJWf0 See13:50

- ^ Ponting (2002), p. 122.

- ^ Hinsley, F. H., ed. (1962). The New Cambridge Modern History: Material progress and world-wide problems, 1870-1898. University Press. pp. 204–242.

- ^ Mulligan (2014), pp. 643–649.

- ^ Ferguson (1999), p. 82.

- ^ Mulligan (2014), pp. 646–647.