السلام الأمريكي

السلام الأمريكي (إنگليزية: American Peace)،[1][2][3] (الاسم اللاتيني "Pax Americana"، على نمط السلام الروماني والسلام البريطاني؛ ويسمى أيضاً السلام الطويل)، هو مصطلح يطبق على مفهوم السلام النسبي في نصف الكرة الغربي ولاحقاً في العالم بعد نهاية الحرب العالمية الثانية عام 1945، عندما أصبحت الولايات المتحدة[4] قوة اقتصادية وعسكرية مهيمنة.

بهذا المعنى، جاء مصطلح السلام الأمريكي لوصف الموقف العسكري والاقتصادي للولايات المتحدة مقارنة بالدول الأخرى. وصفت خطة مارشال، التي أنفقت 13 بليون دولار بعد الحرب العالمية الثانية لإعادة بناء اقتصادات غرب أوروپا، بأنها "إطلاق للسلام الأمريكي".[5]

الفترة المبكرة

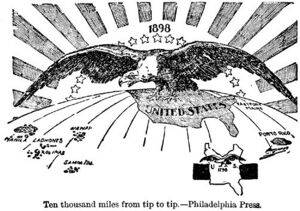

كان أول صياغة لمصطلح "المصطلح الأمريكي" بعد نهاية الحرب الأهلية الأمريكية (حيث قامت الولايات المتحدة بقمع أعظم انشقاقتها وأظهرت القدرة على استخدام الملايين من الجنود المجهزين جيدًا باستخدام التكتيكات الحديثة) في إشارة إلى الطبيعة السلمية للمنطقة الجغرافية لأمريكا الشمالية، واستخدم بشكل متقطع عند بداية الحرب العالمية الأولى. تزامن ظهور المصطلح مع تطور فكرة الاستثنائية الأمريكية. يرى هذا الرأي أن الولايات المتحدة تحتل مكانة خاصة بين الدول المتقدمة[6] من حيث عقيدتها الوطنية وتطورها التاريخي ومؤسساتها السياسية والدينية وأصولها الفريدة. نشأ المفهوم بواسطة ألكسي ده توكڤيل،[7] الذي أكد أن الولايات المتحدة التي كانت تبلغ 50 عامًا احتلت مكانة خاصة بين الأمم لأنها كانت دولة مهاجرين وأول دولة ديمقراطية حديثة. منذ تأسيس الولايات المتحدة في أعقاب الثورة الأمريكية حتى الحرب الإسپانية الأمريكية، كان تركيز السياسة الخارجية الأمريكية إقليميًا وليس عالميًا. كانت السلام الأمريكي، التي فرضها الاتحاد على ولايات وسط أمريكا الشمالية، أحد عوامل الازدهار القومي للولايات المتحدة. كانت الولايات الأكبر محاطة بولايات أصغر، لكن لم يكن لديها أي مخاوف: لا جيوش دائمة تفرض ضرائب وتعوق العمل؛ ولا حروب أو شائعات عن حروب من شأنها أن تقطع سبل التجارة؛ لا يوجد سلام ، بل يوجد أمن، لأن السلام الأمريكي يغطي جميع الولايات داخل الجمهورية الدستورية الفدرالية.[8] وفقًا لقاموس أوكسفورد الإنگليزي، كانت المرة الأولى التي ظهرت فيها العبارة مطبوعة في عدد أغسطس 1894 من "فورم":السبب الحقيقي للابتهاج هو الاندفاع العالمي للوطنية لدعم العمل السريع والشجاع للرئيس كليڤلاند في الحفاظ على سيادة القانون في جميع أنحاء الأرض وعرضها، في تأسيس السلام الأمريكي."[9]

مع صعود الإمبريالية الجديدة في نصف الكرة الغربي مع نهاية القرن التاسع عشر، نشأت مناقشات بين الإمبريالية والفصائل الانعزالية في الولايات المتحدة، هنا تم استخدام مصطلح "السلام الأمريكي" للإشارة إلى السلام عبر الولايات المتحدة، وعلى نطاق أوسع، كسلام لعموم أمريكا تحت رعاية مبدأ مونرو. ومن بين الذين فضلوا السياسات التقليدية لتجنب التشابكات الأجنبية زعيم العمال صموئيل گومپرز وامبراطور الصلب أندرو كارنيگى.

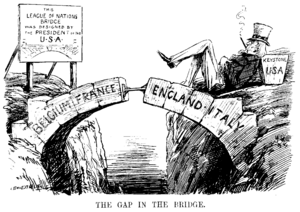

فترة بين الحربين

الحقيقة هي أن الولايات المتحدة هي القوة الوحيدة المتبقية في العالم. إنها الأمة الوحيدة القوية التي لم تدخل في مسيرة الغزو الإمبراطوري، ولا تريد الدخول فيها. [...] لا يوجد في أمريكا سوى القليل من روح العدوان الأنانية التي تكمن في قلب النزعة العسكرية. هنا فقط يوجد أساس عريض "لشعور جديد بالآخوة، ومقياس جديد للقيم الإنسانية". لدينا كره عميق للحرب من أجل الحرب. نحن لا نحب البريق أو المجد. لدينا إيمان قوي بمبدأ الحكم الذاتي. نحن لا نهتم بالسيطرة على الشعوب الأجنبية، بيضاء أو ملونة؛ نحن لا نطمح لأن نكون رومان الغد أو "أسياد العالم". تتركز مثالية الأمريكيين في مستقبل أمريكا، حيث نأمل في العمل على مبادئ الحرية والديمقراطية التي نلتزم بها. هذه المثالية السياسية، هذه النزعة السلمية، هذا الامتناع عن العدوان والرغبة في أن نترك وحدنا لتقرير مصيرنا ظهرت منذ ولادة الجمهورية. لم نتبع نورنا دائمًا، لكننا لم نتخلى عنه مطلقًا.[2]

فترة ما بعد الحربين

يستشهد مؤيدو ومعارضو السياسة الخارجية الأمريكية بعصر السلام الأمريكي الحديث منذ بداية الحرب العالمية الثانية. عام 1941، قبل دخول الولايات المتحدة الحرب، نشر سفير الولايات المتحدة لدى كندا، جيمس كرومويل، كتاباً بعنوان السلام الأمريكي.[10] كما يوحي العنوان، يتصور الكتاب النظام العالمي ما بعد الحرب في ظل السياسة الأمريكية التدخلية. ويؤكد كتاب آخر عن الحرب أن حقبة ما بعد الحرب "قد تُعرف بالسلام الأمريكي". يحتاج العالم والولايات المتحدة على حد سواء إلى السلام الأمريكي، ويجب على الولايات المتحدة أن تُصرّ عليه ولا تقبل بأقل منه.[11] تظهر الانتقادات الصريحة لفكرة السلام الأمريكي في الولايات المتحدة بشكل متزامن.[12]

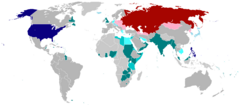

من عام 1945 حتى 1991، كان السلام الأمريكي نظاماً دولياً جزئياً، حيث أنه كان ينطبق فقط على العالم الغربي، وكان من المفضل لدى بعض المؤلفين التحدث عن السلام الأمريكي والسوڤيتي.[13] يركز العديد من المعلقين والنقاد على السياسات الأمريكية من عام 1992 حتى الوقت الحاضر، ولذلك، يحمل هذا المصطلح دلالات مختلفة تبعاً للسياق. على سبيل المثال، يظهر ثلاث مرات في الوثيقة المكونة من 90 صفحة بعنوان إعادة بناء دفاعات أمريكا،[14] ضمن مشروع القرن الأمريكي الجديد، لكن يستخدمه النقاد أيضاً لوصف الهيمنة الأمريكية ومكانة القوة العظمى بأنها إمبريالية في وظيفتها وأساسها. منذ منتصف الأربعينيات تقريباً وحتى عام 1991، هيمنت الحرب الباردة على السياسة الخارجية الأمريكية، وتميزت بحضورها العسكري الدولي الكبير وانخراطها الدبلوماسي المتزايد. وسعيًا لإيجاد بديل لسياسات العزلة التي انتهجتها الولايات المتحدة بعد الحرب العالمية الأولى، وضعت سياسة جديدة تُسمى سياسة الاحتواء لمواجهة انتشار الشيوعية السوڤيتية.

يمكن اعتبار السلام الأمريكي الحديث مشابهاً للسلام الروماني في الإمبراطورية الرومانية. في كلتا الحالتين، كان السلام "نسبياً". خلال عصر السلام الروماني والسلام الأمريكي، استمرت الحروب، لكنها كانت فترة ازدهار للحضارتين الغربية والرومانية. من المهم ملاحظة أنه خلال هذه الفترات، ومعظم فترات الهدوء النسبي الأخرى، لا يعني السلام المشار إليه سلاماً تاماً، بل يعني ببساطة ازدهار الحضارة في مجالاتها العسكرية والزراعية والتجارية والصناعية.

إرث السلام البريطاني

منذ نهاية الحروب الناپوليونية عام 1815 وحتى الحرب العالمية الأولى عام 1914، لعبت المملكة المتحدة دورَ موازنة القوى الخارجية في أوروپا، حيث كان توازن القوى الهدفَ الرئيسي. وفي هذه الفترة أيضًا، أصبحت الإمبراطورية البريطانية أكبر إمبراطورية على مر التاريخ. وقد ضُمنت التفوق العسكري والتجاري البريطاني العالمي بفضل هيمنة أوروپا التي كانت تفتقر إلى دول قومية قوية، ووجود البحرية الملكية في جميع محيطات وبحار العالم. عام 1905، كانت البحرية الملكية متفوقة على أي قوتين بحريتين مجتمعتين في العالم. وقدمت خدماتٍ مثل قمع القرصنة والعبودية.

في عصر السلام هذا، اندلعت عدة حروب بين القوى العظمى: حرب القرم، الحرب الفرنسية النمساوية، الحرب الپروسية النمساوية، الحرب الپروسية الفرنسية، والحرب الروسية اليابانية، بالإضافة إلى حروب أخرى عديدة. ويرى وليام وولفورث أن هذه الفترة من الهدوء، التي تُسمى أحياناً العصر الجميل، كانت في الواقع سلسلة من الدول المهيمنة التي فرضت نظاماً سلمياً. ويضيف وولفورث أن السلام البريطاني تحوّل إلى السلام الروسي، ثم إلى السلام الألماني، قبل أن يتلاشى تماماً، بين عامي 1853 و1871، ليصبح سلاماً من أي نوع.[15]

خلال فترة السلام البريطاني، طورت أمريكا علاقات وثيقة مع بريطانيا، تطورت إلى ما يُعرف بالعلاقة الخاصة بينهما. وقد ساهمت أوجه التشابه العديدة بين البلدين (كاللغة والتاريخ) في توطيد علاقتهما كحليفين. وفي ظل الانتقال المُدار للإمبراطورية البريطانية إلى كومنولث الأمم، كان أعضاء الحكومة البريطانية، مثل هارولد ماكميلان، يُفضلون تشبيه العلاقات بين بريطانيا وأمريكا بعلاقة سلف روما، اليونان، بأمريكا.[16] وعلى مر السنين، كان كلاهما نشطاً في بلدان أمريكا الشمالية والشرق الأوسط وآسيا.

عام 1942، توقعت اللجنة الاستشارية للسياسة الخارجية لما بعد الحرب أن الولايات المتحدة قد تضطر إلى إزاحة الإمبراطورية البريطانية. ولذلك، "يجب على الولايات المتحدة أن تتبنى رؤية ذهنية لتسوية العالم بعد هذه الحرب، رؤيةً تمكنها من فرض شروطها الخاصة، وربما تصل إلى حد السلام الأمريكي".[17] يُؤرَّخ الانتقال من الإمبراطورية البريطانية إلى السلام الأمريكي عادة إلى عام 1947 عندما انتهى الحكم البريطاني في الهند وپاكستان وفلسطين وشرق المتوسط، وأُعلن عن مبدأ ترومان.[18]

أواخر القرن 20

بعد الحرب العالمية الثانية، لم تنشب أي نزاعات مسلحة بين الدول الغربية الكبرى، ولم تُستخدم الأسلحة النووية في أي نزاع مفتوح. كما تأسست الأمم المتحدة في أعقاب الحرب العالمية الثانية مباشرة للمساعدة في الحفاظ على العلاقات السلمية بين الدول، ومنح حق النقض للأعضاء الدائمين في مجلس الأمن الدولي، ومن بينهم الولايات المتحدة.

في النصف الثاني من القرن العشرين، انخرطت القوتين العظميين، الاتحاد السوڤيتي والولايات المتحدة، في الحرب الباردة، التي يمكن اعتبارها نزاعاً بين قوى الهيمنة على العالم. بعد عام 1945، تمتعت الولايات المتحدة بموقع متميز مقارنة ببقية العالم الصناعي. ففي فترة التوسع الاقتصادي التي أعقبت الحرب العالمية الثانية، كانت الولايات المتحدة مسؤولة عن نصف الإنتاج الصناعي العالمي، وتمتلك 80% من احتياطيات الذهب العالمية، وكانت الدولة الوحيدة في العالم التي تمتلك القدرة النووية. وقد أدى الدمار الكارثي الذي لحق بالأرواح والبنية التحتية ورؤوس الأموال أثناء الحرب العالمية الثانية إلى استنزاف الإمبريالية في العالم القديم، سواء المنتصر أو المهزوم. وباعتبارها أكبر اقتصاد في العالم آنذاك، أدركت الولايات المتحدة أنها خرجت من الحرب ببنية تحتية محلية سليمة تقريباً، وبقواتها المسلحة في قوة غير مسبوقة. أدرك المسؤولون العسكريون حقيقة أن السلام الأمريكي كان يعتمد على القوة الجوية الفعالة للولايات المتحدة، تماماً كما كانت أداة السلام البريطاني قبل قرن من الزمان هي سيطرتها على البحر.[19] بالإضافة إلى ذلك، لوحظ حدوث لحظة أحادية القطبية في أعقاب انهيار الاتحاد السوڤيتي.[20]

لقد استخدم جون كندي مصطلح السلام الأمريكي بشكل صريح في الستينيات، حيث عارض الفكرة، بحجة أن الكتلة السوڤيتية تتكون من بشر لديهم نفس الأهداف الفردية للأمريكيين وأن مثل هذا السلام القائم على "الأسلحة الحربية الأمريكية" غير مرغوب فيه:

لذا، اخترتُ هذا الزمان والمكان لمناقشة موضوعٍ يكتنفه الجهل في كثير من الأحيان، ونادرًا ما تُدرك فيه الحقيقة. إنه أهم موضوع على وجه الأرض: السلام. أي سلام أقصد؟ وأي سلام نسعى إليه؟ ليس سلاماً أمريكياً مفروضاً على العالم بأسلحة الحرب الأمريكية، ولا سلام القبر، ولا أمان العبيد. إنما أتحدث عن سلام حقيقي، ذلك السلام الذي يجعل الحياة على الأرض جديرة بالعيش، والذي يمكّن الأفراد والأمم من النمو، ومن الأمل، ومن بناء حياة أفضل لأبنائهم - ليس مجرد سلام للأمريكيين، بل سلام لجميع الرجال والنساء، ليس مجرد سلام في عصرنا، بل سلام في كل زمان.[21]

لم يدّعِ أي رئيس أمريكي آخر مفهوم "السلام الأمريكي". فبينما أشار كندي ورتشارد نكسون وجورج بوش الأب إلى هذا المفهوم، إلا أنهم نفوا وجوده فعلياً وضمنياً. ولهذا السبب، وُصف هذا المفهوم بأنه "غير دبلوماسي".[22]

بدأ مصطلح "السلام الأمريكي" بالظهور تقريباً مع اندلاع حرب ڤيتنام، حيث استخدمه منتقدو الإمبريالية الأمريكية. وفي خضم النزاع الذي دار أواخر القرن العشرين بين الاتحاد السوڤيتي والولايات المتحدة، وُجهت تهمة الاستعمارية الجديدة غالباً إلى التدخل الغربي في شؤون العالم الثالث والدول النامية الأخرى.[23][24][25][26][27] أصبح الناتو يُعتبر رمزاً للسلام الأمريكي في غرب أوروپا:

كان الرمز السياسي المرئي للسلام الأمريكي هو الناتو نفسه ... كان القائد الأعلى للحلفاء، وهو أمريكي دائمًا، عنوانًا مناسبًا للنائب الأمريكي الذي تفوق سمعته ونفوذه على سمعة رؤساء الوزراء والرؤساء والمستشارين الأوروپيين.[28]

في إحدى أولى الانتقادات الموجهة إلى السلام الأمريكي عام 1943، كتب ناثانيال پفر:

ليس ذلك ممكناً ولا مرغوباً فيه... لا يمكن إرساء السلام الأمريكي والحفاظ عليه إلا بالقوة، فقط من خلال إمبريالية جديدة عملاقة تعمل بأدوات العسكرة وما يصاحبها من مظاهر الإمبريالية... إن طريق الهيمنة يمر عبر الإمبراطورية، وثمن الهيمنة هو الإمبراطورية، والإمبراطورية تولد معارضتها الخاصة.[29]

لم يكن يعلم إن كان ذلك سيحدث: "من الممكن أن... تنجرف أمريكا نحو الإمبراطورية، بشكل غير محسوس، مرحلة تلو الأخرى، في نوع من انجذاب السياسة والقوة." وأشار أيضاً إلى أن أمريكا كانت تتجه تحديدًا في هذا الاتجاه: "من الواضح وجود بعض التحركات في هذا الاتجاه، على الرغم من أن مدى عمقها غير واضح".[29]

سرعان ما اتضحت الصورة. فسر اثنان من منتقدي السلام الأمريكي اللاحقين، وهما ميتشيو كاكو وديڤد أكسلرود، نتائج السلام الأمريكي قائلين: "ستُستبدل دبلوماسية البوارج بالدبلوماسية الذرية. وسيحل السلام الأمريكي محل السلام البريطاني. بعد الحرب، ومع انهيار الجيشين الألماني والبريطاني، لم يبقَ سوى قوة واحدة تقف في طريق السلام الأمريكي: الجيش السوڤيتي.[30] بعد أربع سنوات من كتابة هذا النقد، انسحب الجيش الأحمر، ممهداً الطريق للحظة الأحادية القطبية. وقد خلد جوشوا موراڤتيك هذا الحدث بعنوان مقالته عام 1991: "أخيراً، السلام الأمريكي". وقد فصّل ما يلي:

أخيراً وليس آخراً، تُشير حرب الخليج إلى بزوغ فجر ما يُسمى بالسلام الأمريكي. صحيح أن هذا المصطلح استُخدم مباشرة بعد الحرب العالمية الثانية، لكنه كان تسمية خاطئة آنذاك، لأن الإمبراطورية السوڤيتية - المنافس الحقيقي للقوة الأمريكية - وُلدت في اللحظة نفسها. لم تكن النتيجة أي نوع من "السلام"، بل حرب باردة وعالم ثنائي القطب... خلال العامين الماضيين، مع ذلك، انهار الاتحاد السوڤيتي، وتحوّل العالم ثنائي القطب إلى عالم أحادي القطب.[31]

في العام التالي، عام 1992، سُرّبت للصحافة مسودة توجيهات التخطيط الدفاعي لوزارة الدفاع الأمريكية لفترة ما بعد الحرب الباردة. واعترف المسؤول عن ذلك، مساعد وزير الخارجية السابق، پول ولفويتس، بعد سبع سنوات: "عام 1992، سُرّبت مسودة مذكرة أعدها مكتبي في الپنتاگون... إلى الصحافة، وأثارت جدلاً واسعاً". وكانت استراتيجية المسودة تهدف إلى "منع أي قوة معادية من الهيمنة" على منطقة أوراسيا "التي ستكون مواردها، في ظل سيطرة موحدة، كافية لتوليد قوة عالمية". وأضاف: "سخر السناتور جوسف بايدن من الاستراتيجية المقترحة ووصفها بأنها "حرفياً سلاماً أمريكياً ... لن تنجح ..." بعد سبع سنوات فقط، يبدو أن العديد من هؤلاء النقاد أنفسهم مرتاحون تماماً لفكرة السلام الأمريكي".[32] وخلص وليام وولفورث إلى أن فترة ما بعد الحرب الباردة تستحق، بشكل أقل غموضاً، أن تُسمى السلام الأمريكي. وأضاف: "قد يُسيء وصف الفترة الحالية بالسلام الأمريكي الحقيقي إلى البعض، لكنه يعكس الواقع".[15]

القوة المعاصرة

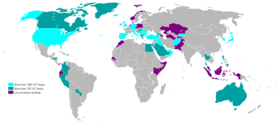

منذ عام 1991،[33] استند مفهوم السلام الأمريكي إلى التفوق العسكري الذي لا يمكن لأي تحالف من القوى المنافسة أن يتحدى قوته، وإلى بسط النفوذ في جميع أنحاء المشاعات العالمية - البحار والجو والفضاء المحايدة. ويُنسق هذا النفوذ من خلال خطة القيادة الموحدة التي تقسم العالم إلى فروع إقليمية تخضع لقيادة واحدة. و"حق القيادة"، المترجم إلى اللاتينية، هو imperium أي "أوامر" (بصيغة الجمع imperia).[34] لطالما ارتبط قادة القوات المقاتلة الأمريكية بالقناصل الرومان[35][36][37][38] وقد خُصص كتاب كامل للمقارنة.[39]

تتكامل معها شبكة عالمية من التحالفات العسكرية (معاهدة ريو، الناتو، اتفاقية أنزوس، وتحالفات ثنائية مع اليابان وعدة دول أخرى) تُنسقها واشنطن في نظام مركزي وشبكة عالمية تضم مئات القواعد والمنشآت العسكرية. ويرى روبرت آرت أن لا معاهدة ريو ولا الناتو "كانتا منظمة أمن جماعي إقليمية؛ بل كانتا إمبراطورية إقليمية تُديرها وتُشغلها الولايات المتحدة".[40] قدم مستشار الأمن السابق زبگنييڤ برجنسكي ملخصاً معبراً للأسس العسكرية للسلام الأمريكي بعد فترة وجيزة من "اللحظة أحادية القطب":

على النقيض من [الإمبراطوريات السابقة]، فإن نطاق وانتشار القوة العالمية الأمريكية اليوم فريدان. لا تتحكم الولايات المتحدة فقط في جميع محيطات العالم، بل إن جحافلها العسكرية تطفو بقوة على الأطراف الغربية والشرقية لأوراسيا ... قارة أوراسيا بأكملها ... التفوق الأمريكي العالمي ... مدعوم بنظام متطور من التحالفات والائتلافات التي تمتد حرفياً عبر العالم.[41]

إلى جانب المؤسسة العسكرية، توجد مؤسسات دولية غير عسكرية هامة مدعومة بالتمويل والدبلوماسية الأمريكية (مثل الأمم المتحدة ومنظمة التجارة العالمية). استثمرت الولايات المتحدة بكثافة في برامج مثل خطة مارشال وفي إعادة إعمار اليابان، مما عزز اقتصادياً العلاقات الدفاعية التي كانت تعزى بشكل متزايد إلى إنشاء الستار الحديدي/الكتلة الشرقية وتوسع الحرب الباردة.

نظراً لموقعها المتميز الذي يُمكّنها من الاستفادة من التجارة الحرة، وعدم ميلها الثقافي للإمبراطوريات التقليدية، وقلقها من صعود الشيوعية في الصين وتفجير أول قنبلة ذرية سوڤيتية، فقد أولت الولايات المتحدة، التي عُرفت تاريخياً بنهجها غير التدخلي، اهتماماً بالغاً بتطوير مؤسسات متعددة الأطراف تُسهم في الحفاظ على نظام عالمي مُواتي. وقد تم إنشاء صندوق النقد الدولي والبنك الدولي للإنشاء والتعمير (البنك الدولي)، وهما جزء من نظام بريتون وودز للإدارة المالية الدولية، واستمر العمل بنظام سعر صرف ثابت مقابل الدولار الأمريكي حتى أوائل السبعينيات. كما وُضعت الاتفاقية العامة للتعريفة الجمركية والتجارة (الگات)، والتي تتضمن پروتوكولاً لتطبيع وتخفيض التعريفات الجمركية.

مع سقوط الستار الحديدي، وزوال مفهوم السلام السوڤيتي، ونهاية الحرب الباردة، احتفظت الولايات المتحدة بقوات مسلحة كبيرة في أوروپا وشرق آسيا. وقد استمرت المؤسسات التي قام عليها السلام الأمريكي وصعود الولايات المتحدة كقوة أحادية القطب حتى مطلع القرن 21. إلا أن قدرة الولايات المتحدة على القيام بدور "شرطي العالم" قد قُيّدت بسبب النفور التاريخي لمواطنيها من الحروب الخارجية.[42] على الرغم من وجود دعوات لاستمرار القيادة العسكرية، كما ورد في "إعادة بناء دفاعات أمريكا":

أثبت السلام الأمريكي أنه سلمي ومستقر ودائم. وفر السلام الأمريكي، على مدى العقد الماضي، الإطار الجيوسياسي للنمو الاقتصادي على نطاق واسع وانتشار المبادئ الأمريكية للحرية والديمقراطية. ومع ذلك، لا يمكن تجميد أي لحظة في السياسة الدولية في الوقت المناسب. حتى السلام الأمريكي العالمي لن يحافظ على نفسه. [... المطلوب هو] جيش قوي وجاهز لمواجهة تحديات الحاضر والمستقبل. سياسة خارجية تروج بجرأة وهادفة للمبادئ الأمريكية في الخارج؛ والقيادة الوطنية التي تقبل المسؤوليات العالمية للولايات المتحدة.[43]

ويتجلى هذا في البحث المتعلق بالإستثنائية الأمريكية، والذي يُظهر أن "هناك بعض المؤشرات على [كونه قائداً 'لسلام أمريكي'] بين الجمهور [الأمريكي]، لكن هناك أدلة قليلة جداً على المواقف الأحادية".[7] وقد نشأت استياءات من اعتماد دولة ما على الحماية العسكرية الأمريكية، بسبب الخلافات مع السياسة الخارجية للولايات المتحدة أو وجود القوات العسكرية الأمريكية.

في عالم ما بعد الشيوعية في القرن 21، يصف السياسي الاشتراكي الفرنسي ووزير الخارجية السابق أوبير ڤيدرين الولايات المتحدة بأنها قوة عظمى مهيمنة، بينما يعارض ذلك عالم السياسة الأمريكي جون ميرشايمر، مؤكداً أن الولايات المتحدة ليست هيمنة "حقيقية"، لأنها تفتقر إلى الموارد اللازمة لفرض حكم عالمي رسمي وفعال؛ فعلى الرغم من قوتها السياسية والعسكرية، إلا أن الولايات المتحدة تُعادل أوروپا اقتصادياً، وبالتالي لا تستطيع السيطرة على الساحة الدولية. وتبرز أو تعود للظهور عدة دول أخرى كقوى عالمية، مثل الصين وروسيا والهند والاتحاد الأوروپي.

عام 1998، وصف الكاتب السياسي الأمريكي تشارلز كوپشان النظام العالمي بأنه "بعد السلام الأمريكي"[44] وفي العام التالي "الحياة بعد السلام الأمريكي".[45] عام 2003، أعلن "نهاية العصر الأمريكي".[46] وفي عام 2012، توقع قائلاً: "ستظل القوة العسكرية الأمريكية محورية للاستقرار العالمي في السنوات المقبلة كما كانت في الماضي".[47]

يرى المحلل الروسي ليونيد گرينين أن السلام الأمريكي سيظل، في الوقت الحاضر وفي المستقبل القريب، أداة فعّالة لدعم النظام العالمي، نظراً لتركز الولايات المتحدة في العديد من وظائف القيادة التي لا تستطيع أي دولة أخرى توليها بالكامل. ولذا، يحذر من أن انهيار السلام الأمريكي سيؤدي إلى تحولات جذرية في النظام العالمي، ذات عواقب غير واضحة.[48]

جادل المحلل السياسي الأمريكي إيان بريمر بأنه مع انتخاب دونالد ترمپ وما تلاه من صعود للشعبوية في الغرب،[49][50] بالإضافة إلى انسحاب الولايات المتحدة من اتفاقيات دولية مثل اتفاقية الشراكة عبر الهادي، ومنطقة التجارة الحرة لأمريكا الشمالية (نافتا)، واتفاق پاريس للمناخ، فإن السلام الأمريكي قد انتهى.[51]

ذكر الكاتب والأكاديمي الأمريكي مايكل ليند أن السلام الأمريكي صمد أثناء الحرب الباردة وما بعدها، وأن "الحرب الباردة الثانية الحالية عززت الإمبراطورية الأمريكية غير الرسمية بدلاً من إضعافها"، على الأقل في الوقت الراهن.[52]

المقارنة بالسلام الروماني

عام 1914، نشر المؤرخ الإيطالي گولييلمو فريرو كتاباً بعنوان روما القديمة وأمريكا الحديثة: دراسة مقارنة للأخلاق والآداب. العنوان مُضلل لأن العمل لا يتناول الولايات المتحدة تحديداً، بل يقارن بين روما وما يسميه فريرو "العالم الجديد"، ويوسع نطاق النقاش ليشمل الحضارة الحديثة عموماً.[53] ومع ذلك، فإن مقارنة فريرو الرائدة ترددت في مقال عام 1961 بقلم ماسون هاموند، بعنوان "إعادة النظر في روما القديمة وأمريكا الحديثة".[54] على الرغم من انتقاده الشديد لاستخدام الماضي في الحاضر، إلا أنه لا يزال يربط بين: "العالم الحديث، مثل عالم البحر المتوسط في القرن الأول ق.م، يواجه خياراً بين الفناء الذاتي ... أو التوحيد والسلام ... روما في القرن الثاني ق.م. والولايات المتحدة اليوم تواجهان، دون استعداد كافي، مسؤوليات الهيمنة العالمية ومعضلة كيفية التوفيق بين الاعتراف بسيادة الدول الأخرى والأمن القومي".[55]

لقد نظر هاموند في خمس لحظات في التاريخ الروماني تقدم أوجه تشابه مغرية مع الوضع الأمريكي الحالي، واقترح الاختلافات التي "تجعل مثل هذه المقارنات خادعة".[56] يشير اثنان من اختلافاته إلى التشابه بين روما عام 150 ق.م. والولايات المتحدة عام 1960. أولًا، تُقدم الفدرالية التمثيلية اليوم حلاً بديلاً للتنافسات الدولية، بديلاً عن مفهوم السلام الأمريكي. "اتجهت روما نحو السيطرة الإمبريالية؛ ولا تزال الولايات المتحدة تأمل في حل فدرالي تعاوني من خلال الأمم المتحدة". وبسبب عدم رغبته في الوثوق بدروس التاريخ، راهن هاموند على فكرة الفدرالية العالمية المثالية. ثانياً، العالم ثنائي القطب، وسيكون من "الحماقة مساواة أنطيوخوس الكبير ملك سوريا في ع. 190 ق.م. أو پارثيا في ع. 150 كمنافسين لروما، مع مساواة روسيا كمنافس للولايات المتحدة" لأن روسيا أكثر قوة.[57] ما أسماه هاموند "الفدرالية التمثيلية" لا يزال قائماً كما كان في أيامه، لكن بعد ثلاثين عاماً من نشره لمقارناته، قفز السلام الأمريكي نسبياً إلى السلام السوڤيتي. وقد ثبت أن هذه المقارنة "مضللة" بالفعل، لكن بمعنى معاكس.

في كتاباته عام 1945، يتذكر لودڤيگ دهيو أن الألمان استخدموا مصطلح السلام الأنگلو-ساكسوني بمعنى السلام الأمريكيمنذ عام 1918 وناقش إمكانية وجود السلام الأنگلو-ساكسوني كنظير عالمي للسلام الروماني.[58] انسحبت الولايات المتحدة، بحسب زملاء دهيو الذين يتفقون معه في الرأي، إلى العزلة في تلك المناسبة. "لقد استغرقت روما أيضاً وقتاً طويلاً لتفهم أهمية دورها العالمي".

مع اندلاع الحرب العالمية الثانية، عزم رئيس الوزراء البريطاني نڤيل تشمبرلين على أن تنتصر إنگلترة في الحرب العالمية الثانية أيضاً، كما انتصرت روما في الحرب البونيقية الثانية. لكن هتلر عارض ذلك، قائلاً إن التاريخ لم يحسم بعد من سيلعب دور روما ومن سيلعب دور قرطاج في هذه الحالة.[59] سرعان ما اتخذت الحرب منحى واضح نحو ما كان الألمان المعاصرون يخشونه باعتباره السلام الأنگلو-ساكسوني المميت. عام 1943، حاول هتلر تشجيع فريقه قائلاً: "لن يصبحوا روما أبداً. لن تكون أمريكا روما المستقبل".[60] لكن في العام نفسه، كان مواطن هتلر ومؤسس الوحدة الأوروپية، ريخارد فون كودنهوفه-كالرگي، الذي وصفه هتلر "باللقيط العالمي"،[61] توقع سلاماً رومانياً جديدأ يستند إلى القوة الجوية الأمريكية المهيمنة:

خلال القرن الثالث ق.م، انقسم عالم البحر المتوسط بين خمس قوى عظمى: روما وقرطاج، مقدونيا، سوريا، ومصر. وأدى توازن القوى إلى سلسلة من الحروب إلى أن برزت روما كملكة للبحر المتوسط، وأرست عهداً لا يُضاهى من السلام والتقدم دام قرنين من الزمان، عُرف 'بالسلام الروماني'. ... ربما تستطيع القوة الجوية الأمريكية أن تُعيد للعالم، الذي أصبح الآن أصغر بكثير من البحر المتوسط في تلك الفترة، مئتي عام من السلام. ... هذا هو الأمل الواقعي الوحيد لسلام دائم.[62]

سرعان ما اكتشف العديد من الباحثين أن ما أسماه كودنهوف-كالرگي "الأمل الواقعي الوحيد للسلام" يتحقق. عام 1953، شجع عالم الكلاسيكيات البريطاني گيلبرت مري على الاعتقاد بأن هناك روما الكبرى تنتظر عبر الأطلسي، والتي يمكنها إرساء السلام العالمي أو على الأقل إبقاء أوروپا في "محيط من البربرية" كما فعلت روما في هـِلاس.[63] في منتصف الستينيات، خلص بعض الباحثين إلى أن الولايات المتحدة قد تفوقت على الاتحاد السوڤيتي بما يتجاوز النموذج ثنائي القطب، ونظرت بدلاً من ذلك إلى نموذج روما.[64] جادل أحد هؤلاء الباحثين، جورج ليسكا، بأن الدول العظمى التاريخية بشكل عام، والإمبراطورية الرومانية بشكل خاص، بدلاً من الإمبراطوريات الاستعمارية الحديثة، لها صلة بالسياسة الخارجية الأمريكية المعاصرة.[65]

في مقدمة كتابه الاستراتيجية الكبرى للإمبراطورية الرومانية عام 1976،[66] أكد إدوارد لوتواك، الموظف في الپنتاگون، أن الولايات المتحدة تسعى لتحقيق أهداف مماثلة لأهداف روما، وتواجه مقاومة مماثلة، وبالتالي يجب عليها تطبيق استراتيجية مماثلة. في أواخر التسعينيات،[67] بدأ الپنتاگون بحثاً جديداً حول "التفوق العسكري في التاريخ" وكيفية الحفاظ عليه. ومن بين أربع إمبراطوريات اختاروها، تم التركيز على روما باعتبارها النموذج الأكثر ملاءمة للولايات المتحدة المعاصرة.[68] وأُرسلت "مجموعة كاملة" من النسخ إلى الحكومة.[67] بعد عشر سنوات، قارن كارنز لورد، الموظف السابق في مجلس الأمن القومي، بين قادة القوات الأمريكية، والقناصل الرومان، والمسؤولين الاستعماريين البريطانيين، والساتراپ الفرس، ونواب الملك الإسپان. ووجد أن النموذج الأمريكي هو الأقرب إلى النموذج القنصلي الروماني.[69]

بينما تحوّل موظفو الپنتاگون ومجلس الأمن القومي إلى مؤرخين رومانيين، سلك المؤرخ الروماني آرثر إيكشتاين مساراً معاكساً. فقد أشار إلى أن الإطار النظري للهرمية، والأحادية القطبية، والإمبراطورية، كما عرّفها علماء السياسة، هو إجراء نادراً ما يُتبع بين دارسي البحر المتوسط في العصور القديمة[70] وقرر سدّ هذه الفجوة. قدّم إيكشتاين موضوعه في سياق العلاقات الدولية في القرن العشرين. كانت المواجهة الدبلوماسية التي استمرت خمس سنوات (196-192 ق.م.) بين روما وأنطيوخوس الثالث صراعاً كلاسيكياً بين القوتين العظميين في "نظام ثنائي القطب".[71]

تحولت المواجهة إلى حرب، وفي عام 189 ق.م، هزمت روما أنطيوخوس. أسفر هذا النصر عن لحظة أحادية القطب غير مسبوقة في عالم البحر المتوسط، حيث ترسخت روما كقوة مهيمنة أحادية القطب. لم يبقى سوى مركز سياسي وعسكري واحد، وقوة مهيمنة واحدة. أصبحت روما القوة العظمى الوحيدة المتبقية. امتد نظام أحادي القطب موحد من إسپانيا إلى سوريا.[72]

الإمبراطورية المناهضة للإمبريالية ليست اختراعاً حديثاً. في البداية، ظهرت روما في الشرق كقوة مناهضة للإمبريالية، نصيراً للدول الأضعف في وجه عدوان القوى العظمى بقيادة فيليپ الخامس المقدوني وأنطيوخوس الثالث.[73] ويضيف پول بيرتون، تلميذ إيكشتاين، أن مسؤول العصبة الآخية ليكورتاس، والد پوليبيوس، فسر السياسة الخارجية الرومانية بكلمات قد تبدو مألوفة لمنتقدي السياسة الخارجية الأمريكية: الرسالة التي يرسلها الرومان من خلال انتقادهم للأخيين هي أن "الحرية، في العقل الروماني، هي أيضاً إمبراطورية" (ليڤيوس 39.36.5 - 37.17).[74]

لكن إيكشتاين حرص على تزويد العالم المعاصر بمخرج طوارئ من هيمنة أمريكا. لم يكن إنجاز الرومان في تحقيق الأحادية القطبية سوى خطوة واحدة على امتداد سلسلة العلاقات بين الدول التي تقود إلى الإمبراطورية. والأحادية القطبية، حتى بعد تحقيقها، قابلة للتراجع. تاريخياً، تكرر هذا الأمر مراراً، وفي أواخر ع. 2000، بدأت الولايات المتحدة تكتشف أن الأحادية القطبية غير مستقرة.[75] عام 2002 كتب جوسف ناي مقالة بعنوان "روما الجديدة تلتقي بالبرابرة الجدد".[76] ويفتتح كتابه الذي صدر في نفس العام قائلاً: "لم تتفوق أمة واحدة على غيرها بهذا الشكل منذ روما".[77] وكتابه الذي صدر عام 1991 بعنوان مُقَدَّر لِلقيادة.[78] القيادة، عند ترجمتها إلى اليونانية، تُصبح الهيمنة؛ وترجمة بديلة هي أرخيا archia- وهي الكلمة اليونانية الشائعة التي تعني "إمبراطورية". ويكتب أن الانحدار ليس بالضرورة وشيكاً. "ظلت روما مهيمنة لأكثر من ثلاثة قرون بعد ذروة قوتها ...[79]

بلغت فكرة السلام الأمريكي ونظيره الروماني ذروتها في سياق الغزو الأمريكي للعراق 2003. وقد أصبحت مقارنة الولايات المتحدة بالإمبراطورية الرومانية مبتذلة إلى حد ما.[80][81]

لاحظ جوناثان فريدلاند ما يلي:

بالطبع، لطالما لوح أعداء الولايات المتحدة بقبضاتهم في وجه "إمبرياليتها" لعقود... لكن الأمر الأكثر إثارة للدهشة، والأحدث عهداً، هو أن فكرة الإمبراطورية الأمريكية أصبحت فجأة موضوع نقاش حاد داخل الولايات المتحدة. فمع تسارع النقاش الذي أعقب أحداث 11 سبتمبر حول دور أمريكا في العالم، بدأت فكرة الولايات المتحدة كروما القرن 21 تترسخ في وعي البلاد.[82]

نشرت نيويورك رڤيو أوف بوكس في مقال لها عام 2002 حول قوة الولايات المتحدة رسماً لجورج بوش وهو يرتدي زي قائد مئة روماني، مكتملاً بدرع ورماح.[83] أسفرت زيارات بوش إلى ألمانيا عامي 2002 و2006 عن ظهور المزيد من الانتقادات اللاذعة التي تُشبّه بوش بالإمبراطور الروماني في الصحافة الألمانية. ففي عام 2006، شبّه الكاتب المستقل والساخر السياسي ومراسل صحيفة داي تاگسزايتونگ اليسارية، أرنو فرانك، مشهد زيارة بوش، الذي وصفه بالإمبراطور، "بجولات التفتيش المُفصّلة التي يقوم بها الأباطرة الرومان في مقاطعات هامة لكنها لم تخضع للسلامة الكاملة، مثل جرمانيا".[84] في سبتمبر 2002، أطلقت محطة راديو WBUR-FM ومقرها بوسطن برنامجاً خاصاً عن القوة الإمبريالية الأمريكية بعنوان "السلام الأمريكي".[85] ظهرت عبارة "الإمبراطورية الأمريكية" في ألف خبر خلال فترة ستة أشهر واحدة عام 2003.[86] عام 2009 أسفرت عمليات البحث على محرك بحث گوگل عن 22 مليون نتيجة بحثٍ لمحلل السياسات ڤاكلاڤ سميل عن عبارة "أمريكا كروما جديدة"، و23 مليون نتيجة بحثٍ عن عبارة "الإمبراطورية الأمريكية". وقد أثار هذا الأمر فضول سميل، فسمى كتابه الصادر عام 2010 بما أراد شرحه: لماذا أمريكا ليست روما جديدة.[87]

أثار حجم المقارنات بين روما والولايات المتحدة حيرة النقاد: "مع تحول التدفق إلى فيضان، يستحيل مواكبة العدد الهائل من المقالات والكتب والمواقع الإلكترونية والأفلام الوثائقية التي تطرح هذه المقارنة. حتى بعد عام 2009... لا يزال عدد الأعمال المتعلقة بروما والولايات المتحدة مستمراً دون أي مؤشر على التراجع".[88]

قرر اثنان من علماء الكلاسيكيات، پول ج. بيرتون[89] وإريك أدلر، أن حجم المقارنات بين أمريكا وروما يستدعي بحثاً خاصاً بهما. وقد كشفت مقارنة أدلر للمقارنات أن معظم دعاة التدخل يفصلون أمريكا عن روما، بينما يؤكد معظم منتقدي التدخلات الأمريكية على أوجه التشابه بينهما. وينطبق الأمر نفسه على النقاشات التي دارت في العصرين الإدواردي والڤيكتوري حول الإمبراطورية البريطانية. يستخدم دعاة الانعزالية القيمة الجدلية "لروما الجديدة" لإثارة صدمة القارئ، بينما يقدم دعاة التدخل للقارئ نفسه علاجاً من خلال التمييز بين روما وأمريكا. لاحظ أدلر أيضاً أن العديد من المؤلفين البارزين يهتمون أكثر بالتعبير عن آرائهم حول السياسة الخارجية الأمريكية الحديثة بدلاً من تقديم تفسير دقيق للتاريخ الروماني مدعوماً بالمصادر الأولية. بدلاً من ذلك، ينتقون من المصادر الثانوية عناصر تتوافق مع توجهاتهم، متجاهلين ما إذا كانت هذه العناصر من روما الجمهورية، أو روما الإمبراطورية، أو حتى الإمبراطورية البيزنطية.[90]

على غرار سميل، ينأى المؤرخ الكلاسيكي والعسكري ڤكتور ديڤس هانسن بالولايات المتحدة عن روما. فالولايات المتحدة من وجهة نظره لا تسعى إلى الهيمنة العالمية، بل تحافظ على نفوذها العالمي من خلال نظام من التبادلات ذات المنفعة المتبادلة.[91] يرفض هانسن فكرة الإمبراطورية الأمريكية رفضاً قاطعاً، مُقارناً إياها بسخرية بالإمبراطوريات التاريخية: "نحن لا نُرسل حكماء للإقامة على الدول التابعة، التي بدورها تفرض ضرائب على رعاياها المكرهين لتمويل جيوشنا. بدلاً من ذلك، تقوم القواعد الأمريكية على التزامات تعاقدية - مكلفة لنا ومربحة لمضيفيها. لا نرى أي أرباح في كوريا، بل نقبل مخاطرة فقدان ما يقرب من 40.000 من شبابنا لضمان تدفق قوات الكيا إلى شواطئنا وتمكّن الطلاب من التظاهر أمام سفارتنا في سول".[91]

إلا أن وجود "القناصل الإقليميين" كان معروفاً لدى الكثيرين منذ بدايات الحرب الباردة. ففي عام 1957، ربط المؤرخ الفرنسي أموري دي رينكور "القنصل الإقليمي" الأمريكي "بروماني عصرنا".[92] رصد الخبير في التاريخ الأمريكي الحديث، آرثر إم. شلزنجر، العديد من السمات الإمبراطورية المعاصرة، بما في ذلك "القناصل الإقليميين". لم تكن واشنطن تدير أجزاء كثيرة من العالم بشكل مباشر، بل كانت "إمبراطوريتها غير الرسمية" مجهزة تجهيزاً كاملاً بالمظاهر الإمبراطورية: "قوات، وسفن، وطائرات، وقواعد عسكرية، وقناصل إقليميين، ومتعاونين محليين، منتشرين على نطاق واسع في أنحاء هذا الكوكب التعيس".[93] "كان لقب القائد الأعلى للحلفاء، وهو لقب أمريكي دائماً، لقباً مناسباً للحاكم الأمريكي الذي فاقت سمعته ونفوذه سمعة ونفوذ رؤساء الوزراء والرؤساء والمستشارين الأوروپيين".[94] عمل "قادة القوات المقاتلة الموحدة الأمريكية...كحكام إقليميين. وعادة ما كانت مكانتهم في مناطقهم تفوق مكانة السفراء ومساعدي وزراء الخارجية".[95][96][97]

في كتابه الصادر عن 2002 عن الإمبراطورية الأمريكية، خصص أندرو باسڤيتش فصلاً بعنوان "صعود القناصل"، حيث حدد فيه فئة جديدة من القناصل الإقليميين الذين يرتدون الزي العسكري ويترأسون مناطق شاسعة "شبه إمبراطورية" ظهرت في التسعينيات.[98] في سبتمبر 2000، نشرت دانا پريست، مراسلة صحيفة واشنطن پوست، سلسلة مقالات تمحورت حول النفوذ السياسي الهائل الذي يتمتع به قادة العمليات العسكرية في البلدان الواقعة ضمن مناطق مسؤوليتهم. وقد وصفتهم بأنهم "تطوروا ليصبحوا بمثابة نظير حديث لقناصل الإمبراطورية الرومانية - مراكز غير تقليدية للسياسة الخارجية الأمريكية، تتمتع بتمويل جيد وشبه استقلال ذاتي".[99] يرد كتاب بعنوان نواب ملوك أمريكا على پريست، مدعياً أن قادة القوات الأمريكية لا يشكلون أي تهديد بالزحف على واشنطن، بينما "لطالما شكل" القناصل الرومان مثل هذا التهديد.[100][101] مع ذلك، يُقلّص العديد من المؤرخين الرومان فترة التهديد من "دائمة" إلى القرن الأخير من عمر الجمهورية (133-131 ق.م.). أحد أبرز القناصل الرومان الذين حققوا لروما السيادة على البحر المتوسط، سكيپيو الأفريقي، لم يُوفق في حملة عام 184 ق.م. لفرض الرقابة، فاعتزل السياسة. تأسست الجمهورية حوالي عام 509 ق.م، وظلت تُسيطر سيطرةً تامة على قناصلها. يستبعد ستيفن راج حدوث أي تعقيدات مستقبلية مع القادة العسكريين،[102] بينما يتوخى بعض المؤرخين الرومان الحذر، مفترضين أن الولايات المتحدة قد تكون في التسلسل الروماني "في مكان ما بين حروب الفتح الكبرى [202-146 ق.م.] وصعود الأباطرة".[103][104][105]

يلاحظ كارنز لورد أنه منذ ع. 2000، أصبحت فكرة أن القادة المقاتلين هم في الواقع "القناصل" لإمبراطورية أمريكية جديدة فكرة شائعة في الأدبيات المتعلقة بالسياسة الخارجية الأمريكية.[106] يصف أستاذ جامعة هارڤرد نيال فرگسون القادة المقاتلين الإقليميين، الذين ينقسم العالم بأسره بينهم، بأنهم "القناصل" لهذه "الإمبراطورية".[107] بينما يصفهم گونتر بيشوف بأنهم "القناصل الأقوياء للإمبراطورية الأمريكية الجديدة. ومثل قناصل روما، كان من المفترض أن يجلبوا النظام والقانون إلى العالم الجامح والفوضوي".[108] غالباً ما كان الرومان يفضلون ممارسة السلطة من خلال أنظمة عملاء موالية لهم، بدلاً من الحكم المباشر: "حتى أصبح جاي گارنر ول. پول بريمر قنصلين أمريكيين في بغداد، كانت هذه هي الطريقة الأمريكية أيضاً".[109]

خصص كارنز لورد كتاباً للمقارنة بين القناصل الرومان، والمسؤولين الاستعماريين البريطانيين، وقادة القوات الأمريكية. ويربط هؤلاء الأخيرين أيضاً بالساتراپات الفرس ونواب الملك الإسپان. ووجد أن النموذج الأمريكي هو الأقرب إلى النموذج الروماني للقناصل. ونظراً لمساهمتهم الكبيرة في السياسة على أطراف الإمبراطورية، فإنهم جميعاً مؤهلون ليكونوا قناصل بالمعنى الدقيق للكلمة. ومع كل التحفظات، أقر بأن دراسته تتناول الحكم الإمبراطوري في المناطق المحيطة بالإمبراطورية.[106]

يُعبّر تمييز آخر لڤكتور ديڤس هانسن - وهو أن القواعد الأمريكية، على عكس ما يشاع، تكلف أمريكا الكثير وتدر ربحاً للدول المضيفة - عن وجهة النظر الأمريكية. أما الدول المضيفة فتُعبر عن وجهة نظر مغايرة تماماً. تدفع اليابان رواتب 25.000 ياباني يعملون في القواعد الأمريكية. 20% من هؤلاء العمال يقدمون خدمات الترفيه: فقد تضمنت قائمة أعدتها وزارة الدفاع اليابانية 76 نادلاً، و48 عاملاً في آلات البيع، و47 عامل صيانة ملاعب گولف، و25 مدير نادي، و20 فناناً تجارياً، و9 مُشغلي قوارب ترفيهية، و6 مخرجين مسرحيين، و5 مزينين للكعك، و4 موظفين في صالات البولينگ، و3 مرشدين سياحيين، وعامل رعاية حيوانات واحد. يتساءل شو واتانابى من الحزب الديمقراطي الياباني: "لماذا تتحمل اليابان تكاليف ترفيه أفراد الخدمة الأمريكية في عطلاتهم؟".[110] خلصت إحدى الدراسات حول دعم الدول المضيفة إلى أن الاتجاه العام لتقاسم أعباء التحالف بين كوريا الجنوبية واليابان يتجه نحو الزيادة.[111] إن زيادة "الأعباء الاقتصادية على الحلفاء" هي إحدى الأولويات الرئيسية للرئيس دونالد ترمپ.[112]

يشير الباحث في الدراسات الكلاسيكية، إريك أدلر، إلى أن هانسون كان قد كتب سابقاً عن تراجع الدراسات الكلاسيكية في الولايات المتحدة، وعن عدم إيلاء الاهتمام الكافي للتجربة الكلاسيكية. "لكن عندما كتب هانسون عن السياسة الخارجية الأمريكية لجمهور غير متخصص، اختار أن ينتقد الإمبريالية الرومانية ليصوّر الولايات المتحدة الحديثة على أنها مختلفة عن الدولة الرومانية، بل ومتفوقة عليها".[113] وباعتباره مؤيداً لسياسة خارجية أمريكية أحادية الجانب متشددة، فإن "نظرة هانسون السلبية بشكل واضح للإمبريالية الرومانية جديرة بالملاحظة بشكل خاص، لأنها توضح الأهمية التي يوليها مؤيد معاصر لسياسة خارجية أمريكية متشددة لانتقاد روما".[113]

يذكر الباحثون العديد من أوجه التشابه الإضافية مع السلام الروماني المبكر (خاصةً بين عام 189 ق.م، عندما تحققت السيادة على البحر المتوسط، وأول ضم عام 168 ق.م.). وعلى عكس الإمبراطوريات الأخرى، لم يفرض السلام الروماني المبكر ضرائب منتظمة على الدول الأخرى.[114][115] أول دليل جيد على مثل هذه الضرائب يأتي من يهودا في وقت متأخر يعود إلى عام 64 ق.م.[116] قدمت الدول العميلة إسهامات عسكرية أو اقتصادية غير نظامية في حالة الحملات المهيمنة، كما هو الحال في ظل السلام الأمريكي.[117]

رسمياً، ظلت الدول العميلة مستقلة، ونادراً ما كانت تُسمى "عميلة". لم يُستخدم هذا المصطلح الأخير على نطاق واسع إلا في أواخر العصور الوسطى. عادة، كانت الدول الأخرى تُسمى "أصدقاء وحلفاء" - وهو تعبير شائع في ظل السلام الأمريكي. وقد أكد أرنولد توينبي على تشابه تحالفات الولايات المتحدة مع نظام الدول العميلة الروماني[118] وقد استشهد رونالد ستيل بنظير توينبي بالتفصيل في كتابه الذي يحمل عنوان السلام الأمريكي.[119] عُرضت الحماية الرومانية أو الأمريكية على الحلفاء المستقلين اسمياً، وهو ما يعني، وفقاً لپيتر بندر، سيطرتهم وحدودهم على سيادة الدول الأخرى.[120] لخص بندر في مقالته التي نشرها عام 2003 بعنوان "أمريكا: الإمبراطورية الرومانية الجديدة" قائلاً: "عندما يحتاج السياسيون أو الأساتذة إلى مقارنة تاريخية لتوضيح القوة الهائلة للولايات المتحدة، فإنهم يفكرون دائماً تقريباً في الإمبراطورية الرومانية".[121] المقال مليء بالتشبيهات. وبالمثل، كان الرومان منعزلين حتى توسعوا خارج إيطاليا.[122] إن العامل المؤدي إلى الانخراط الخارجي هو نفسه في كلتا الحالتين: البحار أو المحيطات توقفت عن توفير الحماية، أو هكذا بدا الأمر:

توسعت كل من روما وأمريكا سعياً لتحقيق الأمن. وكما في الدوائر المتداخلة، طالبت كل دائرة بحاجة إلى الأمن باحتلال الدائرة الأكبر التالية. شقّ الرومان طريقهم حول البحر المتوسط، مدفوعين من مهدد لأمنهم إلى آخر. أما الصراعات... فقد دفعت الأمريكيين إلى أوروپا وشرق آسيا؛ وسرعان ما انتشروا في جميع أنحاء العالم، مدفوعين من محاولة احتواء إلى أخرى. تلاشت الحدود بين الأمن وسياسة القوة تدريجياً. ووجد كل من الرومان والأمريكيين أنفسهم في نهاية المطاف في وضع جغرافي وسياسي لم يرغبوا فيه في البداية، لكنهم قبلوه بسرور وحافظوا عليه بحزم.[123]

ادعت كل من روما والولايات المتحدة الحق المطلق في تحييد أعدائهم نهائياً. وكانت معاملة قرطاج ومقدونيا وألمانيا واليابان بعد الحرب مماثلة. فعندما وسّعت هذه الدول نفوذها لاحقاً إلى أراضٍ ما وراء البحار، تجنّبت السيطرة المباشرة قدر الإمكان. وفي العالم الهليني، سحبت روما جحافلها بعد ثلاث حروب، واكتفت بدور الراعي والحكم ذي النفوذ المطلق.[124] "القوى العالمية التي لا منافس لها تشكل فئة فريدة من نوعها. فهي... تسارع إلى تسمية أتباعها المخلصين بالأصدقاء، أو "أميكوس پوپولي روماني". لم تعد تعرف الأعداء، بل تُسمّيهم بالمتمردين والإرهابيين والدول المارقة. لم تعد تُقاتل، بل تُعاقب فقط. لم تعد تُشنّ الحروب، بل تسعى فقط إلى إحلال السلام. وهي تُصاب بالغضب الشديد عندما لا يتصرف التابعون كتابعين".[125] يعلق زبگنييڤ برجنسكي على التشبيه الأخير قائلاً: "قد يميل المرء إلى إضافة أنهم لا يغزون البلدان الأخرى، بل يحررونها فقط".[126]

اعتبر بعض العلماء أن المذبحة المثريداتية للمواطنين الرومان عام 88 ق.م. هي "لحظة 11 سبتمبر" لروما، ووصفوا الطرق التي تشبه بها تقلبات السلام الأمريكي المعاصر رد فعل روما على الثورة المثريداتية.[127][128] استخدم روبرت فيسك هذا الربط ليزعم أن السلام الروماني كان أكثر قسوة من السلام الأمريكي: فبعد المذبحة، قام الرومان "بصلب أعدائهم حتى الفناء. لم تكن لحقوق الإنسان أي أبعاد في روما القديمة".[129] بدلاً من ذلك، يُعرّف ماكس أوستروڤسكي هذه الاستنتاجات بأنها مسبقة التحديد ولا علاقة لها بما حدث فعلاً. لم تحدث عملية صلب جماعي. بعد هزيمة المثريداتيين عام 84 ق.م، أبرم لوقيوس كورنليوس صولا معهم صلحاً واعترف بهم كأصدقاء وحلفاء لروما. لا يمكن لأي حاكم حديث أن ينجو من مذبحة 80.000 مواطن أمريكي، لا في السلطة ولا على الأرض.[130]

في تلك المناسبة، بدا تسامح السلام الروماني مبالغاً فيه وفقاً للمعايير القديمة والحديثة على حد سواء. تساءل شيشرون (في كتابه عن إمپريوم گنايوس پومپيوس) كيف بقي مثريداتس على العرش وسُمح له بإشعال حربين أخريين ضد الرومان. فقط بعد الحرب المثريداتية الثالثة عام 64 ق.م، وضع پومپي حداً نهائياً لملكه وضم المملكة المتمردة.

إلى جانب كتب فاتسلاڤ سميل وپيتر بندر، هناك كتاب مخصص بالكامل للمقارنة بين روما والولايات المتحدة وهو كتاب إمبراطوريات الثقة للمؤرخ الروماني توماس مادن.[131] يُقدّم مادن العديد من أوجه التشابه، يتفق الكثير منها مع بندر، مثل بداية كلتا الإمبراطوريتين كمجتمعات حدودية واتباعهما سياسة انعزالية، ثم نمطهما اللاحق المتمثل في الإمبريالية الدفاعية، وتحالفهما مع دول أخرى بدلاً من غزوها. وإلى جانب الأسباب والأنماط، يولي اهتماماً كبيراً للنتائج المماثلة للسلام الروماني والسلام الأمريكي. إذ يؤدي القضاء على التهديد الخارجي إلى تراجع الهيمنة الاجتماعية الداخلية.

يربط معظم الكتاب، القدماء والمعاصرين، بين تأسيس الإمبراطورية الرومانية وسقوط الجمهورية، ويربطون بينهما بشكل مباشر، وغالباً ما تُطبق هذه الفرضية على الولايات المتحدة. ويحذر الخبراء المعاصرون من أن تزايد النزعة الإمبريالية والتوسعية الأمريكية سيُحدث أثراً مماثلاً. وقد كرّر مناهضو الإمبريالية والانعزاليون هذا التحذير مراراً، بدءاً من مارك توين ووصولاً إلى روبرت تافت وپاتريك بيوكانن، وازدادت حدّته مع ازدياد التدخل أثناء الحرب على الإرهاب، كما كتبه مؤلفون مثل تشالمرز جونسون، روبرت مري، ومايكل ڤلاهوس.[132]

ما يُميز بحث مادن هو تركيزه على السلام. فالنزاع الأهلي الجديد والمرير الذي اندلع في روما وأدى إلى سقوط الجمهورية كان نتاجاً ثانوياً للسلام، الذي يحمل في طياته، على نحوٍ مفارِق، انقسامات داخلية حادة. ظل الرومان جماعة متماسكة طالما استمر وجود أعداء خارجيين أقوياء، وطالما كان محور حياتهم الجماعي هو الدفاع عن مجتمعهم والحفاظ عليه.[133]

تم القضاء على الأعداء الخارجيين الأقوياء بحلول عام 146 ق.م. وفي عام 133 ق.م، اندلعت أعمال عنف على ربوة الكاپيتولين في روما. ولأول مرة، لم يخضع الشعب لسلطة مجلس الشيوخ. وربما لن يخضع لها بعد الآن. تم تجاهل القانون، وبدأ سفك الدماء. كان الرومان يقتلون بعضهم بعضاً.[134]

أكد كل من المؤرخين الكلاسيكيين[135] والمعاصرين على غياب التهديد الخارجي كعامل للحروب الأهلية في القرن الأول ق.م. والتي أعقبها سقوط الجمهورية. لكن يبدو أن مادن هو أول باحث يطبق هذه الأطروحة على الولايات المتحدة: "هل تنتظر أمريكا نفس المخاطر؟"[136] وكتب قبل هجوم الكاپيتول 2021، متأملاً:

كانت ربوة الكاپيتولين أعلى تلال روما السبع وأكثرها تبجيلاً. وبالطبع، تمتلك واشنطن ربوة كاپيتول أيضاً، سُميت تيمناً بالتلة الرومانية، وشهدت نصيبها من الصراعات السياسية. لكن ليس كهذا... لم تُراق دماء بعد على ربوة الكاپيتول الأمريكية، لكن السلام الأمريكي لا يزال في بداياته.[137]

عام 146 ق.م، أي قبل ثلاثة عشر عاماً من اندلاع أول أعمال العنف الأهلي، قضت روما على تهديدين خارجيين آخرين (من قرطاج واليونان). وخسرت الولايات المتحدة آخر تهديد خارجي خطير (السوڤيتي) عام 1991. وبافتراض أننا قد نكون ضمن التسلسل الروماني، حيث يقابل عام 146 ق.م. عام 1991 م، يتساءل مادن عما إذا كانت الولايات المتحدة قد بلغت مستوى السلام الذي حققته روما بحلول عام 146 ق.م.[138] كان تقديره إما نعم أو قريب جداً من ذلك،[139] لكن في كلتا الحالتين، ستظل التهديدات الخارجية ضئيلة للغاية بحيث لا يمكنها التأثير على الوحدة الوطنية التي كانت سائدة قبل عام 1991.[136]

وهكذا، من المرجح أن تكرر أمريكا مسار الرومان، وعلى الرغم من كتابته قبل عام 2020، إلا أنه يرى أن الأمريكيين، منذ عام 1991، مثل الرومان منذ عام 146 ق.م، يفقدون انسجامهم الداخلي. ويقول أنه في غياب التهديدات الخارجية، ليس من المستغرب أن نلحظ نفس الانكفاء على الذات في الولايات المتحدة أيضاً. فقد تراجعت الديناميكيات التي كانت تربط الأمريكيين ببعضهم البعض بشكل وثيق، لتحل محلها ديناميكيات أخرى تربطهم في مجموعات أصغر، مثل الولايات الجمهورية والولايات الديمقراطية.[140]

اشتدت المنافسات السياسية في ظل السلام الروماني، حتى أنها قوّضت بنية الجمهورية. تشير التجربة الرومانية إلى أن الجمهورية لا يمكنها الصمود أمام مثل هذه الاضطرابات. لكن لم تكن الإمبراطورية هي المعرضة للخطر، ولا السلام الروماني الذي أفرزته، فقد بقيا راسخين لقرون. بل كان النظام الجمهوري هو الذي سقط. وبالتالي، في أسوأ الأحوال، سيستمر السلام الأمريكي تحت الحكم الإمبراطوري.[136]

انظر أيضاً

- تحت السماء الأمريكية (أمريكان تيانشيا)

- الإمبريالية الأمريكية

- معاداة الشيوعية

- نظام بريتون وودز

- عقيدة بوش

- المحافظون الجدد

- النظام العالمي الجديد

- التدخلات الأمريكية وراء البحار

- السلام الأمريكي وعسكرة الفضاء

- السلام الروسي

- تعديل پلات

- عقيدة ريگان

- السلام الطويل الأمريكي الجنوبي

- خط زمني للعمليات العسكرية الأمريكية

- عقيدة ترومان

المصادر

- ^ Nye, Joseph S. (1990). "The Changing Nature of World Power". Political Science Quarterly. 105 (2): 177–192. doi:10.2307/2151022. JSTOR 2151022.

- ^ أ ب Kirchwey, George W. (1917). "Pax Americana". The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 72: 40–48. doi:10.1177/000271621707200109. S2CID 220723605.

- ^ Abbott, Lyman, Hamilton Wright Mabie, Ernest Hamlin Abbott, and Francis Rufus Bellamy. The Outlook. New York: Outlook Co, 1898. "Expansion not Imperialism" p. 465. (cf. [...] Felix Adler [states ...] "if, instead of establishing the Pax Americana so far as our influence avails throughout this continent, we should enter into' the field of Old World strife, and seek the sort of glory that is written in human blood." Here it is assumed that we have failed in establishing self-government, and propose to substitute, at least in other lands, an Old World form of government. This sort of argument has no effect on the expansionist, because he believes that we have magnificently succeeded in our problem, in spite of failures, neglects, and violations of our own principles, and because what he wishes to do is, not to abandon the experiment, but, inspired by the successes of the past, extend the Pax Americana over lands not included in this continent.")

- ^ "Definition of PAX AMERICANA". www.merriam-webster.com. Archived from the original on 2022-02-24. Retrieved 2018-08-01.

- ^ Charles L. Mee, The Marshall Plan: The launching of the pax americana (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1984)

- ^ "sagehistory.net". sagehistory.net. Archived from the original on June 29, 2009. Retrieved 2014-07-29.

- ^ أ ب "American Exceptionalism" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-02-25.

- ^ Lalor, John J., Cyclopaedia of Political Science, Political Economy, and of the Political History of the United States. Chicago: Rand, McNally, 1884. "The Union Archived 2017-03-30 at the Wayback Machine", p. 959.

- ^ "Help". Oxford English Dictionary. Archived from the original on 2020-04-07. Retrieved 2021-04-02.

- ^ Cromwell, James Henry Roberts (1941). Pax Americana: American Democracy and World Peace. (Chicago: Kroch), https://archive.org/details/paxamericanaamer00crom

- ^ MacNeil, Neil (1944). An American Peace. (New York: Scribner), pp. 160, 264, https://archive.org/details/americanpeace0000macn/page/160/mode/2up?view=theater

- ^ Peffer, Nathaniel (1943). "America's place in the post-war world". Political Science Quarterly. Vol. 58 (1): pp. 12, 14–15.

- ^ Ibañez Muñoz, Josep, "El desafío a la Pax americana: del 11 de septiembre a la guerra de Irak" in C. García and A. J. Rodrigo (eds) "El imperio inviable. El orden internacional tras el conflicto de Irak", Madrid: Tecnos, 2004.

- ^ "Rebuilding America's Defenses Strategy, Forces and Resources For a New Century" (PDF). Newamericancentury.org. Archived from the original on September 23, 2002. Retrieved July 29, 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ أ ب Wohlforth, William C. (1999). "The Stability of a Unipolar World". International Security. 24 (1): 5–41. doi:10.1162/016228899560031. JSTOR 2539346. S2CID 57568539. p. 39.

- ^ Labour's love-in with America is nothing new Archived أكتوبر 7, 2020 at the Wayback Machine Daily Telegraph September 6, 2002

- ^ Cited in Michio Kaku and David Axelrod, To Win a Nuclear War: The Pentagon Secret War Plans, Boston: South End Press, 1987, p. 64.

- ^ Clarke, Peter (2008). The Last Thousand Days of the British Empire: Churchill, Roosevelt, and the Birth of the Pax Americana. (New York: Bloomsbury Press). pp. 487-489, 500-504.

- ^ Futrell, Robert Frank, "Ideas, Concepts, Doctrine: Basic Thinking in the United States Air Force 1907–1960". DIANE Publishing, 1989. p. 239.

- ^ Cronin, Patrick P. From Globalism to Regionalism: New Perspectives on US Foreign and Defense Policies. [Washington, D.C.]: [National Defense Univ. Press], 1993. p. 213 Archived مارس 30, 2017 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Michael E. Eidenmuller (1963-06-10). "Commencement Address American University". Americanrhetoric.com. Archived from the original on 2021-05-02. Retrieved 2014-07-29.

- ^ Sargent, J. Daniel (2018). "Pax Americana: Sketches for an undiplomatic history," lecture at the 132nd Annual Meeting. (Washington DC: American Historical Society), pp. 4-5, https://escholarship.org/content/qt00t9n3s7/qt00t9n3s7_noSplash_637ebc3588bd11ebd8c2d0ec2c66890b.pdf?t=pbaa2e Archived مايو 25, 2025 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Chenoy, Anuradha M. (1992). "Soviet new thinking on national liberation movements: Continuity and change". In Kanet, Roger E; Miner, Deborah N; Resler, Tamara J (eds.). Soviet Foreign Policy in Transition. pp. 145–160. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511895449.009. ISBN 9780521413657. See especially pp. 149–50 of the internal definitions of neocolonialism in soviet bloc academia.

- ^ Rosemary Radford Ruether. Christianity and Social Systems: Historical Constructions and Ethical Challenges. Rowman & Littlefield, (2008) ISBN 0-7425-4643-8 p. 138: "Neocolonialism means that European powers and the United States no longer rule dependent territories directly through their occupying troops and imperial bureaucracy. Rather, they control the area's resources indirectly through business corporations and the financial lending institutions they dominate..."

- ^ Yumna Siddiqi. Anxieties of Empire and the Fiction of Intrigue. Columbia University Press, (2007) ISBN 0-231-13808-3 pp. 123–24 giving the classical definition limited to US and European colonial powers.

- ^ Thomas R. Shannon. An introduction to the world-system perspective. 2nd Ed. Westview Press, (1996) ISBN 0-8133-2452-1 pp. 94–95 classicially defined as a capitalist phenomenon.

- ^ William H. Blanchard. Neocolonialism American style, 1960–2000. Greenwood Publishing Group, (1996) ISBN 0-313-30013-5 pp. 3–12, definition p. 7.

- ^ Kaplan, Lawrence S. (1982). "Western Europe in "The American Century": A Retrospective View". Diplomatic History. 6 (2): 111–123. doi:10.1111/j.1467-7709.1982.tb00367.x. JSTOR 24911288. p. 115.

- ^ أ ب Peffer, Nathaniel (1943). "America's Place in the Post-War World". Political Science Quarterly. 58 (1): 11–24. doi:10.2307/2144425. JSTOR 2144425. pp. 12, 14–15.

- ^ To Win a Nuclear War, op. cit., p. 64.

- ^ Joshua Muravchick, "At Last, Pax Americana Archived 2018-07-16 at the Wayback Machine", The New York Times (January 24, 1991)

- ^ Wolfowitz, Paul (2000). "Remembering the Future". The National Interest (59): 35–45 [36]. JSTOR 42897259. Archived from the original on April 22, 2021. Retrieved October 3, 2020.

- ^ Wolfowitz, Paul (2000). "Remembering the Future". The National Interest. (59): p. 36.

- ^ Max Ostrovsky, (2018). Military Globalization: Geography, Strategy, Weaponry, (New York: Edwin Mellen Press), p. 247, https://archive.org/details/military-globalization/page/247/mode/2up?q=command&view=theater

- ^ Kaplan, Lawrence (1982). "Western Europe in 'The American Century,'" Diplomatic History, vol. 6 (2), p. 115.

- ^ Cohen, Eliot A. (2004), "History and the hyperpower," Foreign Affairs, vol 83 (4): p. 60.

- ^ Ferguson, Niall (2005). Colossus: The Rise and Fall of the American Empire. (New York: Penguin Books), p. 17.

- ^ ^Bischoff, Guenter (2009). "Empire discourses: The 'American Empire' in decline?" Kurswechsel, vol 2: p. 18.

- ^ Cranes, Lord (2012). Proconsuls: Delegated Political-Military Leadership from Rome to America Today. (New York: Cambridge University Press), p. 6.

- ^ Art, Robert J. (1998). "Geopolitics Updated: The Strategy of Selective Engagement". International Security. 23 (3): 79–113 [102]. doi:10.2307/2539339. JSTOR 2539339.

- ^ Zbigniew Brzezinski, The Grand Chessboard: American Primacy and Its Geostrategic Imperatives, (Perseus Books, New York, 1997, p. 23).

- ^ Westerfield, H. Bradford. The Instruments of America's Foreign Policy. New York: Crowell, 1963. p. 138. (cf. "the traditional American aversion to foreign wars, but also related to some recent disillusionment with the fruits of total wars ...")

- ^ "Rebuilding America's Defenses: Strategies, Forces, and Resources For a New Century" (PDF). September 2000. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 January 2009. Retrieved May 30, 2007.

- ^ Kupchan, Charles A. (1998). "After Pax Americana: Benign Power, Regional Integration, and the Sources of a Stable Multipolarity". International Security. 23 (2): 40–79. doi:10.1162/isec.23.2.40. JSTOR 2539379. S2CID 57569142.

- ^ Kupchan, Charles A. (1999). "Life after Pax Americana". World Policy Journal. 16 (3): 20–27. JSTOR 40209641.

- ^ Charles Kupchan, The End of the American Era: US Foreign Policy and Geopolitics of the Twenty-First Century, New York: Vintage Books, 2003.

- ^ Charles Kupchan, "Grand Strategy: The Four Pillars of the Future Archived 2022-02-24 at the Wayback Machine", Democracy Journal, 23, Winter 2012

- ^ Grinin, Leonid; Ilyin, Ilya V.; Andreev, Alexey I. 2016. "World Order in the Past, Present, and Future Archived 2017-12-01 at the Wayback Machine". In Social Evolution & History. Vol. 15, No. 1, pp. 58–84

- ^ "BREMMER: 'The Pax Americana, as of tomorrow, is over'" (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). Yahoo!. January 19, 2017. Archived from the original on April 16, 2022. Retrieved April 16, 2022.

- ^ Bremner, Ian (2016-11-21). "It really is the end of the world as we know it..." The Telegraph. Archived from the original on April 22, 2022. Retrieved April 16, 2022 – via Eurasia Group.

- ^ Cheng, Evelyn (January 3, 2017). "'Pax Americana' is over, and that could mean a much more turbulent world: Ian Bremmer" (in الإنجليزية). CNBC. Archived from the original on April 16, 2022. Retrieved April 16, 2022.

- ^ "The last days of Pax Americana". September 16, 2023. Archived from the original on August 30, 2024. Retrieved 2024-08-30.

- ^ Adler, Eric (2008). "Post-9/11 views of Rome and the nature of 'defensive imperialism.'" International Journal of the Classical Tradition, vol 15 (4): p. 589.

- ^ Hammond, Mason (1961). "Ancient Rome and modern America reconsidered." Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society, vol. 73: p. 5.

- ^ Hammond, Mason (1961). "Ancient Rome and modern America reconsidered." Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society, vol. 73: pp. 11, 15.

- ^ Hammond, Mason (1961). "Ancient Rome and modern America reconsidered." Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society, vol. 73: pp. 6-7.

- ^ Hammond, Mason (1961). "Ancient Rome and modern America reconsidered." Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society, vol. 73: pp. 7-8, 11, 15.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةauto1 - ^ Hitler, Adolf (September 3, 1939). The Complete Hitler Speeches and Proclamations 1932 1945. (tr. Domarus, Max, Bolchazy-Carducci Publishers, 1997), p. 1787, 1872, https://archive.org/details/the-complete-hitler-speeches-and-proclamations-1932-1945_202409/page/1787/mode/2up?view=theater

- ^ Hitler, Adolf (1942-45). Hitler and His Generals: Military Conferences, 1942-1945. (tr. Heiber, Helmut & Glantz, David. New York: Enigma Books, 2002), p. 92, https://archive.org/details/hitler-and-his-generals-1942-1945/page/92/mode/2up

- ^ Hitler, Adolf (1928). Secret Book. (ed. Taylor, Telford, tr. Attanasio, Salvator, New York: Grove Press, 1962), p. 107.

- ^ Crusade for Pan-Europe (New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1943), pp. 299–304.

- ^ Murray, Gilbert (1954). Hellenism and the Modern World. (Boston: Beacon Press), pp. 57–58, https://archive.org/details/hellenismmodernw00murr_0/page/58/mode/2up?view=theater

- ^ Bull, Hedley (1977). The Anarchical Society: A Study of Order in World Politics. (London: Macmillan), p. 201.

- ^ Liska, George (1967). Imperial American: The International Politics of Primacy. (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press), pp. 9–10, 23.

- ^ (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press), p. xii, https://archive.org/details/grandstrategyofr0000lutt/page/n13/mode/2up?view=theater

- ^ أ ب Elliot, Justin (4 April 2008). "Don't know much about history: The Pentagon looks back to four great empires for tip on how to rule the world," Global Policy Forum, https://archive.globalpolicy.org/component/content/article/155-history/26017.html Archived أبريل 6, 2021 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Herman, Mark et al (2002). "Military advantage in history," Information Assurance Technology Analysis Center. (Washington, D.C.: Department of Defense), chapter 6, pp. 81–82, https://www.motherjones.com/wp-content/uploads/legacy/news/featurex/2008/07/military-advantage-in-history.pdf

- ^ Lord, Cranes (2012). Proconsuls: Delegated Political–Military Leadership from Rome to America Today. (New York: Cambridge University Press), pp. 2, 6.

- ^ Eckstein, Arthur M. (2008). Rome Enters the Greek East: From Anarchy to Hierarchy in the Hellenistic Mediterranean, 230–170 B.C. (Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell), p. 343.

- ^ Eckstein, Arthur M. (2008). Rome Enters the Greek East: From Anarchy to Hierarchy in the Hellenistic Mediterranean, 230–170 B.C. (Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell), pp. 312–315.

- ^ Eckstein, Arthur M. (2008). Rome Enters the Greek East: From Anarchy to Hierarchy in the Hellenistic Mediterranean, 230–170 B.C. (Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell), pp. 340-342.

- ^ Eckstein, Arthur M. (2008). Rome Enters the Greek East: From Anarchy to Hierarchy in the Hellenistic Mediterranean, 230–170 B.C. (Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell), p. 344.

- ^ Burton, Paul J. (2019). Roman Imperialism. (Leiden & Boston: Brill), p. 33.

- ^ Eckstein, Arthur M. (2008). Rome Enters the Greek East: From Anarchy to Hierarchy in the Hellenistic Mediterranean, 230–170 B.C. (Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell), pp. 336, 343.

- ^ Nye, Joseph (March 21, 2002). "The new Rome meets the new barbarians". The Economist. ISSN 0013-0613. Archived from the original on September 15, 2019.

- ^ The Paradox of American Power, (Oxford University Press, New York, 2002).

- ^ Bound To Lead: The Changing Nature Of American Power (Basic Books, 1991).

- ^ "The Future of American Power: Dominance and Decline in Perspective Archived ديسمبر 20, 2016 at the Wayback Machine", Foreign Affairs (November–December 2010).

- ^ Ferguson, Niall (2005). Colossus: The Rise and Fall of the American Empire (New York: Penguin Books, 2005), p. 14.

- ^ Madden, Thomas F. (2008). Empires of Trust: How Rome Built – and America Is Building – a New World. (Dutton Adult), p. 9.

- ^ "Rome, AD ... Rome, DC Archived 2016-10-22 at the Wayback Machine", The Guardian (September 18, 2002)

- ^ Ronald Dworkin, "The Threat to Patriotism Archived 2016-12-24 at the Wayback Machine", The New York Review of Books (February 28, 2002)

- ^ Cited in Burton, Paul J. (2013). "Pax Romana/Pax Americana: Views of the "New Rome" from "Old Europe", 2000–2010". International Journal of the Classical Tradition. 20 (1–2): 15–40. doi:10.1007/s12138-013-0320-0. S2CID 162321437.

- ^ Jonathan Freedland, "Rome, AD ... Rome, DC Archived 2016-10-22 at the Wayback Machine", The Guardian (September 18, 2002)

- ^ Julian Go, Patterns of Empire: The British and American Empires, 1688 to the Present (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2011), p. 2.

- ^ Smil, Vaclav (2010). Why America is Not a New Rome. Massachusetts: The MIT Press. pp. xi–xii. ISBN 9780262288293.

- ^ Vasunia, Phiroze (2011). "The comparative study of empires." Journal of Roman Studies. Vol. 101: p. 232.

- ^ Burton, Paul J. (2013). "Pax Romana/Pax Americana: Views of the "New Rome" from "Old Europe", 2000–2010". International Journal of the Classical Tradition. 20 (1–2): 15–40. doi:10.1007/s12138-013-0320-0. S2CID 162321437.

- ^ Adler, Eric (2008). "Post-9/11 views of Rome and the nature of 'defensive imperialism.'" International Journal of the Classical Tradition, vol 15 (4): pp. 599, 602–05.

- ^ أ ب Hanson, Victor Davis (November 2002). "A Funny Sort of Empire". National Review. Archived from the original on 2008-05-11. Retrieved October 8, 2009.

- ^ Cited in Geir Lundestad, The United States and Western Europe since 1945: From 'Empire' by Invitation to Transatlantic Drift, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005), p 112.

- ^ Schlesinger, Arthur Meier. The Cycles of American History, (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1986), p 141. OCLC 13455179

- ^ Lawrence Kaplan, "Western Europe in 'The American Century'", Diplomatic History, 6/2, (1982): p 115.

- ^ Cohen, Eliot A. (2004). "History and the Hyperpower". Foreign Affairs. 83 (4): 49–63. doi:10.2307/20034046. JSTOR 20034046. pp. 60-61

- ^ Reveron, Derek S. (2007). America's Viceroys: The Military and US Foreign Policy. (Palgrave Macmillan), p 4.

- ^ Wrage, Stephen D. (2007). "US Combatant Commander: The man in the middle," America's Viceroys: The Military and US Foreign Policy. (Ed. Reveron, Derek S. Palgrave Macmillan), p 193.

- ^ Bacevich, Andrew J. (2002). American Empire: The Realities and Consequences of US Diplomacy. (Harvard university Press), chapter 7, p 167.

- ^ Cited in Andrew Feickert, "The Unified Command Plan and Combatant Commands: Background and Issues for Congress", (Congressional Research Service, Washington: White House, 2013), p 59.

- ^ Reveron, Derek S. (2007). America's Viceroys: The Military and US Foreign Policy. (Palgrave Macmillan), p 2.

- ^ Wrage, Stephen D. (2007). "US Combatant Commander: The man in the middle." America's Viceroys: The Military and US Foreign Policy. (Ed. Reveron, Derek S. Palgrave Macmillan), p 185.

- ^ Wrage, Stephen D. (2007). "US Combatant Commander: The man in the middle." America's Viceroys: The Military and US Foreign Policy. (Ed. Reveron, Derek S. Palgrave Macmillan), p 185.

- ^ Duncan, Mike (2017). The Storm Before the Storm: The Beginning of the End of the Roman Republic. (Public Affairs), p XXIII.

- ^ Madden, Thomas F. (2008). Empires of Trust: How Rome Built—and America Is Building—a New World. (Dutton Adult), p 201, 210, 250.

- ^ Fears, Rufus Jesse (19 December 2005). "The lessons of the Roman Empire for America today." Heritage Foundation, p. 8.

- ^ أ ب Lord, Cranes (2012). Proconsuls: Delegated Political-Military Leadership from Rome to America Today. (New York: Cambridge University Press), p 2, 6, 167.

- ^ Niall Ferguson, Colossus: The Rise and Fall of the American Empire, (New York: Penguin Books, 2005), p 17.

- ^ Günter Bischof, "Empire Discourses: The 'American Empire' in Decline? Archived أبريل 30, 2025 at the Wayback Machine" Kurswechsel, 2, (2009): p 18

- ^ Freedland, Jonathan (June 14, 2007). "Bush's Amazing Achievement". The New York Review of Books (in الإنجليزية). ISSN 0028-7504. Archived from the original on 2015-12-10.

- ^ Cited in Packard, George R. (2010). "The United States–Japan Security Treaty at 50: Still a Grand Bargain?". Foreign Affairs. 89 (2): 92–103. JSTOR 20699853. pp. 98–99

- ^ Sung Woo Kim, "System Polarities and Alliance Politics", (PhD thesis, University of Iowa, 2012), pp. 149–151

- ^ Swapna Venugopal Ramaswamy, (2025). "Trump says NATO countries are 'taking advantage' and should contribute 5% of GDP." USA Today, https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/politics/elections/2025/01/07/nato-5-percent-gdp-defense-trump/77514412007/

- ^ أ ب Adler, Eric (2008). "Post-9/11 Views of Rome and the Nature of "Defensive Imperialism"" (PDF). International Journal of the Classical Tradition. 15 (4): 587–610. doi:10.1007/s12138-009-0069-7. JSTOR 25691268. S2CID 143223136. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-01-21. Quoting p. 593.

- ^ Sands, Perry Cooper (1975). The Client Princes unde the Republic. (New York: Amo Press), pp. 127–28, 152–55.

- ^ North, John A. (1981). "The development of Roman imperialism," Journal of Roman Studies, vol. 71: p. 2.

- ^ Lintott, Andrew (1993). Imperium Romanum. (London: Routeledge), p. 35.

- ^ Ostrovsky, Max (2006). The Hyperbola of the World Order. (Lanham: University Press of America), p. 225.

- ^ Toynbee, Arnold (1962). America and the World Revolution. (New York: Oxford University Press), pp. 105–06, https://archive.org/details/americaworldrevo0000toyn/page/104/mode/2up?view=theater&q=annexation

- ^ Steel, Ronald (1967). Pax Americana. (New York: Viking Press), p. 17, https://archive.org/details/paxamericana0000stee/page/16/mode/2up?view=theater

- ^ Bender, Peter (2003). "America: The New Roman Empire?". Orbis. 47: 152. doi:10.1016/S0030-4387(02)00180-1.

- ^ "America: The New Roman Empire", p. 145.

- ^ "America: The New Roman Empire", pp. 146–47.

- ^ "America: The New Roman Empire", pp. 148, 151.

- ^ "America: The New Roman Empire", p. 145.

- ^ "America: The New Roman Empire", p. 155.

- ^ The Choice: Global Domination or Global Leadership (New York: Basic Books, 2004), p. 216.

- ^ Freedland, Jonathan (18 September 2002). "Rome, AD ... Rome, DC?" The Guardian, https://mg.co.za/article/2002-11-15-rome-ad-rome-dc/

- ^ Merry, Robert W. (2005). Sands of Empire: Missionary Zeal, American Foreign Policy, and the Hazards of Global Ambition. (New York: Simon & Schuster), pp. 217–31.

- ^ Fisk, Robert (4 December 2006). "Echoes of the Roman Empire." ZNet Articles, https://znetwork.org/znetarticle/echoes-of-the-roman-empire-by-robert-fisk/

- ^ Ostrovsky, Max (2007). The Hyperbola of the World Order. (Lanham: University Press of America), p. 223.

- ^ Madden, Thomas F. (2008). Empires of Trust: How Rome Built – and America Is Building – a New World. (Dutton Adult).

- ^ Adler, Eric (2008). "Post-9/11 views of Rome and the nature of 'defensive imperialism.'" International Journal of the Classical Tradition, vol 15 (4): p. 602.

- ^ Madden, Thomas F. (2008). Empires of Trust: How Rome Built – and America Is Building – a New World. (Dutton Adult), pp. 234, 237, 239.

- ^ Madden, Thomas F. (2008). Empires of Trust: How Rome Built – and America Is Building – a New World. (Dutton Adult), pp. 230, 233–34, 238–39.

- ^ Madden, Thomas F. (2008). Empires of Trust: How Rome Built – and America Is Building – a New World. (Dutton Adult), pp. 239–45.

- ^ أ ب ت Madden, Thomas F. (2008). Empires of Trust: How Rome Built – and America Is Building – a New World. (Dutton Adult), p. 250.

- ^ Madden, Thomas F. (2008). Empires of Trust: How Rome Built – and America Is Building – a New World. (Dutton Adult), pp. 230, 234.

- ^ Madden, Thomas F. (2008). Empires of Trust: How Rome Built – and America Is Building – a New World. (Dutton Adult), p. 201.

- ^ Madden, Thomas F. (2008). Empires of Trust: How Rome Built – and America Is Building – a New World. (Dutton Adult), p. 210.

- ^ Madden, Thomas F. (2008). Empires of Trust: How Rome Built – and America Is Building – a New World. (Dutton Adult), pp. 238, 250.

قراءات إضافية

- Ankerl, Guy (2000). "Global communication without universal civilization". Coexisting Contemporary Civilizations: Arabo-Muslim, Bharati, Chinese and Western. INU Societal Research. Vol. 1. Geneva: INU Press. pp. 256–332. ISBN 978-2-88155-004-1.

- Brown, Michael E. (2000). America's Strategic Choices. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. ISBN 9780262265249.

- Burton, Paul J. (2013). "Pax Romana/Pax Americana: Views of the "New Rome" from "Old Europe", 2000–2010". International Journal of the Classical Tradition. 20 (1–2): 15–40. doi:10.1007/s12138-013-0320-0. S2CID 162321437.

- Clarke, Peter. The last thousand days of the British empire: Churchill, Roosevelt, and the birth of the Pax Americana (Bloomsbury Publishing, 2010)

- Gottlieb, Gidon (1993). Nation against State: A New Approach to Ethnic Conflicts and the Decline of Sovereignty. New York: Council on Foreign Relations Press. ISBN 9780876091562.

- Hull, William I. (1915). The Monroe Doctrine: National or International. New York: G.P. Putnam.

- Kahrstedt, Ulrich (1920). Pax Americana; ein historische Betrachtung am Wendepunkte der europäischen Geschichte [Pax Americana, a historical look at the turning points in European history] (in الألمانية). Munich: Drei Masken Verlag.

- Kiernan, V. G. (2005). America, the New Imperialism: From White Settlement to World Hegemony. London: Verso. ISBN 9781844675227.

- Kupchan, Charles (2002). The End of the American Era: U.S. Foreign Policy and the Geopolitics of the 21st-century. New York: A. Knopf.

- Layne, Christopher (2012). "This Time It's Real: The End of Unipolarity and the Pax Americana". International Studies Quarterly. 56 (1): 203–213. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2478.2011.00704.x. JSTOR 41409832.

- LaFeber, Walter (1998). The New Empire: An Interpretation of American Expansion, 1860–1898. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0801485954.

- Lears, Jackson, "The Forgotten Crime of War Itself" (review of Samuel Moyn, Humane: How the United States Abandoned Peace and Reinvented War, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2021, 400 pp.), The New York Review of Books, vol. LXIX, no. 7 (21 April 2022), pp. 40–42. "After September 11 [2001] no politician asked whether the proper response to a terrorist attack should be a US war or an international police action. [...] Debating torture or other abuses, while indisputably valuable, has diverted Americans from 'deliberating on the deeper choice they were making to ignore constraints on starting war in the first place.' [W]ar itself causes far more suffering than violations of its rules." (p. 40.)

- Louis, William Roger (2006). "The Pax Americana: Sir Keith Hancock, The British Empire, and American Expansion". Ends of British Imperialism: The Scramble for Empire, Suez and Decolonization: Collected Essays. London: I.B. Tauris. pp. 999+. ISBN 9781845113476.

- Mee, Charles L. The Marshall Plan: The launching of the pax americana (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1984)

- Narlikar, Amrita; Kumar, Rajiv (2012). "From Pax Americana to Pax Mosaica? Bargaining over a New Economic Order". The Political Quarterly. 83 (2): 384–394. doi:10.1111/j.1467-923X.2012.02294.x.

- Nye, Joseph S. (1990). Bound to Lead: The Changing Nature of American Power. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 9780465007448.

- Snow, Francis Haffkine (1921). "American as a World Tyrant: A German Historian's Attempt to Prove That Europe is Becoming a Serf of the United States". Current History. 13.

وصلات خارجية

- The end of the Pax Americana? by Michael Lind

- Why America Thinks it Has to Run the World by Benjamin Schwarz

- It’s Over, Over There: The Coming Crack-up in Transatlantic Relations by Christopher Layne

- War in the Contest for a New World Order by Peter Gowan

- So it must be for ever by Thomas Meaney

- Instrumental Internationalism: The American Origins of the United Nations, 1940–3 by Stephen Wertheim

- What are we there for? by Tom Stevenson

- Peter Gowan interview on U.S. foreign policy since 1945, Interview with Against the Grain

- CS1 maint: unfit URL

- CS1 الإنجليزية الأمريكية-language sources (en-us)

- Articles containing إنگليزية-language text

- Pages using Lang-xx templates

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- CS1 الألمانية-language sources (de)

- مصطلحات تاريخية

- فترات تاريخ الولايات المتحدة

- كلمات وعبارات سياسية لاتينية

- فترات سلام

- أمن دولي

- استثنائية أمريكية