حرب الاستقلال الموزمبيقية

| حرب الاستقلال الموزمبيقية | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| جزء من الحرب الاستعمارية البرتغالية، وتصفية الاستعمار في أفريقيا، و الحرب الباردة | |||||||

Mozambique within modern-day Africa. | |||||||

| |||||||

| المتحاربون | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| القادة والزعماء | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| القوى | |||||||

| 10,000–15,000[32][33] | 50,000 (17 May 1970)[34] | ||||||

| الضحايا والخسائر | |||||||

| 10,000 killed[35] | 3,500 killed[35] | ||||||

|

Civilian casualties: 50,000 killed[35] | |||||||

قالب:Campaignbox Mozambican War of Independence قالب:Campaignbox Portuguese Colonial War

The Mozambican War of Independence was an armed conflict between the guerrilla forces of the Mozambique Liberation Front or FRELIMO (Frente de Libertação de Moçambique), and Portugal. The war officially started on September 25, 1964, and ended with a ceasefire on September 8, 1974, resulting in a negotiated independence in 1975.

Portugal's wars against independence guerrilla fighters in its 400-year-old African territories began in 1961 with Angola. In Mozambique, the conflict erupted in 1964 as a result of unrest and frustration amongst many indigenous Mozambican populations, who perceived foreign rule to be a form of exploitation and mistreatment, which served only to further Portuguese economic interests in the region. Many Mozambicans also resented Portugal's policies towards indigenous people, which resulted in discrimination, traditional lifestyle turning difficult for many Africans, and limited access to Portuguese-style education and skilled employment.

As successful self-determination movements spread throughout Africa after World War II, many Mozambicans became progressively nationalistic in outlook, and increasingly frustrated by the nation's continued subservience to foreign rule. For the other side, many enculturated indigenous Africans who were fully integrated into the Portugal-ruled social organization of Portuguese Mozambique, in particular those from the urban centres, reacted to the independentist claims with a mixture of discomfort and suspicion. The ethnic Portuguese of the territory, which included most of the ruling authorities, responded with increased military presence and fast-paced development projects.

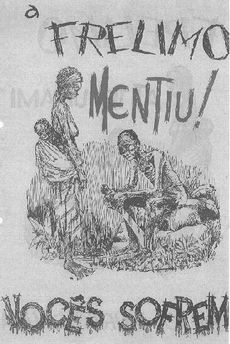

A mass exile of Mozambique's political intelligentsia to neighbouring countries provided havens from which radical Mozambicans could plan actions and foment political unrest in their homeland. The formation of the Mozambican guerrilla organisation FRELIMO and the support of the Soviet Union, China, Cuba, Yugoslavia, Bulgaria, Tanzania, Zambia, Egypt, Algeria and Gaddafi regime in Libya through arms and advisers, led to the outbreak of violence that was to last over a decade.

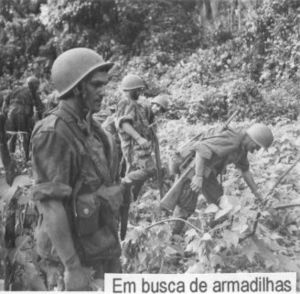

From a military standpoint, the Portuguese regular army held the upper hand during the conflict against the independentist guerrilla forces. Nonetheless, Mozambique succeeded in achieving independence on June 25, 1975, after a civil resistance movement known as the Carnation Revolution backed by portions of the military in Portugal overthrow the military dictatorship sponsored by US, thus ending 470 years of Portuguese colonial rule in the East African region. According to historians of the Revolution, the military coup in Portugal was in part fuelled by protests concerning the conduct of Portuguese troops in their treatment of some local Mozambican populace.[36][37] The role of the growing communist influence over the group of Portuguese military insurgents who led the Lisbon's military coup, and, on the other hand, the pressure of the international community over the direction of the Portuguese Colonial War in general, were main causes for the final outcome.[38]

Background

Portuguese colonial rule

San hunter and gatherers, ancestors of the Khoisani peoples, were the first known inhabitants of the region that is now Mozambique, followed in the 1st and 4th centuries by Bantu-speaking peoples who migrated there across the Zambezi River. In 1498, Portuguese explorers landed on the Mozambican coastline.[39] Portugal's influence in East Africa grew throughout the 16th century; she established several colonies known collectively as Portuguese East Africa. Slavery and gold became profitable for the Europeans; influence was largely exercised through individual settlers and there was no centralised administration[40] and, in the meantime, Portugal had turned her attention to India and Brazil.

Rise of FRELIMO

Portugal designated Mozambique an overseas territory in 1951 in order to show to the world that the colony had a greater autonomy. It was called the Overseas Province of Mozambique (Província Ultramarina de Moçambique). Nonetheless, Portugal still maintained strong control over its overseas province. The increasing number of newly independent African nations after World War II,[32] coupled with the ongoing mistreatment of the indigenous population, encouraged the growth of nationalist sentiments within Mozambique.[39]

Conflict

Insurgency under Mondlane (1964–69)

Portuguese development program

Assassination of Eduardo Mondlane

Main Article: Assassination of Eduardo Mondlane

On the 3rd February, 1969, Eduardo Mondlane was killed by explosives smuggled into his locale. Many sources state that, in an attempt to rectify the situation in Mozambique, the Portuguese secret police assassinated Mondlane by sending a parcel to his office in Dar es Salaam. Inside the parcel was a book containing an explosive device, which detonated upon opening. Other sources state that Eduardo was killed when an explosive device detonated underneath his chair at the FRELIMO headquarters, and that the faction responsible was never identified.[41]

Continuing war (1969–74)

Political instability and ceasefire (1974–75)

See also

Notes

- ^ Frontiersmen: Warfare In Africa Since 1950, 2002. Page 49.

- ^ China Into Africa: Trade, Aid, and Influence, 2009. Page 156.

- ^ Fidel Castro: My Life: A Spoken Autobiography, 2008. Page 315

- ^ The Cuban Military Under Castro, 1989. Page 45

- ^ Translations on Sub-Saharan Africa 607-623, 1967. Page 65.

- ^ Underdevelopment and the Transition to Socialism: Mozambique and Tanzania, 2013. Page 38.

- ^ Southern Africa The Escalation of a Conflict : a Politico-military Study, 1976. Page 99.

- ^ Tito in the world press on the occasion of the 80th birthday, 1973. Page 33.

- ^ Mozambique, Resistance and Freedom: A Case for Reassessment, 1994. Page 64.

- ^ Liberalism, Black Power, and the Making of American Politics, 1965–1980. 2009. Page 83

- ^ United Front against imperialism: China's foreign policy in Africa, 1986. Page 174

- ^ Portuguese Africa: a handbook, 1969. Page 423.

- ^ Frelimo candidate Filipe Nyusi leading Mozambique presidential election

- ^ Mozambique in the twentieth century: from colonialism to independence, 1979. Page 271

- ^ A History of FRELIMO, 1982. Page 13

- ^ Encyclopedia Americana: Sumatra to Trampoline, 2005. Page 275

- ^ Nyerere and Africa: End of an Era, 2007. Page 226

- ^ Culture And Customs of Mozambique, 2007. Page 16

- ^ Intercontinental Press, 1974. Page 857.

- ^ The Last Bunker: A Report on White South Africa Today, 1976. Page 122

- ^ Vectors of Foreign Policy of the Mozambique Front (1962-1975): A Contribution to the Study of the Foreign Policy of the People's Republic of Mozambique, 1988. Page 8

- ^ Africa's Armies: From Honor to Infamy, 2009. Page 76

- ^ Imagery and Ideology in U.S. Policy Toward Libya 1969–1982, 1988. Page 70

- ^ Qaddafi: his ideology in theory and practice, 1986. Page 140.

- ^ South Africa in Africa: A Study in Ideology and Foreign Policy, 1975. Page 173.

- ^ The dictionary of contemporary politics of Southern Africa, 1988. Page 250.

- ^ Terror on the Tracks: A Rhodesian Story, 2011. Page 5.

- ^ Chirambo, Reuben (2004). "'Operation Bwezani': The Army, Political Change, and Dr. Banda's Hegemony in Malawi" (PDF). Nordic Journal of African Studies. 13 (2): 146–163. Retrieved 12 May 2011.

- ^ Salazar: A Political Biography, 2009. Page 530.

- ^ Prominent African Leaders Since Independence, 2012. Page 383.

- ^ أ ب ت Beit-Hallahmi, Benjamin. The Israeli connection: Whom Israel arms and why, pp. 64. IB Tauris, 1987.

- ^ أ ب Westfall, William C., Jr., Major, United States Marine Corps, Mozambique-Insurgency Against Portugal, 1963–1975, 1984. Retrieved on March 10, 2007

- ^ Walter C. Opello, Jr. Issue: A Journal of Opinion, Vol. 4, No. 2, 1974, p. 29

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةLeonard38 - ^ أ ب ت Mid-Range Wars and Atrocities of the Twentieth Century retrieved December 4, 2007

- ^ George Wright, The Destruction of a Nation, 1996

- ^ Phil Mailer, Portugal – The Impossible Revolution?, 1977

- ^ Stewart Lloyd-Jones, ISCTE (Lisbon), Portugal's history since 1974, "The Portuguese Communist Party (PCP–Partido Comunista Português), which had courted and infiltrated the MFA from the very first days of the revolution, decided that the time was now right for it to seize the initiative. Much of the radical fervour that was unleashed following Spínola's coup attempt was encouraged by the PCP as part of their own agenda to infiltrate the MFA and steer the revolution in their direction.", Centro de Documentação 25 de Abril, University of Coimbra

- ^ أ ب Kennedy, Thomas. Mozambique, The Catholic Encyclopaedia. Retrieved on March 10, 2007

- ^ T. H. Henriksen, Remarks on Mozambique, 1975, p. 11

- ^ Eduardo Chivambo Mondlane Biography Archived سبتمبر 12, 2006 at the Wayback Machine, Oberlin College, revised September 2005 by Melissa Gottwald. Retrieved on February 16, 2000

المراجع

Printed sources

- Bowen, Merle. The State Against the Peasantry: Rural Struggles in Colonial and Postcolonial Mozambique. University Press Of Virginia; Charlottesville, Virginia, 2000

- Calvert, Michael Brig. Counter-Insurgency in Mozambique from the Journal of the Royal United Services Institute, no. 118, March 1973

- Cann, John P. Counterinsurgency in Africa: The Portuguese Way of War, 1961–1974, Hailer Publishing, 2005, ISBN 0-313-30189-1

- Grundy, Kenneth W. Guerrilla Struggle in Africa: An Analysis and Preview, New York: Grossman Publishers, 1971, ISBN 0-670-35649-2

- Henriksen, Thomas H. Remarks on Mozambique, 1975

- Legvold, Robert. Soviet Policy in West Africa, Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1970, ISBN 0-674-82775-9

- Mailer, Phil. Portugal – The Impossible Revolution? 1977, ISBN 0-900688-24-6

- Munslow, Barry (ed.). Samora Machel, An African Revolutionary: Selected Speeches and Writings, London: Zed Books, 1985.

- Newitt, Malyn. A History of Mozambique, 1995, ISBN 0-253-34007-1

- Penvenne, J. M. "Joao Dos Santos Albasini (1876-1922): The Contradictions of Politics and Identity in Colonial Mozambique", Journal of African History, number 37.

- Wright, George. The Destruction of a Nation, 1996, ISBN 0-7453-1029-X

Online sources

- Belfiglio, Valentine J. (July–August 1983)The Soviet Offensive in Southern Africa, Air University Review. Retrieved on March 10, 2007

- Cooper, Tom. Central, Eastern and South African Database, Mozambique 1962–1992, ACIG, September 2, 2003. Retrieved on March 7, 2007

- Eduardo Chivambo Mondlane (1920–1969), Oberlin College, revised in September 2005 by Melissa Gottwald. Retrieved on February 16, 2007

- Frelimo, Britannica.com. Retrieved on October 12, 2006

- Kennedy, Thomas (1911). "Mozambique". The Catholic Encyclopaedia. Vol. 10. New York: Robert Appleton Company. Retrieved on March 10, 2007

- Newitt, Malyn. Mozambique (Archived 2009-11-01), Encarta. Retrieved on February 16, 2007

- Thom, William G. (July–August 1974). Trends in Soviet Support for African Liberation, Air University Review. Retrieved on March 10, 2007

- Westfall, William C., Jr. (April 1, 1984). Mozambique-Insurgency Against Portugal, 1963–1975. Retrieved on February 15, 2007

- Wright, Robin (May 12, 1975). Mondlane, Janet of the Mozambique Institute: American "Godmother" to an African Revolution. Retrieved on March 10, 2007

وصلات خارجية

- Articles with unsourced statements from June 2017

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Pages with empty portal template

- Pages using country topics with unknown parameters

- Mozambican War of Independence

- Communism in Mozambique

- Separatism in Mozambique

- Separatism in Portugal

- Military history of Mozambique

- حروب الپرتغال

- Wars involving Libya

- Wars involving the states and peoples of Africa

- Portuguese Colonial War