حركة (فيزياء)

علم الحركة مهم فهمه، إذ بدونه لما وصل العلماء إلى اختراع السيارات والطائرات والمركبات الفضائية والوصول إلى القمر وغيره من الكواكب. Motion is mathematically described in terms of displacement, distance, velocity, acceleration, speed, and frame of reference to an observer, measuring the change in position of the body relative to that frame with a change in time. The branch of physics describing the motion of objects without reference to their cause is called kinematics, while the branch studying forces and their effect on motion is called dynamics.

If an object is not in motion relative to a given frame of reference, it is said to be at rest, motionless, immobile, stationary, or to have a constant or time-invariant position with reference to its surroundings. Modern physics holds that, as there is no absolute frame of reference, Newton's concept of absolute motion cannot be determined.[1] Everything in the universe can be considered to be in motion.[2]

Motion applies to various physical systems: objects, bodies, matter particles, matter fields, radiation, radiation fields, radiation particles, curvature, and space-time. One can also speak of the motion of images, shapes, and boundaries. In general, the term motion signifies a continuous change in the position or configuration of a physical system in space. For example, one can talk about the motion of a wave or the motion of a quantum particle, where the configuration consists of the probabilities of the wave or particle occupying specific positions.

معادلات الحركة

| جزء من سلسلة عن |

| الميكانيكا الكلاسيكية |

|---|

قوانين الحركة

In physics, the motion of [1] bodies is described through two related sets of laws of mechanics. Classical mechanics for super atomic (larger than an atom) objects (such as cars, projectiles, planets, cells, and humans) and quantum mechanics for atomic and sub-atomic objects (such as helium, protons, and electrons). Historically, Newton and Euler formulated three laws of classical mechanics:

| القانون الأول: | In an inertial reference frame, an object either remains at rest or continues to move in a straight line at a constant velocity, unless acted upon by a net force. |

| القانون الثاني: | In an inertial reference frame, the vector sum of the forces F on an object is equal to the mass m of that object multiplied by the acceleration a of the object: .

If the resultant force acting on a body or an object is not equal to zero, the body will have an acceleration which is in the same direction as the resultant force. |

| القانون الثالث: | When one body exerts a force on a second body, the second body simultaneously exerts a force equal in magnitude and opposite in direction onto the first body. |

الميكانيكا الكلاسيكية

Classical mechanics is used for describing the motion of macroscopic objects moving at speeds significantly slower than the speed of light, from projectiles to parts of machinery, as well as astronomical objects, such as spacecraft, planets, stars, and galaxies. It produces very accurate results within these domains and is one of the oldest and largest scientific descriptions in science, engineering, and technology.

Classical mechanics is fundamentally based on Newton's laws of motion. These laws describe the relationship between the forces acting on a body and the motion of that body. They were first compiled by Sir Isaac Newton in his work Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica, which was first published on July 5, 1687. Newton's three laws are:

- A body at rest will remain at rest, and a body in motion will remain in motion unless it is acted upon by an external force. (This is known as the law of inertia.)

- Force () is equal to the change in momentum per change in time (). For a constant mass, force equals mass times acceleration ( ).

- For every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction. (In other words, whenever one body exerts a force onto a second body, (in some cases, which is standing still) the second body exerts the force back onto the first body. and are equal in magnitude and opposite in direction. So, the body which exerts will be pushed backward.)[5]

Newton's three laws of motion were the first to accurately provide a mathematical model for understanding orbiting bodies in outer space. This explanation unified the motion of celestial bodies and the motion of objects on Earth.

الميكانيكا النسبية

Modern kinematics developed with study of electromagnetism and refers all velocities to their ratio to speed of light . Velocity is then interpreted as rapidity, the hyperbolic angle for which the hyperbolic tangent function . Acceleration, the change of velocity over time, then changes rapidity according to Lorentz transformations. This part of mechanics is special relativity. Efforts to incorporate gravity into relativistic mechanics were made by W. K. Clifford and Albert Einstein. The development used differential geometry to describe a curved universe with gravity; the study is called general relativity.

Quantum mechanics

Quantum mechanics is a set of principles describing physical reality at the atomic level of matter (molecules and atoms) and the subatomic particles (electrons, protons, neutrons, and even smaller elementary particles such as quarks). These descriptions include the simultaneous wave-like and particle-like behavior of both matter and radiation energy as described in the wave–particle duality.[6]

In classical mechanics, accurate measurements and predictions of the state of objects can be calculated, such as location and velocity. In quantum mechanics, due to the Heisenberg uncertainty principle, the complete state of a subatomic particle, such as its location and velocity, cannot be simultaneously determined.[7]

In addition to describing the motion of atomic level phenomena, quantum mechanics is useful in understanding some large-scale phenomena such as superfluidity, superconductivity, and biological systems, including the function of smell receptors and the structures of protein.[8]

Orders of magnitude

Humans, like all known things in the universe, are in constant motion;[2] however, aside from obvious movements of the various external body parts and locomotion, humans are in motion in a variety of ways which are more difficult to perceive. Many of these "imperceptible motions" are only perceivable with the help of special tools and careful observation. The larger scales of imperceptible motions are difficult for humans to perceive for two reasons: Newton's laws of motion (particularly the third) which prevents the feeling of motion on a mass to which the observer is connected, and the lack of an obvious frame of reference which would allow individuals to easily see that they are moving.[9] The smaller scales of these motions are too small to be detected conventionally with human senses.

الكون

Spacetime (the fabric of the universe) is expanding, meaning everything in the universe is stretching, like a rubber band. This motion is the most obscure as it is not physical motion, but rather a change in the very nature of the universe. The primary source of verification of this expansion was provided by Edwin Hubble who demonstrated that all galaxies and distant astronomical objects were moving away from Earth, known as Hubble's law, predicted by a universal expansion.[10]

المجرة

The Milky Way Galaxy is moving through space and many astronomers believe the velocity of this motion to be approximately 600 kilometres per second (1،340،000 mph) relative to the observed locations of other nearby galaxies. Another reference frame is provided by the Cosmic microwave background. This frame of reference indicates that the Milky Way is moving at around 582 kilometres per second (1،300،000 mph).[11][المصدر لا يؤكد ذلك]

الشمس والمجموعة الشمسية

The Milky Way is rotating around its dense Galactic Center, thus the Sun is moving in a circle within the galaxy's gravity. Away from the central bulge, or outer rim, the typical stellar velocity is between 210 و 240 kilometres per second (470،000 و 540،000 mph).[12] All planets and their moons move with the Sun. Thus, the Solar System is in motion.

الأرض

The Earth is rotating or spinning around its axis. This is evidenced by day and night, at the equator the earth has an eastward velocity of 0.4651 kilometres per second (1،040 mph).[13] The Earth is also orbiting around the Sun in an orbital revolution. A complete orbit around the Sun takes one year, or about 365 days; it averages a speed of about 30 kilometres per second (67،000 mph).[14]

القارات

The Theory of Plate tectonics tells us that the continents are drifting on convection currents within the mantle, causing them to move across the surface of the planet at the slow speed of approximately 2.54 سنتيمتر (1 in) per year.[15][16] However, the velocities of plates range widely. The fastest-moving plates are the oceanic plates, with the Cocos Plate advancing at a rate of 75 ميليمتر (3.0 in) per year[17] and the Pacific Plate moving 52–69 ميليمتر (2.0–2.7 in) per year. At the other extreme, the slowest-moving plate is the Eurasian Plate, progressing at a typical rate of about 21 ميليمتر (0.83 in) per year.

الجسم الداخلي

The human heart is regularly contracting to move blood throughout the body. Through larger veins and arteries in the body, blood has been found to travel at approximately 0.33 m/s. Though considerable variation exists, and peak flows in the venae cavae have been found between 0.1 و 0.45 أمتار في الثانية (0.33 و 1.48 ft/s).[18] additionally, the smooth muscles of hollow internal organs are moving. The most familiar would be the occurrence of peristalsis which is where digested food is forced throughout the digestive tract. Though different foods travel through the body at different rates, an average speed through the human small intestine is 3.48 كيلومترات في الساعة (2.16 mph).[19] The human lymphatic system is also constantly causing movements of excess fluids, lipids, and immune system related products around the body. The lymph fluid has been found to move through a lymph capillary of the skin at approximately 0.0000097 m/s.[20]

الخلايا

The cells of the human body have many structures and organelles which move throughout them. Cytoplasmic streaming is a way in which cells move molecular substances throughout the cytoplasm,[21] various motor proteins work as molecular motors within a cell and move along the surface of various cellular substrates such as microtubules, and motor proteins are typically powered by the hydrolysis of adenosine triphosphate (ATP), and convert chemical energy into mechanical work.[22] Vesicles propelled by motor proteins have been found to have a velocity of approximately 0.00000152 m/s.[23]

الجسيمات

According to the laws of thermodynamics, all particles of matter are in constant random motion as long as the temperature is above absolute zero. Thus the molecules and atoms which make up the human body are vibrating, colliding, and moving. This motion can be detected as temperature; higher temperatures, which represent greater kinetic energy in the particles, feel warm to humans who sense the thermal energy transferring from the object being touched to their nerves. Similarly, when lower temperature objects are touched, the senses perceive the transfer of heat away from the body as a feeling of cold.[24]

Subatomic particles

Within the standard atomic orbital model, electrons exist in a region around the nucleus of each atom. This region is called the electron cloud. According to Bohr's model of the atom, electrons have a high velocity, and the larger the nucleus they are orbiting the faster they would need to move. If electrons were to move about the electron cloud in strict paths the same way planets orbit the Sun, then electrons would be required to do so at speeds which would far exceed the speed of light. However, there is no reason that one must confine oneself to this strict conceptualization (that electrons move in paths the same way macroscopic objects do), rather one can conceptualize electrons to be 'particles' that capriciously exist within the bounds of the electron cloud.[25] Inside the atomic nucleus, the protons and neutrons are also probably moving around due to the electrical repulsion of the protons and the presence of angular momentum of both particles.[26]

الضوء

Light moves at a speed of 299,792,458 m/s, or 299،792.458 kilometres per second (186،282.397 mi/s), in a vacuum. The speed of light in vacuum (or ) is also the speed of all massless particles and associated fields in a vacuum, and it is the upper limit on the speed at which energy, matter, information or causation can travel. The speed of light in vacuum is thus the upper limit for speed for all physical systems.

In addition, the speed of light is an invariant quantity: it has the same value, irrespective of the position or speed of the observer. This property makes the speed of light c a natural measurement unit for speed and a fundamental constant of nature.

In 2011, the speed of light was redefined alongside all seven SI base units using what it calls "the explicit-constant formulation", where each "unit is defined indirectly by specifying explicitly an exact value for a well-recognized fundamental constant", as was done for the speed of light. A new, but completely equivalent, wording of the metre's definition was proposed: "The metre, symbol m, is the unit of length; its magnitude is set by fixing the numerical value of the speed of light in vacuum to be equal to exactly 299792458 when it is expressed in the SI unit m s−1."[27] This implicit change to the speed of light was one of the changes that was incorporated in the 2019 redefinition of the SI base units, also termed the New SI.[28]

Superluminal motion

Some motion appears to an observer to exceed the speed of light. Bursts of energy moving out along the relativistic jets emitted from these objects can have a proper motion that appears greater than the speed of light. All of these sources are thought to contain a black hole, responsible for the ejection of mass at high velocities. Light echoes can also produce apparent superluminal motion.[29] This occurs owing to how motion is often calculated at long distances; oftentimes calculations fail to account for the fact that the speed of light is finite. When measuring the movement of distant objects across the sky, there is a large time delay between what has been observed and what has occurred, due to the large distance the light from the distant object has to travel to reach us. The error in the above naive calculation comes from the fact that when an object has a component of velocity directed towards the Earth, as the object moves closer to the Earth that time delay becomes smaller. This means that the apparent speed as calculated above is greater than the actual speed. Correspondingly, if the object is moving away from the Earth, the above calculation underestimates the actual speed.[30]

أنواع الحركة

- Simple harmonic motion – motion in which the body oscillates in such a way that the restoring force acting on it is directly proportional to the body's displacement. Mathematically Force is directly proportional to the negative of displacement. Negative sign signifies the restoring nature of the force. (e.g., that of a pendulum).

- Linear motion – motion which follows a straight linear path, and whose displacement is exactly the same as its trajectory. [Also known as rectilinear motion]

- Reciprocal motion

- Brownian motion – the random movement of very small particles

- Circular motion

- Rotatory motion – a motion about a fixed point. (e.g. Ferris wheel).

- Curvilinear motion – It is defined as the motion along a curved path that may be planar or in three dimensions.

- Rolling motion – (as of the wheel of a bicycle)

- Oscillatory – (swinging from side to side)

- Vibratory motion

- Combination (or simultaneous) motions – Combination of two or more above listed motions

- Projectile motion – uniform horizontal motion + vertical accelerated motion

الحركات الأساسية

تعريفات حديثة

شغلت الحركة فكر الإنسان منذ القدم، فكان أول اختراع له هو العجل ليتمكن من الحركة والتحريك بسهولة. أما اليوم فهي علم له قواعده ونظرياته ويتحكم في جميع وسائل حياة الإنسان.

الحركة

هي حالة لجسم غير ثابت إما أن ينتقل من نقطة إلى أخرى وتعرف هذه المسافةالمقطوعة بالإزاحة أو أن يدور حول نفسه. ولوصف حركة جسم معين وصفا كاملا، فلا بد من معرفة اتجاه (الإزاحة).

السرعة

وتعرف السرعة بأنها المسافة (الإزاحة) المقطوعة مقسومة على المدة الزمنية. سرعة = المسافة / الزمن. ويمكن قياس السرعة بوحدات كأن نقول كم/ساعة، أو ميل/ساعة، أو متر/ثانية. و ايضا هو التحرك او الانتقال من مكان إلى اخر ....

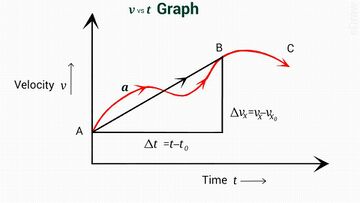

العجلة

العجلة هي المعدل الزمني لتغير السرعة، ويقسم التغير في السرعة على المدة الزمنية التي يستغرقها هذا التغير. وتقاس العجلة باستخدام وحدات مثل المتر في الثانية تربيع والقدم في الثانية تربيع.

تأثيرب حجم ووزن الجسم

بالنسبة لحجم أو وزن الجسم إذا كان الجسم صغيرا جدا بالمقارنة بالمسافات المقطوعة فلا توجد مشكلة رياضية. أما إذا كان الجسم كبيرا، فإن به نقطة تسمى مركز الثقل حيث يمكن اعتبار حركتها على أنها تسري على الجسم بأكمله.

وإذا كان الجسم يدور، فمن المناسب وصف حركته بدوران حول المحورإنگليزية: Axis يمر عبر مركز الثقل إنگليزية: Center of gravity.

تعريفات قديمة

تعريفات إخوان الصفا

في القرن الرابع الهجري (العاشر الميلادي) عرف إخوان الصفا في رسائلهم الحركة والسكون [31] على أنها صورة جعلتها النفس في الجسم بعد الشكل، وأن السكون هو عدم تلك الصورة؛ والسكون بالجسم أولى من الحركة لأن الجسم ذو جهات لا يمكنه أن يتحرك إلى جميع جهاته دفعة واحدة، وليست حركته إلى جهة أولى به من جهة، فالسكون به إذا أولى من الحركة.

وقد قسم إخوان الصفا الحركة إلى ستة أوجه:

- الكون : هو خروج الشيء من العدم إلى الوجود، أو من القوة إلى الفعل.

- الفساد : عكس ذلك.

- الزيادة : هي تباعد نهايات الجسم عن مركزه.

- النقصان : عكس ذلك.

- التغير : هو تبدل الصفات على الموصوف من الألوان والطعوم والروائح وغيرها من الصفات.

- النقلة : أما الحركة التي تسمى النقلة فهي عند جمهور الناس الخروج من مكان إلى مكان آخر، وقد يقال إن النقلة هي الكون في محاذاة ناحية أخرى من زمان ثان، وكلا القولين يصح في الحركة التي هي على سبيل الاستقامة؛ فأما التي على الاستدارة فلا يصح، لأن المتحرك على الاستدارة ينتقل من مكان إلى مكان، ولا يصير في محاذاة أخرى في زمان ثان، فإن قيل إن المتحرك على الاستدارة أجزاؤه كلها تتبدل أماكنها وتصير في محاذاة أخرى في زمان ثان إلا الجزء الذي هو ساكن في المركز فإنه ساكن فيه لا يتحرك. فليعلم من يقول هذا القول ويظن هذا الظن أو يقدر أ ن هذا الرأي صحيح، أن المركز إنما هو قطة متوهمة وهي رأس الخط، ورأس الخط لا يكون مكان الجزء من الجسم. وليعلم أيضا أن المتحرك على الاستدارة بجميع أجزائه متحرك، وهو لا ينتقل من مكان إلى مكان، ولا يصير محاذيا بشيء آخر في زمان ثان. فأما الحركة على الاستقامة فلا يمكن أن تكون إلا بالانتقال من مكان إلى مكان والمرور بمحاذيات في زمان ثان.

تعريفات ابن ملكا البغدادي

يقسم ابن ملكا الحركة في كتابه المعتبر في الحكمة إلى نوعين طبيعية وقسرية: [32]

"والقسرية يتقدمها الطبيعية، لأن المقسور إنما هو مقسور عن طبعه إلى طبع قاسرة" وبهذا المعنى يدرج ابن ملكا الحركة في الفلك العلوي مع تلك التابعة للجاذبية الأرضية أي ضمن الحركة الطبيعية باعتبار أن كلاهما يتبع ناموس إلهي في حركته، أما الحركة القسرية فهي تكون تحت تأثير قوة قسرية.

تعريفات ابن سينا

وعن الحركة القسرية يعرض ابن سينا في كتابه الشفاء ستة أمور ترتبط بحركة النقلة هي: [33]

- المتحرك : الجسم المتحرك

- المحرك : الشيء الباعث للحركةوالمحدث لها

- المحرك وما فيه : موضع الجسم

- المحرك وما منه : موضع بداية الحركة

- المحرك وما إليه : موضع انتهاء الحركة

- الزمان : الفترة الزمنية التي تستغرقها الحركة

الحركة الدائرية

وتعتبر الحركة الدائرية إنگليزية: Circular motion نوعا بسيطا آخر من أنواع الحركة. فإذا كان لجسم معين سرعة ثابتة ولكن كانت عجلته دائما على الزوايا اليمنى من سرعته، فسوف يتحرك في دائرة. وتوجه السرعة المطلوبة نحو مركز الدائرة وتسمى العجلة الجاذبة. وبالنسبة لجسم يتحرك في سرعة (ع) في دائرة ذات نصف قطر معين (نق)، ستكون العجلة الجاذبة على النحو التالي: ج = سرعة تربيع / نق

وفي هذا يذكر إخوان الصفا: واعلم أنه قد ظن كثير من أهل العلم أن المتحرك على الاستقامة يتحرك حركات كثيرة، لأنه يمر في حركته بمحاذيات كثيرة في حال حركته، ولا ينبغي أن تعتبر كثرة الحركات لكثرة المحاذيات، فإن السهم في مروره إلى أن يقع حركة واحدة يمر بمحاذيات كثيرة، وكذلك المتحرك على الاستدارة فحركته واحدة إلى أن يقف وإن كان يدور أدوارا كثيرة.

أنواع أخرى من الحركة

المقذوفات

وهناك نوع آخر بسيط من الحركة التي تلاحظ على الدوام وهي تحدث عندما تلقى كرة في زاوية معينة في الهواء. وبسبب الجاذبية، تتعرض الكرة لعجلة ثابتة إلى أسفل تقلل من سرعتها الأصلية التي يجب أن تكون لأعلى ثم بعد ذلك تزود من سرعتها لأسفل أثناء سقوط الكرة على الأرض. وفي نفس الوقت، فإن العنصر الأفقي من السرعة الأصلية يظل ثابتا (حيث يتجاهل مقاومة الهواء) مما يجعل الكرة تتحرك بسرعة ثابتة في الاتجاه الأفقي حتى ترتطم بالأرض. إن المكونات الأفقية والرأسية للحركة مستقلة عن بعضها الآخر ويمكن تحليل كل منها على حدة. ويكون المسار الناتج للكرة على شكل قطع ناقص. [34]

السرعة الثابتة

وهناك أنواع خاصة من الحركة يسهل وصفها. أولا، قد تكون السرعة ثابتة. وفي أبسط الحالات، قد تكون السرعة صفرا، وبالتالي لن يتغير الوضع أثناء المدة الزمنية. ومع ثبات السرعة، تكون السرعة المتوسطة مساوية للسرعة في أي زمن معين. إذا كان الزمن - ويرمز له بالرمز (ن) - يقاس بساعة تبدأ عندما يكون (ن)=0، عندئذ ستكون المسافة - ويرمز لها بالرمز (ف) - التي تقطع في سرعة ثابتة - ويرمز لها بالرمز (ع) - مساوية لإجمالي السرعة والزمن. ف = ع ن [35]

العجلة الثابتة

في النوع الثاني الخاص من الحركة، تكون العجلة ثابتة. وحيث أن السرعة تتغير، فلا بد من تعريف السرعة اللحظية أو السرعة التي تحدث في وقت معين. فبالنسبة للعجلة الثابتة (ج) التي تبدأ عند سرعة تقدر بصفر، فإن السرعة اللحظية ستساوي في زمن ما القيمة الآتية: ع = ج ن وستكون المسافة المقطوعة خلال هذا الوقت هي: ف = 1/ 2 ج ن2 [36]

من السمات الهامة الملحوظة في هذه المعادلة اعتماد المسافة على الزمن التربيعي (ن2). فالجسم الثقيل الذي يسقط سقوطا حرا يتعرض بالقرب من سطح الأرض لعجلة ثابتة. وفي هذه الحالة، ستكون العجلة 9.8 متر/ثانية تربيع. وفي نهاية الثانية الأولى، سوف تسقط كرة مثلا مسافة تقدر بـ 4.9 متر (16 قدم) وستكون سرعتها 9.8 متر/ثانية (32 قدم/ثانية). وفي نهاية الثانية الأخرى، سوف تسقط الكرة مسافة 19.6 متر، وستكون سرعتها 19.6 متر/ثانية.

القفز بالمظلة

اختراع مظلة القفز من الطائرات كان لأغراض عسكرية لأنه يمكن إنزال قوات عسكرية في أي مكان في الجو. فدور المظلة بصورتها الكلاسيكية القديمة هو ايقاف العجلة حتى تثبت سرعة القافز بالمظلة فيصل إلى الأرض سالما وكأنه قفز من مرتفع لا يتجاوز الأمتار الأربعة. طبعا المظلات الحديثة لها تقنيات حديثة تمكن القافز من التحكم بالمظلة بصورة كبيرة وبدقة متناهية.

حصائص الحركة

السرعة الاتجاهية

يُشار إلى معدل الحركة بالسرعة، بينما تصف السرعة الاتجاهية كلا من سرعة جسم واتجاهه. وعندما تتحرك سيارة على خطٍّ منحنٍ ولا يتغير عداد السرعة، يُقال إن السيارة تتحرك بسرعة ثابتة، بينما تتغير السرعة الاتجاهية لأن اتجاه الحركة يتغير. ويمكن التعبير عن كل من السرعة، والسرعة الاتجاهية بوحدات قياس متعددة توضح المسافة المقطوعة في فترة زمنية. ومن هذه الوحدات: الميل في الساعة، والقدم في الثانية، والسنتيمتر في الثانية. وعندما يكون كل من سرعة الجسم واتجاهه ثابتين، يُقال إن حركة الجسم منتظمة.

التسارع

يحدث التسارع عندما تتغير السرعة الاتجاهية للجسم. والتسارع هو التغير في السرعة الاتجاهية خلال فترة زمنية، ويُمثَّل بوحدات، مثل الكيلومتر في الساعة في الثانية، والمتر في الثانية في الثانية، أو السنتيمتر في الثانية في الثانية. فإذا تحركت سيارة بسرعة 3كم في الساعة في الثانية الأولى، وبسرعة 6كم في الساعة في الثانية التالية، وبسرعة 9كم في الساعة في الثانية الثالثة، فإنها تتحرك بتسارع منتظم مقداره 3كم في الساعة في الثانية، وتكون سرعة السيارة قد زادت بمقدار 3كم في الساعة لكل ثانية من زمن الحركة.

ويسمى النقص في سرعة جسم، مع مرور الزمن، تسارعًا سالبًا أو إبطاءً. مثال ذلك إبطاء السيارة وهي تقترب من إشارات المرور الحمراء. ويمكن أن يكون التسارع والإبطاء متغيرين أو منتظمين.

وأحد أمثلة التسارع المنتظم حالة دحرجة كرة أسفلَ مستوى مائل. تكون قيمة التسارع المنتظم للكرة مساوية لضعف المسافة التي تتدحرج فيها الكرة في الثانية الأولى من الحركة. فالكرة التي تتدحرج مترًا واحدًا في الثانية الأولى يكون لها تسارع مقداره 2م/ث/ث. كما يمكن أيضًا تحديد المسافة التي تقطعها الكرة والسرعة التي تصل إليها بعد فترة زمنية. وتتحدد المسافة من المعادلة:

ف = ½ س ن²

حيث (ف) هي المسافة، (س) هو التسارع، (ن) هو الزمن. أما السرعة (ع) فيمكن إيجادها من المعادلة:

ع = س ن

لذلك، إذا كانت قيمة التسارع المنتظم لكرة س ن، فإنها تكون قد قطعت 4م بعد ثانيتين، وتكون قيمة سرعتها 4م في الثانية.

وبالمثل، إذا تسارعت سيارة بمعدل ثابت قيمته 3م/ث/ث، تصبح سرعتها بعد خمس ثوان 15م/ث، وتكون قد قطعت مسافة 37,5م. وتصبح سرعتها بعد عشر ثوان 30م /ث، وتكون قد قطعت 150م.

ويحدث التسارع المنتظم أيضًا عندما يسقط جسم سقوطًا حرّا في الهواء. وفي هذه الحالة، تعطي جاذبية الأرض تسارعًا منتظمًا يساوي 8,9م/ث/ث. فالكرة الساقطة تحت تأثير الجاذبية الأرضية تقطع 4,9م في ثانية واحدة، وتقطع 19,6 م في ثانيتين. ولكن في حقيقة الأمر لا تسقط الأجسام تمامًا بهذا القدر بسبب مقاومة الهواء. وفي المعادلات التي تتناول تسارع الجاذبية الأرضية، يحل الرمز (جـ) محل الرمز (س).

الاندفاع والطاقة الحركية. يكون الاندفاع (ف) لجسم متحرك مساويًا لكتلته (ك) مضروبة في سرعته(ع)؛ أي ف = ك ع، والجسم الذي له اندفاع تكون له أيضًا طاقة حركية. وتسمى هذه الطاقة غالبًا الطاقة الحركية، وهي طاقة الجسم الناتجة بسبب حركته. وتكون الطاقة الحركية (طح) لجسم مساويًا لنصف كتلته مضروبًا في مربع سرعته. وتكتب العلاقة على النحو التالي:

طح = ½ ك ع²

وعندما تكتب بدلالة اندفاع الجسم تصبح الصيغة:

طح = ½ الاندفاع ع

وتتناسب قيمة الطاقة الحركية لجسم ما تناسبا طرديًّا مع مربع سرعته. فالسيارة التي تتحرك بسرعة 100كم/ الساعة تكون طاقتها الحركية أربعة أمثال طاقتها الحركية عند سرعة 50كم/الساعة. وهذه الزيادة في الطاقة الحركية تجعل تصادمات الأجسام عالية السّرعة أكثر خطورة من تصادمات الأجسام منخفضة السرعة. وعندما يصطدم جسم متحرك بآخر يحدث انتقال للطاقة وللاندفاع. وتسمى الطاقة المنتقلة من الجسم المتحرك الطاقة التأثيرية. ويكون للأجسام المتحركة بسرعة عالية طاقة تأثيرية كبيرة إذا اصطدمت بأجسام أخرى.

وإذا أثَّرت قوى على الأجسام لفترة من الزمن، فإن هذه الأجسام تكتسب اندفاعًا، وطاقة حركية. وكلما زاد زمن التأثير زادت قيمة الاندفاع، وقيمة الطّاقة الحركيّة. وفي رياضات مثل كرة المضرب، والجولف، يتابع اللاعبون الكرة بمضاربهم، بحيث تؤثّر القوة على الكرة أطول وقت ممكن. ونتيجة لذلك، تتحرك الكرة أسرع، ويكون لها اندفاع أكبر وطاقة حركية أكبر.

تأثير الاحتكاك على الحركة

إذا دحرجنا كرةً على الأرض، نلاحظ أنها تُبطئ في حركتها حتى تقف، بالرغم من عدم وجود قوة ظاهرة مؤثّرة عليها. والذي سبَّب التَّباطؤ، ثم التوقُّف هو الاحتكاك، أي مقاومة الحركة. ويعتبر الهواء من أكثر أسباب الاحتكاك شيوعًا، لذلك يتم تصنيع هياكل السيارات، والطائرات بشكل انسيابي حتى تتحرك بسهولة أكثر خلال الهواء.

ولكن الاحتكاك يمكن أن يكون من العوامل المساعدة على الحركة. فبدونه لا يُمكن للناس أن يمشوا على الأرض، بل ينزلقون. كما لا يمكننا ربط لوْحين بمسمار أو ربط أجسام معدنية بالمسمار الحلزوني إلا في وجود الاحتكاك الذي يمنعها من الانزلاق. وعندما تضغط على كوابح السيارة أو الدراجة، فإن الاحتكاك هو الذي يُبطئ الإطارات.

وفي حالات كثيرة، نحاول تقليل الاحتكاك بجعل أسطح الأجسام تتحرك بسهولة أكثر على بعضها. فعملية صقل الأسطح، أو وضع مادة، مثل زيت التشحيم بين سطحين جامدين تقلل من الاحتكاك. وتقوم الأجسام التي تدور حول محور، مثل المرفاع، ومُحَمِّل الكريات، والبكرات، بتقليل الاحتكاك كثيرًا. وهي تجعل دفع الأجسام الثّقيلة والكبيرة، مثل الأسِرَّة والسيارات، سهلاً.

قوانين الحركة لنيوتن

في القرن السابع عشر الميلادي، اقترح عالم الرياضيات الإنجليزي السير إسحق نيوتن ثلاثة قوانين للحركة، وقد مكَّنت هذه القوانين العلماء من وصف مجموعة كبيرة من الحركات. وفي الحقيقة كان العلماء العرب قد سبقوه في الإشارة إلى واحد من هذه القوانين الثلاثة. انظر: العلوم عند العرب والمسلمين (الفيزياء).

القانون الأول

ونصه: “كل جسم يبقى على حالته، من حيث السكون أو الحركة بسرعة منتظمة في خط مستقيم، ما لم تؤثرِّ عليه قوة تُغير من حالته”. وهذا يعني أن الجسم الساكن سوف يظل ساكنًا ما لم تؤثر عليه قوة تحرِّكه. ويُطلق على قانون نيوتن الأول مبدأ القصور الذاتي. والقصور الذاتي خاصية المادة التي تعبر عن استمرارية الحركة إذا كان الجسم متحركًا، أو استمرارية السكون، إن كان ساكنًا. والقوى التي تُغيِّر حركة الجسم يجب عليها أن تتغلّب أولاً على القصور الذاتي له. وكلما كانت كتلة الجسم كبيرة، كان من الصعوبة بمكان تحريك الجسم أو تغيير سرعته. ويُفيد القصور الذاتي في قياس صعوبة تحريك الأجسام. انظر: القصور الذاتي.

القانون الثاني

ونصه: “يتناسب التسارع المتولد في الجسم مع القوة المحدثة له، ويكون في اتجاهها”. وهو بذلك يصف كيفية تغيير الجسم لحركته عند تأثير قوة عليه. ويعتمد مقدار تغيير الحركة على مقدار القوة المؤثرة، وكتلة الجسم. فإذا زادت الكتلة، قلّ مقدار تغيير حركة الجسم، والعكس صحيح وذلك عند التأثير بقوة معينة على الجسم. ولذا ففي حالة تأثير القوة نفسها على جسمين، فإن تغيير حركة الجسم الأقل وزنًا يكون أكثر. وينص قانون نيوتن الثاني أيضًا على أن تأثير قوّة معينة يكون دائمًا في اتجاهها؛ فإذا دُفع جسم صوب الغرب، مثلاً، فإنه يتحرّك في هذا الاتجاه وليس الاتجاه المضاد. ويُكتب قانون نيوتن الثاني على النحو التالي:

ق = ك ت

حيث (ق) هي القوة المؤثرة، و(ك) الكتلة، و (ت) التسارع. ويستخدم العلماء هذه العلاقة لوصف حركة جميع أنواع الأجسام.

وتبعَا لقانون نيوتن الثاني، تتسبب القوى في إحداث تغييرات في حركة الأجسام. لنفترض أنّ شخصًا أطلق رصاصة من ماسورة بندقيّة في اتجاه أفقي، فحسب قانون نيوتن الأول، فإن الرّصاصة تستمر في الحركة في خط مستقيم للأبد ما لم تؤثّر عليها قوىً، ولكن جاذبية الأرض تؤثرِّ على الرصاصة وتسقطها نحو الأرض. يحدث هذا السُّقوط لأن قوة الجاذبية تجذب الرصاصة إلى أسفل، في اتجاه عموديّ على اتجاه الحركة.

إذا أطلقت الرصاصة أفقيًا من ارتفاع 4,9م فوق سطح الأرض، فإن الرصاصة سوف تتسارع بوساطة الجاذبية، وتصطدم بالأرض بعد ثانية واحدة ـ وهو الزمن الذي يستغرقه جسم ساقط من الارتفاع نفسه سقوطا حُرّا نحو الأرض. وبسبب الجاذبية، حُدِّد للبنادق والمدافع مدى مُعيَّن لإصابة الهدف، كما يجب أن تُطلق الرصاصات في اتجاه أعلى قليلاً لزيادة المدى ولتعويض مسافة السقوط.

القانون الثالث

ينص على أنه “لكل فعل رد فعل مساوٍ له في المقدار ومضاد له في الاتجاه”. فَعَلى سبيل المثال، عندما تتسرب الغازات من محرك الصاروخ أثناء الإقلاع، فإن الصاروخ يُدفَع إلى أعلى. تتسبب حركة الغازات المندفعة إلى أسفل في توليد ردِّ فعل يدفع الصاروخ إلى أعلى. ويمكِّن رد الفعل الصاروخ من التغلب على مقاومة الهواء، والصعود إلى الفضاء. وتوجد أمثلة أخرى كثيرة على قانون نيوتن الثالث. فعند انطلاق رصاصة من بندقيّة، يكون إطلاق الرّصاصة هو الفعل، وارتداد البندقيّة إلى الوراء هو ردّ الفعل، وينشأ كلاهما عن تمدُّد الغاز نتيجة تفجُّر البارود. كذلك دوران مرَشَّات العُشب في اتجاه رذاذ الماء في الاتجاه المضاد.

أحيانًا يكون من الصعوبة بمكان التعرف على ردّ الفعل. فعندما تقذف كرة نحو حائط، ثم ترتدّ الكرة، فإننا لا نرى الحائط يتحرك في الاتجاه المضادّ. ولكن هناك حركة صغيرة للمساحة التي ضُرِبَت من الحائط. وإذا ارتدّت الكرة من الأرض، فإن الكرة الأرضية تتحرّك في الاتجاه الآخر، ولكن لأن كتلة الأرض كبيرة للغاية، فإن هذه الحركة تكون ضئيلة جدًا ولا نستطيع أن نميزها.

تعديلات أُُدخلت على قوانين نيوتن. اقْتُرِحَتْ تعديلات في قوانين نيوتن، وبصفة خاصة في القانون الثاني، بوساطة الفيزيائي الألماني المولد ألبرت أينشتاين في بداية القرن الحاليّ. فمثلاً، توصل أينشتاين إلى أن كتلة الجسم يمكن أن تتغير مع تَغَيُّر سرعته بناء على نظريته النظرية النسبية الخاصة. ولكن هذا التأثير يكون ذا أهمية فقط عند السرعات القريبة من سرعة الضوء، وهي 299,792كم/الثانية.

انظر أيضاً

- Deflection (physics)

- Flow (physics)

- Kinematics

- Simple machines

- Kinematic chain

- Power

- Machine

- Microswimmer

- Motion (geometry)

- Motion capture

- Displacement

- Translatory motion

مصادر

- ^ Wahlin, Lars (1997). "9.1 Relative and absolute motion" (PDF). The Deadbeat Universe. Boulder, CO: Coultron Research. pp. 121–129. ISBN 978-0-933407-03-9. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 25 January 2013.

- ^ أ ب Tyson, Neil de Grasse; Charles Tsun-Chu Liu; Robert Irion (2000). One Universe : at home in the cosmos. Washington, DC: National Academy Press. ISBN 978-0-309-06488-0.

- ^ R.G. Lerner; George L. Trigg (1991). Encyclopedia of Physics (second ed.). New York: VCH Publishers. ISBN 0-89573-752-3. OCLC 20853637.

- ^ Hand, Louis N.; Janet D. Finch (1998). Analytical Mechanics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-57572-0. OCLC 37903527.

- ^ Newton's "Axioms or Laws of Motion" can be found in the "Principia" on p. 19 of volume 1 of the 1729 translation Archived 2015-09-28 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ "The Feynman Lectures on Physics Vol. I Ch. 38: The Relation of Wave and Particle Viewpoints". Archived from the original on 2022-08-14. Retrieved 2022-05-03.

- ^ "Understanding the Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle". ThoughtCo (in الإنجليزية). Archived from the original on 2022-05-10. Retrieved 2022-05-10.

- ^ Folger, Tim (October 23, 2018). "How Quantum Mechanics Lets Us See, Smell and Touch: How the science of the super small affects our everyday lives". Discovery Magazine. Archived from the original on January 26, 2021. Retrieved October 24, 2021.

- ^ Safkan, Yasar. "Question: If the term 'absolute motion' has no meaning, then why do we say that the earth moves around the sun and not vice versa?". Ask the Experts. PhysLink.com. Archived from the original on 3 November 2013. Retrieved 25 January 2014.

- ^ Hubble, Edwin (1929-03-15). "A relation between distance and radial velocity among extra-galactic nebulae". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 15 (3): 168–173. Bibcode:1929PNAS...15..168H. doi:10.1073/pnas.15.3.168. PMC 522427. PMID 16577160.

- ^ Kogut, A.; Lineweaver, C.; Smoot, G.F.; Bennett, C.L.; Banday, A.; Boggess, N.W.; Cheng, E.S.; de Amici, G.; Fixsen, D.J.; Hinshaw, G.; Jackson, P.D.; Janssen, M.; Keegstra, P.; Loewenstein, K.; Lubin, P.; Mather, J.C.; Tenorio, L.; Weiss, R.; Wilkinson, D.T.; Wright, E.L. (1993). "Dipole Anisotropy in the COBE Differential Microwave Radiometers First-Year Sky Maps". Astrophysical Journal. 419: 1. arXiv:astro-ph/9312056. Bibcode:1993ApJ...419....1K. doi:10.1086/173453. S2CID 209835274.

- ^ Imamura, Jim (August 10, 2006). "Mass of the Milky Way Galaxy". University of Oregon. Archived from the original on 2007-03-01. Retrieved 2007-05-10.

- ^ Ask an Astrophysicist Archived 2009-03-11 at the Wayback Machine. NASA Goodard Space Flight Center.

- ^ Williams, David R. (September 1, 2004). "Earth Fact Sheet". NASA. Archived from the original on 2013-05-08. Retrieved 2007-03-17.

- ^ Staff. "GPS Time Series". NASA JPL. Archived from the original on 2011-07-21. Retrieved 2007-04-02.

- ^ Huang, Zhen Shao (2001). Elert, Glenn (ed.). "Speed of the Continental Plates". The Physics Factbook. Archived from the original on 2020-06-19. Retrieved 2020-06-20.

- ^ Meschede, M.; Udo Barckhausen, U. (November 20, 2000). "Plate Tectonic Evolution of the Cocos-Nazca Spreading Center". Proceedings of the Ocean Drilling Program. Texas A&M University. Archived from the original on 2011-08-08. Retrieved 2007-04-02.

- ^ Wexler, L.; D H Bergel; I T Gabe; G S Makin; C J Mills (1 September 1968). "Velocity of Blood Flow in Normal Human Venae Cavae". Circulation Research. 23 (3): 349–359. doi:10.1161/01.RES.23.3.349. PMID 5676450.

- ^ Bowen, R (27 May 2006). "Gastrointestinal Transit: How Long Does It Take?". Pathophysiology of the digestive system. Colorado State University. Archived from the original on 3 April 2015. Retrieved 25 January 2014.

- ^ M. Fischer; U.K. Franzeck; I. Herrig; U. Costanzo; S. Wen; M. Schiesser; U. Hoffmann; A. Bollinger (1 January 1996). "Flow velocity of single lymphatic capillaries in human skin". Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 270 (1): H358–H363. doi:10.1152/ajpheart.1996.270.1.H358. PMID 8769772.

- ^ "cytoplasmic streaming – biology". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 2008-06-11. Retrieved 2022-06-23.

- ^ "Microtubule Motors". rpi.edu. Archived from the original on 2007-11-30.

- ^ Hill, David; Holzwarth, George; Bonin, Keith (2002). "Velocity and Drag Forces on motor-protein-driven Vesicles in Cells". APS Southeastern Section Meeting Abstracts. 69: EA.002. Bibcode:2002APS..SES.EA002H.

- ^ Temperature and BEC. Archived 2007-11-10 at the Wayback Machine Physics 2000: Colorado State University Physics Department

- ^ "Classroom Resources". anl.gov. Argonne National Laboratory. Archived from the original on 2010-06-08. Retrieved 2009-03-09.

- ^ "Chapter 2, Nuclear Science- A guide to the nuclear science wall chart. Berkley National Laboratory" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2009-03-04. Retrieved 2009-03-09.

- ^ "The "explicit-constant" formulation". BIPM. 2011. Archived from the original on 11 August 2014.

- ^ See, for example:

- Conover, Emily (2 November 2016). "Units of measure are getting a fundamental upgrade". Science News (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). Archived from the original on 6 February 2022. Retrieved 6 February 2022.

- Knotts, Sandra; Mohr, Peter J.; Phillips, William D. (January 2017). "An Introduction to the New SI". The Physics Teacher (in الإنجليزية). 55 (1): 16–21. Bibcode:2017PhTea..55...16K. doi:10.1119/1.4972491. ISSN 0031-921X. S2CID 117581000. Archived from the original on 2023-09-25. Retrieved 2022-08-20.

- "SI Redefinition". National Institute of Standards and Technology (in الإنجليزية). 11 May 2018. Archived from the original on 6 February 2022. Retrieved 6 February 2022.

- ^ Bond, H. E.; et al. (2003). "An energetic stellar outburst accompanied by circumstellar light echoes". Nature. 422 (6930): 405–408. arXiv:astro-ph/0303513. Bibcode:2003Natur.422..405B. doi:10.1038/nature01508. PMID 12660776. S2CID 90973.

- ^ Meyer, Eileen (June 2018). "Detection of an Optical/UV Jet/Counterjet and Multiple Spectral Components in M84". The Astrophysical Journal. 680 (1): 9. arXiv:1804.05122. Bibcode:2018ApJ...860....9M. doi:10.3847/1538-4357/aabf39. S2CID 67822924.

- ^ رسائل اخوان الصفا الحركة والسكون

- ^ كتاب المعتبر في الحكمة لابن ملكا البغدادي

- ^ كتاب الشفاء لابن سينا

- ^ Equation of motion

- ^ Equation of motion

- ^ Equation of motion

وصلات خارجية

- Feynman's lecture on motion

Media related to Motion at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Motion at Wikimedia Commons

- CS1 الإنجليزية الأمريكية-language sources (en-us)

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Articles with excerpts

- مقالات ذات عبارات بحاجة لمصادر

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Articles containing إنگليزية-language text

- Pages using Lang-xx templates

- Pages with empty portal template

- حركة (فيزياء)

- ميكانيكا

- ظواهر طبيعية

- فيزياء