ماتيو ريتشي

خادم الرب ماتيو ريتشي | |

|---|---|

پورتريه صيني لريتشي، من عام 1610 | |

| اللقب | Superior General of the China mission |

| شخصية | |

| ولد | 6 أكتوبر 1552 |

| توفي | 11 مايو 1610 (aged 57) |

| المثوى | مقبرة ژالان |

| الديانة | الكاثوليكية الرومانية |

| العرقية | إيطالي |

| أبرز الأعمال | كونيو وانگوو چوانتو |

| الخدمة العسكرية | |

| الرتبة | Superior General |

| المرتبة | جمعية يسوع |

| مناصب رفيعة | |

| الفترة في المنصب | 1597–1610 |

| تابعه | نيكولو لونگوباردو |

| سبب المغادرة | وفاته |

| ماتيو ريتشي | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

تمثال ريتشي في وسط ماكاو، أزيح الستار عنه في 7 أغسطس 2010، في ذكرى وصوله للجزيرة | |||||||||

| الصينية التقليدية | 利瑪竇 | ||||||||

| الحروف المبسطة | 利玛窦 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Courtesy Name: Xitai | |||||||||

| الصينية التقليدية | 西泰 | ||||||||

| الحروف المبسطة | 西泰 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

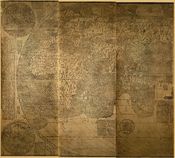

ماتيو ريتشي Matteo Ricci، S.J. (النطق بالإيطالية: [matˈtɛːo ˈrittʃi]؛ لاتينية: Mattheus Riccius Maceratensis؛ 6 أكتوبر 1552 – 11 مايو 1610)، كان قساً يسوعياً إيطالياً وأحد الشخصيات المؤسسة في الإرساليات اليسوعية إلى الصين. خريطته للعالم في 1602 بالحروف الصينية قدّمت نتائج الاستكشافات الأوروپية إلى شرق آسيا. ويُعتبر خادم الرب في الكاثوليكية الرومانية.

وصل ريتشي إلى المستوطنة البرتغالية مكاو في 1582 حيث بدأ عمله التبشيري في الصين. وقد أصبح أول أوروبي يدخل المدينة المحرمة في بكين في 1601 حين دعاه الامبراطور وانلي، الذي طلب خدماته الخاصة في أمور مثل فلك البلاط و علم التقويم. وقد أقنع العديد من المسئولين البارزين الصينيين باعتناق الكاثوليكية، مثل زميله شو گوانگچي، الذي ساعده في ترجمة العناصر لإقليدس إلى الصينية وكذلك الكلاسيكيات الكونفوشية إلى اللاتينية لأول مرة.

النشأة

وُلِد ريتشي في 6 أكتوبر 1552، في ماتشراتا، في الدويلات الپاپوية، وحالياً هي مدينة في منطقة ماركى الإيطالية. وقد قام بدراساته الكلاسيكية في مسقط رأسه ثم درس القانون في روما لعامين. ثم انضم لجمعية يسوع في أبريل 1571 في الكلية الرومانية. وبينما كان هناك، بالإضافة للفلسفة واللاهوت، فقد درس أيضاً الرياضيات وقراءة الطالع والفلك تحت إشراف الأب كريستوفر كلاڤيوس. وفي 1577، تقدم بطلب الالتحاق بتجريدة إرسالية إلى الشرق الأقصى. وأبحر من لشبونة، البرتغال في مارس 1578 ووصل گوا، المستعمرة البرتغالية، في سبتمبر التالي. وبقي ريتشي هناك عاملاً في التعليم والإكليروس حتى نهاية الصوم الكبير، 1582، حين اِستُدعي إلى مكاو للاستعداد لدخول الصين. وصل ريتشي مكاو في مطلع أغسطس.[1]

ريتشي في الصين

في أغسطس 1582، وصل ريتشي إلى مكاو، نقطة التجارة البرتغالية في بحر الصين الجنوبي. At the time, Christian missionary activity in China was almost completely limited to Macau, where some of the local Chinese people had converted to Christianity and lived in the Portuguese manner. No Christian missionary had attempted seriously to learn the Chinese language until 1579 (three years before Ricci's arrival), when Michele Ruggieri was invited from Portuguese India expressly to study Chinese, by Alessandro Valignano, founder of St. Paul Jesuit College (Macau), and to prepare for the Jesuits' mission from Macau into بر الصين الرئيسي.[2]

وما أن وصل مكاو، درس ريتشي اللغة والعادات الصينية. وكانت بداية مشروع طويل جعله أحد أوائل الدارسين الغربيين الذين تمكنوا من ناصية الكتابة الصينية والصينية الكلاسيكية. With Ruggieri, he traveled to Guangdong's major cities, Canton and Zhaoqing (then the residence of the Viceroy of Guangdong and Guangxi), seeking to establish a permanent Jesuit mission outside Macau.[1]

There is now a memorial plaque in Zhaoqing to commemorate Ricci's six-year stay there, as well as a "Ricci Memorial Centre"[3] in a building dating from the 1860s.

Expelled from Zhaoqing in 1589, Ricci obtained permission to relocate to Shaoguan (Shaozhou, in Ricci's account) in the north of the province, and reestablish his mission there.[4]

في 1583, Ricci and Ruggieri settled in Zhaoqing, at the invitation of the governor of Zhaoqing, Wang Pan, who had heard of Ricci's skill as a mathematician and cartographer. Ricci stayed in Zhaoqing from 1583 to 1589, when he was expelled by a new viceroy. It was in Zhaoqing, in 1584, that Ricci composed the first European-style world map in Chinese, called "Da Ying Quan Tu"(الصينية: 大瀛全圖; lit. 'Complete Map of the Great World')[5]. No prints of the 1584 map are known to exist, but, of the much improved and expanded Kunyu Wanguo Quantu of 1602,[6] six recopied, rice-paper versions survive.[7]

مقاربة ريتشي للثقافة الصينية

Ricci could speak Chinese as well as read and write classical Chinese, the literary language of scholars and officials. He was known for his appreciation of Chinese culture in general but condemned the prostitution which was widespread in Beijing at the time.[8] During his research, he discovered that in contrast to the cultures of South Asia, Chinese culture was strongly intertwined with Confucian values and therefore decided to use existing Chinese concepts to explain Christianity[9]. With Superior Valignano's formal approval, he aligned himself with the Confucian intellectually elite literati,[10] and even adopted their mode of dress. He did not explain the Catholic faith as entirely foreign or new; instead, he said that the Chinese culture and people always believed in God and that Christianity is simply the completion of their faith.[11] He borrowed an unusual Chinese term, Tiānzhǔ (天主, "Lord of Heaven") to describe the God of Abraham, despite the term's origin in traditional Chinese worship of Heaven. (He also cited many synonyms from the Confucian Classics.) He supported Chinese traditions by agreeing with the veneration of family ancestors. Dominican and Franciscan missionaries considered this an unacceptable accommodation, and later appealed to the Vatican on the issue.[11] This Chinese rites controversy continued for centuries, with the most recent Vatican statement as recently as 1939. Some contemporary authors have praised Ricci as an exemplar of beneficial inculturation,[12][13] avoiding at the same time distorting the Gospel message or neglecting the indigenous cultural media.[14]

Like developments in India, the identification of European culture with Christianity led almost to the end of Catholic missions in China, but Christianity continued to grow in Sichuan and some other locations.[11]

Xu Guangqi and Ricci become the first two to translate some of the Confucian classics into a western language, Latin.

Ricci also met a Korean emissary to China, Yi Sugwang. He taught Yi the basic tenets of Catholicism and gave him several books concerning the west which were incorporated into his Jibong Yuseol, the first Korean encyclopedia.[15] Along with João Rodrigues's gifts to the ambassador Jeong Duwon in 1631, Ricci's gifts influenced the creation of Korea's Silhak movement.[16]

سبب تطويبه

سبب تطويبه، الذي بدأ في الأصل في 1984، كان قد أعيد فتحه في 24 يناير 2010، في كاتدرائية أبرشية ماتشراتا-تولنتينو-ركاناتي-تشنگولي-تريا الإيطالية.[17][18] الأسقف كلاوديو جوليودوري، الاداري الرسولي لأبرشية ماتشراتا، أغلق رسميا الطور الأسقفي من عملية التقديس في 10 مايو 2013. وانتقلت العملية إلى مجمع طلبات التقديس في الڤاتيكان في 2014.

تخليد ذكراه

The following places and institutions are named after Matteo Ricci:

- Matteo Ricci Pacific Studies Reading Room at The National Central Library في تايوان

- Ricci Hall,[19] a dormitory at The University of Hong Kong

- Ricci Building, a building at Wah Yan College, Kowloon in Hong Kong

- The Matteo Ricci Study Hall,[20] at the Ateneo de Manila University

- Matteo Ricci College, Kowloon[21] in Hong Kong

- Matteo Ricci College,[22] at Seattle University

- Colégio Mateus Ricci,[23] Macau

- Sekolah Katolik Ricci 1 and 2 in Jakarta, Indonesia

- Taipei Ricci Institute, Taiwan

- Macau Ricci Institute,[24] Macau[25]

- Ricci Institute for Chinese-Western Cultural History[26] at the University of San Francisco.

- The Matteo Ricci Seminar at Fordham University[27]

- Matteo Ricci Hall-"R" Hall,[28] Ricci Hall Annex-"RA" Hall,[28] two buildings at Sogang University in Seoul, South Korea

In the run-up to the 400th anniversary of Ricci's death, the Vatican Museums hosted a major exhibit dedicated to his life. Additionally, Italian film director Gjon Kolndrekaj produced a 60-minute documentary about Ricci, released in 2009, titled Matteo Ricci: A Jesuit in the Dragon's Kingdom, filmed in Italy and China.[29][30]

In Taipei, the Taipei Ricci Institute and the National Central Library of Taiwan opened jointly the Matteo Ricci Pacific Studies Reading Room[31] and the Taipei-based online magazine eRenlai, directed by Jesuit Benoît Vermander, dedicated its June 2010 issue to the commemoration of the 400th anniversary of Ricci's death.[32]

المعنى الحقيقي لسيد السماء

The True Meaning of the Lord of Heaven (天主實義) is a book written by Ricci, which argues that Confucianism and Christianity are not opposed and in fact are remarkably similar in key respects. Ricci used the treatise in his missionary effort to convert Chinese literati, men who were educated in Confucianism and the Chinese classics. There was controversy over whether Ricci and other Jesuits had gone too far and changed Christian beliefs to win converts.

Peter Phan argues that True Meaning was used by a Jesuit missionary to Vietnam, Alexandre de Rhodes, in writing a catechism for Vietnamese Christians.[33] In 1631, Girolamo Maiorica and Bernardino Reggio, both Jesuit missionaries to Vietnam, started a short-lived press in Thăng Long (present-day Hanoi) to print copies of True Meaning and other texts.[34] The book was also influential on later Protestant missionaries to China, James Legge and Timothy Richard, and through them John Nevius, John Ross, and William Edward Soothill, all influential in establishing Protestantism in China and Korea.

الأعمال

- De Christiana expeditione apud Sinas: the journals of Ricci that were completed and translated into Latin by another Jesuit, Nicolas Trigault, soon after Ricci's death. Available in various editions:

- Trigault, Nicolas S. J. "China in the Sixteenth Century: The Journals of Mathew Ricci: 1583-1610". English translation by Louis J. Gallagher, S.J. (New York: Random House, Inc. 1953).

- On Chinese Government,[35] an excerpt from Chapter One of Gallagher's translation.

- De Christiana expeditione apud Sinas,[36] full Latin text, available on Google Books

- A discourse of the Kingdome of China, taken out of Ricius and Trigautius, containing the countrey, people, government, religion, rites, sects, characters, studies, arts, acts; and a Map of China added, drawne out of one there made with Annotations for the understanding thereof (an early English translation of excerpts from De Christiana expeditione) in Purchas his Pilgrimes (1625). Can be found in the "Hakluytus posthumus".[37] The book also appears on Google Books, but only in snippet view.[38]

- An excerpt from The Art of Printing by Matteo Ricci[39]

- Ricci's World Map of 1602[40]

- Rare 1602 World Map, the First Map in Chinese to Show the Americas, on Display at Library of Congress, 12 Jan to 10 April 2010.[41]

- The Chinese translation of the ancient Greek mathematical treatise Euclid's Elements (幾何原本), published and printed in 1607 by Matteo Ricci and his Chinese colleague Xu Guangqi

انظر أيضاً

- 19th-century Protestant missions in China

- المسيحية في الصين

- Horses in East Asian warfare

- Jesuit China missions

- List of Chinese Roman Catholics

- List of Jesuit scientists

- List of Protestant missionaries in China

- List of Roman Catholic missionaries in China

- List of Roman Catholic scientist-clerics

- Religion in China

- Xu Guangqi

- Diego de Pantoja

- Kunyu Wanguo Quantu

- Zhang Dai

- Far West (Taixi)

- Three Pillars of Chinese Catholicism

المراجع

الهامش

- ^ أ ب Brucker, Joseph (1912). "Matteo Ricci". The Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. OCLC 174525342. Retrieved 17 August 2017.

- ^ Gallagher (trans) (1953), pp. 131-132, 137

- ^ "Ricci Memorial Centre". Oneminuteenglish.com. Retrieved 14 May 2014.

- ^ Gallagher (253), pp. 205-227

- ^ TANG Kaijian and ZHOU Xiaolei, "Four Issues in the Dissemination of Matteo Ricci's World Map during the Ming Dynasty", in STUDIES IN THE HISTORY OF NATURAL SCIENCES, Vol. 34, No. 3 (2015), pp. 294-315. 汤开建 周孝雷 《明代利玛窦世界地图传播史四题》,《自然科学史研究》第34卷,第3期(2015年):294-315

- ^ Baran, Madeleine (16 December 2009). "Historic map coming to Minnesota". St. Paul, Minnesota.: Minnesota Public Radio. Retrieved 12 January 2010.

- ^ "Ancient map with China at centre goes on show in US". BBC News. 12 January 2010.

- ^ Hinsch, Bret (1990). Passions of the Cut Sleeve : The Male Homosexual Tradition in China. University of California Press. p. 2. ISBN 0-520-06720-7.

- ^ Zvi Ben-Dor Benite, "Western Gods Meet in the East": Shapes and Contexts of the Muslim-Jesuit Dialogue in Early Modern China, Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient, Vol. 55, No. 2/3, Cultural Dialogue in South Asia and Beyond: Narratives, Images and Community (sixteenth-nineteenth centuries) (2012), pp. 517-546.

- ^ Bashir, Hassan Europe and the Eastern Other Lexington Books 2013 p.93 ISBN 9780739138038

- ^ أ ب ت Franzen, August (1988). Kleine Kirchengeschichte. Freiburg: Herder. ISBN 3-451-08577-1.

- ^ Griffiths, Bede (1965), "The meeting of East and West", in Derrick, Christopher, Light of Revelation and Non-Christians, New York, NY: Alba House

- ^ Dunn, George H. (1965), "The contribution of China's culture towards the future of Christianity", in Derrick, Christopher, Light of Revelation and Non-Christians, New York, NY: Alba House

- ^ Zhiqiu Xu (2016). Natural Theology Reconfigured: Confucian Axiology and American Pragmatism. New York: Routledge – via Google Books.

- ^ National Assembly, Republic of Korea: Korea History

- ^ Bowman, John S. (2000). Columbia Chronologies of Asian history and Culture. Columbia University Press. p. 212. ISBN 0-231-11004-9.

- ^ "Father Matteo Ricci's beatification cause reopened". Catholicculture.org. Retrieved 14 May 2014.

- ^ "Diocese to re-launch beatification cause for missionary Fr. Matteo Ricci". Catholicnewsagency.com. 25 January 2010. Retrieved 14 May 2014.

- ^ "Ricci Hall - The University of Hong Kong". www.hku.hk. Retrieved 17 August 2017.

- ^ http://rizal.lib.admu.edu.ph/matteo/

- ^ "web.mrck.edu.hk". mrck.edu.hk. Retrieved 17 August 2017.

- ^ "Matteo Ricci College - Seattle University". www2.seattleu.edu. Retrieved 17 August 2017.

- ^ "首頁 - Colegio Mateus Ricci". www.ricci.edu.mo. Retrieved 17 August 2017.

- ^ INSTITUTE, MACAU RICCI. "MACAU RICCI INSTITUTE". www.riccimac.org. Retrieved 17 August 2017.

- ^ "The Macau Ricci Institute 澳門利氏學社". Riccimac.org. Retrieved 14 May 2014.

- ^ "Home". www.usfca.edu. Retrieved 17 August 2017.

- ^ Fordham. "Fordham online information - Academics - Colleges and Schools - Undergraduate Schools - Fordham College at Rose Hill". www.fordham.edu. Retrieved 17 August 2017.

- ^ أ ب http://hompi.sogang.ac.kr/goabroad/english/lifesogang/campus.htm

- ^ "A Jesuit in the dragon's kingdom". H2onews.org. Retrieved 14 May 2014.

- ^ Category: Focus: The Legacy of Matteo Ricci (20 May 2010). "Interview with Gjon Kolndrekaj". Erenlai.com. Retrieved 14 May 2014.

- ^ Category: Focus: The Legacy of Matteo Ricci (20 May 2010). "Remembering Ricci: Opening of the Matteo Ricci - Pacific Studies Reading Room at the National Central Library". www.eRenlai.com. Retrieved 14 May 2014.

- ^ "June 2010". www.eRenlai.com. Retrieved 14 May 2014.

- ^ Phan, Peter C. (2015). Mission and Catechesis: Alexandre de Rhodes & Inculturation in Seventeenth-Century Vietnam. Orbis Books. ISBN 978-1-60833-474-2. Retrieved 1 February 2017. Note: Phan offers a concise summary of the contents of True Meaning as well.

- ^ Alberts, Tara (2012). "Catholic Written and Oral Cultures in Seventeenth-Century Vietnam". Journal of Early Modern History. Leiden: Koninklijke Brill. 16: 390. doi:10.1163/15700658-12342325.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Halsall, Paul. "Chinese Cultural Studies: Matteo Ricci: On Chinese Government, Selection from his Journals (1583-1610 CE)". acc6.its.brooklyn.cuny.edu. Retrieved 17 August 2017.

- ^ Ricci, Matteo; Trigault, Nicolas (17 August 2017). "De Christiana expeditione apud sinas suscepta ab Societate Jesu. Ex P. Matthaei Riccii eiusdem Societatis commentariis Libri V: Ad S.D.N. Paulum V. In Quibus Sinensis Regni mores, leges, atque instituta, & novae illius Ecclesiae difficillima primordia accurate & summa fide describuntur". Gualterus. Retrieved 17 August 2017 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Full text of "Hakluytus posthumus"". archive.org. Retrieved 17 August 2017.

- ^ Purchas, Samuel (17 August 2017). "Hakluytus Posthumus, Or, Purchas His Pilgrimes: Contayning a History of the World in Sea Voyages and Lande Travells by Englishmen and Others". J. MacLehose and Sons. Retrieved 17 August 2017 – via Google Books.

- ^ http://academic.brooklyn.cuny.edu/core9/phalsall/texts/ric-prt.html

- ^ http://www.henry-davis.com/MAPS/Ren/Ren1/441.html

- ^ "Rare 1602 World Map, the First Map in Chinese to Show the Americas, on Display at Library of Congress, Jan. 12 to April 10". loc.gov. Retrieved 17 August 2017.

ببليوگرافيا

- Dehergne, Joseph, S.J. (1973). Répertoire des Jésuites de Chine de 1552 à 1800. Rome: Institutum Historicum S.I. OCLC 462805295

- Hsia, R. Po-chia. (2007). "The Catholic Mission and translations in China, 1583–1700" in Cultural Translation in Early Modern Europe (Peter Burke and R. Po-chia Hsia, eds.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521862080 ISBN 0521862086; OCLC 76935903

- Spence, Jonathan D.. (1984). The Memory Palace of Matteo Ricci. New York: Viking. ISBN 9780670468300; OCLC 230623792

- Vito Avarello, L'oeuvre italienne de Matteo Ricci : anatomie d'une rencontre chinoise, Paris, Classiques Garnier, 2014, 738p. (ISBN 978-2-8124-3107-4)

للاستزادة

- Cronin, Vincent. (1955). The Wise Man from the West: Matteo Ricci and his Mission to China. (1955). OCLC 664953 N.B.: A convenient paperback reissue of this study was published in 1984 by Fount Paperbacks, ISBN 0-00-626749-1.

- Gernet, Jacques. (1981). China and the Christian Impact: a conflict of cultures. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521313198 ISBN 9780521313193; OCLC 21173711

- George L. Harris, "The Mission of Matteo Ricci, S.J.: A Case Study of an Effort at Guided Culture Change in China in The Sixteenth Century", in Monumenta Serica, Vol. XXV, 1966 (168 pp.).

- Simon Leys, Madness of the Wise : Ricci in China, an article from his book, The Burning Forest (1983). This is an interesting account, and contains a critical review of The Memory Palace by Jonathan D. Spence.

- Mao Weizhun, « European influences on Chinese humanitarian practices. A longitudinal study » in : Emulations - Journal of young scholars in Social Sciences, n°7 (June 2010).

- [[[:قالب:Wdl]] "職方外紀 六卷卷首一卷"] [Chronicle of Foreign Lands]. World Digital Library. 1623.

{{cite web}}: Check|url=value (help) This book explains Matteo Ricci's world map of 1574. - 《利瑪竇世界地圖研究》(A Study of Matteo Ricci's World Map), book in Chinese by HUANG Shijian and GONG Yingyan (黃時鑒 龔纓晏), 上海古籍出版社 (Shanghai Ancient Works Publishing House), 2004年, ISBN 9787532536962

وصلات خارجية

- Inculturation: Matteo Ricci's Legacy in China [Short videos from Georgetown's Ricci Legacy Symposium.]

- University of Scranton: Matteo Ricci, S.J.

- The Zhaoqing Ricci Center

- Article about the tomb of Matteo Ricci in Beijing

- Ricci Institute for Chinese-Western Cultural History

- Rotary Club Macerata Matteo Ricci (in Italian)

- Matteo Ricci moves closer toward beatification

- Articles having same image on Wikidata and Wikipedia

- Articles containing صينية-language text

- Articles containing لاتينية-language text

- Pages using Lang-xx templates

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Articles containing Chinese-language text

- CS1 errors: URL

- Portal-inline template with redlinked portals

- Pages with empty portal template

- 1552 births

- 1610 deaths

- 16th-century Italian mathematicians

- 16th-century Italian writers

- 17th-century Italian writers

- 17th-century male writers

- 17th-century cartographers

- 17th-century Italian mathematicians

- 17th-century Jesuits

- 17th-century translators

- Chinese–Italian translators

- Italian cartographers

- Italian expatriates in China

- Italian Jesuits

- Italian Roman Catholic missionaries

- Italian Servants of God

- Italian sinologists

- Italian–Latin translators

- Jesuit missionaries in China

- Jesuit scientists

- Latin-Italian translators

- People from Macerata

- Catholic clergy scientists

- Translators from Chinese