زاوية مجسمة

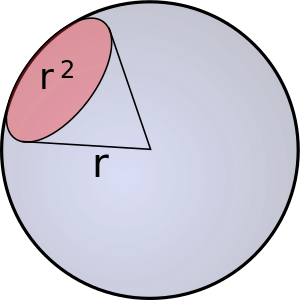

الزاوية المجسمة أو الزاوية الصلبة (إنگليزية: solid angle) هي زاوية في الفضاء الثلاثي الأبعاد التي تقيس الحجم الظاهري لجسم فراغي من قبل مراقب من نقطة معينة. فإن جسم فراغي صغير قريب قد يبدو بحجم جسم ذو حجم كبير ولكنه بعيد من الناظر. الزاوية الصلبة تتناسب مع مساحة السطح، S، لمسقط الجسم على كرة متمركزة عند نقطة المراقبة، مقسومة على مربع نصف قطر تلك الكرة، R، بالعلاقة:

| زاوية مجسمة Solid angle | |

|---|---|

تمثيل رسومي لدرجة 1 ستراديان | |

الرموز الشائعة | Ω |

| الوحدة الدولية | ستراديان |

وحدات أخرى | Square degree |

| In الوحدة الدولية الأساسية | m2/m2 |

| بعد قياسي SI | |

| البعد | |

Ω = k S/R2

حيث Ω هي الزاوية الصلبة

S مساحة سطح مسقط الجسم على كرة متمركزة عن نقطة المراقبة

R نصف قطر الكرة

k عامل تناسب.

علاقة الزاوية الصلبة بسطح الكرة ، مشابه لعلاقة الزاوية بمحيط الدائرة. كل الاختلاف ينحصر في كون الزاوية العادية مسطحة ، أما الزاوية الصلبة فهي فراغية .هندسة فراغية

إذا اختير عامل التناسب مساويًا للواحد، تكون عندها واحدة الزاوية الصلبة وفق النظام الدولي للواحدات هي ستراديان وتختصر (sr). وهكذا تكون الزاوية الصلبة لكرة مقاسة من نقطة في داخلها هو 4π sr، والزاوية الصلبة الناتجة في مركز مكعب بالنسبة لأحد أضلاعه هي سدس هذه القيمة أي 2π/3 sr.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

تطبيقات عملية

- Defining luminous intensity and luminance, and the correspondent radiometric quantities radiant intensity and radiance

- Calculating spherical excess E of a spherical triangle

- The calculation of potentials by using the boundary element method (BEM)

- Evaluating the size of ligands in metal complexes, see ligand cone angle

- Calculating the electric field and magnetic field strength around charge distributions

- Deriving Gauss's Law

- Calculating emissive power and irradiation in heat transfer

- Calculating cross sections in Rutherford scattering

- Calculating cross sections in Raman scattering

- The solid angle of the acceptance cone of the optical fiber

الزوايا المجسمة للأغراض الشائعة

القمع والطاقية الكروية ونصف الكرة

The solid angle of a cone with its apex at the apex of the solid angle, and with apex angle 2θ, is the area of a spherical cap on a unit sphere

For small θ such that cos θ ≈ 1 - θ2/2, this reduces to the area of a circle πθ2.

The above is found by computing the following double integral using the unit surface element in spherical coordinates:

This formula can also be derived without the use of calculus. Over 2200 years ago Archimedes proved that the surface area of a spherical cap is always equal to the area of a circle whose radius equals the distance from the rim of the spherical cap to the point where the cap's axis of symmetry intersects the cap.[1] In the diagram this radius is given as:

Hence for a unit sphere the solid angle of the spherical cap is given as:

When θ = π/2, the spherical cap becomes a hemisphere having a solid angle 2π.

The solid angle of the complement of the cone is:

This is also the solid angle of the part of the celestial sphere that an astronomical observer positioned at latitude θ can see as the earth rotates. At the equator all of the celestial sphere is visible; at either pole, only one half.

The solid angle subtended by a segment of a spherical cap cut by a plane at angle γ from the cone's axis and passing through the cone's apex can be calculated by the formula:[2]

For example, if γ=-θ, then the formula reduces to the spherical cap formula above: the first term becomes π, and the second πcosθ.

رباعي الأسطح

Let OABC be the vertices of a tetrahedron with an origin at O subtended by the triangular face ABC where are the vector positions of the vertices A, B and C. Define the vertex angle θa to be the angle BOC and define θb, θc correspondingly. Let be the dihedral angle between the planes that contain the tetrahedral faces OAC and OBC and define , correspondingly. The solid angle Ω subtended by the triangular surface ABC is given by

This follows from the theory of spherical excess and it leads to the fact that there is an analogous theorem to the theorem that "The sum of internal angles of a planar triangle is equal to π", for the sum of the four internal solid angles of a tetrahedron as follows:

where ranges over all six of the dihedral angles between any two planes that contain the tetrahedral faces OAB, OAC, OBC and ABC.[3]

A useful formula for calculating the solid angle Ω subtended by the triangular surface ABC where are the vector positions of the vertices A, B and C has been given by Oosterom and Strackee [4] (although the result was known earlier by Euler and Lagrange[5]):

حيث

denotes the scalar triple product of the three vectors;

- is the vector representation of point A, while a is the magnitude of that vector (the origin-point distance)

- denotes the scalar product.

When implementing the above equation care must be taken with the atan function to avoid negative or incorrect solid angles. One source of potential errors is that the scalar triple product can be negative if a, b, c have the wrong winding. Computing abs(det) is a sufficient solution since no other portion of the equation depends on the winding. The other pitfall arises when the scalar triple product is positive but the divisor is negative. In this case atan returns a negative value that must be increased by π.

Another useful formula for calculating the solid angle of the tetrahedron at the origin O that is purely a function of the vertex angles θa, θb, θc is given by L'Huilier's theorem[6][7] as

where

الهرم

The solid angle of a four-sided right rectangular pyramid with apex angles a and b (dihedral angles measured to the opposite side faces of the pyramid) is

If both the side lengths (α and β) of the base of the pyramid and the distance (d) from the center of the base rectangle to the apex of the pyramid (the center of the sphere) are known, then the above equation can be manipulated to give

The solid angle of a right n-gonal pyramid, where the pyramid base is a regular n-sided polygon of circumradius r, with a pyramid height h is

The solid angle of an arbitrary pyramid with an n-sided base defined by the sequence of unit vectors representing edges {s1, s2}, ... sn can be efficiently computed by:[2]

where parentheses (* *) is a scalar product and square brackets [* * *] is a scalar triple product, and i is an imaginary unit. Indices are cycled: s0 = sn and s1 = sn + 1.

زاوية خط الطول والعرض

الزاوية المجسمة لمستطيل خطي الطول والعرض على كرة هي

- ,

where φN and φS are north and south lines of latitude (measured from the equator in radians with angle increasing northward), and θE and θW are east and west lines of longitude (where the angle in radians increases eastward).[8] Mathematically, this represents an arc of angle ϕN − ϕS swept around a sphere by θE − θW radians. When longitude spans 2π radians and latitude spans π radians, the solid angle is that of a sphere.

A latitude-longitude rectangle should not be confused with the solid angle of a rectangular pyramid. All four sides of a rectangular pyramid intersect the sphere's surface in great circle arcs. With a latitude-longitude rectangle, only lines of longitude are great circle arcs; lines of latitude are not.

الشمس والقمر

The Sun is seen from Earth at an average angular diameter of 0.5334 degrees or 9.310×10-3 radians. The Moon is seen from Earth at an average angular diameter of 9.22×10-3 radians. We can substitute these into the equation given above for the solid angle subtended by a cone with apex angle 2θ:

The resulting value for the Sun is 6.807×10-5 steradians. The resulting value for the Moon is 6.67×10-5 steradians. In terms of the total celestial sphere, the Sun and the Moon subtend fractional areas of 0.000542% (Sun) and 0.000531% (Moon). On average, the Sun is larger in the sky than the Moon even though it is much, much farther away.

الزوايا المجسمة في أبعاد عشوائية

The solid angle subtended by the complete (d − 1)-dimensional spherical surface of the unit sphere in d-dimensional Euclidean space can be defined in any number of dimensions d. One often needs this solid angle factor in calculations with spherical symmetry. It is given by the formula

where Γ is the gamma function. When d is an integer, the gamma function can be computed explicitly.[9] It follows that

This gives the expected results of 4π steradians for the 3D sphere bounded by a surface of area 4πr2 and 2π radians for the 2D circle bounded by a circumference of length 2πr. It also gives the slightly less obvious 2 for the 1D case, in which the origin-centered 1D "sphere" is the interval [ −r, r ] and this is bounded by two limiting points.

The counterpart to the vector formula in arbitrary dimension was derived by Aomoto [10][11] and independently by Ribando.[12] It expresses them as an infinite multivariate Taylor series:

Given d unit vectors defining the angle, let V denote the matrix formed by combining them so the ith column is and Where this series converges, it converges to the solid angle defined by the vectors.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

انظر أيضا

المراجع

- ^ "Archimedes on Spheres and Cylinders". Math Pages. 2015.

- ^ أ ب Mazonka, Oleg (2012). "Solid Angle of Conical Surfaces, Polyhedral Cones, and Intersecting Spherical Caps". arXiv:1205.1396 [math.MG].

- ^ Hopf, Heinz (1940). "Selected Chapters of Geometry" (PDF). ETH Zurich: 1–2.

- ^ Van Oosterom, A; Strackee, J (1983). "The Solid Angle of a Plane Triangle". IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. BME-30 (2): 125–126. doi:10.1109/TBME.1983.325207.

- ^ Eriksson, Folke (1990). "On the measure of solid angles". Math. Mag. 63 (3): 184–187. doi:10.2307/2691141. JSTOR 2691141.

- ^ "L'Huilier's Theorem – from Wolfram MathWorld". Mathworld.wolfram.com. 2015-10-19. Retrieved 2015-10-19.

- ^ "Spherical Excess – from Wolfram MathWorld". Mathworld.wolfram.com. 2015-10-19. Retrieved 2015-10-19.

- ^ "Area of a Latitude-Longitude Rectangle". The Math Forum @ Drexel. 2003.

- ^ Jackson, FM (1993). "Polytopes in Euclidean n-space". Bulletin of the Institute of Mathematics and its Applications. 29 (11/12): 172–174.

- ^ Aomoto, Kazuhiko (1977). "Analytic structure of Schläfli function". Nagoya Math. J. 68: 1–16. doi:10.1017/s0027763000017839.

- ^ Beck, M.; Robins, S.; Sam, S. V. (2010). "Positivity theorems for solid-angle polynomials". Contributions to Algebra and Geometry. 51 (2): 493–507. arXiv:0906.4031. Bibcode:2009arXiv0906.4031B.

- ^ Ribando, Jason M. (2006). "Measuring Solid Angles Beyond Dimension Three". Discrete & Computational Geometry. 36 (3): 479–487. doi:10.1007/s00454-006-1253-4.

للاستزادة

- Jaffey, A. H. (1954). "Solid angle subtended by a circular aperture at point and spread sources: formulas and some tables". Rev. Sci. Instrum. Vol. 25. pp. 349–354. Bibcode:1954RScI...25..349J. doi:10.1063/1.1771061.

- Masket, A. Victor (1957). "Solid angle contour integrals, series, and tables". Rev. Sci. Instrum. Vol. 28, no. 3. p. 191. Bibcode:1957RScI...28..191M. doi:10.1063/1.1746479.

- Naito, Minoru (1957). "A method of calculating the solid angle subtended by a circular aperture". J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. Vol. 12, no. 10. pp. 1122–1129. Bibcode:1957JPSJ...12.1122N. doi:10.1143/JPSJ.12.1122.

- Paxton, F. (1959). "Solid angle calculation for a circular disk". Rev. Sci. Instrum. Vol. 30, no. 4. p. 254. Bibcode:1959RScI...30..254P. doi:10.1063/1.1716590.

- Gardner, R. P.; Carnesale, A. (1969). "The solid angle subtended at a point by a circular disk". Nucl. Instrum. Methods. Vol. 73, no. 2. pp. 228–230. Bibcode:1969NucIM..73..228G. doi:10.1016/0029-554X(69)90214-6.

- Gardner, R. P.; Verghese, K. (1971). "On the solid angle subtended by a circular disk". Nucl. Instrum. Methods. Vol. 93, no. 1. pp. 163–167. Bibcode:1971NucIM..93..163G. doi:10.1016/0029-554X(71)90155-8.

- Asvestas, John S..; Englund, David C. (1994). "Computing the solid angle subtended by a planar figure". Opt. Eng. Vol. 33, no. 12. pp. 4055–4059. Bibcode:1994OptEn..33.4055A. doi:10.1117/12.183402.

- Tryka, Stanislaw (1997). "Angular distribution of the solid angle at a point subtended by a circular disk". Opt. Commun. Vol. 137, no. 4–6. pp. 317–333. Bibcode:1997OptCo.137..317T. doi:10.1016/S0030-4018(96)00789-4.

- Prata, M. J. (2004). "Analytical calculation of the solid angle subtended by a circular disc detector at a point cosine source". Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. A. Vol. 521. p. 576. arXiv:math-ph/0305034. Bibcode:2004NIMPA.521..576P. doi:10.1016/j.nima.2003.10.098.

- Timus, D. M.; Prata, M. J.; Kalla, S. L.; Abbas, M. I.; Oner, F.; Galiano, E. (2007). "Some further analytical results on the solid angle subtended at a point by a circular disk using elliptic integrals". Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. A. Vol. 580. pp. 149–152. Bibcode:2007NIMPA.580..149T. doi:10.1016/j.nima.2007.05.055.

وصلات خارجية

- HCR's Theory of Polygon(solid angle subtended by any polygon) from Academia.edu

- Arthur P. Norton, A Star Atlas, Gall and Inglis, Edinburgh, 1969.

- M. G. Kendall, A Course in the Geometry of N Dimensions, No. 8 of Griffin's Statistical Monographs & Courses, ed. M. G. Kendall, Charles Griffin & Co. Ltd, London, 1961

- Eric W. Weisstein, Solid Angle at MathWorld.