مجمع الأمن القومي Y-12

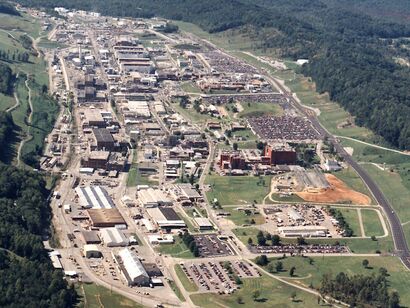

مجمع الأمن القومي Y-12 (إنگليزية: Y-12 National Security Complex)، هو مرفق تابع للإدارة الوطنية للأمن القومي، وزارة الطاقة الأمريكية، يقع في أوك ريدج، تنسي، بالقرب من مختبر اوك ريدج الوطني. بُني المجمع كجزء من مشروع منهاتن من أجل تخصيب اليورانيوم لصنع أول قنبلة نووية. يعتبر الموقع محل ميلاد أول قنبلة نووية.[1] في السنوات التالية للحرب العالمية الثانية، كان يعمل كمصنع لمكونات الأسلحة النووية والأغراض الدفاعية المتعلقة.

المجمع يدار ويشغل بموجب عقد من قبل الأمن النووي الموحد (CNS)، وهو مقاول أمن فدرالي يتكون من شركة بكتل ناشونال، ليدوس، أوربيتال إيه تي كي، داي أند زمنرمان، وبوز ألين هاميلتون كمقاول من الباطن.[2] كما يشغل الأمن النووي الموحد مصنع پانتكس في تكساس.[3]

التاريخ

Y-12 هو الاسم الرمزي فصل النظائر الكهرومغناطيسي في الحرب العالمية الثانية الذي ينتج اليورانيوم المخصب في كلنتون للأعمال الهندسية في أوك ريدج، تنسي، كجزء من مشروع مانهاتن. بدأ البناء في فبراير 1943 تحت إدارة ستون أند وبستر. بسبب النقص في النحاس في زمن الحرب، تم تصنيع الملفات الكهرومغناطيسية الضخمة من 14.700 طن من العملات الفضة من خزائن الحكومة الأمريكية في ويست پوينت.[4][5] التقى الكولونيل كنيث نيكولز مع وكيل وزارة الخزانة دانيال بيل، وطلب ما بين خمسة إلى عشرة آلاف طن من الفضة. كان رد بيل مذهولاً، "كولونيل، في الخزانة لا نتحدث عن أطنان من الفضة؛ وحدتنا هي أونصة ترويسية. وهكذا طلبت مانهاتن الهندسية بالمبلغ وتم إقراضها 395 مليون أونصة تروي من الفضة (13.540 طن قصير، 12300 طن من مستودع ويست پوينت طوال مدة مشروع مانهاتن. تم تعيين حراس ومحاسبين خاصين للفضة، وكانت رعايتهم المسؤولة تعني أنه في نهاية الحرب، فقد أقل من 0.036% من أكثر من 300 مليون دولار من الفضة في هذه العملية، مع إعادة الباقي إلى الخزينة.[6]

بدأت منشأة Y-12 العمل في نوفمبر 1943، بفصل اليورانيوم-235 عن اليورانيوم الطبيعي، والذي يمثل 99.3% من اليورانيوم -238، باستخدام كالوترون لأداء فصل النظائر الكهرومغناطيسي. قامت Y-12 بفصل اليورانيوم 235 لإنتاج قنبلة الولد الصغير النووية التي كانت أسقطت على هيروشيما اليابانية في 6 أغسطس 1945. K-25، منشأة أخرى في أوك ريدج، أنتجت اليورانيوم المخصب باستخدام الانتشار الغازي.

ومع ذلك، لم تبدأ K-25 العمل حتى مارس 1945 ووردت اليورانيوم المخصب قليلاً إلىY-12's Beta Calutrons حيث جاءت الدفعة للحصول على ما يكفي من اليورانيوم 235 لقنبلة الولد الصغير في أوائل صيف 1945. قدم مصنع S-50 للانتشار الحراري في موقع K-25 أيضًا مواد التغذية لـ Y-12's Beta Calutrons.

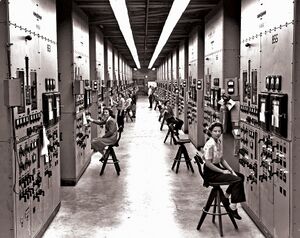

تم تعيين تنسي إيستمان من قبل فيلق المهندسين العسكري لإدارة Y-12 أثناء مشروع مانهاتن. نقلت الشركة العلماء من كنگسپورت، تنسي إلى Y-12 وقامت بتشغيل المصنع من عام 1943 حتى مايو 1947.[7]

قارن نيكولز بيانات إنتاج الوحدة، وأشار إلى الفيزيائي إرنست لورانس أن العاملات الشابات "هيلبيلي" كانت تخرج العلماء الحاصلين على درجة الدكتوراه. وافقوا على سباق الإنتاج وخسر لورانس، وهو رفع معنوي لعمال ومشرفي تنسي إيستمان. تم "تدريب الفتيات على عدم التفكير في السبب مثل الجنود"، بينما "لم يستطع العلماء الامتناع عن التحقيق الذي يستغرق وقتًا طويلاً في سبب التقلبات الطفيفة في الاتصال الهاتفي".[8] أصبحت الشابات اللاتي يعملن بهذه الصفة يعرفن "ببنات كالوترون".[9]

عام 1947 خلفت شركة يونيون كاربيد تنسي إيستمان كمقاول تشغيل، وبقت حتى عام 1984، عندما تخلت يونيون كاربيد عن عقد تشغيل مرافق أوك ريدج التابعة لوزارة الطاقة، وفازت شركة مارتن ماريتا (لوكهيد مارتن لاحقاً) بعقد تولي العملية. نجح BWXT Y-12 (تم تغيير الاسم لاحقًا إلى B&W Y-12) في شركة لوكهيد مارتن كمشغل Y-12 في نوفمبر 2000.[10]

أصاب انفجار كيميائي العديد من العمال في منشأة Y-12 في 8 ديسمبر 1999، عندما تم تنظيف NaK بعد تسريب عرضي، ومعالجته بشكل غير لائق بالزيت المعدني، واشتعلت عن غير قصد عند طلاء سطح أكسيد الپوتاسيوم الفائق تم خدشه بواسطة أداة معدني.[11]

حادث الوضع الحرج 1958

في الساعة الحادية عشر صباح 16 يونيو 1958، وقع حادث الوضع الحرج في الجناح C-1 بالمبنى رقم 9212 بالمرفق، الذي كان في ذلك الوقت تحت إدارة يونيون كاربيد. في الحادث، تم تحويل محلول اليورانيوم عالي التخصيب عن طريق الخطأ إلى أسطوانة فولاذية، مما تسبب في حدوث تفاعل انشطاري لمدة 15-20 دقيقة. نُقل ثمانية عمال إلى المستشفى بسبب الاعتلال أو التعرض للإشعاع من متوسط شديد، لكنهم عادوا جميعًا في النهاية إلى العمل. في يونيو 1960، رفع العمال الثمانية، بيل ويلبورن، أ. س. كولين، تراڤيس روجرز، ر. د. جونز، هوارد ڤاگنر، ت. و. ستينت، پول ماكوري، وبيل كلارك دعوى ضد هيئة الطاقة الذرية. تمت تسوية الدعوى خارج المحكمة. حصل ويلبورن، الذي تلقى أعلى جرعة إشعاع، على 18.000 دولار (حوالي 185.000 دولار عام 2022). تلقى كلارك 9.000 دولار (ما يقرب من 92.500 دولار عام 2022).[12]

في إطار برنامج تعويض موظفي الطاقة عن المرض المهني، تلقى الثمانية لاحقاً تعويضًا إضافيًا من الحكومة؛ جمع كلارك مدفوعات متعددة بلغ مجموعها حوالي 250.000 دولار. تم تشخيص معظم الضحايا الثمانية، إن لم يكن جميعهم، بالسرطان في مرحلة ما من حياتهم.[12]

حريق 2023

صباح 23 فبراير 2023، اندلع حريق بمعالج يورانيوم في مجمع الأمن القومي Y-12 في اوك ريدج بولاية تنسي، مما أدى إلى استجابة طارئة، وفقًا لمتحدث باسم الادارة الوطنية للأمن النووي (NNSA). بدأ الحريق حوالي الساعة 9:15 صباحاً بالتوقيت المحلي في المبنى رقم 9212 بالمنشأة الفيدرالية واقتصر تأثير الحريق على الموقع نفسه. وقال المتحدث باسم إدارة الأمن النووي: "استجابت خدمات الطوارئ للحدث.[13] فعّل الموقع منظمة الاستجابة للطوارئ Y-12 وكنا على اتصال وثيق بالمسؤولين المحليين والدوليين". تم إجلاء ما يقرب من 200 موظف من المبنى ، مع احتساب جميع الموظفين. كما تم إخلاء المباني الأخرى المجاورة للمبنى رقم 9212.

المنشآت والمهام

Y-12's primary missions since the end of the Cold War have been to support defense needs through stockpile stewardship, assist on issues of nuclear non-proliferation, support the Naval Reactors program, and provide expertise to other federal agencies.[14] Y-12 is also responsible for the maintenance and production of all uranium parts and "secondary" mechanisms for every nuclear weapon in the United States arsenal.

Y-12 has a history of providing secure storage of nuclear material for both the United States and other governments. Early efforts focused on securing material from the former Soviet Union;[15] recent activities have included recovery of highly enriched uranium from Chile.[16]

Environmental cleanup has been an ongoing issue for the Department of Energy in Oak Ridge. The Y-12 plant was listed as an EPA Superfund site in the 1990s for groundwater and soil contamination. Today, the Y-12 plant is listed on the DOE's Cleanup Criteria/Decision Document Database (or C2D2 database).[17]

An influx of funding from the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act benefited cleanup efforts by funding demolition and decontamination of aging facilities.[18] These efforts work to further the long-term reduction in the size of the Y-12 facility.[19]

CNS Y-12 currently[when?] employs approximately 4,700 people. About 1,500 additional personnel work onsite as employees of organizations that include UT-Battelle, Science Applications International Corporation, UCOR, and WSI Oak Ridge (an American-controlled unit of G4S Secure Solutions), which holds the security contract for the site. Workers at the site were represented by the Oil, Chemical and Atomic Workers International Union (OCAW).[20]

الاحتجاجات ضد الأسلحة النووية

Since 1988, Oak Ridge Environmental Peace Alliance has organized non-violent direct action protests at the Y-12 Complex, in an effort to close down the weapons plant. Sister Mary Dennis Lentsch, a Catholic nun, has been arrested many times for protesting at the Oak Ridge facility.[21] She has said, "I believe the continuing weapons production at the Y-12 National Security Complex in Oak Ridge, Tennessee, is in direct violation of the treaty obligations of the United States and consequently, is a violation of Article 6 of the U.S. Constitution".[22]

In 2011, the Rev. William J. Bichsel, an 84-year-old priest, received a prison sentence of three months for trespassing on federal property at the Y-12 complex.[23] In 2012, there have been protests about the proposed new Uranium Processing Facility, which is expected to cost $7.5 billion.[24]

In July 2012, Megan Rice, an 82-year-old Catholic sister of the Society of the Holy Child Jesus, and two military veterans who now worked for peace, Gregory Boertje-Obed, and Michael Walli, entered the Y-12 complex. They were all Plowshares activists, and they chose Y-12 because of its crucial role in the production of nuclear weapons. They spray-painted anti-war slogans on the exterior of the Highly Enriched Uranium Materials Facility, a structure for storing weapons-grade uranium.[25] The anti-nuclear activists, who got past fences and disabled security sensors before dawn on July 28, spent several hours in the complex, spray-painted peace messages, and prayed and sang before they were stopped by a guard, who was later joined by another. The security breach prompted private experts to criticize the Department of Energy's safeguarding of nuclear materials. The agency is to reappraise security measures across its nuclear weapons program.[26] The DOE-OIG found that all of the defenses for the plant were insufficient and that the security response had "troubling displays of ineptitude."[27] On May 9, 2013, the three were convicted of sabotage. In her testimony Rice said "I regret I didn't do this 70 years ago."[28]

انظر أيضاً

- المظاهرات المناهضة للطاقة النووية في الولايات المتحدة

- عملية كولكس (فصل النظائر)

- فوگبنك

- K-25

- مختبر اوك ريدج الوطني

- S-50

- قابلية المحطات النووية للهجوم

المراجع

- ^ "A Visit to the Secret Town in Tennessee That Gave Birth to the Atomic Bomb". New Republic (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). Retrieved 2017-11-15.

- ^ "About". CNS – Consolidated Nuclear Security, LLC. Retrieved 2017-09-09.

- ^ "The CNS team – key leadership". Archived from the original on 2014-09-10. Retrieved 2014-09-20.

- ^ Nichols, Kenneth D. (1987). The Road to Trinity. Morrow, New York. p. 42. ISBN 0-688-06910-X.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "Eastman at Oak Ridge - Dr. Howard Young". Archived from the original on 2011-03-18. Retrieved 2017-01-06.

- ^ "14,700 tons of silver at Y-12" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-10-27. Retrieved 2009-12-09.

- ^ {{Cite webMartha Avaleen Egan, |url=https://tennesseeencyclopedia.net/entries/tennessee-eastman-companyeastman-chemical-company/%7C Tennessee Encyclopedia of History and Culture, 2009. Retrieved: February 14, 2013.

- ^ Nichols, Kenneth D. Ibid, page 131

- ^ "A Book Review of The Girls of Atomic City by Denise Kiernan". nationalww2museum.org. National World War II Museum. Retrieved 2021-09-09.

- ^ "Y-12 Receives 'Good' Award Fee Rating from DOE Archived 2007-02-08 at the Wayback Machine," BWX Times, Vol. 2, No. 6 (January 10, 2002). Retrieved: February 14, 2013.

- ^ "Type A Accident Investigation of the December 8, 1999, Multiple Injury Accident Resulting from the Sodium-Potassium Explosion in Building 9201-5 at the Y-12 Plant" (PDF). U.S. Department of Energy. February 2000.

- ^ أ ب Munger, Frank (2014-06-14). "Nuclear survivor: Bill Clark recalls 1958 criticality accident and his up-and-down life since then". Atomic City Underground. also published in Knoxville News Sentinel and Stars and Stripes.

- ^ "Emergency services respond to uranium fire at National Nuclear Security Administration complex in Tennessee". فوكس نيوز. 2023-02-23. Retrieved 2023-02-23.

- ^ Y-12 Mission

- ^ Hoffman, David E. (2009-09-21). "Half a Ton of Uranium -- and a Long Flight". The Washington Post.

- ^ Frank Munger, "Three from Y-12 Helped Secure Chile's HEU Archived يوليو 19, 2010 at the Wayback Machine," Knoxnews.com, April 8, 2010. Retrieved: February 14, 2013.

- ^ Cleanup Criteria / Decision Document Database Archived سبتمبر 23, 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Frank Munger, "Y-12 Stimulus Fund Grows, New Projects May Follow," Knoxville News Sentinel, August 18, 2010. Retrieved: February 14, 2013.

- ^ John Huotari, "Officials Say Uranium Processing Facility Supporters Outnumber Opponents," November 30, 2009. Retrieved: February 14, 2013.

- ^ Bischak, Greg (1989). "Facing the Second Generation of the Nuclear Weapons Complex: Renewal of the Nuclear Production Base or Economic Conversion?". In Dumas, Lloyd J.; Thee, Marek (eds.). Making Peace Possible: The Promise of Economic Conversion. Peace Research Monograph. Vol. 19. Pergamon Press. p. 115. ISBN 0-08-037252X. Retrieved 2022-03-20.

- ^ "Nun sentenced for protesting nuke plant - US news - Crime & courts - NBCNews.com". NBC News. Retrieved 2012-08-28.

- ^ Frank Munger (2010-07-05). "Y-12 protests nets dozens of arrests". Knox News.

- ^ "Rev. Bill Bichsel of Tacoma sentenced to 3 months for Y-12 protest in Tennessee". The News Tribune. Associated Press. 2011-09-13.[dead link]

- ^ Lance Coleman (2012-04-21). "Protesters rally against new Y-12 uranium facility". Knox News.

- ^ Sargent, Carole (2021-02-02). Transform Now Plowshares: Megan Rice, Gregory Boertje-Obed, and Michael Walli. ISBN 9780814637227.

- ^ Matthew L. Wald (2012-08-07). "Security Questions Are Raised by Break-In at a Nuclear Site". New York Times.

- ^ Munger, Frank (2014-02-17). "18 months after security breach, former Y-12 nuclear weapons plant boss tells his story". www.stripes.com. Knoxville News-Sentinel, Tenn. Retrieved 2014-02-17.

- ^ (Rice quote).

وصلات خارجية

- CS1 الإنجليزية الأمريكية-language sources (en-us)

- CS1 maint: location missing publisher

- Articles with dead external links from June 2014

- Pages using gadget WikiMiniAtlas

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Articles containing إنگليزية-language text

- Pages using Lang-xx templates

- Vague or ambiguous time from May 2013

- Coordinates on Wikidata

- البنية التحتية للأسلحة النووية في الولايات المتحدة

- منشآت وزارة الطاقة الأمريكية

- مباني ومنشآت في مقاطعة أندرسون، تنسي

- مباني ومنشآت صناعية فيتنسي

- مرافق فصل النظائر

- اوك ريدج، تنسي

- مواقع مشروع منهاتن

- مرافق فصل النظائر في مشروع منهاتن

- التاريخ العسكري لتنسي

- أبحاث عسكرية للولايات المتحدة

- تأسيسات 1943 في تنسي

- الاحتجاجات المناهضة للطاقة النووية في الولايات المتحدة

- حوادث وأحداث نووية في الولايات المتحدة

- Superfund sites in Tennessee