موراساكي شيكيبو

موراساكي شيكيبو Murasaki Shikibu | |

|---|---|

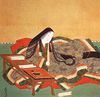

موراساكي شيكيبو، بريشة توسا ميتسوكي (القرن 17) | |

| وُلِد | حوالي 973 كيوتو |

| توفي | حوالي 1014 كيوتو |

| الوظيفة | سيدة بلاط هيان |

| الصنف الأدبي | رواية، شعر |

| الموضوعات | تقاليد البلاط الياباني |

| الأقارب | فوجيوارا نو تامتوكه، الوالد |

موراساكي شيكيبو (باليابانية:紫 式部)(و.(973 - ت. 1025) هي أديبة وشاعرة يابانية، عاشت في أواخر عهد سلالة فوجيوارا الأرستقراطية التي حكمت اليابان نحو ثلاثة قرون (866 - 1160)، وكان زوجها أحد أفرادها.كانت إحدى الوصيفات (من نساء البلاط) أثناء "فترة هيي-آن"، واشتهرت كصاحبة الرواية المشهورة في الأدب الياباني "قصة گنجي" (源氏物語). كتبت هذه القصة قبل أكثر من ألف عام أول رواية نفسية في تاريخ الأدب العالمي، ويعتبرها النقاد من بين أولى الروايات في تاريخ الأدب العالمي.

وهي أشهر كتَّاب الأدب الياباني القديم. تُعدُّ روايتها الطويلة حكاية جَنْجي أبرز الأعمال الروائية اليابانية المبكرة. وتبدأ الرواية بسرد المغامرات العاطفية للأمير گنجي، الأمير المشرق. وهو يمثل الكياسة والحساسية اليابانية الفريدة تجاه الطبيعة.

يزداد الإيقاع حزنًا أثناء تتبع الكتاب للجيلين التاليين من أسرة جنجي. وتسيطر على القصة موضوعات الموت والإحباط في الحب وإحساس بوذي يوصي بعدم ديمومة الإنسان.

تعاملت السيدة موراساكي ببراعة شديدة مع هذا العدد الكبير من الشخصيات في هذه الرواية المعقدة. وشكلتها بطريقة نفسية واقعية لم تظهر في الأدب الغربي إلا بعد عدة قرون. ونشرت ترجمة إنجليزية لقصة گنجي من ستة مجلدات في الفترة ما بين عامي 1925م - 1933م، وترجمها الأديب البريطاني آرثر ويلي.

كانت السيدة موراساكي واحدة من عدة كاتبات موهوبات عملن وصيفات للإمبراطورات خلال القرن الحادي عشر الميلادي. وبالإضافة إلى حكاية جنجي، كتبت أيضًا قصائد شعرية ومذكرات شخصية اشتهرت بوصفها الذكي والجميل لمن عاصروها.

حياتها

لا يُعرف كثير عن تفاصيل حياتها، ولا حتى اسمها الحقيقي، فاسمها الأول شيكيبو يشير إلى مهنة والدها الذي كان مدير المراسم في البلاط، ولقبها موراساكي أي (الليلكية) يشير إلى إحدى بطلات روايتها وإلى أحد معاني اسم زوجها فوجيوارا، ولاسيما أنها تنتمي إلى أحد الفروع الأقل شهرة وشأناً في هذه الأسرة. كان والدها تماتوكي فوجيوارا Tamatoki Fujiwara شاعراً وموظفاً كبيراً، وكذلك كان جدها. عندما توفيت والدتها أبقاها والدها في عهدته، ولم يُلحقها بعائلة والدتها حسب التقاليد المتبعة حينذاك، فتلقت بإشراف من والدها تعليم الفتيان في اللغتين الصينية واليابانية وفي كلاسيكيات الأدب البوذي. ولسرعة استيعابها وذكائها تمنى والدها لو كانت فتى.

الزواج

Aristocratic Heian women lived restricted and secluded lives, allowed to speak to men only when they were close relatives or household members. Murasaki's autobiographical poetry shows that she socialized with women but had limited contact with men other than her father and brother; she often exchanged poetry with women but never with men.[1] Unlike most noblewomen of her status, however, she did not marry on reaching puberty; instead she stayed in her father's household until her mid-twenties or perhaps even to her early thirties.[1][2]

In 996 when her father was posted to a four-year governorship in Echizen Province (modern Fukui prefecture), Murasaki went with him, although it was uncommon for a noblewoman of the period to travel such a distance that could take as long as five days.[3] She returned to Kyoto, probably in 998, to marry her father's friend Fujiwara no Nobutaka, a much older second cousin.[4][1] Descended from the same branch of the Fujiwara clan, he was a court functionary and bureaucrat at the Ministry of Ceremonials, with a reputation for dressing extravagantly and as a talented dancer.[3] In his late forties at the time of their marriage, he had multiple households with an unknown number of wives and offspring.[5] Gregarious and well-known at court, he was involved in numerous romantic relationships that may have continued after his marriage to Murasaki.[1] As was customary, she would have remained in her father's household where her husband would have visited her.[5] Nobutaka had been granted more than one governorship, and by the time of his marriage to Murasaki he was probably quite wealthy. Interpretations of their marital relationship differ among scholars: Richard Bowring suggests a harmonious marriage, while Japanese literature scholar Haruo Shirane finds evidence of resentment towards her husband in Murasaki’s poems.[4][1]

The couple's daughter, Kenshi (Kataiko), was born in 999. Two years later Nobutaka died during a cholera epidemic.[1] As a married woman Murasaki would have had servants to run the household and care for her daughter, giving her ample leisure time. She enjoyed reading and had access to romances (monogatari) such as The Tale of the Bamboo Cutter and The Tales of Ise.[3] Scholars believe she may have started writing The Tale of Genji before her husband's death; it is known she was writing after she was widowed, perhaps in a state of grief.[6][4] In her diary she describes her feelings after her husband's death: "I felt depressed and confused. For some years I had existed from day to day in listless fashion ... doing little more than registering the passage of time ... The thought of my continuing loneliness was quite unbearable".[7]

According to legend, Murasaki retreated to Ishiyama-dera at Lake Biwa, where she was inspired to write The Tale of Genji on an August night while looking at the Moon. Although scholars dismiss the factual basis of the story of her retreat, Japanese artists often depicted her at Ishiyama Temple staring at the Moon for inspiration.[8] She may have been commissioned to write the story and may have known an exiled courtier in a similar position to her hero Prince Genji.[9] Murasaki would have distributed newly written chapters of Genji to friends who in turn would have re-copied them and passed them on. By this practice the story became known and she gained a reputation as an author.[10]

تزوجت موراساكي وهي في العشرين من عمرها، ولكن سرعان ما توفي زوجها، فاعتزلت الحياة العامة لتربية ابنتها حتى عام 1004، وحين عُيِّن والدها حاكماً على إقليم إتْشيزِن النائي عن موطنها في العاصمة كيوتو ، رتَّب أمورها بحيث تدخل وصيفةً في خدمة الامبراطورة الشابة أكيكو زوجة الامبراطور إيتشيگو. ومنذ عام 1008 بدأت موراساكي بتدوين يومياتها حول حياة البلاط على جميع الصعد، حتى عام 1011 حين توفي الامبراطور واعتزلت زوجته الحياة العامة مع وصيفاتها. وعندما صار والدها - عام 1012 - حاكم إقليم إتشيگو التحقت موراساكي به مع ابنتها؛ إلى أن أدار ظهره للحياة ودخل الدير البوذي معتكفاً. ولا يُعرف أي شيء عن موراساكي فيما تبقى من حياتها حتى وفاتها في كيوتو. ويرجح بعض الباحثين أن وفاتها كانت في عام 1031 وليس في عام 1014 أو 1016 أو 1025 حسبما ورد في مراجع مختلفة.

حياة البلاط

Heian culture and court life reached a peak early in the 11th century.[11] The population of Kyoto grew to around 100,000 as the nobility became increasingly isolated at the Heian Palace in government posts and court service.[12] Courtiers became overly refined with little to do, insulated from reality, preoccupied with the minutiae of court life, turning to artistic endeavors.[11][12] Emotions were commonly expressed through the artistic use of textiles, fragrances, calligraphy, colored paper, poetry, and layering of clothing in pleasing color combinations—according to mood and season. Those who showed an inability to follow conventional aesthetics quickly lost popularity, particularly at court.[13] Popular pastimes for Heian noblewomen—who adhered to rigid fashions of floor-length hair, whitened skin and blackened teeth—included having love affairs, writing poetry and keeping diaries. The literature that Heian court women wrote is recognized as some of the earliest and among the best literature written in Japanese canon.[11][12]

البلاطات المتنافسة والشاعرات

When in 995 Michinaga's two brothers Fujiwara no Michitaka and Fujiwara no Michikane died, leaving the regency vacant, Michinaga quickly won a power struggle against his nephew Fujiwara no Korechika (brother to Teishi, Emperor Ichijō's wife), and, aided by his sister Senshi, he assumed power. Teishi had supported her brother Korechika, who was discredited and banished from court in 996 following a scandal involving his shooting at the retired Emperor Kazan, causing her to lose power.[14] Four years later Michinaga sent Shōshi, his eldest daughter, to Emperor Ichijō's harem when she was about 12.[15] A year after placing Shōshi in the imperial harem, in an effort to undermine Teishi's influence and increase Shōshi's standing, Michinaga had her named Empress although Teishi already held the title. As historian Donald Shively explains, "Michinaga shocked even his admirers by arranging for the unprecedented appointment of Teishi (or Sadako) and Shōshi as concurrent empresses of the same emperor, Teishi holding the usual title of "Lustrous Heir-bearer" kōgō and Shōshi that of "Inner Palatine" (chūgū), a toponymically derived equivalent coined for the occasion".[14] About five years later, Michinaga brought Murasaki to Shōshi's court, in a position that Bowring describes as a companion-tutor.[16]

Women of high status lived in seclusion at court and, through strategic marriages, were used to gain political power for their families. In the case of Shōshi and other such marriages to members of the imperial clan, it enabled the woman's clan to exercise influence over the emperor—this was how Michinaga, and other Fujiwara Regents, achieved their power. Despite their seclusion, some women wielded considerable influence, often achieved through competitive salons, dependent on the quality of those attending.[17] Ichijō's mother and Michinaga's sister, Senshi, had an influential salon, and Michinaga probably wanted Shōshi to surround herself with skilled women such as Murasaki to build a rival salon.[10]

Shōshi was 16 to 19 when Murasaki joined her court,[18] either in 1005 or 1006.[19] According to Arthur Waley, Shōshi was a serious-minded young lady, whose living arrangements were divided between her father's household and her court at the Imperial Palace.[20] She gathered around her talented women writers such as Izumi Shikibu and Akazome Emon—the author of an early vernacular history, The Tale of Flowering Fortunes.[21] The rivalry that existed among the women is evident in Murasaki's diary, where she wrote disparagingly of Izumi: "Izumi Shikibu is an amusing letter-writer; but there is something not very satisfactory about her. She has a gift for dashing off informal compositions in a careless running-hand; but in poetry she needs either an interesting subject or some classic model to imitate. Indeed it does not seem to me that in herself she is really a poet at all."[22]

Sei Shōnagon, author of The Pillow Book, had been in service as lady-in-waiting to Teishi when Shōshi came to court; it is possible that Murasaki was invited to Shōshi's court as a rival to Shōnagon. Teishi died in 1001, before Murasaki entered service with Shōshi, so the two writers were not there concurrently, but Murasaki, who wrote about Shōnagon in her diary, certainly knew of her, and to an extent was influenced by her.[23] Shōnagon's The Pillow Book may have been commissioned as a type of propaganda to highlight Teishi's court, known for its educated ladies-in-waiting. Japanese literature scholar Joshua Mostow believes Michinaga provided Murasaki to Shōshi as an equally or better educated woman, so as to showcase Shōshi's court in a similar manner.[24]

The two writers had different temperaments: Shōnagon was witty, clever, and outspoken; Murasaki was withdrawn and sensitive. Entries in Murasaki's diary show that the two may not have been on good terms. Murasaki wrote, "Sei Shōnagon ... was dreadfully conceited. She thought herself so clever, littered her writing with Chinese characters, [which] left a great deal to be desired."[25] Keene thinks that Murasaki's impression of Shōnagon could have been influenced by Shōshi and the women at her court, as Shōnagon served Shōshi's rival empress. Furthermore, he believes Murasaki was brought to court to write Genji in response to Shōnagon's popular Pillow Book.[23] Murasaki contrasted herself to Shōnagon in a variety of ways. She denigrated the pillow book genre and, unlike Shōnagon, who flaunted her knowledge of Chinese, Murasaki pretended to not know the language, regarding it as pretentious and affected.[24]

"سيدة التأريخ"

Although the popularity of the Chinese language diminished in the late Heian era, Chinese ballads continued to be popular, including those written by Bai Juyi. Murasaki taught Chinese to Shōshi who was interested in Chinese art and Juyi's ballads. Upon becoming Empress, Shōshi installed screens decorated with Chinese script, causing outrage because written Chinese was considered the language of men, far removed from the women's quarters.[26] The study of Chinese was thought to be unladylike and went against the notion that only men should have access to the literature. Women were supposed to read and write only in Japanese, which separated them through language from government and the power structure. Murasaki, with her unconventional classical Chinese education, was one of the few women available to teach Shōshi classical Chinese.[27] Bowring writes it was "almost subversive" that Murasaki knew Chinese and taught the language to Shōshi.[28] Murasaki, who was reticent about her Chinese education, held the lessons between the two women in secret, writing in her diary, "Since last summer ... very secretly, in odd moments when there happened to be no one about, I have been reading with Her Majesty ... There has of course been no question of formal lessons ... I have thought it best to say nothing about the matter to anybody."[29]

Murasaki probably earned an ambiguous nickname, "The Lady of the Chronicles" (Nihongi no tsubone), for teaching Shōshi Chinese literature.[10] A lady-in-waiting who disliked Murasaki accused her of flaunting her knowledge of Chinese and began calling her "The Lady of the Chronicles"—an allusion to the classic Chronicles of Japan—after an incident in which chapters from Genji were read aloud to the Emperor and his courtiers, one of whom remarked that the author showed a high level of education. Murasaki wrote in her diary, "How utterly ridiculous! Would I, who hesitate to reveal my learning to my women at home, ever think of doing so at court?"[30] Although the nickname was apparently meant to be disparaging, Mulhern believes Murasaki was flattered by it.[10]

The attitude toward the Chinese language was contradictory. In Teishi's court, the Chinese language had been flaunted and considered a symbol of imperial rule and superiority. Yet, in Shōshi's salon there was a great deal of hostility towards the language—perhaps owing to political expedience during a period when Chinese began to be rejected in favor of Japanese—even though Shōshi herself was a student of the language. The hostility may have affected Murasaki and her opinion of the court, and forced her to hide her knowledge of Chinese. Unlike Shōnagon, who was both ostentatious and flirtatious, as well as outspoken about her knowledge of Chinese, Murasaki seems to have been humble, an attitude which possibly impressed Michinaga. Although Murasaki used Chinese and incorporated it in her writing, she publicly rejected the language, a commendable attitude during a period of burgeoning Japanese culture.[31]

Murasaki seems to have been unhappy with court life and was withdrawn and somber. No surviving records show that she entered poetry competitions; she appears to have exchanged few poems or letters with other women during her service.[4] In general, unlike Shōnagon, Murasaki gives the impression in her diary that she disliked court life, the other ladies-in-waiting, and the drunken revelry. She did, however, become close friends with a lady-in-waiting named Lady Saishō, and she wrote of the winters that she enjoyed, "I love to see the snow here".[32][33]

According to Waley, Murasaki may not have been unhappy with court life in general but bored in Shōshi's court. He speculates she would have preferred to serve with the Lady Senshi, whose household seems to have been less strict and more light-hearted. In her diary, Murasaki wrote about Shōshi's court, "[she] has gathered round her a number of very worthy young ladies ... Her Majesty is beginning to acquire more experience of life, and no longer judges others by the same rigid standards as before; but meanwhile her Court has gained a reputation for extreme dullness".[34]

Murasaki disliked the men at court, whom she thought were drunken and stupid. However, some scholars, such as Waley, are certain she was involved romantically with Michinaga. At the least, Michinaga pursued her and pressured her strongly, and her flirtation with him is recorded in her diary as late as 1010. Yet, she wrote to him in a poem, "You have neither read my book, nor won my love."[35] In her diary she records having to avoid advances from Michinaga—one night he sneaked into her room, stealing a newly written chapter of Genji.[36] However, Michinaga's patronage was essential if she was to continue writing.[37] Murasaki described her daughter's court activities: the lavish ceremonies, the complicated courtships, the "complexities of the marriage system",[2] and in elaborate detail, the birth of Shōshi's two sons.[36]

It is likely that Murasaki enjoyed writing in solitude.[36] She believed she did not fit well with the general atmosphere of the court, writing of herself: "I am wrapped up in the study of ancient stories ... living all the time in a poetical world of my own scarcely realizing the existence of other people .... But when they get to know me, they find to their extreme surprise that I am kind and gentle".[38] Inge says that she was too outspoken to make friends at court, and Mulhern thinks Murasaki's court life was comparatively quiet compared to other court poets.[39][10] Mulhern speculates that her remarks about Izumi were not so much directed at Izumi's poetry but at her behavior, lack of morality and her court liaisons, of which Murasaki disapproved.[21]

Rank was important in Heian court society and Murasaki would not have felt herself to have much, if anything, in common with the higher ranked and more powerful Fujiwaras.[40] In her diary, she wrote of her life at court: "I realized that my branch of the family was a very humble one; but the thought seldom troubled me, and I was in those days far indeed from the painful consciousness of inferiority which makes life at Court a continual torment to me."[41] A court position would have increased her social standing, but more importantly she gained a greater experience to write about.[10] Court life, as she experienced it, is well reflected in the chapters of Genji written after she joined Shōshi. The name Murasaki was most probably given to her at a court dinner in an incident she recorded in her diary: in 1008 the well-known court poet Fujiwara no Kintō inquired after the "Young Murasaki"—an allusion to the character named Murasaki in Genji—which would have been considered a compliment from a male court poet to a female author.[10]

حكاية گنجي

مقالة مفصلة: حكاية گنجي

مقالة مفصلة: حكاية گنجي

استغرقت موراساكي عشر سنوات - ما بين عامي 1001 و1010 - في كتابة روايتها الهائلة الحجم والمؤلَّفة من أربعة وخمسين فصلاً، سردت فيها بأسلوب رشيق؛ جذاب وغني بالإيحاءات تفاصيل حياة الأمير گنجي المليئة بالغراميات، واستمرارها عبر ابنه المزعوم كاورو وحفيده المزعوم أيضاً نيوو، على خلفية من الأحداث اليومية أو الاحتفالية البلاطية، الموصوفة بواقعية لافتة. وعلى الرغم من ذلك وجد بعض النقاد أن الفوارق في البنية المجتمعية اليابانية وصراعاتها ومعاناتها كانت في واقع الحال آنئذٍ، أكثر تبايناً وأشد قسوة مما صورته موراساكي في روايتها، ولذا فإن واقعيتها تنتمي إلى الخيال المثالي ولا تصدر عن الواقع الملموس، علماً أن الكاتبة كانت على اطّلاع واسع وعميق على حقيقة أوضاع الحياة في عصرها. ويمكن من سياق السرد تمييز ثلاثة خطوط رئيسية للأحداث وشخصياتها، فالفصول (1- 33) ترتبط بأزهى سنوات گنجي في كيوتو أما في الفصول (34-41) فلم يعد الأمير محرِّك الأحداث ومحورها، بل غرق في كآبة سوداوية واعتكف عن الناس؛ وبطل الفصول (42-54) في قرية أوجي Uji هو الابن المزعوم (الامبراطور الجديد) كاورو، في صراعه مع الحفيد المزعوم نيوو حول معشوقة واحدة. وفي خضم هذه الفصول المتلاحقة الأحداث تحرِّك موراساكي نحو أربعمئة شخصية بدقة وعناية متناهية، معتمدة في أغلب الحالات على تحليل نفسية الشخصية الرئيسية أو الثانوية بغرض تفسير سلوكها ودوافعها. وهكذا تتجلى شخصية الأمير غنجي الذي كان متولِّعاً بأمه التي ماتت عنه باكراً، فصار يبحث في معشوقاته منذ يفاعته عن صورة أمه، من دون جدوى. ونتيجة لعلاقته العابرة بزوجة أبيه الامبراطور، تنجب هذه ابنها الوحيد كاورو، الذي يرسّمه الامبراطور ولياً للعهد، من دون أن يدري أحد بحقيقة الحال سوى الأم. ثم يلتقي غنجي بالصبية الفتية موراساكي ابنة أخت زوجة الامبراطور، فيعجب بها ويقرر الإشراف على تربيتها لتصير لاحقاً زوجته. لكن مغامراته لا تقف عند حد، وعندما يقترب من إحدى عشيقات الامبراطور، يفضحه أعداؤه وحساده مما يؤدي إلى نفيه إلى أوجي، حيث ينتج من علاقته بشابة محلية الابن نيوو، الذي يُعرف بالحفيد، بسبب فارق السن ومراعاةً للسمعة. وعلى أثر تنصيب كاورو امبراطوراً، وقد عَرَف حقيقة أصله، يستعيد غنجي حظوته في البلاط ويخسر في الوقت نفسه حظه وسعادته. فالزوجة المنتظرة موراساكي الجميلة الوفية، تنقاد لشهوةٍ عابرة فتنجب ابناً غير شرعي وتموت، مما يصدم گنجي ويؤدي إلى اعتكافه الحياة حتى وفاته، غير آبه بما يجري بين أبنائه.».[42]

جدل

تعرضت الرواية نقداً في القرن العشرين للتشكيك بمصداقية نسبتها إلى شيكيبو موراساكي، فرأى بعض الباحثين أن أباها هو الذي وضع المخطط العام للرواية وترك لها أن تملأها بالتفاصيل، ورأى آخرون أن الفضل الأول يعود إلى رجل الدولة الشهير والشاعر ميتشيناگا فوجيوارا Michinaga الذي كان أقرب المقربين من العائلة. كما تكهن بعضهم بأن ابنتها دايني نو سانمي Daini No Sanmi هي مؤلفة الفصول العشرة الأخيرة. ورأى الباحث أوياما أتسوكو Oyama Atsuko أن الرواية لاتعدو أن تكون معالجة أدبية موسعة لسيرة الحياة التاريخية للأمير ميناموتو نو تكاكيرا Minamoto no Takaakira ت (914-982). وعلى الرغم من جميع هذه التكهنات أو المزاعم تبقى الرواية متميزة في عصرها بأمور عدة، أولها عدم ظهور كائنات إلهية أو خارقة في سياق الأحداث، وثانيها المعالجة النفسية المعقدة لبنية الشخصيات الرئيسية والثانوية على حد سواء، وثالثها تشابك الأحداث من دون تعقيدٍ مبهم، وآخرها جمال اللغة وطواعيتها للتعبير عن مختلف الحالات والشخصيات.

في أربعينيات القرن الحادي عشر أبدى آل فوجيوارا اهتماماً خاصاً بإرث قريبتهم موراساكي فنشروا روايتها، ثم جمعوا قصائدها المهمة التي بلغ عددها 128 قصيدة ونشروها، كما نشروا أيضاً يوميات شيكيبو موراساكي عن حياتها في البلاط الامبراطوري.

انظر أيضاً

المصادر

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةShirane218 - ^ أ ب Knapp, Bettina. "Lady Murasaki's The Tale of the Genji". Symposium. (1992). (46).

- ^ أ ب ت Mulhern (1991), 83–85

- ^ أ ب ت ث خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةBowring, 2004, 4 - ^ أ ب خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةM257ff - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةShiraneB293 - ^ qtd in Mulhern (1991), 84

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةP50ff - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةRoyall - ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ Mulhern (1994), 258–259

- ^ أ ب ت Henshall (1999), 24–25

- ^ أ ب ت Lockard (2008), 292

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةPerez21ff - ^ أ ب Shively and McCullough (1999), 67–69

- ^ McCullough (1990), 201

- ^ Bowring (1996), xiv

- ^ Bowring (1996), xv–xvii

- ^ According to Mulhern Shōshi was 19 when Murasaki arrived; Waley states she was 16. See Mulhern (1994), 259 and Waley (1960), vii

- ^ Bowring (1996), xxxv

- ^ Waley (1960), vii

- ^ أ ب Mulhern (1994), 156

- ^ Waley (1960), xii

- ^ أ ب Keene (1999), 414–415

- ^ أ ب Mostow (2001), 130

- ^ qtd in Keene (1999), 414

- ^ Adolphson (2007), 110, 119

- ^ Adolphson (2007), 110

- ^ Bowring (2004), 11

- ^ qtd in Waley (1960), ix–x

- ^ qtd in Mostow (2001), 133

- ^ Mostow (2001), 131, 137

- ^ Waley (1960), xiii

- ^ Waley (1960), xi

- ^ Waley (1960), viii

- ^ Waley (1960), x

- ^ أ ب ت Mulhern (1994), 260–261

- ^ Shirane (1987), 221–222

- ^ Waley (1960), xv

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةInge9 - ^ Bowring (2004), 3

- ^ Waley (1960), xiv

- ^ نبيل الحفار. "موراساكي (شيكيبو ـ)(نحو 975م ـ نحو 1025م)". الموسوعة العربية. Retrieved 2013-04-03.

وصلات خارجية

| مراجع مكتبية عن موراساكي شيكيبو |

| By موراساكي شيكيبو |

|---|

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Missing redirects

- Pages using multiple image with auto scaled images

- مواليد 973

- وفيات القرن 11

- شعراء يابانيون

- كتاب يوميات يابانيون

- روائيون يابانيون

- كاتبات يابانيات

- قصة گنجي

- نساء في القرون الوسطى اليابانية

- كاتبات القرن 11

- أسرة فوجيوارا

- أشخاص في فترة هيان اليابانية

- Ladies-in-waiting

- أدباء يابانيون