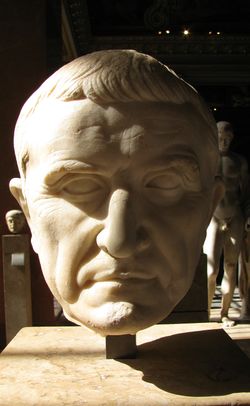

ماركوس ليكينيوس كراسوس

ماركوس ليكينيوس كراسوس Marcus Licinius Crassus | |

|---|---|

| |

| وُلِدَ | 115 ق.م. |

| توفي | 53 ق.م. |

| المهنة | سياسي وقائد عسكري |

ماركوس ليكينيوس كراسوس (لاتينية: M·LICINIVS·P·F·P·N·CRASSVS[1]) (ح. 115 ق.م. - 53 ق.م.) كان جنرالاً رومانياً وسياسياً قاد نصر سولا الحاسم في معركة البوابة الكولينية، وأخمد ثورة العبيد التي قادها سپارتاكوس ودخل في حلف سري، سـُمـِّي الثلاثية الأولى، مع گنايوس پومپيوس ماگنس وگايوس يوليوس قيصر. ويـُزعم أنه كان يملك ما يربو على 200,000,000 سسترتيوس في قمة ثروته. فكان أحد أغنى الرجال في عصره ومازال يـُعد ضمن أغنى عشر رجال في قائمة أغنى شخصيات تاريخية، إلا أن كراسوس كان يتشوق لأن يـُعرف بانتصاراته العسكرية في صيغة موكب نصر روماني. هذه الرغبة في الانتصار قادته إلى سوريا، حيث هـُزم ولقي مصرعه في في هزيمة الرومان في حران على يد السپاهبد الپارثي سورنا.

إلا أن أهمية كراسوس في تاريخ العالم تنبع من دعمه المالي والسياسي للشاب الفقير يوليوس قيصر، الأمر الذي مكن قيصر من بدء مستقبله السياسي.

كوَّن كراسوس مع كل من قيصر وبومبي، المجلس الحاكم الثلاثى عام 60 ق.م. ومن قبل، تقلد كراسوس المناصب الحكومية العليا المتمثلة في منصب القاضي والقنصل والرقيب. وأُطلق عليه لقب الثري لأنه كون ثروة طائلة من خلال الاستثمارات العقارية، وقد استغل منصبه في كسب التأييد لأصدقائه في الأعمال التجارية. وفي عام 71 ق.م.، سحق كراسوس ثورة سبارتاكوس. وفي سعيه من أجل تحقيق المجد العسكري، شن حرباً ضد بارثيا، إحدى المناطق في آسيا الوسطى. وفي عام 53 ق.م.، حاصر رماة السهام في بارثيا جيشه وقتلوه ومعظم جنوده.

وفي عام 55 ق.م.، أصبح قنصلاً مرة أخرى مع پومپي، وصدر قانون يمنح مقاطعتي هسپانيا لپومپي وسوريا لكراسوس لمدة خمس سنوات.

كراسوس حاكما على سوريا ومصرعه

Crassus received Syria as his province, which promised to be an inexhaustible source of wealth. It would have been had he not also sought military glory and crossed the Euphrates in an attempt to conquer Parthia. Crassus was reportedly the richest man in the world at his time, and attacked Parthia not only because of its great wealth, but because of a desire to match the military exploits of his two major rivals, Pompey the Great and Julius Caesar, and indeed those of Alexander the Great. The king of Armenia, Artavazd II, offered Crassus the aid of nearly fifty-thousand troops on the condition that Crassus invaded through Armenia so that the king could provide for his troops.[2] Crassus refused, and invaded across the Euphrates. His legions were defeated at Carrhae (modern Harran in Turkey) in 53 BC by a numerically inferior Parthian force composed mainly of armoured heavy cavalry and horse archers. Crassus' legions were unable to maneuver as swiftly as their opponents. Crassus refused his quaestor Gaius Cassius Longinus's plans to reconstitute the Roman battle line, and remained in the testudo formation. Subsequently Crassus' men, being near mutiny, demanded he parley with the Parthians, who had offered to meet with him. Crassus, despondent at the death of his son Publius in the battle, finally agreed to meet the Parthian general. Upon his arrival in the Parthian camp he was seized and killed by being forced to drink a cup of melted gold as a symbol of his thirst for riches.

The account given in Plutarch's biography of Crassus also mentions that, during the feasting and revelry in the wedding ceremony of Artavazd's son and Orodes II's sister in Artashat, Crassus' head was brought to the king, whereupon a certain actor of the royal court named Jason of Tralles took the head, and sang the following verses (from Euripides's Bacchae): "We bring from the mountain/A tendril fresh-cut to the palace/A wonderful prey."[3]

أسرى جيش كراسوس في أيدي الپارثيين

For centuries a legend has persisted that Crassus's legion, defeated by the Parthians, did not all suffer the fate of death, which raised the questions of what did happen to them. In February, 2007, scientists visited the Chinese village of Liqian, near to the Gobi Desert, where it has been suggested that the residents are descendants of Roman Legionaries. The scientists found a number of people there who have blonde hair, green or blue eyes, and noses uncharacteristic of Chinese features. Stories first became public in the 1950s, when Oxford University Professor Homer Dubs pieced together stories that the village was founded by Roman Legionaries following their defeat in battle. According to the legends, some 145 Legionaries survived the battle, and for years wandered the region, eventually intermingling with the locals. Professor Dubs claimed that the Legionaries had survived the battle, and possibly fearing retribution for their defeat, made their way eastward, working as a mercenary group, both fighting for and training militaries in the region.

Seventeen years after the defeat of Crassus's forces by the Parthians, a detachment of troops, which was allegedly utilizing the Roman Testudo formation (tortoise), was said to have been captured by Chinese forces.[4] This allegedly occurred when a Chinese Army of the Han Dynasty, led by General Chen Tang, won a victory at the Battle of Zhizhi in 36 BC. During that battle, they encountered troops of European appearance fighting on the side of Zhizhi Chanyu, their opposition, according to a Chinese historian named Ban Gu, who lived during that time. The Chinese took these soldiers prisoner, but were so impressed by their fighting abilities that they incorporated them into their army to defend the province of Gansu, calling them Li-Jien, which when pronounced sounds like legion. In excavations of the area, Roman coins have been found, as well as one helmet with the engraving, written in Chinese, saying "one of the prisoners". It should be noted, however, that the artifacts are found in a village along the Silk Road, so their discovery is unsurprising.[5]

Scientists had taken DNA samples in the hopes that they can determine if the people in the village did descend from European ancestry. However, they have pointed out that there is little way of knowing whether the ancestors would have in fact been from Crassus's legion. Although they can confirm the DNA as being of European origins, narrowing that down to it being from Crassus's legion is not likely without some concrete supporting evidence.[6] The results of the DNA test does not support the hypothesis that the inhabitants of Liqian are related to the Romans.[7]

تأريخ

- 115 BC - Crassus born, the second of three sons of P. Licinius Crassus (cos.97, cens.89)

- 97 BC - Father is Consul of Rome

- 87 BC - Crassus flees to Hispania from Marian forces

- 84 BC - Joins Sulla against Marians

- 82 BC - Commanded the victorious right wing of Sulla's army at the Colline Gate, the decisive battle of the civil war, fought Kalends of November

- 78 BC - Sulla died in the spring

- 73 BC - Revolt of Spartacus, probable year Crassus was praetor (75, 74, 73 all possible)

- 72 BC - Crassus given special command of the war against Spartacus following the ignominious defeats of both consuls

- 71 BC - Crassus destroys the remaining slave armies in the spring, elected consul in the summer

- 70 BC - Consulship of Crassus and Pompey

- 65 BC - Crassus Censor with Quintus Lutatius Catulus

- 63 BC - Catiline Conspiracy

- 59 BC - First Triumvirate formed. Caesar is Consul

- 56 BC - Conference at Luca

- 55 BC - Second consulship of Crassus and Pompey. In November, Crassus leaves for Syria

- 54 BC - Campaign against the Parthians

- 53 BC - Crassus dies in the Battle of Carrhae

الهامش

- ^ بالإنجليزية: "Marcus Licinius Crassus, son of Publius, grandson of Publius"

- ^ Armenia: cradle of civilization By David Marshall Lang, Allen & Unwin (1970)

- ^ Plutarch. Life of Crassus. 33.2-3.

- ^ [1]

- ^ [2] [3]

- ^ [4]

- ^ Zhou R, An L, Wang X, Shao W, Lin G, Yu W, Yi L, Xu S, Xu J, Xie X, Testing the hypothesis of an ancient Roman soldier origin of the Liqian people in northwest China: a Y-chromosome perspective. J Hum Genet. 2007; 52(7): 584-91.

المراجع

المصادر الرئيسية

أعمال حديثة

- Marshall, B A: Crassus: A Political Biography (Adolf M Hakkert, Amsterdam, 1976)

- Ward, Allen Mason: Marcus Crassus and the Late Roman Republic (University of Missouri Press, 1977)

- Twyman, Briggs L: critical review of Marshall 1976 and Ward 1977, Classical Philology 74 (1979), 356-61

- Hennessy, Dianne. (1990). Studies in Ancient Rome. Thomas Nelson Australia. ISBN 0-17-007413-7.

- Holland, Tom. (2003). Rubicon: The Triumph and Tragedy of the Roman Republic. Little,Brown.

- Sampson, Gareth C: The defeat of Rome: Crassus, Carrhae & the invasion of the east (Pen & Sword Books, 2008) ISBN 978-1-844156-764.

- Marcus Licinius Crassus

- Lang, David Marshall: Armenia: cradle of civilization (Allen & Unwin, 1970)

وصلات خارجية

- Crassus entry in historical sourcebook by Mahlon H. Smith

| سبقه Publius Cornelius Lentulus Sura and Gnaeus Aufidius Orestes |

Consul of the Roman Republic with Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus 70 BC |

تبعه Quintus Caecilius Metellus Creticus and Quintus Hortensius |

| سبقه Gnaeus Cornelius Lentulus Marcellinus and Lucius Marcius Philippus |

Consul of the Roman Republic with Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus 55 BC |

تبعه Appius Claudius Pulcher and Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus |

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Missing redirects

- Infobox person using certain parameters when dead

- Pages using infobox person with deprecated net worth parameter

- مواليد 115 ق.م.

- وفيات 53 ق.م.

- رومان القرن الأول ق.م.

- جنرالات رومان قدماء

- جنرالات رومان قتلى الوغى

- قناصل جمهوريون رومان

- Roman censors

- شيوخ رومان قدماء

- Licinii Crassi