معركة فرنسا

| Battle of France | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

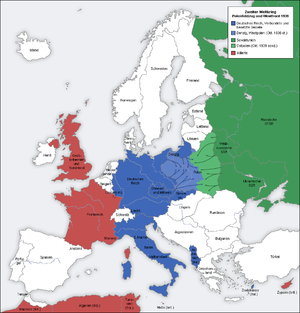

| جزء من the الجبهة الغربية من الحرب العالمية الثانية | |||||||||

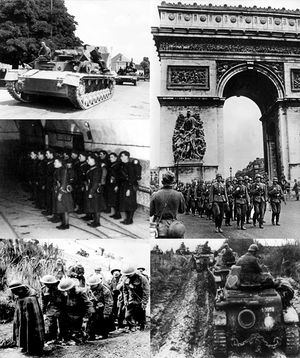

Clockwise from top left: German Panzer IV tanks passing through a town in فرنسا; German soldiers marching past the Arc de Triomphe after the surrender of Paris, 14 June 1940; column of French Renault R35 tanks at Sedan, Ardennes; British and French prisoners at Veules-les-Roses; French soldiers on review within the Maginot Line fortifications. | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| المتحاربون | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| القادة والزعماء | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| الوحدات المشاركة | |||||||||

|

Axis armies

|

Allied armies

| ||||||||

| القوى | |||||||||

|

Germany: 141 divisions 7,378 guns[2] 2,445 tanks[2] 5,638 aircraft[3][ت] 3,350,000 troops Italians in the Alps 22 divisions 3,000 guns 300,000 troops |

Allies: 135 divisions 13,974 guns 3,383–4,071 French tanks[2][4] <2,935 aircraft[3][ث] 3,300,000 troops French in the Alps 5 divisions ~150,000 troops | ||||||||

| الضحايا والخسائر | |||||||||

|

Germany: Total: 185,587 |

376,734 dead, missing and wounded[د] Total: 2,260,000 | ||||||||

معركة فرنسا (فرنسية: bataille de France) (10 May – 25 June 1940), also known as the Western Campaign (Westfeldzug), the French Campaign (ألمانية: Frankreichfeldzug, campagne de France) and the Fall of France، حملة شنتها قوات دول المحور ألمانيا و إيطاليا على قوات دول الحلفاء فرنسا و بريطانيا وهولندا وبلجيكا و لوكسمبورغ في الحرب العالمية الثانية ما بين 10 مايو إلى 25 يونيو عام 1940، وانتهت بهزيمة الحلفاء واحتلال فرنسا والدول المنخفضة. On 3 September 1939, France declared war on Germany following the German invasion of Poland. In early September 1939, France began the limited Saar Offensive and by mid-October had withdrawn to their start lines. German armies invaded Belgium, Luxembourg and the Netherlands on 10 May 1940. Italy entered the war on 10 June 1940 and attempted an invasion of France. France and the Low Countries were conquered, ending land operations on the Western Front until the Normandy landings on 6 June 1944.

In Fall Gelb ("Case Yellow"), German armoured units made a surprise push through the Ardennes and then along the Somme valley, cutting off and surrounding the Allied units that had advanced into Belgium to meet the German armies there. British, Belgian and French forces were pushed back to the sea by the Germans; the British and French navies evacuated the encircled elements of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) and the French and Belgian armies from Dunkirk in Operation Dynamo.

German forces began Fall Rot ("Case Red") on 5 June 1940. The sixty remaining French divisions and the two British divisions in France made a determined stand on the Somme and Aisne but were defeated by the German combination of air superiority and armoured mobility. German armies outflanked the intact Maginot Line and pushed deep into France, occupying Paris unopposed on 14 June. After the flight of the French government and the collapse of the French Army, German commanders met with French officials on 18 June to negotiate an end to hostilities.

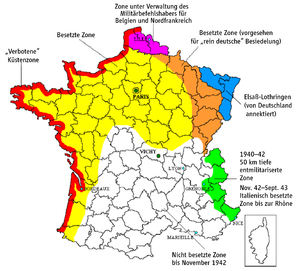

On 22 June 1940, the Second Armistice at Compiègne was signed by France and Germany. The neutral Vichy government led by Marshal Philippe Pétain replaced the Third Republic and German military occupation began along the French North Sea and Atlantic coasts and their hinterlands. The Italian invasion of France over the Alps took a small amount of ground and after the armistice, Italy occupied a small area in the south-east. The Vichy regime retained the zone libre (free zone) in the south. Following the Allied invasion of French North Africa in November 1942, in Case Anton, the Germans and Italians took control of the zone until it was liberated by the Allies in 1944.

خلفية

خط ماجينو

During the 1930s, the French built the Maginot Line, fortifications along the border with Germany.[24] The line was intended to economise on manpower and deter a German invasion across the Franco – German border by diverting it into Belgium, which could then be met by the best divisions of the French Army. The war would take place outside French territory, avoiding the destruction of the First World War.[25][26] The main section of the Maginot Line ran from the Swiss border and ended at Longwy; the hills and woods of the Ardennes region were thought to cover the area to the north.[27] General Philippe Pétain declared the Ardennes to be "impenetrable" as long as "special provisions" were taken to destroy an invasion force as it emerged from the Ardennes by a pincer attack. The French commander-in-chief, Maurice Gamelin also believed the area to be safe from attack, noting it "never favoured large operations". French war games held in 1938, of a hypothetical German armoured attack through the Ardennes, left the army with the impression that the region was still largely impenetrable and that this, along with the obstacle of the Meuse River, would allow the French time to bring up troops into the area to counter an attack.[28]

الغزو الألماني لپولندا

In 1939, the United Kingdom and France offered military support to Poland in the likely case of a German invasion.[29] At dawn on 1 September 1939, the German invasion of Poland began. France and the United Kingdom declared war on 3 September, after an ultimatum for German forces immediately to withdraw their forces from Poland was not answered.[30] Australia and New Zealand also declared war on 3 September, South Africa on 6 September and Canada on 10 September. While British and French commitments to Poland were met politically, the Allies failed to fulfil their military obligations to Poland, later called the Western betrayal by the Poles. The possibility of Soviet assistance to Poland had ended with the Munich Agreement of 1938, after which the Soviet Union and Germany eventually negotiated the Nazi–Soviet Pact, which included an agreement to partition Poland. The Allies settled on a long-war strategy in which they would complete the rearmament plans of the 1930s while fighting a defensive land war against Germany and weakening its war economy with a trade blockade, ready for an eventual invasion of Germany.[31]

الحرب الزائفة

On 7 September, in accordance with the Franco-Polish alliance, France began the Saar Offensive with an advance from the Maginot Line 5 km (3 mi) into the Saar. France had mobilised 98 divisions (all but 28 of them reserve or fortress formations) and 2,500 tanks against a German force consisting of 43 divisions (32 of them reserves) and no tanks. The French advanced until they met the thin and undermanned Siegfried Line. On 17 September, Gamelin gave the order to withdraw French troops to their starting positions; the last of them left Germany on 17 September, the day of the Soviet invasion of Poland. Following the Saar Offensive, a period of inaction called the Phoney War (the French Drôle de guerre, joke war or the German Sitzkrieg, sitting war) set in between the belligerents. Adolf Hitler had hoped that France and Britain would acquiesce in the conquest of Poland and quickly make peace. On 6 October, he made a peace offer to both Western powers.[32][33][34]

خطط الألمان وخطط الحلفاء

- بعد انتهاء عملية غزو بولندا في أكتوبر 1939، بدأ الألمان ينقلون قواتهم تدريجياً إلى الجبهة الغربية، وبدأوا في إعداد الخطط للهجوم، وكانت الخطة الأساسية هي خطة شليفن التي أقرها عسكري ألماني توفي قبل الحرب العالمية الأولى، وطبقت في تلك الحرب ولم تحقق نجاحاً (لأسباب عديدة لا تتعلق بالضرورة بعيب في الخطة)، وكان القائد الألماني إريش فون مانشتاين رئيس أركان مجموعة الجيوش أ، (التي يقودها القائد غيرد فون رونتشتيت) ينتقد هذه الخطة واقترح خطة بديلة تجعل الهجوم الرئيسي (مهمة المجموعة أ) يكون عبر غابة الأردين (لوكسمبورغ وجنوب بلجيكا)بينما يكون الهجوم الثانوي (مهمة مجوعة الجيوش ب التي يقودها القائد فيدور فون بوك) يكون شمال كما هذه المجموعة (هولندا، وبلجيكا)، وقد عارض فون بوك هذه الخطة (التي تجعل من هجومه هجوماً ثانوياً) متسائلاً كيف يمكن للقوات الألمانية التقدم لمسافة 300 كم من دون أن يعترضها طيران الحلفاء، وعموماً لم تتحمس القيادة الألمانية العليا لخطة مانشتاين (التي ساعده في إعدادها القائد هاينز جوديريان) إلاّ بعد أن سقطت طائرة ألمانية في بلجيكا، في 10 يناير 1940، تحمل وصفاً للخطة القديمة، فتم تبني خطة مانشتاين بصفة نهائية.

- مع ذلك كانت الخطة مانشتاين شأنها شأن خطة شليفن لها عيب أخلاقي يتمثل في مهاجمة الدول المحايدة خصوصاً بلجيكا ، لكن لم يكن ذلك يشكل هاجساً إلا للقائد ويلهلم ريتر فون ليب قائد مجموعة الجيوش جـ، الذي يواجه الحدود الألمانية الفرنسية، لكن المهم هنا أنها لم تشكل هاجساً للزعيم الألماني أدولف هتلر صاحب الأمر والنهي في الدولة.

- كانت مجموعة رونتشتيت، المكلفة بالقيام بالهجوم الرئيسي عبرالأردين، تحوي ثلاث فيالق مدرعة (موزعة على سبع فرق) يقودها كل من خبير الدبابات جوديريان، وهانز جورج راينهارت Rheinhardt، وهيرمان هوت Hoth.

- في المقابل لم يكن الفرنسيون، وعلى رأسهم قائد قوات الحلفاء الفرنسي موريس غاملين Gamelin، من السذاجة بحيث يعتقدون أن الألمان سيتركون الدول المحايدة، ويهاجمون فرنسا من الحدود الألمانية الفرنسية حيث يواجههم خط ماجينو، لكن غاملين كان يعتقد أن الألمان سيعيدون تنفيذ خطة شليفن (وهو ما كاد أن يتحقق)، ولذلك وضع الحلفاء خطة اسمها ديل Dyle Plan وهي تسعى إلى صد هجوم الألمان الرئيسي عبر الدول المحايدة، وكان هناك عائق سياسي لهذه الخطة وهو أن تلك الدول لن تسمح لفرنسا، وبريطانيا باستعمال أراضيها ضد ألمانيا، وذلك لأنها دول محايدة. لم يتوقع أحد أن الألمان سيجعلون هجومهم عبر غابة الأردين (والتي هي في نظرهم مانع طبيعي ضد الغزو) هو الهجوم الرئيسي، باستثناء ضابط فرنسي واحد، لم يعره أحد اهتماماً.

ميزان القوى

كان لدى الألمان 2600 دبابة في حين أن البريطانيون والفرنسيون وحدهم لديهم 3600 دبابة. لكن في المقابل كان لدى الألمان 2750 طائرة مقابل 1690 للفرنسيين والبريطانيين.

بدء الهجوم

- بدأ الهجوم الألماني يوم 10 مايو 1940، بإنزال بالمظلات على هولندا، وبلجيكا قامت به كل من الفرقة الجوية السابعة بقيادة كورت شتودنت، وفرقة المشاة 22 بقيادة شبونيك Sponeck، ويدعمهم الأسطول الجوي الثاني بقيادة ألبرت كسلرنغ، وبالرغم من ردة الفعل السريعة التي قام بها الحلفاء، كان التفوق من نصيب الألمان، ففي يوم 14 مايو أعلن الهولنديون الاستسلام.

- في المقابل بدأت مجموعة رونتشتيت اختراق غابة الأردين، والاتجاه إلى نهر الموز Meuse ، وحققت مهمتها بنجاح، ونجحت في الفصل بين قوات الحلفاء، الذين حاولوا القيام بهجوم فرنسي (يقوده شارل ديغول)، يومي 17 و 19 مايو، وهجوم بريطاني. لكن الحلفاء فشلوا في إعادة اللحمة لقواتهم، وفي يوم 20 مايو كان فيلق جوديريان قد وصل مدينة نويل Noyelles على الشاطئ، فصارت الفصل بين قوات الحلفاء كاملاً.

- حاول رئيس الوزراء الفرنسي بول رينو إنقاذ الوضع المتدهور، فاتصل في 17 مايو بالقائد ماكسيم ويغان Weygand (الذي كان في سوريا) وعينه القائد العام لقوات الحلفاء محل غاملين، فوصل ويغان يوم 19 مايو، ولكن لم يكن لديه عصىً سحرية لتغيير الوضع.

دنكرك

- استمرضغط الألمان على قوات الحلفاء في المحاصرة في الشمال، وفي يوم 28 مايو استسلم البلجيكيون بعد مقاومة كبيرة. ورأى رئيس الوزراء البريطاني ونستون تشرشل، الذي استلم الحكم يوم 10 مايو 1940، أن الحل الأفضل هو إجلاء القوات حتى لا تتعرض للأسر، وكان أقصى ما يطمح له هو إخراج 20,000 جندي.

- لكن الحلفاء التقطوا إشارة لاسلكية تخص مجموعة الجيوش أ التي يقودها رونتشتيت تقضي بإيقاف الهجوم، وهناك خلاف حول ما إذا كان هتلر أو رونتشتيت هو صاحب هذا الأمر، لكنه كان على أية حال الفرصة الذهبية للحلفاء لإنقاذ قواتهم، وبحلول الرابع من يونيو كانوا قد تمكنوا من إجلاء أكثر من 338,000 جندي. لكن لم يكن جنود الجيش الفرنسي الأول لهم نفس الحظ حيث حوصروا في مدينة ليل Lille.

استسلام فرنسا

- عندما اتضح للزعيم الإيطالي بينيتو موسوليني أن الألمان قد حسموا الحرب لصالحهم، أعلن الحرب على بريطانيا، وفرنسا في 10 يونيو، ومع ذلك لم تحقق جيوشه إنجازاً يفخر به.

- في يوم 14 يونيو دخل الألمان باريس، ولم تستمر المقاومة الفرنسية بعد ذلك طويلاً، إذ استقال رئيس الوزراء رينو في 16 يونيو، وخلفه في الحكومة القائد الشهير فيليب بيتان، بطل الحرب العالمية الأولى، ووقعت حكومته اتفاقية الهدنة في 22 يونيو في غابة كومبين في نفس العربة التي وقع فيها الألمان الهدنة عام 1918، وفي يوم 24 يونيو وقعوا الهدنة مع الإيطاليين، وتوقف إطلاق النار فجر اليوم التالي.

ما بعد النصر

- كلف الألمان هذا النصر (حسب القيادة العليا الألمانية) 27,074 قتيلاً، و111,034 جريحاً، و18,384 مفقوداً، فيما خسر الإيطاليون 631 قتيلاً، 2,631 جريحاً، و616 مفقوداً.

- في المقابل خسر الفرنسيون أكثر من 92,000 قتيل، و250,000 جريح. لكن خسارتهم الكبرى كانت حرية وطنهم، فتزعم ديغول حركة المقاومة من المنفى.

- بالنسبة لهتلر لم يكن هذا ثاراً من هزيمة الحرب العالمية الأولى فقط، لكنه كان أيضاً تحييدأ للجبهة الخلفية، وصار الآن حراً في أن ينفذ مشروعه التوسعي نحو الشرق أي نحو الاتحاد السوفيتي.

تحليل

The title of Ernest May's book Strange Victory: Hitler's Conquest of France (2000) nods to an earlier analysis, Strange Defeat (written 1940; published 1946) by the historian Marc Bloch (1886–1944), a participant in the battle. May wrote that Hitler had better insight into the French and British governments than vice-versa and knew that they would not go to war over Austria and Czechoslovakia, because he concentrated on politics rather than the state and national interest. From 1937 to 1940, Hitler gave his views on events, their importance and his intentions, then defended them against contrary opinion from the likes of the former Chief of the General Staff Ludwig Beck and Ernst von Weizsäcker. Hitler sometimes concealed aspects of his thinking but he was unusually frank about priority and his assumptions. May referred to John Wheeler-Bennett (1964),

Except in cases where he had pledged his word, Hitler always meant what he said.[35]

May asserted that in Paris, London and other capitals, there was an inability to believe that someone might want another world war. He wrote that, given public reluctance to contemplate another war and a need to reach consensus about Germany, the rulers of France and Britain were reticent (to resist German aggression), which limited dissent at the cost of enabling assumptions that suited their convenience. In France, Édouard Daladier withheld information until the last moment and in September 1938 presented the Munich Agreement to the French cabinet as a fait accompli, thus avoiding discussions over whether Britain would follow France into war or if the military balance was really in Germany's favour or how significant it was. The decision for war in September 1939 and the plan devised in the winter of 1939–1940 by Daladier for war with the USSR followed the same pattern.[36]

Hitler had miscalculated Franco-British reactions to the invasion of Poland in September 1939, because he had not realised that a shift in public opinion had occurred in mid-1939. May wrote that the French and British could have defeated Germany in 1938 with Czechoslovakia as an ally and also in late 1939, when German forces in the West were incapable of preventing a French occupation of the Ruhr, which would have forced a capitulation or a futile German resistance in a war of attrition. France did not invade Germany in 1939 because it wanted British lives to be at risk too and because of hopes that a blockade might force a German surrender without a bloodbath. The French and British also believed that they were militarily superior, which guaranteed victory. The run of victories enjoyed by Hitler from 1938 to 1940 could only be understood in the context of defeat being inconceivable to French and British leaders.[37]

May wrote that when Hitler demanded a plan to invade France in September 1939, the German officer corps thought that it was foolhardy and discussed a coup d'état, only backing down when doubtful of the loyalty of the soldiers to them. With the deadline for the attack on France being postponed so often, OKH had time to revise Fall Gelb (Case Yellow) for an invasion over the Belgian Plain several times. In January 1940, Hitler came close to ordering the invasion but was prevented by bad weather. Until the Mechelen incident in January forced a fundamental revision of Fall Gelb, the main effort (schwerpunkt) of the German army in Belgium would have been confronted by first-rate French and British forces, equipped with more and better tanks and with a great advantage in artillery. After the Mechelen Incident, OKH devised an alternative and hugely risky plan to make the invasion of Belgium a decoy, switch the main effort to the Ardennes, cross the Meuse and reach the Channel coast. May wrote that although the alternative plan was called the Manstein Plan, Guderian, Manstein, Rundstedt, Halder and Hitler had been equally important in its creation.[38]

War games held by Generalmajor (Major-General) Kurt von Tippelskirch, the chief of army intelligence and Oberst Ulrich Liss of Fremde Heere West (FHW, Foreign Armies West), tested the concept of an offensive through the Ardennes. Liss thought that swift reactions could not be expected from the "systematic French or the ponderous English" and used French and British methods, which made no provision for surprise and reacted slowly when one was sprung. The results of the war games persuaded Halder that the Ardennes scheme could work, even though he and many other commanders still expected it to fail. May wrote that without the reassurance of intelligence analysis and the results of the war games, the possibility of Germany adopting the ultimate version of Fall Gelb would have been remote. The French Dyle-Breda variant of the Allied deployment plan was based on an accurate prediction of German intentions, until the delays caused by the winter weather and shock of the Mechelen Incident, led to the radical revision of Fall Gelb. The French sought to assure the British that they would act to prevent the Luftwaffe using bases in the Netherlands and the Meuse valley and to encourage the Belgian and Dutch governments. The politico-strategic aspects of the plan ossified French thinking, the Phoney War led to demands for Allied offensives in Scandinavia or the Balkans and the plan to start a war with the USSR. French generals thought that changes to the Dyle-Breda variant might lead to forces being taken from the Western Front.[39]

French and British intelligence sources were better than the German equivalents, which suffered from too many competing agencies but Allied intelligence analysis was not as well integrated into planning or decision-making. Information was delivered to operations officers but there was no mechanism like the German system of allowing intelligence officers to comment on planning assumptions about opponents and allies. The insularity of the French and British intelligence agencies meant that had they been asked if Germany would continue with a plan to attack across the Belgian plain after the Mechelen Incident, they would not have been able to point out how risky the Dyle-Breda variant was. May wrote that the wartime performance of the Allied intelligence services was abysmal. Daily and weekly evaluations had no analysis of fanciful predictions about German intentions. A May 1940 report from Switzerland that the Germans would attack through the Ardennes was marked as a German spoof. More items were obtained about invasions of Switzerland or the Balkans, while German behaviour consistent with an Ardennes attack, such as the dumping of supplies and communications equipment on the Luxembourg border or the concentration of Luftwaffe air reconnaissance around Sedan and Charleville-Mézières, was overlooked.[40]

According to May, French and British rulers were at fault for tolerating poor performance by the intelligence agencies; that the Germans could achieve surprise in May 1940, showed that even with Hitler, the process of executive judgement in Germany had worked better than in France and Britain. May referred to Strange Defeat that the German victory was a "triumph of intellect", which depended on Hitler's "methodical opportunism". May further asserted that, despite Allied mistakes, the Germans could not have succeeded but for outrageous good luck. German commanders wrote during the campaign and after, that often only a small difference had separated success from failure. Prioux thought that a counter-offensive could still have worked up to 19 May but by then, roads were crowded with Belgian refugees when they were needed for redeployment and the French transport units, which performed well in the advance into Belgium, failed for lack of plans to move them back. Gamelin had said "It is all a question of hours." but the decision to sack Gamelin and appoint Weygand, caused a two-day delay.[41]

الاحتلال

France was divided into a German occupation zone in the north and west and a zone libre (free zone) in the south. Both zones were nominally under the sovereignty of the French rump state headed by Pétain that replaced the Third Republic; this rump state is often referred to as Vichy France. De Gaulle, who had been made an Undersecretary of National Defence by Reynaud in London at the time of the armistice, refused to recognise Pétain's Vichy government as legitimate. He delivered the Appeal of 18 June, the beginning of Free France.[42]

The British doubted Admiral François Darlan's promise not to allow the French fleet at Toulon to fall into German hands by the wording of the armistice conditions. They feared the Germans would seize the fleet, docked at ports in Vichy France and North Africa and use them in an invasion of Britain (Operation Sea Lion). Within a month, the Royal Navy conducted the Attack on Mers-el-Kébir against French ships at Oran.[43] The British Chiefs of Staff Committee had concluded in May 1940 that if France collapsed, "we do not think we could continue the war with any chance of success" without "full economic and financial support" from the United States. Churchill's desire for American aid led in September to the Destroyers for Bases agreement that began the Atlantic Charter the wartime Anglo-American partnership.[44]

The occupation of the various French zones continued until November 1942, when the Allies began Operation Torch, the invasion of Western North Africa. To safeguard southern France, the Germans enacted Case Anton and occupied Vichy France.[45] In June 1944, the Western Allies launched Operation Overlord, followed by the Operation Dragoon on the French Mediterranean coast on 15 August. This threatened to cut off German troops in western and central France and most began to retire toward Germany (The fortified French Atlantic U-boat bases remained as pockets until the German capitulation.). On 24 August 1944, Paris was liberated and by September 1944 most of the country was in Allied hands.[46]

The Free French provisional government declared the re-establishment of a provisional French Republic to ensure continuity with the defunct Third Republic. It set about raising new troops to participate in the advance to the Rhine and the Western Allied invasion of Germany by using the French Forces of the Interior as military cadres and manpower pools of experienced fighters to allow a very large and rapid expansion of the French Liberation Army (Armée française de la Libération). It was well equipped and well supplied despite the economic disruption brought by the occupation thanks to Lend-Lease and grew from 500,000 men in the summer of 1944 to over 1,300,000 by V-E day, making it the fourth largest Allied army in Europe.[47]

The 2e Division Blindée (2nd Armoured Division), part of the Free French forces that had participated in the Normandy Campaign and had liberated Paris, went on to liberate Strasbourg on 23 November 1944, fulfilling the Oath of Kufra made by General Leclerc almost four years earlier. The unit under his command, barely above company size when it had captured the Italian fort, had grown into an armoured division. The I Corps was the spearhead of the Free French First Army that had landed in Provence as a part of Operation Dragoon. Its leading unit, the 1re Division Blindée, was the first Western Allied unit to reach the Rhône (25 August), the Rhine (19 November) and the Danube (21 April 1945). On 22 April, it captured the Sigmaringen enclave in Baden-Württemberg, where the last Vichy regime exiles were hosted by the Germans in one of the ancestral castles of the Hohenzollern dynasty.[citation needed]

By the end of the war, some 580,000 French citizens had died (40,000 of these were killed by the western Allied forces during the bombardments of the first 48 hours of Operation Overlord).[citation needed] Military deaths were 55,000–60,000 in 1939–40.[48] Some 58,000 were killed in action from 1940 to 1945 fighting in the Free French forces. Some 40,000 malgré-nous ("against our will", citizens of the re-annexed Alsace-Lorraine province drafted into the Wehrmacht) became casualties. Civilian casualties amounted to around 150,000 (60,000 by aerial bombing, 60,000 in the resistance and 30,000 murdered by German occupation forces). Prisoners of war and deportee totals were around 1,900,000; of these, around 240,000 died in captivity. An estimated 40,000 were prisoners of war, 100,000 racial deportees, 60,000 political prisoners and 40,000 died as slave labourers.[49]

الخسائر

German casualties are hard to determine but commonly accepted figures are: 27,074 killed, 111,034 wounded and 18,384 missing.[5][6][7] German deaths may have been as high as 45,000 men, due to non-combat causes, such as death from wounds and missing who were later listed as dead.[5] The battle cost the Luftwaffe 28 per cent of its front line strength; some 1,236–1,428 aircraft were destroyed (1,129 to enemy action, 299 in accidents), 323–488 were damaged (225 to enemy action, 263 in accidents), making 36 per cent of the Luftwaffe strength lost or damaged.[5][50][22] Luftwaffe casualties amounted to 6,653 men, including 4,417 aircrew; of these 1,129 were killed and 1,930 were reported missing or captured, many of whom were liberated from French prison camps upon the French capitulation.[8] Italian casualties amounted to 631 or 642 men killed, 2,631 wounded and 616 reported missing. A further 2,151 men suffered from frostbite during the campaign. The official Italian numbers were compiled for a report on 18 July 1940, when many of the fallen still lay under snow and it is probable that most of the Italian missing were dead. Units operating in more difficult terrain had higher ratios of missing to killed but probably most of the missing had died.[51]

According to the French Defence Historical Service, 85,310 French military personnel were killed (including 5,400 Maghrebis); 12,000 were reported missing, 120,000 were wounded and 1,540,000 prisoners (including 67,400 Maghrebis) were taken.[52] Some recent French research indicates that the number of killed was between 55,000 and 85,000, a statement of the French Defence Historical Service tending to the lower end.[6][ز] In August 1940, 1,540,000 prisoners were taken into Germany, where roughly 940,000 remained until 1945, when they were liberated by advancing Allied forces. At least 3,000 Senegalese Tirailleurs were murdered after being taken prisoner.[54] While in captivity, 24,600 French prisoners died; 71,000 escaped; 220,000 were released by various agreements between the Vichy government and Germany; several hundred thousand were paroled because of disability and/or sickness.[55] Air losses are estimated at 1,274 aircraft destroyed during the campaign.[22] French tank losses amount to 1,749 tanks (43 per cent of tanks engaged), of which 1,669 were lost to gunfire, 45 to mines and 35 to aircraft. Tank losses are amplified by the large numbers that were abandoned or scuttled and then captured.[4]

The BEF suffered 66,426 casualties, 11,014 killed or died of wounds, 14,074 wounded and 41,338 men missing or taken prisoner.[17] About 64,000 vehicles were destroyed or abandoned and 2,472 guns were destroyed or abandoned. RAF losses from 10 May – 22 June, amounted to 931 aircraft and 1,526 casualties. The Allied naval forces also lost 243 ships to Luftwaffe bombing in Dynamo.[56] Belgian losses were 6,093 killed, 15,850 wounded and more than 500 missing.[19][18] Those captured amounted to 200,000 men, of whom 2,000 died in captivity.[19][57] The Belgians also lost 112 aircraft.[58] The Dutch Armed forces lost 2,332 killed and 7,000 wounded.[59] Polish losses were around 5,500 killed or wounded and 16,000 prisoners, nearly 13,000 troops of the 2nd Infantry Division were interned in Switzerland for the duration of the war.[60][citation needed]

رد الفعل الشعبي في ألمانيا

Hitler had expected a million Germans to die in conquering France; instead, his goal was accomplished in just six weeks with only 27,000 Germans killed, 18,400 missing and 111,000 wounded, little more than a third of the German casualties in the Battle of Verdun during World War I.[61] The unexpectedly swift victory resulted in a wave of euphoria among the German population and a strong upsurge in war-fever.[62] Hitler's popularity reached its peak with the celebration of the French capitulation on 6 July 1940.

"If an increase in feeling for Adolf Hitler was still possible, it has become reality with the day of the return to Berlin", commented one report from the provinces. "In the face of such greatness," ran another, "all pettiness and grumbling are silenced." Even opponents to the regime found it hard to resist the victory mood. Workers in the armaments factories pressed to be allowed to join the army. People thought final victory was around the corner. Only Britain stood in the way. For perhaps the only time during the Third Reich there was genuine war-fever among the population.

— Kershaw[63]

On 19 July, during the 1940 Field Marshal Ceremony at the Kroll Opera House in Berlin, Hitler promoted 12 generals to the rank of field marshal.

- Walther von Brauchitsch, Commander in Chief of the Army

- Wilhelm Keitel, Chief of the Oberkommando der Wehrmacht (OKW)

- Gerd von Rundstedt, Commander in chief of Army Group A

- Fedor von Bock, Commander in chief of Army Group B

- Wilhelm von Leeb, Commander in chief of Army Group C

- Günther von Kluge, Commander of the 4th Army

- Wilhelm List, Commander of the 12th Army

- Erwin von Witzleben, Commander of the 1st Army

- Walther von Reichenau, Commander of the 6th Army

- Albert Kesselring, Commander of Luftflotte 2 (Air Fleet 2)

- Erhard Milch, Inspector General of the Luftwaffe

- Hugo Sperrle, Commander of the Luftflotte 3 (Air Fleet 3)

This number of promotions to what had previously been the highest rank in the Wehrmacht (Hermann Göring, Commander in chief of the Luftwaffe and already a Field Marshal, was elevated to the new rank of Reichsmarschall) was unprecedented. In the First World War, Kaiser Wilhelm II had promoted only five generals to Field Marshal.[64][65]

شهود عيان

- From Lemberg to Bordeaux (Von Lemberg bis Bordeaux), written by Leo Leixner, a journalist and war correspondent, is a witness account of the battles that led to the fall of Poland and France. In August 1939, Leixner joined the Wehrmacht as a war reporter, was promoted to sergeant and in 1941 published his recollections. The book was originally issued by Franz Eher Nachfolger, the central publishing house of the Nazi Party.[66]

- Tanks Break Through! (Panzerjäger Brechen Durch!), written by Alfred-Ingemar Berndt, a journalist and close associate of propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels, is a witness account of the battles that led to the fall of France. When the 1940 attack was in the offing, Berndt joined the Wehrmacht, was sergeant in an anti-tank division and afterward published his recollections.[67] The book was originally issued by Franz Eher Nachfolger, the central publishing house of the Nazi Party, in 1940.[68]

- Escape via Berlin (De Gernika a Nueva York), written by José Antonio Aguirre, president of the Basque Country, describes his passage through occupied France and Belgium on his way to exile. Aguirre supported the loyalist side during the Spanish Civil war and was forced to exile in France, where the German invasion took him by surprise. He joined the wave of refugees trying to flee France and finally managed to escape to the United States through a long journey involving disguise.

- Berlin Diary, published in 1941 by William L. Shirer, a foreign correspondent for CBS World News Roundup in the prewar period, gives a day-by-day account of his reporting before, during, and after the Battle of France, including conversations with military and political leaders - as well as ordinary soldiers and civilians - on both the Allied and Axis sides. Unable to continue reporting the war honestly from Berlin due to increasing German censorship, Shirer returned to the United States in December 1940.

انظر أيضاً

- British Expeditionary Force order of battle (1940)

- Polish Army in France (1939–40)

- Historiography of the Battle of France

- Military history of France during World War II

- List of French World War II military equipment

- List of British military equipment of World War II

- List of Belgian military equipment of World War II

- List of Dutch military equipment of World War II

- List of German military equipment of World War II

- Timeline of the Battle of France

- Western Front (World War II)

Notes

- ^ أ ب Until 17 May

- ^ From 17 May

- ^ Hooton uses the Bundesarchiv, Militärarchiv in Freiburg. Luftwaffe strength included gliders and transports used in the assaults on the Netherlands and Belgium.[3]

- ^ Hooton used the National Archives in London for RAF records, including "Air 24/679 Operational Record Book: The RAF in France 1939–1940", "Air 22/32 Air Ministry Daily Strength Returns", "Air 24/21 Advanced Air Striking Force Operations Record" and "Air 24/507 Fighter Command Operations Record". For the Armée de l'Air Hooton used "Service Historique de Armée de l'Air (SHAA), Vincennes".[3]

- ^ The final count of the German dead is possibly as high as 49,000 men when including the losses suffered by the Kriegsmarine, because of additional non-combat causes, wounded who died of their injuries and the missing who were confirmed as dead.[5]

- ^ Steven Zaloga wrote, "Of the 2,439 panzers originally committed 822, or about 34 per cent, were total losses after five weeks of fighting.... Detailed figures for the number of mechanical breakdowns are not available and are not relevant as in the French case, since, as the victors, the Wehrmacht could recover damaged or broken-down tanks and put them back into service".[11]

- ^ Official Italian report on 18 July 1940: Italian casualties amounted to 631 or 642 men killed, 2,631 wounded and 616 reported missing. A further 2,151 men suffered from frostbite during the campaign.[12][13][14]

- ^ French:

≈60,000 killed

200,000 wounded

12,000 missing[15][16]

British:

11,014 dead

14,074 wounded

41,338 missing and POW

1,526 RAF casualties[17]

Belgian:

6,093 killed

15,850 wounded

500 missing[18][19]

Dutch:

2,332 killed

7,000 wounded

Polish:

5,500 killed or wounded[20]

Luxembourg:

7 wounded[21] - ^ Steven Zaloga notes that "According to a postwar French Army study, French tank losses in 1940 amounted to 1,749 tanks lost out of 4,071 engaged, of which 1,669 were lost to gunfire, 45 to mines and 35 to aircraft. This amounts to about 43 per cent. French losses were substantially amplified by the large numbers of tanks that were abandoned or scuttled by their crews".[4]

- ^ Jonathan Fennell notes "Losses 'included 180,000 rifles, 10,700 Bren guns, 509 two-pounder anti-tank guns, 509 cruiser tanks and 180 infantry tanks'."[23]

- ^ "Combat losses amounted in reality to 58,829 deaths, excluding marine however, whose deaths were registered under different procedures."[53]

الهامش

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح Scheck 2010, p. 426.

- ^ أ ب ت Umbreit 2015, p. 279.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Hooton 2007, pp. 47–48.

- ^ أ ب ت Zaloga 2011, p. 73.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح Frieser 1995, p. 400.

- ^ أ ب ت L'Histoire, No. 352, April 2010 France 1940: Autopsie d'une défaite, p. 59.

- ^ أ ب Sheppard 1990, p. 88.

- ^ أ ب Hooton 2010, p. 73.

- ^ Murray 1983, p. 40.

- ^ Healy 2007, p. 85.

- ^ Zaloga 2011, p. 76.

- ^ Sica 2012, p. 374.

- ^ Porch 2004, p. 43.

- ^ Rochat 2008, para. 19.

- ^ de La Gorce 1988, p. 496.

- ^ Quellien 2010, pp. 262–263.

- ^ أ ب Sebag-Montefiore 2006, p. 506.

- ^ أ ب Dear & Foot 2005, p. 96.

- ^ أ ب ت Ellis 1993, p. 255.

- ^ Jacobson, 2015, nopp

- ^ "Inauguration du Monument érigé à la Mémoire des Morts de la Force Armée de la guerre de 1940–1945" (PDF). Grand Duché de Luxembourg Ministére D'État Bulletin D'Information (in الفرنسية). Vol. 4, no. 10. Luxembourg: Service information et presse. 31 October 1948. p. 147. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 January 2017. Retrieved 22 May 2020.

- ^ أ ب ت Hooton 2007, p. 90.

- ^ Fennell 2019, p. 115.

- ^ Clayton Donnell, The Battle for the Maginot Line, 1940 (Pen and Sword, 2017).

- ^ Jackson 2003, p. 33.

- ^ Roth 2010, p. 6.

- ^ Kaufmann & Kaufmann 2007, p. 23.

- ^ Jackson 2003, pp. 32–33.

- ^ Baliszewski 2004.

- ^ Viscount Halifax to Sir N. Henderson (Berlin) Archived 2 أكتوبر 2017 at the Wayback Machine Cited in the British Blue book

- ^ "Chronology 1939". indiana.edu. Archived from the original on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 12 December 2015.

- ^ Shirer 1990, p. 715

- ^ Full text of the speech (in German, pdf)

- ^ archive.org: Video of his speech (77 min)

- ^ May 2000, p. 453.

- ^ May 2000, pp. 453–454.

- ^ May 2000, pp. 454–455.

- ^ May 2000, pp. 455–456.

- ^ May 2000, pp. 456–457.

- ^ May 2000, pp. 457–458.

- ^ May 2000, pp. 458–460.

- ^ Dear & Foot 2005, pp. 336–339.

- ^ Dear & Foot 2005, p. 317.

- ^ Reynolds 1993, pp. 248, 250–251.

- ^ Dear & Foot 2005, p. 635.

- ^ Dear & Foot 2005, p. 634.

- ^ Imlay & Toft 2007, p. 227.

- ^ Carswell 2019, p. 92.

- ^ Dear & Foot 2005, p. 321.

- ^ Murray 1983.

- ^ Sica 2012, p. 374; Rochat 2008, p. 43, para. 19.

- ^ Gorce 1988, p. 496.

- ^ servicehistorique (20 November 2017)

- ^ Scheck 2010, p. 58.

- ^ Durand 1981, p. 21.

- ^ Churchill 1949, p. 102.

- ^ Keegan 2005, p. 96.

- ^ Hooton 2007, p. 52.

- ^ Goossens, Balance Sheet, waroverholland.nl

- ^ Jacobson.

- ^ Atkin, 1990, pp. 233–234

- ^ Neitzel and Welzer, 2012, pp. 193, 216

- ^ Kershaw, 2002, p. 407

- ^ Deighton 2008, pp. 7–9.

- ^ Ellis 1993, p. 94.

- ^ Leixner, Leo; Lehrer, Steven (2 March 2017). "From Lemberg to Bordeaux: a German war correspondent's account of battle in Poland, the low countries and France, 1939–40". SF Tafel Publishers – via catalog.loc.gov Library Catalog.

- ^ Berndt, Alfred-Ingemar (23 November 2016). Tanks Break Through!: A German Soldier's Account of War in the Low Countries and France, 1940. SF Tafel. ISBN 9781539810971 – via Google Books.

- ^ Berndt, Alfred-Ingemar (2 March 2016). "Tanks break through! a German soldier's account of war in the Low Countries and France, 1940". SF Tafel – via catalog.loc.gov Library Catalog.

مصادر

وصلات خارجية

- "WW2: Fall of France Campaign" (Flash animation). History. BBC.

- Brooke, Alan (1946). Despatch on Operations of the British Expeditionary Force in From 12th June, 1940 to 19th June, 1940 (PDF). London: War Office. In "No. 37573". The London Gazette (Supplement). 22 May 1946. pp. 2433–2439.

{{cite magazine}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - The Battle of France. Calvin. 1940.

{{cite book}}:|newspaper=ignored (help) (Official Nazi propaganda account of the Battle of France) - Goossens, Allert M.A. "The invasion of Holland in May 1940". NL.

- Gort, John (10 October 1941). "Viscount Gort's Despatch on Operations of the British Expeditionary Force in France and Belgium, 1939–1940". Supplement to the London Gazette, Number 35305. Retrieved 6 November 2009.

- US army report on the Battle of France

- CS1 الفرنسية-language sources (fr)

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Articles containing فرنسية-language text

- Pages using Lang-xx templates

- Articles containing ألمانية-language text

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Articles with unsourced statements from December 2021

- Articles with unsourced statements from January 2021

- Pages containing London Gazette template with parameter supp set to y

- CS1 errors: periodical ignored

- Pages using Sister project links with hidden wikidata

- Battle of France

- Conflicts in 1940

- 1940 in France

- World War II operations and battles of the Western European Theatre

- معارك الحرب العالمية الثانية التي شاركت فيها پولندا

- معارك الفيلق الأجنبي الفرنسي

- Battles of World War II involving Canada

- Military history of Canada during World War II

- معارك الحرب العالمية الثانية التي شاركت فيها فرنسا

- معارك الحرب العالمية الثانية التي شاركت فيها إيطاليا

- Battles and operations of World War II involving the United Kingdom

- Western European theatre of World War II

- Invasions by Germany

- Invasions of France

- May 1940 events

- June 1940 events

- الحرب العالمية الثانية

- تاريخ فرنسا