الفيل الآسيوي

| Asian elephant[1] | |

|---|---|

| |

| A male Asian elephant in the wild at Bandipur National Park in India | |

| التصنيف العلمي | |

| أصنوفة غير معروفة (أصلحها): | Elephas |

| Species: | Template:Taxonomy/ElephasE. maximus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Template:Taxonomy/ElephasElephas maximus | |

| Subspecies | |

|

E. m. maximus | |

| |

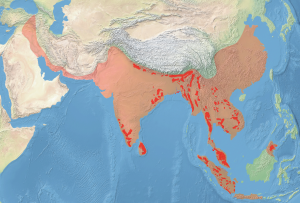

| Asian elephant range | |

The Asian or Asiatic elephant (Elephas maximus) is the only living species of the genus Elephas and is distributed in Southeast Asia from India in the west to Borneo in the east. Three subspecies are recognised—E. m. maximus from Sri Lanka, the E. m. indicus from mainland Asia, and E. m. sumatranus from the island of Sumatra.[1] Asian elephants are the largest living land animals in Asia.[4]

Since 1986, E. maximus has been listed as endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) as the population has declined by at least 50% over the last three generations, estimated to be 60–75 years. Asian elephants are primarily threatened by degradation, fragmentation and loss of habitat, and poaching.[3] In 2003, the wild population was estimated at between 41,410 and 52,345 individuals. Female captive elephants have lived beyond 60 years when kept in semi-natural surroundings, such as forest camps. In zoos, elephants die at a much younger age and are declining due to a low birth and high death rate.[5]

The genus Elephas originated in Sub-Saharan Africa during the Pliocene, and spread throughout Africa before emigrating into southern Asia.[2] The earliest indications of captive use of Asian elephants are engravings on seals of the Indus Valley civilization dated to the third millennium BC.[6]

Taxonomy

Carl Linnaeus first described the genus Elephas and an elephant from Ceylon under the binomial Elephas maximus in 1758.[7] In 1798, Georges Cuvier first described the Indian elephant under the binomial Elephas indicus.[8] In 1847, Coenraad Jacob Temminck first described the Sumatran elephant under the binomial Elephas sumatranus.[9] Frederick Nutter Chasen classified all three as subspecies of the Asian elephant in 1940.[10]

Three subspecies are currently recognised: the Sri Lankan elephant, the Indian elephant and the Sumatran elephant.[3][4] In 1950, Paules Edward Pieris Deraniyagala described the Borneo elephant under the trinomial Elephas maximus borneensis, taking as his type an illustration in the National Geographical Magazine, but not a living elephant in accordance with the rules of the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature.[11] E. m. borneensis lives in northern Borneo and is smaller than all the other subspecies, but with larger ears, a longer tail, and straight tusks. Results of genetic analysis indicate that its ancestors separated from the mainland population about 300,000 years ago.[12]

The population in Vietnam and Laos was tested to determine if it is a subspecies, as well. This research is considered vital, as less than 1300 wild Asian elephants remain in Laos.[13] In addition, two extinct subspecies are considered to have existed:

- The Chinese elephant is sometimes separated as E. m. rubridens (pink-tusked elephant); it disappeared after the 14th century BC.[citation needed]

- The Syrian elephant (E. m. asurus), the westernmost and the largest subspecies of the Asian elephant, became extinct around 100 BC. This population, along with the Indian elephant, was considered the best war elephant in antiquity, and was found superior to the smallish North African elephant (Loxodonta africana pharaoensis) used by the armies of Carthage.[citation needed]

Characteristics

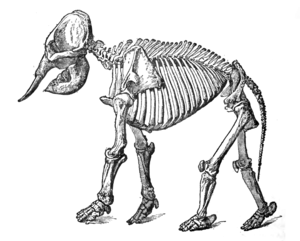

In general, the Asian elephant is smaller than the African elephant and has the highest body point on the head. The back is convex or level. The ears are small with dorsal borders folded laterally. It has up to 20 pairs of ribs and 34 caudal vertebrae. The feet have more nail-like structures than those of African elephants—five on each forefoot, and four on each hind foot.[4]

Size

Average shoulder height of females is 2.4 m (7.9 ft), and average weight is 2.7 t (3.0 short ton), while average shoulder height of males is 2.75 m (9.0 ft), and average weight is 4 t (4.4 short ton).[15][16][17] Length of body and head including trunk is 5.5–6.5 m (18–21 ft) with the tail being 1.2–1.5 m (3.9–4.9 ft) long.[4] The largest bull elephant ever recorded was shot by the Maharajah of Susang in the Garo Hills of Assam, India in 1924, it weighed 7 طن متري (7.7 short ton), stood 3.43 m (11.3 ft) tall at the shoulder and was 8.06 m (26.4 ft) long from head to tail.[17][18][19] There are reports of larger individuals as tall as 3.7 m (12 ft).[14]

Trunk

The distinctive trunk is an elongation of the nose and upper lip combined; the nostrils are at its tip, which has a one finger-like process. The trunk contains as many as 60,000 muscles, which consist of longitudinal and radiating sets. The longitudinals are mostly superficial and subdivided into anterior, lateral, and posterior. The deeper muscles are best seen as numerous distinct fasciculi in a cross-section of the trunk. The trunk is a multipurpose prehensile organ and highly sensitive, innervated by the maxillary division of the trigeminal nerve and by the facial nerve. The acute sense of smell uses both the trunk and Jacobson's organ. Elephants use their trunks for breathing, watering, feeding, touching, dusting, sound production and communication, washing, pinching, grasping, defense and offense.[4]

Tusks

Tusks serve to dig for water, salt, and rocks, to debark and uproot trees, as levers for maneuvering fallen trees and branches, for work, for display, for marking trees, as weapon for offense and defense, as trunk-rests, and as protection for the trunk. Elephants are known to be right or left tusked.[4]

Skin

Skin colour is usually gray, and may be masked by soil because of dusting and wallowing. Their wrinkled skin is movable and contains many nerve centers. It is smoother than that of African elephants, and may be depigmented on the trunk, ears, or neck. The epidermis and dermis of the body average 18 mm (0.71 in) thick; skin on the dorsum is 30 mm (1.2 in) thick providing protection against bites, bumps, and adverse weather. Its folds increase surface area for heat dissipation. They can tolerate cold better than excessive heat. Skin temperature varies from 24 إلى 32.9 °C (75.2 إلى 91.2 °F). Body temperature averages 35.9 °C (96.6 °F).[4]

Intelligence

Asian elephants are highly intelligent and self-aware.[20] They have a very large and highly convoluted neocortex, a trait also shared by humans, apes and certain dolphin species. Elephants have a greater volume of cerebral cortex available for cognitive processing than all other existing land animals, and extensive studies place elephants in the category of great apes in terms of cognitive abilities for tool use and tool making.[21] They exhibit a wide variety of behaviours, including those associated with grief, learning, allomothering, mimicry, play, altruism, use of tools, compassion, cooperation, self-awareness, memory, and language. Elephants are reported to go to safer ground during natural disasters like tsunamis and earthquakes, although there have been no scientific records of this since it is hard to recreate or predict natural disasters.[citation needed]

Distribution and habitat

Asian elephants inhabit grasslands, tropical evergreen forests, semi-evergreen forests, moist deciduous forests, dry deciduous forests and dry thorn forests, in addition to cultivated and secondary forests and scrublands. Over this range of habitat types elephants occur from sea level to over 3،000 m (9،800 ft). In the Eastern Himalaya in northeast India, they regularly move up above 3،000 m (9،800 ft) in summer at a few sites.[22] In China, Asian elephants survive only in the prefectures of Xishuangbanna, Simao, and Lincang of southern Yunnan.

Three subspecies are recognised:[3][4]

- the Sri Lankan elephant occurs in Sri Lanka;

- the Indian elephant occurs in mainland Asia: Bangladesh, Bhutan, Cambodia, China, India, Laos, Malay Peninsula, Myanmar, Nepal, تايلند, Vietnam;

- the Sumatran elephant occurs in Sumatra.

Ecology and behaviour

Reproduction

Interaction with humans

Domestication

The first historical record of the domestication of Asian elephants was in Harappan times.[23] Ultimately, the elephant went on to become a siege engine, a mount in war, a status symbol, a beast of burden, and an elevated platform for hunting during historical times in South Asia.[24]

Threats

The pre-eminent threats to Asian elephants today are loss, degradation and fragmentation of habitat, leading in turn to increasing conflicts between humans and elephants. They are poached for ivory and a variety of other products including meat and leather.[3]

Human–elephant conflict

Poaching

Handling methods

Young elephants are captured and illegally imported to Thailand from Myanmar for use in the tourism industry; calves are used mainly in amusement parks and are trained to perform various stunts for tourists.[25]

Conservation

Elephas maximus is listed on CITES Appendix I.[3]

Asian elephants are quintessential flagship species, deployed to catalyze a range of conservation goals, including:

In captivity

In culture

See also

المراجع

- ^ أ ب Shoshani, J. (2005). "Order Proboscidea". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 90. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ أ ب Haynes, G. (1993). Mammoths, mastodonts, and elephants: biology, behavior, and the fossil record. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, ISBN 0521456916

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح "Elephas maximus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2016.2. International Union for Conservation of Nature. 2008.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د Shoshani, J; Eisenberg, J. F. (1982). "Elephas maximus" (PDF). Mammalian Species. 182 (182): 1–8. doi:10.2307/3504045. JSTOR 3504045.

- ^ Sukumar, R. (2003). The Living Elephants: Evolutionary Ecology, Behavior, and Conservation. Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK. ISBN 9780195107784.

- ^ Sukumar, R. (1993). The Asian Elephant: Ecology and Management. 2nd edition. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-43758-X

- ^ Linnaei, C. (1760) Elephas maximus In: Caroli Linnæi Systema naturæ per regna tria naturæ, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. Tomus I. Halae Magdeburgicae. Page 33

- ^ Cuvier, G. (1798) Tableau elementaire de l’histoire naturelle des animaux. Baudouin, Paris

- ^ Temminck, C. J. (1847) Coup-d'oeil général sur les possessions néerlandaises dans l'Inde archipélagique. Tome second. A. Arnz and Comp., Leide

- ^ Chasen, F.H. (1940) A handlist of Malaysian mammals. Bulletin of the Raffles Museum 15: iii–209.

- ^ Cranbrook, E., Payne, J., Leh, C.M.U. (2008) Origin of the elephants Elephas maximus L. of Borneo. Sarawak Museum Journal.

- ^ Fernando, P.; Vidya, T. N. C.; Payne, J.; Stuewe, M.; Davison, G.; Alfred, R. J.; Andau, P.; Bosi, E.; Kilbourn, A. (2003). "DNA Analysis Indicates That Asian Elephants Are Native to Borneo and Are Therefore a High Priority for Conservation". PLoS Biol. 1 (1): e6. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0000006. PMC 176546. PMID 12929206.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|displayauthors=ignored (|display-authors=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Elefantasia 2008, ''Assist Us'', 1 January 2008 Archived 29 سبتمبر 2008 at the Wayback Machine. Elefantasia.org. Retrieved on 2013-09-27.

- ^ أ ب Lydekker, R. (1894). The Royal Natural History. Volume 2. Frederick Warne and Co., London.

- ^ Sukumar, R.; Joshi, N.V.; Krishnamurthy, V. (1988). "Growth in the Asian elephant". Proceedings of the Indian Academy of Sciences (Animal Sciences). 97: 561–571. doi:10.1007/BF03179558.

- ^ Kurt, F.; Kumarasinghe, J.C. (1998). "Remarks on body growth and phenotypes in Asian elephant Elephas maximus". Acta Theriologica. 5 (Supplement): 135–153. doi:10.4098/AT.arch.98-39.

- ^ أ ب Larramendi, A. (2016). "Shoulder height, body mass and shape of proboscideans" (PDF). Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 61. doi:10.4202/app.00136.2014.

- ^ Pillai, N.G. (1941). "On the height and age of an elephant". Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society. 42: 927–928.

- ^ Wood, G.L. (1982) The Guinness book of animal facts and feats. Guinness Superlatives. ISBN 0-85112-235-3

- ^ Aldous, P. (2006-10-30). "Elephants see themselves in the mirror". New Scientist.

- ^ Hart, B.L.; Hart, L.A.; McCoy, M.; Sarath, C.R. (November 2001). "Cognitive behaviour in Asian elephants: use and modification of branches for fly switching". Animal Behaviour. Academic Press. 62 (5): 839–847. doi:10.1006/anbe.2001.1815.

- ^ Choudhury, A. U. (1999). "Status and Conservation of the Asian elephant Elephas maximus in north-eastern India". Mammal Review. 29: 141–173. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2907.1999.00045.x.

- ^ McIntosh, J. (2008) The ancient Indus Valley: new perspectives. ABC-CLIO.

- ^ Rangarajan, M. (2001) The Forest and the Field in Ancient India. In: India's Wildlife History. Permanent Black, Delhi

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةStiles2009

للاستزادة

- Gilchrist, W. (1851) A Practical Treatise on the Treatment of the Diseases of the Elephant, Camel & Horned Cattle: with instructions for improving their efficiency; also, a description of the medicines used in the treatment of their diseases; and a general outline of their anatomy. Calcutta: Military Orphan Press

- Miall, L. C.; Greenwood, F. (1878). Anatomy of the Indian Elephant. London: Macmillan and Co.

وصلات خارجية

- Save Elephant Foundation

- International Elephant Foundation

- ElefantAsia: Protecting the Asian elephant

- Asian Elephants at the Zoological Gardens of the World

- Elephant Information Repository

- WWF—Asian elephant species profile

- National Zoo Facts on Asian Elephant and a Webcam of the Asian Elephant exhibit

- Environmental Investigation Agency: Illegal Wildlife Trade : Elephants

- CS1 errors: unsupported parameter

- CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI

- IUCN Red List endangered species

- Automatic taxobox cleanup

- Articles with unsourced statements from October 2011

- Articles with unsourced statements from June 2015

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Elephants

- ثدييات آسيا

- Fauna of South Asia

- Fauna of Southeast Asia

- EDGE species

- حيوانات آكلة للعشب

- Megafauna of Eurasia

- Mammals of Bangladesh

- Mammals of China

- Mammals of India

- Mammals of Malaysia

- Mammals of Nepal

- National symbols of Laos

- Wildlife of Yunnan

- Extant Pliocene first appearances

- Pliocene mammals of Asia

- Quaternary animals of Asia

- Animals described in 1758

- أصنوفات سماها كارل لينايوس

- Endangered animals

- Endangered biota of Asia