كلكتا

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

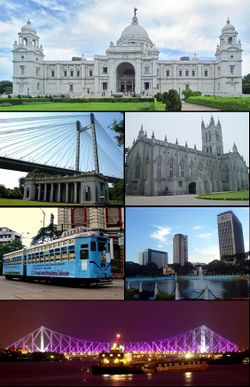

كـُلـْكـَتا Kolkata (بالبنغالية: কলকাতা, IPA: 'kolkat̪a , سابقاً: Calcutta, هي عاصمة الولاية الهندية البنغال الغربي. وتقع في شرق الهند على الضفة الشرقية من نهر هوغلي. ويبلغ تعداد سكان المدينة نحو 4.5 مليون, وباضافة سكان المنطقة الحضرية المحيطة يبلغ تعدادها 14 مليون، الأمر الذي يجعلها ثالث أكبر تجمع حضري بالهند ورابع أكبر مدينة في الهند.[6] Kolkata is seventh most populous city with an estimated city proper population of 4.5 million (0.45 crore) while its metropolitan region Kolkata Metropolitan Area is third most populous metropolitan region of India with metro population of over 15 million (1.5 crore).[7] Kolkata is the regarded by many sources as the cultural capital of India and a historically and culturally significant city in the historic region of Bengal.[8][9][10] It is the second largest Bengali-speaking city in the world. It has the highest number of Nobel laureates among all cities in India.

كلكتا مدينة هندية. وهي عاصمة ولاية البنغال الغربية. وتُعد ميناءً رئيسيًا للتجارة مع شرقي وجنوب شرقي آسيا. وتبلغ مساحتها 104 كم²، وعدد سكانها 4,399,819 نسمة، وعدد سكان كلكتا الكبرى 11,021,918 نسمة. وتواجه المدينة مشكلة الانفجار السكاني وتلوث البيئة والأوبئة حيث تبلغ الكثافة 42,000 نسمة/كم². وتعاني المدينة من نقص خطير في السكن، حيث يسكن نحو 30% من سكانها في الحارات الفقيرة، وينام عشرات الآلاف في الطرقات.

The three villages that predated Calcutta were ruled by the Nawab of Bengal under Mughal suzerainty. After the Nawab granted the East India Company a trading licence in 1690,[11] the area was developed by the Company into Fort William. Nawab Siraj ud-Daulah occupied the fort in 1756 but was defeated at the Battle of Plassey in 1757, after his general Mir Jafar mutinied in support of the company, and was later made the Nawab for a brief time.[12] Under company and later crown rule, Calcutta served as the de facto capital of India until 1911. Calcutta was the second largest city in the British Empire, after London,[13] and was the centre of bureaucracy, politics, law, education, science and the arts in India. The city was associated with many of the figures and movements of the Bengali Renaissance. It was the hotbed of the Indian nationalist movement.[14]

The partition of Bengal in 1947 affected the fortunes of the city. Following independence in 1947, Kolkata, which was once the premier centre of Indian commerce, culture, and politics, suffered many decades of political violence and economic stagnation before it rebounded.[15] In the late 20th century, the city hosted the government-in-exile of Bangladesh during the Bangladesh Liberation War in 1971.[16] It was also flooded with Hindu refugees from East Bengal (present-day Bangladesh) in the decades following the 1947 partition of India, transforming its landscape and shaping its politics.[17][18] The city was overtaken by Mumbai (formerly Bombay) as India's largest city.

A demographically diverse city, the culture of Kolkata features idiosyncrasies that include distinctively close-knit neighbourhoods (paras) and freestyle conversations (adda). Kolkata's architecture includes many imperial landmarks, including the Victoria Memorial, Howrah Bridge and the Grand Hotel. The city's heritage includes India's only Chinatown and remnants of Jewish, Armenian, Greek and Anglo-Indian communities. The city is closely linked with Bhadralok culture and the Zamindars of Bengal, including Bengali Hindu, Bengali Muslim and tribal aristocrats. The city is often regarded as India's cultural capital.

توجد في كلكتا ثلاث جامعات: جامعة كلكتا، وجامعة جادافبور، وجامعة رابندرا بهاراتي، كما توجد معاهد للبحث العلمي والإحصاء والعلوم والصحة. Kolkata is home to venerable institutions of national importance, including the Academy of Fine Arts, the Asiatic Society, the Indian Museum and the National Library of India. The University of Calcutta, first modern university in south Asia and its affiliated colleges produced many leading figures of South Asia. It is the centre of the Indian Bengali film industry, which is known as Tollywood. Among scientific institutions, Kolkata hosts the Geological Survey of India, the Botanical Survey of India, the Calcutta Mathematical Society, the Indian Science Congress Association, the Zoological Survey of India, the Horticultural Society, the Institution of Engineers, the Anthropological Survey of India and the Indian Public Health Association. The Port of Kolkata is India's oldest operating port. Four Nobel laureates and two Nobel Memorial Prize winners are associated with the city.[19] Though home to major cricketing venues and franchises, Kolkata stands out in India for being the country's centre of association football. Kolkata is known for its grand celebrations of the Hindu festival of Durga Puja, which is recognized by UNESCO for its importance to world heritage.[20] Kolkata is also known as the 'City of Joy'.[21]

أصل الاسم

The word Kolkata (بالبنغالية: কলকাতা [kolˈkata]) derives from Kôlikata (بالبنغالية: কলিকাতা [ˈkɔliˌkata]), the Bengali language name of one of three villages that predated the arrival of the British; the other two villages were Sutanuti and Govindapur.[22]

There are several explanations for the etymology of this name:

- Kolikata is thought to be a variation of Kalikkhetrô (بالبنغالية: কালীক্ষেত্র [ˈkaliˌkʰetrɔ]), meaning 'Field of [the goddess] Kali'. Similarly, it can be a variation of Kalikshetra (Sanskrit: कालीक्षेत्र, lit. 'area of Goddess Kali').

- Another theory is that the name derives from Kalighat.[23]

- Alternatively, the name may have been derived from the Bengali term kilkila (بالبنغالية: কিলকিলা), or 'flat area'.[24]

- The name may have its origin in the words khal (بالبنغالية: খাল [ˈkʰal]) meaning 'canal', followed by kaṭa (بالبنغالية: কাটা [ˈkaʈa]), which may mean 'dug'.[25]

- According to another theory, the area specialised in the production of quicklime or koli chun (بالبنغالية: কলি চুন [ˈkɔliˌtʃun]) and coir or kata (بالبنغالية: কাতা [ˈkata]); hence, it was called Kolikata).[24]

Although the city's name has always been pronounced Kolkata or Kôlikata in Bengali, the anglicised form Calcutta was the official name until 2001, when it was changed to Kolkata in order to match Bengali pronunciation.[26]

التاريخ

The discovery and archaeological study of Chandraketugarh, 35 km (22 mi) north of Kolkata, provide evidence that the region in which the city stands has been inhabited for over two millennia.[27][28] Kolkata or Kalikata in its earliest mentions, is described to be a village surrounded with jungle on the bank of river Ganga as a renowned port, commercial hub and a hindu pilgrimage site for Kalighat Temple. The first mention of the Kalikata village was found in Bipradas Pipilai's Manasa Vijay (1495), where he describes how Chand Sadagar used to stop in Kalighat to worship Goddess Kali during his path to trade voyage.[29][30] Later Kalikata was also found to be mentioned in Mukundaram Chakrabarti's Chandimangal (1594), Todar Mal's taxation-list in 1596 and Krishnaram Das's Kalikamangal (1676-77).[30][31] Kalighat was then considered a safe place for businessmen. They used to carry on trade through the Bhagirathi and took shelter there at night.[32] Kolkata's recorded history began in 1690 with the arrival of the English East India Company, which was consolidating its trade business in Bengal. Job Charnock is often regarded as the founder of the city;[33] however, in response to a public petition,[34] the Calcutta High Court ruled in 2003 that the city does not have a founder.[35] The area occupied by the present-day city encompassed three villages: Kalikata, Gobindapur and Sutanuti. Kalikata was a fishing village, where a handful of merchants began their operations by building a factory;[32] Sutanuti was a riverside weavers' village; and Gobindapur was a trading post for Indian merchant princes. These villages were part of an estate belonging to the Sabarna Roy Choudhury family of zamindars. The estate was sold to the East India Company in 1698.[36]

أنشأت شركة الهند الشرقية البريطانية، وهي شركة إنجليزية، مدينة كلكتا عام 1690م، ثم أصبحت كلكتا عاصمة للهند عام 1773م. وبحلول القرن العشرين كانت كلكتا ثانية كبريات مدن الإمبراطورية البريطانية بعد مدينة لندن. وانتقلت العاصمة الهندية إلى دلهي عام 1912م لموقعها في وسط البلاد. وشهدت كلكتا عام 1946م، قبيل انفصال باكستان عن الهند، معارك طاحنة بين المسلمين والهندوس.

In 1712, the British completed the construction of Fort William, located on the east bank of the Hooghly River to protect their trading factory.[37] Facing frequent skirmishes with French forces, the British began to upgrade their fortifications in 1756. The Nawab of Bengal, Siraj-ud-Daulah, condemned the militarisation and tax evasion by the company. His warning went unheeded, and the Nawab attacked; his capture of Fort William led to the killings of several East India company officials in the Black Hole of Calcutta.[38] A force of Company soldiers (sepoys) and British troops led by Robert Clive recaptured the city the following year.[38] Per the 1765 Treaty of Allahabad following the battle of Buxar, East India company was appointed imperial tax collector of the Mughal emperor in the province of Bengal, Bihar and Orissa, while Mughal-appointed Nawabs continued to rule the province.[39] Declared a presidency city, Calcutta became the headquarters of the East India Company by 1773.[40]

In 1793, ruling power of the Nawabs were abolished, and East India company took complete control of the city and the province. In the early 19th century, the marshes surrounding the city were drained; the government area was laid out along the banks of the Hooghly River. Richard Wellesley, Governor-General of the Presidency of Fort William between 1797 and 1805, was largely responsible for the development of the city and its public architecture.[41] Throughout the late 18th and 19th century, the city was a centre of the East India Company's opium trade.[42] A census in 1837 records the population of the city proper as 229,700, of which the British residents made up only 3,138.[43] The same source says another 177,000 resided in the suburbs and neighbouring villages, making the entire population of greater Calcutta 406,700.

In 1864, a typhoon struck the city and killed about 60,000 in Kolkata.[44]

By the 1850s, Calcutta had two areas: White Town, which was primarily British and centred on Chowringhee and Dalhousie Square; and Black Town, mainly Indian and centred on North Calcutta.[45] The city underwent rapid industrial growth starting in the early 1850s, especially in the textile and jute industries; this encouraged British companies to massively invest in infrastructure projects, which included telegraph connections and Howrah railway station. The coalescence of British and Indian culture resulted in the emergence of a new babu class of urbane Indians, whose members were often bureaucrats, professionals, newspaper readers, and Anglophiles; they usually belonged to upper-caste Hindu communities.[46] In the 19th century, the Bengal Renaissance brought about an increased sociocultural sophistication among city denizens. In 1883, Calcutta was host to the first national conference of the Indian National Association, which was the first avowed nationalist organisation in India.[47]

The partition of Bengal in 1905 along religious lines led to mass protests, making Calcutta a less hospitable place for the British.[48][49] The capital was moved to New Delhi in 1911.[50] Calcutta continued to be a centre for revolutionary organisations associated with the Indian independence movement. The city and its port were bombed several times by the Japanese between 1942 and 1944, during World War II.[51][52] Millions starved to death during the Bengal famine of 1943 (at the same time of the war) due to a combination of military, administrative, and natural factors.[53] Demands for the creation of a Muslim state led in 1946 to an episode of communal violence that killed over 4,000.[54][55][56] The partition of India led to further clashes and a demographic shift—many Muslims left for East Bengal (later East Pakistan, present day Bangladesh), while hundreds of thousands of Hindus fled into the city.[57]

During the 1960s and 1970s, severe power shortages, strikes and a violent Marxist–Maoist movement by groups known as the Naxalites damaged much of the city's infrastructure, resulting in economic stagnation.[15] During East Pakistan's secessionist war of independence in 1971, the city was home to the government-in-exile of Bangladesh.[16] During the war, refugees poured into West Bengal and strained Kolkata's infrastructure.[58] The Eastern Command of the Indian military, which is based in Fort William, played a pivotal role in the Indo-Pakistani War of 1971 and securing the surrender of Pakistan. During the mid-1980s, Mumbai (then called Bombay) overtook Kolkata as India's most populous city. In 1985, Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi dubbed Kolkata a "dying city" in light of its socio-political woes.[59] In the period 1977–2011, West Bengal was governed from Kolkata by the Left Front, which was dominated by the Communist Party of India (CPM). It was the world's longest-serving democratically elected communist government, during which Kolkata was a key base for Indian communism.[60][61][62] The city's economic recovery gathered momentum after the 1990s, when India began to institute pro-market reforms. Since 2000, the information technology (IT) services sector has revitalised Kolkata's stagnant economy. The city is also experiencing marked growth in its manufacturing base. In the 2011 West Bengal Legislative Assembly election, Left Front was defeated by the Trinamool Congress.[63]

Geography

Spread roughly north–south along the east bank of the Hooghly River, Kolkata sits within the lower Ganges Delta of eastern India approximately 75 km (47 mi) west of the international border with Bangladesh; the city's elevation is 1.5–9 m (5–30 ft).[64] Much of the city was originally a wetland that was reclaimed over the decades to accommodate a burgeoning population.[65] The remaining undeveloped areas, known as the East Kolkata Wetlands, were designated a "wetland of international importance" by the Ramsar Convention (1975).[66] As with most of the Indo-Gangetic Plain, the soil and water are predominantly alluvial in origin. Kolkata is located over the "Bengal basin", a pericratonic tertiary basin.[67] Bengal basin comprises three structural units: shelf or platform in the west; central hinge or shelf/slope break; and deep basinal part in the east and southeast. Kolkata is located atop the western part of the hinge zone which is about 25 km (16 mi) wide at a depth of about 45،000 m (148،000 ft) below the surface.[67] The shelf and hinge zones have many faults, among them some are active. Total thickness of sediment below Kolkata is nearly 7،500 m (24،600 ft) above the crystalline basement; of these the top 350–450 m (1،150–1،480 ft) is Quaternary, followed by 4،500–5،500 m (14،760–18،040 ft) of Tertiary sediments, 500–700 m (1،640–2،300 ft) trap wash of Cretaceous trap and 600–800 m (1،970–2،620 ft) Permian-Carboniferous Gondwana rocks.[67] The quaternary sediments consist of clay, silt and several grades of sand and gravel. These sediments are sandwiched between two clay beds: the lower one at a depth of 250–650 m (820–2،130 ft); the upper one 10–40 m (30–130 ft) in thickness.[68] According to the Bureau of Indian Standards, on a scale ranging from I to V in order of increasing susceptibility to earthquakes, the city lies inside seismic zone III.[69]

Climate

Kolkata is subject to a tropical wet-and-dry climate that is designated Aw under the Köppen climate classification. According to a United Nations Development Programme report, its wind and cyclone zone is "very high damage risk".[69]

Temperature

The annual mean temperature is 26.8 °C (80.2 °F); monthly mean temperatures are 19–30 °C (66–86 °F). Summers (March–June) are hot and humid, with temperatures in the low 30s Celsius; during dry spells, maximum temperatures sometime exceed 40 °C (104 °F) in May and June.[70] Winter lasts for roughly 21⁄2 months, with seasonal lows dipping to 9–11 °C (48–52 °F) in December and January. May is the hottest month, with daily temperatures ranging from 27–37 °C (81–99 °F); January, the coldest month, has temperatures varying from 12–23 °C (54–73 °F). The highest recorded temperature is 43.9 °C (111.0 °F), and the lowest is 5 °C (41 °F).[70] The winter is mild and very comfortable weather pertains over the city throughout this season. Often, in April–June, the city is struck by heavy rains or dusty squalls that are followed by thunderstorms or hailstorms, bringing cooling relief from the prevailing humidity. These thunderstorms are convective in nature, and are known locally as kal bôishakhi (কালবৈশাখী), or "Nor'westers" in English.[71]

Rainfall

Rains brought by the Bay of Bengal branch of the south-west summer monsoon[72] lash Kolkata between June and September, supplying it with most of its annual rainfall of about 1،850 mm (73 in). The highest monthly rainfall total occurs in July and August. In these months often incessant rain for days brings life to a stall for the city dwellers. The city receives 2,107 hours of sunshine per year, with maximum sunlight exposure occurring in April.[73] Kolkata has been hit by several cyclones; these include systems occurring in 1737 and 1864 that killed thousands.[74][75] More recently, Cyclone Aila in 2009 and Cyclone Amphan in 2020 caused widespread damage to Kolkata by bringing catastrophic winds and torrential rainfall.

Environmental issues

Pollution is a major concern in Kolkata. اعتبارا من 2008[تحديث], sulphur dioxide and nitrogen dioxide annual concentration were within the national ambient air quality standards of India, but respirable suspended particulate matter levels were high, and on an increasing trend for five consecutive years, causing smog and haze.[76][77] Severe air pollution in the city has caused a rise in pollution-related respiratory ailments, such as lung cancer.[78]

Cityscape and urban structure

Kolkata, which is under the jurisdiction of the Kolkata Municipal Corporation (KMC), has an area of 206.08 km2 (80 sq mi).[79] The east–west dimension of the city is comparatively narrow, stretching from the Hooghly River in the west to roughly the Eastern Metropolitan Bypass in the east—a span of 9–10 km (5.6–6.2 mi).[80] The north–south distance is greater, and its axis is used to section the city into North, Central, South and East Kolkata. North Kolkata is the oldest part of the city. Characterised by 19th-century architecture and narrow alleyways, it includes areas such as Jorasanko, Rajabazar, Maniktala, Ultadanga, Shyambazar, Shobhabazar, Bagbazar, Cossipore, Sinthee etc. The north suburban areas like Dum Dum, Baranagar, Belgharia, Sodepur, Khardaha, New Barrackpore, Madhyamgram, Barrackpore, Barasat etc. are also within the city of Kolkata (as a metropolitan structure).[81] Central Kolkata hosts the central business district. It contains B. B. D. Bagh, formerly known as Dalhousie Square, and the Esplanade on its east; Rajiv Gandhi Sarani is on its west.[82] The West Bengal Secretariat, General Post Office, Reserve Bank of India, Calcutta High Court, Lalbazar Police Headquarters and several other government and private offices are located there. Another business hub is the area south of Park Street, which comprises thoroughfares such as Jawahar Lal Nehru Road, Abanindra Nath Tagore Sarani, Dr. Martin Luther King Sarani, Dr. Upendra Nath Brahmachari Sarani, Shakespeare Sarani and Acharay Jagadish Chandra Basu Road.[83]

South Kolkata developed after India gained independence in 1947; it includes upscale neighbourhoods such as Bhowanipore, Alipore, Ballygunge, Kasba, Dhakuria, Santoshpur, Garia, Golf Green, Tollygunge, New Alipore, Behala, Barisha etc. The south suburban areas like Maheshtala, Budge Budge, Rajpur Sonarpur, Baruipur etc. are also within the city of Kolkata (as a metropolitan structure).[22] The Maidan is a large open field in the heart of the city that has been called the "lungs of Kolkata"[84] and accommodates sporting events and public meetings.[85] The Victoria Memorial and Kolkata Race Course are located at the southern end of the Maidan. Among the other parks are Central Park in Bidhannagar and Millennium Park on Rajiv Gandhi Sarani, along the Hooghly River.

الاقتصاد

يُستخدم العمال في عمليات توزيع وبيع المنتجات الصناعية، ويخدم ميناء كلكتا 10% من التجارة الخارجية، ونحو ثلث المصارف الأجنبية، يوجد في المدينة أيضا مقر رئاسة الغرفة التجارية الهندية. تمتاز كلكتا بصناعة الجوت لصناعة الجوالات، والصناعات الهندسية، وصناعة المنتجات الاستهلاكية، وصناعة الأحذية بجانب تعدين الفحم الحجري والحديد والمنجنيز والبترول. وعلى الرغم من تعدد الصناعات إلا أن المدينة تعاني من مشكلة البطالة.

الإدارة المدنية

كلكتا عاصمة ولاية البنغال الغربية، ومقر حاكم الولاية والمجلس التشريعي ودواوين الحكومة والمحكمة العليا، كما أنها مقر عدد من المؤسسات القومية، مثل المكتبة القومية ومؤسسة المسوحات الجيولوجية ومصلحة الأرصاد الجوية. ويقوم بالإشراف على الإدارة المحلية بالمدينة هيئة البلديات، والتي تتكون من 100 عضو، وهذه الهيئة تنتخب العمدة واللجان، كما تشرف على المحافظ الذي يقوم بتنسيق الخدمات العامة بالمدينة.

خدمات المرافق ووسائل الإعلام

النقل

التوزيع السكانى

الثقافة

اللغة والدين. يدين نحو 80% من سكان كلكتا بالديانة الهندوسية، واللغة الرسمية هي لغة البنغال، كما تتحدث الأقليات بالمدينة 60 لغة مختلفة. يُعدّ المسلمون أكبر الأقليات الدينية بالمدينة (15% من عدد السكان) بجانب النصارى والسيخ واليانيين والبوذيين.

التعليم

الرياضة

المدن الشقيقة

بنگلادش: Dhaka[86]

بنگلادش: Dhaka[86] الصين: Kunming (October 2013)[86][87]

الصين: Kunming (October 2013)[86][87] اليونان: Thessaloniki (21 January 2005)[86][88]

اليونان: Thessaloniki (21 January 2005)[86][88] إيطاليا: Naples[86]

إيطاليا: Naples[86] پاكستان: Karachi[89]

پاكستان: Karachi[89] كوريا الجنوبية: Incheon[86][90]

كوريا الجنوبية: Incheon[86][90] أوكرانيا: Odessa[86][91]

أوكرانيا: Odessa[86][91] الولايات المتحدة:

الولايات المتحدة:

هامش

|

المراجع

|

|

وصلات خارجية

| هذه المقالة تحتوي نص هندي. بدون دعم الإظهار لتلك الأبجديات، فقد ترى علامات استفهام أو مربعات أو رموز أخرى بدلاً من الحروف الهندية؛ أو وضع غير منتظم للحروف المتحركة وفقدان لعلامات الوصل. |

![]() تعريفات قاموسية في ويكاموس

تعريفات قاموسية في ويكاموس

![]() كتب من معرفة الكتب

كتب من معرفة الكتب

![]() اقتباسات من معرفة الاقتباس

اقتباسات من معرفة الاقتباس

![]() نصوص مصدرية من معرفة المصادر

نصوص مصدرية من معرفة المصادر

![]() صور و ملفات صوتية من كومونز

صور و ملفات صوتية من كومونز

![]() أخبار من معرفة الأخبار.

أخبار من معرفة الأخبار.

- كلكتا at the Open Directory Project

- Durga Puja 2007 Kolkata

- Kolkata Football Daily News

- Kolkata Municipal Corporation

- Kolkata Municipal Development Authority

- West Bengal Government

- Kolkata City Information

- كلكتا travel guide from Wikitravel

- CS1 Bengali-language sources (bn)

- CS1 maint: location missing publisher

- CS1 الإنجليزية الأمريكية-language sources (en-us)

- CS1 errors: unsupported parameter

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Pages using infobox settlement with possible nickname list

- Pages using gadget WikiMiniAtlas

- Pages using infobox settlement with unknown parameters

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Articles containing بنغالي-language text

- Pages with plain IPA

- مقالات فيها عبارات متقادمة منذ 2008

- جميع المقالات التي فيها عبارات متقادمة

- كبرى مدن الهند

- مدن الهند

- كلكتا

- مدن عواصم هندية

- مدن وبلدات في غرب البنغال

- منطقة السكك الحديدية الشرقية (الهند)

- منطقة السكك الحديدية الجنوبية (الهند)

- عواصم وطنية سابقة

- صفحات مع الخرائط