علم الكون الطبيعي

| جزء من سلسلة عن |

| علم الكون الطبيعي |

|---|

|

علم الكون الطبيعي كأحد فروع الفيزياء الفلكية هو دراسة البنية الواسعة النطاق للفضاء الكوني ، يهتم علم الكون الفيزيائي بالإجابة عن الأسئلة الأساسية التي تخص الكون و وجوده و تشكله و تطوره . كما يتدخل علم الكون الفيزيائي بدراسة حركات الأجسام النجمية و المسبب الأول first cause . هذه الأسئلة و المجالات كانت لفترة طويلة من اختصاص الفلسفة و تحديدا علم ما بعد الطبيعة أو الميتافيزيكيا ، لكن منذ عهد كوبرنيك ، أصبح العلم هو من يحدد كيفية حركة النجوم و مداراتها و ليس التفكير الفلسفي .

التطور الفعلي لفهم الكون بدأ في القرن العشرين بعد ظهور نظريتي النسبية لآينشتاين و تحديدا النسبية العامة التي تتحدث عن شكل الفضاء الكوني و هندسته ، خصوصا بعد التنبؤات الدقيقة التي أكدتها الأرصاد فيما بعد .

تاريخ موضوعي

−13 — – −12 — – −11 — – −10 — – −9 — – −8 — – −7 — – −6 — – −5 — – −4 — – −3 — – −2 — – −1 — – 0 — |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Modern cosmology developed along tandem tracks of theory and observation. In 1916, Albert Einstein published his theory of general relativity, which provided a unified description of gravity as a geometric property of space and time.[1] At the time, Einstein believed in a static universe, but found that his original formulation of the theory did not permit it.[2] This is because masses distributed throughout the universe gravitationally attract, and move toward each other over time.[3] However, he realized that his equations permitted the introduction of a constant term which could counteract the attractive force of gravity on the cosmic scale. Einstein published his first paper on relativistic cosmology in 1917, in which he added this cosmological constant to his field equations in order to force them to model a static universe.[4] The Einstein model describes a static universe; space is finite and unbounded (analogous to the surface of a sphere, which has a finite area but no edges). However, this so-called Einstein model is unstable to small perturbations—it will eventually start to expand or contract.[2] It was later realized that Einstein's model was just one of a larger set of possibilities, all of which were consistent with general relativity and the cosmological principle. The cosmological solutions of general relativity were found by Alexander Friedmann in the early 1920s.[5] His equations describe the Friedmann–Lemaître–Robertson–Walker universe, which may expand or contract, and whose geometry may be open, flat, or closed.

In the 1910s, Vesto Slipher (and later Carl Wilhelm Wirtz) interpreted the red shift of spiral nebulae as a Doppler shift that indicated they were receding from Earth.[9][10] However, it is difficult to determine the distance to astronomical objects. One way is to compare the physical size of an object to its angular size, but a physical size must be assumed to do this. Another method is to measure the brightness of an object and assume an intrinsic luminosity, from which the distance may be determined using the inverse-square law. Due to the difficulty of using these methods, they did not realize that the nebulae were actually galaxies outside our own Milky Way, nor did they speculate about the cosmological implications. In 1927, the Belgian Roman Catholic priest Georges Lemaître independently derived the Friedmann–Lemaître–Robertson–Walker equations and proposed, on the basis of the recession of spiral nebulae, that the universe began with the "explosion" of a "primeval atom"[11]—which was later called the Big Bang. In 1929, Edwin Hubble provided an observational basis for Lemaître's theory. Hubble showed that the spiral nebulae were galaxies by determining their distances using measurements of the brightness of Cepheid variable stars. He discovered a relationship between the redshift of a galaxy and its distance. He interpreted this as evidence that the galaxies are receding from Earth in every direction at speeds proportional to their distance.[12] This fact is now known as Hubble's law, though the numerical factor Hubble found relating recessional velocity and distance was off by a factor of ten, due to not knowing about the types of Cepheid variables.

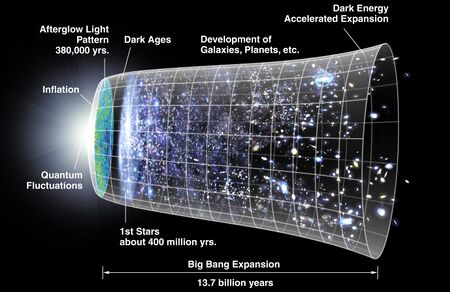

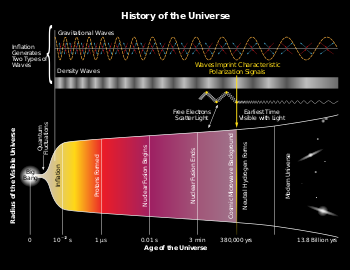

Given the cosmological principle, Hubble's law suggested that the universe was expanding. Two primary explanations were proposed for the expansion. One was Lemaître's Big Bang theory, advocated and developed by George Gamow. The other explanation was Fred Hoyle's steady state model in which new matter is created as the galaxies move away from each other. In this model, the universe is roughly the same at any point in time.[13][14]

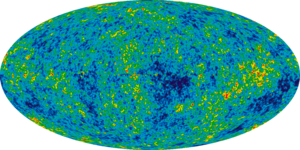

For a number of years, support for these theories was evenly divided. However, the observational evidence began to support the idea that the universe evolved from a hot dense state. The discovery of the cosmic microwave background in 1965 lent strong support to the Big Bang model,[14] and since the precise measurements of the cosmic microwave background by the Cosmic Background Explorer in the early 1990s, few cosmologists have seriously proposed other theories of the origin and evolution of the cosmos. One consequence of this is that in standard general relativity, the universe began with a singularity, as demonstrated by Roger Penrose and Stephen Hawking in the 1960s.[15]

An alternative view to extend the Big Bang model, suggesting the universe had no beginning or singularity and the age of the universe is infinite, has been presented.[16][17][18]

انظر أيضاً

المراجع

- ^ "Nobel Prize Biography". Nobel Prize. Retrieved 25 February 2011.

- ^ أ ب Liddle, A. (2003). An Introduction to Modern Cosmology. Wiley. p. 51. ISBN 978-0-470-84835-7.

- ^ Vilenkin, Alex (2007). Many worlds in one: the search for other universes. New York: Hill and Wang, A division of Farrar, Straus and Giroux. p. 19. ISBN 978-0-8090-6722-0.

- ^ Jones, Mark; Lambourne, Robert (2004). An introduction to galaxies and cosmology. Milton Keynes Cambridge, UK; New York: Open University Cambridge University Press. p. 228. ISBN 978-0-521-54623-2.

- ^ Jones, Mark; Lambourne, Robert (2004). An introduction to galaxies and cosmology. Milton Keynes Cambridge, UK; New York: Open University Cambridge University Press. p. 232. ISBN 978-0-521-54623-2.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةBICEP2-2014 - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةNASA-20140317 - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةNYT-20140317 - ^ Slipher, V. M. (1922). "Further Notes on Spectrographic Observations of Nebulae and Clusters". Publications of the American Astronomical Society. 4: 284–286. Bibcode:1922PAAS....4..284S.

- ^ Seitter, Waltraut C.; Duerbeck, Hilmar W. (1999). Egret, Daniel; Heck, Andre (eds.). Carl Wilhelm Wirtz – Pioneer in Cosmic Dimensions. ASP Conference Series. Vol. 167. pp. 237–242. Bibcode:1999ASPC..167..237S. ISBN 978-1-886733-88-6.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - ^ Lemaître, G. (1927). "Un Univers homogène de masse constante et de rayon croissant rendant compte de la vitesse radiale des nébuleuses extra-galactiques". Annales de la Société Scientifique de Bruxelles (in الفرنسية). A47: 49–59. Bibcode:1927ASSB...47...49L.

- ^ Hubble, Edwin (March 1929). "A Relation between Distance and Radial Velocity among Extra-Galactic Nebulae". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 15 (3): 168–173. Bibcode:1929PNAS...15..168H. doi:10.1073/pnas.15.3.168. PMC 522427. PMID 16577160.

- ^ Hoyle, F. (1948). "A New Model for the Expanding Universe". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 108 (5): 372–382. Bibcode:1948MNRAS.108..372H. doi:10.1093/mnras/108.5.372.

- ^ أ ب "Big Bang or Steady State?". Ideas of Cosmology. American Institute of Physics. Archived from the original on 12 June 2015. Retrieved 2015-07-29.

- ^ Earman, John (1999). Goenner, Hubert; Jürgen; Ritter, Jim; Sauer, Tilman (eds.). The Penrose-Hawking Singularity Theorems: History and Implications – The expanding worlds of general relativity. Birk presentations of the fourth conference on the and gravitation. pp. 235–267. Bibcode:1999ewgr.book..235E. doi:10.1007/978-1-4612-0639-2_7. ISBN 978-1-4612-6850-5.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - ^ Ghose, Tia (26 February 2015). "Big Bang, Deflated? Universe May Have Had No Beginning". Live Science. Retrieved 28 February 2015.

- ^ Ali, Ahmed Faraq (4 February 2015). "Cosmology from quantum potential". Physics Letters B. 741 (2015): 276–279. arXiv:1404.3093. Bibcode:2015PhLB..741..276F. doi:10.1016/j.physletb.2014.12.057. S2CID 55463396.

- ^ Das, Saurya; Bhaduri, Rajat K (21 May 2015). "Dark matter and dark energy from a Bose–Einstein condensate". Classical and Quantum Gravity. 32 (10): 105003. arXiv:1411.0753. Bibcode:2015CQGra..32j5003D. doi:10.1088/0264-9381/32/10/105003. S2CID 119247745.

للاستزادة

للعامة

- Greene, Brian (2005). The Fabric of the Cosmos. Penguin Books Ltd. ISBN 978-0-14-101111-0.

- Guth, Alan (1997). The Inflationary Universe: The Quest for a New Theory of Cosmic Origins. Random House. ISBN 978-0-224-04448-6.

- Hawking, Stephen W. (1988). A Brief History of Time: From the Big Bang to Black Holes. Bantam Books, Inc. ISBN 978-0-553-38016-3.

- Hawking, Stephen W. (2001). The Universe in a Nutshell. Bantam Books, Inc. ISBN 978-0-553-80202-3.

- Ostriker, Jeremiah P.; Mitton, Simon (2013). Heart of Darkness: Unraveling the mysteries of the invisible Universe. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-13430-7.

- Singh, Simon (2005). Big Bang: The Origin of the Universe. Fourth Estate. Bibcode:2004biba.book.....S. ISBN 978-0-00-716221-5.

- Weinberg, Steven (1993) [First published 1978]. The First Three Minutes. Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-02437-7.

مراجع

- Cheng, Ta-Pei (2005). Relativity, Gravitation and Cosmology: a Basic Introduction. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-852957-6. Introductory cosmology and general relativity without the full tensor apparatus, deferred until the last part of the book.

- Dodelson, Scott (2003). Modern Cosmology. Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-219141-1. An introductory text, released slightly before the WMAP results.

- Gal-Or, Benjamin (1987) [1981]. Cosmology, Physics and Philosophy. Springer Verlag. ISBN 0-387-90581-2.

- Grøn, Øyvind; Hervik, Sigbjørn (2007). Einstein's General Theory of Relativity with Modern Applications in Cosmology. New York: Springer. ISBN 978-0-387-69199-2.

- Harrison, Edward (2000). Cosmology: the science of the universe. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-66148-5. For undergraduates; mathematically gentle with a strong historical focus.

- Kutner, Marc (2003). Astronomy: A Physical Perspective. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-52927-3. An introductory astronomy text.

- Kolb, Edward; Michael Turner (1988). The Early Universe. Addison-Wesley. ISBN 978-0-201-11604-5. The classic reference for researchers.

- Liddle, Andrew (2003). An Introduction to Modern Cosmology. John Wiley. ISBN 978-0-470-84835-7. Cosmology without general relativity.

- Liddle, Andrew; David Lyth (2000). Cosmological Inflation and Large-Scale Structure. Cambridge. ISBN 978-0-521-57598-0. An introduction to cosmology with a thorough discussion of inflation.

- Mukhanov, Viatcheslav (2005). Physical Foundations of Cosmology. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-56398-7.

- Padmanabhan, T. (1993). Structure formation in the universe. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-42486-8. Discusses the formation of large-scale structures in detail.

- Peacock, John (1998). Cosmological Physics. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-42270-3. An introduction including more on general relativity and quantum field theory than most.

- Peebles, P. J. E. (1993). Principles of Physical Cosmology. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-01933-8. Strong historical focus.

- Peebles, P. J. E. (1980). The Large-Scale Structure of the Universe. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-08240-0. The classic work on large-scale structure and correlation functions.

- Rees, Martin (2002). New Perspectives in Astrophysical Cosmology. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-64544-7.

- Weinberg, Steven (1971). Gravitation and Cosmology. John Wiley. ISBN 978-0-471-92567-5. A standard reference for the mathematical formalism.

- Weinberg, Steven (2008). Cosmology. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-852682-7.

وصلات خارجية

| علم الكون الطبيعي

]].من جماعات

- Cambridge Cosmology – from Cambridge University (public home page)

- Cosmology 101 – from the NASA WMAP group

- Center for Cosmological Physics. University of Chicago, Chicago.

- Origins, Nova Online – Provided by PBS.

من أفراد

- Gale, George, "Cosmology: Methodological Debates in the 1930s and 1940s", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Edward N. Zalta (ed.)

- Madore, Barry F., "Level 5 : A Knowledgebase for Extragalactic Astronomy and Cosmology". Caltech and Carnegie. Pasadena, California.

- Tyler, Pat, and Phil Newman "Beyond Einstein". Laboratory for High Energy Astrophysics (LHEA) NASA Goddard Space Flight Center.

- Wright, Ned. "Cosmology tutorial and FAQ". Division of Astronomy & Astrophysics, UCLA.

- George Musser (February 2004). "Four Keys to Cosmology". Scientific American. Scientific American. Retrieved 22 March 2015.

- Cliff Burgess; Fernando Quevedo (November 2007). "The Great Cosmic Roller-Coaster Ride". Scientific American (print). pp. 52–59.

(subtitle) Could cosmic inflation be a sign that our universe is embedded in a far vaster realm?

- CS1 errors: periodical ignored

- CS1 الفرنسية-language sources (fr)

- Short description with empty Wikidata description

- Pages using sidebar with the child parameter

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- ارتياد الفضاء

- Physical cosmology

- Philosophy of physics

- Philosophy of time

- Astronomical sub-disciplines

- Astrophysics

- علم الكون

- فيزياء فلكية