خفاش حدوة الحصان

| خفاش حدوة الحصان | |

|---|---|

| |

| خفاش حدوة الحصان الصغرى (Rhinolophus hipposideros) مميز بالأزرق اللامع على الجناح الأيسر | |

| التصنيف العلمي | |

| أصنوفة غير معروفة (أصلحها): | Rhinolophus |

| Type species | |

| خفاش حدوة الحصان الكبرى شربر، 1774

| |

| الأنواع | |

خفافيش حدوة الحصان (إنگليزية: Horseshoe bats، هي خفافيش ضمن فصيلة حدوة الحصان. بالإضافة لكونها الجنس الوحيد الحي، تضم هذه الفصيلة حوالي 105 نوع، أما الجنس المنقرض Palaeonycteris، فتم التعرف عليه أيضاً. ترتبط خفافيش حدوة الحصان بشكل كبير بفصيلة خفافيش العالم القديم ذات الأنف الورقي، التي يتم تضمينها أحياناً ضمن خفافيش حدوة الحصان. تنقسم خفافيش حدوة الحصان إلى ستة أ<ناس فرعية والكثير من مجموعات الأنواع. عاش أحدث سلف مشترك لجميع خفافيش حدوة الحصان منذ 34-40 مليون سنة، على الرغم من أنه من غير الواضح موقع الجذور الجغرافية للعائلة، وكانت محاولات تحديد الجغرافيا الحيوية غير حاسمة. التصنيف معقد، حيث يُظهر الدليل الجيني احتمال وجود العديد من الأنواع المشفرة، بالإضافة إلى الأنواع المعترف بها على أنها متميزة والتي قد يكون تتمتع بالقليل من الاختلاف الجيني عن الأنواع المعترف بها سابقًا. تتواجد في العالم القديم، معظمها في المناطق الإستوائية أو شبه الإستوائية، بما في ذلك أفريقيا وآسيا وأوروپا وأوقيانوسيا.

تعتبر خفافيش حدوة الحصان خفافيش صغيرة أو [[خفاش صغير|متوسطة الحجم، تزن 4–28 گرام، ويصل طول جناحها إلى 30–75 ملي، وطول الرأس والجسم 35-110 ملي. يكتسي جسمها بفراء طويل وناعم في معظم الأنواع، ويكون بلون بني محمر أو مسود أو برتقالي مائل إلى الأحمر الفاتح. اكتسبت اسمها الشائع من الأنف-ورقي الشكل الكبير، والذي يشبه حدوة الحصان. تساعد الأنف الورقية الشكل في تحديد الموقع بالصدى؛ تتميز خفافيش حدوة الحصان بقدرتها على تحديد الموقع بالصدى بدرجة عالية من التعقيد، وذلك باستخدام نداءات التردد المستمر في دورة العمل العالية للكشف عن الفرائس في المناطق ذات الضوضاء البيئي العالية. تصطاد الحشرات والعناكب، وتنقض على الفريسة من الفرخ، أو تلتقط من أوراق الشجر. لا يُعرف سوى القليل عن أنظمة التزاوج الخاصة بها، ولكن نوعًا واحدًا على الأقل هو أحادي الزوج، في حين أن هناك نوعاً آخرمتعدد الزوج. يستمر الحمل حوالي سبعة أسابيع وينتج نسل واحد في كل مرة. العمر النموذجي هو ست أو سبع سنوات، لكن هناك خفاش حدوة حصان كبرى عاش أكثر من ثلاثين عامًا.

تعتبر خفافيش حدوة الحصان ذات صلة بالبشر في بعض المناطق مصدراً للأمراض، مثل الأغذية، و الطب التقليدي. العديد من خفافيش حدوة الحصان هي مستودعات طبيعية ڤيروس-كورونا-سارس، على الرغم من أن زباد النخيل المقنع كان العائل الوسيط الذي من خلاله أصيب البشر بالعدوى. تشير بعض الأدلة إلى أن بعض الأنواع يمكن أن تكون المستودع الطبيعي سارس-كوڤ-2، الذي يسبب كوڤيد-19. يتم اصطيادها للحصول كمصدر للطعام في عدة مناطق، ولا سيما أفريقيا جنوب الصحراء، وفي جنوب شرق آسيا أيضاً. تُستخدم بعض أنواع خفافيش حدوة الحصان أو ذرقها في الطب التقليدي في نيپال والهند وڤيتنام والسنغال.

التصنيف والتطور

تاريخ التصنيف

وصف Rhinolophus في أول مرة لأول مرة كجنس في عام 1799 من قبل عالم الطبيعة الفرنسي برنار جيرمان دي لاسيپيد. في البداية، كانت جميع الخفافيش الموجودة ضمن جنس حدوة الحصان موجودة في "Rhinolophus" ، وكذلك الأنواع الموجودة حاليًا في "Hipposideros" (خفافيش الأوراق المستديرة).[1] ي البداية، كانت خفافيش حدوة الحصان ضمن فصيلة الخفافيش الليلية. عام 1925، قام عالم الحيوان البريطاني جون إدوارد گراي بتقسيم الفصيلة إلى تحت فصيلتين، تتضمن ما يسمى خفافيش حدوة الحصان.[2] يرجع الفضل لعالم الحيوان الإنگليزي توماس بل لكونه أول حدد خفافيش حدوة الحصان كفصيلة مستقلة، مستخدماً Rhinolophidae عام 1836.[3] بينما يعترف أحيانأً ببل كمؤلف للفصيلة،[4] فغالباً ما يمنح هذا لگراي 1825.[3][5] تتبع خفافيش حدوة الحصان الفصيلة الفرعية Rhinolophoidea، مع الفصائل الفرعية الأخرى الخفافيش الطنانة، خفافيش العالم القديم ورقية الأنف، خفافيش الشبح، Rhinonycteridae، وخفافيش ذيل الفأر.[6][7]

التاريخ التطوري

The most recent common ancestor of Rhinolophus lived an estimated 34–40 million years ago,[8] splitting from the hipposiderid lineage during the Eocene.[9] Fossilized horseshoe bats are known from Europe (early to mid-Miocene, early Oligocene), Australia (Miocene), and Africa (Miocene and late Pliocene).[10] The biogeography of horseshoe bats is poorly understood. Various studies have proposed that the family originated in Europe, Asia, or Africa. A 2010 study supported an Asian or Oriental origin of the family, with rapid evolutionary radiations of the African and Oriental clades during the Oligocene.[9] A 2019 study found that R. xinanzhongguoensis and R. nippon, both Eurasian species, are more closely related to African species than to other Eurasian species, suggesting that rhinolophids may have a complex biogeographical relationship with Asia and the Afrotropics.[8]

A 2016 study using mitochondrial and nuclear DNA placed the horseshoe bats within the Yinpterochiroptera as sister to Hipposideridae.[7]

| Chiroptera |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Rhinolophidae is represented by one extant genus, Rhinolophus. Both the family and the genus are confirmed as monophyletic (containing all descendants of a common ancestor). As of 2019, there were 106 described species in Rhinolophus, making it the second-most speciose genus of bat after Myotis. Rhinolophus may be undersampled in the Afrotropical realm, with one genetic study estimating that there could be up to twelve cryptic species in the region. Additionally, some taxa recognized as full species have been found to have little genetic divergence. Rhinolophus kahuzi may be a synonym for the Ruwenzori horseshoe bat (R. ruwenzorii), and R. gorongosae or R. rhodesiae may be synonyms of the Bushveld horseshoe bat (R. simulator). Additionally, Smithers's horseshoe bat (R. smithersi), Cohen's horseshoe bat (R. cohenae), and the Mount Mabu horseshoe bat (R. mabuensis) all have little genetic divergence from Hildebrandt's horseshoe bat (R. hildebrandtii). Recognizing the former three as full species leaves Hildebrandt's horseshoe bat paraphyletic.[8]

The second genus in Rhinolophidae is the extinct Palaeonycteris, with the type species Palaeonycteris robustus.[11] Palaeonycteris robustus lived during the Lower Miocene and its fossilized remains were found in Saint-Gérand-le-Puy, France.[12][13]

Description

Appearance

Horseshoe bats are considered small or medium microbats.[14] Individuals have a head and body length ranging 35–110 mm (1.4–4.3 in) and have forearm lengths of 30–75 mm (1.2–3.0 in). One of the smaller species, the lesser horseshoe bat (R. hipposideros), weighs 4–10 g (0.14–0.35 oz), while one of the larger species, the greater horseshoe bat (R. ferrumequinum), weighs 16.5–28 g (0.58–0.99 oz). Fur color is highly variable among species, ranging from blackish to reddish brown to bright orange-red.[15][10] The underparts are paler than the back fur.[15] The majority of species have long, soft fur, but the woolly and lesser woolly horseshoe bats (R. luctus and R. beddomei) are unusual in their very long, woolly fur.[10]

Like most bats, horseshoe bats have two mammary glands on their chests. Adult females additionally have two teat-like projections on their abdomens, called pubic nipples or false nipples, which are not connected to mammary glands. Only a few other bat families have pubic nipples, including Hipposideridae, Craseonycteridae, Megadermatidae, and Rhinopomatidae; they serve as attachment points for their offspring.[16] In a few horseshoe bat species, males have a false nipple in each armpit.[14]

Head and teeth

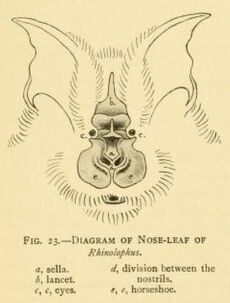

All horseshoe bats have large, leaf-like protuberances on their noses, which are called nose-leafs.[14] The nose-leafs are important in species identification, and are composed of several parts.[17] The front of the nose-leaf resembles and is called a horseshoe, earning them the common name of "horseshoe bats".[14] The horseshoe is above the upper lip and is thin and flat. The lancet is triangular, pointed, and pocketed, and points up between the bats' eyes.[17] The sella is a flat, ridge-like structure at the center of the nose. It rises from behind the nostrils and points out perpendicular from the head.[17] Their ears are large and leaf-shaped, nearly as broad as they are long, and lack tragi. The antitragi of the ears are conspicuous. Their eyes are very small.[14] The skull always has a rostral inflation, or bony protrusion on the snout. The typical dental formula of a horseshoe bat is 1.1.2.32.1.3.3, but the middle lower premolars are often missing, as well as the anterior upper premolars (premolars towards the front of the mouth).[1] The young lose their milk teeth while still in utero,[15] with the teeth resorbed into the body.[18] They are born with the four permanent canine teeth erupted, which enables them to cling to their mothers.[18] This is atypical among bat families, as most newborns have at least some milk teeth at birth, which are quickly replaced by the permanent set.[19]

Postcrania

Several bones in its thorax are fused—the presternum, first rib, partial second rib, seventh cervical vertebra, first thoracic vertebra—making a solid ring.[1] This fusion is associated with the ability to echolocate while stationary.[20] Except for the first digit, which has two phalanges,[15] all of their toes have three phalanges.[1] This distinguishes them from hipposiderids, which have two phalanges in all toes.[14] The tail is completely enclosed in the uropatagium (tail membrane),[1] and the trailing edge of the uropatagium has calcars (cartilaginous spurs).[14]

Biology and ecology

Echolocation and hearing

Horeshoe bats have very small eyes and their field of vision is limited by their large nose-leafs; thus, vision is unlikely to be a very important sense. Instead, they use echolocation to navigate,[10] employing some of the most sophisticated echolocation of any bat group.[21] To echolocate, they produce sound through their nostrils. While some bats use frequency-modulated echolocation, horseshoe bats use constant-frequency echolocation (also known as single-frequency echolocation).[22] They have high duty cycles, meaning that when individuals are calling, they are producing sound more than 30% of the time. The use of high duty, constant-frequency echolocation aids in distinguishing prey items based on size. These echolocation characteristics are typical of bats that search for moving prey items in cluttered environments full of foliage.[21] They echolocate at particularly high frequencies for bats, though not as high as hipposiderids relative to their body sizes, and the majority concentrate most of the echolocation energy into the second harmonic. The king horseshoe bat (R. rex) and the large-eared horseshoe bat (R. philippensis) are examples of outlier species that concentrate energy into the first harmonic rather than the second.[23] Their highly furrowed nose-leafs likely assist in focusing the emission of sound, reducing the effect of environmental clutter.[22] The nose-leaf in general acts like a parabolic reflector, aiming the produced sound while simultaneously shielding the ear from some of it.[14]

Horseshoe bats have sophisticated senses of hearing due to their well-developed cochlea,[14] and are able to detect Doppler-shifted echoes. This allows them to produce and receive sounds simultaneously.[1] Within horseshoe bats, there is a negative relationship between ear length and echolocation frequency: Species with higher echolocation frequencies tend to have shorter ear lengths.[23] During echolocation, the ears can move independently of each other in a "flickering" motion characteristic of the family, while the head simultaneously moves up and down or side to side.[14]

Diet and foraging

Horseshoe bats are insectivorous, though consume other arthropods such as spiders,[15] and employ two main foraging strategies. The first strategy is flying slow and low over the ground, hunting among trees and bushes. Some species who use this strategy are able to hover over prey and glean them from the substrate. The other strategy is known as perch feeding: Individuals roost on feeding perches and wait for prey to fly past, then fly out to capture it.[1] Foraging usually occurs 5.0–5.9 m (16.5–19.5 ft) above the ground.[10] While vesper bats may catch prey in their uropatagia and transfer it to their mouths, horseshoe bats do not use their uropatagia to catch prey. At least one species, the greater horseshoe bat, has been documented catching prey in the tip of its wing by bending the phalanges around it, then transferring it to its mouth.[14][25] While a majority of horseshoe bats are nocturnal and hunt at night, Blyth's horseshoe bat (R. lepidus) is known to forage during the daytime on Tioman Island. This is hypothesized as a response to a lack of diurnal avian (day-active bird) predators on the island.[26]

They have especially small and rounded wingtips, low wing loading (meaning they lave large wings relative to body mass), and high camber. These factors give them increased agility, and they are capable of making quick, tight turns at slow speeds.[24] Relative to all bats, horseshoe bat wingspans are typical for their body sizes, and their aspect ratios, which relate wingspan to wing area, are average or lower than average. Some species, like Rüppell's horseshoe bat (R. fumigatus), Hildebrandt's horseshoe bat, Lander's horseshoe bat (R. landeri), and Swinny's horseshoe bat (R. swinnyi), have particularly large total wing area, though most horseshoe bat species have average wing area.[24]

Reproduction and life cycle

The mating systems of horseshoe bats are poorly understood. A review in 2000 noted that only about 4% of species had published information about their mating systems; along with the free-tailed bats (Molossidae), they had received the least attention of any bat family relative to their species diversity. At least one species, the greater horseshoe bat, appears to have a polygynous mating system where males attempt to establish and defend territories, attracting multiple females. Rhinolophus sedulus, however, is among the few species of bat that are believed to be monogamous (only 17 bat species are recognized as such as of 2000).[27] Some species, particularly temperate species, have an annual breeding season in the fall, while other species mate in the spring.[15] Many horseshoe bat species have the adaptation of delayed fertilization through female sperm storage. This is especially common in temperate species. In hibernating species, the sperm storage timing coincides with hibernation.[1] Other species like Lander's horseshoe bat have embryonic diapause, meaning that while fertilization occurs directly following copulation, the zygote does not implant into the uterine wall for an extended period of time.[14] The greater horseshoe bat has the adaptation of delayed embryonic development, meaning that growth of the embryo is conditionally delayed if the female enters torpor. This causes the interval between fertilization and birth to vary between two and three months.[28] Gestation takes approximately seven weeks before a single offspring is born, called a pup. Individuals reach sexual maturity by age two. While lifespans typically do not exceed six or seven years, some individuals may have extraordinarily long lives. A greater horseshoe bat individual was once banded and then rediscovered thirty years later.[15]

Behavior and social systems

Various levels of sociality are seen in horseshoe bats. Some species are solitary, with individuals roosting alone, while others are highly colonial, forming aggregations of thousands of individuals.[1] The majority of species are moderately social. In some species, the sexes segregate annually when females form maternity colonies, though the sexes remain together all year in others. Individuals hunt solitarily.[15] Because their hind limbs are poorly developed, they cannot scuttle on flat surfaces nor climb adeptly like other bats.[10][14]

Horseshoe bats enter torpor to conserve energy. During torpor, their body temperature drops to as low as 16 °C (61 °F) and their metabolic rates slow.[29] Torpor is employed by horseshoe bats in temperate, sub-tropical, and tropical regions.[30] Torpor has a short duration; when torpor is employed consistently for days, weeks, or months, it is known as hibernation.[31] Hibernation is used by horseshoe bats in temperate regions during the winter months.[30]

Predators and parasites

Overall, bats have few natural predators.[32] Horseshoe bat predators include birds in the order Accipitriformes (hawks, eagles, and kites), as well as falcons and owls.[33][34] Snakes may also prey on some species while they roost in caves,[35] and domestic cats may hunt them as well.[36] A 2019 study near a colony of bats in central Italy found that 30% of examined cat feces contained the remains of greater horseshoe bats.[37]

Horseshoe bats have a variety of internal and external parasites. External parasites (ectoparasites) include mites in the genus Eyndhovenia, "bat flies" of the families Streblidae and Nycteribiidae,[38] ticks of the genus Ixodes,[39] and fleas of the genus Rhinolophopsylla.[40] They are also affected by a variety of internal parasites (endoparasites), including trematodes of the genera Lecithodendrium, Plagiorchis, Prosthodendrium,[41] and cestodes of the genus Potorolepsis.[42]

الانتشار والموئل

تتميز خفافيش حدوة الحصان بالتوزيع الپاليوتاريومية، على الرغم من أن بعض الأنواع تقع في الجنوب المنطقة القطبية الشمالية القديمة.[8] تتواجد في العالم القديم، بما في ذلك أفريقيا، أستراليا، آسيا، أوروپا وأوقيانوسيا.[9] تتمتع خفافيش حدوة الحصان الكبرى بنطاق جغرافي كبير عن أي نوع آخر من خفافيش حدوة الحصان، حيث تنتشر عبر أوروپا، شمال أفريقيا، اليابان، الصين، وجنوب آسيا. انتشار الأنواع الأخرى أكثر تقييداً، مثل خفاش أندامان، والذي يتواجد فقط في جزر أندامان.[10] تجثم خفافيش حدوة الحصان في أماكن متنوعة، بما في ذلك المباني والكهوف والأشجار المجوفة وأوراق الشجر. تتواجد في كل من الموائل الحرجية وغير الحرجية،[15] حيث تنتشر معظم الأنواع في المناطق الإستوائية وشبه الإستوائية.[14] بالنسبة للأنواع التي تدخل في سبات، فإنها تختار الكهوف ذات درجة الحرارة المحيطية التي تبلغ حوالي 11°س .[43]

العلاقة بالبشر

كمستودع أمراض

ڤيروسات كورونا

| نوع الخفاش | عدد الڤيروسات |

|---|---|

| خفاش حدوة الحصان الصيني الأصهب | 30

|

| خفاش حدوة الحصان الكبرى | 9

|

| خفاش حدوة الحصان كبير الأذن | 2

|

| خفاش حدوة الحصان الصغرى | 2

|

| خفاش حدوة الحصان الوسطى | 1

|

| خفاش حدوة حصان بلاسيوس | 1

|

| خفاش ستوليشكا الثلاثي | 1

|

| الخفاش حر الذيل مجعد الشفاه | 1

|

تعتبر خفافيش حدوة الحصان ذات أهمية خاصة للصحة العامة والأمراض الحيوانية المنشأ كمصدر لڤيروسات كورونا.

في أعقاب تفشي سارس 2002-2004، أجريت اختبارات على الكثير من أنواع الحيوانات كمستودعات طبيعية محتملة لڤيروسات كورونا، سارس-كوڤ. من عام 2003 حتى 2018، أكتشف سبعة وأربعين ڤيروس كورونا ذات الصلة بسارس في خفافيش حدوة الحصان.[44] عام 2019، ارتبط سوق حيوانات حية في ووهان بالصين بتفشي سارس-كوڤ-2. أظهر التحليل الوراثي لسارس-كوڤ-2 أنه كان شبيهاً إلى حد كبير بالڤيروسات التي عثر عليها في خفافيش حدوة الحصان.[45]

بعد تفشي سارس، كانت خفافيش حدوة الحصان الصغرى إيجابية المصر، وكانت خفافيش حدوة الحصان الكبرى إيجابية للڤيروس فقط، وخفافيش حدوة الحصان كبيرة الأذن، خفافيش حدوة الحصان الصينية الصهباء، وخفافيش حدوة الحصان پيرسن إيجابية للمصل وللڤيروس.[44][46] كانت ڤيروسات الخفافيش شديدة الشبه بمرض سارس، بنسبة تشابه بلغت 88-92%.[47] يبدو أن التنوع النوعي لڤيروسات كورونها-الشبيهة بسارس قد نشأ في "خفاش حدوة الحصان الصيني الأصهب" بواسطة التأشيب المتماثل.[48] ومن المحتمل أن خفاش حدوة الحصان الصيني الأصهب كان يؤوي سلفاً مباشراً لسارس-كوڤ لدى البشر. على الرغم من أن خفافيش حدوة الحصان تبدو المستودع الطبيعي لڤيروسات كورونا المرتبطة بسارس، فمن المحتمل أن البشر أصيبوا بالمرض من خلال ملامسة حيوانات زباد النخيل المقنع المصابة، والتي تم تحديدها على أنها مضيف وسيط للڤيروس.[47]

خلال الفترة من 2003 حتى 2018، أكتشف في الخفافيش سبعة وأربعين ڤيروس كورونا ذات صلة بسارس، خمسة وأربعون في خفافيش حدوة الحصان. ثلاثون من الڤيروسات التاجية المرتبطة بسارس كانت من خفافيش حدوة الحصان الصينية، وتسعة من خفافيش حدوة الحصان الكبرى، واثنان من خفافيش حدوة الحصان كبيرة الأذن، واثنان خفافيش حدوة الحصان الصغرى، وواحد من خفافيش حدوة الحصان الوسطى، خفايش حدوة الحصان بلاسيوس.[44]

في سوق ووهان حيث تم الكشف عن سارس-كوڤ-2 ، كان 96% مشابهًا لڤيروس معزول من خفاش حدوة الحصان الوسطى. يشير بحث عن الأصول التطورية لسارس-كوڤ-2 [49] أن الخفافيش كانت المستودعات الطبيعية لسارس-كوڤ-2. لا يزال من غير الواضح كيفية انتقال الڤيروس إلى البشر، على الرغم من احتمال تورط عائل وسيط. كان يُعتقد أنه آكل النمل الحرشفي سوندا،[50] لكن منشورًا في يوليو 2020 لم يعثر على أي دليل على انتقال من آكل النمل الحرشفي إلى البشر.[49]

عثر فريق علمي من معهد ووهان للڤيروسات بالصين على آثار للڤيروس المسبب لمرض كوڤيد-19 في عينة براز للخفافيش كان قد تم رفعها من أحد الكهوف بالصين عام 2013، وفقاً لما جاء في مقال لمات ريدلي، العضو في مجلس اللوردات البريطاني والمؤلف للعديد من الكتب العلمية، نقلته صحيفة وول ستريت جورنال. وكان فريق العلماء فيما يبدو يجمع في الغالب عينات لبراز من نوع خفافيش مشابه جداً لخفاش حدوة الحصان لكن بأجنحة أقصر قليلاً، يسمى خفاش حدوة الحصان الصيني الأصهب، وذلك في إطار بحث علمي عن أصل الڤيروس المسؤول عن وباء سارس الذي انتشر بين عامي 2002 و2003. وعلى الرغم مما توصل له هذا البحث، إلا أنه تم تجاهله إلى حد كبير.[51]

ووجد الفريق العلمي في كهف شيتو، جنوب کونمینگ عاصمة مقاطعة يوننان الصينية، ڤيروسات في فضلات الخفافيش، تشبه ڤيروس سارس عند البشر بنسب كبيرة، خاصة عند المقارنة مع أي عينات تم جمعها من الثدييات الصغيرة، التي كان يُفترض حتى ذلك الحين أنها مصدر العدوى للبشر. وبالعودة إلى المختبر، وجد فريق العلماء أن أحد الڤيروسات من فضلات الخفافيش، ويسمى WIV1، يمكن أن ينمو ويتكاثر في خلايا القردة والخلايا البشرية الخاصة بتنشيط مُستقبل بروتين أو جين يسمى ACE2. ويوجد هذا الجين على سطح الخلايا البشرية، وهو يقلل من ضغط الدم والالتهاب، ولكنه يعمل أيضاً كبوابة للخلية تجعل الڤيروس يدخل إليها بسهولة، بما يعني أن البشر يمكن أن يصابوا بعدوى ڤيروس سارس مباشرة من فضلات الخفافيش.

وفي عام 2016، اكتشف العالم رالف باريك وزملاؤه في جامعة كارولينا الشمالية أن ڤيروس الخفافيش نفسه يمكن أن يصيب فئران التجارب الحية، والتي تم هندستها وراثياً بحيث تحاكي الجين البشري لمستقبلات ACE2.

وعند تفشي عدوى كوڤيد-19، تم تركيز الأبحاث على آكلات النمل الحرشفية. ويبدو أن التحليلات المبكرة لنسخة الڤيروس في عينات من آكلات النمل الحرشفية تشير إلى أنها كانت أكثر ارتباطاً بالنسخة البشرية من عينة خفاش حدوة الحصان.

يذكر أن الاتجار بشكل غير قانوني بحيوان آكل النمل الحرشفي لأغراض الطب الصيني التقليدي يجعل الكثيرين على اتصال بالحيوانات المريضة. وقبل أكثر من عام بقليل، صادر ضباط مكافحة التهريب في گوانگدونگ 21 آكل نمل حرشفي حياً واردة من مالي كانت بطريقها لأسواق الصين. وعلى الرغم من أفضل الجهود التي يبذلها مركز إنقاذ الحياة البرية المحلي، توفي 16 منها بسبب تورم وانتفاخ الرئتين نتيجة لڤيروس كورونا.

ولا يوجد ما يؤكد حتى الآن على وجود دور لثدييات آكل النمل في تفشي جائحة كورونا. ولكن بإلقاء نظرة فاحصة على المزيد من جينوم ڤيروس كورونا، والذي نشره أوائل يونيو 2020 باحثون من جامعة ولاية پنسلڤانيا وجامعة گلاسگو، بالتعاون مع زملائهم الصينيين والأوروپيين، تبيّن وجود ارتباط بين النسخة البشرية من الڤيروس بشكل وثيق مع عينة خفافيش حدوة الحصان، التي يرمز لها بـRaTG13. ومن غير الممكن حتى الآن معرفة ما إذا كان الڤيروس انتقل من الخفافيش إلى ثدييات آكل النمل الحرشفي ومنها إلى البشر، أو من الخفافيش إلى آكل النمل الحرشفي ومن الخفافيش إلى الإنسان بشكل متوازٍ.

ومن المثير للحيرة والدهشة أيضاً، أن نفس التحاليل المختبرية كشفت أن أحدث سلف شائع ڤفيروس كورونا البشري، في فضلات خفافيش حدوة الحصان، عاش منذ 40 عاماً على الأقل، مما يعني أن العدوى الأولى لم تكن في كهف يوننان الذي يبعد نحو 1000 ميل عن ووهان الذي بدأ تفشي الوباء منها. وتثير تلك النتائج شكوك وتخمينات بأنه ربما هناك مكان ما أقرب بكثير من ووهان هو الذي انتقلت منه العدوى أو أن هناك مستعمرة أخرى من الخفافيش تحمل نفس النوع من الڤيروسات.

يذكر أن الخفافيش تُباع في الأسواق وتزود بها المطاعم مباشرة في جميع أنحاء الصين وجنوب شرق آسيا، ولكن لم يظهر أي دليل مباشر على أنه يتم بيعها في سوق ووهان. ولا تعد خفافيش حدوة الحصان، التي هي أصغر بكثير من باقي أنواع الخفافيش، من بين الأنواع التي يتم تناولها. وتتمثل أهمية عينة كهف يوننان في أنها توضح أن ڤيروس الخفاش لم يكن بحاجة إلى إعادة التفاعل مع الڤيروسات في الأنواع الأخرى في السوق كي يصبح معدياً للبشر.

ويبدو أن معظم ڤيروسات كورونا تنشأ في الخفافيش، بما في ذلك مرض سارس ومتلازمة الشرق الأوسط التنفسية الذي التقطته الإبل من الخفافيش.

لكن لم يتضح بعد سبب إصابة خفافيش حدوة الحصان، على وجه التحديد، بڤيروس كورونا. إلا أنه سبق أن تلقت البشرية تحذيرات في السابق مع ظهور ڤيروسات إيبولا وهندرا ونيبا وميرس وسارس، لذا كان من المفترض أن يكون اكتشاف ڤيروس كورونا في فضلات خفاش حدوة الحصان، التي تم رفعها من كهف يوننان في عام 2013 بمثابة إنذار عالي النبرة.

ڤيروسات أخرى

ترتبط خفافيش حدوة الأحصان أيضاً بڤيروسات مثل الڤيروسات العظمية والڤيروسات المصفرة وڤيروسات هانتا. أثبتت الاختبارات أنها إيجابية "لڤيروسات العظام في الثدييات" (MRV)، بما في ذلك النمط 1 MRV المعزول من خفاش حدوة الحصان الصغرى والنمط 2 MRV المعزول من خفاش حدوة الحصان الصغير. نوع نمط 2 MRV الموجود في خفافيش حدوة الحصان لا ترتبط بعدوى البشر، على الرغم من أن البشر قد يمرضون بالتعرض لأنواع أخرى من النمط 2 MRV.[52] كان خفاش حدوة الحصان الأصهب إيجابي المصل لداء غابة كياسانور، وهي حمى نزفية ڤيروسية منقولة بالقراد عُرفت من جنوب الهند. ينتقل داء غابة كياسانور إلى البشر عن طريق الخفافيش التي انتقل لها المرض عن طريق القراد، ويبلغ معدل الوفاة 2-10%.[53] ڤيروس لونگتشوان، هو أحد أنواع ڤيروسات هانتا، والذي وُجد في خفاش حدوة الحصان الوطى، خفاش حدوة الحصان الصيني الأصهب، وخفاش حدوة الحصان الياباني الصغير.[54]

As food and medicine

Microbats are not hunted nearly as intensely as megabats: only 8% of insectivorous species are hunted for food, compared to half of all megabat species in the Old World tropics. Horseshoe bats are hunted for food, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa. Species hunted in Africa include the halcyon horseshoe bat (R. alcyone), Guinean horseshoe bat (R. guineensis), Hill's horseshoe bat (R. hilli), Hills' horseshoe bat (R. hillorum), Maclaud's horseshoe bat (R. maclaudi), the Ruwenzori horseshoe bat, the forest horseshoe bat (R. silvestris), and the Ziama horseshoe bat (R. ziama). In Southeast Asia, Marshall's horseshoe bat (R. marshalli) is consumed in Myanmar and the large rufous horseshoe bat (R. rufus) is consumed in the Philippines.[55]

The Ao Naga people of Northeast India are reported to use the flesh of horseshoe bats to treat asthma. Ecological anthropologist Will Tuladhar-Douglas stated that the Newar people of Nepal "almost certainly" use horseshoe bats, among other species, to prepare Cikā Lāpa Wasa ("bat oil"). Dead bats are rolled up and placed in tightly sealed jars of mustard oil; the oil is ready when it gives off a distinct and unpleasant smell. Traditional medicinal uses of the bat oil include removing "earbugs", reported to be millipedes that crawl into one's ears and gnaw at the brain, possibly a traditional explanation of migraines. It is also used as a purported treatment for baldness and partial paralysis.[56] In Senegal, there are anecdotal reports of horseshoe bats being used in potions to treat mental illness; in Vietnam, a pharmaceutical company reported using 50 t (50،000 kg) of horseshoe bat guano each year for medicinal uses.[57]

الحفاظ

اعتباراً من 2020، حسب تقييم الاتحاد الدولي لحفظ الطبيعة كان هناك 92 نوعاً من خفاش حدوة الحصان. وكان وضع الحفاظ الخاص بهم كالتالي:[58]

- في خطر انقراض ماحق: 1 نوع (خفاش حدوة الحصان الجبلي)

- نوع في خطر انقراض|في خطر انقراض: 13 نوع

- مهدد بخطر انقراض أدنى: 4 أنواع

- قريب من الخطر: 9 أنواع

- غير مهدد: 51 نوع

- ناقص البيانات: 14 نوع

مثل جميع الخفافيش التي تعيش في الكهوف، فإن خفافيش حدوة الحصان التي تعيش في الكهوف معرضة لاضطراب موائل الكهوف. يمكن أن يشمل الاضطراب تعدين ذرق الخفافيش واستغلال محاجر الحجر الجيري وسياحة الكهوف.[43]

المصادر

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د ذ Csorba, G.; Ujhelyi, P.; Thomas, P. (2003). Horseshoe Bats of the World: (Chiroptera: Rhinolophidae). Alana Books. ISBN 9780953604913.

- ^ Gray, J. E. (1825). "An attempt at a division of the family Vespertilionidae into groups". The Zoological Journal. 2: 242.

- ^ أ ب McKenna, M. C.; Bell, S. K. (1997). Classification of mammals: above the species level. Columbia University Press. p. 305. ISBN 9780231528535.

- ^ Taylor, Peter J.; Stoffberg, Samantha; Monadjem, Ara; Schoeman, Martinus Corrie; Bayliss, Julian; Cotterill, Fenton P. D. (2012). "Four New Bat Species (Rhinolophus hildebrandtii Complex) Reflect Plio-Pleistocene Divergence of Dwarfs and Giants across an Afromontane Archipelago". PLOS ONE. 7 (9): e41744. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...741744T. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0041744. PMC 3440430. PMID 22984399.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ "Family Rhinolophidae". Mammal Species of the World. Bucknell University. Retrieved 23 July 2020.

- ^ Springer, M. S.; Teeling, E. C.; Madsen, O.; Stanhope, M. J.; De Jong, W. W. (2001). "Integrated fossil and molecular data reconstruct bat echolocation". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 98 (11): 6241–6246. Bibcode:2001PNAS...98.6241S. doi:10.1073/pnas.111551998. PMC 33452. PMID 11353869.

- ^ أ ب Amador, L. I.; Arévalo, R. L. M.; Almeida, F. C.; Catalano, S. A.; Giannini, N. P. (2018). "Bat systematics in the light of unconstrained analyses of a comprehensive molecular supermatrix". Journal of Mammalian Evolution. 25: 37–70. doi:10.1007/s10914-016-9363-8. S2CID 3318167.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Demos, Terrence C.; Webala, Paul W.; Goodman, Steven M.; Kerbis Peterhans, Julian C.; Bartonjo, Michael; Patterson, Bruce D. (2019). "Molecular phylogenetics of the African horseshoe bats (Chiroptera: Rhinolophidae): Expanded geographic and taxonomic sampling of the Afrotropics". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 19 (1): 166. doi:10.1186/s12862-019-1485-1. PMC 6704657. PMID 31434566.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ أ ب ت Stoffberg, Samantha; Jacobs, David S.; MacKie, Iain J.; Matthee, Conrad A. (2010). "Molecular phylogenetics and historical biogeography of Rhinolophus bats". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 54 (1): 1–9. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2009.09.021. PMID 19766726.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ Geist, V.; Kleiman, D. G.; McDade, M. C. (2004). Grzimek's Animal Life Encyclopedia Mammals II. Vol. 13 (2nd ed.). Gale. pp. 387–393. ISBN 978-0787657895.

- ^ Palmer, T. S. (1904). "A List of the Genera and Families of Mammal". North American Fauna (23): 503.

- ^ Lydekker, Richard (1885). Catalogue of the Fossil Mammalia in the British Museum, (Natural History): The orders Primates, Chiroptera, Insectivora, Carnivora, and Rodentia. Order of the Trustees. p. 13.

- ^ Bogdanowicz, W.; Owen, R. D. (1992). "Phylogenetic analyses of the bat family Rhinolophidae" (PDF). Journal of Zoological Systematics and Evolutionary Research. 30 (2): 152. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0469.1992.tb00164.x.

The sole fossil genus, Palaeonycteris, is known from the Miocene of Europe (Heller 1936; Sigb and Legendre 1983; Hand 1984; cf. Simpson 1945 and Hall 1989)

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د ذ ر ز س ش ص Happold, M.; Cotterill, F. P. D. (2013). Kingdon, J.; Happold, D.; Butynski, T.; Hoffmann, M.; Happold, M.; Kalina, J. (eds.). Mammals of Africa. Vol. 4. A&C Black. pp. 300–303. ISBN 9781408189962.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د ذ Nowak, Ronald M. (1994). Walker's Bats of the World. JHU Press. pp. 108–110. ISBN 978-0-8018-4986-2.

- ^ Simmons, N. B. (1993). "Morphology, function, and phylogenetic significance of pubic nipples in bats (Mammalia, Chiroptera)" (PDF). American Museum Novitates (3077).

- ^ أ ب ت Hall, Leslie (1989). "Rhinolophidae". In Walton, D.W.; Richardson, B.J. (eds.). Fauna of Australia (PDF). AGPS Canberra.

- ^ أ ب Hermanson, J. W.; Woods, C. A.; Howell, K. M. (1982). "Dental ontogeny in the Old World leaf-nosed bats (Rhinolophidae, Hipposiderinae)". Journal of Mammalogy. 63 (3): 527–529. doi:10.2307/1380461. JSTOR 1380461.

- ^ Vaughan, T. (1970). "Chapter 3: The Skeletal System". In Wimsatt, W. (ed.). Biology of Bats. Academic Press. pp. 103–136. ISBN 9780323151191.

- ^ Stoffberg, Samantha; Jacobs, David S.; MacKie, Iain J.; Matthee, Conrad A. (2010). "Molecular phylogenetics and historical biogeography of Rhinolophus bats". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 54 (1): 1–9. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2009.09.021. PMID 19766726.

- ^ أ ب Jones, G.; Teeling, E. (2006). "The evolution of echolocation in bats". Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 21 (3): 149–156. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2006.01.001. PMID 16701491.

- ^ أ ب Vanderelst, Dieter; Jonas, Reijniers; Herbert, Peremans (2012). "The furrows of Rhinolophidae revisited". Journal of the Royal Society Interface. 9 (70): 1100–1103. doi:10.1098/rsif.2011.0812. PMC 3306658. PMID 22279156.

- ^ أ ب Huihua, Zhao; Shuyi, Zhang; Mingxue, Zuo; Jiang, Zhou (2003). "Correlations between call frequency and ear length in bats belonging to the families Rhinolophidae and Hipposideridae". Journal of Zoology. 259 (2): 189–195. doi:10.1017/S0952836902003199.

- ^ أ ب ت Norberg, U. M.; Rayner, J. M. V. (1987). "Ecological morphology and flight in bats (Mammalia; Chiroptera): Wing adaptations, flight performance, foraging strategy and echolocation". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences. 316 (1179): 335–427. Bibcode:1987RSPTB.316..335N. doi:10.1098/rstb.1987.0030.

- ^ Webster, Frederic A.; Griffin, Donald R. (1962). "The role of the flight membranes in insect capture by bats". Animal Behaviour. 10 (3–4): 332–340. doi:10.1016/0003-3472(62)90056-8.

- ^ Chua, Marcus A.H.; Aziz, Sheema Abdul (2018-12-19). "Into the light: atypical diurnal foraging activity of Blyth's horseshoe bat, Rhinolophus lepidus (Chiroptera: Rhinolophidae) on Tioman Island, Malaysia". Mammalia. 83 (1): 78–83. doi:10.1515/mammalia-2017-0128. ISSN 1864-1547. S2CID 90531252.

- ^ McCracken, Gary F.; Wilkinson, Gerald S. (2000). "Bat Mating Systems". Reproductive Biology of Bats. pp. 321–362. doi:10.1016/B978-012195670-7/50009-6. ISBN 9780121956707.

- ^ Gaisler, J. (2013). Kingdon, J.; Happold, D.; Butynski, T.; Hoffmann, M.; Happold, M.; Kalina, J. (eds.). Mammals of Africa. Vol. 4. A&C Black. pp. 327–328. ISBN 9781408189962.

- ^ Geiser, Fritz; Körtner, Gerhard (2010). "Hibernation and daily torpor in Australian mammals". Australian Zoologist. 35 (2): 204–215. doi:10.7882/AZ.2010.009.

- ^ أ ب Geiser, F.; Stawski, C. (2011). "Hibernation and Torpor in Tropical and Subtropical Bats in Relation to Energetics, Extinctions, and the Evolution of Endothermy". Integrative and Comparative Biology. 51 (3): 337–348. doi:10.1093/icb/icr042. PMID 21700575.

- ^ Altringham, John D. (2011). Bats: From Evolution to Conservation. Oxford University Press. p. 99. ISBN 9780191548727.

- ^ Nyffeler, Martin; Knörnschild, Mirjam (2013). "Bat Predation by Spiders". PLOS ONE. 8 (3): e58120. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...858120N. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0058120. PMC 3596325. PMID 23516436.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Mikula, Peter; Morelli, Federico; Lučan, Radek K.; Jones, Darryl N.; Tryjanowski, Piotr (2016). "Bats as prey of diurnal birds: a global perspective: Predation of bats by diurnal birds". Mammal Review (in الإنجليزية). 46 (3): 160–174. doi:10.1111/mam.12060.

- ^ García, A. M.; Cervera, F.; Rodríguez, A. (2005). "Bat predation by long-eared Owls in mediterranean and temperate regions of southern Europe" (PDF). Journal of Raptor Research. 39 (4): 445–453.

- ^ Barti, Levente; Péter, Áron; Csősz, István; Sándor, Attila D. (2019). "Snake predation on bats in Europe: New cases and a regional assessment" (PDF). Mammalia. 83 (6): 581–585. doi:10.1515/mammalia-2018-0079. S2CID 92282216.

- ^ Ancillotto, Leonardo; Serangeli, Maria Tiziana; Russo, Danilo (2013). "Curiosity killed the bat: Domestic cats as bat predators". Mammalian Biology. 78 (5): 369–373. doi:10.1016/j.mambio.2013.01.003.

- ^ Ancillotto, L.; Venturi, G.; Russo, D. (2019). "Presence of humans and domestic cats affects bat behaviour in an urban nursery of greater horseshoe bats (Rhinolophus ferrumequinum)". Behavioural Processes. 164: 4–9. doi:10.1016/j.beproc.2019.04.003. PMID 30951813. S2CID 92844287.

- ^ Sharifi, Mozafar; Taghinezhad, Najmeh; Mozafari, Fatema; Vaissi, Somaye (2013). "Variation in ectoparasite load in the Mehely's horseshoe bat, Rhinolophus mehelyi (Chiroptera: Rhinolophidae) in a nursery colony in western Iran". Acta Parasitologica. 58 (2): 180–184. doi:10.2478/s11686-013-0122-1. PMID 23666653. S2CID 7173658.

- ^ Hornok, Sándor; Görföl, Tamás; Estók, Péter; Tu, Vuong Tan; Kontschán, Jenő (2016). "Description of a new tick species, Ixodes collaris n. sp. (Acari: Ixodidae), from bats (Chiroptera: Hipposideridae, Rhinolophidae) in Vietnam". Parasites & Vectors. 9 (1): 332. doi:10.1186/s13071-016-1608-0. PMC 4902904. PMID 27286701.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Kotti, B. K. (2018). "Distribution and Specificity of Host-Parasite Associations of Fleas (Siphonaptera) in the Central Caucasus". Entomological Review. 98 (9): 1342–1350. doi:10.1134/S0013873818090129. S2CID 85527706.

- ^ Horvat, Ž.; Čabrilo, B.; Paunović, M.; Karapandža, B.; Jovanović, J.; Budinski, I.; Bjelić Čabrilo, O. (2017). "Gastrointestinal digeneans (Platyhelminthes: Trematoda) of horseshoe and vesper bats (Chiroptera: Rhinolophidae and Vespertilionidae) in Serbia". Helminthologia. 54: 17–25. doi:10.1515/helm-2017-0009. S2CID 90530235.

- ^ Makarikova, Ò. À.; Makarikov, A. A. (2012). "First report of Potorolepis Spassky, 1994 (Eucestoda: Hymenolepididae) from China, with description of a new species in bats (Chiroptera:: Rhinolophidae)". Folia Parasitologica. 59 (4): 272–278. doi:10.14411/fp.2012.038. PMID 23327008.

- ^ أ ب Furey, Neil M.; Racey, Paul A. (2016). "Conservation Ecology of Cave Bats". Bats in the Anthropocene: Conservation of bats in a changing world. Springer, Cham. pp. 463–500. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-25220-9_15. ISBN 978-3-319-25218-6.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Luk, Hayes K.H.; Li, Xin; Fung, Joshua; Lau, Susanna K.P.; Woo, Patrick C.Y. (2019). "Molecular epidemiology, evolution and phylogeny of SARS coronavirus". Infection, Genetics and Evolution. 71: 21–30. doi:10.1016/j.meegid.2019.03.001. PMC 7106202. PMID 30844511.

- ^ "Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) Situation Report" (PDF). World Health Organization. 11 February 2020. Retrieved 15 February 2020.

- ^ Shi, Zhengli; Hu, Zhihong (2008). "A review of studies on animal reservoirs of the SARS coronavirus". Virus Research. 133 (1): 74–87. doi:10.1016/j.virusres.2007.03.012. PMC 7114516. PMID 17451830.

- ^ أ ب Wang, Lin-Fa; Shi, Zhengli; Zhang, Shuyi; Field, Hume; Daszak, Peter; Eaton, Bryan (2006). "Review of Bats and SARS". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 12 (12): 1834–1840. doi:10.3201/eid1212.060401. PMC 3291347. PMID 17326933.

- ^ Yuan J, Hon CC, Li Y, Wang D, Xu G, Zhang H, Zhou P, Poon LL, Lam TT, Leung FC, Shi Z. Intraspecies diversity of SARS-like coronaviruses in Rhinolophus sinicus and its implications for the origin of SARS coronaviruses in humans. J Gen Virol. 2010 Apr;91(Pt 4):1058–62. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.016378-0. Epub 2009 Dec 16. PubMed

- ^ أ ب Boni, Maciej F.; Lemey, Philippe; Jiang, Xiaowei; Lam, Tommy Tsan-Yuk; Perry, Blair W.; Castoe, Todd A.; Rambaut, Andrew; Robertson, David L. (2020). "Evolutionary origins of the SARS-CoV-2 sarbecovirus lineage responsible for the COVID-19 pandemic". Nature Microbiology. 5 (11): 1408–1417. doi:10.1038/s41564-020-0771-4. PMID 32724171. S2CID 220809302.

- ^ MacKenzie, John S.; Smith, David W. (2020). "COVID-19: A novel zoonotic disease caused by a coronavirus from China: What we know and what we don't". Microbiology Australia. 41: 45. doi:10.1071/MA20013. PMC 7086482. PMID 32226946.

Evidence from the sequence analyses clearly indicates that the reservoir host of the virus was a bat, probably a Chinese or Intermediate horseshoe bat, and it is probable that, like SARS-CoV, an intermediate host was the source of the outbreak.

- ^ "هكذا تسببت خفافيش حدوة الحصان في تفشي فيروس كورونا". العربية نت. 2021-06-05. Retrieved 2021-06-05.

- ^ Beltz, Lisa A. (2017). Bats and Human Health: Ebola, SARS, Rabies and Beyond. John Wiley & Sons. p. 155. ISBN 9781119150046.

- ^ Pattnaik, Priyabrata (2006). "Kyasanur forest disease: An epidemiological view in India". Reviews in Medical Virology. 16 (3): 151–165. doi:10.1002/rmv.495. PMID 16710839. S2CID 32814428.

- ^ Guo, Wen-Ping; Lin, Xian-Dan; Wang, Wen; Tian, Jun-Hua; Cong, Mei-Li; Zhang, Hai-Lin; Wang, Miao-Ruo; Zhou, Run-Hong; Wang, Jian-Bo; Li, Ming-Hui; Xu, Jianguo; Holmes, Edward C.; Zhang, Yong-Zhen (2013). "Phylogeny and Origins of Hantaviruses Harbored by Bats, Insectivores, and Rodents". PLOS Pathogens. 9 (2): e1003159. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1003159. PMC 3567184. PMID 23408889.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Mildenstein, T.; Tanshi, I.; Racey, P. A. (2016). "Exploitation of bats for bushmeat and medicine". Bats in the Anthropocene: Conservation of Bats in a Changing World. Springer. p. 327. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-25220-9_12. ISBN 978-3-319-25218-6. S2CID 130038936.

- ^ Tuladhar-Douglas, Will (2008). "The Use of Bats as Medicine Among the Newars". Journal of Ethnobiology. 28: 69–91. doi:10.2993/0278-0771(2008)28[69:TUOBAM]2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0278-0771.

- ^ Riccucci, M. (2012). "Bats as materia medica: An ethnomedical review and implications for conservation". Vespertillio. 16 (16): 249–270.

- ^ "Taxonomy=Rhinolophidae". IUCN. Retrieved 14 December 2020.