معاهدة پاريس (1856)

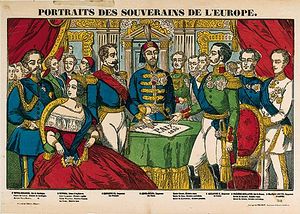

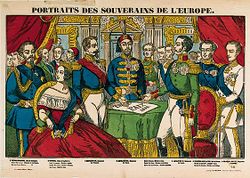

إدوار لوي دوبوف, مؤتمر پاريس، 1856، قصر ڤرساي. | |

| النوع | Multilateral Treaty |

|---|---|

| وُقـِّعت | 30 مارس 1856 |

| المكان | Paris, France |

| الموقعون الأصليون | |

| المصدقون | France, United Kingdom, Ottoman Empire, Sardinia, Prussia, Austria, Russian Empire |

| اللغة | French |

معاهدة پاريس 1856 كانت تسوية لحرب القرم بين روسيا وحليف الدولة العثمانية، الامبراطورية البريطانية، الامبراطورية الفرنسية الثانية، ومملكة سردينيا. المعاهدة، وقعت في 30 مارس 1856 في مؤتمر پاريس ، والتي بموجبها أصبح البحر الأسود أرض حيادية، أغلق أمام مرور جميع السفن، ومنعت التحصينات ووجود الأسلحة على شواطئه. تمثل هذه المعاهدة انتكاسة قوية للنفوذ الروسي بالمنطقة.

السياق التاريخي

في 30 مارس 1856 خلال مؤتمر باريس الذي جمع ممثلين لكل من فرنسا، روسيا، الدولة العثمانية، المملكة المتحدة وسردينيا.[1][2]

المعاهدة كانت للإقرار بهزيمة روسيا في حرب القرم، ومن بين ما اتفق عليه تنازل روسيا على جزء من أراضيها لدولة مولداڤيا، فرض حياد البحر الأسود وحرية الملاحة في نهر الدانوب.

The treaty diminished Russian influence in the region. Conditions for the return of Sevastopol and other towns and cities in the south of Crimea to Russia were severe since no naval or military arsenal could be established by Russia on the coast of the Black Sea.

الملخص

The Treaty of Paris was signed on 30 March 1856 at the Congress of Paris with Russia on one side of the negotiating table and France, Britain, the Ottoman Empire and the Kingdom of Sardinia on the other side. The treaty came about to resolve the Crimean War, which had begun on 23 October 1853, when the Ottoman Empire formally declared war on Russia after Russian troops occupied the Danubian Principalities.[3]

The Treaty of Paris was seen as an achievement of the Tanzimat policy of reform. The Western European alliance powers pledged to maintain the integrity of the Ottoman Empire and restored the respective territories of the Russian and the Ottoman Empires to their pre-war boundaries. They also demilitarised the Black Sea to improve trade, which greatly weakened Russia's influence in the region. Moldavia and Wallachia were recognized as quasi-independent states under Ottoman suzerainty. They gained the left bank of the mouth of the Danube and part of Bessarabia from Russia as a result of the treaty.[4]

المفاوضات

As the Crimean War ended, all sides of the war wanted to come to a lasting resolution due to the casualties and attrition suffered. However, competing ideas of war resolution inhibited the drafting of lasting and definitive peace treaty. Even amongst the allies, disagreements between nations concerning the nature of the treaty created an uncertain peace, resulting in further diplomatic issues involving the Ottoman Empire, especially in terms of its relations with the Russian Empire and the Concert of Europe. Also, mistrust between the French and British allies during the war effort compounded problems in formulating a comprehensive peace.[5] Thus, the terms of the treaty made future relations between the major powers uncertain.[6][7]

أهداف السلام

الأهداف الروسية

Despite losing the war, the Russians wanted to ensure attain the best possible outcome for the empire at the Congress of Paris. When Alexander II took the crown of Russia in 1855, he inherited a potential crisis that threatened the collapse of the empire.[citation needed] There were problems throughout the empire, stretching from parts of Finland to Poland and Crimea and many tribal conflicts, and the Russian economy was on the brink of collapse.[citation needed] Russia knew that within a few months, a total defeat in the war was imminent, which would mean the complete humiliation of Russia on an international scale, and further loss of territory.

Alexander II pursued peace talks with Britain and France in Paris in 1856, seeking to keep some imperial possessions, to stop the deaths of thousands of its army reserves, and to prevent an economic crisis.[5] Similarly, Russia wanted to maintain at least a pretence of military power, which had posed a formidable threat to the west European allies. It attempted "to turn defeat into victory ... through ... peacetime [internal] reforms and diplomatic initiatives."[8]

أهداف بريطانيا وفرنسا

During the war Britain and France resumed their latent rivalry, largely derived from the Napoleonic Wars. The French blamed many of the defeats of the alliance on the fact that Britain had marched into war without a clear plan. Defeats including the Charge of the Light Brigade during the Battle of Balaclava highlighted the logistical and tactical failures of Britain, and spurred calls for increased army professionalism.[9] The British were increasingly wary throughout the war that the French might capitalise on a weakened Russia and focus their attention on seeking revenge on the British for French military defeats at Trafalgar and Waterloo.[10]

Although there was a call for the end of the war in Britain, including riots in London, there was support for its continuation, and expansion to punish Russia's imperial ambition, particularly from the incumbent prime minister Lord Palmerston.[9][11]

Britain and France desired to ensure that the Ottoman Empire were made stronger by the Treaty of Paris, ensuring a stable balance of power in Europe. They hoped that peace and restricting Russian access to key areas, such as the Black Sea, would allow the Ottoman Empire to focus on internal issues including rising nationalism in many nations under the empire's authority. Without the Ottomans being in full control of their empire, the great powers feared that it could lose much of its territory in future wars with the Russian Empire and the Austrian Empire, eventually strengthening these nations and posing a significant threat to the French and British.[12] Thus, the full removal of Russian presence in the Danubian principalities and the Black Sea served both to protect British dominance and to inhibit the Russian Empire from expanding its influence readily.

الخسائر الروسية

The Ottoman, British and French governments desired a more crushing defeat for Russia, which was still crippled in many key areas. The Russian Empire had lost over 500,000 troops[13] and knew that pressing further militarily with their largely unprofessional army would have resulted in higher casualties and attrition.[citation needed]

Russia was forced to withdraw from the Danubian Principalities, where it had started a period of common tutelage for the Ottomans and the Congress of Great Powers.[14]

Russia had to return to Moldavia part of its territory it had annexed in 1812 (to the mouth of the Danube, in southern Bessarabia). The Danubian principalities and the Principality of Serbia, were given greater self-government, resulting in the Russian Empire having a diminished influence over them.

Russia was forced to abandon its claim to protect Christians in the Ottoman Empire, which initially served as part of the pretext for the Crimean War.[citation needed]

Russian warships were banned from sailing the Black Sea, which greatly decreased Russian influence over the Black Sea trade.

The defeat accentuated the impediments of the Russian Empire, contributing to future reform including the emancipation of the serfs and the spread of revolutionary ideas.[citation needed]

الآثار على المدى القصير

كانت إحدى النتائج المباشرة للمعاهدة هي إعادة فتح البحر الأسود للتجارة الدولية الآمنة والمفتوحة بعد الحرب البحرية ووجود السفن الحربية الروسية جعل التجارة صعبة. كان الأسطول الروسي في البحر الأسود هائلاً وأغرق الأسطول التركي.[14]

The Treaty of Paris was influenced by the general public in France and Britain because the Crimean War, was one of the first wars in which the general public received relatively prompt media coverage of the events. The British prime minister, Lord Aberdeen, who was viewed as being incompetent to lead the war effort, lost a vote in parliament and resigned in favour of Lord Palmerston, who was seen as having a clearer plan for victory.[5] Peace was accelerated in part because the general population of the western allies had greater access to and understanding of political intrigue and foreign policy, and therefore demanded an end to the war.

الآثار على المدى الطويل

Nationalism was bolstered in many ways by the Crimean War, and very little could be done at a systemic level to stem the tides of growing nationalist sentiment in many nations. The Ottoman Empire, for the next few decades until World War I, had to face a number of patriotic uprisings in many of its provinces. No longer capable of withstanding the internal forces tearing it apart, the empire was splintering, as many ethnic groups cried out for more rights, most notably self-rule. Britain and France may have allowed the situation in Europe to stabilise briefly, but the Peace of Paris did little to create lasting stability in the Concert of Europe. The Ottomans joined the Concert of Europe after the Peace was signed, but most European nations looked to the crumbling empire with either hungry or worried eyes.

The war revealed to the world just how important solving the "Eastern Question" was to the stability of Europe; however, the Peace of Paris provided no clear answer or guidance.[7]

The importance of the Ottoman Empire to Britain and France in maintaining the balance of power in the Black and the Mediterranean Seas made many view the signing of the Treaty of Paris to be the entrance of the Ottoman Empire to the European international theatre. Greater penetration of European influence into Ottoman international law and a decline in emphasis of Islamic practices in their legal system illustrate more of an inclusion of the Ottoman Empire into European politics and disputes, leading to its major role in the First World War.[15]

Austria and Germany were affected by nationalism as a result of the signing of the Peace of Paris. Austria was normally an ally of Russia but was neutral during the war, mobilized troops against Russia and sent at least an ultimatum asking the withdrawal of Russian armies from the Balkans.

After the Russian defeat, relations between the two nations, the most conservative in Europe, remained very strained. Russia, the gendarme of conservatism and the saviour of Austria during the Hungarian Revolution of 1848, angrily resented the failure of Austria to help or assist its former ally, which contributed to Russia's non-intervention in the 1859 Franco-Austrian War, ending Austrian influence in Italy; in the 1866 Austro-Prussian War, with the loss of its influence over the German Confederation; and in the Ausgleich (compromise) with Hungary of 1867, which meant the sharing of the power in the empire with the Magyars. The status of Austria as a great power, after the unifications of Germany, Italy was now severely diminished. Austria slowly became little more than a German satellite state.

A unified and strengthened Germany was not a pleasant thought for many in Britain and France[16] since it would pose a threat to both French borders and British political and economic interest in the East.

Essentially, the war that sought to stabilise power relations in Europe brought about by a temporary peace. The great powers only strengthened nationalist aspirations of ethnic groups, under the control of the victorious Ottomans and of the German states. By 1877, the Russians and the Ottomans would once again be at war.[7]

البنود

اعترفت المعاهدة بالدولة العثمانية في الاتفاق الأوروبي، ووعدت القوى باحترام استقلالها ووحدة أراضيها. تخلت روسيا عن القليل من الأرض وتخلت عن مطالبتها بحماية المسيحيين في المناطق العثمانية. تم تجريد البحر الأسود من السلاح، وتم إنشاء لجنة دولية لضمان حرية التجارة والملاحة على نهر الدانوب.

ستبقى مولداڤيا وولاخيا تحت الحكم العثماني الاسمي ولكن سيتم منحهما دساتير مستقلة ومجالس وطنية، والتي كانت ستراقب من قبل القوى المنتصرة. كان من المقرر إقامة مشروع استفتاء لرصد إرادة الشعوب على التوحيد. استعادت مولدافيا جزءاً من بسارابيا ((بما في ذلك جزء من بودجاك)، والتي كانت قد احتفظت بها قبل عام 1812، مما أدى إلى إنشاء منطقة عازلة بين الإمبراطورية العثمانية وروسيا في الغرب. ظلت الإمارتان المتحدتان ولاخيا ومولداڤيا لرومانيا، والتي سيتم تشكيلها لاحقاً من المنطقتين، دولة عميلة عثمانية حتى عام 1877.

تم وضع قواعد جديدة للتجارة في زمن الحرب في إعلان باريس: (1) القرصنة كانت غير قانونية؛ (2) يغطي العلم المحايد البضائع المعادية باستثناء البضائع المهربة؛ (3) البضائع المحايدة ، باستثناء البضائع المهربة، لم تكن عرضة للاستيلاء عليها تحت علم العدو؛ (4) يجب أن يكون الحصار فعالاً لكي يكون قانونياً. [17]

كما نزعت المعاهدة السلاح عن جزر أولاند الواقعة في بحر البلطيق، والتي كانت تابعة إلى دوقية فنلندا الكبرى الروسية المتمتعة بالحكم الذاتي. دمرت القوات البريطانية والفرنسية قلعة بومارسوند في عام 1854، وأراد التحالف منع استخدامها في المستقبل كقاعدة عسكرية روسية.

الخسائر الروسية

الأطراف الموقعة

ألكسندر ڤاليڤسكي

ألكسندر ڤاليڤسكي Bourqueney

Bourqueney Buol-Schauenstein

Buol-Schauenstein هوبنر

هوبنر كلارندون

كلارندون كاولي

كاولي مانتويفل

مانتويفل هاتسفلت

هاتسفلت أورلوف

أورلوف Brunnow

Brunnow كاڤور

كاڤور di Villamarina

di Villamarina محمد أمين علي پاشا

محمد أمين علي پاشا محمد جميل بك

محمد جميل بك

الذكرى

- In 2006, Finland celebrated the 150th anniversary of the demilitarisation of the Åland Islands by issuing a commemorative coin. Its obverse depicts a pine tree, very typical in the Åland Islands, and the reverse features a boat's stern and rudder, with a dove perched on the tiller, a symbol of 150 years of peace.

- Berwick-upon-Tweed – an apocryphal story concerns Berwick's status with Russia

انظر أيضاً

المصادر

- ^ أ ب Hertslet, Edward (1875). "General treaty between Great Britain, Austria, France, Prussia, Russia, Sardinia and Turkey, signed at Paris on 30th March 1856". The Map of Europe by Treaty showing the various political and territorial changes which have taken place since the general peace of 1814, with numerous maps and notes. Vol. 2. London: Butterworth. pp. 1250–1265.

- ^ أ ب Albin, Pierre (1912). "Acte General Du Congres de Paris, 30 Mars 1856". Les Grands Traités Politiques: Recueil des Principaux Textes Diplomatiques Depuis 1815 Jusqu'à nos Jours avec des Notices Historiques et des Notes. Paris: Librairie Félix Alcan. pp. 170–180.

- ^ C. D. Hazen et al., Three Peace Congresses of the Nineteenth Century (1917).

- ^ Winfried Baumgart, and Ann Pottinger Saab, Peace of Paris, 1856: Studies in War, Diplomacy & Peacemaking (1981).

- ^ أ ب ت James, Brian. ALLIES IN DISARRAY: The Messy End of the Crimean War. History Today, 58, no. 3, 2008, pp. 24–31.

- ^ Temperley, Harold. The Treaty of Paris of 1856 and Its Execution. The Journal of Modern History, 4, no. 3, 1932, pp. 387–414.

- ^ أ ب ت Pearce, Robert. The Results of the Crimean War. History Review, 70, 2011, pp. 27–33

- ^ Gorizontoy, Leonid. The Crimean War as a Test of Russia's Imperial Durability.Russian Studies in History, 51, no.1, 2012, pp. 65–94

- ^ أ ب Figes, Orlando (2010). Crimea: The Last Crusade. London: Allen Lane. pp. 400–02, 406–08, 469–471. ISBN 978-0-7139-9704-0. OCLC 640080436.

- ^ James, Brian. "Allies in Disarray: The Messy End of the Crimean War", History Today, 58, no. 3, 2008, pp. 24–31.

- ^ Karl Marx, "The Aims of the Negotiations – Polemic Against Prussia – A Snowball Riot" contained in the Collected Works of Karl Marx and Frederick Engels: Volume 13, p. 599.

- ^ Pearce, Robert. "The Results of the Crimean War". History Review 70, 2011, pp. 27–33

- ^ Clodfelter, Micheal (2017). Warfare and Armed Conflicts: A Statistical Encyclopedia of Casualty and Other Figures, 1492-2015 (4th ed.). Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company. p. 180. ISBN 978-1-4766-2585-0. OCLC 984342511.

- ^ أ ب Benn, David Wedgwood (2012). "The Crimean War and its lessons for today". International Affairs. 88 (2): 387–391. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2346.2012.01078.x. ISSN 0020-5850 – via Oxford Academic.

- ^ Palabiyik, Mustafa Serdar, The Emergence of the Idea of ‘International Law’ in the Ottoman Empire before the Treaty of Paris (1856), Middle Eastern Studies, 50:2, 2014, 233-251.

- ^ Trager, Robert. Long-Term Consequences of Aggressive Diplomacy: European Relations after Austrian Crimean War Threats. Security Studies, 21, no. 2, 2012, pp. 232–265.

- ^ A.W. Ward; G. P. Gooch (1970). The Cambridge History of British Foreign Policy 1783–1919. Cambridge U.P,. pp. 390–91.

قراءات إضافية

- Baumgart, Winfried, and Ann Pottinger Saab. Peace of Paris, 1856: Studies in War, Diplomacy & Peacemaking (1981) 230pp

- Edouard Gourdon, Histoire du Congrès de Paris, Paris, 1857, full text at google Print

- Taylor, A.J.P. The Struggle for Mastery in Europe: 1848–1918 (1954) pp 83–97

- Temperley, Harold. "The Treaty of Paris of 1856 and Its Execution," Journal of Modern History (1932) 4#3 pp. 387–414 in JSTOR

وصلات خارجية

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Articles with unsourced statements from February 2023

- Articles with unsourced statements from October 2020

- حرب القرم

- معاهدات سلام فرنسا

- معاهدات سلام روسيا

- معاهدات الدولة العثمانية

- الحروب الروسية التركية

- 1856 في فرنسا

- معاهدات سلام المملكة المتحدة

- معاهدات 1856

- معاهدات الامبراطورية الروسية

- معاهدات الامبراطورية الفرنسية الثانية

- القرن 19 في پاريس

- معاهدات الامبراطورية النمساوية

- معاهدات مملكة پروسيا

- معاهدات مملكة سردينيا

- معاهدات المملكة المتحدة (1801–1922)