جرم بعد نپتون

|

|

‡ الكواكب القزمة بعد نپتون تسمى "پلوتوية" |

جرم بعد نپتون trans-Neptunian object (اختصاراً TNO، تُكتب أيضاً transneptunian object)، هي أي كوكب صغير في المجموعة الشمسية تقع مداراته حول الشمس على مسافة متوسطة أأكبر من [[نپتوني]، والذي يبلغ محوره الشبه رئيسي 30.1 وحدة فلكية.

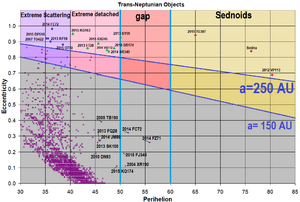

عادة ما تٌقسم الأجرام بعد بعد نپتون إلى أجرام حزام كايپر كلاسيكية ورنانة، القرص المتفرق والأجرام المنفصلة مع سيدنويدات هي الأكثر بعداً..[nb 1] في أكتوبر 2018، كان كتالوج الكواكب الصغرى يحوي على 825 جرم بعد نپتون مرقم وأكثر من 2.000 جرم غير مرقم.[2][3][4][5][6]

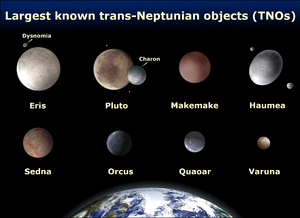

كان پلوتو هو أول جرم بعد نپتون تم اكتشافه عام 1930. وفي عام 1992 اكتف ثاني الأجرام بعد نپتون والذي يدور حول الشمس مباشرة 15760 ألبيون. ومن أكبر الأجرام بعد نپتون ،إريس، يليه پلوتو، 2007 OR10، مكماك وهاوما. اكتشف أكثر من 80 ساتل في مدار الأجرام بعد نپتون. تختلف الأجرام بعد نپتون من حيث اللون وتكون إمام خضراء-زرقا أو حمراء. ويعتقد أنها تحتوي على تركيبات صخرية، كربون جوي وتكوينات جليدية متطايرة مثل الماء والميثان، مغطاة بالثولين والمركبات العضوية الأخرى.

الكواكب الصغرى الإثنى عشر بمحور شبه رئيسي أكبر من 150 وحدة فلكية وحضيض شمسي أكثر من 30 وحدة فلكية، يُطلق عليها الأجرام القصوى بعد نپتون.[7]

التاريخ

اكتشاف پلوتو

The orbit of each of the planets is slightly affected by the gravitational influences of the other planets. Discrepancies in the early 1900s between the observed and expected orbits of Uranus and Neptune suggested that there were one or more additional planets beyond Neptune. The search for these led to the discovery of Pluto in February 1930, which was progressively determined to be too small to explain the discrepancies. Revised estimates of Neptune's mass from the Voyager 2 flyby in 1989 showed that there is no real discrepancy: The problem was an error in the expectations for the orbits.[8] Pluto was easiest to find because it is the brightest of all known trans-Neptunian objects. It also has a lower inclination to the ecliptic than most other large TNOs, so its position in the sky is typically closer to the search zone in the disc of the Solar System.

الاكتشافات اللاحقة

After Pluto's discovery, American astronomer Clyde Tombaugh continued searching for some years for similar objects but found none. For a long time, no one searched for other TNOs as it was generally believed that Pluto, which up to August 2006 was classified as a planet, was the only major object beyond Neptune. Only after the 1992 discovery of a second TNO, 15760 Albion, did systematic searches for further such objects begin. A broad strip of the sky around the ecliptic was photographed and digitally evaluated for slowly moving objects. Hundreds of TNOs were found, with diameters in the range of 50 to 2,500 kilometers. Eris, the most massive known TNO, was discovered in 2005, revisiting a long-running dispute within the scientific community over the classification of large TNOs, and whether objects like Pluto can be considered planets. In 2006, Pluto and Eris were classified as dwarf planets by the International Astronomical Union.

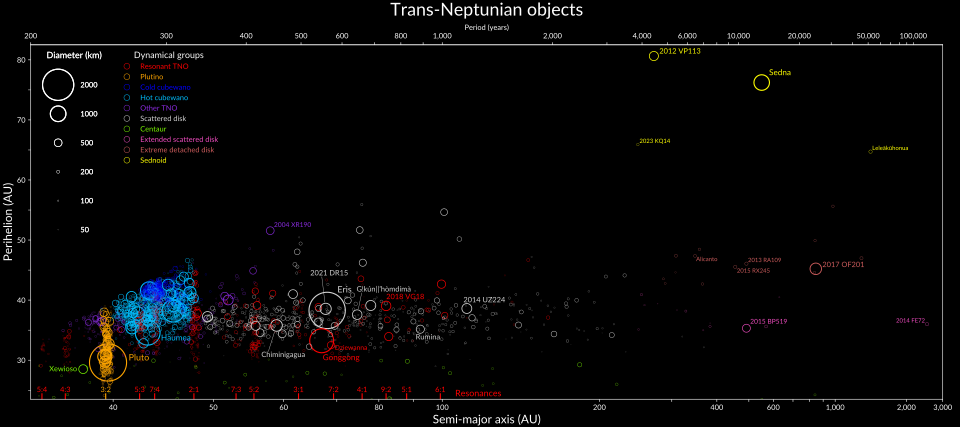

التصنيف

According to their distance from the Sun and their orbital parameters, TNOs are classified in two large groups: the Kuiper belt objects (KBOs) and the scattered disc objects (SDOs).[nb 1] The diagram below illustrates the distribution of known trans-Neptunian objects beyond the orbit of Neptune at 30.07 AU. Different classes of TNOs are represented in different colours. The main part of the Kuiper belt is shown in orange and blue between the 2:3 and 1:2 orbital resonances with Neptune. Plutinos (orange) are the objects in the 2:3 resonance, including the dwarf planets Pluto and Orcus. Classical Kuiper belt objects are shown in blue, with the largest of these, including Haumea, Makemake, and Quaoar in the dynamically 'hot' population in light blue, and the dynamically 'cold' population, including 486958 Arrokoth, in low-eccentricity orbits clustered near 44 AU in dark blue.

The scattered disc can be found beyond the Kuiper belt, shown in grey and purple. These objects, including dwarf planets Eris and Gonggong have been excited into eccentric orbits due to gravitational perturbations by Neptune, resulting in a concentration of their perihelia in the horizontal band between 30 and 40 AU. Some detached objects, such as 6129112004 XR however have higher perihelia. Centaurs, shown in green, have been perturbed from the scattered disc onto orbits crossing the outer planets. Bodies in both of these groups may be found in mean-motion resonances with Neptune; these are plotted in red.

Finally, extreme trans-Neptunian objects are shown at the right of the diagram, with many having orbits that extend over 1000 AU from the sun. These can be divided into the extended scattered disc (pink), including 7683252015 BP, the distant detached objects (brown), including 2017 OF201, and the four known sednoids, including Sedna and 541132 Leleākūhonua.

KBOs

The Edgeworth – Kuiper belt contains objects with an average distance to the Sun of 30 to about 55 AU, usually having close-to-circular orbits with a small inclination from the ecliptic. Edgeworth – Kuiper belt objects are further classified into the resonant trans-Neptunian object that are locked in an orbital resonance with Neptune, and the classical Kuiper belt objects, also called "cubewanos", that have no such resonance, moving on almost circular orbits, unperturbed by Neptune. There are a large number of resonant subgroups, the largest being the twotinos (1:2 resonance) and the plutinos (2:3 resonance), named after their most prominent member, Pluto. Members of the classical Edgeworth – Kuiper belt include 15760 Albion, Quaoar and Makemake.

Another subclass of Kuiper belt objects is the so-called scattering objects (SO). These are non-resonant objects that come near enough to Neptune to have their orbits changed from time to time (such as causing changes in semi-major axis of at least 1.5 AU in 10 million years) and are thus undergoing gravitational scattering. Scattering objects are easier to detect than other trans-Neptunian objects of the same size because they come nearer to Earth, some having perihelia around 20 AU. Several are known with g-band absolute magnitude below 9, meaning that the estimated diameter is more than 100 km. It is estimated that there are between 240,000 and 830,000 scattering objects bigger than r-band absolute magnitude 12, corresponding to diameters greater than about 18 km. Scattering objects are hypothesized to be the source of the so-called Jupiter-family comets (JFCs), which have periods of less than 20 years.[9][10][11]

SDOs

The scattered disc contains objects farther from the Sun, with very eccentric and inclined orbits. These orbits are non-resonant and non-planetary-orbit-crossing. A typical example is the most-massive-known TNO, Eris. Based on the Tisserand parameter relative to Neptune (TN), the objects in the scattered disc can be further divided into the "typical" scattered disc objects (SDOs, Scattered-near) with a TN of less than 3, and into the detached objects (ESDOs, Scattered-extended) with a TN greater than 3. In addition, detached objects have a time-averaged eccentricity greater than 0.2[12] The sednoids are a further extreme sub-grouping of the detached objects with perihelia so distant that it is confirmed that their orbits cannot be explained by perturbations from the giant planets,[13] nor by interaction with the galactic tides.[14] However, a passing star could have moved them on their orbit.[15]

الخصائص الفيزيائية

بما أن القدر الظاهري لمعظم الأجرام الوراء نبتونيّة هو 20 فما فوق، فإن الدراسات الفيزيائيّة لها تقتصر على الآتي:

- الانبعاثات الحرارية لأضخم الأجرام.

- دراسة الألوان ومقارنة الأقدار الظاهرية باستخدام مرشّحات (فلاتر) مختلفة.

- تحليل الطيف المرئي وطيف الأشعة تحت الحمراء.

دراسة الأطياف والألوان تسمح لنا بالتعرّف على تكوّن وبداية الأجرام الوراء نبتونيّة إضافة إلى الارتباطات بينها وبين أنواع أخرى من الأجرام، وهذه الأجرام هي بشكل أساسي كواكب القنطور الصغيرة وبعض أقمار الكواكب العملاقة (مثل ترايتون وفويب) التي يُمكن أن تكون قد تكوّنت بالأصل في حزام كويبر. لكن بالرغم من هذا، يُمكن أحياناً أن تلائم الأطياف أكثر من نموذج واحد لتركيب السطح (حيث أنه يتم تحليل التركيب الكيميائي للأجرام السماوية عن طريق المطيافية)، وما زالت التفسيرات المطروحة لهذا الأمر غير مقنعة أو واضحة. وفضلاً عن هذا، فالطبقة السطحيّة العليا لهذه الأجرام تتغيّر بعدة تأثيرات هي الأشعة القويّة الصادرة عن الشمس والرياح الشمسية والنيازك المجهرية. ونتيجة لهذا فإنها سوف تكون شديدة الاختلاف عن الطبقة التي تحتها مباشرة، ومن ثم فهي ليست مفيدة في تحديد التركيب العام لهذه الأجرام.

يُعتقد أن الأجرام الوراء نبتونيّة الصغيرة هي عبارة عن مزيج منخفض الكثافة من الصخور والجليد إضافة إلى بعض المواد العضوية (التي تحتوي الكربون) على السطح مثل الثولن (وقد كُشف عن هذه المواد العضوية بواسطة تحليل الطيف). ومن جهة أخرى، الكثافة العالية لهاوميا التي تعادل 2.6-3.3 غ/سم3 تشير إلى أنه يتكوّن بنسبة عالية جداً من مواد غير جليدية (مقارنة بكثافة بلوتو: 2.0 غ/سم3).

تركيب بعض الأجرام الوراء نبتونيّة الصغيرة يُمكن أن يكون مشابها لتركيب المذنبات. وفي الواقع فإن بعض القناطير (التي يُعتقد أنها كانت أجراماً وراء نبتونيّة في الأصل) تخضع لتغيّرات موسميّة عندما تقترب من الشمس وتُظهر ذؤابة مشابهة لتلك التي تظهرها المذنبات (ومن هذه القناطير 2060 كايرون). لكن بالرغم من هذا، المقارنة بين الخصائص الفيزيائية للقناطير والأجرام الوراء نبتونيّة ما تزال أمراً مثيراً للجدل.[16]

المؤشرات اللونية

Colour indices are simple measures of the differences in the apparent magnitude of an object seen through blue (B), visible (V), i.e. green-yellow, and red (R) filters.[17] Correlations between the colours and the orbital characteristics have been studied, to confirm theories of different origin of the different dynamic classes:

- Classical Kuiper belt objects (cubewanos) seem to be composed of two different colour populations: the so-called cold (inclination <5°) population, displaying only red colours, and the so-called hot (higher inclination) population displaying the whole range of colours from blue to very red.[18] A recent analysis based on the data from Deep Ecliptic Survey confirms this difference in colour between low-inclination (named Core) and high-inclination (named Halo) objects. Red colours of the Core objects together with their unperturbed orbits suggest that these objects could be a relic of the original population of the belt.[19]

- Scattered disc objects show colour resemblances with hot classical objects pointing to a common origin.

While the relatively dimmer bodies, as well as the population as the whole, are reddish (V−I = 0.3–0.6), the bigger objects are often more neutral in colour (infrared index V−I < 0.2). This distinction leads to suggestion that the surface of the largest bodies is covered with ices, hiding the redder, darker areas underneath.[20]

| اللون | پلوتينو | كوبوانو | القنطورات | أ.ق.م. | المذنبات | طروادات المشترى |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B–V | 0.895±0.190 | 0.973±0.174 | 0.886±0.213 | 0.875±0.159 | 0.795±0.035 | 0.777±0.091 |

| V–R | 0.568±0.106 | 0.622±0.126 | 0.573±0.127 | 0.553±0.132 | 0.441±0.122 | 0.445±0.048 |

| V–I | 1.095±0.201 | 1.181±0.237 | 1.104±0.245 | 1.070±0.220 | 0.935±0.141 | 0.861±0.090 |

| R–I | 0.536±0.135 | 0.586±0.148 | 0.548±0.150 | 0.517±0.102 | 0.451±0.059 | 0.416±0.057 |

النوع الطيفي من الأرصاد المرئية وقرب تحت الحمراء

Among TNOs, as among centaurs, there is a wide range of colors from blue-grey (neutral) to very red, but unlike the centaurs, bimodally grouped into grey and red centaurs, the distribution for TNOs appears to be uniform.[16] The wide range of spectra differ in reflectivity in visible red and near infrared. Neutral objects present a flat spectrum, reflecting as much red and infrared as visible spectrum.[22] Very red objects present a steep slope, reflecting much more in red and infrared. A recent attempt at classification (common with centaurs) uses the total of four classes from BB (blue, or neutral color, average B−V = 0.70, V−R = 0.39, e.g. Orcus) to RR (very red, B−V = 1.08, V−R = 0.71, e.g. Sedna) with BR and IR as intermediate classes. BR (intermediate blue-red) and IR (moderately red) differ mostly in the infrared bands I, J and H.

Typical models of the surface include water ice, amorphous carbon, silicates and organic macromolecules, named tholins, created by intense radiation. Four major tholins are used to fit the reddening slope:

- Titan tholin, believed to be produced from a mixture of 90% N2 (nitrogen) and 10% CH

4 (methane) - Triton tholin, as above but with very low (0.1%) methane content

- (ethane) Ice tholin I, believed to be produced from a mixture of 86% H

2O and 14% C2H6 (ethane) - (methanol) Ice tholin II, 80% H2O, 16% CH3OH (methanol) and 3% CO2

As an illustration of the two extreme classes BB and RR, the following compositions have been suggested

- for Sedna (RR very red): 24% Triton tholin, 7% carbon, 10% N2, 26% methanol, and 33% methane

- for Orcus (BB, grey/blue): 85% amorphous carbon, +4% Titan tholin, and 11% H2O ice

Spectral types after the James Webb Space Telescope

Recent observations with the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), and in particular its high sensitivity with the NIRSpec instrument in the 0.7–5.3 μm range, have led to a new spectral classification for trans-Neptunian objects (TNOs). This classification is based on the Discovering the Surface Composition of TNOs (DiSCo) Large program and, for the first time, incorporates not only spectral profiles but also how they relate to the surface composition of TNOs. Additionally to the discovery of species that had not been detected before, the most significant discoveries from the spectral study of TNOs with Webb is the prevalence of CO2 on the surface for TNOs, independently of the size, albedo, and color and the non-prevalence of water ice, clearly present only in 20% of the sample.[23]

The DiSCo compositional classes [23] show three distinct groups:

- Bowl-type: the only class with a clear absorption features of water ice all over the NIRSPEC spectral range, accompanied by silicates and some carbon dioxide (CO2). Due to the high presence of refractory material on the surface these objects show the lowest geometric albedo in the population.[23]

- Double-Dip: reddish objects in the visible with spectra dominated by CO2 (including the isotopologue 13CO2) and carbon monoxide (CO) The non-icy surface component is probably dominated by tholins with aliphatic stretching absorptions at 3.2 - 3.5 μm.[23][24][25]

- Cliff: the reddest objects below 1.2 μm, with chemically evolved surfaces dominated by methanol, CO2, CO, and irradiation byproducts of methanol bearing −OH, −CH and −NH groups.[26] These spectra also display additional complex bands, likely associated with OCN− and OCS.

The distribution of these groups shows no clear relation with physical parameters or dynamical class, except for the color in the visible and the fact that all cold classical TNOs belong to the Cliff class.[23] These three groups are also reproduced, with some differences, in centaurs[27](including active ones such as Chiron),[28] in Neptune trojans,[29] and in ETNOs,[30] making them a useful reference for icy bodies throughout the Solar System. Similarities have also been noted with debris disk spectra.[31]

As expected given their peculiar compositions, the dwarf planets Eris and Makemake[32] do not fall into any of these groups. The same is true for large (~1000 km) dwarf planet candidates such as Quaoar, Gonggong, and Sedna, which show distinctive spectral profiles with irradiation products of methane.[33]

تحديد الحجم والتوزيع

Characteristically, big (bright) objects are typically on inclined orbits, whereas the invariable plane regroups mostly small and dim objects.[20]

It is difficult to estimate the diameter of TNOs. For very large objects, with very well known orbital elements (like Pluto), diameters can be precisely measured by occultation of stars. For other large TNOs, diameters can be estimated by thermal measurements. The intensity of light illuminating the object is known (from its distance to the Sun), and one assumes that most of its surface is in thermal equilibrium (usually not a bad assumption for an airless body). For a known albedo, it is possible to estimate the surface temperature, and correspondingly the intensity of heat radiation. Further, if the size of the object is known, it is possible to predict both the amount of visible light and emitted heat radiation reaching Earth. A simplifying factor is that the Sun emits almost all of its energy in visible light and at nearby frequencies, while at the cold temperatures of TNOs, the heat radiation is emitted at completely different wavelengths (the far infrared).

Thus there are two unknowns (albedo and size), which can be determined by two independent measurements (of the amount of reflected light and emitted infrared heat radiation). TNOs are so far from the Sun that they are very cold, hence producing black-body radiation around 60 micrometres in wavelength. This wavelength of light is impossible to observe from the Earth's surface, but can be observed from space using, e.g. the Spitzer Space Telescope. For ground-based observations, astronomers observe the tail of the black-body radiation in the far infrared. This far infrared radiation is so dim that the thermal method is only applicable to the largest KBOs. For the majority of (small) objects, the diameter is estimated by assuming an albedo. However, the albedos found range from 0.50 down to 0.05, resulting in a size range of 1,200–3,700 km for an object of magnitude of 1.0.[34]

أشهر الأجرام

| الجرم | الوصف |

|---|---|

| پلوتو | كوكب قزم وأول جرم بعد نپتون يتم اكتشافه |

| (225088) 2007 OR10 | أكبر جرم في المجموعة الشمسية بدون اسم |

| 15760 ألبيون | نموذج [[Classical Kuiper belt object|لأجرام حزام كايپر الكلاسيكية، أول جرم يكتشف في حزام كايپر بعد پلوتو |

| 1998 WW31 | أول كوكب مزدوج في حزام كايپر يكتشف بعد پلوتو |

| 79360 Sila–Nunam | كوكب مزدجوج آخر في حزام كايپر بمناطق شبيهة |

| 47171 لمپو | تقريبا ثلاثة أضعاف كوكب حزام كايپر مع منطقتين متماثلتين وثالث أكبر قمر |

| (15874) 1996 TL66 | أول جرم يُحدد كجرم قرص متفرق |

| (48639) 1995 TL8 | له قمر ضخم للغاية وهو أول جرم قرص متفرق يتم اكتشافه |

| (385185) 1993 رو | ثاني پلوتينو يكتشف بعد پلوتو |

| 20000 ڤارونا | كوكب مزدوج كبير في حزام كايپر |

| 50000 كواور | كوكب مزدوج كبير في حزام كايپر |

| 90482 اوركوس | كوكب مزدوج كبير في حزام كايپر |

| 28978 إكسيون | كوكب مزدوج كبير في حزام كايپر |

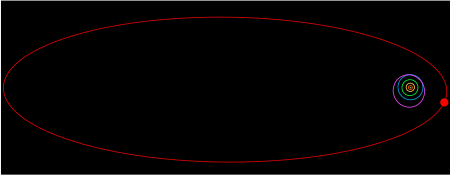

| 90377 سدنا | جرم بعيد، مقترح ليدخل ضمن التصنيف الجديد المسمى القرص المتفرق الممتد (E-SDO)،[35] الأجرام المنفصلة،[36] الأجرام المنفصلة البعيدة (DDO)[37] أو الموسعة-المنفصلة حسب التصنيف الرسمي DES[12] |

| 120347 سالاكيا | كوكب كبير مزدوج في حزام كايپر له قمر كبير |

| 136108 هوميا | كوكب قزم، ثالث أكبر جرم معروف بعد نپتون. يشتهر بقمريه المعروفين وفترة دورانه القصيرة للغاية (3.9 ساعة).[20] وهو العضو الأكثر شهرة ضمن العائلة التصادمية.[38][39][40] |

| 136199 إريس | كوكب قزم، جرم قرص متفرق، وحالياً، أكبر جرم معروف بعد نپتون. له ساتل واحد معروف، ديسنوميا. |

| ماكىماكى | كوكب قزم، جرم مزدوج في حزام كايپر، وخامس أكبر جرم معروف بعد نپتون.[41] |

| 136199 Eris | A dwarf planet, a scattered disc object, and currently the most massive known TNO. It has one known satellite, Dysnomia. |

| 6129112004 XR | A detached object whose orbit is highly inclined and lies outside the classical Kuiper belt. |

| 225088 Gonggong | A dwarf planet and the second-largest discovered scattered-disc object. Has one known satellite, Xiangliu. |

| (528219) 2008 KV42 | The first retrograde TNO, having an unusually high orbital inclination of 104°. |

| 471325 Taowu | Another retrograde TNO with an unusually high orbital inclination of 110°.[42] |

| 2012 VP113 | A sednoid with a large perihelion of 80 AU from the Sun (50 AU beyond Neptune). |

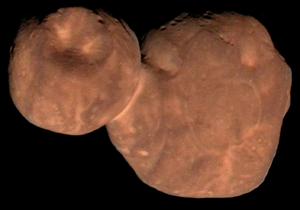

| 486958 أروكوث | A contact binary classical KBO encountered by the New Horizons spacecraft in 2019. |

| 2018 VG18 | A scattered disc object, and the first TNO discovered while beyond 100 AU (15 billion km) from the Sun. |

| 2018 AG37 | The most distant observable TNO at 132 AU (19.7 billion km) from the Sun. |

الاستكشاف

The only mission to date that primarily targeted a trans-Neptunian object was NASA's New Horizons, which was launched in January 2006 and flew by the Pluto system in July 2015[43] and 486958 Arrokoth in January 2019.[44]

In 2011, a design study explored a spacecraft survey of Quaoar, Sedna, Makemake, Haumea, and Eris.[45]

In 2019 one mission to TNOs included designs for orbital capture and multi-target scenarios.[46][47]

Some TNOs that were studied in a design study paper were Uni, 1998 WW31, and Lempo.[47]

The existence of planets beyond Neptune, ranging from less than an Earth mass (Sub-Earth) up to a brown dwarf has been often postulated[48][49] for different theoretical reasons to explain several observed or speculated features of the Kuiper belt and the Oort cloud. It was recently proposed to use ranging data from the New Horizons spacecraft to constrain the position of such a hypothesized body.[50]

NASA has been working towards a dedicated Interstellar Precursor in the 21st century, one intentionally designed to reach the interstellar medium, and as part of this the flyby of objects like Sedna are also considered.[51] Overall this type of spacecraft studies have proposed a launch in the 2020s, and would try to go a little faster than the Voyagers using existing technology.[51] One 2018 design study for an Interstellar Precursor, included a visit of minor planet 50000 Quaoar, in the 2030s.[52]

الأجرام القصوى بعد نپتون

Among the extreme trans-Neptunian objects are high-perihelion objects classified as sednoids, four of which have been confirmed: 90377 Sedna, 2012 VP113, 541132 Leleākūhonua, and 2023 KQ14. They are distant detached objects with perihelia greater than 70 AU. Their high perihelia keep them at a sufficient distance to avoid significant gravitational perturbations from Neptune. Previous explanations for the high perihelion of Sedna include a close encounter with an unknown planet on a distant orbit and a distant encounter with a random star or a member of the Sun's birth cluster that passed near the Solar System.[53][54][55]

انظر أيضاً

- كوكب قزم

- Mesoplanet

- نمسيس (نجم افتراضي)

- الكوكب العاشر

- Sednoid

- جسم صغير في النظام الشمسي

- تريتون

- Tyche (hypothetical planet)

الهوامش

- ^ أ ب The literature is inconsistent in the use of the phrases "scattered disc" and "Kuiper belt". For some, they are distinct populations; for others, the scattered disk is part of the Kuiper belt, in which case the low-eccentricity population is called the "classical Kuiper belt". Authors may even switch between these two uses in a single publication.[1]

المصادر

- ^ McFadden, Weissman, & Johnson (2007). Encyclopedia of the Solar System, footnote p. 584

- ^ "List Of Transneptunian Objects". Minor Planet Center. Retrieved 23 October 2018.

- ^ "List Of Centaurs and Scattered-Disk Objects". Minor Planet Center. 8 October 2018. Retrieved 23 October 2018.

- ^ "List of Known Trans-Neptunian Objects". Johnston's Archive. 7 October 2018. Retrieved 23 October 2018.

- ^ "JPL Small-Body Database Search Engine: orbital class (TNO)". JPL Solar System Dynamics. Retrieved 2014-07-10.

- ^ "JPL Small-Body Database Search Engine: orbital class (TNO) and q > 30.1 (AU)". Retrieved 2014-07-11.

- ^ C. de la Fuente Marcos; R. de la Fuente Marcos (September 1, 2014). "Extreme trans-Neptunian objects and the Kozai mechanism: signalling the presence of trans-Plutonian planets". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 443 (1): L59–L63. arXiv:1406.0715. Bibcode:2014MNRAS.443L..59D. doi:10.1093/mnrasl/slu084.

- ^ Gebhardt, Chris; Goldader, Jeff (20 August 2011). "Thirty-four years after launch, Voyager 2 continues to explore". NASA Spaceflight (nasaspaceflight.com) (Press release).

- ^ Cory Shankman; et al. (Feb 10, 2013). "A Possible Divot in the Size Distribution of the Kuiper Belt's Scattering Objects". Astrophysical Journal Letters. 764 (1): L2. arXiv:1210.4827. Bibcode:2013ApJ...764L...2S. doi:10.1088/2041-8205/764/1/L2. S2CID 118644497.

- ^ Shankman, C.; Kavelaars, J. J.; Gladman, B. J.; Alexandersen, M.; Kaib, N.; Petit, J.-M.; Bannister, M. T.; Chen, Y.-T.; Gwyn, S.; Jakubik, M.; Volk, K. (2016). "OSSOS. II. A Sharp Transition in the Absolute Magnitude Distribution of the Kuiper Belt's Scattering Population". The Astronomical Journal. 150 (2): 31. arXiv:1511.02896. Bibcode:2016AJ....151...31S. doi:10.3847/0004-6256/151/2/31. S2CID 55213074.

- ^ Brett Gladman; et al. (2008). The Solar System Beyond Neptune. p. 43.

- ^ أ ب Elliot, J. L.; Kern, S. D.; Clancy, K. B.; Gulbis, A. A. S.; Millis, R. L.; Buie, M. W.; Wasserman, L. H.; Chiang, E. I.; Jordan, A. B.; Trilling, D. E.; Meech, K. J. (2005). "The Deep Ecliptic Survey: A Search for Kuiper Belt Objects and Centaurs. II. Dynamical Classification, the Kuiper Belt Plane, and the Core Population". The Astronomical Journal. 129 (2): 1117–1162. Bibcode:2005AJ....129.1117E. doi:10.1086/427395.

- ^ Brown, Michael E.; Trujillo, Chadwick A.; Rabinowitz, David L. (2004). "Discovery of a Candidate Inner Oort Cloud Planetoid" (PDF). Astrophysical Journal. 617 (1): 645–649. arXiv:astro-ph/0404456. Bibcode:2004ApJ...617..645B. doi:10.1086/422095. S2CID 7738201. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-06-27. Retrieved 2008-04-02.

- ^ Trujillo, Chadwick A.; Sheppard, Scott S. (2014). "A Sedna-like body with a perihelion of 80 astronomical units" (PDF). Nature. 507 (7493): 471–474. Bibcode:2014Natur.507..471T. doi:10.1038/nature13156. PMID 24670765. S2CID 4393431. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2014-12-16.

- ^ Pfalzner, Susanne; Govind, Amith; Portegies Zwart, Simon (2024-09-04). "Trajectory of the stellar flyby that shaped the outer Solar System". Nature Astronomy (in الإنجليزية). 8 (11): 1380–1386. arXiv:2409.03342. Bibcode:2024NatAs...8.1380P. doi:10.1038/s41550-024-02349-x. ISSN 2397-3366.

- ^ أ ب N. Peixinho, A. Doressoundiram, A. Delsanti, H. Boehnhardt, M. A. Barucci, and I. Belskaya Reopening the TNOs Color Controversy: Centaurs Bimodality and TNOs Unimodality Astronomy and Astrophysics, 410, L29-L32 (2003). Preprint on arXiv Archived 2016-10-05 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Hainaut, O. R.; Delsanti, A. C. (2002). "Color of Minor Bodies in the Outer Solar System". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 389 (2): 641–664. Bibcode:2002A&A...389..641H. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20020431. datasource

- ^ Doressoundiram, A.; Peixinho, N.; de Bergh, C.; Fornasier, S.; Thébault, Ph.; Barucci, M. A.; Veillet, C. (2002). "The color distribution in the Edgeworth-Kuiper Belt". The Astronomical Journal. 124 (4): 2279–2296. arXiv:astro-ph/0206468. Bibcode:2002AJ....124.2279D. doi:10.1086/342447. S2CID 30565926.

- ^ Gulbis, Amanda A. S.; Elliot, J. L.; Kane, Julia F. (2006). "The color of the Kuiper belt Core". Icarus. 183 (1): 168–178. Bibcode:2006Icar..183..168G. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2006.01.021.

- ^ أ ب ت Rabinowitz, David L.; Barkume, K. M.; Brown, Michael E.; Roe, H. G.; Schwartz, M.; Tourtellotte, S. W.; Trujillo, C. A. (2006). "Photometric Observations Constraining the Size, Shape, and Albedo of 2003 El61, a Rapidly Rotating, Pluto-Sized Object in the Kuiper Belt". Astrophysical Journal. 639 (2): 1238–1251. arXiv:astro-ph/0509401. Bibcode:2006ApJ...639.1238R. doi:10.1086/499575. S2CID 11484750. خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صالح؛ الاسم "Rabinowitz 2005" معرف أكثر من مرة بمحتويات مختلفة. - ^ Fornasier, S.; Dotto, E.; Hainaut, O.; Marzari, F.; Boehnhardt, H.; De Luise, F.; et al. (October 2007). "Visible spectroscopic and photometric survey of Jupiter Trojans: Final results on dynamical families" (PDF). Icarus. 190 (2): 622–642. arXiv:0704.0350. Bibcode:2007Icar..190..622F. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2007.03.033.

- ^ A. Barucci Trans Neptunian Objects’ surface properties, IAU Symposium No. 229, Asteroids, Comets, Meteors, Aug 2005, Rio de Janeiro

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةPinilla-Alonso-2025 - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةDePra-2025 - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةHenault-2025 - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةBrunetto-2025 - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةLicandro-2025 - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةPinilla-Alonso-2024 - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةMarkwardt-2025 - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةHoller-2024 - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةXie-2025 - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةGrundy-2024 - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةEmery-2024 - ^ "Conversion of Absolute Magnitude to Diameter". Minorplanetcenter.org. Retrieved 2013-10-07.

- ^ "Evidence for an Extended Scattered Disk?". obs-nice.fr.

- ^ Jewitt, D.; Delsanti, A. (2006). "The Solar System Beyond The Planets". Solar System Update : Topical and Timely Reviews in Solar System Sciences (Springer-Praxis ed.). ISBN 3-540-26056-0.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - ^ Gomes, Rodney S.; Matese, John J.; Lissauer, Jack J. (2006). "A Distant Planetary-Mass Solar Companion May Have Produced Distant Detached Objects" (PDF). Icarus. 184 (2): 589–601. Bibcode:2006Icar..184..589G. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2006.05.026. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-01-08.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Brown, Michael E.; Barkume, Kristina M.; Ragozzine, Darin; Schaller, Emily L. (2007). "A collisional family of icy objects in the Kuiper belt". Nature. 446 (7133): 294–296. Bibcode:2007Natur.446..294B. doi:10.1038/nature05619. PMID 17361177.

- ^ de la Fuente Marcos, Carlos; de la Fuente Marcos, Raúl (11 February 2018). "Dynamically correlated minor bodies in the outer Solar system". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 474 (1): 838–846. arXiv:1710.07610. Bibcode:2018MNRAS.474..838D. doi:10.1093/mnras/stx2765.

- ^ "Distant object found orbiting Sun". BBC News. 2005-07-29. Retrieved 2010-03-28.

- ^ "MPEC 2005-O42 : 2005 FY9". Minorplanetcenter.org. Retrieved 2013-10-07.

- ^ "Mystery object in weird orbit beyond Neptune cannot be explained". New Scientist. 2016-08-10. Retrieved 2016-08-11.

- ^ Talbert, Tricia (25 March 2015). "NASA New Horizons Mission Page". NASA.

- ^ "New Horizons: News Article?page=20190101". pluto.jhuapl.edu. Retrieved 2019-01-01.

- ^ "A Survey of Mission Opportunities to Trans-Neptunian Objects". ResearchGate (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2019-09-23.

- ^ Low-Cost Opportunity for Multiple Trans-Neptunian Object Rendezvous and Capture, AAS Paper 17-777.

- ^ أ ب "AAS 17-777 Low-cost Opportunity for Multiple Trans-Neptunian Object Rendezvous and Orbital Capture". ResearchGate (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2019-09-23.

- ^ Julio A., Fernández (January 2011). "On the Existence of a Distant Solar Companion and its Possible Effects on the Oort Cloud and the Observed Comet Population". The Astrophysical Journal. 726 (1): 33. Bibcode:2011ApJ...726...33F. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/726/1/33. S2CID 121392983.

- ^ Patryk S., Lykawka; Tadashi, Mukai (April 2008). "An Outer Planet Beyond Pluto and the Origin of the Trans-Neptunian Belt Architecture". The Astronomical Journal. 135 (4): 1161–1200. arXiv:0712.2198. Bibcode:2008AJ....135.1161L. doi:10.1088/0004-6256/135/4/1161. S2CID 118414447.

- ^ Lorenzo, Iorio (August 2013). "Perspectives on effectively constraining the location of a massive trans-Plutonian object with the New Horizons spacecraft: a sensitivity analysis". Celestial Mechanics and Dynamical Astronomy. 116 (4): 357–366. arXiv:1301.3831. Bibcode:2013CeMDA.116..357I. doi:10.1007/s10569-013-9491-x. S2CID 119219926.

- ^ أ ب David, Leonard (9 January 2019). "A Wild 'Interstellar Probe' Mission Idea Is Gaining Momentum". Space.com (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2025-04-22.

- ^ Bradnt, P.C.; et al. "The Interstellar Probe Mission (Graphic Poster)" (PDF). hou.usra.edu. Retrieved October 13, 2019.

- ^ Wall, Mike (24 August 2011). "A Conversation With Pluto's Killer: Q & A With Astronomer Mike Brown". Space.com. Retrieved 7 February 2016.

- ^ Brown, Michael E.; Trujillo, Chadwick; Rabinowitz, David (2004). "Discovery of a Candidate Inner Oort Cloud Planetoid". The Astrophysical Journal. 617 (1): 645–649. arXiv:astro-ph/0404456. Bibcode:2004ApJ...617..645B. doi:10.1086/422095. S2CID 7738201.

- ^ Brown, Michael E. (28 October 2010). "There's something out there – part 2". Mike Brown's Planets. Retrieved 18 July 2016.

وصلات خارجية

- الكوكب العاشر University of Arizona

- David Jewitt's Kuiper Belt site

- A list of the estimates of the diameters from johnstonarchive with references to the original papers