رسالة بطرس الأولى

| أسفار العهد الجديد |

|---|

|

| الأناجيل |

| متى • مرقص • لوقا • يوحنا |

| الأعمال |

| أعمال الرسل |

| الرسائل |

|

الرومان 1 كورنثوس • 2 كورنثوس غلاطية • إفسس فيلپي • كولوسي 1 تسالونيكي • 2 تسالونيكي 1 تيموثاوس • 2 تيموثاوس تيطس • فيلمون العبرانيين • يعقوب 1 بطرس • 2 بطرس 1 يوحنا • 2 يوحنا • 3 يوحنا يهوذا |

| أپوكالپس |

| الرؤيا |

| مخطوطات العهد الجديد |

رسالة بطرس الأولى هي إحدى أحد أسفار العهد الجديد التي تصنف ضمن رسائل الكاثوليكون ، الرسالة موجهة من ( بُطْرُسُ، رَسُولُ يَسُوعَ الْمَسِيحِ، إِلَى الْمُتَغَرِّبِينَ مِنْ شَتَاتِ بُنْتُسَ وَغَلاَطِيَّةَ وَكَبَّدُوكِيَّةَ وَأَسِيَّا وَبِيثِينِيَّةَ ) [2] ، أي أنها كتبت للمسيحيين الذين تشتتوا في مدن ومقاطعات آسيا الصغرى ، وبحسب المصادر المسيحية فأن كاتب الرسالة هو بطرس الرسول الذي يعتبر المتقدم بين رسل المسيح الإثنا عشر . ويُعتقد أنها كتبت مابين عامي 63 م و 67 م أي في فترة الاضطهاد الذي أثاره نيرون قيصر روما ضد المسيحيين ( 54 م – 68 م ) .

تأليف الرسالة

The authorship of 1 Peter has traditionally been attributed to the Apostle Peter because it bears his name and identifies him as its author (1:1). Although the text identifies Peter as its author, the language, dating, style, and structure of this letter have led most scholars to conclude that it is pseudonymous.[3][4][5] With 1 Peter being considered a positive example of early Christian pseudonymity practices.[6] Many scholars argue that Peter was not the author of the letter because its writer appears to have had a formal education in rhetoric and philosophy, and an advanced knowledge of the Greek language,[7] none of which would be usual for a Galilean fisherman.

New Testament scholar Graham Stanton rejects Petrine authorship because 1 Peter was most likely written during the reign of Domitian in AD 81, which is when he believes widespread Christian persecution began, which is long after the death of Peter.[8][صفحة مطلوبة] More recent scholars such as Travis Williams say that the persecution described does not appear to be describing official Roman persecutions after Peter's death, thus not directly ruling out an early date for the composition of the epistle.[9]

Another dating issue is the reference to "Babylon" in chapter 5 verse 13, generally agreed to be a claim the letter was written from Rome. It is believed that the identification of Rome with Babylon, the ancient enemy of the Jews, only came after the destruction of the Temple in AD 70.[10] Other scholars doubt Petrine authorship because they are convinced that 1 Peter is dependent on the Pauline epistles and thus was written after Paul the Apostle's ministry because it shares many of the same motifs espoused in Ephesians, Colossians, and the Pastoral Epistles.[11]

Others argue that it makes little sense to ascribe the work to Peter when it could have been ascribed to Paul.[9] Alternatively, one theory supporting legitimate Petrine authorship of 1 Peter is the "secretarial hypothesis", which suggests that 1 Peter was dictated by Peter and was written in Greek by his secretary, Silvanus (5:12). John Elliott disagrees, suggesting that the notion of Silvanus as secretary or author or drafter of 1 Peter introduces more problems than it solves, and claims that the Greek rendition of 5:12 suggests that Silvanus was not the secretary, but the courier/bearer of 1 Peter.[12] Like English translations generally, the more recent NRSVUE (2021) translation of this verse from the Greek does not exclude understanding Silvanus as secretary: "Through Silvanus, whom I consider a faithful brother, I have written this short letter to encourage you and to testify that this is the true grace of God. Stand fast in it." Some see Mark as a contributive amanuensis in the composition and writing of the work.[13][14]

On the one hand, some scholars such as Bart D. Ehrman are convinced that the language, dating, literary style, and structure of this text makes it implausible to conclude that 1 Peter was written by Peter.[10] According to these scholars, it is more likely that 1 Peter is a pseudonymous letter, written later by an unknown Christian in his name.

On the other hand, some scholars argue that there is enough evidence to conclude that Peter did, in fact, write 1 Peter. For instance, there are similarities between 1 Peter and Peter's speeches in the Biblical book of Acts,[15] allusions to several historical sayings of Jesus indicative of eyewitness testimony (e.g., compare Luke 12:35 with 1 Peter 1:13, Matthew 5:16 with 1 Peter 2:12, and Matthew 5:10 with 1 Peter 3:14),[16] and early attestation of Peter's authorship found in 2 Peter (AD 60–160)[17] and the letters of Clement (AD 70–140),[9] all supporting genuine Petrine origin. Atheist scholar Richard Carrier claims that the Epistle dates to the 60s AD and that it may be authentic: he asserts as possible that Peter being an illiterate fisherman was a later invention of the evangelists, and that the historical Peter (attested for in the authentic Pauline epistles, which never mention Peter's economic status and education) was actually a learned hellenized Jew.[18] Ultimately, the authorship of 1 Peter remains contested.

مكان كتابة الرسالة

يذكر كاتب الرسالة بأنه كتبها في "بابل المختارة" [19] ، ومن شبه المؤكد بأن بابل هذه ليست مدينة بابل التاريخية الواقعة على نهر الفرات لأنها في تلك الفترة كانت مدمرة وغير مسكونة . وبحسب التقليد الكاثوليكي فأن اسم بابل عاصمة العالم القديم كان الاسم الرمزي لروما عاصمة العالم الجديدة – بالنسبة لذلك الوقت – لذلك فأن بطرس كتب رسالته في روما ولكن هناك آراء لباحثين كثر تناقض هذا الاعتقاد ، ويوجد آراء أخرى تقول بأن بابل هذه لم تكن سوى مدينة بابلون في مصر القديمة ويؤيد هذا الرأي تقليد الكنيسة القبطية الأرثوذوكسية .

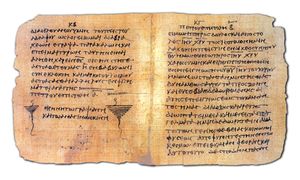

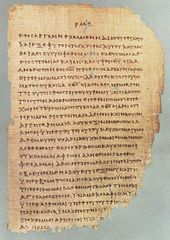

أقدم مخطوطات باقية

The original manuscript of this letter is lost, as are several centuries of copies. The text of the surviving manuscripts varies. The oldest surviving manuscripts that contain some or all of this book include:

- بالقبطية

- Crosby–Schøyen Codex MS 193 (3rd century)[20]

- In Greek

- Papyrus 72 (3rd/4th century)

- Papyrus 125 (3rd/4th century)

- Papyrus 81 (4th century)

- Codex Vaticanus (325–350)

- Codex Sinaiticus (330–360)

- Codex Alexandrinus (400–440)

- Codex Ephraemi Rescriptus (ca. 450)

- Papyrus 74 (7th century)

- In Latin

- León palimpsest (7th century)[21]

المتلقّون

1 Peter is addressed to the "elect resident aliens" scattered throughout Pontus, Galatia, Cappadocia, Asia, and Bithynia. The five areas listed in 1:1 as the geographical location of the first readers were Roman provinces in Asia Minor. The order in which the provinces are listed may reflect the route to be taken by the messenger who delivered the circular letter. The recipients of this letter are referred to in 1:1 as "exiles of the Dispersion". In 1:17, they are urged to "live in reverent fear during the time of your exile".[8][صفحة مطلوبة] The social makeup of the addressees of 1 Peter is debatable because some scholars interpret "strangers" (1:1) as Christians longing for their home in heaven, some interpret it as literal "strangers", or as an Old Testament adaptation applied to Christian believers.[8][صفحة مطلوبة]

While the new Christians have encountered oppression and hostility from locals, Peter advises them to maintain loyalty both to their religion and the Roman Empire (1 Peter 2:17).[22]

The author counsels (1) to steadfastness and perseverance under persecution (1–2:10); (2) to the practical duties of a holy life (2:11–3:13); (3) he adduces the example of Christ and other motives to patience and holiness (3:14–4:19); and (4) concludes with counsels to pastors and people (chap. 5).

مضمون الرسالة

- الرجاء الحي بالله لنيل الخلاص [23]

- دعو المؤمنين للقداسة [24]

- المسيح هو حجر الزاوية [25]

- الخضوع للسلطات الزمنية [26]

- العلاقة بين الزوجين المؤمنين [27]

- ضرورة تحمل الآلام في سبيل التقرب من الله [28]

- تشجيع المؤمنين على احتمال الضيقات على غرار ما فعل المسيح في سبيل مجد الله [29]

- دعوة للإشتراك في آلام المسيح [30]

- وصايا لشيوخ وشبيبة الكنيسة [31]

- تحيات ختامية [32]

السياق

The Petrine author writes of his addressees undergoing "various trials" (1 Peter 1:6), being "tested by fire" (which is not a physical reference but a metaphor for spiritual warfare; 1:7), maligned "as evildoers" (2:12) and suffering "for doing good" (3:17). Based on such internal evidence, biblical scholar John Elliott summarizes the addressees' situation as one marked by undeserved suffering.[33][صفحة مطلوبة] Verse 3:19, "Spirits in prison", is a continuing theme in Christianity, and one considered by most theologians to be enigmatic and difficult to interpret.[34]

A number of verses in the epistle contain possible clues about the reasons Christians experienced opposition. Exhortations to live blameless lives (2:15; 3:9, 13, 16) may suggest that the Christian addressees were accused of immoral behavior, and exhortations to civil obedience (2:13–17) perhaps imply that they were accused of disloyalty to governing powers.[7]

However, scholars differ on the nature of persecution inflicted on the addressees of 1 Peter. Some read the epistle to be describing persecution in the form of social discrimination, while some read them to be official persecution.[35]

التمييز الاجتماعي ضد المسيحيين

Some scholars believe that the sufferings the epistle's addressees were experiencing were social in nature, specifically in the form of verbal derision.[33][صفحة مطلوبة] Internal evidence for this includes the use of words like "malign" (2:12; 3:16), and "reviled" (4:14). Biblical scholar John Elliott notes that the author explicitly urges the addressees to respect authority (2:13) and even honor the emperor (2:17), strongly suggesting that they were unlikely to be suffering from official Roman persecution. It is significant to him that the author notes that "your brothers and sisters in all the world are undergoing the same kinds of suffering" (5:9), indicating suffering that is worldwide in scope. Elliott sees this as grounds to reject the idea that the epistle refers to official persecution, because the first worldwide persecution of Christians officially meted by Rome did not occur until the persecution initiated by Decius in AD 250.

الاضطهاد الرسمي للمسيحيين

On the other hand, scholars who support the official persecution theory take the exhortation to defend one's faith (3:15) as a reference to official court proceedings.[7] They believe that these persecutions involved court trials before Roman authorities, and even executions.[citation needed]

One common supposition is that 1 Peter was written during the reign of Domitian (AD 81–96). Domitian's aggressive claim to divinity would have been rejected and resisted by Christians. Biblical scholar Paul Achtemeier believes that persecution of Christians by Domitian would have been in character, but points out that there is no evidence of official policy targeted specifically at Christians. If Christians were persecuted, it is likely to have been part of Domitian's larger policy suppressing all opposition to his self-proclaimed divinity.[7] There are other scholars who explicitly dispute the idea of contextualizing 1 Peter within Domitian's reign. Duane Warden believes that Domitian's unpopularity even among Romans renders it highly unlikely that his actions would have great influence in the provinces, especially those under the direct supervision of the senate such as Asia (one of the provinces 1 Peter is addressed to).[36]

Also often advanced as a possible context for 1 Peter is the trials and executions of Christians in the Roman province of Bithynia-Pontus under Pliny the Younger. Scholars who support this theory believe that a famous letter from Pliny to Emperor Trajan concerning the delation of Christians reflects the situation faced by the addressees of this epistle.[37][38] In Pliny's letter, written in AD 112, he asks Trajan if the accused Christians brought before him should be punished based on the name 'Christian' alone, or for crimes associated with the name. For biblical scholar John Knox, the use of the word "name" in 4:14–16 is the "crucial point of contact" with that in Pliny's letter.[37] In addition, many scholars in support of this theory believe that there is content within 1 Peter that directly mirrors the situation as portrayed in Pliny's letter. For instance, they interpret the exhortation to defend one's faith "with gentleness and reverence" in 3:15–16 as a response to Pliny executing Christians for the obstinate manner in which they professed to be Christians. Generally, this theory is rejected mainly by scholars who read the suffering in 1 Peter to be caused by social, rather than official, discrimination.[39]

The Harrowing of Hell

The author refers to Jesus, after his death, proclaiming to spirits in prison (3:18–20). This passage, and a few others (such as Matthew 27:52 and Luke 23:43), are the basis of the traditional Christian belief in the descent of Christ into hell, or the harrowing of hell.[40] Though interpretations vary, some theologians[من؟] see this passage as referring to Jesus, after his death, going to a place (neither heaven nor hell in the ultimate sense) where the souls of pre-Christian people waited for the Gospel. The first creeds to mention the harrowing of hell were Arian formularies of Sirmium (359), Nike (360), and Constantinople (360). It spread through the West and later appeared in the Apostles' Creed.[40]

خضوع النساء

1 Peter 3:1 instructs women to submit to their husbands, "so that, even if some of them do not obey the Word, they may be won over without a word by their wives' conduct, when they see the purity and reverence of your lives."[41] The author also instructs husbands to "show consideration for your wives in your life together" and pay honor to them, "since they too are also heirs of the gracious gift of life—so that nothing may hinder your prayers."[42]

مواضيع ذات صلة

- بطرس

- رسالة بطرس الثانية

- رسائل الكاثوليكون

- Textual variants in the First Epistle of Peter

- Spirits in prison, 3:19.

ملاحظات

المراجع

- ^ Aland, Kurt; Aland, Barbara (1995). The Text of the New Testament: An Introduction to the Critical Editions and to the Theory and Practice of Modern Textual Criticism (in الإنجليزية). Translated by Rhodes, Erroll F. (2nd ed.). Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co. p. 159. ISBN 978-0-8028-4098-1. Archived from the original on October 5, 2023.

- ^ ( 1 : 1 )

- ^ Moyise, Steve (9 December 2004). The Old Testament in the New. A&C Black. p. 116. ISBN 978-0-567-08199-5.

- ^ Stephen L. Harris (1992). Understanding the Bible. Mayfield. p. 388. ISBN 978-1-55934-083-0.

Most scholars believe that 1 Peter is pseudonymous (written anonymously in the name of a well-known figure) and was produced during postapostolic times.

- ^ Dale Martin 2009 (lecture). "24. Apocalyptic and Accommodation" at YouTube. Yale University. Accessed 22 July 2013. Lecture 24 (transcript)

- ^ M. Eugene Boring, ‘First Peter in Recent Study’, WW 24 (2004), First Peter in Recent Study.pdf

- ^ أ ب ت ث Achtemeier, Paul. Peter 1 Hermeneia. Fortress Press. 1996

- ^ أ ب ت Stanton 2003.

- ^ أ ب ت Williams 2012, pp. 28–.

- ^ أ ب Ehrman, Bart D. (2011). Forged. HarperOne, HarperCollins. pp. 65–77. ISBN 978-0-06-201262-3.

- ^ Bartlett, David, New Interpreter's Bible Commentary, 1 Peter. Abingdon Press. 1998

- ^ Elliott, John. 1 Peter: Anchor Bible Commentary. Yale University Press. 2001.

- ^ Williams 2012, pp. 25–.

- ^ Moon, Jongyoon (2009). Mark As Contributive Amanuensis of 1 Peter?. Münster: LIT. ISBN 978-3-643-10428-1.

- ^ Daniel Keating, First and Second Peter Jude (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2011) 18. Norman Hillyer, 1 and 2 Peter, Jude, New International Biblical Commentary (Peabody, MA: Henrickson, 1992), 1–3. Karen H. Jobes, 1 Peter (Grand Rapids: Baker, 2005), 14–19.

- ^ Lane, Dennis; Schreiner, Thomas (2016). "Introduction to 1 Peter". ESV Study Bible. Wheaton, IL: Crossway. p. 2401.

- ^ Bauckham, RJ (1983), Word Bible Commentary, Vol. 50, Jude – 2 Peter, Waco

- ^ قالب:Cite work

- ^ ( 5 : 13 )

- ^ "MS 193 - The Schoyen Collection". www.schoyencollection.com. Retrieved 2025-10-06.

- ^ Bruce M. Metzger, The Early Versions of the New Testament, Oxford University Press, 1977, p. 316.

- ^ W. R. F. Browning. 10 May 2012. "Peter, first letter of", A Dictionary of the Bible. Oxford Reference Online. Oxford University Press. University of Chicago.

- ^ ( 1 : 1 – 12 )

- ^ ( 1 : 13 – 25 )

- ^ ( 2 : 1 – 10 )

- ^ ( 2 : 11 – 25 )

- ^ ( 3 : 1 – 6 )

- ^ ( 3 : 7 – 22 )

- ^ ( 4 : 1 – 11 )

- ^ ( 4 : 12 – 19 )

- ^ ( 5 : 1 – 11 )

- ^ ( 5 : 12 – 14 )

- ^ أ ب Elliott 2000.

- ^ Preached to the spirits in prison: I Peter iii:18–20, http://www.christianmonthlystandard.com/index.php/preached-to-the-spirits-in-prison-1-peter-318-20/, retrieved on 3 October 2016.

- ^ Mason, Eric F.; Martin, Troy W. (2014). Reading 1–2 Peter and Jude : A Resource for Students. Atlanta, GA: Society of Biblical Literature. pp. 16–17. ISBN 978-1-58983737-9.

- ^ Warden, Duane. "Imperial Persecution and the Dating of 1 Peter and Revelation". Journal of the Evangelical Theological Society 34:2. 1991

- ^ أ ب Knox, John. "Pliny and I Peter: A Note on I Peter 4:14–16 and 3:15". Journal of Biblical Literature 72:3. 1953

- ^ Downing, F Gerald. "Pliny's Prosecutions of Christians: Revelation and 1 Peter". Journal for the Study of the New Testament 34. 1988

- ^ Ferguson, Everett. "Persecution in the Early Church: Did You Know?". Christian History | Learn the History of Christianity & the Church (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 2024-02-08.

- ^ أ ب Cross, F. L. 2005, ed. "Descent of Christ into Hell." The Oxford dictionary of the Christian church. New York: Oxford University Press.

- ^ Peter%203:1–2&verse={{{3}}}&src=! 1 Peter 3:1–2 {{{3}}}

- ^ Peter%203:7&verse={{{3}}}&src=! 1 Peter 3:7 {{{3}}}

وصلات خارجية

![]() تعريفات قاموسية في ويكاموس

تعريفات قاموسية في ويكاموس

![]() كتب من معرفة الكتب

كتب من معرفة الكتب

![]() اقتباسات من معرفة الاقتباس

اقتباسات من معرفة الاقتباس

![]() نصوص مصدرية من معرفة المصادر

نصوص مصدرية من معرفة المصادر

![]() صور و ملفات صوتية من كومونز

صور و ملفات صوتية من كومونز

![]() أخبار من معرفة الأخبار.

أخبار من معرفة الأخبار.

ترجمات أونلاين لرسالة بطرس الأولى

- NET Bible 1 Peter Bible Text, Study notes, Greek, with audio link

- Early Christian writings: 1 Peter

- Online Bible at GospelHall.org

- قالب:Librivox book Various versions

- Multiple bible versions at Bible Gateway (NKJV, NIV, NRSV etc.)

أخرى

- The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia: 1 Peter

- Easton's Bible Dictionary 1897: First Epistle of Peter

- Ernst R. Wendland, "Stand Fast in the True Grace of God! A Study of 1 Peter"

- 1 Peter The authenticity and authorship by Peter of the First Epistle of Peter defended

- BibleProject Animated Overview (Evangelical Perspective)

رسالة بطرس الأولى

| ||

| سبقه James |

New Testament Books of the Bible |

تبعه Second Peter |

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Missing redirects

- مقالات بالمعرفة بحاجة لذكر رقم الصفحة بالمصدر from April 2022

- Articles with unsourced statements from October 2016

- جميع المقالات الحاوية على عبارات مبهمة

- جميع المقالات الحاوية على عبارات مبهمة from June 2012

- رسالة بطرس الأولى

- New Testament books

- Petrine-related books

- Catholic epistles