منبج

منبج | |

|---|---|

مدينة | |

جسر منبج | |

ناحية منبج | |

| الإحداثيات: 36°31′41″N 37°57′17″E / 36.52806°N 37.95472°E | |

| البلد | |

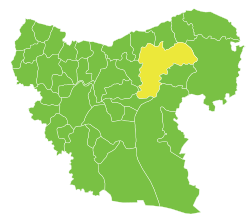

| المحافظة | محافظة حلب |

| المنطقة | منبج |

| ناحية | منبج |

| الأحياء | |

| المنسوب | 460 m (1٬510 ft) |

| التعداد (2004)[1] | |

| • الإجمالي | 99٬497 |

منبج، هي مدينة قديمة تقع إلى الغرب من نهر الفرات في منطقة منبج، محافظة حلب، سوريا. وهي واحدة من أقدم المدن السورية، ويتبعها ثلاث نواح، هي؛ أبو قلقل والخفسة ومسكنة، و285 قرية و351 مزرعة. [2]

أصل الاسم

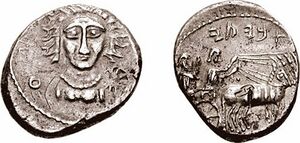

Coins struck at the city before Alexander's conquest record the Aramean name of the city as Mnbg (meaning spring site).[3] For the Assyrians it was known as Nappigu (Nanpigi).[4] The place appears in Greek as Bambyce (Βαμβυκη) and Pliny (v. 23) recorded its Syriac name as Mabog (ܡܒܘܓ) (also Mabbog, Mabbogh). As a center of the worship of the Syrian goddess Atargatis, it became known to the Greeks as Ιερόπολις (Ierópolis) 'city of the sanctuary', and finally as Ιεράπολις (Ierápolis) 'holy city' (in لاتينية: Hierapolis).[5]

الموقع

تقع في أرض منبسطة تنحدر نحو الفرات شرقاً وباتجاه أبو قلقل في الجنوب ونهر الساجور في الشمال، ترتفع عن سطح البحر 475م. تتألف مدينة منبج من نواة قديمة شكلها بيضوي، تجاوزها العمران الحديث الموجه حسب المخطط التنظيمي الموضوع عام 1985 الذي أعطى المدينة شكلاً إهليلجياً.

التاريخ

القدم

منبج مدينة عريقة ازدهرت، واندثرت، ثم نهضت في العهد الحثي، ونمت في زمن الآراميين، ويرجع تاريخ تأسيسها إلى الألف الثاني قبل الميلاد، ووصل أوج تألقها في ظل معبدها القديم، ولا تزال آثاره مبعثرة في الحديقة العامة حتى اليوم، حيث كانت قبلة حج للناس آنذاك، وموطن الإلهة أتاركاتيس Atargatis ،وكانت المدينة تسمى آنذاك هيرابوليس Hierapolis أي المدينة المقدسة.

The Arameans called the city "Mnbg" (Manbug).[6] Manbij was part of the kingdom of Bit Adini and was annexed by the Assyrians in 856 BC. The Assyrian king Shalmaneser III renamed it Lita-Ashur and built a royal palace. The city was reconquered by the Assyrian king Tiglath-Pileser III in 738 BC.[7] The sanctuary of Atargatis predates the Macedonian conquest, as it seems that the city was the center of a dynasty of Aramean priest-kings ruling at the very end of the Achaemenid Empire;[8] two kings are known, 'Abyati and Abd-Hadad.[9][10] The fate of Abd-Hadad is not known but the city came firmly under the Macedonian empire,[11] and prospered under the rule of the Seleucids who made it the chief station on their main road between Antioch and Seleucia on the Tigris. The temple was sacked by Crassus on his way to meet the Parthians (53 BC). The coinage of the city begins in the 4th century BC with the coins of the priest-kings followed by the Aramaic series of the Macedonian and Seleucid monarchs. They show Atargatis either as a bust with mural crown or as riding on a lion. She continues to supply the chief type even during imperial Roman times, being generally shown seated with the tympanum in her hand. Other coins substitute the legend Θεάς Συρίας Ιεροπολιτόν Theas Syrias Ieropoliton within a wreath.[5]

In the third century, the city was the capital of Euphratensis province and one of the great cities of Roman Syria. It was, however, in a ruinous state when Julian gathered his troops there before marching to his defeat and death in Mesopotamia. Sassanid Emperor Khosrau I held it to ransom after Byzantine Emperor Justinian I had failed to defend it.[5]

اسمها الحالي مشتق من كلمة مبوغ (في اللغة الحثية) الذي أطلق عليها منذ أقدم العصور، وأصبحت فيما بعد مدينة مقدسة وعاصمة الآراميين الدينية، دخلتها المسيحية مع حلب في منتصف القرن الثالث الميلادي، وفتحت في العام 15هـ على يد أبي عبيدة عياض بن غنم. وفيما بعد أصبحت إمارة حمدانية، ولي عليها الشاعر الفارس أبو فراس الحمداني، لتصبح منبج المدينة الأكثر أهمية في الدولة الحمدانية، فقد كانت تزود الدولة الحمدانية بكل مستلزماتها من الحبوب والقطن، كما اشتهرت في ظل الدولة الحمدانية بالصناعات اليدوية، مثل صناعة السجاد والحصر والملابس.

أما اسمها الحالي فقد ظل يتواتر، ويتطور في الفترات الزمنية التي مرت بها، فقد سميت (نامبيجي) بالآشورية و(نابيجو) بالآرامية وفيما بعد (مابج) و(نابوج) بمعنى نبع، ولفظة منبج سريانية محرفة عن (منبغ) ومعناها المنبع، وسميت بهذا الاسم لوجود عين عظيمة تعرف باسم الروم.

العصور الوسطى

استعاد الخليفة العباسي هارون الرشيد منبج في نهاية القرن الثامن، جاعلاً إياها عاصمة إقليم الثغور المسمى العواصم.[12] Afterward, the city became a point of contention between the Byzantines, Arabs and Turkic groups. The Arab chieftain Salih ibn Mirdas captured it circa 1022, making Manbij, along with Balis and al-Rahba, the foundation of his Mirdasid emirate.[13] At the time, Manbij was one of the most important fortresses in northern Syria.[14] In 1068, the Byzantine emperor Romanos Diogenes captured it, defeated the Mirdasids and their Bedouin allies, killed the city's inhabitants and plundered the surrounding countryside.[15] Romanos later withdrew due to a severe shortage of food and supplies.[14][15] It was later captured by Seljuk Sultan Malik-Shah I in 1086.[16] In 1124, Belek Ghazi tried to annex Manbij, after he had imprisoned its emir Hassan al-Ba'labakki, but he was hit and killed by an arrow during the siege.[17]

The Crusaders never captured Manbij during their 11th–12th century invasions of the Levant, but the Latin Church archbishopric of Hierapolis was re-established in the town of Duluk by 1134.[18] By 1152, Duluk and Manbij were captured by the Zengids under Nur ad-Din,[18] who reconstructed and strengthened the city's fortress.[19] The Ayyubid sultan, Saladin, conquered it from its Zengid lord, Qutb ad-Din Inal, in 1175.[20] In 1260, the Mongols under Hulagu destroyed Ayyubid Manbij, which was consequently abandoned by its Turkmen inhabitants.[21]

العصر الحديث

Manbij's ruins are extensive but mostly belong to the later period of its history.[22] Most of the monuments of Manbij are gone, because it is a strategically important place at a group of crossroads, unlike Cyrrhus whose bishop was under Manbij. Henry Maundrell who visited Mambij in 1699 noticed a rock with large busts of a male and a female with two eagles below them. Another rock had three figures sculpted in low relief. Volney who visited the place in 18th century mentioned that no remains of Atargatis' temple existed. Alexander Drummond noticed walls of a square building which he said was Atargatis' temple and also a base in the building which he identified as an altar.[23]

Travellers in the 19th century had recorded some of its ancient remains, but now almost all of them, including Atargatis' temple, its sacred lake, colonnades, Roman baths, Roman theatres, walls and churches built by the Byzantine Empire as well as madrassas built in the medieval era, have been destroyed. The sacred lake of Atargatis has disappeared and has been converted into a football field. Only a part of the wall that enclosed the lake has survived but no ruins of Atargatis' temple remains. Some ancient Roman military stele also exist.[24] Ruins of the southern wall that enclosed Atargatis' temple still survive.[25] The walls of the city still exist but have been plundered.[26]

The Ottoman government resettled the area with Circassian refugees from the Russo-Turkish War in 1878.[27] As of 1911, its 1,500 inhabitants were all Circassians.[28] Armenian refugees settled in Manbij during the Armenian genocide. In autumn 1915 Djemal Pasha ordered an establishment of a camp for about 1000 families of the Armenian Clergy. In January and February 1916 the sub prefect of Manbij ordered the camp to be cleared and the Armenians to be deported to Meskene.[29] The destruction of pre-modern Manbij has been attributed to its resettlement by Circassians and Armenians.[23]

الحرب الأهلية السورية

مقالة مفصلة: الحرب الأهلية السورية

مقالة مفصلة: الحرب الأهلية السورية

في 16 يناير 2019 وقع تفجير انتحاري في منبج. الجيش الأمريكي أعلن مقتل جندي أمريكي، إلا أن أردوغان نفسه أعلن مقتل خمسة جنود أمريكان.

أفادت تقارير بوقوع قتلى ومصابين بعد انفجار وقع في مدينة منبج السورية، حيث ينتشر جنود أمريكيون في المنطقة، فيما أعلن تنظيم داعش مسؤوليته عن الهجوم.[30]

وكتب المتحدث باسم المجلس العسكري في منبج شيروان درويش على موقع تويتر: "انفجار في شارع السوق المزدحم في منبج، تقارير أولية عن سقوط ضحايا". وقال المرصد السوري لحقوق الإنسان ومقره بريطانيا إن 8 أشخاص على الأقل قتلوا.

ويأتي الهجوم بعد أقل من شهر من إعلان الرئيس دونالد ترمپ أن القوات الأمريكية ستنسحب من سوريا. وقالت المتحدثة باسم البيت الأبيض سارة ساندرز إنه تم اطلاع الرئيس الأمريكي دونالد ترمپ على الوضع.

على صعيد متصل، أعلن تنظيم داعش مسئوليته عن الهجوم الذي استهدف دورية تابعة للتحالف الذي تقوده الولايات المتحدة في منبج. وقالت وكالة أعماق التابعة للتنظيم إن الهجوم نفذه انتحاري يرتدي سترة ناسفة.

ولم يقدم تنظيم داعش أي دليل على أنه مسؤول عن الهجوم، فيما قال التحالف إنه كانت لديه دورية في منبج اليوم، موضحا عبر موقع "تويتر": "قُتل أعضاء في القوات الأمريكية في انفجار أثناء قيامهم بدورية روتينية في سوريا اليوم. ما زلنا نجمع المعلومات وسنشارك تفاصيل إضافية في وقت لاحق".

الآثار

من آثار منبج هناك قلعة منبج التي بقي منها اسمها فقط، وجثتها الهامدة وسط المدينة تشكل حيّاً يدعى (القبة)، هذه القلعة بناها السلوقيون بغرض دفاعي - أمني، وهناك سور منبج الذي ذكر في المراجع، وقد ذكرها ياقوت الحموي في معجم البلدان، فقال:

منبِج : بالفتح ثم السكون وباء موحدة مكسورة وجيم: وهو بلد قديم، وما أظنه إلا رومياً، وذكر بعضهم أن أول من بناها كسرى، لما غلب على الشام، وسماها (من به) أي أنا أجود، فعربت، فقيل منبج، وقال بطلميوس: مدينة منبج طولها إحدى وسبعون درجة وخمس عشرة دقيقة، وهي في الإقليم الرابع، قال صاحب الزيج: طولها ثلاث وثمانون درجة وعرضها خمس وثلاثون درجة، وهي مدينة واسعة ذات خيرات كثيرة وأرزاق واسعة في فضاء من الأرض، كان عليها سور من الحجارة محكم، بينها وبين الفرات ثلاثة فراسخ وبينها وبين حلب عشرة فراسخ، وشربهم من قني تسيح على الأرض، وفي دورهم آبار أكثر شربهم منها؛ لأنها عذبة صحيحة، ومنها البحتري، وخرج منها جماعة من الشعراء، وإياها عنى المتنبي بقوله:

قيلَ: بمنبجٍ مثواهُ ونائله ُ في الأفقِ يسألُ عمَّنْ غيرُهُ سألا

أهميتها عبر التاريخ

في العصور القديمة كان لها وظيفة دينية ، إذ أصبحت عاصمة الآراميين الدينية، وأقاموا فيها هيكل إله العواصف حدد وإلهة المياه أتاركاتيس، وقد كان تمثال أتاركاتيس يمثلها راكبة على مركبة تجرها الأسود، وفي يدها آلة موسيقية وعلى رأسها تاج.

لكن وظيفتها الأساسية على الغالب كانت وظيفة حربية، فكانت من أهم قواعد الجيش الروماني التي يمر بها للإغارة على بلاد مابين النهرين وفارس، وقد أشاد فيها يوستنيانوس Justinianus أسواراً منيعة، كما تدل الأسوار البيزنطية على ماضي المدينة موقعاً محصناً تعاورته أيدي الفرس والبيزنطيين والعرب، وفي العصر الأموي كانت تابعة لجند قنسرين وحلب، وتابعت وظيفتها الحربية ثغراً من ثغور الإسلام ضد الروم.

وظائف زراعية وصناعية في الأراضي المحيطة بها،حيث كانت سابقاً معروفة بزراعة أشجار التوت وتربية دودة القز، ومن ثم صناعة الحرير الطبيعي، وقد كانت نهاية تلك الصناعة عام 1241م ، وقد تحولت في القرن التاسع عشر- بعد تدميرها- إلى مراعٍ، وفي العهد الحديث توسعت الزراعات المروية فيها بعد تنظيف القنوات القديمة وبفضل المزارعين الجدد القادمين من الباب. وهي تتميز بشبكة من الجداول والأقنية الجوفية أكثر من أي منطقة أخرى في سورية. وبعد أن كانت مركزاً لإنتاج القنب تحولت إلى مركز لإنتاج القطن منذ الحرب العالمية الثانية، ولكن التوسع في هذه الزراعة أدى إلى استنزاف رصيد الأرض من المياه الجوفية، مما أدى إلى جفاف بساتينها حتى أصبحت تعتمد على مياه نهر الفرات.

الوظيفة التجارية: انتعشت التجارة فيها بحكم موقعها الوسيط بين الجزيرة والفرات شرقاً وحلب و اللاذقية غرباً. كما كانت مركز تبادل تجاري بين مدينة حلب من جهة والبادية ووادي الفرات وسهول حلب الشرقية وعين العرب من جهة أخرى. ويستدل على فعاليتها التجارية من «بازار» المواشي الذي كان يستمر ثلاثة أيام متوالية؛ إذ كان يخصص يوم الأحد لسوق الخيل والبغال، ويوم الإثنين للغنم والماعز؛ ويوم الثلاثاء للأبقار والإبل ، وهي ظاهرة لا مثيل لها في المدن السورية.

الجغرافيا

المناخ

Manbij has a cold semi-arid climate (Köppen climate classification BSk) with influences of a continental climate during winter with hot dry summers and cool wet and occasionally snowy winters. The average high temperature in January is 7.8 °C (46.0 °F) and the average high temperature in August is 38.1 °C (100.6 °F) . The snow falls usually in January, February or December.

| بيانات المناخ لـ منبج | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| الشهر | ينا | فب | مار | أبر | ماي | يون | يول | أغس | سبت | أكت | نوف | ديس | السنة |

| متوسط القصوى اليومية °س (°ف) | 7.9 (46.2) |

10.5 (50.9) |

15.6 (60.1) |

23.4 (74.1) |

28.3 (82.9) |

34.3 (93.7) |

37.7 (99.9) |

38.1 (100.6) |

33.2 (91.8) |

26.3 (79.3) |

15.3 (59.5) |

9.1 (48.4) |

23.3 (73.9) |

| متوسط الدنيا اليومية °س (°ف) | −1.2 (29.8) |

−0.6 (30.9) |

4.3 (39.7) |

7.2 (45.0) |

12.5 (54.5) |

15.1 (59.2) |

19.9 (67.8) |

20.9 (69.6) |

16.3 (61.3) |

12.4 (54.3) |

6.4 (43.5) |

−0.5 (31.1) |

9.4 (48.9) |

| متوسط تساقط الأمطار mm (inches) | 69 (2.7) |

54 (2.1) |

38 (1.5) |

28 (1.1) |

8 (0.3) |

3 (0.1) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

3 (0.1) |

25 (1.0) |

36 (1.4) |

58 (2.3) |

322 (12.6) |

| Average rainy days | 10 | 6 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 9 | 46 |

| متوسط الرطوبة النسبية (%) | 71 | 63 | 56 | 52 | 38 | 36 | 31 | 31 | 39 | 43 | 51 | 70 | 48 |

| Source: Weather Online, Weather Base, BBC Weather and My Weather 2, retrieved 10 November 2012 | |||||||||||||

السكان

قدر عدد سكانها بنحو 3800 نسمة في عام 1931، وقدر عدد سكانها بنحو 99,000 نسمة في عام 2004.

النقل

Manbij is served by two major roads, Route M4 and Route 216.

There is no airport near Manbij, the nearest is in Aleppo.

مشاهير منبج

أكثر من اشتهر من منبج في العصر البيزنطي كانت الإمبراطورة ثيودورا. وفي العصر الإسلامي، الشعراء، ومنهم: البحتري الشاعر العباسي المعروف، وأبو فراس الحمداني، ودوقلة المنبجي واسمه يحيى بن نزار بن سعيد المنبجي أبو الفضل ولد ها سنة 486هـ وانتقل إلى دمشق فاتصل بالملك العادل نور الدين محمود بن زنكي، ومدحه بقصائد أجاد فيها، ثم رحل إلى بغداد، فاستوطنها (توفي بها سنة 554هـ) وعمر أبو ريشة، وهو من الشعراء المشهورين في العصر الحديث.

المراجع

- كتاب (آلهة سوريا) للكاتب الفيلسوف الكبير لوسيانوس السمسياطيي، وهو كتاب باللغة اليونانية القديمة، وقد ترجم إلى عدة لغات ، وترجمه إلى العربية موسى ديب الخوري وصدر عن دار الأبجدية بدمشق عام 1992.[31]

- ياقوت الحموي، معجم البلدان، الجزء الخامس، (دار صادر، بيروت).

- عادل عبد السلام، عبد الكريم حليمة، محمد إسماعيل الشيخ، جغرافية سورية الإقليمية (منشورات جامعة تشرين 2003).

- عبد الرحمن حميدة، محافظة حلب (وزارة الثقافة، دمشق 1992).

- كتاب (منبج سيرة ومسيرة) للأستاذ حسين علي البكار.

- كتاب (كتاب منبج) للاستاذ محمد احمد الغويش.

المصادر

- The Syrian Goddess (1913) at sacred-texts.com

- F. R. Chesney, Euphrates Expedition (1850)

- W. F. Ainsworth, Personal Narrative of the Euphrates Expedition (1888)

- E. Sachau, Reise in Syrien, &c. (1883)

- D. G. Hogarth in Journal of Hellenic Studies (1909)

- Henry Maundrell ( 1836): A Journey from Aleppo to Jerusalem: At Easter, A.D. 1697 : to which is Added an Account of the Author's Journey to the Banks of the Euphrates at Beer, and to the Country of Mesopotamia 271 pages

تحوي هذه المقالة معلومات مترجمة من الطبعة الحادية عشرة لدائرة المعارف البريطانية لسنة 1911 وهي الآن من ضمن الملكية العامة.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةCBS - ^ فواز الموسى. "منبج". الموسوعة العربية.

- ^ Trevor Bryce (2009). The Routledge Handbook of the Peoples and Places of Ancient Western Asia: The Near East from the Early Bronze Age to the Fall of the Persian Empire. p. 498. ISBN 9781134159086.

- ^ Irene Winter (2009). On Art in the Ancient Near East Volume I: Of the First Millennium BCE. p. 564. ISBN 9789047425847.

- ^ أ ب ت One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . دائرة المعارف البريطانية. Vol. 13 (eleventh ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 451–452.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Greenfield, Jonas Carl (2001). "Aspects of Aramean Religion". In Paul, Shalom M.; Stone, Michael E.; Pinnick, Avital (eds.). 'Al Kanfei Yonah: Collected Studies of Jonas C. Greenfield on Semitic Philology. Biblical Studies and Religious Studies. Vol. 1. Brill. p. 285. ISBN 978-9-004-12170-6.

- ^ Trevor Bryce (2009). The Routledge Handbook of the Peoples and Places of Ancient Western Asia: The Near East from the Early Bronze Age to the Fall of the Persian Empire. p. 479. ISBN 9781134159086.

- ^ Fergus Millar (1993). The Roman Near East, 31 B.C.-A.D. 337. p. 244. ISBN 9780674778863.

- ^ Edward Lipiński (2000). The Aramaeans: Their Ancient History, Culture, Religion. p. 633. ISBN 9789042908598.

- ^ Kevin Butcher (2004). Coinage in Roman Syria: Northern Syria, 64 BC-AD 253. p. 24. ISBN 9780901405586.

- ^ John D Grainger (2014). Seleukos Nikator (Routledge Revivals): Constructing a Hellenistic Kingdom. p. 147. ISBN 9781317800996.

- ^ Cobb, Paul M. (2001). White Banners: Contention in 'Abbasid Syria, 750-880. SUNY Press. p. 12. ISBN 9780791448809.

- ^ Zakkar, Suhayl (1971). The Emirate of Aleppo: 1004–1094. Aleppo: Dar al-Amanah. p. 53.

- ^ أ ب Basan, Osman Aziz (2010). The Great Seljuqs: A History. Routledge. p. 76. ISBN 9781136953934.

- ^ أ ب Ibn al-Athir (2002). Richards, D.S. (ed.). The Annals of the Saljuq Turks: Selections from Al-Kamil Fi'l-Ta'rikh of Ibn Al-Athir. Routledge. p. 166. ISBN 9781317832553.

- ^ Purton 2009, p. 184.

- ^ Richards 2010, p. 619.

- ^ أ ب Hamilton, Bernard (2006). "The Growth of the Latin Church of Antioch". In Ciggaar, K.; Metcalf, M. (eds.). East and West in the Medieval Eastern Mediterranean: Antioch from the Byzantine Reconquest Until the End of the Crusader Principality. Peeters Publishers. pp. 175, 180. ISBN 9789042917354.

- ^ Hillenbrand, Carole (2000). The Crusades: Islamic Perspectives. Routledge. p. 474. ISBN 9780415929141.

- ^ Lyons, Malcolm Cameron; Jackson, D. E. P. (1982). Saladin: The Politics of the Holy War. Cambridge University Press. p. 105. ISBN 9780521317399.

- ^ Amitai-Preiss, Reuven (1995). Mongols and Mamluks: The Mamluk-Ilkhanid War, 1260-128. Cambridge University Press. p. 204. ISBN 9780521522908.

- ^ "Hierapolis", in - The new Encyclopædia Britannica: Volume 5, 2002, page 913

- ^ أ ب Greenhalgh, Michael (3 November 2016). Syria's Monuments: Their Survival and Destruction. pp. 243, 244. ISBN 9789004334601.

- ^ Burns, Ross (30 June 2009). Monuments of Syria: A Guide. pp. 202, 203. ISBN 9780857714893.

- ^ Ross Burns. "Aleppo: A History", p. 36

- ^ A. Asa Eger. "The Islamic-Byzantine Frontier: Interaction and Exchange Among Muslim and Christian Communities", p. 36

- ^ Sir Ernest Alfred Wallis Budge, By Nile and Tigris: A Narrative of Journeys in Egypt and Mesopotamia on Behalf of the British Museum Between the Years 1886-1913, Volume 1, p. 390, [1]

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةce - ^ Kevorkian, Raymond. "Le réseaux des camps de concentration. Axes de déportation et camps de concentration de Syrie et de Mésopotamie". www.imprescriptible.fr. Retrieved 2020-12-07.

- ^ "تفجير منبج: قتلى بصفوف القوات الأمريكية.. وداعش يتبنى الهجوم". سي إن إن. 2019-01-16. Retrieved 2019-01-16.

- ^ The Syrian Goddess Index Archived 2017-08-23 at the Wayback Machine

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Pages using gadget WikiMiniAtlas

- Pages using infobox settlement with unknown parameters

- Articles containing Ancient Greek (to 1453)-language text

- Articles containing لاتينية-language text

- Pages using Lang-xx templates

- مقالات مأخوذة من الطبعة الحادية عشرة لدائرة المعارف البريطانية

- مواقع أثرية في سوريا

- مدن محافظة حلب

- مدن سوريا

- مقالات المعرفة المحتوية على معلومات من دائرة المعارف البريطانية طبعة 1911

- Wikipedia articles incorporating text from the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica