مملكة راتاناكوسين

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

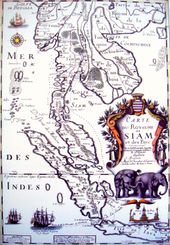

مملكة راتاناكوسين (بالتايلندية: อาณาจักรรัตนโกสินทร์؛ IPA: [āːnāːt͡ɕàk ráttanákōːsǐn]؛ إنگليزية: Rattanakosin Kingdom) هي رابع وآخر مركز تقليدي للسلطة في تاريخ تايلند (أو سيام). وقد تأسست في 1782 بتأسيس بانكوك كعاصمة.

The maximum zone of influence of the Rattanakosin Kingdom included the vassal states of Cambodia, Laos, Burmese Shan States, and some Malay kingdoms. The kingdom was founded by King Rama I (Phra Phutthayotfa Chulalok) of the Chakri Dynasty. The first half of this period was characterised by the consolidation of the kingdom's power and was punctuated by periodic conflicts with Burma, Vietnam and Laos. The second period was one of engagements with the colonial powers of Britain and France in which Siam managed to remain the only Southeast Asian nation to maintain its independence.[5]

Internally the kingdom developed into a modern centralised nation state with borders defined by its interactions with Western powers. Significant economic and social progress was made, marked by an increase in foreign trade, the abolition of slavery and the expansion of formal education to the emerging middle class. However, the failure to implement substantial political reforms culminated in the 1932 revolution and the abandonment of absolute monarchy in favour of a constitutional monarchy. This article covers events up until 1932; for subsequent history, see History of Thailand (1932–73).

خلفية

في 1767، after dominating southeast Asia for almost 400 years, the Ayutthaya Kingdom was brought down by invading Burmese armies.[6]

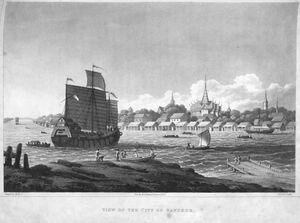

منظر بانكوك في القرن 19، ويظهر فيه الجبل الذهبي في الخلفية. |

المصلح

سيام المعاصرة (1905–1932)

من مملكة إلى أمة عصرية

الحرب العالمية الأولى

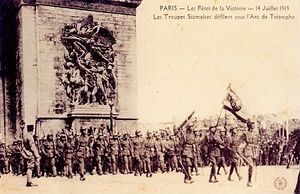

قوة التجريدة السيامية أثناء الحرب العالمية الأولى في پاريس، 1919. |

In 1917 Siam declared war on Germany and Austria-Hungary, mainly to be favor with the British and the French. Siam's taken participation in World War I secured it a seat at the Versailles Peace Conference, and Foreign Minister Devawongse used this opportunity to argue for the repeal of 19th century treaties and the restoration of full Siamese sovereignty. The United States obliged in 1920, while France and Britain delayed until 1925. This victory gained the king some popularity, but it was soon undercut by discontent over other issues, such as his extravagance, which became more noticeable when a sharp postwar recession hit Siam in 1919. There was also concern that the king had no son, which undermined the stability of the monarchy due to the absence of heirs[بحاجة لمصدر]. Thus when Rama VI died suddenly in 1925, aged only 44, the monarchy was in a weakened state. He was succeeded by his younger brother Prajadhipok.

الانتقال إلى ثورة 1932

نهاية الحكم المطلق (1925-1932)

الثورة

In 1932, with the country deep in depression, the Supreme Council opted to introduce cuts in spending, including the military budget. The king foresaw that these policies might create discontent, especially in the army, and he therefore convened a special meeting of officials to explain why the cuts were necessary. In his address he stated the following, "I myself know nothing at all about finances, and all I can do is listen to the opinions of others and choose the best... If I have made a mistake, I really deserve to be excused by the people of Siam."

No previous monarch of Siam had ever spoken in such terms. Many interpreted the speech not as Prajadhipok apparently intended, namely as a frank appeal for understanding and cooperation. They saw it as a sign of his weakness and evidence that a system which perpetuated the rule of fallible autocrats should be abolished. Serious political disturbances were threatened in the capital, and in April the king agreed to introduce a constitution under which he would share power with a prime minister. This was not enough for the radical elements in the army, however. On 24 June 1932, while the king was at the seaside, the Bangkok garrison mutinied and seized power, led by a group of 49 officers known as "Khana Ratsadon". Thus ended 800 years of absolute monarchy.

Thai political history was little researched by Western Southeast Asian scholars in the 1950s and 1960s. Thailand, as the only nominally "native" Southeast Asian polity to escape colonial conquest, was deemed to be relatively more stable as compared with other newly independent states in Southeast Asia.[7] It was perceived to have retained enough continuity from its "traditions", such as the institution of the monarchy, to have escaped from the chaos and troubles caused by decolonisation and to resist the encroachment of revolutionary communism.[7] By implication, this line of argument suggests the 1932 revolution was nothing more than a coup that simply replaced the absolute monarchy and its aristocracy with a commoner elite class made up of Western-educated generals and civilian bureaucrats and essentially that there was little that was revolutionary about this event. David K. Wyatt, for instance, described the period of Thai history from 1910 to 1941 as "essentially the political working out of the social consequences of the reforms of Chulalongkorn's reign".[8] The 1932 revolution was generally characterised as the inevitable outcome of "natural consequences of forces set in motion by Rama IV and Rama V".[9]

الحكم والبيروقراطية

فترة راتاناكوسين المبكرة (1782–1855)

الحكم المركزي

السكان

الدين

الإسلام

After the fall of the Ayutthaya Kingdom and failed attempts to reacquire the portage route long by the Chakri rulers, Persian and Muslim influence in Siam declined as Chinese influence within the kingdom grew. Despite this however, the Muslim community remained a sizable minority in Bangkok, particularly in the first hundred years or so.

After the Fall of Ayutthaya, Shiite Muslims of Persian descent from Ayutthaya settled in the Kudi Chin district. ‘Kudi’ (กุฎี) was the Siamese term for Shiite Imambarah, though it could also refer to a mosque. Muslim communities in Siam were led by Phraya Chula Ratchamontri (พระยาจุฬาราชมนตรี), the position that had been held by a single lineage of Shiite Persian descendant of Sheikh Ahmad since 1656 and until 1939.[10] Phraya Chula Ratchamontri was also the Lord of the Right Pier who headed the Kromma Tha Khwa (กรมท่าขวา) or the Department of the Right Pier that dealt with trade and affairs with Muslim Indians and Middle Easterners. Shiite Persians were elite Muslims who served as officials in Kromma Tha Khwa. Shiites in Siam were characterized by their ritual of the Mourning of Muharram or Chao Sen ceremony (Imam Hussein was called Chao Sen[10] เจ้าเซ็น in Siamese). King Rama II ordered the Muharram rituals to be performed before him in the royal palace in 1815 and 1816. Kudi Mosques were established and concentrated on the West bank of Chao Phraya River in Thonburi. Important Kudis in Thonburi included Tonson Mosque (Kudi Yai or the Great Kudi, oldest mosque in Bangkok), Kudi Charoenphat (Kudi Lang, the Lower Kudi) and Bangluang Mosque (Kudi Khao or the White Kudi).

The Siamese used the term Khaek[10] (แขก) for the Islamic peoples in general. In traditional Siam, religion was closely tied with ethnicity. Muslims in Siam included the Sunni Khaek Cham and Khaek Malayu (Malays) and Shiite Khaek Ma-ngon or Khaek Chao Sen, referring to Persians.

الثقافة

التعليم

There was no official institutions for education such as universities in pre-modern Siam. Siamese traditional education was closely tied to the Buddhist religion. Boys went to temples or became novice monks to learn Thai and Pāli languages from monks, who offered tutorships for free as a part of religious works. Princes and young nobles received tuition from high-ranking monks in fine temples. Girls were not expected to be literate and were usually taught domestic arts such as culinary and embroidery. However, education for women was not restricted and upper-class women had more opportunities for literacy. There were some prominent female authors in the early Rattanakosin period. Craftsmanships and artisanships were taught internally in the same family or community.

The only higher education available in pre-modern Siam was the Buddhist Pāli doctrinal learning – the Pariyattham (ปริยัติธรรม). Monks took exams to be qualified to rise up in the ecclesiastic bureaucracy. There were three levels of Pariyattham exams inherited from Ayutthaya with each level called Parian (เปรียญ). In the 1810s, the three Parian levels were re-organized into nine Parian levels. Pariyattham exams were organized by the royal court, who encouraged Pāli learning in order to uphold Buddhism, and were usually held in the Emerald Buddha temple. Examinations involved translation and oral recitation of Pāli doctrines in front of examiner monks. Pariyattham exam was the vehicle both for intellectual pursuits and for advancement in monastic hierarchy for a monk.

King Rama III ordered traditional Thai religious and secular arts, including Buddhist doctrines, traditional medicine, literature and geopolitics to be inscribed on stone steles at Wat Pho from 1831 to 1841. The Epigraphic Archives of Wat Pho was recognized by UNESCO as a Memory of the World and were examples of materials with closer resemblance to modern education. The Epigraphical Archives of Wat Pho (external link)

الإصلاح التعليمي

Rama VI was the first king of Siam to set up a model of the constitution at Dusit Palace. He wanted first to see how things could be managed under this Western system. He saw advantages in the system, and thought that Siam could move slowly towards it, but could not be adopted right away as the majority of the Siamese people did not have enough education to understand such a change just yet. In 1916 higher education came to Siam. Rama VI set up Vajiravudh College, modeled after the British Eton College, as well as the first Thai university, Chulalongkorn University,[11] modeled after Oxbridge.

Vajiramonkut Building, Vajiravudh College.

Maha Chulalongkorn Building, Chulalongkorn University.

الفن والأدب

Rama II was a lover of the arts and in particular the literary arts. He was an accomplished poet and anyone with the ability to write a refined piece of poetry would gain the favor of the king. This led to his being dubbed the "poet king". Due to his patronage, the poet Sunthon Phu was able to raise his noble title from "phrai" to "khun" and later "phra". Sunthon – also known as the drunken writer – wrote numerous works, including the epic poem Phra Aphai Mani.[بحاجة لمصدر]

Rama II rewrote much of the great literature from the reign of Rama I in a modern style. He is credited with writing a popular version of the Thai folk tale Ramakien and wrote a number of dance dramas such as Sang Thong. The king was an accomplished musician, playing and composing for the fiddle and introducing new instrumental techniques. He was also a sculptor and is said to have sculpted the face of the Niramitr Buddha in Wat Arun. Because of his artistic achievements, Rama II's birthday is now celebrated as National Artists' Day (Wan Sinlapin Haeng Chat), held in honor of artists who have contributed to the cultural heritage of the kingdom[بحاجة لمصدر]

الملابس

As same as Ayutthaya period, both Thai males and females dressed themselves with a loincloth wrap called chong kraben. Men wore their chong kraben to cover the waist to halfway down the thigh, while women covered the waist to well below the knee.[12] Bare chests and bare feet were accepted as part of the Thai formal dress code, and is observed in murals, illustrated manuscripts, and early photographs up to the middle of the 1800s.[12] However, after the Second Fall of Ayutthaya, central Thai women began cutting their hair in a crew-cut short style, which remained the national hairstyle until the 1900s.[13] Prior to the 20th century, the primary markers that distinguished class in Thai clothing were the use of cotton and silk cloths with printed or woven motifs, but both commoners and royals alike wore wrapped, not stitched clothing.[14]

From the 1860s onward, Thai royals "selectively adopted Victorian corporeal and sartorial etiquette to fashion modern personas that were publicized domestically and internationally by means of mechanically reproduced images."[14] Stitched clothing, including court attire and ceremonial uniforms, were invented during the reign of King Chulalongkorn.[14] Western forms of dress became popular among urbanites in Bangkok during this time period.[14]

During the early 1900s, King Vajiravudh launched a campaign to encourage Thai women to wear long hair instead of traditional short hair, and to wear pha sinh (ผ้าซิ่น), a tubular skirt, instead of the chong kraben (โจงกระเบน), a cloth wrap.[15]

انظر أيضاً

ملاحظات

- ^ This historical period is more colloquially referred to as the Rattanakosin period in Thailand.

- ^ أ ب Beginning with the Bowring Treaty of 1855, the country was referred to as the "Kingdom of Siam" in diplomatic treaties.[مطلوب توضيح][1]

- ^ Full title – Phra Phutthayotfa Chulalok Maharaj

المراجع

- ^ ""สยาม" ถูกใช้เรียกชื่อประเทศเป็นทางการสมัยรัชกาลที่ 4" (in التايلاندية). ศิลปวัฒนธรรม. 6 July 2017. Retrieved 10 August 2017.

- ^ Lieberman, Victor (2003). Strange Parallels: Volume 1, Integration on the Mainland: Southeast Asia in Global Context, c.800–1830 (Studies in Comparative World History) (Kindle ed.). ISBN 978-0521800860.

- ^ Lieberman, Victor (2003). Strange Parallels: Volume 1, Integration on the Mainland: Southeast Asia in Global Context, c.800–1830 (Studies in Comparative World History) (Kindle ed.). p. 295. ISBN 978-0521800860. "Siam's population must have increased from c. 2,500,000 in 1600 to 4,000,000 in 1800."

- ^ "Number of population in Thailand : 1911 - 1990 census years". web.nso.go.th. National Statistical Office. 2004. Retrieved 14 January 2022.

- ^ "Rattanakosin Period (1782 -present)". GlobalSecurity.org. Retrieved November 1, 2015.

- ^ "Historic City of Ayutthaya". © UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved November 21, 2015.

- ^ أ ب Van Praagh, David (1996). Thailand's Struggle for Democracy: The Life and Times of M. R. Seni Pramoj. New York: Holmes & Meier.

- ^ Steinberg, D. J., ed. (1971). In Search of Southeast Asia. Kuala Lumpur: Oxford University Press.

- ^ Batson, Benjamin A. (1984). The End of Absolute Monarchy in Siam. Singapore: Oxford University Press.

- ^ أ ب ت Chularatana, Julispong. The Shi'ite Muslims in Thailand from Ayutthaya Period to the Present.

- ^ Bing Soravij BhiromBhakdi. "Rama VI of the Chakri Dynasty". The Siamese Collection. Archived from the original on 27 أكتوبر 2016. Retrieved 18 أبريل 2017.

- ^ أ ب Terwiel, Barend Jan (2007). "The Body and Sexuality in Siam: A First Exploration in Early Sources" (PDF). Manusya: Journal of Humanities. 10 (14): 42–55. doi:10.1163/26659077-01004003. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 نوفمبر 2016. Retrieved 18 مايو 2018.

- ^ Jotisalikorn, Chami (2013). Thailand's Luxury Spas: Pampering Yourself in Paradise (in الإنجليزية). Tuttle Publishing. p. 183.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Peleggi, Maurizio (2010). Mina Roces (ed.). The Politics of Dress in Asia and the Americas. Sussex Academic Press. ISBN 9781845193997.

- ^ Sarutta (10 سبتمبر 2002). "Women's Status in Thai Society". Thaiways Magazine. Archived from the original on 31 أكتوبر 2016. Retrieved 7 نوفمبر 2016.

ببليوگرافيا

- Greene, Stephen Lyon Wakeman. Absolute Dreams. Thai Government Under Rama VI, 1910–1925. Bangkok: White Lotus, 1999

- Wyatt, David, Thailand: A Short History, Yale University Press, 1984

قالب:Thonburi قالب:History of Thailand 1932 - 1973 قالب:Rattanakosin

- جميع الصفحات التي تحتاج تنظيف

- مقالات بالمعرفة تحتاج توضيح from February 2022

- CS1 التايلاندية-language sources (th)

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- مقالات بالمعرفة تحتاج توضيح from January 2022

- Articles containing تايلندية-language text

- مقالات بالمعرفة تحتاج توضيح from December 2021

- Articles with unsourced statements from February 2022

- Pages using infobox country with unknown parameters

- Pages using infobox country or infobox former country with the flag caption or type parameters

- Pages using infobox country or infobox former country with the symbol caption or type parameters

- Portal-inline template with redlinked portals

- Pages with empty portal template

- Articles containing إنگليزية-language text

- Pages using Lang-xx templates

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Articles with unsourced statements from November 2019

- Articles with unsourced statements from October 2021

- Unclassified articles missing geocoordinate data

- All articles needing coordinates

- مملكة راتاناكوسين

- أسرة تشاكري

- تاريخ تايلند

- تاريخ كمبوديا

- تاريخ لاوس

- تاريخ ماليزيا

- عقد 1780 في سيام

- عقد 1790 في سيام

- القرن 18 في سيام

- القرن 19 في سيام

- القرن العشرون في تايلند

- دول وأقاليم تأسست في 1782

- تأسيسات 1782 في سيام

![نطاق نفوذ مملكة راتاناكوسين في النصف الأول من القرن 19 (including its principal territories)[مطلوب توضيح]](/w/images/thumb/d/d2/Map_of_the_Rattanakosin_Kingdom.svg/350px-Map_of_the_Rattanakosin_Kingdom.svg.png)

![الحدود السياسية لمملكة سيام قبل Anglo-Siamese Treaty of 1909[ب]](/w/images/thumb/6/6c/Siam_1900_V2.png/350px-Siam_1900_V2.png)