متحف البرازيل الوطني

متحف البرازيل الوطني | |

| |

| تأسس | 1818 |

|---|---|

| الموقع | كوينتا دا بوا ڤيستا في ريو دي جانيرو، البرازيل |

| الإحداثيات | 22°54′20.40″S 43°13′33.98″W / 22.9056667°S 43.2261056°W |

| النوع | التاريخ الطبيعي، علم الأعراق وعلم الآثار |

| حجم المجموعات | نحو 20 مليون غرض (قبل حريق 2018) [1] |

| الزوار | approx. 150,000 (2017)[2] |

| المدير | ألكسندر كلنر |

| الموقع الإلكتروني | www.museunacional.ufrj.br |

المتحف الوطني (برتغالية: Museu Nacional) هو أقدم مؤسسة علمية في البرازيل وواحداً من أكبر متاحف التاريخ الطبيعي وعلم الأعراق في الأمريكتين. يقع المتحف داخل منتزه كوينتا دا بوا ڤيستا، بمدينة ريو دي جانيرو، وكان مقاماً في پاسو دى ساو كريستوڤاو (قصر القديس كريستوفر). كان يخدم القصر كمقر للعائلة الملكية الپرتغالية بين عام 1808 و1821، واستضاف العائلة الامبراطورية البرازيلية ما بين 1822 و1889، كما استضاف المجلس الدستوري الجمهوري من 1889 حتى 1891، قبل أن يخصص ليستخدم متحفاً عام 1892. أُدرج المبنى على قائمة التراث الوطني البرازيلي منذ عام 1938.[3]

بأمر من الملك جواو السادس من الپرتغال، تأسس المتحف في 6 يونيو 1818، باسم "المتحف الملكي"، في البداية أُستضيف المتحف في منتزه كامپو دى سانتانا، حيث كان يعرض مجموعة تم الحصول عليها من بيت التاريخ الطبيعي السابق، وشهرته Casa dos Pássaros ("بيت الطيور")، والذي تأسس في 1784 بواسطة نائب ملك البرازيل لويس دى ڤاسكونسيلوس إي سوسا، بالإضافة لمجموعات علم المعادن وعلم الحيوان. كان الهدف من تأسيسه تلبية اهتمامات تعزيز التنمية الاقتصادية الاجتماعية للبلاد بنشر التعليم، الثقافة والعلوم. في القرن 19، كان المتحف قد أصبح بالفعل واحداً من أهم المتاحف في أمريكا الجنوبية. دُمج ضمن جامعة ريو دي جانيرو الفدرالية في 1946.[4][3][5]

كان المتحف الوطني يحتفظ بمجموعة ضخمة تضم أكثر من 20 مليون قطعة، مؤلفة واحدة من أهم سجلات العينات المتعلقة بالعلوم الطبيعية وعلم الأعراق في البرازيل، فضلاً عن عدد ضخم من المعروضات مختلفة المنشأ من النباتات والمنتجة من ثقافات مختلفة وحضارات قديمة. تشكلت المجموعة على مدى أكثر من قرنين من خلال الحملات وعمليات التنقيب والاستحواذات والتبرعات والتبادلات، وتم تقسيمها إلى سبع مجموعة أساسية: الجيولوجيا، علم الإحاثة، علم النبات، علم الحيوان، علم الإنسان الحيوي]]، علم الآثار، وعلم الأعراق. كانت المجموعة قاعدة أساسية للأبحاث التي عقدتها الادارة الأكاديمية في المتحف- والتي كانت مسئولة عن تنفيذ الأنشطة في جميع المناطق على الأراضي البرازيلية وأماكن مختلفة في العالم، من بينها قارة أنتاركتيكا. كما يضم المتحف واحدة من أكبر المكتبات العلمية في البرازيل، بأكثر من 470.000 جزء و2.400 عمل نادر.[3]

في مجال التعليم، يوفر المتحف تخصصات، وبرامج لما بعد التخرج في مختلف المجالات المعرفية، بالإضافة لاستضافة معارض مؤقتة ودائمة وأنشطة تعليمية مفتوحة للعامة.[3] يدير المتحف Horto Botânico (الحديقة النباتية)، بجوار پاكو دى ساو كريستوڤاو، بالإضافة لحرم جامعي متقدم في مدينة سانتا تريزا، في إسپيريتو سانتو - محطة سانت لوشيا النباتية، ويشترك مع المتحف في الادارة أستاذ علم النبات مـِلو ليتاو. الموقع الثالث، يقع في مدينة ساكوارمو، يستخدم كمركز للدعم واللوجستيات للأنشطة التخصصية. وأخيراً، يستضيف المتحف أرشيف المتحف الوطني، أقدم دورية علمية في البرازيل[بحاجة لمصدر] والتي تُنشر بشكل متواصل منذ عام 1876.[4][6]

في 2 سبتمبر 2018، تعرض القصر الذي يستضيف المتحف للدمار بسبب حريق شب أثناء الليل.[7][8][9]

التاريخ

تأسس المتحف الوطني بأمر من ملك الپرتغال الدوم جواو السادس (1769-1826) عام 1818 باسم المتحف الملكي، في مبادرة لتشجيع البحث العلمي على أراضي البرازيل. ضم المتحف في البداية عينات نباتية وحيوانية، وخاصة الطيور، ولذلك كان سكان ريو دى جانيرو، التي كان المبنى يقع في وسطها، يطلقون عليه "بيت الطيور".

الصعوبات المالية وحريق 2018

منذ عام 2014، واجه المتحف تخفيضا في الميزانية والتي خفضت الميزانية المخصصة للصيانة بالمتحف إلى أقل من 520.000 ريال برازيلي سنوياً. أصبح المبنى في حالة سيئة، وظهر ذلك من خلال تقشر مادة الجدار والأسلاك الكهربائية المكشوفة.[10] بحلول يونيو 2018، في الذكرى السنوية رقم 200 للمتحف، وصل إلى حالة إهمال شبه كاملة.[11]

تضرر المبنى بشكل كبير من حريق ضخم نشب في 2 سبتمبر 2018.[7][9] على الرغم من إنقاذ بعض المعروضات، إلا أنه يعتقد بأن جزءاً كبيراً من الـ20 مليون قطعة مؤرشفة قد دُمّر في الحريق، بينما تم تخزين قطع أخرى في مبنى منفصل لم يلحق به أي أضرار.[8] وكان أول المستجيبين لمكافحة الحريق يعوقهم نقص المياه. ادعى رئيس الإطفاء في ريو أن اثنين من حنفيات الحريق القريبة كانت مياههما غير كافية، مما دفع برجال الإطفاء للجوء إلى ضخ المياه من بحيرة مجاورة.[12]

المجموعات

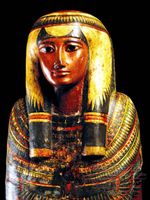

يضم المعرض واحدة من أكبر المجموعات في الأمريكتين، تتألف من حيوانات، حشرات، معادن، مجموعات أواني للشعوب الأصلية، مومياوات مصرية وقطع أثرية أمريكية جنوبية، أحجار نيزكية، أحفورات واكتشافات أثرية أخرى.

أحد النيازك المعروضة كان نيزك بندگو، وكان يزن أكثر من 5.000 كگ وتم اكتشافه عام 1784.[13]

الآثار

مصر القديمة

بأكثر من 700 قطعة، كانت المجموعة الأثرية المصرية في المتحف الوطني واحدة من أكبر المجموعات في أمريكا اللاتينية والأقدم في الأمريكتين. دخلت معظم مقتنيات المجموعة المتحف عام 1826، عندما قام التاجر نيكولاو فينگو بشراء مجموعة أنتيكات المصرية في مارسيليا كانت تخص المستكشف الإيطالي الشهير جوڤاني باتيستا بلزوني، الذي كان مسئولاً عن التنقيب عن الآثار في مقابر طيبة (الأقصر حالياً) ومعبد الكرنك.[14]

المجموعة كان مقصدها الأصلي هو الأرجنتين، ولعل من طلبها كان رئيس ذلك البلد برناردينو ريڤاداڤيا، مؤسس جامعة بوينس آيرس والذي اشتهر بحبه للمتاحف. إلا أن حصاراً بحرياً في نهر لا پلاتا حال دون أن يُكمل فينگو رحلته، مجبراً إياه على العودة من مونتڤيديو إلى ريو دي جانيرو، حيث عرض القطع للبيع في مزاد. اشترى الامبراطور پدرو الأول المجموعة بأكملها بخمسة ملايين ريال، وتبرع بها لاحقاً للمتحف الوطني. وقد اقترح البعض أن تصرف پدرو الأول كان بتأثير من جوسيه بونيفاسيو دي أندرادا، العضو المبكر الهام في الماسونية في البرازيل، ربما بدافع من اهتمام تلك الجماعة بالأيقونات المصرية.[15][16] [17]

The collection started by Pedro I would be expanded by his son, emperor Pedro II, amateur Egyptologist and notable collector of archaeological and ethnographic artifacts. One of the most important additions to the Egyptian collection of the National Museum made by Pedro II is the polychromed wood sarcophagus of the singer of Amun, Sha-Amun-en-su, from the Late Period, offered to the emperor as a gift during his second trip to Egypt, in 1876, by the الخديوي إسماعيل. The sarcophagus is distinguished for its rarity, since it is one of few examples that have never been opened, still preserving the mummy of the singer in its interior.[14] The collection would be enriched through other acquisitions and donations, becoming, at the beginning of the 20th-century, sufficiently relevant to draw the attention of international researchers and egyptologysts, such as Alberto Childe, who served as conservator of the Department of Archaeology of the museum between 1912 and 1938, and was also responsible for publishing the Guide of the Collections of Classical Archaeology of the National Museum, in 1919.[15][16][17]

Besides the forementioned coffin of Sha-Amun-en-su, the museum possesses other three sarcophagi, from the Third Intermediate Period and the Late Era, belonging to three priests of Amun: Hori, Pestjef, and Harsiese. The museum also conserves six human mummies (four adults and two children), as well as a number of mummies and sarcophagi of animals (cats, ibises, fishes, and crocodiles). Among the human examples, the highlight is a mummy of a woman from the Roman Period, which is considered extremely rare for the preparatory technique used, of which there are only eight similar examples worldwide. Called "princess of the Sun" or "princess Kherima", the mummy has her members and fingers of the hands and feet individually swaddled and is richly adorned, with painted strips.[17] "Princess Kherima" is one of the most popular items of the National Museum collection, being even related to accounts of parapsychological experiences and collective trances, that supposedly occurred in the 1960s. "Kherima" also inspired the romance The Secret of the Mummy by Everton Ralph, member of the Rosicrucian society.[15][18][19]

The collection of votive and funerary steles is composed of dozens of pieces dated, in their majority, from the Intermediate Period and the Late Era. The steles of Raia and Haunefer, which are graved with titles of Semitic origins present in the Bible and in the tablets of Mari, stand out, as well as an unfinished stele, attributed to the emperor Tiberius, of the Roman Period. The museum also has a vast collection of shabtis, i.e. statuettes representing funerary servers, including a group of pieces that belonged to pharaoh Seti I, excavated from his tomb at the Valley of the Kings. Still among the group of rare artifacts, there is a limestone statue of a young woman, dated of the New Kingdom, carrying a conic ointment vessel on the top of her head — an iconography that is almost exclusively found among paintings and reliefs. The collection also includes fragments of reliefs, masks, statues of deities in bronze, stone and wood (such as representations of Ptah-Sokar-Osiris), canopic jars, alabaster bowls, funerary cones, jewels, amulets, etc.[15][17][20]

ثقافات المتوسط

الآثار البرازيلية

انظر أيضاً

- پاسو دى ساو كريستوڤاو، القصر التاريخي الذي يضم المتحف الوطني

- متحف البرازيل التاريخي الوطني

الهامش

- ^ "Museus em Números, Vol. 1" (PDF). Instituto Brasileiro de Museus – IBRAM. p. 73. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-10-29.

- ^ "200 Anos do Museu Nacional" (PDF). Associação Amigos do Museu Nacional. p. 8. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-07-08.

- ^ أ ب ت ث (in pt)Museu Nacional - UFRJ. Museus do Rio. Archived from the original. You must specify the date the archive was made using the

|archivedate=parameter. http://www.museusdorio.com.br/joomla/index.php?option=com_k2&view=item&id=12:museu-nacional. Retrieved on 2017-02-15 - ^ أ ب Grande Enciclopédia Larousse Cultural. Santana de Parnaíba: Banco Safra. 1998. p. 4132.

- ^ (in pt)O Museu. Museu Nacional - UFRJ. Archived from the original. You must specify the date the archive was made using the

|archivedate=parameter. http://www.museunacional.ufrj.br/dir/omuseu/omuseu.html. Retrieved on 2017-02-15 - ^ (in pt)A Revista Arquivos e a Biblioteca do Museu Nacional. Revista do Arquivo Nacional. Archived from the original. You must specify the date the archive was made using the

|archivedate=parameter. http://linux.an.gov.br/seer/index.php/info/article/view/574/489. Retrieved on 2017-02-15 - ^ أ ب "Rio's 200-year old National Museum hit by massive fire". Reuters. 2 September 2018. Archived from the original on 2 September 2018. Retrieved 2 September 2018.

{{cite web}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; 3 سبتمبر 2018 suggested (help); Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ أ ب "Fire engulfs 200-year-old Brazil museum". BBC. 2 September 2018. Archived from the original on 2 September 2018. Retrieved 2 September 2018.

{{cite web}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; 3 سبتمبر 2018 suggested (help); Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ أ ب "Incêndio atinge prédio do Museu Nacional, no Rio". UOL Notícias (in البرتغالية). 2 September 2018. Retrieved 2 September 2018.

- ^ Pamplona, Nicola; Alegretti, Laís (2 September 2018). "Incêndio de grandes proporções atinge Museu Nacional na Quinta da Boa Vista, no Rio". Folha de S.Paulo (in البرتغالية). Retrieved 3 September 2018.

- ^ "Fogo destrói Museu Nacional, mais antigo centro de ciência do País". Estadão (in البرتغالية). 2 September 2018. Retrieved 3 September 2018.

- ^ Phillips, Dom (3 September 2018). "Brazil museum fire: 'incalculable' loss as 200-year-old Rio institution gutted". The Guardian.

- ^ Sears, P M (1963). "Recovery of the Bendego Meteorite". Merteoritics. 2 (1): 22–23. Retrieved 27 December 2017.

- ^ أ ب (in pt)Guia de Exposições do Museu Nacional - Egito Antigo (I). Museu Nacional/UFRJ. Archived from the original. You must specify the date the archive was made using the

|archivedate=parameter. http://www.museunacional.ufrj.br/guiaMN/Guia/paginas/4/princ9.htm. Retrieved on 2017-02-09 - ^ أ ب ت ث Barkos, Margaret Marchiori (2004). Egiptomania – O Egito no Brasil. São Paulo: Paris Editorial. pp. 31–35. ISBN 85-72-44261-8.

- ^ أ ب O Museu Nacional. São Paulo: Banco Safra. 2007. p. 222.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Brancaglion Junior, Antonio (2007). Revelando o Passado: estudos da coleção egípcia do Museu Nacional (in In: Lessa, Fábio de Souza & Bustamente, Regina. "Memoria & festa"). Rio de Janeiro: Mauad Editora. pp. 75–80.

- ^ O Museu Nacional. São Paulo: Banco Safra. 2007. pp. 41–42.

- ^ (in pt)Múmia Kherima intriga pesquisadores do Museu Nacional. O Globo. 2016. Archived from the original. You must specify the date the archive was made using the

|archivedate=parameter. http://oglobo.globo.com/sociedade/historia/mumia-kherima-intriga-pesquisadores-do-museu-nacional-10998769. Retrieved on 2017-02-09 - ^ (in pt)Guia de Exposições do Museu Nacional – Egito Antigo (II). Museu Nacional/UFRJ. 2016. Archived from the original. You must specify the date the archive was made using the

|archivedate=parameter. http://www.museunacional.ufrj.br/guiaMN/Guia/paginas/4/principal10.htm. Retrieved on 2017-02-09

وصلات خارجية

- National Museum website

- The National Museum and its European employees Jens Andermann

- The National Museum at Rio de Janeiro Jens Andermann

- Pages using gadget WikiMiniAtlas

- CS1 errors: unsupported parameter

- CS1 errors: archive-url

- CS1 البرتغالية-language sources (pt)

- Coordinates on Wikidata

- Articles containing برتغالية-language text

- Pages using Lang-xx templates

- مقالات ذات عبارات بحاجة لمصادر

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- متاحف في ريو دي جانيرو (مدينة)

- متحف البرازيل الوطني

- متاحف تاريخي طبيعي في البرازيل

- متاحف أثرية في البرازيل

- جامعة ريو دي جانيرو الفدرالية

- مؤسسات بحثية في البرازيل

- متاحف تأسست في 1818

- تأسيسات عقد 1810 في البرازيل

- صفحات مع الخرائط