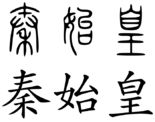

تشين شي هوانگ

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

تشين شي هوانگ (الصينية: 秦始皇; lit. 'First Emperor of Qin' النطق ؛ 18 فبراير 259 ق.م. – 10 سبتمبر 210 ق.م.)، هو مؤسس أسرة تشين (秦朝) وكان أول أباطرة الصين الموحدة. وُلد باسم ينگ ژنگ (嬴政) أو ژاو ژنگ (趙政)، أمير دولة تشين. أصبح الملك ژنگ من تشين (秦王政) عندما بلغ الثالثة عشر من عمره، ثم أول امبراطور للصين عندما كان في الثامنة والثلاثين بعدما غزت تشين جميع الدويلات المتناحرة وتوحيد عموم الصين عام 221 ق.م.[2] بدلاً من الاحتفاظ بلقب "الملك" الذي حمله حكام تشانگ وژوو، حكم باسم الامبراطور الأول (始皇帝) من أسرة تشين من 220 حتى 210 ق.م. وابتكر لقب شخصي لنفسه، "الامبراطور" (皇帝، هوانگدي )، كما أشار إليه استخدامه لكلمة "الأول"، والذي استمر استخدامه من قبل الحكام الصينيين في الألفيتين التاليتين.

في عهده، توسع جنرالاته بشكل كبير في مساحة الدولة الصينية: الحملات الجنوبية على تشو والتي أضافت بشكل دائم أراضي يوه في هونان وگوانگدونگ إلى النطاق الثقافي الصيني؛ الحملات في آسيا الوسطى لغزو هضبة أوردوس من شيونگنو البدو، بالرغم من أنها في النهاية أدت أيضاً إلى الاتحاد تحت مودو تشيانو. كذلك عمل تشين شي هوانگ مع وزيره لي سي لتنفيذ اصلاحات اقتصادية وسياسية هدفت إلى توحيد الممارسات المتنوعة للدويلات الصينية المبكرة.[2] تقليدياً يقال أنه حظر وحرق الكثير من الكتب وأعدم العلماء، على الرغم من أن التحري الدقيق يجعل هذه الأقاويل مثاراً للشك.[3] مشروعات الأشغال العامة في عهده تضمنت توحيد أسوار الدويلات المتفرقة في سور الصين العظيم ونظام طرقات وطني جديد ضخم، فضلاً عن ضريح بحجم المدينة تحت حراسة جيش التراكوتا بالحجم الطبيعي. حكم حتى وفاته عام 210 ق.م. بعد بحث عقيم عن إكسير الخلود.

أصل الاسم

الميلاد والنسب

الصين قبل توليه الحكم

كانت الصين قبل هذا الإمبراطور ممزقة ، وكان أمراؤها يتصارعون ويتقاتلون. فعاشت هذه الإمارات في ظروف حربية مهلكة. إلا أن إحدى الولايات واسمها الصين (تشين) اعتنقت المبادىء السلوكية الضرورية، أي اعتنقت فلسفة ترى أنه من الضروري أن يكون للإنسان وللدولة أيضاً مبادىء قوية وملزمة، وأن هذه المبادىء على الرغم من أن الحاكم هو من يقرها ويضعها و لابد أن تكن سارية على الجميع وأن الحاكم يجب أن يكون قدوة حسنة. وبفضل هذا المبدأ أصبحت هذه الولاية أقوى الولايات الصينية. واستطاع تشي أن ينصب نفسه ملكاً عل الصين كلها اطلق على نفسه "تشي هانگ تي" أي إمبراطور الصين العظيم.

كملك لتشين

الوصاية على العرش

محاولة انقلاب لاو أي

محاولة الاغتيال الأولى

محاولة الاغتيال الثانية

توحيد الصين

In 230 BC, King Zheng unleashed the final campaigns of the فترة الدويلات المتناحرة, setting out to conquer the remaining independent kingdoms, one by one.

The first state to fall was Hán (韓; sometimes called Hann to distinguish it from the Hàn 漢 of Han dynasty), in 230 BC. Then Qin took advantage of natural disasters in 229 BC to invade and conquer Zhào, where Qin Shi Huang had been born.[4][5] He now avenged his poor treatment as a child hostage there, seeking out and killing his enemies.

Qin armies conquered the state of Zhao in 228 BC, the northern country of Yan in 226 BC, the small state of Wei in 225 BC, and the largest state and greatest challenge, Chu, in 223 BC.[6]

In 222 BC, the last remnants of Yan and the royal family were captured in لياودونگ in the northeast. The only independent country left was now state of Qi, in the far east, what is now the Shandong peninsula. Terrified, the young king of Qi sent 200,000 people to defend his western borders. In 221 BC, the Qin armies invaded from the north, captured the king, and annexed Qi. Some of the strategies Qin used to unify China were to standardize the trade and communication, currency and language.

For the first time, all of China[محل شك] was unified under one powerful ruler. In that same year, King Zheng proclaimed himself the "First Emperor" (始皇帝, Shǐ Huángdì), no longer a king in the old sense and now far surpassing the achievements of the old Zhou Dynasty rulers.[7] The emperor made the He Shi Bi into the Imperial Seal, known as the "Heirloom Seal of the Realm". The words, "Having received the Mandate from Heaven, may (the emperor) lead a long and prosperous life." (受命於天,既壽永昌) were written by Prime Minister Li Si, and carved onto the seal by Sun Shou. The Seal was later passed from emperor to emperor for generations to come.

In the South, military expansion in the form of campaigns against the Yue tribes continued during his reign, with various regions being annexed to what is now Guangdong province and part of today's Vietnam.[5]

كامبراطور لتشين

سياسته الداخلية

بسرعة شديدة أدخل تشي تعديلات جهرية لما يجب أن تكون علي باقي اللايات من وحدة واستقرار انضباط ، وقام بتقسيم دلته إلى 36 لاية جعل لكل منها حاكماً مدنياً وجعل لها جيشاً . وعين لكل جيش قائد . ثم أنه جعل هذه المناصب بالتعيين وليست وراثية ، اضافة إلى ذلك عين قائداً أو مستشاراً ليوازن بين الحاكم المدني والحاكم العسكري حتى لا يتفرد أحد بالسلطة .

أصدر بعد ذلك قراراً بنقل الأغنياء والطبقة الأرستقراطية إلى العاصمة ليكونوا تحت رقابته الشديدة .

ربط المدن والعواصم بطرق واسعة طيلة و أعلن بضوح : أنه مالم تكن الدولة مرتبطة ببعضها البعض فلن يكون سهلاً على الحاكم أن يسيطر عليها .

وعلى الرغم من ذكائه في اختيار القادة وحكام الولايات ربط البلاط ربطاً محكماً، وتوحيد الصين والموازين والمقاييس وأحجام العربات وأشكال الحروف. فإنه أرتكب أحد أكبر حماقات التاريخ، فإنه احرق كل الكتب في عصره ولم يستبق إلا بعض الكتب عن الزراعة والصناعة، ويقال انه احتفظ بنسخة من كل كتاب أحرقه وأودعها مكتبة القصر، ولكن لا يوجد أي دليل مؤكد على ذلك. فقد أراد بهذا العمل الحمق أن يقضي على كونفوشيوس وكل تعاليمه الأخلاقية.

الاصلاحات الإدارية

الاصلاحات الاقتصادية

الفلسفة

Qin Shi Huang also followed the school of the five elements, earth, wood, metal, fire and water.(五德終始說) Zhao Zheng's birth element is water, which is connected with the colour black. It was also believed that the royal house of the previous dynasty Zhou had ruled by the power of fire, which was the colour red. The new Qin dynasty must be ruled by the next element on the list, which is water, represented by the colour black. Black became the colour for garments, flags, pennants.[1] Other associations include north as the cardinal direction, winter season and the number six.[8] Tallies and official hats were 15 centimetres (6 in) long, carriages two metres (6 ft) wide, one pace (步, Bù) was 1.4 metres (4.6 ft).[1]

بينما كانت فترة الدويلات المتناحرة السابقة تتسم بالقتال الدائم، it was also considered the golden age of free thought.[9] Qin Shi Huang eliminated the Hundred Schools of Thought which incorporated Confucianism and other philosophies.[9][10] After the unification of China, with all other schools of thought banned, legalism became the endorsed ideology of the Qin dynasty,[11] which was basically a system that required the people to follow the laws or be punished accordingly.

Beginning in 213 BC, at the instigation of Li Si and to avoid scholars' comparisons of his reign with the past, Qin Shi Huang ordered most existing books to be burned with the exception of those on astrology, agriculture, medicine, divination, and the history of the State of Qin.[12] This would also serve the purpose of furthering the ongoing reformation of the writing system by removing examples of obsolete scripts.[13] Owning the Book of Songs or the Classic of History was to be punished especially severely. According to the later Records of the Grand Historian, the following year Qin Shi Huang had some 460 scholars buried alive for owning the forbidden books.[1][12] The emperor's oldest son Fusu criticised him for this act.[14]

Recent research suggests that the “burying of the Confucian scholars alive” is a Confucian martyrs’ legend; rather, the emperor ordered the killing (坑 kēng) of a group of alchemists after having found that they had fooled him. In Han times, the Confucian scholars, who had served the Qin loyally, used that incident to distance themselves from the failed dynasty. Kong Anguo (孔安國 ca. 165 - ca. 74 BC), a descendant of Confucius, turned the alchemists (方士 fāngshì) into Confucianists (儒 rú) and entwined the martyrs´ legend with the strange story of the rediscovery of the lost Confucian books behind a demolished wall in the house of his ancestors.[15] The emperor's own library still had copies of the forbidden books but most of these were destroyed later when Xiang Yu burned the palaces of Xianyang in 206 BC.[16]

محاولة الاغتيال الثالثة

الأشغال العامة

السور العظيم

The Qin fought nomadic tribes to the north and north-west. The Xiongnu tribes were not defeated and subdued, thus the campaign was tiring and unsuccessful, and to prevent the Xiongnu from encroaching on the northern frontier any longer, the emperor ordered the construction of an immense defensive wall.[5][17][18] هذا السور، الذي حشد لبنائه مئات الآلاف من الرجال، مات منهم أعداد غير معروفة، هو سابق لـسور الصين العظيم الحالي. It connected numerous state walls which had been built during the previous four centuries, a network of small walls linking river defences to impassable cliffs.[19][20]

قناة لينگچو

A famous South China quotation was "In the North there is the Great wall, in the South there is the Lingqu canal" (北有長城、南有靈渠, Běiyǒu chángchéng, nányǒu língqú).[21] In 214 BC the Emperor began the project of a major canal to transport supplies to the army.[22] The canal allows water transport between north and south China.[22] The canal, 34 kilometres in length, links the Xiang River which flows into the Yangtze and the Li Jiang, which flows into the Pearl River.[22] The canal connected two of China's major waterways and aided Qin's expansion into the south-west.[22] The construction is considered one of the three great feats of Ancient Chinese engineering, the others being the Great Wall and the Sichuan Dujiangyan Irrigation System.[22]

سياسته الخارجية

أما سياسته الخارجية فكانت هي الأخرى عنيفة ، فقد كان على علاقة متينة بجيرانه ، كما أن جيوشه لم تتوقف عن غزو البلاد الأخرى الواقعة في الشمال وضمها إلى الصين ، ثم أنه ربط الأسوار الواقعة على حدود الصين بعضها ببعض ، فكان سور الصين العظيم، الذي ما يزال قائماً حتى اليوم وبسبب هذه الحروب الكبيرة فقد فرض ضرائب كبيرة على الناس، فكرهه الناس، وكان من الصعب إسقاطه، لذلك حاول الشعب اغتياله. ولم يفلخ أحد في ذلك. إلا انه مات في فراشه، وبعد وفاته تولى العرش ابنه الثاني، ولم يبقى في موقعه سوى أربعة سنوات أنتهت بإغتياله، وبموت ابنه هذا انهارت إمبراطورية الصين.

إكسير الحياة

Later in his life, Qin Shi Huang feared death and desperately sought the fabled elixir of life, which would supposedly allow him to live forever. He was obsessed with acquiring immortality and fell prey to many who offered him supposed elixirs.[23] He visited Zhifu Island three times in order to achieve immortality.[24]

In one case he sent Xu Fu, a Zhifu islander, with ships carrying hundreds of young men and women in search of the mystical Penglai mountain.[25] They were sent to find Anqi Sheng, a 1,000-year-old magician whom Qin Shi Huang had supposedly met in his travels and who had invited him to seek him there.[26] These people never returned, perhaps because they knew that if they returned without the promised elixir, they would surely be executed. Legends claim that they reached Japan and colonized it.[23] It is also possible that the book burning, a purge on what could be seen as wasteful and useless literature, was, in part, an attempt to focus the minds of the Emperor's best scholars on the alchemical quest. Some of the executed scholars were those who had been unable to offer any evidence of their supernatural schemes. This may have been the ultimate means of testing their abilities: if any of them had magic powers, then they would surely come back to life when they were let out again.[27] Since the great emperor was afraid of death and "evil spirits", he had workers build a series of tunnels and passageways to each of his palaces (he owned over 200), because traveling unseen would supposedly keep him safe from the evil spirits. Qin Shi Huang was said to have died by drinking mercury, believing it to be an elixir of immortality.

وفاته والأحداث اللاحقة

In 211 BC a large meteor is said to have fallen in Dōngjùn (東郡) in the lower reaches of the Yellow River. On it, an unknown person inscribed the words "The First Emperor will die and his land will be divided" (始皇死而地分).[28] When the emperor heard of this, he sent an imperial secretary to investigate this prophecy. No one would confess to the deed, so all the people living nearby were put to death. The stone was then burned and pulverized.[29]

The Emperor died during one of his tours of Eastern China, on September 10, 210 BC (Julian Calendar) at the palace in Shaqiu prefecture (沙丘平台, Shāqiū Píngtái), about two months away by road from the capital Xianyang.[30][30][31][32] Reportedly, he died from Chinese alchemical elixir poisoning due to ingesting mercury pills, made by his alchemists and court physicians.[33] Ironically, these pills were meant to make Qin Shi Huang immortal.[33]

مؤامرة الامبراطور الثاني

After the Emperor's death, Prime Minister Li Si, who accompanied him, became extremely worried that the news of his death could trigger a general uprising in the Empire.[30] It would take two months for the entourage to reach the capital, and it would not be possible to stop the uprising. Li Si decided to hide the death of the Emperor, and return to Xianyang.[30] Most of the Imperial entourage accompanying the Emperor were left ignorant of the Emperor's death; only a younger son, Ying Huhai, who was travelling with his father, the eunuch Zhao Gao, Li Si, and five or six favourite eunuchs knew of the death.[30] Li Si also ordered that two carts containing rotten fish be carried immediately before and after the wagon of the Emperor. The idea behind this was to prevent people from noticing the foul smell emanating from the wagon of the Emperor, where his body was starting to decompose severely as it was summertime.[30] They also pulled down the shade so no one could see his face, changed his clothes daily, brought food and when he had to have important conversations, they would act as if he wanted to send them a message.[30]

Eventually, after about two months, Li Si and the imperial court reached Xianyang, where the news of the death of the emperor was announced.[30] Qin Shi Huang did not like to talk about his own death and he had never written a will. After his death, the eldest son Fusu would normally become the next emperor.[34]

Li Si and the chief eunuch Zhao Gao conspired to kill Fusu because Fusu's favorite general was Meng Tian, whom they disliked[34] and feared; Meng Tian's brother, a senior minister, had once punished Zhao Gao.[35] They believed that if Fusu was enthroned, they would lose their power.[34] Li Si and Zhao Gao forged a letter from Qin Shi Huang saying that both Fusu and General Meng must commit suicide.[34] The plan worked, and the younger son Hu Hai became the Second Emperor, later known as Qin Er Shi or "Second Generation Qin."[30]

Qin Er Shi, however, was not as capable as his father. Revolts quickly erupted. His reign was a time of extreme civil unrest, and everything built by the First Emperor crumbled away within a short period.[5] One of the immediate revolt attempts was the 209 BC Daze Village Uprising led by Chen Sheng and Wu Guang.[28]

العائلة

التالون هم بعض أفراد عائلته، وقرابتهم لتشين شي هوانگ:

- الجد الأكبر Huiwen of Qin (秦惠文王)

- Great grandfather ژاوشيانگ من تشين (秦昭襄王)

- الجد Xiaowen of Qin (秦孝文王)

- الأب King Zhuangxiang of Qin (秦庄襄王)

- الأم Zhao Ji (趙姬)

- الشقيق: تشانگان جون (長安君成蟜)[36]

- تشين شي هوانگ نفسه

- الابن: فوسو

- الابن: گاو

- الابن: جيانگلو

- الابن: تشين إر تشي

لتشين شي هوانگ أقل من 20 ابن، لكن أسماء معظمهم مفقودة.

ذكراه

الضريح

تأريخ

اختلف المؤرخون حول قيمة الإمبراطور الأول للصين. أما الشيوعيون فيرون فيه حاكما تقدمياً. ويقارنه الغرب بنابليون، ولكن من المؤكد أن هذا الإمبراطور حقق من الوحدة والانضباط والاستمرار والانضباط كثيراً، ولم يفلح أحد بعد ذلك في تغيير هذا الاستمرار والوحدة التي سادت الصين لأية سبب.

انظر أيضاً

- حرق الكتب ودفن العلماء

- ينگ (اسم عائلة صيني)

- تشين يويانگ من يان (دويلة)

- تشين (اسم عائلة)

- جين (اسم كوري)

- قبيلة الهاتا

- الليدي منگ جيانگ

- هه شي بي

المصادر

- ^ أ ب ت ث Wood, Frances. (2008). China's First Emperor and His Terracotta Warriors, pp. 2–33. Macmillan Publishing, 2008. ISBN 0-312-38112-3.

- ^ أ ب Duiker, William J. & al. World History: Volume I: To 1800, 5th ed., p. 78. Thomson Higher Education Publishing, 2006. ISBN 0-495-05053-9.

- ^ Ren Changhong & al. Rise and Fall of the Qin Dynasty. Asiapac Books PTE Ltd., 2000. ISBN 981-229-172-5.

- ^ Hk.chiculture.net. "HKChinese culture." 破趙逼燕. Retrieved on 2009-01-18.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Haw, Stephen G. (2007). Beijing a Concise History. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-39906-7. p 22 -23.

- ^ Sima Qian: The First Emperor. Tr. by Raymond Dawson. Oxford University Press. Edition 2007, Chronology, p. xxxix

- ^ Clements, Jonathan (2006). The First Emperor of China. Sutton Publishing. ISBN 0-7509-3959-1. pp. 82, 102-103, 131, 134.

- ^ Murowchick, Robert E. (1994). China: Ancient Culture, Modern Land. University of Oklahoma Press, 1994. ISBN 0-8061-2683-3, ISBN 978-0-8061-2683-8. p105.

- ^ أ ب Goldman, Merle. (1981). China's Intellectuals: Advise and Dissent. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-11970-3, ISBN 978-0-674-11970-3. pg 85.

- ^ Chaurasia, Radhey Shyam. (2004). History of Modern China. Atlantic Publishers & Distributors. ISBN 81-269-0315-5, ISBN 978-81-269-0315-3. pg 317.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةChang - ^ أ ب Li-Hsiang Lisa Rosenlee. Ames, Roger T. (2006). Confucianism and Women: A Philosophical Interpretation. SUNY Press. ISBN 0-7914-6749-X, 9780791467497. p 25.

- ^ Clements, Jonathan (2006). The First Emperor of China. p. 131.

- ^ Twitchett, Denis. Fairbank, John King. Loewe, Michael. The Cambridge History of China: The Ch‘in and Han Empires 221 B.C.-A.D. 220. Edition: 3. Cambridge University Press, 1986. ISBN 0-521-24327-0, ISBN 978-0-521-24327-8. p 71.

- ^ Neininger, Ulrich, Burying the Scholars Alive: On the Origin of a Confucian Martyrs’ Legend, Nation and Mythology (in East Asian Civilizations. New Attempts at Understanding Traditions), vol. 2, 1983, eds. Wolfram Eberhard et al., pp 121-136. ISBN 3-88676-041-3. http://www.ulrichneininger.de/?p=461

- ^ From Records of the Grand Historian, translated by Raymond Dawson in Sima Qian: The First Emperor. Oxford University Press, ed. 2007, pp. 74-75, 119, 148-9

- ^ Li, Xiaobing. (2007). A History of the Modern Chinese Army. University Press of Kentucky, 2007.ISBN 0813124387, ISBN 978-0-8131-2438-4. p.16

- ^ Grousset, Rene (1970). The Empire of the Steppes. Rutgers University Press. pp. 26–27. ISBN 0-8135-1304-9.

- ^ Clements, Jonathan (2006). The First Emperor of China. pp. 102-103.

- ^ Huang, Ray. (1997). China: A Macro History. Edition: 2, revised, illustrated. M.E. Sharpe publishing. ISBN 1-56324-731-3, ISBN 978-1-56324-731-6. p 44

- ^ Sina.com. "Sina.com." 秦代三大水利工程之一:灵渠. Retrieved on 2009-02-02.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج Mayhew, Bradley. Miller, Korina. English, Alex. South-West China: lively Yunnan and its exotic neighbours. Lonely Planet. ISBN 1-86450-370-X, 9781864503708. pg 222.

- ^ أ ب Ong, Siew Chey. Marshall Cavendish. (2006). China Condensed: 5000 Years of History & Culture. ISBN 981-261-067-7, ISBN 978-981-261-067-6. p 17.

- ^ Aikman, David. (2006). Qi. Publishing Group. ISBN 0-8054-3293-0, ISBN 978-0-8054-3293-0. p 91.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةWintle - ^ Fabrizio Pregadio. The Encyclopedia of Taoism. London: Routledge, 2008: 199

- ^ Clements, Jonathan (2006). The First Emperor of China. pp. 131, 134.

- ^ أ ب Liang, Yuansheng. (2007). The Legitimation of New Orders: Case Studies in World History. Chinese University Press. ISBN 962-996-239-X, 9789629962395. pg 5.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةRGH - ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د ذ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةFirsteselect - ^ O'Hagan Muqian Luo, Paul. (2006). 讀名人小傳學英文: famous people. 寂天文化. publishing. ISBN 986-184-045-1, ISBN 978-986-184-045-1. p16.

- ^ Xinhuanet.com. "" 中國考古簡訊:秦始皇去世地沙丘平臺遺跡尚存. Xinhuanet. Retrieved on 2009-01-28.

- ^ أ ب Wright, David Curtis (2001). The History of China. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 49. ISBN 0-313-30940-X.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Tung, Douglas S. Tung, Kenneth. (2003). More Than 36 Stratagems: A Systematic Classification Based On Basic Behaviours. Trafford Publishing. ISBN 1-4120-0674-0, ISBN 978-1-4120-0674-3.

- ^ Sima Qian: The First Emperor. Tr. Raymond Dawson. Oxford University Press. Edition 2007. p. 54

- ^ Wikisource Records of the Grand Historian Chapter 6

قراءات إضافية

- Bodde, Derk (1987). "The State and Empire of Ch‘in". In Twitchett, Denis; Loewe, Michael (eds.). The Cambridge history of China. Vol. 1. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press. pp. 20–103. ISBN 0-521-21447-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Clements, Jonathan (2006). The First Emperor of China. Sutton Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7509-3960-7.

- Cotterell, Arthur (1981). The first emperor of China: the greatest archeological find of our time. New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston. ISBN 0-03-059889-3.

- Guisso, R.W.L.; Pagani, Catherine; Miller, David (1989). The first emperor of China. New York: Birch Lane Press. ISBN 1-55972-016-6.

- Yu-ning, Li, ed. (1975). The First Emperor of China. White Plains, N.Y.: International Arts and Sciences Press. ISBN 0-87332-067-0.

- Portal, Jane (2007). The First Emperor, China's Terracotta Army. British Museum Press. ISBN 978-1-932543-26-1.

- Qian, Sima (1961). Records of the Grand Historian: Qin dynasty. Burton Watson, trans. New York: Columbia Univ. Press.

- Yap, Joseph P (2009). Wars With the Xiongnu, A Translation From Zizhi tongjian. AuthorHouse. ISBN 978-1-4490-0604-4.

تشين شي هوانگ

| ||

| سبقه ژوانگشيانگ |

ملك تشين 246 ق.م. - 221 ق.م. |

دمج اللقب مع التاج |

| لقب حديث | إمبراطور الصين 221 ق.م. - 210 ق.م. |

تبعه چين إر شي |

- Articles containing صينية-language text

- Pages with plain IPA

- Transliteration template errors

- Articles containing Chinese-language text

- مقالات ذات عبارات محل شك

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- أباطرة أسرة تشين

- حكام أطفال من آسيا

- ملوك صينيون من القرن الثالث ق.م.

- أشخاص من هاندان

- رجال دين سابقون

- ملوك مؤسسون

- مواليد 260 ق.م.

- وفيات 210 ق.م.

- قادة عسكريون

- قتلى جماعيون صينيون

- ناجون من محاولات اغتيال

- تشين شي هوانگ

- الشرعوية (فلسفة صينية)