المعتقد المحلي السلاڤي

| جزء من سلسلة عن |

| المعتقد المحلي السلاڤي |

|---|

|

المعتقد المحلي السلاڤي، ويُعرف أيضاً بإسم رودنوڤري Rodnovery،[note 1] is a modern Pagan religion. Classified as a new religious movement, its practitioners harken back to the historical belief systems of the Slavic peoples of Central and Eastern Europe. "Rodnovery" is a widely accepted self-descriptor within the community, although there are Rodnover organisations which further characterise the religion as Vedism, Orthodoxy, and Old Belief.

Rodnovers typically regard their religion as a faithful continuation of ancient beliefs that survived as folk religion or as conscious "double belief" following the Christianisation of the Slavs in the Middle Ages.[note 2] Rodnovery draws upon surviving historical and archaeological sources, folk religion and even non-Slavic sources such as Hinduism. Rodnover theology and cosmology may be described as pantheism and polytheism—worship of the supreme God of the universe and of the multiple gods, ancestors and spirits of nature identified through Slavic culture. Adherents usually meet together in groups to conduct religious ceremonies. These typically entail the invocation of gods, sacrifices and the pouring of libations, dances and a communal meal.

Rodnover ethical thinking emphasises the good of the collective over the rights of the individual. The religion is patriarchal, and attitudes towards sex and gender are generally conservative.[3] Rodnovery has developed distinctive strains of political and identitary philosophy. Rodnover organisations often characterise themselves as ethnic religions, emphasising that the religion is bound to Slavic ethnicity. This often manifests as ethnic nationalism, opposition to miscegenation and the belief in the fundamental difference of racial groups. Rodnovers often glorify Slavic history, criticising the impact of Christianity in Slavic countries and arguing that these nations will play a central role in the world's future. Rodnovers share a strong feeling that their religion represents a paradigmatic shift which will overcome the mental constraints imposed through feudalism and the continuation of what they call "mono-ideologies".

The contemporary organised Rodnovery movement arose from a multiplicity of sources and charismatic leaders just at the brink of the collapse of the Soviet Union and spread rapidly by the mid-1990s and the 2000s. Antecedents are to be found in late 18th- and 19th-century Slavic Romanticism, which glorified the pre-Christian beliefs of Slavic societies. Active religious practitioners devoted to establishing Slavic Native Faith appeared in Poland and Ukraine in the 1930s and 1940s. Following the Second World War and the establishment of communist states throughout the Eastern Bloc, new variants were established by Slavic emigrants living in Western countries, being later introduced in Central and Eastern European countries after the collapse of the Soviet Union. In recent times, the movement has been increasingly studied in academic scholarship.

استعراض

Slavic folk religion and double belief

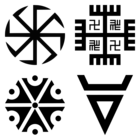

الرمزية

Media related to Rodnover symbols at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Rodnover symbols at Wikimedia Commons

المصطلحات

"Orthodoxy", "Old Belief", "Vedism" and other terms

General descriptors: Western "pagan" and Slavic yazich

المعتقدات

اللاهوت وعلم الكون

الأخلاق

Identity and political philosophy

There is no evidence that the early Slavs ever conceived of themselves as a unified ethno-cultural group.

Ethnic nationalism

Views on Slavic and Indo-European history

Views on Christianity

التنظيم والشعائر والممارسات

التجمعات والقلاع والمعابد

الكهانة

التاريخ

The origins of Slavic Native Faith have been traced to the Romantic movement of late eighteenth and nineteenth-century Europe, which was a reaction against rationalism and the Age of Enlightenment.[7] This was accompanied by a growth in nationalism across Europe, as intellectuals began to assert their own national heritage.[7] Whereas calls to re-establish pre-Christian belief systems existed within the German and Austrian far-right nationalist movements during the early twentieth century, the same did not happen in its Russian counterpart.[8]

In 1818, the Polish ethnographer Zorian Dołęga-Chodakowski (Adam Czarnocki) in the work O Sławiańszczyźnie przed chrześcijaństwem ("About Slavs before Christianity") declared himself a "pagan" and stated that the Christianisation of the Slavic peoples had been a mistake.[9] Thus he became a precursor of return to Slavic religion in Poland and all Slavic countries.[10] Similarly, the Polish philosopher Bronisław Trentowski saw the historical religion of the Slavs as a true path to understanding the divine creator, arguing that Christianity failed to do so.[11] It was this Romantic rediscovery and revaluing of historical and pre-Christian that prepared the way for the later emergence of Slavic Native Faith.[12]

1930s–1940s: Early developments

See also

Media related to Slavic neopaganism at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Slavic neopaganism at Wikimedia Commons- Heathenry

- Celtic Reconstructionist Paganism

- Veda Slovena

- Armenian neopaganism

- Baltic neopaganism

- Caucasian neopaganism

- Semitic neopaganism

- Zalmoxianism

Notes

- ^ The term derives from the Proto-Slavic roots *rod (род), which means anything "indigenous", "ancestral" and "native", also "genus", "generation", "kin", "race" (cf. Russian родная rodnaya or родной rodnoy), and is also the name of the universe's supreme God according to Slavic knowledge; and *vera, which means "faith", "religion".[1] The term has many emic variations, all compounds, in different Slavic languages, including:

- بالبيلاروسية: Раднавер'е

- بالبلغارية: Родноверие

- بوسنية: [Rodnovjerje] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)

- مقدونية: Родноверие

- تشيكية: Rodnověří

- كرواتية: Rodnovjerje

- پولندية: Rodzimowierstwo; Rodzima Wiara

- روسية: Родноверие, romanized: Rodnoverie

- سلوڤاكية: Rodnoverie

- Slovene: Rodnoverstvo

- بالصربية: Родноверје

- أوكرانية: Рідновірство; Рідновір'я, romanized: Ridnovirstvo; Ridnovirya

- ^ The idea that indigenous Slavic religion was preserved in a conscious "double belief" following the Christianisation of the Slavs is put into question by some contemporary scholars.

المراجع

الهامش

- ^ Simpson & Filip 2014, p. 36.

- ^ Petrović 2013, passim; Rountree 2015, p. 217.

- ^ Aitamurto & Gaidukov 2013, p. 152.

- ^ Rouček, Joseph Slabey, ed. (1949). "Ognyena Maria". Slavonic Encyclopedia. New York: Philosophical Library. p. 905

- ^ Ivanits 1989, pp. 15, 16.

- ^ Ivanits 1989, p. 17.

- ^ أ ب Ivakhiv 2005c, p. 215.

- ^ Laruelle 2008, p. 285.

- ^ Gajda 2013, pp. 46–48.

- ^ Potrzebowski 2016, p. 12.

- ^ Gajda 2013, pp. 49–51.

- ^ Gajda 2013, p. 58.

المصادر

المصادر الثانوية

- Aitamurto, Kaarina (2006). "Russian Paganism and the Issue of Nationalism: A Case Study of the Circle of Pagan Tradition". The Pomegranate: The International Journal of Pagan Studies. Vol. 8, no. 2. pp. 184–210.

{{cite news}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ——— (2008). "Egalitarian Utopias and Conservative Politics: Veche as a Societal Ideal within Rodnoverie Movement". Axis Mundi: Slovak Journal for the Study of Religions. Vol. 3. pp. 2–11.

{{cite news}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ——— (2011). "Modern Pagan Warriors: Violence and Justice in Rodnoverie". In James R. Lewis (ed.). Violence and New Religious Movements. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 231–248. ISBN 9780199735631.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ——— (2016). Paganism, Traditionalism, Nationalism: Narratives of Russian Rodnoverie. London and New York: Routledge. ISBN 9781472460271.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Aitamurto, Kaarina; Gaidukov, Alexey (2013). "Russian Rodnoverie: Six Portraits of a Movement". In Kaarina Aitamurto; Scott Simpson (eds.). Modern Pagan and Native Faith Movements in Central and Eastern Europe. Durham: Acumen. pp. 146–163. ISBN 9781844656622.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Črnič, Aleš (2013). "Neopaganism in Slovenia". In Kaarina Aitamurto; Scott Simpson (eds.). Modern Pagan and Native Faith Movements in Central and Eastern Europe. Durham: Acumen. pp. 182–194. ISBN 9781844656622.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Dostálová, Anna-Marie (2013). "Czech Neopagan Movements and Leaders". In Kaarina Aitamurto; Scott Simpson (eds.). Modern Pagan and Native Faith Movements in Central and Eastern Europe. Durham: Acumen. pp. 164–181. ISBN 9781844656622.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Dulov, Vladimir (2013). "Bulgarian Society and Diversity of Pagan and Neopagan Themes". In Kaarina Aitamurto; Scott Simpson (eds.). Modern Pagan and Native Faith Movements in Central and Eastern Europe. Durham: Acumen. pp. 195–212. ISBN 9781844656622.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Dynda, Jiří (2014). "The Three-Headed One at the Crossroad: A Comparative Study of the Slavic God Triglav" (PDF). Studia mythologica Slavica. Vol. 17. Institute of Slovenian Ethnology. pp. 57–82. ISSN 1408-6271. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 July 2017.

{{cite news}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Gaidukov, Alexey (2013). "The Russian-Language Internet and Rodnoverie". In Kaarina Aitamurto; Scott Simpson (eds.). Modern Pagan and Native Faith Movements in Central and Eastern Europe. Durham: Acumen. pp. 315–332. ISBN 9781844656622.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Gajda, Agnieszka (2013). "Romanticism and the Rise of Neopaganism in Nineteenth-Century Central and Eastern Europe: The Polish Case". In Kaarina Aitamurto; Scott Simpson (eds.). Modern Pagan and Native Faith Movements in Central and Eastern Europe. Durham: Acumen. pp. 44–61. ISBN 9781844656622.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Ivakhiv, Adrian (2005a). "In Search of Deeper Identities: Neopaganism and "Native Faith" in Contemporary Ukraine". Nova Religio: The Journal of Alternative and Emergent Religions. Vol. 8, no. 3. pp. 7–38. JSTOR 10.1525/nr.2005.8.3.7.

{{cite news}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ——— (2005b). "Nature and Ethnicity in East European Paganism: An Environmental Ethic of the Religious Right?". The Pomegranate: The International Journal of Pagan Studies. Vol. 7, no. 2. pp. 194–225.

{{cite news}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ——— (2005c). "The Revival of Ukrainian Native Faith". In Michael F. Strmiska (ed.). Modern Paganism in World Cultures: Comparative Perspectives. Santa Barbara: ABC-Clio. pp. 209–239. ISBN 9781851096084.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Ivanits, Linda J. (1989). Russian Folk Belief. M. E. Sharpe. ISBN 9780765630889.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Laruelle, Marlene (2008). "Alternative Identity, Alternative Religion? Neo-Paganism and the Aryan Myth in Contemporary Russia". Nations and Nationalism. Vol. 14, no. 2. pp. 283–301.

{{cite news}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Laruelle, Marlene. "The Rodnoverie Movement: The Search For Pre-Christian Ancestry And The Occult" // The New Age of Russia. Occult and Esoteric Dimensions / Ed. Menzel B., Hagemeister M., Glatzer Rosenthal B. – Munich, 2012. – P. 293–310.

- Leeming, David (2005). The Oxford Companion to World Mythology. Sydney: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780190288884.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Lesiv, Mariya (2009). "Glory to Dazhboh (Sun-god) or to All Native Gods?: Monotheism and Polytheism in Contemporary Ukrainian Paganism". The Pomegranate: The International Journal of Pagan Studies. Vol. 11, no. 2. doi:10.1558/pome.v11i2.197.

{{cite news}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ——— (2013a). The Return of Ancestral Gods: Modern Ukrainian Paganism as an Alternative Vision for a Nation. Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen's University Press. ISBN 9780773542624.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ——— (2013b). "Ukrainian Paganism and Syncretism: "This Is Indeed Ours!"". In Kaarina Aitamurto; Scott Simpson (eds.). Modern Pagan and Native Faith Movements in Central and Eastern Europe. Durham: Acumen. pp. 128–145. ISBN 9781844656622.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ——— (2017). "Blood Brothers or Blood Enemies: Ukrainian Pagans' Beliefs and Responses to the Ukraine-Russia Crisis". In Kathryn Rountree (ed.). Cosmopolitanism, Nationalism, and Modern Paganism. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 133–156. ISBN 9781137570406.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Mathieu-Colas, Michel (2017). "Dieux slaves et baltes" (PDF). Dictionnaire des noms des divinités. France: Archive ouverte des Sciences de l'Homme et de la Société, Centre national de la recherche scientifique. Retrieved 24 May 2017.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Pilkington, Hilary; Popov, Anton (2009). "Understanding Neo-paganism in Russia: Religion? Ideology? Philosophy? Fantasy?". In George McKay (ed.). Subcultures and New Religious Movements in Russia and East-Central Europe. Peter Lang. pp. 253–304. ISBN 9783039119219.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Popov, Igor (2016). Справочник всех религиозных течений и объединений в России [The Reference Book on All Religious Branches and Communities in Russia] (in الروسية).

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Potrzebowski, Stanisław (2016). Słowiański ruch Zadruga [Slavic movement Zadruga] (in البولندية). Wrocław: Wydawnictwo Triglav. ISBN 9788362586967.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Pranskevičiūtė, Rasa (2015). "The "Back to Nature" Worldview in Nature-based Spirituality Movements: The Case of the Anastasians". In James R. Lewis; Inga Bårdsen Tøllefsen (eds.). Handbook of Nordic New Religions. Leiden: Brill. pp. 441–456. ISBN 9789004292468.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Rabotkina, S. (2013). "Світоглядні та обрядові особливості сучасного українського неоязичництва". Вісник Дніпропетровського університету. Філософія. Соціологія. Політологія. Vol. 4, no. 23. pp. 237–244.

{{cite news}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Radulovic, Nemanja (2017). "From Folklore to Esotericism and Back: Neo-Paganism in Serbia". The Pomegranate: The International Journal of Pagan Studies. 19 (1): 47–76. doi:10.1558/pome.30374.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Rock, Stella (2007). Popular Religion in Russia: 'Double Belief' and the Making of an Academic Myth. Routledge. ISBN 9781134369782.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Rountree, Kathryn, ed. (2015). Contemporary Pagan and Native Faith Movements in Europe: Colonialist and Nationalist Impulses. Berghahn Books. ISBN 9781782386476.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Rudy, Stephen (1985). Contributions to Comparative Mythology: Studies in Linguistics and Philology, 1972–1982. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 9783110855463.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Shizhenskii, Roman; Aitamurto, Kaarina (2017). "Multiple Nationalisms and Patriotisms among Russian Rodnovers". In Kathryn Rountree (ed.). Cosmopolitanism, Nationalism, and Modern Paganism. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 109–132. ISBN 9781137570406.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Shnirelman, Victor A. (1998). Russian Neo-pagan Myths and Antisemitism. Analysis of Current Trends in Antisemitism, Acta no. 13. The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, The Vidal Sassoon International Center for the Study of Antisemitism.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ——— (2000). "Perun, Svarog and Others: Russian Neo-Paganism in Search of Itself". The Cambridge Journal of Anthropology. Vol. 21, no. 3. pp. 18–36.

{{cite news}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ——— (2002). ""Christians! Go home": A Revival of Neo-Paganism between the Baltic Sea and Transcaucasia (An Overview)". Journal of Contemporary Religion. Vol. 17, no. 2. pp. 197–211. doi:10.1080/13537900220125181.

{{cite news}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ——— (2007). "Ancestral Wisdom and Ethnic Nationalism: A View from Eastern Europe". The Pomegranate: The International Journal of Pagan Studies. Vol. 9, no. 1. pp. 41–61. doi:10.1558/pome.v9i1.41.

{{cite news}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ——— (2012). "Русское Родноверие: Неоязычество и Национализм в Современной России" [Russian native faith: neopaganism and nationalism in modern Russia]. Russian Journal of Communication. Vol. 5, no. 3. pp. 316–318. doi:10.1080/19409419.2013.825223.

{{cite news}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ——— (2013). "Russian Neopaganism: From Ethnic Religion to Racial Violence". In Kaarina Aitamurto; Scott Simpson (eds.). Modern Pagan and Native Faith Movements in Central and Eastern Europe. Durham: Acumen. pp. 62–71. ISBN 9781844656622.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ——— (2015). "Perun vs Jesus Christ: Communism and the emergence of Neo-paganism in the USSR". In Ngo, T.; Quijada, J. (eds.). Atheist Secularism and its Discontents. A Comparative Study of Religion and Communism in Eurasia. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 173–189. ISBN 9781137438386.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ——— (2017). "Obsessed with Culture: The Cultural Impetus of Russian Neo-Pagans". In Kathryn Rountree (ed.). Cosmopolitanism, Nationalism, and Modern Paganism. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 87–108. ISBN 9781137570406.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Simpson, Scott (2013). "Polish Rodzimowierstwo: Strategies for (Re)constructing a Movement". In Kaarina Aitamurto; Scott Simpson (eds.). Modern Pagan and Native Faith Movements in Central and Eastern Europe. Durham: Acumen. pp. 112–127. ISBN 9781844656622.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ——— (2017). "Only Slavic Gods: Nativeness in Polish Rodzimowierstwo". In Kathryn Rountree (ed.). Cosmopolitanism, Nationalism, and Modern Paganism. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 65–86. ISBN 9781137570406.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Simpson, Scott; Filip, Mariusz (2013). "Selected Words for Modern Pagan and Native Faith Movements in Central and Eastern Europe". In Kaarina Aitamurto; Scott Simpson (eds.). Modern Pagan and Native Faith Movements in Central and Eastern Europe. Durham: Acumen. pp. 27–43. ISBN 9781844656622.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Skrylnikov, Pavel (20 July 2016). "The Church Against Neo-Paganism". Intersection. Archived from the original on 7 July 2017.

{{cite news}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Strutyński, Maciej (2013). "The Ideology of Jan Stachniuk and the Power of Creation". In Kaarina Aitamurto; Scott Simpson (eds.). Modern Pagan and Native Faith Movements in Central and Eastern Europe. Durham: Acumen. pp. 283–397. ISBN 9781844656622.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Witulski, Maciej (2013). ""Imported" Paganisms in Poland in the Twenty-First Century: A Sketch of the Developing Landscape". In Kaarina Aitamurto; Scott Simpson (eds.). Modern Pagan and Native Faith Movements in Central and Eastern Europe. Durham: Acumen. pp. 298–314. ISBN 9781844656622.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

المصادر الرئيسية

- Petrović, Milan (2013). "Qualification of Slavic Rodnovery in scientific literature — neopaganism or ethnic religion" (PDF). Serbia: Svevlad Association of the Ecological and Ethnological Cultural Centre "Sfera". Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 July 2017.

{{cite news}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Articles containing بلاروسية-language text

- Articles containing بلغارية-language text

- Lang and lang-xx template errors

- Articles containing مقدونية-language text

- Articles containing تشيكية-language text

- Pages using Lang-xx templates

- Articles containing كرواتية-language text

- Articles containing پولندية-language text

- Articles containing روسية-language text

- Articles containing سلوڤاكية-language text

- Articles containing Slovene-language text

- Articles containing صربية-language text

- Articles containing أوكرانية-language text

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- CS1 الروسية-language sources (ru)

- CS1 البولندية-language sources (pl)

- التقاليد الوثنية المعاصرة

- الوثنية الجديدة في أوروپا

- الدين في بلاروس

- الدين في البوسنة والهرسك

- الدين في بلغاريا

- الدين في كرواتيا

- الدين في صربيا

- الدين في سلوڤاكيا

- الدين في سلوڤينيا

- الدين في جمهورية التشيك

- الدين في شمال مقدونيا

- الوثنية الجديدة السلاڤية