رياح

الرياح Wind هي هواء متحرّك عبر سطح الأرض. وقد تهب الرياح ببطء ولُطف شديدين، لدرجة تجعل من الصعوبة الإحساس بها، أو قد تهب بسرعة وعُنف كبيرين لدرجة تجعلها تدمر المباني، وتقتلع الأشجار الكبيرة من جذورها. والرياح القوية يمكنها أن تضرب أمواج المحيط العاتية، التي من شأنها أن تحطم السفن، وأن تغمر الأرض. وبإمكان الرياح إزالة التربة من الأراضي الزراعية، ومن ثم تتوقف المحاصيل عن النمو. وتستطيع ذرات التربة الناعمة، التي تحملها الرياح أن تُبلي الصخر، وتغير ملامح الأرض.

الرياح أيضاً جزء من الطقس، فاليوم الحار الرطب قد يتحول فجأة إلى بارد، إذا ما هبّت الرياح من منطقة باردة. والسحب المُحَمَّلة بالمطر والبرق قد تتكون حيث يلتقي الهواء البارد بالهواء الحار الرطب. وقد تدفع رياح أخرى السحب بعيدًا، وتسمح للشمس بأن تدفئ الأرض مرة أخرى. ويمكن للرياح أن تحمل العاصفة الهوجاء إلى مسافات بعيدة.

تُسمى الرياح وفقًا للاتجاه الذي تهب منه. فعلى سبيل المثال تهب الرياح الشرقية من الشرق إلى الغرب، والرياح الشمالية من الشمال إلى الجنوب.

أسباب هبوب الرياح

تحدث الرياح نتيجة التسخين غير المتساوي للغلاف الجوي ، عن طريق الطاقة المنبعثة من الشمس. تُسخِّن الشمس سطح الأرض بطريقة غير متساوية، فالهواء الذى يعلو المناطق الحارة يتمدد ويرتفع ، ويحل محله هواء من المناطق الأبرد. وتسمى هذه العملية دورة. فالدورة فوق الأرض بكاملها تسمى الدورة العامة، بينما تسمى الدورات النسبية الصغرى والتي يمكن أن تتسبب في حدوث تغيرات في الرياح يومًا بعد يوم، الدورات النسبية الشاملة للرياح. أما الرياح التي من الممكن أن تحدث في مكان واحد فقط، فإنها تُسمّى الرِّياح المحليَّة.

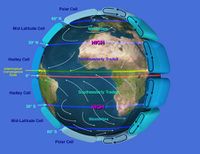

الدورة العامة للهواء حول الأرض

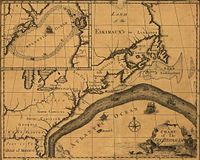

وتحدث فوق قطاعات كبيرة من سطح الأرض ، وتُسمّى هذه الرياح الرياح السائدة. وتتنوع هذه الرياح باختلاف خط العرض. فبالقرب من خط الاستواء ، يرتفع الهواء الساخن إلى مايقرب من 18,000م. وينتج عن الهواء المتحرك على سطح الأرض ، ليحل محل الهواء المرتفع، نطاقان من الرياح السائدة. ويقع هذان النطاقان بين خط الاستواء وخطيّ عرض 30° شمالاً وجنوباً. وتُسمّى الرياح في هذه المناطق الرياح التجارية. وسبب هذه التسمية أن التجار اعتمدوا عليها ذات مرة في إبحار السفن التجارية.

ولا تهب الرياح التجارية مباشرة نحو خط الاستواء ، بل تهب ـ نوعًا ما ـ من الشرق إلى الغرب. والجزء الذي يتجه نحو الغرب من حركة الرياح التجارية يحدث بسبب دوران الأرض حول محورها. فكل من الأرض والهواء حولها يدوران نحو الشرق معًا، وكل نقطة على سطح الأرض تتحرك حول دائرة كاملة كل 24 ساعة. أما النقاط القريبة من خط الاستواء، فإنها تتحرك حول دوائر أكبر من النقاط القريبة من خطي العرض 30° شمالاً وجنوبًا. ويرجع السبب في ذلك إلى أن الأرض تكون أكبر عند خط الاستواء، ولذا فالنقاط القريبة من خط الاستواء تتحرك بدرجة أسرع.

وعندما يتحرك الهواء نحو خط الاستواء، فإنه يصل إلى نقاط سريعة الحركة على سطح الأرض. وحيث إن هذه النقاط تتحرك صوب الشرق بدرجة أسرع من حركة الهواء، فإن المرء الذي يقف على الأرض يشعر برياح ما تهب ضده صوب الغرب.

ولاتوجد رياح سائدة قريبًا من خط الاستواء، وعلى بُعد يبلغ مداه ما يقرب من 1,100كم على كل جانب من خط الاستواء، لأن الهواء هناك يرتفع إلى أعلى بدلاً من تحركه عبر الأرض. ويُطلق على هذا النطـاق الهادئ منطقة الركود الاستوائي. وغالبًا ما تتقارب الرياح التجارية في منطقة ضيقة يطلق عليها منطقة التقارب بين المدارية.

ويعود بعض الهواء ـ الذي يرتفع عند خط الاستواء ـ إلى سطح الأرض بين خطي عرض 30° شمالاً وجنوبًا من خط الاستواء. وأما الهواء الذي يتحرك إلى أسفل في تلك المنطقة فلا تنتج عنه أية رياح. ويطلق على هذه المناطق عروض الخيل. ويُقال إن السبب في هذه التسمية يرجع إلى أن عددًا كبيرًا من الخيول قد نَفَقَتْ على ظهر السفن التي توقفت عن الحركة في تلك البقعة، بسبب النقص الشديد في الرياح.

وهناك نوعان من الرياح السائدة ينتجان من الدورة الهوائية العامة. فالرياح الغربية السائدة. تهب ـ نوعًا ما ـ من الغرب إلى الشرق في نطاق يقع بين خطي عرض 30°، 60° شمالاً وجنوبًا من خط الاستواء. وتنشأ هذه الرياح نتيجة لهبوب الهواء بعيدًا عن خط الاستواء إلى مناطق بطيئة الحركة بالقرب من القطبين. وتحمل هذه الرياح الغربية السائدة خصائصها المناخية في اتجاه الشرق عبر جنوبي أستراليا ونيوزيلندا. أما الرياح القطبية الشرقية فإنها تهب ـ نوعًا ما ـ من الشرق إلى الغرب، في نطاق يقع بين القطبين، وبين خطي عرض 60° شمالاً وجنوبًا. أمَّا فيما يخص الهواء على سطح الأرض، والمتحرك بعيدًا عن القطبين، فإنه يتحرك في اتجاه الغرب عبر نقاط أسرع في الحركة باتجاه خط الاستواء.

الدورات النسبية الشاملة للرياح

هي حركات الهواء حول مناطق صغيرة ذات ضغط مرتفع وضغط منخفض في الغلاف الجوي. وتتكون هذه المناطق في نطاق الدورة العامة الأكبر، ويتدفق الهواء نحو المناطق منخفضة الضغط، وتُسمّى مناطق الضغط الجوي المنخفض أو الأعاصير. ويتدفق الهواء من مناطق الضغط المرتفع والتي تُسمى مناطق الضغط الجوي المرتفع أو الأعاصير المضادة. وبنظرة عامة نجد أن الرياح تتحرك باتجاه عقارب الساعة حول منطقة الضغط المرتفع وعكس اتجاه عقارب الساعة حول منطقة الضغط المنخفض في نصف الكرة الشمالي. وتنعكس هذه الاتجاهات في نصف الكرة الجنوبي.

وتتحرك كل من مناطق الضغط الجوي المرتفع والضغط الجوي المنخفض ـ بشكل عام ـ مع الرياح السائدة. وعندما تمر ببقعة معينة على سطح الأرض يتغير اتجاه الرياح. فمنطقة الضغط الجوي المنخفض المتحركة في اتجاه الشرق عبر شيكاغو مثلاً، ينتج عنها رياح، من شأنها أن تندفع من الجنوب الشرقي إلى الشمال الغربي.

أنواع الرياح

الرياح المحلية

وتنشأ هذه الرياح فقط في مناطق معينة ومحدودة المساحة على سطح الأرض. والرياح التي تنتج عن تسخين الأرض أثناء الصيف وبرودتها أثناء الشتاء تُسمى الرياح الموسمية. وهي تهب من المحيط خلال الصيف وصوب المحيط أثناء الشتاء. وتتحكم الرياح الموسمية في مناخ قارة آسيا، وينتج عنها فصول الصيف الحارة، وفصول الشتاء الباردة. أما الرياح المحلية الدافئة الجافة والتي تهب على أحد جوانب الجبال، فتسمى رياح الشينوك في غربي الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية.وتسمى هذه الرياح نفسها في قارة أوروبا رياح الفونة الدافئة الجافة. ومن الرياح المحلية رياح الهرمتان ، ورياح السيروكو ، و رياح السموم، و الهبوب ، و الخماسين.

الرياح الدائمة

وهي رياح تـهب باستمرار وانتظام طوال السنة وتنحصر في طبقات الجو السفلى، وتسمى عادة بأسماء الجهات الأصلية أو الفرعية التي تهب منها وتشمل الرياح الدائمة , الرياح التجارية , الرياح العكسية والرياح القطبية.

الرياح الموسمية

تـهب الرياح الموسمية في فصول معينة من السنة، وسبب هبوبها هو أنه في فصل الصيف تكون الجهات الوسطى للقارات شديدة الحرارة لبعدها عن تأثير المحيطات فيسخن الهواء بها كثيرًا ويخف وترتفع، ويحل محله رياح رطبة آتية من المناطق المرتفعة الضغط من البحار المجاورة فتسبب سقوط أمطار الغزيرة بإذن الله تعالى وفِى فصل الشتاء ينعكس الحال وتصبح الجهات الداخلية بالقارات أبرد من جو البحار المحيطة بها، ولذا تهب الرياح من وسط القارة إلى المحيطات المجاورة وتكون جافة باردة، وأكثر ما تهب هذه الرياح الموسمية بصورة منتظمة على جهات آسيا الجنوبية الشرقية وأواسط إفريقيا والحبشة وشمال أُستراليا وجنوب غرب الجزيرة العربية.

قياس الرياح

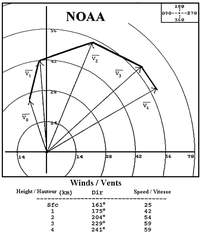

تتميز الرياح بسمتين هما: سرعتها واتجاهها. ويستعمل كلاهما في وصف الطقس ، والتنبؤ به.

سرعة الرياح

يمكن قياس سرعة الرياح عن طريق جهاز يسمى المرياح. كما تُستعمل في الوقت الحاضر عدة أنواع من المرياح. ومن أكثر هذه الأنواع شيوعًا على الإطلاق ذلك النوع الذي يتكون من ثلاثة أو أربعة أكواب ملتصقة بقضبان مثبتة على عامود دوار. وتدير هذه القضبانُ العامودَ عندما تهب الرياح ويمكن الإشارة إلى سرعة الرياح عن طريق العامود الدوار.

اتجاه الرياح

يقاس اتجاه الرياح عن طريق جهاز يسمى دوارة الرياح. ويتكون هذا الجهاز من ذراع مرتبطة بعامود يدور على محور مُثبت في أحد طرفيها. وعندما تهب الرياح في مواجهة الذراع يدور العامود حتى يمكن أن تصطف الذراع في اتجاه الرياح. ويمكن الاستدلال على اتجاه الرياح عن طريق سهم ملحق بالذراع أو عن طريق مؤشر كهربائي تتحكم فيه من بُعد دوّارة الرياح.

وغالبًا ما يشار إلى اتجاهات الرياح بوساطة استعمال 360° موضحّة على دائرة. ويمكن الإشارة من هذه الدائرة إلى اتجاه الشمال، بدرجة الصفر، وتهب الرياح الشرقية من درجة 90°، والرياح الجنوبية من 180°، والغربية من درجة 270°. وغالباً ماتختلف الرياح في السرعة والاتجاه عند الارتفاعات المتعددة. فعلى سبيل المثال يلاحظ أن الدخان المنبعث من فوهة مدخنة قد يأخذ اتجاه الشمال، بينما تتجه السحب الأعلى في السماء صوب الشرق.

وتقاس الرياح التي تهب عالية فوق سطح الأرض بإطلاق بالونات مملوءة بغاز الهيليوم، حيث يتحرك البالون بسرعة الرياح نفسها. وتقاس حركة البالون بالبصر أو عن طريق الرادار.

ويمكن تحديد ارتفاع البالون ، عن طريق ملاحظة الضغط الجوي، عندما يُقاس بجهاز قياس الضغط الجوي (البارومتر) المتصل بالبالون. ويمكن استخدام السحب التي تحدد حركاتها الأقمار الصناعية في تقدير اتجاهات الرياح فوق المحيطات، حيث يمكن إطلاق بضعة بالونات.

مقياس بوفورت لسرعة الرياح

وهو يتألف من سلسلة من الأعداد من صفر إلى 17. ويستعمل للإشارة إلى سرعات الرياح. وقد صَمَّمَ هذا المقياس في عام 1805م العميد البحري البريطاني فرانسيس بوفورت. وقد حدد بوفورت مفهوم هذه الأعداد، وبخاصة تأثير الرياح المتنوعة على السفن الشراعية. ففي نص نموذجي ـ ويقدم هنا على سبيل المثال ـ نُشر في عام 1874م، يقرر المقياس أن الرقم 2 يشير إلى رياح فسَّرها على النحو التالي: رياح يمكن لبارجة مُجَهَزَّة بكل معدات الإبحار، وفي حالة جيدة، ومفرَّغة ـ تماماً ـ أن تبحر في مياه هادئة وصافية بسرعة من عقدة إلى عقدتين. أمَّا الرياح التي يرمز إليها الرقم 12 فهي تلك الرياح التي لايمكن أن يَصمد أمام قوتها أي شراع. وفي الوقت الحاضر يمكن تحديد مفهوم مقياس بوفورت الخاص بسرعات الرياح، والتي يمكن قياسها في نطاق 10م فوق سطح الأرض، كما يُستعمل هذا المقياس أحياناً في تقدير سرعات الرياح.

الاستخدام في الأرصاد

| التصنيف العام للرياح | تصنيف الإعصار الإستوائي (سرعة الرياح 10-دقائق في المتوسط) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| مقياس بوفرت[1] | 10-minute sustained winds (عقدة) | المصطلح العام[2] | ش. المحيط الهندي IMD |

ج.غ. المحيط الهندي MF |

أستراليا BOM |

ج.غ. الهادي FMS |

ش.غ. الهادي JMA |

ش.غ. الهادي JTWC |

ش.ش. الهادي & ش. الأطلسي NHC & CPHC |

| 0 | <1 | هادئ | منفخض | اضطراب مداري | Tropical Low | منخفض مداري | منخفض مداري | منخفض مداري | منخفض مداري |

| 1 | 1-3 | Light air | |||||||

| 2 | 4-6 | Light breeze | |||||||

| 3 | 7-10 | Gentle breeze | |||||||

| 4 | 11-16 | Moderate breeze | |||||||

| 5 | 17-21 | Fresh breeze | |||||||

| 6 | 22-27 | Strong breeze | |||||||

| 7 | 28-29 | Moderate gale | Deep Depression | Tropical Depression | |||||

| 30-33 | |||||||||

| 8 | 34–40 | Fresh gale | Cyclonic Storm | Moderate Tropical Storm | Tropical Cyclone (1) | Tropical Cyclone (1) | Tropical Storm | Tropical Storm | Tropical Storm |

| 9 | 41-47 | Strong gale | |||||||

| 10 | 48–55 | Whole gale | Severe Cyclonic Storm | Severe Tropical Storm | Tropical Cyclone (2) | Tropical Cyclone (2) | Severe Tropical Storm | ||

| 11 | 56–63 | Storm | |||||||

| 12 | 64–72 | Hurricane | Very Severe Cyclonic Storm | Tropical Cyclone | Severe Tropical Cyclone (3) | Severe Tropical Cyclone (3) | Typhoon | Typhoon | Hurricane (1) |

| 13 | 73–85 | Hurricane (2) | |||||||

| 14 | 86–89 | Severe Tropical Cyclone (4) | Severe Tropical Cyclone (4) | Major Hurricane (3) | |||||

| 15 | 90–99 | Intense Tropical Cyclone | |||||||

| 16 | 100–106 | Major Hurricane (4) | |||||||

| 17 | 107-114 | Severe Tropical Cyclone (5) | Severe Tropical Cyclone (5) | ||||||

| 115–119 | Very Intense Tropical Cyclone | Super Typhoon | |||||||

| >120 | Super Cyclonic Storm | Major Hurricane (5) | |||||||

علم المناخ العالمي

الإستوائية

وهناك ستة نطاقات من هذه الرياح السائدة، ثلاثة في نصف الكرة الشمالي، وثلاثة في نصف الكرة الجنوبي. وتعرف بالرياح التجارية، و الرياح الغربية السائدة، والرياح القطبية الشرقية. ref>Ralph Stockman Tarr and Frank Morton McMurry (1909). "Advanced geography". W.W. Shannon, State Printing. p. 246. Retrieved 2009-04-15.</ref> الرياح التجارية بمثابة توجيه تدفق عن الأعاصير الاستوائية والتي تشكل ما يزيد على محيطات العالم]] .[3] Trade winds also steer African dust westward across the Atlantic ocean into the Caribbean sea, as well as portions of southeast North America.[4]وتهب الرياح الغربية السائدة إلى الشمال من الرياح التجارية في نصف الكرة الشمالي، وإلى الجنوب منها في نصف الكرة الجنوبي، وتبتعد عن خط الاستواء، وتبدو كأنها تهب من الغرب بسبب مفعول كريوليس، ويتحرك الطقس في منطقة الرياح الغربية السائدة من الغرب إلى الشرق. وهناك منطقة تسمى عروض الخيل، تفصل بين الرياح الغربية السائدة والرياح التجارية. لأن هذه الرياح ـ الغربية السائدة والتجارية ـ يتباعد كل منهما عن الآخر، لذا فإن الهواء في منطقة عروض الخيل يتحرك إلى أسفل لملء الفراغ. والرياح في عروض الخيل عادة خفيفة السرعة. وربما أطلق البحارة الأسبان هذا الاسم على هذه المنطقة لأنهم كانوا يجلبون الخيول إلى أمريكا في القرن السابع عشر الميلادي. وبسبب ضعف رياحها كانت سفن كثيرة من سفنهم الشراعية تتوقف في هذه المنطقة مدة طويلة، تنفد معها مياه الخيول فيضطرون إلى الإلقاء بها في مياه المحيط وتهب الرياح القطبية من القطبين الشمالي والجنوبي. فالهواء الموجود على القطبين يهبط إلى أسفل لأنه بارد جدًا، وعندما يصل إلى الأرض، ينتشر ويتحرك نحو خط الاستواء، مكوَّنًا الرياح القطبية الشرقية. ويجعل مفعول كريوليس هذه الرياح تبدو وكأنها تهب من الشرق. ويتحرك الطقس في منطقة الرياح القطبية من الشرق إلى الغرب. وتلتقي الرياح القطبية والرياح الغربية السائدة عند الجبهة القطبية وهي منطقة غائمة ممطرة. ويوجد فوق الجبهة القطبية حزام من التيارات الغربية النفاثة على بعد حوالي 10-15كم فوق الأرض، وقد تزيد سرعة هذه التيارات على 320 كم/ساعة.[5] عن التقدم في اتجاه القطب هو التعجيل بوضع قبالة الحرارة على ارتفاع منخفض فوق مناطق آسيا وأفريقيا ، وأمريكا الشمالية خلال شهر مايو إلى يوليو، وأكثر من مناطق أستراليا في ديسمبر .[6][7][8]

الرياح الغربية ووقعها

The Westerlies or the Prevailing Westerlies are the prevailing winds in the middle latitudes between 35 and 65 degrees latitude, blowing from the high pressure area in the horse latitudes towards the poles. These prevailing winds blow from the west to the east,[9] and steer extratropical cyclones in this general manner. The winds are predominantly from the southwest in the Northern Hemisphere and from the northwest in the Southern Hemisphere.[10] They are strongest in the winter when the pressure is lower over the poles, and weakest during the summer and when pressures are higher over the poles.[11]

Together with the trade winds, the westerlies enabled a round-trip trade route for sailing ships crossing the Atlantic and Pacific oceans, as the westerlies lead to the development of strong ocean currents on the western sides of oceans in both hemispheres through the process of western intensification.[12] These western ocean currents transport warm, tropical water polewards toward the polar regions. The westerlies can be particularly strong, especially in the southern hemisphere, where there is less land in the middle latitudes to cause the flow pattern to amplify, which slows the winds down. The strongest westerly winds in the middle latitudes are within a band known as the Roaring Forties, between 40 and 50 degrees latitude south of the equator.[13] The Westerlies play an important role in carrying the warm, equatorial waters and winds to the western coasts of continents,[14][15] especially in the southern hemisphere because of its vast oceanic expanse.

الرياح الشرقية القطبية

The polar easterlies, also known as Polar Hadley cells, are dry, cold prevailing winds that blow from the high-pressure areas of the polar highs at the north and south poles towards the low-pressure areas within the Westerlies at high latitudes. Unlike trade winds and the Westerlies, these prevailing winds blow from the east to the west, and are often weak and irregular.[16] Due to the low sun angle, cold air builds up and subsides at the pole creating surface high-pressure areas, forcing an equatorward outflow of air;[17] that outflow is deflected eastward by the Coriolis effect.

اعتبارات محلية

النسائم البحرية والبرية

الكتل الهوائية. هي كميات هائلة من الهواء تتكون فوق مناطق درجة حرارتها ثابتة إلى حد ما، فتكتسب درجة حرارة هذه المناطق. وقد تغطي الكتل الهوائية مساحة تصل إلى 13 مليون كم².

وتبعث الدورة العامة للغلاف الجوي بصفة مستمرة كتلاً هوائية من منطقة إلى أخرى، فتكتسب درجة حرارة المنطقة التي تتحرك فوقها، لكن ذلك يتم ببطء شديد بسبب كبر حجمها. وتؤثر الكتلة الهوائية على طقس المنطقة إلى أن تتمكن هذه المنطقة من تغيير تلك الكتلة الهوائية تغييرًا جوهريًا. وهناك أربعة أنواع رئيسية من الكتل الهوائية :1ـ قطبية قارية، 2ـ مدارية قارية، 3ـ قطبية بحرية، 4ـ مدارية بحرية. والكتل الهوائية القطبية القارية باردة ـ جافة وتتشكل على مناطق مثل جرينلاند، وشمالي كندا، والأجزاء المتطرفة شمالي آسيا وأوروبا. أما الكتل الهوائية المدارية القارية فهي حارة جافة، وتتشكل على مناطق مثل شمالي إفريقيا وشمالي أستراليا. والكتل الهوائية القطبية البحرية رطبة معتدلة البرودة، وتتشكل على الأجزاء الشمالية والجنوبية من المحيطين الهادئ والأطلسي، أما الكتل الهوائية المدارية البحرية فرطبة دافئة، وتتشكل على أواسط المحيطين الهادئ والأطلسي وعلى المحيط الهندي.[18] The sea therefore has a greater capacity for absorbing heat than the land, so the surface of the sea warms up more slowly than the land's surface. As the temperature of the surface of the land rises, the land heats the air above it. The warm air is less dense and so it rises. This rising air over the land lowers the sea level pressure by about 0.2%. The cooler air above the sea, now with relatively higher sea level pressure, flows towards the land into the lower pressure, creating a cooler breeze near the coast.

The strength of the sea breeze is directly proportional to the temperature difference between the land mass and the sea. If an offshore wind of 8 عقدة (15 km/h) exists, the sea breeze is not likely to develop. At night, the land cools off more quickly than the ocean due to differences in their specific heat values, which forces the daytime sea breeze to dissipate. If the temperature onshore cools below the temperature offshore, the pressure over the water will be lower than that of the land, establishing a land breeze, as long as an onshore wind is not strong enough to oppose it.[19]

بالقرب من الجبال

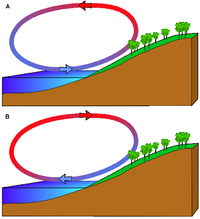

Over elevated surfaces, heating of the ground exceeds the heating of the surrounding air at the same altitude above sea level, creating an associated thermal low over the terrain and enhancing any thermal lows that would have otherwise existed,[20][21] and changing the wind circulation of the region. In areas where there is rugged topography that significantly interrupts the environmental wind flow, the wind circulation between mountains and valleys is the most important contributor to the prevailing winds. Hills and valleys substantially distort the airflow by increasing friction between the atmosphere and landmass by acting as a physical block to the flow, deflecting the wind parallel to the range just upstream of the topography, which is known as a barrier jet. This barrier jet can increase the low level wind by 45 percent.[22] Wind direction also changes due to the contour of the land.[23]

If there is a pass in the mountain range, winds will rush through the pass with considerable speed due to the Bernoulli principle that describes an inverse relationship between speed and pressure. The airflow can remain turbulent and erratic for some distance downwind into the flatter countryside. These conditions are dangerous to ascending and descending airplanes.[23] Relatively cool winds accelerating through mountain gaps have been given regional names. In Central America, examples include the Papagayo wind, the Panama wind, and the Tehuano wind. In Europe, similar winds are known as the Bora, Tramontane, and Mistral. When these winds blow over open waters, they increasing mixing of the upper layers of the ocean that elevates cool, nutrient rich waters to the surface, which leads to increased marine life.[24]

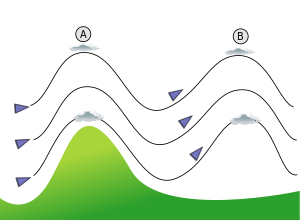

In mountainous areas, local distortion of the airflow becomes severe. Jagged terrain combines to produce unpredictable flow patterns and turbulence, such as rotors, which can be topped by lenticular clouds. Strong updrafts, downdrafts and eddies develop as the air flows over hills and down valleys. Orographic precipitation occurs on the windward side of mountains and is caused by the rising air motion of a large-scale flow of moist air across the mountain ridge, also known as upslope flow, resulting in adiabatic cooling and condensation. In mountainous parts of the world subjected to relatively consistent winds (for example, the trade winds), a more moist climate usually prevails on the windward side of a mountain than on the leeward or downwind side. Moisture is removed by orographic lift, leaving drier air on the descending and generally warming, leeward side where a rain shadow is observed.[25] Winds that flow over mountains down into lower elevations are known as downslope winds. These winds are warm and dry. In Europe downwind of the Alps, they are known as foehn. In Poland, an example is the halny wiatr. In Argentina, the local name for downsloped winds is zonda. In Java, the local name for such winds is koembang. In New Zealand, they are known as the Nor'west arch, and are accompanied by the cloud formation they are named after that has inspired artwork over the years.[26] In the Great Plains of the United States, the winds are known as a chinook. In California, downsloped winds are funneled through mountain passes, which intensify their effect, and examples into Santa Ana and Sundowner winds. Wind speeds during downslope wind effect can exceed 160 كيلومترات في الساعة (99 mph).[27]

القص

Wind shear, sometimes referred to as windshear or wind gradient, is a difference in wind speed and direction over a relatively short distance in the Earth's atmosphere.[28] Wind shear can be broken down into vertical and horizontal components, with horizontal wind shear seen across weather fronts and near the coast,[29] and vertical shear typically near the surface,[30] though also at higher levels in the atmosphere near upper level jets and frontal zones aloft.[31]

Wind shear itself is a microscale meteorological phenomenon occurring over a very small distance, but it can be associated with mesoscale or synoptic scale weather features such as squall lines and cold fronts. It is commonly observed near microbursts and downbursts caused by thunderstorms,[32] weather fronts, areas of locally higher low level winds referred to as low level jets, near mountains,[33] radiation inversions that occur due to clear skies and calm winds, buildings,[34] wind turbines,[35] and sailboats.[36] Wind shear has a significant effect during take-off and landing of aircraft due to their effects on control of the aircraft,[37] and was a significant cause of aircraft accidents involving large loss of life within the الولايات المتحدة.[32]

Sound movement through the atmosphere is affected by wind shear, which can bend the wave front, causing sounds to be heard where they normally would not, or vice versa.[38] Strong vertical wind shear within the troposphere also inhibits tropical cyclone development,[39] but helps to organize individual thunderstorms into living longer life cycles that can then produce severe weather.[40] The thermal wind concept explains how differences in wind speed with height are dependent on horizontal temperature differences, and explains the existence of the jet stream.[41]

في المجتمع

التاريخ

As a natural force, the wind was often personified as one or more wind gods or as an expression of the supernatural in many cultures. Vayu is the Hindu God of Wind.[42][43] The Greek wind gods include Boreas, Notus, Eurus, and Zephyrus.[43] Aeolus, in varying interpretations the ruler or keeper of the four winds, has also been described as Astraeus, the god of dusk who fathered the four winds with Eos, goddess of dawn. The Ancient Greeks also observed the seasonal change of the winds, as evidenced by the Tower of the Winds in Athens.[44][43] Venti are the Roman gods of the winds.[45] Fūjin, the Japanese wind god and is one of the eldest Shinto gods. According to legend, he was present at the creation of the world and first let the winds out of his bag to clear the world of mist.[46] In Norse mythology, Njord is the god of the wind.[43] There are also four dvärgar (Norse dwarves), named Norðri, Suðri, Austri and Vestri, and probably the four stags of Yggdrasil, personify the four winds, and parallel the four Greek wind gods.[47] Stribog is the name of the Slavic god of winds, sky and air. He is said to be the ancestor (grandfather) of the winds of the eight directions.[48][43]

Kamikaze (神風) is a Japanese word, usually translated as divine wind, believed to be a gift from the gods. The term is first known to have been used as the name of a pair or series of typhoons that are said to have saved Japan from two Mongol fleets under Kublai Khan that attacked Japan in 1274 and again in 1281.[49] Protestant Wind is a name for the storm that deterred the Spanish Armada from an invasion of إنگلترة in 1588 where the wind played a pivotal role,[50] or the favorable winds that enabled William of Orange to invade England in 1688.[51] During Napoleon's Egyptian Campaign, the French soldiers had a hard time with the khamsin wind: when the storm appeared "as a blood-stint in the distant sky", the natives went to take cover, while the French "did not react until it was too late, then choked and fainted in the blinding, suffocating walls of dust."[52] During the North African Campaign of the الحرب العالمية الثانية, "allied and German troops were several times forced to halt in mid-battle because of sandstorms caused by khamsin ... Grains of sand whirled by the wind blinded the soldiers and created electrical disturbances that rendered compasses useless."[53]

المواصلات

There are many different types of sailing ships, but they all have certain basic things in common. Every sailing ship has a hull, rigging and at least one mast to hold up the sails that use the wind to power the ship.[54] Ocean journeys by sailing ship can take many months,[55] and a common hazard is becoming becalmed because of lack of wind,[56] or being blown off course by severe storms or winds that do not allow progress in the desired direction.[57] A severe storm could lead to shipwreck, and the loss of all hands.[58] Sailing ships can only carry a certain quantity of supplies in their hold, so they have to plan long voyages carefully to include appropriate provisions, including fresh water.[59]

While aircraft usually travel under an internal power source, tail winds affect groundspeed,[60] and in the case of hot air balloons and other lighter-than-air vehicles, wind may play a significant role in their movement and ground track.[61] In addition, the direction of wind plays a role in the takeoff and landing of fixed-wing aircraft and airfield runways are usually aligned to take the direction of wind into account. Of all factors affecting the direction of flight operations at an airport, wind direction is considered the primary governing factor. While taking off with a tailwind may be permissible under certain circumstances, it is generally considered the least desirable choice due to performance and safety considerations, with a headwind the desirable choice. A tailwind will increase takeoff distance and decrease climb gradient such that runway length and obstacle clearance may become limiting factors.[62] An airship, or dirigible, is a lighter-than-air aircraft that can be steered and propelled through the air using rudders and propellers or other thrust.[63] Unlike other aerodynamic aircraft such as fixed-wing aircraft and helicopters, which produce lift by moving a wing, or airfoil, through the air, aerostatic aircraft, such as airships and hot air balloons, stay aloft by filling a large cavity, such as a balloon, with a lifting gas.[64] The main types of airship are non-rigid (or blimps), semi-rigid and rigid. Blimps are small airships without internal skeletons. Semi-rigid airships are slightly larger and have some form of internal support such as a fixed keel. Rigid airships with full skeletons, such as the massive Zeppelin transoceanic models,[65] all but disappeared after several high-profile catastrophic accidents during the mid-20th century.[66]

الطاقة

Historically, the ancient Sinhalese of Anuradhapura and in other cities around Sri Lanka used the monsoon winds to power furnaces as early as 300 BCE.[67] The furnaces were constructed on the path of the monsoon winds to exploit the wind power, to bring the temperatures inside up to 1،200 °C (2،190 °F). An early historical reference to a rudimentary windmill was used to power an organ in the first century CE.[68] The first practical windmills were later built in Sistan, Afghanistan, from the 7th century CE. These were vertical-axle windmills, which had long vertical driveshafts with rectangle shaped blades.[69] Made of six to twelve sails covered in reed matting or cloth material, these windmills were used to grind corn and draw up water, and were used in the gristmilling and sugarcane industries.[70] Horizontal-axle windmills were later used extensively in Northwestern Europe to grind flour beginning in the 1180s, and many Dutch windmills still exist.[71]

Nowadays, a yardstick used to determine the best locations for wind energy development is referred to as Wind Power Density (WPD.) It is a calculation relating to the effective force of the wind at a particular location, frequently expressed in terms of the elevation above ground level over a period of time. It takes into account wind velocity and mass. Color coded maps are prepared for a particular area are described as, for example, "Mean Annual Power Density at 50 Meters." The results of the above calculation are included in an index developed by the National Renewable Energy Lab and referred to as "NREL CLASS." The larger the WPD calculation, the higher it is rated by class.[72] At the end of 2008, worldwide nameplate capacity of wind-powered generators was 120.8 gigawatts.[73] Although wind produces only about 1.5 percent of worldwide electricity use,[73] it is growing rapidly, having doubled in the three years between 2005 and 2008. In several countries it has achieved relatively high levels of penetration, accounting for approximately 19 percent of electricity production in Denmark, 10 percent in Spain and Portugal, and 7 percent in Germany and the Republic of Ireland in 2008. One study indicates that an entirely renewable energy supply based on 70 percent wind is attainable at today's power prices by linking wind farms with an HVDC supergrid.[74]

الترفيه

Wind figures prominently in several popular sports, including recreational hang gliding, hot air ballooning, kite flying, kite landboarding, kite surfing, paragliding, sailing, and windsurfing. In gliding, wind gradients just above the surface affect the takeoff and landing phases of flight of a glider. Wind gradient can have a noticeable effect on ground launches, also known as winch launches or wire launches. If the wind gradient is significant or sudden, or both, and the pilot maintains the same pitch attitude, the indicated airspeed will increase, possibly exceeding the maximum ground launch tow speed. The pilot must adjust the airspeed to deal with the effect of the gradient.[75] When landing, wind shear is also a hazard, particularly when the winds are strong. As the glider descends through the wind gradient on final approach to landing, airspeed decreases while sink rate increases, and there is insufficient time to accelerate prior to ground contact. The pilot must anticipate the wind gradient and use a higher approach speed to compensate for it.[76]

Role in the natural world

In arid climates, the main source of erosion is wind.[77] The general wind circulation moves small particulates such as dust across wide oceans thousands of kilometers downwind of their point of origin,[78], which is known as deflation. Westerly winds in the mid-latitudes of the planet drive the movement of ocean currents from west to east across the world's oceans. Wind has a very important role in aiding plants and other immobile organisms in dispersal of seeds, spores, pollen, etc. Although wind is not the primary form of seed dispersal in plants, it provides dispersal for a large percentage of the biomass of land plants.

النحر

Erosion can be the result of material movement by the wind. There are two main effects. First, wind causes small particles to be lifted and therefore moved to another region. This is called deflation. Second, these suspended particles may impact on solid objects causing erosion by abrasion (ecological succession). Wind erosion generally occurs in areas with little or no vegetation, often in areas where there is insufficient rainfall to support vegetation. An example is the formation of sand dunes, on a beach or in a desert.[79] Loess is a homogeneous, typically nonstratified, porous, friable, slightly coherent, often calcareous, fine-grained, silty, pale yellow or buff, windblown (aeolian) sediment.[80] It generally occurs as a widespread blanket deposit that covers areas of hundreds of square kilometers and tens of meters thick. Loess often stands in either steep or vertical faces.[81] Loess tends to develop into highly rich soils. Under appropriate climatic conditions, areas with loess are among the most agriculturally productive in the world.[82] Loess deposits are geologically unstable by nature, and will erode very readily. Therefore, windbreaks (such as big trees and bushes) are often planted by farmers to reduce the wind erosion of loess.[77]

Desert dust migration

During mid-summer (July), the westward-moving trade winds south of the northward-moving subtropical ridge expand northwestward from the Caribbean sea into southeastern North America. When dust from the Sahara moving around the southern periphery of the ridge within the belt of trade winds moves over land, rainfall is suppressed and the sky changes from a blue to a white appearance, which leads to an increase in red sunsets. Its presence negatively impacts air quality by adding to the count of airborne particulates.[4] Over 50 percent of the African dust that reaches the United States affects Florida.[83] Since 1970, dust outbreaks have worsened due to periods of drought in Africa. There is a large variability in the dust transport to the Caribbean and Florida from year to year.[84] Dust events have been linked to a decline in the health of coral reefs across the Caribbean and Florida, primarily since the 1970s.[85] Similar dust plumes originate in the Gobi desert, which combined with pollutants, spread large distances downwind, or eastward, into North America.[78]

There are local names for winds associated with sand and dust storms. The Calima carries dust on southeast winds into the Canary islands.[86] The Harmattan carries dust during the winter into the Gulf of Guinea.[87] The Sirocco brings dust from north Africa into southern Europe due to the movement of extratropical cyclones through the Mediterranean sea.[88] Spring storm systems moving across the eastern Mediteranean sea cause dust to carry across Egypt and the Arabian peninsula, which are locally known as Khamsin.[89] The Shamal is caused by cold fronts lifting dust into the atmosphere for days at a time across the Persian Gulf states.[90]

التأثير على النباتات

Wind dispersal of seeds, or anemochory, is one of the more primitive means of dispersal. Wind dispersal can take on one of two primary forms: seeds can float on the breeze or alternatively, they can flutter to the ground.[91] The classic examples of these dispersal mechanisms include dandelions (Taraxacum spp., Asteraceae), which have a feathery pappus attached to their seeds and can be dispersed long distances, and maples (Acer (genus) spp., Sapindaceae), which have winged seeds and flutter to the ground. An important constraint on wind dispersal is the need for abundant seed production to maximize the likelihood of a seed landing in a site suitable for germination. There are also strong evolutionary constraints on this dispersal mechanism. For instance, species in the Asteraceae on islands tended to have reduced dispersal capabilities (i.e., larger seed mass and smaller pappus) relative to the same species on the mainland.[92] Reliance upon wind dispersal is common among many weedy or ruderal species. Unusual mechanisms of wind dispersal include tumbleweeds. A related process to anemochory is anemophily, which is the process where pollen is distributed by wind. Large families of plants are pollinated in this manner, which is favored when individuals of the dominant plant species are spaced closely together.[93]

Wind also limits tree growth. On coasts and isolated mountains, the tree line is often much lower than in corresponding altitudes inland and in larger, more complex mountain systems, because strong winds reduce tree growth. High winds scour away thin soils through erosion,[94] as well as damage limbs and twigs. When high winds knock down or uproot trees, the process is known as windthrow. This is most likely on windward slopes of mountains, with severe cases generally occurring to tree stands that are 75 years or older.[95] Plant varieties near the coast, such as the Sitka spruce and sea grape,[96] are pruned back by wind and salt spray near the coastline.[97]

التأثير على الحيوانات

Cattle and sheep are prone to wind chill caused by a combination of wind and cold temperatures, when winds exceed 40 كيلومترات في الساعة (25 mph) that renders their hair and wool coverings ineffective.[98] Although penguins use both a layer of fat and feathers to help guard against coldness in both water and air, their flippers and feet are less immune to the cold. In the coldest climates such as Antarctica, emperor penguins use huddling behavior to survive the wind and cold, continuously alternating the members on the outside of the assembled group, which reduces heat loss by 50%.[99] Flying insects, a subset of arthropods, are swept along by the prevailing winds,[100] while birds follow their own course taking advantage of wind conditions, in order to either fly or glide.[101] As such, fine line patterns within weather radar imagery, associated with converging winds, are dominated by insect returns.[102] Bird migration, which tends to occur overnight within the lowest 7،000 أقدام (2،100 m) of the Earth's atmosphere, contaminates wind profiles gathered by weather radar, particularly the WSR-88D, by increasing the environmental wind returns by 15 عقدة (28 km/h) to 30 عقدة (56 km/h).[103]

Pikas use a wall of pebbles, known as a vole, to store dry plants and grasses for the winter in order to protect the food from being blown away.[104] Cockroaches use slight winds that precede the attacks of potential predators, such as toads, to survive their encounters. Their cerci are very sensitive to the wind, and help them survive half of their attacks.[105] Elk has a keen sense of smell that can detect potential upwind predators at a distance of 0.5 ميل (800 m).[106] Increases in wind above 15 كيلومترات في الساعة (9.3 mph) signals glaucous gulls to increase their foraging and aerial attacks on thick-billed murres.[107]

أضرار متعلقة

High winds are known to cause damage, depending upon their strength. Infrequent wind gusts can cause poorly-designed suspension bridges to sway. When wind gusts are at a similar frequency to the swaying of the bridge, the bridge can be destroyed easier, such as what occurred with the Tacoma Narrows Bridge in 1940.[108] Wind speeds as low as 23 عقدة (43 km/h) can lead to power outages due to tree branches disrupting the flow of energy through power lines.[109] While no species of tree is guaranteed to stand up to hurricane-force winds, those with shallow roots are more prone to uproot, and brittle trees such as eucalyptus, sea hibiscus, and avocado are more prone to damage.[110] Hurricane-force winds cause substantial damage to mobile homes, and begin to structurally damage homes with foundations. Winds of this strength due to downsloped winds off terrain have been known to shatter windows and sandblast paint from cars.[27] Once winds exceed 135 عقدة (250 km/h), homes completely collapse, and significant damage is done to larger buildings. Total destruction to man-made structures occurs when winds reach 175 عقدة (324 km/h). The Saffir-Simpson scale and Enhanced Fujita scale were designed to help estimate wind speed from the damage caused by high winds related to tropical cyclones and tornadoes, and vice versa.[111][112]

Wildfire intensity increases during daytime hours. For example, burn rates of smoldering logs are up to five times greater during the day due to lower humidity, increased temperatures, and increased wind speeds.[113] Sunlight warms the ground during the day and causes air currents to travel uphill, and downhill during the night as the land cools. Wildfires are fanned by these winds and often follow the air currents over hills and through valleys.[114] United States wildfire operations revolve around a 24-hour fire day that begins at 10:00 a.m. due to the predictable increase in intensity resulting from the daytime warmth.[115]

في الفضاء

The solar wind is quite different than a terrestrial wind, in that its origin is the sun, and it is composed of charged particles that have escaped the sun's atmosphere. Similar to the solar wind, the planetary wind is composed of light gases that escape planetary atmospheres. Over long periods of time, the planetary wind can radically change the composition of planetary atmospheres.

الكوكبية

The hydrodynamic wind within the upper portion of a planet's atmosphere allows light chemical elements such as Hydrogen to move up to the exobase, the lower limit of the exosphere, where the gases can then reach escape velocity, entering outer space without impacting other particles of gas. This type of gas loss from a planet into space is known as planetary wind.[116] Such a process over geologic time causes water-rich planets such as the Earth to evolve into planets such as Venus over billions of years.[117] Planets with hot lower atmospheres could result in humid upper atmospheres that accelerate the loss of hydrogen.[118]

الشمس

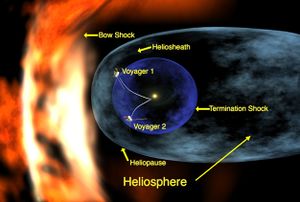

Rather than air, the solar wind is a stream of charged particles—a plasma—ejected from the upper atmosphere of the sun at a rate of 400 kilometres per second (890،000 mph). It consists mostly of electrons and protons with energies of about 1 keV. The stream of particles varies in temperature and speed with the passage of time. These particles are able to escape the sun's gravity, in part because of the high temperature of the corona,[119] but also because of high kinetic energy that particles gain through a process that is not well-understood. The solar wind creates the Heliosphere, a vast bubble in the interstellar medium surrounding the solar system.[120] Planets require large magnetic fields in order to reduce the ionization of their upper atmosphere by the solar wind.[118] Other phenomena include geomagnetic storms that can knock out power grids on Earth,[121] the aurorae such as the Northern Lights,[122] and the plasma tails of comets that always point away from the sun.[123]

على كواكب أخرى

Strong 300 كيلومترات في الساعة (190 mph) winds at Venus's cloud tops circle the planet every four to five earth days.[124] When the poles of Mars are exposed to sunlight after their winter, the frozen CO2 sublimes, creating significant winds that sweep off the poles as fast as 400 كيلومترات في الساعة (250 mph), which subsequently transports large amounts of dust and water vapor over its landscape.[125] On Jupiter, wind speeds of 100 أمتار في الثانية (220 mph) are common in zonal jet streams.[126] Saturn's winds are among the solar system's fastest. Cassini–Huygens data indicated peak easterly winds of 375 أمتار في الثانية (840 mph).[127] On Uranus, northern hemisphere wind speeds reach as high as 240 أمتار في الثانية (540 mph) near 50 degrees north latitude.[128][129][130] At the cloud tops of Neptune, prevailing winds range in speed from 400 أمتار في الثانية (890 mph) along the equator to 250 أمتار في الثانية (560 mph) at the poles.[131] At 70° S latitude on Neptune, a high-speed jet stream travels at a speed of 300 أمتار في الثانية (670 mph).[132]

انظر أيضا

المصادر

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةBeaufort - ^ Coastguard Southern Region (2009). "The Beaufort Wind Scale". Retrieved 2009-03-18.

- ^ Joint Typhoon Warning Center (2006). "3.3 JTWC Forecasting Philosophies" (PDF). United States Navy. Retrieved 2007-02-11.

- ^ أ ب Science Daily (1999-07-14). "African Dust Called A Major Factor Affecting Southeast U.S. Air Quality". Science Daily. Retrieved 2007-06-10. خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صالح؛ الاسم "pooraq" معرف أكثر من مرة بمحتويات مختلفة. - ^ Glossary of Meteorology. "Monsoon". American Meteorological Society. Retrieved 2008-03-14.

{{cite web}}: Text "date-2009" ignored (help) - ^ "Chapter-II Monsoon-2004: Onset, Advancement and Circulation Features" (PDF). National Centre for Medium Range Forecasting. 2004-10-23. Retrieved 2008-05-03.

- ^ "Monsoon". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 2000. Retrieved 2008-05-03.

- ^ Dr. Alex DeCaria (2007-10-02). "Lesson 4 – Seasonal-mean Wind Fields". Millersville Meteorology. Retrieved 2008-05-03.

- ^ Glossary of Meteorology (2009). "Westerlies". American Meteorological Society. Retrieved 2009-04-15.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةRalph - ^ Halldór Björnsson (2005). "Global circulation". Veðurstofu Íslands. Retrieved 2008-06-15.

- ^ National Environmental Satellite, Data, and Information Service (2009). "Investigating the Gulf Stream". North Carolina State University. Retrieved 2009-05-06.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Stuart Walker (1998). The sailor's wind. W. W. Norton & Company. p. 91. ISBN 0393045552, 9780393045550. Retrieved 2009-06-17.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help) - ^ "The North Atlantic Drift Current". The National Oceanographic Partnership Program. 2003. Retrieved 2008-09-10.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Polar Lows. Cambridge University Press. 2003. p. 68.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Glossary of Meteorology (2009). "Polar easterlies". American Meteorological Society. Retrieved 2009-04-15.

- ^ Michael E. Ritter (2008). "The Physical Environment: Global scale circulation". University of Wisconsin-Stevens Point. Retrieved 2009-04-15.

- ^ Dr. Steve Ackerman (1995). "Sea and Land Breezes". University of Wisconsin. Retrieved 2006-10-24.

- ^ JetStream: An Online School For Weather (2008). "The Sea Breeze". National Weather Service. Retrieved 2006-10-24.

- ^ National Weather Service Forecast Office in Tucson, Arizona (2008). "What is a monsoon?". National Weather Service Western Region Headquarters. Retrieved 2009-03-08.

- ^ Douglas G. Hahn and Syukuro Manabe (1975). "The Role of Mountains in the South Asian Monsoon Circulation". Journal of Atmospheric Sciences. 32 (8): 1515-1541. Retrieved 2009-03-08.

- ^ J. D. Doyle (1997). "The influence of mesoscale orography on a coastal jet and rainband". Monthly Weather Review. 125 (7): 1465-1488. ISSN 0027-0644. Retrieved 2008-12-25.

- ^ أ ب National Center for Atmospheric Research (2006). "T-REX: Catching the Sierra's waves and rotors". University Corporation for Atmospheric Research. Retrieved 2006-10-21.

- ^ Anthony Drake (2008-02-08). "The Papaguayo Wind". NASA Goddard Earth Sciences Data and Information Services Center. Retrieved 2009-06-16.

- ^ Dr. Michael Pidwirny (2008). "CHAPTER 8: Introduction to the Hydrosphere (e). Cloud Formation Processes". Physical Geography. Retrieved 2009-01-01.

- ^ Michael Dunn (2003). New Zealand Painting. Auckland University Press. p. 93. ISBN 9781869402976. Retrieved 2009-06-21.

- ^ أ ب Rene Munoz (2000-04-10). "Boulder's downslope winds". University Corporation for Atmospheric Research. Retrieved 2009-06-16.

- ^ D. C. Beaudette (1988). "FAA Advisory Circular Pilot Wind Shear Guide via the Internet Wayback Machine" (PDF). Federal Aviation Administration. Retrieved 2009-03-18.

- ^ David M. Roth (2006). "Unified Surface Analysis Manual" (PDF). Hydrometeorological Prediction Center. Retrieved 2006-10-22.

- ^ Glossary of Meteorology (2007). "E". American Meteorological Society. Retrieved 2007-06-03.

- ^ "Jet Streams in the UK". BBC. 2009. Retrieved 2009-06-20.

- ^ أ ب Cheryl W. Cleghorn (2004). "Making the Skies Safer From Windshear". NASA Langley Air Force Base. Retrieved 2006-10-22. خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صالح؛ الاسم "Cleghorn" معرف أكثر من مرة بمحتويات مختلفة. - ^ National Center for Atmospheric Research (Spring 2006). "T-REX: Catching the Sierra's waves and rotors". University Corporation for Atmospheric Research Quarterly. Retrieved 2009-06-21.

- ^ Hans M. Soekkha (1997). Aviation Safety. VSP. p. 229. ISBN 9789067642583. Retrieved 2009-06-21.

- ^ Robert Harrison (2001). Large Wind Turbines. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons. p. 30. ISBN 0471494569.

- ^ Ross Garrett (1996). The Symmetry of Sailing. Dobbs Ferry: Sheridan House. pp. 97–99. ISBN 1574090003.

- ^ Gail S. Langevin (2009). "Wind Shear". National Aeronautic and Space Administration. Retrieved 2007-10-09.

- ^ Rene N. Foss (June 1978). "Ground Plane Wind Shear Interaction on Acoustic Transmission". WA-RD 033.1. Washington State Department of Transportation. Retrieved on 2007-05-30.

- ^ University of Illinois (1999). "Hurricanes". Retrieved 2006-10-21.

- ^ University of Illinois (1999). "Vertical Wind Shear". Retrieved 2006-10-21.

- ^ Integrated Publishing (2007). "Unit 6—Lesson 1: Low-Level Wind Shear". Retrieved 2009-06-21.

- ^ Laura Gibbs, Ph.D (2007-10-16). "Vayu". Encyclopedia for Epics of Ancient India. Retrieved 2009-04-09.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج Michael Jordan (1993). Encyclopedia of Gods: Over 2, 500 Deities of the World. New York: Facts on File. pp. 5, 45, 80, 187–188, 243, 280, 295. ISBN 0-8160-2909-1.

- ^ Dr. Alena Trckova-Flamee, Ph.D (2002). "Gods of the Winds". Encyclopedia Mythica. Retrieved 2009-04-09.

- ^ Theoi Greek Mythology (2008). "Anemi: Greek Gods of the Winds". Aaron Atsma. Retrieved 2009-04-10.

- ^ John Boardman (1994). The Diffusion of Classical Art in Antiquity. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-03680-2.

- ^ Andy Orchard (1997). Dictionary of Norse Myth and Legend. Cassell. ISBN 9780304363858.

- ^ John McCannon (2002). "Stribog". Encyclopedia Mythica. Retrieved 2009-04-10.

- ^ History Detectives (2008). "Feature - Kamikaze Attacks". PBS. Retrieved 2009-03-21.

- ^ Colin Martin, Geoffrey Parker (1999). The Spanish Armada. Manchester University Press. pp. 144–181. ISBN 9781901341140. Retrieved 2009-06-20.

- ^ S. Lindgrén and J. Neumann (1985). Great Historical Events That Were Significantly Affected by the Weather: 7, “Protestant Wind”—“Popish Wind”: The Revolusion of 1688 in England. pp. 634–644. Retrieved 2009-03-21.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Nina Burleigh (2007). Mirage. Harper. p. 135. ISBN 9780060597672.

- ^ Jan DeBlieu (1998). Wind. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 57. ISBN 9780395780336.

- ^ Britain's Sea Story, B.C. 55-A.D. 1805. Hodder and Stoughton. 1906. p. 30. Retrieved 2009-03-19.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Brandon Griggs and Jeff King (2009-03-09). "Boat made of plastic bottles to make ocean voyage". CNN. Retrieved 2009-03-19.

- ^ Jerry Cardwell (1997). Sailing Big on a Small Sailboat. Sheridan House, Inc. p. 118. ISBN 9781574090079. Retrieved 2009-03-19.

- ^ Brian Lavery and Patrick O'Brian (1989). Nelson's navy. Naval Institute Press. p. 191. ISBN 9781591146117. Retrieved 2009-06-20.

- ^ Underwater Archaeology Kids' Corner (2009). "Shipwrecks, Shipwrecks Everywhere". Wisconsin Historical Society. Retrieved 2009-03-19.

- ^ Carla Rahn Phillips (1993). The Worlds of Christopher Columbus. Cambridge University Press. p. 67. ISBN 9780521446525. Retrieved 2009-03-19.

- ^ Tom Benson (2008). "Relative Velocities: Aircraft Reference". NASA Glenn Research Center. Retrieved 2009-03-19.

- ^ Library of Congress (2006-01-06). "The Dream of Flight". Retrieved 2009-06-20.

- ^ "Flight Paths" (PDF). Bristol International Airport. 2004. Retrieved 2009-03-19.

- ^ Frederick A. Talbot (2008). Aeroplanes and Dirigibles of War. Read Books. pp. 29–47. ISBN 9781409782711. Retrieved 2009-06-20.

- ^ "Dirigible: United States Patent 3620485". FreePatentsOnline.com. 1971. Retrieved 2009-03-19.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Guillaume de Syon (2001). Zeppelin!: Germany and the Airship, 1900–1939. Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 155–157. ISBN 0801867347.

- ^ Federal Aviation Administration (2008). "FAA Historical Chronology, 1926-1996" (PDF). Retrieved 2009-03-19.

- ^ G. Juleff (January 1996). An ancient wind powered iron smelting technology in Sri Lanka. pp. 60–63.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ A.G. Drachmann (1961). Heron's Windmill. pp. 145–151.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Ahmad Y Hassan and Donald Routledge Hill (1986). Islamic Technology: An illustrated history. Cambridge University Press. p. 54. ISBN 0-521-42239-6.

- ^ Donald Routledge Hill (May 1991). Mechanical Engineering in the Medieval Near East. pp. 64–69.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Dietrich Lohrmann (1995). Von der östlichen zur westlichen Windmühle. pp. 1–30.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Kansas Wind Energy Project, Affiliated Atlantic & Western Group Inc, 5250 W 94th Terrace, Prairie Village, Kansas 66207

- ^ أ ب World Wind Energy Association (2009-02-06). "120 Gigawatt of wind turbines globally contribute to secure electricity generation". Press release. Retrieved 2009-02-06.

- ^ David Strahan (2009-03-11). "From AC to DC: Going green with supergrids". New Scientist. Retrieved 2009-03-13.

- ^ Glider Flying Handbook. U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington D.C.: U.S. Federal Aviation Administration. 2003. pp. 7–16. FAA-8083-13_GFH. Retrieved 2009-06-17.

- ^ Derek Piggott (1997). Gliding: a Handbook on Soaring Flight. Knauff & Grove. pp. 85–86, 130–132. ISBN 9780960567645.

- ^ أ ب Vern Hofman and Dave Franzen (1997). "Emergency Tillage to Control Wind Erosion". North Dakota State University Extension Service. Retrieved 2009-03-21.

- ^ أ ب James K. B. Bishop, Russ E. Davis, and Jeffrey T. Sherman (2002). "Robotic Observations of Dust Storm Enhancement of Carbon Biomass in the North Pacific". Science 298. pp. 817–821. Retrieved 2009-06-20.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ United States Geological Survey (2004). "Dunes - Getting Started". Retrieved 2009-03-21.

- ^ F. von Richthofen (1882). On the mode of origin of the loess. pp. 293–305.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Glossary of Geology. Springer-Verlag, New York. 2005. p. 779. ISBN 3-540-27951-2.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Introduction to Geography, Seventh Edition. McGraw Hill. 2000. p. 99. ISBN 0-697-38506-X.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|name=ignored (help) - ^ Science Daily (2001-06-15). "Microbes And The Dust They Ride In On Pose Potential Health Risks". Retrieved 2007-06-10.

- ^ Usinfo.state.gov (2003). "Study Says African Dust Affects Climate in U.S., Caribbean" (PDF). Retrieved 2007-06-10.

- ^ U. S. Geological Survey (2006). "Coral Mortality and African Dust". Retrieved 2007-06-10.

- ^ Weather Online (2009). "Calima". Retrieved 2009-06-17.

- ^ "Harmattan dust deposition and particle size in Ghana". Catena. 63 (1). 2005-06-13. Retrieved 2009-06-17.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|Pages=ignored (|pages=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Weather Online (2009). "Sirocco (Scirocco)". Retrieved 2009-06-17.

- ^ Bill Giles (O.B.E) (2009). "The Khamsin". BBC. Retrieved 2009-06-17.

- ^ Thomas J. Perrone (August 1979). "Table of Contents: Wind Climatology of the Winter Shamal". United States Navy. Retrieved 2009-06-17.

- ^ Plant Ecology, 2nd ed. Sinauer Associates, Inc., Massachusetts. 2006.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Short-term evolution of reduced dispersal in island plant populations. 1996. pp. 53–61.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ A. J. Richards (1997). Plant Breeding Systems. Taylor & Francis. p. 88. ISBN 9780412574504. Retrieved 2009-06-19.

- ^ Leif Kullman (September 2005). Wind-Conditioned 20th Century Decline of Birch Treeline Vegetation in the Swedish Scandes (PDF). pp. 286–294. Retrieved 2009-06-20.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Stand-replacing windthrow in the boreal forests of eastern Quebec. 2009-02-01. pp. 481–487. Retrieved 2009-06-20.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Michael A. Arnold (2009). "Coccoloba uvifera" (PDF). Texas A&M University. Retrieved 2009-06-20.

- ^ National Parks Service (2006-09-01). "Plants". Department of the Interior. Retrieved 2009-06-20.

- ^ D. R. Ames and L. W. lnsley (1975). Wind Chill Effect for Cattle and Sheep (PDF). pp. 161–165. Retrieved 2009-06-19.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Australian Antarctic Division (2008-12-08). "Adapting to the Cold". Australian Government Department of the Environment, Water, Heritage, and the Arts Australian Antarctic Division. Retrieved 2009-06-20.

- ^ Diana Yates (2008). "Birds migrate together at night in dispersed flocks, new study indicates". University of Illinois at Urbana - Champaign. Retrieved 2009-04-26.

- ^ Gary Ritchison (2009-01-04). "BIO 554/754 Ornithology Lecture Notes 2 - Bird Flight I". Eastern Kentucky University. Retrieved 2009-06-19.

- ^ Bart Geerts and Dave Leon (2003). "P5A.6 Fine-Scale Vertical Structure of a Cold Front As Revealed By Airborne 95 GHZ Radar" (PDF). University of Wyoming. Retrieved 2009-04-26.

- ^ Thomas A. Niziol (August 1998). "Contamination of WSR-88D VAD Winds Due to Bird Migration: A Case Study" (PDF). Eastern Region WSR-88D Operations Note No. 12. Retrieved 2009-04-26.

- ^ Jennifer Owen (1982). Feeding strategy. University of Chicago Press. pp. 34–35. ISBN 9780226641867.

- ^ Robert C. Eaton (1984). Neural mechanisms of startle behavior. Springer. pp. 98–99. ISBN 9780306415562. Retrieved 2009-06-19.

- ^ Bob Robb, Gerald Bethge, Gerry Bethge (2000). The Ultimate Guide to Elk Hunting. Globe Pequot. p. 161. ISBN 9781585741809. Retrieved 2009-06-19.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Wind and prey nest sites as foraging constraints on an avian predator, the glaucous gull. 1998. pp. 2403–2414. ISSN 0012-9658.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ T. P. Grazulis (2001). The tornado. University of Oklahoma Press. pp. 126–127. ISBN 9780806132587. Retrieved 2009-05-13.

- ^ Lightning: Principles, Instruments and Applications. Springer. 2009. pp. 202–203. ISBN 9781402090783. Retrieved 2009-05-13.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Derek Burch (2006-04-26). "How to Minimize Wind Damage in the South Florida Garden". University of Florida. Retrieved 2009-05-13.

- ^ National Hurricane Center (2006-06-22). "Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Scale Information". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 2007-02-25.

- ^ Storm Prediction Center (2007-02-01). "Enhanced F Scale for Tornado Damage". Retrieved 2009-05-13.

- ^ Mathematical model of a smoldering log (PDF). 2004. p. 228. Retrieved 2009-02-06.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help); More than one of|pages=and|page=specified (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ National Wildfire Coordinating Group (2007-02-08). NWCG Communicator's Guide for Wildland Fire Management: Fire Education, Prevention, and Mitigation Practices, Wildland Fire Overview (PDF). p. 5. Retrieved 2008-12-11.

- ^ National Wildfire Coordinating Group (2008). Glossary of Wildland Fire Terminology (PDF). p. 73. Retrieved 2008-12-18.

- ^ Ruth Murray-Clay (2008). "Atmospheric Escape Hot Jupiters & Interactions Between Planetary and Stellar Winds" (PDF). Boston University. Retrieved 2009-05-05.

- ^ E. Chassefiere (1996). Hydrodynamic escape of hydrogen from a hot water-rich atmosphere : The case of Venus. pp. 26039–26056. ISSN 0148-0227. Retrieved 2009-05-05.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ أ ب Rudolf Dvořák (2007). Extrasolar Planets. Wiley-VCH. pp. 139–140. ISBN 9783527406715. Retrieved 2009-05-05.

- ^ Dr. David H. Hathaway (2007). "The Solar Wind". National Aeronautic and Space Administration Marshall Space Flight Center. Retrieved 2009-03-19.

- ^ "A Glowing Discovery at the Forefront of Our Plunge Through Space". SPACE.com. 2000-03-15. Retrieved 2006-05-24.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|name=ignored (help) - ^ Earth in Space (March 1997). Geomagnetic Storms Can Threaten Electric Power Grid. pp. 9–11. Retrieved 2009-03-19.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ T. Neil Davis (1976-03-22). "Cause of the Aurora". Alaska Science Forum. Retrieved 2009-03-19.

- ^ Donald K. Yeomans (2005). "World Book at NASA: Comets". National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Retrieved 2009-06-20.

- ^ "Cloud-tracked winds from Pioneer Venus OCPP images" (PDF). Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences. 47 (17): 2053–2084. 1990. doi:10.1175/1520-0469(1990)047<2053:CTWFVO>2.0.CO;2.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ NASA (2004-12-13). "Mars Rovers Spot Water-Clue Mineral, Frost, Clouds". Retrieved 2006-03-17.

- ^ Dynamics of Jupiter’s Atmosphere (PDF). Lunar & Planetary Institute. 2003-07-29. Retrieved 2007-02-01.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Cassini Imaging Science: Initial Results on Saturn's Atmosphere". Science. 307 (5713): 1243–1247. 2005-02-25. Retrieved 2009-06-20.

{{cite journal}}: Text "DOI:10.1126/science.1107691" ignored (help) - ^ L. A. Sromovsky (2005). "Dynamics of cloud features on Uranus". Icarus. 179: 459–483. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2005.07.022. Retrieved 2009-06-17.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ H. B. Hammel (2005). "Uranus in 2003: Zonal winds, banded structure, and discrete features" (pdf). Icarus. 175: 534–545. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2004.11.012. Retrieved 2009-06-17.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ H. B. Hammel, K. Rages, G. W. Lockwood; et al. (2001). "New Measurements of the Winds of Uranus". Icarus. 153: 229–235. doi:10.1006/icar.2001.6689. Retrieved 2009-06-17.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Linda T. Elkins-Tanton (2006). Uranus, Neptune, Pluto, and the Outer Solar System. New York: Chelsea House. pp. 79–83. ISBN 0-8160-5197-6.

- ^ Jonathan I. Lunine (1993). The Atmospheres of Uranus and Neptune (PDF). Lunar and Planetary Observatory, University of Arizona. Retrieved 2008-03-10.

وصلات خارجية

- Meteorology Guides: Forces and Winds - Instructional module from the University of Illinois

- Names of Winds - A list from Golden Gate Weather Services

- Wind Atlases of the World - Lists of wind atlases and wind surveys from all over the world

- Winds of Mars: Aeolian Activity and Landforms - Paper with slides that illustrate the wind activity on the planet Mars

- Classification of Wind Speeds

- Wind-speed chart

- The Bibliography of Aeolian Research

- CS1 errors: unrecognized parameter

- CS1 errors: ISBN

- CS1 errors: unsupported parameter

- CS1 errors: access-date without URL

- CS1 errors: periodical ignored

- CS1 errors: redundant parameter

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- ديناميكا الغلاف الجوي

- ظواهر ومفاهيم أساسية بالأرصاد الجوية

- رياح