جستنيان الثاني

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

جستنيان الثاني Justinian II (باليونانية: Ἰουστινιανός Β΄، أيوستينيانوس الثاني، لاتينية: Iustinianus II) (669 – 11 ديسمبر 711)، لقبه Rhinotmetos أو Rhinotmetus (ὁ Ῥινότμητος، "the مشقوق-الأنف")، هو آخر امبراطور بيزنطي من الأسرة الهرقلية، حكم من عام 685 حتى 695 ومرة أخرى من 705 حتى 711. كان جستنيان الثاني حاكم طموح ومتحمس الذي كان حريصاً على استعادة أمجاد الامبراطورية السابقة، لكن استجابته كانت سيئة تجاه أي معارضة لإرادته وكان يفتقد دهاء والده، قسطنطين الرابع.[4] نتيجة لذلك، تكونت معارضة هائلة لحكمه، مما أسفر عن خلعه عام 685 بمساعدة الجيش البلغاري والسلاڤي. كان عهده الثاني أكثر استبداداً عن الأول، وشهد أيضاً الإطاحة به عام 711، وتخلى عنه جيشه الذي انقلب عليه قبل قتله.

عهده الأول

كان جستنيان الثاني الابن الأكبر للإمبراطور قسطنطين الرابع وأناستاسيا.[5] عيّنه والده وريثاً له بعد أكتوبر 681، إثر خلع عمّيه هراكليوس وتيبريوس.[ب] عام 685، وفي سن السادسة عشرة، خلف جستنيان الثاني والده كإمبراطور أوحد.[7][8]

حرب العملات

عام 687، وكجزء من اتفاقياته مع الأمويين، قام جستنيان بإخراج 12.000 مسيحي ماروني من موطنهم الأصلي لبنان، والذين كانوا يقاومون العرب باستمرار.[9] سمحت جهود إعادة التوطين الإضافية، التي استهدفت الجراجمة وسكان قبرص، لجستنيان بتعزيز القوات البحرية التي استنزفتها النزاعات السابقة.[10] عام 688، وقّع جستنيان معاهدة مع الخليفة عبد الملك بن مروان،[11] جرى بموجبها تقسيم العائدات الضريبية من أرمينيا وآيبريا وقبرص. بموجب الاتفاقية أصبحت قبرص منطقة حكم مشترك، منطقة محايدة يتقاسم فيها الإمبراطور والخليفة العائدات الضريبية بالتساوي لما يقارب 300 سنة. سعى عبد الملك بن مروان إلى هذا السلام للتركيز على الفتنة الثانية، فانتهز الإمبراطور البيزنطي جستنيان الثاني هذه الفرصة ونقض المعاهدة التي سبق وأن أبرمها البيزنطيون مع المسلمين عام 688، [12] وساق جيوشه لقتالهم فاجتاح بعض بلاد الشام عام 689. في هذه الفترة وقع على الطرف الشرقي للإمبراطورية البيزنطية حادث أثر على سير العلاقات بين المسلمين والروم، كانت هناك جماعات من الجراجمة في جبال الأمانوس قد ألفوا جيشاً واتخذت منهم السلطات البيزنطية سياجاً حدودياً بينها وبين المسلمين في هذه المنطقة، كان الجراجمة بحكم موقعهم الجغرافي ووضعهم السياسي يحمون الدولة البيزنطية من هجمات المسلمين ويدافعون عن معاقلهم الجبلية المنيعة ضد أي اعتداء خارجي، وكثيرًا ما توغلوا جنوباً حتى وصلوا إلى جبال لبنان، وقد ضايقوا المسلمين بما كانوا يشنونه من غارات مستمرة على المناطق المجاورة خاصة المناطق الساحلية. اضطر عبد الملك بن مروان وفقاً للظروف الحالية إلى المهادنة تفادياً لحروب جديدة في المنطقة، وللتفرغ للمشاكل الداخلية التي استجدت في العالم الإسلامي، فعقد مع الإمبراطور البيزنطي جستنيان الثاني معاهدة عام 689، تعهد الخليفة بمقتضاها بالتالي: أن يدفع للإمبراطور البيزنطي مبلغاً مقداره 365.000 قطعة ذهبية، و365 عبداً، و365 خيلاً أصيلاً في مقابل وقف الغارات البيزنطية على الأراضي الإسلامية، وأن تقتسم الدولتان الإسلامية والبيزنطية خراج أرمينيا وقبرص وإيبيريا، وأن تسحب الإمبراطورية البيزنطية الجراجمة من منطقتي جبال لبنان وشمالي الشام إلى ما وراء جبال طوروس في آسيا الصغرى، وأن تستمر هذه المعاهدة مدة عشر أعوام.

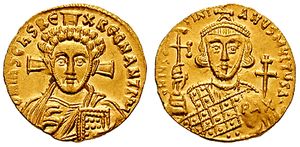

في قبرص، تنفيذاً للمعاهدة، كان ينبغي تقسيم العائدات الضريبية، ومن ثم نشأت مشكلة العملة، والتي تُعتبر أول حرب عملات في التاريخ. كانت الإمبراطورية البيزنطية تستخدم السوليدوس الذهبي بينما كانت الدولة الأموية تستخدم الدينار الذهبي. في الواقع، لم يكن الخلاف بين الخليفة عبد الملك بن مروان والإمبراطور جستنيان الثاني يدور حول مكونات الذهب (نقاوته) بقدر ما كان يدور حول السيادة والرموز الدينية ومعايير الوزن. اندلع النزاع عندما أصدر عبد الملك بن مروان أول دينار ذهبي إسلامي مستقل حوالي عام 691-692. وقد تسبب ذلك في احتكاكات لثلاثة أسباب رئيسية:

1- تغير الوزن: بينما كان السوليدوس البيزنطي هو المعيار العالمي للذهب (حوالي 4.5 جرام)، سُك الدينار الإسلامي الجديد عمداً بمعيار أخف قليلاً (حوالي 4.25 جرام). لم يكن هذا محاولة للتلاعب بمحتوى الذهب، بل خطوة لإنشاء وحدة وزن إسلامية مميزة تُسمى المثقال. رأى البيزنطيون في ذلك تحدياً مباشراً لاحتكارهم الاقتصادي ونزاهة التجارة الدولية.

2- الرموز الدينية (السبب الحقيقي للخلاف): كانت القضية الأكثر إثارة للجدل هي ما نُقش على العملتين المعدنيتين.

- رد الأمويين: في البداية، قام عبد الملك بسك عملات معدنية أزالت الصليب المسيحي على الدرجات واستبدلته بعمود على الدرجات. وفي وقت لاحق، قدم عملة "الخليفة واقفاً"، التي تضمنت صورته.

- رد فعل البيزنطيين: استشاط جستنيان الثاني غضباً. ورد بسك عملة ذهبية جديدة تحمل صورة المسيح لأول مرة في التاريخ. ثم رفض قبول العملات الأموية كدفعة لتقاسم العائدات كما هو متفق عليه في معاهدة عام 688، معلناً أنها "مزيفة" لكونها لا تحمل صورة الإمبراطور.

أدت "حرب العملات" بشكل مباشر إلى اندلاع معركة سباستوپوليس (692 م)، حيث انهارت معاهدة السلام بين البيزنطيين والعرب.

سياساته الداخلية وخلعه

أصبح بإمكان جستنيان الآن أن يوجه اهتمامه إلى البلقان، حيث فقدت الكثير من الأراضي الإمبراطورية لصالح القبائل السلاڤية.[9] عام 687، نقل جستنيان قوات الفرسان من الأناضول إلى تراقيا. وبفضل حملة عسكرية عظيمة في عامي 688-689، هزم جستنيان السلاڤ في مقدونيا، وتمكن أخيراً من دخول سالونيك، ثاني أهم مدينة بيزنطية في أوروپا.[10]

أُعيد توطين السلاڤ المُستَضعفين في الأناضول، حيث كان من المُفترض أن يُشكلوا قوة عسكرية قوامها 30.000 رجل.[10] بعد أن تشجع جستنيان بزيادة قواته في الأناضول، جدد الحرب ضد العرب،[13] منتصراً في معركة في أرمينيا عام 693. واجه العرب التحدي برشوة الجيش الجديد للتمرد. انشق معظم الجنود السلاڤيين أثناء معركة سباستوپوليس اللاحقة،[14] حيث هُزم جستنيان هزيمة ساحقة وأُجبر على الفرار إلى پروپونتيس.[13] هناك، وفقاً لثيوفانس،[15] أفرغ إحباطه بذبح أكبر عدد ممكن من السلاڤ في وحول أوپسيكيون بقدر ما استطاع أن تصل يديه منهم.[16] في هذه الأثناء، ثار أحد الأشراف يُدعى سيمباتيوس في أرمينيا[13] وفتح المقاطعة أمام العرب، الذين شرعوا في فتحها في الفترة ما بين 694 و695.[10]

أما في ما يخص الشؤون الداخلية، فقد مارس الإمبراطور اضطهاداً دموياً ضد المانويين[8] وأدى قمع التقاليد الشعبية ذات الأصل غير الخلقيدوني إلى حدوث انشقاق داخل الكنيسة.[5] عام 692، عقد جستنيان في القسطنطينية ما يسمى بالمجمع الخامس-السادس لتطبيق سياساته الدينية.[17] قام المجمع بتوسيع وتوضيح أحكام المجمعين المسكونيين الخامس والسادس، لكن من خلال تسليط الضوء على الاختلافات بين الطقوس الشرقية والغربية (مثل زواج الكهنة وصيام يوم السبت لدى الكاثوليك) فقد أدى ذلك أيضاً إلى الإضرار بالعلاقات البيزنطية مع الكنيسة الكاثوليكية.[18] أمر الإمبراطور باعتقال الپاپا سرگيوس الأول، لكن ميليشيات روما وراڤـِنـّا تمردت وانحازت إلى جانب الپاپا.[10]

ساهم جستنيان في تطوير تنظيم الثيمات (تقسيمات إدارية) الإمبراطورية، فأنشأ ثيمة جديدة في جنوب اليونان تسمى هـِلاس، وجعل رؤساء الثيمات الأربعة الرئيسية، وهي أوپسيكيون، أناتوليكون، تراكسيون، وأرمنياكون، بالإضافة إلى فيلق كارابيسيانوي البحري، من بين كبار إداريي الإمبراطورية.[10] كما سعى إلى حماية حقوق الفلاحين الملاك الأحرار، الذين شكلوا المصدر الرئيسي لتجنيد الجيوش الإمبراطورية، من محاولات الطبقة الأرستقراطية للاستيلاء على أراضيهم. وقد وضع هذا الأمر في نزاع مباشر مع بعض كبار الملاك في الإمبراطورية.[10]

في حين أن سياساته المتعلقة بالأراضي هددت الطبقة الأرستقراطية، إلا أن سياسته الضريبية لم تحظى بشعبية كبيرة لدى عامة الشعب.[10] من خلال وكيليه ستيفن وثيودوتوس، جمع الإمبراطور الأموال لإشباع أذواقه الباذخة وهوسه ببناء المباني المكلفة.[10][8] أدى هذا السخط الديني المستمر، والنزاعات مع الطبقة الأرستقراطية، والاستياء من سياسة إعادة التوطين التي انتهجها، في نهاية المطاف إلى دفع رعاياه إلى التمرد.[17] عام 695، ازداد عدد السكان في عهد ليونتيوس، ستراتيگوس هـِلاس، وأعلنوه إمبراطوراً.[10][8] عُزل جستنيان، وجُدع أنفه (ثم استُبدل لاحقاً بأنف اصطناعي من الذهب الخالص) لمنعه من السعي إلى العرش مرة أخرى: كان هذا التشويه شائعاً في الثقافة البيزنطية. نُفي جستنيان إلى خرسون في القرم.[10] بعد حكم دام ثلاث سنوات، عُزل ليونتيوس وبدوره سُجن على يد تيبريوس أپسيماروس، الذي تولى العرش بعد ذلك.[19][8]

المنفى

While in exile, Justinian began to plot and gather supporters for an attempt to retake the throne.[20] Justinian became a liability to Cherson and the authorities decided to return him to Constantinople in 702 or 703.[21] He escaped from Cherson and received help from Busir, the khagan of the Khazars, who received him enthusiastically and gave him his sister as a bride.[20] Justinian renamed her Theodora, after the wife of Justinian I.[22] They were given a home in the town of Phanagoria, at the entrance to the sea of Azov. Busir was offered a bribe by Tiberius to kill his brother-in-law, and dispatched two Khazar officials, Papatzys and Balgitzin, to do the deed.[23] Warned by his wife, Justinian executed Papatzys and Balgitzin. He sailed in a fishing boat to Cherson, summoned his supporters, and they all sailed westwards across the Black Sea.[24]

As the ship bearing Justinian sailed along the northern coast of the Black Sea, he and his crew became caught up in a storm somewhere between the mouths of the Dniester and the Dnieper Rivers.[23] While it was raging, one of his companions reached out to Justinian saying that if he promised God that he would be magnanimous, and not seek revenge on his enemies when he was returned to the throne, they would all be spared.[24] Justinian retorted: "If I spare a single one of them, may God drown me here".[23]

Having survived the storm, Justinian next approached Tervel of Bulgaria.[24] Tervel agreed to provide all the military assistance necessary for Justinian to regain his throne in exchange for financial considerations, the award of a Caesar's crown, and the hand of Justinian's daughter, Anastasia, in marriage.[20] In spring 705, with an army of 15,000 Bulgar and Slav horsemen, Justinian appeared before the walls of Constantinople.[20] For three days, Justinian tried to convince the citizens of Constantinople to open the gates, but to no avail.[25] Unable to take the city by force, he and some companions entered through an unused water conduit under the walls of the city, roused their supporters, and seized control of the city in a midnight coup d'état.[20] On 21 August,[26] Justinian regained the throne, breaking the tradition preventing the mutilated from Imperial rule. After tracking down his predecessors, he had his rivals Leontius and Tiberius brought before him in chains in the Hippodrome. There, before a jeering populace, Justinian, now wearing a golden nasal prosthesis,[27] placed his feet on the necks of Tiberius and Leontius in a symbolic gesture of subjugation before ordering their execution by beheading, followed by many of their partisans,[28] as well as deposing, blinding and exiling Patriarch Callinicus I to Rome.[29]

عهده الثاني

Justinian's second reign was marked by unsuccessful warfare against Bulgaria and the Caliphate, and by cruel suppression of opposition at home.[30] In 708 Justinian turned on Bulgarian Khan Tervel, whom he had earlier crowned caesar, and invaded Bulgaria, apparently seeking to recover the territories ceded to Tervel as a reward for his support in 705.[28] The Emperor was defeated, blockaded in Anchialus, and forced to retreat.[28] Peace between Bulgaria and Byzantium was quickly restored. This defeat was followed by Arab victories in Asia Minor,[8] where the cities of Cilicia fell into the hands of the enemy, who penetrated into Cappadocia in 709–711.[30]

He ordered Pope John VII to recognize the decisions of the Quinisext Council and simultaneously fitted out a punitive expedition against Ravenna in 709 under the command of the Patrician Theodore.[31] The expedition was led to reinstate the Western Church's authority over Ravenna, which was taken as a sign of disobedience to the emperor, and revolutionary sentiment.[32] The repression succeeded, and the new Pope Constantine visited Constantinople in 710. Justinian, after receiving Holy Communion at the hands of the pope, renewed all the privileges of the Roman Church. Exactly what passed between them on the subject of the Quinisext Council is not known. It would appear, however, that Constantine approved most of the canons.[33] This would be the last time a Pope visited the city until the visit of Pope Paul VI to Istanbul in 1967.[27]

Justinian's rule provoked another uprising against him.[34] Cherson revolted, and under the leadership of the exiled general Bardanes the city held out against a counter-attack. Soon, the forces sent to suppress the rebellion joined it.[21] The rebels then seized the capital and proclaimed Bardanes as Emperor Philippicus;[35] Justinian had been on his way to Armenia, and was unable to return to Constantinople in time to defend it.[36] He was arrested and executed in November 711, his head being exhibited in Rome and Ravenna.[5]

On hearing the news of his death, Justinian's mother took his six-year-old son and co-emperor, Tiberius, to sanctuary at St. Mary's Church in Blachernae, but was pursued by Philippicus' henchmen, who dragged the child from the altar and, once outside the church, murdered him, thus eradicating the line of Heraclius.[36]

التبجيل

| Justinian II | |

|---|---|

Justinian II Solidus | |

| Emperor | |

مكرّم في | Eastern Orthodox Church (disputed) |

| عيده | 2 August |

The veneration of Justinian II in the Orthodox Church is the subject of debate and confusion, as there are discrepancies in different Synaxarions. The Synaxarion of Constantinople from the 10th century lists the commemoration of the "Emperor Justinian", giving no reference of the emperor's life or whether it is Justinian I or II.[37] Contemporary footnotes comment that this must be Justinian II, since Justinian I died in heresy, a position not held by the Orthodox Church today.[38] According to Saint Nikodemos the Hagiorite, Emperor Justinian II was a bad man who lived a bad life, and he could not imagine that he would be commemorated as a saint, since in the Synaxarion of Saint Kallinikos of Constantinople on August 23, it does not say he died in repentance. Saint Nikodemos suggests this must be Justinian I, who is also celebrated the 15th of November with his wife Theodora.[39]

Modern English translations and some Greek Synaxarions now list either Justinian I on August 2 or make no reference to either Justinian I or II. However, there are some Greek Synaxarions that list Justinian II.[40][41]

العائلة

By his first wife Eudokia, Justinian II had at least one daughter, Anastasia, who was betrothed to the Bulgarian ruler Tervel. By his second wife, Theodora of Khazaria, Justinian II had a son, Tiberius, co-emperor from 706 to 711.

روايات تاريخية

Justinian, a 1998 novel by Byzantine scholar Harry Turtledove, writing under the name H. N. Turteltaub, gives a fictionalized version of Justinian's life as retold by a fictionalized lifelong companion, the soldier Myakes.[42] In the novel, Turtledove speculates that while in exile Justinian had reconstructive surgery done by an itinerant Indian plastic surgeon to repair his damaged nose.[43]

في الثقافة الشعبية

ظهرت شخصية جستنيان الثاني في مسلسل فارس بني مروان وجسدها الممثل جمال سليمان.

انظر أيضاً

المراجع

مراجع أساسية

Theophanes, Chronographia.

مراجع ثانوية

- Kazhdan, Alexander, ed. (1991), Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-504652-6

- Norwich, John Julius (1990), Byzantium: The Early Centuries, Penguin, ISBN 0-14-011447-5

- Ostrogorsky, George; Hussey (trans.), Joan (1957), History of the Byzantine state, New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, ISBN 0-8135-0599-2

- Canduci, Alexander (2010), Triumph & Tragedy: The Rise and Fall of Rome's Immortal Emperors, Pier 9, ISBN 978-1-74196-598-8

- Moore, R. Scott, "Justinian II (685–695 & 705–711 A.D.)", De Imperatoribus Romanis (1998)

- Bury, J.B., A History of the Later Roman Empire from Arcadius to Irene, Vol. II, MacMillan & Co., 1889

- تحوي هذه المقالة معلومات مترجمة من الطبعة الحادية عشرة لدائرة المعارف البريطانية لسنة 1911 وهي الآن من ضمن الملكية العامة.

ملاحظات

- ^ His name is rarely given as Flavius Heraclius Iustinianus in older sources,[2][3] but this is not corroborated by modern historians or contemporary coins or writings.

- ^ Theophanes the Confessor states that Constantine ruled alongside Justinian after the fall of Heraclius and Tiberius. However, all the evidence indicates that he became augustus only on his father's death.[6]

المصادر

- ^ Vasiliev 1943.

- ^ Johann George Estor (1766). Freiheit der Teutschen Kirchen, fürnämlich in Rücksicht auf Se. Kaiserliche Majestät, und im Betreffe der Teutschen Reichs-Stände wider die Eingriffe der Curialen zu Rom. p. 101. ISBN 9781271731411.

- ^ Baudartius, Willem (1632). Apophthegmata christiana, ofte: Ghedenck-weerdige, leersame, ende aerdighe spreuken, van vele ende verscheydene christelicke ende christen-ghelijcke persoonen gesproken ...: alles uyt vele gheloof-weerdighe scribenten met grooten vlijt versamelt ... p. 196.

- ^ Ostrogorsky, pgs. 116–122

- ^ أ ب ت خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةKazhdan, p. 1084 - ^ Grierson 1968, pp. 512–514.

- ^ Grierson 1968, p. 568.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . دائرة المعارف البريطانية. Vol. 15 (eleventh ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 602.

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . دائرة المعارف البريطانية. Vol. 15 (eleventh ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 602. {{cite encyclopedia}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ أ ب Bury 1889, p. 321

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د ذ ر ز خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةOstrogorsky, pp. 116-122 - ^ Romilly J.H. Jenkins (1970), Studies on Byzantine History of the 9th and 10th Centuries, p. 271.

- ^ وهبة الزحيلي (1434 هـ - 2013م). آثار الحرب: دراسة فقهية مقارنة (الطبعة الأولى). دمشق - سوريا. دار الفكر صفحة 316

- ^ أ ب ت Bury 1889, p. 322

- ^ Norwich 1990, p. 330

- ^ Theophanes: AM 6183

- ^ Norwich 1990, pp. 330–331

- ^ أ ب Bury 1889, p. 327

- ^ Norwich 1990, p. 332

- ^ Bury 1889, p. 354

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج Ostrogorsky 1956, pp. 124–126

- ^ أ ب خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةMoore, Justinian II - ^ Bury 1889, p. 358

- ^ أ ب ت Bury 1889, p. 359

- ^ أ ب ت Norwich 1990, p. 336

- ^ Bury 1889, p. 360

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةTombs - ^ أ ب Norwich 1990, p. 345

- ^ أ ب ت Bury 1889, p. 361

- ^ Norwich, p. 338

- ^ أ ب Norwich 1990, pp. 339

- ^ Bury 1889, p. 366

- ^ Liber pontificalis 1:389

- ^ Pope Constantine. New Advent

- ^ Norwich 1990, p. 342

- ^ Norwich 1990, p. 343

- ^ أ ب Bury 1889, pp. 365–366

- ^ Συναξαριστής REF BX 393 .N54 1929 v2

- ^ Gerostergios, Fr.Asterios (2004). The Justinian the Great The Emperor and Saint, p. 147

- ^ "Saint Justinian II Rhinotmetos, the Pious Emperor of the Romans (+ 711)".

- ^ "Αυτοκράτορες που έγιναν Άγιοι". 3gym-mikras.thess.sch.gr. Retrieved 17 July 2021.

- ^ "Ορθόδοξος Συναξαριστής :: Άγιος Ιουστινιανός Β' ο βασιλιάς". www.saint.gr. Retrieved 17 July 2021.

- ^ According to Turtletaub/Turtledove, Myakes is a historical character, the soldier in the boat with Justinian in the Black Sea storm, according to history, who unsuccessfully urged Justinian to become less vindictive. See Turtletaub, Justinian, at p. 510.

- ^ Turtletaub/Turtledove attributes to Richard Delbrück the same conjecture, stating that Delbrück was able to cite iconographic evidence to support the conjecture. See Turteltaub, Justinian, at p. 511.

وصلات خارجية

جستنيان الثاني وُلِد: 669 توفي: ديسمبر 711

| ||

| ألقاب ملكية | ||

|---|---|---|

| سبقه قسطنطين الرابع |

الامبراطور البيزنطي 685–695 مع قسطنطين الرابع، 681–685 |

تبعه ليونتيوس |

| سبقه تيبريوس الثالث |

الامبراطور البيزنطي 705–711 مع تيبريوس، 706–711 |

تبعه فيليپيكوس |

- مقالات المعرفة المحتوية على معلومات من دائرة المعارف البريطانية طبعة 1911

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Articles containing لاتينية-language text

- Articles containing Greek-language text

- Pages using Lang-xx templates

- Articles containing Ancient Greek (to 1453)-language text

- مقالات مأخوذة من الطبعة الحادية عشرة لدائرة المعارف البريطانية

- مواليد 669

- وفيات 711

- أباطرة بيزنطيون من القرن السابع

- أباطرة بيزنطيون من القرن الثامن

- أسرة هرقل

- بيزنطيون من الحروب البيزنطية العربية

- بيزنطيون معدمون

- قناصل الامبراطورية الرومانية

- قرم العصور الوسطى

- فوضى العشرين عام

- عقد 680 في الامبراطورية البيزنطية

- عقد 700 في الامبراطورية البيزنطية

- عقد 710 في الامبراطورية البيزنطية