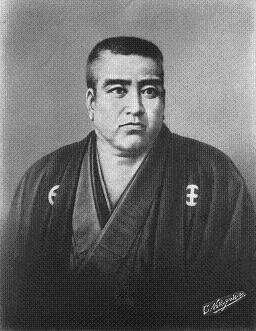

سائيگو تاكاموري

سائيگو تاكاموري | |

|---|---|

سائيگو تاكاموري (西郷 隆盛) | |

| الاسم المحلي | 西郷隆盛 |

| اسم الميلاد | Saigō Kokichi |

| أسماء أخرى | Saigō Nanshū Saigō Kichinosuke Kikuchi Gengo |

| ولد | 24 يناير 1827/1828] كاگوشيما، اليابان |

| توفي | 24 سبتمبر 1877 (aged 49) كاگوشيما، اليابان |

| دُفـِن | Nanshu Cemetery, Kagoshima Prefecture, Japan |

| الولاء | Satsuma Domain |

| الرتبة | Field Marshal |

| المعارك/الحروب | |

| الزوج | Suga Ijuin

(m. 1852; div. 1854)Otoma Kane "Aigana"

(m. 1859–1862)Iwayama Itoko

(m. 1865) |

| الأنجال | Saigō Kikujirō (son) Saigō Kikusō (daughter) Saigō Toratarō (son) Saigō Umajirō (son) Saigō Torizō (son) |

سائيگو تاكاموري (西郷 隆盛) ع(1827-1877 م.) هو قائد عسكري وسياسي ياباني، أحد الثلاثة الكبار مع "أوكوبو توشيميتشي" (大久保 利通) و"كيدو تاكايوشي" (木戸孝允) الذين قادوا الحركة (إستعراش مييجي) التي أسفرت على إعادة الحكم للإمبراطور والقضاء على النظام الإقطاعي القديم. كان في بداية أمره من المعارضين لمظاهر سلطة نظام الـ"شوگون"، فقاد عدة حركات لإعادة السلطة الإمبراطورية، ثم انقلب في آخر حياته ضد حلفاءه فقاد حركة المعارضين وانتهى أمره بأن اختار الانتحار طواعية ("سپوكو") بعد هزيمته أتباعه.

الولادة والنشأة

ولد في "كاگوشيما" (جزيرة "كيوشو")، من عائلة متواضعة من الـ"ساموراي"، تلقى تربية تقليدية مشبعة بتعاليم المحاربين المحليين في منطقته، تابع دروسا تعليمية في المدرسة الرسمية لعشيرة الـ"شيمازو" (島津)، أصحاب معقل "ساتسوما" (薩摩)، تعرف أثناءها على "أوكوبو توشيميتشي" (大久保 利通) ، زميله في الدراسة. كان لـ"سائيگو" بنية قوية وقامة فارعة (كان من مصارعي الـ"سومو")، ساعده ذلك في أن يشتهر بين الناس بالهمة والنشاط، فأصبح محبوبا. قام بالانضمام إلى قوات معقله المناصرة للإمبراطور التي التي كانت تحارب قوات الـ"شوگون" من أسرة الـ" توكوگاوا". غادر سنة 1854 م "ساتسوما" برفقة "شيمازو ناري-آكيرا" سيد عشيرة "شيمازو" حكام المعقل المحلي ("ساتسوما")، كانت وجهتهم العاصمة "إيدو" (اليوم "طوكيو") للمشاركة في إحدى المناورات العسكرية الموجهة ضد قوات الـ"شوگون". توفي "ناري-آكيرا" سنة 1585 م، فأصبح "سائيگو" مطاردا بعد الحملة التي شنها القائم بأعمال الشوگون "إيئي نا-أوسوكي" ضد أتباع "ناري-آكيرا". اضطر أثناء فراره من رجال شرطة الـ"شوگون" إلى أن يلقي بنفسه ورفيقه دربه الكاهن "گيشو" في خليج "كاگوشيما"، كاد "سائيگو" أن يلقى حتفه على أثرها، إلا أنه تم انتشاله وإعادة تنشيطه. أمضى الفترة التالية في المنفى في إحدى الجزر. قام أثناء منفاه بمساعدة مزارعي قصب السكر المحليين، كما أصبح ربا لعائلة صغيرة.

قائد الجيوش

شمله العفو سنة 1861 م فتم إطلاق سراحه، إلا أنه لم يطل به الحال حتى قام بحركة جديدة للسيطرة على العاصمة "كيوتو" (العاصمة الإمبراطورية)، كان قد استبق في ذلك سيده الجديد "شيمازو هيزاميستيو" والذي كان يطمح إلى قيادة هذه الحركة بنفسه، فغضب الأخير عليه. وجد "سائيگو" نفسه مرة أخرى في المنفى، وطال به الأسر حتى 1864 م . تم الصفح عنه مجددا، فعين رئيسا لمجلس الحرب في معقل "ساتسوما" (薩摩) ثم موفدا مع "أوكوبو توشيميتشي" إلى البلاط الإمبراطوري في "كيوتو". قاد سائيگو القوات التي واجهت جماعة المتشديدين من معقل "تشوشو" والذين حاولوا اقتحام القصر الإمبراطوري. أعلنت هدنة بين البلاطين (الـ"شوگوني" والإمبراطوري)، فأرسل "سائيگو" على رأس جيش موحد لتأديب معقل "تشوشو"، ثم فتح على أثرها الباب للتفاوض مع ممثلين عن هذا المعقل. مع قيام حملة ثانية سنة 1866 م ضد نفس المعقل أوعز "سائيگو" لأصحابه في "ساتسوما" بالتزام الحياد حتى تهدأ الأمور.

بعد انهيار النظام القديم واستقالة الـ"شوگون"، تولى "سائيجو" قيادة القوات النظامية، فقضى على الثورات في كل من "توبا" و"فوشيمي"، كما نظم عملية الانتقال السلمي للسلطة في "إدو" (والتي أصبحت تسمى "طوكيو")، كما أصر على يتم العفو عن كامل أفراد جيش الـ"شوگون" السابق.

بعد إشرافه على عملية نقل السلطة إلى الإمبراطور "مييجي" ("موتسو هيتو")، رفض كل التشريفات التي عرضت عليه فاعتزل السياسة والحكم وانسحب إلى مقاطعته الأصلية. بعد إلحاح الحكومة الجديدة، عاد إلى "طوكيو" سنة 1871 م ليرأس حكومة انتقالية بعدما غادر "أوكوبو" والعديد من كبار المسئولين البلاد إلى الغرب. أصبح القائد الأعلى للقوات سنة 1872 م ثم رقي إلى رتبة "مارشال" في العام الموالي (1873 م). بعدما قامت "كوريا" بإهانة اليابان سنة 1873 م، أصر "سائيگو" على شن الحرب عليها، وأمام رفض الحكومة القاطع لفكرته لم يجد أمامه خيار آخر غير الاستقالة.

الساموراي الأخير

عاد مجددا إلى "ساتسوما" وقام بتأسيس مدارس حربية حتى يشغل أتباعه من رجال الـ"ساموراي" السابقين. علمت الحكومة بالأمر فأرسلت سفينة حربية في مهمة تجريد دار الصناعة الحربية في ميناء "كاگوشيما" من الأسلحة. بعد هذه العملية ثارت ثائرة أتباع "سائيگو" على الحكومة، كان العديد منهم حانقا على الإمبراطور والحكومة بعد الإجراءات التي تم اتخاذها ضدهم منذ 1868 م (تجريدهم من الأراضي، الرواتب والحق في حمل السلاح). تطورت الأمور وأصبحت ثورة مفتوحة على النظام الجديد. غادر "سائيگو" "كاگوشيما" والتحق بالثوار، أصبح زعميهم الجديد، كان قد اقتنع باستبداد وفساد "أوكوبو" وحكومته. بعد عدة أشهر من المعارك المتواصلة ضد جيش من النظاميين، حوصرت قوات الثوار بالقرب من مغارة في "كاگوشيما". خاض "سائيگو" وأتباعه معركتهم الأخيرة يوم 24 سبتمبر 1877 م، جرح على أثرها، وتأكد من هزيمته المحقة، ففضل أن ينتحر طواعية ("سپوكو" أو "هاراكيري") ، قام أتباعه باغتيال رئيس الحكومة "أوكوبو توشي-ميتشي" سنة 1877 م لمسؤوليته في مصرع قائدهم.

سنة 1891 م قامت الحكومة اليابانية بإصدار مرسوم عفو عن "سائيگو" نظرا لأعماله الجليلة وتفانيه في خدمة وطنه، أصبح يلقب باسم "سائيگو الكبير" كما يعده اليابانيون من الأبطال القوميين.

وفاته

On the morning of 24 September 1877, the imperial army launched its final assault on Shiroyama. Vastly outnumbered and outgunned, Saigō's forces were quickly overwhelmed.[1] During the fighting, Saigō was severely wounded in the hip and abdomen by a bullet.[2][3] According to the most widely accepted accounts and legends, Saigō, unable to proceed, committed ritual suicide (seppuku). He turned to his close associate Beppu Shinsuke and said, "Shinsuke, I think this place will do. Please be my second (kaishakunin)." Saigō then calmly faced east towards the Imperial Palace, bent his head, and Beppu severed his head with a single sword stroke.[4][3][5] Saigō's autopsy, however, revealed no wounds to his abdomen consistent with seppuku, suggesting he was likely too crippled by his gunshot wounds to perform the ritual and was beheaded by Beppu to prevent capture or a less honorable death.[6]

Saigō's head was hidden by his manservant Kichizaemon to prevent it from falling into enemy hands, a common practice in samurai warfare to deny the victor a complete triumph.[6] The imperial army, honoring ancient warrior traditions despite its modern nature, frantically searched for the head.[7] It was eventually recovered later the same day, reportedly by an imperial army soldier named Maeda Tsunemitsu.[8] Saigō's head was then unceremoniously rejoined with his body, which lay with other rebel leaders on a hill near the imperial army's barricades.[8]

The death of Saigō, along with his chief lieutenants, effectively ended the Satsuma Rebellion. Within a year, all three of the principal leaders of the Meiji Restoration were dead: Kido Takayoshi had died of illness during the rebellion in May 1877, Saigō died in battle on 24 September 1877, and Ōkubo Toshimichi was assassinated in May 1878 by samurai resentful of his role in suppressing the rebellion. The passing of these founding figures marked the end of the initial, tumultuous phase of the Restoration, leaving their successors to complete the institutionalization of the Meiji state.[9]

الحياة الشخصية

Saigō was married three times. His first marriage in 1852 to Ijuin Suga, arranged by his family, was short-lived and ended in annulment after two years when Saigō was transferred to Edo.[10] He reportedly expressed little interest in sex, and the divorce led him to a period of sexual self-denial.[11]

During his first exile on Amami Ōshima, he married Aigana (born Otoma Kane), a local woman from a prominent island family, in 1859.[12][13] She was described as beautiful but was illiterate and had the traditional tattooed hands of Amami women.[14] They had a son, Kikujirō (born 1861), and a daughter, Kikusō (born c. 1862).[15][16] Saigō reportedly enjoyed his life with Aigana and their children, later writing that his family on Amami was a source of great happiness.[14] He left Amami in 1862 and never saw Aigana again, though their children eventually joined him in Kagoshima.[15]

In 1865, after his rise to national prominence, Saigō married Iwayama Ito, the daughter of a Satsuma domain official, a prestigious match.[17][18] With Ito, he had three sons: Toratarō, Umajirō (son), and Torizō.[19] Their marriage was described as harmonious but apparently lacked deep intimacy.[17][18] Saigō is also reported to have had a favored geisha in Kyoto known as "Princess Pig" (Butahime) due to her portly figure, a match for Saigō's own considerable size.[17]

Saigō was physically imposing, nearly six feet (c. 182 cm) tall and with a powerful, wrestler-like build, described as "Herculean".[20] He suffered from various health problems throughout his life, including filariasis, which led to dropsy of the scrotum and significant weight gain.[21] In his later years, he also experienced severe angina due to arteriosclerosis.[22] He had a quick, fiery temperament,[23] but was also known for his stoicism and an intimidating taciturn gaze.[23] Despite this, he possessed a deep sentimentality, known to weep openly at sentimental plays.[23] His favorite pastimes included hunting with his dogs and fishing, and he enjoyed making his own hunting sandals from straw and his own fishing lures.[24] He preferred simple, traditional pleasures and disliked the elaborate Western-style clothing and entertainments adopted by many of his Meiji-era contemporaries.[24]

ذكراه

Saigō Takamori's death marked the end of the last major armed uprising against the Meiji government and solidified the authority of the centralized state. Despite being a rebel leader, his image quickly transformed into that of a tragic hero and a symbol of true samurai spirit.[25][26] He is often referred to as "the last true samurai."[27]

Popular mythology surrounding Saigō flourished even before his death and intensified afterwards. Legends claimed he had not died but had escaped to China or India, or that he had ascended to the heavens and become the planet Mars or a comet.[28][29][30] Woodblock prints (nishiki-e) depicted him in heroic poses, often in full imperial army uniform despite his rebel status, or as an enlightened being attaining nirvana, surrounded by grieving commoners and animals, paralleling depictions of the Buddha.[31] These images reflected a deep public sympathy for Saigō and a desire to see him as a virtuous figure, even a demigod, who stood for traditional values against a rapidly modernizing and sometimes perceived as corrupt government.[32] His untimely death ensured his memory was not "contaminated by the compromises that practical politics required of those who survived."[33] He became a "Protean figure, large in life and larger in death, with a legacy for would-be populists as well as militarists."[9] The government, initially hostile, eventually embraced Saigō's legend. On 22 February 1889, as part of a general amnesty commemorating the promulgation of the Meiji Constitution, Saigō was posthumously pardoned and his imperial court rank restored.[34][26] He was subsequently transformed into an exemplar of Japanese virtue in school textbooks.[35]

The most famous public monument to Saigō is the bronze statue in Ueno Park, Tokyo, unveiled in 1898.[36] It depicts him in simple attire with his dog, reflecting his love of hunting and his common touch, rather than as a statesman or military leader. This portrayal has been influential in shaping his popular image.[37]

Saigō Takamori's life and actions have been subject to numerous interpretations. He has been seen as a selfless patriot, a tragic hero, a reactionary feudalist, a principled conservative, and a champion of the oppressed.[38] His insistence on moral principles in politics, his loyalty, his courage, and his ultimate failure against the forces of modernization have contributed to his enduring appeal.[39] His story continues to be retold in various media, reflecting an ongoing engagement with his complex legacy and what he represents about Japanese identity and history. His image, often detached from the historical reality, serves as an "empty symbolic vessel" that can be filled with various meanings to suit contemporary ideological needs.[40]

انظر أيضاً

المراجع

- ^ Ravina 2004, pp. 4, 210.

- ^ Ravina 2004, pp. 4–5.

- ^ أ ب Yates 1995, p. 167.

- ^ Ravina 2004, p. 4.

- ^ Ravina 2010, pp. 695–696.

- ^ أ ب Ravina 2004, p. 5.

- ^ Ravina 2004, pp. 1–2.

- ^ أ ب Ravina 2004, p. 211.

- ^ أ ب Jansen 2000, p. 370.

- ^ Ravina 2004, pp. 34, 41.

- ^ Ravina 2004, p. 34.

- ^ Ravina 2004, pp. 87, 89.

- ^ Yates 1995, p. 44.

- ^ أ ب Ravina 2004, p. 89.

- ^ أ ب Ravina 2004, p. 108.

- ^ Yates 1995, pp. 44, 108.

- ^ أ ب ت Ravina 2004, p. 123.

- ^ أ ب Yates 1995, p. 123.

- ^ Ravina 2004, pp. 34, 123, (infobox).

- ^ Ravina 2004, pp. 4, 39, 171.

- ^ Yates 1995, p. 43.

- ^ Ravina 2004, p. 182.

- ^ أ ب ت Ravina 2004, p. 39.

- ^ أ ب Ravina 2004, p. 27.

- ^ Ravina 2004, pp. 7–11.

- ^ أ ب Yates 1995, p. 173.

- ^ Yates 1995, p. 1.

- ^ Ravina 2004, pp. 7–8.

- ^ Yates 1995, p. 13.

- ^ Ravina 2010, p. 692.

- ^ Ravina 2004, pp. 8–10.

- ^ Ravina 2004, pp. 10–11.

- ^ Jansen 2000, p. 326.

- ^ Ravina 2004, pp. 11–12.

- ^ Ravina 2004, p. 12.

- ^ Ravina 2004, p. i (caption), 7 (mention).

- ^ Yates 1995, p. 11.

- ^ Yates 1995, pp. 2–4, 182.

- ^ Yates 1995, pp. 181–182, 185–186.

- ^ Yates 1995, pp. 4, 186.

الأعمال المذكورة

- Jansen, Marius B. (2000). The Making of Modern Japan. Harvard University Press. doi:10.2307/j.ctvjf9vr7. ISBN 978-0-674-00991-2. JSTOR j.ctvjf9vr7.

- Ravina, Mark (2004). The Last Samurai: The Life and Battles of Saigō Takamori. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-471-08970-4.

- Ravina, Mark J. (2010). "The Apocryphal Suicide of Saigō Takamori: Samurai, "Seppuku", and the Politics of Legend". The Journal of Asian Studies. 69 (3): 691–721. doi:10.1017/S0021911810001518. ISSN 0021-9118. JSTOR 40929189. S2CID 155001706.

- Yates, Charles L. (1995). Saigō Takamori: The Man Behind the Myth. Kegan Paul International. ISBN 0-7103-0484-6.

للاستزادة

- Beasley, W.G. (1974) [1963]. The Modern History of Japan. New York City, NY: Praeger Publishers.

- Boyd, Richard; Ngo, Tak-Wing, eds. (2006). State Making in Asia. Routledge. ISBN 0-203-33898-7.

- Drea, Edward J. (2009). Japan's Imperial Army: Its Rise and Fall, 1953-1945. University Press of Kansas. ISBN 978-0-7006-1663-3.

- Esposito, Gabriele (2020). Japanese Armies 1868-1877: The Boshin War and Satsuma Rebellion. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 9781472837066.

- Samuels, Richard J. (2003). Machiavelli's Children: Leaders & Their Legacies In Italy & Japan. Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-3492-0.

- Sims, Richard (2001). Japanese Political History since the Meiji Renovation 1868-2000. Palgrave. ISBN 0-312-23915-7.

External links

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Pages using infobox military person with unknown parameters

- ساموراي

- جنرالات يابانيون

- مواليد 1827

- وفيات 1877

- قادة عسكريون يابانيون

- سياسيون يابانيون

- فولكلور ياباني

- People from Kagoshima

- Japanese swordfighters

- Japanese military leaders

- Japanese rebels

- Japanese revolutionaries

- Marshals of Japan

- Nobles of the Meiji Restoration

- People from Satsuma Domain

- Seppuku from Meiji era to present

- Japanese politicians

- Shimazu retainers

- People of the Boshin War

- Japanese folklore

- Suicides by sharp instrument in Japan

- Suicides by seppuku

- People killed in the Satsuma Rebellion

- Deified Japanese men

- 1870s suicides

- Japanese scholars of Yangming

- Anti-monarchists