ثورة العامة

| ثورة العامة Revolt of the Comuneros | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

إعدام عامة قشتالة، بريشة أنطونيو گيسبرت (1860) | |||||||

| |||||||

| المتحاربون | |||||||

| المتمردون من العامة | القشتاليون الملكيون | ||||||

| القادة والزعماء | |||||||

|

Juan de Padilla, Juan Bravo, Francisco Maldonado, Antonio de Acuña, Pedro Girón, ماريا پاتشيكو |

شارل الخامس، الامبراطور الروماني المقدس؛ أدريان من أوترخت، الوصي على قشتالة؛ Íñigo Fernández, كونستابل قشتالة؛ Fadrique Enríquez, أميرال قشتالة | ||||||

| 13 فبراير 1522 يُستخدَم أيضاً كتاريخ نهاية؛ انظر ثورة 1522. | |||||||

ثورة العامة (الكـُمونـِروس) (إسپانية: Guerra de las Comunidades de Castilla، "حرب مدن قشتالة") كانت انتفاضة قام بها أهالي قشتالة على حكم شارل الخامس وادارته بين 1520 و 1521. وفي أوجها، سيطر المتمردون على قلب قشتالة، فحكموا مدن بلد الوليد، توردسياس، وطليطلة.

The revolt occurred in the wake of political instability in the Crown of Castile after the death of Queen Isabella I in 1504. Isabella's daughter Joanna succeeded to the throne. Due to Joanna's alleged mental instability, Castile was ruled by the nobles and her father, King Ferdinand II of Aragon, as a regent. After Ferdinand's death in 1516, Joanna's sixteen-year-old son Charles was proclaimed king of both Castile and Aragon. Charles had been raised in the Netherlands with little knowledge of Castilian. He arrived in Spain in October 1517 accompanied by a large retinue of Flemish nobles and clerics. These factors resulted in mistrust between the new king and the Castilian social elites, who could see the threat to their power and status.

In 1519, Charles was elected Holy Roman Emperor. He departed for Germany in 1520, leaving the Dutch cardinal Adrian of Utrecht to rule Castile in his absence. Soon, a series of anti-government riots broke out in the cities, and local city councils (Comunidades) took power. The rebels chose Charles' own mother, Queen Joanna, as an alternative ruler, hoping they could control her madness. The rebel movement took on a radical anti-feudal dimension, supporting peasant rebellions against the landed nobility. On April 23, 1521, after nearly a year of rebellion, the reorganized supporters of the emperor struck a crippling blow to the comuneros at the Battle of Villalar. The following day, rebel leaders Juan López de Padilla, Juan Bravo, and Francisco Maldonado were beheaded. The army of the comuneros fell apart. Only the city of Toledo kept alive the rebellion led by María Pacheco, until its surrender in October 1521.

The character of the revolution is a matter of historiographical debate. According to some scholars, the revolt was one of the first modern revolutions, notably because of the anti-noble sentiment against social injustice and its basis on ideals of democracy and freedom. Others consider it a more typical rebellion against high taxes and perceived foreign control. From the 19th century onwards, the revolt has been mythologized by various Spaniards, generally liberals who drew political inspiration from it. Conservative intellectuals have traditionally adopted more pro-Imperial stances toward the revolt, and have been critical of both the motives and the government of the comuneros. With the end of Franco's dictatorship and the establishment of the autonomous community of Castile and León, positive commemoration of the Comunidades has grown. April 23 is now celebrated as Castile and León Day, and the incident is often referred to in Castilian nationalism.

كنيسة سان پابلو في بلد الوليد، مقر كورتيس انعقد في 1518. نشأت الاحتجاجات حين سُمِّيَ المستشار الفلمنكي جان دى سوڤاج رئيساً له، وهو ما سبق المشاكل. |

الأصول

كانت نعمة مشكوكاً فيها لإسبانيا أن يصبح الملك شارل الأول (1516-56) الإمبراطور شارل الخامس (1519-58). وولد وتربى في الفلاندرز: وتعلم مناهج الحياة الفلمنكية، واكتسب الأذواق الفلمنكية، إلى أن تغلبت عليه روح إسبانيا في سنواته. ولم يكن في وسع الملك إلا أن يصبح جزءاً صغيراً من الإمبراطور، الذي كان مشغولاً تماماً بالإصلاح الديني والبابوية وسليمان وبارباروسا وفرانسيس الأول، وشكا الإسبان أنه لم يمنحهم إلا القليل من وقته، وأنه أنفق الكثير من مواردهم البشرية والمادية في المحلات التي كانت في الظاهر لا تهم المصالح الأسبانيّة، وكيف كان في وسع إمبراطور أن يتعاطف مع نظم جماعية جعلت إسبانيا تتمتع بنصف ديمقراطية، قبل مجيء فرديناند الكاثوليكي، وكانت تتوق كثيراً إلى أن تستعيدها؟

تمدد الثورة

وقام بأول زيارة لمملكته (1517) ولم تكسبه حب أحد، وعلى الرغم من مضي عشرين شهراً عليه وهو ملك، فإنه كان لا يزال لا يعرف الإسبانيّة وكان عزله الفظ لأكسيمينس صدمة للدماثة الإسبانية. وجاء يحيط فلمنكيون، ظنوا إسبانيا بلداً همجياً تنتظر مَن يحلبها. وعين الملك البالغ من العمر سبعة عشر عاماً هذه الديدان الطبية في أعلى المناصب، ولم تخفِ المجالس التشريعية الإقليمية المختلفة التي يسيطر عليها صغار النبلاء، نفورها وعدم رضاها عن ملك أجنبي. ورفض المجلس التشريعي في قشتالة أن يعترف له باللقب، ثم اعترف به على كره منه حاكماً، تشترك معه في الحكم أمه المعتوهة جوانا، وجعله يفهم أنه لابد من أن يتعلم الإسبانيّة، ويعيش في إسبانيا، وألا يعين مزيداً من الأجانب في أي منصب. وقدمت المجالس التشريعية طلبات مماثلة. ووسط مظاهر الإذلال التي تعرض لها شارل تلقى أنباء بأنه انتخب إمبراطوراً، وأن ألمانيا كانت تدعوه للحضور لكي يتوج. وعندما سأل المجلس التشريعي في بلد الوليد (وكانت وقتذاك العاصمة) أن يمول الرحلة مني بالفشل والخيبة، وساد هرج هدد حياته. وحصل آخر الأمر على المال من المجلس التشريعي في كورونا وأسرع إلى الفلاندرز. ولكي يجعل الأمور محفوفة بالمخاطر أضعافاً مضاعفة أرسل نواباً corregidores لحماية مصالحه في المُدن، وترك مربيه السابق أدريان كاردينال أترخت نائباً له في إسبانيا. وثارت البلديات الإسبانيّة واحدة وراء الأخرى في "ثورة أعضاء الكومون" ونفوا النواب corregidores وقتلوا بعض النواب الذين صوتوا بالموافقة على منح أموال لشارل، وتحالفوا فيما يعرف باسم Santa Communidad الذي تعهد بالإشراف على الملك. وانضم النبلاء ورجال الكنيسة وأوساط الناس إلى الحركة ونظموا في أفيلا (أغسطس سنة 1520) الـ Santa Iunta أو الاتحاد المقدس ليكون بمثابة حكومة مركزية. وطالبوا بضرورة اشتراك المجالس التشريعية مع المجالس الملكية في اختيار نائب الملك، وعدم شنَّ حرب بغير موافقة المجالس التشريعية، وألا يحكم المدينة النواب بل يحكمها قضاة، أو عمد يختارهم المواطنون(29). ودافع أنطونيو دى أكونيا أسقف سمورة علناً عن قيام جمهورية، وحول أتباعه من رجال الأكليروس إلى محاربين ثوريين، وقدم موارد أسقفية للثورة. وعين خوان دى پاديا، وهو نبيل من طليطلة، قائداً لقوات الثوار. فقادها لتستولي على نورديسياس، وأخذ خوانا لا لوكا رهينة، وحثها على أن توقع وثيقة، تخلع فيها شارل، وتعين نفسها ملكة، وكانت عاقلة في جنونها، فرفضت.

فرض الحظر على سگوڤيا

حرق مدينا دل كامپو

طغمة توردسياس

نطاق التمرد

الرد الشعبي والحكومي

ولم يكن لدى أدريان ما يكفي من الجند لقمع الثورة، فاستغاث بشارل وطلب منه العودة، وألقى تبعة قيام الثورة صراحة على تحكم الملك وحكمه الغيابي. ولم يحضر شارل، ولكنه وجد هو أو مستشاروه سبيلاً لإشاعة الانقسام والانتصار. فقد حذر النبلاء أن الثورة كانت تهديداً لطبقات أصحاب الأملاك وللتاج على السواء، والحق أن الطبقات العاملة، التي ظلمت منذ عهد بعيد بالأجور الثابتة، والعمل سخرة، وتحريم الاتحاد، كانت قد استولت من قبل على السلطة في عدة مُدن. وفي بلنسية والمنطقة المجاورة لها قبض الجرمانيا Germania أو اخوة أبناء الطوائف الحرفية على الزمام، وسيطروا على لجان العمال. وكانت هذه الدكتاتورية البروليتارية نقية على غير العادة، وفرضت على آلاف المغاربة الذين ظلوا في المقاطعة أن يختاروا بين التعميد والموت. وقتل آلاف من الذين رفضوا في عناد(30). وثار العامة في ماجوركا، الذين عاملهم سادتهم كالعبيد، ثورة مسلحة، وخلعوا الحاكم المعين من قبل الملك، وذبحوا كل نبيل لم يستطع أن يفلت منهم. وتخلت كثير من المُدن عن روابطها مع الإقطاعيين ومستحقاتها لهم، وفي مدريد وسجونزا ووادي الحجارة أقصت الحكومة البلدية الجديدة كل النبلاء والأعيان من المناصب، وقتل الأشراف هنا وهناك، وفرض الاتحاد Iunta ضرائب على أملاك النبلاء السابق إعفاؤها. وأصبح النهب عاماً، وأحرق العامة قصور النبلاء وذبح النبلاء العامة. وانتشر الصراع بين الطبقات في أرجاء إسبانيا.

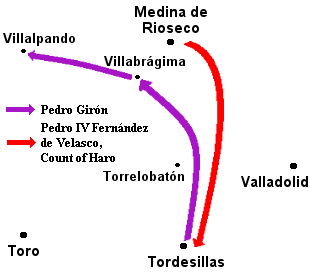

وقضت الثورة على نفسها بالتوسع في أهدافها، توسعاً جاوز حدود طاقاتها، وانقلب عليها النبلاء، وحشدوا قواتهم، وتعاونوا مع قوات الملك، واستولوا على بلنسية، وأطاحوا بالحكومة البروليتارية، بعد أيام سقط فيها قتلى من الجانبين (1521)، وانقسم جيش الثوار، عندما بلغت الأزمة ذروتها، إلى فرقتين متنافستين بقيادة باديلا ودون بدرو جيرون، وانقسمت الجماعة السياسية إلى أحزاب، يناصب بعضها بعضاً العداء، وواصلت كل مقاطعة ثورتها، دون تآزر مع باقي المقاطعات.

وانطلق جيرون، وانضم إلى الملكيين الذين استولوا من جديد على تورديسلاس وجوانا. أما جيش باديلا الذي تضاءل عدد جنوده فقد هزم هزيمة منكرة في فيلالار، وأعدم باديلا. وعندما عاد شارل إلى إسبانيا (يوليو سنة 1522) ومعه 4.000 جندي ألماني، كان النبلاء قد فازوا بالنصر، وقد أضعف النبلاء والعامة بعضهم بعضاً إلى حد أنه استطاع أن يتغلب على البلديات والطوائف الحرفية، ويروض المجالس التشريعية، ويوطد أركان ملكية تكاد تكون مطلقة. وقد قمعت الحركة الديمقراطية تماماً بحيث ظل كل العامة الأسبان خائفين خاضعين، حتى القرن التاسع عشر. وخفف شارل سلطته بالدماثة، وأحاط نفسه بالنبلاء، وتعلم الحديث بلغة إسبانية سليمة، وسرت إسبانيا عندما علق قائلاً إن الإيطالية هي اللغة اللائقة لكي تتحدث بها النساء، والألمانية هي لغة الأعداء، والفرنسية لغة الأصدقاء، والإسبانية لغة الرب(31).

معركة توردسياس

النزاع على الزعامة

المبادرات العسكرية في بلنسية وبرغش

حملات المتمردين في مطلع 1521

قرار پاديا حول خطوة المتمردين المقبلة

حملة أكونيا الجنوبية

معركة بيالار

نهاية الحرب

After the Battle of Villalar, the towns of northern Castile soon succumbed to the king's troops, with all its cities returning their allegiance to the king by early May. Only Madrid and Toledo kept their Comunidades alive.[3]

مقاومة طليطلة

التأثير اللاحق

The revolt, fresh in the memory of Spain, is referenced in several literary works during Spain's Golden Age. Don Quixote references the rebellion in a conversation with Sancho, and Francisco de Quevedo uses the word "comunero" as a synonym for "rebel" in his works.[4][5]

انظر أيضاً

- List of people associated with the Revolt of the Comuneros

- Military history of the Revolt of the Comuneros

- Revolt of the Brotherhoods

- Spanish conquest of Iberian Navarre

- Italian War of 1521–1526

ملاحظات

- ^ This article uses the term "tax" to encompass a variety of revenue-raising methods the government used. Briefly, servicios were flat monetary grants paid to the treasury; the encabezamiento was a portion of the sales tax towns collected sent to the government; and the cruzada ("crusade") was a special and semi-voluntary contribution that counted as an indulgence and was generally used for war against the Muslims. Charles wanted to abolish the lenient encabezamiento and return to an older and harsher system of direct royal control of tolls, pasturage fees, and the like. He also requested large servicios at the Cortes he held. Part of the revenue problem the government had was that income from the cruzada had fallen greatly since the Reconquista had finished in 1492.[7]

- ^ Junta, meaning "Congress" or "Assembly," did not yet have the negative connotation of "Oligarchical military dictatorship" in the 16th century.

- ^ There exists a theory that Girón's errors were in fact an intentional betrayal of the comuneros. Considering his moderate stance and later pardon by the government, historians such as Seaver consider this possible, but unlikely.[1]

مراجع

- This article incorporates text translated from the Spanish Wikipedia article Guerra de las Comunidades de Castilla, licensed under the قالب:Srlink.

- ^ أ ب خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةseaver200 - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةseaver333 - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةseaver339 - ^ Cervantes, Miguel de (1615). "Volume 2, Chapter 43". Don Quixote de la Mancha (in Spanish). Rodolfo Schevill and Adolfo Bonilla; digital form and editing by Fred F. Jehle. p. 61. ISBN 0-394-90892-9. Retrieved 2008-09-27.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ Pérez 2001, p. 236.

- ^ "20.000 personas celebran en Villalar la fiesta de Castilla y León" (in Spanish). Cadena SER. 2004-04-23. Retrieved 2008-11-12.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةhal147

ببليوگرافيا

English language sources:

- Haliczer, Stephen (1981). The Comuneros of Castile: The Forging of a Revolution, 1475-1521. Madison, Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 0-299-08500-7.

- Lynch, John (1964). Spain under the Habsburgs. Vol. (vol. 1). New York: Oxford University Press.

- Miller, Townsend (1963). The Castles and the Crown. New York: Coward-McCann.

- Seaver, Henry Latimer (1966) [1928]. The Great Revolt in Castile: A Study of the Comunero Movement of 1520-1521. New York: Octagon Books.

Spanish and other language sources:

- Díez, José Luis (1977). Los Comuneros de Castilla (in Spanish). Madrid: Editorial Mañana. ISBN 84-7421-025-9. OCLC 4188611.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - Guilarte, Alfonso María (1983). El obispo Acuña: Historia de un comunero (in Spanish). Valladolid: Ambito. ISBN 84-86047-13-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - Maravall, José Antonio (1963). Las comunidades de Castilla: Una primera revolución moderna (in Spanish). Madrid: Revista de Occidente. OCLC 2182035.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - Gutiérrez Nieto, Juan Ignacio (1973). Las comunidades como movimiento antiseñorial: La formación del bando realista en la Guerra Civil Castellana de 1520-1521 (in Spanish). Barcelona: Editorial Planeta. ISBN 84-320-7801-1.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: checksum (help); Unknown parameter|ignore-isbn-error=ignored (|isbn=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - Pérez, Joseph (1998) [1970]. La révolution des "Comunidades" de Castille, 1520-1521 (in French in 1970 edition; Spanish in 1978 translation). Bordeaux: Institut d'études ibériques et ibéro-américaines de l'Université de Bordeaux. ISBN 84-323-0285-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - Pérez, Joseph (2001). Los Comuneros (in Spanish). Madrid: La Esfera de los Libros, S.L. ISBN 84-9734-003-5.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link)

- Articles containing إسپانية-language text

- Pages using Lang-xx templates

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- CS1 errors: unsupported parameter

- CS1 errors: ISBN

- ثورة العامة

- نزاعات عقد 1520

- عقد 1520 في إسپانيا

- حروب إسپانيا

- ثورات إسپانيا

- تمردات القرن 16

- شارل الخامس، الإمبراطور الروماني المقدس

- Conflicts in 1520

- Conflicts in 1521

- History of the province of Valladolid

- Joanna of Castile

- Rebellions in Spain

- Revolutions in Spain

- Tordesillas

- Wars involving Spain