الحرب القذرة

الحرب القذرة (إسپانية: Guerra Sucia) تشير إلى عنف رعته الدولة في الأرجنتين تجاه الآلاف من المتشددين اليساريين, بما في ذلك الثوار اليساريين, أعضاء نقابات العمال شاملة جميع الأحزاب اليسارية[1] والمؤيديين[2]، نفذت في المقام الأول عن طريق جيش جورج فيديلا وبدأت في 24 مارس 1976، واستمرت حتى عودة الحكم المدني في 1983.

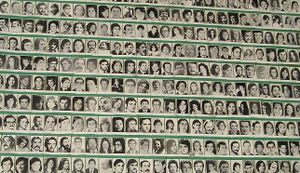

ضحايا العنف ضموا ما يُقدر بنحو 15,000 - 30,000 ناشط ومسلح يساري، بما فيهم نقابيون وطلبة وصحفيون وماركسيون وثوار پيرونيون ومن يشاع عنهم أنهم متعاطفون. بعض من 10,000 "مختفي" كان يُعتقد أنهم ثوار مونتونيروس (MPM) والجيش الثوري الشعبي (ERP).[3][4][5] وكان الثوار مسؤلون عن إيقاع 6,000 ضحية في صفوف العسكر والشرطة والسكان المدنيين، حسب مقالة في مجلة ناشيونال جيوگرافيك في منتصف الثمانينات.[6]

أصل المصطلح

جزء من سلسلة عن |

|---|

| تاريخ الأرجنتين |

|

عودة البيرونية

حكومة ايزابل مارتين دي بيرون

"مراسيم الإبادة"

الغارة في سانتا فى (مارس 1975)

استيلاء العسكرية على السلطة

False flag actions by SIDE agents

انتهاكات حقوق الإنسان 1976 - 1983

The disappeared held under State of Siege Powers (PEN)

غزو جزر فوكلاندز

مكافحة الشيوعية

التدخل الأمريكي

التدخل الكوبي

"الصلة الفرنسية"

Investigating French military influence in Argentina, in 2003 French journalist Marie-Monique Robin found the original document proving that a 1959 agreement between Paris and Buenos Aires initiated a "permanent French military mission" in Argentina and reported on it (she found the document in the archives of the Quai d'Orsay, the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs). The mission was formed of veterans who had fought in the Algerian War and it was assigned to the offices of the chief of staff of the Argentine Armed Forces. It was continued until 1981, date of the election of socialist François Mitterrand.[7]

After release of her documentary film, Escadrons de la mort, l'école française in 2003, which explored the French connection with South American nations, in August 2003 Robin said in an interview with L'Humanité newspaper: "French have systematized a military technique in urban environment which would be copied and pasted to Latin American dictatorships".[8] She noted that the French military had systematized the methods they used to suppress the insurgency during the 1957 Battle of Algiers and exported them to the War School in Buenos Aires.[7] Roger Trinquier's famous book on counter-insurgency had a very strong influence in South America. In addition, Robin said she was shocked to learn that the DST French intelligence agency gave DINA the names of refugees who returned to Chile (Operation Retorno) from France during their counterinsurgency. All of these Chileans have been killed: "Of course, this puts in cause [sic – this makes responsible] the French government, and Giscard d'Estaing, then President of the Republic. I was very shocked by the duplicity of the French diplomatic position which, on one hand, received with open arms the political refugees, and, on the other hand, collaborated with the dictatorships".[8]

In response, on 10 September 2003 Green members of parliament Noël Mamère, Martine Billard and Yves Cochet filed a request to form a Parliamentary Commission to examine the "role of France in the support of military regimes in Latin America from 1973 to 1984" before the Foreign Affairs Commission of the National Assembly, presided by Edouard Balladur (UMP). Apart from Le Monde, French newspapers did not report this request.[9] UMP deputy Roland Blum, in charge of the Commission, refused to let Marie-Monique Robin testify on this topic. The Commission in December 2003 published a 12-page report claiming that the French had never signed a military agreement with Argentina.[10][11]

When Minister of Foreign Affairs Dominique de Villepin travelled to Chile in February 2003, he claimed that no co-operation between France and the military regimes had occurred.[12] People in Argentina were outraged when they saw the 2003 film, which included three generals defending their actions during the Dirty War. Due to public pressure, President Néstor Kirchner ordered the military to bring charges against the three for justifying the crimes of the dictatorship. They were Albano Hargindeguy, Reynaldo Bignone and Ramón Genaro Díaz Bessone.[13]

The next year, Robin published her book under the same title Escadrons de la mort: l'école française (Death Squads: The French School, 2004), revealing more material. She showed how Valéry Giscard d'Estaing's government secretly collaborated with Videla's junta in Argentina and with Augusto Pinochet's regime in Chile.[14][15] Alcides Lopez Aufranc was among the first Argentine officers to go in 1957 to Paris to study for two years at the Ecole de Guerre military school, two years before the Cuban Revolution and when no Argentine guerrillas existed.[7]

In practice, declared Robin to Página/12, the arrival of the French in Argentina led to a massive extension of intelligence services and of the use of torture as the primary weapon of the anti-subversive war in the concept of modern warfare.[7]

The annihilation decrees signed by Isabel Perón had been inspired by French texts. During the Battle of Algiers, the police forces were put under the authority of the Army. 30,000 persons were "disappeared". In Algeria. Reynaldo Bignone, named President of the Argentine junta in July 1982, said in Robin's film: "The March 1976 order of battle is a copy of the Algerian battle".[7] The same statements were made by Generals Albano Harguindeguy, Videla's Interior Minister; and Diaz Bessone, former Minister of Planification and ideologue of the junta.[16] The French military would transmit to their Argentine counterparts the notion of an "internal enemy" and the use of torture, death squads and quadrillages (grids).

Marie-Monique Robin also demonstrated that since the 1930s, there had been ties between the French far-right and Argentina, in particular through the Catholic fundamentalist organisation Cité catholique, created by Jean Ousset, a former secretary of Charles Maurras, the founder of the royalist Action Française movement. La Cité edited a review, Le Verbe, which influenced militaries during the Algerian War, notably by justifying the use of torture. At the end of the 1950s, the Cité catholique founded groups in Argentina and organised cells in the Army. It greatly expanded during the government of General Juan Carlos Onganía, in particular in 1969.[7] The key figure of the Cité catholique in Argentina was priest Georges Grasset, who became Videla's personal confessor. He had been the spiritual guide of the Organisation armée secrète (OAS), the pro-French Algeria terrorist movement founded in Franquist Spain.

Robin believes that this Catholic fundamentalist current in the Argentine Army contributed to the importance and length of the French-Argentine co-operation. In Buenos Aires, Georges Grasset maintained links with Archbishop Marcel Lefebvre, founder of Society of St. Pius X in 1970, who was excommunicated in 1988. The Society of Pius-X has four monasteries in Argentina, the largest one in La Reja. A French priest from there said to Marie-Monique Robin: "To save the soul of a Communist priest, one must kill him." Luis Roldan, former Secretary of Cult under Carlos Menem, President of Argentina from 1989 to 1999, was presented by Dominique Lagneau, the priest in charge of the monastery, to Robin as "Mr. Cité catholique in Argentina". Bruno Genta and Juan Carlos Goyeneche represent this ideology.[7]

Antonio Caggiano, archbishop of Buenos Aires from 1959 to 1975, wrote a prologue to Jean Ousset's 1961 Spanish version of Le Marxisme-léninisme. Caggiano said that "Marxism is the negation of Christ and his Church" and referred to a Marxist conspiracy to take over the world, for which it was necessary to "prepare for the decisive battle".[17] Together with President Arturo Frondizi (Radical Civic Union, UCR), Caggiano inaugurated the first course on counter-revolutionary warfare in the Higher Military College.[بحاجة لمصدر] (Frondizi was eventually overthrown for being "tolerant of Communism").[بحاجة لمصدر]

By 1963, cadets at the Navy Mechanics School started receiving counter-insurgency classes. They were shown the film The Battle of Algiers, which showed the methods used by the French Army in Algeria. Caggiano, the military chaplain at the time, introduced the film and added a religiously oriented commentary to it. On 2 July 1966, four days after President Arturo Umberto Illia was removed from office and replaced by the dictator Juan Carlos Onganía, Caggiano declared: "We are at a sort of dawn, in which, thanks to God, we all sense that the country is again headed for greatness".[بحاجة لمصدر]

Argentine Admiral Luis María Mendía, who had started the practice of "death flights", testified in January 2007 before Argentine judges, that a French intelligence agent, Bertrand de Perseval, had participated in the abduction of the two French nuns, Léonie Duquet and Alice Domont. Perseval, who lives today in Thailand, denied any links with the abduction. He has admitted being a former member of the OAS and having escaped from Algeria after the March 1962 Évian Accords put an end to the Algerian War (1954–1962).

During the 2007 hearings, Luis María Mendía referred to material presented in Robin's documentary, titled The Death Squads – the French School (2003). He asked the Argentine Court to call numerous French officials to testify to their actions: former French President, Valéry Giscard d'Estaing, former French Premier Pierre Messmer, former French embassador to Buenos Aires Françoise de la Gosse and all officials in place in the French embassy in Buenos Aires between 1976 and 1983.[18] Besides this "French connection", María Mendía also charged former head of state Isabel Perón and former ministers Carlos Ruckauf and Antonio Cafiero, who had signed the "anti-subversion decrees" before Videla's 1976 coup. According to Graciela Dalo, a survivor of the ESMA interrogations, Mendía was trying to establish that these crimes were legitimate, as the 1987 Obediencia Debida Act claimed them to be and further that the ESMA actions had been committed under Isabel Perón's "anti-subversion decrees" (which would give them a formal appearance of legality, although torture is forbidden by the Argentine Constitution).[19] Alfredo Astiz also referred to the "French connexion" when testifying in court.[20]

بعثة الحقائق 1984 التمرد العسكري وإلغاء قرارات العفو

الجدل مستمر

تقديرات الضحايا

مساهمة الكنيسة الكاثوليكية

كتب

- Dirty Secrets, Dirty War: The Exile of Editor Robert J. Cox, by David Cox (2008).

- The Ministry of Special Cases, by Nathan Englander (2007), novel.

- La Historia Official (English: The Official Story), by Nicolás Márquez (2006), revisionist critique

- Guerrillas and Generals: The Dirty War in Argentina, by Paul H. Lewis (2001).

- God's Assassins: State Terrorism in Argentina in the 1970s by M. Patricia Marchak (1999).

- A Lexicon of Terror: Argentina and the Legacies of Torture, by Marguerite Feitlowitz (1999).

- Una sola muerte numerosa (English: A Single, Numberless Death), by Nora Strejilevich (1997).

- The Flight: Confessions of an Argentine Dirty Warrior, by Horacio Verbitsky (1996).

- Argentina's Lost Patrol: Armed Struggle, 1969–1979, by María José Moyano (1995).

- Dossier Secreto: Argentina's Desaparecidos and the Myth of the "Dirty War", by Martin Edwin Anderson (1993).

- Argentina's "Dirty War": An Intellectual Biography, by Donald C. Hodges (1991).

- Behind the Disappearances: Argentina's Dirty War Against Human Rights and the United Nations, by Iain Guest (1990).

- The Little School: Tales of Disappearance & Survival in Argentina, by Alicia Partnoy (1989).

- Argentina, 1943–1987: The National Revolution and Resistance, by Donald C. Hodges (1988).

- Soldiers of Perón: Argentina's Montoneros, by Richard Gillespie (1982).

- Guerrilla warfare in Argentina and Colombia, 1974–1982, by Bynum E. Weathers, Jr. (1982).

- Prisoner without a Name, Cell without a Number, by Jacobo Timerman (1981).

- Guerrilla politics in Argentina, by Kenneth F. Johnson (1975).

فيلم

- Cautiva (2003). Directed by Gaston Biraben. Movie related to the "stolen babies" case

- Imagining Argentina (2003). Directed by Christopher Hampton.

- Olympic Garage (1999). Directed by Marco Bechis.

- The Official Story (1985). Directed by Luis Puenzo. Movie related to the "stolen babies" case

- Kamchatka (2002). Directed by Marcelo Piñeyro.

- The Disappeared (2007). Directed by Peter Sanders.[21]

- Los Escuadrones De La Muerte (the Death Squadron, Escadrons de la mort), l'école française, by Marie-Monique Robin (book and film)[22]

- Our Disappeared / Nuestros Desaparecidos (2008). Directed by Juan Mandelbaum.[23]

- Night of the Pencils (1986) Directed by Héctor Olivera. [24]

- Crónica de una fuga (2006). Directed by Israel Adrián Caetano. Movie related to the "Mansión Sere" case.

انظر أيضا

|

|

المصادر

- ^ Argentina’s Dirty War. Guy Gugliotta.

- ^ Orphaned in Argentina's dirty war, man is torn between two families. Washington Post. February 11, 2010.

- ^ "El ex líder de los Montoneros entona un «mea culpa» parcial de su pasado", El Mundo, 4 May 1995

- ^ A 32 años de la caída en combate de Mario Roberto Santucho y la Dirección Histórica del PRT-ERP. Cedema.org.

- ^ ''Determinants Of Gross Human Rights Violations By State And State-Sponsored Actors In Brazil, Uruguay, Chile, And Argentina (1960–1990)', Wolfgang S. Heinz & Hugo Frühling, p. 626, Springer, 1999, Google Books

- ^ National Geographic, Volume 170, p. 247, National Geographic Society, 1986

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ "Argentine – 'Escadrons de la mort, l’école française' ", interview with Marie-Monique Robin published by RISAL, 22 October 2004 available in French & Spanish ("Los métodos de Argel se aplicaron aquí", Página/12, 13 October 2004

- ^ أ ب L’exportation de la torture Archived 5 يوليو 2005 at the Wayback Machine, interview with Marie-Monique Robin in L'Humanité, 30 August 2003 (بالفرنسية)

- ^ MM. Giscard d'Estaing et Messmer pourraient être entendus sur l'aide aux dictatures sud-américaines, Le Monde, 25 September 2003 (بالفرنسية)

- ^ « Série B. Amérique 1952–1963. Sous-série : Argentine, n° 74. Cotes : 18.6.1. mars 52-août 63 ».

- ^ Rapport Fait Au Nom de La Commission des Affaires Étrangères Sur La Proposition de Résolution (n° 1060), tendant à la création d'une commission d'enquête sur le rôle de la France dans le soutien aux régimes militaires d'Amérique latine entre 1973 et 1984, par M. Roland BLUM, French National Assembly (بالفرنسية)

- ^ Argentine : M. de Villepin défend les firmes françaises, Le Monde, 5 February 2003 (بالفرنسية)

- ^ J. Patrice McSherry, Review: Death Squadrons: The French School. Directed by Marie-Monique Robin., The Americas 61.3 (2005) 555-556, via Project MUSE, accessed 30 April 2016

- ^ Marie-Monique Robin, Escadrons de la mort : l'école française, Paris: Éditions La Découverte, 2004. ISBN 2-7071-4163-1

- ^ Conclusion of Marie-Monique Robin's Escadrons de la mort, l'école française (بالفرنسية)

- ^ "Torture : l’école française", Marie-Monique Robin, interview first published by Rouge, September 2005 (بالفرنسية)

- ^ Antonio Caggiano, Introduction to Jean Ousset, Le Marsisme-léninisme (1961 Spanish edition.

- ^ "Disparitions : un ancien agent français mis en cause", Le Figaro, 6 February 2007 (بالفرنسية)

- ^ "Impartí órdenes que fueron cumplidas", Página/12, 2 February 2007 (بالإسپانية)

- ^ Astiz llevó sus chicanas a los tribunales, Página/12, 25 January 2007 (بالإسپانية)

- ^ http://www.thedisappearedmovie.com

- ^ http://www.mefeedia.com/entry/2926696/ ISBN 950072684X

- ^ http://www.ourdisappeared.com

- ^ http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0193355/

وصلات خارجية

- Proyecto Desaparecidos/Project Disappeared

- Unearthing Mysteries of Argentina's "Dirty War" - slideshow by CNN

- War Diary of Brigadier-General Acdel Vilas

- 1984 Report of the National Commission on the Disappearance of Persons

- Old Ideas in New Discourses: "The War Against Terrorism" and Collective Memory in Uruguay and Argentina

- Consortium article

- Information from the Vanished Gallery

- (بالإسپانية) 24 de marzo — Del horror a la esperanza — Official website of the Memorial Day, with timeline and resources

- A Serene Advocate for Chile’s Disappeared by Alexei Barrionuevo, The New York Times, January 22, 2010