بطارية الزنك-الهواء

| الطاقة المحددة | 470 (جزئياً)، 1370 (نظرياً) و.س/كگ[1][2] (1.692, 4.932 MJ/kg) |

|---|---|

| كثافة الطاقة | 1480-9780 س.و/ل[citation needed] (5.328–35.21 م.ج/ل) |

| القدرة المحددة | 100 واط/كگ[3][4] |

| جهد الخلية الإسمي | 1.65 ڤولت |

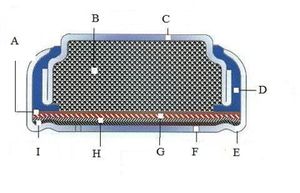

بطاريات الزنك-الهواء Zinc–air batteries (غير قابلة للشحن)، وبطاريات الوقود الزنك-الهواء zinc–air fuel cells (القابلة للشحنة آلياً)، هي بطاريات كهربية-كيميائية تعمل عن طريق الزنك المؤكسد بالأكسجين من الهواء. تتميز هذه البطاريات بكثافات الطاقة عالية وقلة تكلفة الانتاج. تتراوح أحجامها بين بطاريات الساعات وسماعات الأذن الصغيرة، والبطاريات الأكبر المستخدمة في الكاميرات والتي كانت تعمل ببطاريات الزئبق، إلى البطاريات الضخمة التي تستخدم في دفع المراكب الكهربائية.

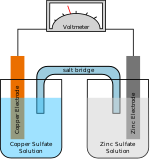

في التشغيل، تشكل كتلة جسيمات الزنك المصعد، الذي يتشبع بكهربل. يتفاعل الأكسجين من الهواء في المهبط ويشكل أيونات هيدروكسيلية التي تنتقل إلى عجينة الزنك وتشكل الزنكات (Zn(OH)2−4)، فتتطلق الإلكترونات لتنتقل إلى المهبط. يضمحل الزنكات إلى أكسيد الزنك ويرجع الماء إلى الكهرل. يعاد تدوير الماء والهيدروكسيلات من المصعد في المهبط، لذلك، فالماء لا يستهلك. تنتج التفاعلات 1.65 ڤولت نظرياً، لكنها تقل إلى 1.35-1.4 ڤولت في البطاريات المتوافرة.

لبطاريات الزنك-الهواء بعض خصائص بطاريات الوقود وكذلك البطاريات: الزنك هووقود، معدل التفاعل يمكن التحكم فيه عن طريق تدفق الهواء المتفاوت، وعجينة الزنك/الكهرل المؤكسدة يمكن استبدالها بعجينة جديدة.

يمكن استخدام بطاريات الزنك-الهواء لتحل محل خلايا الزئبق المتوفقة بقدرة 1.35 ڤولت (بالرغم من أن عمر تشغيلها أقصر بشكل ملحوظ)، والتي كان يشيع استخدامها في السبعينيات والثمانينيات في كاميرات التصوير.

تشمل التطبيقات المستقبلية المحتملة لهذا النوع من البطاريات انتشارها كبطاريات مركبات كهربائية واستخدامها في أنظمة تخزين الطاقة في المرافق.

التاريخ

The effect of oxygen was known early in the 19th century when wet-cell Leclanche batteries absorbed atmospheric oxygen into the carbon cathode current collector. In 1878 a porous platinized carbon air electrode was found to work as well as the manganese dioxide (MnO 2) of the Leclanche cell. Commercial products began to be made on this principle in 1932 when George W. Heise and Erwin A. Schumacher of the National Carbon Company built cells,[5] treating the carbon electrodes with wax to prevent flooding. This type is still used for large zinc–air cells for navigation aids and rail transportation. However, the current capacity is low and the cells are bulky.

Large primary zinc–air cells such as the Thomas A. Edison Industries Carbonaire type were used for railway signaling, remote communication sites, and navigation buoys.These were long-duration, low-rate applications. Development in the 1970s of thin electrodes based on fuel-cell research allowed application to small button and prismatic primary cells for hearing aids, pagers, and medical devices, especially cardiac telemetry.[6]

معادلات التفاعل

المعادلات الكيميائية التالية لبطاريات الزنك-الهواء:[2]

- المصعد: Zn + 4OH– → Zn(OH)42– + 2e– (E0 = -1.25 V)

- السائل: Zn(OH)42– → ZnO + H2O + 2OH–

- المهبط: 1/2 O2 + H2O + 2e– → 2OH– (E0 = 0.34 V pH=11)

- الإجمالي: 2Zn + O2 → 2ZnO (E0 = 1.59 V)

نسبة القدرة-الحجم

لبطاريات الزنك-الهواء معدل قدرة أعلى قياساً للحجم (والوزن)، أكبر من الأنواع الأخرى من البطاريات لأن الهواء القادم من الغلاف الجوي هو أحد المواد المتفاعلة في البطارية. الهواء غير معبأ في البطارية، ولذلك فهذه البطارية يمكن أن تستخدم المزيد من الزنك في المصعد أكثر من البطارية التي تستلزم أن يجب أن يتوافر بها، على سبيل المثال، ثاني أكسيد المنجنيز. يزيد هذا من قدرة البطارية قياساً لوزنها. مثال أكثر تحديدأً، بطارية الزنك-الهواء بقطر 11.6 مم وطول 5.4 مم من أحد المصانع قدرتها620mAh ووزنها 1.9گ؛ الكثير من بطاريات أكسيد الفضة والألكالين لها نفس الحجم، وتعطي 150–200 mAh ويصل وزنها إلى 2.3–2.4 gگ[7]

التخزين وعمر التشغيل

لبطاريات الزنك-الهواء عمر تشغيل طويل عند حفظها بالغلاف بعيداً عن الهواء، حتى أنه يمكن تخزين بطاريات الساعات صغيرة الحجم لأكثر من 3 سنوات في درجة حرارة الغرفة وسوف تفقد القليل من قدرتها إذا لم يتم إزالة غلافها. البطاريات الصناعية المخزنة في مكان جاف لها عمر تخزين غير محدود.

عمر التشغيل لبطاريات الزنك-الهواء يعتمد بشكل كبير على تفاعله مع البيئة المحيطة بالبطاريات. يفقد الكهرل الكثير من المياه في الظروف التي ترتفع فيها درجة الحرارة وتنخفض الرطوبة. لأن كهرل هيدروكسيد الپوتاسيوم جاذب للرطوبة، تساعد الرطوبة العالية على تراكم كميات كبيرة من المياه داخل البطارية، فتعمر المهبط وتدمر خصائصه الفاعلة. يتفاعل هيدروكسيد الپوتاسيوم أيضاً مع ثاني أكسيد الكربون الموجود في الهواء؛ فتقلل المواد الكربونية الناتجة عن التفالع من قدرة الكهرل على التوصيل. الخلايا المصغرة قادرة على فقدان الشحن الذاني بدرجة كبيرة بمجرد فتحها للهواء؛ البطارية معدة للاستخدام في غضون أسابيع قليلة.[6]

خصائص التفريغ

لأن المهبط لا تتغير خصائصه أثناء فقدان الشحن، فالجهد الكهربائي النهائي مستقر تماماً حتى تصل البطارية إلى مرحلة التلف.

قدرة الطاقة تعتمد على متغيرات متعددة: منطقة المهبط، الهواء المتاح، المسامية، قيمة التحفيز من سطح المهبط. يجب الحفاظ على توازن دخول الأكسجين إلى البطارية إلى الماء المفقود من الكهرل؛ تغطى أغشية المهبط بمواد هيدروكربونية (تفلون) للحد من فقدان المياه. تعمل الرطوبة المنخفضة على زيادة عملية فقدان المياه؛ إذا لم تتوافر المياه الكافية فسوف تتوقف البطارية عن العمل. البطاريات الصغيرة لديها عمر تشغيل محدود؛ على سبيل المثال بطاريةIEC PR44 قدرتها 600 milliamp-hours (mAh) لكن أقصى قدرة لها حالياً 22 milliamps (mA) فقط.[6]

تقلل درجات الحرارة المرتفعة من القدرة الأولية للبطارية لكنها تأثيرها يكون محدود على البطاريات قصيرة العمر. يمكن أن تقوم البطارية بإنتاج 80% من قدرتها إذا ما تم تشغيلها لأكثر من 300 ساعة على درجة حرارة 0 س، لكنها تنتج 20% من قدرتها حال تشغيلها لمدة 50 ساعة على نفس درجة الحرارة. تقلل درجات الحرارة المنخفضة من جهد البطارية.

لا يمكن استخدام بطاريات الزنك-الهواء على حامل البطاريات المغلف حيث يجب أن تتعرض البطارية للقليل من الهواء؛ يستهلك الأكسجين الموجود في 1 لتر من الهواء في كل ساعة تشغيل.

الخلايا (الغير قابلة للشحن) الأولية

Large zinc–air batteries, with capacities up to 2,000 ampere–hours per cell, are used to power navigation instruments and marker lights, oceanographic experiments, and railway signals.

Primary zinc–air cells are made in button format to about 1 Ah. Prismatic shapes for portable devices are manufactured with capacities between 5 and 30 Ah. Hybrid cells have manganese dioxide added to the cathodes to allow high peak currents. Button cells are highly effective, but it is difficult to extend the same construction to larger sizes due to air diffusion performance, heat dissipation, and leakage problems. Prismatic and cylindrical cell designs address these problems. Stacking prismatic cells requires air channels in the battery and may require a fan to force air through the stack.[6]

خلايا (قابلة للشحن) ثانوية

Rechargeable zinc–air cells are a difficult design problem since zinc precipitation from the water-based electrolyte must be closely controlled. The problems are dendrite formation, non-uniform zinc dissolution and limited solubility in electrolytes. Electrically reversing the reaction at a bi-functional air cathode, to liberate oxygen from discharge reaction products, is difficult; membranes tested to date have low overall efficiency. Charging voltage is much higher than discharge voltage, producing cycle energy efficiency as low as 50%. Providing charge and discharge functions by separate uni-functional cathodes, increases cell size, weight, and complexity.[6] A satisfactory electrically recharged system potentially offers low material cost and high specific energy, but none has yet reached the market.[8]

الخلايا المعاد شحنها آلياً

Rechargeable systems may mechanically replace the anode and electrolyte, essentially operating as a refurbishable primary cell, or may use zinc powder or other methods to replenish the reactants. Mechanically-recharged systems were investigated for military electronics uses in the 1960s because of the high energy density and easy recharging. However, primary lithium batteries offered higher discharge rates and easier handling.

Mechanical recharging systems have been researched for decades for use in electric vehicles. Some approaches use a large zinc–air battery to maintain charge on a high discharge–rate battery used for peak loads during acceleration. Zinc granules serve as the reactant. Vehicles exchange used electrolyte and depleted zinc for fresh reactants at a service station to recharge.

The term zinc–air fuel cell usually refers to a zinc–air battery in which zinc metal is added and zinc oxide is removed continuously. Zinc electrolyte paste or pellets are pushed into a chamber, and waste zinc oxide is pumped into a waste tank or bladder inside the fuel tank. Fresh zinc paste or pellets are taken from the fuel tank. The zinc oxide waste is pumped out at a refueling station for recycling. Alternatively, this term may refer to an electrochemical system in which zinc is a co-reactant assisting the reformation of hydrocarbons at the anode of a fuel cell.

دفع المركبات

Metallic zinc could be used as an alternative fuel for vehicles, either in a zinc–air battery[9] or to generate hydrogen near the point of use. Zinc's characteristics have motivated considerable interest as an energy source for electric vehicles. Gulf General Atomic demonstrated a 20 kW vehicle battery. General Motors conducted tests in the 1970s. Neither project led to a commercial product.[10]

Solid zinc cannot be moved as easily as a liquid. An alternative is to form pellets that are small enough to be pumped. Fuel cells using it would be able to quickly replace zinc-oxide with fresh zinc metal.[11] The spent material can be recycled. The zinc–air "battery" cell is a primary cell (non-rechargeable); recycling is required to reclaim the zinc; much more energy is required to reclaim the zinc than is usable in a vehicle.

One advantage of utilizing zinc–air batteries for vehicle propulsion is that the availability of zinc metal is 100 times greater than that of lithium, per unit of battery energy. Current yearly global zinc production is sufficient to produce enough Zinc-Air batteries to power over one billion electric vehicles, whereas current lithium production is only sufficient to produce ten million lithium-ion powered vehicles.[12] Approximately 35% of the world's supply, or 1.8 gigatons of zinc reserves are in the United States,[13] whereas the U.S. holds only 0.38% of known lithium reserves.

تكوينات بديلة

Attempts to address zinc–air's limitations include[14]

- Pumping zinc slurry through the battery in one direction for charging and reversing for discharge. Capacity is limited only by the slurry reservoir size.

- Alternate electrode shapes (via gelling and binding agents)

- Managing humidity

- Carefully dispersing catalysts to improve oxygen reduction and production

- Modularizing components for repair without complete replacement

السلامة والبيئة

Vent holes allow any pressure build-up to be released. Zinc corrosion can produce hydrogen. Manufacturers caution against hydrogen build-up in enclosed areas. A short-circuited cell gives relatively low current. Deep discharge below 0.5 V/cell may result in electrolyte leakage; there is little useful capacity below 0.9 V/cell.

Older designs used mercury amalgam amounting to about 1% of the weight of a button cell, to prevent zinc corrosion. Newer types have no added mercury. Zinc is relatively low in toxicity. Mercury-free designs require no special handling when discarded or recycled.[6]

In United States waters, environmental regulations now require proper disposal of primary batteries removed from navigation aids. Formerly, discarded zinc–air primary batteries were dropped into the water around buoys, which allowed mercury in the cells to escape to the environment.[15]

انظر أيضاً

- بطارية الألومنيوم-الهواء

- Gas diffusion electrode

- Metal–air electrochemical cell

- تكنولوجيات الهيدروجين

- بطارية الزنك-البروميد

المصادر

- ^ power one: Hearing Aid Batteries. Powerone-batteries.com. Retrieved on 2012-09-30.

- ^ أ ب Duracell: Zinc–air Technical Bulletin. duracell.com

- ^ zincair_hybrid. greencarcongress (2004-11-03). Retrieved on 2012-09-30.

- ^ battery types. thermoanalytics. Retrieved on 2012-09-30.

- ^ US patent 1899615 Air-depolarized primary battery Heise – February, 1933

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح David Linden, Thomas B. Reddy (ed). Handbook Of Batteries 3rd Edition, McGraw-Hill, New York, 2002 ISBN 0-07-135978-8, chapter 13 and chapter 38

- ^ Energizer site, with battery datasheets. Data.energizer.com (2004-01-01). Retrieved on 2012-09-30.

- ^ ReVolt. Revolttechnology.com. Retrieved on 2012-09-30.

- ^ J. Noring et al, Mechanically refuelable zinc–air electric vehicle cells in Proceedings of the Symposium on Batteries and Fuel Cells for Stationary and Electric Vehicle Applications Volumes 93–98 of Proceedings (Electrochemical Society), The Electrochemical Society, 1993 ISBN 1-56677-055-6 pp. 235–236

- ^ C. A. C. Sequeira Environmental oriented electrochemistry Elsevier, 1994 ISBN 0-444-89456-X, pp. 216–217

- ^ Science & Technology Review. Llnl.gov (1995-10-16). Retrieved on 2012-09-30.

- ^ William Tahil (December 2006). The Trouble with Lithium Implications of Future PHEV Production for Lithium Demand. Meridian International Research

- ^ Zinc air fuel cell provides more benefits than lithium ion batteries. Machine Design (2010-10-07). Retrieved on 2012-09-30.

- ^ Bullis, Kevin (October 28, 2009). "High-Energy Batteries Coming to Market". Technology Review. Retrieved June 15, 2010.

- ^ U.S.C.G. Directive, retrieved 2010 Jan 18.

وصلات خارجية

- حافلات الزنك-الهواء

- الاستخدام العسكري لبطاريات الزنك-الهواء

- Zinc-Air Batteries for UAVs and MAVs

- Incorrect zinc–air reaction

- Zinc–air fuel cell

- Procedure to make a simple zinc–air fuel cell as a science fair project.

- ReVolt Technology developing rechargeable zinc–air batteries

- Duracell technical bulletin (suppliers of zinc–air hearing aid batteries)

- Overview of batteries

- Revolt Introduction

- Metal Air Batteries

قراءات إضافية

- Heise, G. W. and Schumacher, E. A., An Air-Depolarized Primary Cell with Caustic Alkali Electrolyte, Transactions of the Electrochemical Society, Vol. 62, Page 363, 1932.