كولتپه

Kültepe | |

مشهد من المستعمرة التجارية كولتپه ("كاروم" من "كانـِش") مع جبل إرجييس (20 كم) بادياً في الخلفية. | |

خطأ: إحداثيات غير صالحة. | |

| المكان | محافظة قيصري، تركيا |

|---|---|

| المنطقة | الأناضول |

| الإحداثيات | 38°51′N 35°38′E / 38.850°N 35.633°E |

| النوع | مستوطنة |

| التاريخ | |

| الثقافات | Hittite Assyrian |

| ملاحظات حول الموقع | |

| الحالة | In ruins |

كانـِش Kanish مستعمرة تجارية آشورية في كپادوكيا Cappadocia بآسيا الصغرى، تقع على بعد عشرين كيلو متراً إلى الشمال الشرقي من مدينة قيسارية Kayseri في تركيا، وتسمى حالياً كولتِبه Kultepe.

تتألف من هضبة، قطرها خمسمئة متر وارتفاعها عشرون متراً، ومن المدينة المنخفضة كارو Káru - وتعني الوكالة التجارية - التي تحيط بالهضبة من جهاتها الأربع، والتي سكنها التجار الآشوريون، وقطرها كيلومتر واحد مع الهضبة والقلعة التي تقع في وسطها، وتحيط بالكل أسوار قوية.

بدأ التنقيب فيها إرنست شانتر E.Chantre عام 1893 و1894، ثم هوگو ڤينكلر H.Winckler وهـ. گروته H.Grothe عام 1906، وتابع العمل بيدريتش هروزني B.Hrozny عام 1925، وتمكن من اكتشاف مصدر الألواح الكتابية التي عثر عليها قبلاً، وهو كارو، أو المركز التجاري للمستوطنين الآشوريين.

بدأت في عام 1948 تنقيبات منتظمة في الهضبة وفي كارو، قام بها فريق من الجمعية التاريخية التركية، والمديرية العامة للشؤون التاريخية والمتاحف بإدارة تحسين اوزگوچ T.Ozguç.

أظهرت الحفريات أن أقدم استيطان في المنطقة يعود إلى العصر الحجري النحاسي المتأخر Chalcolithic، ثم تلاه العصر البرونزي القديم، فالعصر الحثي، ثم العصر الفريجي Phrygian، فالهلنستي والروماني والبيزنطي.

كُشف في كانيش عن طبقات أثرية عدة، تعود إلى الألفين الثالث والثاني قبل الميلاد، أقدمها تحوي معبداً يعد من أقدم معابد الأناضول على الإطلاق، ثم توسعت المدينة زمن الوكالة التجارية وبنيت فيها القصور والمعابد والأبنية الكبيرة.

أغنى الطبقات كانت الأولى والثانية، وعثر فيهما على مدينة تحوي بيوتاً مخططاتها مربعة، بنيت من الحجر والطين، تألف بعضها من غرفة أو غرفتين من دون نوافذ، وهناك بيوت كبيرة تألفت من طابقين وبجانبها تنانير للخبز ولشيّ الفخار، وفي ساحات البيوت انتشرت الدكاكين والورشات والمستودعات، وحولها الأزقة والساحات الواسعة.

كما اكتشف قصران، أحدهما قصر الملك الأناضولي أنيتـّا Anitta الذي عاصر الوجود الآشوري، وعثر فيه على عدد من الألواح المكتوبة بالمسمارية. والقصر الثاني يعود إلى عهد الملك فارشاما Varshama، وعلى الرغم من تهدم معظمه، إلا أنه كُشف عن خمسين غرفة من الطابق الأرضي وجزء من الأرشيف، الذي احتوى بعض المراسلات بين ملك كانيش وبعض ملوك المناطق المجاورة.

التجارة مع الآشوريين

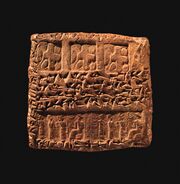

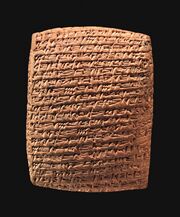

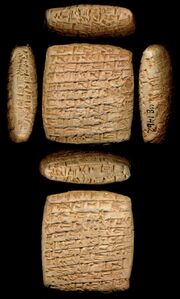

وقد تضمن أرشيف الموقع آلاف الألواح الكتابية التي دونت باللغة الآشورية القديمة، كما وجدت كتابات مصرية وسومرية وبابلية، حوت معلومات قيمة عن التجارة بين الآشوريين والأناضول، ومعلومات اجتماعية عن الزواج والطلاق والإرث، وقرارات المحاكم، والمراسلات مع الأمراء المحليين، كما عثر بين هذه الألواح على عدد من النصوص الأدبية ونصوص تدريبية؛ مما دل على وجود مدارس لتعليم الكتابة والقراءة.

عثر على كثير من اللقى الأثرية الفخارية والمعدنية، ومنها الجرار الملونة والمزخرفة، والأواني ذات الأشكال الحيوانية (الريطون) Rhytons، وتماثيل الآلهة المذكرة والمؤنثة المصنوعة من المعادن المختلفة والعاج، والأختام الأسطوانية ذات المشاهد الأسطورية، إضافة إلى أدوات الزينة والأسلحة وأدوات الزراعة وغيرها، وكل هذه اللقى تظهر امتزاج الثقافة الرافدية بالثقافة الأناضولية، وتشهد على علاقات تجارية وثقافية عميقة مع سورية ومصر زمن الدولة الوسطى، ولاسيما مع العثور على أوانٍ في موقع وكالة «كرما» Kerma التجارية في النوبة، وهي نسخ لأشكال أناضولية.

ودام الوجود التجاري الآشوري في كانيش، من 1950ق.م حتى 1650ق.م تقريباً، كانت كانيش في أثنائها عقدة مواصلات المركز الرئيس لشبكة التجارة الآشورية في آسيا الصغرى. وكانت كانيش تفصل في المنازعات بين التجار، وأحياناً بين التجار الآشوريين وغيرهم من المحليين. كما قام التجار الآشوريون باستثمار المناجم، واحتكروا بيع النحاس المحلي، وقاموا بتصنيع البرونز مع القصدير ذي الأصل القفقاسي، وأتوا بالأقمشة من بلاد مابين النهرين.

ومن الواضح أن العلاقة بين الجالية الأجنبية الثرية وبين السكان المحليين وحكامهم لم تكن على ما يرام، وإنما اعتراها في كثير من الأحيان الجفاء والشعور بالاستياء، وهذا ما أدى بالنتيجة إلى تدمير وإحراق كاروم كانش والمستوطنات التابعة لها على أيدي الدولة الحثية التي ستوحد قريباً كل مدن آسيا الصغرى، وتأسيس إمبراطورية مترامية الأطراف.

ومع زوال التجار الأجانب توقفت عجلة الاقتصاد في كبادوكيا، وتراجع جزء من الإسهام الحضاري والثقافي الرافدي في منطقة الأناضول التي دخلت في عصر الظلام.

الآثار

By 1880, cuneiform tablets said to be from Kara Eyuk ('black village') or Gyul Tepé ('burnt mound') near Kaisariyeh, had begun to appear on the market, some being thus bought by the British Museum.[1] In response the site was worked by Ernest Chantre for two seasons, beginning in 1893.[2] Hugo Grothe dug a small soundage in 1906.[3] In 1925, Bedřich Hrozný excavated Kültepe and found over 1000 cuneiform tablets, some of which ended up in Prague and in Istanbul.[4][5] In 1929 the site was visited and photographed by James Henry Breasted of the Oriental Institute of Chicago. There had been much digging for fertilizer, which had destroyed a quarter of the mound.[6]

Modern archaeological work began in 1948, when Kültepe was excavated by a team from the Turkish Historical Society and the General Directorate of Antiquities and Museums. The team was led by Tahsin Özgüç until his death, in 2005.[7]

- Level IV–III. Little excavation has been done for these levels, which represent the kārum's first habitation.[8] No writing is attested, and archaeologists assume that both levels' inhabitants were illiterate.

- Level II, 1974–1836 BC (Mesopotamian middle chronology according to Veenhof). Craftsmen of this time and place specialised in animal-shaped earthen drinking vessels, which were often used for religious rituals. Assyrian merchants then established the kārum of the city: "Kaneš". Bullae of Naram-Sin of Eshnunna have been found toward the end of this level, which was burned to the ground.[9]

- Level Ib, 1798–1740 BC. After an abandoned period, the city was rebuilt over the ruins of the old and again became a prosperous trade center. The trade was under the control of Ishme-Dagan I, who was put in control of Assur when his father, Shamshi-Adad I, conquered Ekallatum and Assur. However, the colony was again destroyed by fire.

- Level Ia. The city was reinhabited, but the Assyrian colony was no longer inhabited. The culture was early Hittite. Its name in Hittite acquired an extra sound as "Kaneša", which was more commonly contracted to "Neša".

Some attribute Level II's burning to the conquest of the city of Assur by the kings of Eshnunna, but Bryce blames it on the raid of Uhna. Some attribute Level Ib's burning to the fall of Assur, other nearby kings and eventually to Hammurabi of Babylon.

To date, over 20,000 cuneiform tablets have been recovered from the site, mainly from the kārum, with only 40 found in the Upper city.[10][11]

Subsequent excavations attested the following stratigraphy of Kültepe:[12]

| Upper Town Level | Lower Town Level | Period | Name, Importance |

|---|---|---|---|

| 18 | — | Early Bronze Age I | |

| 17–14 | — | Early Bronze Age II | |

| 13–11 | — | Early Bronze Age III 2500–2100 BC[13] |

Kaneš; first written as Ga-ni-šu ki[14] Level 12 temple (megaron) and Level 11b building with pilasters[15] |

| 10 | IV | Middle Bronze Age 2100–2000 BC |

Beginning of urban development |

| 9 | III | Middle Bronze Age 2000–1970 BC |

|

| 8 | II | kārum-period 1974/1927–1836 BC |

Kaniš; Anatolian center of Assyrian trade |

| 7 | Ib | kārum-period 1832/1800–1719 BC |

Kaniš; Assyrian trading center |

| 6 | Ia | Old Hittite period | Neša; the place no longer has a central function |

| Settlement gap | |||

| 5–4 | — | Iron Age 9/8 century BC |

important central location in the Neo-Hittite state Tabal |

| Settlement gap | |||

| 3 | Graves | Hellenistic Age | Anisa; Polis; Coin finds from 323 BC |

| 2–1 | Graves | Roman Age | insignificant settlement; Coin finds up to 180 AD |

Recently, in "a small cell-plan structure cutting the walls of the monumental building [o]f Kültepe [Level 13], dated to the second half of the 3rd Millennium BC, statuettes made of alabaster with various attributes and ritual vessels in unprecedented forms were found in situ," and inside a "monumental building [d]iscovered in 2018 [which] contains a room called the 'idol room,' [a] collection of the largest number of idols and statuettes ever discovered in the ancient Near East [was found]."[16]

كاروم كانش

The quarter of the city that most interests historians is the kārum, a portion of the city that was set aside by local officials for the early Assyrian merchants to use without paying taxes as long as the goods remained inside the kārum. The term kārum means "port" in Akkadian, the lingua franca of the time, but its meaning was later extended to refer to any trading colony whether or not it bordered water.

Several other cities in Anatolia also had a kārum, but the largest was Kaneš, whose important kārum was inhabited by soldiers and merchants from Assyria for hundreds of years. They traded local tin and wool for luxury items, foodstuffs, spices and woven fabrics from the Assyrian homeland and Elam.

The remains of the kārum form a large circular mound 500 m in diameter and about 20 m above the plain (a tell). The kārum settlement is the result of several superimposed stratigraphic periods. New buildings were constructed on top of the remains of the earlier periods so there is a deep stratigraphy from prehistoric times to the early Hittite period.

The kārum was destroyed by fire at the end of levels II and Ib. The inhabitants left most of their possessions behind, as found by modern archaeologists.

The findings have included numerous baked-clay tablets, some of which were enclosed in clay envelopes stamped with cylinder seals. The documents record common activities, such as trade between the Assyrian colony and the city-state of Assur and between Assyrian merchants and local people. The trade was run by families rather than the state. The Kültepe texts are the oldest documents from Anatolia. Although they are written in Old Assyrian, the Hittite loanwords and names in the texts are the oldest record of any Indo-European language[17] (see also Ishara). Most of the archaeological evidence is typical of Anatolia rather than of Assyria, but the use of both cuneiform and the dialect is the best indication of Assyrian presence.

تأريخ Waršama Sarayi

At Level II, the destruction was so total that no wood survived for dendrochronological studies. In 2003, researchers from Cornell University dated wood in level Ib from the rest of the city, built centuries earlier. The dendrochronologists date the bulk of the wood from buildings of the Waršama Sarayi to 1832 BC, with further refurbishments up to 1779 BC.[18] In 2016 new research using carbondating and dendrology on timber used in this site and the palace in Acemhöyük show the likely earliest use of the palace as not before 1851–1842 BC (68.2% hpd) or 1855–1839 BC (95.4% hpd).[19] In combination with the many Assyrian objects found here, this dating shows that only middle or low-middle chronology are the only remaining possible chronologies that fit these new data.

معرض صور

كولتپه: الخنجر البرونزي للملك أنيتـّا، ملك كوشـّارا.

انظر أيضاً

الهامش

- ^ [1] A. H. Sayce, The Museum Collection Of Cappadocian Tablets, The Museum Journal, vol. IX, no. 2, pp. 148-150, Penn Museum, June 1918

- ^ Ernest Chantre, Recherches archéologiques dans l'Asie occidentale : mission en Cappadoce, 1893-1894, 1898

- ^ Hugo Grothe, Meine Vorderasienexpedilion 1906 und 1907, I (Leipzig, 1911)

- ^ Julius Lewy, Die altassyrischen Texte vom Kültepe bei Kaisarije, Konstantinopel, 1926

- ^ Veysel Donbaz, Keilschrifttexte in den Antiken-Museen zu Stambul 2, Freiburger Altorientalische Studien, 1989

- ^ [2] James Henry Breasted, EXPLORATIONS IN HITTITE ASIA MINOR—1929, ORIENTAL INSTITUTE COMMUNICATIONS, no. 8, Oriental Institute of Chicago, 1929

- ^ Tahsin Özgüç, The Palaces and Temples of Kultepe-Kanis/Nesa, Turk Tarih Kurumu Basimevi, 1999, ISBN 975-16-1066-4

- ^ (Mellaart, 1957)

- ^ (Ozkan, 1993)

- ^ E. Bilgic and S Bayram, Ankara Kultepe Tabletleri II, Turk Tarih Kurumu Basimevi, 1995, ISBN 975-16-0246-7

- ^ K. R. Veenhof, Ankara Kultepe Tabletleri V, Turk Tarih Kurumu, 2010, ISBN 978-975-16-2235-8

- ^ Gojko Barjamovic: A Historical Geography of Anatolia in the Old Assyrian Colony Period; Copenhagen 2011. ISBN 978-87-635-3645-5, S. 231.

- ^ Kulakoğlu, Fikri, & Güzel Öztürk, (February 2015). New evidence for international trade in Bronze Age central Anatolia: recently discovered bullae at Kültepe-Kanesh, in: Antiquity, Issue 343, Volume 89: "Two monumental structures, a building and a temple, were unearthed in Levels 12 and 11b of EBA III (c. 2400–2100 BC)."

- ^ Powell et al. 2023, Introduction: "The late part of the Early Bronze Age at Kültepe is represented by three phases, the last of which consists of two secondary sub-phases (EBA III = Kültepe Levels 13-11a-b) [...] The name Kaneš for the site is first attested during this period (wr. Ga-ni-šu ki, cf. Archi, 2017)".

- ^ Kulakoğlu, Fikri, & Güzel Öztürk, (February 2015). New evidence for international trade in Bronze Age central Anatolia: recently discovered bullae at Kültepe-Kanesh, in: Antiquity, Issue 343, Volume 89: "[T]he Kültepe Level 12 temple, which is called a megaron with its rectangular plan and which contains a long hall andÖztür a porch in front, approaches that of the largest and best-known megaron of Troy II in western Anatolia [...] The so-called 'building with pilasters' (Özgüç 1986: 34) is dated to Level 11b."

- ^ Öztürk, Güzel, and Fikri Kulakoglu, (2023). "New Discoveries on Alabaster Idols and Statuettes of the 3rd Millennium BC at Kültepe: A Comparative Analysis to Understand the Typology, Context And Meanings of Ritual Objects", in: 2023 ASOR Abstract Booklet, pp. 76-77.

- ^ Watkins, Calvert. "Hittite". In: The Ancient Languages of Asia Minor. Edited by Roger D. Woodard. Cambridge University Press. 2008. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-511-39353-2

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-09-27. Retrieved 2006-07-03.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Manning, Sturt W.; Griggs, Carol B.; Lorentzen, Brita; Barjamovic, Gojko; Ramsey, Christopher Bronk; Kromer, Bernd; Wild, Eva Maria (2016). "Integrated Tree-Ring-Radiocarbon High-Resolution Timeframe to Resolve Earlier Second Millennium BCE Mesopotamian Chronology". PLOS ONE. 11 (7): e0157144. Bibcode:2016PLoSO..1157144M. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0157144. PMC 4943651. PMID 27409585.

المصادر

المصادر

- إبراهيم توكلنا. "كانيش (كولتِبِه)". الموسوعة العربية.

- Tahsin Özgüç, Kültepe, Yapi Kredi, 2005, ISBN 9750809602

- KR Veenhof, Kanesh: an Old Assyrian colony in Anatolia, in Civilizations of the Ancient Near East ed. by J. Sasson, Scribners, 1995