سمأل

موقع سمأل الأثري | |

| |

خطأ: إحداثيات غير صالحة. | |

| الاسم البديل | سمأل |

|---|---|

| المكان | Gaziantep Province, Turkey |

| الإحداثيات | 37°06′13″N 36°40′43″E / 37.10361°N 36.67861°E |

| النوع | Settlement |

| ملاحظات حول الموقع | |

| تواريخ الحفريات | 1888, 1890, 1891, 1894, 1902, 2006-2017 |

| الأثريون | Felix von Luschan, Robert Koldewey, David Schloen, Virginia Herrmann |

| الحالة | In ruins |

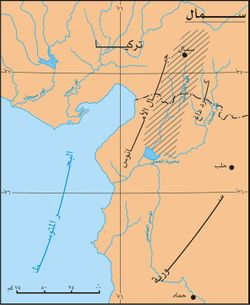

سمأل مملكة آرامية قديمة، تقع في أقصى الشمال من بلاد الشام، في موقع زنجرلى الحالي قرب منابع نهر الأسود، عند سفوح جبال الأمانوس. يحيط بها جبل الأمانوس وكردداغ من الغرب والشرق على التوالي، وسهل العمق الذي يحدها من جهة الجنوب. وكانت سمأل محاطة بمجموعة من الإمارات الحثية الجديدة (جرجوم وطابال ودانونا) والإمارات الآرامية (بيت اجوشي وحماة ولعش).

وسمأل هي التسمية الآشورية للمملكة، في حين أن ملوكها دعوا أنفسهم في كتاباتهم الآرامية ملوك يأدي (أنا فنمو ملك يأدي) أو ملوك شمأل (أنا بر-رقيب ملك سمأل).

تاريخ

ويمكن إعادة بناء تاريخ سمأل من المكتشفات التي نتجت من أعمال التنقيب الأثري في الموقع، ومن نصوص كتابية تعود لدول كانت على علاقة مع سمأل (المملكة الآشورية ومملكة حماه الآرامية وغيرها).

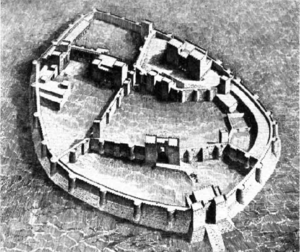

بدأت التنقيبات الأثرية في الموقع من قبل بعثة أثرية من الجمعية الشرقية الألمانية بقيادة فليكس فون لوشان وروبرت كولدڤي (1888-1902).[1][2][3][4][5] وقد كشفت تلك البعثة عن سور مزدوج كان يحيط بالمدينة، مزوداً بالأبراج والبوابات المزينة بلوحات حجرية ذات نقوش متنوعة، وعثر في مركز المدينة على مجموعة من المباني والقصور المحاطة بجدار بيضوي الشكل، ومن الأشياء المهمة التي عثر عليها: مجموعة من الكتابات الفينيقية والآرامية التي أمر بوضعها ملوك سمأل تكريماً لآلهتهم وتخليداً لآبائهم وأعمالهم.

ومن اللقى الفخارية التي عثر عليها في الموقع تبين أن منطقة سمأل كانت مأهولة بالسكان، منذ مطلع الألفية الثانية ق.م.، ومع التوسع الحثي نحو شمالي سورية في عهد الدولة الحثية القديمة (القرن السابع عشر ق0م)، وقعت منطقة سمأل تحت النفوذ الحثي، وحينما تراجع هؤلاء الحثيون عن شمالي سورية، نتيجة مشكلاتهم الداخلية، وحل محلهم الحوريون الميتانيون، وقعت تحت نفوذ الحوريين.

ثم خضعت المنطقة للحثيين في عهد الدولة الحثية الجديدة في القرنين الرابع عشر والثالث عشر ق.م.، وقد ترافق انهيار الامبراطورية الحثية، مطلع القرن الثاني عشر ق.م.، نتيجة هجوم شعوب البحر، مع تغلغل العناصر الآرامية إلى منطقة سمأل، وتمكن الآراميون من فرض نفوذهم وهيمنتهم عليها وأنشؤوا أسرة حاكمة فيها.

سمحت الكتابات المكتشفة في سمأل للعلماء بوضع سلسلة ملوك هذه الدولة، ومن هذه الكتابات: كتابة تنسب إلى الملك «كيلاموه» وتؤرخ بحدود العام 825 ق.م، ذُكرت فيها أسماء الملوك الذين حكموا قبله (أنا «كيلاموة» بن «خيا»، مَلك «جبر» على يأدي ولم يفعل شيئاً، وكان بمه ولم يفعل، وكان أبي خيا ولم يفعل، وكان أخي شال ولم يفعل...).

فهذا النقش يذكر أسماء أربعة ملوك حكموا قبل «كيلاموة»؛ والده «خيا» (أو حيان) وشقيقه «شال» و«بمه» و«جبر» (جبار). والصلة مجهولة بين «جبر» و«بمه» من ناحية وبينهما وبين «خيا» والد «كيلاموة» من ناحية ثانية. ولا يعرف شيء عن أعمالهم وتاريخ حكم كل واحد منهم، إلا أنه يمكن الافتراض أن هؤلاء الأربعة قد حكموا في النصف الثاني من القرن العاشر ق.م والنصف الأول من القرن التاسع ق.م. فمن المعلوم مثلاً أن «خيا» قد التزم دفع الجزية للملك الآشوري «شلمناصر الثالث» (856-824 ق.م) في أثناء إحدى حملاته نحو شمالي سورية. أما «كيلاموة» فقد اضطر إلى مواجهة مشاكل داخلية وخارجية في أثناء حكمه، فأما مشكلاته الداخلية فتمثلت في انقسام مجتمع سمأل فئتين تذكرهما نصوصه، وهما البعرريم (وربما كان هؤلاء من البدو غير المستقرين) والموشكبيم وهم من السكان المستقرين. ويبدو أن البعرريم كانوا أقل حظاً من الموشكبيم لذلك سارع كيلاموة إلى نصرة هؤلاء (... ومن منهم لم ير شاة أو بقرة في حياته جعله يملك قطيعاً وفضة وذهباً...).

وأما مشكلاته الخارجية فتمثلت في مملكة دانونا الواقعة إلى الشمال من سمأل، فاستعان كيلاموه عليهم بالآشوريين، مما أوقعه ومملكته تحت نفوذهم. ومن خلال نقش الملك «زكور»، ملك حماه ولعش، تبين أن ملك سمأل كان من بين الأمراء والملوك السوريين الذين تحالفوا ضد الملك الحموي.

وكان «قرل» هو خليفة «كيلاموه» ولكن ليس هنالك أي معلومات عن مدة حكمه.

وخلفه ابنه «فنموه» الذي ترك بعض الكتابات الموقوفة للإله هدد. ومن خلال كتابة ترجع إلى الملك «برراكيب» وتسجل بعض الأحداث التي جرت في عهد «فنموه»، تبين أن الأوضاع في المملكة اضطربت إلى حد كبير، وأدت في النهاية إلى اغتيال الملك «فنموه» وابنه «برصور» وسبعين شخصاً من أبناء الأسرة الحاكمة. وكان «فنموه» الثاني والد «برراكيب» من الناجين القلائل من هذه المذبحة، وقد تمكن من خلال اتصاله مع الملك الآشوري «تغلات بلاصر الثالث» (745-727ق.م) من الجلوس على عرش سمأل.

وقد حاول «فنموه» الثاني، وكما يذكر ابنه «برراكيب» في كتاباته، إصلاح الأوضاع في سمأل عن طريق فتح السجون وتحرير النساء ودفن القتلى، وكانت نهاية «فنموه الثاني» القتل في أثناء مشاركته في حملة الملك الآشوري «تغلات بلاصر الثالث» ضد آرام دمشق في العام 732ق.م.

وكان «برراكيب» آخر ملوك سمأل، وكان مخلصاً للآشوريين ملتزماً بسياستهم في سوريا إلى حد كبير. ومن خلال مجموعة النصوص التي تركها يتبين أن سمأل عادت لتشهد عهداً من الازدهار، إذ عمد إلى تجديد مبانيها وبناء قصور جديدة فيها.

تحولت سمأل إلى مقاطعة آشورية مع بداية حكم شروكين الثاني (722-705ق.م)، وأصبحت مركزاً للنفوذ الآشوري في بلاد الأناضول الجنوبية الغربية. وتتجلى أهمية سمأل في كونها نقطة تلاقت فيها المؤثرات الحضارية السورية (الفينيقية ـ الآرامية) والأناضولية (الحثية - اللوفية) والرافدية (الآشورية)، ويتجلى ذلك من خلال النقوش الكتابية المتعددة اللغات التي عثر عليها في المدينة، والتأثيرات الفنية المتعددة والسياسة الموالية للآشوريين التي سار عليها أغلب ملوكها.

الآثار

The site covers an area of about 40 hectares. It was visited by archaeologist Osman Hamdi Bey in 1882. In 1883 three German travelers collected and took photographs there. At that time orthostats were still visible at the surface.[6] It was excavated in 1888, 1890, 1891, 1894 and 1902 during expeditions led by Felix von Luschan and Robert Koldewey. Each of the expeditions was supported by the German Orient Committee, except for the fourth (1894), which was financed with monies from the Rudolf-Virchow-Stiftung and private donors. They found a walled heavily fortified teardrop-shaped citadel accessed by the outer citadel gate, which was surrounded by the as yet unexcavated town and a further enormous 2.5 kilometer long double fortification wall with three gates (most notably the southern city gate) and 100 bastions. Finds from the excavations are held in the Vorderasiatisches Museum Berlin and the Istanbul Archaeology Museum. The Louvre holds a carved orthostat and two sphinx protomes and some minor sculptures are held at museums in Adana and Gaziantep.[7][8] During the 1902 excavation at Zincirli Höyük the Kilamuwa Stela (Zincirli 65), a 9th-century BC stele of King Kilamuwa (c. 840–810 BC) in Phoenician language was found at the entrance to Building J. It is written in an Old Aramaic form of the Phoenician alphabet.[9]

At the foundation of Gate E of the inner citadel five basalt lion statues were found buried in a pit that ranged as deep as 4.2 meters. The date of the pit is unclear, though the excavators suggested the Middle Bronze age. The statues are in two different styles which the excavators placed as being from the late 10th century BC (Zincirli I) and c. 700 BC (Zincirli IV). These became known as the Sam'al lions.[10]

There were five excavation reports:

- Volume 1: Felix von Luschan et al, "Ausgrabungen in Sendschirli: Einleitung und Inschriften", Spemann, 1893

- Volume 2: Felix von Luschan and Carl Humann and Robert Koldewey, "Ausgrabungen in Sendschirli: Ausgrabungsbericht und Architektur", Spemann, 1898

- Volume 3: Felix von Luschan, "Ausgrabungen in Sendschirli: Thorsculpturen", Georg Reimer, 1902

- Volume 4: Felix von Luschan and Gustav Jacoby, "Ausgrabungen in Sendschirli", Georg Reimer, 1911

- Volume 5: Felix von Luschan and Walter Andrae, "Ausgrabungen in Sendschirli: Die Kleinfunde von Sendschirli", Walter de Gruyter, 1943

The field diaries of the excavation were lost during World War II.

In August 2006, the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago together with the Institute for Ancient Near Eastern Studies of the University of Tübingen began a new long-term excavation project at the site of Zincirli under the directorship of David Schloen and Virginia Herrmann.[11][12] Eleven seasons of excavation were conducted ending in 2017. [13] [14][15] Finds included the Kuttamuwa stele, in the Samalian variant of Aramaic and dated c. 740 BC.[16][17] A destroyed Middle Bronze Age II building was found at Area 2 on the eastern citadel. it is nearby and on the same stratigraphic level as the bit-hilani palace located by early excavators. That palace was present only in its stone foundations as the area was clear for construction of the Neo-Assyrian governors residence (Palace G) of the 7th century BC.[18] With the redating of the bit-hilani structure there is not a complete lack of monumental construction in Iron Age II until the time of Kilamuwa.[19]

نقوش عُثر عليها في المنطقة

Multiple important historical inscriptions have been found in this area. They include at least seven inscriptions, as listed at the link above, including the Kuttamuwa stele found in 2008.

The German excavations on the citadel recovered large numbers of relief-carved orthostats, along with inscriptions in Aramaic, Phoenician, and Akkadian. These are on exhibit in the Pergamon Museum, Berlin, and Istanbul. Also found was the notable Victory stele of Neo-Assyrian ruler Esarhaddon celebrating his victory over Egyptian pharaoh Taharqa in 671 BC.[20]

Three royal inscriptions from Ya'udi or Sam'al are particularly informative for the history of the area. The earliest is from the reign of King Panammu I, the others later at 730 BC. Their language is known as Samalian or Ya'udic. Some scholars including P.-E. Dion[21] and S. Moscati[22] have advanced Samalian as a distinct variety of Old Aramaic.[23][24][25] Attempts to establish a rigorous definition of "Aramaic" have led to a conclusion of Samalian as distinct from Aramaic, despite some shared features.[26][27][28]

نقش پانجرلي هويوك

The site of Pancarli Hoyuk is located about 1 km southeast of Zincirli. A new hieroglyphic Luwian inscription has been discovered here in 2006, and published in 2016.[29]

The inscription is fragmentary, but nevertheless it appears to be of a royal character. Previously, all known inscriptions from this area were exclusively written in Northwest Semitic languages. According to the authors, the most probable conclusion is that PANCARLI inscription represents a ruler or a local king of the tenth or early ninth century BC.[29]

This inscription provides new information about the Early Iron Age of the Islahiye valley, and the history of the Aramaean dynasty of Gabbar.

If the inscription is considered to date to the 10th century BC, it may be the first solid evidence for a Luwian-speaking kingdom in the Islahiye valley, as possibly an offshoot of the Hittite rump-state at Karkemish.[29]

معرض

Kilamuwa Stela: an inscription of Prince Kilamuwa of Samal, Pergamon Museum

Hadad Statue with inscription (KAI 214), Pergamon Museum

Panamuwa II inscription (KAI 215)

Bar-Rakib stele I (KAI 216), Istanbul Museum

Bar-Rakib stele III (KAI 218), Pergamon Museum

Stele of Ördek-Burnu in the Istanbul Museum of the Ancient Orient

انظر أيضاً

المصادر

- الموسوعة العربية

- Simon B. Parker (1996). "Appeals for military intervention: stories from Zinjirli and the Bible". The Biblical Archaeologist 59(4): 213-224.

- Ussishkin, David (1970). "The Syro-Hittite ritual burial of monuments". Journal of Near Eastern Studies 29(2): 124-128.

- Ralf-B Wartke, Sam’al: Ein aramäischer Stadtstaat des 10. bis 8. Jhs. v. Chr. und die Geschichte seiner Erforschung, Philipp von Zabern, 2005

- J. P. Francev, ed. (1967). Világtörténet tíz kötetben, I. kötet. Kossuth K. (مجرية)

الهامش

- ^ Felix von Luschan et al, Ausgrabungen in Sendschirli. vol. 1: Einleitung und Inschriften, Spemann, 1893

- ^ Felix von Luschan and Carl Humann and Robert Koldewey, Ausgrabungen in Sendschirli. vol. 2: Ausgrabungsbericht und Architektur, Spemann, 1898

- ^ Felix von Luschan, Ausgrabungen in Sendschirli. vol. 3: Thorsculpturen, Georg Reimer, 1902

- ^ Felix von Luschan and Gustav Jacoby, Ausgrabungen in Sendschirli. vol. 4: Georg Reimer, 1911

- ^ Felix von Luschan and Walter Andrae, Ausgrabungen in Sendschirli. vol. 5: Die Kleinfunde von Sendschirli, Walter de Gruyter, 1943

- ^ Ralf-B Wartke, "Sam'al: Ein aramäischer Stadtstaat des 10. bis 8. Jhs. v. Chr. und die Geschichte seiner Erforschung", Philipp von Zabern, 2005

- ^ Felix von Luschan, "Ueber einige Ergebnisse der fünften Expedition nach Sendschirli", Zeitschrift für Ethnologie 34, pp. 379–80, 1902

- ^ Tropper, Josef, "Die Inschriften von Zincirli: Neue Edition und vergleichende Grammatikdes phönizischen, sam’alischen und aramäischen Textkorpus (ALASP 6)", Münster:Ugarit-Verlag, 1993

- ^ Schmitz, Philip C., "The Phoenician Words mškb and ʿrr in the Royal Inscription of Kulamuwa (KAI 24.14–15) and the Body Language of Peripheral Politics", Linguistic Studies in Phoenician, edited by Robert D. Holmstedt and Aaron Schade, University Park, USA: Penn State University Press, pp. 68-83, 2013

- ^ Gilibert, Alessandra, "Zincirli", Syro-Hittite Monumental Art and the Archaeology of Performance: The Stone Reliefs at Carchemish and Zincirli in the Earlier First Millennium BCE, Berlin, New York: De Gruyter, pp. 55-96, 2011

- ^ J. David Schloen and Amir S. Fink, "New Excavations at Zincirli Höyük in Turkey (Ancient Sam'al) and the Discovery of an Inscribed Mortuary Stele", Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research, vol. 356, pp. 1–13, November 2009

- ^ Schloen, J David; Fink, Amir S., "Searching for Ancient Sam'al: New Excavations at Zincirli in Turkey", Near Eastern Archaeology, vol. 72, iss. 4, pp. 203–219, 2009

- ^ [1] Virginia R. Herrmann and David Schloen, "Excavations at Zincirli Höyük in Turkey: 2015 Season", Oriental Institute of Chicago, 2016

- ^ Kathryn R. Morgan and Sebastiano Soldi, "Middle Bronze Age Zincirli: An Interim Report on Architecture, Small Finds, and Ceramics from a Monumental Complex of the 17th Century b.c.e.", Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research, vol. 385, pp. 33–51, May 2021

- ^ Schloen, J. David, and Virginia R. Herrmann, "Zincirli Höyük Excavations 2015", Kazı Sonuçları Toplantısı 38/3, pp. 173–186, 2016

- ^ [2]Virginia Rimmer Herrmann and J. David Schloen, "In Remembrance of Me: Feasting with the Dead in the Ancient Middle East", Oriental Institute Museum Publications 37, Chicago: The Oriental Institute, 2014 ISBN 978-1-61491-017-6

- ^ Pardee, Dennis, "A new Aramaic inscription from Zincirli", Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 356.1, pp. 51-71, 2009

- ^ Herrmann, V. R., and Schloen J. D., "Zincirli Höyük, Ancient Sam’al: A Preliminary Report on the 2015 Excavation Season", In: B. Horejs, C. Schwall, V. Müller, et al. (eds.), Proceedings of the 10th International Congress on the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East, 25-29 April 2016, Vienna (Wiesbaden), pp. 521–534, 2018

- ^ Herrmann, Virginia R., and David Schloen, "Zincirli Höyük, Ancient Sam’al: A Preliminary Report on the 2017 Excavation Season", Proceedings of the 11th International Congress on the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East: Vol. 2: Field Reports. Islamic Archaeology, edited by Adelheid Otto et al., 1st ed., Harrassowitz Verlag, pp. 129–40, 2020

- ^ Leichty, E., "The Royal Inscriptions of Esarhaddon, King of Assyria (680–669 BC)", Royal Inscriptions of the Neo-Assyrian Period 4, Winona Lake, 2011

- ^ P.-E. Dion, La langue de Ya'udi (Waterloo, Ontario 1974), in: RSO 53 (1979)

- ^ Moscati 1964, S.—: An Introduction to the Comparative Grammar of the Semitic Languages, Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden.

- ^ Klaus Beyer The Aramaic Language, Its Distribution and Subdivisions 1986– Page 12 3525535732 "In addition the three "Ya'udic" royal inscriptions from Zinjirli in northern Syria (c. 825, 750, 730 B.C.) witness to early Ancient Aramaic: KAl 25, 214, 215; TSSI -, 13, 14; J.Friedrich, Phoni- zisch-punische Grammatik, Rome 1951, 153–162; ..."

- ^ Angel Sáenz-Badillos, John Elwolde A History of the Hebrew Language 1996 0521556341 Page 35 "According to some scholars, after 1400 BC the languages which would later develop into Ya'udic and Aramaic...."

- ^ Joseph A. Fitzmyer A Wandering Armenian: Collected Aramaic Essays 1979 – Page 68 080284846X "This is partly because he refuses to see Ugaritic as Canaanite and partly because he prefers to treat so-called Ya^udic as distinct from Aramaic — if I understand him correctly.89 "

- ^ Huehnergard, John (1995). "What is Aramaic?". ARAM Periodical. 7 (2): 261–282. doi:10.2143/ARAM.7.2.2002231.

- ^ Kogan, Leonid (2015). Genealogical Classification of Semitic. de Gruyter.

- ^ Pat-El, Na'ama; Wilson-Wright, Aren (2019). "The subgrouping of Samalian: Arguments in favor of an independent branch". Maarav. 23 (2): 371–387. doi:10.1086/MAR201923206. S2CID 257837134.

- ^ أ ب ت Herrmann, Virginia R.; van den Hout, Theo; Beyazlar, Ahmet (2016). "A New Hieroglyphic Luwian Inscription from Pancarlı Höyük: Language and Power in Early Iron Age Samʾal-YʾDY". Journal of Near Eastern Studies. University of Chicago Press. 75 (1): 53–70. doi:10.1086/684835. ISSN 0022-2968. S2CID 163613753.

وصلات خارجية

- Official Zincirli Excavation Website at www.uchicago.edu

- Plans and fotos at www.hittitemonuments.com

- Levy-White project to publish small finds from German excavations

- The Aramean Kingdoms of Sam'al

- Pages using gadget WikiMiniAtlas

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- Coordinates on Wikidata

- Pages using infobox ancient site with unknown parameters

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Pages with empty portal template

- Articles with Hungarian-language external links

- مواقع أثرية في جنوب شرق الأناضول

- مدن حثية

- مدن آشورية قديمة

- مدن آرامية

- مدن سورية-حثية

- أماكن مأهولة سابقاً في تركيا

- دول وأراضي تأسست في القرن 11 ق.م.

- دول وأراضي انحلت في القرن 8 ق.م.

- دول وأراضي انحلت في 717 ق.م.

- تاريخ بلاد الشام

- تاريخ سوريا

- أماكن أثرية في سوريا