گدفري هارولد هاردي

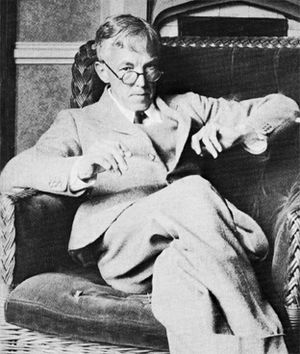

گدفري هارولد هاردي Godfrey Harold "G. H." Hardy (و. 7 فبراير 1877 – ت. 1 ديسمبر 1947) عالم رياضيات بريطاني اشتهر ب نظرية الأعداد والتحليل الرياضي.[2][3] وفي علم الأحياء، فإنه يشتهر بـ مبدأ هاردي-واينبرگ، المبدأ الأساسي في علم الوراثة السكاني.

گدفري هارولد هاردي G. H. Hardy | |

|---|---|

| |

| وُلِدَ | 7 فبراير 1877 |

| توفي | 1 ديسمبر 1947 (aged 70) كمبردج، كمبردجشاير، إنگلترة |

| الجنسية | المملكة المتحدة |

| المدرسة الأم | جامعة كمبردج |

| اللقب | Hardy-Weinberg principle Hardy–Ramanujan asymptotic formula |

| الجوائز | زميل الجمعية الملكية[1] |

| السيرة العلمية | |

| المجالات | الرياضيات |

| الهيئات | كلية ترينيتي، جامعة كامبريدج |

| المشرف على الدكتوراه | A. E. H. Love E. T. Whittaker |

| طلاب الدكتوراه | Mary Cartwright Sydney Chapman I. J. Good Edward Linfoot Frank Vigor Morley Cyril Offord Harry Pitt Richard Rado سرينيڤاسا رامانوجان Robert Rankin Donald Spencer إدوارد تشارلز تتشمارش Tirukkannapuram Vijayaraghavan E. M. Wright |

| أثـَّر عليه | Camille Jordan |

| أثـّر على | سرينيڤاسا رامانوجان |

G. H. Hardy is usually known by those outside the field of mathematics for his 1940 essay A Mathematician's Apology, often considered one of the best insights into the mind of a working mathematician written for the layperson.

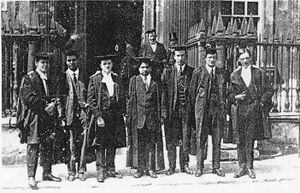

تشارلز ولسون، سرينيڤاسا رامانوجان (وسط)، گ. هـ. هاردي (أقصى اليمين)، وعلماء آخرون في كلية ترنيتي بجامعة كمبردج، حوالي ع1910 |

وبدءاً من 1914, Hardy was the mentor of the Indian mathematician سرينيڤاسا رامانوجان، a relationship that has become celebrated.[4] Hardy almost immediately recognised Ramanujan's extraordinary albeit untutored brilliance, and Hardy and Ramanujan became close collaborators. In an interview by Paul Erdős, when Hardy was asked what his greatest contribution to mathematics was, Hardy unhesitatingly replied that it was the discovery of Ramanujan.[5] In a lecture on Ramanujan, Hardy said that "my association with him is the one romantic incident in my life".[6]

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

السيرة والعمل

أعماله

Hardy is credited with reforming British mathematics by bringing rigour into it, which was previously a characteristic of French, Swiss and German mathematics.[7] British mathematicians had remained largely in the tradition of applied mathematics, in thrall to the reputation of Isaac Newton (see Cambridge Mathematical Tripos). Hardy was more in tune with the cours d'analyse methods dominant in France, and aggressively promoted his conception of pure mathematics, in particular against the hydrodynamics that was an important part of Cambridge mathematics.[بحاجة لمصدر]

From 1911, he collaborated with John Edensor Littlewood, in extensive work in mathematical analysis and analytic number theory. This (along with much else) led to quantitative progress on Waring's problem, as part of the Hardy–Littlewood circle method, as it became known. In prime number theory, they proved results and some notable conditional results. This was a major factor in the development of number theory as a system of conjectures; examples are the first and second Hardy–Littlewood conjectures. Hardy's collaboration with Littlewood is among the most successful and famous collaborations in mathematical history. In a 1947 lecture, the Danish mathematician Harald Bohr reported a colleague as saying, "Nowadays, there are only three really great English mathematicians: Hardy, Littlewood, and Hardy–Littlewood."[8]

Hardy is also known for formulating the Hardy–Weinberg principle, a basic principle of علم الوراثة السكاني, independently from Wilhelm Weinberg in 1908. He played cricket with the geneticist Reginald Punnett, who introduced the problem to him in purely mathematical terms.[9] Hardy, who had no interest in genetics and described the mathematical argument as "very simple", may never have realised how important the result became.[10]

Hardy's collected papers have been published in seven volumes by Oxford University Press.[11]

الرياضة البحتة

Hardy preferred his work to be considered pure mathematics, perhaps because of his detestation of war and the military uses to which mathematics had been applied. He made several statements similar to that in his Apology:

I have never done anything "useful". No discovery of mine has made, or is likely to make, directly or indirectly, for good or ill, the least difference to the amenity of the world.[12]

However, aside from formulating the Hardy–Weinberg principle in علم الوراثة السكاني, his famous work on integer partitions with his collaborator Ramanujan, known as the Hardy–Ramanujan asymptotic formula, has been widely applied in physics to find quantum partition functions of atomic nuclei (first used by Niels Bohr) and to derive thermodynamic functions of non-interacting Bose–Einstein systems. Though Hardy wanted his maths to be "pure" and devoid of any application, much of his work has found applications in other branches of science.[بحاجة لمصدر]

Moreover, Hardy deliberately pointed out in his Apology that mathematicians generally do not "glory in the uselessness of their work," but rather – because science can be used for evil ends as well as good – "mathematicians may be justified in rejoicing that there is one science at any rate, and that their own, whose very remoteness from ordinary human activities should keep it gentle and clean."[13] Hardy also rejected as a "delusion" the belief that the difference between pure and applied mathematics had anything to do with their utility. Hardy regards as "pure" the kinds of mathematics that are independent of the physical world, but also considers some "applied" mathematicians, such as the physicists Maxwell and Einstein, to be among the "real" mathematicians, whose work "has permanent aesthetic value" and "is eternal because the best of it may, like the best literature, continue to cause intense emotional satisfaction to thousands of people after thousands of years." Although he admitted that what he called "real" mathematics may someday become useful, he asserted that, at the time in which the Apology was written, only the "dull and elementary parts" of either pure or applied mathematics could "work for good or ill."[13]

المواقف والسمات

مأثورات هاردي

- It is never worth a first-class man's time to express a majority opinion. By definition, there are plenty of others to do that.[14]

- A mathematician, like a painter or a poet, is a maker of patterns. If his patterns are more permanent than theirs, it is because they are made with ideas.[13]

- We have concluded that the trivial mathematics is, on the whole, useful, and that the real mathematics, on the whole, is not.[13]

- Galois died at twenty-one, Abel at twenty-seven, Ramanujan at thirty-three, Riemann at forty.[أ] There have been men who have done great work a good deal later; Gauss's great memoir on differential geometry was published when he was fifty (though he had had the fundamental ideas ten years before). I do not know an instance of a major mathematical advance initiated by a man past fifty.[13][16][17]

- Hardy once told Bertrand Russell "If I could prove by logic that you would die in five minutes, I should be sorry you were going to die, but my sorrow would be very much mitigated by pleasure in the proof".[18]

- A chess problem is genuine mathematics, but it is in some way 'trivial' mathematics. However, ingeniuous and intricate, however original and surprising the moves, there is something essential lacking. Chess problems are unimportant. The best mathematics is serious as well as beautiful - 'important.'[13]

أعداد سيارات الأجرة

- مقالة مفصلة: رقم التاكسي

عام 1919، استقل گدفري هاردي ذات مرة سيارة أجرة لزيارة مساعده، عالم الرياضيات الهندي سرينيڤاسا رامانوجان، في المستشفى.[19]

وأشار هاردي إلى أن رقم سيارة الأجرة، 1729، بدا "مملاً إلى حد ما"، مما دفع رامانوجان للرد بأنه على العكس من ذلك، فإن الرقم "مثيراً للاهتمام للغاية" لأنه كان أصغر عدد يمكن التعبير عنه كمجموع عددين مكعبين بطريقتين مختلفتين:

1729 = 1³ + 12³ = 9³ + 10³.

منذ ذلك الحين، الأرقام التي يمكن التعبير عنها بهذه الطريقة أصبحت تُعرف باسم "رقم التاكسي".[20][21]

إشارات ثقافية

Hardy is a key character, played by Jeremy Irons, in the 2015 film The Man Who Knew Infinity, based on the biography of Ramanujan with the same title.[22] Hardy is a major character in David Leavitt's fictive biography, The Indian Clerk (2007), which depicts his Cambridge years and his relationship with John Edensor Littlewood and Ramanujan.[23] Hardy is a secondary character in Uncle Petros and Goldbach's Conjecture (1992), a mathematics novel by Apostolos Doxiadis.[24] Hardy is also a character in the 2014 Indian film, Ramanujan, played by Kevin McGowan.

قائمة المراجع

- Hardy, G. H. (1940). A Mathematician's Apology. Cambridge: University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-42706-7 (2004 reissue)..

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help) - Hardy, G. H. (1940) Ramanujan, Cambridge University Press: London (1940). Ams Chelsea Pub. (25 November 1999) ISBN 0-8218-2023-0.

- Hardy, G. H.; Wright, E. M. (2008) [1938]. Heath-Brown, D. R.; Silverman, J. H. (eds.). An Introduction to the Theory of Numbers (6th ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-921985-8.

- Hardy, G. H. (1952) [1908]. A Course of Pure Mathematics (10th ed.). Cambridge: University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-72055-7 (2008 reissue).

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help) - Hardy, G. H. (1949). Divergent Series. Oxford: Clarendon Press. xvi+396. ISBN 978-0-8218-2649-2. MR 0030620.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|nopp=ignored (|no-pp=suggested) (help)[25] - Hardy, G. H. (1966). Collected papers of G.H. Hardy; including joint papers with J.E. Littlewood and others. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-853340-3. OCLC 823424.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Hardy, G. H.; Littlewood, J. E.; Pólya, G. (1952) [1934]. Inequalities (2nd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-35880-4.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

انظر أيضاً

- Critical line theorem

- Campbell–Hardy theorem

- Hardy hierarchy

- Hardy notation

- Hardy space

- Hardy–Hille formula

- Hardy–Littlewood definition

- Hardy–Littlewood inequality

- Hardy–Littlewood maximal function

- Hardy–Littlewood tauberian theorem

- Hardy–Littlewood zeta-function conjectures

- Hardy–Ramanujan Journal

- Hardy–Ramanujan number

- Hardy–Ramanujan theorem

- Hardy's inequality

- Hardy's theorem

- Hardy field

- Hardy Z function

- Pisot–Vijayaraghavan number

- Ulam spiral

ملاحظات

المصادر

- ^ DOI:10.1098/rsbm.1949.0007

This citation will be automatically completed in the next few minutes. You can jump the queue or expand by hand - ^ O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "گدفري هارولد هاردي", MacTutor History of Mathematics archive

- ^ گدفري هارولد هاردي at the Mathematics Genealogy Project

- ^ THE MAN WHO KNEW INFINITY: A Life of the Genius Ramanujan Archived 5 ديسمبر 2017 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 2 December 2010.

- ^ Alladi, Krishnaswami (19 December 1987), "Ramanujan—An Estimation", The Hindu, Madras, India, ISSN 0971-751X. Cited in Hoffman, Paul (1998), The Man Who Loved Only Numbers, Fourth Estate, pp. 82–83, ISBN 1-85702-829-5

- ^ Hardy, G. H. (1999). Ramanujan: Twelve Lectures on Subjects Suggested by his Life and Work. Providence, RI: AMS Chelsea. ISBN 978-0-8218-2023-0.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماة:0 - ^ Bohr, Harald (1952). "Looking Backward". Collected Mathematical Works. Vol. 1. Copenhagen: Dansk Matematisk Forening. xiii–xxxiv. OCLC 3172542.

- ^ Punnett, R. C. (1950). "Early Days of Genetics". Heredity. 4 (1): 1–10. doi:10.1038/hdy.1950.1.

- ^ Cain, A. J. (2019). "Legacy of the Apology". An Annotated Mathematician's Apology. By Hardy, G. H.

- ^ Hardy, Godfrey Harold (1979). Collected Papers of G. H. Hardy – Volume 7. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-853347-0.

- ^ Titchmarsh, E.C. (1950). "Godfrey Harold Hardy". J. London Math. Soc. 25 (2): 81–138. doi:10.1112/jlms/s1-25.2.81.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح Hardy, G. H. A Mathematician's Apology, 1992 [1940]

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةsnow67 - ^ Hardy, G. H. An Annotated Mathematician's Apology. With annotations and commentary by Alan J. Cain. 2019, annotations to §4.

- ^ "Who Says Scientists Peak By Age 50?". Next Avenue (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). 5 August 2014. Retrieved 2 September 2020.

- ^ Guterman, Lila. "Are Mathematicians Past Their Prime at 35?". www.massey.ac.nz. Retrieved 2 September 2020.

- ^ Quoted in Bertrand Russell, Logical and Philosophical Papers, 1909–13, Routledge, 1992, p. xxix.

- ^ "taxicab numbers". PhysInHistory. 2024-01-20. Retrieved 2024-01-20.

- ^ Quotations by G. H. Hardy, MacTutor History of Mathematics Archived 2012-07-16 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Silverman, Joseph H. (1993). "Taxicabs and sums of two cubes". Amer. Math. Monthly. 100 (4): 331–340. doi:10.2307/2324954. JSTOR 2324954.

- ^ George Andrews (February 2016). "Film Review: 'The Man Who Knew Infinity'" (PDF). Notices of the American Mathematical Society.

- ^ Taylor, D. J. (26 January 2008). "Adding up to a life. Review of The Indian Clerk by David Leavitt". The Guardian. Retrieved 21 April 2016.

- ^ Devlin, Keith (1 April 2000). "Review: Uncle Petros and Goldbach's Conjecture by Apostolos Doxiadis". Mathematical Association of America. Retrieved 21 April 2016.

- ^ Szász, Otto (1950). "Book Review: G. H. Hardy, Divergent series". Bull. Amer. Math. Soc. 56 (5): 472–473.

قراءات أخرى

- Kanigel, Robert (1991). The Man Who Knew Infinity: A Life of the Genius Ramanujan. New York: Washington Square Press. ISBN 0-671-75061-5.

- Snow, C. P. (1967). Variety of Men. London: Macmillan

وصلات خارجية

- O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "گدفري هارولد هاردي", MacTutor History of Mathematics archive

- Quotations of G. H. Hardy

- Hardy's work on Number Theory

- Weisstein, Eric W., Hardy, Godfrey Harold (1877–1947) at ScienceWorld.

- I. Grattan-Guinness, "The interest of G.H. Hardy, F.R.S. in the philosophy and the history of mathematics"