سكة حديد فلسطين

سكك حديد فلسطين (بالعبرية: מסילות ברזל פלשתינה (א"י) "سكك حديد (أرض إسرائيل) فلسطين" أو רכבות ארץ-ישראל "سكك حديد أرض إسرائيل" أو הרכבת המנדטורית "السكك الحديدية الانتدابية")، هي شركة سكك حديدية حكومية تدير جميع السكك الحديدية العامة في فلسطين أثناء الانتداب البريطاني من عام 1920 حتى 1948. كان الخط الرئيسي بها يصل القنطرة في مصر مع حيفا. وكان هناك فروع تخدم يافا، القدس، عكا، ومرج بن عامر.

خلفية

سكك حديد يافا-القدس

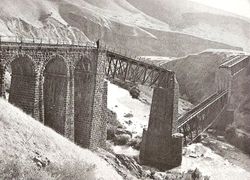

سكك حديد يافا-القدس، أسستها Chemin de Fer Ottoman de Jaffa à Jérusalem et Prolongements، وكانت أول سكك حديدية تبنى في فلسطين. بدأ انشاءها في 31 مارس 1890 وأُفتتحت في 26 سبتمبر 1892.[2] بُنيت بعرض 1٬000 mm (3 ft 3 3⁄8 in) مع العديد من المنحنيات الضيقة وتدرج حاكم بنسبة 2% (1 في 50).[2] الجزء الشرقي من الخط، في تلال يهودا بين دير أبان والقدس، شديد الانحدار والتعرج بشكل خاص. كانت أول قاطرات "J&J" عبارة عن أسطول مكون من خمسة 2-6-0 قاطرات موگل من إنتاج شركة بالدوينز الأمريكية، تم تسليمها عامي 1890 و1892.[3] في عدد من المناسبات، قامت عجلات بالدوين السداسية المقترنة إما بنشر القضبان أو انحرفت عن مسارها عند المنحنيات الضيقة. مع زيادة حركة المرور، حصلت شركة J&J على أربعة 0-4-4-0 قاطرت ماليه من شركة بورسيگ الأمانية، تم تسليمها بين عامي 1904 و1914.[3] كان الهدف من قاطرات ماليه الحصول على جهد جر أكبر دون نشر القضبان، لكنها عانت أيضًا من عدد من الانحرافات.

عام 1915، أثناء الحرب العالمية الأولى، قام الجيش العثماني بتوسيع مقياس المسار بين اللد والقدس إلى 1٬050 mm (3 ft 5 11⁄32 in) للسماح بالمرور مع سكة حديد الحجاز وإزالة المسار بين اللد ويافا للاستخدام العسكري في مكان آخر.[4]

عام 1921، نظرت الحكومة البريطانية لفلسطين بجدية في كهربة الخط. كان بنحاس روتنبرگ، صاحب امتياز الكهرباء في فلسطين، مدعومًا من قبل المفوض السامي صموئيل في اقتراحه أن كهربة الخط لن تكون مربحة فحسب، بل ستكون أيضًا ضرورية لكهربة البلاد ككل. لكن مكتب المستعمرات تراجع خوفاً من التكاليف الباهظة لهذا المشروع.[5]

سكك حديد مرج بن عامر

كان هذا الخط متفرع من سكك حديد الحجاز ويصل بين حيفا ودرعا في جنوب سوريا عند انضمامه لخط الحجاز الرئيسي. بدأ الانشاء في حيفا عام 1902 واكتب في درعا عام 1905.[6] خط مرج بن عامر، مثل خط الحجاز الرئيسي، بنُي بسعة 1٬050 mm (3 ft 5 11⁄32 in). عام 1808 بدأ إنشاء التفريعة من العفولة على خط مرج بن عامر وصولاً إلى القدس، ووصل نابلس مع اندلاع الحرب العالمية الأولى عام 1914.[7]

السكك الحديدية العسكرية العثمانية

كانت الدولة العثمانية في حاجة إلى إمداد قواتها التي تسيطر على حدود فلسطين ضد القوات البريطانية وقوات الإمبراطورية في مصر. لم يكن من الممكن استكمال خط السكة الحديد المزمع من نابلس عبر التضاريس الجبلية إلى القدس في الوقت المناسب، لذلك منذ عام 1915 أشرف مهندس السكك الحديدية الألماني هاينريش أوگست ميسنر على بناء خط بسعة 1٬050 mm (3 ft 5 11⁄32 in) باتجاه الغرب من المسعودية إلى طولكرم.[4] أصبحت التضاريس أسهل بكثير من طولكرم، وبُني خط باتجاه الشمال إلى الخضيرة وجنوباً إلى اللد حيث انضم إلى J&J وأصبح يُعرف فيما بعد باسم السكك الحديدية الشرقية. استخدم مسار J&J الموسع (انظر أعلاه) حتى وادي صرار حيث تشعب جنوبًا باتجاه خط الجبهة العثماني. بحلول أكتوبر 1915، كان الخط يعمل جنوباً حتى بئر السبع.[4] كما بُني فرع من التينة جنوب وادي صرار مباشرة حتى دير سنيد، حيث تفرع مرة أخرى إلى بيت حانون وهوج بالقرب من غزة.[4] كما قام العثمانيون بتوسيع سكك حديد بئر السبع إلى سيناء وصولاً إلى القسيمة.

سكك حديد سيناء العسكرية

تشكلت قوة التجريدة المصرية من الوحدات البريطانية في مارس 1916. وبدأت في بناء سكك حديد سيناء القياسية من القنطرة على قناة السويس عبر سيناء، وصولاً إلى رمانة بحلول مايو 1916،[8] والعريش في يناير 1917[9] ورفح في مارس 1917.[10]

اقترضت SMR عربات السكك الحديدية و70 قاطرة من سكك الحديد المصرية بما في ذلك 20 قاطرة من روبرت ستيفنسون 0-6-0، و20 قاطرة بالدوين 2-6-0 و15 قاطرة بالدوين 4-4-0.[11] كما حصلت SMR على سبع من قاطرات التحويل الصغيرة: اثنتان 0-6-0ST تانك سادل بُنيت عام 1900 و1902 استخدمتها بارون أول|جون أيرلد[11] في مشروع هندسة مدنية بمصر (ربما [[قناطر أسيوط)، وأربع قاطرات 0-6-0ST بُنيت عام 1917 لإدارة الممرات المائية والأرصفة الداخلية في بريطانيا وقاطرة ألمانية 0-6-0WT كانت جزءًا من شحنة سفينة تجارية استولت عليها البحرية الملكية عام 1914.[12] بُنيت القاطرة الألمانية بواسطة شركة هانوماگ في هانوڤر عام 1913[13] وبُنيت جميع قاطرات سادل بواسطة مانينگ واردل في ليدز، إنگلترة.[11]

سكك حديد فلسطين العسكرية

استولت قوة التجريدة المصرية على بئر السبع في أكتوبر 1917 وغزة في نوفمبر.[14] قام مهندسو التجريدة المصرية بتمديد سكك حديد سيناء العسكرية إلى دير سنيد بحلول نهاية نوفمبر 1917 وفرع إلى بئر السبع بحلول مايو 1918،[15] وتحويل التفريعة إلى القدس بحلول يونيو[16] وتوصيله حتى طولكرم على خط السكة الحديد الشرقي. من هناك قاموا ببناء خط السكك الحديدية القياسي على طريق جديد في الاتجاه الشمال الغربي إلى الساحل ثم شمالًا، وصولاً إلى حيفا بحلول نهاية 1918.[17]

مع تقدم قوة التجريدة المصرية إلى فلسطين، شكلت منظمة جديدة، سكة حديد فلسطين العسكرية، لتشغيل السكك الحديدية المختلفة لمختلف المقاييس التي أصبحت تحت سيطرتها. أعادت وحدات الهندسة الملكية خطوط سكك حديد فلسطين لتكون صالحة للعمل.[18] قامت PMR ببناء عددًا من مؤقتًا من خطوط السكك الحديدية الضيقة، بما يتضمن خطاً بين اللد ويافا[10] على مجنزرة J&J كان الجيش العثماني قد أزال منها مسار بعرض 1٬000 mm (3 ft 3 3⁄8 in) metre gauge عام 1915. اقترضت PMR عدة قضبان ضيقة بعرض 1٬050 mm (3 ft 5 11⁄32 in)، التي كانت ضيقة للغاية.

التشغيل

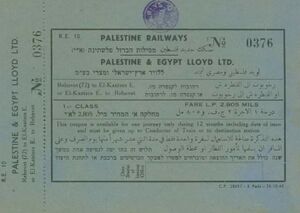

في أبريل 1920، كلف مؤتمر سان ريمو المملكة المتحدة بإدارة فلسطين: قرار أيده انتداب عصبة الأمم عام 1922. في أكتوبر 1920، نُقلت إدارة السكك الحديدية حسب الأصول من شركة سكك حديد فلسطين العسكرية إلى شركة جديدة، سكك حديد فلسطين (PR)، المملوكة لحكومة الانتداب البريطاني.[10][19] طوال العمليات العسكرية التي خاضتها الدولة العثمانية والامبراطورية البريطانية، ظلت سكة حديد يافا-القدس ملكًا للشركة الفرنسية "Société du Chemin de Fer Ottoman de Jaffa à Jérusalem et Prolongements". طلب الفرنسيون 1.5 مليون جنيه إسترليني من البريطانيين لصالح شركة J&J، لكن بعد التحكيم وافقوا على دفع 565.000 جنيه إسترليني على دفعات.[19] تم تحويل قسم اللد-يافا من 600 مم إلى السكك الحديدية القياسية وأعيد افتتاحه في سبتمبر 1920.[16]

نظرًا لأن الخط الرئيسي لسكك حديد فلسطين بين الشمال والجنوب قد مُد بسرعة للأغراض العسكرية وكانت خطوطه يافا-القدس ومرج بن عامر منحرة بشكل حاد، لم تكن قطاراتها سريعة جدًا. كان الحد الأقصى للسرعة 80 كم/س وحتى أفضل قطاراتها كانت تسير بسرعة 48 كم/س بين المحطات.[20]

من عام 1920 قامت سكك حديد فلسطين بتطوير رحلة قطارات يومية مختلطة بين يافا والقنطرة.[19] ووفرت ويجون-ليت مطعماً وعربات النوم ثلاثة أيام في الأسبوع حتى عام 1923ن عندما تم زيادة الخدمة الفاخرة بشكل يومي.[19]

افتقرت فلسطين إلى ميناء بحري عميق المياه حتى عام 1933 عندما بُني ميناء في حيفا. حتى ذلك الحين، كانت البضائع التي لا تستطيع الموانئ الفلسطينية مناولتها تمر عبر ميناء بورسعيد في مصر.[21] قامت السكك الحديدية المصرية بنقل البضائع بين بورسعيد والقنطرة، ثم تنقلها سكك الحديد الفلسطينية بين القنطرة شرق وفلسطين.[21] لم تُبنى أي جسور عبر قناة السويس حتى عام 1941، لذلك كانت الشحنات تُنقل عبر القناة بين محطتي ESR وسكك حديد فلسطين على الضفة المقابلة في القنطرة. كان من الممكن أن يشمل ذلك عمليات تسليم القاطرات وعربات السكك الحديدية إلى سكك حديد فلسطين.

العشرينيات والثلاثينيات انخفضت حركة ركاب سكك حديد فلسطين بشكل ملحوظ. أدت المنافسة من أعداد متزايدة من السيارات الخاصة إلى خفض حركة الركاب من الدرجة الأولى ثم الدرجة الثانية، بحيث بحلول عام 1934، كان 95% من الركاب المتبقين من الدرجة الثالثة.[22] أثر الكساد الكبير في بدايته عام 1929 بشدة على حركة السياحة، والذي لم تتعافى منه أبداً سكك حديد فلسطين.[22]

لجنة پول

مع تدهور الأوضاع المالية لسكك حديد فلسطين، عام 1934 عينت حكومة المملكة المتحدة لجنة تحقيق بقيادة السير فليكس پول، الرئيس السابق لسكك حديد گريت ويسترن البريطانية.[22] كان لپول أيضًا مهمة محددة تتمثل في تقديم المشورة لتحسين المحطات ومسار السكك الحديدية لتحسين اوصلات بين يافا وتل أبيب وحيفا.[23] كان الأعضاء الآخرون في لجنة پولهم س. جنكين جونز من سكك حديد لندن ونورث وسترن البريطانية والمحاسب السير لورانس هالسي، الذي كان شريكًا في پرايس واترهاوس.[23] كانت مهمة جنكين-جونز المحددة هي تقديم المشورة حول كيفية تطوير مرافق المرور وتنظيمه وتحديد معدلات الشحن.[23] كان على هالسي تقديم المشورة بشأن نظام المحاسبة والحصول على تمويل تجديد مناسب.[23]

عانت شركة سكك حديد فلسطين في السنة المالية 1934-1935 من عجز صافٍ قدره 87.940 جنيه إسترليني.[23] لاحقاً عام 1935، نشرت لجنة پول تقريرها،[22] والذي كان في الواقع ثلاثة تقارير ذات صلة من أعضاء اللجنة الثلاثة.[23] دعت توصيات كل عضو إلى استثمارات كبيرة.[23] انتقد پول الطريقة التي تم بها تشغيل السكك الحديدية حول التقاطع المركزي الرئيسي في اللد.[22] وحددت نقصًا خطيرًا في الاستثمار، وذكرت أن محطتي يافا وتل أبيب كانت "غير كافية وغير مناسبة" و"كان الازدحام المروري كبيرًا" حول اللد.[22] اضطر المسافرون بين حيفا وتل أبيب أو يافا إلى تغيير قطارهم في اللد، الأمر الذي لم يكن ملائمًا للركاب ومسببًا للازدحام في محطة اللد.

لذلك أوصت لجنة پول ببناء خطي ربط جديدين من تل أبيب لتجاوز اللد: خط شمالي إلى المجدل على خط حيفا الرئيسي لإنشاء مسار مباشر بين حيفا-تل أبيب-يافا[22] وآخر جنوبي عبر ريشون لتصيون وعبر خط القنطرة الرئيسي عند رحوڤوت إلى تقاطع مع خط القدس عند نيعانا.[24]

في يوليو 1935 في مجلس العموم البريطاني، توجه البرلماني الليبرالي بارون جانر بسؤاله إلى وزير الدولة للمستعمرات مالكولم ماكدونالد:

"ما إذا كان على علم بالاستياء من الخدمات الحالية التي تقدمها سكك حديد فلسطين. وما إذا كان بإمكانه الآن تقديم تأكيد بأنه نتيجة للتحقيق الرسمي الأخير في هذه المسألة، سيتخذ إجراء تصحيحي خلال العام الحالي؟"[23]

وأجاب ماكدونالد:

"حتى سنوات قليلة ماضية، قيد الوضع المالي لفلسطين الإنفاق على صيانة السكك الحديدية وتحسينها، لكن الإيرادات الإضافية متاحة الآن وقد تم بالفعل تخصيص مبالغ كبيرة بالفعل وهي على وشك إنفاقها لهذا الغرض. سيتخذ أي إجراء آخر قد يتبين أنه ضروري ناشئ عن استفسارات الخبراء الأخيرة في أقرب وقت ممكن".[23]

على الرغم من وعد ماكدونالدز، لم تحصل العلاقات العامة على رأس المال اللازم ولم يتم إنشاء أي من الخطوط المقترحة من قبل شركة سكك حديد فلسطين. الامتداد الوحيد الذي أوصى به پول وشركة سكك حديد فلسطين كان امتدادًا قصيرًا للشحن من محطة يافا إلى المرفأ.[24] كان ميناء يافا مقيدًا بالصخور الخطرة لدرجة أنه لم تتمكن سوى السفن الصغيرة فقط من دخوله؛ كانت سفن الشحن العابرة للمحيطات ترسو بعيدًا عن الشاطئ وتنقل حمولتها من وإلى الأرصفة بواسطة الصنادل. لم تُنفذ توصية پول لإعادة بناء المرفأ، ونتيجة لذلك لم يتلق خط الشحن الجديد التابع لسكك حديد فلسطين سوى القليل من الفائدة.[24]

Locomotives

Palestine Military Railway locomotives

For standard gauge use overseas the British Government requisitioned many London and North Western Railway "Coal Engine" 0-6-0s and 50 London and South Western Railway 395 Class 0-6-0s. The British Government sent 42 LNWR and 36 LSWR locomotives to the PMR[25]

In 1918 the PMR ordered 50 new locomotives. British factories were fully occupied so the order was placed with Baldwin in the USA.[26] They were 4-6-0s of a simple wartime design, widely used elsewhere including on railways in Belgium.[26] The first ten were delivered to Palestine in April 1919.[27] They had 5 ft 2 in (1،570 mm) driving wheels suitable for mixed traffic use.[28]

The PMR suffered at least one serious accident. In about 1918 the older of the Manning Wardle saddle tanks that the PMR had acquired from J. Aird & Co. was shunting at Jerusalem when the weight of its train became too much for it to hold on the gradient.[12] The train ran away downhill towards Bittir and collided with an LSWR 395 Class that was climbing towards Jerusalem.[12] The resulting collision "practically demolished" the saddle tank.[12]

Palestine Railways locomotives

The LNWR 0-6-0s were old, worn out and performed very badly in Palestine, so PR retired all of them for scrap by 1922.[26] The LSWR 0-6-0s performed better,[25] so PR kept most of them in service until 1928[26] and retained the last nine as shunting locomotives until 1936.[29]

M class

The four Manning Wardle saddle tanks from the Inland Waterways and Docks Department were identical so PR designated them class M.[12] These were satisfactory as shunting locomotives and PR kept them in service for many years.[12] The J. Aird & Co. Manning Wardles were dissimilar and the PMR had already lost the older one in 1918 in a collision on the Jerusalem branch with an LSWR 395 class (see above).[12] PR disposed of the Hanomag well tank and the former Aird 1902 Manning Wardle for scrap in 1928.[28]

K class

The Baldwin 4-6-0 locomotives were successful on most of Palestine's standard gauge network but could not haul adequate loads on the steep gradients from Jaffa via Lydda to Jerusalem. In 1922 PR obtained six engines from Kitson and Company in Leeds, England, specifically designed to be powerful enough for the Jerusalem service. They were 2-8-4T tank locomotives designated class K. They had 4 ft 0 in (1،220 mm) driving wheels,[28] a diameter suitable for low-speed freight work and also for mountain gradients. The track gauge on the tight curves on the Jerusalem branch was widened from 1٬435 mm (4 ft 8 1⁄2 in) to as much as 4 ft 9.75 in (1،467 mm)[30] but unfortunately even with this adjustment the heavy eight-coupled class K was unsuitable and suffered a number of derailments.

H, H2 and H3 classes

PR designated the Baldwin 4-6-0s class H. In 1926 six were shipped to Armstrong Whitworth and Company in Newcastle upon Tyne, England who rebuilt them as 4-6-2T tank locomotives, designated class H2.[31] In 1933 PR opened its own railway workshops in Haifa.[32] In 1937, with the help of some parts supplied by Nasmyth, Wilson and Company in Salford, England, the Qishon works converted five class H 4-6-0s to 4-6-4T tank locomotives,[33][34] designated class H3.

Sentinels

In 1928 PR bought one vertical-boilered 0-4-0T shunting locomotive[35] and two vertical-boilered steam-powered railcars for local services from Sentinel-Cammell in Shrewsbury, England.[31] Each railcar unit had two coach bodies articulated over three bogies. The shunter was capable of only light duties and by the end of the Second World War PR had stored it out of use.[35] PR found the railcar format inflexible, as if passenger numbers exceeded the capacity of a railcar it was not practical to couple up an extra coach.[36] In 1945 PR removed the Sentinel engines and converted the railcars to ordinary coaching stock.[37]

N class

After 1928 PR retained a few 395 class 0-6-0s for shunting, but they were approaching 50 years old so in 1934 PR obtained three purpose-built 0-6-0T shunting locomotives from Nasmyth, Wilson to start replacing them.[35] These were designated class N and PR took delivery of seven more in the period 1935–38.[35]

P class

H class 4-6-0s hauled the Haifa – El Kantara service until 1935, when the North British Locomotive Company in Glasgow, Scotland supplied six more powerful 4-6-0s that PR designated class P.[35] These had a tractive effort of 28،470 lbf (126.6 kN): 16% more than the 24،479 lbf (108.9 kN) of classes H, H2 and H3.[28] Class P also had 5 ft 6+3⁄4 in (1،695 mm) driving wheels:[28] a mixed-traffic diameter by British standards but larger than those of the H series and therefore more suitable for higher speed traffic.

القدرة التشغيلية

عانت سكك حديد فلسطين من فشل متكرر في القاطرات. عام 1934، بلغ متوسط فشل قاطراتها 12.650 كم، في حين أن كان الرقم في بريطانيا العظمى لنفس العام 141.991 كم.[38]

تسبب خطأ الموظفين في 17% من حالات الأعطال، لكن كان سبب أكبر بكثير وهو نقص المياه، والذي ذكر المدير العام لسكك حديد فلسطين أنه "الأكثر إلحاحًا من بين جميع مشاكل السكك الحديدية".[38] سعت سكك حديد فلسطين إلى لتخفيف من ذلك من خلال بناء محطات لتليين المياه في نقاط الري الرئيسية على شبكتها، وفحص المياه كيميائياً بشكل متكرر وفي النهاية تركيب جميع القاطرات بجهاز نفخ يمكن للسائق بواسطته تطهير الحمأة من المرجل.[39]

قاطرات الحرب العالمية الثانية

البخارية

PR had fuelled its locomotives with Welsh coal[29] but in June 1940 Italy declared war on the Allies and France surrendered to Germany and Italy, leaving the Mediterranean extremely dangerous for British merchant shipping. Early in 1942 PR belatedly began to convert its locomotives to burn oil,[40] but it did not complete the conversion programme until 1943.[29]

In 1941 Britain started to supply two types of 2-8-0 Consolidation freight locomotive to its Middle East Command. One was the ROD 2-8-0 class that had been designed in 1911 as the Great Central Railway Class 8K and that the UK's War Department (WD) had adopted as a standard design to be mass-produced for military traffic in the First World War. The other was the London, Midland and Scottish Railway Stanier 8F that had been designed in 1935 and that the WD now adopted as a standard design to be mass-produced for military use in the Second World War.

As Allied forces concentrated on defending Egypt and the Suez Canal from Italian and German attack the first shipments of 2-8-0s were delivered to Egypt,[41] but in March 1942 both types started to arrive in Palestine and by June 1942 24 ROD locomotives were working on PR and the Haifa – Beirut – Tripoli (HBT) line.[42] In 1944-45 the ROD locomotives were transferred out of Palestine and replaced by LMS locomotives[42] that had been in service on the Trans-Iranian Railway.[43] Other LMS locomotives were overhauled in Palestine in 1944 before being deployed either elsewhere in the Middle East or to the part of Italy now under Allied control.[44]

In the second half of 1942 the USA started to supply locomotives to the British Middle East Command. By December 1942, 27[42] USATC S200 Class 2-8-2 Mikados were working the PR and HBT main lines and two[42] USATC S100 Class 0-6-0T switchers were supplementing PR's shunting fleet.

الديزل

By June 1943 12 Whitcomb 65-DE-14[45] 650 HP diesel-electric locomotives from the USA were working on the HBT and by 12 December more were working on the PR.[42] The latter were an effective replacement for PR's Baldwins on the steeply-graded Jerusalem line[46] but within a few months all had been transferred to double the diesel fleet on the HBT.[42] Whitcomb diesels were the HBT's principal motive power until the middle of 1944[46] when they were replaced with ROD 2-8-0s[42] and transferred to Italy.[47]

1936–39 Arab Revolt

In 1936–39 Palestinian Arabs opposed to Jewish mass immigration revolted against British rule. Railways were a particular target for sabotage.[48] The British built blockhouses to protect bridges and regular military patrols of railway lines.[49] Patrols were initially on foot, then in armoured freight vans propelled by locomotives with armoured cabs, and finally with dozens of rail-mounted armoured cars built at Qishon works.[50] After one was blown up by a mine, killing a soldier, the front of each armoured car was fitted with a long bar propelling a pony truck intended to detonate any mine safely without injuring any of the armoured car's occupants.[51] British soldiers made Arab hostages ride on the pony truck so that any mine would be likely to kill them.[51][52]

Security measures failed to stop attacks on the railway. One attack damaged a Sentinel railcar.[51] In October 1937 a more serious attack damaged a passenger train and prompted a further decline in passenger numbers.[51] In 1938 sabotage derailed 44 trains, damaged 33 rail-mounted armoured cars, destroyed 27 stations and other buildings, damaged 21 bridges and culverts and destroyed telephone and signalling equipment and water supplies.[51] A member of the Survey of Palestine recalled that "nearly all the stations on the railway had been burnt".[52] For more than one period night running became so dangerous that it was suspended.[53] In September 1938 first the Jerusalem line and then El Kantara line were closed by extensive sabotage.[53] After the latter was reopened in October, Haifa – El Kantara trains were run only three days per week compared with the previous daily service.[54] The worst year was 1938, in which 13 railway workers were killed and 123 injured.[54]

World War II extensions and operations

During the Second World War traffic on PR increased dramatically from 1940 to 1945.[55] The PR main line was a supply route for the North African Campaign that lasted from the Italian attack on Egypt in 1940 until the German surrender in Tunisia in May 1943. In April – May 1941 the Italian air force and German Luftwaffe used Vichy French air bases in the mandated territories of Syria and Lebanon as staging posts to support Rashid Ali's coup d'état against Iraq's pro-British government. British and Empire forces landed in southern Iraq and overthrew the coup in the brief Anglo-Iraqi War of May 1941. Then in June and July 1941 PR served as a supply route for the British Empire invasion of Vichy Syria and Lebanon.

PR suffered relatively few enemy air attacks.[56] In 1941 Haifa suffered several air raids, one of which left an unexploded bomb within a few yards of the line.[56] The last significant air attack on the railway was late in 1942, damaging the rail link to Haifa port.[56] The attacks killed one railway worker and wounded ten more.[56]

Suez canal area

In June 1941 Australian Royal Engineers started building a line alongside the Suez Canal southwards from PR's terminus at El Kantara.[57] In July 1941 they connected the new line with Egyptian State Railways (ESR) by a swing bridge at El Ferdan across the canal.[57] In August 1941 PR started operating a through service between Haifa and Cairo.[57] Construction of the line beside the canal continued until July 1942 when it reached El Shatt.[57] ESR then took over operation of the completed route.[57]

Haifa – Beirut – Tripoli (HBT) line

South African Army engineers built the first section of a new Haifa – Beirut – Tripoli (HBT) railway, branching off the 1050 mm gauge Haifa – Acre line and running along the rocky coast and through two tunnels to Beirut.[55] For its construction the HBT initially used 1050 mm gauge track throughout the Haifa – Beirut section for through running of traffic carrying railway construction materials.[58] The South Africans were transferred to other duties and the Haifa – Beirut section was completed by the New Zealand Railway Group.[58] The New Zealand Railway Group also operated the 1050 mm gauge Jezreel Valley railway between Haifa and Daraa on the Syrian border,[59] the Daraa – Damascus section of the 1050 mm gauge Hejaz Railway main line[59] and 60 ميل (97 km) of branch lines including the 1050 mm line between Afula on the Jezreel Valley railway, Nablus, and Tulkarm on the main line between Haifa and Lydda.[59] The Afula – Mas'udiya service ended in 1932, and the Tulkarm – Mas'udiya – Nablus service in 1938, except for a 5 km dual gauge section between Tulkarm and the ballast quarries at Nur Shams.[32][60]

By August 1942, the Haifa – Beirut section was complete, the track was converted to standard gauge,[58] and the stretch between Haifa and Acre, which was shared with the Jezreel Valley railway, to dual gauge.[61] The new railway line started carrying through military traffic between Egypt, Palestine and Lebanon.[58] By then Australian Royal Engineers were already building the Beirut – Tripoli section, which they completed in December 1942.[58] PR operated the HBT between Haifa and Az-Zeeb[58] just south of the Lebanese border and the British military Middle East Command operated the HBT between Az-Zeeb and Tripoli.

Traffic growth

Completion of the Ferdan bridge and HBT hugely enhanced PR's strategic role. PR's annual freight traffic grew from 858,995 tons in 1940-41 to 2,194,848 tons in 1943-44.[62] The huge growth in the number of trains increased the potential for accidents. There were three head-on collisions and in 1942 six H class 4-6-0s were written off in accidents. The war effort both increased wear on equipment and reduced resources for maintenance. In November 1944 a downpour derailed an El Kantara – Haifa train, killing seven people and injuring 40.[56]

1945–1948

Most ROD and S200 locomotives were withdrawn from Palestine before the end of the Second World War and the remaining few soon followed,[42] but PR took 24 LMS 8F's[63] and the two S100s[64] into its locomotive fleet.

In 1945 Zionist paramilitary organisations formed an alliance, the Jewish Resistance Movement, which launched a war against British administration in which members of the Palmach, Irgun and Lehi organisations sabotaged the PR network at 153 places throughout Palestine. Terrorists robbed a train delivering wages to railway staff.[65] In 1946 a terrorist bomb demolished the main part of the Haifa East station building.[66] In the Night of the Bridges of 16–17 June that year, Palmach saboteurs destroyed 11 road and rail links with neighbouring countries including PR's 1٬435 mm (4 ft 8 1⁄2 in) standard gauge links with Egypt and Lebanon and its 1٬050 mm (3 ft 5 11⁄32 in) gauge link with Syria.[67]

On 22 April 1947, terrorists blew up an El Kantara – Haifa train near Rehovot, killing five British soldiers and a number of civilians.[68] As security deteriorated, theft from the railway increased.[69] British security forces failed to intervene to protect the railway and in some cases took part in looting its assets.[70] In January 1948 the General Manager, Arthur Kirby, vainly pleaded with Sir Henry Gurney, Chief Secretary of the Mandate Government, for adequate armed protection for the railway and its 6,000 staff, otherwise they would cease to do their duty and "I cannot guarantee to keep the railways operating".[71] In February Kirby noted:

...locomotives wrecked by mines have been repaired time and time again so that most of them, though blown up several times, are still working after 28 years of service – and working efficiently... We have no fewer than 50 personnel of the train crews absent from duty, some in hospital, suffering from the effects of having been interfered with while trying to perform their duty. Men have been killed while performing their duties. Running trains are subject to attack and the principal marshalling depot is constantly being fired over by snipers... [but] so long as the present Railway Management exists, it will endeavour to maintain the railways and ports as fully as possible without fear or favour and irrespective of politics.[72]

On 31 March 1948 another train was blown up by a terrorist mine near Binyamina south of Haifa, killing 40 civilians and wounding 60.[73][74] By April 1948 Kirby described snipers' and saboteurs' killing of railway staff as "incessant".[70] In 1948 terrorists attacked PR's head office, Khoury House in Haifa, and the resulting fire badly damaged the accounts department.[1] PR's telephone and telegraph network was destroyed[75] and Jewish terrorists stole Kirby's car at gunpoint.[76]

Kirby instructed his staff:

The intention of the Management is that the Railways will be kept in operation and handed over on 15th May as a going concern. The severe loss of Khoury House, Headquarters, and the secession of Arab staff in Haifa will not interfere with this intention... All staff reporting for duty will be allocated to the best advantage, irrespective of the Branch in which they have been hitherto employed...[77]

Privately Kirby wrote to Gurney:

I have been expected to carry on the railways and ports under almost impossible conditions; I have taken upon myself risks and responsibilities that have seldom, if ever befallen the General Manager of a Colonial Railway; I have achieved more than could have been hoped for....[78]

Aftermath

By the time the British withdrew from the Mandate in May 1948, railway operations had effectively ceased.[79] For the remainder of 1948 railway services in the new State of Israel were confined to the area around Haifa, running southwards on the main line as far as Hadera and northwards to Kiryat Motzkin and later Nahariya.[80]

In the centre of the country, the populations of Ramla on the Jaffa – Jerusalem line and Lydda where this line joined the Haifa – El Kantara main line had large Arab majorities, who blocked Israelis from using railways or roads through this key area. One of the few train movements here after the British withdrawal was in July 1948 when Israeli forces launched Operation Danny to expel the Arab populations of Lydda and Ramla. When the Arab defenders blockaded the railway to help defend Lydda, an Israeli force reportedly used S100 0-6-0T number 21 as a battering ram to breach the fortifications.[64] Although Operation Danny succeeded in forcing at least 50,000 Arab residents to leave Lydda and Ramla, the military situation between Ramla and Jerusalem still prevented the restoration of regular trains on that line until March 1950.[81]

In the south of the country the rail link with Sinai and Egypt was fought over. Israelis ambushed an Egyptian troop train near Rafah, derailing it and inflicting many casualties.[80]

Israeli forces secured nearly all of the Haifa – Ashkelon section of the Haifa – El Kantara main line. However, a short stretch of the Eastern Railway through Tulkarm was held by Jordanian forces and the 1949 Armistice Agreements made this front line part of the Armistice Line between Israeli- and Jordanian-controlled territory. In August 1948, Israel bypassed Tulkarm with a short stretch of new track just west of what was to become the Armistice Line.[82]

The Armistice Line between Israel and Syria left the Haifa – Samakh section of the 1050mm gauge Jezreel Valley line in Israeli-controlled territory. Israel Railways continued using parts of this route on an irregular basis until the early 1950s at which point the entire line was abandoned as it was the only narrow gauge line left in the Israeli network. In 2011–2016 the section between Haifa and Beit She'an was rebuilt in standard gauge along roughly the same route as the Ottoman era one, although the rest of the route along the Jordan River from Beit She'an to Samakh remains dismantled and has not been reopened.

Later implementations of the Pole committee recommendations

The 1935 Pole committee's proposals were eventually realized, in modified form, decades after Palestine Railways' demise. In the early 1950s Israel Railways finally connected Tel Aviv to Haifa using two northern routes: First through a link to the Eastern Railway via the Bnei Brak railway station and later through a new coastal railway to Hadera where it linked up with the existing line to Haifa. These links however served the new Tel Aviv Central Station and were only connected to the Jaffa-Lydda-Jerusalem railway through the Eastern Railway, essentially the same indirect route used by Palestine Railways, until 1993 when the Ayalon Railway was constructed through the center of Tel Aviv. The railway junction in Niana, now called Na'an, was built, but rather than serving a line to Rehovot and Rishon LeZion, it served a rebuilt Railway to Beersheba. In 2013, Israel Railways opened a new rail line to Ashdod via the southern Tel Aviv suburbs of Rishon LeZion and Yavne, followed by an extension of the Lod-Ashkelon railway to Beersheba via Sderot, Netivot and Ofakim two years later, finally creating a southbound rail route that bypasses Lydda (now called Lod).

Current status

The former Palestine Railways are currently in three parts:

- Egypt: slowly being rebuilt by Egyptian National Railways.

- Palestine: in the Gaza Strip and West Bank, disused and mostly dismantled.

- Israel: operated by Israel Railways and being expanded.

The HBT Railway is mostly dismantled except for the short section between Haifa and Nahariya (nearby Az-Zeeb). This section has also been double tracked by Israel Railways. As the area it passes through is now a national park, Israel Railway's tenative plans for a new railway to Lebanon foresee a new railway to the east of the HBT railway, branching off the Acre-Karmiel railway at Ahihud.

Sinai railway restoration

Israel dismantled much of the railway in Sinai in the period between the Six-Day War and the Yom Kippur War, re-using most of the materials to build the Bar Lev Line fortifications along the Suez Canal. In the 21st century, starting from Egypt in the south, Egyptian National Railways opened the El Ferdan swing bridge on 14 November 2001, replacing a bridge destroyed in the Six-Day War in 1967. From El Ferdan, work then started on slowly rebuilding the former route to El Arish, with the possibility of renewing the rest of the route to Gaza. The project includes a branch line to Port Said Container Terminal. In December 2008 Google Earth showed progress with stations as far as Bir el-'Abd while some remnants of the old trackbed towards El Arish and Rafah are still visible. Later in the first decade of the 2000s, the rebuilt line in the Sinai became neglected, disused and overrun by sandstorms in many locations. In July 2012, the Egyptian transportation ministry declared its intention to restore the line to Bir el-'Abd. However, this was not carried out and a few years later the construction of the New Suez Canal had since completely disconnected the Sinai from the rest of Egypt’s rail network until a new rail bridge is built somewhere across the canal.

Gallery

Train passing through Rehovot orchards 1939

Compartment of BRCW saloon coach 98, built 1922, now preserved at the Israel Railway Museum

Tender of NBL 4-6-0 no. 62, built 1935, now preserved at the Israel Railway Museum

SLM in Switzerland built this 1050mm gauge 2-8-0 for the Hejaz Railway in 1912. It was originally numbered 90 and later renumbered 153. In 1927 it was transferred to Palestine Railways to work the Jezreel Valley railway. It is pictured here in 1946.

Sir Herbert Samuel, The first British High Commissioner for Palestine, at the ceremony to reopen the Jaffa – Jerusalem line in 1920 after it had been widened to standard gauge

1930s Palestine Railways Semaphore signal at Haifa East, with shunting arm added by Israel Railways in the 1950s, now part of the Israel Railway Museum collection

الهوامش

- ^ أ ب Sherman 2001, p. 232.

- ^ أ ب Cotterell 1984, p. 3.

- ^ أ ب Cotterell 1984, p. 126.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Cotterell 1984, p. 14.

- ^ Shamir, Ronen (2013) Current Flow: The Electrification of Palestine. Stanford: Stanford University Press

- ^ Hughes 1981, pp. 72–73.

- ^ Hughes 1981, p. 35.

- ^ Cotterell 1984, pp. 17–18.

- ^ Cotterell 1984, p. 18.

- ^ أ ب ت Hughes 1981, p. 37.

- ^ أ ب ت Cotterell 1984, p. 128.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ Cotterell 1984, p. 30.

- ^ Cotterell 1984, p. 129.

- ^ Cotterell 1984, p. 21.

- ^ Cotterell 1984, p. 23.

- ^ أ ب Cotterell 1984, p. 25.

- ^ Cotterell 1984, p. 24.

- ^ Sherman 2001, p. 43.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Cotterell 1984, p. 32.

- ^ Cotterell 1984, p. 36.

- ^ أ ب Historical plaque at Ashdod railway station, cited in Rothschild, HaRakevet 18, 1992, page 11

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ Cotterell 1984, p. 45.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د ذ Hansard, 17 July 1935

- ^ أ ب ت Cotterell 1984, p. 46.

- ^ أ ب Cotterell 1984, p. 127.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Cotterell 1984, p. 28.

- ^ Cotterell 1984, p. 29.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج Cotterell 1984, p. 130.

- ^ أ ب ت Hughes 1981, p. 41.

- ^ Cotterell 1984, p. 48.

- ^ أ ب Cotterell 1984, p. 49.

- ^ أ ب Hughes 1981, p. 38.

- ^ Cotterell 1984, pp. 50–52.

- ^ Hughes 1981, p. 50.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج Cotterell 1984, p. 55.

- ^ Cotterell 1984, pp. 49–50.

- ^ Cotterell 1984, p. 50.

- ^ أ ب Cotterell 1984, p. 56.

- ^ Cotterell 1984, p. 57.

- ^ Cotterell 1984, p. 77.

- ^ Hughes 1981, p. 54.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د Hughes 1981, p. 52.

- ^ Tourret 1976, p. 31.

- ^ Tourret 1976, p. 30.

- ^ Tourret 1976, p. 45.

- ^ أ ب Cotterell 1984, p. 72.

- ^ Tourret 1976, p. 46.

- ^ Sherman 2001, p. 93.

- ^ Cotterell 1984, p. 64.

- ^ Cotterell 1984, pp. 64–65.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج Cotterell 1984, p. 65.

- ^ أ ب Loxton, John, typescript memoirs held in the Private Papers Collection of the Middle East Centre, St Antony's College, Oxford; cited in Sherman 2001, p. 119

- ^ أ ب Cotterell 1984, pp. 65–66.

- ^ أ ب Cotterell 1984, p. 66.

- ^ أ ب Cotterell 1984, p. 67.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج Cotterell 1984, p. 78.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج Hughes 1981, p. 47.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح Hughes 1981, p. 48.

- ^ أ ب ت Judd 2004, p. ?.

- ^ File:15-19-Tulkarm-1942.jpg

- ^ File:1415-24-Haifa-1942.jpg

- ^ Lockman 1996, p. 272.

- ^ Cotterell 1984, p. 69.

- ^ أ ب Cotterell 1984, p. 71.

- ^ Cotterell 1984, p. 43.

- ^ Cotterell 1984, plate 46.

- ^ Cotterell 1984, p. 83.

- ^ Sherman 2001, p. 205.

- ^ Sherman 2001, p. 213.

- ^ أ ب Letter from Arthur Kirby to Sir Henry Gurney, 7 April 1948, quoted in Sherman 2001, p. 228

- ^ Letter from Arthur Kirby to Sir Henry Gurney, 20 January 1948, quoted in Sherman 2001, p. 214

- ^ Letter from Arthur Kirby to Jewish and Arab newspapers and chambers of commerce, 17 February 1948, quoted in Sherman 2001, p. 215

- ^ The Palestine Post, 4 January 1948

- ^ New York Times, 4 January 1948

- ^ Sherman 2001, p. 228.

- ^ Sherman 2001, p. 235.

- ^ General Manager's Circular 14/48, 26 April 1948, quoted in Sherman 2001, p. 234

- ^ Letter from Arthur Kirby to Sir Henry Gurney, 24 April 1948, quoted in Sherman 2001, p. 233

- ^ Cotterell 1984, p. 81.

- ^ أ ب Cotterell 1984, p. 84.

- ^ Cotterell 1984, p. 88.

- ^ Cotterell 1984, p. 86.

المراجع

- Cotterell, Paul (1984). The Railways of Palestine and Israel. Abingdon: Tourret Publishing. ISBN 0-905878-04-3.

- Foster, Timothy Charles (2018). Dodds, James; Dodds, Catherine (eds.). Tracks in the Sand: A Railwayman's War. Wivenhoe, Essex: Jardine Press. ISBN 9780993477942.

- Hansard, قالب:Cite hansard

- Hughes, Hugh (1981). Middle East Railways. Harrow: Continental Railway Circle. ISBN 9780950346977.

- Judd, Brendon (2004) [2003]. The Desert Railway: The New Zealand Railway Group in North Africa and the Middle East during the Second World War. Auckland: Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-301915-5.

- Lockman, Zachary (1996). Comrades and Enemies: Arab and Jewish Workers in Palestine, 1906–1948. Berkeley, Los Angeles & London: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-20419-0.

- Rothschild, Walter (1992). "History of Ashdod Ad Halom Railway Station" (PDF). HaRakevet (18): 11. Retrieved 6 December 2009.

- Sherman, A.J. (2001). Mandate Days: British Lives in Palestine, 1918-1948. Baltimore & London: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-6620-0.

- Tourret, R. (1976). War Department Locomotives. Abingdon: Tourret Publishing. ISBN 0-905878-00-0.

- Tourret, R. (1989). Hedjaz Railway. Tourret Publishing. ISBN 0-905878-05-1.. This includes a lot on the narrow-gauge lines within Palestine.

وصلات خارجية

- Winchester, Clarence, ed. (1936). "Railways in Palestine". Railway Wonders of the World. London: Amalgamated Press. pp. 1082–1090. Description of the railways of Palestine in the 1930s

- HaRakevet - official archive of HaRakevet magazine (edited and published by Walter Rothschild) and a link to the editor's PhD Thesis Arthr Kirby and the Palestine Railways 1945-1948.

- Articles that mention track gauge 1435 mm

- Articles that mention track gauge 1050 mm

- Articles containing عبرية-language text

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Articles that mention track gauge 1000 mm

- مسرح عمليات الشرق الأوسط في الحرب العالمية الثانية

- مسرح عمليات المتوسط في الحرب العالمية الثانية

- مسرح عمليات الشرق الأوسط في الحرب العالمية الأولى

- النقل بالسكك الحديدية في فلسطين الانتدابية

- شركات سكك حديدية تأسست في 1920

- شركات سكك حديدية انحلت في 1948

- 1050 mm gauge railways

- 600 mm gauge railways